Genome-Wide Scanning of Potential Hotspots for Adenosine Methylation: A Potential Path to Neuronal Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Definition of m6A Methylation Sites

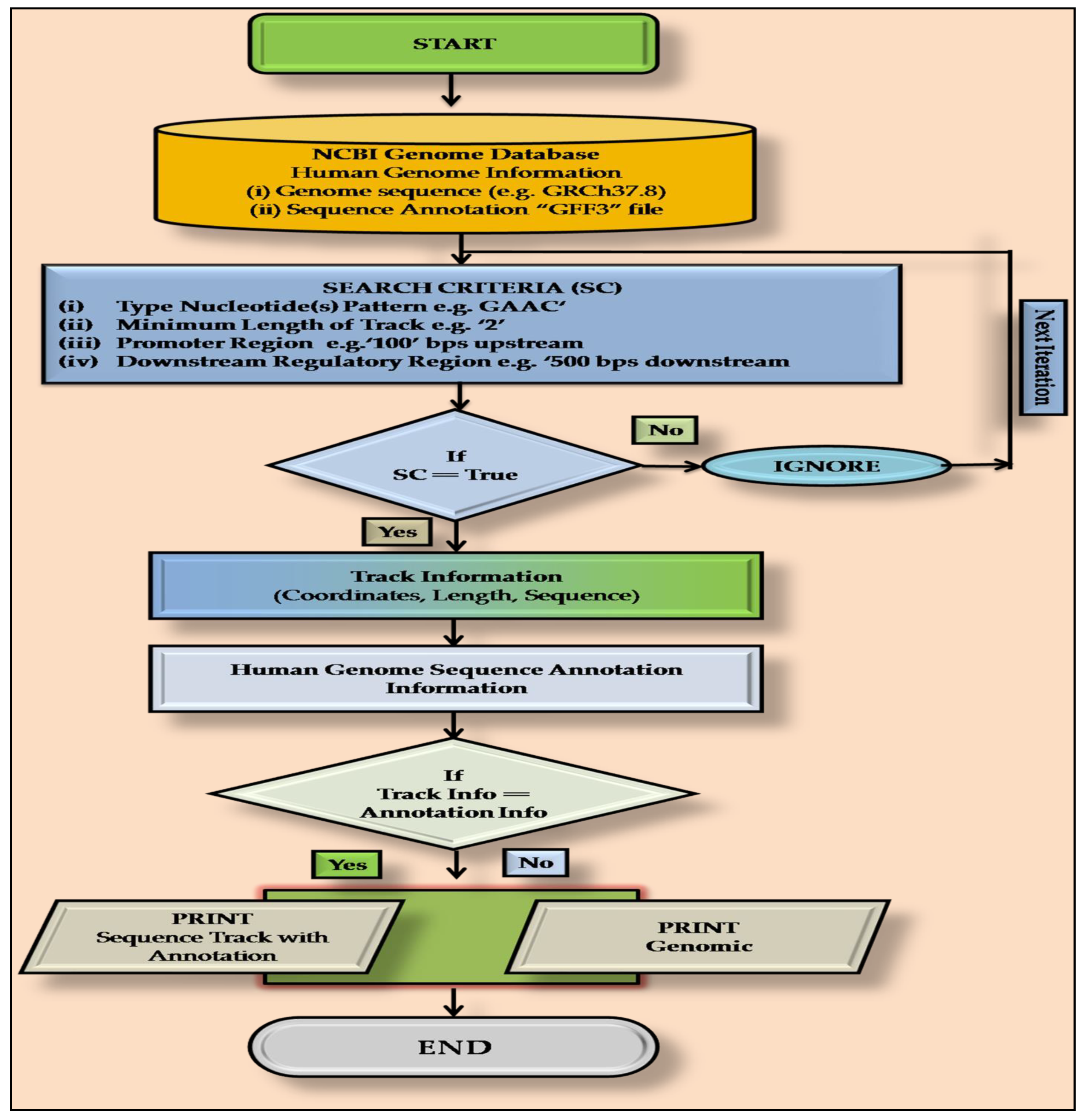

2.2. PatternRepeatAnnotator: A Home-Made PERL Script

2.3. Annotation of m6A Sites

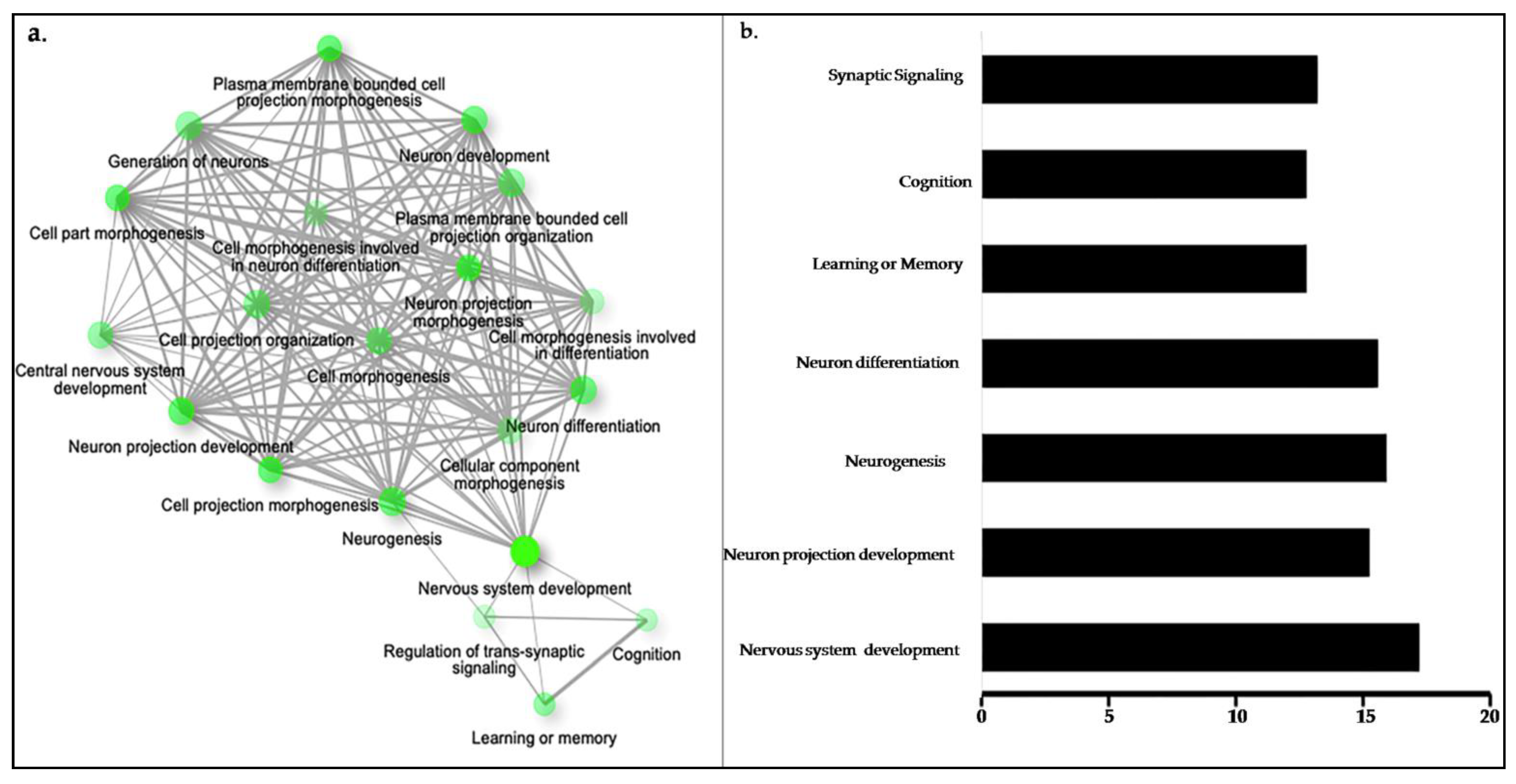

2.4. Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hussain, S.; Aleksic, J.; Blanco, S.; Dietmann, S.; Frye, M. Characterizing 5-Methylcytosine in the Mammalian Epitranscriptome. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, G.; Fu, Y.; He, C. Reversible RNA Adenosine Methylation in Biological Regulation. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bednářová, A.; Hanna, M.; Durham, I.; VanCleave, T.; England, A.; Chaudhuri, A.; Krishnan, N. Lost in Translation: Defects in Transfer RNA Modifications and Neurological Disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, W.; Ji, X.; Guo, X.; Ji, S. Regulatory Role of N6-Methyladenosine (M6A) Methylation in RNA Processing and Human Diseases. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 2534–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Zealy, R.W.; Davila, S.; Fomin, M.; Cummings, J.C.; Makowsky, D.; Mcdowell, C.H.; Thigpen, H.; Hafner, M.; Kwon, S.; et al. Profiling of M6A RNA Modifications Identified an Age-associated Regulation of AGO2 MRNA Stability. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitale, R.C.; Flynn, R.A.; Zhang, Q.C.; Crisalli, P.; Lee, B.; Jung, J.-W.; Kuchelmeister, H.Y.; Batista, P.J.; Torre, E.A.; Kool, E.T.; et al. Structural Imprints in Vivo Decode RNA Regulatory Mechanisms. Nature 2015, 519, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G.; Yu, M.; Lu, Z.; Deng, X.; et al. A METTL3-METTL14 Complex Mediates Mammalian Nuclear RNA N6-Adenosine Methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Linder, B.; Grozhik, A.V.; Olarerin-George, A.O.; Meydan, C.; Mason, C.E.; Jaffrey, S.R. Single-Nucleotide-Resolution Mapping of M6A and M6Am throughout the Transcriptome. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Lu, Z.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Luo, G.-Z.; Liu, N.; Han, D.; Dominissini, D.; Dai, Q.; Pan, T.; et al. High-Resolution N(6) -Methyladenosine (m(6) A) Map Using Photo-Crosslinking-Assisted m(6) A Sequencing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hengesbach, M.; Meusburger, M.; Lyko, F.; Helm, M. Use of DNAzymes for Site-Specific Analysis of Ribonucleotide Modifications. RNA 2008, 14, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Novoa, E.M.; Mason, C.E.; Mattick, J.S. Charting the Unknown Epitranscriptome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 339–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonkhout, N.; Tran, J.; Smith, M.A.; Schonrock, N.; Mattick, J.S.; Novoa, E.M. The RNA Modification Landscape in Human Disease. RNA 2017, 23, 1754–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delatte, B.; Wang, F.; Ngoc, L.V.; Collignon, E.; Bonvin, E.; Deplus, R.; Calonne, E.; Hassabi, B.; Putmans, P.; Awe, S.; et al. Transcriptome-Wide Distribution and Function of RNA Hydroxymethylcytosine. Science 2016, 351, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanbeer, S.K.; Ahmed, C.F.; Jeong, B.-S.; Lee, Y.-K. Sliding Window-Based Frequent Pattern Mining over Data Streams. Inf. Sci. 2009, 179, 3843–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.N.; Rajeswari, M.R. NTrackAnnotator: Software for Detection and Annotation of Sequence Tracks of Chosen Nucleic Acid Bases with Defined Length in Genome. Gene Rep. 2017, 7, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: A Graphical Gene-Set Enrichment Tool for Animals and Plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, B.; Nie, Z.; Duan, L.; Xiong, Q.; Jin, Z.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y. The Role of M6A Modification in the Biological Functions and Diseases. Sig. Transduct. Target. 2021, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livneh, I.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Amariglio, N.; Rechavi, G.; Dominissini, D. The M6A Epitranscriptome: Transcriptome Plasticity in Brain Development and Function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, H.; Temple, S. Cell Types to Order: Temporal Specification of CNS Stem Cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009, 19, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohi, K.; Shimada, T.; Nitta, Y.; Kihara, H.; Okubo, H.; Uehara, T.; Kawasaki, Y. Specific Gene Expression Patterns of 108 Schizophrenia-Associated Loci in Cortex. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 174, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.-J.; Ringeling, F.R.; Vissers, C.; Jacob, F.; Pokrass, M.; Jimenez-Cyrus, D.; Su, Y.; Kim, N.-S.; Zhu, Y.; Zheng, L.; et al. Temporal Control of Mammalian Cortical Neurogenesis by M6A Methylation. Cell 2017, 171, 877–889.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ke, S.; Pandya-Jones, A.; Saito, Y.; Fak, J.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Geula, S.; Hanna, J.H.; Black, D.L.; Darnell, J.E.; Darnell, R.B. M6A MRNA Modifications Are Deposited in Nascent Pre-MRNA and Are Not Required for Splicing but Do Specify Cytoplasmic Turnover. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, K.D.; Saletore, Y.; Zumbo, P.; Elemento, O.; Mason, C.E.; Jaffrey, S.R. Comprehensive Analysis of MRNA Methylation Reveals Enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near Stop Codons. Cell 2012, 149, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berulava, T.; Rahmann, S.; Rademacher, K.; Klein-Hitpass, L.; Horsthemke, B. N6-Adenosine Methylation in MiRNAs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón, C.R.; Lee, H.; Goodarzi, H.; Halberg, N.; Tavazoie, S.F. N6-Methyladenosine Marks Primary MicroRNAs for Processing. Nature 2015, 519, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, L.J.; Tan, Y.-X.; Ren, H.; Qi, Z.-T. Identification of Deregulated MiRNAs and Their Targets in Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 5442–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Song, X.; Xue, Z.; Zheng, C.; Yin, H.; Wei, H. Network Analysis of MicroRNAs, Transcription Factors, and Target Genes Involved in Axon Regeneration. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2018, 19, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachtler, J.; Glasper, J.; Cohen, R.N.; Ivorra, J.L.; Swiffen, D.J.; Jackson, A.J.; Harte, M.K.; Rodgers, R.J.; Clapcote, S.J. Deletion of α-Neurexin II Results in Autism-Related Behaviors in Mice. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Merkurjev, D.; Hong, W.-T.; Iida, K.; Oomoto, I.; Goldie, B.J.; Yamaguti, H.; Ohara, T.; Kawaguchi, S.; Hirano, T.; Martin, K.C.; et al. Synaptic N6-Methyladenosine (M6A) Epitranscriptome Reveals Functional Partitioning of Localized Transcripts. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1004–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; Bucci, C. Role of EGFR in the Nervous System. Cells 2020, 9, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoly, O.; Sato, T.; Tavassoly, I. Inhibition of Brain Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Activation: A Novel Target in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Brain Injuries. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020, 98, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Sui, N. Advances in the Profiling of N6-Methyladenosine (M6A) Modifications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 45, 107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Meng, J.; Su, R.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Ma, X.; Xia, Q. Epitranscriptomics in Liver Disease: Basic Concepts and Therapeutic Potential. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.-M.; Huo, F.-C.; Pei, D.-S. Function and Evolution of RNA N6-Methyladenosine Modification. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Cheng, Y.; Ye, S.; Zhang, J.; Huang, R.; Li, P.; Liu, H.; Deng, Q.; Wu, X.; Lan, P.; et al. M6A Methyltransferase METTL3 Suppresses Colorectal Cancer Proliferation and Migration through P38/ERK Pathways. Onco. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 4391–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, Q.; Rao, J.; Zhang, L.; Fu, B.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, J. The Study of METTL14, ALKBH5, and YTHDF2 in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells from Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020, 8, e1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakati, S.; Barman, B.; Ahmed, S.U.; Hussain, M. Neurological Manifestations in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Single Centre Study from North East India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, OC05–OC09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, F.-Y.; Lv, H.; Yang, Y.-H.; Zulfiqar, H.; Gao, H.; Lin, H. Computational Identification of N6-Methyladenosine Sites in Multiple Tissues of Mammals. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Begik, O.; Lucas, M.C.; Ramirez, J.M.; Mason, C.E.; Wiener, D.; Schwartz, S.; Mattick, J.S.; Smith, M.A.; Novoa, E.M. Accurate Detection of M6A RNA Modifications in Native RNA Sequences. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qiang, X.; Chen, H.; Ye, X.; Su, R.; Wei, L. M6AMRFS: Robust Prediction of N6-Methyladenosine Sites With Sequence-Based Features in Multiple Species. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, S.; Liu, K.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z. RNAMethPre: A Web Server for the Prediction and Query of MRNA M6A Sites. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.; Feng, P.; Yang, H.; Ding, H.; Lin, H.; Chou, K.-C. IRNA-AI: Identifying the Adenosine to Inosine Editing Sites in RNA Sequences. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 4208–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qiu, W.-R.; Xiao, X.; Chou, K.-C. IRSpot-TNCPseAAC: Identify Recombination Spots with Trinucleotide Composition and Pseudo Amino Acid Components. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 1746–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Xiao, X.; Qiu, W.-R.; Chou, K.-C. IDNA-Methyl: Identifying DNA Methylation Sites via Pseudo Trinucleotide Composition. Anal. Biochem. 2015, 474, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Tang, H.; Ye, J.; Lin, H.; Chou, K.-C. IRNA-PseU: Identifying RNA Pseudouridine Sites. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chromosome Number | Number of Target Sequence ×104 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter | DRR | Exon | Intron | Genomic | Total | |

| 1 | 1.00 | 4.17 | 22.08 | 289.36 | 202.29 | 518.90 |

| 2 | 1.46 | 6.23 | 31.76 | 541.57 | 433.78 | 1014.80 |

| 3 | 0.51 | 2.13 | 11.55 | 229.46 | 142.93 | 386.58 |

| 4 | 0.90 | 3.92 | 18.34 | 368.27 | 391.23 | 782.67 |

| 5 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 2.95 | 60.49 | 79.17 | 142.89 |

| 6 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 11.49 | 131.76 | 108.23 | 252.65 |

| 7 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 7.74 | 127.44 | 108.97 | 244.86 |

| 8 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 6.31 | 103.02 | 79.42 | 189.34 |

| 9 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 2.29 | 56.21 | 50.51 | 109.22 |

| 10 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 4.89 | 91.10 | 69.49 | 165.92 |

| 11 | 1.16 | 4.89 | 23.13 | 293.85 | 238.57 | 561.61 |

| 12 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 5.90 | 82.65 | 55.61 | 144.66 |

| 13 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 9.64 | 183.52 | 205.59 | 399.72 |

| 14 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 13.88 | 194.32 | 168.73 | 378.41 |

| 15 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 15.63 | 208.53 | 129.65 | 355.11 |

| 16 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 8.76 | 88.48 | 59.10 | 157.08 |

| 17 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 6.60 | 57.25 | 34.28 | 98.67 |

| 18 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 2.06 | 34.53 | 27.32 | 64.10 |

| 19 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 9.38 | 61.79 | 37.57 | 109.54 |

| 20 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 3.66 | 56.90 | 50.03 | 110.93 |

| 21 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 4.74 | 64.69 | 79.52 | 149.41 |

| 22 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 9.70 | 93.20 | 54.50 | 158.26 |

| 23 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 6.19 | 105.08 | 135.69 | 247.54 |

| 24 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 10.31 | 29.93 | 41.29 |

| Total | 11.68 | 27.23 | 239.34 | 3533.78 | 2972.11 | 6784.16 |

| Percentage of Total | 0.172 | 0.401 | 3.528 | 52.089 | 43.810 | 100.000 |

| Chromosome | Chromosome Size (Mb) | Total No. Protein Coding Genes Present | Number of Protein Coding Genes Carrying Target Sequence (%) | Highest Frequency of Target Sequence in Any Gene | # Enrichment Score × 104 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 249 | 2058 | 967 (27) | 63 | 2.08 |

| 2 | 242 | 1309 | 1448 (67) | 58 | 4.19 |

| 3 | 198 | 1078 | 522 (30) | 62 | 1.95 |

| 4 | 190 | 752 | 932 (76) | 55 | 4.11 |

| 5 | 182 | 876 | 135 (10) | 64 | 0.79 |

| 6 | 171 | 1048 | 497 (26) | 32 | 1.48 |

| 7 | 159 | 989 | 352 (21) | 51 | 1.54 |

| 8 | 145 | 677 | 286 (25) | 73 | 1.30 |

| 9 | 138 | 786 | 99 (8) | 88 | 0.79 |

| 10 | 134 | 733 | 226 (18) | 43 | 1.24 |

| 11 | 135 | 1298 | 982 (42) | 73 | 4.16 |

| 12 | 133 | 1034 | 265 (14) | 36 | 1.09 |

| 13 | 114 | 327 | 432 (81) | 163 | 3.50 |

| 14 | 107 | 830 | 587 (40) | 74 | 3.54 |

| 15 | 102 | 613 | 641 (64) | 40 | 3.48 |

| 16 | 90 | 873 | 343 (19) | 108 | 1.74 |

| 17 | 83 | 1197 | 261 (12) | 21 | 1.19 |

| 18 | 80 | 270 | 92 (18) | 35 | 0.80 |

| 19 | 59 | 1472 | 361 (13) | 12 | 1.87 |

| 20 | 64 | 544 | 169 (20) | 69 | 1.72 |

| 21 | 47 | 234 | 212 (56) | 47 | 3.20 |

| 22 | 51 | 488 | 39 (44) | 34 | 3.11 |

| 23 | 156 | 842 | 238 (17) | 80 | 1.59 |

| 24 | 57 | 71 | 42 (24) | 14 | 0.72 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, S.; Tsai, L.-W.; Kumar, P.; Dubey, R.; Gupta, D.; Singh, A.K.; Swarup, V.; Singh, H.N. Genome-Wide Scanning of Potential Hotspots for Adenosine Methylation: A Potential Path to Neuronal Development. Life 2021, 11, 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11111185

Kumar S, Tsai L-W, Kumar P, Dubey R, Gupta D, Singh AK, Swarup V, Singh HN. Genome-Wide Scanning of Potential Hotspots for Adenosine Methylation: A Potential Path to Neuronal Development. Life. 2021; 11(11):1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11111185

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Sanjay, Lung-Wen Tsai, Pavan Kumar, Rajni Dubey, Deepika Gupta, Anjani Kumar Singh, Vishnu Swarup, and Himanshu Narayan Singh. 2021. "Genome-Wide Scanning of Potential Hotspots for Adenosine Methylation: A Potential Path to Neuronal Development" Life 11, no. 11: 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11111185