The Therapeutic Approaches Dealing with Malocclusion Type III—Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prevalence and Etiology of Class III

1.2. Diagnosis of Malocclusions

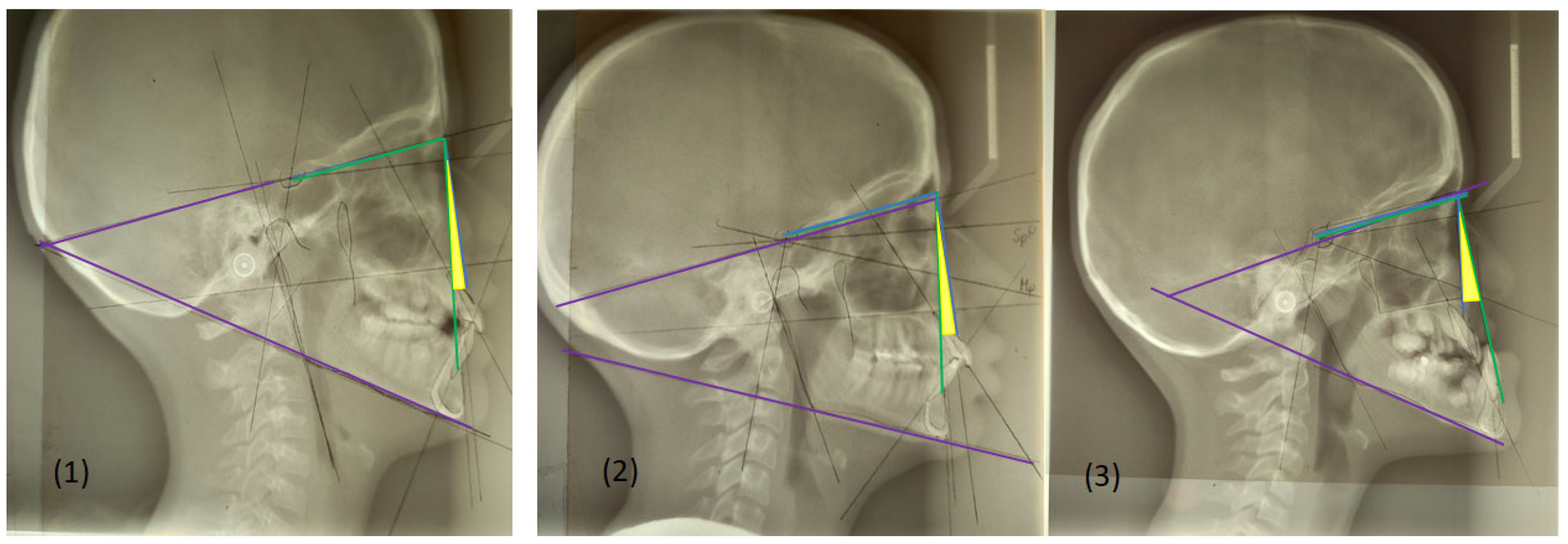

- SNA angle is formed between points of center sella turcica (S) and nasion (N) as the most anterior point of frontonasal suture, and subspinal point of deepest spot of contour of premaxiila (A), which presents the position of maxilla anteriorly or posteriorly to the cranial base. An average value of SNA angle is 80° ± 2°, while a higher value shows that the maxilla is protrusive, and a lower value indicates that the maxilla is more retrusive than normal;

- SNB angle is formed by connecting points of center sella turcica (S) and nasion (N) as the most anterior point of frontonasal suture, and the point that presents the deepest spot of the mandible (B). The average value of SNB is 78° ± 2°. A value above indicates that the mandible is more anterior to the cranial base, or protrusive, and a value below is a more backward, retrusive position;

- ANB angle is the angle between point A-N-B or the difference between SNA and SNB angle, with a normal discrepancy between maxilla and mandible ± 2°. A higher value points to the angle class II malocclusion relationship, while a lower angle indicates the angle class III malocclusion (Figure 2).

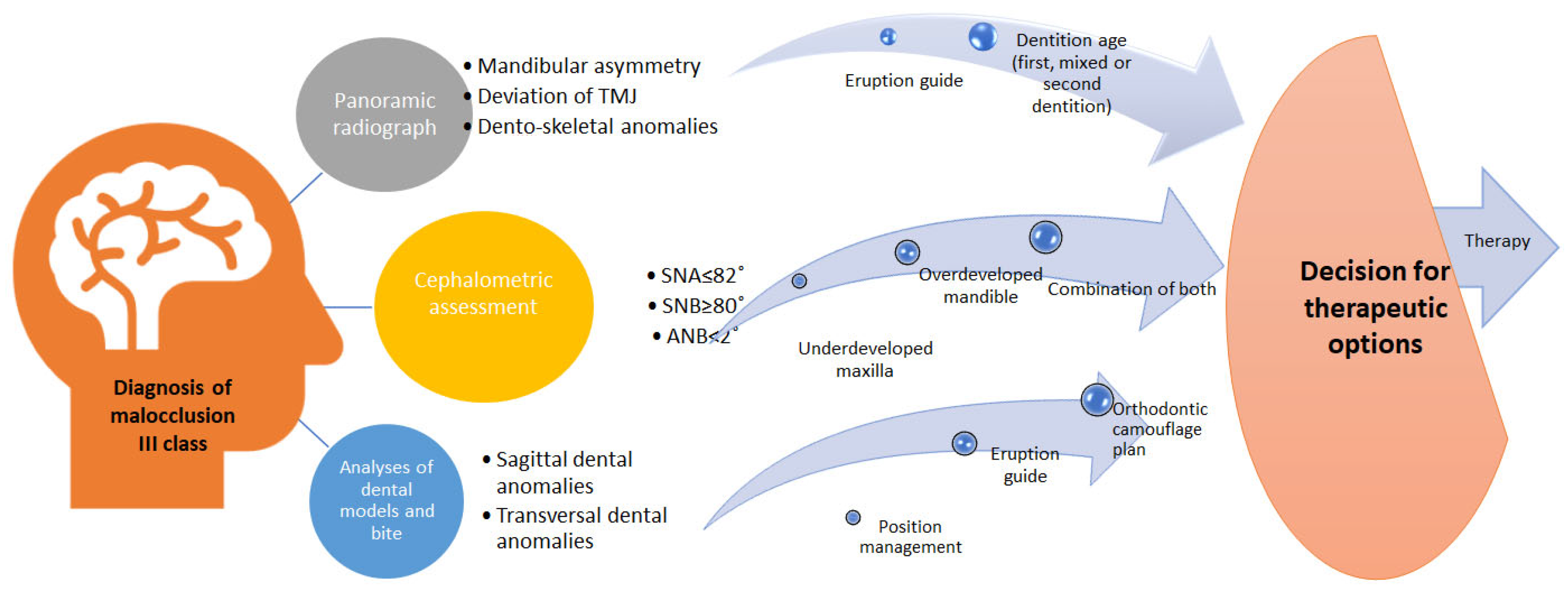

Diagnosis of Malocclusion Type III

- According to study from 2015 significant measurements in diagnosis of skeletal class III are: mandibular prognathism by the sagittal position of the mandible to the anterior cranial base (SNB);

- Prognathism by the anterior sagittal position of the symphysis mentalis to the anterior cranial base plane;

- Mandible hyperdivergent growth;

- Retroinclination of lower teeth;

- Occlusal plane tilting towards the mandible basis;

- Anterior position of TMJ;

- Posterior condylar growth, with the opening of the mandibular angle;

- Facial anterior height growth.

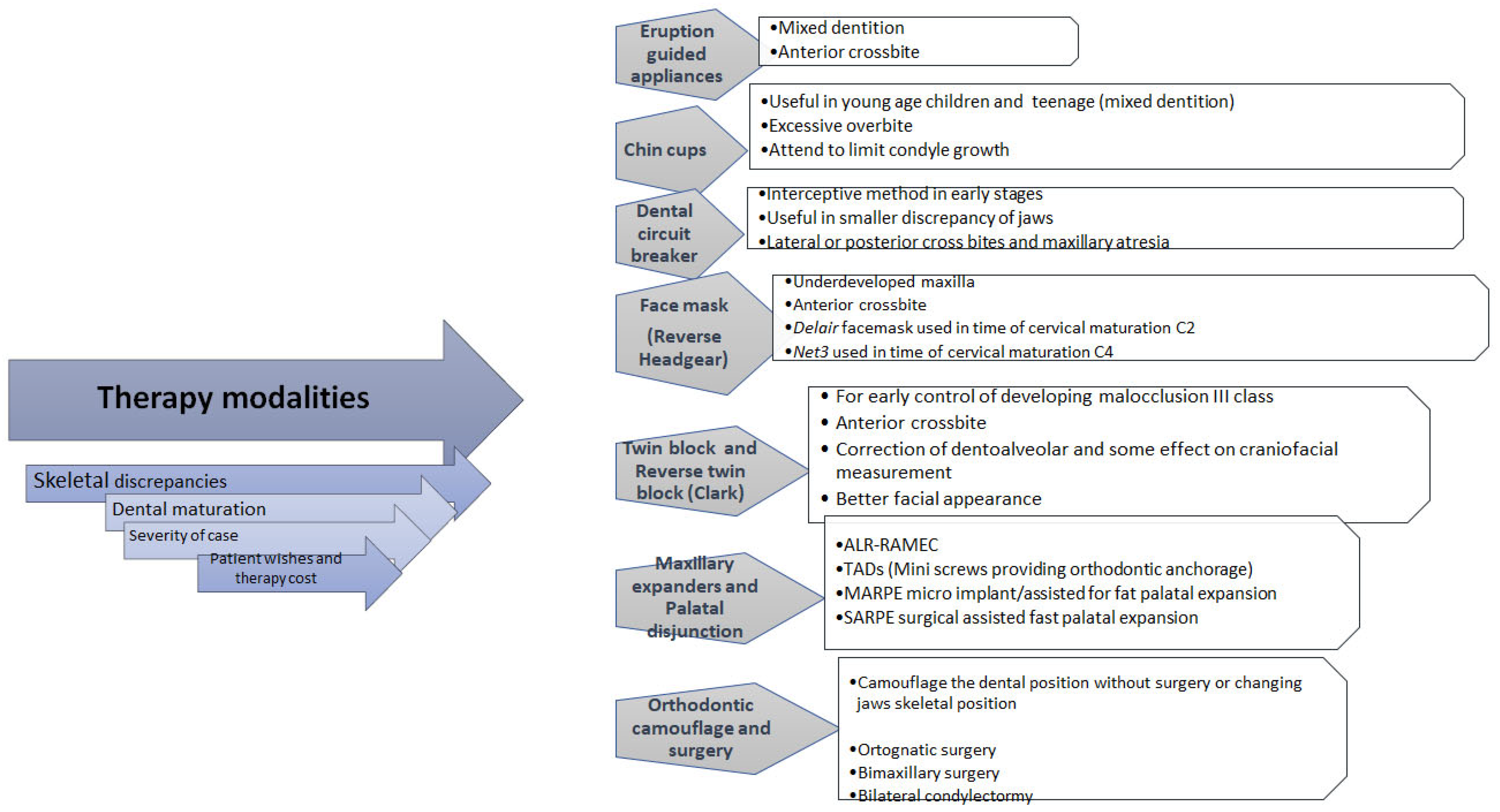

2. Discussion

2.1. Orthopedic Therapy

2.1.1. Eruption Guidance Appliances

2.1.2. Chin Cups

2.1.3. Dental Circuit Breaker

2.1.4. Face Masks

2.1.5. Reverse Twin Block

2.1.6. Maxillary Expanders and Palatal Disjunction

2.2. Orthodontic Therapy

2.3. Surgical Therapy

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghodasra, R.; Brizuela, M. Orthodontics, Malocclusion. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK592395/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Hershfeld, J.J.; Edward, H. Angle and the malocclusion of the teeth. Bull. Hist. Dent. 1979, 27, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Varma, G.; Harsha, B.; Palla, S.; Sravan, S.; Raju, J.; Rajavardhan, K. Genetics in an orthodontic perspective. J. Adv. Clin. Res. Insights 2019, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, E.; Urata, M.; Chen, J.F.; Chai, Y. The clinical manifestations, molecular mechanisms and treatment of craniosynostosis. Dis. Model. Mech. 2022, 15, dmm049390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enzo, B. Malocclusion in orthodontics and oral health: Adopted by the General Assembly: September 2019, San Francisco, United States of America. Int Dent J. 2020, 70, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, N.Z.; McCullagh, A.P.G.; Kennedy, D.B. Management of a Class I malocclusion with traumatically avulsed maxillary central and lateral incisors. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rédua, R.B. Different approaches to the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion during growth: Bionator versus extraoral appliance. Dental Press. J. Orthod. 2020, 25, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azamian, Z.; Shirban, F. Treatment Options for Class III Malocclusion in Growing Patients with Emphasis on Maxillary Protraction. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 8105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.R.; Nayme, J.G.; Garbin, A.J.; Saliba, N.; Garbin, C.A.; Moimaz, S.A. Prevalence of malocclusion and related oral habits in 5- to 6-year-old children. Oral. Health Prev. Dent. 2012, 10, 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Jaradat, M. An Overview of Class III Malocclusion (Prevalence, Etiology and Management). J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2018, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohud, O.; Lone, I.M.; Midlej, K.; Obaida, A.; Masarwa, S.; Schröder, A.; Küchler, E.C.; Nashef, A.; Kassem, F.; Reiser, V.; et al. Towards Genetic Dissection of Skeletal Class III Malocclusion: A Review of Genetic Variations Underlying the Phenotype in Humans and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londono, J.; Ghasemi, S.; Moghaddasi, N.; Baninajarian, H.; Fahimipour, A.; Hashemi, S.; Fathi, A.; Dashti, M. Prevalence of malocclusion in Turkish children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2023, 9, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wu, C.; Lin, J.; Shao, J.; Chen, Q.; Luo, E. Genetic Etiology in Nonsyndromic Mandibular Prognathism. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017, 28, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria-Teixeira, M.C.; Tordera, C.; Salvado, E.; Silva, F.; Vaz-Carneiro, A.; Iglesias-Linares, A. Craniofacial syndromes and class III phenotype: Common genotype fingerprints? A scoping review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 95, 1455–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, L.; Verdonk, S.J.; Zhytnik, L.; Ridwan-Pramana, A.; Gilijamse, M.; Schreuder, W.H.; van Gelderen-Ziesemer, K.A.; Schoenmaker, T.; Micha, D.; Eekhoff, E.M. Dental Abnormalities in Osteogenesis Imperfecta: A Systematic Review. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2024, 115, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Liu, W.; Yang, L.; Yan, P.; Zhong, W.; Gao, X.; Song, J. Craniocervical posture in patients with skeletal malocclusion and its correlation with craniofacial morphology during different growth periods. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhao, T.; Qin, D.; Hua, F.; He, H. The impact of mouth breathing on dentofacial development: A concise review. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 929165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Olivos, L.H.G.; Chacón-Uscamaita, P.R.; Quinto-Argote, A.G.; Pumahualcca, G.; Pérez-Vargas, L.F. Deleterious oral habits related to vertical, transverse and sagittal dental malocclusion in pediatric patients. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Barrera, M.; Ribas-Perez, D.; Caleza Jimenez, C.; Cortes Lillo, O.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A. Oral Habits in Childhood and Occlusal Pathologies: A Cohort Study. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, M.; Hamedi, R.; Khavandegar, Z. The Effect of Thyroid Hormone, Prostaglandin E2, and Calcium Gluconate on Orthodontic Tooth Movement and Root Resorption in Rats. J. Dent. 2015, 16, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanović, Z.; Nikodijević, A.; Udovicić, B.; Milić, J.; Nikolić, P. Size of lower jaw as an early indicator of skeletal class III development. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2008, 65, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, Z.; Nikolić, P.; Nikodijević, A.; Milić, J.; Duka, M. Analysis of variation of sagittal position of the jaw bones in skeletal Class III malocclusion. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2012, 69, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumussoy, I.; Duman, S.B.; Miloglu, O.; Demirsoy, M.S.; Dogan, A.; Abdelkarim, A.Z.; Guller, M.T. Comparative Morphometric Study of the Occipital Condyle in Class III and Class I Skeletal Malocclusion Patients. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunduru, R.; Kailasam, V.; Ananthanarayanan, V. Quantum of incisal compensation in skeletal class III malocclusion: A cross-sectional study. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 50, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinobad, V.; Strajnić, L.; Sinobad, T. Cephalometric evaluation of skeletal relationships after bimaxillary surgical correction of mandibular prognathism. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2021, 78, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okşayan, R.; Aktan, A.M.; Sökücü, O.; Haştar, E.; Ciftci, M.E. Does the panoramic radiography have the power to identify the gonial angle in orthodontics? Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 219708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, G.; Castillo, A.A.D. Cephalometric Radiographic Assessment of Facial Asymmetry. In Dentofacial and Occlusal Asymmetries; Melsen, B., Athanasiou, A.E., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A. A Comprehensive Review of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: Concepts, Trends, and Applications. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M.; Ma, X.; Fagan, M.J.; McIntyre, G.T.; Lin, P.; Sivamurthy, G.; Mossey, P.A. A 3D cephalometric protocol for the accurate quantification of the craniofacial symmetry and facial growth. J. Biol. Eng. 2019, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodasra, R.; Brizuela, M. Orthodontics, Cephalometric Analysis. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594272/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Jha, M.S. Cephalometric Evaluation Based on Steiner’s Analysis on Adults of Bihar. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13, S1360–S1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawaqa, O.; AlNimri, K.S.; Abu Alhaija, E.S. Dentoalveolar characteristics in subjects with different anteroposterior relationships: A retrospective cross-sectional Cone-Beam Computed Tomography study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegan, G.; Dascalu, C.; Radu, M.; Anistoroaei, D. Chephalometric features of class III malocclusion. Rev. Med. Chir. Soc. Med. Nat. Iasi 2015, 119, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Otel, A.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Zubizarreta-Macho, Á. Comparative Analysis of Early Class III Malocclusion Treatments-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2025, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez, G.; Aliaga-Del Castillo, A.; Valerio, M.V.; Maranhão, O.B.V.; Miranda, F.; Janson, G. Effects of eruption guidance appliance in the early treatment of Class III malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2024, 94, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, M.; Caruso, S.; Cantile, T.; Pellegrino, G.; Ferrazzano, G.F. Early Treatment of Anterior Crossbite with Eruption Guidance Appliance: A Case Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Gilani, R.; Kathade, A.; Atey, A.R.; Atole, S.; Rathod, P. The Early Intervention of a Class III Malocclusion with an Anterior Crossbite Using Chincup Therapy: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e62473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.P.; Lin, H.C.; Liu, P.H.; Chang, C.H. Geometric morphometric assessment of treatment effects of maxillary protraction combined with chin cup appliance on the maxillofacial complex. J. Oral Rehabil. 2005, 32, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.A.F.; Baccetti, T.; McNamara, J.A., Jr. Treatment effects of the light-force chincup. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 138, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, A.H.; Burhan, A.S.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Nawaya, F.R. Evaluation of the dimensional changes in the mandible, condyles, and the temporomandibular joint following skeletal class III treatment with chin cup and bonded maxillary bite block using low-dose computed tomography: A single-center, randomized controlled trial. F1000Research 2023, 12, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, T.K.; Le, L.N.; Do, T.T.; Le, K.P.V. Early treatment of skeletal class III malocclusion with facemask therapy in Vietnam. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Alifu, A.; Peng, Y. Is maxillary protraction the earlier the better? A retrospective study on early orthodontic treatment of Class III malocclusion with maxillary deficiency. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarraf, N.E.; Altug, A.T.; Dalci, K.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Dalci, O. Skeletal and dental effects of a new compliance-free appliance, the NET3 corrector, in management of skeletal Class III malocclusion compared to rapid maxillary expansion-facemask. Angle Orthod. 2025, 95, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabellion, M.; Lisson, J.A. Dentofacial and skeletal effects of two orthodontic maxillary protraction protocols: Bone anchors versus facemask. Head. Face Med. 2024, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, L.; Nieri, M.; Marti, P.; Recupero, A.; Volpe, A.; Vichi, A.; Goracci, C. Clinical Management of Facemasks for Early Treatment of Class III Malocclusion: A Survey among SIDO Members. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, M.; Singh, H.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, P. Reverse twin block for interceptive management of developing class III malocclusion. J. Indian. Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2017, 35, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minase, R.A.; Bhad, W.A.; Doshi, U.H. Effectiveness of reverse twin block with lip pads-RME and face mask with RME in the early treatment of class III malocclusion. Prog. Orthod. 2019, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Gyawali, R.; Pokharel, P.R.; Chaudhary, A.; Sangroula, S. Class III Correction With Reverse Twin Block-A Case Report. Clin. Case Rep. 2024, 12, e9700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, E.J.; Tsai, W.C. A new protocol for maxillary protraction in cleft patients: Repetitive weekly protocol of alternate rapid maxillary expansions and constrictions. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2005, 42, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Li, Q.; Ngan, P.; Guan, G.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Lv, C.; Hua, F.; Zhao, T.; He, H. Impact of tonsillectomy on the efficacy of Alt-RAMEC/PFM treatment protocols in children with class III malocclusion and tonsillar hypertrophy: Protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e084703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, P.; Ding, B. A skeletal Class III young adult with severe maxillary transverse deficiency treated with maxillary skeletal expander. Angle Orthod. 2024, 95, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setvaji, N.R.; Sundari, S. Evaluation of Treatment Effects of en Masse Mandibular Arch Distalization Using Skeletal Temporary Anchorage Devices: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e71171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, M.A.; Scheffler, N.R.; Mahy, P.; Siciliano, S.; De Clerck, H.J.; Tulloch, J.F. Modified miniplates for temporary skeletal anchorage in orthodontics: Placement and removal surgeries. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 66, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircelli, B.H.; Pektas, Z.O. Midfacial protraction with skeletally anchored face mask therapy: A novel approach and preliminary results. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, R.A.; Dourado, G.B.; Farias, I.M.; Pithon, M.M.; Neto, J.R.; de Paiva, J.B. Miniscrews as an alternative for orthopedic traction of the maxilla: A case report. APOS Trends Orthod. 2020, 10, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, O.M.; Ramadan, A.A.-F.; Nadim, M.A.; Hamed, T.A.-B. Maxillary protraction using orthodontic miniplates in correction of class III malocclusion during growth. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2016, 5, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.M.; Huang, C.T.; Wang, C.W.; Wang, K.L.; Hsieh, S.C.; Ho, K.H.; Liu, Y.J. Management of Class III Malocclusion with Microimplant-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE) and Mandible Backward Rotation (MBR): A Case Report. Medicina 2024, 60, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.A.; Nguyen, N.A.; Doan, H.L.; Pham, T.H.; Doan, B.N. Management of anterior and posterior crossbites with lingual appliances and miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion: A case report. Medicine 2024, 103, e40832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaharty, M.A.; Ghobashi, S.A.; El-Shorbagy, E. Evaluation of Maxillary Protraction Using a Mini Screw-Retained Palatal C-Shaped Plate and Face Mask. Turk. J. Orthod. 2024, 37, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, R.; Kathade, A.; Singh, S.; Atey, A.R. Achieving Aesthetics and Function in Class III Malocclusion Through Orthodontic Camouflage: A Clinical Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e65063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakale, M.D. Camouflage Orthodontic Treatment of a Severe Class III Malocclusion. Case Rep. Dent. 2025, 2025, 9839448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzini, W.U.; Torres, F.M. Orthodontic Camouflage: A Treatment Option—A Clinical Case Report. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2017, 8, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, M.; Marinkovic, N.; Arsic, I.; Janosevic, P.; Nedeljkovic, N. Treatment of Open Bite Based on Skeletal Anchorage Using Extrusion Lever Arms and Class III Elastics. Case Rep. Dent. 2024, 2024, 7768109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Yu, L.; Sun, W.; Xia, K.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J. Extraction camouflage treatment of a skeletal Class III malocclusion with severe anterior crowding by miniscrews and driftodontics in the mandibular dentition. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria-Teixeira, M.C.; Azevedo-Coutinho, F.; Serrano, Â.D.; Yáñez-Vico, R.M.; Salvado E Silva, F.; Vaz-Carneiro, A.; Iglesias-Linares, A. Orthognathic surgery-related condylar resorption in patients with skeletal class III malocclusion versus class III malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehle, R.; Berger, M.; Saure, D.; Hoffmann, J.; Seeberger, R. High oblique sagittal split osteotomy of the mandible: Assessment of the positions of the mandibular condyles after orthognathic surgery based on cone-beam tomography. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 54, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Han, J.J.; Jung, S.; Kook, M.S.; Park, H.J.; Oh, H.K. Changes in the temporomandibular joint clicking and pain disorders after orthognathic surgery: Comparison of orthodontics-first approach and surgery-first approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, S.; Li, W.; Han, B. Lower incisor position in skeletal Class III malocclusion patients: A comparative study of orthodontic camouflage and orthognathic surgery. Angle Orthod. 2024, 94, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, A.; Ueki, K.; Moroi, A.; Tsutsui, T.; Saito, Y.; Sato, M.; Yoshizawa, K. Changes in cross-sectional measurements of masseter, medial pterygoid muscles, ramus, condyle and occlusal force after bi-maxillary surgery. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, P.C.; Hsin-Chung Cheng, J.; De-Shing Chen, D.; Hsu, C.C.; Cruz Moreira, R.A.; Chou, M.Y. Changes in smile parameters after surgical-orthodontic treatment for skeletal Class III malocclusion. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derquenne, A.; Mercier, J.; Dugast, S.; Guyonvarc’h, P.; Corre, P.; Bertin, H. Application of bilateral condylectomy as an alternative surgical treatment for Class III malocclusion with posterior vertical excess, a technical note. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 125, 101797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.L.; Yang, M.L. Psychological status of patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion undergoing bimaxillary surgery: A comparative study. Medicine 2024, 103, e39435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendl, B.; Stampfl, M.; Muchitsch, A.P.; Droschl, H.; Winsauer, H.; Walter, A.; Wendl, M.; Wendl, T. Long-term skeletal and dental effects of facemask versus chincup treatment in Class III patients: A retrospective study. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2017, 78, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, R.; Jin, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Guo, J. Relative effectiveness of facemask therapy with alternate maxillary expansion and constriction in the early treatment of Class III malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2021, 159, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Steiner Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal analysis | Dental analysis | Soft tissue analiysis |

| SNA SNB ANB Occlusal plane Mandibular plane | Maxillary Incisor Position (U1-NA) angle and distance (2 measurements) Mandibular Incisor Position (L1-NB) angle and distance (2 measurements) Interincisal Angle Lower Incisor to Chin | S-line |

| Class III Characteristics | Cephalometric Parameters |

|---|---|

| Maxillary deficiency | SNA ≤ 82° |

| Mandibular prognathism | SNB ≥ 80° ANB < 2° |

| Maxillary incisor protrusion | Maxillary incisor position U1-NA angle (axial upper incisors relation to NA line) > 22° protrusion < 22° retrusion U1-NA distance (NA distance to the most medial surface of upper incisors) > 4 mm protrusion < 4 mm retrusion |

| Mandibular incisor retrusion | Mandibular incisor position L1-NB angle (axial lower incisors relation to NB line) > 25° protrusion < 25° retrusion L1-NB distance (NB distance to the most medial surface of lower incisors) > 4 mm protrusion < 4 mm retrusion |

| Difference in mandibular effective length | GoGn-SN > 32° vertical growth GoGn-SN < 32° horizontal growth pattern |

| Difference in facial height | According to symmetry of facial a thirds Hairline–Glabella; Glabela–Subnasale; Subnasale–Mention |

| Characteristics of Included Studies | Cephalometric Measures | Evidence Strength | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Year | Therapy Approach | Article Type | Number of Participants | Duration of Therapy (Months) | Age (Years, Mean) | SNA° | SNB° | ANB° | ||||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | ||||||||

| Otel et al. [34] | 2025 | Dental circuit breaker and face mask | Systematic Review Meta-analysis | 20–40 | 6 | 6–12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Strong |

| Alt-RAMEC and face mask | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Disjunction and face mask | |||||||||||||

| Velasquez et al. [35] | 2024 | Eruption guidance appliance | Original article | 44 | 20 | 7.6 | 81.23 | 81.19 | 80.05 | 80.57 | 1.20 | 0.62 | Moderate |

| Pellegrino et al. [36] | 2020 | Eruption guidance appliance | Case report | 1 | 7 | 5.5 | 74.0 | NA | 73.0 | NA | 1.0 | NA | Mild |

| Singh et al. [37] | 2024 | Chin cup | Case report | 1 | 25 | 12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Weak |

| Chang et al. [38] | 2005 | Chin cup | Original article | 20 | 17 | 9.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Barrett et al. [39] | 2010 | Chin cup Chin cup with quad helix | Original article | 26 | 30 | 8.5 | 79.4 | 78.5 | 80.0 | 78.7 | −0.7 | 0.4 | Moderate |

| Husson et al. [40] | 2023 | Chin cup with bonded maxillary bite block | Randomized control study | 38 | 16 | 6.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Strong |

| Ly et al. [41] | 2024 | Face mask and anchorage of a palatal expander | Original article | 31 | 3 | 7–12 | 79.37 | 81.5 | 81.39 | 80.26 | −1.98 | 1.37 | Strong |

| Li et al. [42] | 2024 | Delaire face mask with maxillary expander | Retrospective original study | 97 | NA | 5.91 | 78.29 | 80.01 | 79.36 | 78.29 | −1.06 | 3.85 | Strong |

| 9.05 | 77.93 | 79.71 | 80.19 | 79.48 | −2.27 | 4.96 | |||||||

| 10.60 | 76.76 | 78.58 | 80.73 | 79.33 | −3.96 | 7.15 | |||||||

| Tarraf et al. [43] | 2025 | Net3 corrector RME-face mask combination | Retrospective original study | 20 | 10.5 | 11.14 | 79.40 | 82.54 | 80.47 | 80.62 | −1.10 | 1.92 | Strong |

| 12 | 77.85 | 78.90 | 79.73 | 78.77 | −1.90 | 0.12 | |||||||

| Tabellion et al. [44] | 2024 | Bone anchors and face mask | Original article cephalometric analysis | 31 | 13.5 | 11.0 | 80.13 | 82.43 | 81.63 | 82.34 | −1.51 | 0.08 | Moderate |

| 10.0 | 6.74 | 80.30 | 81.52 | 80.12 | 79.31 | 0.16 | 2.20 | ||||||

| Franchi et al. [45] | 2024 | Face mask | Web-based questionnaire | 151 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Mild |

| Mittal et al. [46] | 2017 | Reverse twin block | Case report | 1 | 10 | 11 | 80.0 | 82.0 | 84.0 | 84.0 | −4.0 | −2.0 | Moderate |

| Minase et al. [47] | 2019 | Reverse twin block | Original article | 39 | 9 | 10.17 | 79.15 | 81.15 | 82.23 | 81.15 | −3.07 | 0 | Strong |

| Face mask | 78.92 | 80.23 | 81.46 | 80.73 | −2.53 | −0.50 | |||||||

| Pandey et al. [48] | 2014 | Reverse twin block | Case report | 1 | 8 | 10 | 82.0 | 82.0 | 80.0 | 82.0 | 2.0 | 0 | Mild |

| Liou et al. [49] | 2005 | Alt-RAMEC | Original article | 26 | 6 | 10.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Guo et al. [50] | 2024 | Alt-RAMEC/PFM | Original | 96 | 1.5 | 5.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Wang et al. [51] | 2024 | Maxillary skeletal expander | Case report | 1 | 39 | 15 | 73.7 | 75.2 | 76.0 | 74.9 | −2.3 | 0.3 | Moderate |

| Setvaji et al. [52] | 2024 | Skeletal Temporary Anchorage Device | Systematic Review | NA | 6–12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Strong |

| Corenelis et al. [53] | 2008 | Miniplates for skeletal temporary anchorage | Original article | 97 | NA | 24.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Kircelli et al. [54] | 2008 | Face mask with skeletal anchorage | Pilot | 6 | 6–8 | 11.8 | 75.0 | 78.7 | 80.3 | 78.0 | −5.2 | 0.9 | Weak |

| Souza et al. [55] | 2020 | Maxillary protraction with mini-screws | Case report | 1 | 16 | 10.0 | 78.0 | 82.0 | 83.0 | 82.0 | −5.0 | 0 | Mild |

| Eid et al. [56] | 2016 | Maxillary protraction with miniplates | Original | 10 | 12 | 10.05 | 77.05 | 76.75 | 80.0 | 81.9 | −2.7 | 1.95 | Moderate |

| Chang et al. [57] | 2024 | Mini-screw palatal expansion | Case report | 1 | 10 | 21.0 | 81.0 | 81.0 | 83.5 | 81.5 | −2.5 | −0.5 | Mild |

| Nguyen et al. [58] | 2024 | Mini-screw palatal expansion | Case report | 1 | 11 | 29.0 | 79.1 | 79.3 | 80.8 | 80.5 | −1.7 | −1.2 | Mild |

| Elsaharty et al. [59] | 2024 | Mini-screw Palatal C-shaped plate face mask | Original article | 16 | 6 | 8.0 | 77.14 | 80.27 | 80.45 | 79.07 | −3.3 | 1.8 | Moderate |

| Ginali et al. [60] | 2024 | Orthodontic camouflage | Case report | 1 | 20 | 19.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Weak |

| Nyakale et al. [61] | 2025 | Orthodontic camouflage | Case report | 1 | 15 | 22.0 | 82.0 | 82.0 | 93.0 | 86 | −11.0 | −4.0 | Mild |

| Mazzini et al. [62] | 2017 | Orthodontic camouflage | Case report | 1 | 17 | 13.0 | 84.0 | 87.0 | 88.0 | 90 | −4.0 | −3.0 | Mild |

| Popov et al. [63] | 2024 | Skeletal anchorage | Case report | 1 | 23 | 26.0 | 78.8 | 79.5 | 77.7 | 78.1 | 1.1 | 1.4 | Mild |

| Zhang et al. [64] | 2025 | Extraction camouflage | Case report | 1 | 31 | 18.0 | 84.9 | 85.2 | 85.3 | 85.1 | −0.4 | 0.1 | Mild |

| Faria-Teixeira et al. [65] | 2025 | Orthodontic surgery | Systematic review | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Strong |

| Kuehle et al. [66] | 2016 | High oblique sagittal split osteotomy | Original article | 50 | 9 | 26.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Zhai et al. [67] | 2020 | Orthognathic surgery | Original article | 182 | NA | 22.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Strong |

| Liu et al. [68] | 2024 | Orthodontic camouflage | Original article, retrospective | 40 in each group | NA | 18.42 | 81.09 | 81.82 | 83.78 | 83.58 | −2.69 | −1.76 | Strong |

| Orthognathic surgery | 21.22 | 80.94 | 83.85 | 84.22 | 81.39 | −3.26 | 2.46 | ||||||

| Takayama et al. [69] | 2019 | Bimaxillary surgery | Original article, | 42 | 24 | NA | 81.5 | 80.9 | 82.6 | 79.7 | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Chiang et al. [70] | 2024 | Orthognathic surgery | Original article, retrospective | 34 | NA | 21.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Moderate |

| Derquenne et al. [71] | 2024 | Bilatteral condilectomy | Short communication | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Mild |

| Wang et al. [72] | 2024 | Bimaxillary surgery | Original article, observational | 205 | NA | 21.9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Strong |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stojanovic, Z.; Đorđević, N.; Bubalo, M.; Stepovic, M.; Rancic, N.; Misovic, M.; Gardasevic, M.; Vulovic, M.; Zivanovic Macuzic, I.; Rosic, V.; et al. The Therapeutic Approaches Dealing with Malocclusion Type III—Narrative Review. Life 2025, 15, 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15060840

Stojanovic Z, Đorđević N, Bubalo M, Stepovic M, Rancic N, Misovic M, Gardasevic M, Vulovic M, Zivanovic Macuzic I, Rosic V, et al. The Therapeutic Approaches Dealing with Malocclusion Type III—Narrative Review. Life. 2025; 15(6):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15060840

Chicago/Turabian StyleStojanovic, Zdenka, Nadica Đorđević, Marija Bubalo, Milos Stepovic, Nemanja Rancic, Miroslav Misovic, Milka Gardasevic, Maja Vulovic, Ivana Zivanovic Macuzic, Vesna Rosic, and et al. 2025. "The Therapeutic Approaches Dealing with Malocclusion Type III—Narrative Review" Life 15, no. 6: 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15060840

APA StyleStojanovic, Z., Đorđević, N., Bubalo, M., Stepovic, M., Rancic, N., Misovic, M., Gardasevic, M., Vulovic, M., Zivanovic Macuzic, I., Rosic, V., Vunjak, N., Delic, S., Jovanovic, K., Tepavcevic, M., Marinkovic, I., & Rajkovic Pavlovic, Z. (2025). The Therapeutic Approaches Dealing with Malocclusion Type III—Narrative Review. Life, 15(6), 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15060840