Urinary KIM-1 for Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury in Neonates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

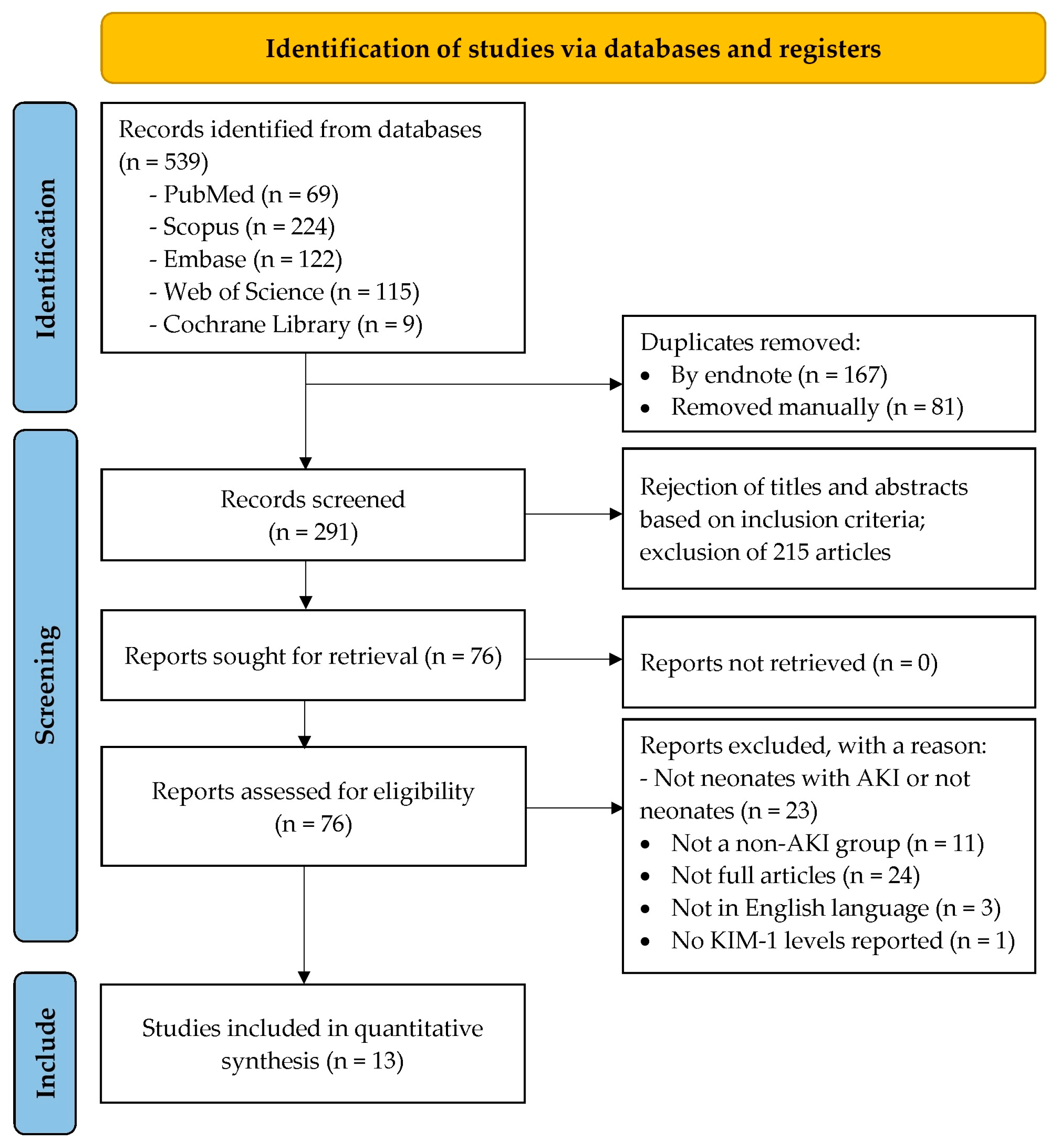

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment and Certainty of Evidence Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Results of Quality Assessment and GRADE Assessment of Evidence

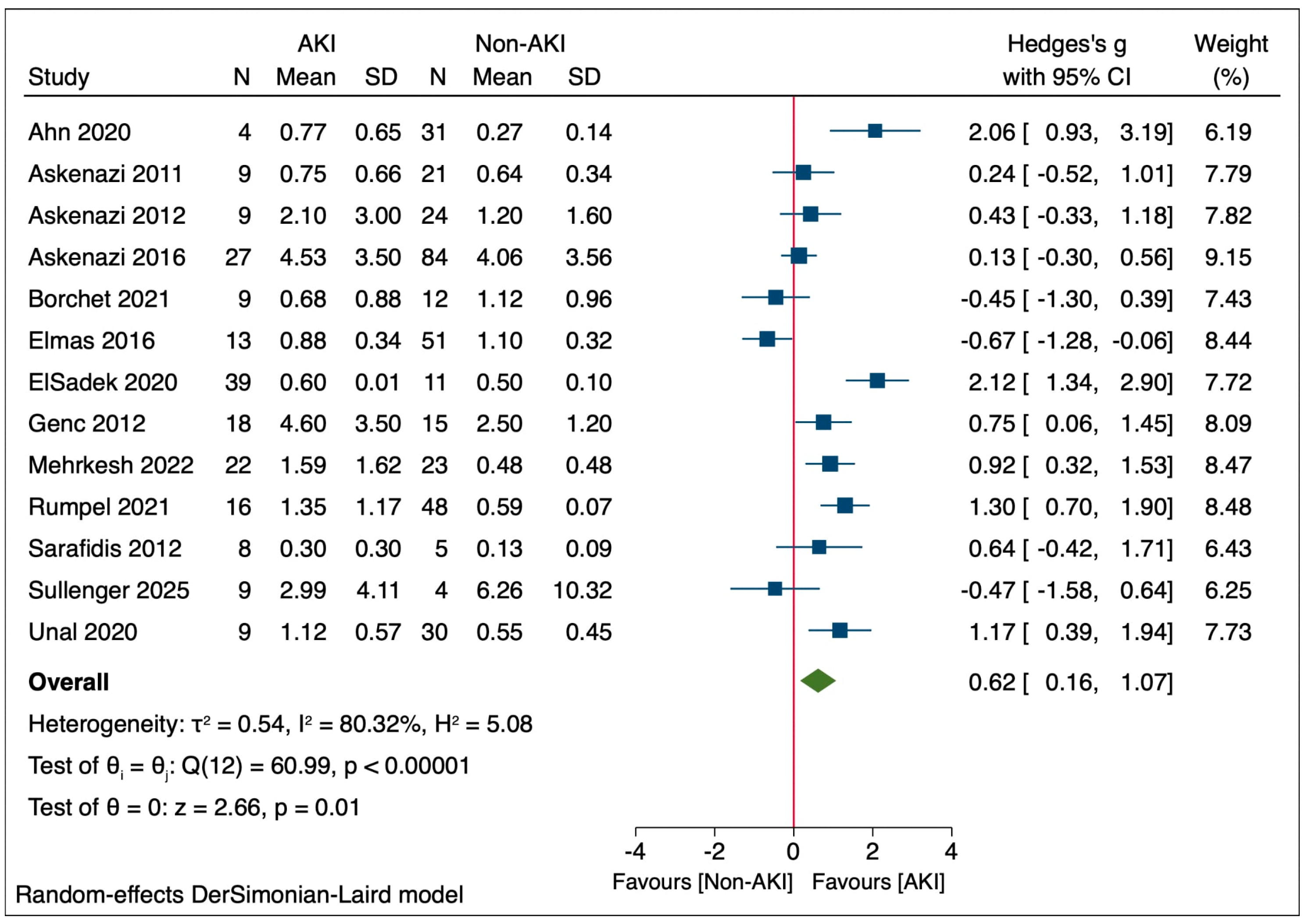

3.4. uKIM-1 Levels in Neonatal AKI

3.5. Subgroup Analysis

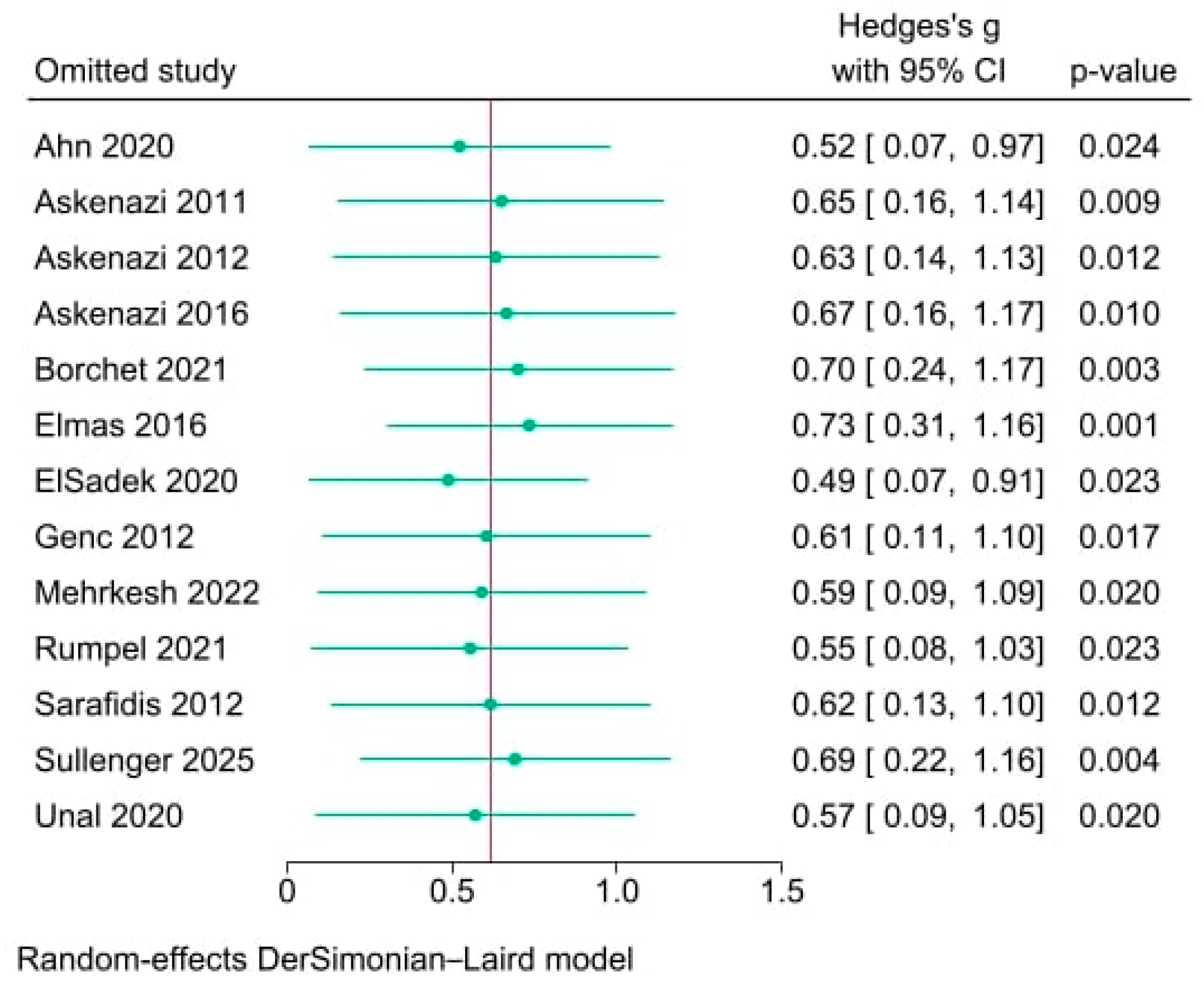

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

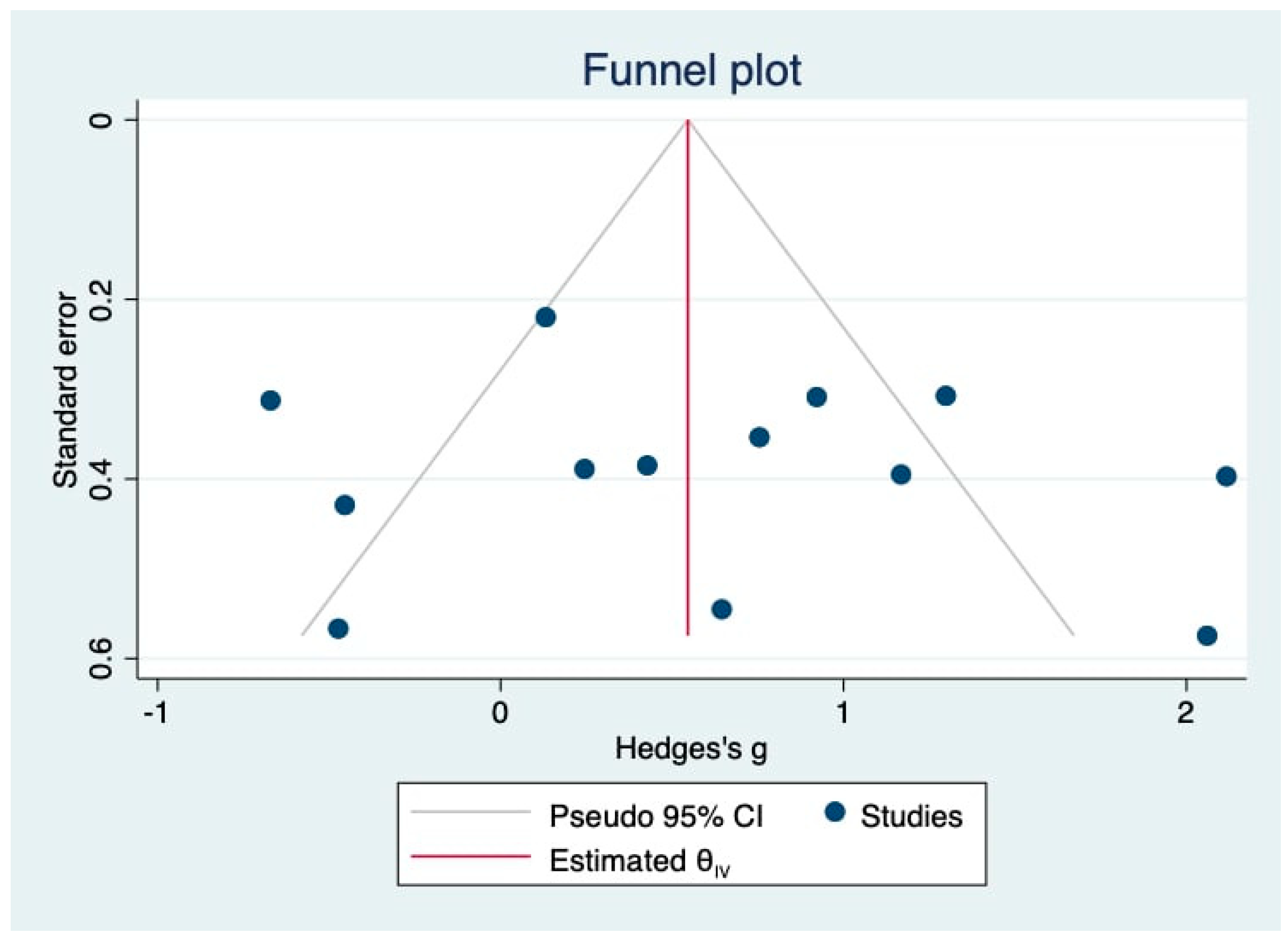

3.7. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| AKIN | Acute kidney injury network |

| ApoM | Apolipoprotein M |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CS | Cardiac surgery |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| GDF-15 | Growth differentiation factor 15 |

| IGFBP7 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| KIM-1 | Kidney injury molecule-1 |

| L-FABP | Liver-type fatty acid binding protein |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MMP-7 | Matrix metalloproteinase-7 |

| NGAL | Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| nKDIGO | Modified neonatal kidney disease: improving global outcomes |

| NR | Not reported |

| nRIFLE | Neonatal: risk, injury, failure, loss of kidney function, and end-stage kidney disease |

| RDS | Respiratory distress syndrome |

| uKIM-1 | Urinary kidney injury molecule-1 |

| UMOD | Uromodulin |

References

- Coleman, C.; Tambay Perez, A.; Selewski, D.T.; Steflik, H.J. Neonatal acute kidney injury. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 842544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, T.; Asdell, N.; Ning, X.; Newland, J.G.; Harer, M.W.; Slagle, C.L.; Starr, M.C.; Spencer, J.D.; Wilson, F.P.; Selewski, D.T.; et al. Evidence-based risk stratification for neonatal acute kidney injury: A call to action. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2025, 40, 3335–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, M.C.; Charlton, J.R.; Guillet, R.; Reidy, K.; Tipple, T.E.; Jetton, J.G.; Kent, A.L.; Abitbol, C.L.; Ambalavanan, N.; Mhanna, M.J.; et al. Advances in neonatal acute kidney injury. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021051220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.; Sity-Harel, S.; Benchetrit, S.; Reisman, L.; Zitman-Gal, T.; Erez, D.; Shehab, M.; Cohen-Hagai, K. Acute kidney injury in the neonatal period: Retrospective data and implications for clinical practice. Children 2025, 12, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, V.; Lacquaniti, A.; Tripodi, F.; Conti, G.; Marseglia, L.; Monardo, P.; Gitto, E.; Chimenz, R. Acute kidney injury in neonatal intensive care unit: Epidemiology, diagnosis and risk factors. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermann, M.; Legrand, M.; Meersch, M.; Srisawat, N.; Zarbock, A.; Kellum, J.A. Biomarkers in acute kidney injury. Ann. Intensive Care 2024, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.E.; Peterson, J.; Kim, J.J.; Mahaveer, A. How to know when little kidneys are in trouble: A review of current tools for diagnosing AKI in neonates. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1270200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorga, S.M.; Beck, T.; Chaudhry, P.; DeFreitas, M.J.; Fuhrman, D.Y.; Joseph, C.; Krawczeski, C.D.; Kwiatkowski, D.M.; Starr, M.C.; Harer, M.W.; et al. Framework for kidney health follow-up among neonates with critical cardiac disease: A report from the neonatal kidney health consensus workshop. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e040630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branagan, A.; Costigan, C.S.; Stack, M.; Slagle, C.; Molloy, E.J. Management of acute kidney injury in extremely low birth weight infants. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 867715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Kumar, D.; Vijayaraghavan, P.; Chaturvedi, T.; Raina, R. Non-dialytic management of acute kidney injury in newborns. J. Ren. Inj. Prev. 2017, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y. Advances in the diagnosis of early biomarkers for acute kidney injury: A literature review. BMC Nephrol. 2025, 26, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris, M.E.; Filler, G. Still trouble with serum creatinine measurements. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 37, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohiya, P.; Nadkarni, J.; Mishra, M. Study of neonatal acute kidney injury based on KDIGO criteria. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2022, 63, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdziechowska, M.; Gluba-Brzózka, A.; Poliwczak, A.R.; Franczyk, B.; Kidawa, M.; Zielinska, M.; Rysz, J. Serum NGAL, KIM-1, IL-18, L-FABP: New biomarkers in the diagnostics of acute kidney injury (AKI) following invasive cardiology procedures. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2020, 52, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadzimuratovic, E.; Skrablin, S.; Hadzimuratovic, A.; Dinarevic, S.M. Postasphyxial renal injury in newborns as a prognostic factor of neurological outcome. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014, 27, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, H.; Horino, T.; Osakabe, Y.; Inotani, S.; Yoshida, K.; Mitani, K.; Hatakeyama, Y.; Miura, Y.; Terada, Y.; Kawano, T. Urinary [TIMP-2]•[IGFBP7], TIMP-2, IGFBP7, NGAL, and L-FABP for the prediction of acute kidney injury following cardiovascular surgery in Japanese patients. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2025, 29, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inotani, S.; Kashio, T.; Osakabe, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Nagao, Y.; Ishihara, M.; Iwata, H.; Mitani, K.; Hatakeyama, Y.; Horino, T. Efficacy of urinary [TIMP-2]⋅[IGFBP7], L-FABP, and NGAL levels for predicting community-acquired acute kidney injury in Japanese patients: A single-center, prospective cohort study. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2025, 29, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanamatsu, A.; de Araújo, L.; LaFavers, K.A.; El-Achkar, T.M. Advances in uromodulin biology and potential clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frances, L.; Croyal, M.; Ruidavets, J.-B.; Maraninchi, M.; Combes, G.; Raffin, J.; de Souto Barreto, P.; Ferrières, J.; Blaak, E.E.; Perret, B.; et al. Identification of circulating apolipoprotein M as a new determinant of insulin sensitivity and relationship with adiponectin. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avello, A.; Guerrero-Mauvecin, J.; Sanz, A.B. Urine MMP7 as a kidney injury biomarker. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfad233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, G.; Wazir, S.; Sethi, S.K.; Tibrewal, A.; Dhir, R.; Bajaj, N.; Gupta, N.P.; Mirgunde, S.; Sahoo, J.; Balachandran, B.; et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of neonatal acute kidney injury: Protocol of a multicentric prospective cohort study [the Indian iconic neonatal kidney educational egistry]. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 690559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-L.; Chen, H.-L.; Hsu, B.-G.; Yang, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-C.; Tsai, I.L.; Sung, C.-C.; Wu, C.-C.; Yang, S.-R.; et al. Galectin-3 contributes to pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2024, 106, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Day, E.A.; Townsend, L.K.; Djordjevic, D.; Jørgensen, S.B.; Steinberg, G.R. GDF15: Emerging biology and therapeutic applications for obesity and cardiometabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 592–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, B.; Pang, B.; Zhou, Z.; Xing, Y.; Pang, P.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, G.; Yang, B. Exploring the relations of NLR, hsCRP and MCP-1 with type 2 diabetic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Cheuk, Y.C.; Jia, Y.; Chen, T.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Cao, Y.; Guo, J.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal miR-21a-5p alleviates renal fibrosis by attenuating glycolysis by targeting PFKM. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brilland, B.; Boud’hors, C.; Wacrenier, S.; Blanchard, S.; Cayon, J.; Blanchet, O.; Piccoli, G.B.; Henry, N.; Djema, A.; Coindre, J.-P.; et al. Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1): A potential biomarker of acute kidney injury and tubulointerstitial injury in patients with ANCA-glomerulonephritis. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 1521–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, S.; Nabiel, A.; Mohamed, M.M.; Hassan, R. Is urinary kim-1 a better biomarker than its serum value in diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury disease? Med. Update 2020, 1, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.; Luo, Z.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, Q. Kim-1-targeted multimodal nanoprobes for early diagnosis and monitoring of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Apoptosis 2025, 30, 2316–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpel, J.; Spray, B.J.; Chock, V.Y.; Kirkley, M.J.; Slagle, C.L.; Frymoyer, A.; Cho, S.H.; Gist, K.M.; Blaszak, R.; Poindexter, B.; et al. Urine biomarkers for the assessment of acute kidney injury in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy receiving therapeutic hypothermia. J. Pediatr. 2022, 241, 133–140.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSadek, A.E.; El gafar, E.A.; Behiry, E.G.; Nazem, S.A.; Abdel Haie, O.M. Kidney injury molecule-1/creatinine as a urinary biomarker of acute kidney injury in critically ill neonates. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2020, 16, e681–e688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Fan, Q.; Wang, L.; Shrestha, N.; Thapa, S. Urinary NGAL and KIM-1 are the early detecting biomarkers of preterm infants with acute kidney injury. Yangtze Med. 2019, 03, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, V.D.; Barišić, N.A.; Vučković, N.M.; Doronjski, A.D.; Peco Antić, A.E. Urinary kidney injury molecule-1 rapid test predicts acute kidney injury in extremely low-birth-weight neonates. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 78, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Sarveazad, A.; Mohamed Ali, K.; Yousefifard, M.; Hosseini, M. Accuracy of urine kidney injury molecule-1 in predicting acute kidney injury in children; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 8, e44. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Yang, X.; Cheng, W.-W.; Shang, X.-M.; Wang, H.-L.; Shen, H.-C. Kidney injury molecule 1 in the early detection of acute kidney injury—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1574945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarneh, A.; Akkari, A.; Sardar, S.; Salameh, O.; Dauleh, M.; Matarneh, B.; Abdulbasit, M.; Miller, R.; Verma, N.; Ghahramani, N. Beyond creatinine: Diagnostic accuracy of emerging biomarkers for AKI in the ICU—A systematic review. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2556295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, D.; Khan, M. Writing a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide. Sports Health 2025, 17, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carra, M.C.; Romandini, P.; Romandini, M. Risk of bias evaluation of cross-sectional studies: Adaptation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. J. Periodontal Res. 2025, Early View. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M. Introduction to the GRADE tool for rating certainty in evidence and recommendations. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 25, 101484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wan, X.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018, 27, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.F.; Dexter, F. Estimating sample means and standard deviations from the log-normal distribution using medians and quartiles: Evaluating reporting requirements for primary and secondary endpoints of meta-analyses in anesthesiology. Can. J. Anaesth. 2025, 72, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba, A.C.; Alexander, P.E.; Chang, J.; MacIsaac, J.; DeFry, S.; Guyatt, G.H. High statistical heterogeneity is more frequent in meta-analysis of continuous than binary outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 70, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Wang, J.; Lin, L.; Wu, C. Sensitivity analysis with iterative outlier detection for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Stat. Med. 2024, 43, 1549–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.H.; Lee, J.; Chun, J.; Jun, Y.H.; Sung, T.J. Urine biomarkers for monitoring acute kidney injury in premature infants. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askenazi, D.J.; Montesanti, A.; Hundley, H.; Koralkar, R.; Pawar, P.; Shuaib, F.; Liwo, A.; Devarajan, P.; Ambalavanan, N. Urine biomarkers predict acute kidney injury and mortality in very low birth weight infants. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 907–912.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askenazi, D.J.; Koralkar, R.; Hundley, H.E.; Montesanti, A.; Parwar, P.; Sonjara, S.; Ambalavanan, N. Urine biomarkers predict acute kidney injury in newborns. J. Pediatr. 2012, 161, 270–275.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askenazi, D.J.; Koralkar, R.; Patil, N.; Halloran, B.; Ambalavanan, N.; Griffin, R. Acute kidney injury urine biomarkers in very low-birth-weight infants. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchert, E.; de la Fuente, R.; Guzmán, A.M.; González, K.; Rolle, A.; Morales, K.; González, R.; Jalil, R.; Lema, G. Biomarkers as predictors of renal damage in neonates undergoing cardiac surgery. Perfusion 2021, 36, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmas, A.T.; Karadag, A.; Tabel, Y.; Ozdemir, R.; Otlu, G. Analysis of urine biomarkers for early determination of acute kidney injury in non-septic and non-asphyxiated critically ill preterm neonates. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 30, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genc, G.; Ozkaya, O.; Avci, B.; Aygun, C.; Kucukoduk, S. Kidney injury molecule-1 as a promising biomarker for acute kidney injury in premature babies. Am. J. Perinatol. 2013, 30, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrkesh, M.; Barekatain, B.; Gheisari, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Shahsanai, A. Serum KIM-1 and cystatin levels as the predictors of acute kidney injury in asphyxiated neonates. Iran. J. Neonatol. 2022, 13, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sarafidis, K.; Tsepkentzi, E.; Agakidou, E.; Diamanti, E.; Taparkou, A.; Soubasi, V.; Papachristou, F.; Drossou, V. Serum and urine acute kidney injury biomarkers in asphyxiated neonates. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2012, 27, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullenger, R.D.; Kilborn, A.G.; Chamberlain, R.C.; Hill, K.D.; Gbadegesin, R.A.; Hornik, C.P.; Thompson, E.J. Urine biomarkers, acute kidney injury, and fluid overload in neonatal cardiac surgery. Cardiol. Young 2025, 35, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, E.T.; Ozer, E.A.; Kahramaner, Z.; Erdemir, A.; Cosar, H.; Sutcuoglu, S. Value of urinary kidney injury molecule-1 levels in predicting acute kidney injury in very low birth weight preterm infants. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 0300060520977442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, A.M.; Johnston, C.J.; Beutner, G.G.; Dahlstrom, J.E.; Koina, M.; O’Reilly, M.A.; Porter, G.; Brophy, P.D.; Kent, A.L. Neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy increases acute kidney injury urinary biomarkers in a rat model. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Su, B. The value of kidney injury molecule 1 in predicting acute kidney injury in adult patients: A systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.; Tian, L.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Qi, C.; Ni, Z.; Mou, S. Diagnostic value of urinary kidney injury molecule 1 for acute kidney injury: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, K.; Al Jufairi, M.; Al Segai, O.; Al Ansari, E.; Hashem Ahmed, H.; Husain Shaban, G.; Malalla, Z.; Al Marzooq, R.; Al Madhoob, A.; Saeed Tabbara, K. Biomarkers in neonates receiving potential nephrotoxic drugs. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 7078–7088. [Google Scholar]

- Er, E.; Ulusal Okyay, G.; Aygencel, G.; Lu, M.; Erten, Y. Comparison between RIFLE, AKIN, and KDIGO: Acute kidney injury definition criteria for prediction of in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 14, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Strauß, C.; Booke, H.; Forni, L.; Zarbock, A. Biomarkers of acute kidney injury: From discovery to the future of clinical practice. J. Clin. Anesth. 2024, 95, 111458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Shen, W.; Ning, J.; Feng, Z.; Hu, J. Addressing patient heterogeneity in disease predictive model development. Biometrics 2022, 78, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, R.; Schirinzi, A.; Baldassarre, M.E.; Caravita, R.; Laterza, R.; Mascolo, E.; Malerba, F.; Di Serio, F.; Laforgia, N. Evaluation of uNGAL and TIMP-2*IGFBP7 as early biomarkers of Acute Kidney Injury in Caucasian term and preterm neonates: A prospective observational cohort study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2025, 51, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virzì, G.M.; Morisi, N.; Oliveira Paulo, C.; Clementi, A.; Ronco, C.; Zanella, M. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: Biological aspects and potential diagnostic use in acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, N.; Seirafianpour, F.; Mashaiekhi, M.; Safari, S.; Khalesi, N.; Otukesh, H.; Hoseini, R. Importance of urinary NGAL relative to serum creatinine level for predicting acute neonatal kidney injury. Iran. J. Neonatol. 2020, 11, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barbati, A.; Aisa, M.C.; Cappuccini, B.; Zamarra, M.; Gerli, S.; Di Renzo, G.C. Urinary cystatin-C, a marker to assess and monitor neonatal kidney maturation and function: Validation in twins. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, N.J.L.; Bökenkamp, A.; Grubb, A.; de Wildt, S.N.; Schreuder, M.F. Cystatin C as a marker for glomerular filtration rate in critically ill neonates and children: Validation against iohexol plasma clearance. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 1672–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Country (Continent) | Study Design | Gestational Ages (Weeks) | Sampling Time | Conditions | Setting | %Male (AKI, Non-AKI) | AKI Definition | AKI (n) | Non-AKI (n) | Assay | Value of uKIM-1 | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al., 2020 [45] | Republic of Korea (Asia) | Prospective cohort | 28–32 | The first 7 days of life | Premature infants | NICU | 50, 55 | nKDIGO | 4 | 32 | Multiplex Luminex assay® (ELISA) | Mean ± SD | KIM-1/Cr (ng/mg) |

| Askenazi et al., 2011 [46] | USA (South America) | Nested case–control | <32 | The first 6 days of life | Very low birth weight infants | NICU | 44.4, 47.6 | AKIN | 9 | 21 | Prototype duplex (2-plex) assays (ELISA) | Median (IQR) | pg/mL |

| Askenazi et al., 2012 [47] | USA (South America) | Nested case–control | >34 | The first 4 days of life | Birth weight >2000 g | NICU | 89, 38 | AKIN | 9 | 24 | Meso Scale Discovery Human KIM-1 Assay Kit (ELISA) | Mean (95% CI) | ng/mL |

| Askenazi et al., 2016 [48] | USA (South America) | Prospective cohort | ≤31 | The first 4 days of life | Preterm infants (BW ≤ 1200 g) | NICU | 36, 53 | nKDIGO | 27 | 84 | Meso Scale Human Kidney Injury Panel 3 Kit Assay (ELISA) | Median (IQR) | pg/mL |

| Borchet et al., 2021 [49] | Chile (South America) | Descriptive (cohort study) | NR | After induction of anesthesia at 24 h | Neonates < 4 kilograms (kg), with complex congenital heart diseases | NR | 67, 50 | nRIFLE | 9 | 12 | Quantitative immunoassay (ELISA) | Median (IQR) | pg/mL |

| Elmas et al., 2016 [50] | Turkey (Asia) | Prospective case–control | 28–32 | The first 7 days of life | Non-septic and non-asphyxiated critically ill neonates | NICU | 54, 47 | AKIN | 13 | 51 | Human KIM-1 ELISA kit | Median (minimum-maximum) | ng/mL |

| ElSadek et al., 2020 [30] | Egypt (Africa) | Prospective case–control | 37–40 | 3 days after admission | Critically ill neonates | NICU | 62, 55 | nKDIGO | 39 | 11 | Human KIM-1 ELISA kit | Mean ± SD | ng/mL |

| Genc et al., 2012 [51] | Turkey (Asia) | Prospective cohort | <34 | The first 7 days of life | Premature infants with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) | NICU | 50, 66.7 | nKDIGO | 18 | 15 | ELISA | Mean ± SD | ng/mg creatinine |

| Mehrkesh et al., 2022 [52] | Iran (Asia) | Case–control | >34 | The first 4 days of life | Neonates with asphyxia | NICU | NR | nRIFLE | 22 | 23 | ELISA | Mean ± SD | KIM-1 Cr-standardized (ng/mL) |

| Rumpel et al., 2021 [29] | USA (North America) | Prospective cohort | ≥35 | The first 3 days of life | Neonates with hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy receiving therapeutic hypothermia | NICU | 63, 44 | nKDIGO | 16 | 48 | ELISA | Mean ± SD | pg/mL |

| Sarafidis et al., 2012 [53] | Greece (Europe) | Case–control | ≥36 | The first 10 days of life | Asphyxiated neonates | NICU | 75, 80 | nKDIGO | 8 | 5 | ELISA | Median (IQR) | pg/mL |

| Sullenger et al., 2025 [54] | USA (North America) | Prospective cohort | >37 | 8 to 24 h after separation from bypass | Neonates (≤28 days) undergoing cardiac surgery (CS), late postoperative | NR | NR | nKDIGO | 9 | 4 | ELISA | Median (IQR) | pg/mL |

| Unal et al., 2020 [55] | Turkey (Asia) | Prospective cohort | 25–32 | The first 2–3 days of life | Very low birth weight preterm infants | NICU | 55.6, 63.3 | nKDIGO | 9 | 30 | ELISA | Mean ± SD | pg/mL |

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Exposure/Outcome | Total Score (Out of 9) | Quality Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahn et al. (2020) [45] | 4/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 8 | High |

| Askenazi et al. (2011) [46] | 4/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 8 | High |

| Askenazi et al. (2012) [47] | 4/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 8 | High |

| Askenazi et al. (2016) [48] | 4/4 | 1/2 | 2/3 | 7 | High |

| Borchet et al. (2021) [49] | 3/4 | 1/2 | 2/3 | 6 | Moderate |

| Elmas et al. (2016) [50] | 3/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 7 | High |

| ElSadek et al. (2020) [30] | 3/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 7 | High |

| Genc et al. (2012) [51] | 3/4 | 1/2 | 2/3 | 6 | Moderate |

| Mehrkesh et al. (2022) [52] | 3/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 7 | High |

| Rumpel et al. (2021) [29] | 4/4 | 1/2 | 3/3 | 8 | High |

| Sarafidis et al. (2012) [53] | 4/4 | 1/2 | 3/3 | 8 | High |

| Sullenger et al. (2025) [54] | 4/4 | 1/2 | 3/3 | 8 | High |

| Unal et al. (2020) [55] | 4/4 | 1/2 | 3/3 | 8 | High |

| Subgroup Analyses | p-Value Between AKI vs. Non-AKI | Hedges’s g (95% CI) | I2 (%) | Number of Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continent (test of group difference, p-value < 0.0001) | |||||

| Africa | < 0.0001 | 2.12 (1.34, 2.90) | N/A | 1 | [30] |

| Asia | 0.065 | 0.79 (−0.05, 1.62) | 84.81 | 5 | [45,50,51,52,55] |

| Europe | 0.237 | 0.64 (−0.42, 1.71) | N/A | 1 | [53] |

| North America | 0.160 | 0.39 (−0.15, 0.93) | 68.17 | 5 | [29,46,47,48,54] |

| South America | 0.290 | −0.45 (−1.30, 0.39) | N/A | 1 | [49] |

| Study design (test of group difference, p-value = 0.95) | |||||

| Case–control | 0.128 | 0.60 (−0.17, 1.38) | 84.84 | 6 | [30,46,47,50,52,53] |

| Cohort | 0.038 | 0.63 (0.02, 1.23) | 78.54 | 7 | [29,45,48,49,51,54,55] |

| Sampling time (test of group difference, p-value = 0.86) | |||||

| The first 2–4 days of life | 0.002 | 0.76 (0.27, 1.26) | 68.21 | 5 | [29,47,48,52,55] |

| The first 6–10 days of life | 0.208 | 0.54 (−0.30, 1.37) | 81.05 | 5 | [45,46,50,51,53] |

| Others | 0.650 | 0.42 (−1.39, 2.22) | 91.73 | 3 | [30,49,54] |

| AKI definition (test of group difference, p-value = 0.10) | |||||

| AKIN | 0.933 | −0.03 (−0.74, 0.68) | 66.95 | 3 | [46,47,50] |

| nKDIGO | 0.001 | 0.96 (0.38, 1.54) | 79.21 | 8 | [29,30,45,48,51,53,54,55] |

| nRIFLE | 0.699 | 0.27 (−1.08, 1.61) | 85.24 | 2 | [49,52] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Praditaukrit, M.; Chatatikun, M.; Tedasen, A.; Praditaukrit, S.; Konwai, S.; Huang, J.C.; Klangbud, W.K.; Phongphithakchai, A. Urinary KIM-1 for Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury in Neonates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life 2025, 15, 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121842

Praditaukrit M, Chatatikun M, Tedasen A, Praditaukrit S, Konwai S, Huang JC, Klangbud WK, Phongphithakchai A. Urinary KIM-1 for Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury in Neonates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life. 2025; 15(12):1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121842

Chicago/Turabian StylePraditaukrit, Manapat, Moragot Chatatikun, Aman Tedasen, Suntornwit Praditaukrit, Sirihatai Konwai, Jason C. Huang, Wiyada Kwanhian Klangbud, and Atthaphong Phongphithakchai. 2025. "Urinary KIM-1 for Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury in Neonates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Life 15, no. 12: 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121842

APA StylePraditaukrit, M., Chatatikun, M., Tedasen, A., Praditaukrit, S., Konwai, S., Huang, J. C., Klangbud, W. K., & Phongphithakchai, A. (2025). Urinary KIM-1 for Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury in Neonates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life, 15(12), 1842. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121842