In Vivo Assessment of Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Aqueous Extracts of Nepeta nuda ssp. nuda L. in Experimental Model of Peripheral Inflammation in Male Long Evans Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Plant Material and Preparation and Composition of Plant Extracts

2.3. Animals

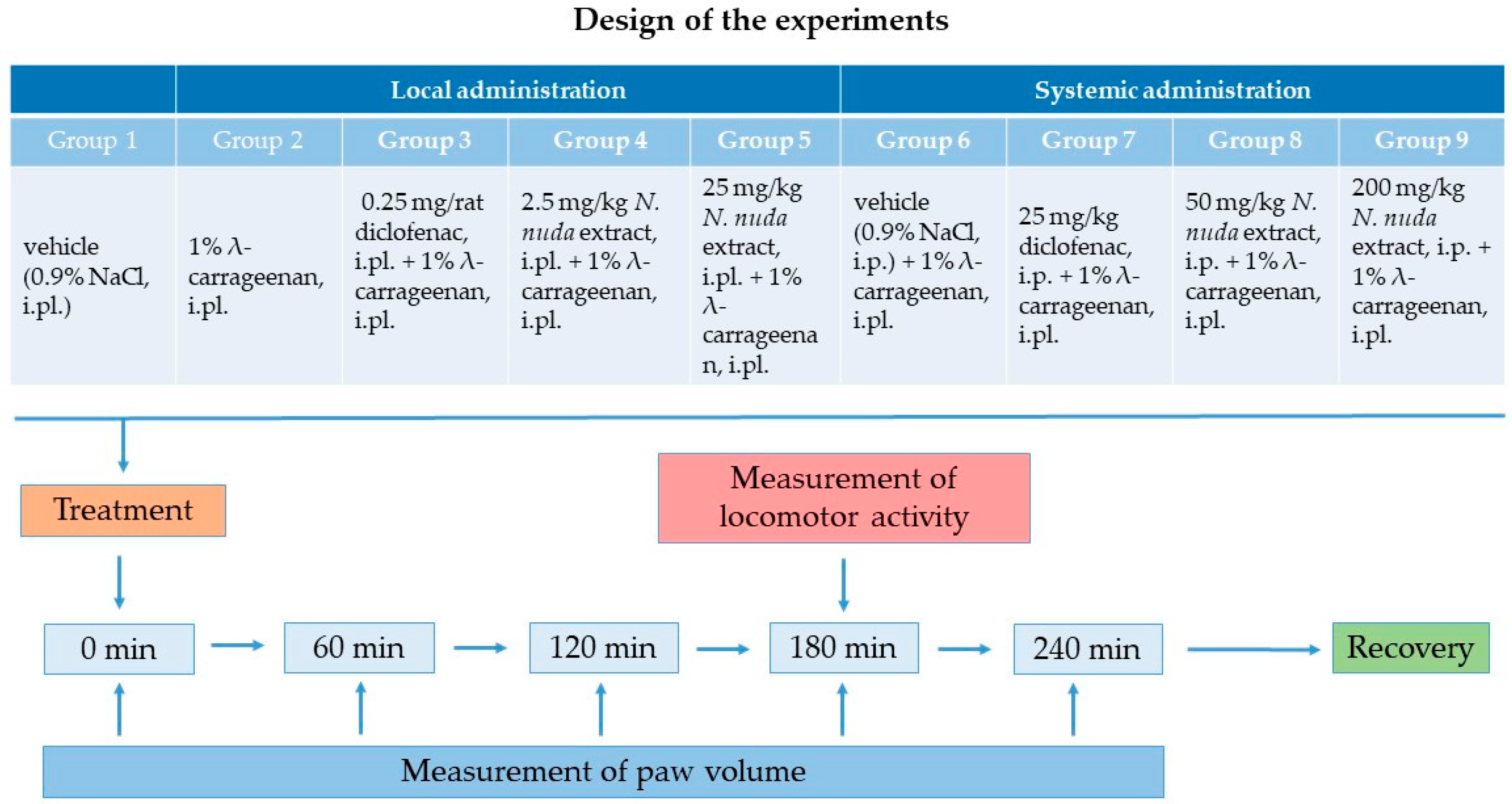

2.4. Experimental Protocol and Groups

- Groups with carrageenan-induced paw edema with intraplantar (local) administration of anti-inflammatory agents:

- Control group with intraplantar injection of vehicle (0.9% sterile normal saline) into the hind paw of rats to eliminate the possible effect of the injection itself; this group was common to both routes of application;

- A group with λ-carrageenan (1% w/v carrageenan in 0.9% normal saline) intraplantarly injected into the hind paw of rats;

- A positive control group with local administration of diclofenac as a standard anti-inflammatory drug (0.25 mg/rat), intraplantarly injected into the carrageenan-treated hind paw of rats;

- Two groups with local administration of N. nuda extract intraplantarly injected into the carrageenan-treated hind paw at doses corresponding to 2.5 mg/kg or 25 mg/kg, respectively.

- Groups with carrageenan-induced paw edema with systemic administration of anti-inflammatory reagents:

- A placebo group with intraperitoneal injection of vehicle (0.9% sterile normal saline);

- A positive control group with intraperitoneal injection of diclofenac at a dosage of 25 mg/kg;

- Two groups with N. nuda extract intraperitoneally injected at doses of 50 mg/kg or 200 mg/kg, respectively.

2.5. Measurement of Carrageenan-Induced Paw Edema

2.6. Measurement of Spontaneous Motor Activity

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

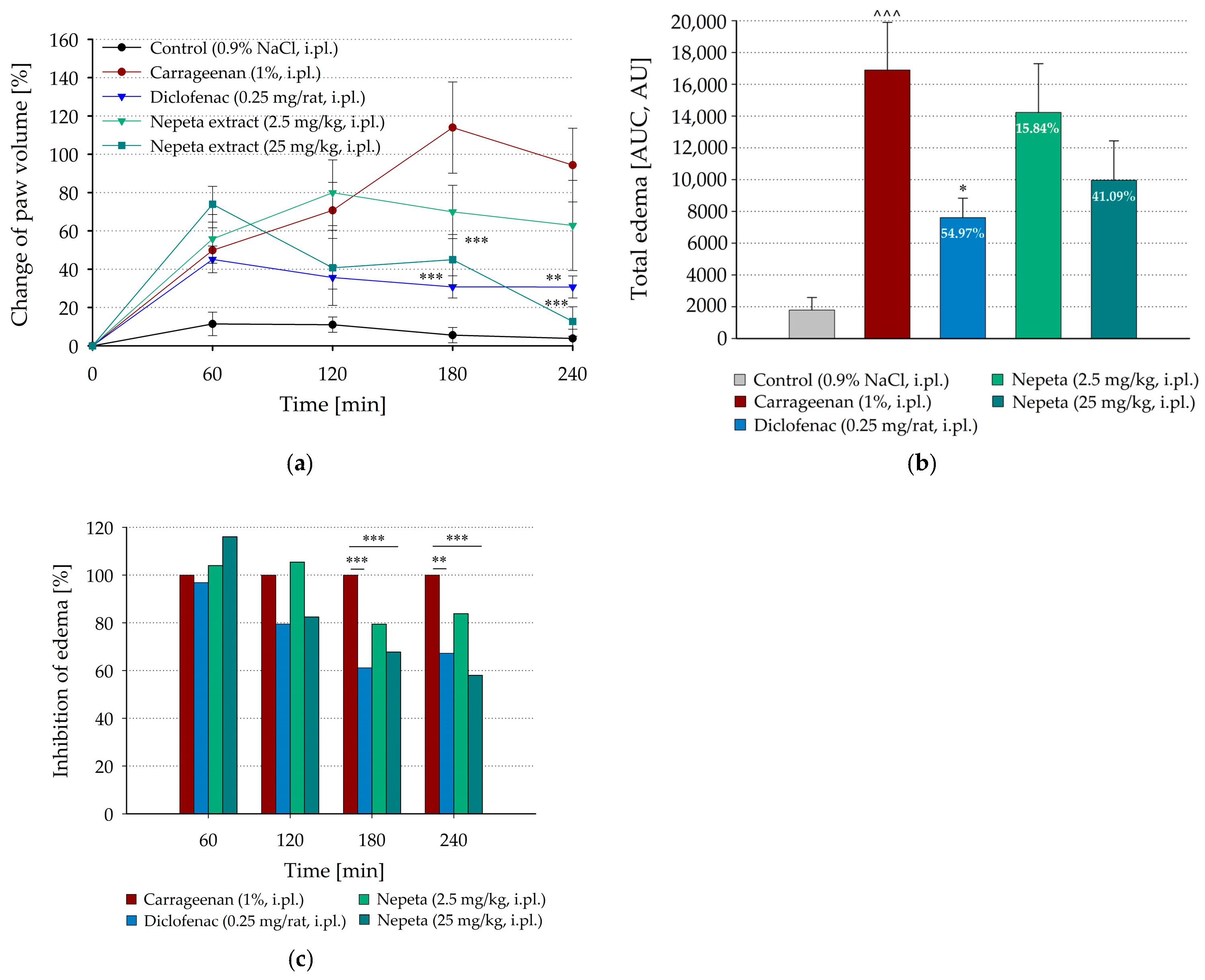

3.1. Inhibition of Carrageenan-Induced Paw Edema by Local Administration of N. nuda in Rat

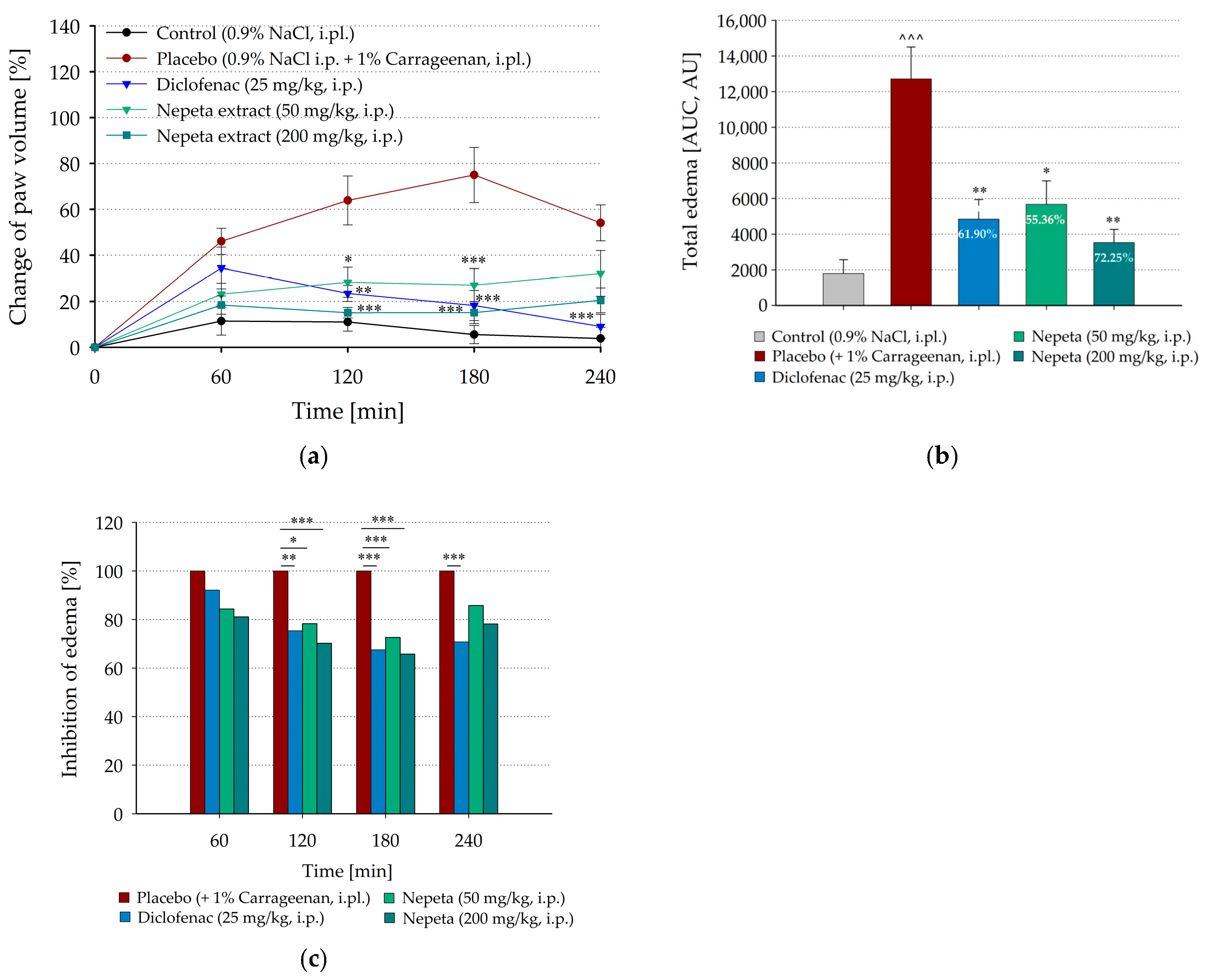

3.2. Inhibition of Carrageenan-Induced Paw Edema by Systemic Administration of N. nuda in Rat

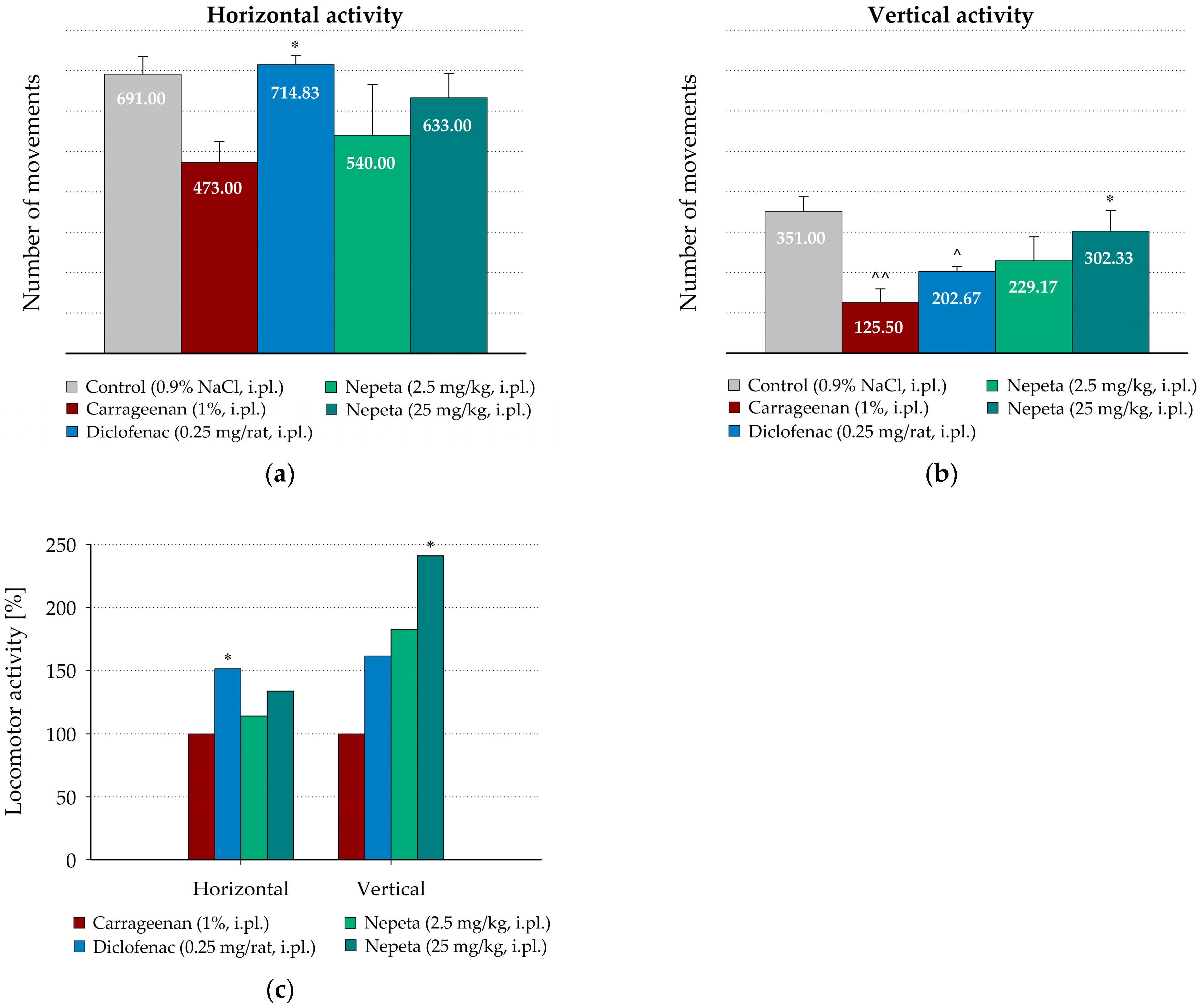

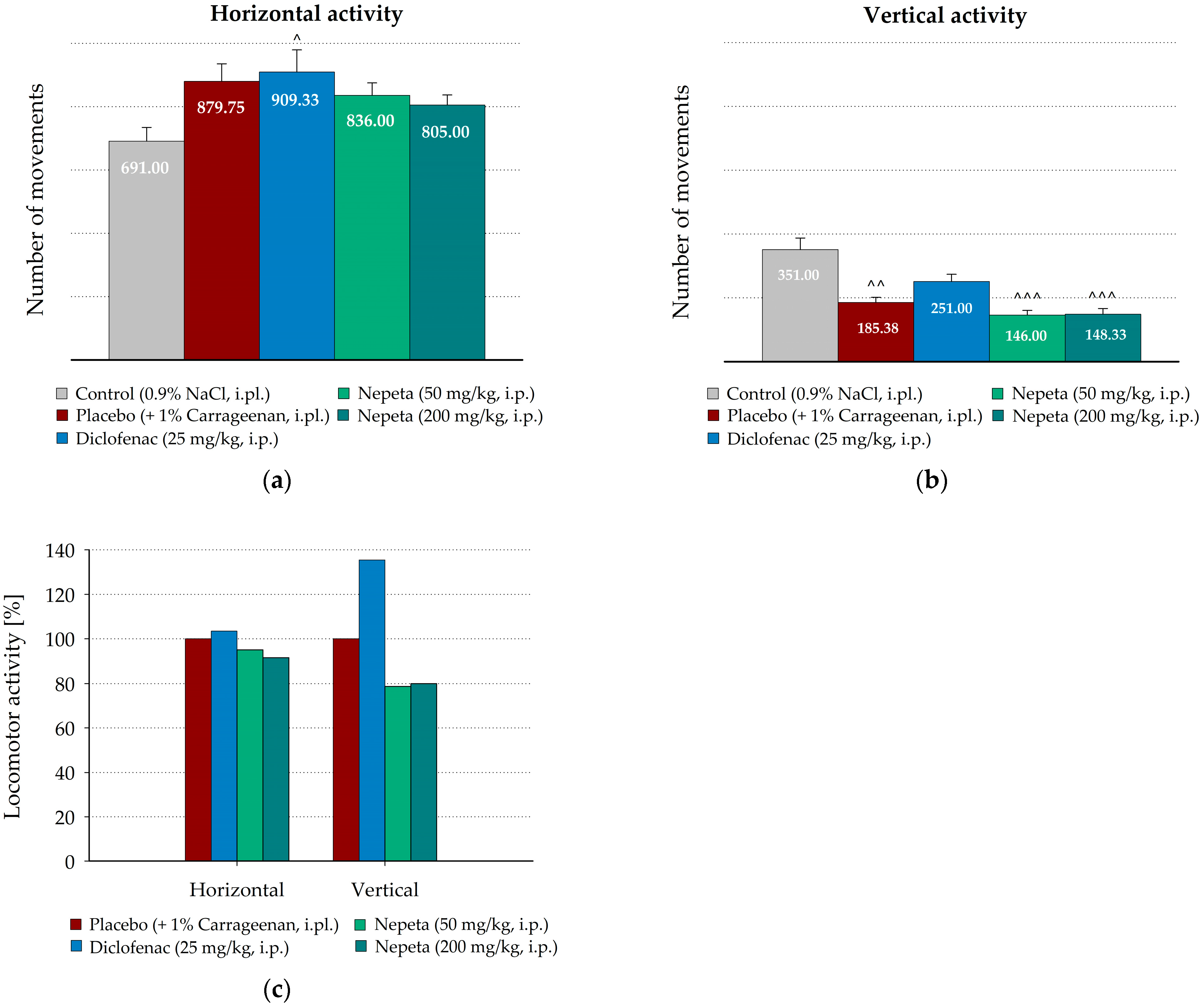

3.3. Measurement of N. nuda Effects on the Spontaneous Motor Activity During Carrageenan-Induced Inflammation in Rat

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| AU | Arbitrary unit |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

References

- Sherwood, E.R.; Toliver-Kinsky, T. Mechanisms of the inflammatory response. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2004, 18, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhelha, R.C.; Haddad, H.; Ribeiro, L.; Heleno, S.A.; Carocho, M.; Barros, L. Inflammation: What’s There and What’s New? Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, W.D.; Fasano, A.; Miller, W.G.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhol, N.K.; Bhanjadeo, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Dash, U.C.; Ojha, R.R.; Majhi, S.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. The interplay between cytokines, inflammation, and antioxidants: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potentials of various antioxidants and anti-cytokine compounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 78, 117177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman-Pepine, D.; Serban, A.M.; Capras, R.D.; Cismaru, C.M.; Fili, A.G.A. Comprehensive Review: Unraveling the Role of Inflammation in the Etiology of Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2025, 30, 931–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptaschinski, C.; Lukacs, W.N. Chapter 2—Acute and Chronic Inflammation Induces Disease Pathogenesis. In Molecular Pathology, 2nd ed.; Coleman, W., Tsongalis, G., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A.; Boehme, C.; Mayer-Suess, L.; Rudzki, D.; Knoflach, M.; Kiechl, S.; Reindl, M. Peripheral inflammatory response in people after acute ischaemic stroke and isolated spontaneous cervical artery dissection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolovska, I.; Kutsak, A.; Gordienko, L.; Bulanov, V.; Hrystyna, T.; Zarytska, V.; Plakhotnik, O.; Semeniv, I.; Kotuza, A.; Zazirnyi, I.; et al. Riskometric assessment of factors affecting population health in situational analysis features of cytochemical indicators of activity circulating and tissue leukocytes and oxidative stress as a factor of chronic inflammation. Fr.-Ukr. J. Chem. 2020, 8, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzlinger, C.; Rapp, S.; Hagmann, W.; Keppler, D. Leukotrienes as mediators in tissue trauma. Science 1985, 230, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, H.P.; Till, G.O.; Trentz, O.; Ward, P.A. Roles of histamine, complement and xanthine oxidase in thermal injury of skin. Am. J. Pathol. 1989, 135, 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- Panchal, N.K.; Sabina, E.P. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): A current insight into its molecular mechanism eliciting organ toxicities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 72, 113598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, C.D.R.; Arantes, M.B.; Menezes de Faria Pereira, S.; Leandro da Cruz, L.; de Souza Passos, M.; Pereira de Moraes, L.; Vieira, I.J.C.; Barros de Oliveira, D. Plants as Sources of Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Molecules 2020, 25, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Leon, A.; Moreno-Pérez, G.F.; Martínez-Gordillo, M.; Aguirre-Hernández, E.; Valle-Dorado, M.; Díaz-Reval, M.I.; González-Trujano, M.E.; Pellicer, F. Lamiaceae in mexican species, a great but scarcely explored source of secondary metabolites with potential pharmacological effects in pain relief. Molecules 2021, 26, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamoun, M.; Louhaichi, M. Roles of Lamiaceae plants from the arid and desert rangelands of Tunisia in human health and therapy. All Life 2024, 17, 2381675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, N.; Taviano, M.F.; Giuffrida, D.; Trovato, A.; Tzakou, O.; Galati, E.M. Anti-inflammatory activity of extract and fractions from Nepeta sibthorpii Bentham. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Javan, M.; Sonboli, A.; Semnanian, S. Evaluation of the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of essential oil of Nepeta pogonosperma Jamzad et Assadi in rats. Daru 2012, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Süntar, I.; Nabavi, S.M.; Barreca, D.; Fischer, N.; Efferth, T. Pharmacological and chemical features of Nepeta L. genus: Its importance as a therapeutic agent. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkov, A.; Angelova, P.; Marchev, A.; Hodzhev, Y.; Tsvetkov, V.; Dragolova, D.; Todorov, D.; Shishkova, K.; Kapchina-Toteva, V.; Blundell, R.; et al. Nepeta nuda ssp. nuda L. water extract: Inhibition of replication of some strains of Human Alpha herpes virus (genus Simplex virus) in vitro, mode of action and NMR-based metabolomics. J. Herb. Med. 2020, 21, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, D.; Gašić, U.; Yocheva, L.; Hinkov, A.; Yordanova, Z.; Chaneva, G.; Mantovska, D.; Paunov, M.; Ivanova, L.; Rogova, M.; et al. Catmint (Nepeta nuda L.) Phylogenetics and Metabolic Responses in Variable Growth Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 866777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, S.; Mazhdrakova, N.; Todinova, S.; Strijkova, V.; Zhiponova, M.; Krumova, S. Nepeta nuda L. Plant Extract Preserves the Morphology of Red Blood Cells Subjected to Oxidative Stress. Med. Sci. Forum 2023, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharieva, A.; Rusanov, K.; Rusanova, M.; Paunov, M.; Yordanova, Z.; Mantovska, D.; Tsacheva, I.; Petrova, D.; Mishev, K.; Dobrev, P.I.; et al. Uncovering the Interrelation between Metabolite Profiles and Bioactivity of in Vitro- and Wild-Grown Catmint (Nepeta nuda L.). Metabolites 2023, 13, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodinova, Z.; Antov, G.; Stoichev, S.; Zhiponova, M. In Vitro Anticancer Effects of Aqueous Leaf Extract from Nepeta nuda L. ssp. nuda. Life 2024, 14, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Sahana, G.R.; Nagella, P.; Joseph, B.V.; Alessa, F.M.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q. Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Molecules: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bansal, A.; Singh, V.; Chopra, T.; Poddar, J. Flavonoids, alkaloids and terpenoids: A new hope for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2022, 21, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boominathan, R.; Parimaladevi, B.; Mandal, S.; Ghoshal, S. Anti-inflammatory evaluation of Ionidium suffruticosam Ging. in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 91, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthong, A.; Norkaew, P.; Kanjanapothi, D.; Taesotikul, T.; Anantachoke, N.; Reutrakul, V. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activities of the extract of gamboge from Garcinia hanburyi Hook f. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 111, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsalem, M.; Haddad, M.; Altarifi, A.; Aldossary, S.A.; Kalbouneh, H.; Abojaradeh, A.M.; El-Salem, K. Impairment in locomotor activity as an objective measure of pain and analgesia in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draxler, P.; Moen, A.; Galek, K.; Boghos, A.; Ramazanova, D.; Sandkühler, J. Spontaneous, Voluntary, and Affective Behaviours in Rat Models of Pathological Pain. Front. Pain Res. 2021, 2, 672711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, C.A.; Risley, E.A.; Nuss, G.W. Carrageenin-induced edema in hind paw of the rat as an assay for antiiflammatory drugs. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1962, 111, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Javan, M.; Sonboli, A.; Semnanian, S. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oil of Nepeta crispa Willd. in experimental rat models. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 1529–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoh, A.; Danquah, C.A.; Benneh, C.K.; Andongo, D.W.; Boakye-Gyasi, E.; Woode, E. Effect of Diclofenac and Andrographolide Combination on Carrageenan-Induced Paw Edema and Hyperalgesia in Rats. Dose-Response Int. J. 2022, 20, 15593258221103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willoughby, D.A.; DiRosa, M. Studies on the mode of action of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1972, 31, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinegar, R.; Schreiber, W.; Hugo, R. Biphasic development of carrageenan edema in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1969, 166, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amdekar, S.; Roy, P.; Singh, V.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Sharma, P. Anti-inflammatory activity of lactobacillus on carrageenan-induced paw edema in male wistar rats. Int. J. Inflam. 2012, 2012, 752015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.J. Carrageenan-Induced Paw Edema in the Rat and Mouse. Methods Mol. Biol. 2003, 225, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhukya, B.; Anreddy, R.N.R.; William, C.M.; Gottumukkala, K.M. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of leaf extract of Kydia calycina Roxb. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2009, 4, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, F.; Warner, T.D. Origins of prostaglandin E2: Involvements of cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 in human and rat systems. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 2002, 303, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajčević, N.; Bukvički, D.; Dodoš, T.; Marin, P.D. Interactions between Natural Products—A Review. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necas, J.; Bartosikova, L. Carrageenan: A review. Vet. Med. 2013, 58, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, H.M.; Choirotussanijjah; Awwalia, E.S.; Alam, I.P. Anti-inflammatory effects and potential mechanisms of Mitragyna speciosa methanol extract on λ-karagenan-induced inflammation model. Bali Med. J. 2022, 11, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas-Barberan, F.A.; Gill, M.I.; Ivancheva, S.; Tomas-Lorente, F. External and vacuolar flavonoids from Nepeta transcaucasica. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1992, 20, 589–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, B.M.; Mestres, T.; Diaz, C.E.; Arteaga, J.M. Dehydroabietane diterpenes from Nepeta teydea. Phytochemistry 1994, 35, 1509–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Mathela, C.S.; Pant, A.K. Non volatile constituents of Nepeta leucophylla. Chem. Abstr. 1994, 121, 153399d. [Google Scholar]

- Yahfoufi, N.; Alsadi, N.; Jambi, M.; Matar, C. The Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Polyphenols. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, F.A.; Rao, V.S. Antiinflammatory and antonociceptive effects of 1,8-cineole a terpenoid oxide present in many plant essential oils. Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergens, U.R.; Engelen, T.; Racké, K.; Stöber, M.; Gillissen, A.; Vetter, H. Inhibitory activity of 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) on cytokine production in cultured human lymphocytes and monocytes. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 17, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.S.; Finnerup, N.B. Neuropathic pain: Peripheral and central mechanisms. Eur. J. Pain Suppl. 2009, 3, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.Z.; Mills, C.D.; Hsieh, G.C.; Zhong, C.; Mikusa, J.; Lewis, L.G.; Gauvin, D.; Lee, C.-H.; Decker, M.W.; Bannon, A.W.; et al. Assessing carrageenan-induced locomotor activity impairment in rats: Comparison with evoked endpoint of acute inflammatory pain. Eur. J. Pain 2012, 16, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, C.R.; Cisneros, I.E.; Covarrubias-Zambrano, O.; Stutz, S.J.; Motamedi, M.; Bossmann, S.H.; Cunningham, K.A. Liquid Biopsy-Based Biomarkers of Inflammatory Nociception Identified in Male Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 893828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos, E.J.; Portillo-Salido, E. “Bedside-to-Bench” Behavioral Outcomes in Animal Models of Pain: Beyond the Evaluation of Reflexes. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2013, 11, 560–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonussi, C.R.; Ferreira, S.H. Mechanism of diclofenac analgesia: Direct blockade of inflammatory sensitization. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 251, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.L.; González-Truzano, M.E.; Pellicer, F.; López-Muñoz, F.J.; Navarrete, A. Antinociceptive effect and GC/MS analysis of Roamarinus officinalis L. essential oil from its aerial parts. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, E.L.; Toyama, D.O.; Lago, J.H.G.; Romoff, P.; Kirsten, T.B.; Reis-Silva, T.M.; Bernardi, M.M. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory actions of Nepeta cataria L. var. citridora (Becker) Balb. essenmtial oil in mice. J. Health Sci. Inst. 2010, 28, 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, S.; Demir, T.; Oztürk, Y.; Baser, K.H. Analgesic activity of Nepeta italica L. Phytother. Res. 1999, 13, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liapi, C.; Anifandis, G.; Chinou, I.; Kourounakis, A.P.; Theodosopoulos, S.; Galanopoulou, P. Antinociceptive properties of 1,8-Cineole and betapinene, from the essential oil of Eucalyptus camaldulensis leaves, in rodents. Planta Med. 2007, 73, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extract Yield % | Phenols mg g DW−1 | Flavonoids mg g DW−1 | DPPH mM DW−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower | 16.6 b | 70.24 a | 40.26 c | 652.51 a |

| Leaf | 19.7 a | 63.67 b | 55.26 a | 391.82 c |

| Stem | 11.9 c | 60.06 c | 43.16 b | 437.41 b |

| Group | p-Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time After Injection, min | ||||

| 60 | 120 | 180 | 240 | |

| Control (0.9% NaCl i.pl.) | 0.1269 | 0.0504 | 0.2992 | 0.6337 |

| Carrageenan (1%, i.pl.) | 0.0007 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 |

| Placebo (0.9% NaCl i.p. + 1% Carrageenan i.pl.) | 0.00005 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keremidarska-Markova, M.; Evtimova-Koeva, V.; Penchev, T.; Doncheva-Stoimenova, D.; Zhiponova, M.; Chichova, M.; Ilieva, B. In Vivo Assessment of Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Aqueous Extracts of Nepeta nuda ssp. nuda L. in Experimental Model of Peripheral Inflammation in Male Long Evans Rats. Life 2025, 15, 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121938

Keremidarska-Markova M, Evtimova-Koeva V, Penchev T, Doncheva-Stoimenova D, Zhiponova M, Chichova M, Ilieva B. In Vivo Assessment of Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Aqueous Extracts of Nepeta nuda ssp. nuda L. in Experimental Model of Peripheral Inflammation in Male Long Evans Rats. Life. 2025; 15(12):1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121938

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeremidarska-Markova, Milena, Veneta Evtimova-Koeva, Tsvetozar Penchev, Dilyana Doncheva-Stoimenova, Miroslava Zhiponova, Mariela Chichova, and Bilyana Ilieva. 2025. "In Vivo Assessment of Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Aqueous Extracts of Nepeta nuda ssp. nuda L. in Experimental Model of Peripheral Inflammation in Male Long Evans Rats" Life 15, no. 12: 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121938

APA StyleKeremidarska-Markova, M., Evtimova-Koeva, V., Penchev, T., Doncheva-Stoimenova, D., Zhiponova, M., Chichova, M., & Ilieva, B. (2025). In Vivo Assessment of Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Aqueous Extracts of Nepeta nuda ssp. nuda L. in Experimental Model of Peripheral Inflammation in Male Long Evans Rats. Life, 15(12), 1938. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121938