Extramammary Paget’s Disease of the Scalp with an Underlying Atypical Meningioma—A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

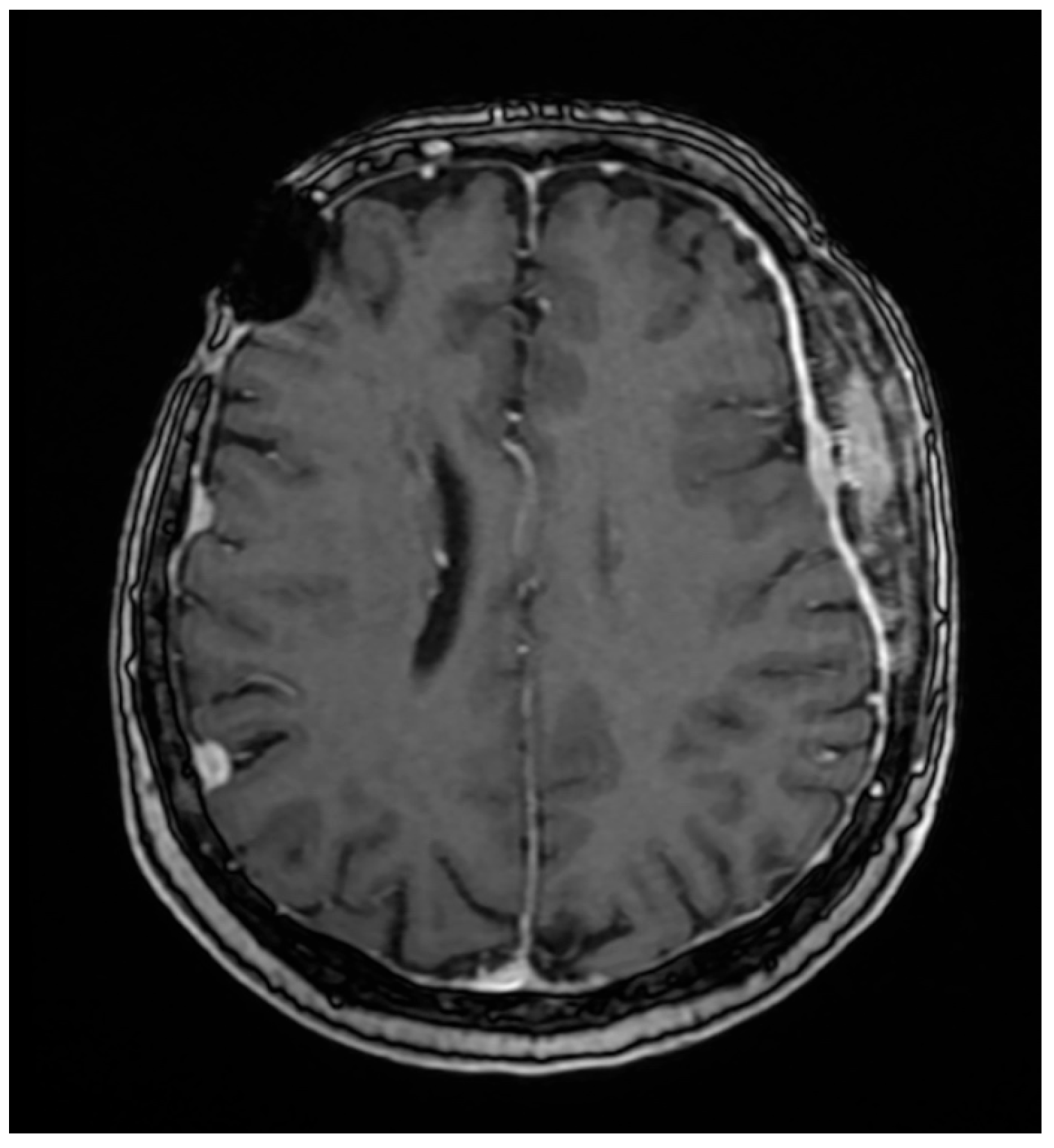

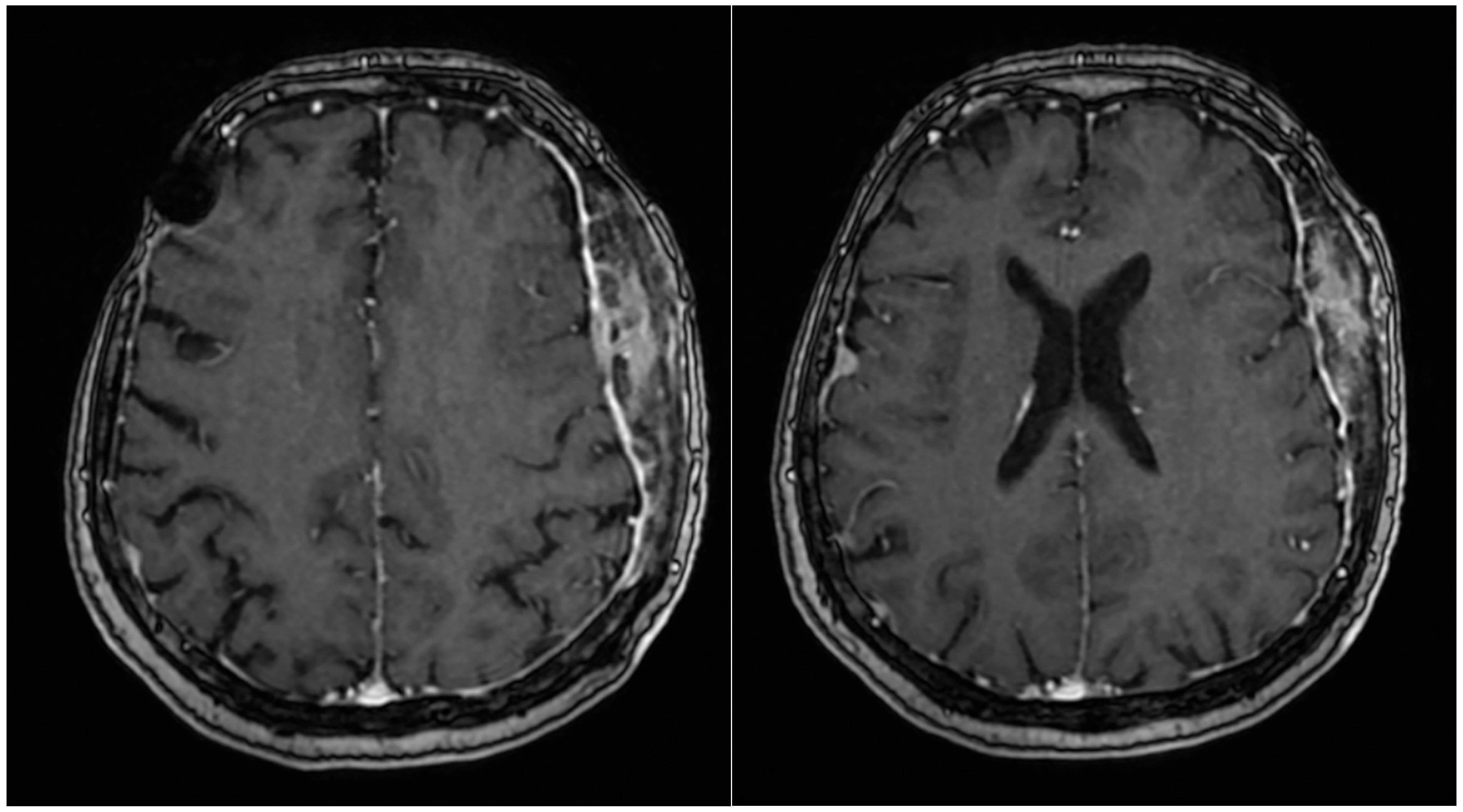

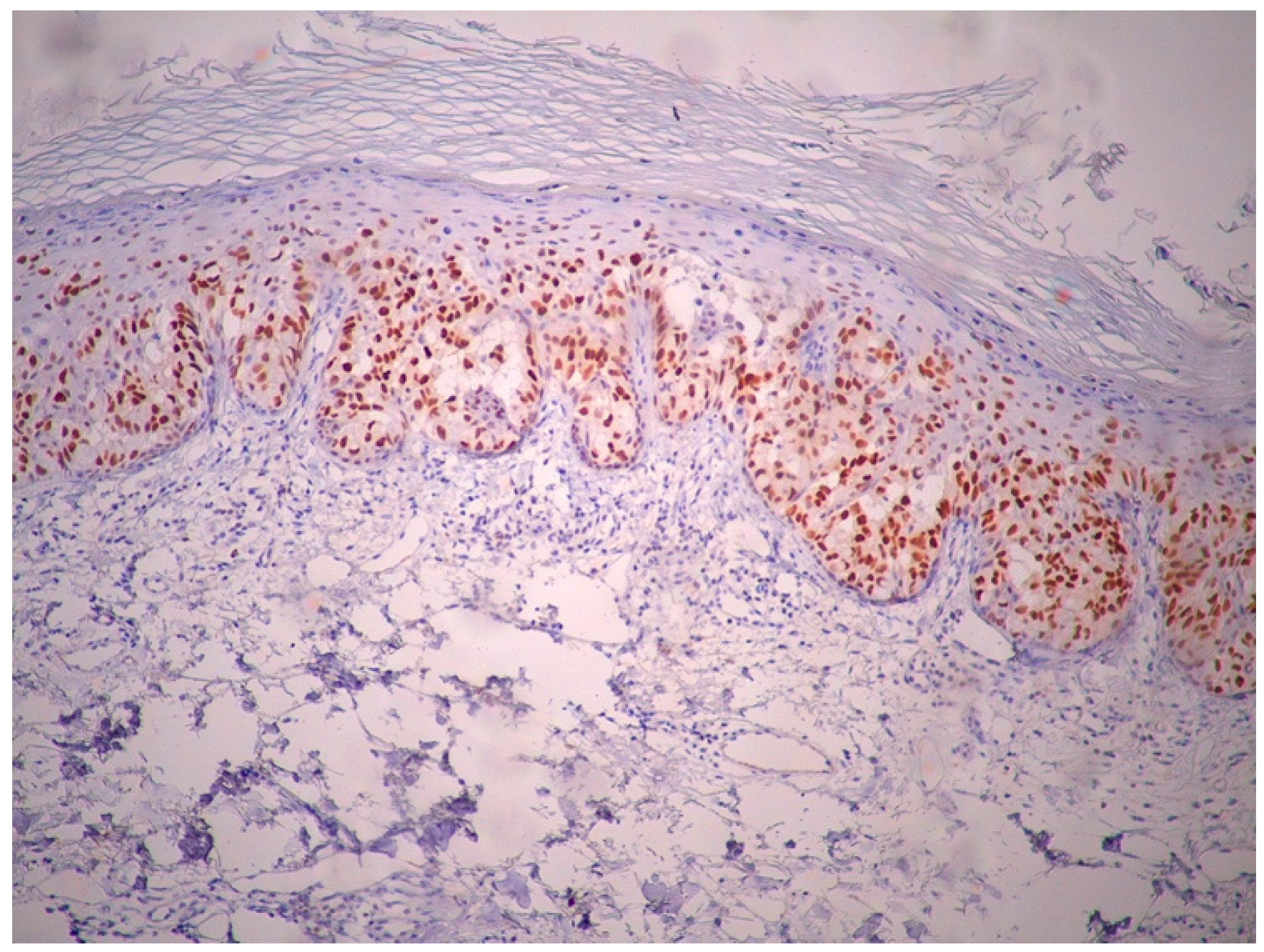

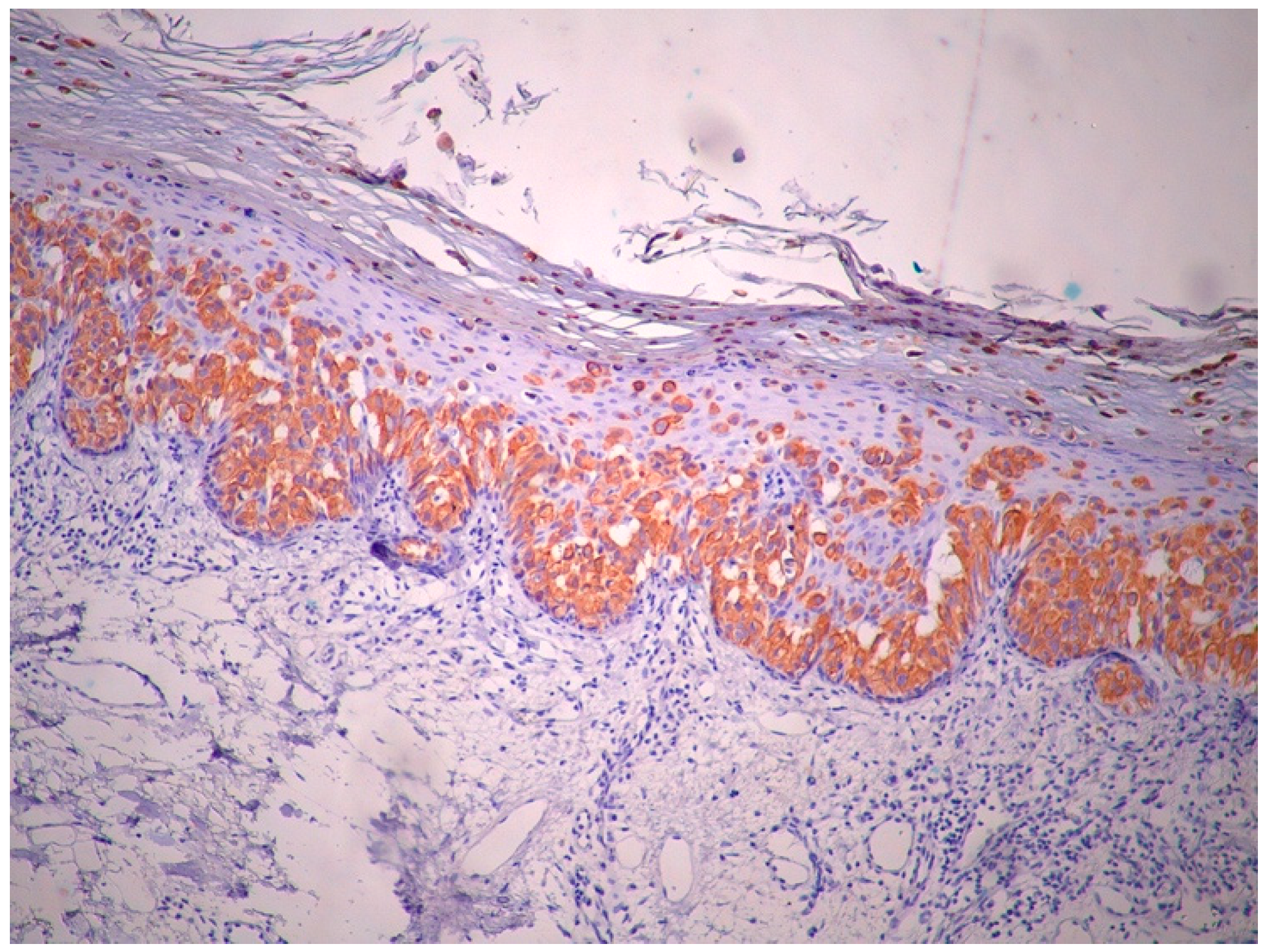

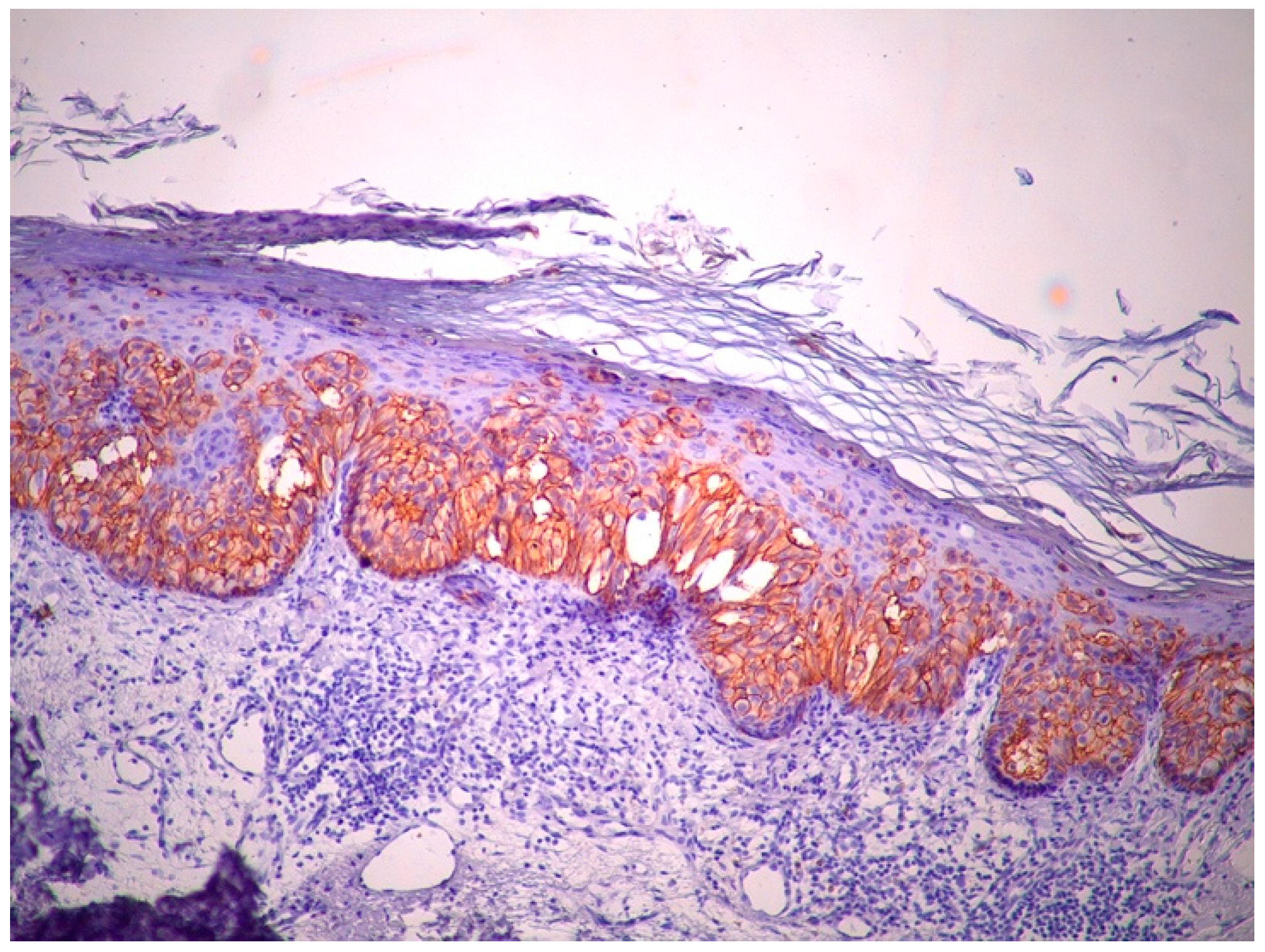

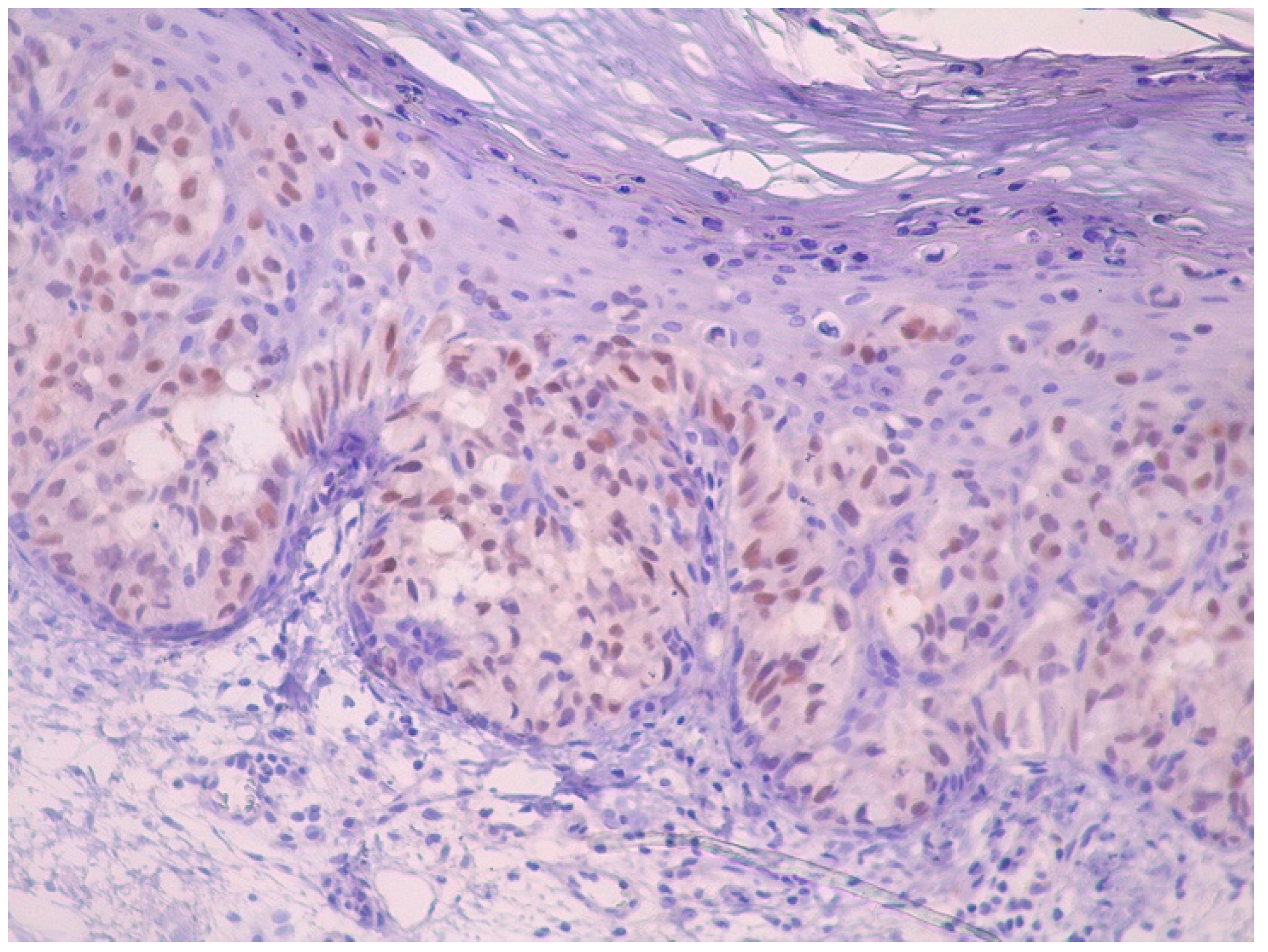

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanitakis, J. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2007, 21, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, H. Paget’s disease affecting the scrotum and penis. Trans. Pathol. Soc. Lond. 1889, 40, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Saida, T.; Iwata, M. “Ectopic” extramammary Paget’s disease affecting the lower anterior aspect of the chest. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1987, 17 Pt 2, 910–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whorton, C.M.; Patterson, J.B. Carcinoma of Moll’s glands with extramammary Paget’s disease of the eyelid. Cancer 1955, 8, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamoti, E.; Platsidaki, E.; Markantoni, V.; Spiliopoulos, T.; Balaskas, E.; Chaidemenos, G. An unusual clinical presentation of ectopic extramammary Paget’s disease arising on the scalp. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, AB42. [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba, A.; Iglesias, M.E.; Rodríguez, I.; Yanguas, J.I. Extramammary paget disease with frontotemporal involvement: A case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013, 104, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, C.E.; Todd, D.H.; Binder, S.W.; Cassarino, D.S. Apocrine hidradenocarcinoma showing Paget’s disease and mucinous metaplasia. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2009, 36, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C.; Lee, J.Y.; Wong, T.W. Depigmented extramammary Paget’s disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 151, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, V.; Davidson, E.J.; Davies-Humphreys, J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG 2005, 112, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Bito, T.; Kabashima, R.; Yoshiki, R.; Hino, R.; Nakamura, M.; Shiraishi, M.; Tokura, Y. Ectopic extramammary Paget’s disease: Case report and literature review. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2010, 90, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, I.Y.; Sung, H.T.; Chun, H.S.; Han, J.; Lee, E.S. A Case of Extramammary Paget’s Disease on the Scalp. Ann. Dermatol. 1999, 11, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwenofu, O.H.; Samie, F.H.; Ralston, J.; Cheney, R.T.; Zeitouni, N.C. Extramammary Paget’s disease presenting as alopecia neoplastica. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2008, 35, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debarbieux, S.; Dalle, S.; Depaepe, L.; Jeanniot, P.Y.; Poulalhon, N.; Thomas, L. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the scalp: Examination by in vivo and ex vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Skin Res. Technol. 2014, 20, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniyuki, S.; Maekawa, N. Ectopic extramammary Paget’s disease on the head: Case report and literature review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015, 54, e483–e486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.A.; Reygagne, P. Successful treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease of the scalp with photodynamic therapy. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, 580–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, A.; Wood, B.A.; Gurfinkel, R.; Harvey, N.T. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the scalp presenting with a concurrent basal cell carcinoma. Pathology 2016, 48, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, J.J. Extramammary Paget’s disease: Prognosis and relationship to internal malignancy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1985, 13, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siesling, S.; Elferink, M.A.; van Dijck, J.A.; Pierie, J.P.; Blokx, W.A. Epidemiology and treatment of extramammary Paget disease in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 33, 951–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, Y.; Ohara, K. Ectopic extramammary Paget’s disease affecting the upper abdomen. Br. J. Dermatol. 1996, 134, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liegl, B.; Horn, L.C.; Moinfar, F. Androgen receptors are frequently expressed in mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Mod. Pathol. 2005, 18, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz de Leon, E.; Carcangiu, M.L.; Prieto, V.G.; McCue, P.A.; Burchette, J.L.; To, G.; Norris, B.A.; Kovatich, A.J.; Sanchez, R.L.; Krigman, H.R.; et al. Extramammary Paget disease is characterized by the consistent lack of estrogen and progesterone receptors but frequently expresses androgen receptor. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000, 113, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wananukul, S.; Voramethkul, W.; Kaewopas, Y.; Hanvivatvong, O. Prevalence of positive anti-nuclear antibodies in healthy children. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2005, 23, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.P.; Wang, C.G.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.Q.; Guo, D.L.; Jing, X.Z.; Yuan, C.G.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.M.; Han, M.S.; et al. The prevalence of antinuclear antibodies in the general population of China: A cross-sectional study. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2014, 76, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierie, J.P.; Choudry, U.; Muzikansky, A.; Finkelstein, D.M.; Ott, M.J. Prognosis and management of extramammary Paget’s disease and the association with secondary malignancies. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2003, 196, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Liu, H.N.; Wong, C.K. Extramammary Paget’s disease: A report of 22 cases in Chinese males. J. Dermatol. 1996, 23, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter, M.D.; Quan, S.H.; Busam, K.; Paty, P.P.; Wong, D.; Guillem, J.G. Long-term outcome of perianal Paget’s disease. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2003, 46, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, J.; Lambert, H.C.; Hale, T.M.; Morris, P.C.; Schuerch, C. Paget’s disease of the vulva: Prevalence of associated vulvar adenocarcinoma, invasive Paget’s disease, and recurrence after surgical excision. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 180 Pt 1, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.L.; Yang, W.G.; Tsay, P.K.; Swei, H.; Chuang, S.S.; Wen, C.J. Penoscrotal extramammary Paget’s disease: A review of 33 cases in a 20-year experience. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2003, 112, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.E., Jr.; Austin, C.; Ackerman, A.B. Extramammary Paget’s disease. A critical reexamination. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1979, 1, 101–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weedon, D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology, 4th ed.; Churchill Livingstone Elsevier: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hendi, A.; Brodland, D.G.; Zitelli, J.A. Extramammary Paget’s disease: Surgical treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004, 51, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Lin, S.D.; Yang, C.C.; Chou, C.K. Surgical treatment of the penoscrotal Paget’s disease. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1989, 23, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, P.H.; Leong, J.Y.; Voelzke, B.B. Surgical Experience With Genital and Perineal Extramammary Paget’s Disease. Urology 2019, 128, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatta, N.; Yamada, M.; Hirano, T.; Fujimoto, A.; Morita, R. Extramammary Paget’s disease: Treatment, prognostic factors and outcome in 76 patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 158, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, A.; Akasaka, K.; Oikawa, H.; Akasaka, T.; Masuda, T.; Maesawa, C. Immunohistochemical study of HER2 and TUBB3 proteins in extramammary Paget disease. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2010, 32, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, J.A.; Torres-Cabala, C.; Ivan, D.; Prieto, V.G. HER-2/neu expression in extramammary Paget disease: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemistry study of 47 cases with and without underlying malignancy. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2009, 36, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, M.; Koike, I.; Wada, H.; Miyagi, E.; Kasuya, T.; Kaizu, H.; Matsui, T.; Mukai, Y.; Ito, E.; Inoue, T. Radiation therapy for extramammary Paget’s disease: Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, M.; Koike, I.; Wada, H.; Miyagi, E.; Kasuya, T.; Kaizu, H.; Mukai, Y.; Inoue, T. Postoperative radiation therapy for extramammary Paget’s disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besa, P.; Rich, T.A.; Delclos, L.; Edwards, C.L.; Ota, D.M.; Wharton, J.T. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the perineal skin: Role of radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1992, 24, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirer, E.; El Sayed, F.; Ammoury, A.; Lamant, L.; Messer, L.; Bazex, J. Treatment of mammary and extramammary Paget’s skin disease with topical imiquimod. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2006, 17, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, J.D.; Zeitouni, N.C. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000, 142, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, S.; Dee, A.S.; Cheney, R.T.; Frawley, N.P.; Zeitouni, N.C.; Oseroff, A.R. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 146, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahagi, S.; Noda, H.; Kamegashira, A.; Madokoro, N.; Hori, I.; Shindo, H.; Mihara, S.; Hide, M. Metastatic extramammary Paget’s disease treated with paclitaxel and trastuzumab combination chemotherapy. J. Dermatol. 2009, 36, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Age/Sex | Location. Size | Associaeted Lesion | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Son et al., 2002 [11] | 45/Female | NR/5 cm | - | Surgical excision |

| Hans Iwenofu et al., 2008 [12] | 57/Female | Right parietal/5 × 3 cm | - | Mohs micrographic surgery |

| Wahl et al., 2009 [7] | 54/Male | NR/1 cm | Hidradenocarcinoma with mucinous differentiation Renall cell carcinoma | Surgical excision |

| Cordoba et al., 2013 [6] | 64/Female | Right frontotemporal/5 cm | Photodynamic therapy + imiquimod | |

| Debarbieux et al., 2014 [13] | 54/Male | Posterior vertex/6 cm | - | Surgical excision |

| Kuniyuki et al., 2015 [14] | 82/Male | Occipital/85 × 50 mm | - | Surgical excision |

| Yourssef et al., 2015 [15] | 86/Male | Right parietal/8.5 × 6 cm | - | Photodynamic therapy |

| Kang A. et al., 2016 [16] | 73/Female | NR/20 mm | Nodular Basal Cell Carcinoma | Surgical excision |

| Balamoti et al., 2017 [5] | 50/Female | NR/2 × 2 cm | Seborrheic keratosis | Surgical excision |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solomon, C.; Apostu, A.P.; Trufin, I.I.; Halmagyi, S.R.; Rogojan, L.; Șenilă, S.C.; Ungureanu, L. Extramammary Paget’s Disease of the Scalp with an Underlying Atypical Meningioma—A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Life 2025, 15, 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071064

Solomon C, Apostu AP, Trufin II, Halmagyi SR, Rogojan L, Șenilă SC, Ungureanu L. Extramammary Paget’s Disease of the Scalp with an Underlying Atypical Meningioma—A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Life. 2025; 15(7):1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071064

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolomon, Carolina, Adina Patricia Apostu, Ioana Irina Trufin, Salomea Ruth Halmagyi, Liliana Rogojan, Simona Corina Șenilă, and Loredana Ungureanu. 2025. "Extramammary Paget’s Disease of the Scalp with an Underlying Atypical Meningioma—A Case Report and Review of the Literature" Life 15, no. 7: 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071064

APA StyleSolomon, C., Apostu, A. P., Trufin, I. I., Halmagyi, S. R., Rogojan, L., Șenilă, S. C., & Ungureanu, L. (2025). Extramammary Paget’s Disease of the Scalp with an Underlying Atypical Meningioma—A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Life, 15(7), 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071064