The Mechanism of Emodin Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection and Research on Synergistic Antibiotics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Strains

2.1.1. Rheum officinale Baill (Part(s) Used: Root and Rhizome.)

2.1.2. Bacterial Strain

2.1.3. Antibiotics

2.1.4. The Main Detection Kits Used in the Experiment

2.2. Anti-MRSA Activity of Four Major Anthraquinones from the R. officinale

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.4. Bacterial Growth Curve Analysis

2.5. Crystal Violet Staining Assay for MRSA Biofilm Formation Inhibition

2.6. Determination of DNA and RNA in the Supernatant

2.7. SEM Characterization of Emodin’s Effect on MRSA Cell Morphology

2.8. Proteomics Experiment

2.9. Verification of Action Pathway

2.10. Evaluation of the Synergistic Antibacterial Effects of Emodin with Antibiotics

2.10.1. Evaluation of Emodin-Mediated Enhancement of Cephalexin and Amoxicillin Against MRSA

2.10.2. Inhibition of MRSA Adhesion to HaCaT Cells by Emodin and Cephalexin

- (1)

- Drug Preparation and Bacterial Treatment

- (2)

- Bacterial Staining with CFDA-SE

- (3)

- HaCaT Cell Culture and MRSA Adhesion Assay

2.10.3. Effect of the Emodin-Cephalexin Combination on MRSA-Infected HaCaT Cells

- (1)

- Bacterial Staining

- (2)

- Cell Preparation and Infection Assay

- (3)

- Flow Cytometry Analysis

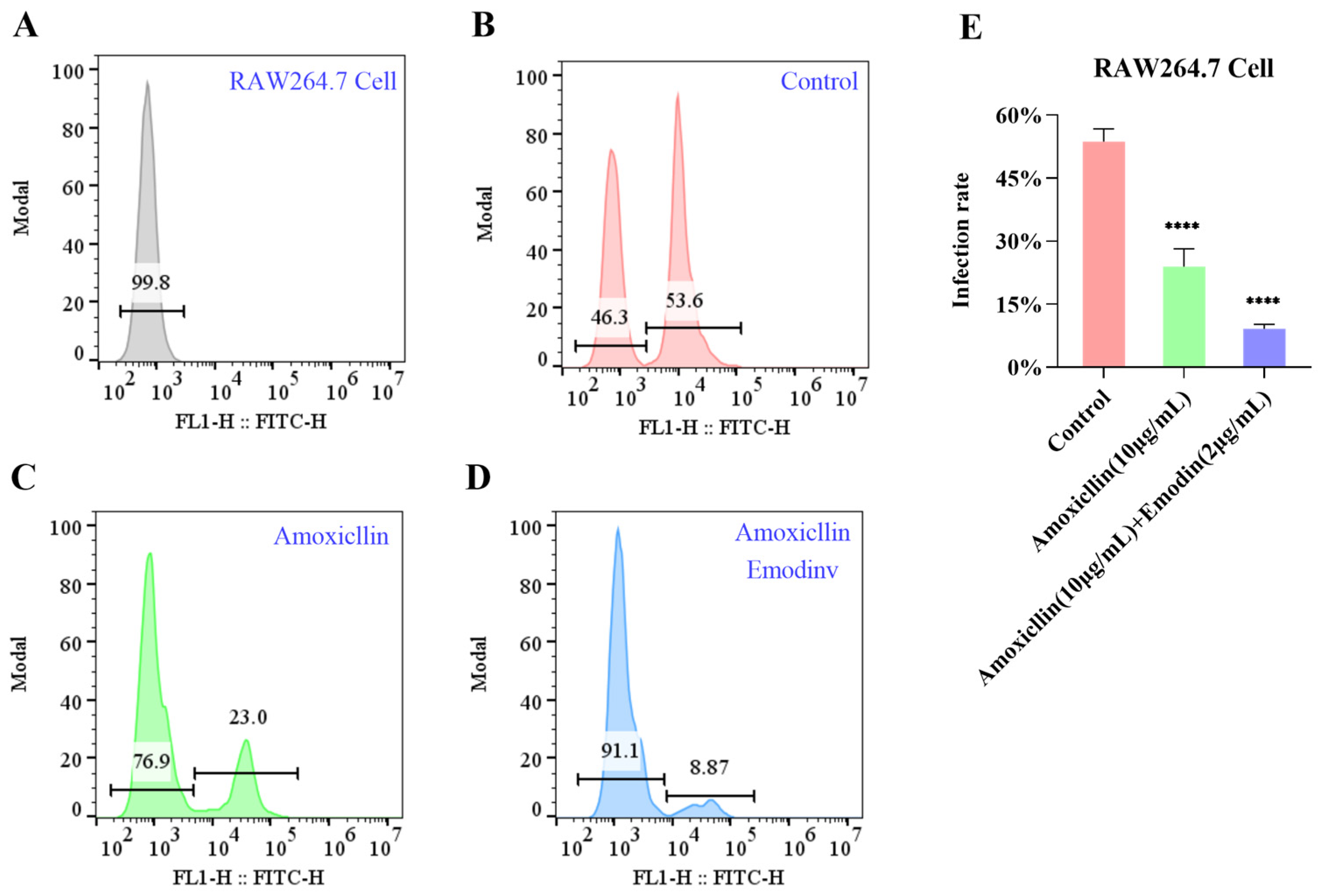

2.10.4. Evaluation of the Effects of Emodin-Amoxicillin Combination on MRSA-Infected RAW264.7 Cells

- (1)

- Drug Treatment and Fluorescent Labeling of MRSA

- (2)

- Infection of RAW264.7 Cells and Flow Cytometric Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screening of Active Components

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

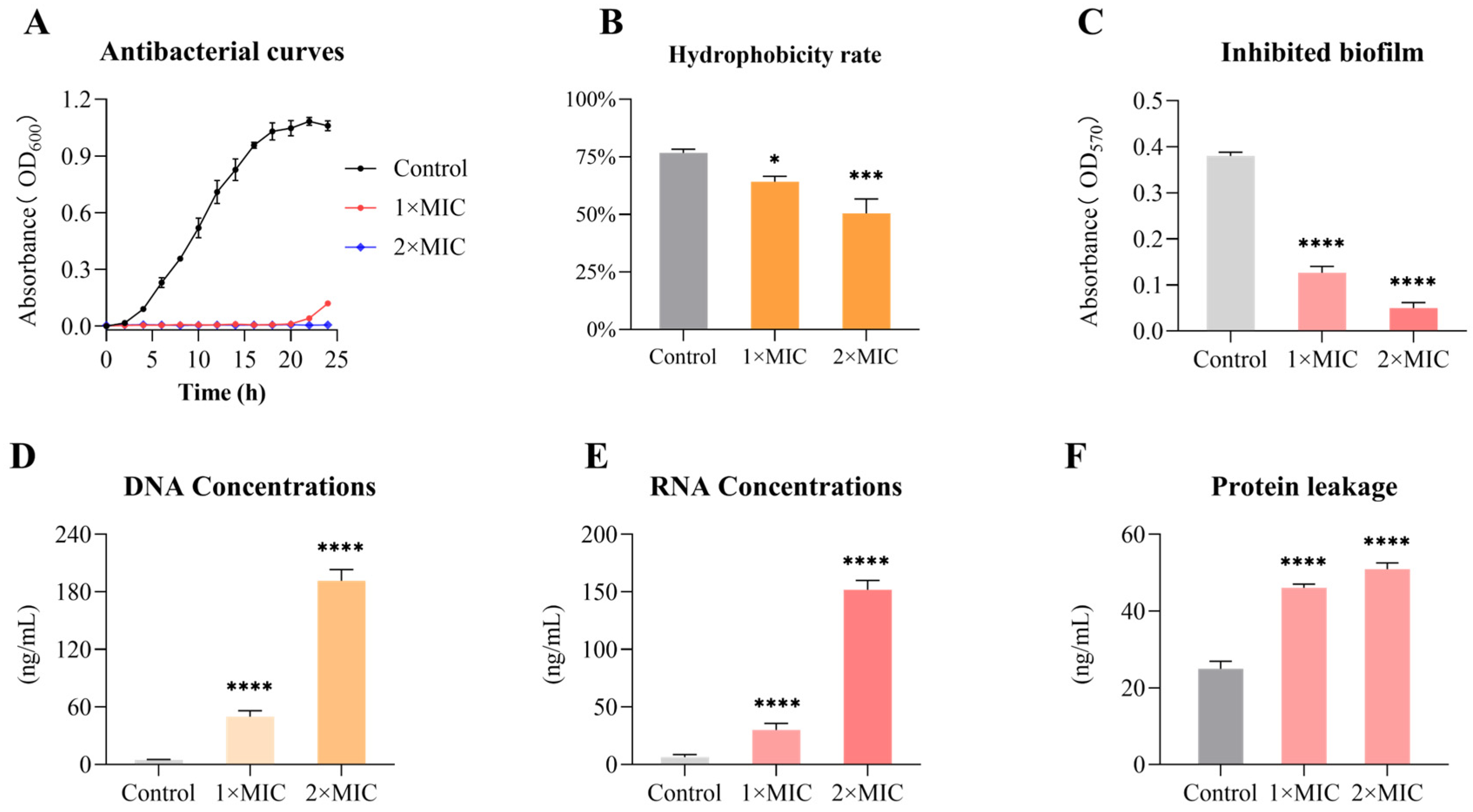

3.3. Emodin Inhibits the Growth of MRSA

3.4. Emodin Decreases the Cell Surface Hydrophobicity of MRSA

3.5. Inhibitory Effect of Emodin on MRSA Biofilm Formation

3.6. Emodin Induces Nucleic Acid Leakage in MRSA

3.7. Emodin Alters the Morphology of MRSA

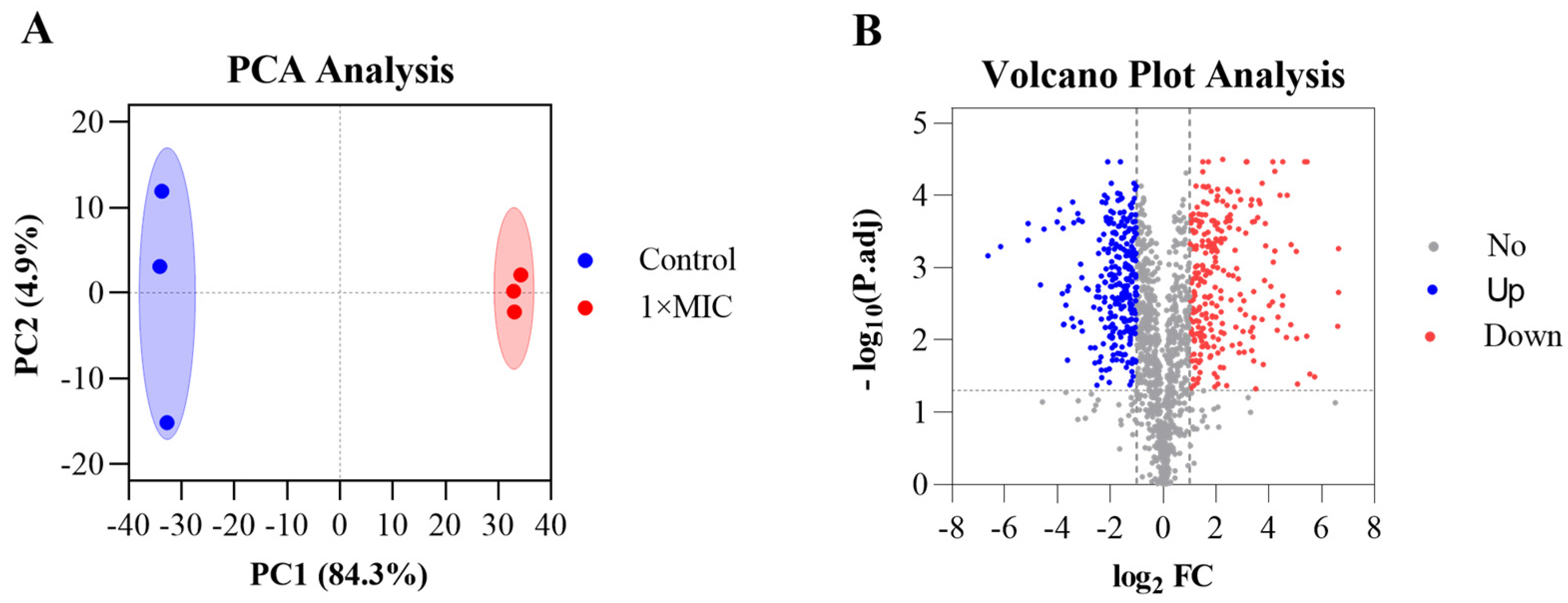

3.8. Emodin Exerts Antibacterial Effects Through Systemic Proteomic Alterations in MRSA

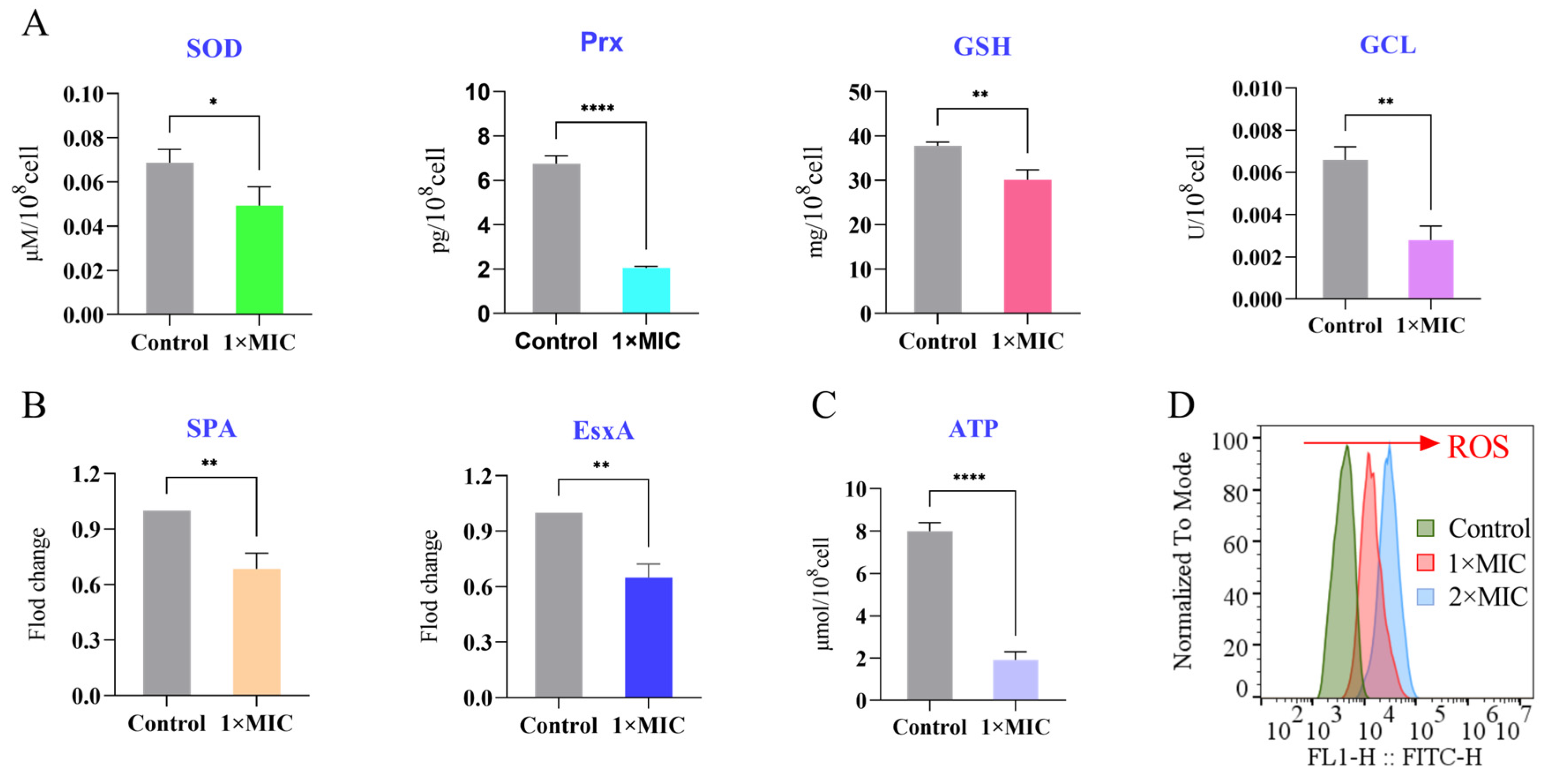

3.9. Emodin Perturbs Key Physiological Processes in MRSA

3.9.1. Suppression of Antioxidant and Virulence Proteins

3.9.2. Depletion of Intracellular ATP

3.9.3. Induction of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

3.10. Emodin Synergizes with β-Lactam Antibiotics Against MRSA

3.11. Synergistic Antibacterial Composition Inhibits the Adhesion of MRSA to HaCaT Cells

3.12. The Cephalexin and Emodin Combination Synergistically Inhibits MRSA Invasion of HaCaT Cells

3.13. Emodin Enhances the Efficacy of Amoxicillin Against MRSA Infection in RAW 264.7 Cells

4. Discussion

4.1. Emodin as a Multi-Target Anti-MRSA Agent

- (1)

- Deepening and Integrating Known Mechanisms

- (2)

- Deepening Congruence in Bacterial Membrane Damage

- (3)

- Systematic Expansion of Metabolic and Oxidative Stress Mechanisms

- (4)

- Explicit Revelation of Anti-Virulence Activity

4.2. Synergy with β-Lactam Antibiotics: Advancing from Mechanistic Validation to Functional Translational Insights

4.3. Considerations for Emodin’s Photosensitizer Properties

4.4. Implications and Future Perspectives: Mechanism-Driven Research Priorities

- (1)

- In vivo efficacy and safety validation in MRSA infection animal models to confirm in vitro findings and establish therapeutic windows [39];

- (2)

- High-resolution target deconvolution using advanced techniques to identify direct molecular targets of emodin and refine its multi-target pharmacology [40];

- (3)

- Formulation optimization to overcome emodin’s poor aqueous solubility and bioavailability, via nanocarrier or prodrug strategies, to enable clinical development [41].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MHB | Mueller Hinton Broth |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| CFU | colony forming units |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| MBC | minimal bactericidal concentration |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| SDH | succinate dehydrogenase |

| NADH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| OD | optical density |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| FC | fold change |

| p.adj | p-value adjusted |

| SpA | Staphylococcal protein A |

| FICI | fractional inhibitory concentration index |

| DEPs | Differentially Expressed Proteins |

| EsxA | ESAT-6-like protein |

| CFDA-SE | Carboxy fluorescein Diacetate Succinimidyl Ester |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| MOI | multiplicity of infection |

| CAMHB | Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| Prx | Peroxiredoxin |

| GCL | Glutamate-Cysteine Ligase |

References

- Sun, Z.W.; Zhang, J.F.; Wang, C.N.; Chen, J.H.; Li, P.; Su, J.C.; Xu, X.G.; Wang, M.G. The pivotal role of IncFIB(Mar) plasmid in the emergence and spread of hype rvirulent carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eado9097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.L.; Wen, J.Y.; Lu, J.H.; Zhou, H.B.; Wang, G.Z. Kaempferol and Kaempferin Alleviate MRSA Virulence by Suppressing β-Lactamase and Inflammation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Hu, F.P.; Zhu, D.M.; Wang, F.; Jiang, X.F.; Xu, C.Y.; Zhang, X.J. 2023 CHINET Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Program. Chin. J. Infect. Chemother. 2024, 24, 627–637. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.B.; Cui, S.B.; Sha, L. Research on resistance genes of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and disinfectant resistance related genes. J. Pathog. Biol. 2024, 19, 1437–1441. [Google Scholar]

- Klevens, R.M.; Morrison, M.A.; Nadle, J. Invasive Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 2007, 298, 1763–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, T.; Qian, M.; Ismail, B.B.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, Q.; Guo, M. Integrated Phenotypic and Transcriptomic Analyses Unveil the Antibacterial Mechanism of Punicalagin Against Methicillin-Resist-ant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Foods 2025, 14, 3589. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, A.; Herman, A.P. Herbal Products and Their Active Constituents Used Alone and in Combination with Antibiotics against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Planta Med. 2023, 89, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.F.; Gu, X.M.; Wang, W.; Lin, M.; Wang, L. Advancements in MRSA treatment: The role of berberine in enhancing antibiotic therapy. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.N.; Wang, W.; Li, X.Z.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, C.; Song, X.M.; Zhang, D.D. Botany, Traditional Use, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Clinical Applications of Rhubarb (Rhei Radix et Rhizome): A Syste-matic Review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2024, 52, 1925–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liang, C.S.; Wang, T.; Shen, J.L.; Ling, F.; Jiang, H.F.; Li, P.F. Antiviral, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of rhein against white spot syndrome virus infection in red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii). Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.Y.; Li, S.J.; Wang, Y.Q. Integrated Serum Pharmacochemistry, Network Pharmacology, and Molecular Docking to Study the Mechanism of Rhubarb against Atherosclerosis. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2025, 26, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zu, J.Z.; Lu, S.; Peng, J.; Ren, Y.Y.; Tan, R. Antibacterial mechanism of rhein against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. China 2021, 48, 2111−2117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.H.; Yi, Y. Study on the in vitro antibacterial activity of emodin against Escherichia coli and its antibacterial mechanism. Heilongjiang Anim. Sci. Vet. Med. 2021, 10, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Urgesa, G.; Lu, L.S.; Gao, J.W.; Guo, L.C.; Qin, T.; Liu, B.; Xie, J.; Xi, B.W. Natural Sunlight-Media-ted Emodin Photoinactivation of Aeromonas hydrophila. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, B.; Xia, D.W.; Ma, S.X. In vitro bacteriostasis of emodin on Candida albicans. Chin. J. Microecol. 2016, 28, 681–684. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.P. Preliminary Studies on the Chemical Constituents and Antioxidant Activity in vitro of the Aerial Parts of Rheum Officinale Baill; Gansu University of Chinese Medicine: Lanzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, X.F.; Zhao, Z.M.; Li, J.C.; Yang, G.Z.; Liu, Y.Q.; Dai, L.X.; Zhang, Z.J.; Yang, Z.G.; Miao, X.L.; Yang, C.J.; et al. Insecticidal and antifungal activities of Rheum officinale Baill. anthraquinones and structurally related compounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 137, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.G.; Zhu, L.P.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, D.P.; Xu, X.J.; Ding, P.; Li, R.N.; Zhao, Z.M. Metabolo-mics-Driven Exploration of the Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of 2-Methoxycinnamaldehyde. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 864246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, S.; Bala, Y.; Armstrong, T.; García-Castillo, M.; Burnham, C.D.; Wallace, M.A.; Hardye, D.; Zambardi, G.; Cantón, R. Multicenter Evaluation of the New Etest Gradient Diffusion Method for Piperacillin-Tazobactam Susceptibility Testing of Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii Complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01042-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadari, C.D.; Vila, T.; Rozental, S.; Ishida, K. Miltefosine has a Postantifungal effect and induces apoptosis in Cryptococcus yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e312–e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Wu, Z.Q.; Chen, Q.Y.; Yan, D.N.; Ling, Y.Q.; He, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhao, G.M.; Peng, H.Y.; Yang, D.P. Molecular mechanism underlying Oleum Cinnamomi-induced ferroptosis in MRSE via covalent modification of AhpC. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1554294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.L.; Chen, J.L.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, P.; He, G.Z.; Zhang, L.X.; Zhao, Z.M.; Yang, D.P. Exploring antimicrobial mechanism of essential oil of Amomum villosum Lour through metabolomics based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 242, 126608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.Y.; Chen, F.H.; Yang, W.; Yan, T.; Chen, Q. Antibiofilm efficacy of emodin alone or combined with ampicillin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M. Investigation on its Anti-MRSA Effects of Emodin in vitro and in vivo, and Its Mechanisms; Former Third Military Medical University: Chongqing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kashi, M.; Varseh, M.; Askarinia, M.; Ghasemikhah, R.; Chegini, Z.; Shariati, A. The interactions of natural compounds with Escherichia coli motility, attachment, communication systems, and mature biofilm. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.M., Jr.; de Souza, R.C.M.C.; Palma, M.S.; Hancock, R.E.W. Antimicrobial peptides: Structural diversity, mechanisms of action, and clinical potential for combating antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 789–808. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.P.; Huang, S.Q.; Han, Y.Z. Antibacterial effect of emodin on multi-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and its mechanism. Med. J. Chin. People’s Armed Police Forces 2025, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Ross, C.B.; Jin, Y.J.; Wang, W.J.; Li, H.R.; Hou, X.L. Antibacterial Activity and Membrane-Targeting Mechanism of Aloe-Emo din Against Staphylococcus epidermidis. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 621866. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, D.; John, A.C.; Newman, D.K. Bioenergetic suppression by redox-active metabolites promotes antibiotic tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2406555121. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Gomez, H.; Murugan, R.; Hong, X.; Xu, D.X.; Jiang, F.; Peng, Z.Y. Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Ferroptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 5080843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Cai, L.; Duan, H.; Liu, C.; Li, H.B.; Liu, M. Inhibitory effect of emodin on MRSA biofilm and its mechanism. J. Army Med. Univ. 2022, 44, 684–690. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.L.; Chen, J.L.; Zhang, L.X.; Zhang, R.F.; Zhang, S.C.; Ye, S.X. Exploring the antibacterial mechanism of essential oils by membrane permeability, apoptosis and biofilm formation combination with proteomics analysis against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 310, 151435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, H.F.; Sachdeva, M.; Kennedy, S. Binding Affinity for Penicillin-Binding Protein 2a Correlates with In Activity of β-Lactan Antibiotics against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 1990, 162, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoneim, M.M.; Al-Serwi, R.H.; El-Sherbiny, M.; El-ghaly, E.M.; Hamad, A.E.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; Ragab, E.A.; Bukhari, S.I.; Bukhari, K.; Elokely, K.; et al. Nael.Proposed Mechanism for Emodin as Agent for Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus: In Vitro Testing and In Silico Study. Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 4490–4499. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.J.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Kim, S.C.; Ree, J.; Choi, T.G.; Sohng, J.K.; Yong, I.P. Emodin 8-O-glucoside primes macrophages more strongly than emodin aglycone via activation of phagocytic activity and TLR-2/MAPK/NF-κB signalling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 88, 106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic inactivation of MRSA by emodin-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles: Role of ROS and bacterial membrane damage. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2025, 114892, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Aloe emodin-MnxOy antibacterial nanozyme-functionalized hydrogel for wound infection therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2024, 235, 113645. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.L. Aloe Emodin-Mediated Photodynamic Inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus: Enhanced Efficacy via Co-Amorphous Technology; Guangdong University of Technology: Guangzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, P.W.; Wei, S.Y.; Luo, C.H.; Wang, Q.R. Emodin-loaded electrospun nanofibers for MRSA wound infection. Biomater. Res. 2025, 29, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Klykov, O.; Kopylov, M.; Carragher, B.; Heck, A.J.R.; Noble, A.J.; Scheltema, R.A. Label-free visual proteomics: Coupling MS-and EM-based approaches in structural biology. Mol. Cell 2025, 95, 3279–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.T.; Wang, W.; Li, X.M.; Wang, L.N.; Zhang, H.M. Emodin solid dispersions with PVP–poloxamer for dissolution enhancement. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1234. [Google Scholar]

| Samples | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Emodin | 12.0 |

| Rhein | 16.0 |

| Aloe-emodin | >100.0 |

| Chrysophanol | >100.0 |

| Berberine | >100.0 |

| Flavonols | >200 μg/mL |

| Baicalin | >200 μg/mL |

| Antibiotics | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | 30.0 |

| Cephalexin | 65.0 |

| Gentamicin Sulfate | >200.0 |

| Clarithromycin | >200.0 |

| Clindamycin Hydrochloride | >200.0 |

| Tetracycline | 200.0 |

| Vancomycin Hydrochloride | 3.0 |

| Antibiotics | MIC (μg/mL) | FICI |

|---|---|---|

| Emodin | 12.0 | -- |

| Cephalexin | 65 | -- |

| Amoxicillin | 30 | -- |

| Emodin + Cephalexin | 2.0 + 20 | 0.475 |

| Emodin + Amoxicillin | 2.0 + 10 | 0.5 |

| Emodin + Clindamycin | 6.0 + 80 | 0.9 |

| Emodin + Gentamicin | 8.0 + 100 | 1.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, C.; Qin, L.; Peng, H.; Kuang, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, F.; Gao, P.; Wang, X.; Ma, D. The Mechanism of Emodin Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection and Research on Synergistic Antibiotics. Life 2025, 15, 1920. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121920

Chu C, Qin L, Peng H, Kuang T, Li Y, Wang X, Liang F, Gao P, Wang X, Ma D. The Mechanism of Emodin Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection and Research on Synergistic Antibiotics. Life. 2025; 15(12):1920. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121920

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Chenliang, Liang Qin, Huayong Peng, Tao Kuang, Yongshi Li, Xin Wang, Fenglan Liang, Ping Gao, Xiaoxiong Wang, and Deyun Ma. 2025. "The Mechanism of Emodin Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection and Research on Synergistic Antibiotics" Life 15, no. 12: 1920. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121920

APA StyleChu, C., Qin, L., Peng, H., Kuang, T., Li, Y., Wang, X., Liang, F., Gao, P., Wang, X., & Ma, D. (2025). The Mechanism of Emodin Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection and Research on Synergistic Antibiotics. Life, 15(12), 1920. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121920