Increased Depression and Anxiety Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents: A Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Depressive and Anxiety Disorders Worldwide

1.2. Impact of the Pandemic on Mental Health

1.3. Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the Mental Well-Being of Children and Adolescents

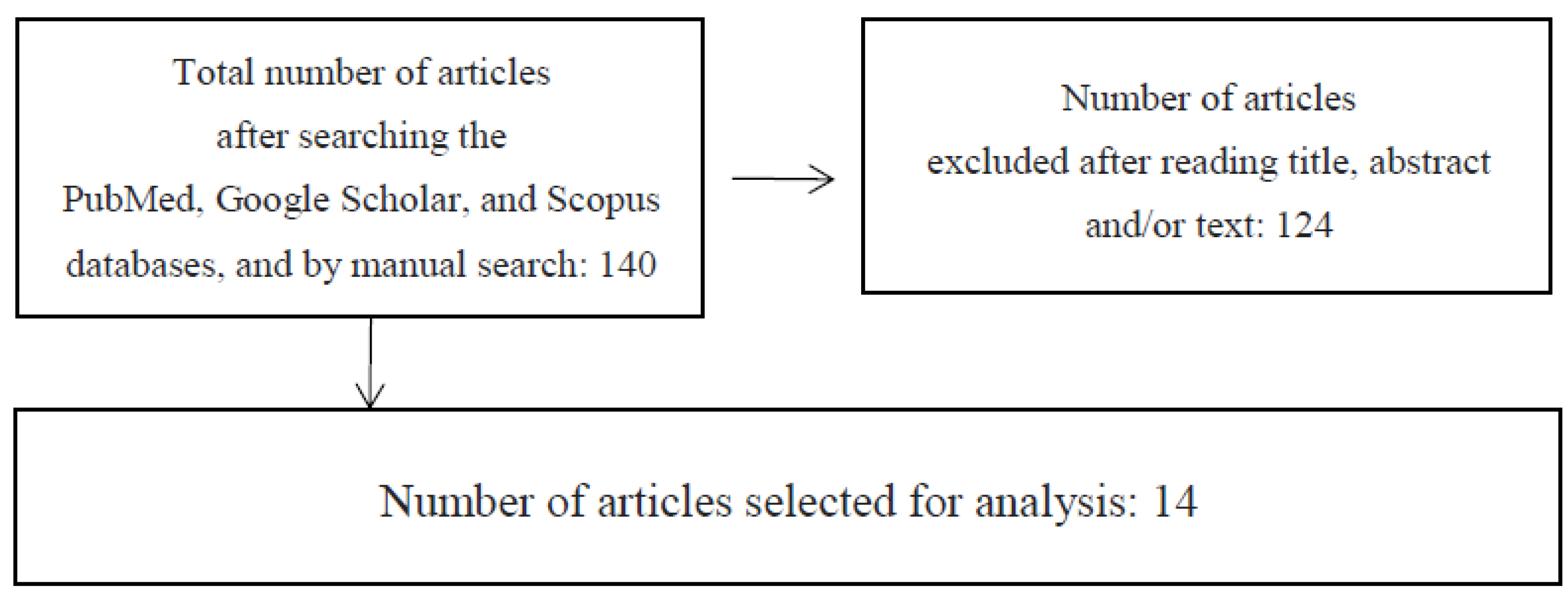

2. Materials and Methods

3. Literature Review: Results

3.1. Poland

3.2. Germany

3.3. Italy and Spain

3.4. China

3.5. The United States

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. Mental Health Home—Depression. Available online: www.who.int/topics/depression/en/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Maron, E. Biological markers of generalized anxiety disorder. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 19, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Dashboard with Vaccination Data. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tracz-Dral, J. Zdrowie Psychiczne w Unii Europejskiej Opracowania Tematyczne OT–674; Kancelaria Senatu: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reger, M.A.; Stanley, I.H.; Joine, T.E. Suicide Mortality and Coronavirus Disease 2019—A Perfect Storm? JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Horesh, D.; Brown, A.D. Traumatic Stress in the Age of COVID-19: A Call to Close Critical Gaps and Adapt to New Realities. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Gomez, M.; Giorgi, G.; Finstad, G.L.; Urbini, F.; Foti, G.; Mucci, N.; Zaffina, S.; León-Perez, J.M. COVID-19 Pandemic as a Traumatic Event and Its Associations with Fear and Mental Health: A Cognitive-Activation Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilicki, T. Jak Pracować z Uczniem w Kryzysie w Czasie Pandemii COVID-19? [How to work with a student in a crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic?]. In Edukacja w Czasach Pandemii Wirusa COVID-19. Z Dystansem o Tym, co Robimy Obecnie Jako Nauczyciele [Education in Times of the COVID-19 Virus Pandemic]; Pyżalski, W.J., Ed.; EduAkcja: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Poleszak, W.; Pyżalski, J. Psychologiczna Sytuacja Dzieci i Młodzieży w Dobie Pandemii [Psychological situation of children and adolescents in the time of the pandemic]. In Edukacja w Czasach Pandemii Wirusa COVID-19. Z Dystansem o Tym, co Robimy Obecnie Jako Nauczyciele [Education in the Time of the COVID-19 Virus Pandemic]; Pyżalski, W.J., Ed.; EduAkcja: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein, E.; Wen, H.; Miller, B.F. Coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. J. Am. Med. Assoc. Pediatrics 2020, 174, 819–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Salum, G.A.; Sugaya, L.S.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empowering Children Foundation. Children Matter 2017—A Report on Threats to the Safety and Development of Children in Poland. Available online: https://fdds.pl/_Resources/Persistent/e/d/9/e/ed9e604bde6479d99dcefb12244d1fa0bca5ac6c/Raport-Dzieci-si%C4%99-licz%C4%85-2017.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Młodzież w Czasie Epidemii. Komu jest Najtrudniej? II CZĘŚĆ Raportu z Wyników Sondażu AKCJA NAWIGACJA—Chroń siebie, Wspieraj Innych, Przeprowadzonego Przez Instytut Profilaktyki Zintegrowanej, Polska 2020 [Youth during the Epidemic. Who is the Hardest? PART II of the Report on the Results of the Survey ACTION NAVIGATION—Protect Yourself, Support Others, Conducted by the Institute of Integrated Prevention, Poland 2020]. Available online: https://ipzin.org/images/dokumenty/RAPORT_Modziez_w_czasie_epidemii_Komu_jest_najtrudniej_2020_IPZIN_Czesc_2.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Ptaszek, G.; Stunża, G.D.; Pyżalski, J.; Dębski, M.; Bigaj, M. Edukacja Zdalna: Co Stało się z Uczniami, Ich Rodzicami i Nauczycielami? [Remote Education: What Happened to Students, Their Parents and Teachers?]; Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne: Gdańsk, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://zdalnenauczanie.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ZDALNA-EDUKACJA_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Fundacja Szkoła z Klasą. Rozmawiaj z Klasą. Zdrowie Psychiczne Uczniów i Uczennic Oczami Nauczycieli i Nauczycielek; Raport z Badania; Fundacja Szkoła z Klasą: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; [School with Class Foundation. Talk to the Class. Mental Health of Pupils and Students through the Eyes of Teachers and Teachers; Research Report; The School with Class Foundation: Warsaw, Poland, 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- Mittagsmagazin 2020. Available online: https://www.dw.com/pl/niepokoj%C4%85ce-dane-wzrost-przypadk%C3%B3w-depresji-u-dzieci-i-m%C5%82odzie%C5%BCy/a-57768531 (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Otto, C.; Adedeji, A.; Napp, A.K.; Becker, M.; Blanck-Stellmacher, U.; Löffler, C.; Schlack, R.; Hölling, H.; et al. Mental health and psychological burden of children and adolescents during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic-results of the COPSY study. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2021, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffo, E.; Scandroglio, F.; Asta, L. Debate: COVID-19 and psychological well-being of children and adolescents in Italy. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 25, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M.; Morales, A.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C.; Espada, J.P. Immediate Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Quarantine in Youth from Italy and Spain. 2020. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/5bpfz/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Girolamo, G.; Cerveri, G.; Clerici, M.; Monzani, E.; Spinogatti, F.; Starace, F.; Tura, G.; Vita, A. Mental Health in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Emergency-The Italian Response. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 974–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xiang, M.; Cheung, T.; Xiang, Y. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 15, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Somatic symptoms and concern regarding COVID-19 among Chinese college and primary school students: A cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Xue, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Song, R. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatrics 2020, 174, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, S.-J.; Zhang, L.-G.; Wang, L.-L.; Guo, Z.-C.; Wang, J.-Q.; Chen, J.-C.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.-X. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.Y.; Wang, L.N.; Liu, J.; Fang, S.F.; Jiao, F.Y.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Somekh, E. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Pediatrics 2020, 221, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterhoff, B.; Palmer, C.A.; Wilson, J.; Shook, N. Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with mental and social health. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, D.G., Jr. The U.S. Now Leads the World in Confirmed Coronavirus Cases. New York Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/26/health/usa-coronavirus-cases.html (accessed on 26 March 2020).

- Rosen, Z.; Weinberger-Litman, S.L.; Rosenzweig, C.; Rosmarin, D.H.; Muennig, P.; Carmody, E.R.; Rao, S.T.; Litman, L. Anxiety and distress among the first community quarantined in the U.S. due to COVID-19: Psychological implications for the unfolding crisis. PsyArxiv 2020. preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.T.; Szenczy, A.K.; Klein, D.N.; Hajcak, G.; Nelson, B.D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golberstein, E.; Gonzales, G.; Meara, E. How do Economic Downturns Affect the Mental Health of Children? Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Health Econ. 2019, 28, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, B.J.; Costello, E.J.; Angold, A.; Tweed, D.; Stangl, D.; Farmer, E.M.; Erkanli, A. Children’s mental health service use across service sectors. Health Aff. 1995, 14, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domagała-Zyśk, E. Zdalne Uczenie Się i Nauczanie a Specjalne Potrzeby Edukacyjne. In Z Doświadczeń Pandemii Covid-19; Wydawnictwo Episteme: Lublin, Poland, 2020; [Domagała-Zyśk, E. Remote learning and teaching and special educational needs. In From the Experiences of the Covid-19 Pandemic; Episteme Publishing House: Lublin, Poland, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Doucet, A.; Netolicky, D.; Timmers, K.; Tuscano, F.J. Thinking about Pedagogy in an Unfolding Pandemic: An Independent Report on Approaches to Distance Learning during COVID19 School Closures. 2020. Available online: https://issuu.com/educationinternational/docs/2020_research_covid-19_eng (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Racine, N.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Korczak, D.J.; McArthur, B.; Madigan, S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country | Participants | Mental Health Outcomes | Mental Health Measures | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Institute of Integrated Prophylaxis, 2020 | Poland | 2475 people aged 13–19 years | fear, nervous, irritated, lacking in energy, lonely, anxious, sad | internet survey | - |

| Ptaszek et al., 2020 | Poland | pupils n = 1284, parents n = 979, teachers n = 671 | sadness, loneliness, depression | internet survey |

|

| Schools with Class Foundation, 2021 | Poland | teachers n = 1535 | depression, risk of suicide | internet survey with closed and open questions | older students are more likely to experience depression |

| Mittagsmagazin, 2020 | Germany | 209,332 children and adolescent aged 6–18 years | depression, adaptation disorders, burnout disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders | internet survey | increase of more than 20% in all mental illnesses in children and adolescents aged from 6 to 18 years |

| Ravens-Sieber et al., 2020 | Germany | 1586 parents | psychosomatic symptoms: irritability, sleeping problems, headache, feeling low, stomach ache |

| socially disadvantaged children felt particularly burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Orgiles et al., 2020 | Italy and Spain | 1143 parents of Italian and Spanish children aged 3–18 years | difficulty concentrating, boredom, irritability, restlessness, nervousness, feelings of loneliness, uneasiness, worries | internet survey | children suffering from pre-existing mental illnesses or other conditions require more support to deal with uncertainties and to tolerate negative feelings |

| Tang et al., 2021 | China | 4391 people aged 6–17 years | anxiety, depression, stress | internet survey |

|

| Liu et al., 2020 | China | n = 209 (primary school students (116 girls, 93 boys)) | somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression | somatic self-rating scale |

|

| Xie et al., 2020 | China | 2330 students | depression, anxiety |

|

|

| Zhou et al., 2020 | China | 8079 people aged 12–18 years | depression, anxiety | -PHQ-9 -GAD-7 |

|

| Jiao et al., 2020 | China | 320 children (168 girls, 142 boys) aged 3–18 | discomfort and agitation, nightmares, fatigue, poor appetite, sleeping disorders, fear for the health of relatives, obsessive request for updates, worry, irritability, inattention, clinginess | questionnaire was completed online by parents and incorporated DSM-5 criteria |

|

| Oosterhoff et al., 2020 | USA | 657 adolescents (13–18 years) | anxiety, depression | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): anxiety and depression scales | being female was a risk factor for higher rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms |

| Rosen et al., 2020 | USA | 303 parents, of which 45% had children under the age of 10 years (mean age: 43 years) | distress | researchers created questions about observation of child distress | greater symptoms of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents were related to financial stress in the family |

| Hawes et al., 2021 | USA | n = 451, ages 12–22 | depression, anxiety |

| female gender is a risk factor for higher rates of depression and anxiety symptoms |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Śniadach, J.; Szymkowiak, S.; Osip, P.; Waszkiewicz, N. Increased Depression and Anxiety Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents: A Literature Review. Life 2021, 11, 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11111188

Śniadach J, Szymkowiak S, Osip P, Waszkiewicz N. Increased Depression and Anxiety Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents: A Literature Review. Life. 2021; 11(11):1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11111188

Chicago/Turabian StyleŚniadach, Justyna, Sylwia Szymkowiak, Przemysław Osip, and Napoleon Waszkiewicz. 2021. "Increased Depression and Anxiety Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents: A Literature Review" Life 11, no. 11: 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11111188

APA StyleŚniadach, J., Szymkowiak, S., Osip, P., & Waszkiewicz, N. (2021). Increased Depression and Anxiety Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents: A Literature Review. Life, 11(11), 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11111188