Diversity of Groundwater Microbial Communities near Sludge Repositories with Different Types and Levels of Pollution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.2.1. Hydrochemical Analysis

2.2.2. Molecular Analysis

2.2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

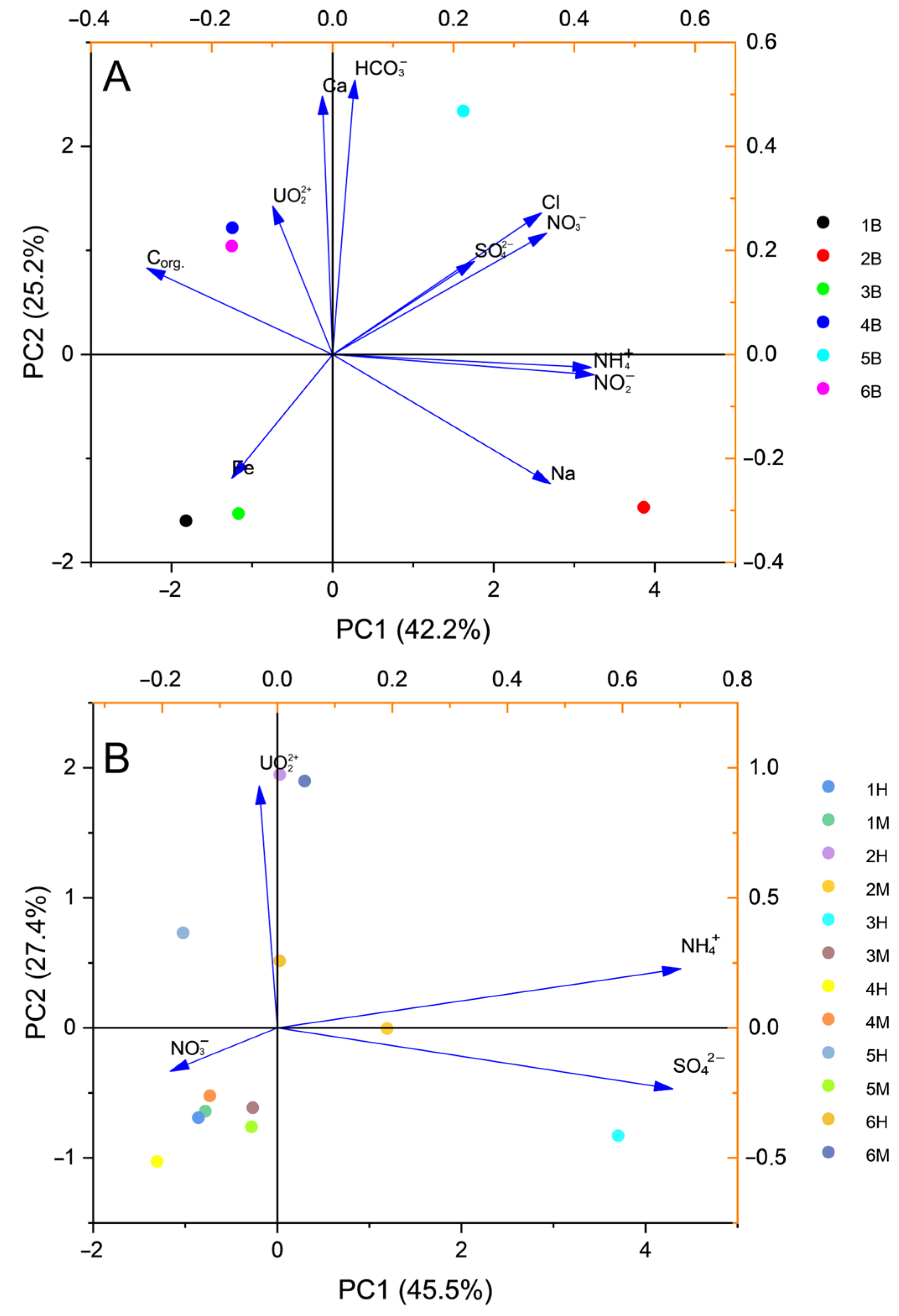

3.1. Comparison of Sample Chemical Composition

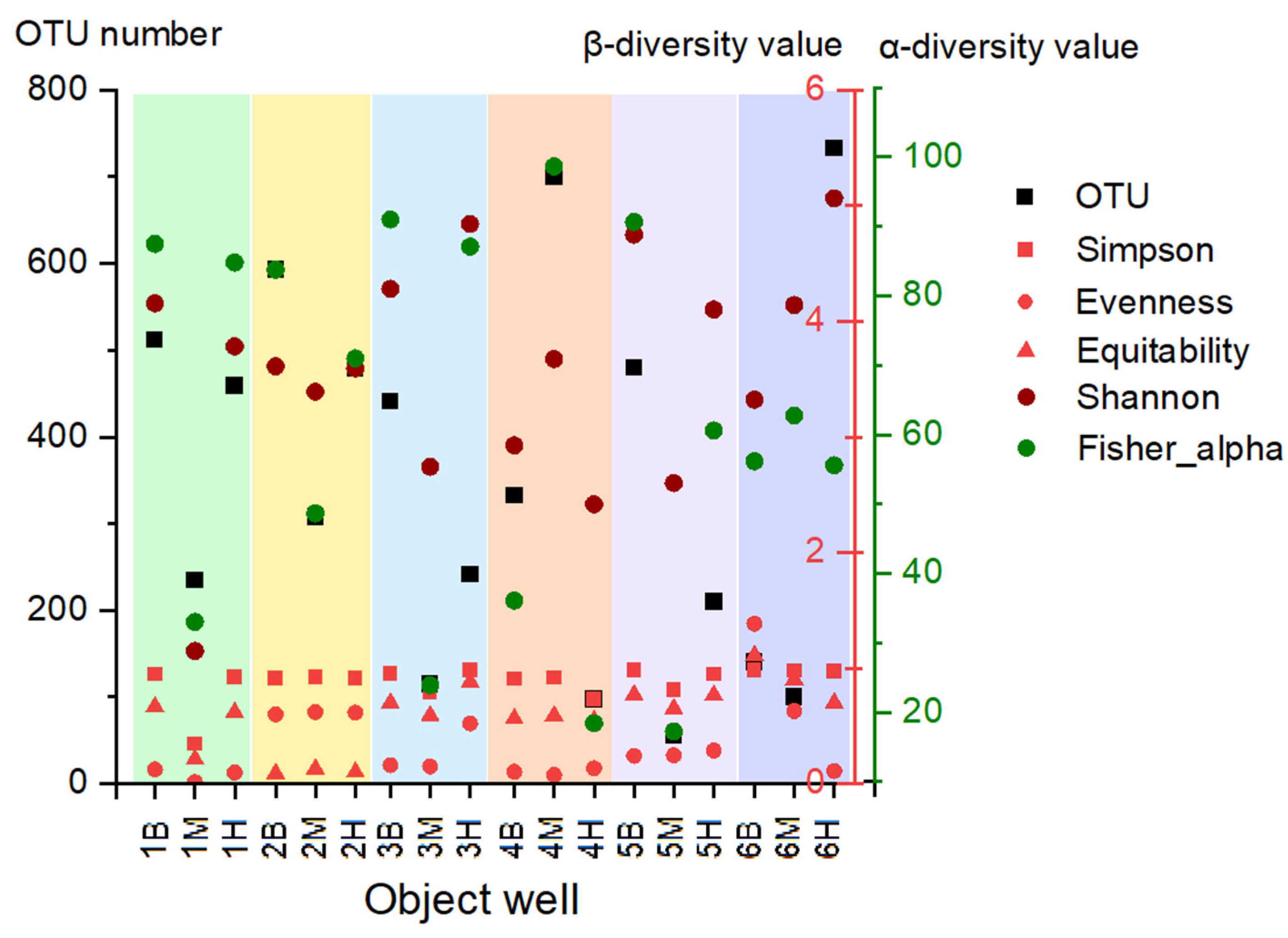

3.2. Characterization of Biodiversity in Background and Polluted Samples

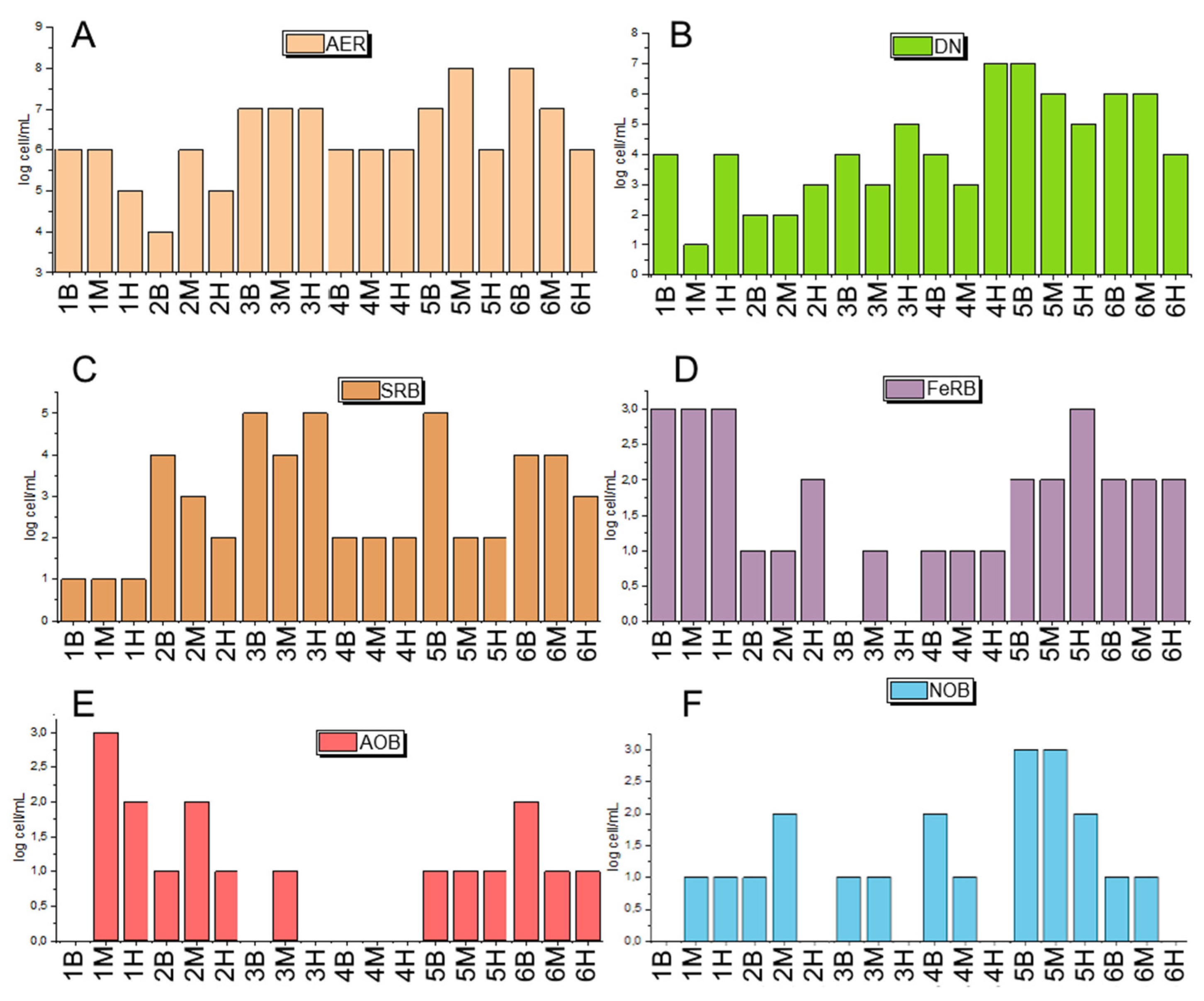

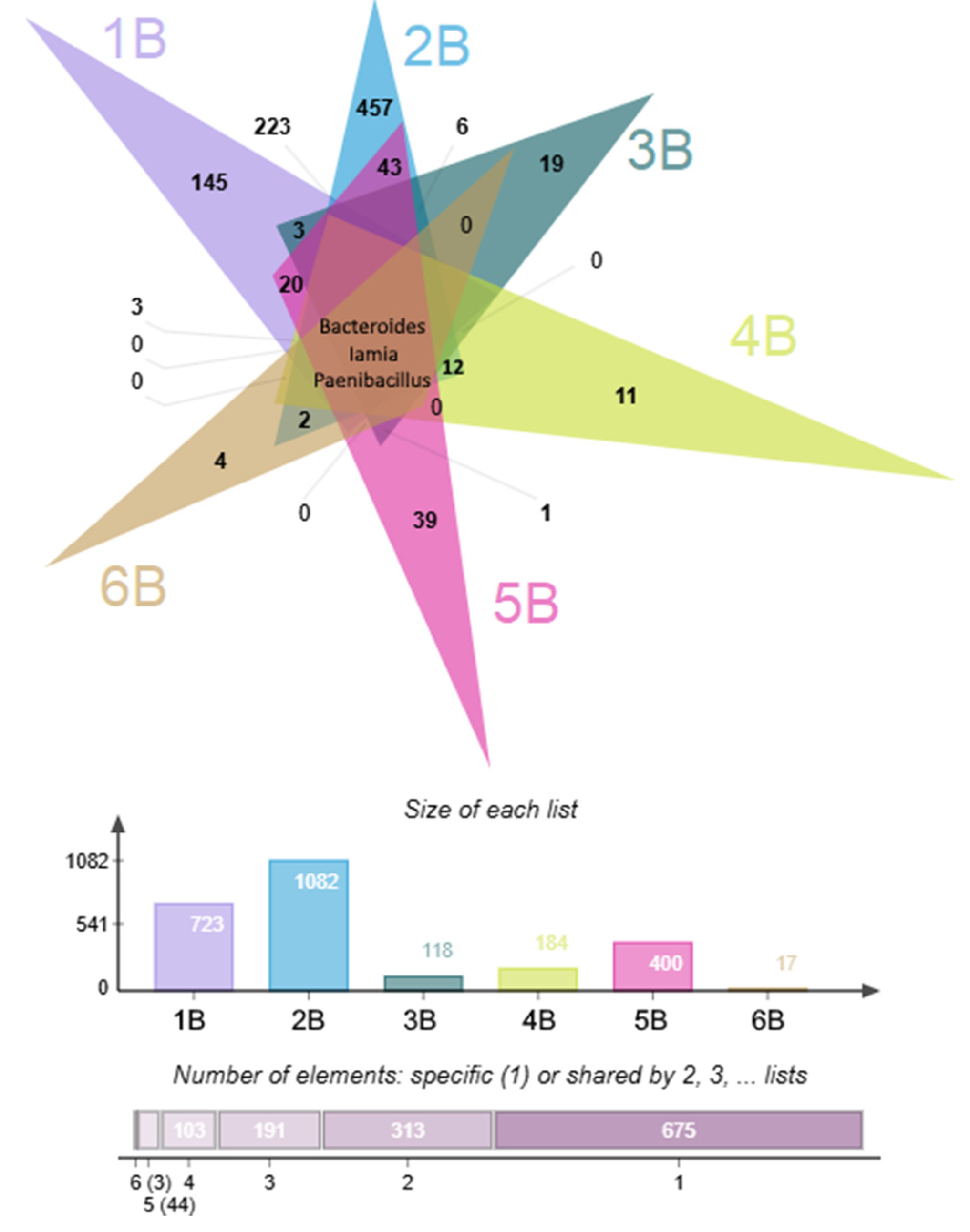

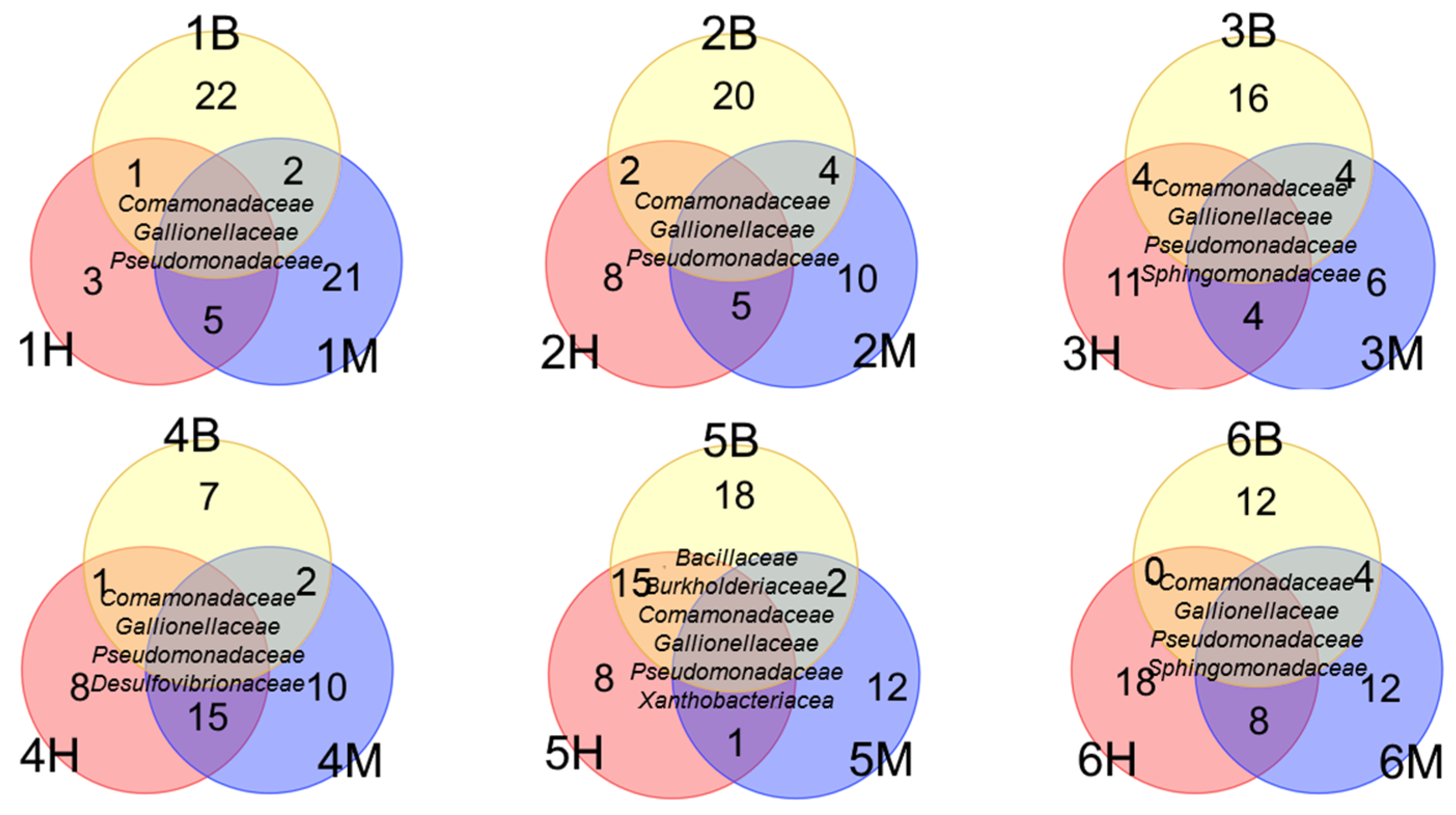

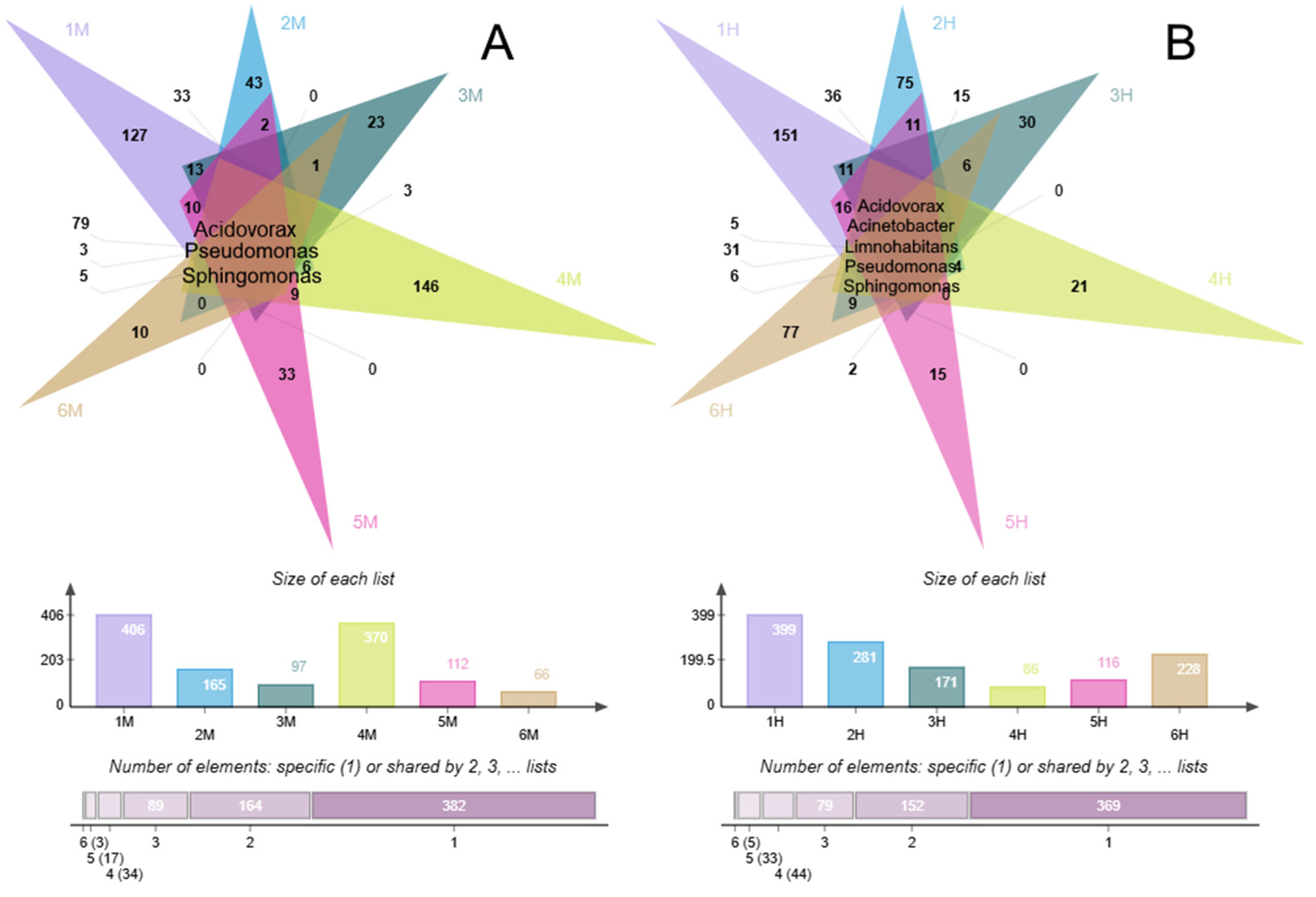

3.2.1. Microbial Diversity Gradients Relative to Pollution Sources

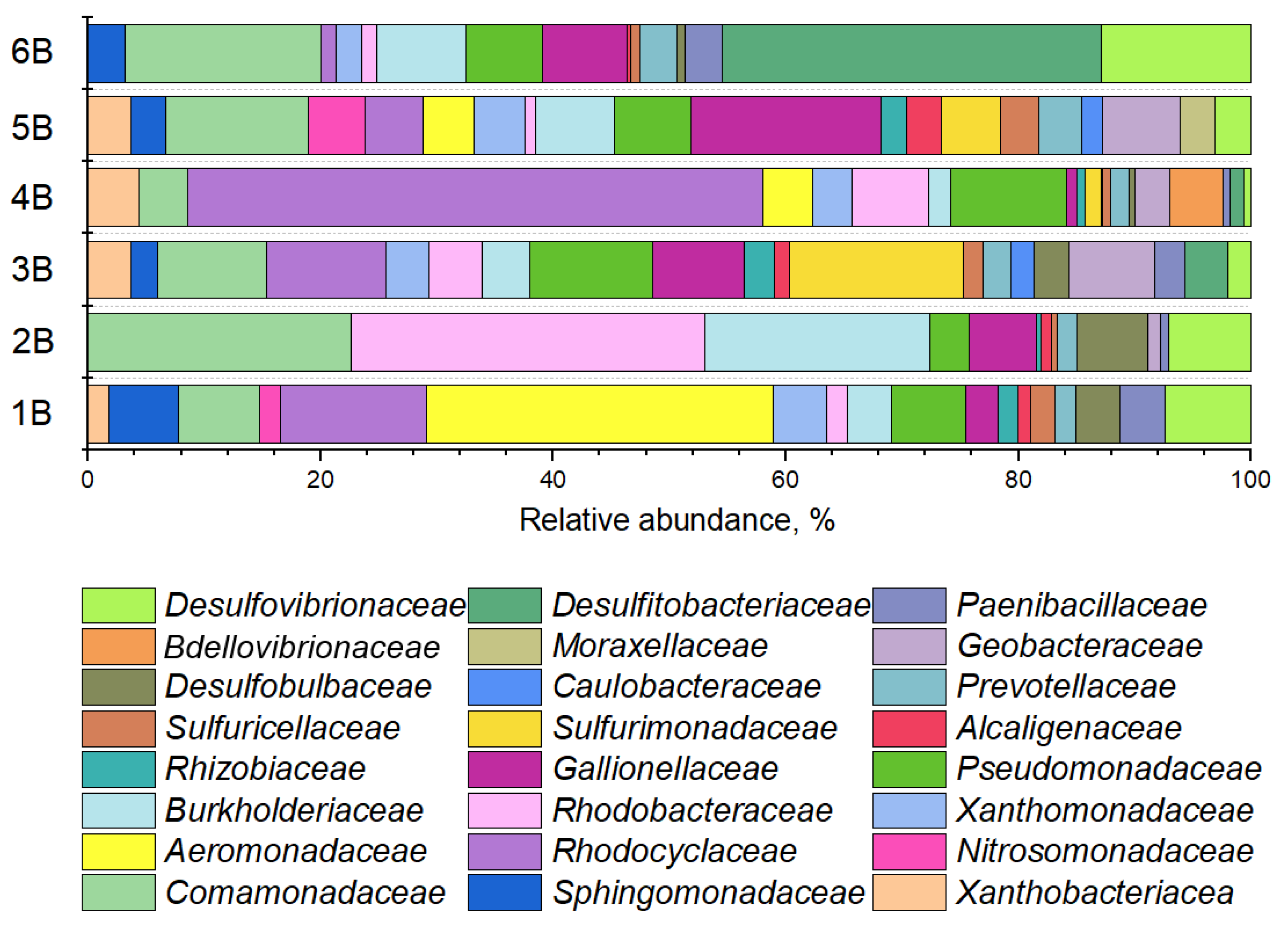

3.2.2. Phylogenetic Composition of Background Samples

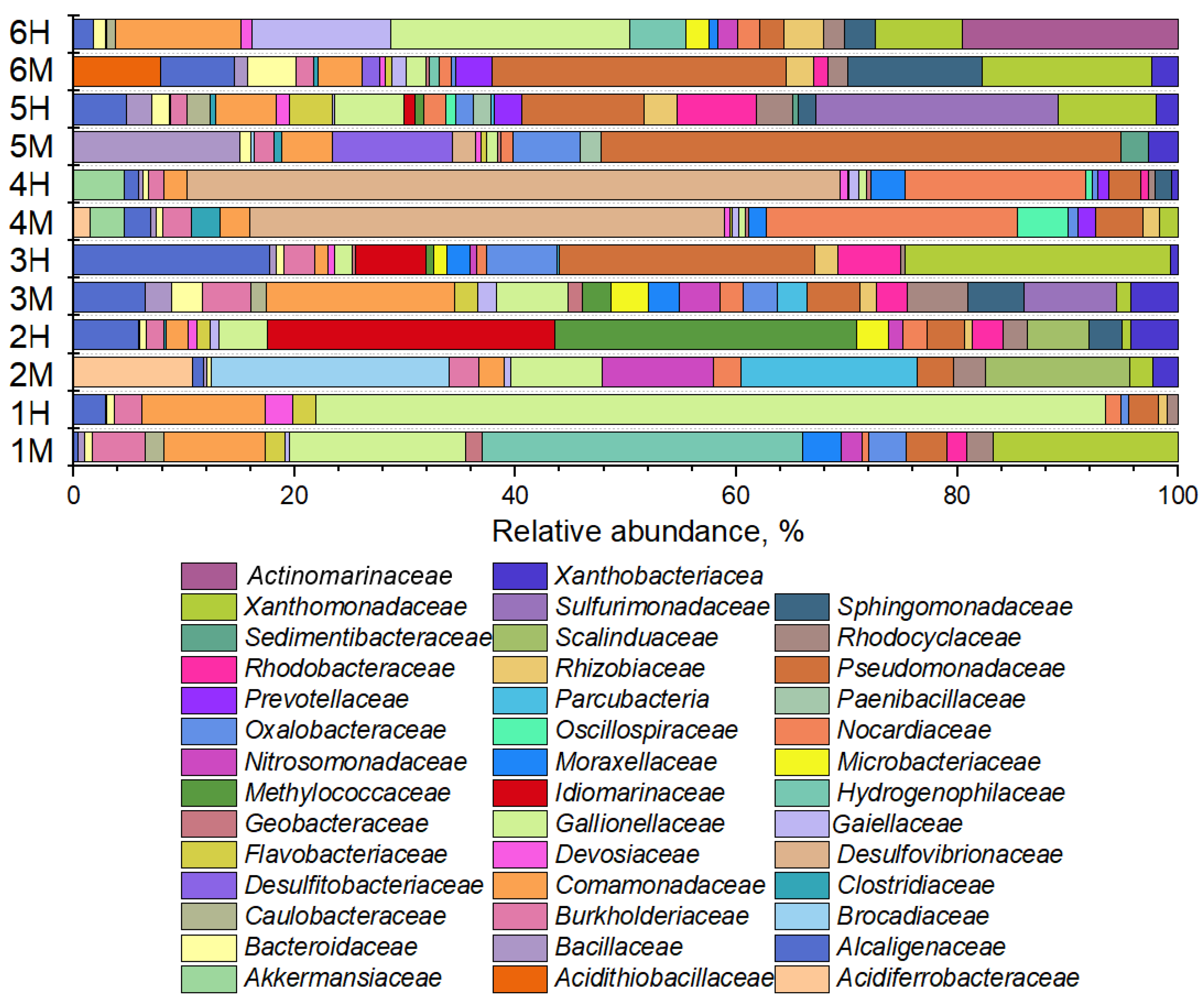

3.2.3. Phylogenetic Composition of Polluted Samples

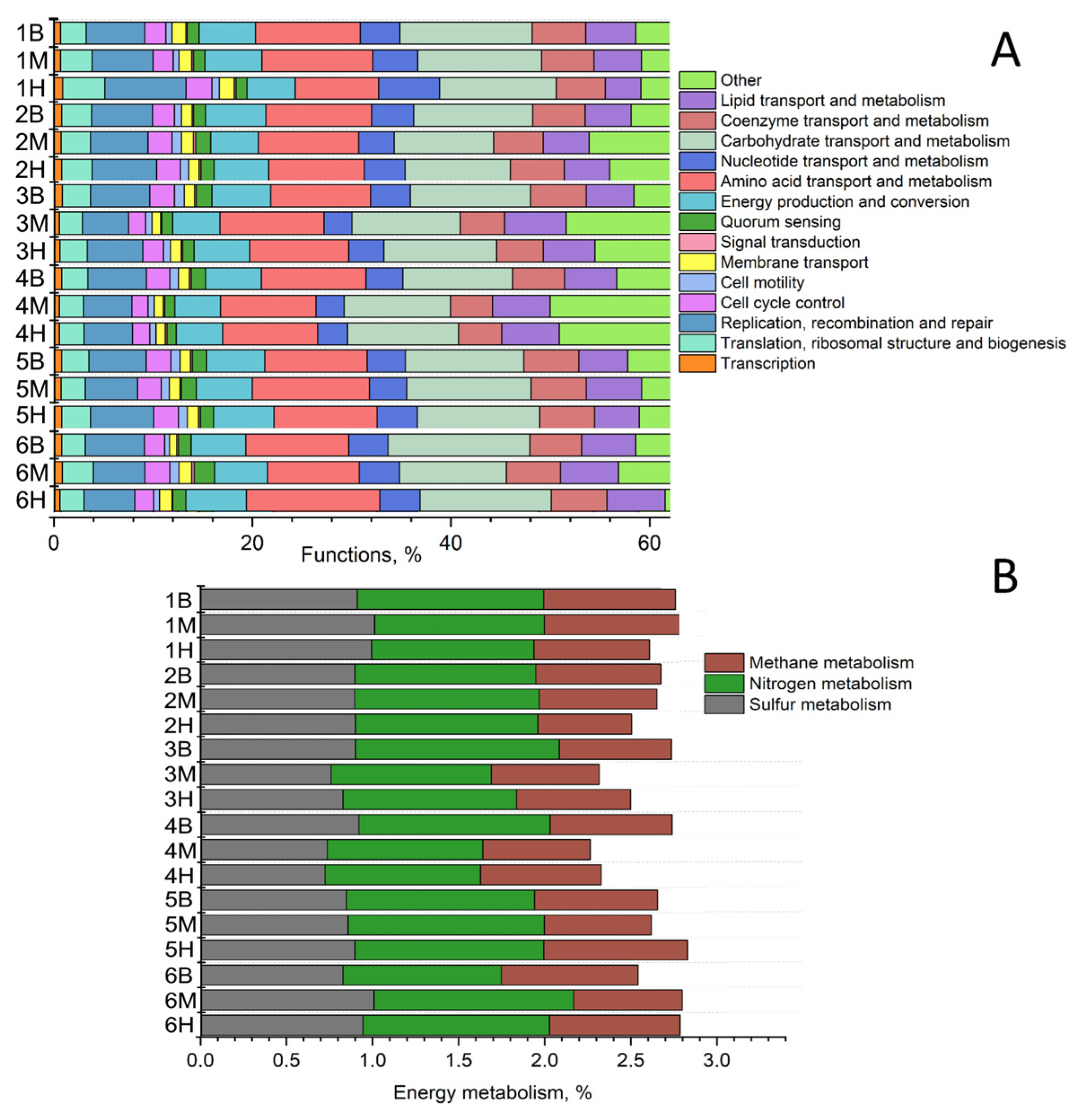

3.3. Metabolic Potential of Microbial Communities

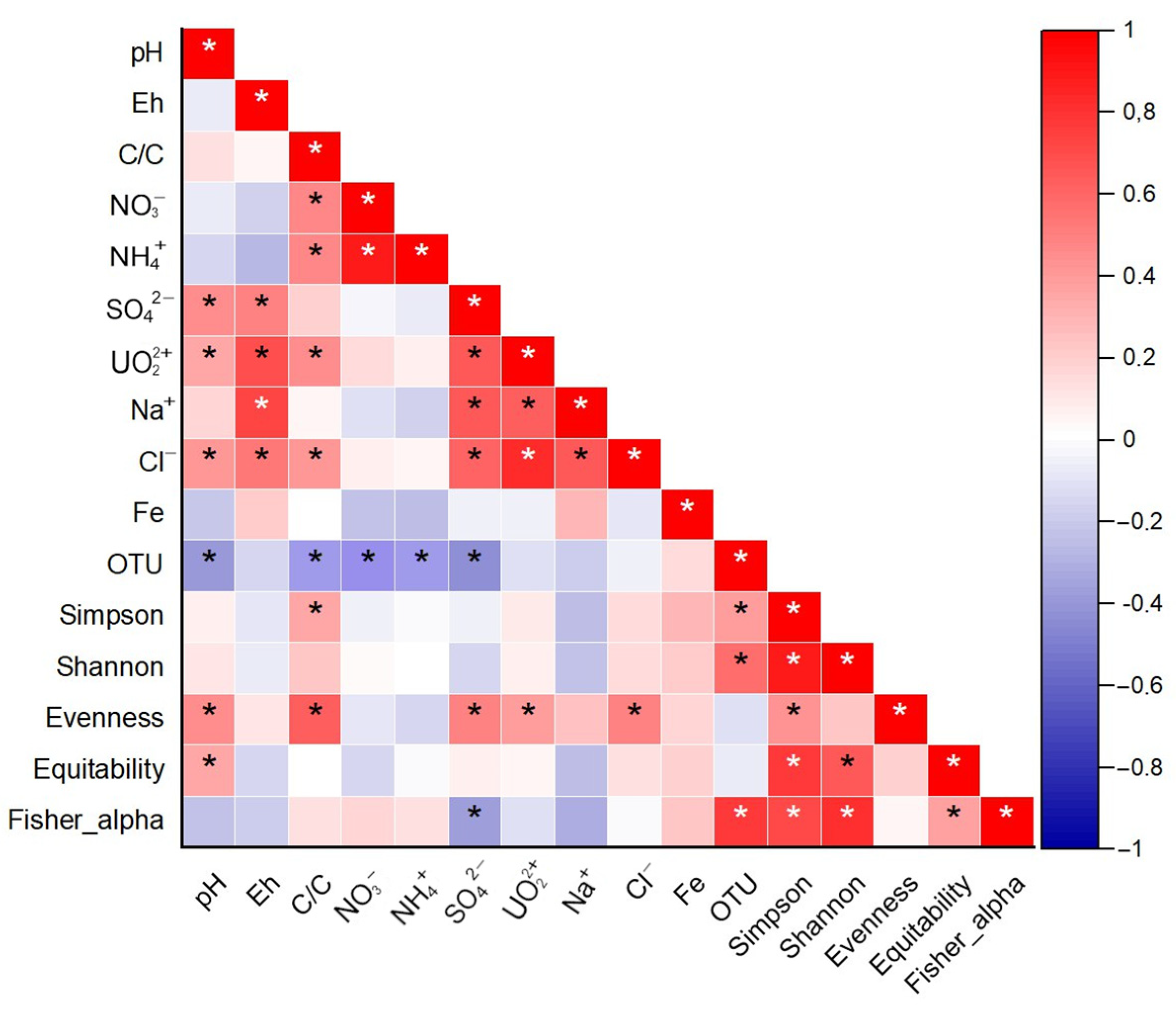

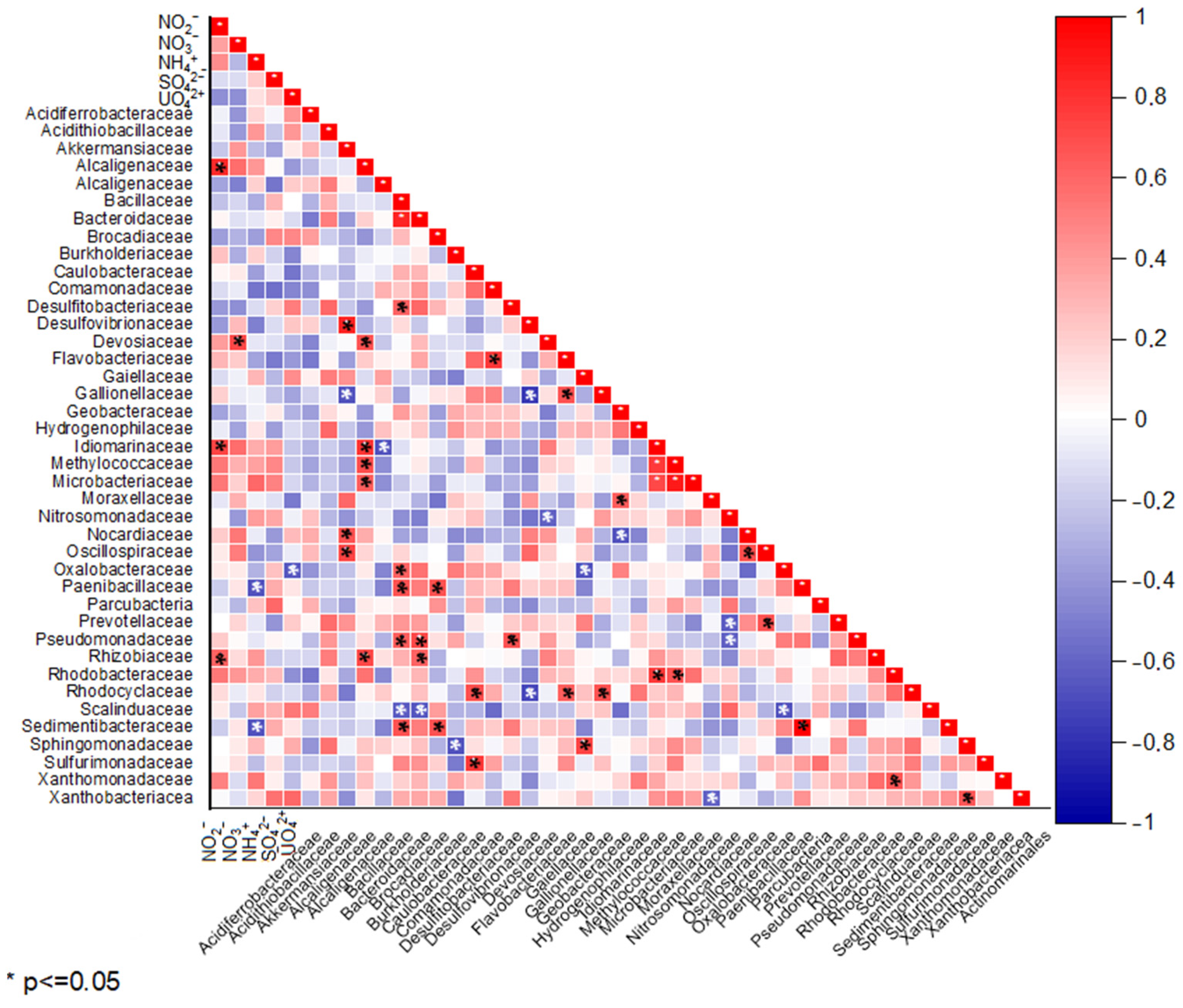

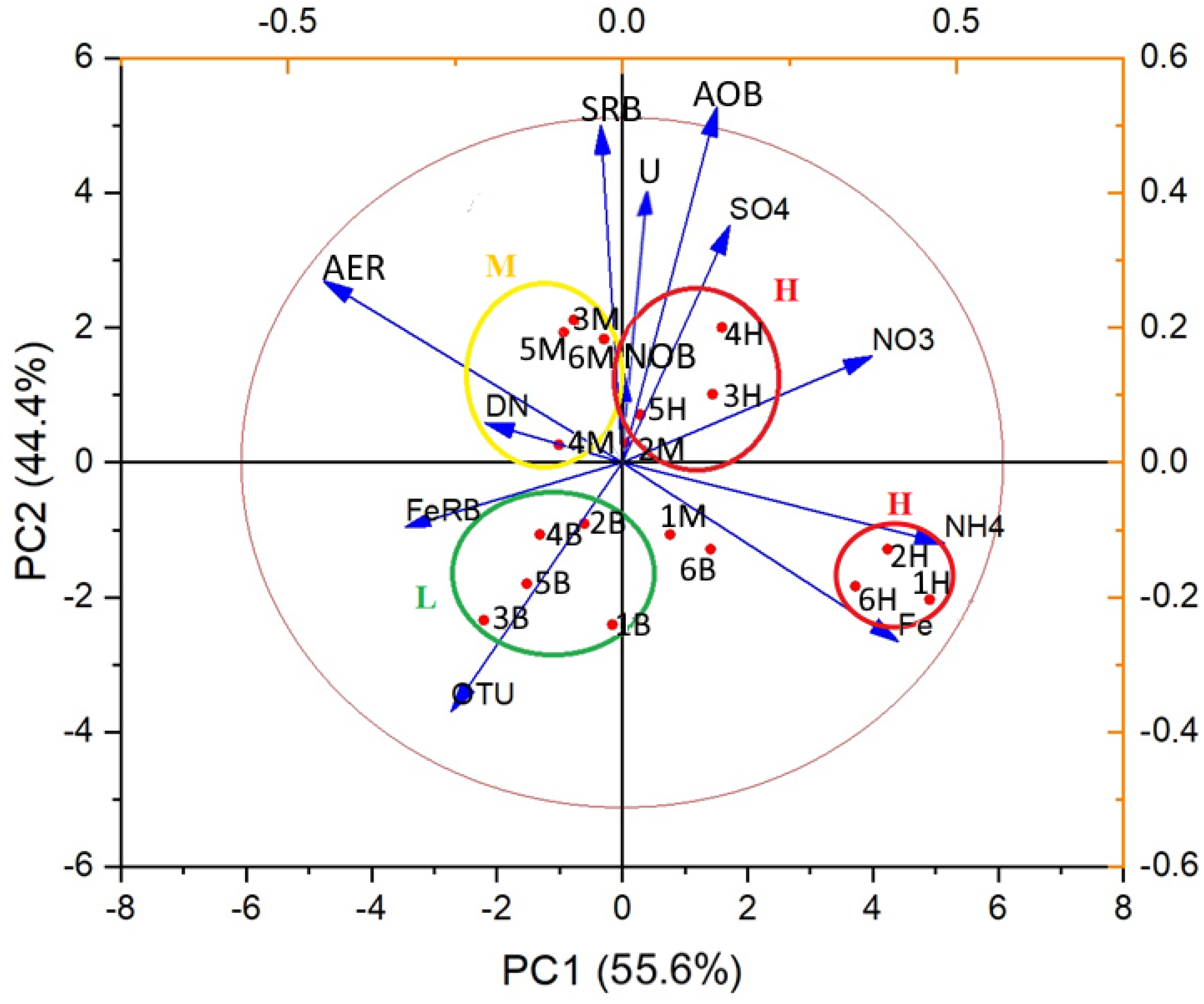

3.4. Correlation Analyses of Hydrochemical and Microbiological Parameters

4. Discussion

Prospects for In Situ Bioremediation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Bacterial Group | Media Composition |

|---|---|

| Aerobic organotrophic bacteria | 10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 1 g/L glucose, pH = 7.5. |

| Denitrifying bacteria | Adkins medium for denitrifying bacteria (DB) contained (g/L): NH4Cl—1.0; KH2PO4—0.75; K2HPO4—1.5; NaNO3—1.0; NaCl—0.8; Na2SO4—0.1; MgSO4·7H2O—0.1; KCl—0.1, yeast extract—0.5; glucose—1.0; CH3COONa—1.0, pH = 7, gas phase—Ar. |

| Sulfate-reducing bacteria | Postgate B medium (g/L): NaCl —1.0; KH2PO4—0.5; NH4Cl—1.0; CaSO4·2H2O—1.0; MgSO4·7H2O—2; yeast extract—1.0; sodium lactate—4; Na2S·9H2O—0.2, pH = 7. |

| Nitrifying ammonium to nitrite | Winogradskiy medium for stage I nitrifiers (AOB) contained (g/L tap water): (NH4)2SO4—2.0; K2HPO4—1.0; MgSO4 ∙ 7H2O—0.5; NaCl—2.0; FeSO4 ∙ 7H2O—0.05; CaCO3—5.0, pH = 8. |

| Nitrifying nitrite to nitrate | Winogradskiy medium for stage II nitrifiers (NOB) contained (g/L tap water): NaNO2—1.0; K2HPO4—0.5; MgSO4 ∙ 7H2O—0.5; NaCl—0.5; FeSO4 ∙ 7H2O—0.4; Na2CO3—1.0, pH = 8. |

| Iron reducing bacteria | Modified IRB medium (g/L tap water): CaCl2 ∙ 2H2O—0.1; NaH2PO4—0.6; MgCl2 ∙ 6H2O—0.1; MgSO4 ∙ 7H2O—0.1; MnCl2 ∙ 4H2O—0.005; Na2MoO4∙ 2H2O—0.001; NH4Cl—1.0; KCl—0.1; NaCl—0.1; NaHCO3—2.0; yeast extract—0.5; CH3COONa—0.75; Iron(III) citrate —1.5, pH = 7. |

| Sample | pH | eH mV | C/C mg/L | NO3− mg/L | NO2− mg/L | HCO3− mg/L | SO42− mg/L | NH4+ mg/L | Ca2+ mg/L | U mg/L | Corg. mg/L | Na mg/L | Cl mg/L | ∑Fe mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1B | 7.06 | −30 | 127 | <0.20 | 0.23 | 79.3 | 1.8 | <0.5 | 17.5 | <0.01 | 12.2 | 4.06 | 1.44 | 4.8 |

| 1M | 6.06 | 65 | 5070 | 1500 | 17.4 | 241 | 152 | 1.7 | 305 | 0.06 | 14.5 | 245 | 1.4 | 4.3 |

| 1H | 6.56 | 78 | 7000 | 2680 | 34.5 | 357 | 79.3 | 6.2 | 308.6 | 0.72 | 18.7 | 639 | 4.42 | 17.5 |

| 2B | 7.38 | −105 | 127 | 11.5 | 2.8 | 53.8 | 21.4 | 7.83 | 13.2 | <0.01 | 3.3 | 100 | 10.9 | 2.1 |

| 2M | 6.6 | 78 | 7900 | 2240 | 48.9 | 1056 | 2370 | 361 | 630.9 | 0.06 | 16.9 | 465 | 42 | 4.1 |

| 2H | 7.4 | 134 | 12,800 | 4300 | 56.6 | 1004 | 970 | 216 | 2190 | 0.43 | 23.1 | 2790 | 2300 | 5.1 |

| 3B | 7.39 | −115 | 173 | 0.8 | 0.02 | 126.9 | 26.7 | 0.9 | 33.8 | <0.01 | 3.7 | 5.25 | 0.5 | 13.9 |

| 3M | 9.26 | −50 | 2700 | 789 | 6.9 | 180.6 | 974.7 | 61 | 461 | 0.09 | 4.8 | 20.6 | 2.2 | 0.7 |

| 3H | 8.03 | −3 | 10,500 | 3290 | 52.1 | 197.6 | 8248 | 569 | 1283 | 0.04 | 9.1 | 117.8 | 119 | 0.27 |

| 4B | 7.7 | −273 | 550 | 8.54 | 0.06 | 267 | 16 | 1.21 | 46 | <0.01 | 13.7 | 6.21 | 3.3 | 0.7 |

| 4M | 6.41 | 34 | 6620 | 2333.5 | 48.9 | 294 | 142.5 | 29.6 | 1143.5 | 0.12 | 6 | 67.4 | 107 | 0.6 |

| 4H | 7.4 | 80 | 17,010 | 11,200 | 0.06 | 195 | 358 | 1.17 | 2960 | 0.14 | 6.1 | 137 | 66 | 0.9 |

| 5B | 7.1 | −190 | 729 | 12.02 | 1.4 | 549 | 30 | 3.71 | 123 | <0.01 | 5.5 | 0.24 | 11 | 3.4 |

| 5M | 7.8 | −28 | 3743 | 1124 | 0.6 | 161 | 1769 | 0.23 | 56 | 1.58 | 14.9 | 685 | 590 | 2.6 |

| 5H | 7.97 | 90 | 12,109 | 6169 | 44.7 | 180 | 470 | 1.03 | 1436 | 0.02 | 14.6 | 1249 | 3200 | 12.3 |

| 6B | 7.09 | −50 | 743 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 243.7 | 12.7 | 2.4 | 114.1 | <0.01 | 11.8 | 6.2 | 8.6 | 6.1 |

| 6M | 7.72 | 98 | 2680 | 209 | 11.8 | 358.5 | 278.2 | 273.8 | 24.7 | 2.04 | 6.5 | 42.5 | 19.2 | 2.3 |

| 6H | 7.34 | 110 | 1706 | 121.7 | 21.9 | 412.6 | 290.7 | 188.9 | 1188 | 0.82 | 12.7 | 125.7 | 45.7 | 2.4 |

| Sample | Standard deviation | |||||||||||||

| pH | eH | C/C | NO3− | NO2− | HCO3− | SO42− | NH4+ | Ca2+ | U | Corg. | Na | Cl | Fe | |

| 1B | 0.1 | −15 | 11.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 1M | 0.1 | 22 | 386.4 | 109.5 | 1.3 | 17.6 | 11.1 | 0.1 | 22.3 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 17.9 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| 1H | 0.1 | 15 | 442 | 195.6 | 2.5 | 26.1 | 5.8 | 0.5 | 22.5 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 46.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| 2B | 0.11 | −23 | 11.3 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 7.3 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| 2M | 0.1 | 14 | 476.3 | 163.5 | 3.6 | 77.1 | 173.0 | 26.4 | 46.1 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 33.9 | 3.1 | 0.3 |

| 2H | 0.11 | 25 | 673.5 | 313.9 | 4.1 | 73.3 | 70.8 | 15.8 | 159.9 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 203.7 | 167.9 | 0.4 |

| 3B | 0.11 | −24 | 23.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 9.3 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| 3M | 0.2 | −16 | 145.8 | 57.6 | 0.5 | 13.2 | 71.2 | 4.5 | 33.7 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 3H | 0.15 | −5 | 578 | 240.2 | 3.8 | 14.4 | 602.1 | 41.5 | 93.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 0.0 |

| 4B | 0.12 | −24 | 78.3 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 19.5 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 4M | 0.1 | 12 | 229.5 | 170.3 | 3.6 | 21.5 | 10.4 | 2.2 | 83.5 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 4.9 | 7.8 | 0.0 |

| 4H | 0.11 | 15 | 673.5 | 817.6 | 0.0 | 14.2 | 26.1 | 0.1 | 216.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 10.0 | 4.8 | 0.1 |

| 5B | 0.1 | −21 | 43.2 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 40.1 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 9.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| 5M | 0.12 | −6 | 165.5 | 82.1 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 129.1 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 50.0 | 43.1 | 0.2 |

| 5H | 0.14 | 17 | 567.9 | 450.3 | 3.3 | 13.1 | 34.3 | 0.1 | 104.8 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 91.2 | 233.6 | 0.9 |

| 6B | 0.1 | −9 | 48.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 17.8 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 6M | 0.12 | 16 | 114.1 | 15.3 | 0.9 | 26.2 | 20.3 | 20.0 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.2 |

| 6H | 0.11 | 27 | 92.6 | 8.9 | 1.6 | 30.1 | 21.2 | 13.8 | 86.7 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 9.2 | 3.3 | 0.2 |

| Parameter | F-Value | p-Value | η2 (Partial eta-Squared) | Group Difference (Tukey HSD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO3− | 45.217 | 2.14 × 10−9 * | 0.834 | B < M < H (p < 0.001) |

| NH4+ | 62.893 | 4.78 × 10−11 * | 0.875 | B < M < H (p < 0.001) |

| SO42− | 38.542 | 1.56 × 10−8 * | 0.811 | B < M, B < H, M ≠ H (p < 0.01) |

| U | 51.634 | 5.23 × 10−10 * | 0.851 | B < M < H (p < 0.001) |

| Fe | 89.326 | 2.45 × 10−13 * | 0.908 | B < M < H (p < 0.001) |

| OTU | 28.194 | 3.67 × 10−7 * | 0.758 | B > M, B > H, M < H (p < 0.01) |

| Factor | F-Value | p-Value | η2 (Partial eta-Squared) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | 28.45 | <0.001 | 0.672 |

| Contamination level | 45.18 | <0.001 | 0.781 |

| Site/contamination level | 12.73 | <0.001 | 0.534 |

| Pollution Level | Background | Medium | High |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-value | 38.72 * | 42.15 * | 35.89 * |

References

- Cadotte, M.W.; Dinnage, R.; Tilman, D. Phylogenetic Diversity Promotes Ecosystem Stability. Ecology 2012, 93, S223–S233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Song, Y.; Fu, Q.; Qi, R.; Wu, Z.; Ge, F.; Lu, X.; An, W.; Han, W. Reclaimed Water Use Improved Polluted Water’s Self-Purification Capacity—Evidenced by Water Quality Factors and Bacterial Community Structure. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I.; Zalewski, M. Temporal Changes in the Abiotic/Biotic Drivers of Selfpurification in a Temperate River. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 94, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, W.; Williams, I.D.; Hudson, M.D. Metal Contamination in Water, Sediment and Biota from a Semi-Enclosed Coastal Area. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 3879–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, S.A. On the Biotic Self-Purification of Aquatic Ecosystems: Elements of the Theory. Doklady biological sciences: Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Biological sciences sections/translated from Russian. Dokl. Biol. Sci. 2004, 396, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, L.; Solomon, K.; Sibley, P.; Hall, K.; Keen, P.; Mattu, G.; Linton, B. Sources, Pathways, and Relative Risks of Contaminants in Surface Water and Groundwater: A Perspective Prepared for the Walkerton Inquiry. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2002, 65, 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Boguslavskii, A.E.; Gas’kova, O.L.; Shemelina, O.V. Geochemical Model of the Environmental Impact of Low-Level Radioactive Sludge Repositories in the Course of Their Decommissioning. Radiochemistry 2016, 58, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguslavsky, A.E.; Gaskova, O.L.; Naymushina, O.S.; Popova, N.M.; Safonov, A.V. Environmental Monitoring of Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal in Electrochemical Plant Facilities in Zelenogorsk, Russia. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 119, 104598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracino, A.; Phipps, H. Groundwater Contaminants and Contaminant Sources. Watersheds Groundw. Drink. Water A Pract. Guide 2008, 3497, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubimova, T.P.; Lepikhin, A.P.; Parshakova, Y.N.; Tsiberkin, K.B. Numerical Modeling of Liquid-Waste Infiltration from Storage Facilities into Surrounding Groundwater and Surface-Water Bodies. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 2016, 57, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowell, R.J.; Williams, K.P.; Connelly, R.J.; Sadler, P.J.K.; Dodds, J.E. Chemical Containment of Mine Waste. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 1999, 157, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessl, K.; Russ, A.; Vollprecht, D. Application and Development of Zero-Valent Iron (ZVI) for Groundwater and Wastewater Treatment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 6913–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Kechavarzi, C.; Sutherland, K.; Ng, M.Y.A.; Soga, K.; Tedd, P. Laboratory and In Situ Tests for Long-Term Hydraulic Conductivity of a Cement-Bentonite Cutoff Wall. J. Geotech. Geoenvironm. Eng. 2010, 136, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasundara, R.B.C.D.; Udayagee, K.P.P.; Karunarathna, A.K.; Manage, P.M.; Nugara, R.N.; Abhayapala, K.M.R.D. Permeable Reactive Barriers as an In Situ Groundwater Remediation Technique for Open Solid Waste Dumpsites: A Review and Prospect; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- Valhondo, C.; Carrera, J.; Martínez-Landa, L.; Wang, J.; Amalfitano, S.; Levantesi, C.; Diaz-Cruz, M.S. Reactive Barriers for Renaturalization of Reclaimed Water during Soil Aquifer Treatment. Water 2020, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagoyinbo, C.V.O.; Dairo, V.A. Groundwater Contamination and Effective Ways of Rectification. Pharmacogenomics 2016, 3, 1749–1756. [Google Scholar]

- Boguslavsky, A.; Shvartseva, O.; Popova, N.; Safonov, A. Biogeochemical In Situ Barriers in the Aquifers near Uranium Sludge Storages. Water 2023, 15, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majone, M.; Verdini, R.; Aulenta, F.; Rossetti, S.; Tandoi, V.; Kalogerakis, N.; Agathos, S.; Puig, S.; Zanaroli, G.; Fava, F. In Situ Groundwater and Sediment Bioremediation: Barriers and Perspectives at European Contaminated Sites. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artemiev, G.; Safonov, A. Authigenic Mineral Formation in Aquifers near the Uranium Sludge Storage Facility of Chepetsky Mechanical Plant during the Formation of a Biogeochemical Barrier in a Laboratory and Field Experiment. Minerals 2023, 13, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.H.; Bargar, J.R.; Lloyd, J.R.; Lovley, D.R. Bioremediation of Uranium-Contaminated Groundwater: A Systems Approach to Subsurface Biogeochemistry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P.E.; Williams, K.H.; Davis, J.A.; Fox, P.M.; Wilkins, M.J.; Yabusaki, S.B.; Fang, Y.; Waichler, S.R.; Berman, E.S.F.; Gupta, M.; et al. Bicarbonate Impact on U(VI) Bioreduction in a Shallow Alluvial Aquifer. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2015, 150, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Kelly, S.D.; Kemner, K.M.; Banfield, J.F. Direct Microbial Reduction and Subsequent Preservation of Uranium in Natural Near-Surface Sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Banfield, J.F. Geomicrobiology of Uranium. In Uranium: Mineralogy, Geochemistry, and the Environment; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, L.; Morris, K.; Lloyd, J.R. The Biogeochemistry and Bioremediation of Uranium and Other Priority Radionuclides. Chem. Geol. 2014, 363, 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.R. Microbial Reduction of Metals and Radionuclides. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.T.; Vrionis, H.A.; Ortiz-Bernad, I.; Resch, C.T.; Long, P.E.; Dayvault, R.; Karp, K.; Marutzky, S.; Metzler, D.R.; Peacock, A.; et al. Stimulating the In Situ Activity of Geobacter Species to Remove Uranium from the Groundwater of a Uranium-Contaminated Aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5884–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senko, J.M.; Istok, J.D.; Suflita, J.M.; Krumholz, L.R. In-Situ Evidence for Uranium Immobilization and Remobilization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 1491–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wu, W.M.; Wu, L.; He, Z.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; Deng, Y.; Luo, J.; Carley, J.; Ginder-Vogel, M.; Gentry, T.J.; et al. Responses of Microbial Community Functional Structures to Pilot-Scale Uranium in Situ Bioremediation. ISME J. 2010, 4, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.M.; Carley, J.; Luo, J.; Ginder-Vogel, M.A.; Cardenas, E.; Leigh, M.B.; Hwang, C.; Kelly, S.D.; Ruan, C.; Wu, L.; et al. In Situ Bioreduction of Uranium (VI) to Submicromolar Levels and Reoxidation by Dissolved Oxygen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 5716–5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wufuer, R.; Duo, J.; Li, W.; Fan, J.; Pan, X. Bioremediation of Uranium-and Nitrate-Contaminated Groundwater after the in Situ Leach Mining of Uranium. Water 2021, 13, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskova, O.L.; Boguslavsky, A.E.; Shemelina, O.V. Uranium Release from Contaminated Sludge Materials and Uptake by Subsurface Sediments: Experimental Study and Thermodynamic Modeling. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 55, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskova, O.L.; Boguslavsky, A.E. Groundwater Geochemistry Near the Storage Sites of Low-Level Radioactive Waste: Implications for Uranium Migration. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2013, 7, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artemyev, G.D.; Safonov, A.V.; Zubkov, A.A.; Myasnikov, I.Y.; Novikov, A.P. Experience of Creating an in Situ Biogeochemical Barrier in Contaminated Groundwater at Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities. Part 1. At. Energy 2025, 137, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safonov, A.V.; Babich, T.L.; Sokolova, D.S.; Grouzdev, D.S.; Tourova, T.P.; Poltaraus, A.B.; Zakharova, E.V.; Merkel, A.Y.; Novikov, A.P.; Nazina, T.N. Microbial Community and in Situ Bioremediation of Groundwater by Nitrate Removal in the Zone of a Radioactive Waste Surface Repository. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, T.L.; Popova, N.M.; Sokolova, D.S.; Perepelov, A.V.; Safonov, A.V.; Nazina, T.N. Microbial and Monosaccharide Composition of Biofilms Developing on Sandy Loams from an Aquifer Contaminated with Liquid Radioactive Waste. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litti, Y.; Elcheninov, A.; Botchkova, E.; Chernyh, N.; Merkel, A.; Vishnyakova, A.; Popova, N.; Zhang, Y.; Safonov, A. Metagenomic Evidence of a Novel Anammox Community in a Cold Aquifer with High Nitrogen Pollution. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Tomita, J.; Nishioka, K.; Hisada, T.; Nishijima, M. Development of a Prokaryotic Universal Primer for Simultaneous Analysis of Bacteria and Archaea Using Next-Generation Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadrosh, D.W.; Ma, B.; Gajer, P.; Sengamalay, N.; Ott, S.; Brotman, R.M.; Ravel, J. An Improved Dual-Indexing Approach for Multiplexed 16S RRNA Gene Sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq Platform. Microbiome 2014, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slobodkin, A.I.; Rusanov, I.I.; Slobodkina, G.B.; Stroeva, A.R.; Chernyh, N.A.; Pimenov, N.V.; Merkel, A.Y. Diversity, Methane Oxidation Activity, and Metabolic Potential of Microbial Communities in Terrestrial Mud Volcanos of the Taman Peninsula. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Lian, C.A.; Lin, B.; Chen, J.; Mu, R.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; Fan, L.; et al. BASALT Refines Binning from Metagenomic Data and Increases Resolution of Genome-Resolved Metagenomic Analysis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Tran, P.Q.; Breister, A.M.; Liu, Y.; Kieft, K.; Cowley, E.S.; Karaoz, U.; Anantharaman, K. METABOLIC: High-Throughput Profiling of Microbial Genomes for Functional Traits, Metabolism, Biogeochemistry, and Community-Scale Functional Networks. Microbiome 2022, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet. J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renaud, G.; Stenzel, U.; Maricic, T.; Wiebe, V.; Kelso, J. DeML: Robust Demultiplexing of Illumina Sequences Using a Likelihood-Based Approach. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 770–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botchkova, E.; Vishnyakova, A.; Popova, N.; Sukhacheva, M.; Kolganova, T.; Litti, Y.; Safonov, A. Characterization of Enrichment Cultures of Anammox, Nitrifying and Denitrifying Bacteria Obtained from a Cold, Heavily Nitrogen-Polluted Aquifer. Biology 2023, 12, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, S.; Haque, M.M.; Singh, R.; Mande, S.S. IVikodak-A Platform and Standard Workflow for Inferring, Analyzing, Comparing, and Visualizing the Functional Potential of Microbial Communities. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, T.; Liu, Y.X.; Huang, L. Visualizing Set Relationships: EVenn’s Comprehensive Approach to Venn Diagrams. iMeta 2024, 3, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, W.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Tan, Z.; Li, X. Impact Resistance of Different Factors on Ammonia Removal by Heterotrophic Nitrification-Aerobic Denitrification Bacterium aeromonas Sp. HN-02. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 167, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kwon, J.S.; Kwon, M.J. Multi-Approach Assessment of Groundwater Biogeochemistry: Implications for the Site Characterization of Prospective Spent Nuclear Fuel Repository Sites. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebler, C.; Lueders, T. Microbial Biodiversity in Groundwater Ecosystems. Freshw. Biol. 2009, 54, 649–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmonier, P.; Galassi, D.M.P.; Korbel, K.; Close, M.; Datry, T.; Karwautz, C. Groundwater Biodiversity and Constraints to Biological Distribution. In Groundwater Ecology and Evolution; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ihara, H.; Hori, T.; Aoyagi, T.; Hosono, H.; Takasaki, M.; Katayama, Y. Stratification of Sulfur Species and Microbial Community in Launched Marine Sediment by an Improved Sulfur-Fractionation Method and 16S RRNA Gene Sequencing. Microbes Environ. 2019, 34, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzsch, P.; Poehlein, A.; Johnson, D.B.; Daniel, R.; Schlömann, M.; Mühling, M. Genome Sequence of the Moderately Acidophilic Sulfate-Reducing Firmicute Desulfosporosinus Acididurans (Strain M1T). Genome Announc. 2015, 3, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, K.B.; Hedrich, S.; Johnson, D.B. Acidiferrobacter Thiooxydans, Gen. Nov. Sp. Nov.; an Acidophilic, Thermo-Tolerant, Facultatively Anaerobic Iron- and Sulfur-Oxidizer of the Family Ectothiorhodospiraceae. Extremophiles 2011, 15, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Xue, Q.; Zuo, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, M.; Kumar, S.; Li, W.; et al. Aliidiomarina Halalkaliphila Sp. Nov., a Haloalkaliphilic Bacterium Isolated from a Soda Lake in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, G.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Duan, P. Study on Enhancement of Denitrification Performance of Alcaligenes Faecalis. Separations 2023, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Kupper, R.J.; Catalano, J.G.; Thompson, A.; Chan, C.S. Biological Oxidation of Fe(II)-Bearing Smectite by Microaerophilic Iron Oxidizer Sideroxydans Lithotrophicus Using Dual Mto and Cyc2 Iron Oxidation Pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 17443–17453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabisch, M.; Beulig, F.; Akob, D.M.; Küsel, K. Surprising Abundance of Gallionella-Related Iron Oxidizers in Creek Sediments at PH 4.4 or at High Heavy Metal Concentrations. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D.R. Microbe Profile: Geobacter Metallireducens: A Model for Novel Physiologies of Biogeochemical and Technological Significance. Microbiology 2022, 168, 001138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, A.; Garrido-Chamorro, S.; Coque, J.J.R.; Barreiro, C. From Genes to Bioleaching: Unraveling Sulfur Metabolism in Acidithiobacillus Genus. Genes 2023, 14, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xu, S.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, N.; Zhuang, G.; Bai, Z.; Zhuang, X. Impacts of Human Activities on the Composition and Abundance of Sulfate-Reducing and Sulfur-Oxidizing Microorganisms in Polluted River Sediments. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Perner, M. The Globally Widespread Genus Sulfurimonas: Versatile Energy Metabolisms and Adaptations to Redox Clines. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadnikov, V.V.; Ivasenko, D.A.; Beletskii, A.V.; Mardanov, A.V.; Danilova, E.V.; Pimenov, N.V.; Karnachuk, O.V.; Ravin, N.V. A Novel Uncultured Bacterium of the Family Gallionellaceae: Description and Genome Reconstruction Based on Metagenomic Analysis of Microbial Community in Acid Mine Drainage. Microbiology 2016, 85, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; van Loosdrecht, M.; Gu, J.D.; Yang, Y. The Core Anammox Redox Reaction System of 12 Anammox Bacterial Genera and Their Evolution and Application Implications. Water Res. 2025, 281, 123551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araú, L.R.; de Deus Barbosa, A.E.A. Identification of Bacterial Species with Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Sulfur Bioremediation Pathways in Wastewater Treatment Plants. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, D.; Cao, W.; Borthwick, A.G.L. Multiple Pathways of Vanadate Reduction and Denitrification Mediated by Denitrifying Bacterium acidovorax Sp. Strain BoFeN1. Water Res. 2024, 257, 121747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Kümmel, S.; Richnow, H.H.; Nijenhuis, I.; Vogt, C. Heterotrophic Nitrate Reduction Potential of an Aquifer Microbial Community from Psychrophilic to Thermophilic Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 967, 178716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; He, J.; Zou, H.; Zhang, J.; Deng, L.; Yang, M.; Liu, F. Different Responses of Representative Denitrifying Bacterial Strains to Gatifloxacin Exposure in Simulated Groundwater Denitrification Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 157929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylen, K.; Gevers, D.; Vanparys, B.; Wittebolle, L.; Geets, J.; Boon, N.; De Vos, P. The Incidence of NirS and NirK and Their Genetic Heterogeneity in Cultivated Denitrifiers. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 2012–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayangbenro, A.S.; Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O. Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria as an Effective Tool for Sustainable Acid Mine Bioremediation. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Palomo, A.; Zhou, J.; Smets, B.F.; Bürgmann, H.; Ju, F. Pathogenic and Indigenous Denitrifying Bacteria are Transcriptionally Active and Key Multi-Antibiotic-Resistant Players in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 10862–10874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hanke, A.; Tegetmeyer, H.E.; Kattelmann, I.; Sharma, R.; Hamann, E.; Hargesheimer, T.; Kraft, B.; Lenk, S.; Geelhoed, J.S.; et al. Impacts of Chemical Gradients on Microbial Community Structure. ISME J. 2017, 11, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Xu, X.; Jia, D.; Lyu, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, Q.; Sun, W. Sediments Alleviate the Inhibition Effects of Antibiotics on Denitrification: Functional Gene, Microbial Community, and Antibiotic Resistance Gene Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Uenishi, H.; Uchihashi, Y.; Hiraishi, A.; Yukawa, H.; Yurimoto, H.; Kato, N. Aerobic and Anaerobic Toluene Degradation by a Newly Isolated Denitrifying Bacterium, Thauera Sp. Strain DNT-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Hosono, T.; Ohta, H.; Niidome, T.; Shimada, J.; Morimura, S. Comparison of Microbial Communities inside and Outside of a Denitrification Hotspot in Confined Groundwater. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 114, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.T.; Puckett, L.J.; Böhlke, J.K.; Bekins, B.A.; Phillips, S.P.; Kauffman, L.J.; Denver, J.M.; Johnson, H.M. Limited Occurrence of Denitrification in Four Shallow Aquifers in Agricultural Areas of the United States. J. Environ. Qual. 2008, 37, 994–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utom, A.U.; Werban, U.; Leven, C.; Müller, C.; Knöller, K.; Vogt, C.; Dietrich, P. Groundwater Nitrification and Denitrification Are Not Always Strictly Aerobic and Anaerobic Processes, Respectively: An Assessment of Dual-Nitrate Isotopic and Chemical Evidence in a Stratified Alluvial Aquifer. Biogeochemistry 2020, 147, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.J.; Zhang, T.; Hu, L.K.; Liu, S.Y.; Li, C.C.; Jin, Y.S.; Liu, H. Bin Denitrification Characteristics of the Low-Temperature Tolerant Denitrification Strain Achromobacter Spiritinus HS2 and Its Application. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finneran, K.T.; Johnsen, C.V.; Lovley, D.R. Rhodoferax ferrireducens Sp. Nov., a Psychrotolerant, Facultatively Anaerobic Bacterium That Oxidizes Acetate with the Reduction of Fe(III). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Duan, H.; Dong, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S.; Xu, T.; Guo, B. Improved Effects of Combined Application of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria Azotobacter Beijerinckii and Microalgae Chlorella Pyrenoidosa on Wheat Growth and Saline-Alkali Soil Quality. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, C.B.; Kumar, U.; Kaviraj, M.; Minick, K.J.; Mishra, A.K.; Singh, J.S. DNRA: A Short-Circuit in Biological N-Cycling to Conserve Nitrogen in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 139710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Kumari, A.; Devi, S.; Saini, P. Effect of N2-Fixing Non-Frankia Actinomycete Inoculum on the Growth and Nodulation Status of Elaeagnus Umbellata Thunb. Ecol. Front. 2025, 45, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.; Kratz, A.M.; Weber, J.; Prass, M.; Liu, F.; Clark, A.T.; Abed, R.M.M.; Su, H.; Cheng, Y.; Eickhorst, T.; et al. Water-Driven Microbial Nitrogen Transformations in Biological Soil Crusts Causing Atmospheric Nitrous Acid and Nitric Oxide Emissions. ISME J. 2022, 16, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.C.; Han, Z.Z.; Ruan, X.Y.; Chai, J.; Jiang, S.W.; Zheng, R. Composting Swine Carcasses with Nitrogen Transformation Microbial Strains: Succession of Microbial Community and Nitrogen Functional Genes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 688, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Chen, Y.; Qu, J.; Jin, P.; Zheng, Z.; Cui, Z. Insights into the Variations of Hao-Dependent Nitrifying and Nir-Dependent Denitrifying Microbial Communities in Ammonium-Graduated Lake Environments. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontalvo, N.P.M.; Gamero, W.B.M.; Ardila, H.A.M.; Gonzalez, A.F.P.; Ramos, C.G.; Muñoz, A.E.P. Removal of Nitrogenous Compounds from Municipal Wastewater Using a Bacterial Consortium: An Opportunity for More Sustainable Water Treatments. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Ö.; Atasoy, A.D.; Çalış, B.; Çakmak, Y.; Di Capua, F.; Sahinkaya, E.; Uçar, D. Impact of Temperature and Biomass Augmentation on Biosulfur-Driven Autotrophic Denitrification in Membrane Bioreactors Treating Real Nitrate-Contaminated Groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.; Chi, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Li, R.; Chu, S.; Yang, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P. A Sustainable Approach for Bioremediation of Secondary Salinized Soils: Studying Remediation Efficiency and Soil Nitrate Transformation by Bioaugmentation. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellini, M.I.; Gutiérrez, L.; Tarlera, S.; Scavino, A.F. Isolation and Functional Analysis of Denitrifiers in an Aquifer with High Potential for Denitrification. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 36, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Graf, D.R.H.; Bru, D.; Philippot, L.; Hallin, S. The Unaccounted yet Abundant Nitrous Oxide-Reducing Microbial Community: A Potential Nitrous Oxide Sink. ISME J. 2013, 7, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L. Denitrifying Genes in Bacterial and Archaeal Genomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Gene Struct. Expr. 2002, 1577, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, E.; Zhang, K.; Gong, W.; Xia, Y.; Tian, J.; Wang, G.; Xie, J. Water Treatment Effect, Microbial Community Structure, and Metabolic Characteristics in a Field-Scale Aquaculture Wastewater Treatment System. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, T.L.; Safonov, A.V.; Grouzdev, D.S.; Andryuschenko, N.D.; Zakharova, E.V.; Nazina, T.N. Bacteria of the Genus Shewanella from Radionuclide-Contaminated Groundwater. Microbiology 2019, 88, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muter, O. Current Trends in Bioaugmentation Tools for Bioremediation: A Critical Review of Advances and Knowledge Gaps. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishnyakova, A.; Popova, N.; Artemiev, G.; Botchkova, E.; Litti, Y.; Safonov, A. Effect of Mineral Carriers on Biofilm Formation and Nitrogen Removal Activity by an Indigenous Anammox Community from Cold Groundwater Ecosystem Alone and Bioaugmented with Biomass from a “Warm” Anammox Reactor. Biology 2022, 11, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Label | Site | Pollution Level | Depth, m |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1B | 1. Radioactive Waste Storage Basin “B2”, Siberian Chemical Combine (Seversk, Krasnoyarsk Krai) | Background | 15 |

| 1M | Medium | 15 | |

| 1H | High | 15 | |

| 2B | 2. Slurry Reservoir, Chepetsk Mechanical Plant (Glazov, Udmurt Republic) | Background | 11 |

| 2M | Medium | 11 | |

| 2H | High | 11 | |

| 3B | 3. Slurry Reservoir, Angarsk Electrolysis Chemical Combine (Angarsk, Irkutsk Region) | Background | 9 |

| 3M | Medium | 9 | |

| 3H | High | 9 | |

| 4B | 4. Slurry Reservoir, Electrolysis Chemical Combine (Zelenogorsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai) | Background | 12 |

| 4M | Medium | 12 | |

| 4H | High | 12 | |

| 5B | 5. Slurry Reservoir, Novosibirsk Chemical Concentrates Plant (Novosibirsk, Novosibirsk Region) | Background | 15 |

| 5M | Medium | 15 | |

| 5H | High | 15 | |

| 6B | 6. Slurry Reservoir, Sublimate Plant (Seversk, Krasnoyarsk Krai) | Background | 20 |

| 6M | Medium | 20 | |

| 6H | High | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popova, N.; Safonov, A. Diversity of Groundwater Microbial Communities near Sludge Repositories with Different Types and Levels of Pollution. Life 2025, 15, 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121854

Popova N, Safonov A. Diversity of Groundwater Microbial Communities near Sludge Repositories with Different Types and Levels of Pollution. Life. 2025; 15(12):1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121854

Chicago/Turabian StylePopova, Nadezhda, and Alexey Safonov. 2025. "Diversity of Groundwater Microbial Communities near Sludge Repositories with Different Types and Levels of Pollution" Life 15, no. 12: 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121854

APA StylePopova, N., & Safonov, A. (2025). Diversity of Groundwater Microbial Communities near Sludge Repositories with Different Types and Levels of Pollution. Life, 15(12), 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121854