Abstract

Meningiomas represent the most common benign histological tumor of the central nervous system. Usually, meningiomas are intracranial, showing a typical dural tail sign on brain MRI with Gadolinium, but occasionally they can infiltrate the skull or be sited extracranially. We present a systematic review of the literature on extracranial meningiomas of the head and neck, along with an emblematic case of primary extracranial meningioma (PEM), which provides further insights into PEM management. A literature search according to the PRISMA statement was conducted from 1979 to June 2021 using PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases, searching for relevant Mesh terms (primary extracranial meningioma) AND (head OR neck). Data for all patients were recorded when available, including age, sex, localization, histological grading, treatment, possible recurrence, and outcome. A total of 83 published studies were identified through PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases, together with additional references list searches from 1979 to date. A total of 49 papers were excluded, and 34 manuscripts were considered for this systematic review, including 213 patients. We also reported a case of a 45-year-old male with an extracranial neck psammomatous meningioma with sizes of 4 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm. Furthermore, whole-body 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT was performed, excluding tumor spread to other areas. Surgical resection of the tumor was accomplished, as well as skin flap reconstruction, obtaining radical removal and satisfying wound healing. PEMs could suggest an infiltrative and aggressive behavior, which has never found a histopathological correlation with a malignancy (low Ki-67, <5%). Whole-body 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT should be considered in the patient’s global assessment. Surgical removal is a resolutive treatment, and the examination of frozen sections can confirm the benignity of the lesion, reducing the extension of the removal of healthy tissue surrounding the tumor.

1. Introduction

Meningiomas represent the most common benign histological tumor of the central nervous system; they originate from cellular elements of the meninges, arachnoid cap cells, arachnoid granulations, subarachnoid blood vessels, fibroblasts, and pia mater [1]. Usually, meningiomas are intracranial, showing a typical “dural tail” sign on brain MRI with Gadolinium, but occasionally they can infiltrate the skull or be sited extracranially [2]. Chronic inflammation processes or oral surgery can trigger the proliferation of these ectopic cells or the stimulation of multipotent mesenchymal cells, thus forming extracranial meningiomas (EMs) [3]. Due to their rarity, EMs can be misdiagnosed: their current occurrence is underestimated, affecting their clinical management negatively. Differential diagnoses should be made with schwannomas, soft tissue perineuriomas, neurofibromas, and paragangliomas [4,5]. Histologically, perineuriomas share many features with meningiomas, but the latter show higher morbidity and greater incidence of neighboring structures infiltration. Indeed, the management of meningiomas includes radiosurgery to treat eventual tumor remnants, and the surgical strategy is more aggressive if compared to perineuriomas [4,5]. Ultrastructural investigation along with immunohistochemistry study is needed to make a proper meningioma diagnosis [4]. We performed a systematic literature review, and we present an emblematic case of primary neck extracranial meningioma, providing further insights into the behavior of these rare tumors, thus improving their clinical management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Selection

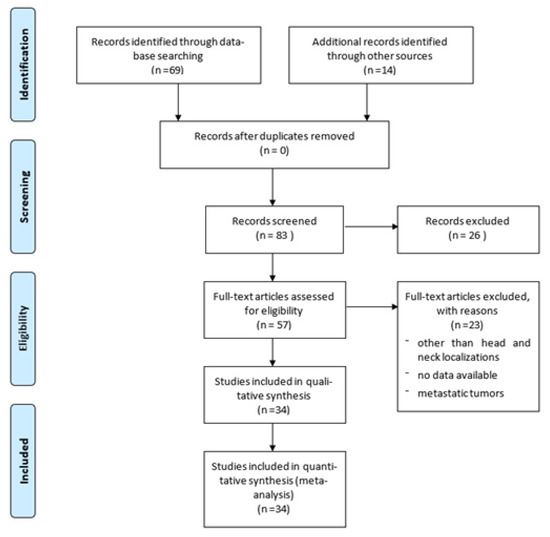

A literature search was conducted from 1979 to June 2021 (last published studies in 2020) using PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases, searching for the following Mesh terms: (primary extracranial meningioma) AND (head OR neck). Papers not written in English were excluded from this study. The PRISMA flow diagram for our search is outlined in Figure 1. The reference lists of all articles discovered in these searches were examined for any additional relevant papers (manual search). Meningiomas involving the spine or extra-neural sites except for head and neck, as well as metastatic locations and malignant histotypes, were excluded. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all extracted citations and then reviewed the full texts of the studies that met the inclusion criteria. A third reviewer settled disagreements.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram summarizing our searches and selection of studies included in the literature review of extracranial meningiomas of the head and neck.

2.2. Data Extraction

One reviewer extracted data from the included articles, then confirmed independently by two additional reviewers. Missing data were either not reported in the original paper or could not be differentiated from other data. All included studies were meticulously reviewed and scrutinized for their study design, methodology, patient characteristics, and extraneural location. Data for all patients were recorded when available, including age, sex, localization, histological grading, treatment, possible recurrence, and outcome. The risk of bias was independently assessed by two reviewers using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklists for case reports and case series (Supplementary Table S1).

3. Results

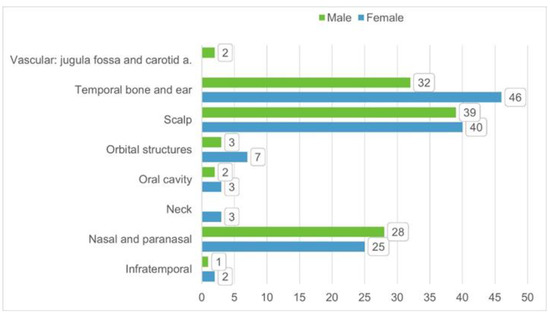

A total of 83 published studies were identified through PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases and additional reference list searches from 1979 to date. After a detailed examination of these studies, 49 papers were excluded from our review because they reported localizations other than head and neck or cases of metastatic tumors, or they had no data available. Patients’ demographics are reported in Table 1 [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. The 34 published studies of this literature review include a total of 231 patients, 106 males (46%) and 124 females (54%), 1 patient not specified (0.4%), with a male/female ratio of 85% (106/124). The reported median age was 36 years (range 0.3–88). The patient distribution by sex and localization is reported in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Summary of 34 studies focused on extracranial primary meningiomas of the head and neck, including authors and year, patients’ demographics, localization, histology and grading, treatment, recurrence, and outcome.

Figure 2.

Distribution of patient per sex and tumor/disease localization based on the 34 identified studies from literature.

Surgical resection was performed in 99.1% of patients (229/231). In the remaining four cases, two were partial resections (one patient with neck and the other with oral cavity disease) and one excisional biopsy (patient with oral cavity disease), while the localization and the type of resection were not reported in one patient with neck disease.

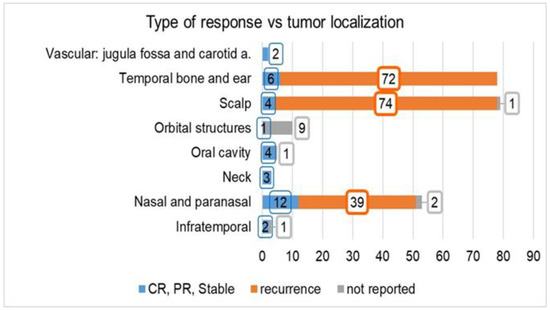

The distribution by type of response versus tumor localization is reported in Figure 3. A higher number of recurrences was observed in lesions located in the scalp (95% = 74/78 patients) and temporal bone and ear (92% = 72/78 patients), while in the lesions located in the nasal and paranasal areas, the rate of recurrence was 76% (39/51 patients). In the remaining localizations, the overall number of patients with a complete response was 12, while the patient outcome was not reported in 11 other patients.

Figure 3.

Type of response (complete, partial, stable, or recurrence) reported in the investigated studies vs. tumor localization. The number of cases for which the tumor response is “not reported” is also indicated. Abbreviations: CR: complete response, PR: partial response.

Case Illustration

A 45-year-old male was referred to our department complaining of a cutaneous posterior neck lesion, present since birth, characterized by a callous appearance and superficial protuberance, with a diameter of 4 cm × 3 cm and a thickness of 2 cm (Figure 4). Since the lesion was asymptomatic, the patient had decided not to perform any medical investigations in youth. The lesion did not show any modification over time, but it presented a superficial infection, managed with medication. Then, he decided to perform a radiological imaging study.

Figure 4.

Macroscopic direct posterior view showing a cutaneous nuchal lesion, present from birth, characterized by a callous appearance and superficial protuberance, with a diameter of 4 cm × 3 cm and a thickness of 2 cm.

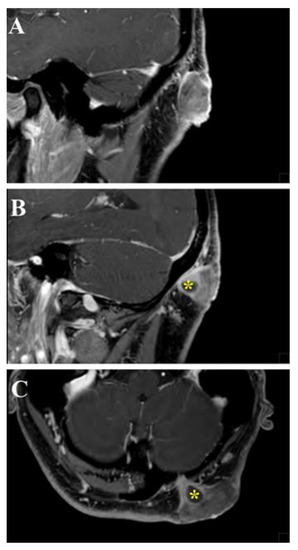

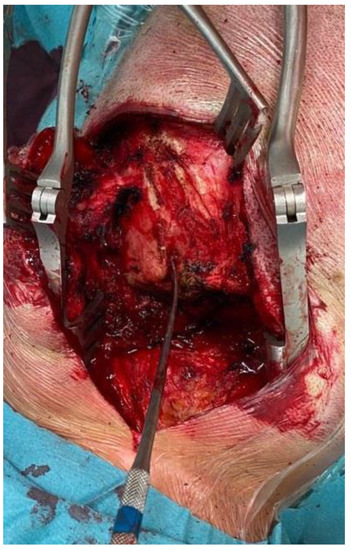

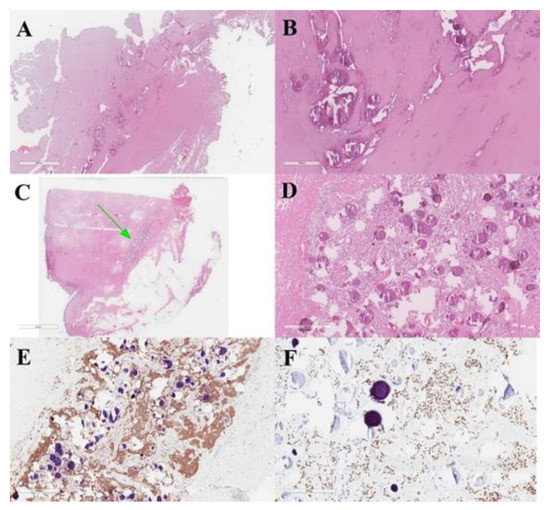

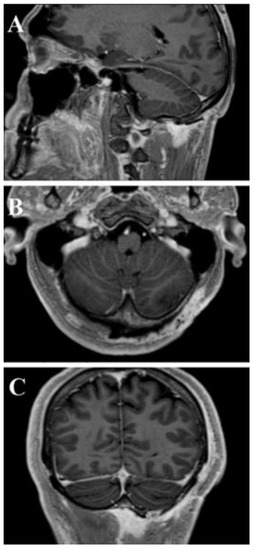

The patient underwent a head and neck MRI with Gadolinium, which showed a cutaneous mass characterized by homogeneous post-contrast enhancement, isointense in T1-weighted sequences, with a characteristic sinus-like propagation that connected the tumor with the cerebellar dura mater through a small defect in the left occipital bone (Figure 5). A whole-body 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT was performed, excluding a tumor spread in other body areas. After a multidisciplinary meeting, we decided to perform tumor removal and scalp reconstruction. The first stage of the procedure was conducted by neurosurgeons, performing a hockey stick skin incision exposing the occipital bone and the fistulous tract exposure (Figure 6). Small drilling of the bone was performed, and the dural infiltration was removed. Duroplasty was performed with a heterologous patch, Tachosil, and Tissel. The tumor was then removed en bloc and sent for histological examination. The plastic surgeons performed the second stage of the surgery–closure (in layers after careful hemostasis) and skin reconstruction. An occipital rotation flap with a right lateral pedicle was performed to cover the skin defect; a drain was placed, and the scalp was closed. The final pathological examination showed fibrous tissue from meningioma with psammomatous bodies. Figure 7 shows dermo-hypodermic localization of predominantly fibrous meningioma with WHO grade I psammomatous bodies and ulceration of the epidermis. The wound healed well, and the 6-month post-operative MRI scan showed the absence of residual tumor (Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Head and neck MRI sagittal (A,B) and axial (C) images showed a cutaneous mass characterized by homogeneous post-gadolinium enhancement, isointense in T1-weighted sequences, with a characteristic sinus-like propagation that connected the tumor with the cerebellar dura mater through a small passage in the left occipital bone (yellow asterisks).

Figure 6.

Intraoperative image showing occipital bone exposure and the fistulous tract with a Penfield dissector as a landmark.

Figure 7.

Meningeal fistulous tract of the cervical cutis, represented by fibrous tissue infiltrated by meningioma with psammomatous bodies (A,B). Dermo-hypodermic localization of predominantly fibrous meningioma with WHO grade I psammomatous bodies (green arrow) (C,D). Immunostaining was positive for EMA (E) and progesterone (F).

Figure 8.

Post-operative head and neck MRI T1-WI with Gadolinium—sagittal (A), axial (B), and coronal (C) areas showed absence of residual tumor.

4. Discussion

PEMs of the head and neck are uncommon, representing 1–2% of all meningioma localizations. They show benign behavior with good outcomes. In the literature, it is possible to find case reports of extracranial meningiomas at the level of the nasal and paranasal cavities [39], and with progressively decreasing frequency at the level of cranial bones [40], middle ear [15], or within the soft tissues of the head and neck. The pathophysiology of PEMs has been associated with defects of cell migration from the neural crest. However, several possible mechanisms have been proposed: origin from arachnoid cells of nerve sheaths protruding from the skull foramina, ectopic arachnoid granulations, related to traumatism, intracranial hypertension (which could cause the movement of groups of arachnoid cells), or, finally, a possible origin from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells [41].

The case presented showed the unique feature of a connection of the tumor, sited at the level of the skin, to the cerebellar dura mater through a small bone defect. We supposed that the tumor could have originated from arachnoid cells at the level of the cerebellar dura mater; then, because of the progressive growth of the tumor, the tumor may have found a weakness in an emissary vein passing along the occipital bone, through which it expanded to the skin layers. According to this theory, our case should be classified as type A of the Hoye classification (extracranial extension of a meningioma with an intracranial origin, secondary) [42].

Based on their histological and immunohistochemical characteristics, PEMs can be classified as common intracranial meningiomas [43]. Epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin are usually expressed, protein S-100 may show variability, and acidic gliofibrillary protein is usually negative. The presence of these tumors in extracranial sites could suggest an infiltrative and aggressive behavior, which has never found a histopathological correlation with malignancy. This observation is supported by a low Ki-67, which is usually less than 5%. PEMs must be differentiated from several neoplasms, both benign and malignant: epithelial tumors, melanoma, olfactory neuroblastoma, angiofibroma, paraganglioma, and ossifying fibroma [43]. The histological and immunohistochemical differential diagnosis is uncomplicated, and, in more complex and rare cases, the study of protein S-100, cytokeratin, and HMB-45 may help overcome any doubts. The clinical outcome and prognosis of PEMs are favorable, in accordance with the benign histological findings [44,45,46]. A radical removal represents the gold standard to prevent any possible growth of the residual tumor. Considering the rarity of these tumors, clinical examination and neuroimaging are not pathognomonic, so the final diagnosis requires histological investigation. Surgical removal is resolutive, and the examination of frozen sections can confirm the benignity of the lesion, reducing the extension of the removal of healthy tissue surrounding the tumor.

5. Conclusions

PEMs could suggest an infiltrative and aggressive behavior, which has never found a histopathological correlation with malignancy (low Ki-67, <5%). Considering the rarity of these tumors, clinical examination and neuroimaging are not pathognomonic, so the final diagnosis requires histological investigation. Whole-body 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT should be considered in the global assessment of the pathology. Surgical removal is the treatment of choice, and the examination of frozen sections can confirm the benignity of the lesion, reducing the extension of the removal of healthy tissue surrounding the tumor.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/life11090942/s1, Figure S1: PRISMA flow diagram summarizing our searches and selection of studies included in the literature review of extracranial meningiomas of the head and neck., Table S1: Summary of 34 studies focused on extracranial primary meningiomas of the head and neck, including authors and year, patients’ demographics, localization, histology and grading, treatment, recurrence, and outcome.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.E.U., G.S. and R.E.P.; methodology, G.E.U., G.S., R.M., G.R. and S.C. (Salvatore Cicero); software, G.S. and L.S.; validation, G.P., M.P., F.B., A.V., F.G., M.G.T., S.C. (Sebastiano Cosentino), M.I. and S.O.T.; formal analysis, L.S. and G.E.U.; inves-tigation, G.S., F.G. and R.M.; resources, G.S. and R.E.P.; data curation, G.E.U., B.C., S.C. (Sebas-tiano Cosentino), and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, G.E.U. and G.S.; writ-ing—review and editing, S.C. (Salvatore Cicero), G.F.N., R.E.P., D.G.I. and R.M.; visualization, S.C. (Salvatore Cicero) and R.E.P.; supervision, L.S. and S.C. (Salvatore Cicero); project admin-istration, G.E.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the type of the manuscript (systematic review).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Gabriella Patané for the language revision and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rege, I.C.C.; Garcia, R.R.; Mendonça, E.F. Primary Extracranial Meningioma: A Rare Location. Head Neck Pathol. 2017, 11, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, M.; Sneddon, K. Extracranial meningioma of the oral cavity. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1987, 25, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landini, G.; Kitano, M. Meningioma of the mandible. Cancer 1992, 69, 2917–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaimy, A.; Buslei, R.; Coras, R.; Rubin, B.P.; Mentzel, T. Comparative study of soft tissue perineurioma and meningioma using a five-marker immunohistochemical panel. Histopathology 2014, 65, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutlas, I.G.; Scheithauer, B.W.; Folpe, A.L. Intraoral Perineurioma, Soft Tissue Type: Report of Five Cases, Including 3 Intraosseous Examples, and Review of the Literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2010, 4, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Michel, R.G.; Woodard, B.H. Extracranial Meningioma. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1979, 88, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, J.M.; Birt, B.D.; Lewis, A.J.; Nedzelski, J.M. Primary meningioma of the nasopharynx: Case report and review of ectopic meningioma. J. Otolaryngol. 1985, 14, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, C.D.; Costantino, P.D.; Teitelbaum, B.; Berktold, R.E.; Sisson, G.A. Primary Extracranial Meningiomas of the Head and Neck. Laryngoscope 1990, 100, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Mihara, M.; Hagari, Y.; Shimao, S. Primary Cutaneous Meningioma on the Scalp: Report of Two Siblings. J. Dermatol. 1995, 22, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, R.C.; Kapadia, S.B.; Kamerer, D.B. Primary Extracranial Meningioma of the Temporal Bone. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998, 118, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabor, M.A.; Amedee, R.G.; Gianoli, G.J. Primary meningioma of the fallopian canal. South Med. J. 2000, 93, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, A.; Roy, D.; Irvine, B.W.H. Primary extracranial meningioma of the soft palate. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2000, 114, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Saha, S. A rare case of primary extracranial meningioma of the Paranasal Sinuses. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2001, 53, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Gokden, M.; Hanna, E.Y. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of a primary ectopic meningioma. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2002, 26, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.D.R.; Bouffard, J.-P.; Sandberg, G.D.; Mena, H. Primary Ear and Temporal Bone Meningiomas: A Clinicopathologic Study of 36 Cases with a Review of the Literature. Mod. Pathol. 2003, 16, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.; Kissun, D.; Boyle, M.; Triantafyllou, A. Primary meningioma of the scalp as a late complication of skull fracture: Case report and literature review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 33, 509–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshete, M.; Schneider, J. Extracranial meningioma of the scalp: Case report. Ethiop. Med. J. 2005, 43, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, X.-C.; Wang, C.-X.; Jiang, C.-H. Surgical management of primary and secondary tumors in the pterygopalatine fossa. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2005, 132, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouazzani, A.; De Fontaine, S.; Berthe, J.-V. Extracranial meningioma and pregnancy: A rare diagnosis. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2007, 60, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushing, E.J.; Bouffard, J.-P.; McCall, S.; Olsen, C.; Mena, H.; Sandberg, G.D.; Thompson, L.D.R. Primary Extracranial Meningiomas: An Analysis of 146 Cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2009, 3, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutt, A.L.; Chen, X.; Sataloff, R.T. Jugular Fossa Meningioma: Presentation and Treatment Options. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009, 88, 1169–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzarae, A.H.; Hussein, M.R.; Amri, D.; Mokarbesh, H.M. Primary Meningioma of the Nasal Septum. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2010, 18, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, M.; Ikonomidis, C.; Pusztaszeri, M.; Monnier, P. Primary meningioma of the middle ear: Case report. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2009, 124, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Deshmukh, S.D.; Rokade, V.V.; Pathak, G.S.; Nemade, S.V.; Ashturkar, A.V. Primary extra-cranial meningioma in the right submandibular region of an 18-year-old woman: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2011, 5, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, R.G.; Prashanth, V.; Ambani, K.; Bhat, S.; Soni, G.B. Primary Extracranial Meningioma of Paranasal Sinuses. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012, 65, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, B.J.; Shin, J.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, K.H. Atypical primary meningioma in the nasal septum with malignant transformation and distant metastasis. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possanzini, P.; Pipolo, C.; Romagnoli, S.; Falleni, M.; Moneghini, L.; Braidotti, P.; Salvatori, P.; Paradisi, S.; Felisati, G. Primary extra-cranial meningioma of head and neck: Clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical study of three cases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2012, 32, 336–338. [Google Scholar]

- Zulkiflee, A.B.; Prepageran, N.; Rahmat, O.; Jayalaskhmi, P.; Sharizal, T. Hypoglossal nerve tumor: A rare primary extracranial meningioma of the neck. Ear Nose Throat J. 2012, 91, E26–E29. [Google Scholar]

- Maeng, J.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Seo, J.; Kim, S.W. Primary Extracranial Meningioma Presenting as a Cheek Mass. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 6, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocque, R.; Khalbuss, W.E.; Monaco, S.E.; Michelow, P.M.; Pantanowitz, L. Cytopathology of Extracranial Ectopic and Metastatic Meningiomas. Acta Cytol. 2014, 58, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albsoul, N.; Rawashdeh, B.; Albsoul, A.; Abdullah, M.; Golestani, S.; Rawshdeh, A.; Mohammad, A.; Alzoubi, M. A rare case of extracranial meningioma in parapharyngeal space presented as a neck mass. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2015, 11, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asil, K.; Aksoy, Y.E.; Yaldiz, C.; Kahyaoğlu, Z. Primary intraosseous meningiomas mimicking osteosarcoma: Case report. Turk. Neurosurg. 2014, 25, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakiram, T.N.; Parekh, P.; Subramaniam, V. Primary Extracranial Meningioma: The Royal Pearl Experience. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 67, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, D.; Jana, M.; Sur, P.K.; Khan, E.M. Primary Sinonasal Meningioma in a Child. Ear Nose Throat J. 2015, 94, E7–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, P.; Hu, Y.-J. An Ectopic Meningioma in Nasal Floor. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2015, 26, e88–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Qu, X. Primary Ectopic Meningioma of the Tongue: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 2216–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Sim, H.S.; Hwang, J.H.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, S.Y. Extracranial Meningioma Presenting as an Eyebrow Mass. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2017, 28, e305–e307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radke, P.M.; Herreid, P.A.; Sires, B.S. Primary Extracranial Meningioma of the Lacrimal Sac Fossa. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 34, e147–e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrulionis, M.; Valeviciene, N.; Paulauskiene, I.; Bruzaite, J. Primary extracranial meningioma of the sinonasal tract. Acta Radiol. 2005, 46, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Freedman, P.D. Primary extracranial meningioma of the mandible: A report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 2001, 91, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serry, P.; Rombaux, P.; Ledeghen, S.; Collet, S.; Eloy, P.; Hamoir, M.; Bertrand, B. Extracranial sinonasal tract meningioma: A case report. Acta Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Belg. 2004, 58, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hoye, S.J.; Hoar, C.S.; Murray, J.E. Extracranial meningioma presenting as a tumor of the neck. Am. J. Surg. 1960, 100, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, P.C.; Scheithauer, B.W. Tumors of meningothelial cells. In Tumors of the Central Nervous System, 3rd ed.; Armed Forces institute of Pathology: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Malagon, H.; Ordòñez, N.G. Malignant Meningioma of the Parapharyngeal Space: A Case Report. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 1996, 20, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huszar, M.; Fanburg, J.C.; Dickersin, G.R.; Kirshner, J.J.; Rosenberg, A.E. Retroperitoneal Malignant Meningioma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1996, 20, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraioli, M.F.; Marciani, M.G.; Umana, G.E.; Fraioli, B. Anterior Microsurgical Approach to Ventral Lower Cervical Spine Meningiomas: Indications, Surgical Technique and Long Term Outcome. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 14, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).