Marinesco–Sjögren Syndrome: A Novel SIL1 Variant with In Silico Analysis and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Bioinformatic Modeling and Analysis of Wild Type and Mutant of SIL1

2.3. Genetic Analysis

3. Results

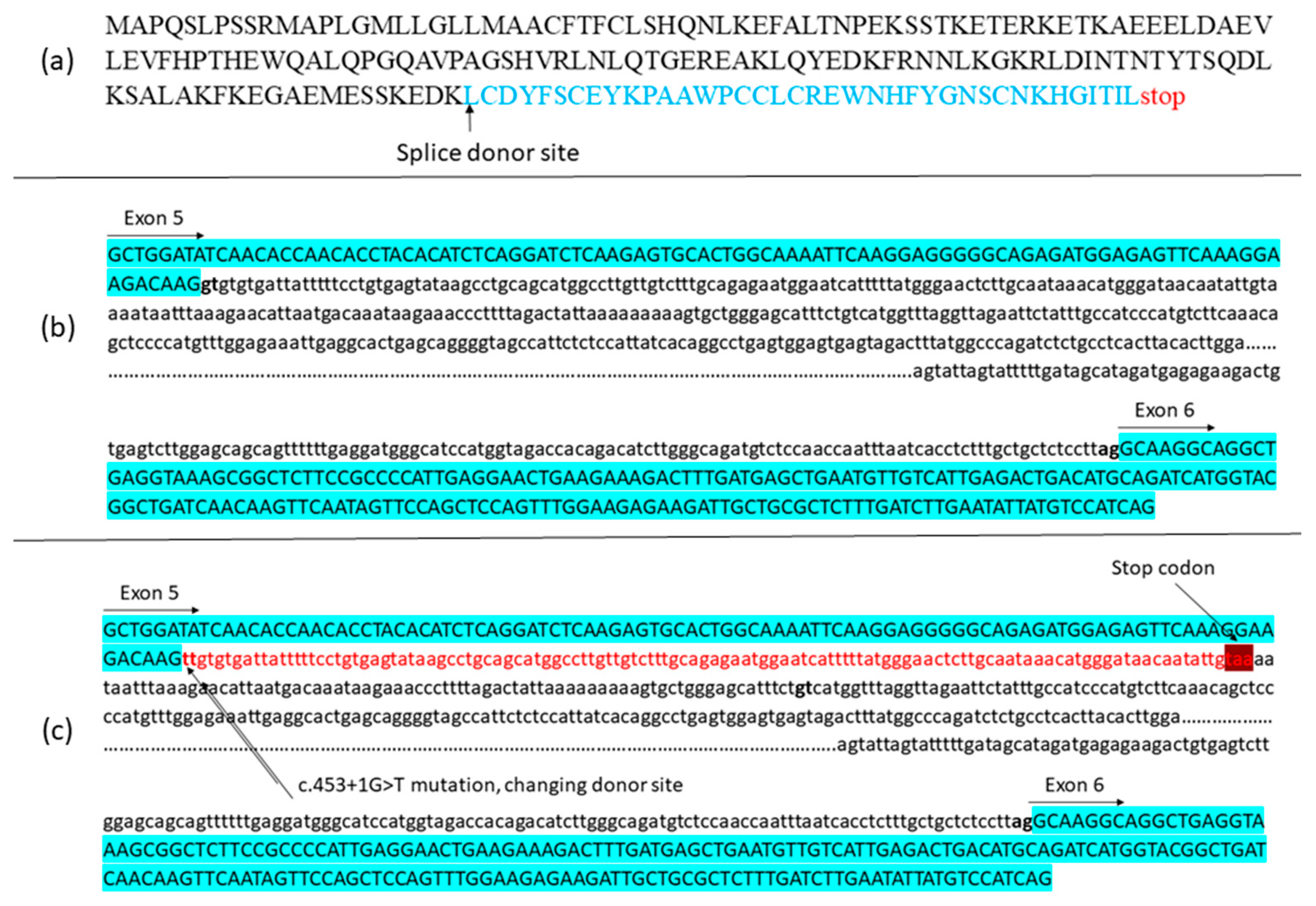

3.1. Patient Presentation and Genetic Study

3.2. Bioinformatic Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| AA | Amino Acid |

| ARM | Armadillo Repeat Motif |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BIP | Binding Immunoglobulin Protein |

| B@MER | Biruni Research Center |

| CADD | Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion |

| CHOP | C/EBP Homologous Protein |

| C-SCORE | Confidence Score |

| DBSCSNV | Database for Splicing Consensus SNVs |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| FLAIR | Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery |

| FSH | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone |

| GRP78 | Glucose-Regulated Protein 78 |

| HGNC | HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee |

| HSPA5 | Heat Shock Protein Family A (Hsp70) Member 5 |

| I-TASSER | Iterative Threading Assembly Refinement |

| LP | Likely Pathogenic |

| LH | Luteinizing Hormone |

| LOVD | Leiden Open Variation Database |

| MAF | Minor Allele Frequency |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MSS | Marinesco–Sjögren Syndrome |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NEF | Nucleotide Exchange Factor |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| OMIM | Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man |

| PPI | Protein–Protein Interaction |

| PP3 | Supporting Pathogenicity Criterion 3 |

| PVS1 | Pathogenic Very Strong 1 |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SIL1 | SIL1 Nucleotide Exchange Factor |

| STRING | Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| UPR | Unfolded Protein Response |

| VUS | Variant of Uncertain Significance |

| WES | Whole-Exome Sequencing |

| WT | Wild Type |

| XBP1 | X-Box Binding Protein 1 |

References

- Anttonen, A.-K. Marinesco–Sjögren Syndrome; GeneReviews®: Seattle, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anttonen, A.-K.; Mahjneh, I.; Hämäläinen, R.H.; Lagier-Tourenne, C.; Kopra, O.; Waris, L.; Anttonen, M.; Joensuu, T.; Kalimo, H.; Paetau, A.; et al. The gene disrupted in Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome encodes SIL1, an HSPA5 cochaperone. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 1309–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, M.; Roos, A.; Stendel, C.; Claeys, K.G.; Sonmez, F.M.; Baudis, M.; Bauer, P.; Bornemann, A.; de Goede, C.; Dufke, A.; et al. SIL1 mutations and clinical spectrum in patients with Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome. Brain 2013, 136, 3634–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senderek, J.; Krieger, M.; Stendel, C.; Bergmann, C.; Moser, M.; Breitbach-Faller, N.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S.; Blaschek, A.; I Wolf, N.; Harting, I.; et al. Mutations in SIL1 cause Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome, a cerebellar ataxia with cataract and myopathy. Nat. Genet. 2005, 37, 1312–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, A.; Kollipara, L.; Buchkremer, S.; Labisch, T.; Brauers, E.; Gatz, C.; Lentz, C.; Gerardo-Nava, J.; Weis, J.; Zahedi, R.P. Cellular signature of SIL1 depletion: Disease pathogenesis due to alterations in protein composition beyond the ER machinery. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 5527–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichhaporia, V.P.; Hendershot, L.M. Role of the HSP70 co-chaperone SIL1 in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, S.; Dlamini, N.; Lumsden, D.; Pitt, M.; Zaharieva, I.; Muntoni, F.; King, A.; Robert, L.; Jungbluth, H. SIL1-related Marinesco–Sjoegren syndrome (MSS) with associated motor neuronopathy and bradykinetic movement disorder. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2015, 25, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvers, M.; Anttonen, A.K.; Lehesjoki, A.E.; Morava, E.; Wortmann, S.; Vermeer, S.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.; Willemsen, M.A. Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome due to SIL1 mutations with a comment on the clinical phenotype. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2013, 17, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchkremer, S.; González Coraspe, J.A.; Weis, J.; Roos, A. Sil1-Mutant Mice Elucidate Chaperone Function in Neurological Disorders. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2016, 3, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kelley, L.A.; Mezulis, S.; Yates, C.M.; Wass, M.N.; Sternberg, M.J.E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Pearce, R.; Bell, E.W.; Zhang, Y. Folding non-homologous proteins by coupling deep-learning contact maps with I-TASSER assembly simulations. Cell Rep. Methods 2021, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, Y. Improving the physical realism and structural accuracy of protein models by a two-step atomic-level energy minimization. Biophys. J. 2011, 101, 2525–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.T.; Shen, Y.; Hendershot, L.M. BAP, a mammalian BiP-associated protein, is a nucleotide exchange factor that regulates the ATPase activity of BiP. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 47557–47563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, R.; Rawat, P.; Thangakani, A.M.; Kumar, S.; Gromiha, M.M. Protein aggregation: In silico algorithms and applications. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 13, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurenko, S. Predicting protein stability and solubility changes upon mutations: Data perspective. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 5590–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, O.B.V.; Pringle, M.A.; Schopp, I.M.; Braakman, I.; Bulleid, N.J. ERdj5 is the ER reductase that catalyzes the removal of non-native disulfides and correct folding of the LDL receptor. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, M.A.; Parsian, A.J.; Cleves, M.A.; Bracey, J.; Elsayed, M.S.; Elsobky, E.; Parsian, A. A novel mutation in BAP/SIL1 gene causes Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome in an extended pedigree. Clin. Genet. 2006, 70, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahata, T.; Yamada, K.; Yamada, Y.; Ono, S.; Kinoshita, A.; Matsuzaka, T.; Yoshiura, K.; Kitaoka, T. Novel mutations in the SIL1 gene in a Japanese pedigree with the Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 55, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatz, C.; Hathazi, D.; Münchberg, U.; Buchkremer, S.; Labisch, T.; Munro, B.; Horvath, R.; Töpf, A.; Weis, J.; Roos, A. Identification of cellular pathogenicity markers for SIL1 mutations linked to Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttonen, A.K.; Siintola, E.; Tranebjaerg, L.; Iwata, N.K.; Bijlsma, E.K.; Meguro, H.; Ichikawa, Y.; Goto, J.; Kopra, O. Novel SIL1 mutations and exclusion of functional candidate genes in Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 16, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathazi, D.; Cox, D.; d’Amico, A.; Tasca, G.; Charlton, R.; Carlier, R.Y.; Baumann, J.; Kollipara, L.; Zahedi, R.P.; Feldmann, I.; et al. INPP5K and SIL1 associated pathologies with overlapping clinical phenotypes converge through dysregulation of PHGDH. Brain 2021, 144, 2427–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochdi, K.; Cerino, M.; Da Silva, N.; Delague, V.; Bouzidi, A.; Nahili, H.; Zouiri, G.; Kriouile, Y.; Gorokhova, S.; Bartoli, M.; et al. Identification of novel mutations by targeted NGS in Moroccan families clinically diagnosed with a neuromuscular disorder. Clin. Chim. Acta 2022, 524, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faheem, A.; Masud, R.; Nasir, R.; Awan, Z.K.; Nasir, H.A.; Khan, Z.K.; Fayyaz, H.; Raza, S.I. Exome sequencing revealed variants in SGCA and SIL1 genes underlying limb girdle muscular dystrophy and Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome patients. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaguma, Y.; Hamada, N.; Tabata, H.; Iwamoto, I.; Mizuno, M.; Nishimura, Y.V.; Ito, H.; Morishita, R.; Suzuki, M.; Ohno, K.; et al. SIL1, a causative cochaperone gene of Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome, plays an essential role in establishing the architecture of the developing cerebral cortex. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | SIL1 |

|---|---|

| Transcript (RefSeq) | NM_022464.5 |

| Variant | c.453+1G>T |

| Dbsnp | Novel |

| Genomic coordinate | chr5:138,378,308 (GRCh37/hg19) |

| Exon/Intron | Intron 5 (canonical + 1 splice-donor) |

| Variant type | Splice donor variant |

| Zygosity | Homozygous |

| Inheritance/Segregation | Autosomal recessive; parents heterozygous carriers (Aa); sibling AA unaffected (reported) |

| dbSNP | Not listed |

| ClinVar | Not found |

| LOVD | Not found |

| gnomAD (exomes/genomes) | Not found |

| Protein domain | Nucleotide exchange factor (Fes1-like) |

| Conservation | Conserved |

| Computational—dbscSNV | Pathogenic (score not provided) |

| Computational—MaxEntScan | Pathogenic (Δscore not provided) |

| Computational—BayesDel | Pathogenic |

| Computational—DANN | Pathogenic |

| Computational—SpliceAI | Not reported |

| Computational—CADD | Not reported |

| Aggregated prediction | Pathogenic |

| ACMG evidence | PVS1, PM2, PP3 |

| ACMG classification | Pathogenic |

| Phenotype summary | Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism: FSH 50.53 mIU/mL (↑), LH 40.64 mIU/mL (↑), total testosterone 209.9 ng/dL (↓); thyroid axes within reference. |

| Reference | SIL1 Variant (NM_022464.5) | Zygosity | Exon(s) | Eye Findings | Brain Abnormality | Skeletal Findings | Development | Muscle Findings | Other Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senderek et al., 2005 [4] | c.1029+1G>A; c.645+1G>A | HM | 6, 9 | congenital cataracts | cerebellar atrophy | short stature | psychomotor delay | myopathic EMG; ataxia; hypotonia | |

| Anttonen et al., 2005 [2] | c.331C>T; c.212dupA; c.506_509dupAAGA; (c.506_509dupAAGA+645+2T>C CHT) | HM | 4, 9 | bilateral cataracts | cerebellar atrophy | short stature | unstable gait; ataxia; loss of ambulation (~20 yrs) | ||

| Karim et al., 2006 [17] | c.1312C>T (p.Gln438Ter) | HM | 10 | cataracts ± | delayed motor & mental development | progressive weakness; hypotonia, cerebellar ataxia | hypogonadism | ||

| Takahata et al., 2010 [18] | c.603_607del (p.Glu201AspfsTer6) | HM | 6 | cataracts; | spasticity | Ataxia; skeletal deformities; myopathy; hypotonia | |||

| Krieger et al., 2013 [3] | Multiple (19 variants incl. c.16C>T; c.936dupG; c.1312C>T; c.1370T>C) | HM/CHT | 4, 6, 9, 10 | congenital cataracts | microcephaly | skeletal deformities | psychomotor delay | hypotonia; ataxia; ↑ CK | hypogonadism |

| Horvers et al., 2013 [8] | c.1060C>T (p.Gln354Ter); c.935G>A (p.Gly312Glu); c.645+2T>C | HM/CHT | 6, 9, 10 | cataracts (3–5 yrs) | cerebellar atrophy | skeletal deformities | mild intellectual disability | ataxia; myopathy | |

| Gatz et al., 2019 [19] | c.1370T>C (p.Leu457Pro) | HM | 10 | dysarthria; congenital cataracts | microcephaly | psychomotor delay | limb/truncal ataxia; hypotonia | ||

| Anttonen et al., 2008 [20] | c.1042dupG (p.Glu348GlyfsTer4) | HM | 9 | hyperopia vs. cataracts; strabismus; nystagmus | global developmental delay | cerebellar ataxia; myopathy | |||

| Hathazi et al., 2021 [21] | c.645+1G>A; c.947_948insT; c.1030–18G>A | HM/CHT | 6, 10 | cataracts | microcephaly; cerebellar atrophy | intellectual disability | progressive myopathy | overlap with INPP5K phenotype | |

| Rochdi et al., 2022 [22] | c.453+5G>A | HM | 6 | bilateral cataracts | mild skeletal abnormalities | intellectual disability | cerebellar ataxia; hypotonia | ||

| Faheem et al., 2024 [23] | c.936dupG (p.Leu313AlaFsTer39) | HM | 9 | cataracts; strabismus | cerebellar atrophy | ataxia; hypotonia; abnormal gait; ↑ CK | |||

| Our study | c.453+1G>T (novel) | HM | 5 | bilateral cataracts | kyphoscoliosis; pectus excavatum | mild intellectual disability | cerebellar ataxia; hypotonia | hypergonadotropic hypogonadism; synophrys |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aslan, E.S.; Eslamkhah, S.; Akcali, N.; Yavas, C.; Karcioglu Batur, L.; Sengenc, E.; Yüksel, A. Marinesco–Sjögren Syndrome: A Novel SIL1 Variant with In Silico Analysis and Review of the Literature. Life 2025, 15, 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121855

Aslan ES, Eslamkhah S, Akcali N, Yavas C, Karcioglu Batur L, Sengenc E, Yüksel A. Marinesco–Sjögren Syndrome: A Novel SIL1 Variant with In Silico Analysis and Review of the Literature. Life. 2025; 15(12):1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121855

Chicago/Turabian StyleAslan, Elif Sibel, Sajjad Eslamkhah, Nermin Akcali, Cuneyd Yavas, Lutfiye Karcioglu Batur, Esma Sengenc, and Adnan Yüksel. 2025. "Marinesco–Sjögren Syndrome: A Novel SIL1 Variant with In Silico Analysis and Review of the Literature" Life 15, no. 12: 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121855

APA StyleAslan, E. S., Eslamkhah, S., Akcali, N., Yavas, C., Karcioglu Batur, L., Sengenc, E., & Yüksel, A. (2025). Marinesco–Sjögren Syndrome: A Novel SIL1 Variant with In Silico Analysis and Review of the Literature. Life, 15(12), 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121855