Impact of Depression on Health-Related Quality of Life in Ulcerative Colitis Patients—Are We Doing Enough? A Single Tertiary Center Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

2.2. Selection of Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Questionnaire on Socio-Demographic Characteristics

2.5. Laboratory Analyses

2.6. Quality of Life Assessment (SIBDQ)

2.7. Depression Symptom Score Assessment (PHQ-9)

2.8. Anxiety Symptom Score Assessment (GAD-7)

2.9. Alexithymia Assessment (TAS-20)

2.10. Statistical Processing and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Patients

3.2. Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis

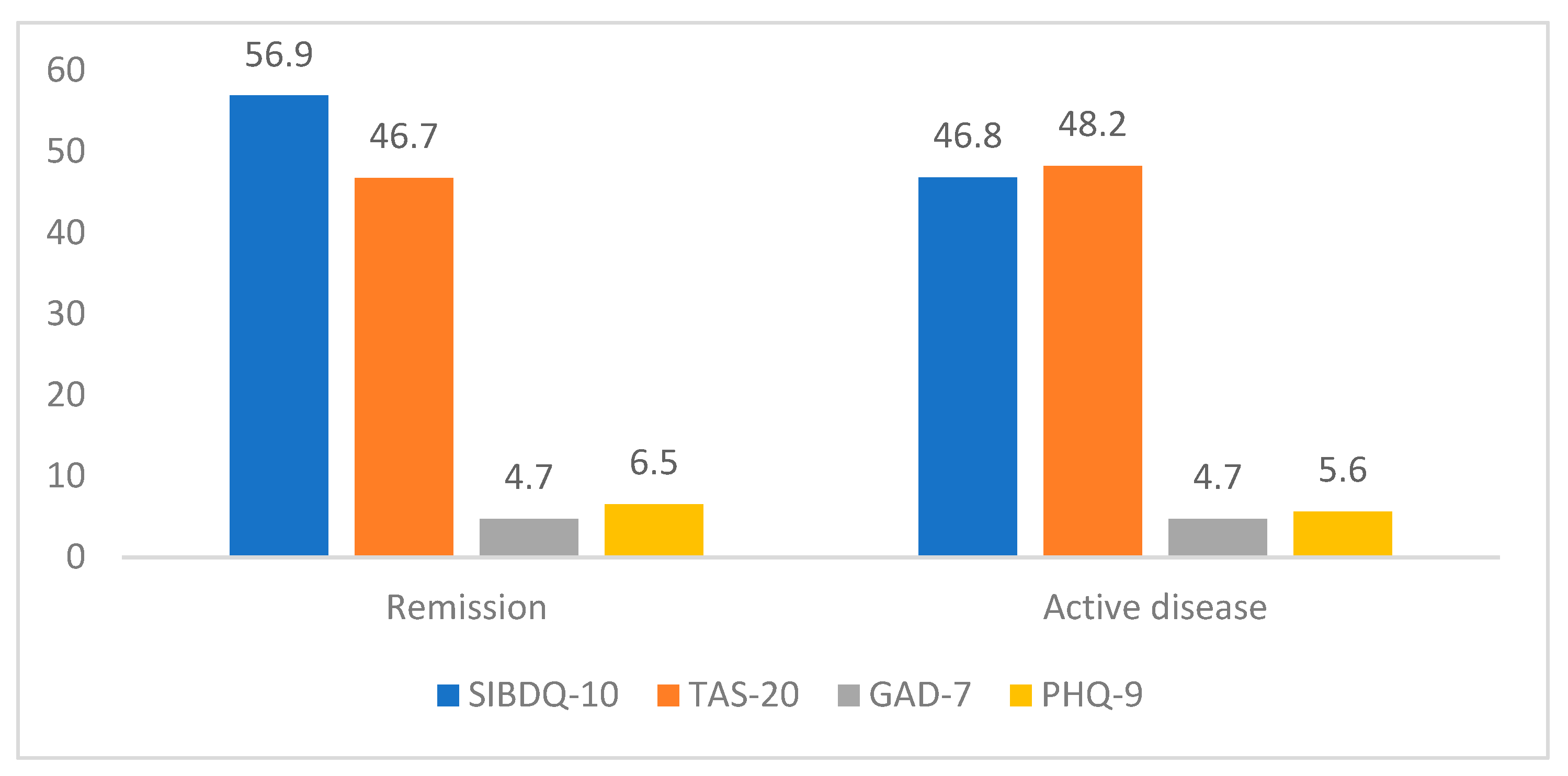

3.3. HRQOL and Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Alexithymia

3.4. Regression Analysis of Factors Associated with SIBDQ Score

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

4.2. Health-Related Quality of Life

4.3. Depression, Anxiety and Alexithymia in UC Patients

4.4. Influence of Depression, Anxiety and Alexithymia on HRQOL

4.5. Other Factors Influencing HRQOL—Possible Role of Gut–Brain Axis and Genetic Factors?

4.6. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

- -

- The study focused on an important clinical issue: the psychological burden of UC and its effects on HRQOL.

- -

- We simultaneously investigated HRQOL and anxiety/depression status, along with the clinical and demographic characteristics of a large group of UC patients.

- -

- The institution where the study was conducted is a tertiary center and mainly treats patients with more severe and complex disease behaviors. A multicenter study, with a larger number of patients and more patients on conventional therapy, would provide a more accurate assessment of HRQOL, as well as the prevalence of anxiety, depression and alexithymia in the population of patients with UC as a whole.

- -

- A cross-sectional study design cannot reveal the direction of causal relationships between psychological disorders, UC and HRQOL and the long-term impact of psychological factors on disease progression and HRQOL.

- -

- In this study, self-administered questionnaires were used, which were completed by the participant on their symptoms of anxiety, depression, and alexithymia at the time of assessment.

- -

- Questionnaires are not used for diagnosing psychiatric disorders, but they can be used for screening and identifying patients who require further psychiatric evaluation. The gold standard for diagnosing these disorders remains a psychiatric interview.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| SIBDQ | Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire |

| PHQ- 9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| GAD-7 | General Anxiety Disorder-7 |

| TAS-20 | Toronto Alexithymia Scale |

References

- Liu, D.; Saikam, V.; Skrada, K.A.; Merlin, D.; Iyer, S.S. Inflammatory bowel disease biomarkers. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 1856–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, D.J.; Noble, A.J.; Justinich, C.J.; Duffin, J.M. A tale of two diseases: The history of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis. 2014, 8, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, G.; Hracs, L.; Windsor, J.; Gorospe, J.; Cummings, M.; Coward, S.; Buie, M.; Quan, J.; Goddard, Q.; Caplan, L.; et al. The Global Evolution of Inflammatory Bowel Disease across Four Epidemiologic Stages. Res. Sq. 2024; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Brazier, J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: What is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics 2016, 34, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, Z.; Singh, H.; Targownik, L.; Strome, T.; Snider, C.; Bernstein, C.N. Predictors of emergency department use by persons with inflammatory bowel diseases: A population-based study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 2907–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; et al. International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.J.; Choi, C.H.; Jung, S.A.; Song, G.A.; Kim, Y.J.; Koo, J.S.; Shin, S.J.; Seo, G.S.; Lee, K.M.; Jang, B.I.; et al. Anxiety and Depression Are Associated with Poor Long-term Quality of Life in Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis: Results of a 3-Year Longitudinal Study of the MOSAIK Cohort. Gut Liver 2024, 19, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.R.; Lee, C.K.; Hong, S.N.; Im, J.P.; Ye, B.D.; Cha, J.M.; Jung, S.A.; Lee, K.M.; Park, D.I.; Jeen, Y.T.; et al. MOSAIK study group of the Korean Association for Study of Intestinal Diseases. Unmet Psychosocial Needs of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Ulcerative Colitis: Results from the Nationwide Prospective Cohort Study in Korea. Gut Liver 2020, 14, 459–467, Erratum in Gut Liver 2021, 15, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.R.; Ediger, J.P.; Graff, L.A.; Greenfeld, J.M.; Clara, I.; Lix, L.; Rawsthorne, P.; Miller, N.; Rogala, L.; McPhail, C.M.; et al. The Manitoba IBD cohort study: A population-based study of the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month anxiety and mood disorders. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remes, O.; Brayne, C.; van der Linde, R.; Lafortune, L. A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations. Brain Behav. 2016, 6, e00497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-de la Torre, J.; Vilagut, G.; Ronaldson, A.; Serrano-Blanco, A.; Martín, V.; Peters, M.; Valderas, J.M.; Dregan, A.; Alonso, J. Prevalence and variability of current depressive disorder in 27 European countries: A population-based study. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e729–e738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Ellul, P.; Langhorst, J.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Acosta, M.B.-D.; Basnayake, C.; Ding, N.J.S.; Gilardi, D.; Katsanos, K.; Moser, G.; et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation Topical Review on Complementary Medicine and Psychotherapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis. 2019, 13, 673–685e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, P.; Barrett, K.; Nijher, M.; de Lusignan, S. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in people with inflammatory bowel disease and associated healthcare use: Population-based cohort study. BMJ Ment. Health 2021, 24, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberio, B.; Zamani, M.; Black, C.J.; Savarino, E.V.; Ford, A.C. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, T.H.; Allin, K.H.; Elmahdi, R.; Jess, T. The bidirectional risk of inflammatory bowel disease and anxiety or depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2023, 83, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, T.H.; Allin, K.H.; Keefer, L.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Jess, T. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: Epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, S.; Pansieri, C.; Piovani, D.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Tsantes, A.G.; Brunetta, E.; Tsantes, A.E.; Bonovas, S. The Brain-Gut Axis: Psychological Functioning and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzani, M.; Jahromi, S.R.; Ghorbani, Z.; Vahabizad, F.; Martelletti, P.; Ghaemi, A.; Sacco, S.; Togha, M.; School of Advanced Studies of the European Headache Federation (EHF-SAS). Gut-brain Axis and migraine headache: A comprehensive review. J. Headache Pain. 2020, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordi, S.B.U.; Lang, B.M.; Auschra, B.; von Känel, R.; Biedermann, L.; Greuter, T.; Schreiner, P.; Rogler, G.; Krupka, N.; Sulz, M.C.; et al. Depressive symptoms predict clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrass, K.M.; Gracie, D.J.; Ford, A.C. Relative Contribution of Disease Activity and Psychological Health to Prognosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease During 6.5 Years of Longitudinal Follow-Up. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narula, N.; Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Calo, N.C.; Ford, A.C.; Bercik, P.; Reinisch, W.; Moayyedi, P. Anxiety but Not Depression Predicts Poor Outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lontai, L.; Elek, L.P.; Balogh, F.; Angyal, D.; Pajkossy, P.; Gonczi, L.; Lakatos, P.L.; Iliás, Á. Burden of Mental Health among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Cross-Sectional Study from a Tertiary IBD Center in Hungary. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Barbera, D.; Bonanno, B.; Rumeo, M.V.; Alabastro, V.; Frenda, M.; Massihnia, E.; Morgante, M.C.; Sideli, L.; Craxì, A.; Cappello, M.; et al. Alexithymia and personality traits of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifneos, P.E. The prevalence of ‘alexithymic’ characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother. Psychosom. 1973, 22, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velde, J.; Servaas, M.N.; Goerlich, K.S.; Bruggeman, R.; Horton, P.; Costafreda, S.G.; Aleman, A. Neural correlates of alexithymia: A meta-analysis of emotion processing studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, G.; Caputo, A.; Schwarz, P.; Bellone, F.; Fries, W.; Quattropani, M.C.; Vicario, C.M. Alexithymia and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaldaferri, F.; D’Onofrio, A.M.; Calia, R.; Di Vincenzo, F.; Ferrajoli, G.F.; Petito, V.; Maggio, E.; Pafundi, P.C.; Napolitano, D.; Masi, L.; et al. Gut Microbiota Signatures Are Associated with Psychopathological Profiles in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Results from an Italian Tertiary IBD Center. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 1805–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.T.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Siegel, C.A.; Sauer, B.G.; Long, M.D. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaser, C.; Sturm, A.; Vavricka, S.R.; Kucharzik, T.; Fiorino, G.; Annese, V.; Calabrese, E.; Baumgart, D.C.; Bettenworth, D.; Borralho Nunes, P.; et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, M.S.; Satsangi, J.; Ahmad, T.; Arnott, I.D.; Bernstein, C.N.; Brant, S.R.; Caprilli, R.; Colombel, J.F.; Gasche, C.; Geboes, K.; et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 19, 5A–36A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, E.J.; Zhou, Q.; Thompson, A.K. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: A quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1996, 91, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care. 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.M.; Mithal, A.; Deyhim, T.; Rabinowitz, L.G.; Olagoke, O.; Freedman, S.D.; Cheifetz, A.S.; Ballou, S.K.; Papamichael, K. Morning Salivary Cortisol Has a Positive Correlation with GAD-7 Scores in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagby, R.M.; Parker, J.D.; Taylor, G.J. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale--I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.C.; Lyra, A.C.; Rocha, R.; Santana, G.O. Epidemiology, demographic characteristics and prognostic predictors of ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 9458–9467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.J.; Wang, Y.K.; Zhang, S.M.; Ren, M.D.; He, S.X. Global burden of inflammatory bowel disease 1990–2019: A systematic examination of the disease burden and twenty-year forecast. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 5751–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.M.; Çolak, Y.; Vedel-Krogh, S.; Kobylecki, C.J.; Bojesen, S.E.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in smokers lacks causal evidence. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 37, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, B.; Honap, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease across the Ages in the Era of Advanced Therapies. J. Crohns Colitis. 2024, 18 (Suppl. S2), ii3–ii15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, K.H.; Klump, B.; Gregor, M.; Meisner, C.; Haeuser, W. Determinants of life satisfaction in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2005, 11, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, E.J. Quality of life of patients with ulcerative colitis: Past, present, and future. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellas, F.; Barreiro de Acosta, M.; Iglesias, M.; Robles, V.; Nos, P.; Aguas, M.; Riestra, S.; de Francisco, R.; Papo, M.; Borruel, N. Mucosal healing restores normal health and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 24, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larussa, T.; Flauti, D.; Abenavoli, L.; Boccuto, L.; Suraci, E.; Marasco, R.; Imeneo, M.; Luzza, F. The Reality of Patient-Reported Outcomes of Health-Related Quality of Life in an Italian Cohort of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results from a Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarian, A.; Bishay, K.; Gholami, R.; Scaffidi, M.A.; Khan, R.; Cohen-Lyons, D.; Griller, N.; Satchwell, J.B.; Baker, J.P.; Grover, S.C.; et al. Factors Associated with Poor Quality of Life in a Canadian Cohort of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2020, 4, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitropoulou, M.A.; Fradelos, E.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Malli, F.; Tsaras, K.; Christodoulou, N.G.; Papathanasiou, I.V. Quality of Life in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Importance of Psychological Symptoms. Cureus 2022, 14, e28502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, R.K.; Naegeli, A.N.; Harrison, R.W.; Moore, P.C.; Mackey, R.H.; Crabtree, M.M.; Lemay, C.A.; Arora, V.; Morris, N.; Sontag, A.; et al. Disease Burden and Patient-Reported Outcomes Among Ulcerative Colitis Patients According to Therapy at Enrollment into CorEvitas’ Inflammatory Bowel Disease Registry. Crohns Colitis 2022, 4, otac007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, K.; Mosli, M.H.; Parker, C.E.; MacDonald, J.K. The impact of biological interventions for ulcerative colitis on health-related quality of life. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD008655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armuzzi, A.; Liguori, G. Quality of life in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and the impact of treatment: A narrative review. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panés, J.; Vermeire, S.; Lindsay, J.O.; Sands, B.E.; Su, C.; Friedman, G.; Zhang, H.; Yarlas, A.; Bayliss, M.; Maher, S.; et al. Tofacitinib in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Health-Related Quality of Life in Phase 3 Randomised Controlled Induction and Maintenance Studies. J. Crohns Colitis. 2018, 12, 145–156, Erratum in J. Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikocka-Walus, A.; Knowles, S.R.; Keefer, L.; Graff, L. Controversies revisited: A systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, B.; Duan, Z.; Xia, Z.; Ding, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Yang, B.; Wang, X.; et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with active ulcerative colitis: Crosstalk of gut microbiota, metabolomics and proteomics. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1987779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, G.; Rosenfeld, G.; Leung, Y.; Qian, H.; Raudzus, J.; Nunez, C.; Bressler, B. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2017, 6496727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR, 4th ed.; text rev; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stroie, T.; Preda, C.; Meianu, C.; Croitoru, A.; Gheorghe, L.; Gheorghe, C.; Diculescu, M. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Clinical Remission: What Should We Look For? Medicina 2022, 58, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcelli, P.; Zaka, S.; Leoci, C.; Centonze, S.; Taylor, G.J. Alexithymia in inflammatory bowel disease. A case-control study. Psychother. Psychosom. 1995, 64, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias-Rey, M.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Caamaño-Isorna, F.; Vázquez Rodríguez, I.; Lorenzo González, A.; Bello-Paderne, X.; Domínguez-Muñoz, J.E. Influence of alexithymia on health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: Are there any related factors? Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 47, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Nunotani, M.; Aoyama, N. Construction of an Explanatory Model for Quality of Life in Outpatients with Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2023, 8, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luqman, A.; He, M.; Hassan, A.; Ullah, M.; Zhang, L.; Rashid Khan, M.; Din, A.U.; Ullah, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, G. Mood and microbes: A comprehensive review of intestinal microbiota’s impact on depression. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1295766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, Y.; He, Y. The variation characteristics of fecal microbiota in remission UC patients with anxiety and depression. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1237256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, A.J.; Davis, J.A.; Dawson, S.L.; Loughman, A.; Collier, F.; O’Hely, M.; Simpson, C.A.; Green, J.; Marx, W.; Hair, C.; et al. A systematic review of gut microbiota composition in observational studies of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1920–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xu, Z.; Noordam, R.; van Heemst, D.; Li-Gao, R. Depression and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Bidirectional Two-sample Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Crohns Colitis. 2022, 16, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Chen, C.L.; He, J.; Liu, S.D. Causal associations between inflammatory bowel disease and anxiety: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 5872–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex (%) Male Female | 117 (47.2) 131 (52.8) |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 45 ± 15 |

| Educational level (%) Primary school Secondary school College Faculty | 12 (4.8) 130 (52.4) 31 (12.5) 75 (30.2) |

| Working status (%) Permanent job Temporary job Unemployed Retired | 137 (55.5) 21 (8.5) 45 (18.2) 44 (17.8) |

| Marital status (%) Married Extramarital union Widowed Divorced Single | 129 (52.0) 16 (6.5) 14 (5.6) 21 (8.5) 68 (27.4) |

| Income level (%) <RSD 50,000 RSD 50–100,000 >RSD 100,000 | 97 (39.9) 126 (51.9) 20 (8.2) |

| Smoking status (%) Non-smoker Smoker Ex-smoker | 156 (62.9) 50 (20.2) 42 (16.9) |

| Alcohol consumption (%) Never Up to 1 glass/day On occasion | 124 (50.0) 4 (1.6) 120 (48.4) |

| Variable | Value | Accepted Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 36 ± 14 | |

| Age at diagnosis (%) <16 years of age 17–40 years of age >40 years of age | 12 (4.8) 161 (64.9) 75 (30.2) | |

| Disease duration (years) | 9.3 ± 7.4 | |

| CRP (g/L) (median, range) | 1.7 (0–298.7) | 0–5 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 139.7 ± 17.3 | 120–160 |

| Iron (μmolL) | 14.9 ± 7.6 | 11–32 |

| Ferritin (μgL) (median, range) | 48.5 (0.9–580) | 30–100 |

| Calprotectin (μg/g) (median, range) | 81.45 (0–2000) | 0–100 |

| In remission at the time of the study (%) Yes No | 237 (95.6) 11 (4.4) | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations of disease (%) Yes No | 56 (22.6) 192 (77.4) | |

| Presence of comorbidity (%) Yes No | 58 (23.4) 190 (76.6) | |

| Prior mental disorder (%) Yes No | 1 (0.4) 247 (99.6) | |

| IBD therapy (%) Mesalazine Corticosteroid treatment in last year Immunosuppressants Azathioprine Methotrexate Advanced therapies Infliximab Infliximab biosimilar Adalimumab Adalimumab biosimilar Vedolizumab Tofacitinib | 123 (49.6) 10 (4.0) 129 (52.0) 115 14 198 (79.8) 23 83 34 2 52 4 |

| Variable | Value | Score Range |

|---|---|---|

| SIBDQ (range) | 56.5 ± 10.9 (16–70) | 10–70 |

| SIBDQ categories (%) Poor HRQOL Optimal HRQOL | 61 (24.6) 187 (75.4) | SIBDQ < 50 SIBDQ ≥ 50 |

| PHQ-9 total score (range) | 5.2 ± 4.5 (0–27) | 0–27 |

| PHQ-9 categories (%) None–minimal depression Mild depression Moderate depression Moderately severe depression Severe depression | 137 (55.2) 75 (30.2) 25 (10.1) 9 (3.6) 2 (0.8) | 0–4 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–27 |

| GAD-7 total score (range) | 4.3 ± 4.7 (0–21) | 0–21 |

| GAD-7 categories (%) Minimal anxiety Mild anxiety Moderate anxiety Severe anxiety | 163 (65.7) 51 (20.6) 21 (8.5) 13 (5.2) | 0–4 5–9 10–14 15–21 |

| TAS-20 total score (range) | 46.7 ± 12.3 (20–94) | 20–100 |

| TAS-20 categories (%) No alexithymia Possible alexithymia Alexithymia present | 173 (69.8) 41 (16.5) 34 (13.7) | 20–51 52–60 61–100 |

| Variable | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Score | Correlation with SIBDQ | |

| PHQ-9 categories None–minimal depression Mild depression Moderate depression Moderate-severe depression Severe depression | 61.6 ± 7.2 53.7 ± 9.4 46.1 ± 11.6 37.1 ± 8.5 29.0 ± 5.7 | r = −0.584 p < 0.001 |

| GAD-7 categories Minimal anxiety Mild anxiety Moderate anxiety Severe anxiety | 59.4 ± 8.7 54.8 ± 11.0 50.2 ± 9.4 36.4 ± 11.3 | r = −0.398 p < 0.001 |

| TAS-20 categories No alexithymia Possible alexithymia Alexithymia present | 58.6 ± 10.0 54.2 ± 11.0 48.2 ± 10.8 | r = −0.339 p < 0.001 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE (B) | β | B | SE (B) | β | B | SE (B) | β | |

| Sex | 0.64 | 1.39 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 1.37 | 0.04 | −1.24 | 1.05 | −0.06 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 |

| Disease duration | −0.01 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.03 | |||

| Remission yes vs. no | 9.62 | 3.32 | 0.20 | 9.10 | 2.53 | 0.17 | |||

| Extraintestinal manifestations yes vs. no | −3.28 | 1.63 | −0.13 | −0.54 | 1.26 | −0.02 | |||

| Advanced therapy treatment yes vs. no | −0.55 | 1.86 | −0.02 | 0.65 | 1.42 | 0.02 | |||

| PHQ-9 total score | −1.47 | 0.19 | −0.62 | ||||||

| GAD-7 total score | −0.13 | 0.18 | −0.06 | ||||||

| TAS-20 total score | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.004 | 0.057 | 0.463 | ||||||

| F for change in R2 | 0.525 | 2.904 | 25.776 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaksic, D.; Vuksanovic, S.; Toplicanin, A.; Spiric-Milovancevic, J.; Maric, G.; Sokic-Milutinovic, A. Impact of Depression on Health-Related Quality of Life in Ulcerative Colitis Patients—Are We Doing Enough? A Single Tertiary Center Experience. Life 2025, 15, 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15040612

Jaksic D, Vuksanovic S, Toplicanin A, Spiric-Milovancevic J, Maric G, Sokic-Milutinovic A. Impact of Depression on Health-Related Quality of Life in Ulcerative Colitis Patients—Are We Doing Enough? A Single Tertiary Center Experience. Life. 2025; 15(4):612. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15040612

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaksic, Dunja, Sasa Vuksanovic, Aleksandar Toplicanin, Jelena Spiric-Milovancevic, Gorica Maric, and Aleksandra Sokic-Milutinovic. 2025. "Impact of Depression on Health-Related Quality of Life in Ulcerative Colitis Patients—Are We Doing Enough? A Single Tertiary Center Experience" Life 15, no. 4: 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15040612

APA StyleJaksic, D., Vuksanovic, S., Toplicanin, A., Spiric-Milovancevic, J., Maric, G., & Sokic-Milutinovic, A. (2025). Impact of Depression on Health-Related Quality of Life in Ulcerative Colitis Patients—Are We Doing Enough? A Single Tertiary Center Experience. Life, 15(4), 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15040612