The Role of the Rare Variants in the Genes Encoding the Alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

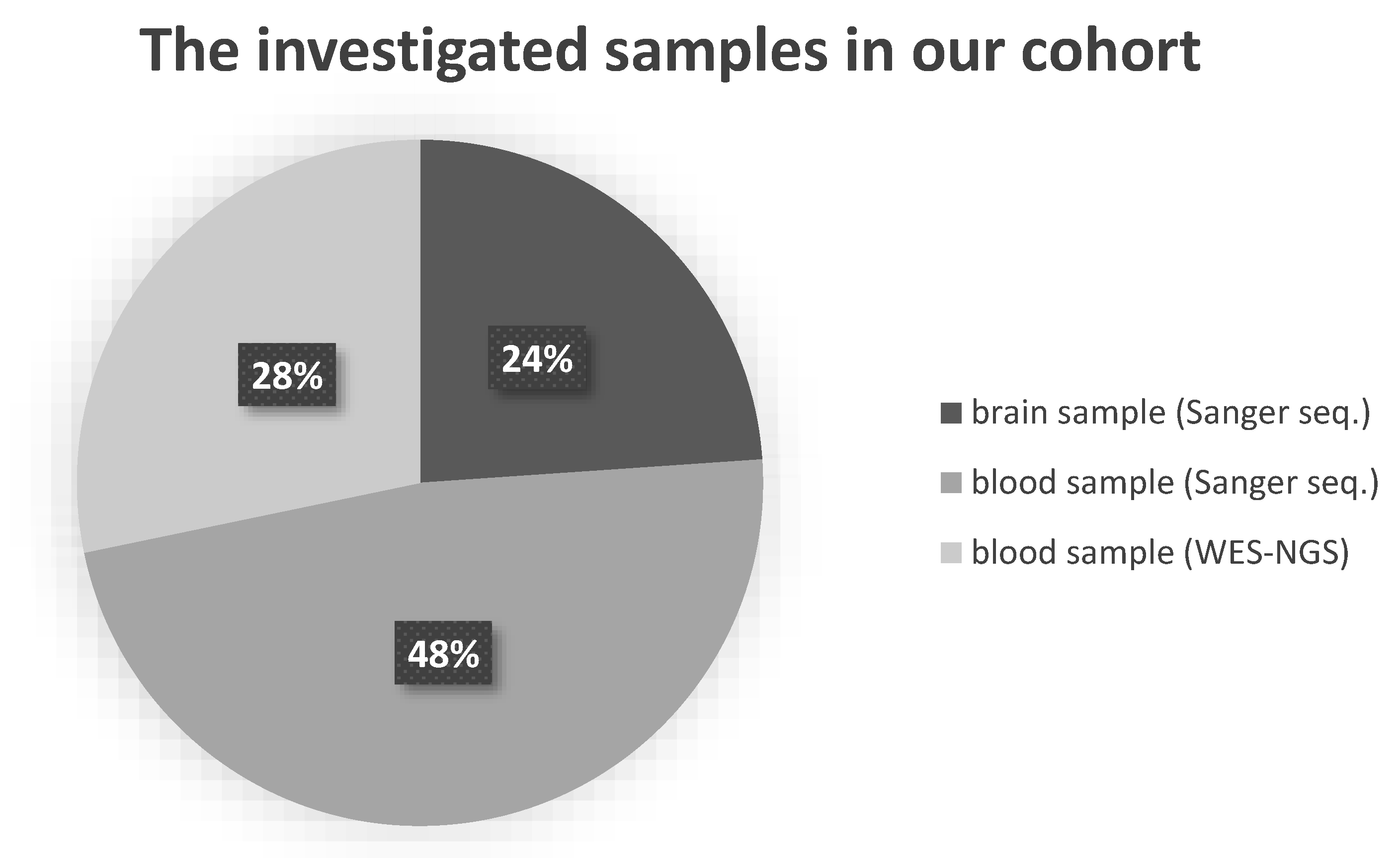

2.2. Genetic Investigations

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deture, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Association 2014 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers. Dement. 2014, 10, e47–e92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blennow, K.; de Leon, M.J.; Zetterberg, H. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2006, 368, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sidorenko, J.; Couvy-Duchesne, B.; Marioni, R.E.; Wright, M.J.; Goate, A.M.; Marcora, E.; Huang, K.; Porter, T.; Laws, S.M.; et al. Risk prediction of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease implies an oligogenic architecture. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, R.; Sleegers, K.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Molecular genetics of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease revisited. Alzheimers Dement. 2016, 12, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Giau, V.; Senanarong, V.; Bagyinszky, E.; An, S.S.A. Analysis of 50 Neurodegenerative Genes in Clinically Diagnosed Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bis, J.C.; Jian, X.; Kunkle, B.W.; Chen, Y.; Hamilton-Nelson, K.L.; Bush, W.S.; Salerno, W.J.; Lancour, D.; Ma, Y.; Renton, A.E.; et al. Whole exome sequencing study identifies novel rare and common Alzheimer’s-Associated variants involved in immune response and transcriptional regulation. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 1859–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmohan, R.; Reddy, P.H. Amyloid-Beta and Phosphorylated Tau Accumulations Cause Abnormalities at Synapses of Alzheimer’s disease Neurons. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 57, 975–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, P.V.; Growdon, J.H.; Hedley-Whyte, E.T.; Hyman, B.T. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1992, 42, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondria and Mitochondrial Cascades in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 1403–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Perry, G.; Lee, H.G.; Zhu, X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2014, 1842, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, F.; Ma, X.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Bai, F. The association of tau with mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 2014–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckert, A.; Nisbet, R.; Grimm, A.; Götz, J. March separate, strike together—Role of phosphorylated TAU in mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2014, 1842, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, L.; Pupi, A.; De Leon, M.J. Brain Glucose Hypometabolism and Oxidative Stress in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1147, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, S.; Pan, X.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, F.; Pan, S.; Liu, H.; Jin, L.; Fei, G.; Wang, C.; Ren, S.; et al. Thiamine diphosphate reduction strongly correlates with brain glucose hypometabolism in Alzheimer’s disease, whereas amyloid deposition does not. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnár, M.J.; Valikovics, A.; Molnár, S.; Trón, L.; Diószeghy, P.; Mechler, F.; Gulyás, B. Cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism in mitochondrial disorders. Neurology 2000, 55, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inczedy-Farkas, G.; Trampush, J.W.; Perczel Forintos, D.; Beech, D.; Andrejkovics, M.; Varga, Z.; Remenyi, V.; Bereznai, B.; Gal, A.; Molnar, M.J. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and cognition: A case-series report. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2014, 29, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobolyi, A.; Bago, A.; Palkovits, M.; Nemeria, N.S.; Jordan, F.; Doczi, J.; Ambrus, A.; Adam-Vizi, V.; Chinopoulos, C. Exclusive neuronal detection of KGDHC-specific subunits in the adult human brain cortex despite pancellular protein lysine succinylation. Brain Struct. Funct. 2020, 225, 639–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, A. An Updated View on the Molecular Pathomechanisms of Human Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Light of Novel Crystallographic Evidence. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 2307–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, A.; Torocsik, B.; Tretter, L.; Ozohanics, O.; Adam-Vizi, V. Stimulation of reactive oxygen species generation by disease-causing mutations of lipoamide dehydrogenase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 2984–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, E.; Mizsei, R.; Wilk, P.; Zambo, Z.; Torocsik, B.; Weiss, M.S.; Adam-Vizi, V.; Ambrus, A. Crystal structures of the disease-causing D444V mutant and the relevant wild type human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 124, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, E.; Wilk, P.; Nagy, B.; Zambo, Z.; Bui, D.; Weichsel, A.; Arjunan, P.; Torocsik, B.; Hubert, A.; Furey, W.; et al. Underlying molecular alterations in human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase deficiency revealed by structural analyses of disease-causing enzyme variants. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 3339–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, K.R.; Cooper, A.J.L.; Koike, K.; Koike, M.; Lindsay, J.G.; Blass, J.P. Abnormality of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in fibroblasts from familial Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1994, 35, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stempler, S.; Yizhak, K.; Ruppin, E. Integrating transcriptomics with metabolic modeling predicts biomarkers and drug targets for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, K.F.R.; Blass, J.P. The α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 893, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretter, L.; Adam-Vizi, V. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: A target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 2335–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Xu, H.; Kleinman, W.A.; Gibson, G.E. Novel functions of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex may mediate diverse oxidant-induced changes in mitochondrial enzymes associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2008, 1782, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, A.; Adam-Vizi, V. Human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (E3) deficiency: Novel insights into the structural basis and molecular pathomechanism. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 117, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Alonso, I.; Navarrete, R.; Vega, A.I.; Ruíz-Sala, P.; García Silva, M.T.; Martín-Hernández, E.; Quijada-Fraile, P.; Belanger-Quintana, A.; Stanescu, S.; Bueno, M.; et al. Genes and Variants Underlying Human Congenital Lactic Acidosis-From Genetics to Personalized Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinonez, S.C.; Thoene, J.G. Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency. In GeneReviews® (Internet); University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220444/ (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- Gibson, G.E.; Park, L.C.; Sheu, K.-F.R.; Blass, J.P.; Calingasan, N.Y. The α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in neurodegeneration. Neurochem. Int. 2000, 36, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W. Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase suppression induces human tau phosphorylation by increasing whole body glucose levels in a C. elegans model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2018, 236, 2857–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inczédy-Farkas, G.; Benkovits, J.; Balogh, N.; Álmos, P.; Scholtz, B.; Zahuczky, G.; Török, Z.; Nagy, K.; Réthelyi, J.; Makkos, Z.; et al. SCHIZOBANK—The Hungarian national schizophrenia biobank and its role in schizophrenia research. Orv. Hetil. 2010, 151, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From fastQ Data to High-Confidence Variant Calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit Best Practices Pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2013, 43, 11.10.1–11.10.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Benson, M.; Brown, G.; Chao, C.; Chitipiralla, S.; Gu, B.; Hart, J.; Hoffman, D.; Hoover, J.; et al. ClinVar: Public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D862-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, H.M.; Thorland, E.C.; Brown, K.K.; Quintero-Rivera, F.; South, S.T. American College of Medical Genetics standards and guidelines for interpretation and reporting of postnatal constitutional copy number variants. Genet. Med. 2011, 13, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanos, C.; Tsiolkas, V.; Kouris, A.; Chapple, C.E.; Albarca Aguilera, M.; Meyer, R.; Massouras, A. VarSome: The human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1978–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin by Genoox. Available online: https://franklin.genoox.com (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Simoncini, C.; Orsucci, D.; Caldarazzo Ienco, E.; Siciliano, G.; Bonuccelli, U.; Mancuso, M. Alzheimer’s pathogenesis and its link to the mitochondrion. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lek, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Minikel, E.V.; Samocha, K.E.; Banks, E.; Fennell, T.; O’Donnell-Luria, A.H.; Ware, J.S.; Hill, A.J.; Cummings, B.B.; et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016, 536, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautigam, C.A.; Chuang, J.L.; Tomchick, D.R.; Machius, M.; Chuang, D.T. Crystal structure of human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase: NAD +/NADH binding and the structural basis of disease-causing mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 350, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, E.; Pineda, M.; Font, A.; Vilaseca, M.A.; Tort, F.; Ribes, A.; Briones, P. Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLD) deficiency in a Spanish patient with myopathic presentation due to a new mutation in the interface domain. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010, 33, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odièvre, M.-H.; Chretien, D.; Munnich, A.; Robinson, B.H.; Dumoulin, R.; Masmoudi, S.; Kadhom, N.; Rötig, A.; Rustin, P.; Bonnefont, J.-P. A novel mutation in the dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase E3 subunit gene (DLD) resulting in an atypical form of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2005, 25, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.M.; Gordon, D.; Lee, H.; De Vrièze, F.W.; Cellini, E.; Bagnoli, S.; Nacmias, B.; Sorbi, S.; Hardy, J.; Blass, J.P. Testing for linkage and association across the dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase gene region with Alzheimer’s disease in three sample populations. Neurochem. Res. 2007, 32, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiacomo, F.; Bergeron, C.; Kish, S.J. Brain α-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complex Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 1993, 61, 2007–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Variant ID | Variant Effect | Clinical Significance | ACMG Classification | MAF (GnomAD, Non-Finnish) | Patients | Controls | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OGDH | c.164 C > T p. S55L | missense | B | Likely Benign | 1.07% | 2/46 | 4/134 | - |

| c.345 A > G E115E | synonymous | B | Benign | 2.47% | 1/46 | 18/134 | - | |

| c.396 G > A S132S | synonymous | B | Benign | 4.88% | 1/46 | 5/134 | - | |

| c.682 C > T L228L | synonymous | B | Likely Benign | - | 2/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.1275 C > T H425H | synonymous | B | Likely Benign | - | 1/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.1302 T > A T434T | synonymous | B | Likely Benign | - | 1/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.1412 C > A P471H | missense | B | Uncertain Significance | - | 1/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.1809 C > A S603S | synonymous | B | Likely Benign | - | 1/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.2988 C > T T996T | synonymous | B | Benign | 5.04% | 1/46 | 10/134 | - | |

| c.3052 G > A V1018I | missense | B | Benign | 5.05% | 2/46 | 12/134 | - | |

| c.3063 C > T N1021N | synonymous | B | Benign | 5.05% | 1/46 | 10/134 | - | |

| DLST | c.611 C > T P204L | missense | B | Uncertain Significance | 2.27% | 1/46 | 4/134 | - |

| DLD | c.788 G > A R263H | missense | D | Uncertain Significance | ≤0.01 | 1/46 | 0/134 | [30] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Csaban, D.; Pentelenyi, K.; Toth-Bencsik, R.; Illes, A.; Grosz, Z.; Gezsi, A.; Molnar, M.J. The Role of the Rare Variants in the Genes Encoding the Alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase in Alzheimer’s Disease. Life 2021, 11, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11040321

Csaban D, Pentelenyi K, Toth-Bencsik R, Illes A, Grosz Z, Gezsi A, Molnar MJ. The Role of the Rare Variants in the Genes Encoding the Alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase in Alzheimer’s Disease. Life. 2021; 11(4):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11040321

Chicago/Turabian StyleCsaban, Dora, Klara Pentelenyi, Renata Toth-Bencsik, Anett Illes, Zoltan Grosz, Andras Gezsi, and Maria Judit Molnar. 2021. "The Role of the Rare Variants in the Genes Encoding the Alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase in Alzheimer’s Disease" Life 11, no. 4: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11040321

APA StyleCsaban, D., Pentelenyi, K., Toth-Bencsik, R., Illes, A., Grosz, Z., Gezsi, A., & Molnar, M. J. (2021). The Role of the Rare Variants in the Genes Encoding the Alpha-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase in Alzheimer’s Disease. Life, 11(4), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11040321