Impact and Detection of Coil Asymmetries in a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator with Parallel Connected Stator Coils

Abstract

1. Introduction

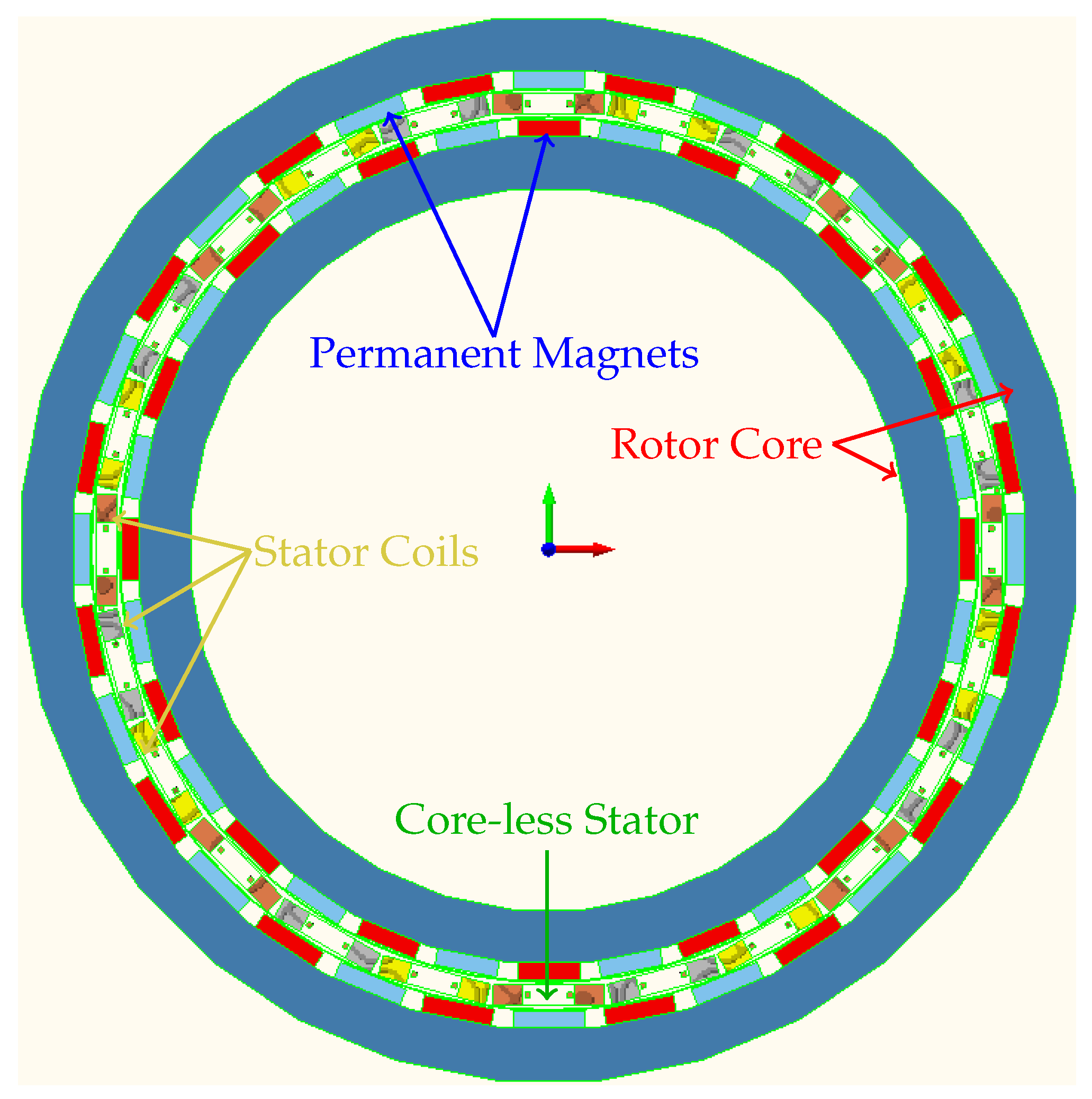

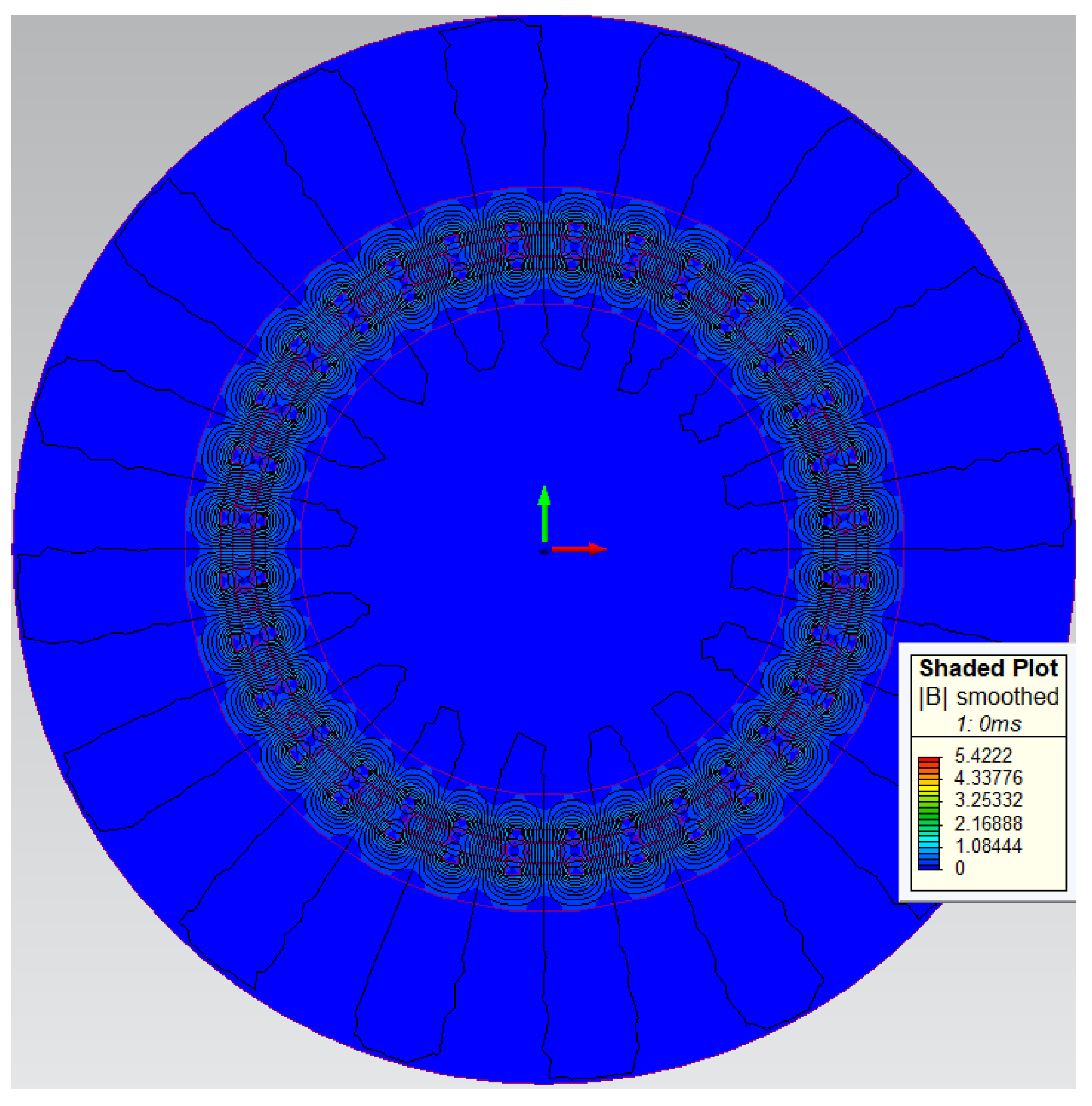

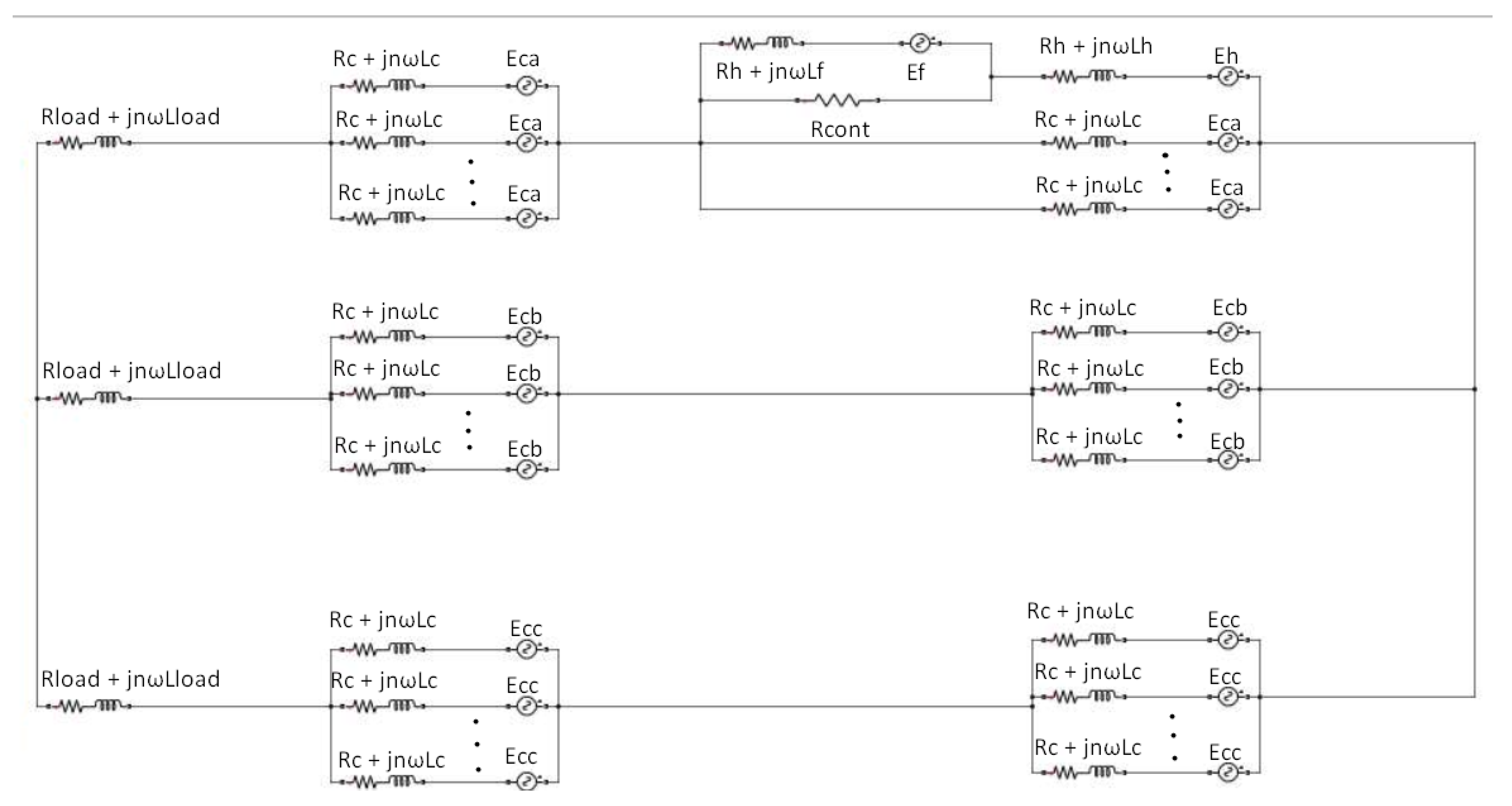

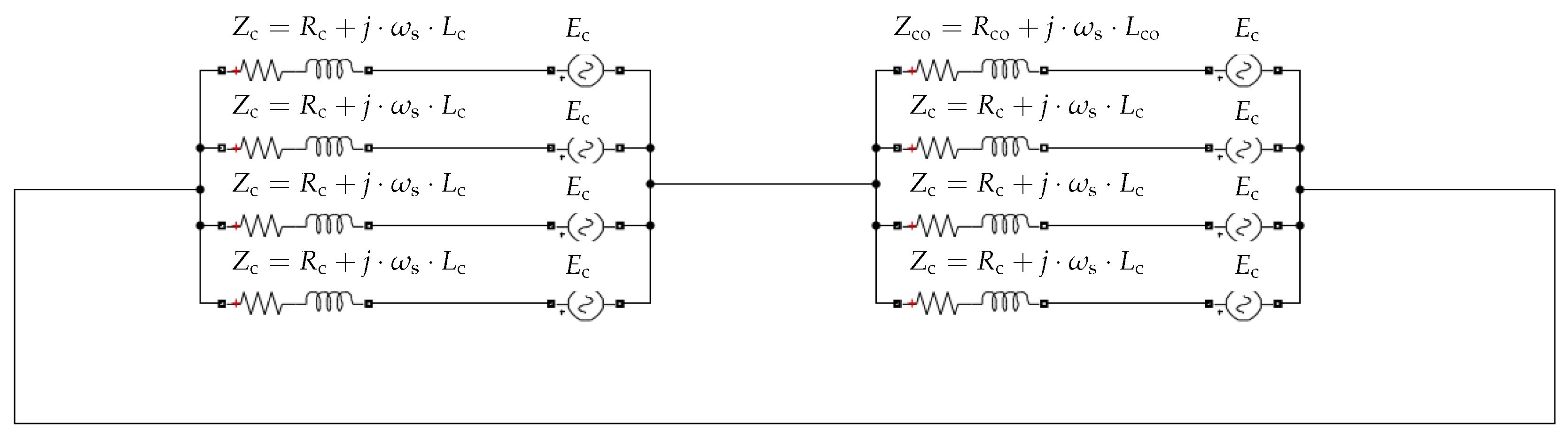

2. Model Development

3. Mathematical Modeling

3.1. Analysis of C-Gen Under Impedance Imbalance

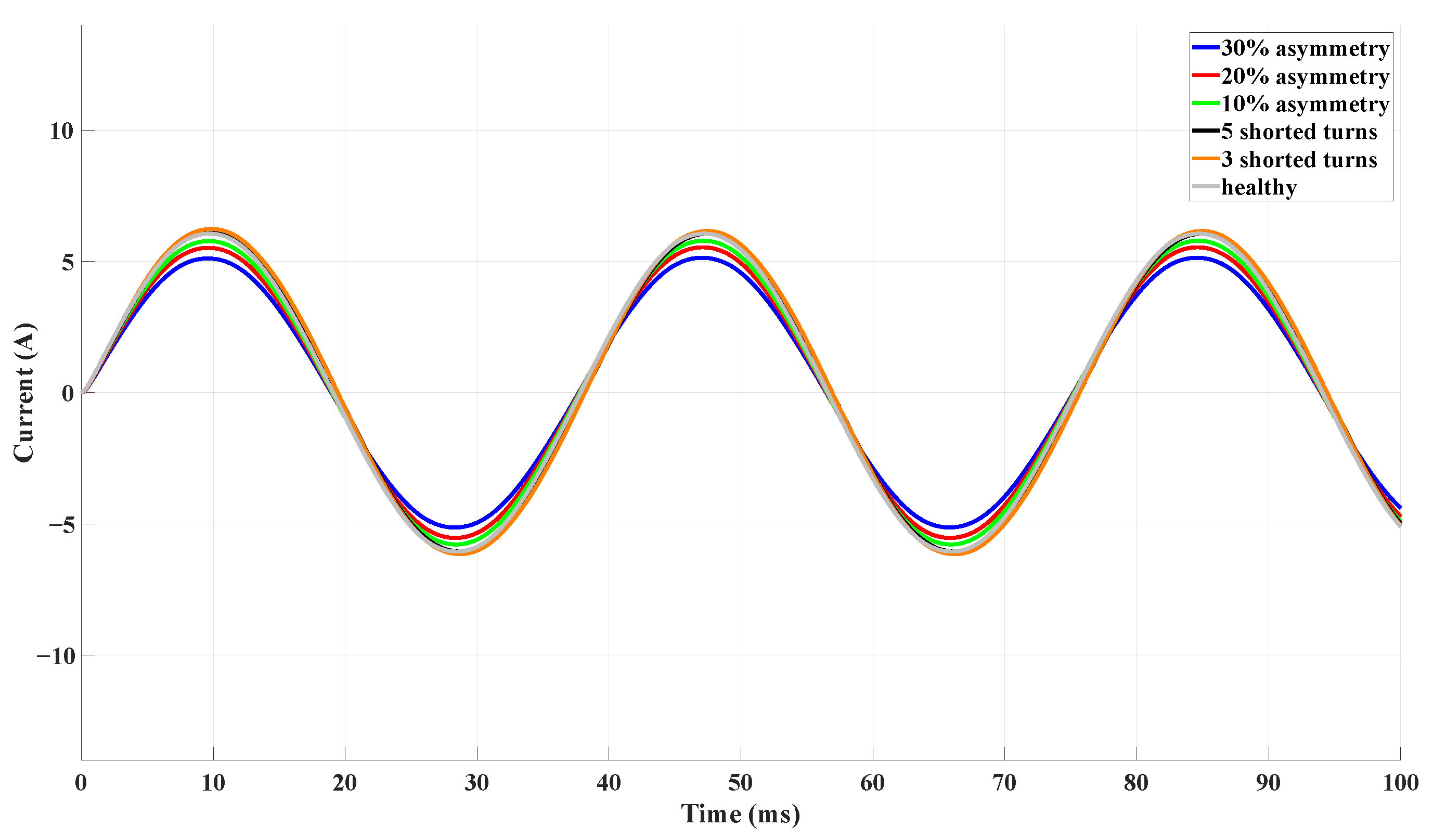

Simulation Results

4. Diagnostic Techniques

4.1. Negative-Sequence Current

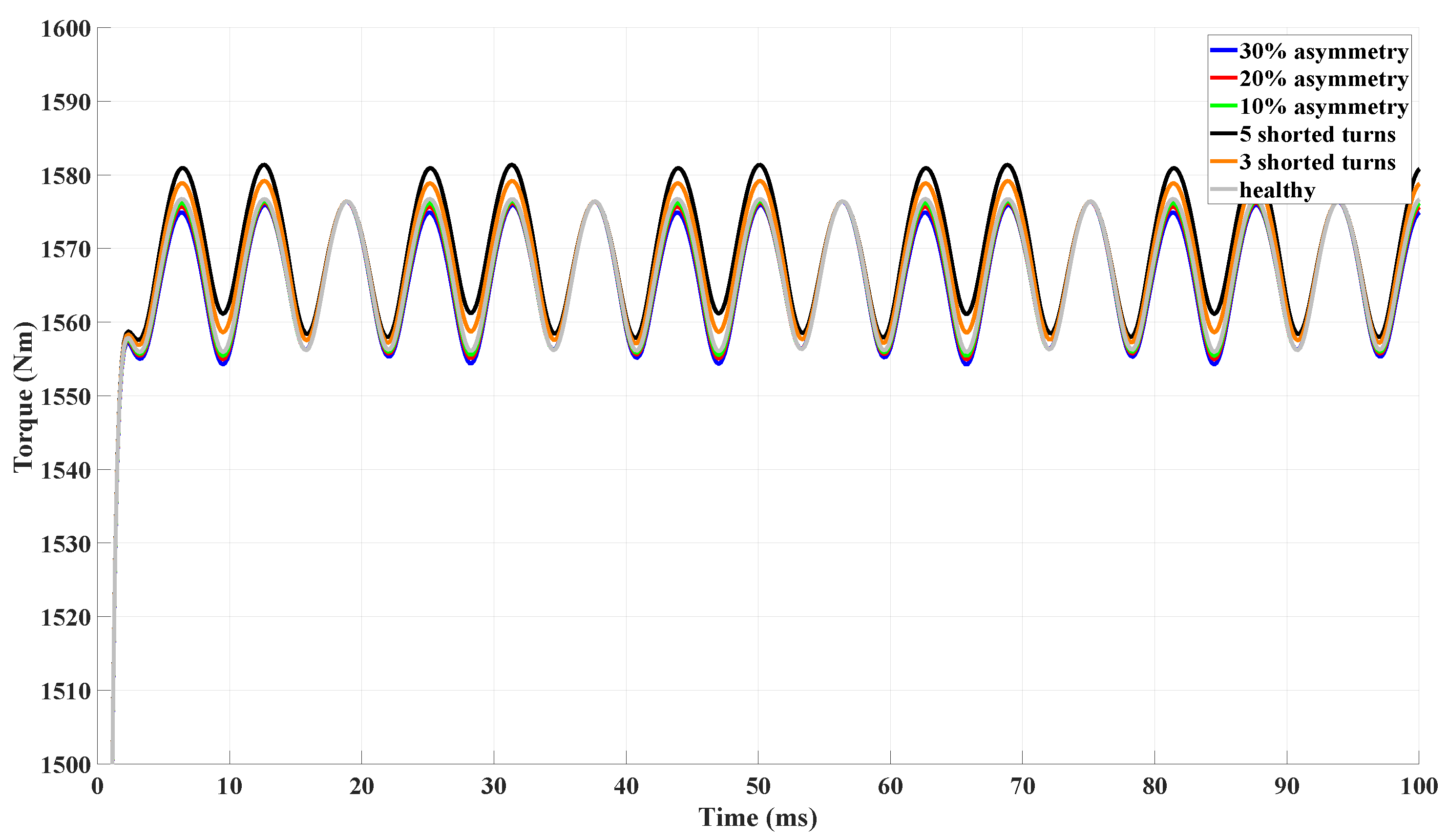

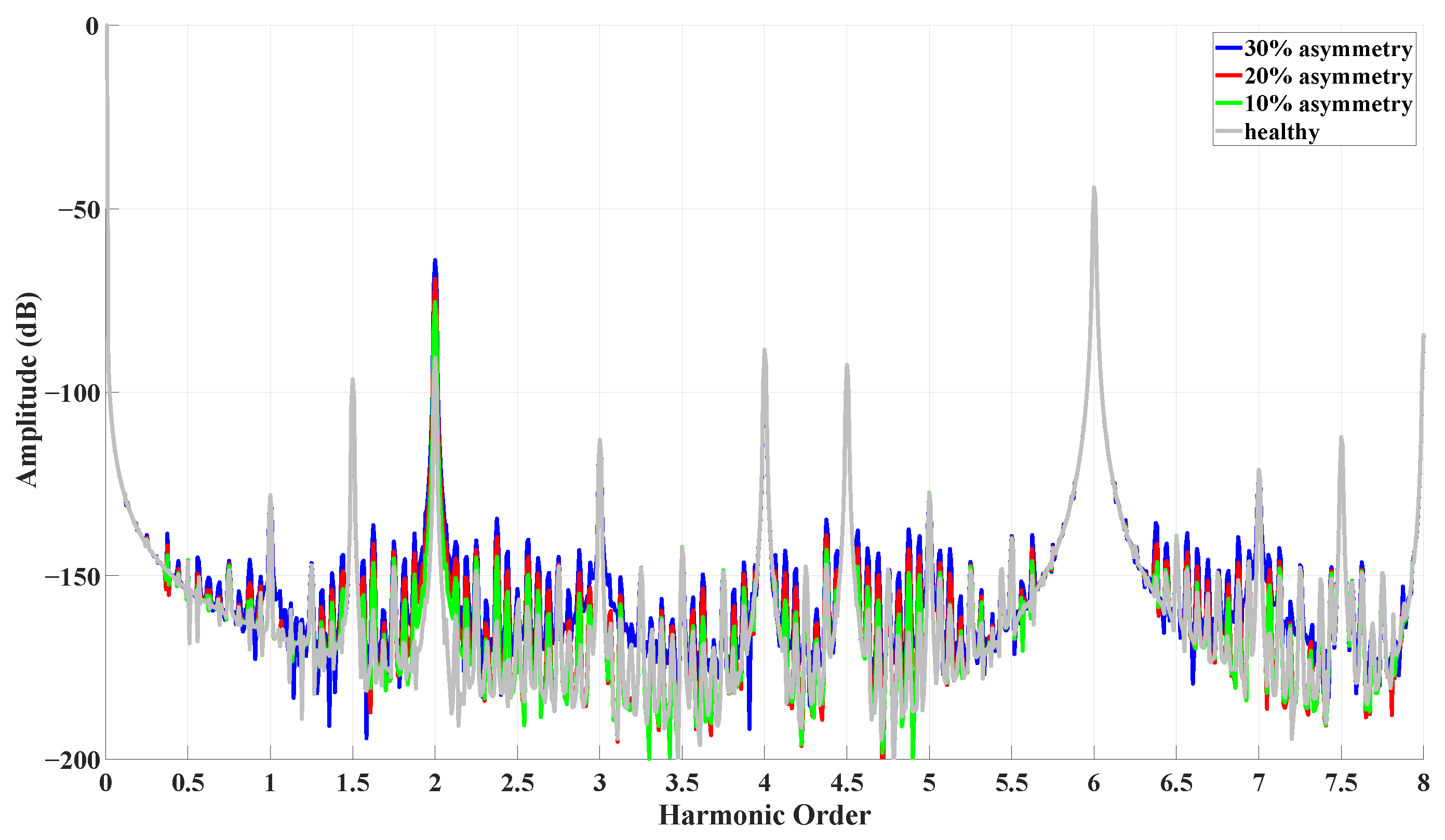

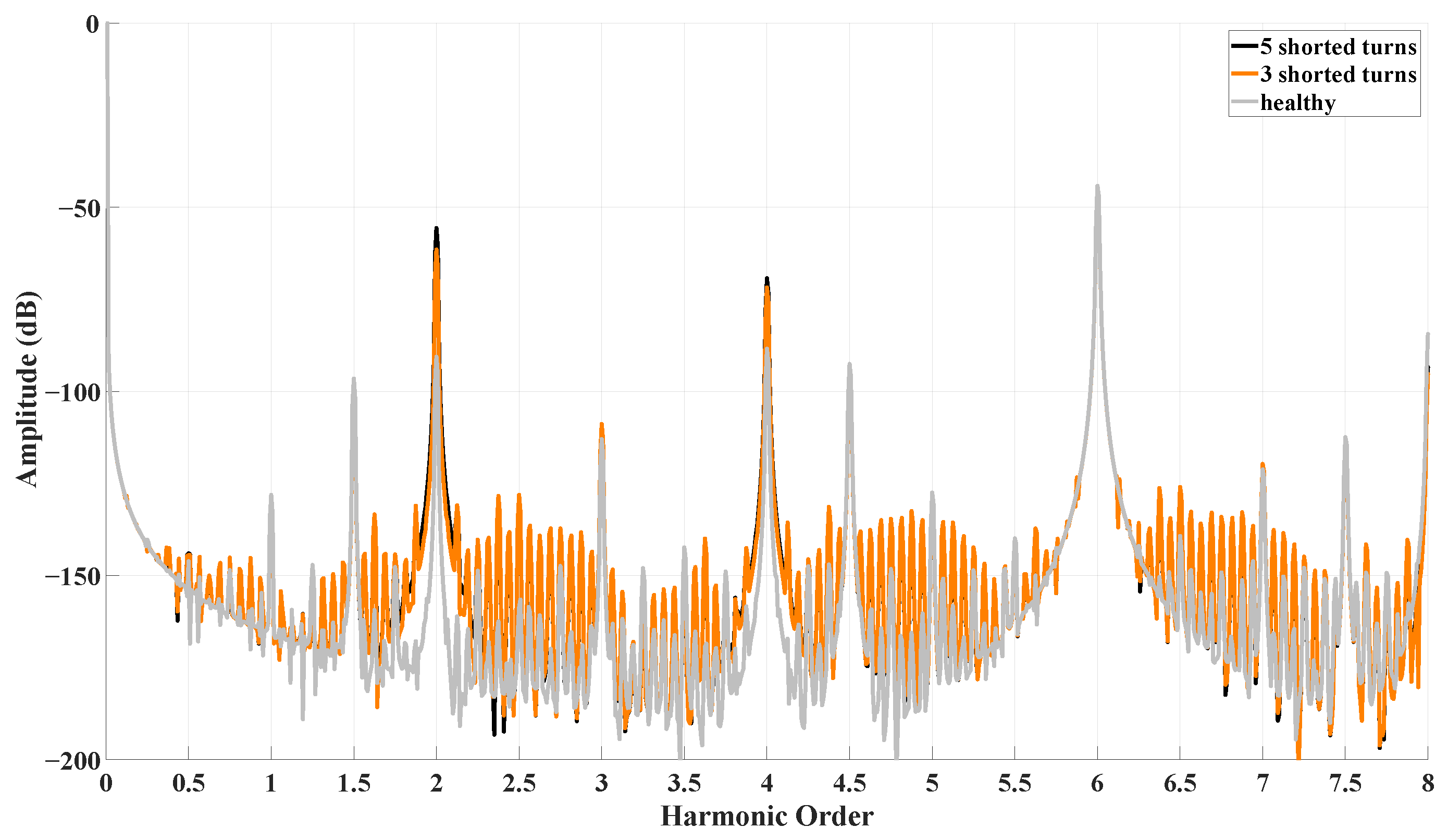

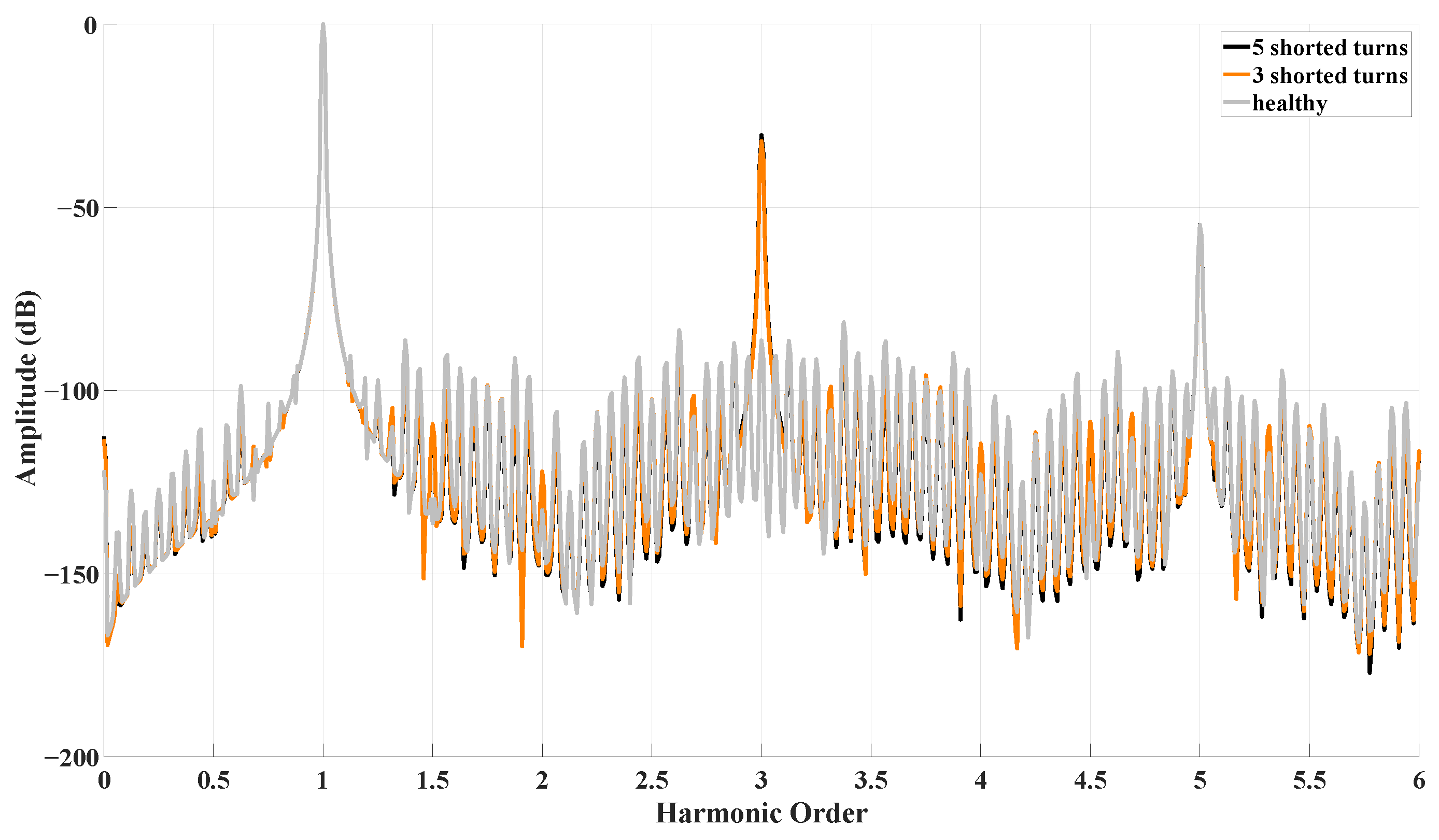

4.2. Torque Analysis

5. Conclusions & Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- von Jouanne, A.; Agamloh, E.; Yokochi, A. A Review of Offshore Renewable Energy for Advancing the Clean Energy Transition. Energies 2025, 18, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keysan, M.; Mueller, A.; McDonald, N.; Hodgins, N.; Shek, J. Designing the C-GEN Lightweight Direct Drive Generator for Wave and Tidal Energy. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2012, 6, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera-Guasp, M.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A.; Capolino, G.-A. Advances in Electrical Machine, Power Electronic, and Drive Condition Monitoring and Fault Detection: State of the Art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 1746–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergakis, A.; Salinas, M.; Gkiolekas, N.; Gyftakis, K.N. A Review of Condition Monitoring of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: Techniques, Challenges and Future Directions. Energies 2025, 18, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Z.-Q.; Azar, Z.; Clark, R.; Wu, Z. Fault Detection of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: An Overview. Energies 2025, 18, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.; Cros, J.; Picard, M. Real-Time Modeling of Static, Dynamic and Mixed Eccentricity in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. Machines 2025, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengifo, J.; Moreira, J.; Vaca-Urbano, F.; Alvarez-Alvarado, M.S. Detection of Inter-Turn Short Circuits in Induction Motors Using the Current Space Vector and Machine Learning Classifiers. Energies 2024, 17, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wu, Z. On-Line Detection of Demagnetization for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor via Flux Observer. Machines 2022, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S.; Vaimann, T.; Asad, B.; Kallaste, A.; Sardar, M.U.; Kudelina, K. State-of-the-Art Techniques for Fault Diagnosis in Electrical Machines: Advancements and Future Directions. Energies 2023, 16, 6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsuga, Á; Dineva, A. Early Detection of ITSC Faults in PMSMs Using Transformer Model and Transient Time-Frequency Features. Energies 2025, 18, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhou, L.; Cao, Z.; Yao, G. Fault-Tolerant Control Strategy with Asymmetric Phase Currents for Single to Four-Phase Open-Circuit Faults of Six-Phase PMSM. Energies 2021, 14, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Rios, J.; Aciego, J.J.; Gonzalez-Prieto, A.; Gonzalez-Prieto, I.; Duran, M.J.; Lara-Lopez, R. Remaining Secondary Voltage Mitigation in Multivector Model Predictive Control Schemes for Multiphase Electric Drives. Machines 2025, 13, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Song, P.; Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Kar, N.C. Open-Phase Fault Modeling for Dual Three-Phase PMSM Using Vector Space Decomposition and Negative Sequence Components. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2022, 58, 8204106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górny, K.; Kuwałek, P.; Pietrowski, W. Increasing Electric Vehicles Reliability by Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Motor Winding Faults. Energies 2021, 14, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, W.; Abd El Geliel, M.; Lotfy, A. Fault Diagnosis of PMSG Stator Inter-Turn Fault Using Extended Kalman Filter and Unscented Kalman Filter. Energies 2020, 13, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Liu, K.; Hu, W.; Peng, X.; Chen, Y.; Ding, R. Short-Time Adaline Based Fault Feature Extraction for Inter-Turn Short Circuit Diagnosis of PMSM via Residual Insulation Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 3103–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiolekas, N.; Sergakis, A.; Mueller, M.; Gyftakis, K.N. Analysis and Diagnosis of ITSC in Dual Rotor Air-Cored PMSG-Parallel Connected Stator Coils. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Symposium on Diagnostics for Electric Machines, Power Electronics and Drives (SDEMPED), Dallas, TX, USA, 24–27 August 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drif, M.; Drif, M.; Estima, J.O.; Cardoso, A.J.M. The use of the stator instantaneous complex apparent impedance signature analysis for discriminating stator winding faults and supply voltage unbalance in three-phase induction motors. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition, Denver, CO, USA, 15–19 September 2013; pp. 4403–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyftakis, K.N.; Kappatou, J.C. The Zero-Sequence Current as a Generalized Diagnostic Mean in Δ-Connected Three-Phase Induction Motors. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2014, 29, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wu, L.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y. Negative Sequence Current Suppression of Dual Three-Phase Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines Considering Inductance Asymmetry. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Harbin, China, 11–14 August 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, A.; Sułowicz, M. A New Effective Method of Induction Machine Condition Assessment Based on Zero-Sequence Voltage (ZSV) Symptoms. Energies 2020, 13, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.M.R.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Comparing power transformer turn-to-turn faults protection methods: Negative sequence component versus space vector algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 10th International Symposium on Diagnostics for Electrical Machines, Power Electronics and Drives (SDEMPED), Guarda, Portugal, 1–4 September 2015; pp. 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Jiang, M.; Lu, T.; Hu, F.; Huang, Y.; Ma, C.; Song, W. Comparative Study of Negative Sequence Current-based and Current Residual-based Online Diagnosis Method for Inter-turn Faults in PMSM Drives. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Power Engineering (ICPE), Shanghai, China, 13–15 December 2024; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstner, G.; Kugi, A.; Kemmetmüller, W. Fault-tolerant torque control of a three-phase permanent magnet synchronous motor with inter-turn winding short circuit. Control Eng. Pract. 2021, 113, 104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsanullah, K.; Panda, S.K.; Shanmukha, R.; Nadarajan, S. Inter-turns fault diagnosis for surface permanent magnet based marine propulsion motors. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 2nd Annual Southern Power Electronics Conference (SPEC), Auckland, New Zealand, 5–8 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rated Power (kW) | 21.5 |

| Rated Speed (rpm) | 100 |

| Stator | Core-less |

| Frequency (Hz) | 26.67 |

| Pole pairs | 16 |

| Stator coils | 24 × single concetrated |

| Stator coil turns | 205 |

| Magnet material | N42 |

| FEA | Experimental | Deviation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase Voltage (V) | 301.2 | 306.7 | 1.79 |

| Phase Current (A) | 17.19 | 17.41 | 1.28 |

| Torque (Nm) | 1565 | 1575 | 0.63 |

| Electrical Power (kW) | 15.5 | 15.4 | −0.65 |

| Mechanical Power (kW) | 16.4 | 16.5 | 0.61 |

| Efficiency (%) | 94.5 | 93.3 | −1.29 |

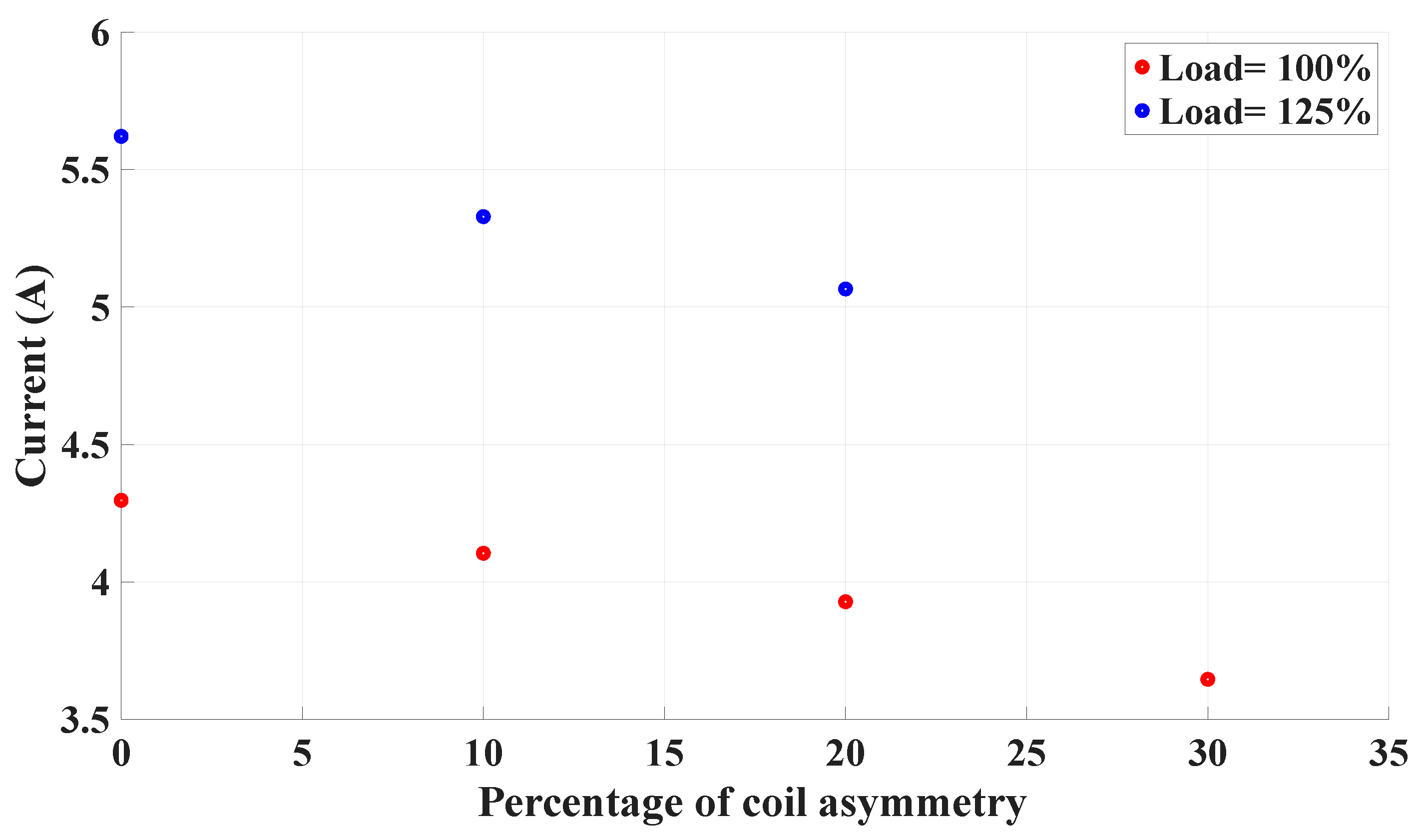

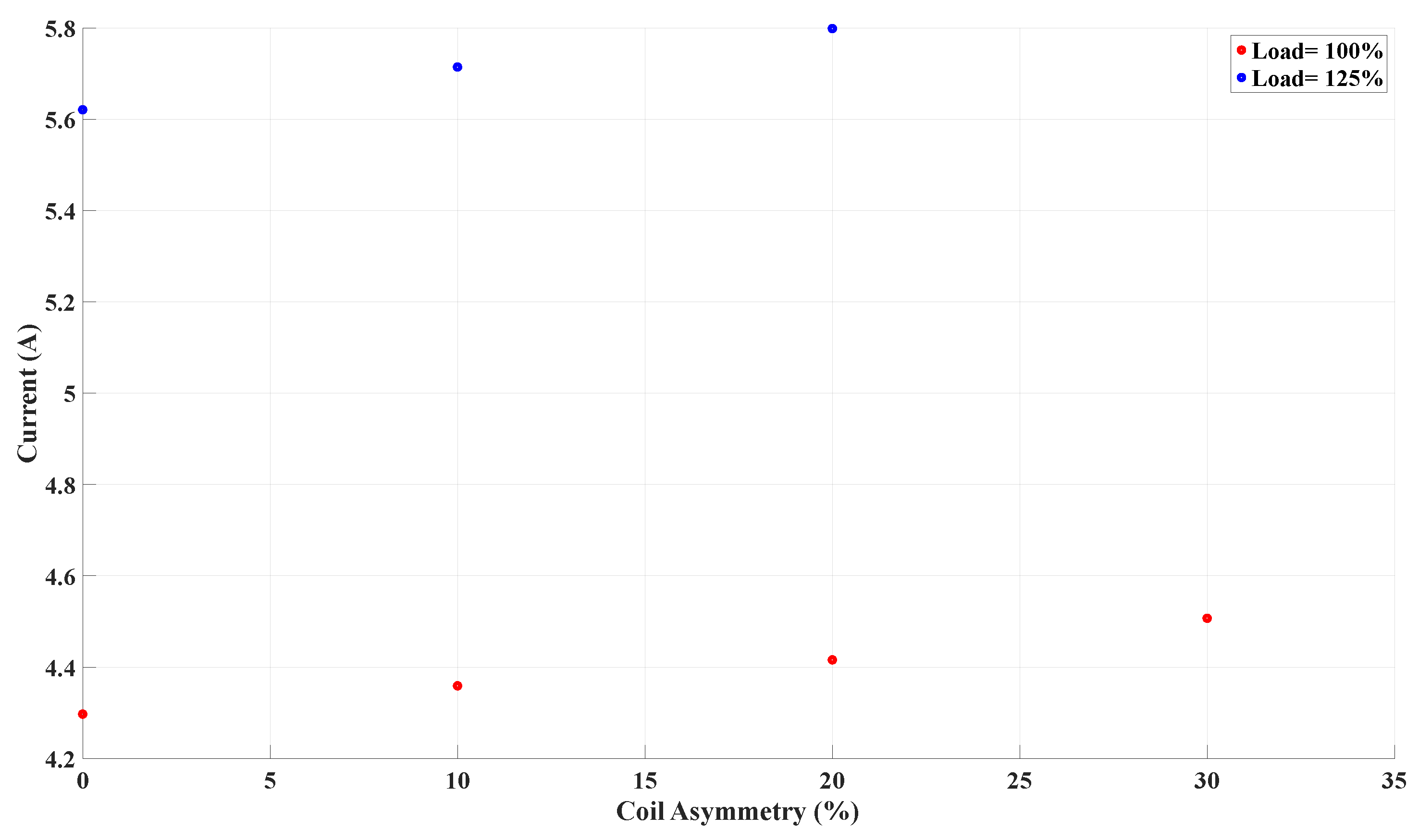

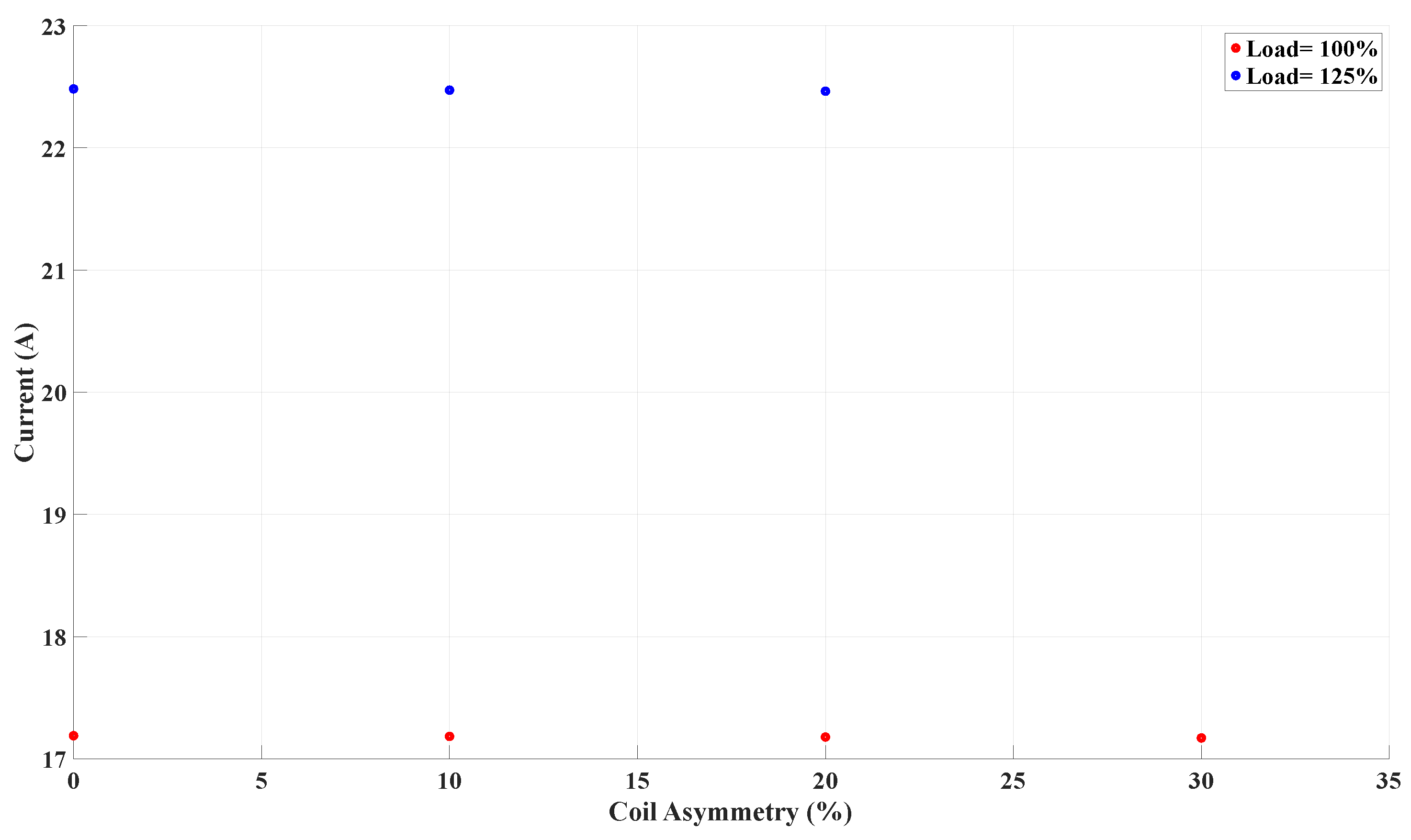

| Fault Scenario | RMS Value of Phase Current (A) | RMS Value of Imbalanced Coil Current (A) | Range of Current Reduction for the Imbalanced Coil (%) | Simulation Current Reduction for the Imbalanced Coil (%) | RMS Value of Parallel Connected Coil Current (A) | Range of Current Growth for the Parallel Connected Coil (%) | Simulation Current Growth for the Parallel Connected Coil (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | 17.19 | 4.30 | 0 | 0 | 4.30 | 0 | 0 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 17.18 | 4.10 | 6.98–8.05 | 4.65 | 4.36 | 1.15–2.33 | 1.40 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 17.18 | 3.93 | 13.04–14.89 | 8.60 | 4.42 | 2.13–4.35 | 2.79 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 17.17 | 3.65 | 18.37–20.79 | 15.15 | 4.51 | 2.97–6.12 | 4.88 |

| Healthy | 22.48 | 5.62 | 0 | 0 | 5.62 | 0 | 0 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 22.47 | 5.33 | 6.98–8.05 | 5.44 | 5.71 | 1.15-2.33 | 1.60 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 22.46 | 5.07 | 13.04–14.89 | 10.14 | 5.80 | 2.13–4.35 | 3.20 |

| Fault Scenario | RMS Value of Phase Current (A) | RMS Value of Shorted Coil Current (A) | RMS Value of Parallel Connected Coil Current (A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 shorted turns and | 17.19 | 4.38 | 4.27 |

| 3 shorted turns and | 17.19 | 4.25 | 4.32 |

| 5 shorted turns and | 17.19 | 4.30 | 4.30 |

| 5 shorted turns and | 17.18 | 3.99 | 4.40 |

| 7 shorted turns and | 17.18 | 4.20 | 4.33 |

| 7 shorted turns and | 17.17 | 3.67 | 4.51 |

| 9 shorted turns and | 17.18 | 4.06 | 4.38 |

| 9 shorted turns and | 17.16 | 3.30 | 4.63 |

| Fault Scenario | NSC (mA) |

|---|---|

| Healthy | 0.65 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 3.51 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 6.56 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 11.40 |

| ITSC 3 shorted turns, | 4.03 |

| ITSC 5 shorted turns, | 3.69 |

| Healthy | 0.81 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 6.69 |

| Coil asymmetry , | 12.57 |

| ITSC 3 shorted turns, | 5.48 |

| Fault Scenario | Amplitude of 2nd Order Harmonic (dB) | Amplitude of 4th Order Harmonic (dB) |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy | −90.60 | −88.42 |

| Coil asymmetry , | −75.38 | −88.62 |

| Coil asymmetry , | −69.15 | −88.85 |

| Coil asymmetry , | −64.00 | −89.31 |

| ITSC 3 shorted turns, | −61.48 | −71.76 |

| ITSC 5 shorted turns, | −55.68 | −69.28 |

| Healthy | −90.60 | −88.42 |

| Coil asymmetry , | −75.38 | −88.62 |

| Coil asymmetry , | −69.15 | −88.85 |

| ITSC 3 shorted turns, | −61.48 | −71.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gkiolekas, N.; Sergakis, A.; Salinas, M.; Mueller, M.; Gyftakis, K.N. Impact and Detection of Coil Asymmetries in a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator with Parallel Connected Stator Coils. Machines 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010006

Gkiolekas N, Sergakis A, Salinas M, Mueller M, Gyftakis KN. Impact and Detection of Coil Asymmetries in a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator with Parallel Connected Stator Coils. Machines. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkiolekas, Nikolaos, Alexandros Sergakis, Marios Salinas, Markus Mueller, and Konstantinos N. Gyftakis. 2026. "Impact and Detection of Coil Asymmetries in a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator with Parallel Connected Stator Coils" Machines 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010006

APA StyleGkiolekas, N., Sergakis, A., Salinas, M., Mueller, M., & Gyftakis, K. N. (2026). Impact and Detection of Coil Asymmetries in a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator with Parallel Connected Stator Coils. Machines, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010006