Cardiovascular Diseases and Type D Personality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Literature of the Last 10 Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategies and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Selection Process and Data Extraction

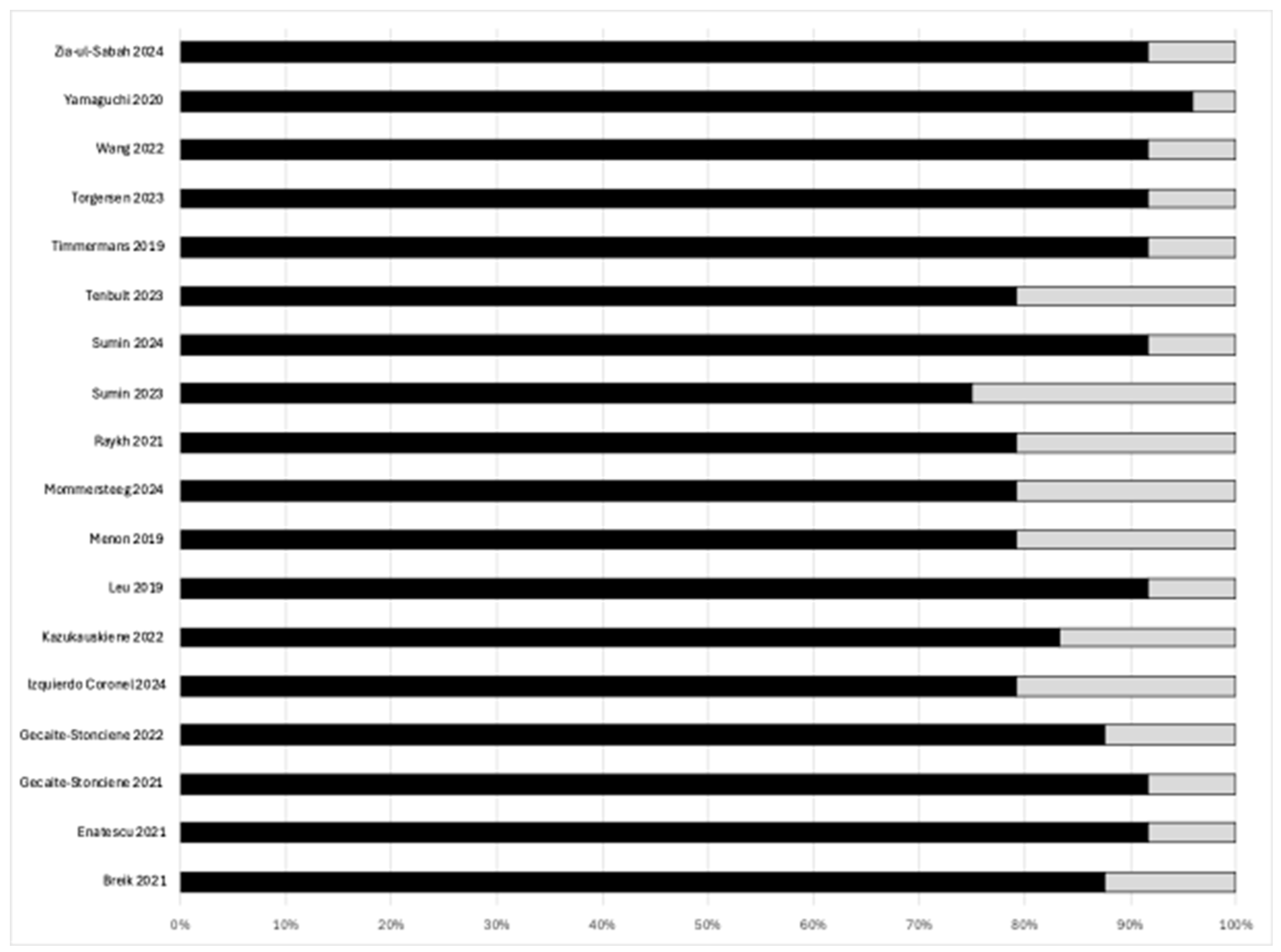

2.4. Qualitative Assessment: Risk of Bias of the Included Studies

2.5. Meta-Analysis Strategy

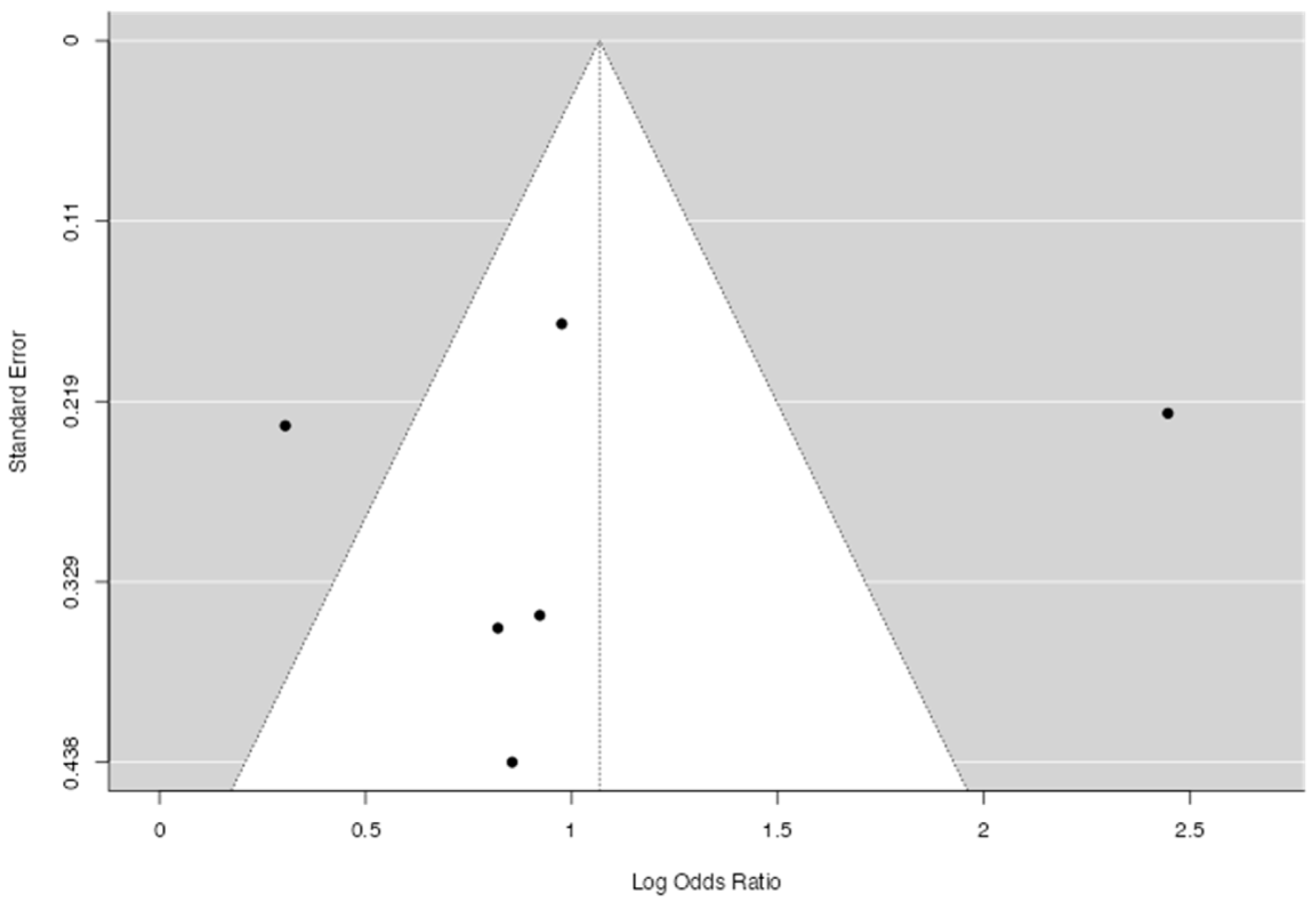

3. Results

3.1. Selection of the Studies

3.2. Results of the Selected Studies

3.2.1. Demographic Data

3.2.2. Qualitative Assessment

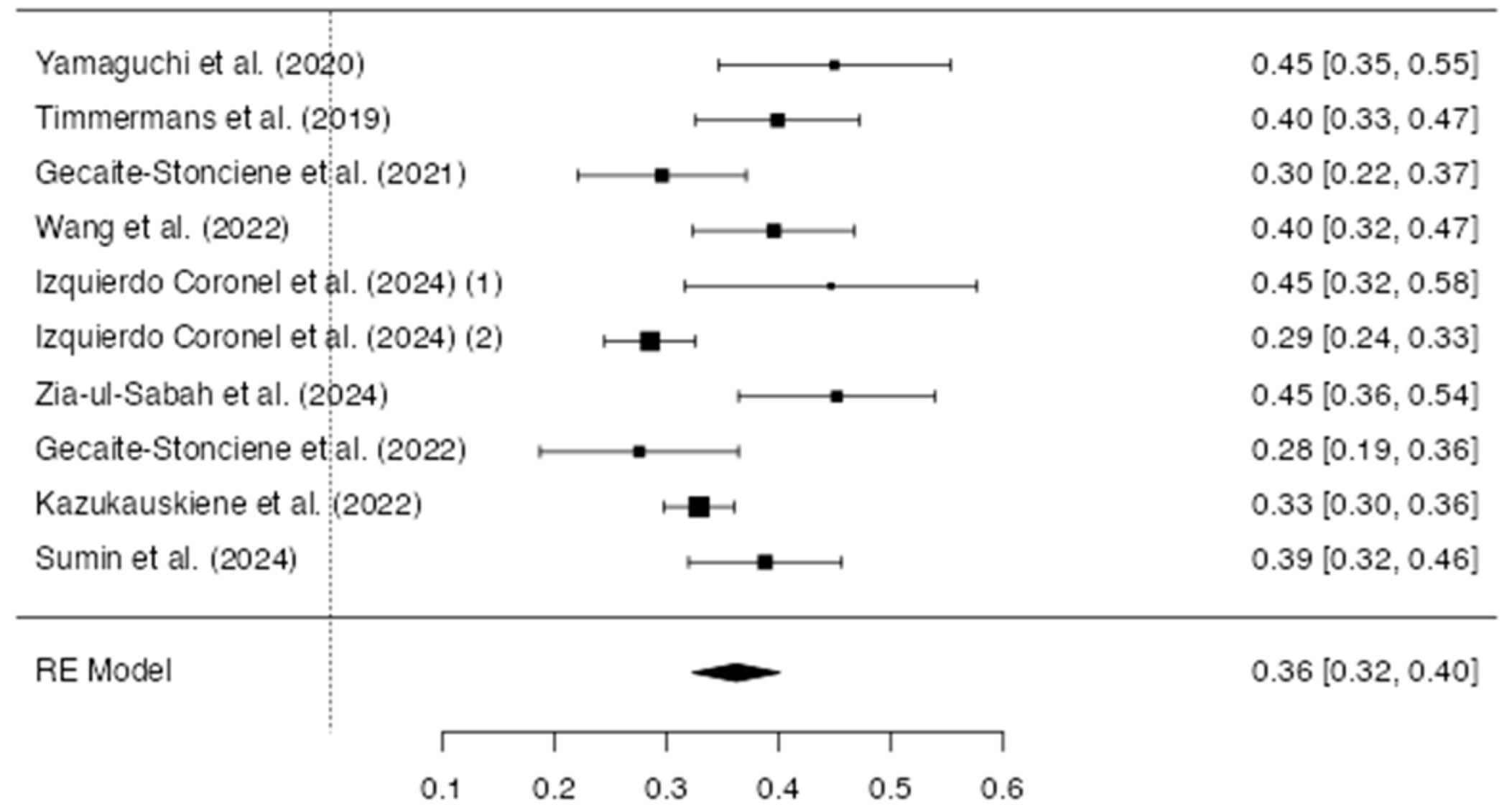

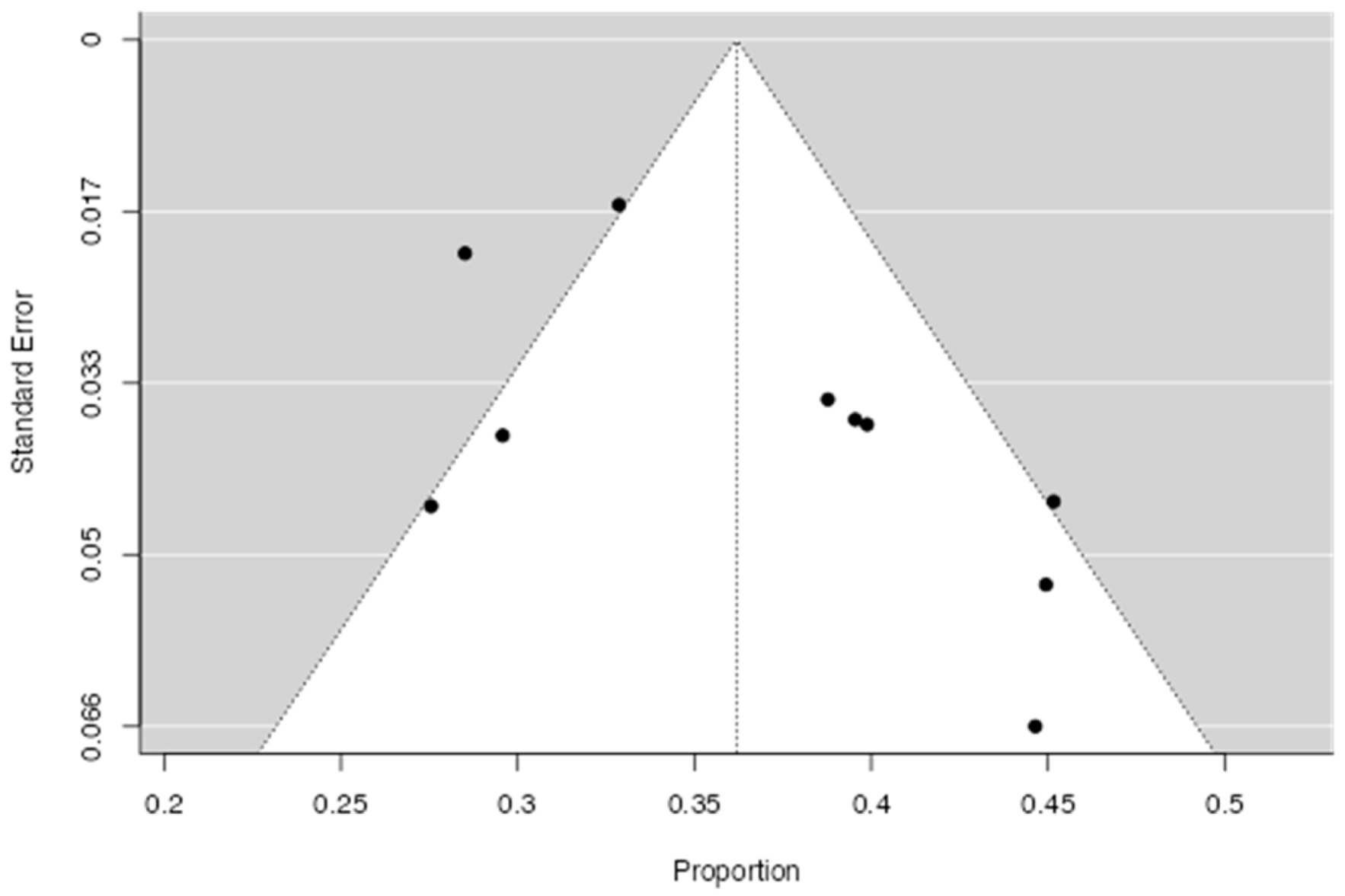

3.2.3. Prevalence of Type D Personality in CVD

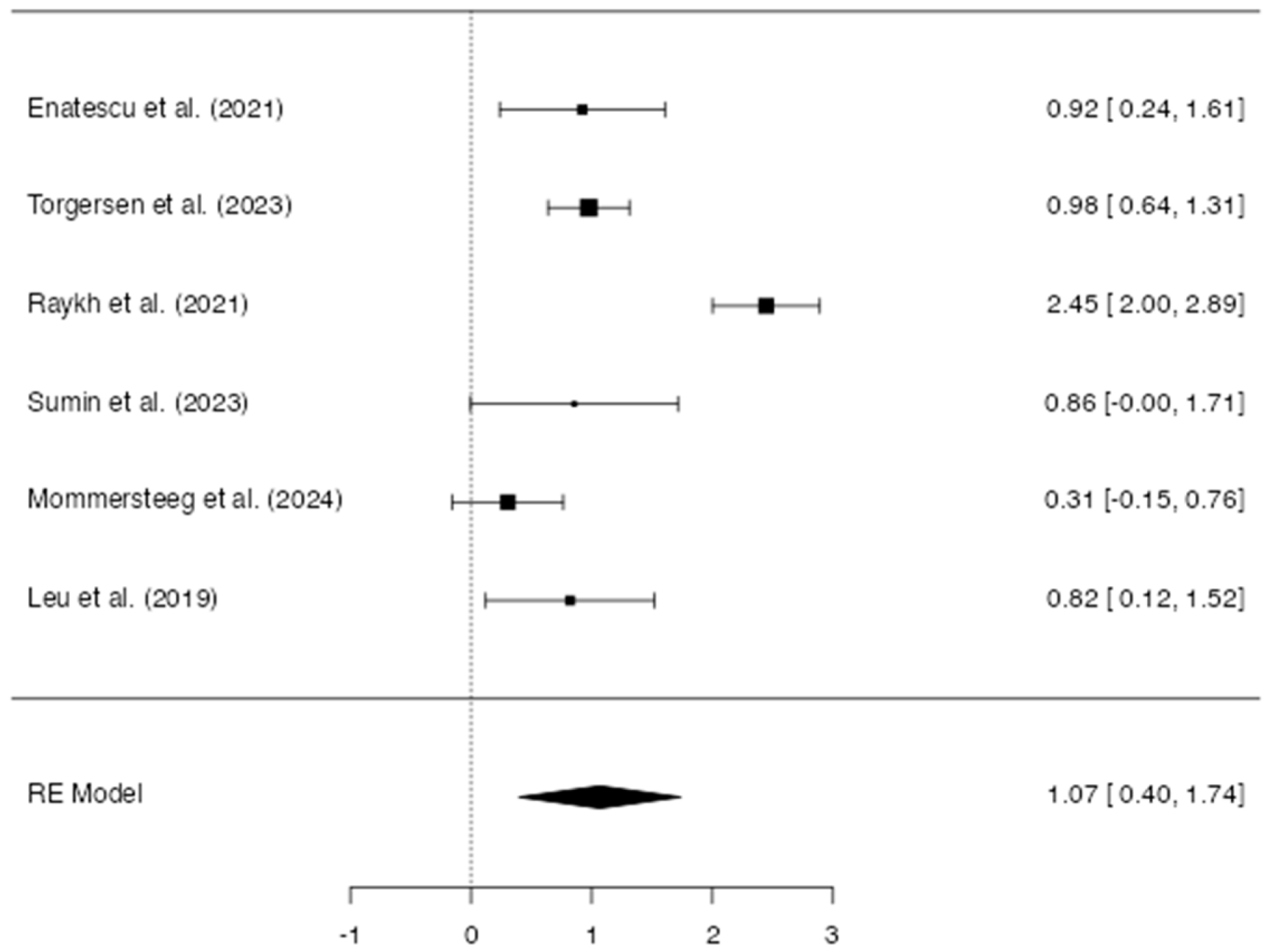

3.2.4. Difference Between Type D and Non-Type D in CVD

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications and the Role of Psychological Assessment

4.2. Possible Biological Mechanisms

4.3. Types of Markers of Type D

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saglietto, A.; Manfredi, R.; Elia, E.; D’Ascenzo, F.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Münzel, T. Cardiovascular disease burden: Italian and global perspectives. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2021, 69, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikary, D.; Barman, S.; Ranjan, R.; Stone, H. A systematic review of Major Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Growing Global Health Concern. Cureus 2022, 14, e30119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Levine, G.N.; Cohen, B.E.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Fleury, J.; Huffman, J.C.; Khalid, U.; Labarthe, D.R.; Lavretsky, H.; Michos, E.D.; Spatz, E.S.; et al. Psychological health, well-being, and the Mind-Heart-Body Connection: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e763–e783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roest, A.M.; Martens, E.J.; de Jonge, P.; Denollet, J. Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denollet, J. Personality and coronary heart disease: The type-D scale-16 (DS16). Ann. Behav. Med. 1998, 20, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenman, R.H.; Friedman, M.; Straus, R.; Wurm, M.; Kositchek, R.; Hahn, W.; Werthessen, N.T. A predictive study of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1964, 189, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mols, F.; Denollet, J. Type D personality in cardiovascular disease: A review. Stress 2010, 13, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qezweny, M.N.; Utens, E.M.; Dulfer, K.; Hazemeijer, B.A.; van Geuns, R.J.; Daemen, J.; van Domburg, R. The association between type D personality, depression and anxiety ten years after PCI. Neth. Heart J. 2016, 24, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martens, E.J.; Kupper, N.; Pedersen, S.S.; Denollet, J.; Widdershoven, J.W. Type D personality, medication adherence, and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 773–780. [Google Scholar]

- Denollet, J.; Holmes, R.V.; Vrints, C.J.; Conraads, V.M. Unfavorable outcome of heart transplantation in recipients with type D personality. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2007, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhao, Z.; Li, L.; Yin, S.; Sun, X.; Yu, B.; Gao, X.; Lin, P.; Yang, Y. The relationship between Type D personality with atherosclerotic plaque and cardiovascular events: The mediation effect of inflammation and kynurenine/tryptophan metabolism. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 986712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupper, N.; Denollet, J. Type D Personality as a Risk Factor in Coronary Heart Disease: A Review of Current Evidence. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2018, 20, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- da Costa Santos, C.M.; de Mattos Pimenta, C.A.; Nobre, M.R. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmet, L.M.; Lee, R.C.; Cook, L.S. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR): Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004; AHFMR–HTA Initiative, 13. [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, G.; Carpenter, J.R.; Rücker, G. Meta-Analysis with R; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoğaltay, N.; Karadağ, E. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. In Leadership and Organizational Outcomes: Meta-Analysis of Empirical Studies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.; Clarke, M.J.; Wordsworth, S.; Yeo, S.T. A systematic review of the effectiveness of fibrin sealant in surgical procedures. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitropoulou, K.; Vossos, V.; Kennedy, S. The role of micronutrients in cognitive function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlund, K.; Devereaux, P.J.; Wetterslev, J.; Guyatt, G. Can Trial Sequential Monitoring Boundaries Reduce Spurious Inferences from Meta-Analyses? J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enatescu, V.R.; Cozma, D.; Țint, D.; Enătescu, I.; Șimu, M.; Giurgi-Oncu, C.; Lăzărescu, M.A.; Mornos, C. The Relationship Between Type D Personality and the Complexity of Coronary Artery Disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gecaite-Stonciene, J.; Hughes, B.M.; Burkauskas, J.; Bunevicius, A.; Kazukauskiene, N.; van Houtum, L.; Brozaitiene, J.; Neverauskas, J.; Mickuviene, N. Fatigue Is Associated with Diminished Cardiovascular Response to Anticipatory Stress in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 692098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gecaite-Stonciene, J.; Hughes, B.M.; Kazukauskiene, N.; Bunevicius, A.; Burkauskas, J.; Neverauskas, J.; Bellani, M.; Mickuviene, N. Cortisol response to psychosocial stress, mental distress, fatigue and quality of life in coronary artery disease patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Izquierdo Coronel, B.; López Pais, J.; Nieto Ibáñez, D.; Olsen Rodríguez, R.; Galán Gil, D.; Perela Álvarez, C.; Abad Romero, R.; Álvarez Bello, M.; Martín Muñoz, M.; Espinosa Pascual, M.J.; et al. Prevalence and prognosis of anxiety, insomnia, and type D personality in patients with myocardial infarction: A Spanish cohort. Cardiol. J. 2024, 31, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kazukauskiene, N.; Fineberg, N.A.; Bunevicius, A.; Narvaez Linares, N.F.; Poitras, M.; Plamondon, H.; Pranckeviciene, A.; Gecaite-Stonciene, J.; Brozaitiene, J.; Varoneckas, G.; et al. Predictive value of baseline cognitive functioning on health-related quality of life in individuals with coronary artery disease: A 5-year longitudinal study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2022, 21, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leu, H.B.; Yin, W.H.; Tseng, W.K.; Wu, Y.W.; Lin, T.H.; Yeh, H.I.; Cheng Chang, K.; Wang, J.H.; Wu, C.C.; Chen, J.W. Impact of type D personality on clinical outcomes in Asian patients with stable coronary artery disease. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mommersteeg, P.M.C.; Lodder, P.; Aarnoudse, W.; Magro, M.; Widdershoven, J.W. Psychosocial distress and health status as risk factors for ten-year major adverse cardiac events and mortality in patients with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 406, 132062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raykh, O.I.; Sumin, A.N.; Korok, E.V. The Influence of Personality Type D on Cardiovascular Prognosis in Patients After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Data from a 5-Year-Follow-up Study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 29, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sumin, A.N.; Shcheglova, A.V. Pathogenetic Mechanisms Underlying Major Adverse Cardiac Events in Personality Type D Patients after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The Roles of Cognitive Appraisal and Coping Strategies. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sumin, A.N.; Shcheglova, A.V.; Barbarash, O.L. New indicator of arterial stiffness START—Is there a prognostic value of its dynamics in patients with coronary artery disease? Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Timmermans, I.; Versteeg, H.; Duijndam, S.; Graafmans, C.; Polak, P.; Denollet, J. Social inhibition and emotional distress in patients with coronary artery disease: Type D personality construct. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 1929–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Torgersen, K.S.; Sverre, E.C.B.; Weedon-Fekjær, H.; Andreassen, O.A.; Munkhaugen, J.; Dammen, T. Risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease patients with Type D personality. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1119146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, D.; Izawa, A.; Matsunaga, Y. The Association of Depression with Type D Personality and Coping Strategies in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 1589–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zia-Ul-Sabah, S.A.M.; Alqahtani, S.A.M.; Alghamdi, B.H.; Wani, J.I.; Aziz, S.; Durrani, H.K.; Patel, A.A.; Rangraze, I.; Wani, S.J. Association of type-D personality and left-ventricular remodelling in patients treated with primary percutaneous intervention after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Breik, W.; Elbedour, S. The Predictive Ability of Type D Personality Pattern, Anxiety, and Depression in Cardiac Disease. Eur. J. Ment. Health 2021, 16, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.; Pillai, A.G.; Satheesh, S.; Kaliamoorthy, C.; Sarkar, S. Factor structure and validity of Type D personality scale among Indian (Tamil-speaking) patients with acute myocardial infarction. Indian J. Psychiatry 2019, 61, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tenbult, N.; van Asten, I.; Traa, S.; Brouwers, R.W.M.; Spee, R.F.; Lu, Y.; Brini, A.; Kop, W.; Kemps, H. Determinants of information needs in patients with coronary artery disease receiving cardiac rehabilitation: A prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e068351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Spiegelhalter, D.J. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2009, 172, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Riley, R.D.; Higgins, J.P.; Deeks, J.J. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ 2011, 342, d549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, S.S.; Denollet, J. Type D personality, cardiac events, and impaired quality of life: A review. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2003, 10, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium; Magnussen, C.; Ojeda, F.M.; Leong, D.P.; Alegre-Díaz, J.; Amouyel, P.; Aviles-Santa, L.; De Bacquer, D.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A.; et al. Global Effect of Modifiable Risk Factors on Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Friedman, M.; Rosenman, R.H. Association of specific overt behavior pattern with blood and cardiovascular findings; blood cholesterol level, blood clotting time, incidence of arcus senilis, and clinical coronary artery disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1959, 169, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chida, Y.; Steptoe, A. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: A meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denollet, J. DS14: Standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosom. Med. 2005, 67, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Checklist |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| S. No | First Author’s Name/Year of Publication [Reference Number] | Country | Sample Size | Male Percentage | Age (Mean; Age Range) | Study Design | MA Data | Clinical Condition | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enatescu/2021 [23] | Romania | 221 | 59.3 | 60 ± 10.2 | Cross-sectional | Odds Ratio | CAD (coronary artery disease) | Type D is associated with higher CVD severity (IMA). |

| 2 | Gecaite-Stonciene/2021 [24] | Lithuania | 142 | 85 | 52 ± 8 | Cross-sectional | Prevalence | ACS (Acute Coronary Syndrome) | Type D is associated with higher distress and lower cardiovascular response. |

| 3 | Gecaite-Stonciene/2022 [25] | Lithuania | 98 | 87.8 | 52.92 ± 7.17 | Cross-sectional | Prevalence | CAD | Type D was associated with CAD (cortisol response). |

| 4 | Izquierdo Coronel/2024 (1) [26] | Spain | 56 | 45 | 66.8 ± 13.7 | Longitudinal study (FU: 3 years) | Prevalence | MINOCA (myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries) | Type D is associated with a cardiovascular condition. |

| 5 | Izquierdo Coronel/2024 (2) [26] | Spain | 477 | 76 | 66.5 ± 13.7 | Longitudinal study (FU: 3 years) | Prevalence | MICAD (myocardial infarction with coronary artery disease) | Type D is associated with a cardiovascular condition. |

| 6 | Kazukauskien/2022 [27] | Lithuania | 864 | 74 | 58 ± 9 | Longitudinal study (FU: 5 years) | Prevalence | CAD | Type D personality is associated with a lower quality of life. |

| 7 | Leu/2019 [28] | Taiwan | 777 | 84.3 | 62.03 ± 10.5 | Longitudinal study (FU: 1 year) | Odds Ratio | CAD | Type D personality predicts CAD. |

| 8 | Mommersteeg/2024 [29] | The Netherlands | 517 | 55 | 63 | Longitudinal study (FU: 10 years) | Odds Ratio | MACE (major adverse cardiovascular event) | Type D does not predict negative outcomes in MACE. |

| 9 | Raykh/2021 [30] | Russia | 602 | 81.4 | 57.7 ± 7.3 | Longitudinal study (FU: 10 years) | Odds Ratio | Post-coronary artery bypass grafting | Negative outcomes of CAD at 5 years post intervention are highly associated with Type D. |

| 10 | Sumin/2023 [31] | Russia | 91 | - | 64.7 | Longitudinal study (FU: 1 year) | Odds Ratio | MACE | Type D personality predicts MACE events and hospitalization. |

| 11 | Sumin/2024 [32] | Russia | 196 | 73 | 62 ± 1 | Longitudinal study (FU: 10 years) | Prevalence | CAD | Type D is predictive of the prognosis of CAD. |

| 12 | Timmermans/2019 [33] | The Netherlands | 173 | 77 | 69.1 ± 9.6 | Cross-sectional | Prevalence | CAD | Type D personality is associated with a low quality of life (physical health status) and social anxiety. |

| 13 | Torgersen/2023 [34] | Norway | 1083 | 79 | 61.5 ± 9.6 | Cohort study; FU: 4.2 years | Odds Ratio | CAD | Type D personality is associated with recurrent CAD. |

| 14 | Wang/2022 [11] | China | 177 | 58.8 | 55.79 ± 10.70 | Cross-sectional | Prevalence | CAD | Type D is associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes in CAD, mediated by a pro-inflammatory biomarker. |

| 15 | Yamaguchi/2020 [35] | Japan | 89 | 88.8 | 66 (58–74) | Cross-sectional | Prevalence | CAD | Type D personality in CAD is associated with depression and negative coping. |

| 16 | Zia-ul-Sabah/2024 [36] | Saudi Arabia | 124 | 55 | 67 ± 10 | Longitudinal (FU: 1 year) | Prevalence | Post-STEMI | Type D is predictive of the severity of left ventricular adverse remodeling. |

| S. No | First Author’s Name/Year of Publication [Reference Number] | Item_1 | Item_2 | Item_3 | Item_4 | Item_5 | Item_6 | Item_7 | Item_8 | Item_9 | Item_10 | Item_11 | Item_12 | Item_13 | Item_14 | Total Score | Index of Quality | Risk of Bias | Index of Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enatescu/2021 [23] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.92 | G | 92 | 8 |

| 2 | Gecaite-Stonciene/2021 [24] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.92 | G | 92 | 8 |

| 3 | Gecaite-Stonciene/2022 [25] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 0.88 | G | 88 | 13 |

| 4 | Izquierdo Coronel/2024 [26] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 0.79 | A | 79 | 21 |

| 5 | Kazukauskien/2022 [27] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 | 0.83 | G | 83 | 17 |

| 6 | Leu/2019 [28] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.92 | G | 92 | 8 |

| 7 | Mommersteeg/2024 [29] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 0.79 | A | 79 | 21 |

| 8 | Raykh/2021 [30] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 0.79 | A | 79 | 21 |

| 9 | Sumin/2023 [31] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 0.75 | A | 75 | 25 |

| 10 | Sumin/2024 [32] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.92 | G | 92 | 8 |

| 11 | Timmermans/2019 [33] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.92 | G | 92 | 8 |

| 12 | Torgersen/2023 [34] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.92 | G | 92 | 8 |

| 13 | Wang/2022 [11] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.92 | G | 92 | 8 |

| 14 | Yamaguchi/2020 [35] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 23 | 0.96 | H | 96 | 4 |

| 15 | Zia-ul-Sabah/2024 [36] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.92 | G | 92 | 8 |

| 16 | Breik/2021 [37] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 0.88 | G | 88 | 13 |

| 17 | Menon/2019 [38] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 0.79 | A | 79 | 21 |

| 18 | Tenbult/2023 [39] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 0.79 | A | 79 | 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Nakhebi, O.A.S.; Albu-Kalinovic, R.; Bosun, A.; Neda-Stepan, O.; Gliga, M.; Crișan, C.-A.; Marinescu, I.; Mornoș, C.; Enatescu, V.-R. Cardiovascular Diseases and Type D Personality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Literature of the Last 10 Years. Life 2025, 15, 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071061

Al Nakhebi OAS, Albu-Kalinovic R, Bosun A, Neda-Stepan O, Gliga M, Crișan C-A, Marinescu I, Mornoș C, Enatescu V-R. Cardiovascular Diseases and Type D Personality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Literature of the Last 10 Years. Life. 2025; 15(7):1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071061

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Nakhebi, Omar Anwar Saleh, Raluka Albu-Kalinovic, Adela Bosun, Oana Neda-Stepan, Marius Gliga, Cătălina-Angela Crișan, Ileana Marinescu, Cristian Mornoș, and Virgil-Radu Enatescu. 2025. "Cardiovascular Diseases and Type D Personality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Literature of the Last 10 Years" Life 15, no. 7: 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071061

APA StyleAl Nakhebi, O. A. S., Albu-Kalinovic, R., Bosun, A., Neda-Stepan, O., Gliga, M., Crișan, C.-A., Marinescu, I., Mornoș, C., & Enatescu, V.-R. (2025). Cardiovascular Diseases and Type D Personality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Literature of the Last 10 Years. Life, 15(7), 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071061