Impact of Preservative-Free Travoprost on Intraocular Pressure and Ocular Surface in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Treatment Protocol

2.4. Assessment and Follow-Up

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

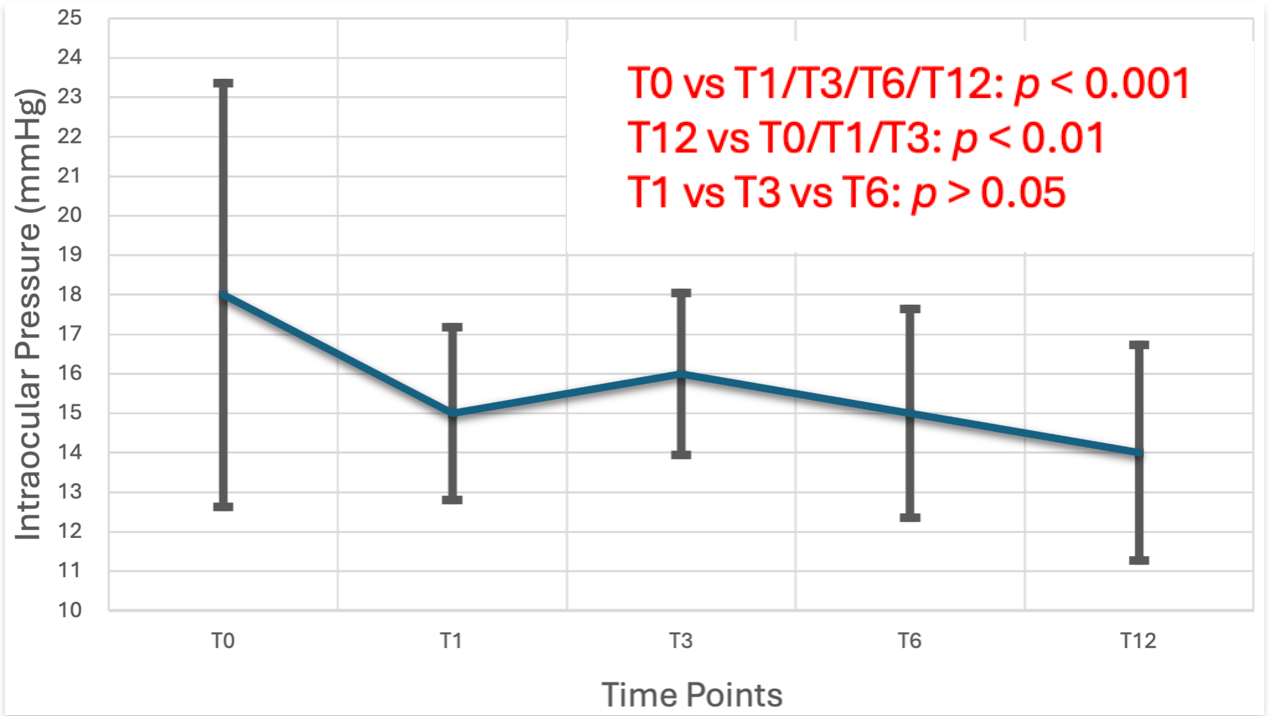

3.2. Intraocular Pressure (IOP)

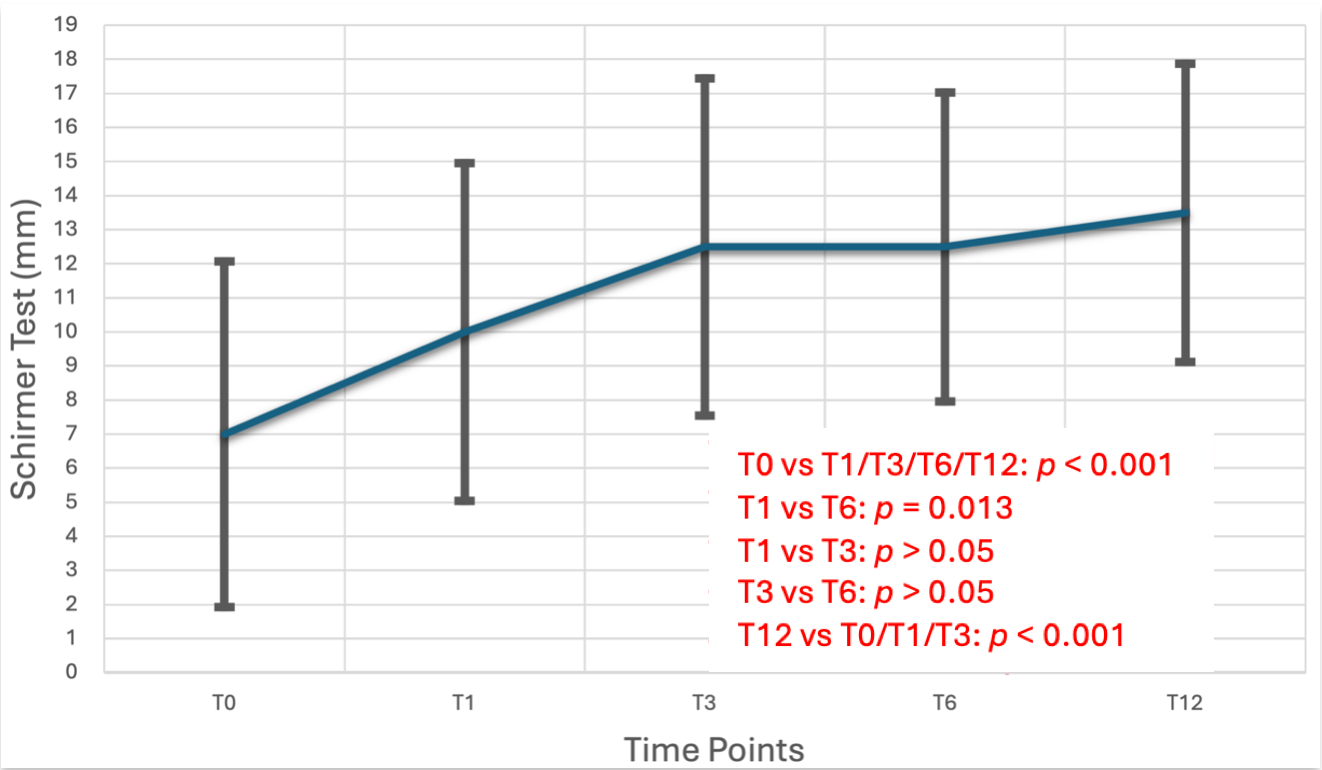

3.3. Ocular Surface Parameters

3.4. Glaucoma Indices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IOP | Intraocular Pressure |

| POAG | Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma |

| OHT | Ocular Hypertension |

| BAK | Benzalkonium Chloride |

| OSD | Ocular Surface Disease |

| TBUT | Tear Break-Up Time |

| CCT | Central Corneal Thickness |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| RNFL | Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer |

| GCC | Ganglion Cell Complex |

| VFI | Visual Field Index |

| MD | Mean Deviation |

| PSD | Pattern Standard Deviation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CH | conjunctival hyperemia |

| SITA | Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- European Glaucoma Society. Terminology and Guidelines for Glaucoma, 5th ed. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105 (Suppl. S1), 1–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, H.A.; Broman, A.T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.M.; Tanna, A.P. Glaucoma. Med. Clin. 2021, 105, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prum, B.E., Jr.; Rosenberg, L.F.; Gedde, S.J.; Mansberger, S.L.; Stein, J.D.; Moroi, S.E.; Herndon, L.W.; Lim, M.C.; Williams, R.D. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, P41–P111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedde, S.J.; Vinod, K.; Wright, M.M.; Muir, K.W.; Lind, J.T.; Chen, P.P. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, P71–P150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedde, S.J.; Lind, J.T.; Wright, M.M.; Chen, P.P.; Muir, K.W.; Vinod, K.; Li, T.; Mansberger, S.L. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Suspect Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, P151–P192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshegov, S.; Kerr, N.M. Prostaglandin FP receptor agonists in the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension: A literature review. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2023, 32, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz-Marquez, E.; Teus, M.Á. Prostaglandin analogues for the treatment of glaucoma: From the ‘wonder’ drug of the ‘90s to the reality of the 21st century. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2022, 97, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsou, A.; Anastasopoulos, E. Investigational drugs targeting prostaglandin receptors for the treatment of glaucoma. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2018, 27, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, N.; Chakrabarti, A.; Nazm, N.; Mehta, R.; Edward, D.P. Newer advances in medical management of glaucoma. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 1920–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Qin, L. Efficacy of travoprost for the treatment of patients with glaucoma. Medicine 2019, 98, e16526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lindsley, K.; Rouse, B.; Hong, H.; Shi, Q.; Friedman, D.S.; Wormald, R.; Dickersin, K. Comparative effectiveness of first-line medications for primary open-angle glaucoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peace, J.H.; Ahlberg, P.; Wagner, M.; Lim, J.M.; Wirta, D.; Branch, J.D. Polyquaternium-1-preserved travoprost 0.003% or benzalkonium chloride-preserved travoprost 0.004% for glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 160, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, M.H.; Silva, F.Q.; Blender, N.; Tran, T.; Vantipalli, S. Ocular benzalkonium chloride exposure: Problems and solutions. Eye 2022, 36, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahook, M.Y.; Rapuano, C.J.; Messmer, E.M.; Radcliffe, N.M.; Galor, A.; Baudouin, C. Preservatives and ocular surface disease: A review. Ocul. Surf. 2024, 34, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaštelan, S.; Tomić, M.; Soldo, K.M.; Salopek-Rabatić, J. How ocular surface disease impacts the glaucoma treatment outcome. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 696328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, D.W.; Alaghband, P.; Lim, K.S. Preservatives in glaucoma medication. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemer, Ö.E.; Mekala, P.; Dave, B.; Kooner, K.S. Managing ocular surface disease in glaucoma treatment: A systematic review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstas, A.G.; Labbé, A.; Katsanos, A.; Meier-Gibbons, F.; Irkec, M.; Boboridis, K.G.; Holló, G.; García-Feijoo, J.; Dutton, G.N.; Baudouin, C. The treatment of glaucoma using topical preservative-free agents: An evaluation of safety and tolerability. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 20, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedlová, K.; Saija, M.C.; Olżyńska, A.; Jurkiewicz, P.; Daull, P.; Garrigue, J.S.; Cwiklik, L. Influence of BAKs on tear film lipid layer: In vitro and in silico models. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 186, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudouin, C.; Labbé, A.; Liang, H.; Pauly, A.; Brignole-Baudouin, F. Preservatives in eyedrops: The good, the bad and the ugly. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2010, 29, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanford, M. Preservative-free latanoprost eye drops in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma/ocular hypertension. Clin. Drug Investig. 2014, 34, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harasymowycz, P.; Hutnik, C.; Rouland, J.-F.; Negrete, F.J.M.; Economou, M.A.; Denis, P.; Baudouin, C. Preserved versus preservative-free latanoprost for the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension: A post hoc pooled analysis. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 3019–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.E.; Lee, C.K.; Shin, J.; Kim, Y.; Rho, S. Comparisons of efficacy and safety between preserved and preservative-free brimonidine tartrate in glaucoma and ocular hypertension: A parallel-grouped, randomized trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.C.; Peace, J.H.; Stewart, J.A.; Stewart, W.C. Efficacy, safety, and improved tolerability of travoprost BAK-free ophthalmic solution compared with prior prostaglandin therapy. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2008, 2, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Feijoo, J.; Muñoz-Negrete, F.J.; Hubatsch, D.A.; Rossi, G.C. Efficacy and tolerability of benzalkonium chloride-free travoprost in glaucoma patients switched from benzalkonium chloride-preserved latanoprost or bimatoprost. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 2085–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, M.; Otani, S.; Kozaki, J.; Unoki, K.; Takeuchi, M.; Minami, K.; Miyata, K. Long-term effect of BAK-free travoprost on ocular surface and intraocular pressure in glaucoma patients after transition from latanoprost. J. Glaucoma 2012, 21, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, N.; Morgan, P.B.; Katsara, S.S. Validation of grading scales for contact lens complications. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2001, 21, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, N.; Supramaniam, G.; Samsudin, A.; Juana, A.; Zahari, M.; Choo, M.M. Ocular surface disease in glaucoma: Effect of polypharmacy and preservatives. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2015, 92, e222–e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canut, M.I.; García-Feijoo, J.; Larrosa-Poves, J.M.; López-López, F.; Pazos, M.; Espinoza-Cámac, N.; Oyagüez, I.; Del Rio, T.; Rodríguez, M. Cost-utility analysis of latanoprost unidose cationic emulsion preservative-free versus latanoprost unidose in the treatment of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension patients in Spain. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2025, 25, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisella, P.J.; Pouliquen, P.; Baudouin, C. Prevalence of ocular symptoms and signs with preserved and preservative free glaucoma medication. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddone, F.; Kirwan, J.; Lopez-Lopez, F.; Zimina, M.; Fassari, C.; Holló, G. Switching to preservative-free tafluprost/timolol fixed-dose combination in the treatment of open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension: Subanalysis of data from the VISIONARY Study according to baseline monotherapy treatment. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 3501–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandroković, S.; Pauk, S.V.; Gaćina, D.L.; Skegro, I.; Tomić, M.; Masnec, S.; Kuzman, T.; Kalauz, M. Tolerability in glaucoma patients switched from preserved to preservative-free prostaglandin-timolol combination: A prospective real-life study. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 3181–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shedden, A.; Adamsons, I.A.; Getson, A.J.; Laurence, J.K.; Lines, C.R.; Hewitt, D.J.; Ho, T.W. Comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of preservative-free and preservative-containing formulations of the dorzolamide/timolol fixed combination (COSOPT™) in patients with elevated intraocular pressure in a randomized clinical trial. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2010, 248, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.G.; Walters, T.R.; Schwartz, G.F.; Mundorf, T.K.; Liu, C.; Schiffman, R.M.; Bejanian, M. Bimatoprost 0.03% preservative-free ophthalmic solution versus bimatoprost 0.03% ophthalmic solution (Lumigan) for glaucoma or ocular hypertension: A 12-week, randomised, double-masked trial. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 97, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, I.; Gil Pina, R.; Lanzagorta-Aresti, A.; Schiffman, R.M.; Liu, C.; Bejanian, M. Bimatoprost 0.03%/timolol 0.5% preservative-free ophthalmic solution versus bimatoprost 0.03%/timolol 0.5% ophthalmic solution (Ganfort) for glaucoma or ocular hypertension: A 12-week randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 98, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, T.; Ichhpujani, P.; Vohra, S.; Thakur, S. Correlation of ocular surface disease and quality of life in Indian glaucoma patients: BAC-preserved versus BAC-free travoprost. Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 50, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruangvaravate, N.; Choojun, K.; Srikulsasitorn, B.; Chokboonpiem, J.; Asanatong, D.; Trakanwitthayarak, S. Ocular surface changes after switching from other prostaglandins to tafluprost and preservative-free tafluprost in glaucoma patients. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 3109–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muz, O.E.; Dagdelen, K.; Pirdal, T.; Guler, M. Comparison of BAK-preserved latanoprost and polyquad-preserved travoprost on ocular surface parameters in patients with glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Int. Ophthalmol. 2021, 41, 3825–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudouin, C.; Stalmans, I.; Bourne, R.; Larrosa, J.M.; Schmickler, S.; Seleznev, A.; Oddone, F.; Phase III study group. A phase III study comparing preservative-free latanoprost eye drop emulsion with preserved latanoprost in open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Eye 2025, 39, 1599–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czumbel, N.; Acs, T.; Bator, G.; Halmosi, A.; Egorov, E.A.; Maltsev, D.S. A phase III, multicentre, randomised, investigator-masked, cross-over, comparative, non-inferiority trial evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of generic preservative-free Latanoprost (Polpharma, S.A.) compared to Xalatan® (Pfizer) in patients with ocular hypertension or primary open-angle glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, D.; McSwiney, T.; James, M. Comparing the tolerability of preservative-free tafluprost versus preserved latanoprost in the management of glaucoma and ocular hypertension—An observer blinded active-control trial. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 193, 2589–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandarakis, S.; Papadopoulos, A.P.; Roussopoulos, G.; Georgopoulos, E.; Chung, Y.; Doumazos, L.; Baek, A.; Paizi, N.I.; Shin, H.; Papadopoulos, P.A. COMfort Eye Trial (COMET) results—A non-inferiority, randomized, investigator-masked, two-parallel group, phase III clinical trial, to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a preservative free formulation of latanoprost versus a reference drug (Xalatan®) in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) or ocular hypertension (OHT). Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2024, 23, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Age (years, Median [IQR]) | 75 [73, 82] |

| Gender (n) | 22 male, 17 female |

| Duration of disease (years, Median [IQR]) | 6.5 [1, 15] |

| Previous medication (n) | 15 latanoprost, 13 tafluprost |

| Follow-Up | Number of Patients | Median (mmHg) [IQR] | p < 0.05 (Mean Difference) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOP Τ0 | 39 | 18 [15, 20] | IOP Τ1 (3) | p < 0.001 |

| IOP Τ3 (2) | p < 0.001 | |||

| IOP T6 (3) | p < 0.001 | |||

| IOP Τ1 | 39 | 15 [14, 16] | IOP Τ0 | p < 0.001 |

| IOP Τ3 | 39 | 16 [14.75, 17] | IOP Τ0 | p < 0.001 |

| IOP Τ6 | 39 | 15 [13.5, 15] | IOP Τ0 | p < 0.001 |

| IOP T12 | 39 | 14 [12.8, 15] | IOP T0 (4) | p < 0.001 |

| IOP T1 (3) | p = 0.007 | |||

| IOP T3 (2) | p < 0.001 |

| Follow-Up | Number of Patients | Median [IQR] | Statistically Significant Difference Between the Time Points (p < 0.05) (Mean Difference) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schirmer test Τ0 (mm) | 39 | 7 [5, 12.25] | Schirmer Τ1 (3) | p < 0.001 |

| Schirmer Τ3 (5.5) | p < 0.001 | |||

| Schirmer Τ6 (5.5) | p = 0.013 | |||

| Schirmer test Τ1 (mm) | 39 | 10 [6, 15] | Schirmer T0(3) | p < 0.001 |

| Schirmer T6 (2.5) | p = 0.013 | |||

| Schirmer test Τ3 (mm) | 39 | 12.5 [10, 15.5] | Schirmer T0 (5.5) | p < 0.001 |

| Schirmer test Τ6 (mm) | 39 | 12.5 [10, 16.5] | Schirmer T0 (5.5) | p < 0.001 |

| Schirmer T1 (2.5) | p = 0.013 | |||

| Schirmer test Τ12 (mm) | 39 | 13.5 [11, 17.3] | Schirmer T0 (6.5) | p < 0.001 |

| Schirmer T1 (3.5) | p < 0.001 | |||

| Schirmer T3 (1) | p < 0.001 | |||

| TBUT T0 (s) | 39 | 14 [10, 19.5] | N/A | p > 0.05 |

| TBUT T1 (s) | 39 | 16 [11.5, 19] | N/A | p > 0.05 |

| TBUT T3 (s) | 39 | 16 [14.5, 20] | N/A | p > 0.05 |

| TBUT T6 (s) | 39 | 16,5 [14, 20] | N/A | p > 0.05 |

| TBUT T12 (s) | 39 | 17 [15, 21] | N/A | p > 0.05 |

| CH Τ0 | 39 | 2 [1, 2] | CH Τ1 | p = 0.005 |

| CH Τ3 | p = 0.027 | |||

| CH Τ6 | p < 0.001 | |||

| CH Τ1 | 39 | 1 [1, 2] | CH Τ0 | p = 0.005 |

| CH Τ6 | p = 0.038 | |||

| CH Τ3 | 39 | 1 [1, 2] | CH Τ0 | p = 0.027 |

| CH Τ6 | p = 0.007 | |||

| CH Τ6 | 39 | 1 [1, 2] | CH Τ0 | p < 0.001 |

| CH Τ1 | p = 0.038 | |||

| CH Τ3 | p = 0.007 | |||

| CH T12 | 39 | 1 [1, 2] | CH Τ0 | p < 0.001 |

| CH Τ1 | p = 0.003 | |||

| CH Τ3 | p < 0.001 |

| Glaucoma Indices | Number of Patients | T0 (Mean ± SD) | T6 (Mean ± SD) | T12 (Mean ± SD) | Mean Difference (from Baseline) ± SD [95% CI] | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VFI (%) | 39 | 84.55 ± 23.86 | 82.83 ± 24.26 | 82.4 ± 24.35 | −1.083 ± 0.84 [−0.62, 2.79] | p = 0.218 |

| MD (dB) | 39 | −6.54 ± 8.38 | −6.66 ± 8.40 | −6.69 ± 8.51 | 0.141 ± 0.018 [0.1, 0.177] | p = 0.15 |

| PSD (dB) | 39 | 3.88 ± 3.06 | 3.93 ± 3.33 | 3.95 ± 3.13 | 0.072 ± 0.095 [−0.245, 0.099] | p = 0.39 |

| RNFL (μm) | 39 | 87.17 ± 9.76 | 85 ± 8.38 | 84.4 ± 9.54 | −2.5 ± 1.99 [−1.25, −1.96] | p = 0.11 |

| GCC (μm) | 39 | 89.68 ± 11.3 | 88.4 ± 11.31 | 87.9 ± 11.2 | −1.8 ± 3.72 [−2.35, 0.15] | p = 0.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakirtzis, M.; Ntonti, P.; Panagiotopoulou, E.-K.; Konstantinidis, A.; Manolopoulos, V.G.; Kolios, G.; Labiris, G. Impact of Preservative-Free Travoprost on Intraocular Pressure and Ocular Surface in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Patients. Life 2025, 15, 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121870

Bakirtzis M, Ntonti P, Panagiotopoulou E-K, Konstantinidis A, Manolopoulos VG, Kolios G, Labiris G. Impact of Preservative-Free Travoprost on Intraocular Pressure and Ocular Surface in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Patients. Life. 2025; 15(12):1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121870

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakirtzis, Minas, Panagiota Ntonti, Eirini-Kanella Panagiotopoulou, Aristeidis Konstantinidis, Vangelis G. Manolopoulos, George Kolios, and Georgios Labiris. 2025. "Impact of Preservative-Free Travoprost on Intraocular Pressure and Ocular Surface in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Patients" Life 15, no. 12: 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121870

APA StyleBakirtzis, M., Ntonti, P., Panagiotopoulou, E.-K., Konstantinidis, A., Manolopoulos, V. G., Kolios, G., & Labiris, G. (2025). Impact of Preservative-Free Travoprost on Intraocular Pressure and Ocular Surface in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Patients. Life, 15(12), 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121870