Diagnostic Analytics Powered by IoT and Machine Learning for the Fault Evaluation of a Heavy-Industry Gearbox

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Experimental Setup

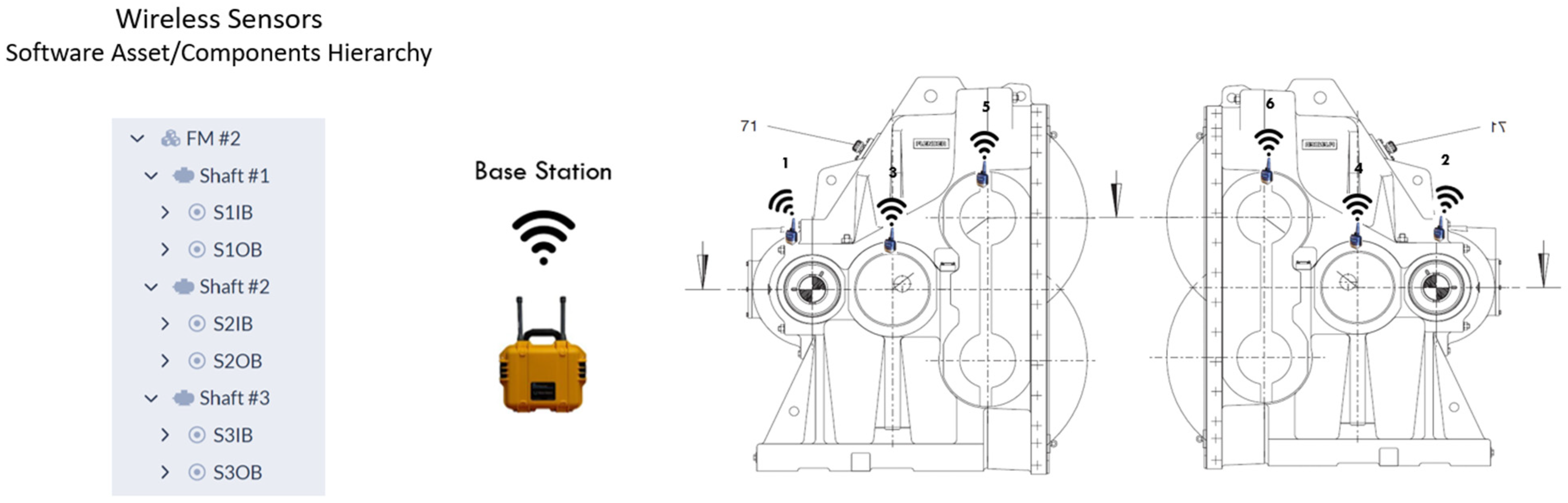

2.1.1. Vibration Measurement Configuration

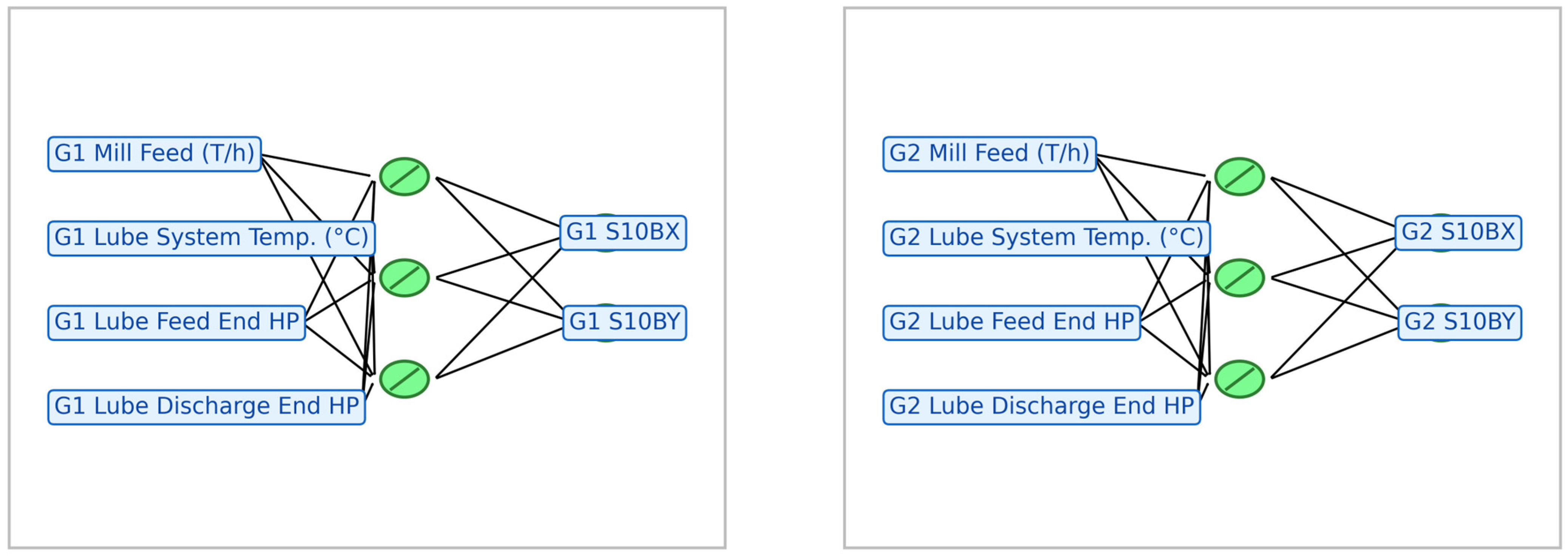

2.1.2. Process and Operating Variables

2.1.3. Data Synchronization and Dataset Construction

- Outlier and invalid-signal handling: removal of records associated with clearly non-physical readings and/or inadequate sensor signals (e.g., dropouts, spurious spikes, or corrupted measurements).

- Operating-regime filtering: Exclusion of startup and shutdown transient periods, which were not within the scope of this study. Only stable/steady-state operation was retained for modeling.

- Time-based equalization/consolidation: within steady-state operation, measurements were consolidated to provide a consistent representation of comparable time intervals and to reduce redundancy from highly correlated records.

2.1.4. Experimental Setup Summary

2.2. IoT-Based Vibration Monitoring System

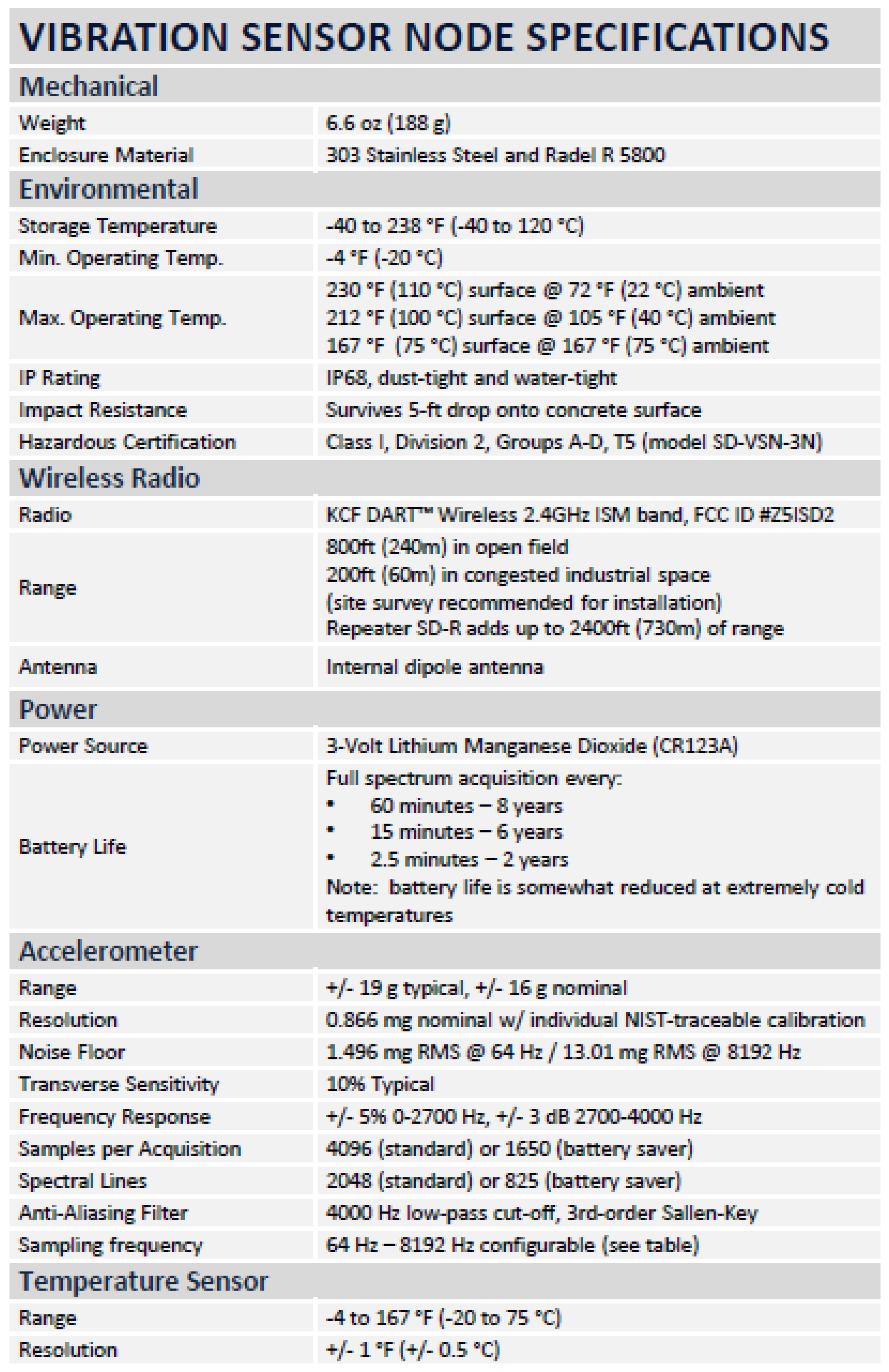

- Wireless Vibration Sensors: high-rate piezoelectric accelerometers SD-VSN-3 (see specifications in Appendix A) with 100 mV/g sensitivity and an effective frequency bandwidth of approximately 5 kHz were installed on the bearing housings associated with the three high-speed shafts by using magnetic bases to capture real-time vibration data.

- Data Acquisition and Transmission: sensors report overall RMS vibration derived from the accelerometer signal, together with lubrication temperature, and transmit data to a central cloud-based platform for further analysis.

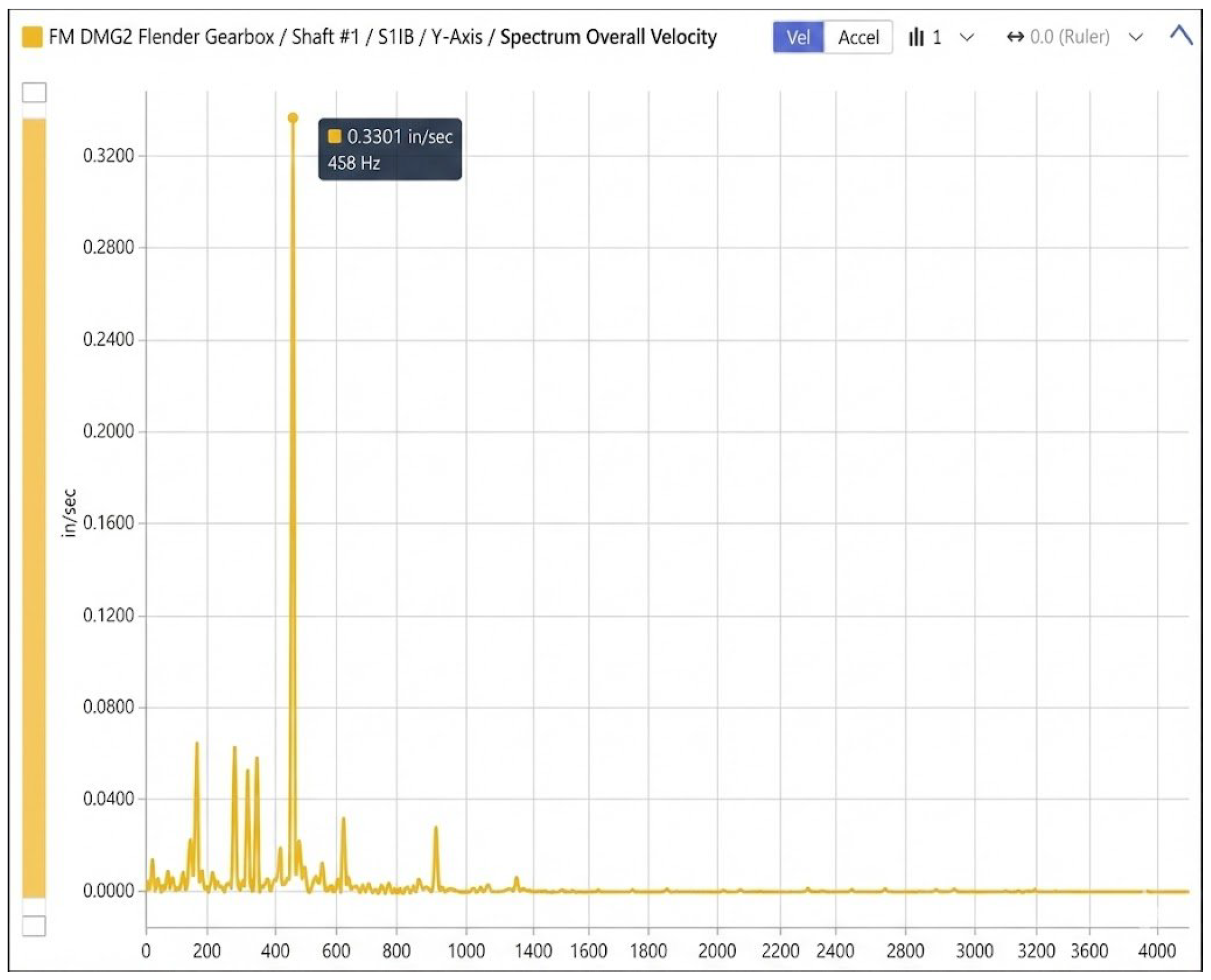

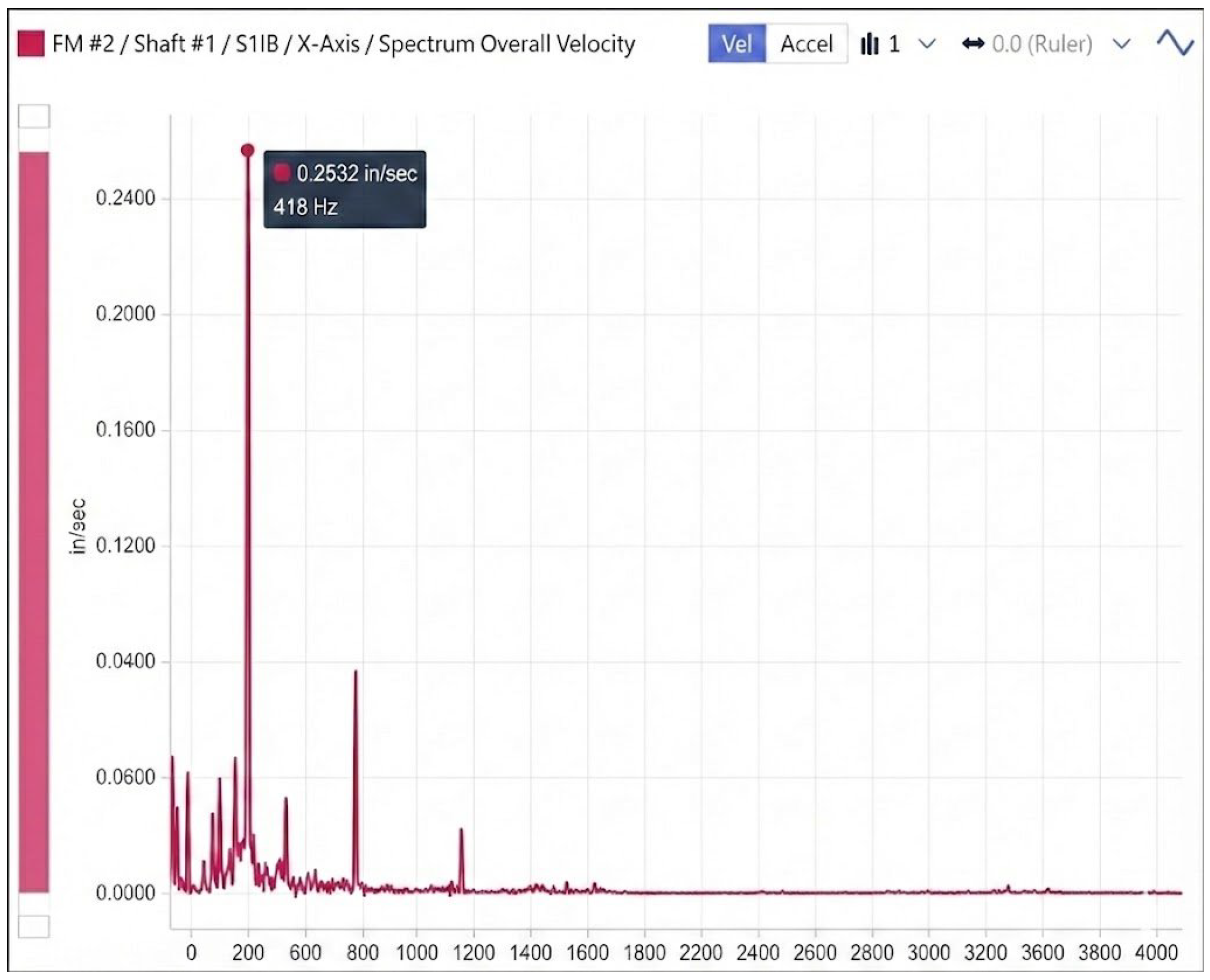

- Software Asset Hierarchy: includes features for trend visualization, spectral analysis, and failure frequency tracking.

- Lowpass filtering to remove high-frequency sensor noise.

- RMS computation per 1 s window to align vibration and process signals.

- Z-score normalization of continuous features.

- Outlier handling by winsorization at the 1st and 99th percentiles and removal of unsynchronized records.

- Feature enrichment with time lags and derivatives (lags of 1–60 s) to capture transient behavior.

- Inputs: vibration RMS X and Y axes (in/s RMS), oil temperature °C, lubrication discharge pressure bar, lubrication feed-end pressure bar, mill feed T/h, motor power kW, and regime flag (stopped, startup, and steady).

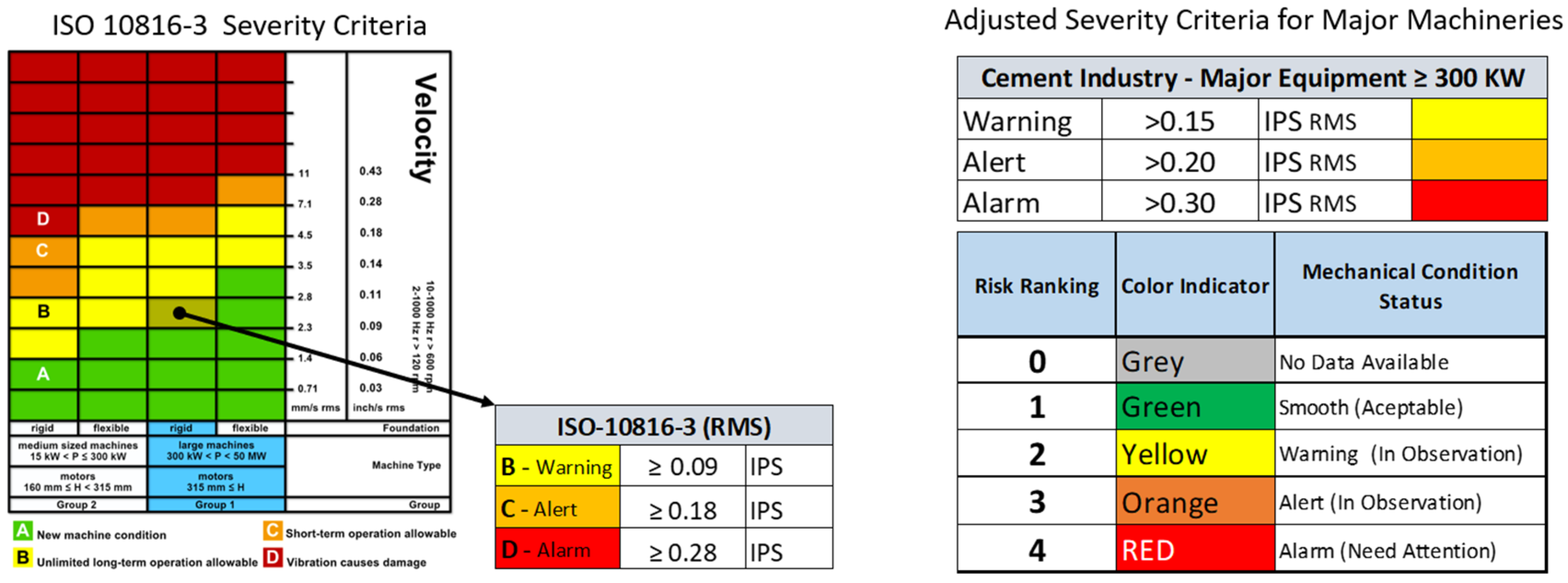

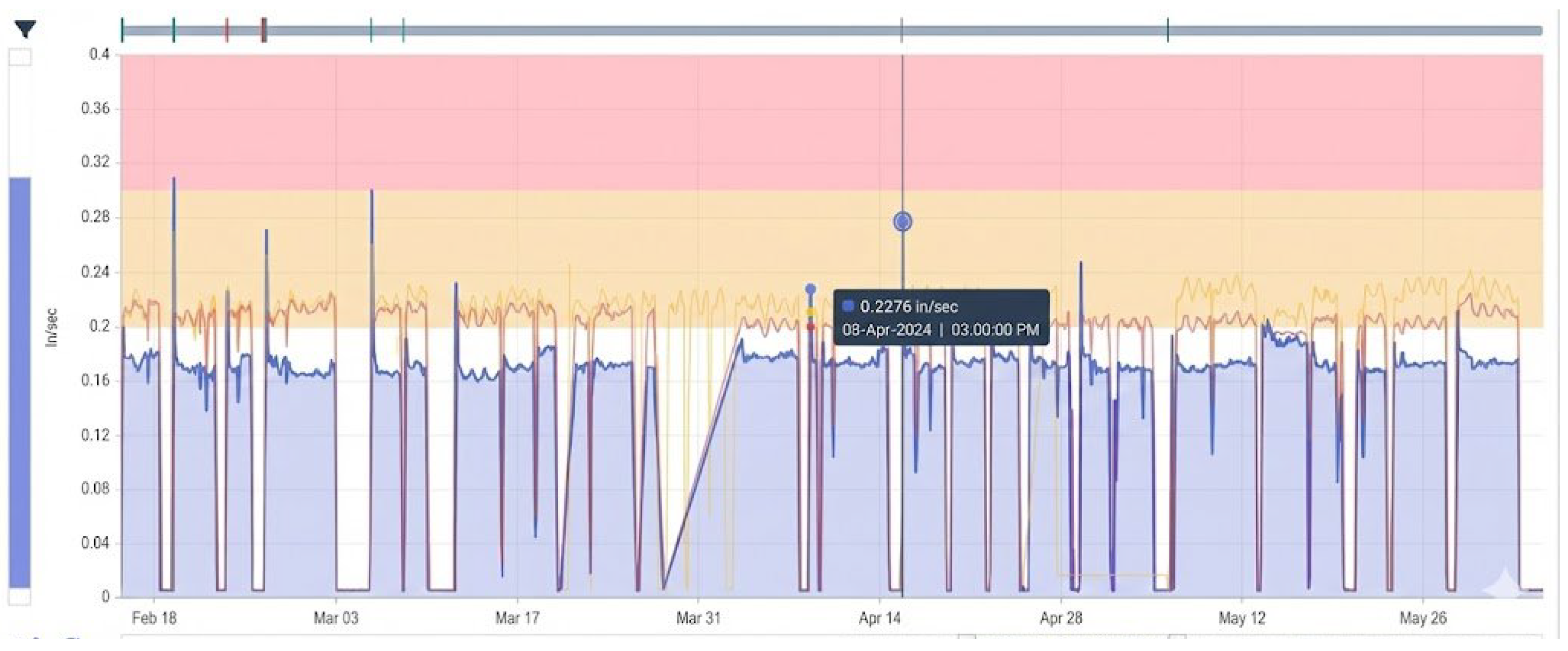

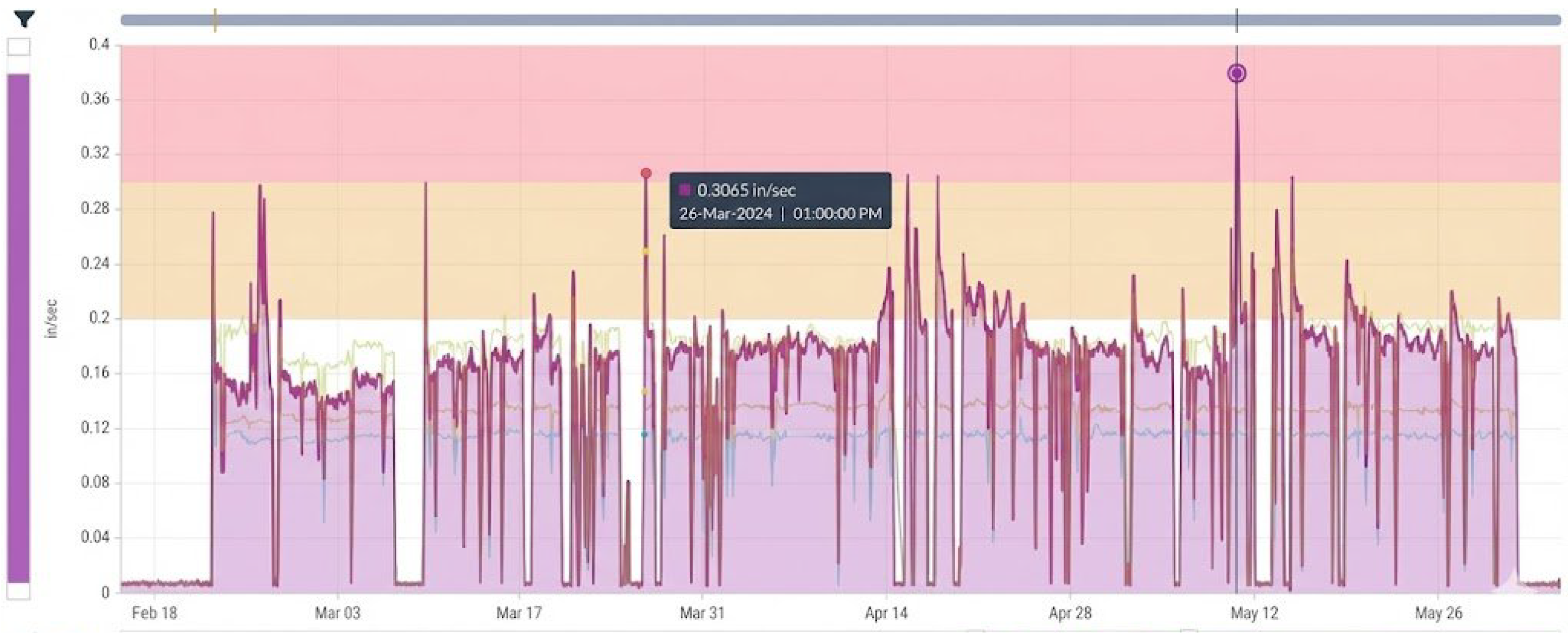

2.3. Severity Criteria

- Warning: >0.15 IPS RMS

- Alert: >0.20 IPS RMS

- Alarm: >0.30 IPS RMS

2.4. Modeling Approach and Selection

- Boosted multilayer feedforward neural network boosted (MFNN): activation tanh; final architecture with three hidden layers with 64, 32, and 16 neurons; L2 regularization λ = 1 × 10−4; early stopping on validation loss; boosting with learning rate of 0.05; and inputs normalized.

- Boosted trees (BT): maximum depth, 4; n estimators, 100; learning rate, 0.1; and standard subsample and regularization from the Model Screening defaults.

- K-nearest neighbors (kNN): k swept 1 to 10; Euclidean distance on normalized features; and k selected by validation performance.

2.4.1. Boosted Multilayer Feedforward Neural Network (MFNN)

- Input Layer: it is the starting layer of the network that has a weight associated with the signals.

- Hidden Layer: this layer lies after the input layer and contains multiple neurons that perform all computations and pass the result to the output unit.

- Output Layer: it is a layer that contains output units or neurons and receives processed data from the hidden layer; if there are further hidden layers connected to it, then it passes the weighted unit to the connected hidden layer for further processing to obtain the desired result.

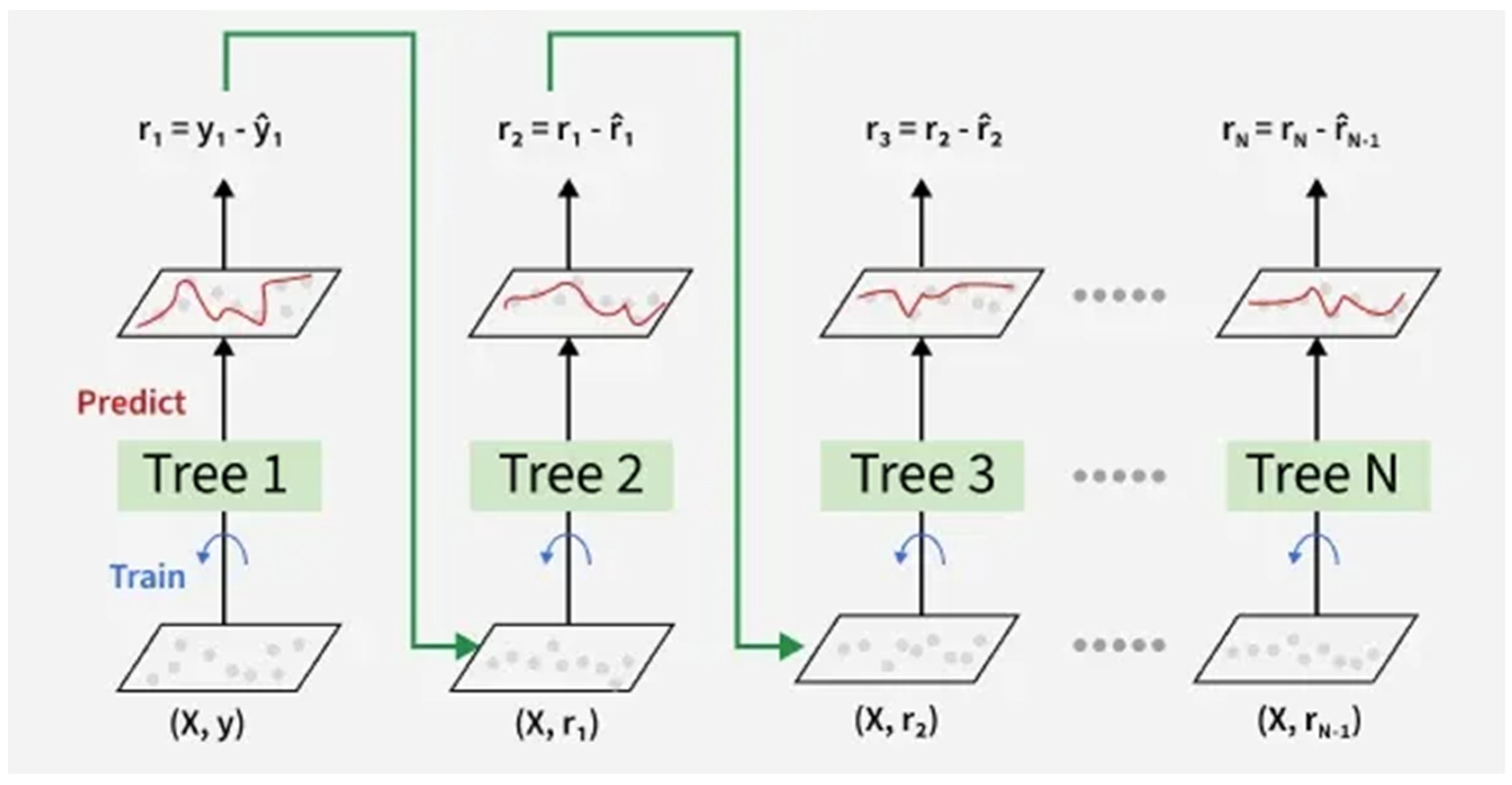

2.4.2. Boosted Trees (BTs)

- Rm is the region of the feature space corresponding to the m-th leaf;

- cm is the average (or median) of the target values in leaf m during training;

- 1{x ∈ Rm} is an indicator function that equals 1 if the input x falls into region Rm and 0 otherwise.

- Tree options: the number of levels (tree depth) is 4.

- Boost options: the number of models is 100, the learning rate is 0.1, and the alpha is 0.95.

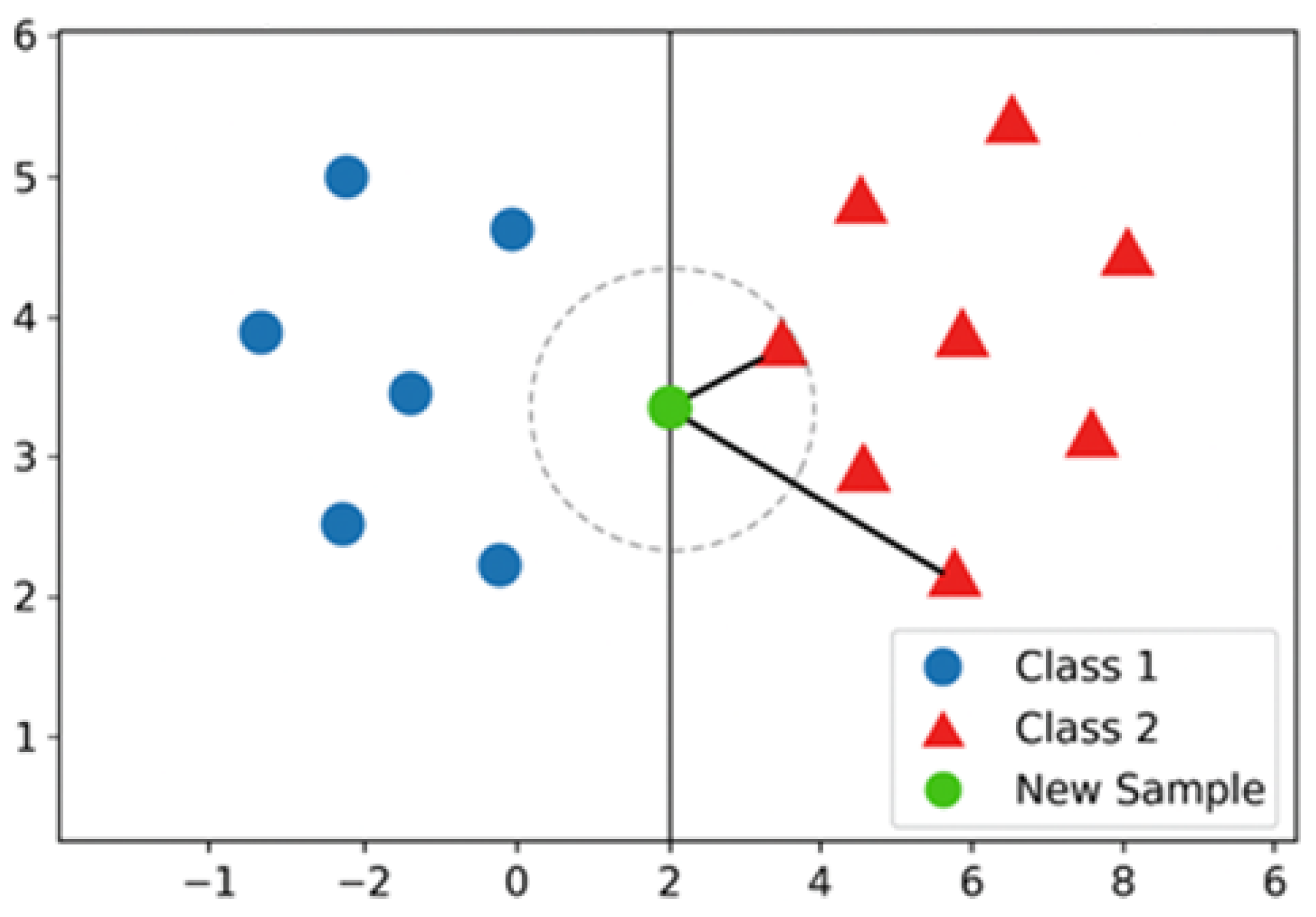

2.4.3. K-Nearest Neighbors

- Euclidean distance: This is the most commonly used distance measure, and it is limited to real-valued vectors. Using Equation (4), it measures a straight line between the query point and the other point being measured.

- Manhattan distance: this is also another popular distance metric, which measures the absolute value between two points, as it can be seen in Equation (5).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Vibration Trends and Failure Patterns

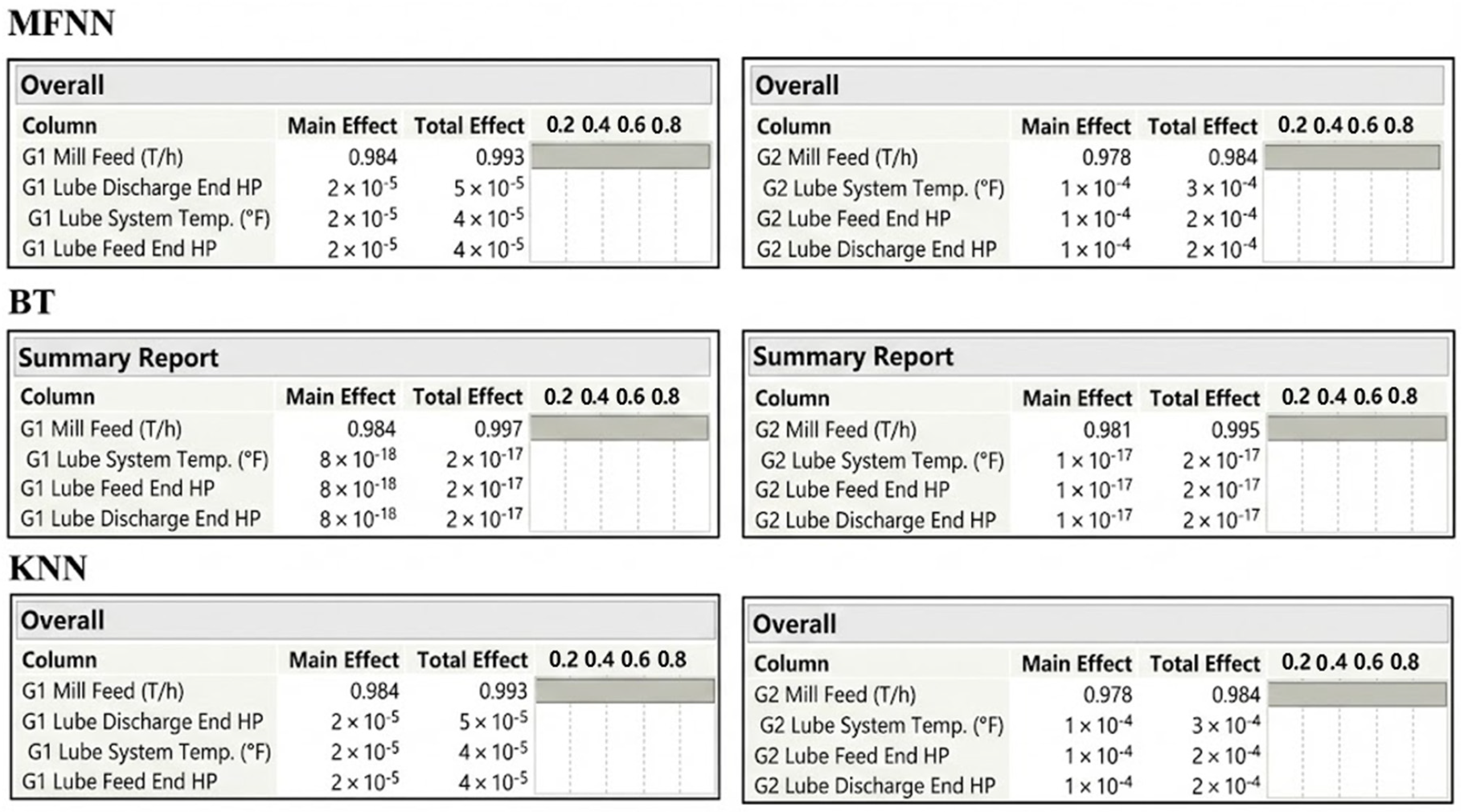

3.2. Results Interpretation Based on the Evaluated Models (Neural Boosted, Boosted Tree, and k-Nearest Neighbors)

- k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN): k sweeps yielded competitive training fit in some targets, but consistent holdback validation was not available in these outputs. kNN did not surpass the Neural model on validated comparisons.

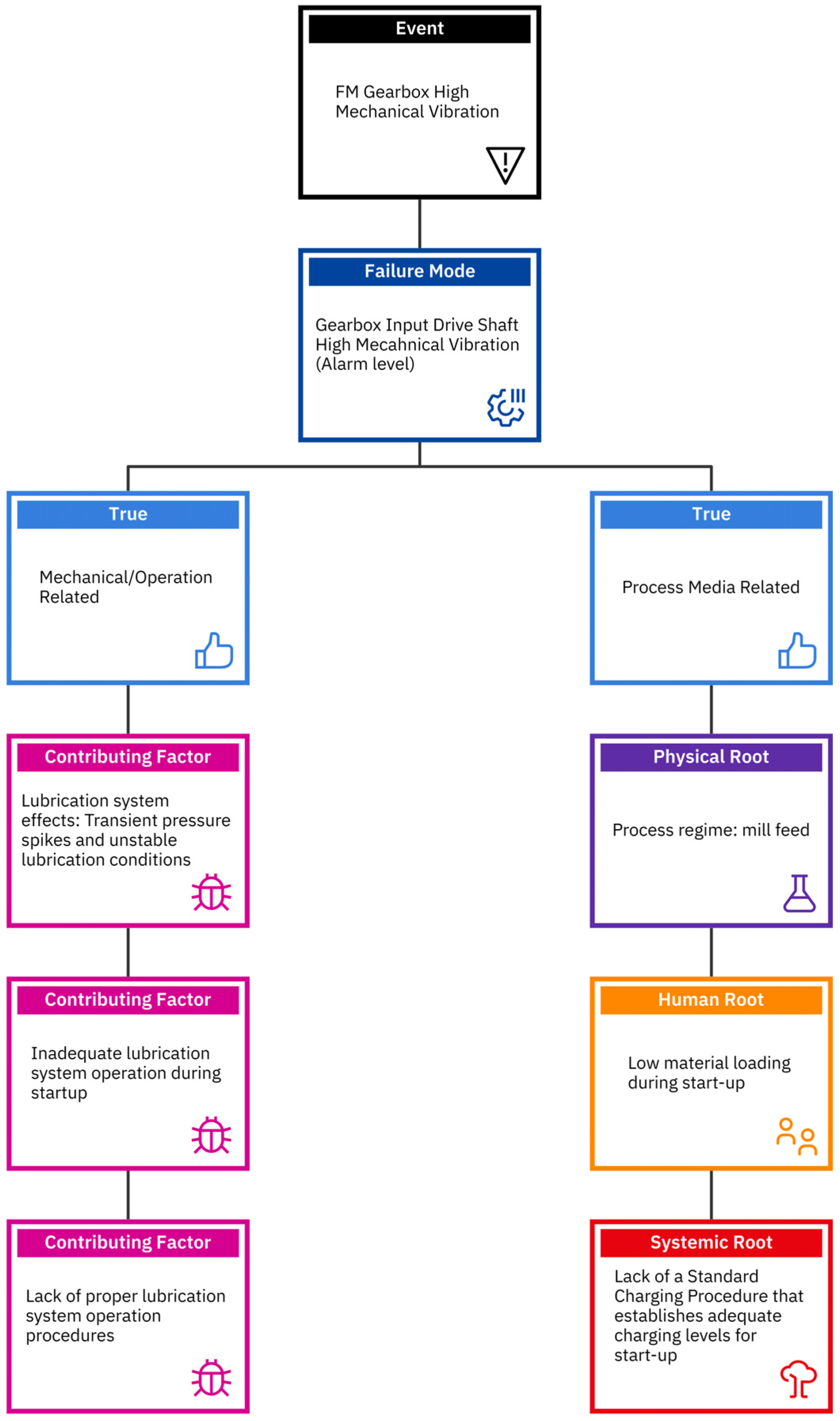

3.3. Root Cause Failure Analysis (RCFA)

- Process regime (primary driver): The most consistent driver of gearbox vibration is the mill feed (T/h). Neural variable-importance results show mill feed with the largest Main and Total Effects across gearboxes (G1 and G2) and axes (S1OBX and S1OBY). Practically, the highest risk windows occur at very low or near-zero feed during startups and ramp-ups. Under these conditions, small disturbances can trigger disproportionate vibration responses. This finding contradicts the initial intuition that heavy load would be the dominant cause.

- Lubrication system effects (secondary but material): Transient pressure spikes and unstable lubrication conditions can amplify vibration, particularly when coincident with low-feed operation. Mechanistically, unstable film formation and short-term changes in oil flow/pressure can increase tooth contact variability and excite mesh dynamics. While the absolute effect sizes of lube variables are smaller than feed, their interaction with feed is meaningful (Total Effect > Main Effect), indicating non-additive behavior.

- Mechanical contributors (context): Classic mechanical factors such as alignment, backlash, bearing condition, and gear mesh quality remain credible contributors. However, within the scope of this dataset, their influence appears largely mediated by the operating regime (feed) and lubrication stability. This does not rule them out; rather, it suggests they are less frequently the initiating cause of the observed excursions.

- Startup and ramp strategy: establish minimum feed set-points before releasing to normal operation; apply controlled ramps to avoid low-feed dwell times; and monitor for rapid feed oscillations.

- Lubrication stability: enforce pressure stability targets, verify pump performance curves at the expected operating points, and maintain oil quality and temperature within tighter bands.

- Monitoring and governance: add operator prompts and interlocks for low-feed startups; pair feed control with real-time lube pressure checks to suppress excursions; and document exceptions and review them weekly.

4. Conclusions

- Feed governance: implement minimum feed thresholds before transition to normal operation; define ramp-rate guardrails; and flag prolonged low-feed dwell.

- Lubrication control: set narrower pressure and temperature bands for startup and ramp; verify pump health and control loop tuning; and add alarms for fast pressure transients.

- Alarming and human-in-the-loop: convert the model’s signals into clear operator prompts and priority alerts during startups and high-risk regimes.

- Integrate axial measurements for certain fault mechanisms such as misalignment, axial loading or mounting issues to complete the diagnostic assessment.

- Model robustness and scope: add k-fold cross-validation and out-of-time validation; expand the feature set (torque, shaft load, oil temperature at critical points, and gear mesh indicators); and evaluate multi-target models for X/Y axes simultaneously.

- Sensing and data quality: consider higher-frequency accelerometers at mesh and bearing locations; ensure synchronized timestamps among process and vibration channels; and standardize data preprocessing and health checks.

- Real-time deployment: implement streaming model scoring with simple rules for RASE- and residual-based anomaly flags; publish alerts to the control room with recommended operator actions.

- Process optimization studies: design small, controlled ramp experiments to quantify how specific feed profiles and lubrication set-points affect vibration; update standard operating procedures and training materials accordingly.

- Mechanical verification: when the model flags persistent anomalies outside of known process regimes, it triggers targeted inspections (alignment, backlash, and bearing condition) to confirm or dismiss mechanical root causes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Igba, J.; Alemzadeh, K.; Durugbo, C.; Henningsen, K. Performance Assessment of Wind Turbine Gearboxes Using In-Service Data: Current Approaches and Future Trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 50, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wu, P.; Xu, K.; Li, J. Research on Vibration Characteristics and Stress Analysis of Gearbox Housing in High-Speed Trains. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 102508–102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulia, M.; Supriadi, S.; Suardi, S. Analysis of the effect of operational load fluctuations on heavy vehicle gearbox wear. Int. J. Mech. Res. 2023, 12, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Feng, R.; Shi, W. Enhancing Autonomous Vehicles Safety Through Edge-Based Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM Symposium on Edge Computing (SEC), Wilmington, DE, USA, 6–9 December 2023; pp. 282–283. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10816-3; Mechanical Vibration—Evaluation of Machine Vibration by Measurements on Non-Rotating Parts—Part 3: Industrial Machines with Nominal Power Above 15 kW and Nominal Speeds Between 120 r/min and 15 000 r/min when Measured In Situ. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Yin, J.; Wang, W.; Man, Z.; Khoo, S. Statistical Modeling of Gear Vibration Signals and Its Application to Detecting and Diagnosing Gear Faults. Inf. Sci. 2014, 259, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, D. Data-Driven Machine Fault Diagnosis of Multisensor Vibration Data Using Synchrosqueezed Transform and Time-Frequency Image Recognition with CNN. Electronics 2024, 13, 2411. [Google Scholar]

- Bui-Ngoc, D.; Tran-Ngoc, H.; Nguyen-Ngoc, L.; Nguyen-Tran, H.; Bui-Tien, T. Deep Learning Damage Detection Using Time–Frequency Image Analysis. In Recent Advances in Structural Health Monitoring and Engineering Structures; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sa’d, M.; Jalonen, T.; Kiranyaz, S.; Gabbouj, M. Quadratic Time–Frequency Analysis of Vibration Signals for Diagnosing Bearing Faults. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.01172. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Gao, L. Integrated Gradient-Based Continuous Wavelet Transform for Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Sensors 2022, 22, 8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouel-Seoud, S.A. Maintenance Cost Optimization of Faculty Gearbox Under Continuous Vibration Measurement Monitoring. Int. J. Veh. Struct. Syst. 2016, 8, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Aherwar, A.; Khalid, S. Vibration analysis techniques for gearbox diagnostic: A review. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 2012, 3, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Liao, W.; Chen, X.; Lu, X. A Vibration Recognition Method Based on Deep Learning and Signal Processing. Eng. Mech. 2021, 38, 230–246. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lapira, E.; Bagheri, B.; Kao, H. Recent Advances and Trends in Predictive Manufacturing Systems in Big Data Environment. Manuf. Lett. 2013, 1, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiya, K.; Arima, S. Classification of Multivariate Time Series Signals Using Self-Supervised Representation Learning for Condition Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Semiconductor Manufacturing (ISSM), Tokyo, Japan, 9–10 December 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, V.; Costa, M.F.P.; Oliveira Ferreira, M.J.; Pinto, T.; Figueiredo, V. Application of a Self-supervised Learning Technique for Monitoring Industrial Spaces. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2023 Workshops; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 407–420. [Google Scholar]

- Sukanya, N.; Raja, S. An Unsupervised Approach for Detection of Encrypted IoT Anomalies Using Variational Autoencoder and Isolation Forest Techniques. Int. J. Comput. Technol. 2025, 16, 3677–3685. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, N.V.S.; Venkata Ramana, V.S.N.; Sravani, A.; Sreenivasulu, P.; Sriram Vikas, K. IoT for Vibration Measurement in engineering Research. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 59, 1792–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojandi, A. Unsupervised Machine Learning for Cybersecurity Anomaly Detection in Traditional and Software-Defined Networking Environments. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 22, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Raja, R.; Dewangan, A.; Kumar, M.; Soni, A.; Saudagar, A.K.J. Revolutionising Anomaly Detection: A Hybrid Framework Integrating Isolation Forest, Autoencoder, and ConvLSTM. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2025, 67, 11903–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Nguyen, C.N.; Dao, X.T.; Duong, Q.T.; Pham, D.P.T.K.; Pham, M.T. Variational Autoencoder for Anomaly Detection: A Comparative Study. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.13561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Jiang, L.; Li, F.; Chen, Y. A Multi-Scale Self-Supervision Approach for Bearing Anomaly Detection Using Sensor Data Under Multiple Operating Conditions. Sensors 2025, 25, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praveenkumar, T.; Saimurugan, M.; Krishnakumar, P.; Ramachandran, K.I. Fault Diagnosis of Automobile Gearbox Based on Machine Learning Techniques. Procedia Eng. 2014, 97, 2092–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Long, H. Wind Turbine Gearbox Failure Identification with Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inform. 2016, 13, 1360–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusa, E.; Cibrario, L.; Delprete, C.; Di Maggio, L.G. Explainable AI for Machine Fault Diagnosis: Understanding Features’ Contribution in Machine Learning Models for Industrial Condition Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.K.; Sugumaran, V.; Amarnath, M. Acoustic Signal Based Condition Monitoring of Gearbox using Wavelets and Decision Tree Classifier. Ind. J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Hu, X. A Health Assessment Technique Based on WPD and Multiple Linear Regression Analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2437, 012099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.S.; Al-Haddad, L. Towards Fault Diagnosis Interpretability: Gradient Boosting Framework for Vibration-Based Detection of Experimental Gear Failures. J. Dyn. Monit. Diagn. 2025, 4, 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, S.M.; Eun-Myeong, G.; Iranda, J. Scalable and Secure IoT-Driven Vibration Monitoring: Advancing Predictive Maintenance in Industrial Systems. J. Eng. Technol. 2024, 3, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Industrial System | Finishing mill gearbox in a heavy-industry application |

| Plants | Two installations (Plant 1 and Plant 2) |

| Monitoring Approach | IoT-supported continuous condition monitoring |

| Vibration Measurement Points | 6 locations on gearbox housing |

| Sensor Orientation | Radial directions (X and Y axes) |

| Monitored Shaft | Shaft 1 bearing locations |

| Vibration Metrics | RMS vibration velocity (in/s RMS) |

| Sampling and Aggregation | Continuous acquisition, aggregated to 1 s RMS |

| Process Variables | Mill feed rate (T/h), motor power (kW), lubrication oil temperature (°C), lubrication feed-end pressure (bar), and lubrication discharge-end pressure (bar) |

| Operating Regimes | Stopped, startup, and steady-state |

| Monitoring Duration | ~6 months per plant |

| Dataset Size | ~2 × 106 synchronized samples per plant |

| Diagnostic Focus | Machine learning-based diagnosis of a previously detected gearbox anomaly |

| Target | Model | Valid N | Validation R2 | Validation RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1OBX | Neural (boosted) | 333 | 0.9883 | 0.0037 |

| S1OBX | Boosted Tree | 333 | 0.9940 | 0.0046 |

| S1OBX | k-Nearest Neighbors | 333 | 0.9707 | 0.0102 |

| S1OBY | Neural (boosted) | 333 | 0.9926 | 0.0053 |

| S1OBY | Boosted Tree | 333 | 0.9934 | 0.0080 |

| S1OBY | k-Nearest Neighbors | 333 | 0.97012 | 0.01713 |

| Target | Model | Valid N | Validation R2 | Validation RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1OBX | Neural (boosted) | 333 | 0.9878 | 0.0036 |

| S1OBX | Boosted Tree | 333 | 0.9928 | 0.0028 |

| S1OBX | k-Nearest Neighbors | 333 | 0.9689 | 0.0058 |

| S1OBY | Neural (boosted) | 333 | 0.9911 | 0.0055 |

| S1OBY | Boosted Tree | 333 | 0.9936 | 0.0047 |

| S1OBY | k-Nearest Neighbors | 333 | 0.9718 | 0.0099 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Primera, E.; Fernández, D.; Rodríguez-Prieto, A. Diagnostic Analytics Powered by IoT and Machine Learning for the Fault Evaluation of a Heavy-Industry Gearbox. Machines 2026, 14, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14020187

Primera E, Fernández D, Rodríguez-Prieto A. Diagnostic Analytics Powered by IoT and Machine Learning for the Fault Evaluation of a Heavy-Industry Gearbox. Machines. 2026; 14(2):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14020187

Chicago/Turabian StylePrimera, Ernesto, Daniel Fernández, and Alvaro Rodríguez-Prieto. 2026. "Diagnostic Analytics Powered by IoT and Machine Learning for the Fault Evaluation of a Heavy-Industry Gearbox" Machines 14, no. 2: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14020187

APA StylePrimera, E., Fernández, D., & Rodríguez-Prieto, A. (2026). Diagnostic Analytics Powered by IoT and Machine Learning for the Fault Evaluation of a Heavy-Industry Gearbox. Machines, 14(2), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14020187