Abstract

The Hesperornithiformes constitute the first known avian lineage to secondarily lose flight in exchange for the evolution of a highly derived foot-propelled diving lifestyle, thus representing the first lineage of truly aquatic birds. First unearthed in the 19th century, and today known from numerous Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Maastrichtian) sites distributed across the northern hemisphere, these toothed birds have become icons of early avian evolution. Initially erected as a taxon in 1984 by L. D. Martin, Parahesperornis alexi is known from the two most complete hesperornithiform specimens discovered to date and has yet to be fully described. P. alexi thus contributes significantly to our understanding of hesperornithiform birds, despite often being neglected in favor of the iconic Hesperornis. Here, we present a full anatomical description of P. alexi based upon the two nearly complete specimens in the collections of the University of Kansas Natural History Museum, as well as an extensive comparison to other hesperornithiform taxa. This study reveals P. alexi to possess a mosaic of basal and derived traits found among other hesperornithiform taxa, indicating a transitional form in the evolution of these foot-propelled diving birds. This study describes broad evolutionary patterns within the Hesperornithiformes, highlighting the significance of these birds as not only an incredible example of the evolution of ecological specializations, but also for understanding modern bird evolution, as they are the last known divergence of pre-modern bird diversification.

1. Introduction

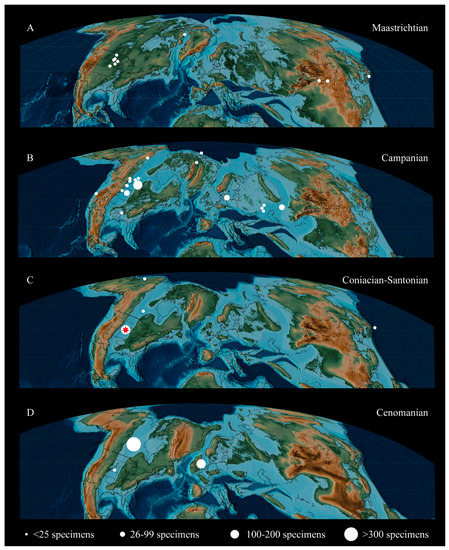

The Hesperornithiformes, a group of foot-propelled diving birds from the Cretaceous, constitute a highly specialized lineage of birds outside Neornithes and the earliest to become fully adapted for living in the marine realm. Despite being one of the better-known clades of early birds, the Hesperornithiformes (sometimes referred to as Hesperornithes [1,2]) suffer from a historic dearth of detailed anatomical research. First identified in the late 1800s in a series of short papers [3,4,5,6] and one monograph [7], subsequent research was primarily focused on brief descriptions of new fossil discoveries (for example [8,9,10,11,12]) or the relationships of the group to modern birds (for example [13,14,15]). Only recently have more comprehensive studies emerged assessing the systematics [12,16] or ecology [17,18] of the Hesperornithiformes, and only certain species have been subject to thorough study (for example, Hesperornis regalis [7]; Baptornis advenus [19]; Fumicollis hoffmani [20]). Today, hesperornithiforms have a fossil record that extends throughout the Late Cretaceous across Laurasia (Figure 1).

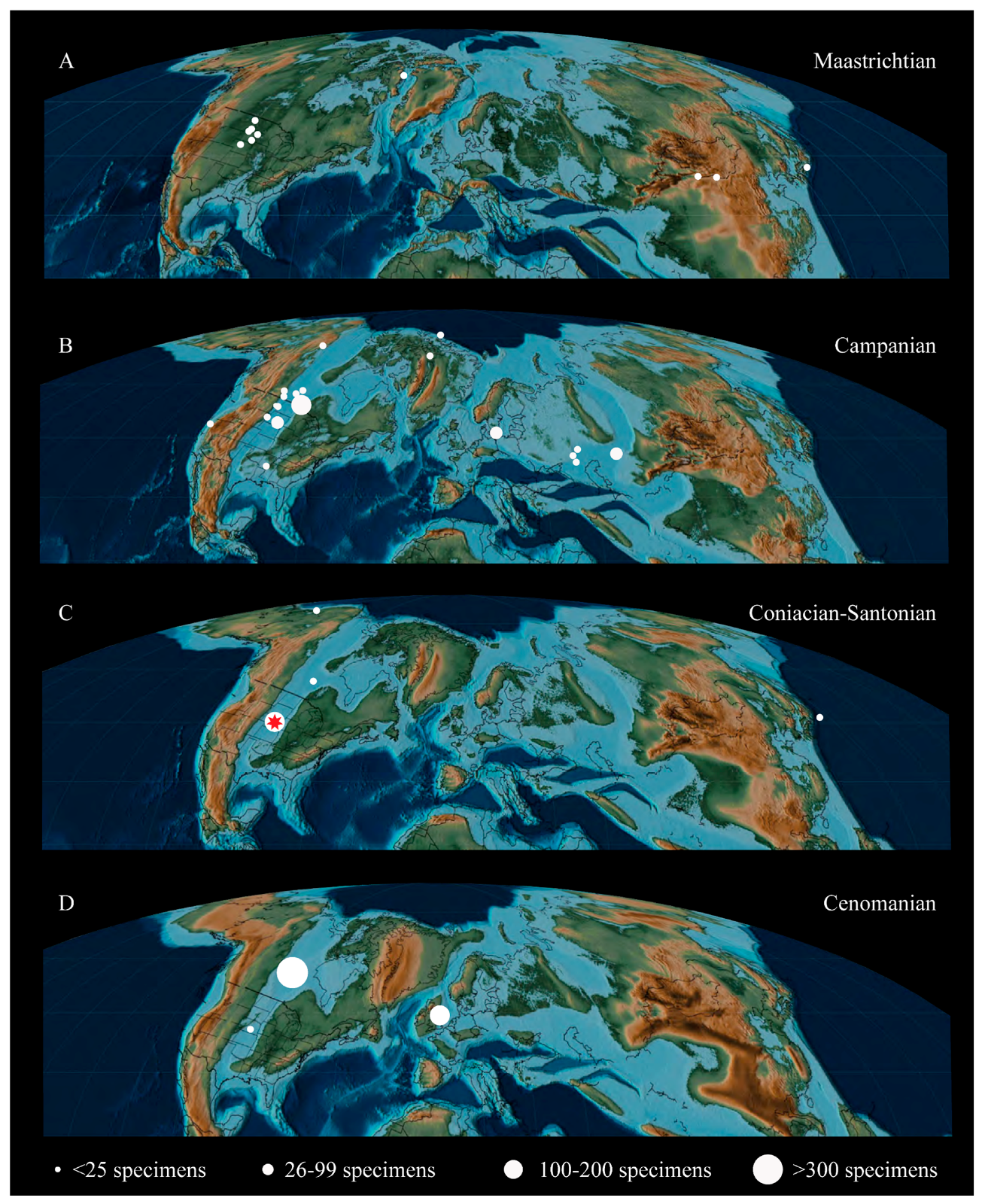

Figure 1.

Global distribution of hesperornithiform localities, scaled to approximate number of specimens documented in the literature [3,5,6,7,8,9,10,12,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] and museum collections, mapped on paleogeographic reconstructions of the Cretaceous [52].

The history of the study of Parahesperornis alexi, a medium-sized hesperornithiform from the Smoky Hill Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation (late Coniacian to early Campanian, USA) of western Kansas, is illustrative of the lack of detailed studies of the morphology of these early birds. The holotype of Parahesperornis alexi, University of Kansas Museum of Natural History (KUVP) specimen KUVP 2287, was discovered in 1894 but not described until 1984, when L. D. Martin published a brief report presenting a sample of the unique morphological features of this bird and identifying it as an evolutionary intermediate between Hesperornis and Baptornis [40].

The time lag between the discovery of KUVP 2287 and its identification as a new taxon may be due to the misidentification of the specimen by Williston [53,54], who assigned it to Hesperornis gracilis. H. gracilis was described by Marsh [5] from an isolated tarsometatarsus (Yale Peabody Museum [YPM] specimen YPM 1473), which is only slightly smaller than H. regalis and largely similar in overall morphology. It is unclear how Williston identified KUVP 2287 as “possibly [being] identical to H. gracilis” [53], as KUVP 2287 is notably smaller than H. gracilis and differs markedly in the morphology of the distal tarsometatarsus. Following this mistaken identification, Lucas [13] erroneously used features of KUVP 2287 to erect a new genus, Hargeria, to which he reassigned Hesperornis gracilis, stating that the differences between H. gracilis (based on KUVP 2287) and H. regalis were great enough to warrant generic distinction. Comparison of YPM 1473 to KUVP 2287 reveals that the two specimens are clearly dissimilar, and KUVP 2287 is in no way assignable to H. gracilis, thus invalidating Lucas’s creation of Hargeria [26,40], as per the ICZN’s code (Article 49) [55].

While Martin’s [40] original note erecting Parahesperornis alexi indicated additional work was forthcoming, the full description was never completed. Several papers referred to the skull of KUVP 2287 in analyses of the hesperornithiform skull [56,57], often with the erroneous identification of H. gracilis [13,58,59], and so a full description of the skull was never undertaken. A single paper [26] reporting the discovery of an isolated tarsometatarsus (Sternberg Museum of Natural History (FHSM) specimen FHSM VP-17312) assigned to Parahesperornis is the only other work that was published on this genus since Martin’s [40] work. Therefore, this study presents the first detailed anatomical analysis of Parahesperornis alexi based upon the holotype specimen, KUVP 2287, as well as a second exceptionally preserved specimen, KUVP 24090, that has not been previously published.

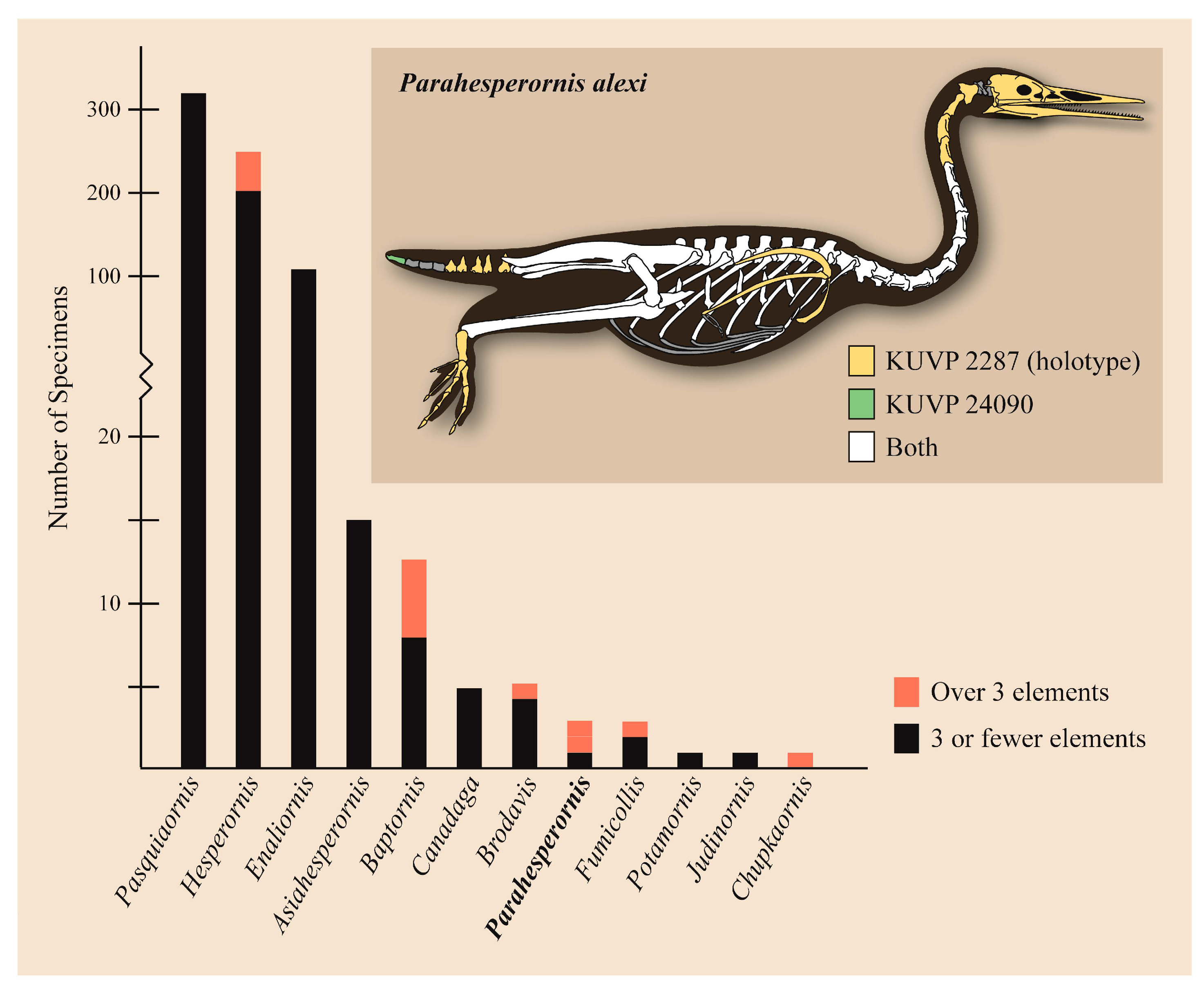

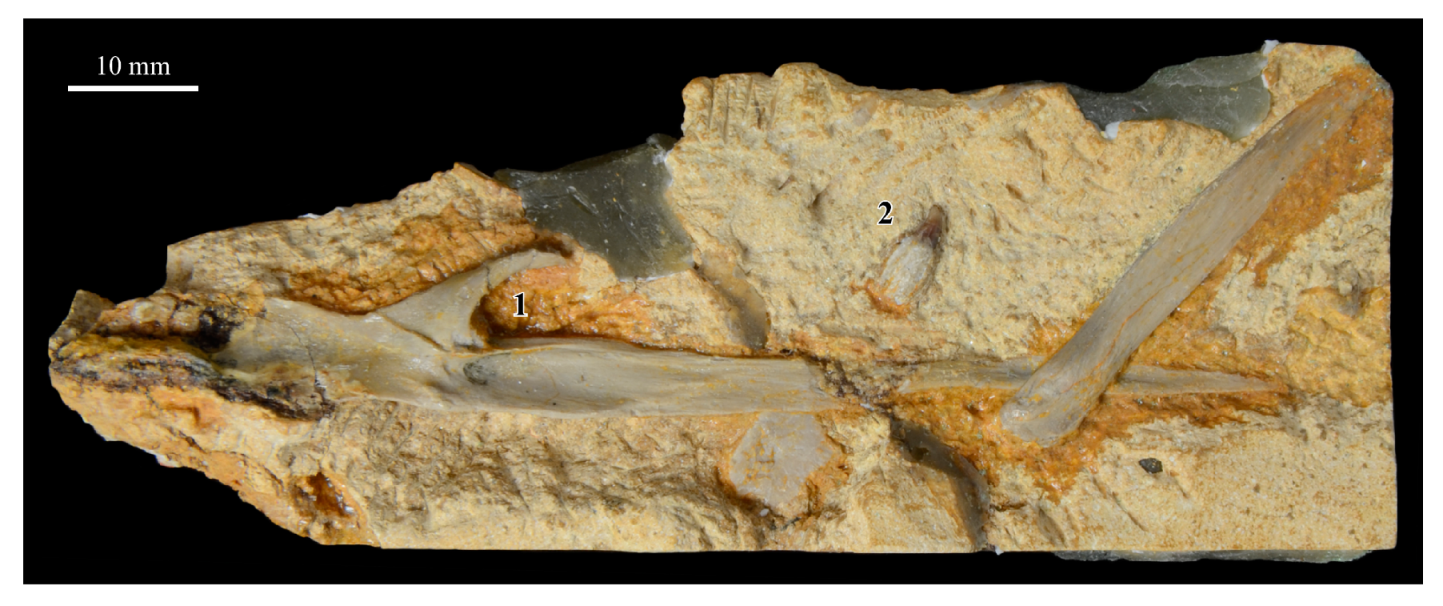

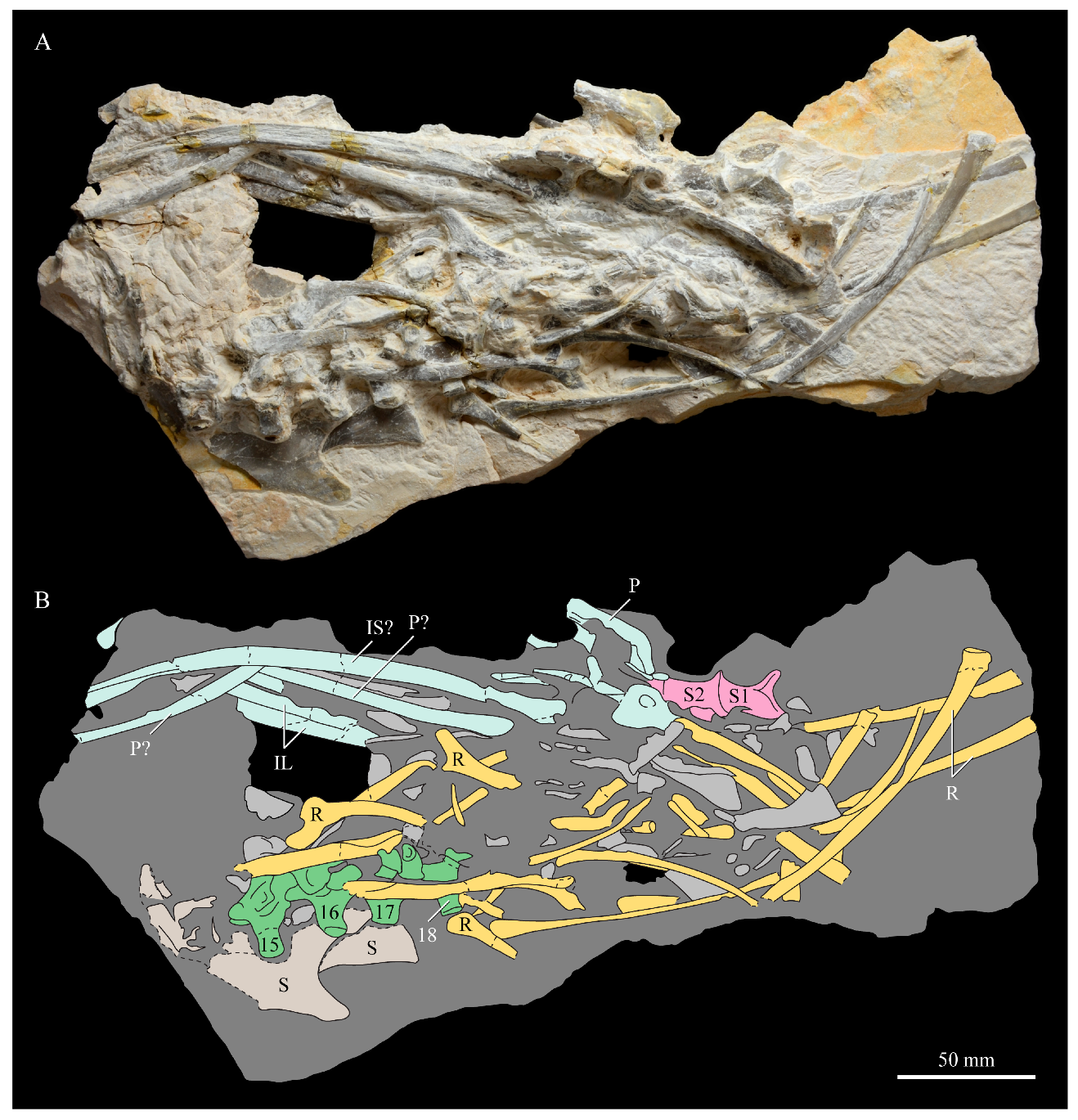

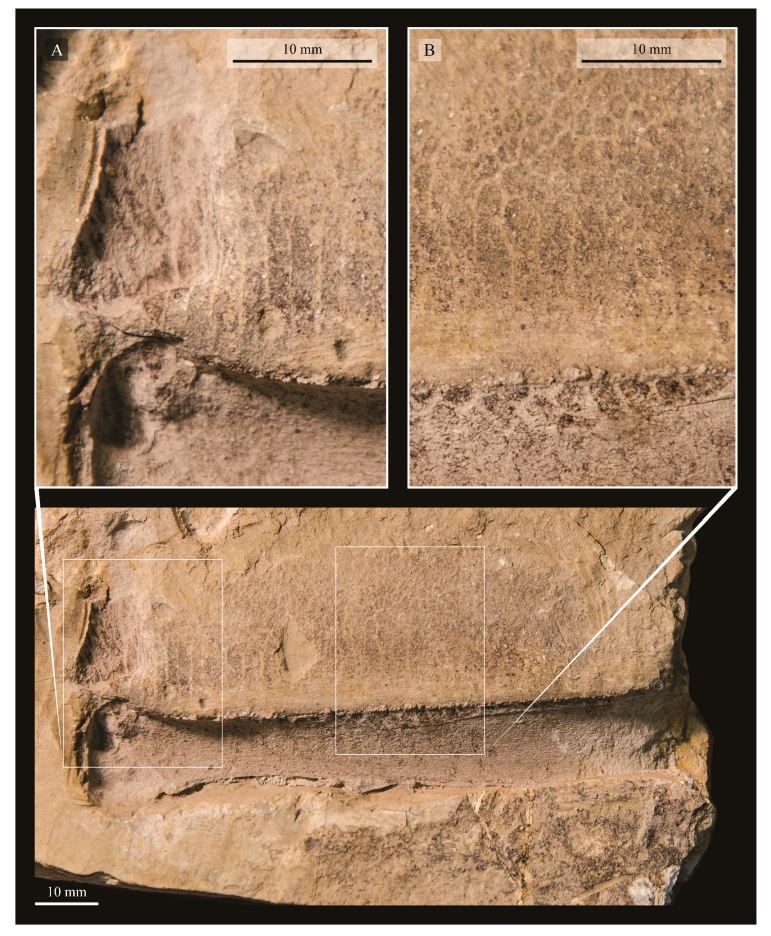

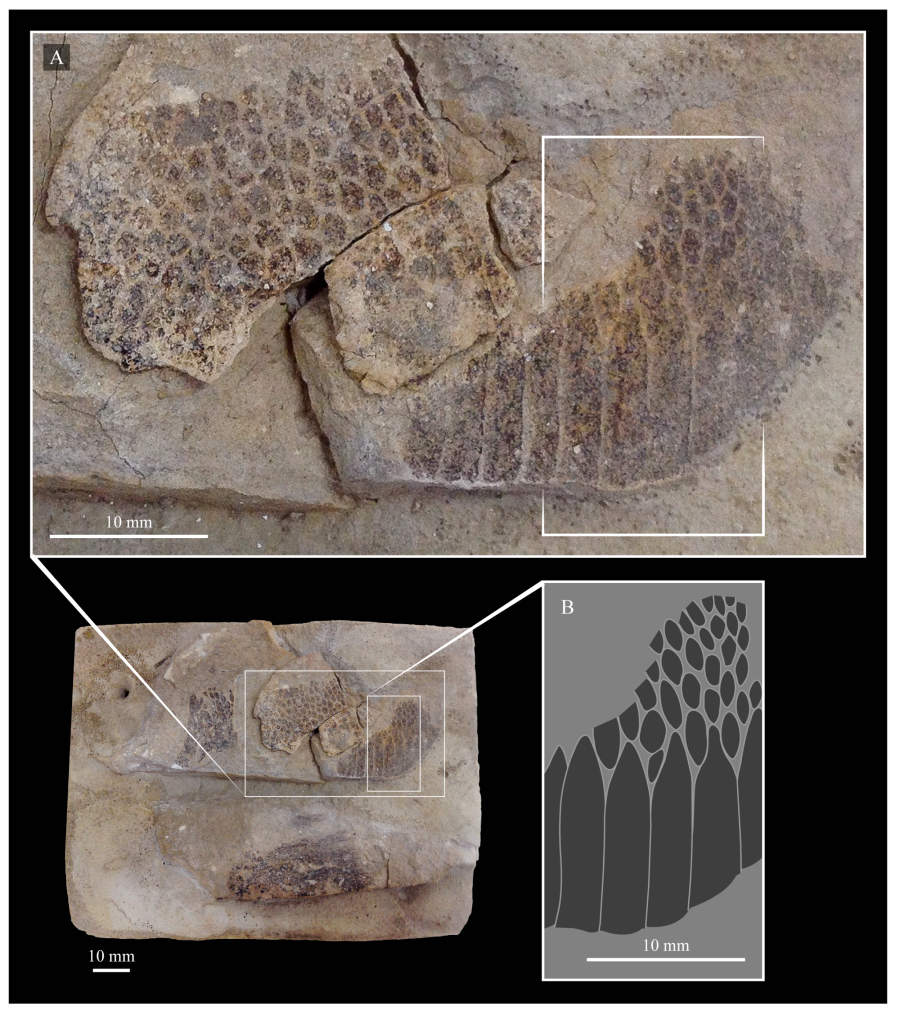

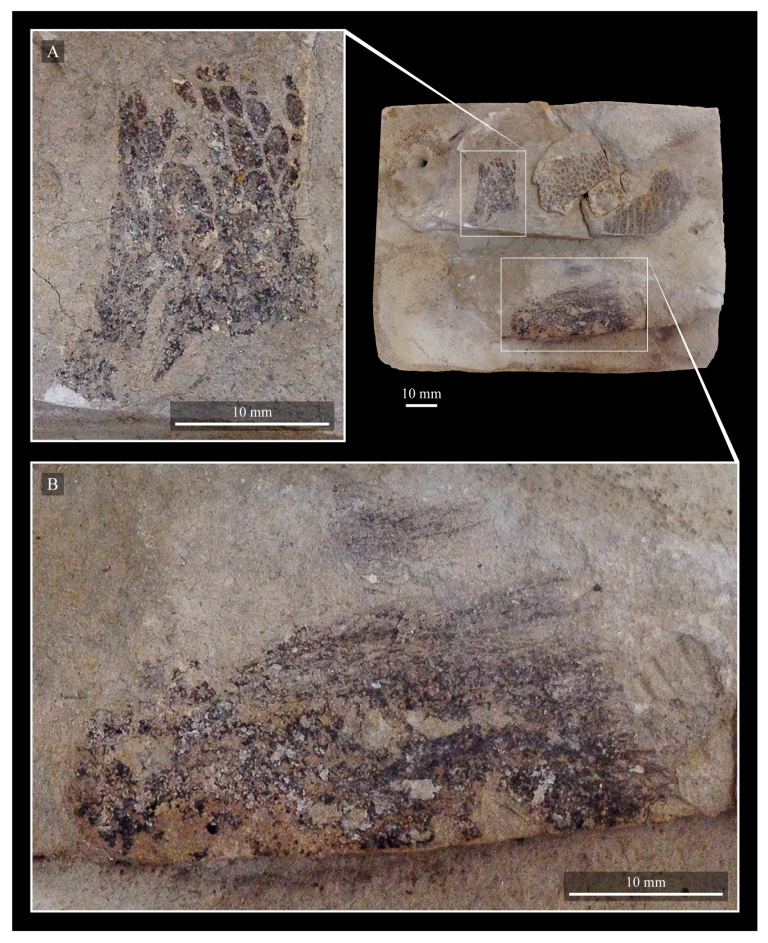

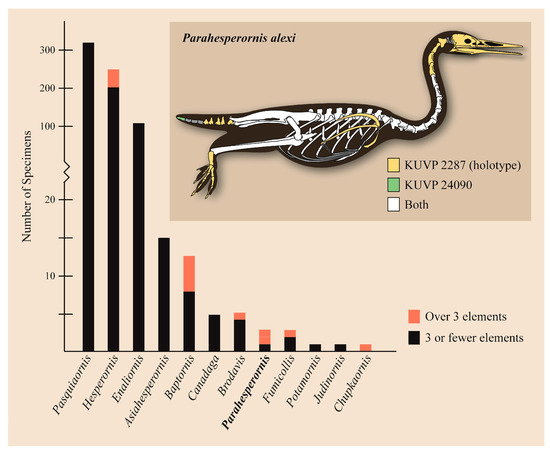

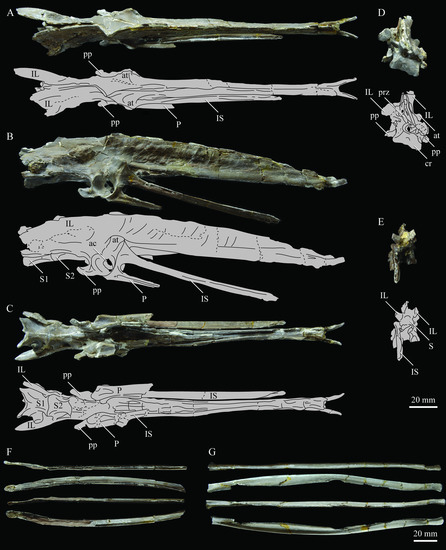

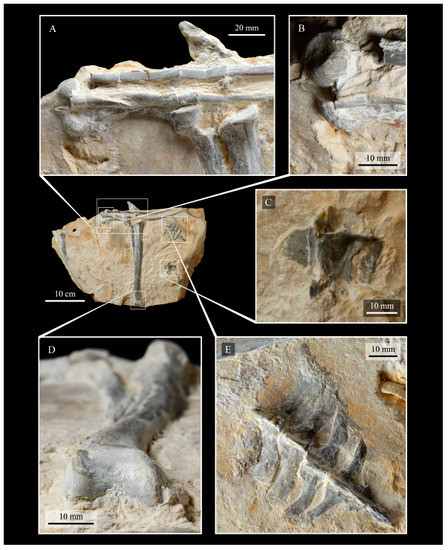

These two specimens are particularly important considering typical hesperornithiform fossil specimens, which are often highly fragmentary, isolated elements. Of the over twenty hesperornithiform species that have been described, only four have assigned specimens consisting of more than three elements. Of these four species, only two have any specimens that are over 50% complete. One of these is the type species of the family Hesperornithidae, Hesperornis regalis, and the other is Parahesperornis alexi. While Hesperornis has been extensively studied and is very well known in the scientific literature, Parahesperornis has been neglected. As a result, two of the best preserved hesperornithiform specimens, KUVP 2287 and KUVP 24090, have never been fully described or illustrated in the literature. Between these two specimens, almost the entire skeleton of Parahesperornis alexi is known, as well as impressions of the skin of the foot of this bird, thus rendering a great deal of anatomical information about these highly specialized, extinct birds (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Completeness of hesperornithiform specimens. Inset shows reconstruction of Parahesperornis alexi, with elements known from KUVP 2287 (yellow), KUVP 24090 (green), and both specimens (white) shaded.

This monograph is dedicated to the late L. D. Martin, whose studies on hesperornithiforms contributed greatly to reigniting scientific interest in these fascinating birds, and who generously spent time in discussion of these birds with one of the authors (A. Bell) during her many research trips to the University of Kansas.

Phylogenetic Relationships

In Martin’s [40] original work on Parahesperornis alexi he identified the species as an evolutionary intermediate between Baptornis and Hesperornis. Martin [40] based his conclusion on advanced toe rotation, as indicated by the similar morphology of the metatarsal trochleae in Hesperornis and Parahesperornis, and an interpreted lack of fusion between the frontals and parietals of Parahesperornis, a condition assumed to be more primitive than the fused condition seen in Hesperornis. However, Martin’s analysis was not a quantitative evaluation of a character matrix, as we understand phylogenetics today, but rather an anecdotal hypothesis based on a few observed features.

It was only more recently that Parahesperornis was included in modern phylogenetic analyses. First, an analysis examining relationships among the major clades of Mesozoic birds was presented by O’Connor et al. [60] This study found Parahesperornis to be the sister taxon to Hesperornis, forming the most derived clade of hesperornithiforms, a position supported by later analyses [12,16].

Within Ornithuromorpha, the Hesperornithiformes is consistently recovered as a monophyletic clade close to crown birds [2,12,16,60,61]. However, some studies recover the Hesperornithiformes as more closely related to Neornithes than is Ichthyornis [16,60,61,62,63], but others recover the Hesperornithiformes as the sister clade to Neornithes+Ichthyornis [2,12,64]. Agreement between analyses based on newly recovered material of Ichthyornis [61], and those designed to assess the placement of the Hesperornithiformes in particular amongst other Ornithuromorphs [16,60] provides strong support for interpreting the Hesperornithiformes as the closest outgroup of modern birds. As such, they are essential to understanding the origin of Neornithes. While much work has been done focusing on the highly derived diving adaptations of these birds, as a group they are also broadly relevant to our understanding of the evolution of modern birds.

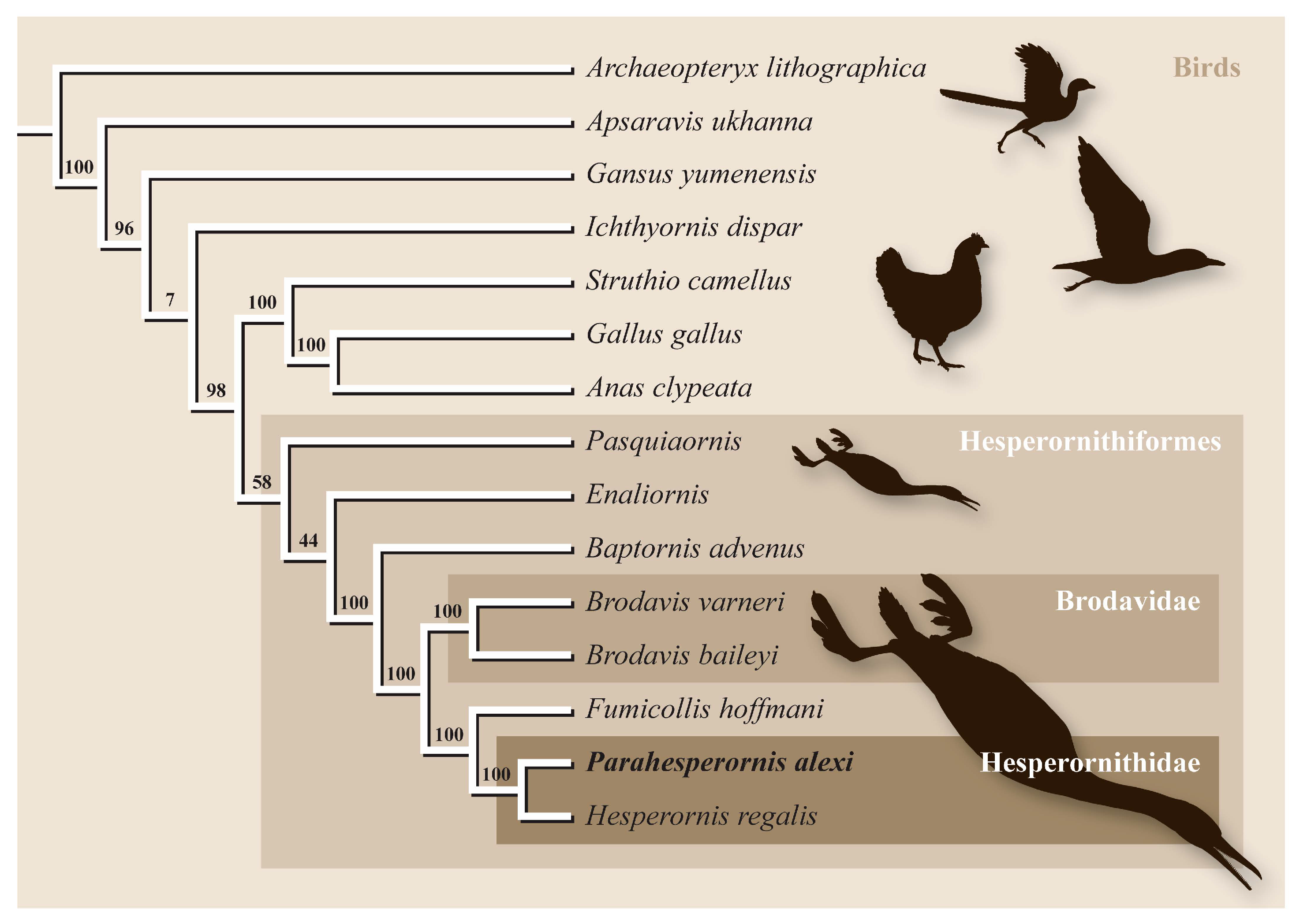

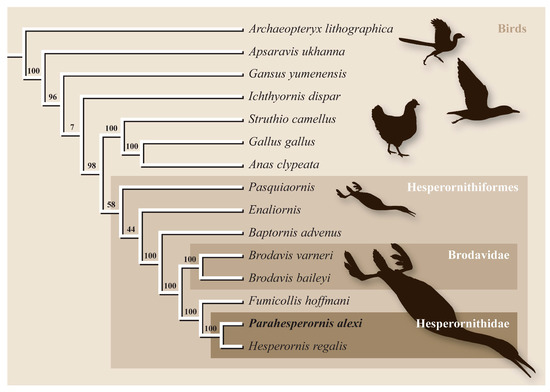

Bell and Chiappe [16] presented the first comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the Hesperornithiformes, confirming a monophyletic Hesperornithidae containing Parahesperornis and Hesperornis united by 28 unambiguous synapomorphies [16] (Figure 3). This has since been supported by further analysis [12]. Within the Hesperornithiformes, Bell and Chiappe [16] recovered two monophyletic clades: the monogeneric Brodavidae, originally erected by Martin et al. [30] and containing four species (B. americanus, B. baileyi, B. mongoliensis, and B. varneri), and the Hesperornithidae, which at the time of this study contains four genera: Hesperornis (containing eleven species) and the monospecific Parahesperornis, Asiahesperornis, and Canadaga. While the family Baptornithidae has been proposed [19], containing Baptornis and Pasquiaornis [29,65], phylogenetic analyses consistently reject this family as a monophyletic clade [12,16].

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree from the analysis of Bell and Chiappe [16]. Numbers at nodes indicate bootstrap supports.

Bell and Chiappe [16] also identified Fumicollis hoffmani as the sister-taxon to the Hesperornithidae, a placement confirmed by subsequent analysis [12], making it the most-derived hesperornithiform outside of the Hesperornithidae. Disagreement exists over the placement of basal hesperornithiforms, including Baptornis, Enaliornis, and Pasquiaornis. For example, in studies in which both taxa are included, the basal-most hesperornithiform is recovered as either Pasquiaornis [16] or Enaliornis [12]. Given the highly fragmentary and problematic taxonomy of these two genera (see Methods below), this disagreement among studies is unsurprising. It should be noted that placement of these taxa is based on the coding of a very few characters. For example, the thoracic vertebrae of Enaliornis have been variously described as biconcave [3], amphicoelous [19], not fully heterocoelous [12], and fully heterocoelous [21,65,66]. This discrepancy is likely due to the high degree of weathering of these reworked specimens. A similar situation is involved with the vertebrae of Pasquiaornis [12,65]. Given the limited number of characters involved and the nature of the specimens, further work on both the taxonomy and phylogenetic positions of these taxa is warranted but may be limited to the discovery of more complete fossil material.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is based on a broad collection of Mesozoic bird fossils, primarily hesperornithiform, either studied directly in museum collections or from published descriptions in the scientific literature. As described above, the majority of hesperornithiform fossils consist of isolated elements. This can lead to difficulties in assigning different isolated elements to a single genus or species. Two such problematic hesperornithiform taxa are Enaliornis, with three species, and Pasquiaornis, with two species. Species designations for these genera are made primarily on the basis of size [3,21,29]. Both of these genera are described from large numbers of entirely isolated elements in bone bed deposits [3,29], making the assignment of different elements to the same genus problematic. For this reason, comparisons in the present study are primarily made between genera and not to the species level. Brodavis is one exception, as B. varneri consists of a multi-element holotype which varies substantially from the other species in the genus in a number of ways [30].

Anatomical nomenclature primarily follows Baumel and Witmer [67], with exceptions as noted in the text. Most specimens were measured using digital calipers, however where specimens could not be accessed measurements were collected from published photos using ImageJ (see Table S1 for details). Specimen numbers are used throughout to denote the source of specific observations. All specimens used in this study are held at federally recognized repositories and available for public access (see Table S2 for details). Institutional abbreviations are as follows: AMNH, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA; BMNH, The Natural History Museum, London, UK; FHSM, Sternberg Museum of Natural History, Fort Hays, KS, USA; FMNH, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA; IZASK, Institute of Zoology, Ministry of Science, Almaty, Kazakhstan; KUVP, University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Lawrence, KS, USA; LACM, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, USA; MCM, Mikasa City Museum, Mikasa, Japan; RSM, Royal Saskatchewan Museum, Regina, SK, Canada; NMC, Canada Museum of Nature, Ottawa, ON, Canada; NUVF—Nunavut Vertebrate Fossil collection (housed at the NMC); SDSM, Museum of Geology, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Rapid City, SD, USA; SMC, Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, The University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK; UNSM, University of Nebraska State Museum, Lincoln, NE, USA; USNM, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, USA; YPM, Yale Peabody Museum, New Haven, CT, USA; YPM PU, Princeton University (collections now housed in the Yale Peabody Museum); ZIN PO, Paleornithological Collection of the Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Paleontology

- Aves Linnaeus 1758Ornithuromorpha Chiappe 1995Ornithurae Haeckel 1866Hesperornithiformes Furbringer 1888Hesperornithidae emend.

The term “hesperornithidae” is generally attributed to Marsh [4], however in the referenced paper he used the term “hesperornidae”, not “hesperornithidae”. Marsh [5] later used the term “hesperornithidae” when describing Lestornis crassipes (later reassigned as Hesperornis crassipes [7]). A phylogenetic definition for the clade was later formalized by Clarke [2], who defined Hesperornithidae as a stem-based name containing all taxa more closely related to Hesperornis regalis than to Baptornis advenus. Phylogentic and taxonomic work by Bell and Chiappe [16,20] has since identified additional taxa intermediate to B. advenus and H. regalis not suitable for inclusion in the Hesperornithidae. Therefore, we are revising the name Hesperornithidae to a node-based definition containing all descendants of the common ancestor of Hesperornis regalis and Parahesperornis alexi. At the time of writing, that would include Asiahesperornis bazhanovi and Canadaga arctica, as well as Parahesperornis alexi and all species of Hesperornis, but would exclude the less derived Fumicollis hoffmani.

- Parahesperornis Martin 1984

Type Species: Parahesperornis alexi

Included Species: Parahesperornis alexi

3.1.1. Original Diagnosis

From Martin [40], “Skull mesokinetic; lacrimal more elongated dorsoventrally than in Hesperornis; nasal process of lacrimal more extended anteriorly than in Hesperornis; orbital process of quadrate very elongate; coracoid more elongate than in Hesperornis; femur more elongate and the proximal end less extended laterally than in Hesperornis and the tibiotarsus less compressed; tarsometatarsus with the outer trochlea only about one-quarter larger than the middle trochlea and both at about the same level distally (outer trochlea nearly twice the size of the inner trochlea and more distally situated in Hesperornis); crescent and peg articulations developed on the phalanges of the fourth toe of the foot as in other hesperornithids (absent in the baptornithids)” (p. 143).

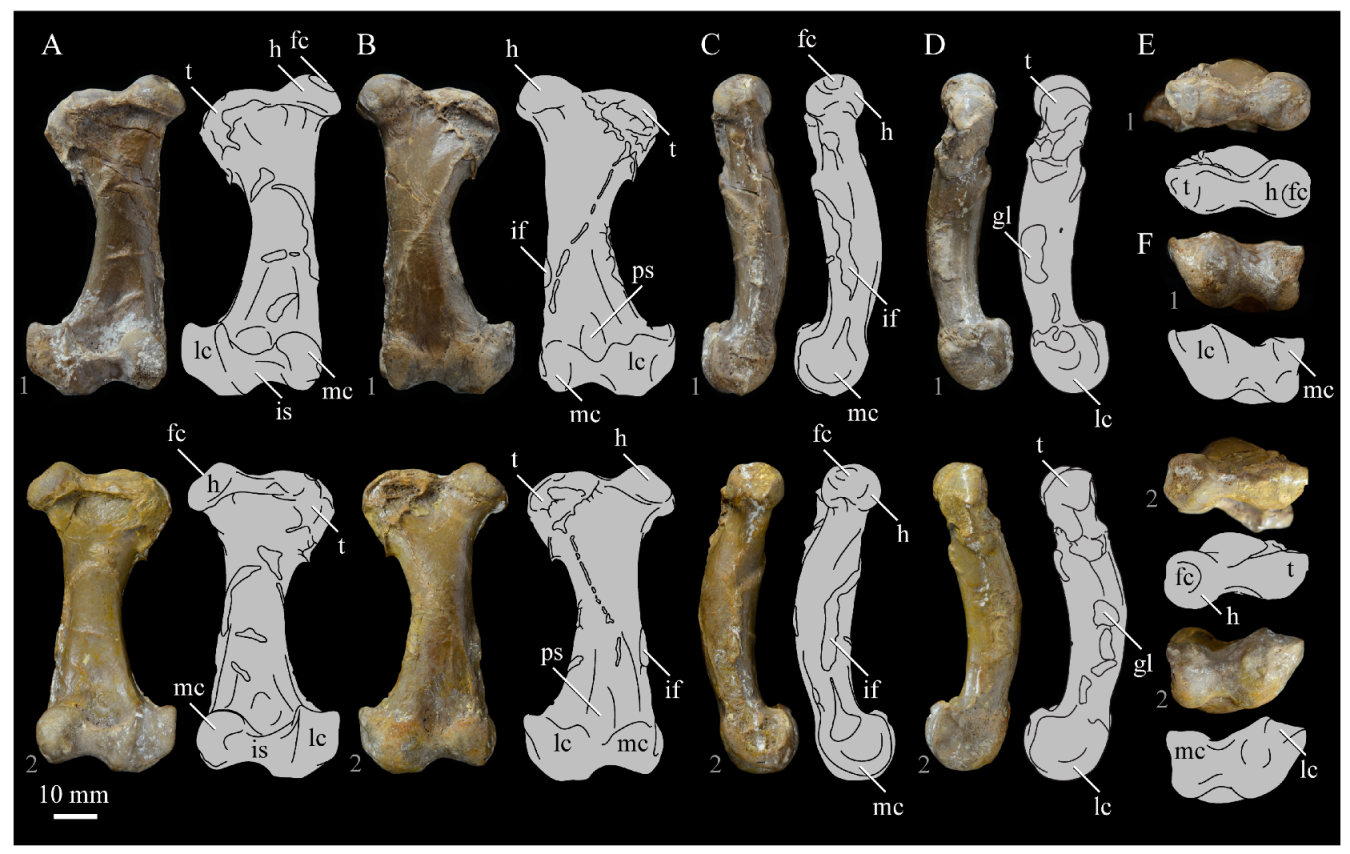

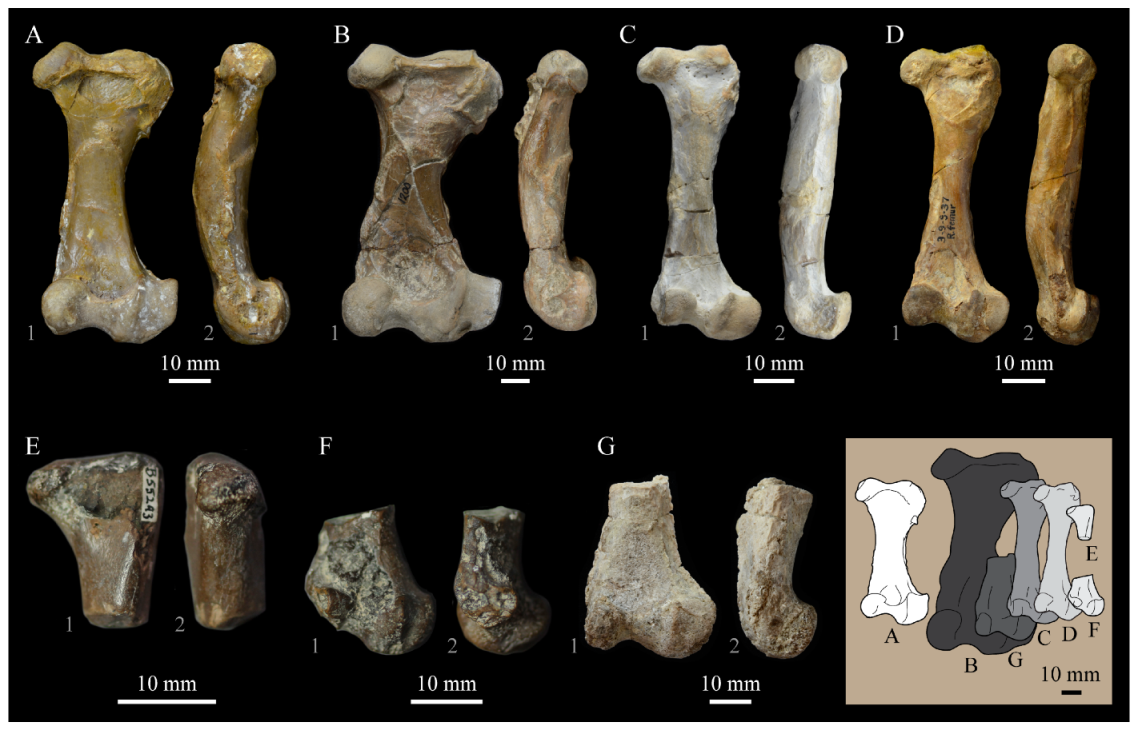

3.1.2. Amended Diagnosis

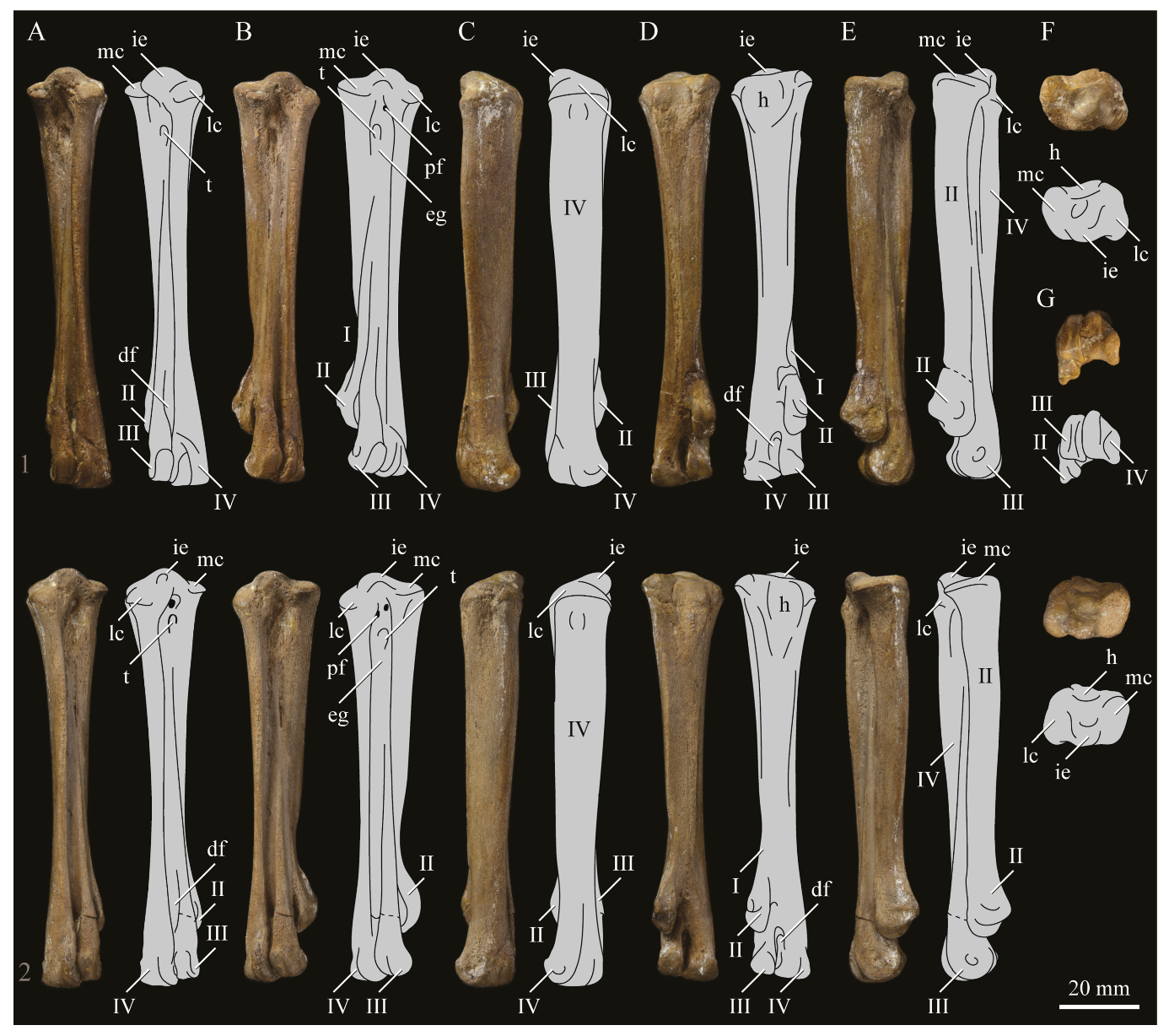

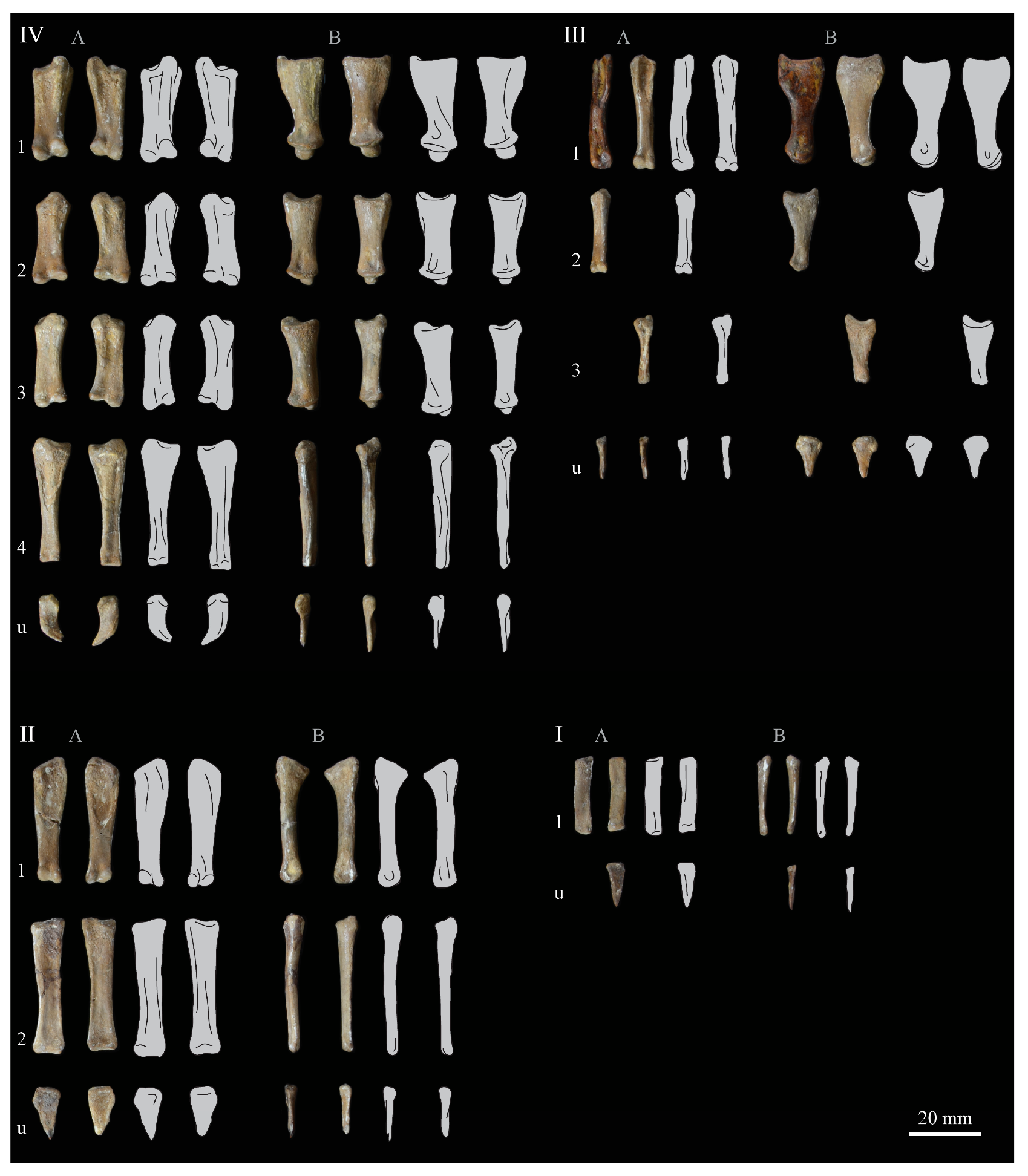

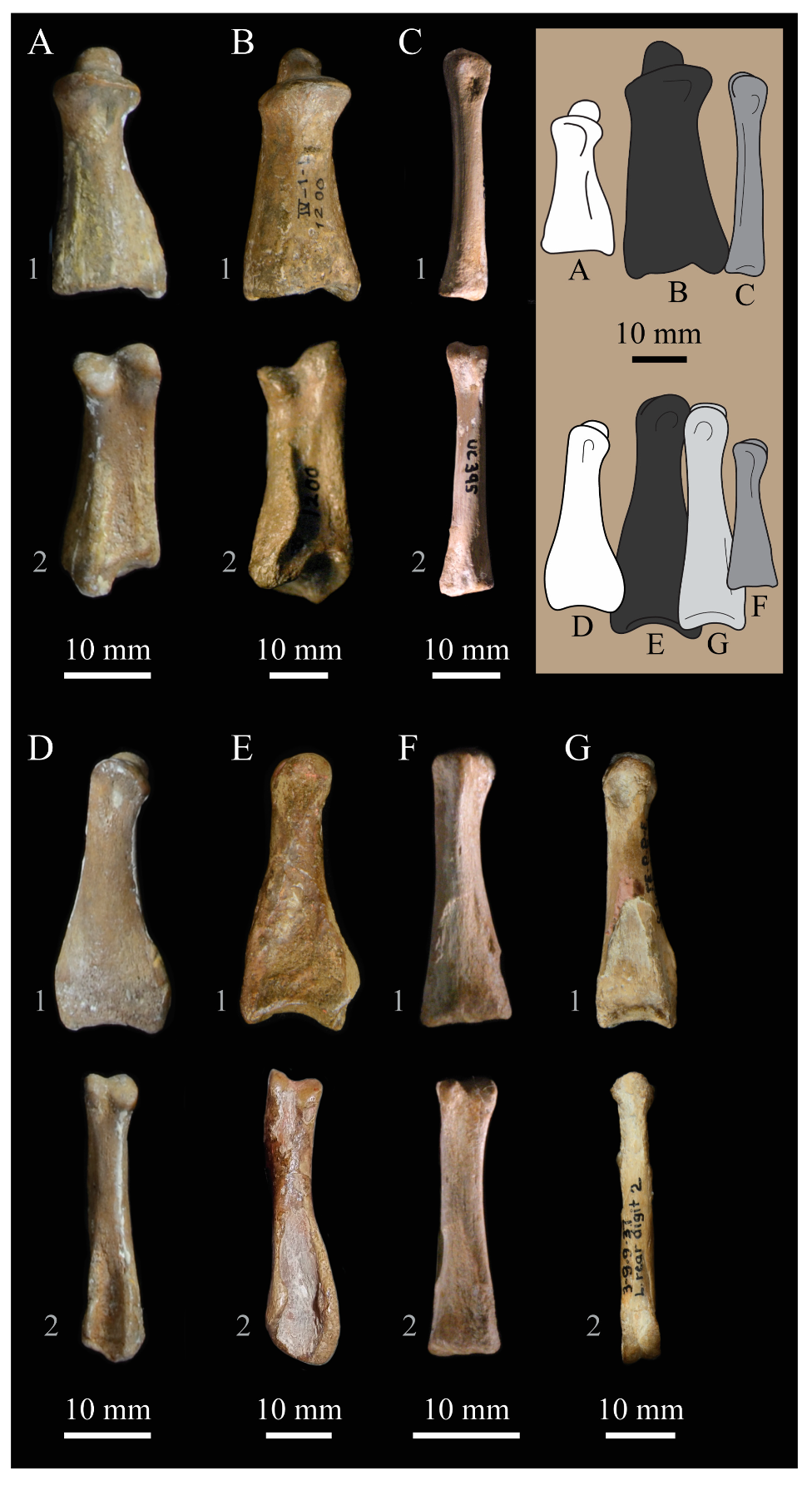

Parahesperornis is recognized by a unique suite of morphological features, including a small occipital condyle; narrow and deeply depressed recess in the lamina parasphenoidalis; sutures present on the basioccipitals; deep notch separating the zygomatic process and paraoccipital process; prominent paraoccipital processes; arched frontoparietal suture; interfrontal suture forms deep groove; reduced pneumaticity of the braincase; frontals flattened and very wide (width roughly 75% the length of the frontals); lacrimal elongate with long jugal process that terminates in a flattened face; caudomedial depression present on the quadrate; lateral crest of the quadrate restricted to the lateral margin; pterygoid triangular with flattened faces; premaxillae (width across the premaxillae at the nares is approximately 35% the pre-nares length); articulation of the angular to the dentary along a broad surface; surangulars convex laterally; expanded retroarticular process of the articular; anterior cervical vertebrae elongate while posterior cervical vertebrae become more compact; triangular coracoid with elongate neck; flat sternum with five costal processes; humerus reduced with only poorly defined condyles; elongate pelvis with reduced, circular acetabulum (acetabulum diameter approximately 10% ilium length); femur slightly waisted, with expanded trochanter and fibular condyle; head of femur extends proximally past trochanter; lateral condyle of femur extends only slightly distally past medial; elongate, triangular patella (distal mediolateral width approximately 50% of the proximodistal length); medial face of fibula with triangular depression; tibiotarsus with triangular cnemial expansion; tarsometatarsus with shingled metatarsals, proximal articular surface rhombic in proximal view, rounded intercotylar eminence, and trochlea IV extending slightly further distally than trochlea III; phalanges of pedal digit IV robust, with unevenly sized cotylae.

- Parahesperornis alexi Martin 1984.

3.1.3. Diagnosis

As for the genus.

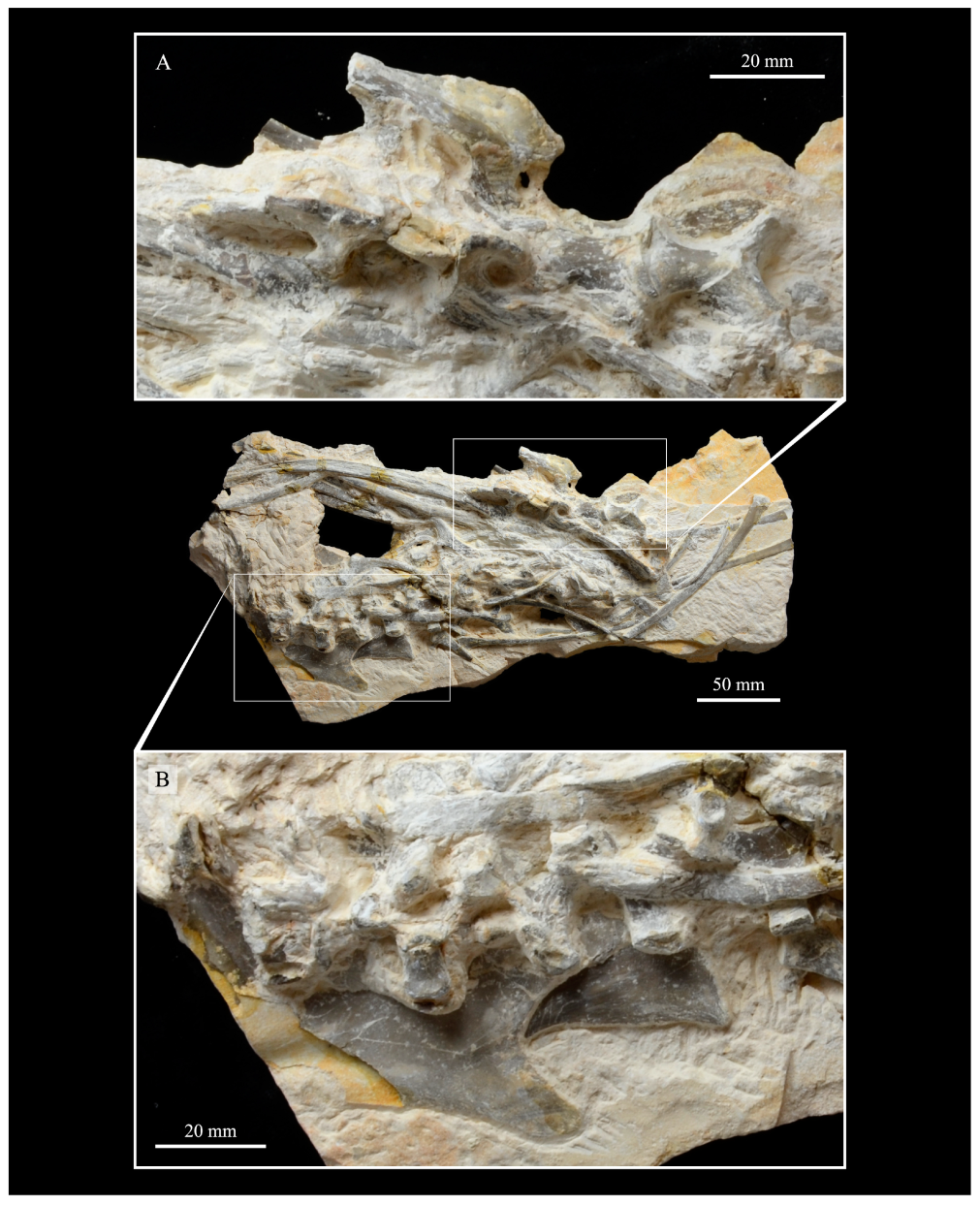

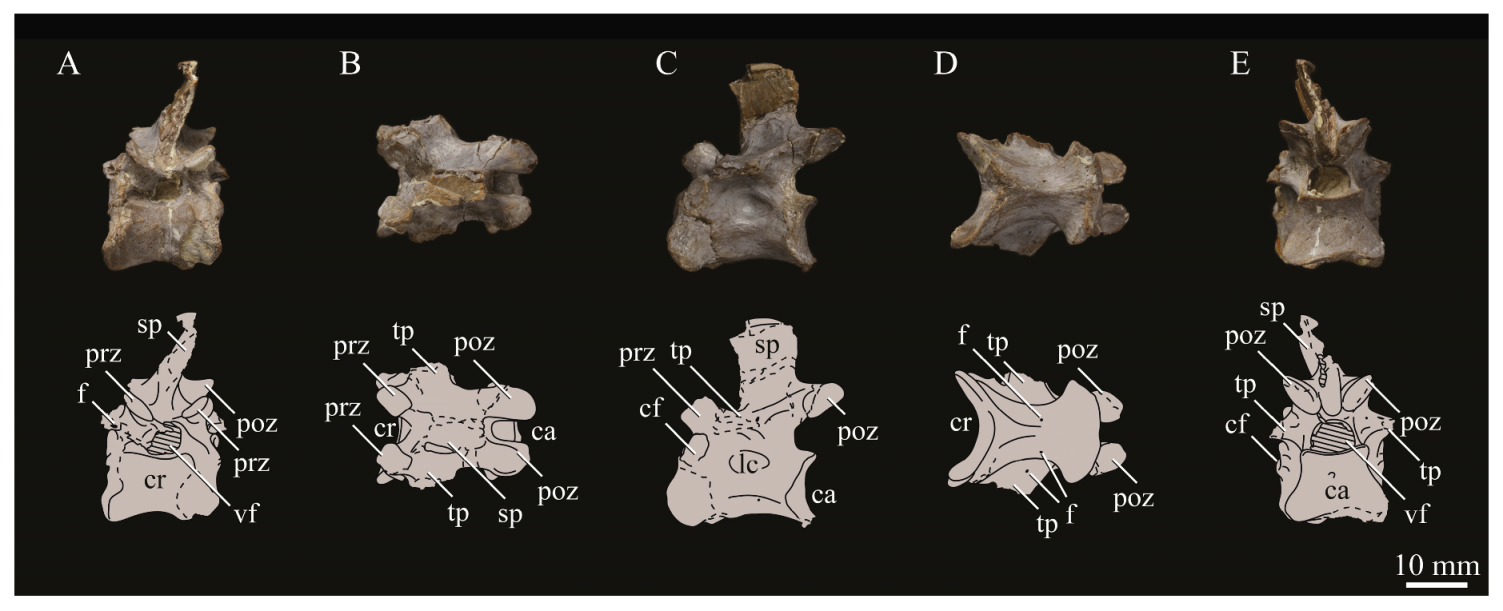

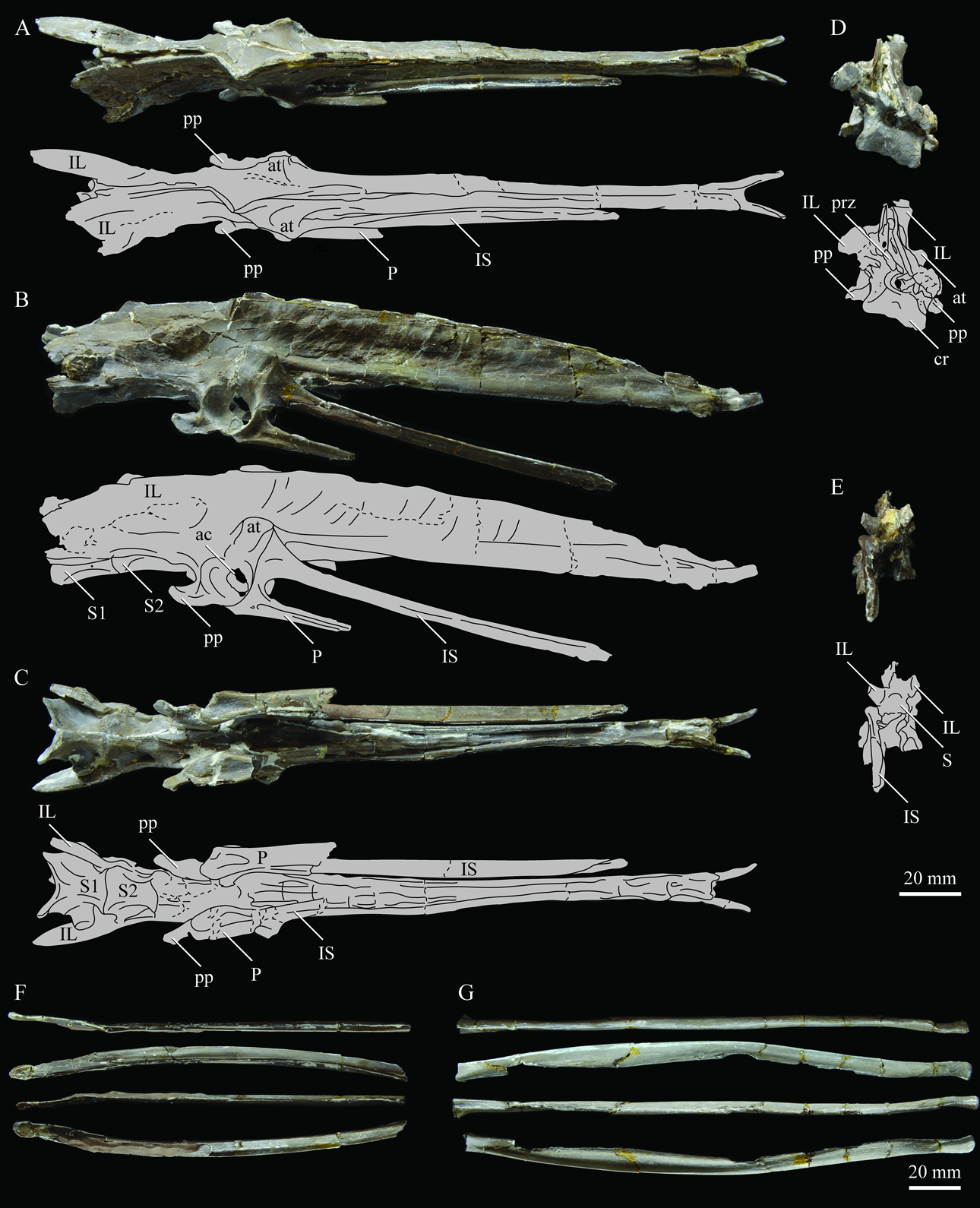

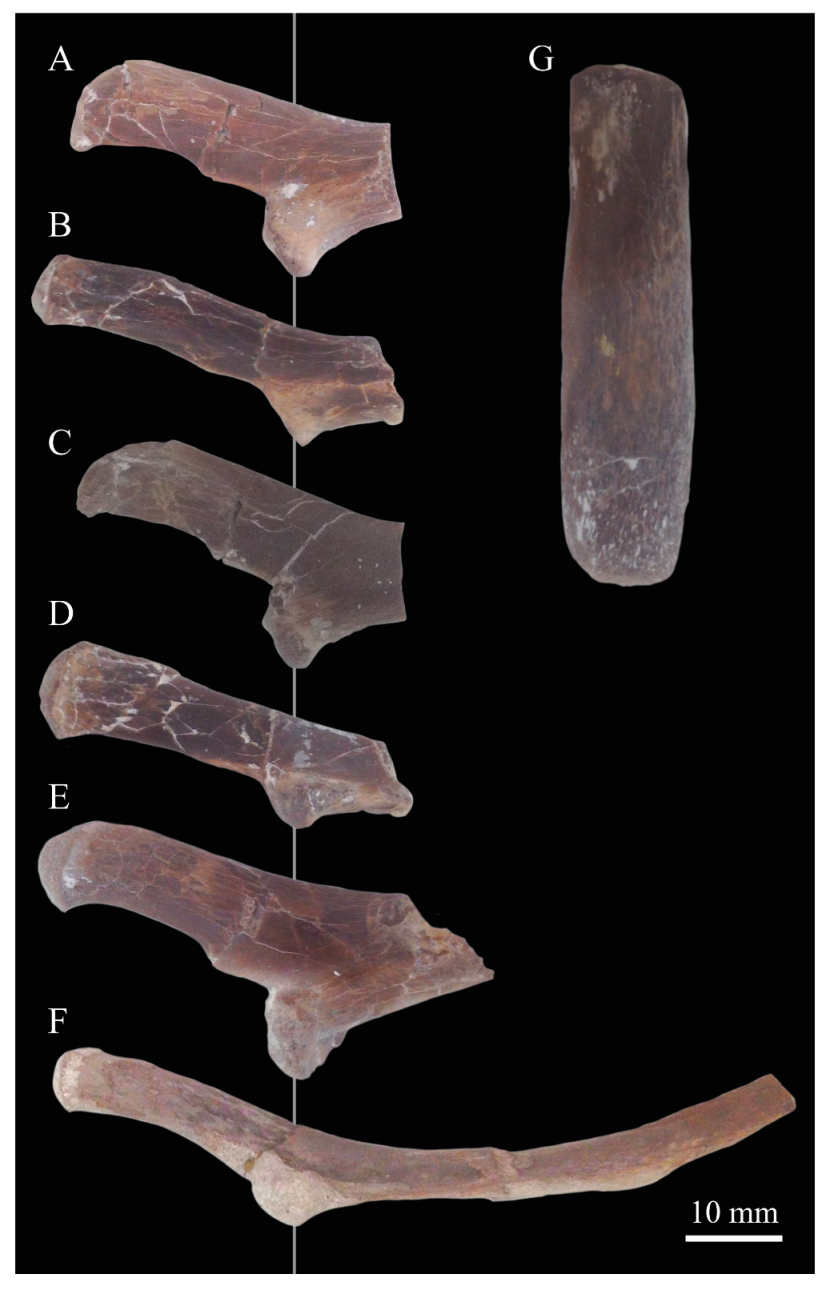

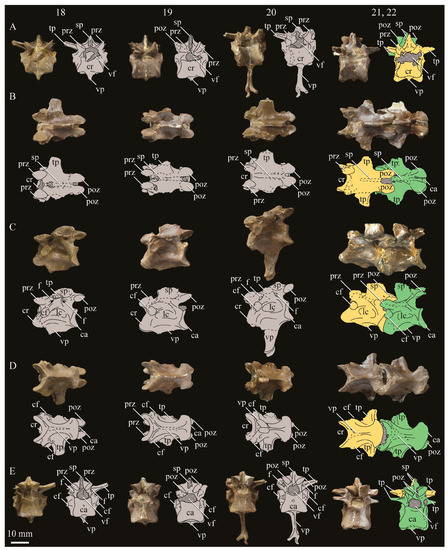

3.1.4. Holotype

KUVP 2287, an almost complete skeleton preserving a nearly complete, albeit crushed and disarticulated skull; 16 cervical, 6 thoracic, and 5 free caudal vertebrae; sternum; clavicle; coracoid; humeri; pelvis; femora; patellae; fibula; tibiotarsi; tarsometatarsi; 25 pedal phalanges; and impressions of skin. While histological analysis has not been conducted on this specimen, compound bone development is consistent with that of a fully-grown individual.

Type Locality & Geologic Setting. KUVP 2287 was discovered in 1894 by H. T. Martin in Graham County, Kansas, USA (KUVP locality number Gra-2). The specimen was collected from the Smoky Hill Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation, which spans approximately five million years, from 82–87 Ma (late Coniacian to early Campanian) [68].

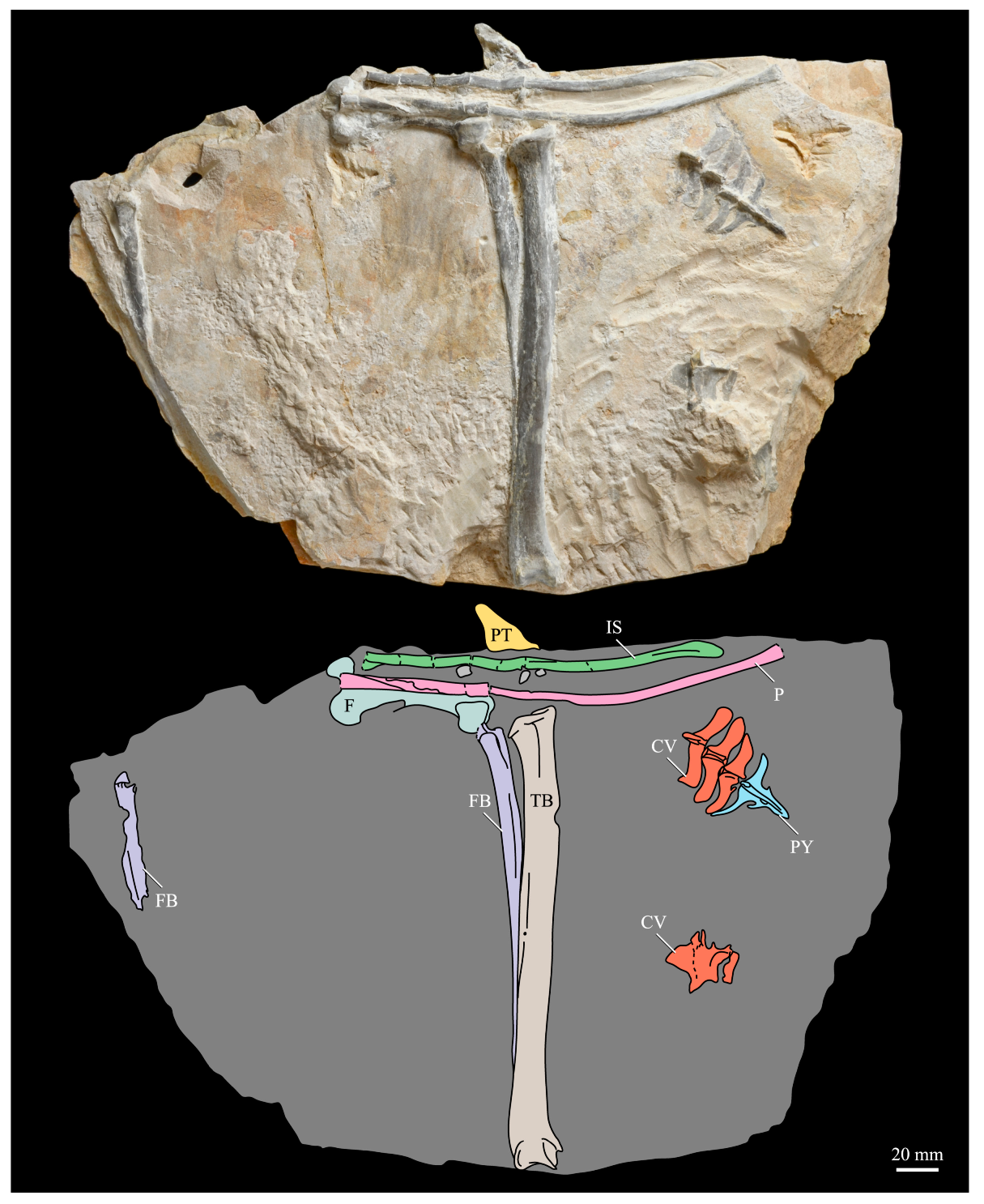

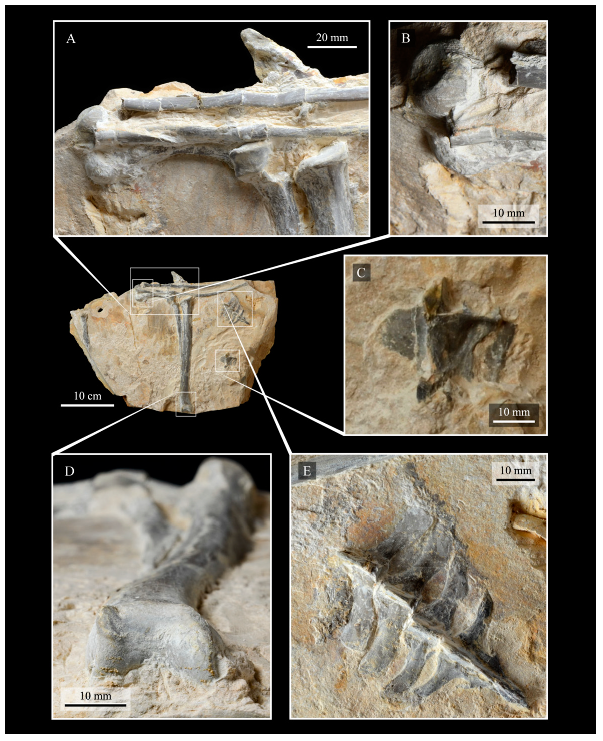

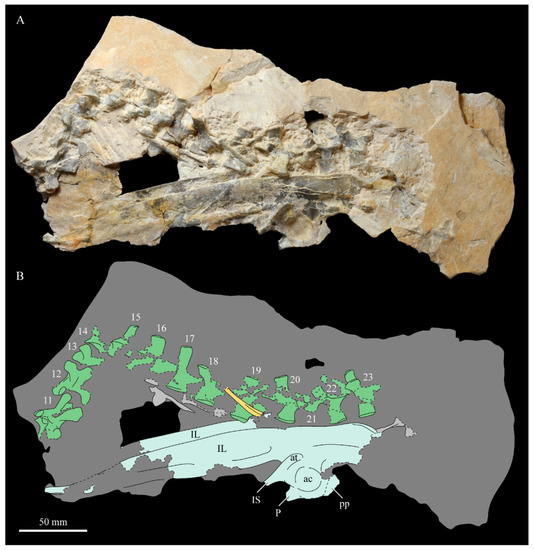

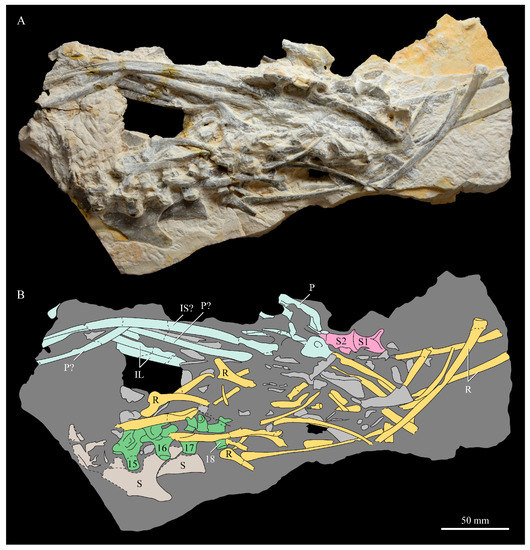

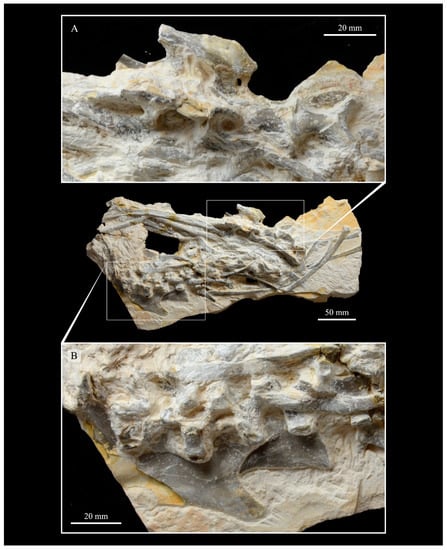

3.1.5. Assigned Specimens

KUVP 24090, a partial skeleton preserving four isolated cervical vertebrae and at least 13 articulated posterior cervical and thoracic vertebrae, four articulated free caudal vertebrae, pygostyle, pelvis, sternum, coracoid, femora, patella, and tibiotarsi. KUVP 24090 was collected by Orville Bonner in 1981 from the Smoky Hill Member of the Niobrara Chalk Formation in Gove County, Kansas, USA (KUVP locality Gove-59). Compound bone development of KUVP 24090 is consistent with that of a fully-grown individual.

FHSM VP-17312, an isolated tarsometatarsus from the upper Smoky Hill Chalk in Logan County, Kansas, USA in the early 1990s by Jerome Bussen [26]. Compound bone development of FHSM VP-17312 is consistent with that of a fully-grown individual.

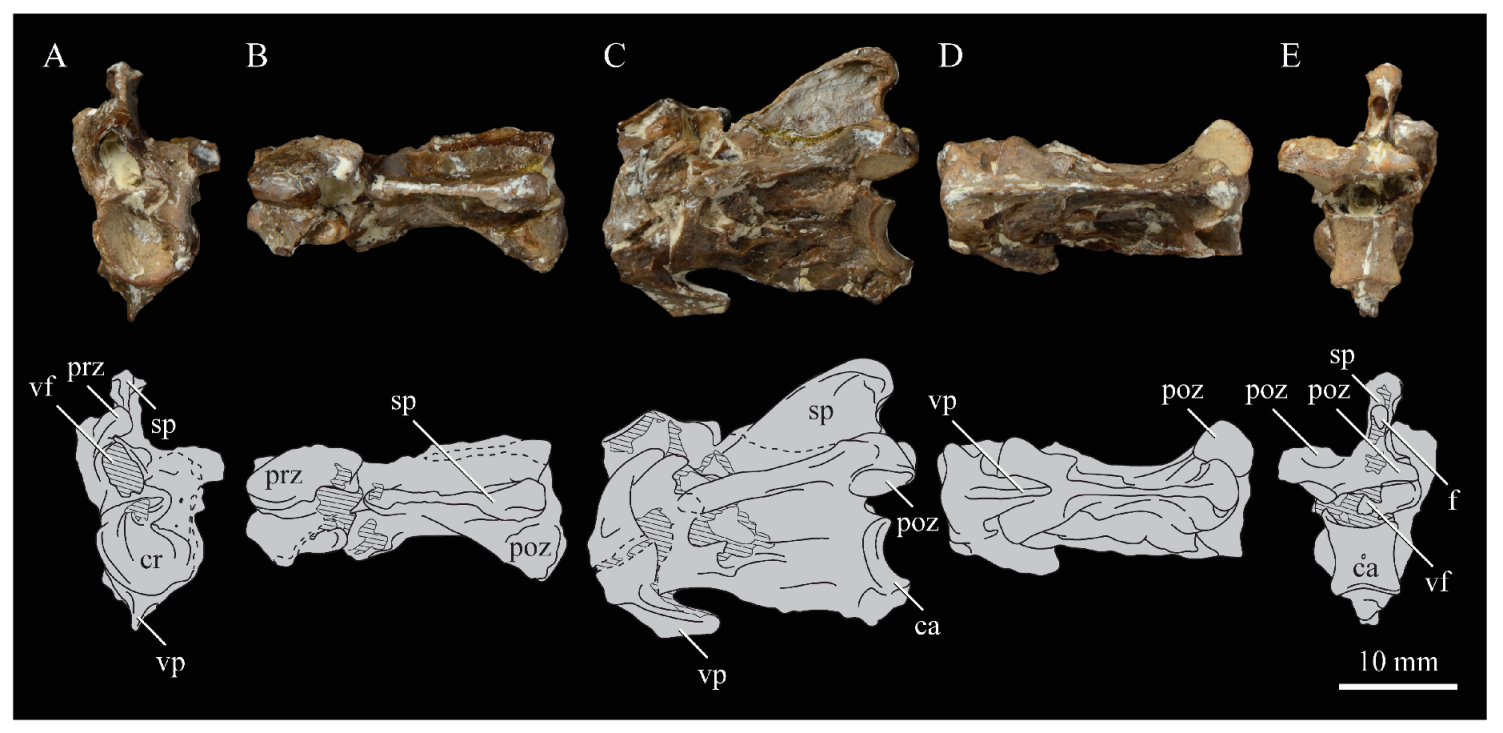

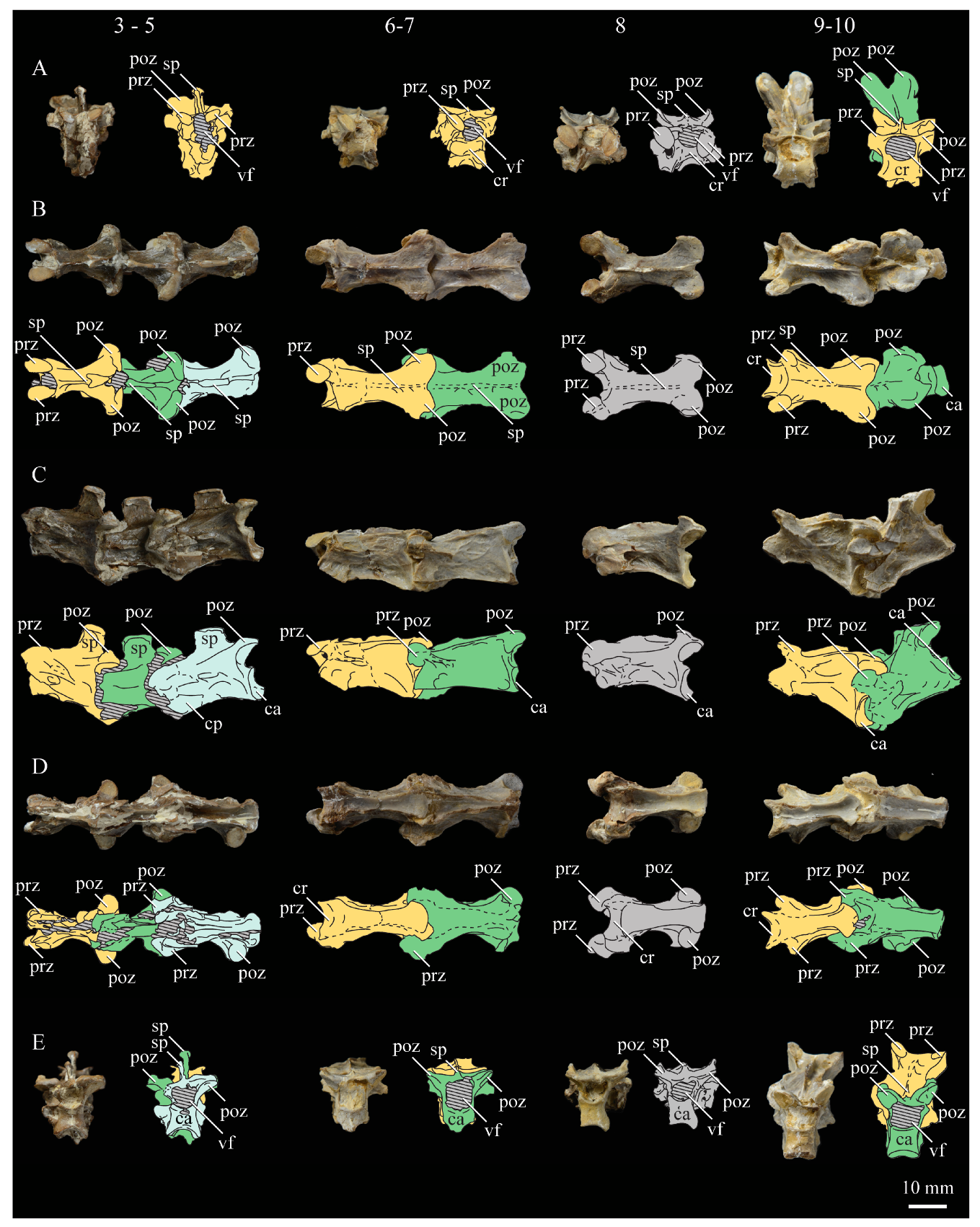

3.2. Description

3.2.1. Cranial and Mandibular Elements

While cranial and mandibular material is rare among hesperornithiform fossils, Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287 preserves a nearly complete (albeit crushed) skull. Comparative material is largely limited to two fairly complete skulls (KUVP 71012, YPM 1206) of Hesperornis, which have been extensively described in the literature [7,8,56,57,58,69,70,71,72,73], and a number of specimens preserving fragmentary cranial elements. It should be noted that due to previous, but incorrect, assignment of KUVP 2287 to Hesperornis gracilis, some previous works describe the skull of KUVP 2287 under that name [58,59]. In addition to some fragmentary material with other Hesperornis specimens (FMNH 219, NMNH 4978, NMNH 6622, NMNH 13580, UNSM 10148, YPM 903, YPM 1207, YPM PU 18589), the only other skull material known from the Hesperornithiformes is the complete quadrate of Potamornis skutchi [49] (UCMP 73103), fragmentary portions of several unassociated skull elements assigned to Pasquiaornis [65], the caudal portion of the mandibular ramus of Baptornis (FMNH 395), and three fragmentary braincases assigned to Enaliornis [72]. The braincase of Enaliornis (SMC B54404) is exceptional in the lack of crushing of the specimen (see previous work [72] for a complete description of the braincase of Enaliornis). Very small fragments of the quadrate and frontal of Baptornis (AMNH 5101) were previously reported [19], however no such elements are included with the specimen today. Elzanowski [49] noted that the accession record of AMNH 5101 never listed cranial elements, and so concluded the specimen was incorrectly attributed to AMNH 5101. Likewise, a fragment of the bill was reported with Baptornis specimen KUVP 16112 [19], however the specimen did not include material identifiable as such when consulted for this study. Outside of the hesperornithiforms, cranial material in Mesozoic ornithuromorphs is largely crushed, making detailed comparisons of morphology difficult. The skull of Ichthyornis is known from a number of three-dimensional specimens [61], and so is one of the only other non-neornithine ornithuromorphs for which comparisons of many aspects of the cranium can be made.

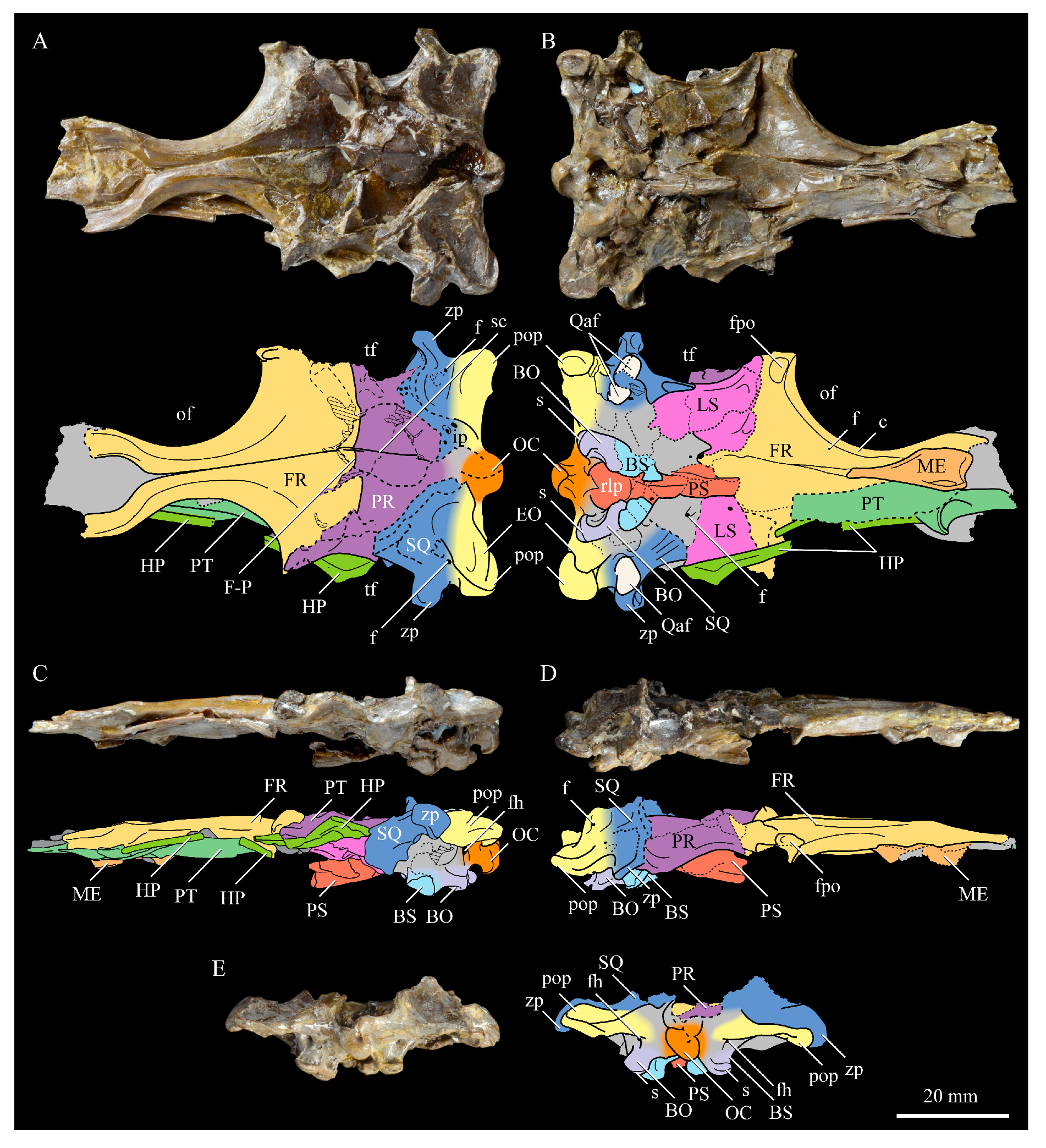

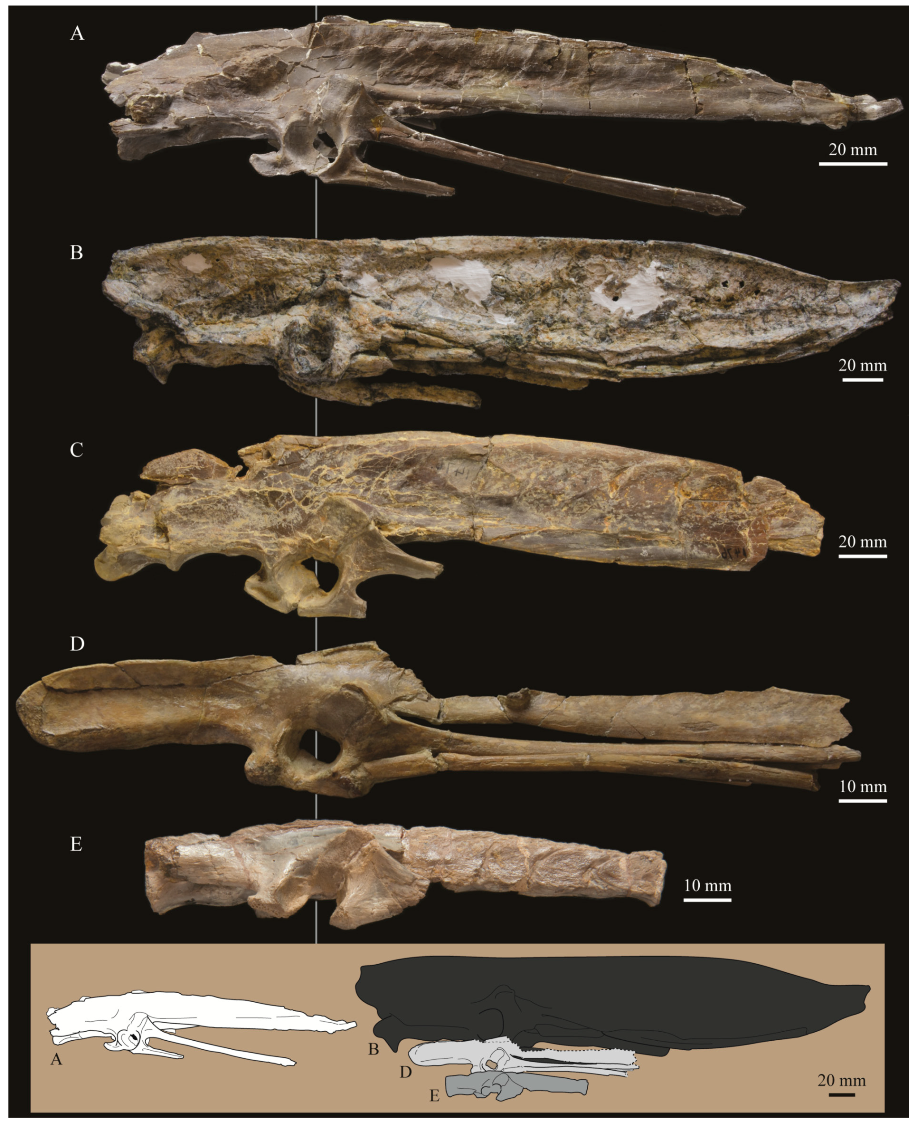

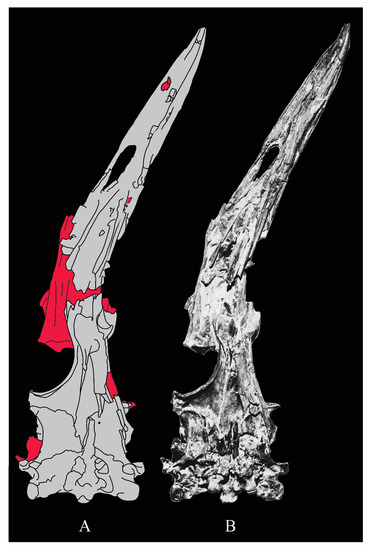

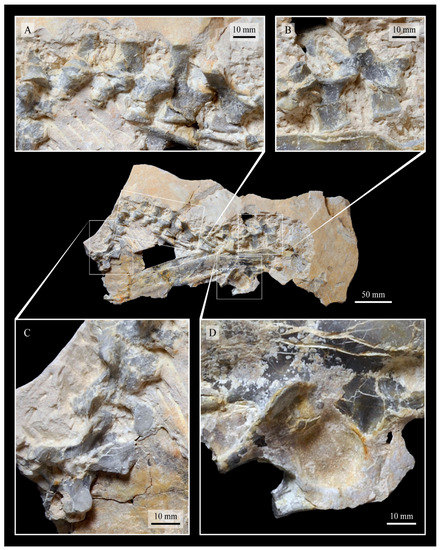

The skull of KUVP 2287 was originally preserved partially disarticulated. The majority of the cranium and upper jaw were articulated (Figure 4), while the lower jaws, quadrates, pterygoids, palatines, and lacrimals were preserved as isolated elements. At some point, the cranium and upper jaws were disarticulated into two pieces, one including the braincase and frontals (Figure 5 and Figure 6) and the second piece consisting of the premaxillae, nasals, and a number of palatal elements (Figure 7 and Figure 8). This is important to note, as during this process some material from the specimen was lost (see Figure 4). Possible identifications for these missing pieces are discussed below.

Figure 4.

The articulated skull of KUVP 2287 before disarticulation [69]. Areas shaded red denote portions no longer present with the specimen.

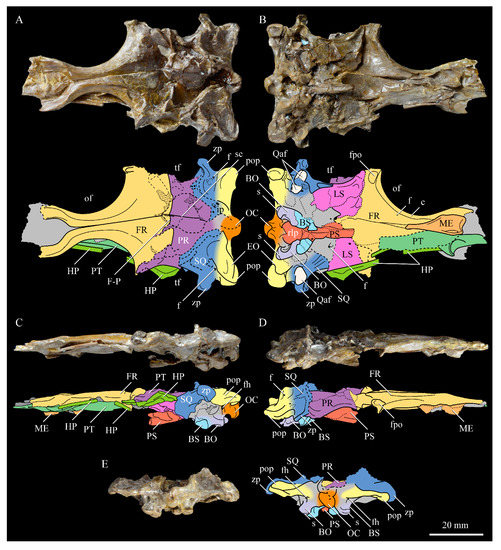

Figure 5.

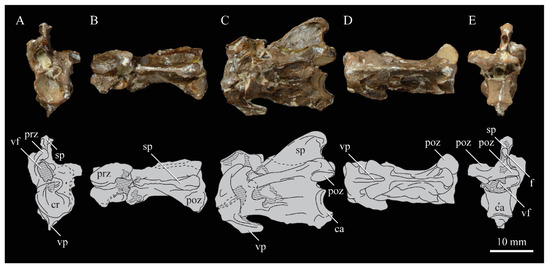

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, photographs (upper) and line drawings (lower) of the articulated braincase and frontals in dorsal (A), ventral (B), left lateral (C), right lateral (D), and caudal (E) views. Abbreviations: BO—basioccipital, BS—basisphenoid, c—crest (see text for discussion), EO—exoccipital, F-P—frontoparietal suture, f—foramen, fh—foramen for the hypoglossal nerve, fpo—facet for articulation of the prostorbital process of the parietal, FR—frontal, HP—hemipterygoid, ip—internal pneumaticity, ip—visible internal pneumaticity, LS—laterosphenoid, ME—mesethemoid, OC—occipital condyle, of—orbital fenestra, PR—parietal, pop—paraoccipital process, PS—parasphenoid rostrum, PT—palatine, Qaf—quadrate articular facet, rlp—recess in the lamina parasphenoidalis, sc—sagittal crest, s—suture, SQ—squamosal, tf—temporal fenestra, zp—zygomatic process.

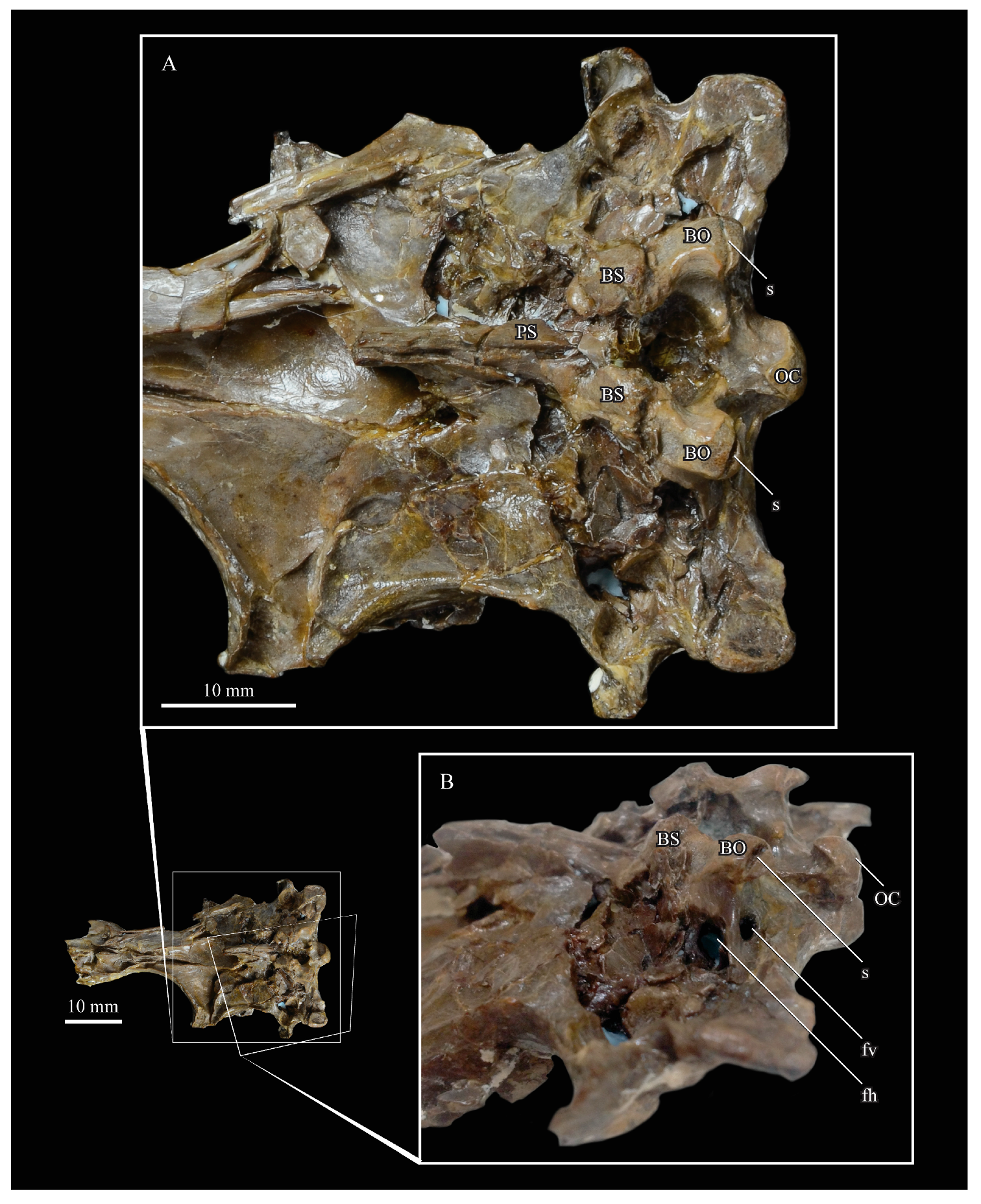

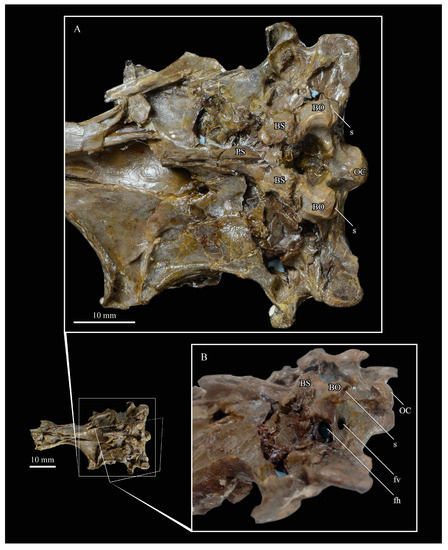

Figure 6.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, enlargement of the dorsal surface of the braincase in dorsal (A) and in laterodorsal view (B). Abbreviations: BO—basioccipital, BS—basisphenoid, fh—hypoglossal foramen, fv—vagus foramen, OC—occipital condyle, s—suture.

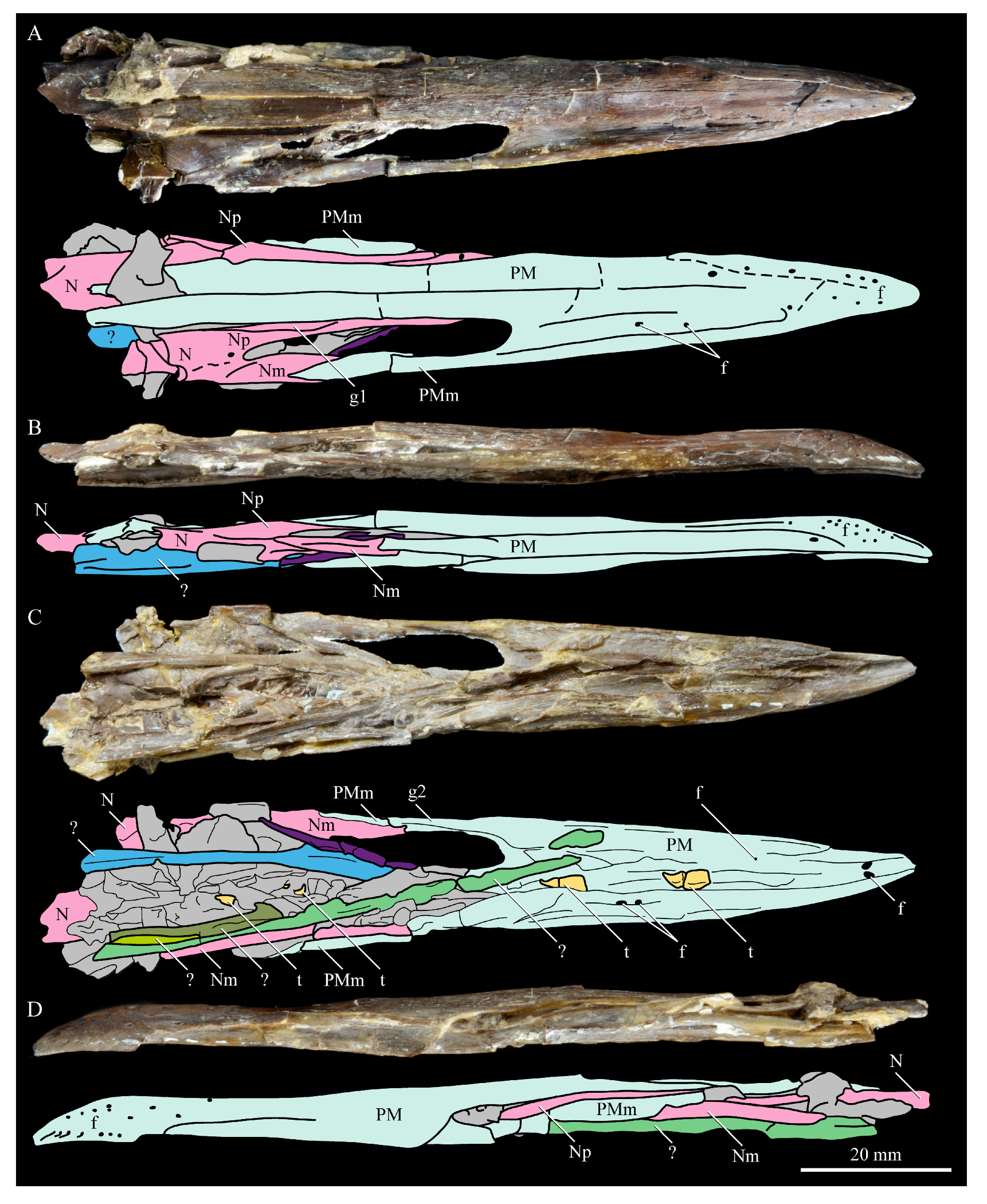

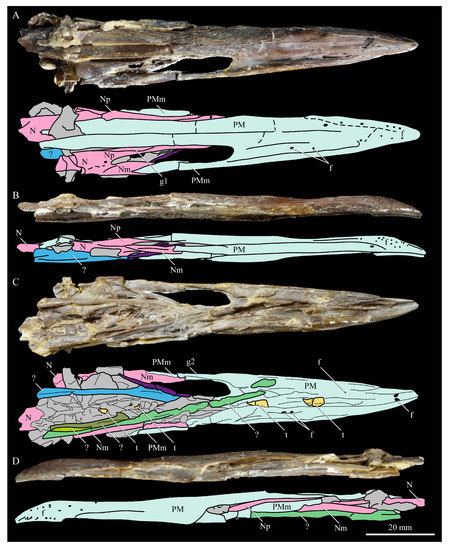

Figure 7.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, premaxillary region photographs (upper) and line drawings (lower) in dorsal (A), right lateral (B), ventral (C), and left lateral (D) views. Abbreviations: f—foramen, g1—groove on the premaxillary process of the nasal, g2—groove on the maxillary process of the premaxilla, N—nasal, Nm—maxillary process of the nasal, Np—premaxillary process of the nasal, PM—premaxilla, PMm—maxillary process of the premaxilla, t—tooth, ?—unidentified palatal bones, see text for more detail.

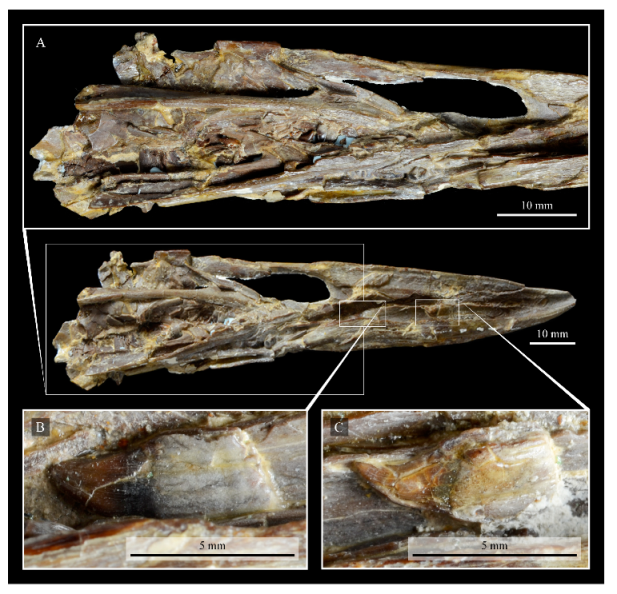

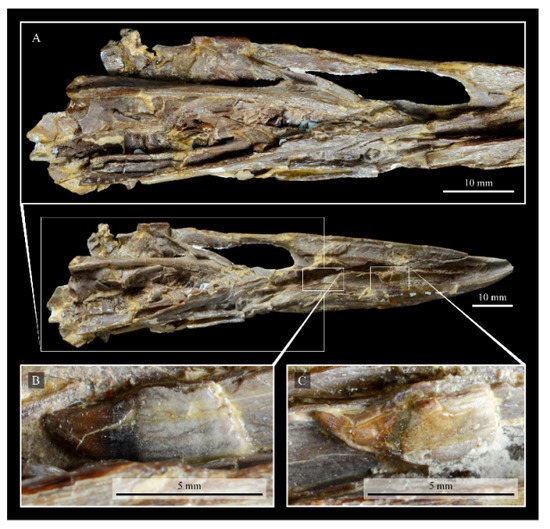

Figure 8.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, details of the ventral surface of the premaxilla showing the region preserving unidentified palatal elements (A) and individual teeth (B,C).

Braincase. The braincase of KUVP 2287 is highly crushed dorsoventrally and articulated to the frontals (Figure 5 and Figure 6). For comparisons, braincases of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012) and Enaliornis (SMC B54404) were examined (Figure 9). In ventral view (Figure 5B), the occipital region of KUVP 2287 is fairly clear. The occipital condyle is broken into halves and is slightly hook-shaped, with the rounded surface curving over the somewhat indented dorsal base of the condyle. Despite the breakage, the occipital condyle of Parahesperornis appears to be much smaller proportionally than that of Hesperornis (Figure 9). The occipital condyle of Enaliornis is not preserved.

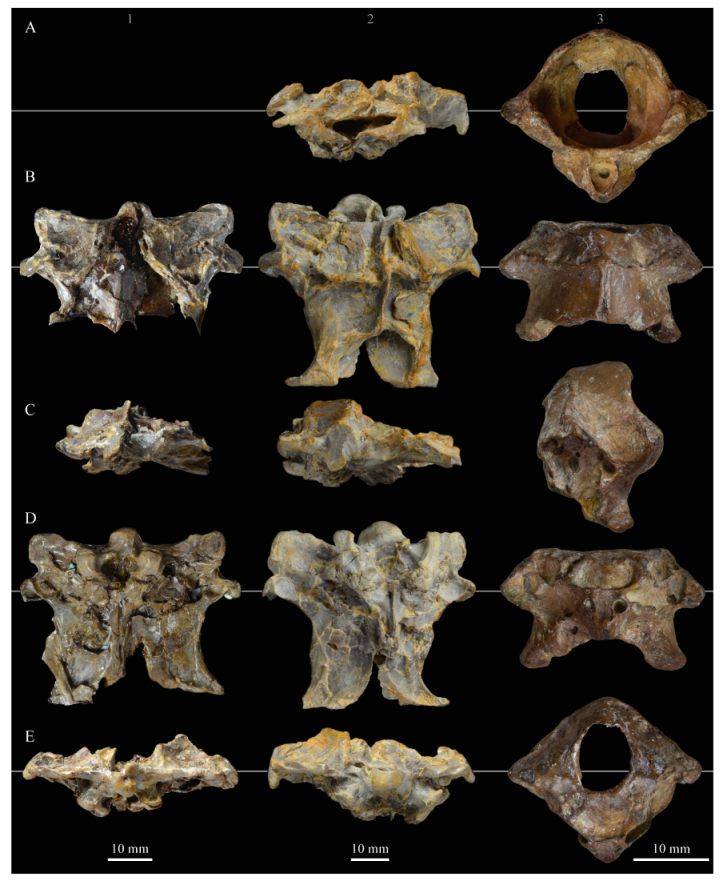

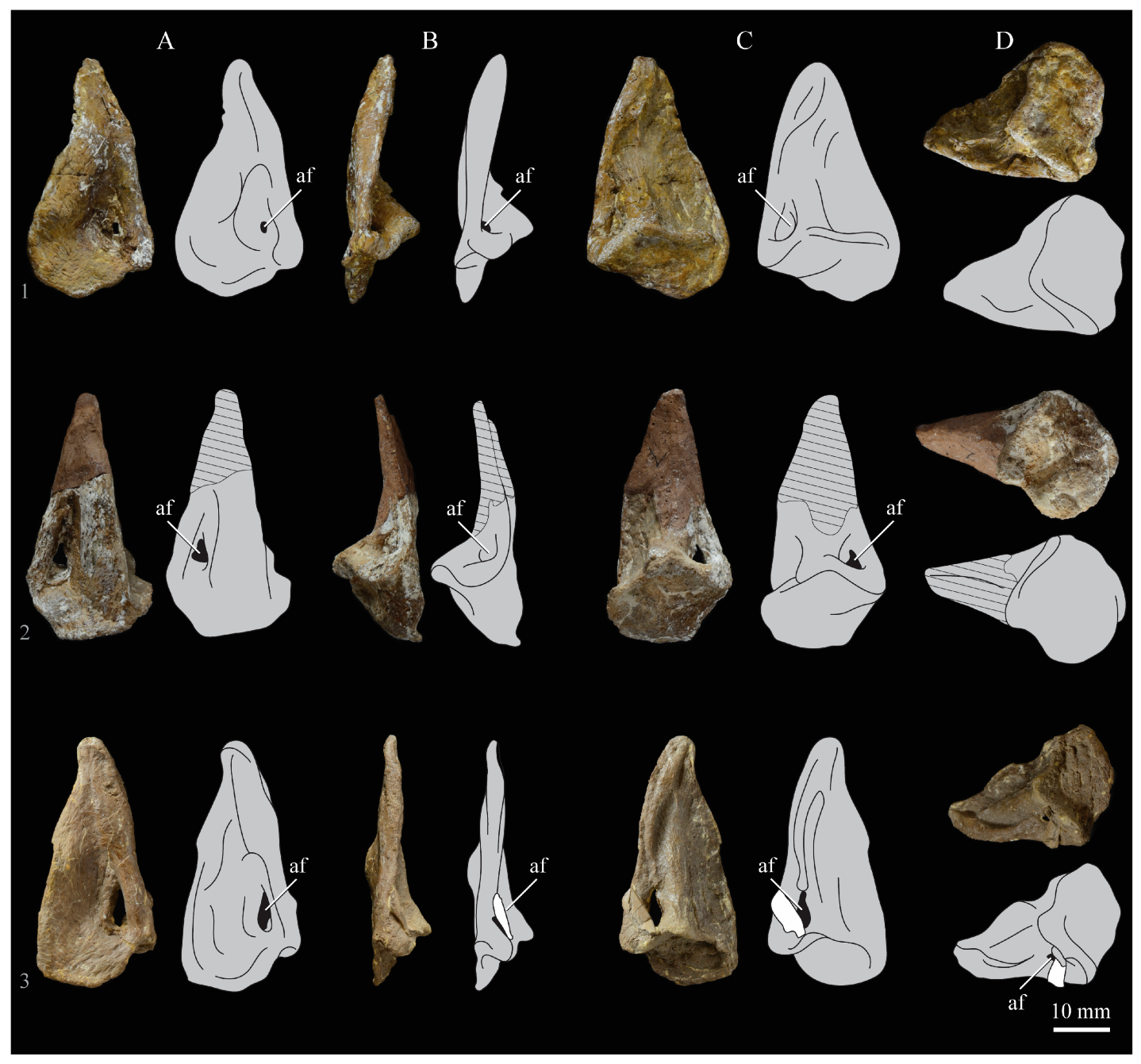

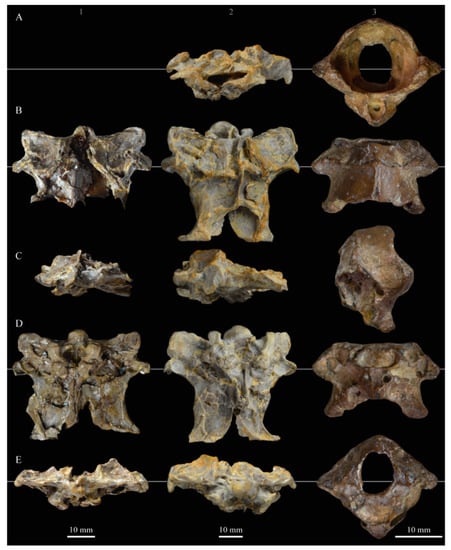

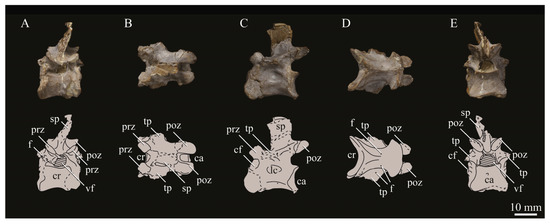

Figure 9.

Comparison of the braincases of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1), Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2), and Enaliornis SMC B54404 (3) in rostral (A), dorsal (B), lateral (C), ventral (D), and caudal (E) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar widths at the zygomatic processes. The articulated frontals have been digitally removed for 1.

Ventrally, rostral to the occipital condyle is a deep, round recess in the lamina parasphenoidalis (rlp in Figure 5). This recess appears to be narrower and more deeply excavated in KUVP 2287 than in Hesperornis, however this may be enhanced by crushing. In Enaliornis this recess is prominent and mediolaterally elongate, taking up a larger portion of the ventral skull than in either Parahesperornis or Hesperornis, perhaps indicating the degree of crushing in both KUVP 2287 and KUVP 71012.

In Parahesperornis the recess of the lamina parasphenoidalis is defined by the basioccipital and basisphenoid (BO and BS, respectively, in Figure 5); the latter bones wrap around the recess and nearly meet at the base of the parasphenoid rostrum (PS in Figure 5). The basioccipitals of Parahesperornis are roughly kidney-shaped, with what appear to be prominent sutures on the caudal ends, the right of which is somewhat open (s in Figure 5 and Figure 6). In Hesperornis the basioccipitals are more elongate with less curvature and lack any visible sutures. These elements are not preserved in Enaliornis.

The basisphenoids of Parahesperornis are both somewhat crushed but appear to overlap the basioccipitals, with a flattened face that angles toward the parasphenoid rostrum, as in Hesperornis. There appears to be a suture present between the basioccipital and basisphenoid of Parahesperornis. A similar suture is present and more obvious in Hesperornis. In Enaliornis, the area rostral to the recess in the lamina parasphenoidalis is very different, preserving a distinct pyramidal projection with two large fossae on the lateral and medial margins, tentatively identified as the canalis orbitalis by Elzanowski and Galton [72].

The parasphenoid rostrum of Parahesperornis extends rostrally as a straight, paired bone with a smoothly rounded ventral surface (PS in Figure 5). Lucas [13] noted that the parasphenoid rostrum extended to the mesethemoid in KUVP 2287, however today it is broken considerably caudal to the mesethemoid. In Hesperornis the ventral surface of parasphenoid rostrum is projected and forms a crest. The parsphenoid rostrum is not preserved in Enaliornis.

The basioccipitals are propped up on struts of bone, into which two foramina are visible piercing the base of the strut (Figure 5 and Figure 6). While the exact identity of these foramina is uncertain, it is likely that the smaller, more caudal foramen corresponds to the foramen for the exit of the hypoglossal nerve (XII) (fh in Figure 5 and Figure 6) while the larger, laterally facing one corresponds to the foramen for the vagus nerve (X) (fv in Figure 6). This is unlike Hesperornis, where three small foramina are seemingly associated with the hypoglossal nerve, while Parahesperornis has only one. In Enaliornis these foramina are present at the caudomedial and -lateral borders of the recess in the lamina parsphenoidalis (Figure 9).

Lateral to these foramina the exoccipital extends sideways, forming a prominent rounded paraoccipital process with a flattened ventral surface (pop in Figure 5; sometimes referred to as the exoccipital process [67]). This process is separated from the more rostrally-located zygomatic process (zp in Figure 5) by a deep indentation in the lateral margin. This indent is much less dramatic in Hesperornis, where the exoccipital process and prootic appear as a more continuous rectangular shape in ventral view. The indentation is lacking entirely in Enaliornis, where the paraoccipital processes are much reduced and appear as very slight protuberances in dorsal view (Figure 9).

The zygomatic process of Parahesperornis extends laterally and slightly rostrally from the edge of the dorsal cranium and has a flattened face that has been crushed under ventrally on both sides. This face is better preserved in Hesperornis KUVP 71012, where it is oval shaped with a slightly domed surface and appears to form a slight hook, however discrepancies between the left and right sides make it unclear how much of that shape is due to crushing (Figure 9). The zygomatic processes of both Parahesperornis and Hesperornis are much reduced as compared to those of Enaliornis, where they form broad triangular processes directed more rostrally than in hesperornithids (Figure 9).

Dorsally, the area of the squamosals and exoccipitals medial to the zygomatic and paraoccipital process is developed as a broad, shallowly depressed face that is roughly rectangular. A few small foramina are preserved near the lateral indentation in the margin between the zygomatic and paraoccipital processes. In contrast to Parahesperornis, a single foramen is observed in Hesperornis; however, the region is obscured by crushing in KUVP 71012, the only skull available for study where this feature is observed. In Hesperornis this area also forms a broad depression; however, the shape approaches a square in Hesperornis as opposed to the rectangle in Parahesperornis. In Enaliornis this area is smaller and flattened as compared to the depressed surface in hesperornithids.

Ventrally, deep facets are developed medial to the zygomatic processes for the articulation with the otic processes of the quadrate (Qaf in Figure 5). This facet is better preserved on the left side of the skull and is like that seen in Hesperornis. In Enaliornis the articulation for the quadrate is less defined, and forms a shallower depression divided into two similarly sized facets for articulation with the squamosal and otic heads of the quadrate, separated by the dorsal pneumatic foramen (Figure 9). This foramen is not observed in the facet in KUVP 2287 or KVUP 71012.

In ventral view, the braincase of Parahesperornis makes a sweeping curve at the margin of the temporal fossa that ends in a laterally projecting terminus where the braincase articulates with the frontals. This terminus does not appear to form a well-developed postorbital process (as in Ichthyornis [61]), however it is possible breakage has obscured this. The margin of the temporal fossa echoes that of the orbital margin of the frontals but is slightly shorter and indented to a lesser degree. It is unclear where the boundary between the parietals and the laterosphenoid occurs. As such our identifications of the boundaries of these bones (PR and LS in Figure 5) should be considered tentative. Hesperornis has a much more exaggerated lateral projection of the postorbital process than Parahesperornis, while that of Enaliornis is reduced (Figure 9). The ventral walls of the braincase leading up to this margin are smooth but extremely crushed in Parahesperornis. In Hesperornis, they slope slightly ventrally to meet below the parasphenoid rostrum. The breakage pattern in KUVP 2287 might suggest that the walls of the braincase were not fused where they met at the midline, however this cannot be confirmed.

While crushing might obscure some details of the exact margins of the temporal fossa, it appears to be mostly open and only partially enclosed by the zygomatic process caudally and the postorbital process rostrally. The temporal fossa of Hesperornis is similar, while that of Enaliornis is much shorter caudorostrally. The structure of the temporal fossa is intermediate between most modern birds, where it is much reduced and only slightly enclosed by bone, and Ichthyornis, where the temporal fossa is almost completely enclosed by bone, more similar to the primitive dinosaurian condition [61]. The temporal fossa in some Neornithes, such as the extinct (Mio-Pliocene) flightless alcids Mancallinae, appear to be most similar to that of the hesperornithids [74].

In dorsal view the caudal portion of the surface of the braincase of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 has split along the sagittal crest (sc in Figure 5), obscuring the foramen magnum. While it is not possible to describe the sagittal crest in Parahesperornis, in Hesperornis it is a large, sharp crest tightly sutured along its length (Figure 9). As the point of attachment for the deep fascia of the neck muscles67, the robust sagittal crest indicates the significance of these muscles in stabilizing the neck while diving. In Enaliornis the sagittal crest is only faintly developed caudally, between the squamosals, and appears to become less sutured rostrally, with the rostral extent partially open.

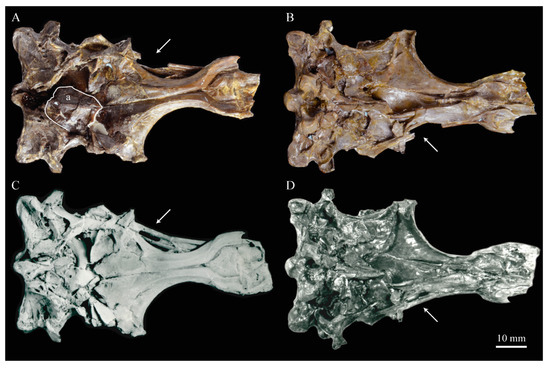

Rostral to the squamosal area on the dorsal side, the braincase of KUVP 2287 is heavily crushed, however a small piece in the center of the crushed area preserves a section of the parietals with the sagittal crest and a piece that appears to contain the frontoparietal suture (F-P in Figure 5). It should be noted that this piece may have been positioned during preparation, as undated photographs show the specimen without this piece (Figure 10). The frontoparietal suture is better preserved in Hesperornis, where it runs in a broad transversal arc and forms a cross where it intersects the sagittal crest (Figure 11). In Hesperornis the frontoparietal contact appears to be fully sutured. The small portions of the preserved frontoparietal suture in Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 agree with this morphology.

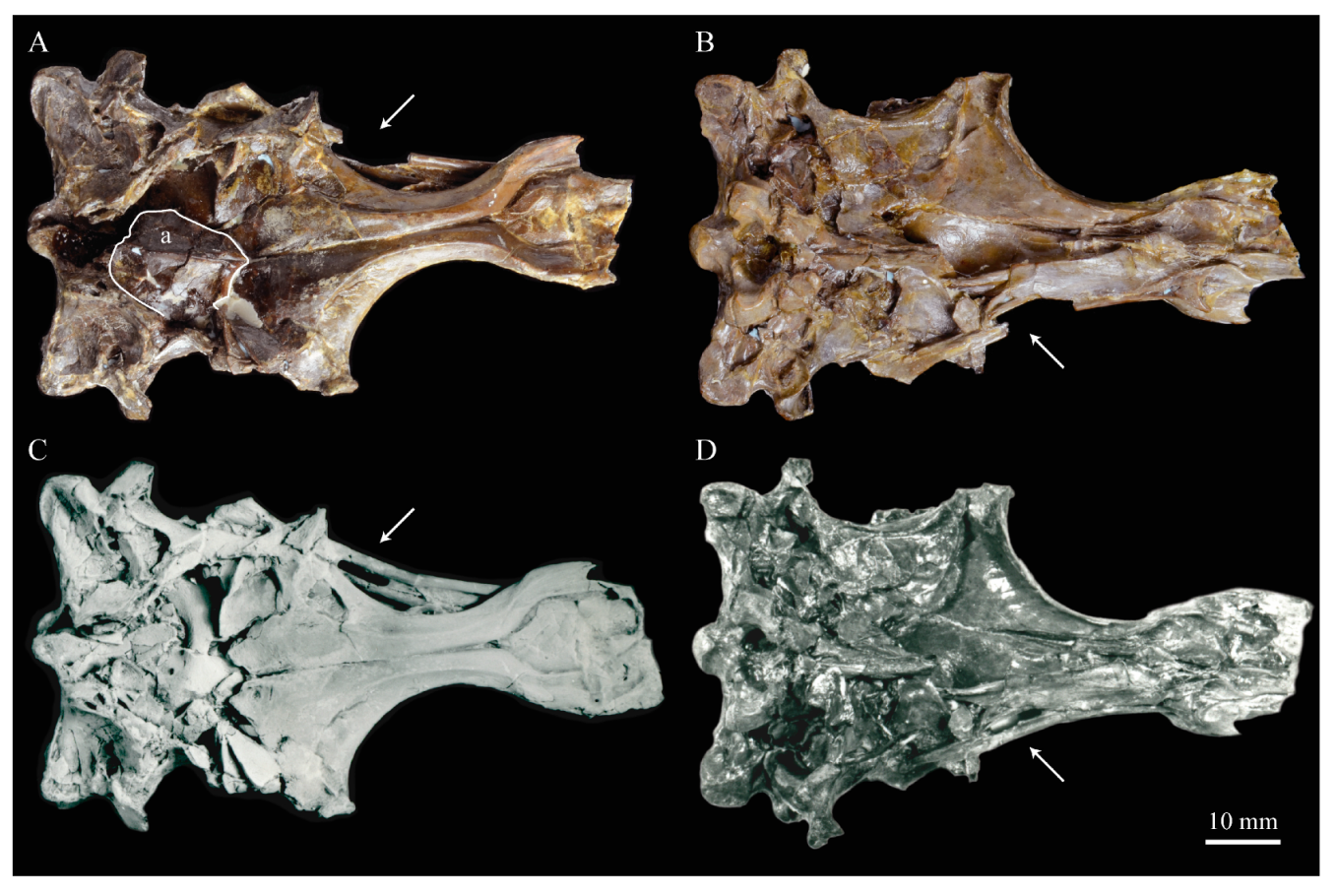

Figure 10.

Braincase and orbital region of Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287 after (A,B) and before (C,D) preparation in dorsal (A,C) and ventral (B,D) views. Arrows indicate a missing section of the hemipterygoid, while the outline in A shows a small piece of the parietals apparently added.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the frontals of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1), Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2), and Pasquiaornis RSM P2995.4 [65] (3) in dorsal (A), ventral (B), and right lateral (C) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar size across the right frontal and aligned at the caudal margin of the orbit. Extraneous bones and fragments have been digitally removed from 1.

This observation contradicts Martin’s [40] interpretation of the frontals and parietals as meeting in a moveable joint, giving Parahesperornis a mesokinetic cranium, while the juncture in Hesperornis was fused and immobile. Later work by Buhler et al. [57] described the frontoparietal juncture of Parahesperornis as consisting of a posterior ridge on the frontals that fit into an anterior groove on the parietals; however, due to the degree of crushing in KUVP 2287 this cannot be confirmed. Rather, the small portion of the frontoparietal suture preserved where it intersects the sagittal crest forms a crest and appears to be sutured.

In Enaliornis, the three known braincases are broken along what has been interpreted to be the frontoparietal suture [21]. If correct, then the frontoparietal suture was nearly linear in Enaliornis, not arced as in hesperornithids. This consistent breakage pattern was also used to infer an open frontoparietal suture in Enaliornis [21]. One specimen assigned to Pasquiaornis (RSM P2995.4) preserves a portion of the frontoparietal suture, which does not appear to be open [65]. The suture forms a low, thin crest, that is fairly straight and angles caudally from the juncture with the sagittal crest. In all, despite apparent differences in the trajectories of the frontoparietal suture, with the possible exception of Enaliornis, the frontals and parietals of hesperornithiforms appeared to have been sutured to each other.

The braincases of Parahesperornis and Hesperornis show much less pneumaticity than Enaliornis. In Enaliornis the braincase is highly pneumatic, with multiple foramina on the caudal end in the occipital region [72]. While the crushing of the braincases of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 and Hesperornis KUVP 71012 may have obscured some foramina in the rostral portions, the caudal braincase is fairly well preserved, and it is doubtful that either skull would have approached the level of pneumaticity seen in Enaliornis. In KUVP 2287, internal views along the broken sagittal crest show some pneumatization of the interior of the bone (ip in Figure 5). However, there is no evidence of internal pneumaticity in the broken edges of Hesperornis KUVP 71012.

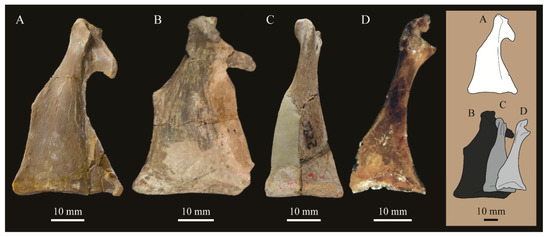

Frontals. The frontals of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 are preserved somewhat articulated with and flattened back upon the braincase (Figure 5). For comparison, the frontals of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012, YPM 1206) and Pasquiaornis (RSM P2995.4 [65]) were examined (Figure 11). In dorsal view, the frontals of KUVP 2287 meet at the interfrontal suture, which forms a slight groove. To either side of this groove the frontals are flattened, with an arced, central crest that parallels the margin of the orbit, running along the length of the dorsal surface. Such morphology is very different from that of the frontals of Hesperornis and Pasquiaornis, where the interfrontal suture forms a longitudinal crest, continuous with the sagittal crest.

The central region of the sutured frontals is shortened in Parahesperornis as compared to Hesperornis. This gives the mediocaudal margin of the orbit, as formed by the lateral edge of the frontals, a more circular shape in Parahesperornis, whereas in Hesperornis the orbit is elongate and much more shallowly curved. It is difficult to compare the shape of the incomplete caudal orbit in Pasquiaornis; however, it appears to be intermediate between the morphologies of Hesperornis and Parahesperornis. In relative terms, Parahesperornis has a much broader skull than Hesperornis at the level of the orbits. The frontals of Hesperornis and Parahesperornis have similar widths, despite Parahesperornis being a much smaller animal overall. Pasquiaornis appears proportionally narrower as well, more like Hesperornis.

The frontals of Parahesperornis appear to be tightly sutured along the majority of their length, however at the rostral-most end they become slightly separated from one another before the left and right frontals diverge and define a dramatic U-shaped rostral terminus (Figure 5A). This U-shaped rostral end of the frontals is also seen in Hesperornis and Pasquiaornis, however the U-shape is narrower in the latter (Figure 11). This contrasts with Ichthyornis, where the frontals angle away from each other slightly, forming a Y-shape [61]. In lateral view, the frontals of Parahesperornis are fairly flat, as in Pasquiaornis, however in Hesperornis they are strongly domed caudally (Figure 11C).

In Parahesperornis, the dorsal margin of the frontals forming the upper orbit slope toward the orbit fairly steeply along their entire length, forming an angle dorsally where they flatten out medially before meeting at the interfrontal suture. Pasquiaornis resembles Parahesperornis in the angle of the flattened surface, however in Hesperornis the angle is entirely lacking, and the sides of the frontals slope continuously from the juncture of the interfrontal and sagittal crests with the frontoparietal suture. Lucas [13] described Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 as having depressions for supraorbital glands (fossa glandula nasales). In modern birds the lateral edges of the frontal dorsal to the orbit are often broad with a well-developed depression for the supraorbital gland. The morphologies seen in hesperornithiforms cast doubt about the interpretation of supraorbital glands, which if present, would have been rather small.

In ventral view, the orbital margin of the frontals forms a sharp lip or crest in Parahesperornis (c in Figure 5), as in Pasquiaornis, while in Hesperornis the frontals wrap over and nearly form a tunnel along the ventral orbital margin (Figure 11). At its caudal-most end, this lip remains a consistent height in Parahesperornis, while in Hesperornis it forms an exaggerated ventrally directed projection, best seen in lateral view (Figure 11C). At the caudal-most edge of the orbital margin the frontals narrow to a triangular projection with a facet for the postorbital process of the parietal (fpo in Figure 5). This facet is much more strongly developed in Hesperornis, where it is separated from the medial region of the frontals by a ridge that is only faintly visible in Parahesperornis.

Nasals. The nasals of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 are poorly preserved. Both the left and right are preserved crushed against the premaxillae, with the right more easily observed (Figure 7). For comparison, the nasals of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012, YPM 1206), the only other hesperornithiform from which nasals have been reported, were examined (Figure 12). The premaxillary and maxillary processes of the nasal of Parahesperornis (Np and Nm, respectively, in Figure 7) extend cranially in a similar orientation and run parallel to each other along their length, as in Hesperornis. A small foramen is present on the main body of the nasal at the juncture of these processes in both Parahesperornis and Hesperornis (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Comparison of the nasals of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (A) in lateral view (1) and Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (B) in lateral (1) and medial (2) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar size.

The dorsal surface of the premaxillary process of the nasal of Parahesperornis appears to have a broad, faint groove caudally, near the juncture with the maxillary processes, that flattens rostrally (g1 in Figure 7). In Hesperornis, the dorsal surface of the premaxillary process is flattened along its length with a similar groove along the dorsal-most edge that does not extend as far caudally as in Parahesperornis. The articulation between the maxillary processes of the nasal and premaxilla is clearly visible; the maxillary process of the premaxilla thins dramatically to a very thin sheet of bone that overlays the lateral face of the maxillary process of the nasal for a few centimeters, forming what Gingerich [58] termed a subnarial bar. Details of how this subnarial bar articulated with the maxilla are not well preserved in KUVP 2287. However, the ventral surface of the maxillary process of the right premaxilla appears to be flattened with a very faint caudal groove (g2 in Figure 7). Previously, Gingerich [58] identified the subnarial bar as sliding into a prominent groove developed on the dorsal margin of the maxilla from observations of Hesperornis YPM 1206. This is also seen in Hesperornis KUVP 71012, but a maxilla is not preserved (or is not complete enough to be identified) with KUVP 2287.

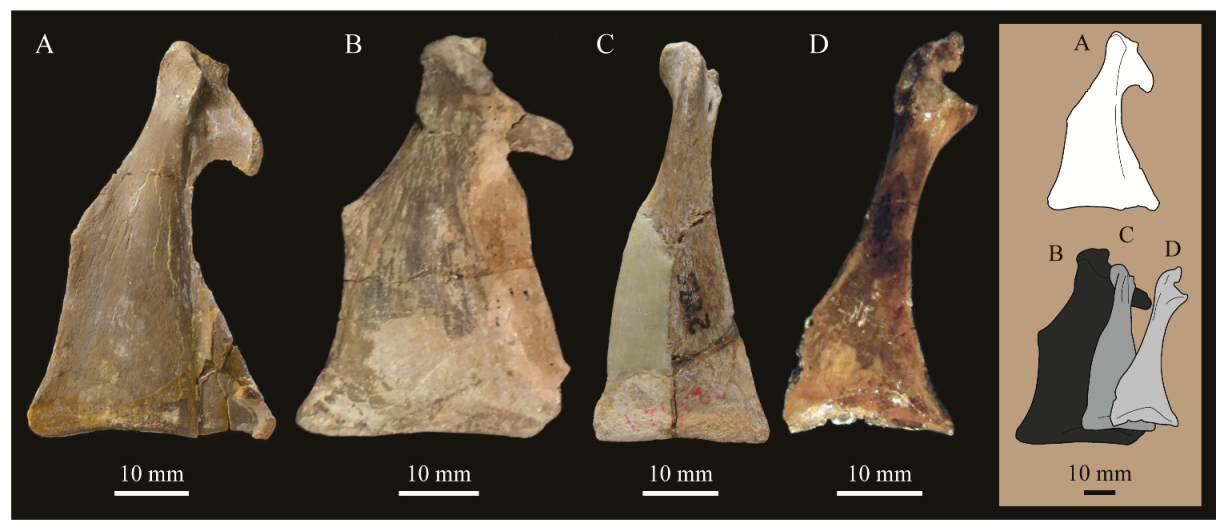

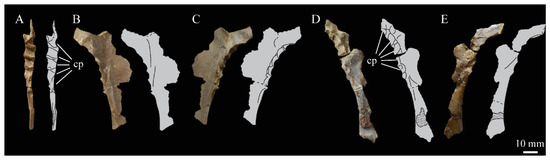

Lacrimals. Portions of both lacrimals are preserved with Parahesperornis KUVP 2287. The right lacrimal is nearly complete but lacks the cranial process (Figure 13), while the left consists of only a small fragment of the central region. For comparison, the lacrimals of Hesperornis KUVP 71012 were examined (Figure 14). The lacrimal of Parahesperornis is roughly T-shaped, with the caudal process extending dorsocaudally and the jugal process extending ventrally and slightly caudally.

Figure 13.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287 photographs (left) and line drawings (right) of the right lacrimal in lateral (A), cranial (B), caudal (C), medial (D), craniomedial (E), and dorsal (F) views. Abbreviations: cp—caudal process, f—foramen, jp—jugal process, ms—muscle scar.

Figure 14.

Comparison of the lacrimals of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1) and Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2) in medial (A), cranial (B), lateral (C), caudal (D), and dorsal (E) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar dorsoventral heights.

The lacrimal of Parahesperornis differs from that of Hesperornis in several respects. Overall, the lacrimal of Parahesperornis is much more elongate than that of Hesperornis, with a relatively narrow body and proportionally longer jugal process. The end of the jugal process in Parahesperornis terminates in an angled, flattened face with an upturned lip around the margin for articulation with the jugal. However, the jugal process of Hesperornis terminates in a pointed foot. At the base of the caudal margin of the jugal process, Parahesperornis has a muscle scar that is absent in Hesperornis. Additionally, in caudal view, the face of the jugal process of Parahesperornis is highly irregular, with a deep ovoid depression along its surface. In Hesperornis the corresponding area is narrow and rounded, with only a slight depression centered at the distal end.

In lateral view, the side of the lacrimal of Parahesperornis has an ovoid depression that appears to shallow rostrally, such that it would not have extended beyond the broken edge of the cranial process. This region is more deeply excavated in Hesperornis, where it forms a groove that parallels the dorsal margin of the body of the lacrimal. Also in lateral view, the caudal process forms a dorsal curve in Parahesperornis but angles dorsally in a straight line in Hesperornis.

Witmer [75] established that the lacrimals of both Hesperornis and Parahesperornis are pneumatic. In Parahesperornis a large, funnel-like opening is present on the caudal margin of the depression in the lateral face of the lacrimal (best seen in craniomedial view, Figure 13E). In Hesperornis, the external evidence of this pneumaticity is limited to a small foramen located in the middle of the medial face of the lacrimal.

The overall shape of the lacrimal, and in particular the elongation of the jugal process, in Parahesperornis is similar to that of other Mesozoic ornithuromorphs (e.g., Ichthyornis [61] and Dingavis [76]), which share an overall T-shaped morphology with Archeopteryx [77], reflecting the ancestral state in birds. This highlights the more compact lacrimal of Hesperornis, with a shortened jugal process, as an autapomorphy among Mesozoic birds.

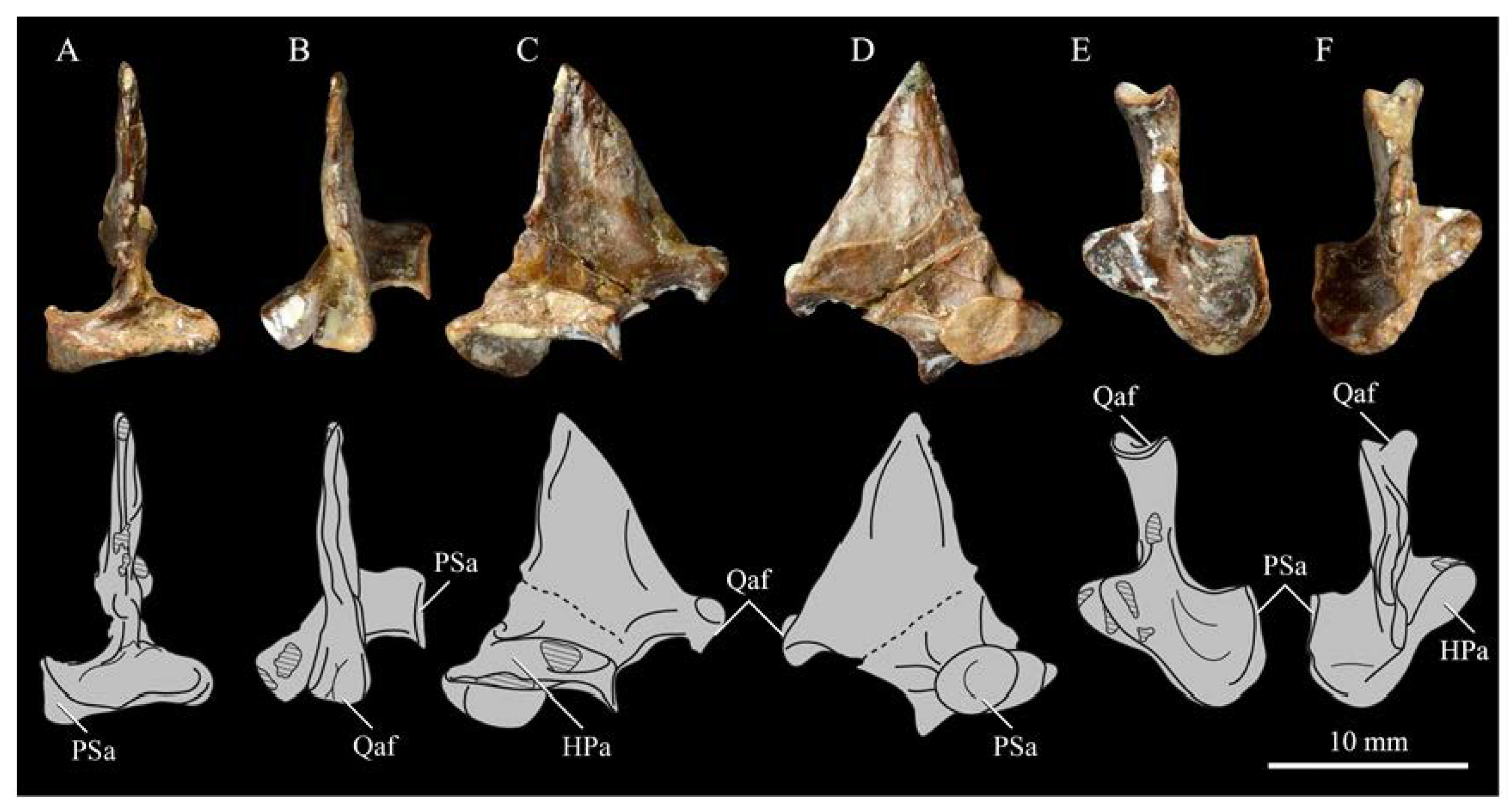

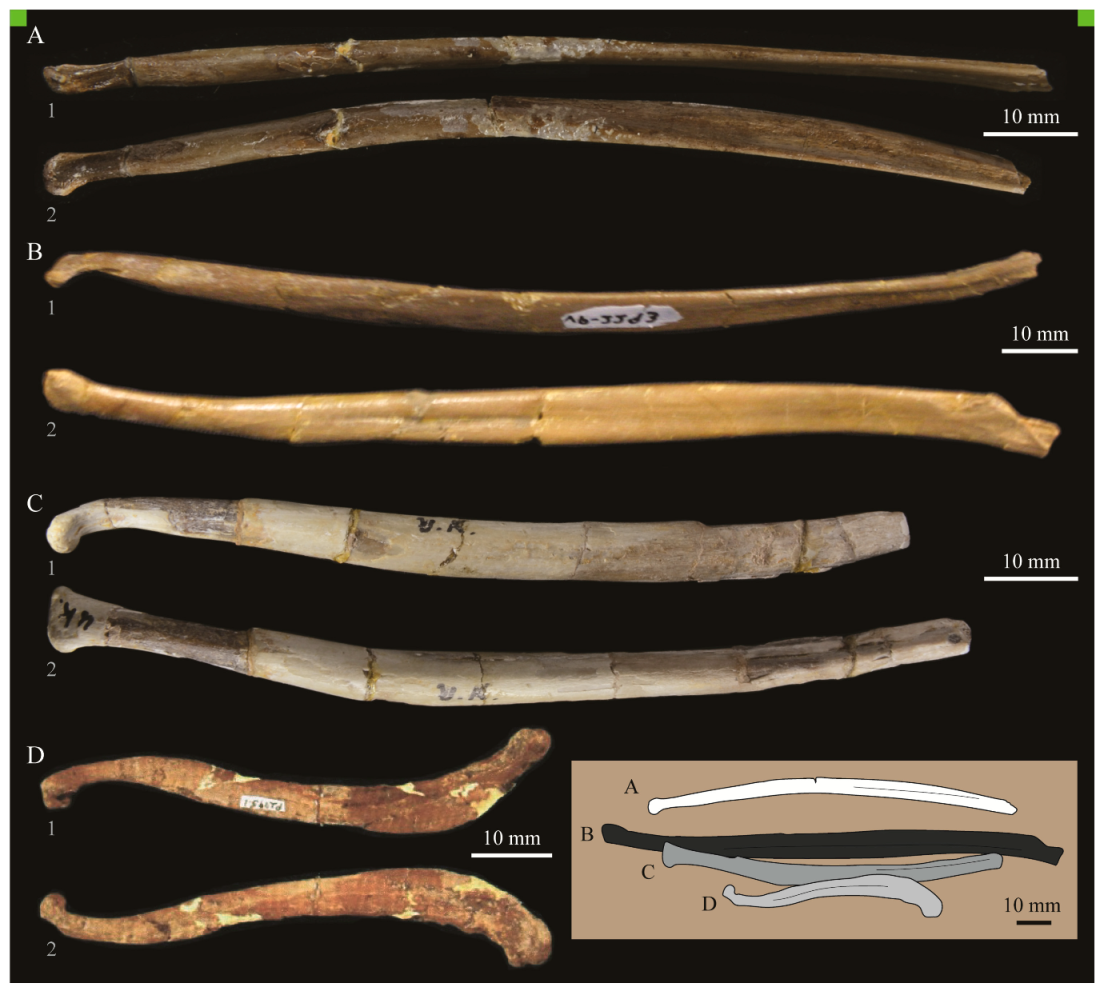

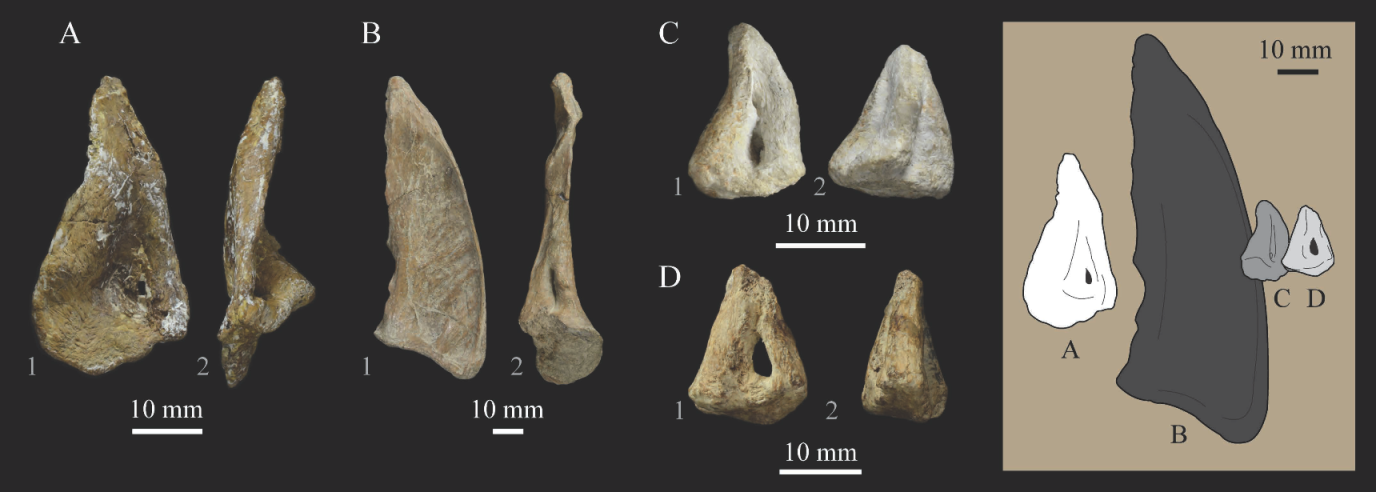

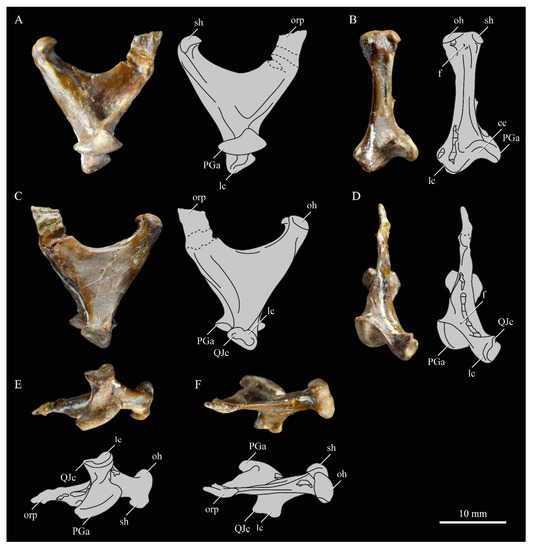

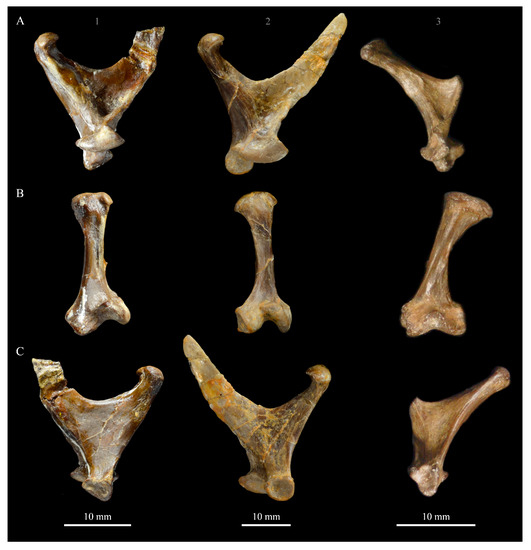

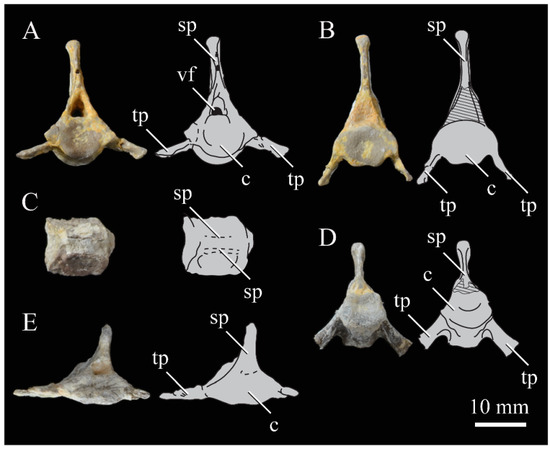

Quadrate. Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 preserves the complete left quadrate (Figure 15) and fragments of the otic process and dorsal articular region of the right quadrate. In addition to Hesperornis (KUVP 71012), a well-preserved quadrate is also known for Potamornis [49] (UCMP 73013) (Figure 16), and two poorly preserved quadrates have been reported for Pasquiaornis (RSM P2988.25, RSM P2831.52) [65]. As discussed above, a partial quadrate previously described [19] as belonging to Baptornis (AMNH 5101) was likely a mistaken attribution [49]. Anatomical terminology for the discussion of the quadrate comes from Elzanowski [49], who expanded upon the terminology of Baumel and Witmer [67]. In general, the quadrates of hesperornithiforms are similar, with some minor differences in proportion and details of morphology, and much like those of modern birds and Ichthyornis.

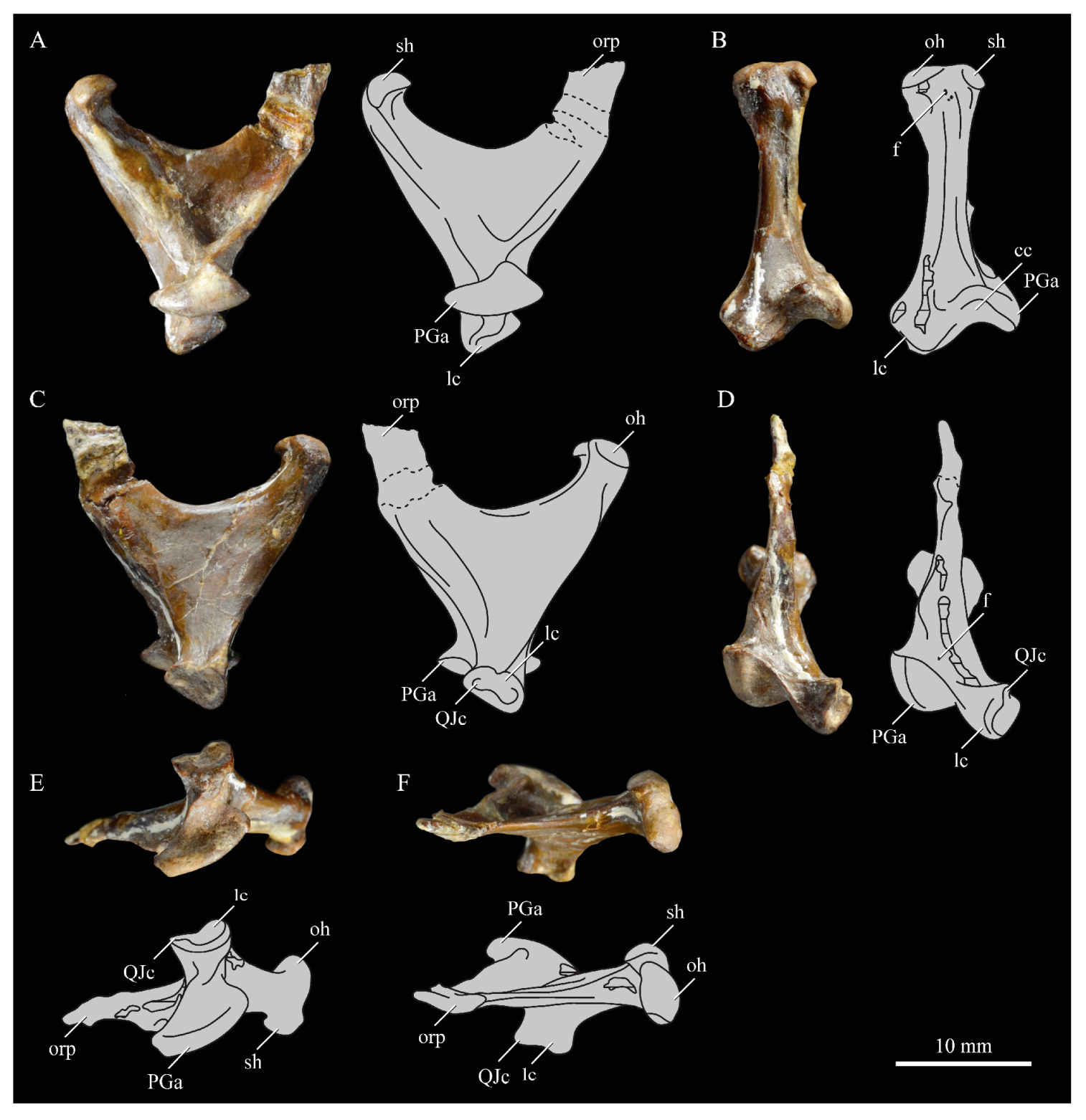

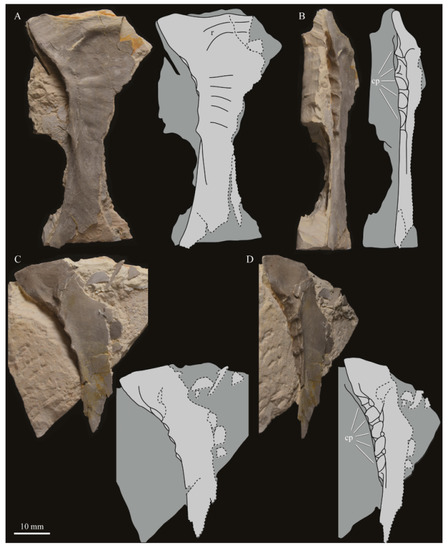

Figure 15.

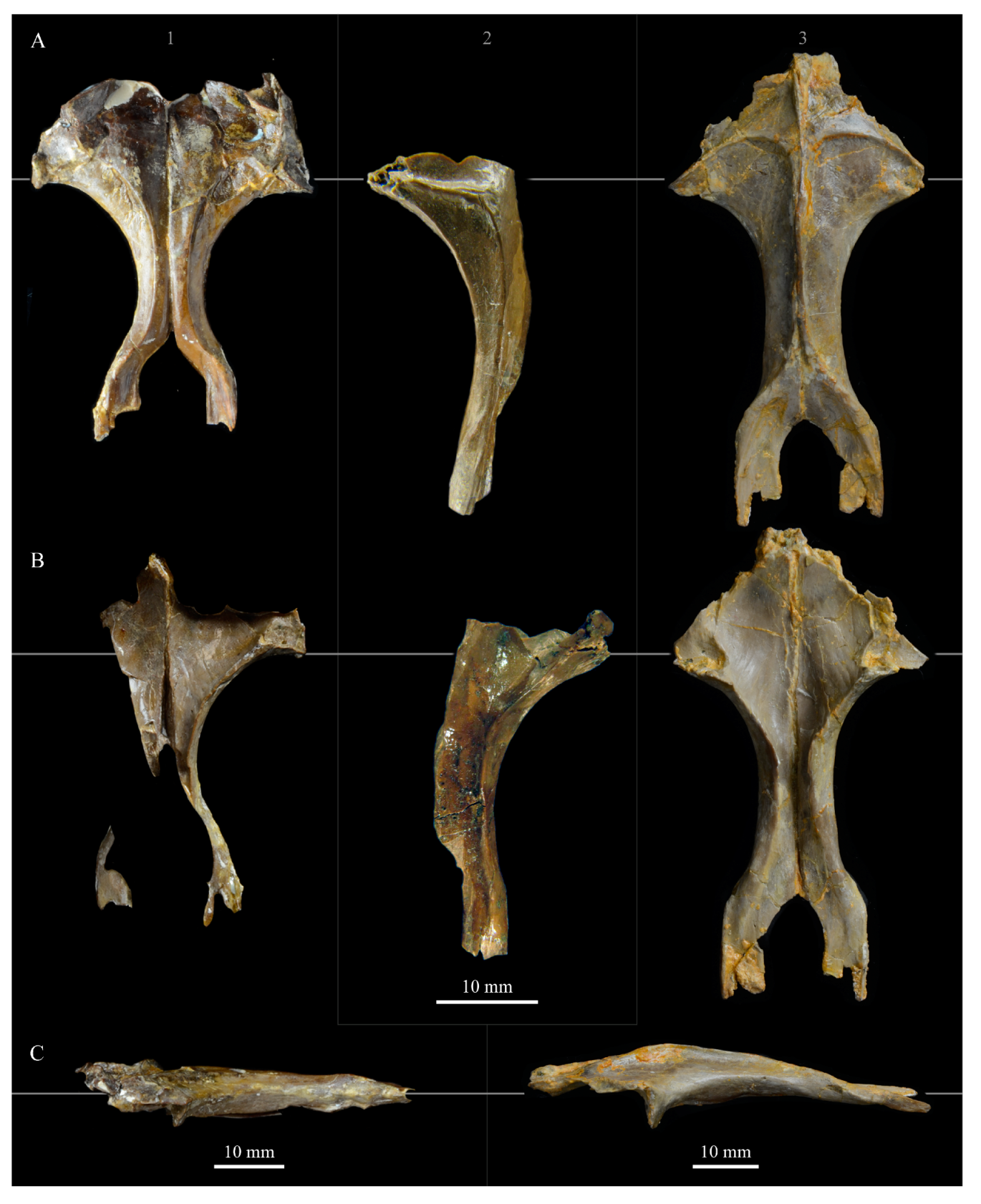

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, photographs (left) and line drawings (right) of the left quadrate in medial (A), caudal (B), lateral (C), rostral (D), ventral (E), and dorsal (F) views. Abbreviations: cc—caudal condyle, f—foramen, lc—lateral condyle, oc—otic head, or—orbital process, PGa—pterygoid condyle, QJc—quadratojugal cotyla, sc—squamosal head.

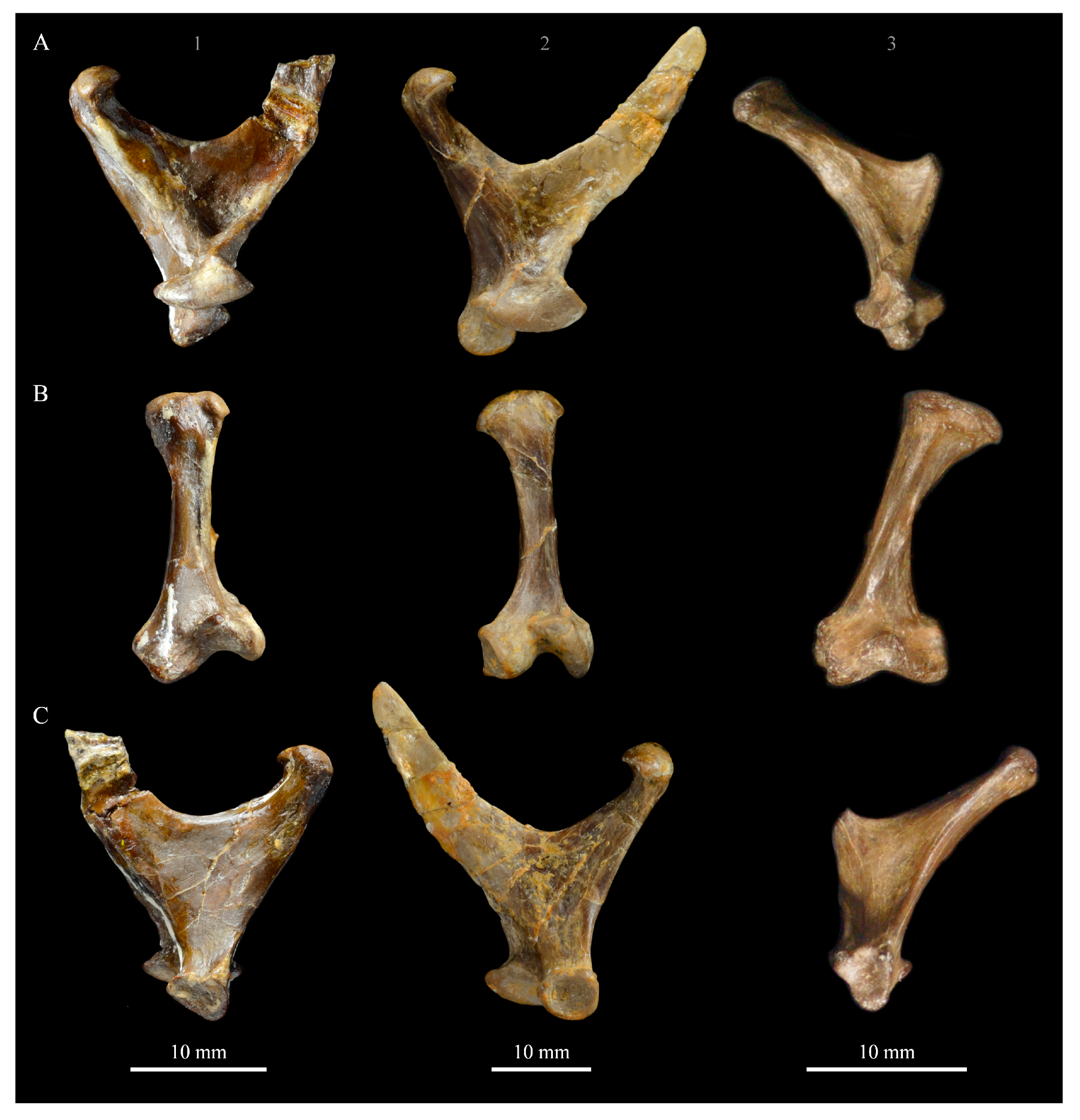

Figure 16.

Comparison of the quadrates of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1), Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2), and Potamornis UCMP 73013 (3) in medial (A), caudal (B), and lateral (C) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar height at the caudal end and aligned at the top of the head.

The otic process of the quadrate is poorly divided in Parahesperornis, as in other hesperornithids and modern paleognathes, but unlike the better defined otic and squamosal head in Ichthyornis and many modern birds. The otic head is slightly smaller than the squamosal head, while in Hesperornis and Potamornis the otic head is much smaller than the squamosal. While the quadrate of Enaliornis is not known, the division of the quadrate’s articular facet on the squamosal into visible medial and lateral cotylae indicate the otic and squamosal heads of the quadrate of Enaliornis may have been better divided.

In caudal view, the intercapitular incision wraps down onto the caudal face of the otic process and around the ventral margin of the otic head forming a caudomedial depression. This depression is much better developed in Parahesperornis than in Potamornis, while in Hesperornis the depression is absent. In medial view the otic process hooks backward over the neck and projects rostrally, as in Hesperornis and unlike Potamornis, where it is not hooked at all. In both Parahesperornis and Hesperornis, a small pocket is present beneath the lip of the head on the rostral surface of the neck. The neck is more robust in Parahesperornis and Potamornis, where it narrows very little before the otic process, while in Hesperornis the neck is more restricted.

The dorsal margin of the quadrate, between the otic process and the orbital process, is broad and u-shaped in Parahesperornis, while in Hesperornis it is slightly deeper (resulting from the longer neck of the otic process in Hesperornis) and more v-shaped. The orbital process of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 lacks the anterior end, but the preserved portion is very thin mediolaterally and tapers anteriorly, as in Hesperornis. Elzanowksi reported the orbital process of Potamornis as only missing the anterior-most end. If this is true, then the orbital process was dramatically reduced in Potamornis as compared to hesperornithids. The thin, flattened orbital process plays a role in the mobility of the quadrate, as that is where the m. protractor pterygoidei et quadrati, which pulls the quadrate dorsorostrally, inserts, and the m. pseudotemporalis profundus, which adducts the mandible [78], originates [57].

In medial view, the body of the quadrate of Parahesperornis just above the medial condyle is deeply excavated in a triangular pocket, as in Pasquiaornis. Potamornis has a shallow depression in this area, while the corresponding region in Hesperornis is only faintly depressed. In lateral view the body of the quadrate of Parahesperornis is fairly featureless and flat, while in Hesperornis and Potamornis the central region is slightly depressed. Also in Hesperornis and Potamornis, the neck is slightly twisted, such that the lateral crest crosses the lateral face just below the otic process, while in Parahesperornis the lateral crest is restricted to the lateral margin.

The caudal condyle on the mandibular process of Parahesperornis is small and thin, located to the medial side of the distocaudal surface. In Hesperornis this condyle is more robust, present as a thick, triangular projection that occupies most of the caudal surface of the pterygoid condyle. Potamornis has a small caudal condyle, similar in size to that of Parahesperornis, but developed as a hook projecting caudodorsally, unlike in other hesperornithiforms.

The pterygoid condyle is very well-developed and like that of modern birds. In Parahesperornis and Potamornis the pterygoid condyle is broad and triangular, while in Hesperornis it is oval with a slightly concave surface. The medial condyle of Parahesperornis, Potamornis, and Pasquiaornis is elongate and narrower at the caudal end than at the rostral end, with a slightly convex dorsal margin. That of Hesperornis is more uniform in width with much deeper curvature along the dorsal margin.

The lateral condyle of Parahesperornis is narrower rostrocaudally than the pterygoid condyle, with an oval quadratojugal cotyla facing laterally and slightly rostrally. The margins of the cotyla are slightly pinched in toward the rostral end, creating a rostral projection that may correspond to the quadratojugal buttress identified in Potamornis by Elzanowski [49]. The quadratojugal cotyla is nearly circular in Hesperornis, where it faces directly laterally. That of Potamornis is oval in shape, however the long axis of the cotyla is oriented dorsoventrally, while in Parahesperornis the long axis is oriented rostrodorsally to caudoventrally. The pneumaticity of the quadrate in hesperornithids was discussed by Witmer [75] and Elzanowski [49]. A single visible pneumatopore is located on the middle portion of the caudal face of the quadrate of Parahesperornis. In Hesperornis this pneumatopore is displaced toward the distal end. In Potamornis no foramen is visible in this area.

Palatines. The palatines of Parahesperornis and Hesperornis have been somewhat contradictorily described by previous authors. What Marsh [7] initially identified as a vomer of Hesperornis (YPM 1206), Gingerich [58], working with both KUVP 2287 and YPM 1206, later described as a palatine, and what Marsh [7] referred to as a palatine Gingrich [58] described as a vomer. Gingerich [58,69] described the palatine as articulating with the pterygoid and tapering anteriorly to where it is fused with the vomer. There is no evidence of this relationship preserved today with Parahesperornis KUVP 2287. Working with KUVP 2287 before it was disarticulated, Gingerich [69] described both palatines as “virtually complete” and identified the left palatine as preserved alongside the frontals and a portion of the right palatine alongside the premaxilla (see Figure 4).

In his palatal reconstruction, Gingerich [69] placed the palatines as articulating with the pterygoids (Figure 4). While work by Witmer and Martin [70] supported Gingerich’s interpretation, later work by Elzanowski [71] rejected Gingerich’s [69] reassignment of the bones of YPM 1206 as the palatine and vomer, reverting to Marsh’s [7] original identifications. While Elzanowski did not specifically identify these elements in KUVP 2287, the bones identified as the palatines by Gingerich [58,69] in his reconstruction would be equivalent to the hemipterygoids of Elzanowski [56]. The present study supports Elzanowski’s interpretation of the hemipterygoids.

Today, a portion of the left palatine is preserved pressed against the ventral side of the frontals of KUVP 2287 (PT in Figure 5). The identification of the palatine of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 as supported by this study is based on the distinctive hook present at the cranial end of this bone, which is difficult to interpret as belonging to any other element. The remainder of this palatine is difficult to identify. Historic photos demonstrate that the small rod preserved alongside this hook is not associated with the palatine and is instead most likely the hemipterygoid (see discussion above). It seems likely that some portion of the palatines is preserved in the jumble of thin bones crushed into the ventral surface of the premaxillae (Figure 7), however precisely identifying these bones is not possible.

The preserved portion of the left palatine of Parahesperornis consists of a small, caudally directed hook, somewhat crushed into the shaft, which is elongate and very thin mediolaterally. The hook is much more compact than that of Hesperornis, which is elongate and reaches back further over the shaft (Figure 17). The midsection of the shaft of the left palatine of Parahesperornis, immediately rostral to the hook, appears to have a weakly-developed groove, which is more clearly seen in Hesperornis.

Figure 17.

Palatine of Hesperornis KUVP 71012 showing caudally directed hook (1) and isolated tooth (2).

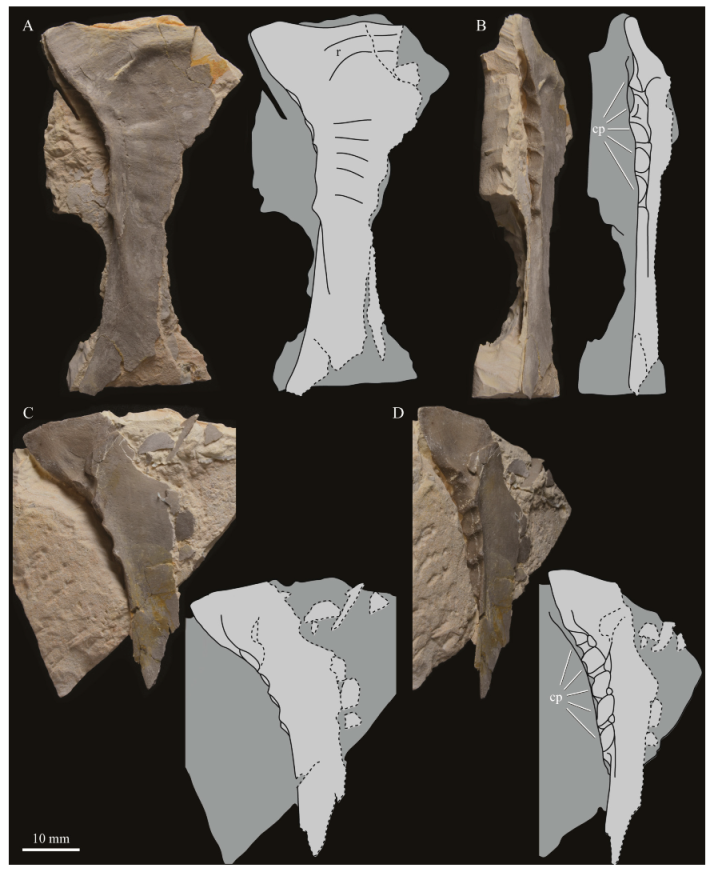

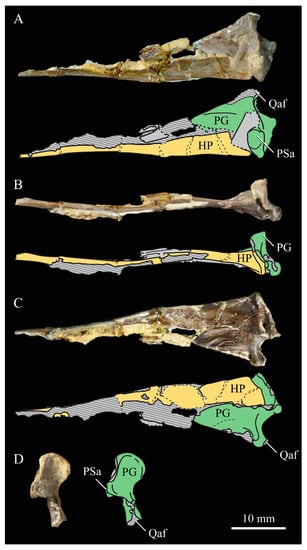

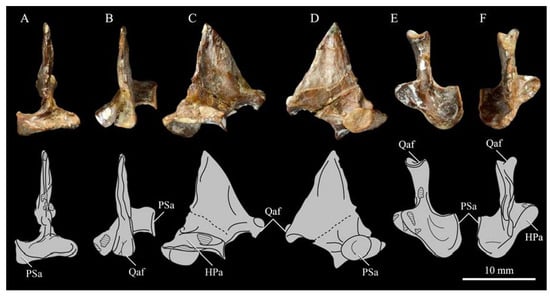

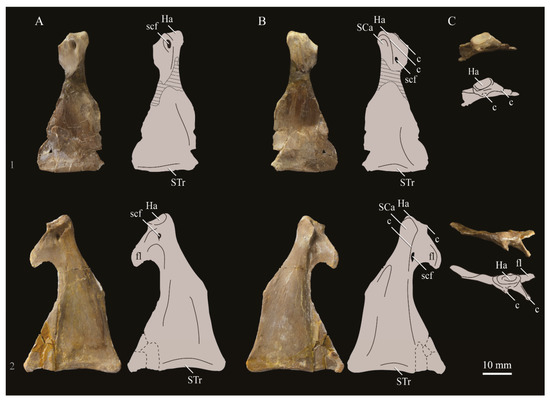

Pterygoids. Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 preserves both pterygoids; the right is articulated with the right hemipterygoid (Figure 18), while the left is disarticulated (Figure 19). For comparison the pterygoid of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012, YPM 1206) was examined (Figure 20). The body of the pterygoid of Parahesperornis is triangular and very thin, with nearly flat sides. In Hesperornis, the sides are not as flat, with a depression near the articulation for the quadrate on the medial face and a broad groove developed dorsoventrally across the lateral face. The ventral margin of the lateral face of the pterygoid in Parahesperornis forms a broad, flattened c-shape, while in Hesperornis it is a deep, nearly enclosed u-shape.

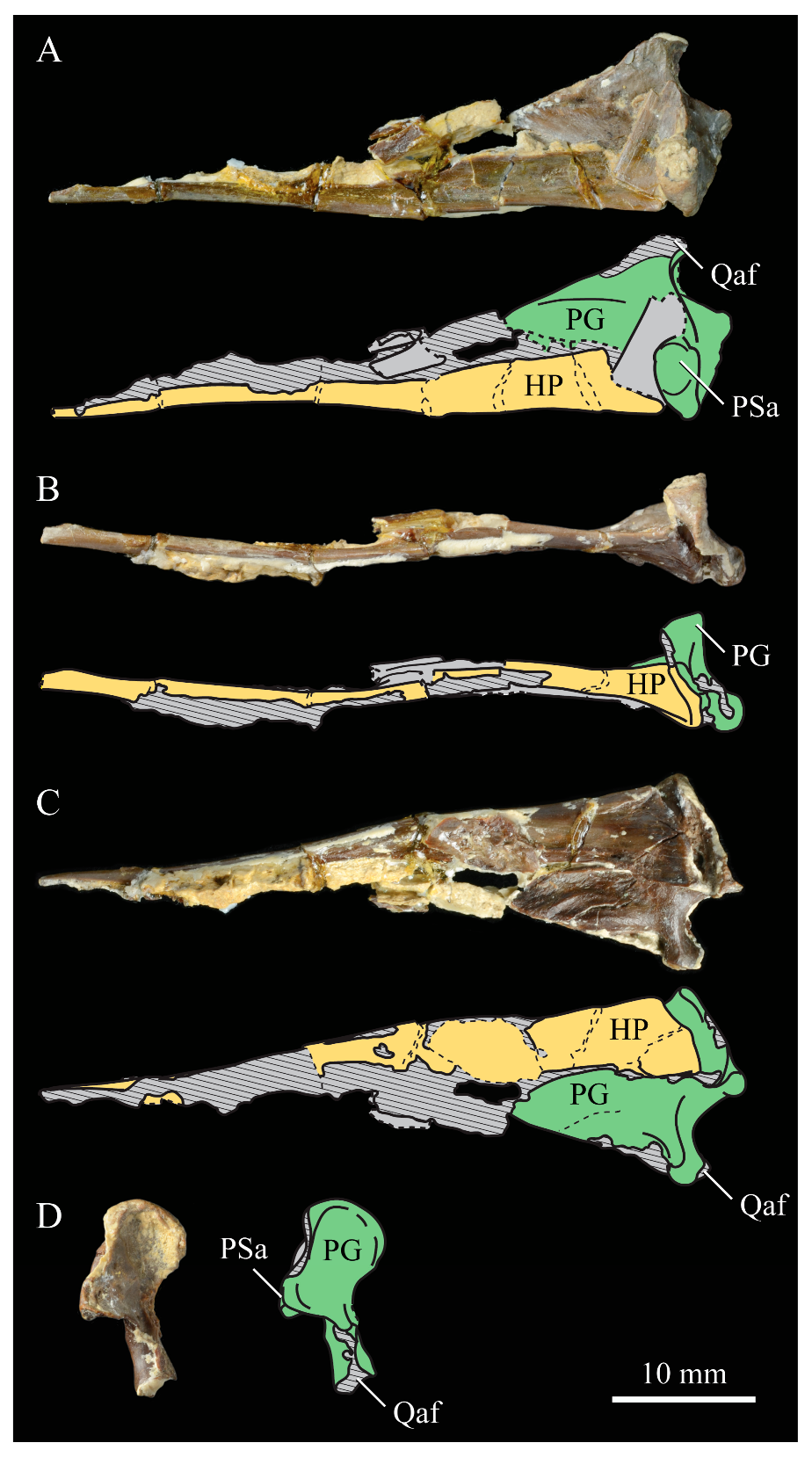

Figure 18.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, photographs (upper) and line drawings (lower) of the right pterygoid and hemipterygoid in medial (A), rostral (B), lateral (C), and ventral (D) views. Color coding: green—pterygoid; yellow—hemipterygoid; grey—unknown; cross-hatching—matrix. Abbreviations: HP—hemipterygoid, PG—pterygoid, PSa—parasphenoid articulation, Qaf—quadrate articular facet.

Figure 19.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, photographs (upper) and line drawings (lower) of the left pterygoid in rostral (A), caudal (B), lateral (C), medial (D), ventral (E), and dorsal (F) views. Abbreviations: HPa—hemipterygoid articulation, PSa—parasphenoid articulation, Qaf—quadrate articular facet.

Figure 20.

Comparison of the left pterygoid of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1) and right pterygoid of Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2) in lateral (A), medial (B), ventral (C), and dorsal (D) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar size and aligned at articular facets.

The ventral surface of the pterygoid of Parahesperornis is semicircular and shallowly depressed with a thin crest along the lateral margin, while in Hesperornis it is almost rectangular with a thickened lateral margin bordered by a deep recess. The quadrate articulation of the pterygoid of Parahesperornis is a tiny facet at the caudal end of the triangular body that is more shallowly excavated than in Hesperornis. In Hesperornis a small pointed process is present on the medioventral margin of the pedicel for the parasphenoid articulation (best seen in dorsal view), however this process is absent in Parahesperornis, where the margin is smoothly rounded. In caudal view, the palatine articulation is more concave in Parahesperornis and flattened in Hesperornis with a well-developed lip around the caudodorsal margin.

Hemipterygoid. Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 preserves both hemipterygoids; the left is preserved alongside the braincase and frontals and overlapping the left palatine (Figure 5), while the right is preserved separately and articulated with the right pterygoid (Figure 18). For comparison, the hemipterygoid of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012) was examined (Figure 21). While the left hemipterygoid identified here was described by Gingerich [69] as the left palatine, the preserved caudal end agrees much more with that of the right hemipterygoid, as both have a rounded ventral margin and an angled caudal margin.

Figure 21.

Comparison of the hemipterygoids of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1) and Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2) in lateral (A) and medial (B) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar size, with the overlapping pterygoid digitally removed from 1.

The hemipterygoid is a very long, thin bone that widens caudally at the articulation with the pterygoid. This caudal expansion is more dramatic in Parahesperornis than in Hesperornis. The hemipterygoid appears not to have been fused or strongly sutured to the pterygoids, as indicated by the disarticulation of the elements. At the caudal end, the lateral and medial surfaces are relatively flat in Parahesperornis, while in Hesperornis the lateral surface is rounded and the medial is broadly indented.

Premaxilla. The premaxillae of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 were preserved in articulation with the bulk of the skull (Figure 4) and are slightly crushed dorsoventrally and to the left side (Figure 7). The caudal ends appear to narrow before the broken ends, indicating that perhaps not much length has been lost due to breakage. For comparison the premaxilla of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012, YPM 1206) was examined (Figure 22). Despite being of a similar width at the rostral end of the nares as Hesperornis (and accounting for the slight crushing to the element), the length from the tip of the premaxilla to the opening of the nares is much shorter in Parahesperornis (width at the nares is approximately 35% the pre-nares length) than in Hesperornis (width at the nares is approximately 20% the pre-nares length), implying a more elongate skull in the latter.

Figure 22.

Comparison of the premaxillae of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1) and Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2) in dorsal (A), right lateral (B), ventral (C), and left lateral (D) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar width at the opening of the nares and aligned at the rostral end of the nares.

The premaxillae are edentulous with a straight tomial margin, ending in a slight terminal hook, similar to that in Hesperornis and other Mesozoic ornithuromorphs (Dingavis [76], Changzuiornis [79]) but much shallower than in Ichthyornis. The premaxillae of hesperornithids were quite long and narrow, making up close to half the length of the rostrum, as compared to the shorter premaxillae in some other ornithuromorphs (i.e., Ichthyornis, Yanornis). This is likely a foraging adaptation for the marine lifestyle of hesperornithiforms. Across Mesozoic birds, lengthening of the rostrum is commonly accomplished by lengthening of the maxilla, contrasted by the elongation of the premaxilla common in Neornithes [76]. While the maxilla does not appear to be preserved in Parahesperornis KUVP 2287, Hesperornis KUVP 71012 preserves a fairly complete maxilla that indicates Hesperornis achieved rostral elongation in the same way that modern birds do, through elongation of the premaxillae, and unlike the maxillary elongation documented in other Mesozoic birds [76].

In dorsal view, the suture between the left and right premaxillae of Parahesperornis is obvious caudally along the entire length of the frontal processes; it becomes fainter rostrally, disappearing about an inch before the rostral-most extent of the premaxillae. In Hesperornis, this suture is not visible for as much of its length. Both birds have a series of pinhole neurovascular foramina dotting the rostral-most end of the premaxilla, possibly indicating the presence of a keratinized ramphotheca. The maxillary process of the premaxilla is articulated to the maxillary process of the nasal in Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (Figure 7). In ventral view the premaxillae of Parahesperornis lack impressions for the fitting of the dentary teeth, which are visible in Hesperornis and some other toothed birds (e.g., Ichthyornis). Both Parahesperornis and Hesperornis have a small pair of teardrop-shaped pits in the very tip of the ventral premaxillae (f in Figure 7).

Mesethmoid. A bone which may represent the mesethmoid in Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 is preserved crushed against the ventral surface of the frontals, adjacent to the palatine (ME in Figure 5). If this identification is correct, then the bone is lying on its side and has been crushed into the frontals. This bone is broad along the dorsal margin and narrow at the ventral edge. This is similar to the more complete mesethmoid of Hesperornis as preserved with KUVP 71012 (Figure 23).

Figure 23.

Mesethemoid of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012) in left lateral (A), rostral (B), and dorsal (C) views.

The mesethemoid has been reconstructed as fitting into the gap between the separate rostral-most ends of the frontals [57], terminating at the anterior end of the frontals, as has recently been described for Ichthyornis [61]. Unfortunately, the degree of crushing in KUVP 2287 does not provide additional information about this arrangement, however the current placement of the mesethemoid and the degree of separation of the frontals does not contradict this interpretation.

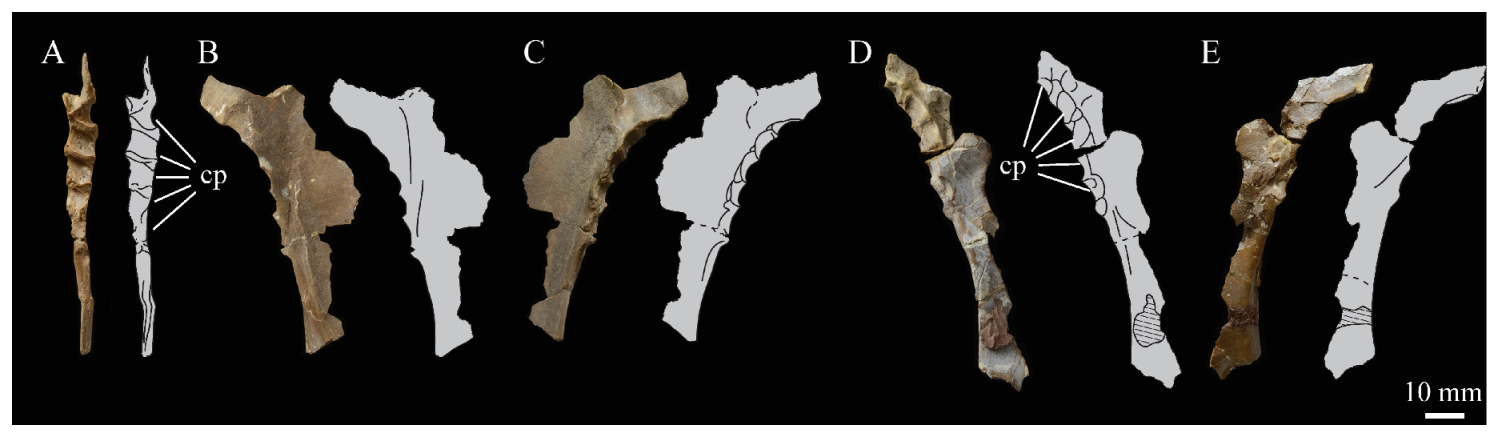

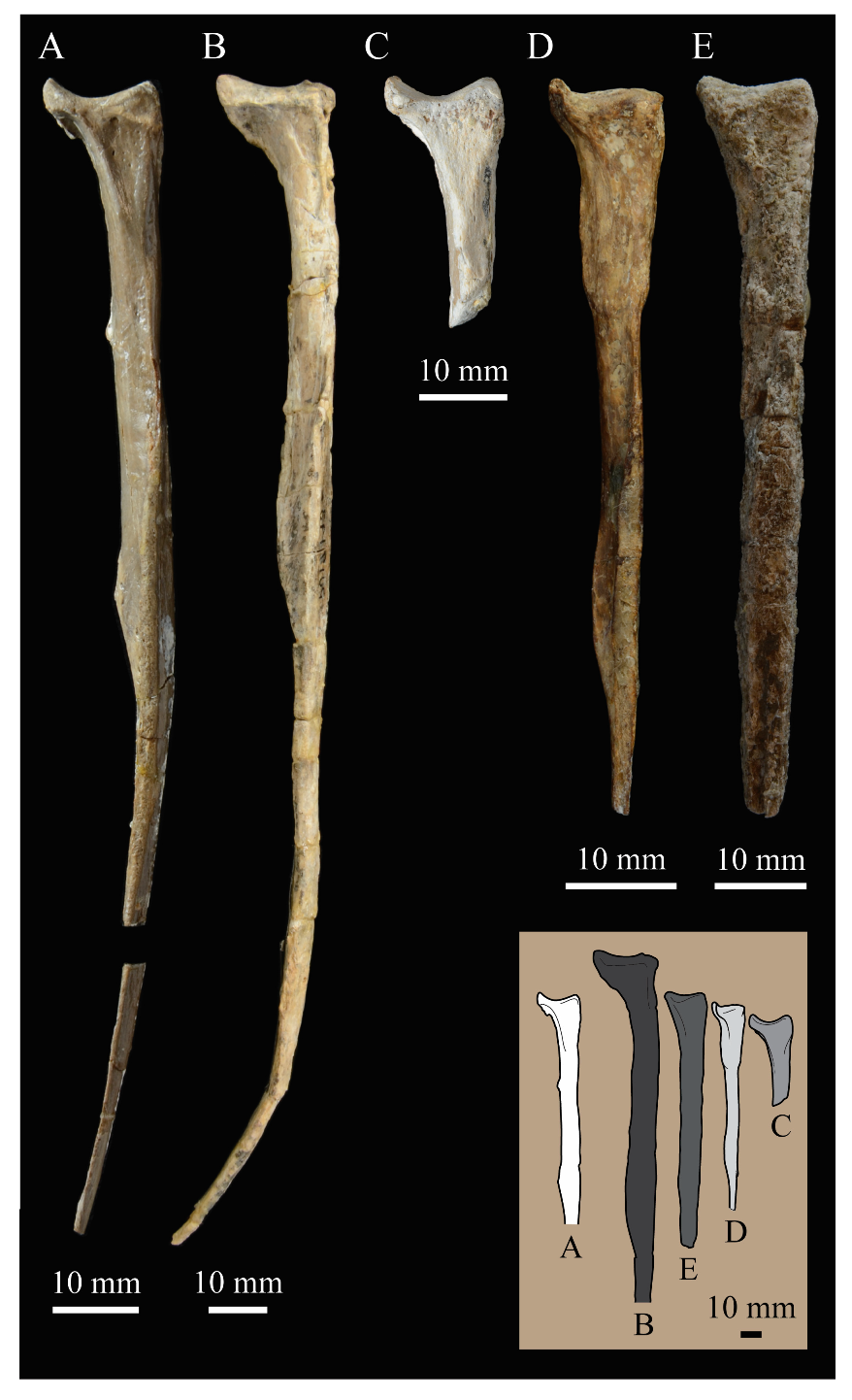

Angulars. Both angulars of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 are preserved and have been glued into rough articulation with the articulars and surangulars (Figure 24). For comparison the angular of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012, YPM 1206) was examined (Figure 25). While angulars have been assigned to Pasquiaornis [65], these bones are highly fragmentary and provide little comparative information.

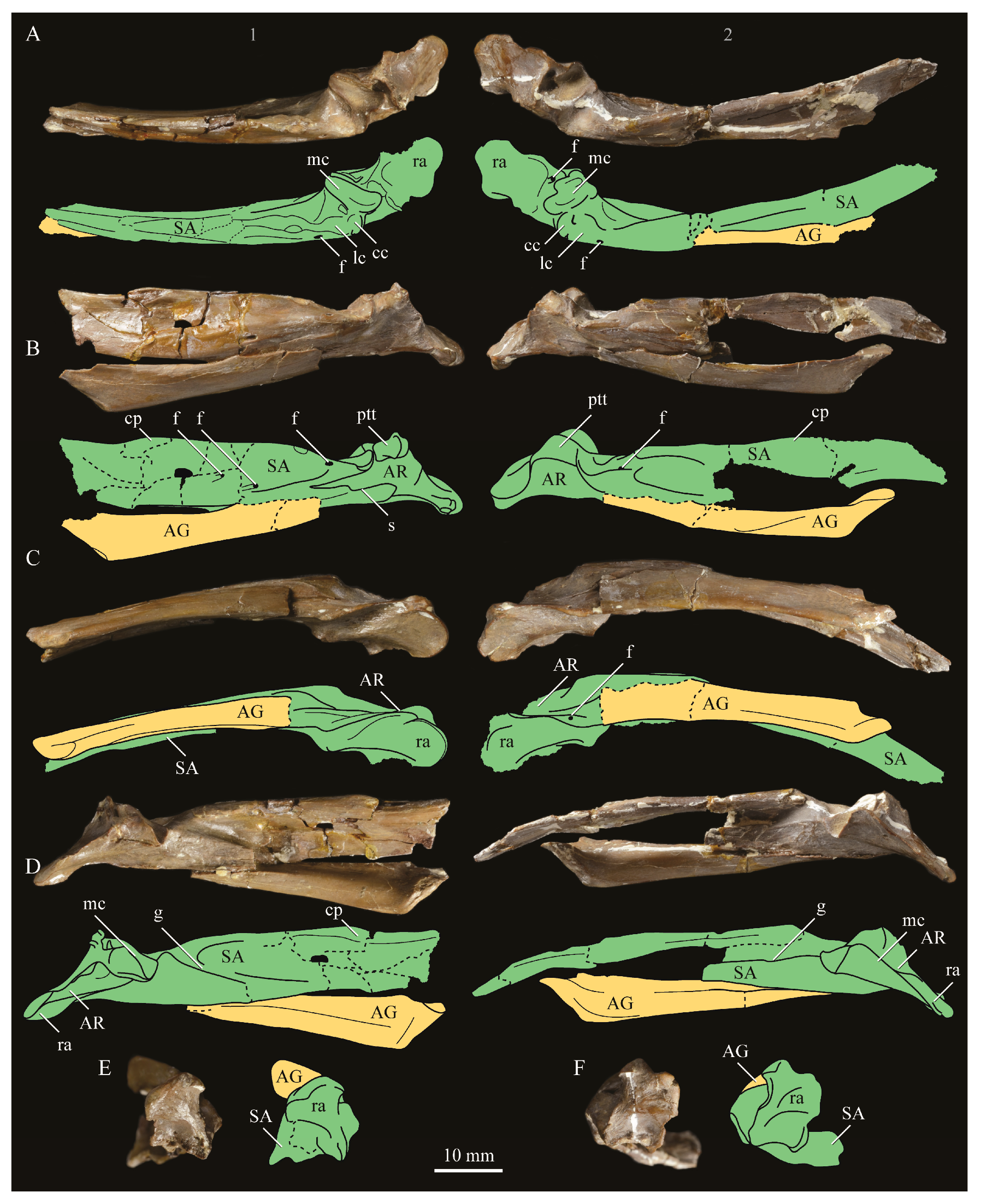

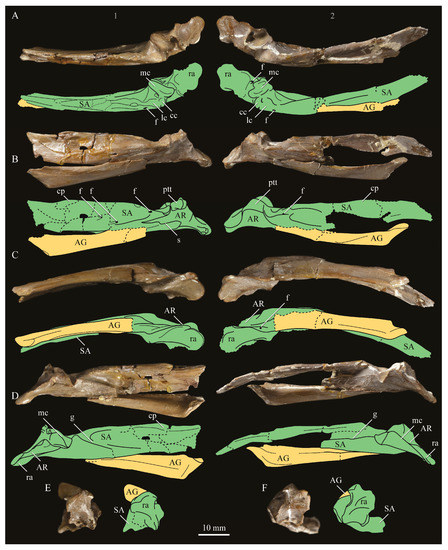

Figure 24.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, photographs (upper) and line drawings (lower) of the left (1) and right (2) articulated angulars, surangulars, and articulars of the mandible in dorsal (A), lateral (B), ventral (C), medial (D), and caudal (E,F) views. Abbreviations: AG—angular, AR—articular, cc—caudal cotyla, cp—coronoid process, f—foramen, g—groove, lc—lateral cotyla, mc—medial cotyla, ptt—pseudotemporale tubercle, ra - retroarticular process, s—suture, SA—surangular.

Figure 25.

Comparison of the left angulars, surangulars, and articulars of Parahesperornis (KUVP 2287; (1) and Hesperornis (KUVP 71012; (2) in medial (A), dorsal (B), lateral (C), and ventral (D) views. Specimens are scaled to be of similar size and aligned at the medial cotyla of the articular.

The angular of Parahesperornis is straight along its ventral margin and bows slightly in dorsal or ventral view, as in Hesperornis. The articular surfaces are somewhat obscured caudally by the surangulars. In medial view, the articular surface forms a faint, broad ridge bounded laterally by the thin, flat lateral side of the bone. At the caudal-most end, the articular surface transitions to a flat, dorsally facing surface that is glued onto the surangular in KUVP 2287. In Hesperornis the surangulars are disarticulated, making the entire articular surface visible. The caudal-most end of this articular surface is broad and concave, narrowing rostrally and developing a lateral ridge as in Parahesperornis. However, at the rostral-most end the articular surface of Hesperornis forms a slightly expanded, concave surface unlike the flattened surface of Parahesperornis. The morphology of the dorsal surface implies that the angular Parahesperornis articulated with the surangular through a broader, sheeted surface along its length, while that of Hesperornis was somewhat more restricted to the concave surface.

It should be noted that due to the breakage of the ventral margin of the surangular, the angulars of KUVP 2287 have been glued on imperfectly. The present reconstruction of the left, and more complete, mandible has a slight gap between the surangular and rostral angular. This gap has also been figured in reconstructions of the lower jaw of Hesperornis that were based off this specimen [58,59]. However, the surangulars and angulars of Hesperornis KUVP 71012 are complete enough to allow a good articulation, and the angular fits smoothly and completely over the surangular, with no gap.

Surangulars. The surangulars of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 are preserved in articulation with the articulars and glued to the angulars but crushed and poorly preserved (Figure 24). For comparison the surangulars of Baptornis (FMNH 395) and Hesperornis (KUVP 71012, YPM 1206) (Figure 25) were examined. The surangular of Parahesperornis is a very thin bone that articulates with the dorsal surface of the articular just cranial to the pseudotemporale tubercle, where a suture is visible (Figure 24). In dorsal view, both surangulars of Parahesperornis are convex, bowing out laterally to a much greater degree than in Hesperornis.

The medial face of the surangular of Parahesperornis has a broad, shallow depression. A mandibular foramen is not present. The mandibular foramen is also absent in Hesperornis, contra Marsh7. A slight groove is present running diagonally from the ventral margin to the dorsal margin, opening into this depressed area. In Hesperornis this groove is not present, and the depression on the medial face is much more deeply excavated than in Parahesperornis. The lateral face of the right surangular of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 preserves three foramina, one located near the dorsal margin by the articular and two nearly centered on the lateral surface. While the foramen near the dorsal margin is not present in Hesperornis, the central ones are visible in a similar location. The surangular of Baptornis is minimally preserved, with FMNH 395 only preserving the caudal-most end, which is fully fused to the angular, with a groove marking this fusion in medial view, as in hesperornithids.

Articulars. Both articulars of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 are preserved in articulation with the surangulars (Figure 24). For comparison the articulars of Baptornis (FMNH 395), Hesperornis (KUVP 71012; Figure 25), and Pasquiaornis (RSM P2989.21, RSM P2989.19) [65] were examined. The retroarticular process of Parahesperornis is somewhat oval and dorsally concave, with raised edges that almost form a lip, while that of Hesperornis appears to be proportionally broader and flatter. The retroarticular process of Parahesperornis is extremely elongate, slightly more so than in Hesperornis, however the elongation in both taxa is extreme compared to modern birds. The retroarticular process in Baptornis is more like that of modern birds, with the caudal end the same width as the remainder of the element and extending only slightly caudally beyond the cotylae. The articular is not fully fused to the surangular, with a suture visible in both Parahesperornis and Hesperornis. In Baptornis these elements appear fully fused, with no suture present, at least at the preserved caudal end.

Rostral to the retroarticular process is a small but very deep depression separating the retroarticular process from the medial articular cotyla of the quadrate articulation. This deep fossa is not present in Hesperornis or Baptornis but is in Pasquiaornis. The medial cotyla is developed as a deep groove oriented almost transversely and angled such that the lateral edge is ventral to the medial edge. In Hesperornis the medial cotyla is oriented even more transversely than in Parahesperornis. The degree of excavation of the medial cotyla is highest in Parahesperornis, reduced but still prominent in Hesperornis and Pasquiaornis, and faint in Baptornis. This cotyla is located primarily on the dorsal surface of the mandible in Parahesperornis, as is also the case in Baptornis, but slightly more offset to the medial side of the mandible in Hesperornis and located almost entirely on the medial side of the mandible in Pasquiaornis.

Medial and slightly rostral to the medial cotyla in Parahesperornis, the caudal cotyla is developed as a small oval facet that is bounded by prominent ridges on all but the rostral margin, which is indistinct. The caudal cotyla in Hesperornis is directly medial to the medial cotyla and not offset rostrally. It is only faintly developed and lacks the prominent margins in Parahesperornis. The caudal cotyla is not discernible in Baptornis FMNH 395. The lateral cotyla of Parahesperornis is very faint and not clearly divided from the caudal, constituting a very faint, flattened face rostral to the caudal condyle. This is also true for Hesperornis.

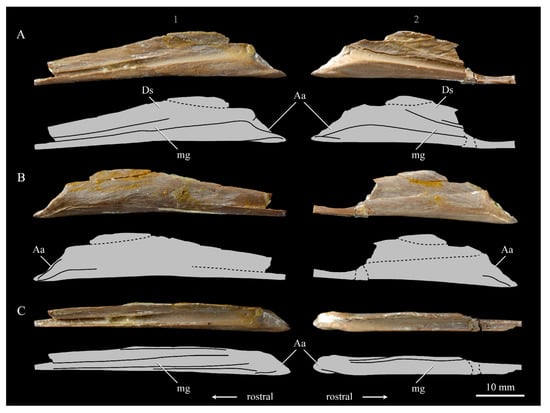

Splenials. Portions of both splenials are preserved as isolated elements with Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (Figure 26). For comparison the splenials of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012) and Pasquiaornis (RSM P2985.9) [65] were examined (Figure 27). The splenial of Parahesperornis has a slightly rounded lateral surface and a medial surface divided lengthwise by Meckel’s groove, which forms a slight shelf for the dentary. Above this shelf the splenial is very thin and appears to form a sheet over the ventral bladed portion of the dentary. This sheeted overlay of the splenial on the dentary is unusual in birds, but is also seen in Ichthyornis [61].

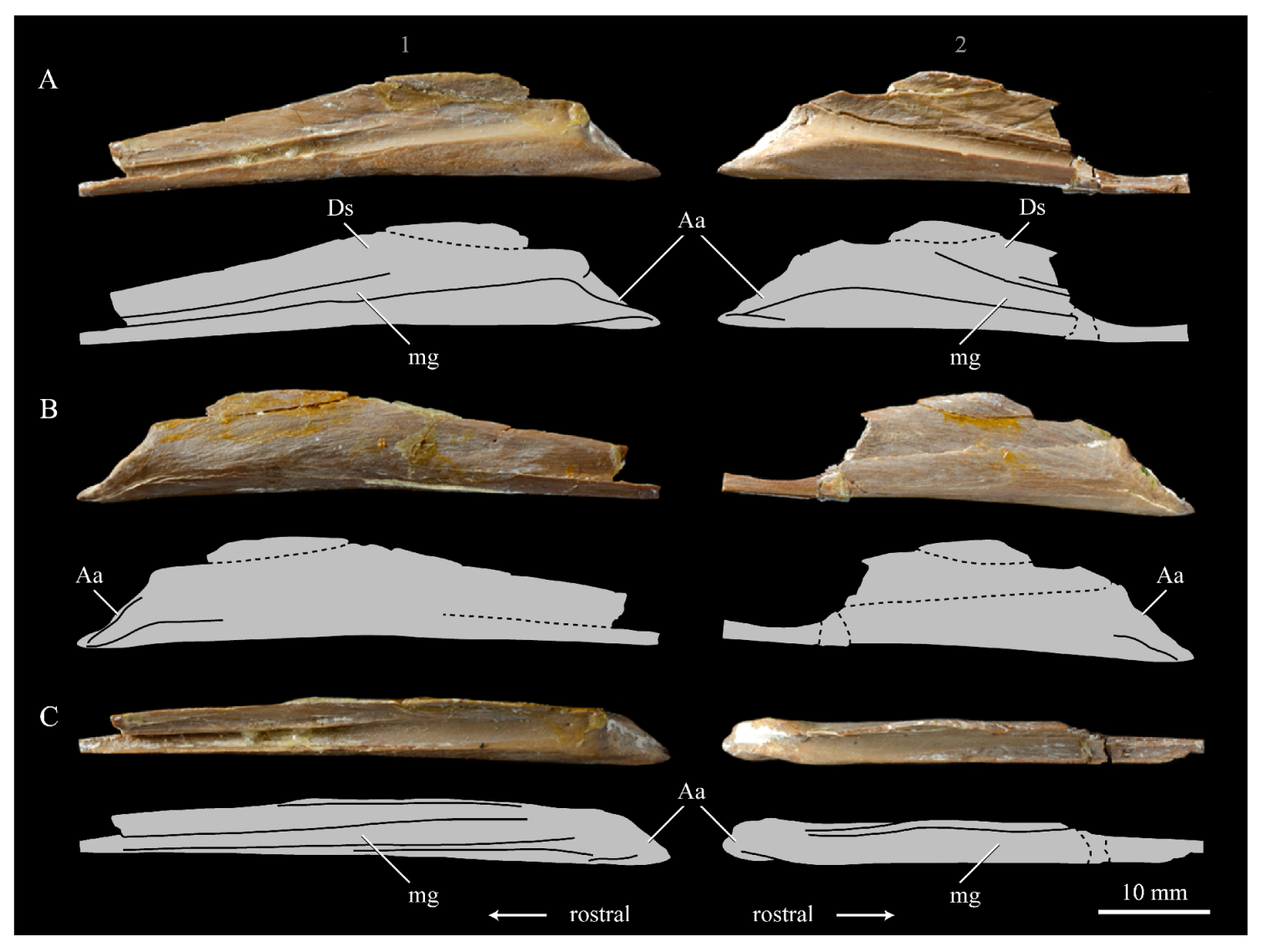

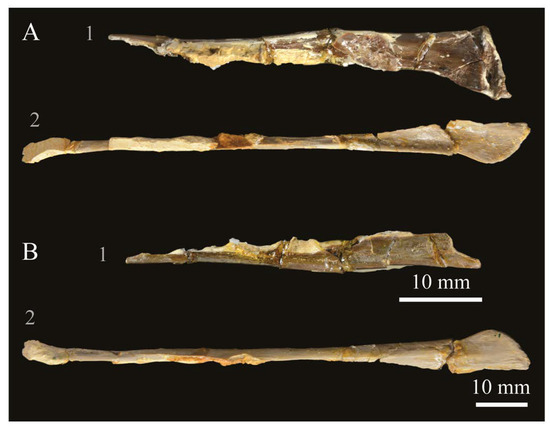

Figure 26.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, photographs (upper) and line drawings (lower) of the left (1) and right (2) splenials in lateral (A), medial (B), and dorsal (C) views. Abbreviations: Aa—articular surface for angular, Ds—sheet of bone overlaying dentary, mg—Meckel’s groove.

Figure 27.

Comparison of the splenials of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1) and Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2) in medial (A), lateral (B), and dorsal (C) views.

The caudal end of the splenial angles ventrally to form an articular surface for the angular. The splenial of Parahesperornis is very similar to that of Hesperornis, including in size, despite the overall larger size of the mandible of Hesperornis. In Parahesperornis the caudal end of the articular surface for the dentary angles more sharply ventrally at the caudal end than in Hesperornis, while in Pasquiaornis65 the transition is smooth and broad, more a curve than an angle.

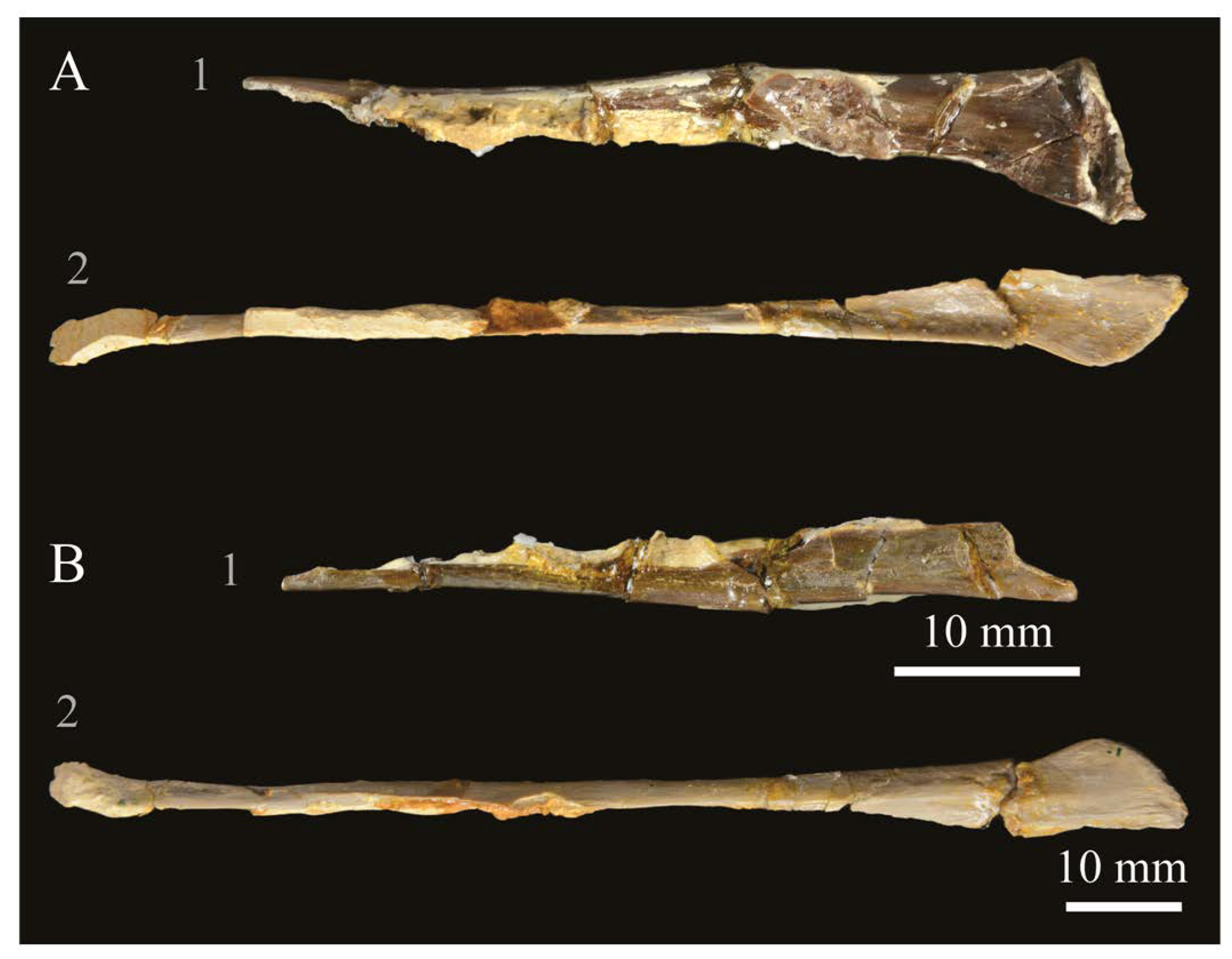

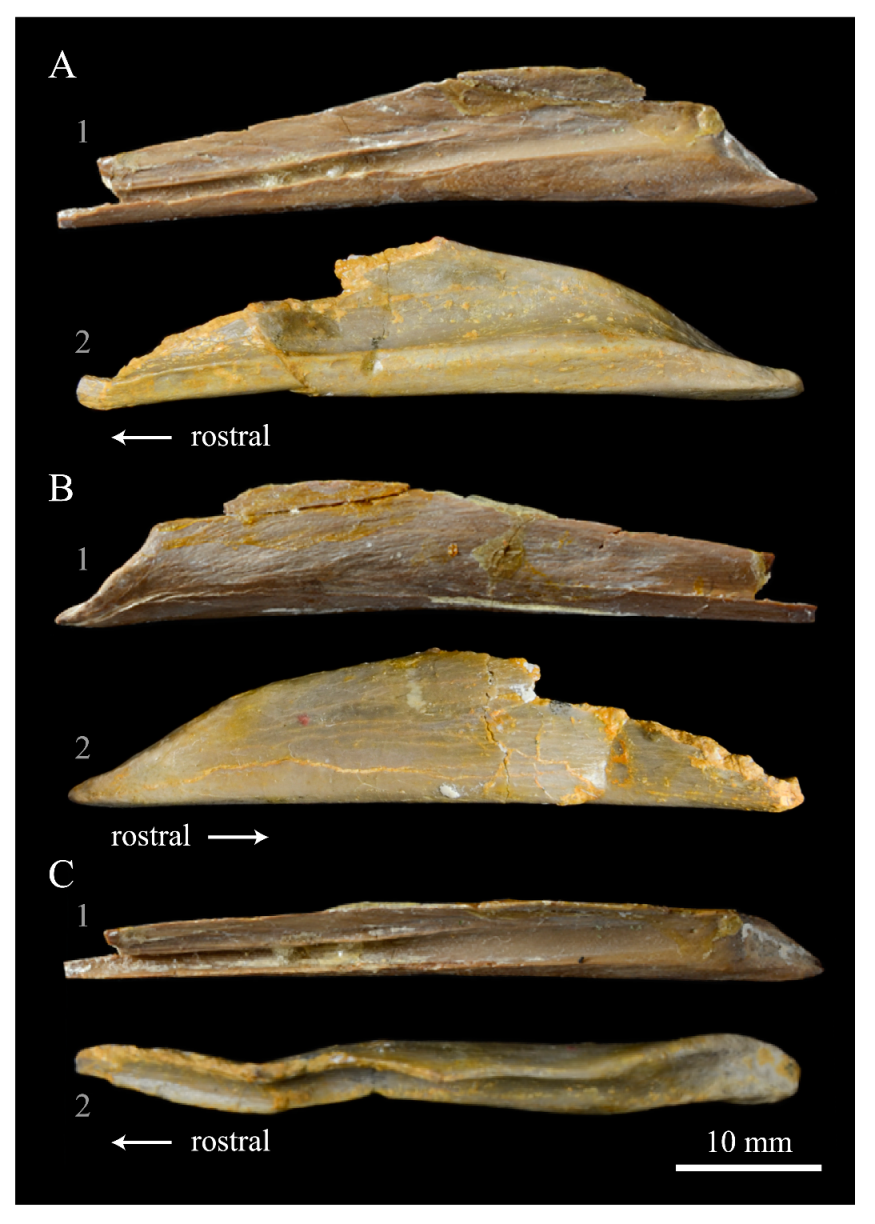

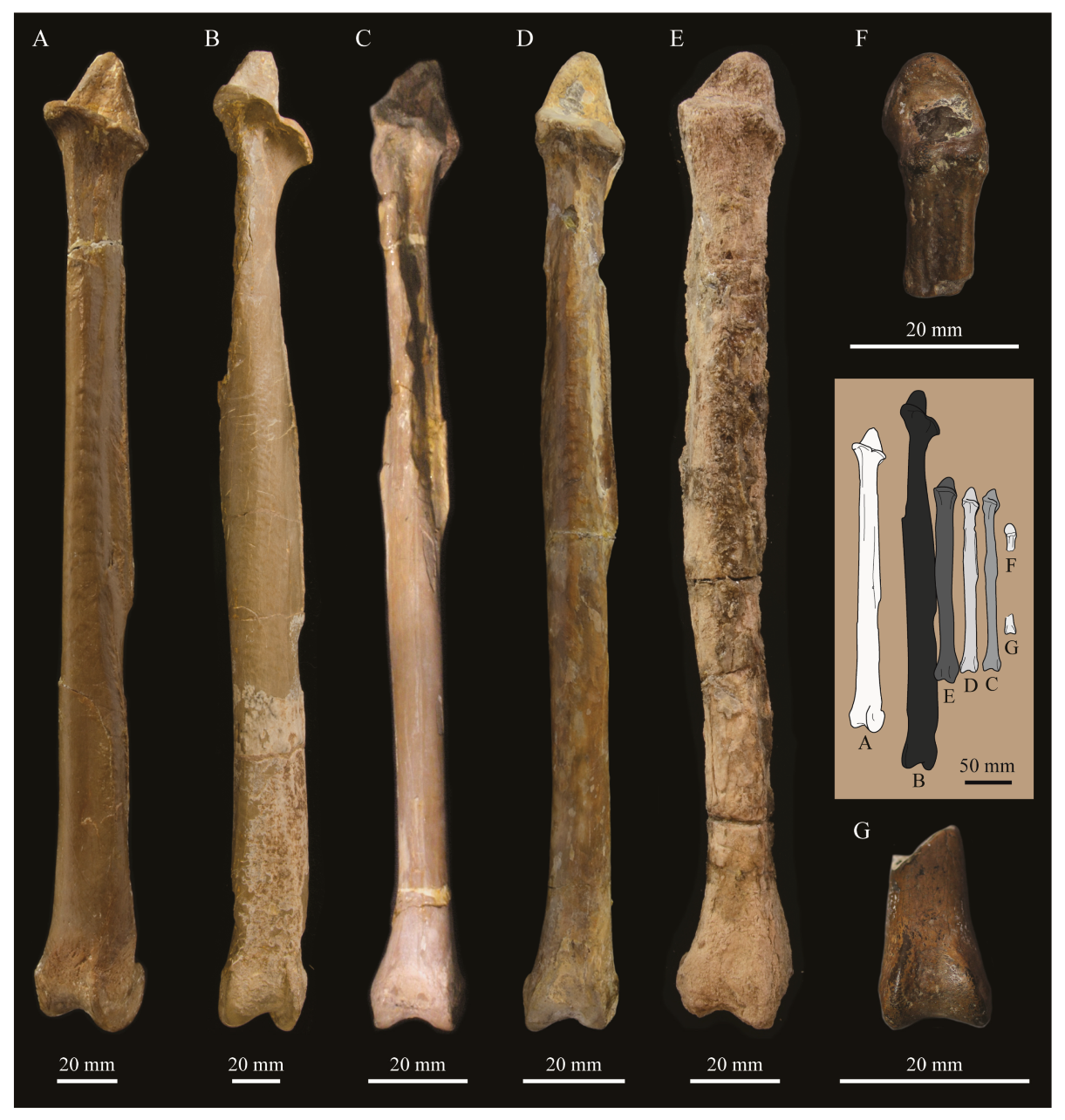

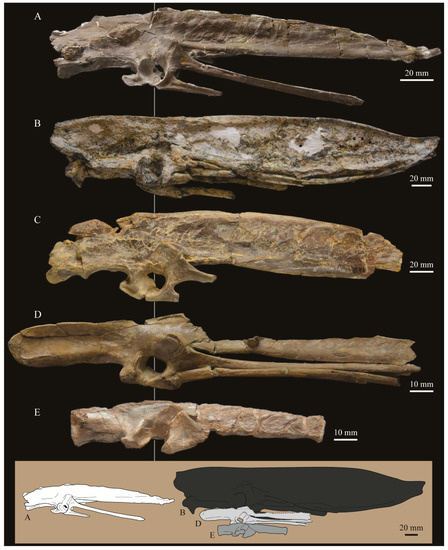

Dentaries. The dentaries of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 are poorly preserved, being incomplete and crushed (Figure 28). The right dentary preserves more of the length than the left, including the symphysis. For comparison, the dentaries of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012, YPM 1206) (Figure 29) and Pasquiaornis (RSM P 2831.60, RSM P 2985.10, RSM P 2988.11) [65] were examined, as well as a partial dentary assigned to Asiahesperornis (IZASK 4/KM 97, but see discussion below) [80]. All hesperornithiform dentaries show partial individual sockets for the teeth, opening into a dental groove running along the dorsal surface of the dentary [81] (a dental implantation similar to the ‘aulacodonty’ of non-avian reptiles [82]. While these partial sockets have been described as “faint” and insufficient to reduce the width of the dental groove [7], specimens that have broken open show the sockets to be clear divisions within the dentary, but not true sockets as in Ichthyornis (e.g., Hesperornis YPM 1206 and Pasquiaornis RSM P 2985.10 and RSMP P 2988.11). The dentary fragment assigned to Asiahesperornis (IZASK 4/KM 97) [80] shows clear alveoli for the teeth. As this is not the case among other hesperornithiforms, and the Asiahesperornis material consists entirely of unassociated elements, it is unlikely this specimen belongs to a hesperornithiform bird.

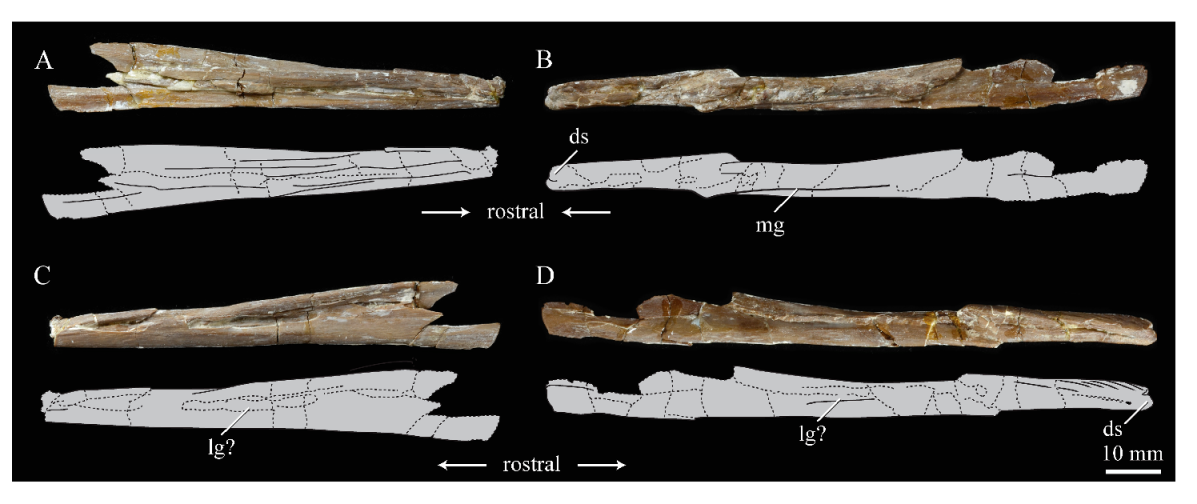

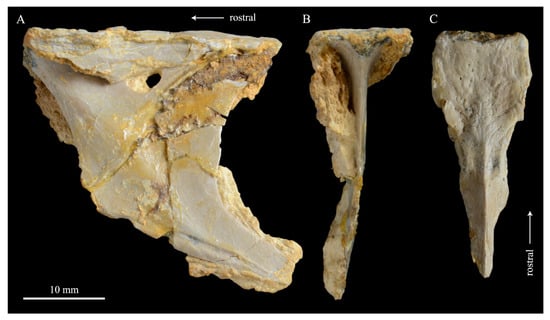

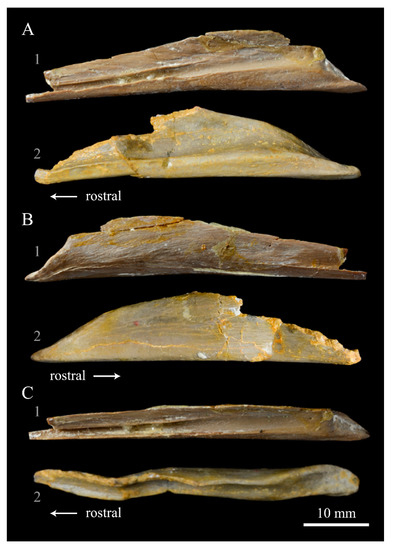

Figure 28.

Parahesperornis alexi KUVP 2287, photographs (upper) and line drawings (lower) of left (A,C) and right (B,D) dentaries in medial (A,B) and lateral (C,D) views. Abbreviations: ds—dentary symphysis, mg—medial groove, lg?—possible lateral groove.

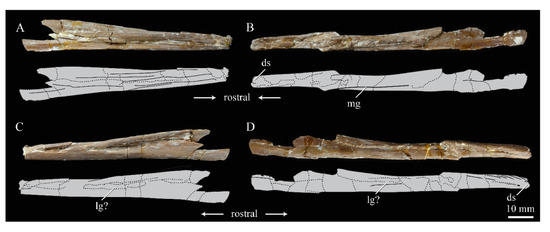

Figure 29.

Comparison of the dentaries of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (1) and Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (2) in medial (dorsomedial in Hesperornis due to crushing) (A) and lateral (B) views. Specimens are scaled to be similarly sized.

In Parahesperornis, the dental grooves appear similar to those of Hesperornis and expand at the caudal-most end, however the degree of crushing makes identification of more specific features difficult. The dentaries of Parahesperornis appear to preserve a longitudinal groove along the lateral face, as in Hesperornis and Pasquiaornis, however the degree of crushing makes this identification tentative. A pair of medial grooves have been reported in Pasquiaornis, and the right dentary of Parahesperornis appears to have a short groove present near the ventral margin. Hesperornis appears to have a single groove running down both the lateral and medial faces of the dentary.

The symphysis preserved on the right dentary consists of two small bulbous projections stacked vertically. This configuration is also present in Pasquiaornis (RSM P 2831.6). Some specimens of Hesperornis (i.e., KUVP 71012) do not show this, having instead a smooth symphysis that tapers to a point (Figure 29), while others do appear to have the rounded projections (YPM 1206).

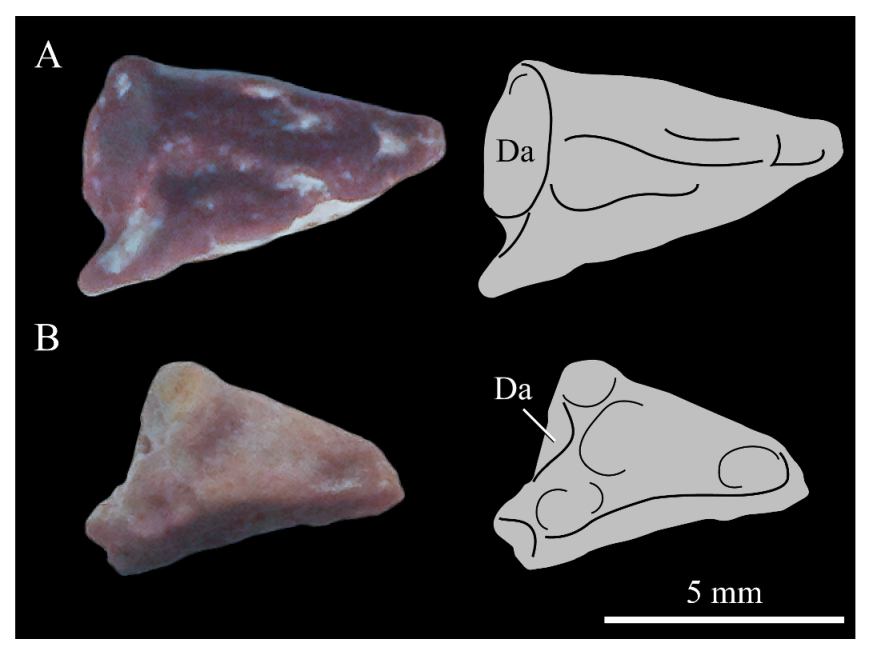

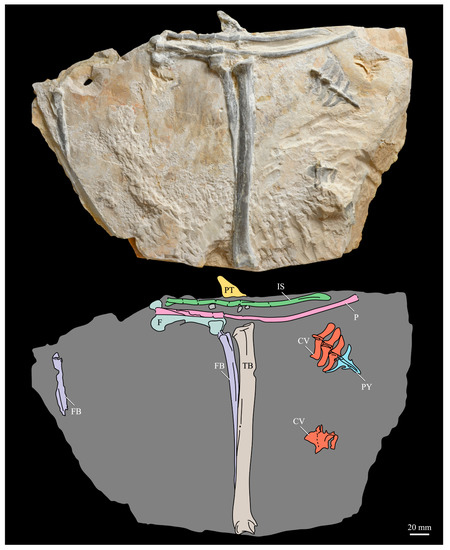

Predentaries. Martin first reported the existence of a predentary bone in ornithuromorphs when he described those of hesperornithids [83]. Within the Hesperornithiformes to date, this bone has only been reported for a single specimen of Hesperornis (KUVP 71012) and Parahesperornis (KUVP 2287) [73] (Figure 30). The predentary is known in other Mesozoic ornithuromorphs, including Ichthyornis, Yanornis, Yixianornis, Hongshanornis, and Jianchangornis [84,85].

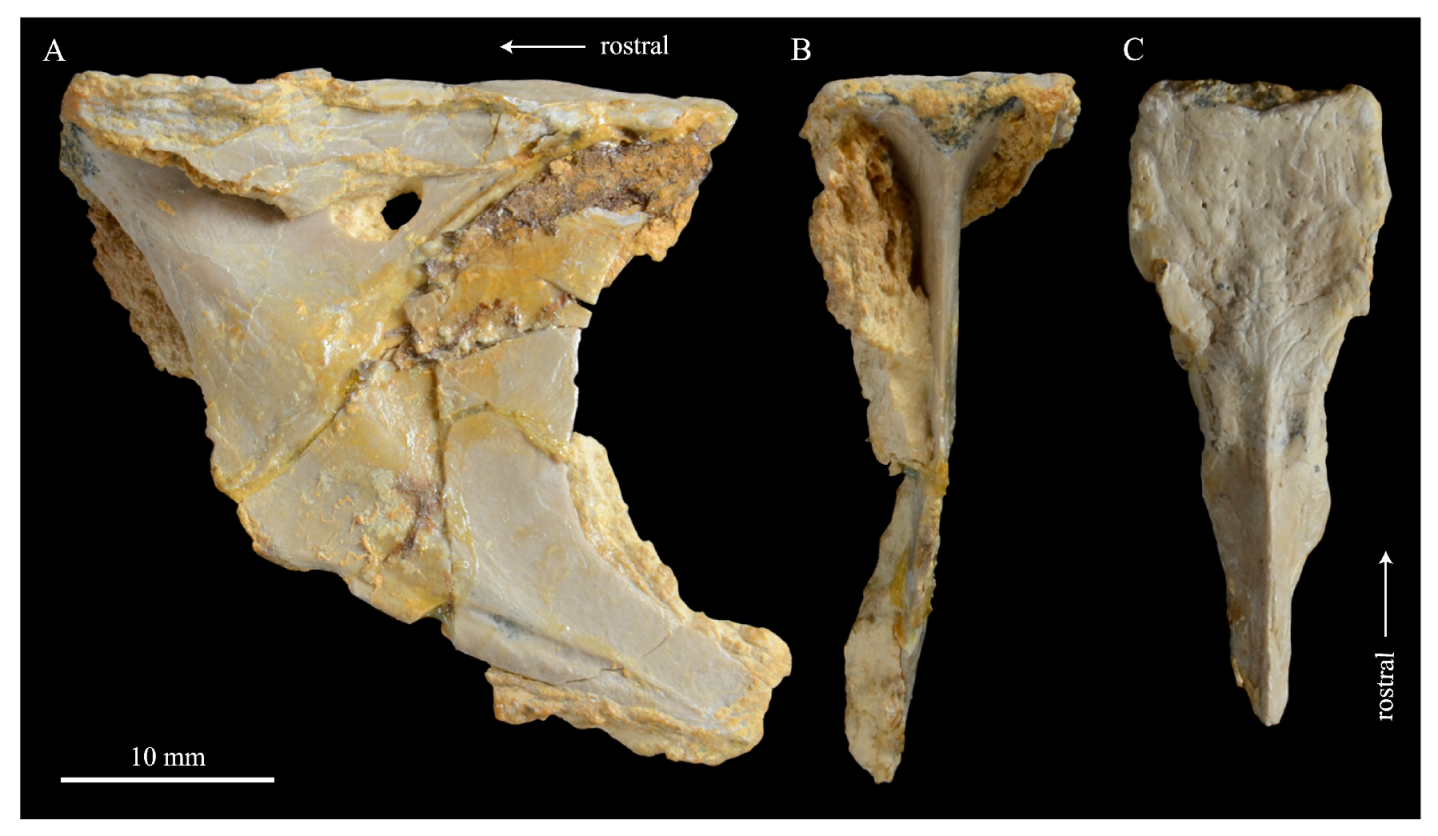

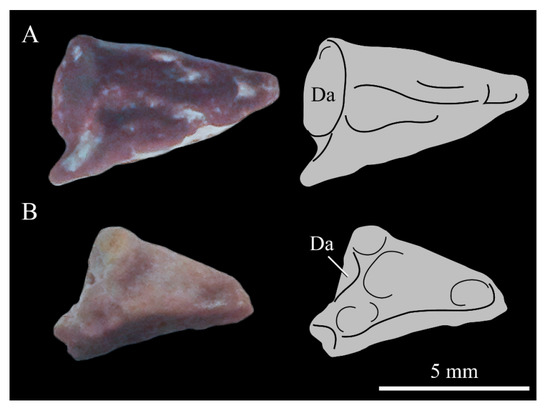

Figure 30.

Predentaries of Parahesperornis KUVP 2287 (A) and Hesperornis KUVP 71012 (B) in right lateral view. Abbreviation: Da—dentary articular surface.

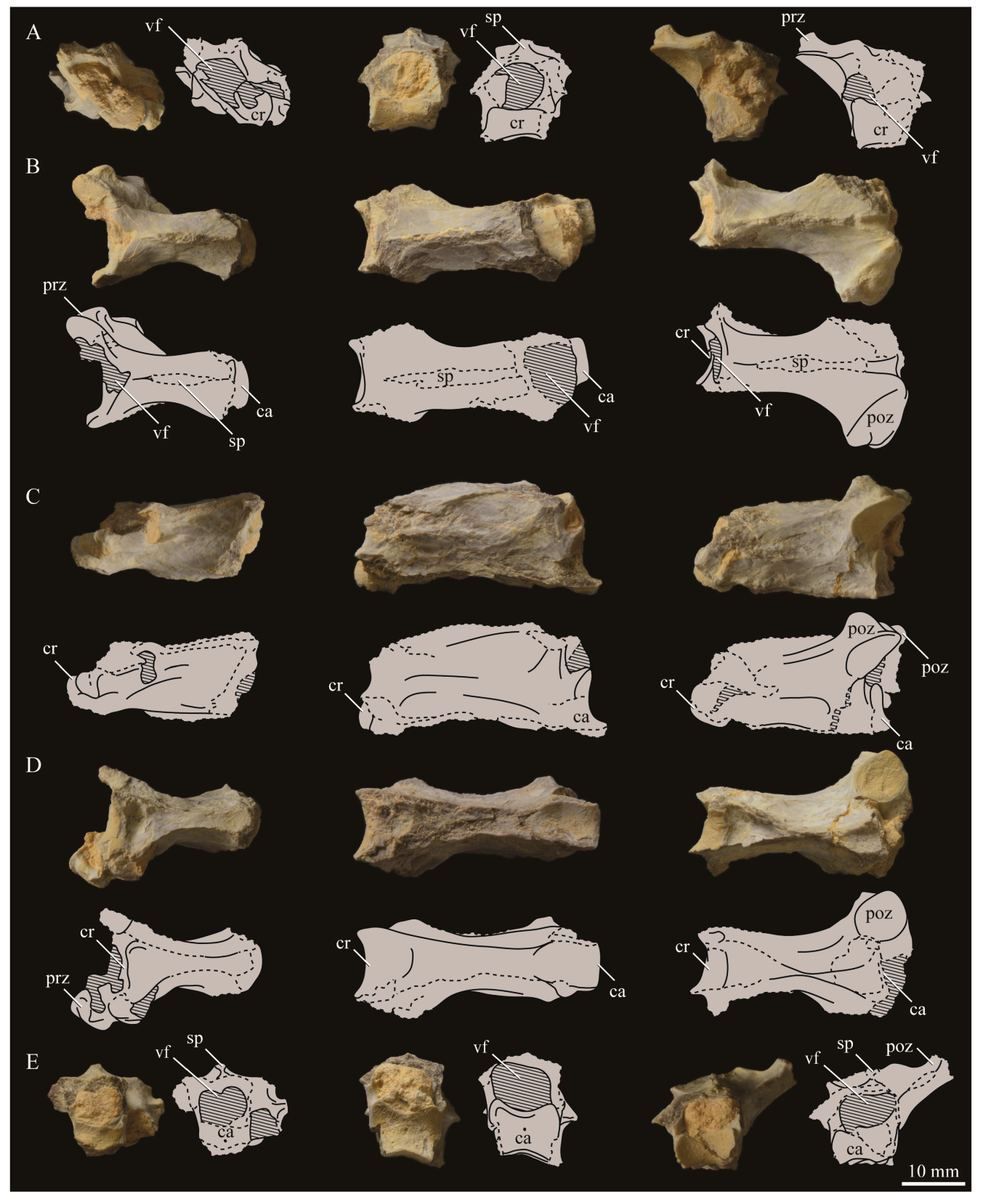

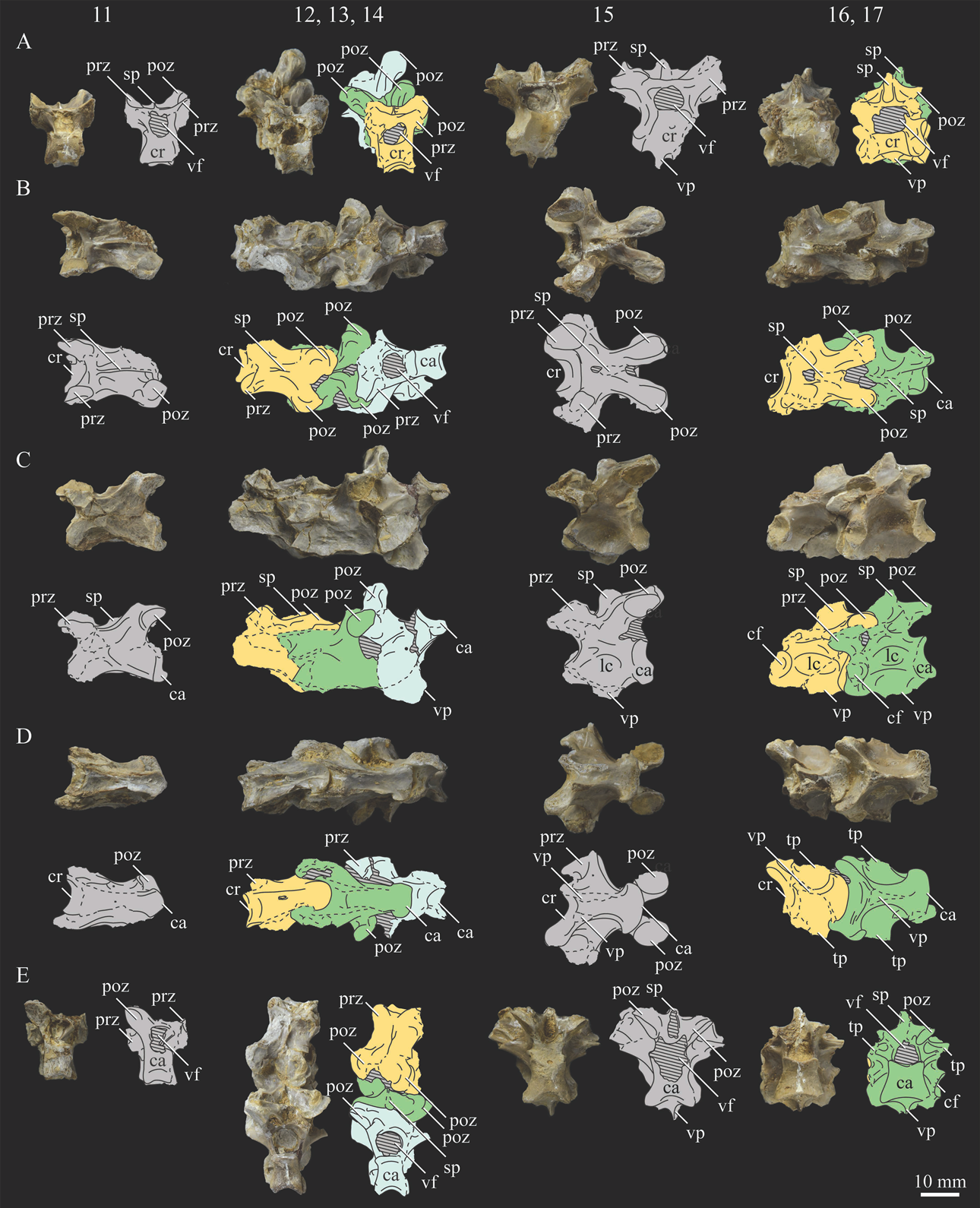

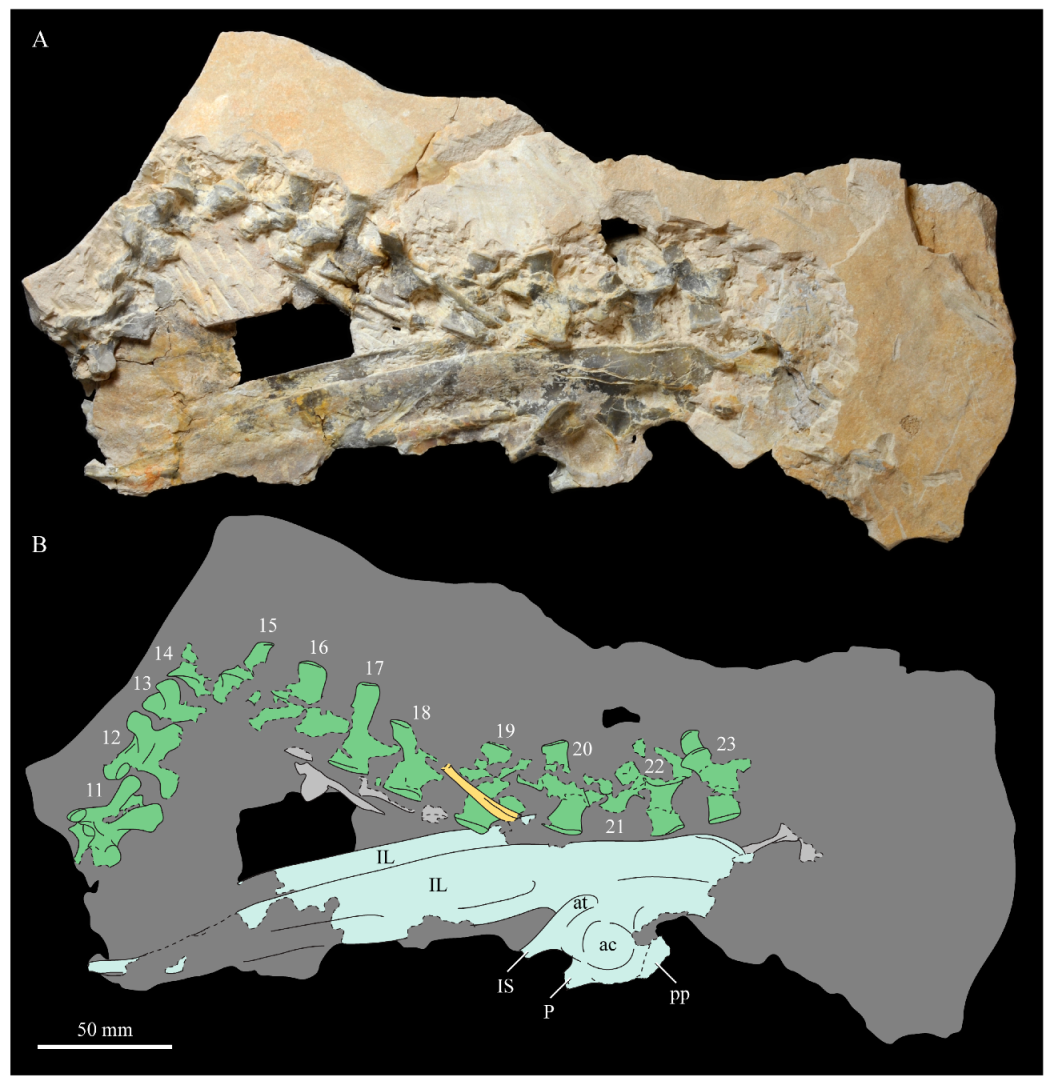

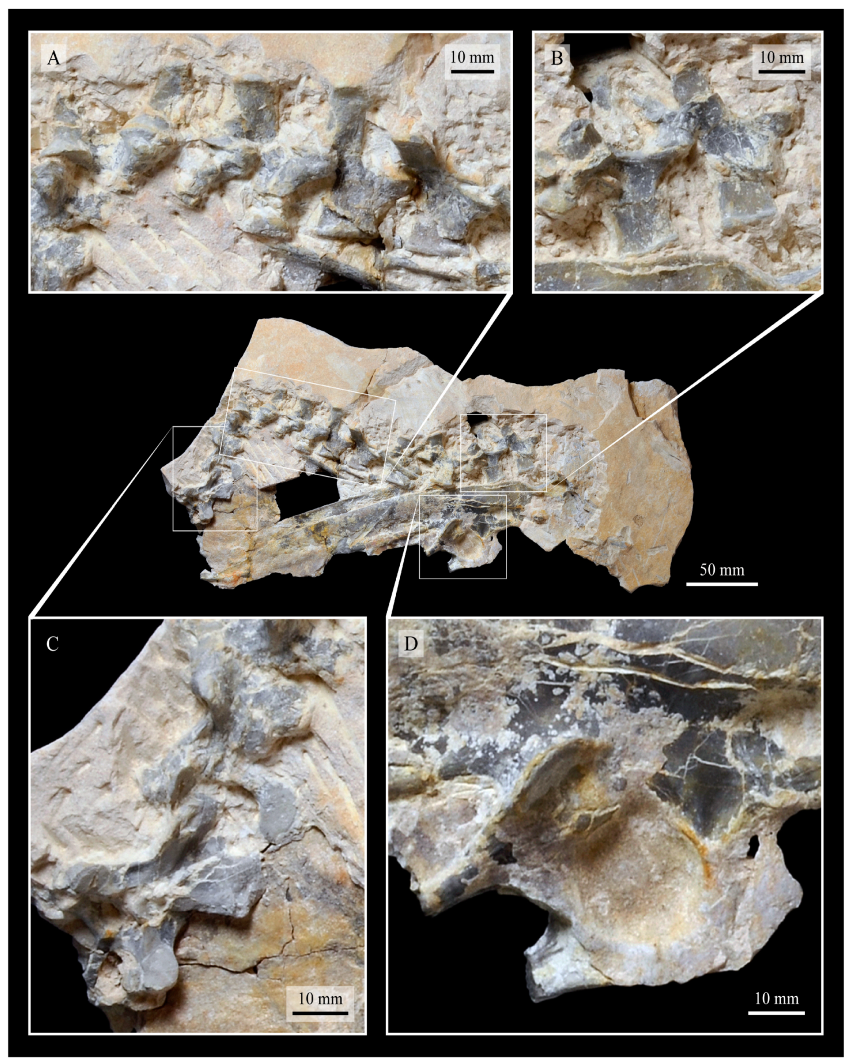

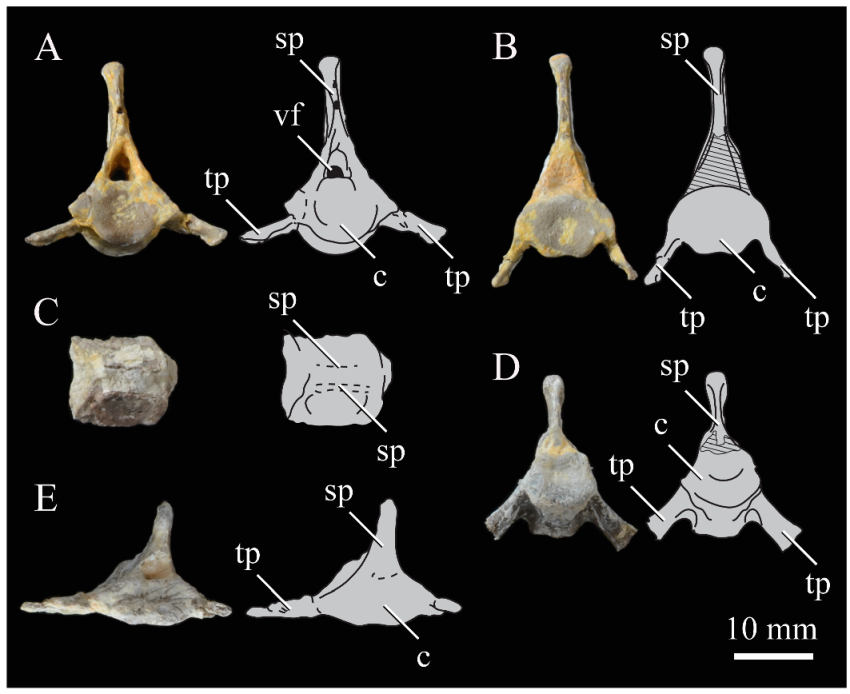

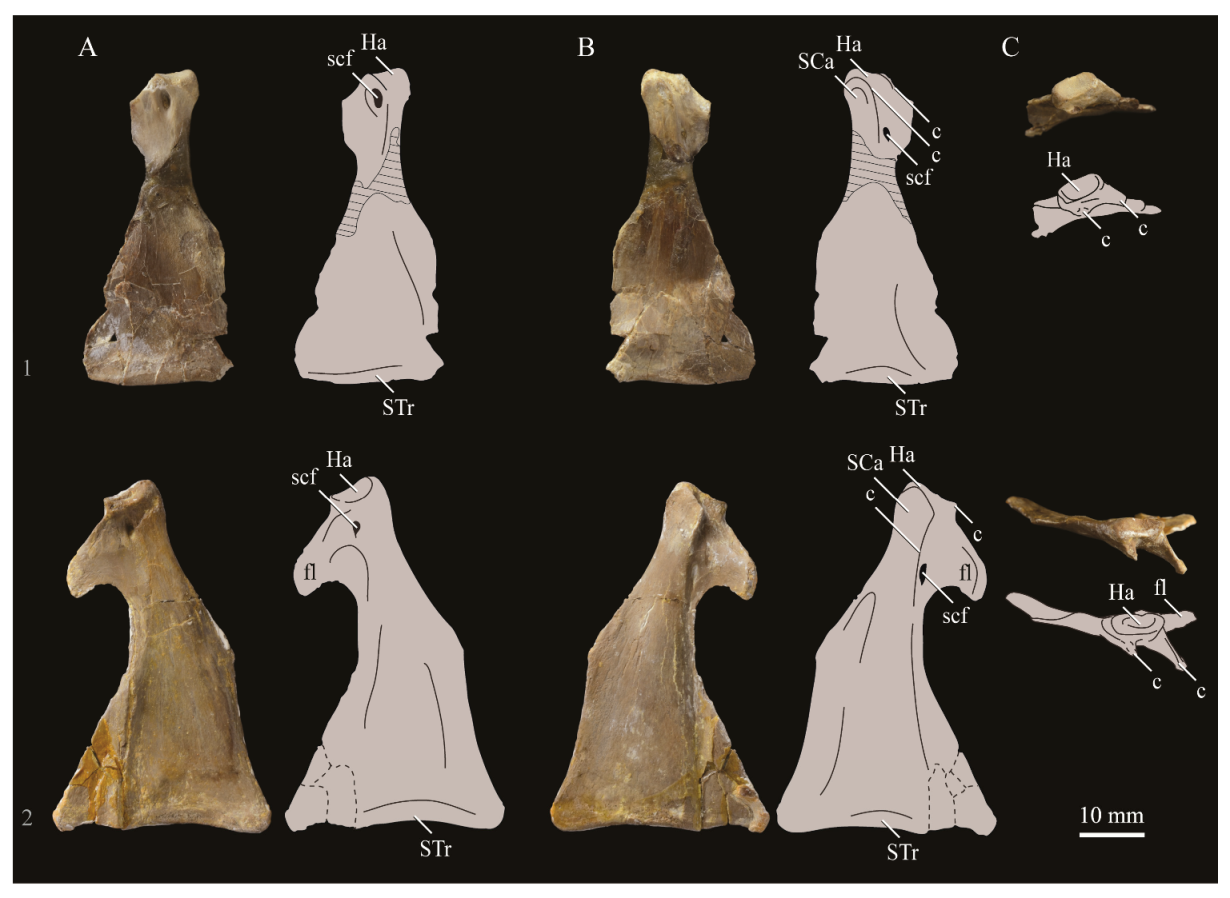

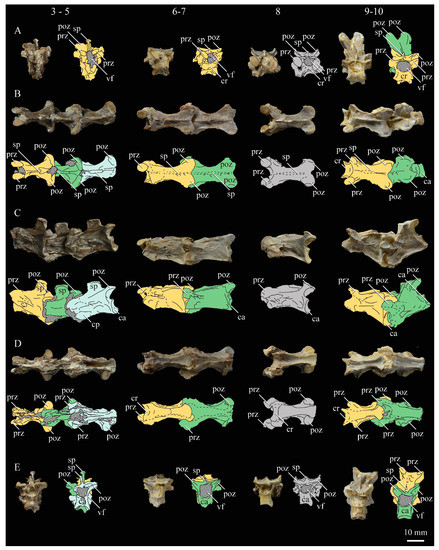

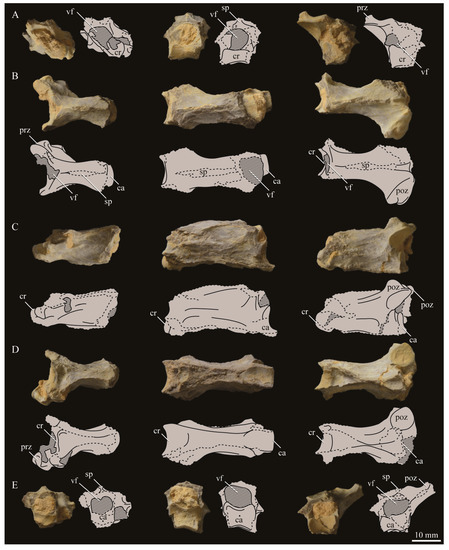

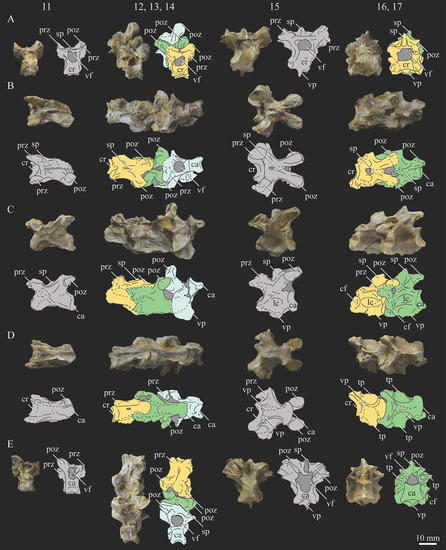

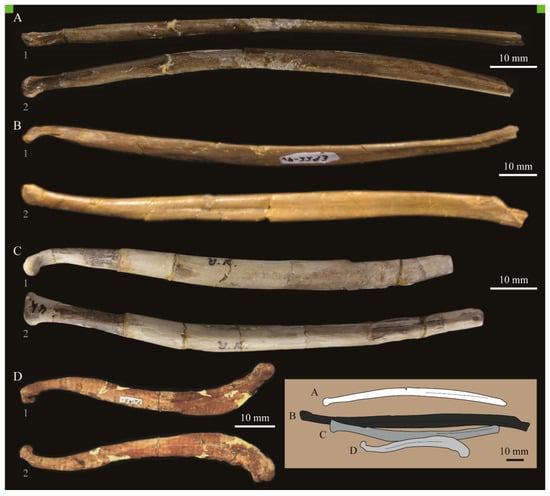

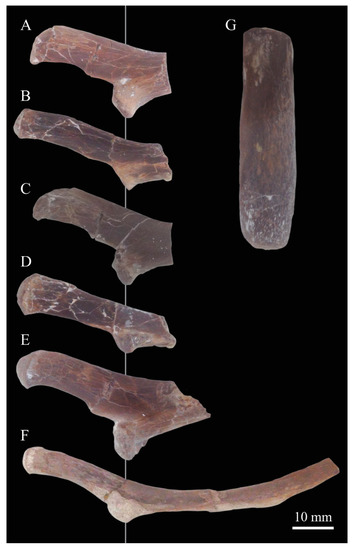

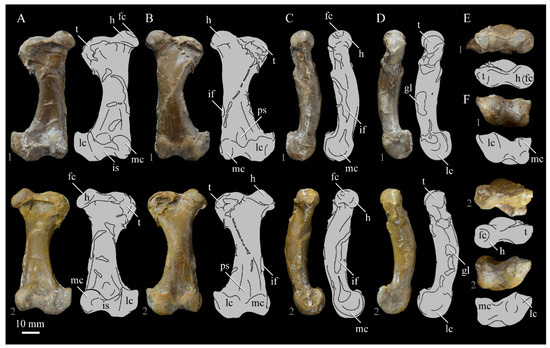

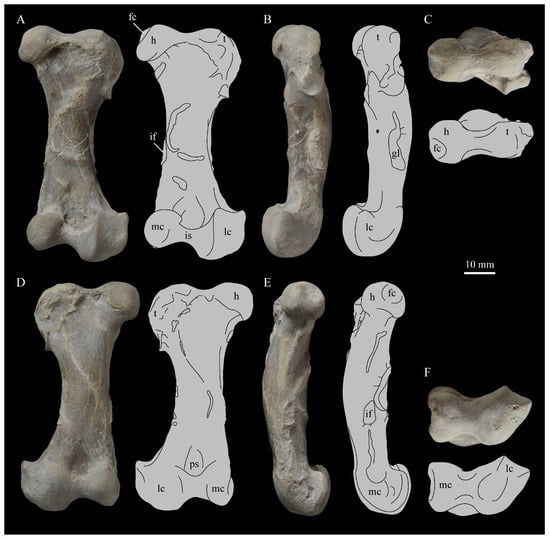

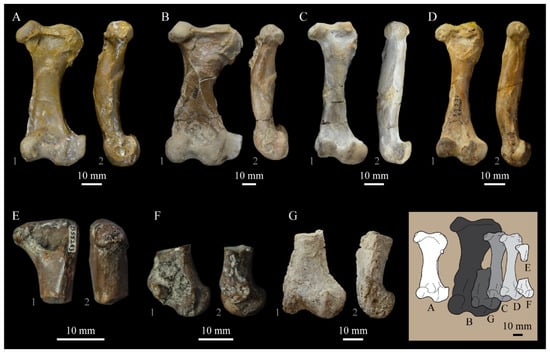

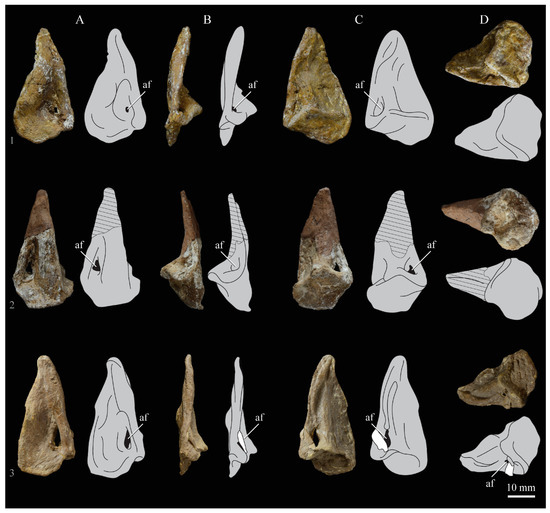

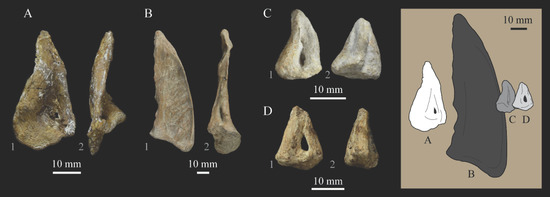

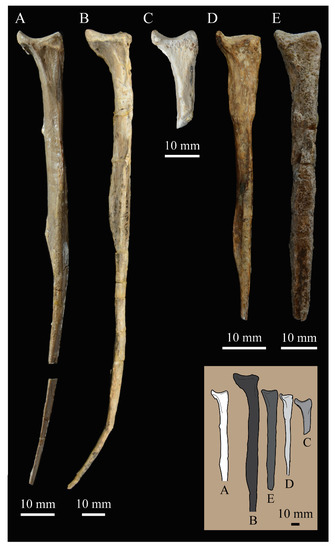

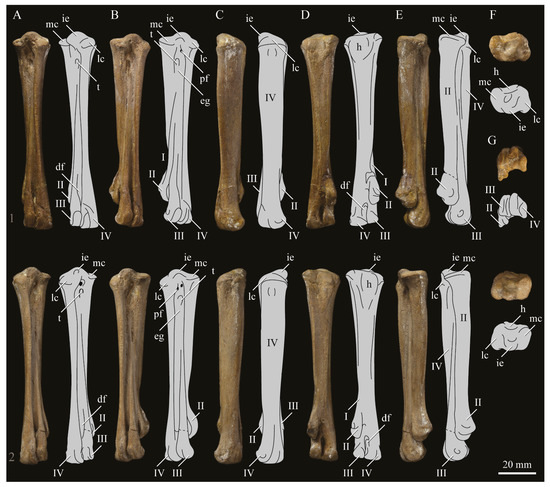

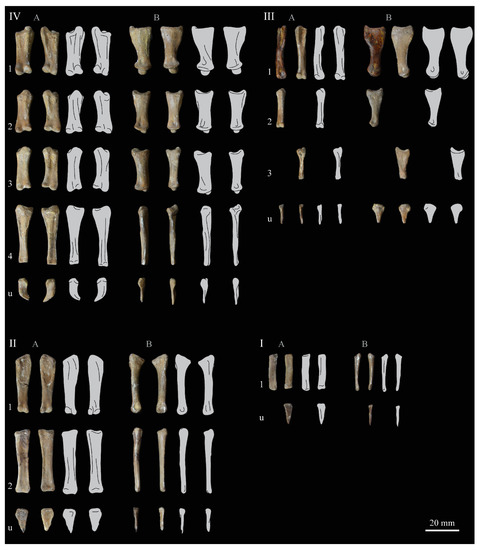

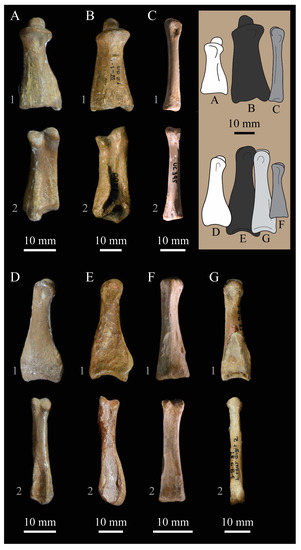

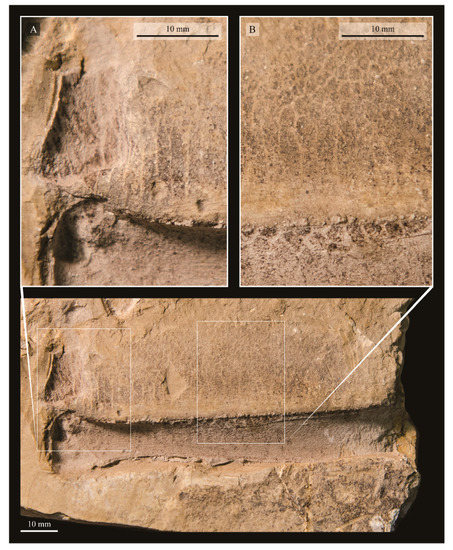

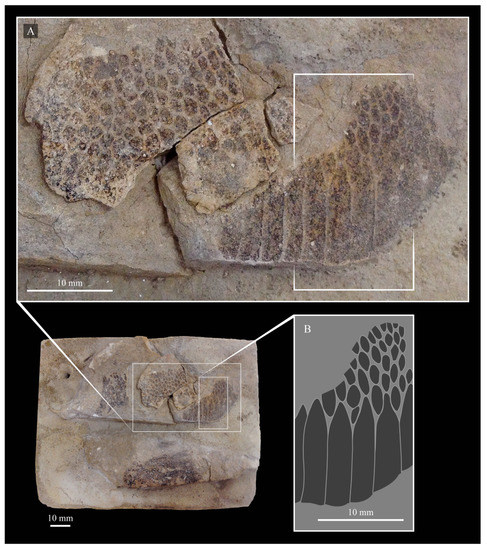

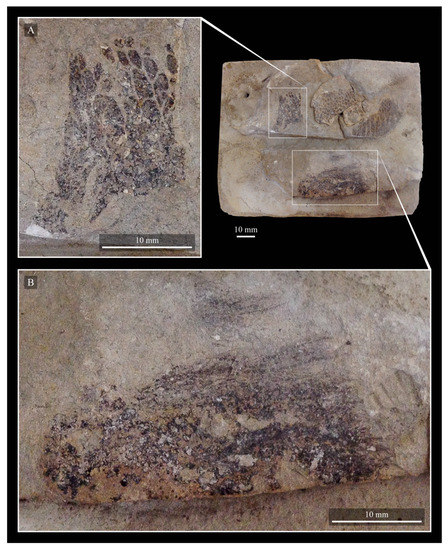

The predentary of Parahesperornis possesses a pair of small facets on the caudal face, the right of which is deformed and flattened. In Hesperornis KUVP 71012, a single facet appears to be present; however, it is possible that weathering of the element could have obscured the division of the facets. The predentary of Parahesperornis is more elongate than that of Hesperornis. While the predentary of Hesperornis is certainly more weathered than that of Parahesperornis, this is not enough to account fully for the size discrepancy. Recent work has hypothesized a unique mandibular kinesis in ornithuromorphs that possess a predentary, with a synovial joint involving ventral flexion of the dentaries and translation and compression of the predentary on the dentaries [85].