Abstract

Industry 4.0 has driven the development of important technologies for industrial applications, but the focus has often been on technological advancement rather than on how operators interact with these systems. With the emergence of Industry 5.0, attention has shifted toward the role of the operators and their interaction with emerging technologies. This paper explores the automation of a fully manual operation in the logistics field while adopting a human-centered approach to reduce risky tasks and enhance the operator’s well-being. A motion capture system and digital human simulation software are utilized to create a digital twin of a real-world industrial case study. This approach enables the virtual testing of various automation solutions to identify the optimal scenario that meets the performance indicator parameters. This study highlights the importance of integrating ergonomic considerations into automation strategies.

1. Introduction

After ten years of Industry 4.0 development, Industry 5.0 was born by the European Commission to respond to emerging societal challenges [1]. Industry 5.0 highlights that humans and machines share the same environment and work together. For this reason, it is important to achieve a deep integration between machine intelligence and human capabilities, to achieve higher efficiency [2]. This new paradigm shifts the attention from the technologies to the human operators, focusing on social well-being, sustainability and ethical considerations [3]. Industry 5.0 aims to improve Industry 4.0 by overcoming its main limitation [4]. It is possible to define Industry 4.0 as technology driven, while Industry 5.0 is value driven [5].

Robots and machines are not replacing human operators in the Industry 5.0 scenario, but they are implemented to help and support the operators, performing dangerous or repetitive activities, and implement advanced technologies to support the operators better, letting the operator focus on tasks requiring critical thinking, empathy, and creativity. Industry 5.0 aims to implement a synergistic relationship between machines and human operators [6].

For this reason, this shift from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0 has increased focus on the well-being of operators and their health in the workplace, particularly emphasizing the study and application of human-centered applications and ergonomics. Despite the high level of automation implemented, there are a lot of assembly and production processes that are manually performed because human flexibility is not easily replaceable. This physical work that is repetitive and sometimes requires uncomfortable postures causes musculoskeletal disorders and injuries that negatively affects the operator’s health [7].

The logistics sector is the industrial sector involved in the management, movement, and storage of goods in the supply chain. The scope of the logistics sector is to ensure that products are delivered efficiently, cost effectively, and on time. Sometimes the products are collected from different sources and stored in packages based on the clients’ needs. A major problem in the logistics sector is that many logistics jobs are performed manually, including the handling of heavy products; another significant issue for operators’ health is the uncomfortable postures required to complete tasks [8].

Digital human modeling is an essential part of the smart factory because it emphasizes varied aspects, but there is not a big focus on the macro-ergonomic analysis, using simulation methods [9]. Furthermore, this project is part of the MICS (https://www.mics.tech, accessed on 3 March 2025, Made in Italy, Circular and Sustainable) project; this project aims to develop new models and techniques to promote the data science application in real industrial processes [10]. The MICS Spoke 8 project focuses on the design and the management of the factory oriented towards digitalization through artificial intelligence and data-driven approaches, and in particular the section of the projects 8.01 is called “Human Digital Twin for future manufacturing systems”. While the system analysis is carried out considering the Italian industrial scenario, the presented methodology can be implemented worldwide.

Digital twin simulation is a key aspect of the research in the MICS Spoke 8.01 projects [11]; it allows digital representation of a real-world scenario and supports the collaboration and decision-making process. This research aims to propose an approach for logistic sectors that is based on motion capture systems and digital human simulation technologies, to redesign the operations in an existing workstation with a combined ergonomic and productivity overview. It is interesting to focus on the logistic sector because as declared in [12], there are few studies on ergonomics in this field.

The structure of the paper is as follows: in Section 2 the literature review regarding ergonomics is discussed to help the reader understand the state of the art of ergonomic studies. Section 3 proposes the methodology. The specific use case is reported in Section 4. The application of the methodology in the selected workstations is reported in Section 5, which describes the path from the first analysis to the robot application. The experimental validations and the results obtained are in Section 6, with the comparison with the previous data. Conclusions and final remarks on future work are in Section 7.

2. Ergonomics

The term ergonomics comes from the Greek words érgon, that is work, and nómos, which means law, and it was first introduced by Wojciech Jastrzębowski in an article published in a Polish journal in 1857 [13]. Ergonomics, also called Human Factors Engineering, is defined by the International Association of Ergonomics (https://iea.cc, accessed on 3 March 2025) as a scientific discipline; its goal is to analyze the interaction between people and machines, robots, and other different elements that compose a specific system, trying to improve both the human activity and the performance of the system [14].

The application of Human Factors Engineering also seeks to improve the performance of manufacturing processes to enhance operators’ ease of use, reduce the risk of errors, increase efficiency, and support the physical and mental health of users [15]. Some additional advantages of an ergonomic workstation include reducing worker fatigue, preventing the generation of musculoskeletal diseases, reducing work absenteeism, and improving workers’ performance [16].

Ergonomic assessment methods are crucial for identifying risk factors and evaluating the level of ergonomic risks present in the workplace environment. Zen in [17] categorizes the ergonomic assessment techniques in four different typologies. The typologies are defined by the data sources used for the ergonomic evaluation and they are as follows:

- Checklists, surveys, and reportsErgonomic assessment checklist are often a list of items that can be analyzed by employees, directors, supervisors, or experienced professionals. Those instruments are implemented to make sure that workers’ task are optimized for comfort and productivity, and for reducing the risk of work-related injuries.

- Observation-based methodsObservation-based methods are based on a numerical framework for ergonomic occupational risk assessments. The main limitation of those techniques is that they are focused mainly on assessing work postures, and do not concentrate on work rate and static loading. Sometimes, they are used as a basis to perform a computer-based strategy for strategic planning ergonomic analysis.

- Direct measurement methodsA direct measurement method is implemented when the evaluation of the worker’s exposure to risk and musculoskeletal activity is performed during the task execution. This is typically achieved by attaching various types of sensors directly to the worker’s body.

- Computer applicationsComputer-based applications rely on frameworks and procedures that integrate other methods with artificial intelligence techniques. The combination of observation-based and computer-based applications is seen in tools like the Ergonomic Assessment Worksheet (EAWS) and the Digital Human Model (DHM).

As described, the ergonomic evaluation is used to quantify the risk associated to a specific task. It can be classified in the five levels here reported:

- Low risk: The risk of injury or musculoskeletal disorders is minimal, and the working conditions are generally safe and do not present significant physical stress.

- Medium-low risk: The risk is moderate but not immediate or severe. There are ergonomically suboptimal operations, but there are no particularly hazardous conditions.

- Medium risk: The risk is visible and significant but not severe enough to cause immediate injuries. The working conditions may lead to temporary discomfort or pain but not necessarily serious injuries.

- Medium-high risk: In this scenario, the risk is significant, with potential consequences for the worker’s health over the medium or long term, such as the risk of chronic musculoskeletal disorders.

- High risk: The risk is very high, with the likelihood of injuries or musculoskeletal disorders occurring in the short term. The working conditions are negative and present high potential for damage to health.

Ergonomics can be applied in different sectors, especially where there is a presence of human–machine interaction, with the aim of achieving human well-being, decreasing stress, and preventing injuries. Different examples are found in the literature, such as in the healthcare sectors [18,19], agriculture [20], manufacturing, logistics [21], etc.

The concept of the factory of the future is centered around the human element, which plays a central role in driving sociotechnical change [22]. This emphasizes the importance of this discipline in today’s industrial environment. Although the benefits of ergonomics are known, they are usually not considered in engineering and manufacturing processes, and the reasons are mainly that the benefits are not easily attributable to the costs incurred [23]. Additionally, companies are doubtful about the impact that human factors can have on production performance, even though many studies in the literature have demonstrated a direct correlation between system performance and worker well-being. The arising of new technologies in the past years has opened new opportunities in this field. However, companies need to be convinced of its benefits to the workers’ well-being and process performance.

There are in the literature many research works on ergonomics in the logistics sector. Zülch analyzes the advantages and drawbacks of U-shaped assembly systems over straight-line ones. Despite finding some advantages in the U-shape, this setup may still lead to a decrease in ergonomic performance [24]. Following another approach, Mocan focuses on wearable computer technology in warehouse scenarios to decrease ergonomic strain [25]. Other studies concentrate on performing ergonomic evaluations using virtual reality, which allows the assessment of the ergonomic risk of a workstation without the need for a physical prototype [26].

The Motion Capture (MoCap) systems are also well used to evaluate the ergonomics of a workstation. Battini proposes a real-time full-body ergonomic platform with the usage of a MoCap system (inertial suit) [27]. Broshe presents a methodology for leveraging individualized ergonomics analysis using a MoCap system to obtain information about the workers in order to optimize the workstation [28]. Bortolini focuses on optimizing the assembly workstation to reduce ergonomic risk. This approach takes into account the operators’ anthropometric measurements. The proposed approach includes the use of Microsoft Kinect™ for real-time variation [15].

The literature has shown the importance of DT since it allows a virtual replica of a physical system and simulates the real-world counterpart [29]. Trstenjak in [30] highlights the fact that digital human modeling can advance ergonomic design and foster a safer and more efficient environment for operators if the cost limits are overcome. He in [31] proposes a Human DT framework that combines the human factors perspective with digital techniques. Vujica-Herzog in [32] presents a system that combines MoCap and DT and evaluates the task using an ergonomic analysis.

DT has also been used in systems involving interactions between humans and robots. Baratta in [33] highlights the ability of DT to simulate a real environment for testing and optimizing collaboration between human–robot applications. Nikolakis in [34] presents a DT methodology that enables the packaging process of different products; the process is performed by a robot in an autonomous and reconfigurable solution. However, the human operator is not modeled into the system. Ramasubramanian in [35] observes that the research on industrial robot DT is growing rapidly, while DT for human–robot collaboration lags behind, mainly because it is easier to model industrial robots than collaborative ones due to the uncertainty in modeling the human-involved environment. In [36], DT is used to extend the virtual simulation models developed during the design phase of a new assembly system for various processes, including the tasks allocation between human and robot. This can be used as a starting point for the following research.

This article proposes a human-centered methodology for optimizing a manual workstation in the field of logistics. A DT As-Is scenario can be created using the data collected by the MoCap system. This allows optimizations based on the real setup of the workstation. The simulated scenario, created based on DT with the inclusion of a robot, allows to evaluate the ergonomic risk and preliminary performance in the new scenario.

3. Methodology

The methodology implemented in this project can be divided in five different steps that are analyzed in this section. Those steps are as follows:

- Time analysis.

- Motion capturing acquisition.

- Digital human simulation (digital twin).

- Ergonomic evaluation.

- Collaborative robot application.

This methodology aims to provide an approach that can be easily replicated in different workstations and logistics sites with similar types of activity. The selection of the workstation to be studied is carefully analyzed in order to identify one that would allow the identified optimization to be used at different workstations within the company.

3.1. Time Analysis

The objective of this analysis is to clearly define the task sequence of the activity, the cycle time, and the relative time required for each task. The time analysis is performed manually by filming the operator performing the activity. The different tasks and their duration are identified through the video. This analysis is important for ergonomic assessment and also for identifying task allocation when implementing human–robot optimization. For the purpose of this study, this time analysis is sufficient, there is no need to implement a more sophisticated method.

3.2. Motion Capturing Acquisition

Motion capture is the process that allows to digitally track and record the movements of objects, people, or animals. Different technologies have been used for this scope, such as inertial sensors, camera-based sensors, or a mixed system that use a combination of the previous ones [37]. There are many research and literature reviews on the use of MoCap in the industrial field related to ergonomic analysis, confirming its validity in the industrial field. Rybnikár in [7] declares that MoCap is used the most for ergonomics evaluation in industry and logistics than in other fields. Menolotto in [37] aims to provide insight into the capabilities and limitations of MoCap solutions in industrial applications. Salisu in [38] describes all the types of MoCap used in the ergonomic field and their application, with a special focus on diagnostics. Petrosyan [39] studies how MoCap technology is applied in the ergonomic assessment process.

The Xsens (https://www.movella.com/products/xsens (accessed on 13 December 2024)) system is used in the project to perform the MoCap acquisition. Xsens is an advanced motion-tracking solution that delivers precise, real-time data on human body movements. Xsens is a widely used MoCap since it allows users to perform motion acquisition in all environments. Moreover, the calibration process is easy to perform, and the system can export the data and process them to obtain a 3D representation [38].

Utilizing Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), this motion capture system eliminates the need for external cameras or complex setups. The sensors can be integrated into clothing or attached directly to the body with straps, enabling highly accurate tracking of body movements and capturing a full range of motion, even in challenging environments such as outdoor settings or confined spaces. Additionally, the Xsens system seamlessly interfaces with various DHM software v2025-R1, such as IPS IMMA (https://flexstructures.com/products/ips-imma, accessed on 3 March 2025, Intelligently Moving Manikins, version 2025-R1). This integration facilitates the creation of a detailed digital twin of the target scenario, allowing users to assess critical factors such as reachability, visibility, ergonomic risks, and more.

3.3. Digital Human Simulation (Digital Twin)

Digital human simulation involves modeling realistic models that mimic human appearance, behavior, and emotions. A DT is a virtual replica of a physical object, system, or process. It uses real-time data and simulations to mirror the real-world counterpart, replicating the behavior to monitor, simulate, predict, and optimize [40]. Essentially, it is a digital version of something that exists in the physical world, whether it is machinery, buildings, cities, or even human beings. Hauge in [41] declares that DT can simulate complex scenarios that are very close to reality and can be a supporting element when new technologies and installations are introduced in an existing physical environment. According to Berti in [42], DT can be used to evaluate human factors in the logistic sector, while in the literature, there is a lack of frameworks tested in real industrial working environments. DT can be a supportive tool in the logistic sector, where many operations are mainly performed due to the complexity of the interaction; in [41], DT is used to support the decision-making process.

A human digital twin (HDT) refers to a virtual representation of a person, created by using real-time data and various technologies like sensors, wearables, and artificial intelligence [43]. HDT is a core technology in Industry 5.0, and it connects humans and technologies to increase their possibilities [44]. There are many applications related to HDT and ergonomics. Caputo [45], leveraged digital twins to assess the ergonomic risk of an assembly workstation, minimizing the time required to develop and design a new assembly line. In [46], Maruyama proposed a system where DT and HDT were applied to recreate a virtual representation of the full-body posture and the robot behavior; the goal was to increase the ergonomic assessment, and motion analysis was used. Cibrario [47] proposed a new simple methodology to perform a heuristic evaluation for the design of a human–robot collaboration workstation.

The software that would be used in this project to create the HDT is IPS IMMA, version 2025-R1, which is a digital human modeling (DHM) software with advanced path-planning techniques. These techniques allow placing the manikin in an ergonomic posture, preventing collisions with the workspace and itself, and meeting the grasping and visual constraints [48]. Additionally, its integration with IPS Robotics allows the creation of scenarios that involve human–robot collaboration.

3.4. Ergonomic Evaluation

The ergonomic evaluation is an important parameter to understand the relationship between workers and their working environment, with the objective of recognizing potential ergonomic risk factors in the workplace. This is very important for worker safety since the consequences of workplaces with poor ergonomic performances can be severe, including death and disability [49]. Examples of potential ergonomic risk factors include repetitive high-frequency motion, static posture, heavy lifting, forceful exertion, exposure to excessive vibration, and more.

The EAWS Whole-Body assessment is selected as an ergonomic evaluation method. It is a holistic ergonomic method used to evaluate the physical demands, in particular, the biomechanical loads on the entire body and upper limbs [50]. This methodology is usually applied in industrial environments, such as manufacturing, automotive, aerospace, and defense. The goal of the EAWS is to design ergonomic workplaces by mitigating musculoskeletal disorders. EAWS consolidates various biomechanical risks into an overall risk score for all work activities, aligning with ISO and CEN (https://www.en-standard.eu (accessed on 2 December 2024) standards. Moreover, this methodology is already implemented on the digital human model (DHM) software (IPS IMMA) that would be used to create the digital twin of the working place, allowing its application directly on the As-Is and optimized simulation. EAWS Whole-Body can be divided into the following sections:

- Section 0—Extra Points: Captures additional loads not included in other sections.

- Section 1—Postures: Evaluates body positions, including static postures and high-frequency movements. This section considers the symmetric and asymmetric postures based on duration and discomfort.

- Section 2—Action Forces: Assesses force exertion tasks (greater than 30 N with hands or 40 N with arms/whole body).

- Section 3—Manual Material Handling (MMH): Analyzes tasks involving carrying, holding, pushing, or pulling loads greater than 3 kg.

3.5. Collaborative Robot Application

In recent years, the integration of collaborative robots (cobots) into industrial environments has gained momentum, primarily driven by their potential to improve productivity, safety, and ergonomic conditions for human workers. Cobots are increasingly used in tasks such as pick-and-place, screwing, and inspection, where they can operate safely alongside humans without the need for physical barriers, thanks to their built-in safety features and compliance with standards such as ISO/TS 15066 [51]. Moreover, despite the growing evidence that cobots can mitigate the risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSD), ergonomics and human factors (E&HF) are still too often considered as outcomes of implementation rather than core design requirements [51]. Furthermore, as highlighted by Cardoso et al. [52], there is a notable lack of real-world studies where ergonomic improvements are proactively embedded into the workstation design and cobot task planning.

A robot is included in the workstation simulation to support the operator and reduce ergonomic risks. The primary requirement is to select a type of robot that can work closely and safely alongside humans. For this reason, a collaborative robot (cobot) is chosen, as it implements safety constraints and is designed to be inherently safe. As analyzed in [53], the scientific literature defines three-dimensional workspace sharing, collaborative and cooperative tasks, programming, and interaction.

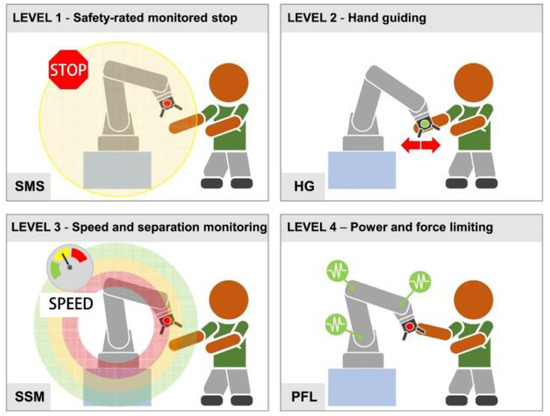

As shown in Figure 1 the ISO 10218-1/2 [54,55] defines four different scenarios: (i) Safety rated Monitoring Stop (SMS), (ii) Hand Guiding (HG), (iii) Speed and Separation Monitoring (SSM), and (iv) Power and Force Limiting (PFL). In all of these working conditions, cobots share their environment with humans [56], which is why they are equipped with sensors, force-limiting features, and other technologies to prevent accidents or harm to humans. They are typically used in tasks where human interaction is required, such as assembly, packaging, inspection, and more. Cobots can support the operator in carrying on physical, cognitive, and hazardous tasks [57].

Thanks to the development of Industry 4.0, the integration of cobots in the industrial sector has increased, while Industry 5.0 is shifting the focus on taking into account the interaction with humans. The literature highlights that there is an increasing interest in ergonomics and robot application. In [58], Keshvarparast proposed a mathematical model for the design of human–robot collaborative workstations, considering ergonomics as a key factor in the design process. In [52], Cardoso presented a literature review that describes ergonomics as an input in the human–robot collaboration design, rather than as an output of the system.

The goal of introducing the robot to this workstation is to reduce the ergonomic load on the human operator during the work cycle.

Figure 1.

The four different scenarios described in the ISO 10218-1/2, image from [59].

Figure 1.

The four different scenarios described in the ISO 10218-1/2, image from [59].

4. Use Case: CHIMAR

CHIMAR S.p.a. (https://chimar.eu (accessed on 8 January 2025)) is a logistics company that manages the reception, classification, packaging, and transportation of goods. It uses integrated logistics services that are flexible, secure, and comprehensive. CHIMAR is a leading company in its field, specializing in integrated solutions for industrial logistics and packaging. Its headquarters is located at 175 Archimede Street, Limidi di Soliera (MO), Italy.

It is strategically positioned at the intersection of the Bologna Packaging Valley, the Modena Motor Valley, and the Carpi Textile District. This location offers a strong commercial and industrial advantage. The company’s customer-centric approach and the high quality of its products are the result of years of experience and a constant commitment to innovation. The CHIMAR Group, with its future-focused mindset, has continually developed new solutions to meet market needs, while preserving a strong artisanal approach.

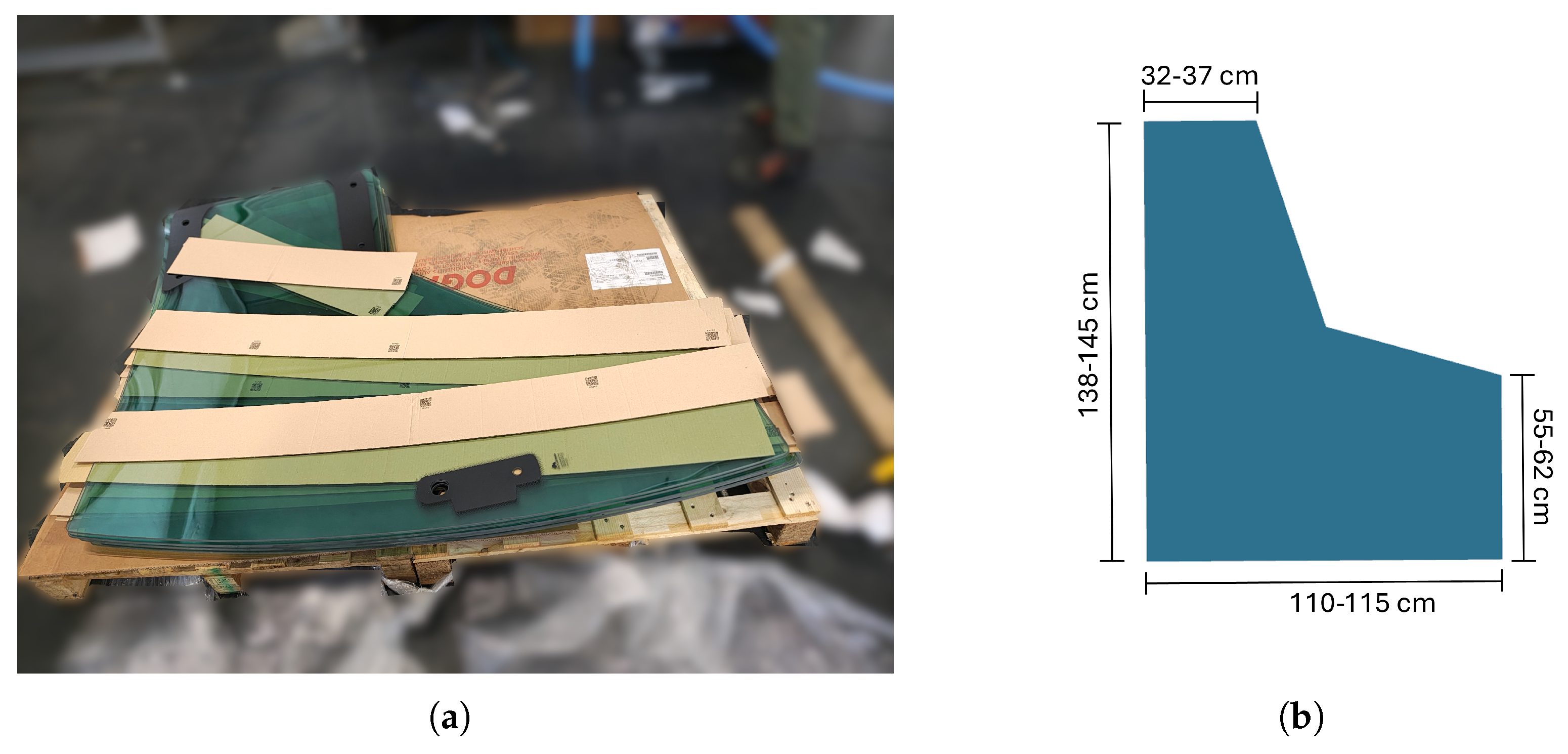

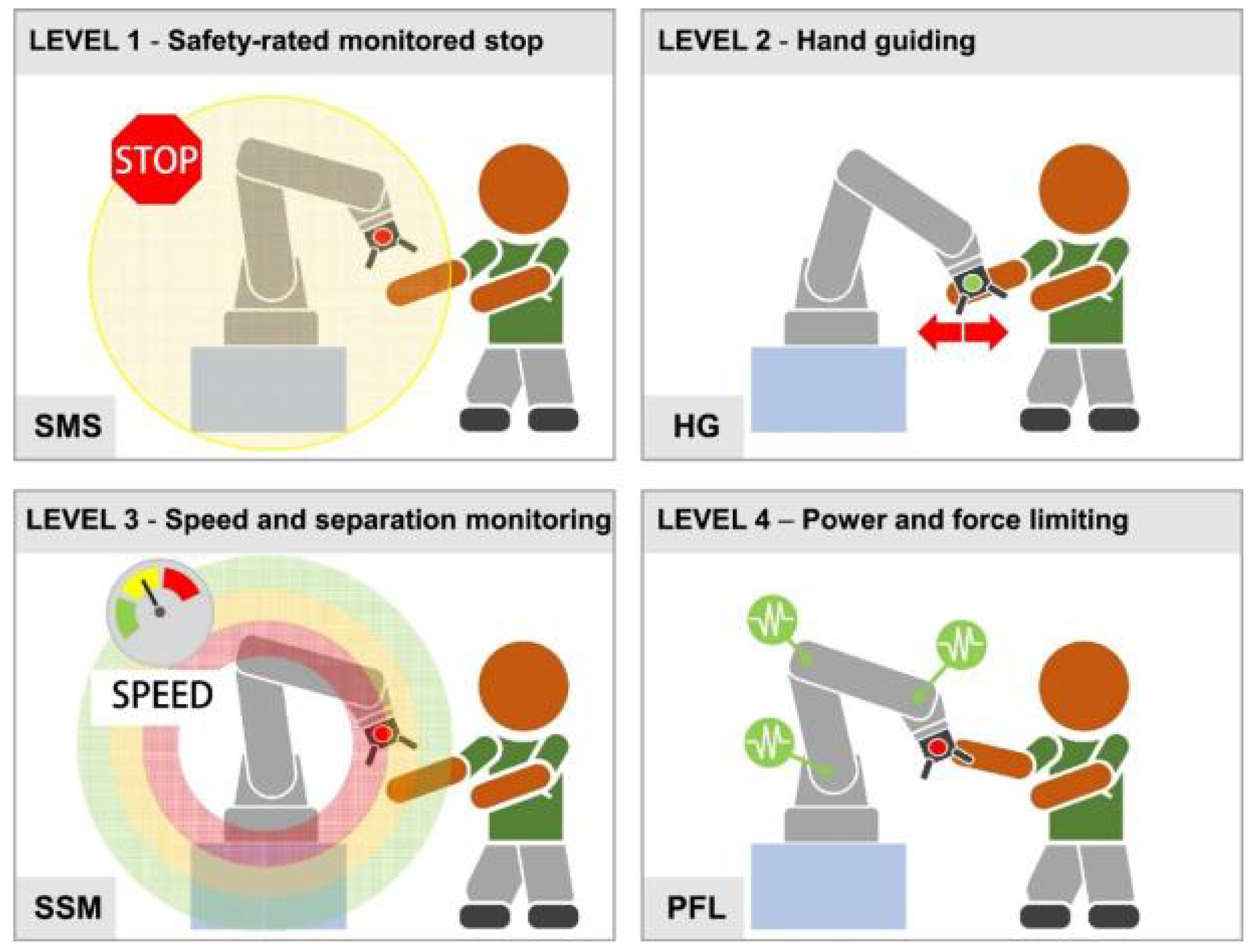

There are many workstations in the logistic site, and for this project, we concentrate on the windshield refinement workstation. The largest windshield picture is available in Figure 2a, while the rough windshield shape is in Figure 2b. It is not possible to provide the precise measurements of the windshield due to the confidentiality constraints regarding proprietary data from the client; for this reason, in Figure 2b, a range of measures are reported.

Figure 2.

Windshield. (a) Windshield picture. (b) Windshield representation used in the simulation.

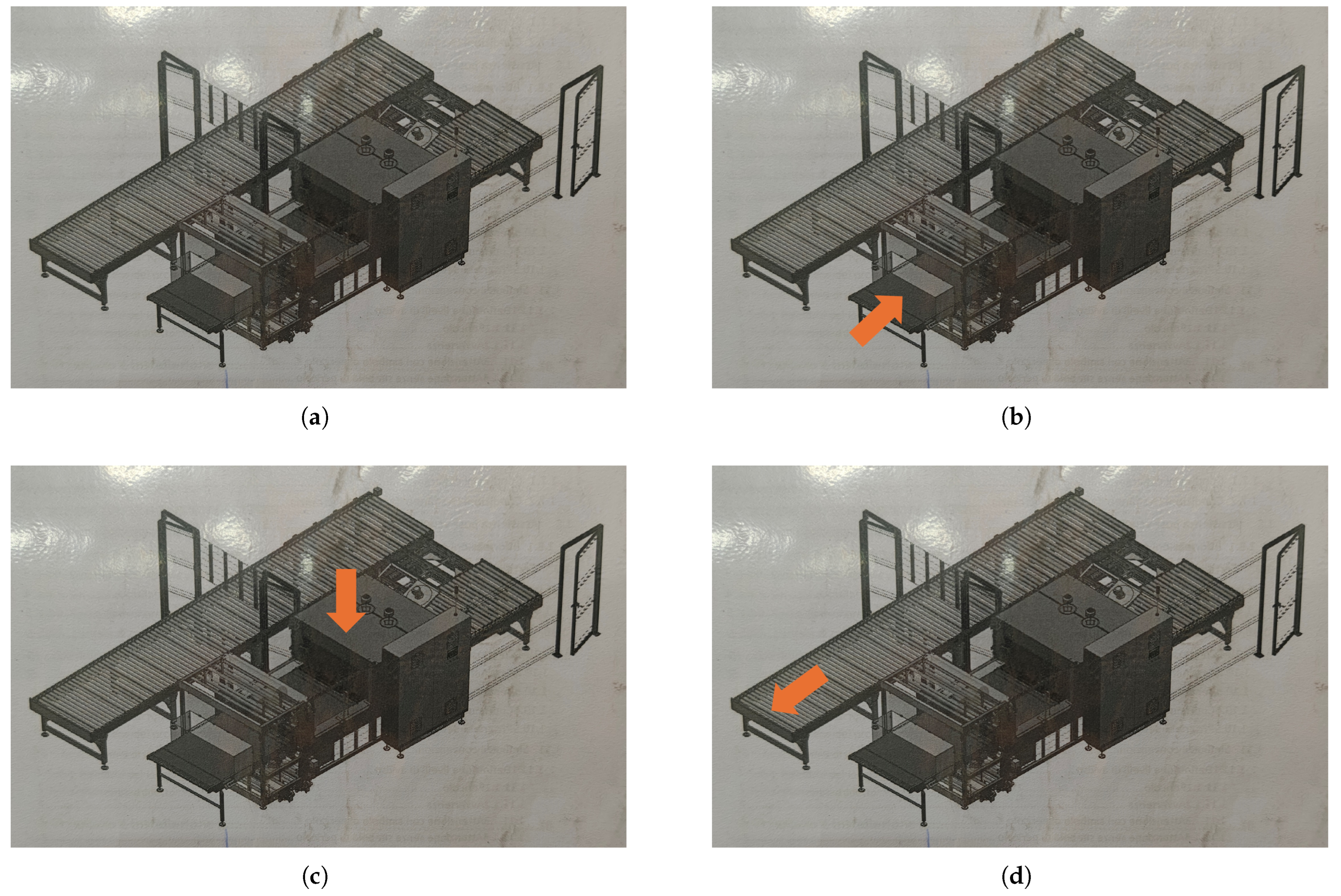

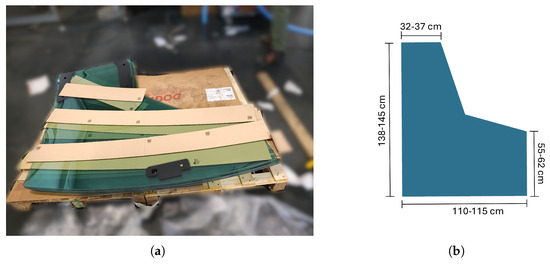

The workstation has a picking area, a packaging machine and a stocking area. In Figure 3a, the outbound area machine layout is reported. Figure 3b highlights the point where the product needs to be placed; then, the conveyor moves it in the packing machine (highlighted in Figure 3c). The conveyor then moves the processed product to the outbound area visible in Figure 3d.

Figure 3.

Packing machine. (a) Packing machine layout. (b) The arrow indicates the product position at the beginning. (c) The arrow indicates the packing machine position. (d) The arrow indicates the product position at the end.

The manual tasks performed on the windshields in this workstation are visible in Figure 4. The operator starts by lifting up the windshield from a pallet positioned at ground level (Figure 4a) and places it onto a suction-cup structure to hold it in place while applying the foam (Figure 4b). The foam is available at the operator’s station on a large spool.

Figure 4.

Windshield refinement workstation tasks. (a) The operator lifts up the windshield from the pallet. (b) The operator applies a protective foam border. (c) The operator wraps the windshield. (d) The operator puts the windshield onto the conveyor. (e) The operator lifts up the windshield from the conveyor. (f) The operator puts the windshield on a pallet.

The packing machine cannot package windshields of a large size, that is, the one reported in Figure 4, so in this case, the operator manually wraps the sides (Figure 4c) and then places the windshield on the conveyor (Figure 4d) to be finalized by the packaging machine. When the windshield is not the larger one, the manual wrapping step is skipped, and the operator directly places the windshield on the conveyor. At the end of the conveyor, the operator lifts the packed windshield (Figure 4e) and places it on a pallet (Figure 4f) for delivery.

In this workstation, there is one operator who performs the entire task and is able to finish around 120 windshields in an 8-h shift. The weights of the windshields vary between 16 and 23 kg.

5. Methodology Implementation

In this section, the methodology described in Section 3 is implemented in the defined workstations of the logistic plant described in Section 4.

5.1. Workstation Time Analysis

For the selected workstation, we decide to define the cycle time manually; these data are useful for ergonomic evaluation. To know the workstation’s cycle time, a video of the operator for the entire cycle is captured. Complementarily, the operator is wearing the Xsens sensors, and the task times are obtained by the video and verified thanks to the data acquisition of the MoCap system. The goal is to be able to conduct a time analysis and, as a second step, an ergonomic assessment, without affecting the production line and the scheduled order. It is very important in this situation to communicate with the operator, because he/she has to proceed as always, and not faster or slower than the usual performance. The activity times are collected from the video analysis and are reported in Table 1. For the primary purpose of this study, using a highly accurate time measurement tool is not necessary. The time analysis conducted provides all the essential information for the ergonomic evaluation.

Table 1.

Windshield workstation time analysis.

The tasks performed two times in the same cycle time have the same time as is visible in Table 1 because in this case the average time is considered. Normally, the operator prepares one windshield, and when it is in the packaging machine, the operator prepares a second windshield. Then, at this point, the first windshield is finished, and the operator moves it onto the pallet. Two windshields are considered together because some parts of the machine time overlap with the operator’s manual work.

The cycle time obtained is 448 s, which is the time used to process two different windshields and return at the beginning of the process, ready to proceed with a new windshield couple.

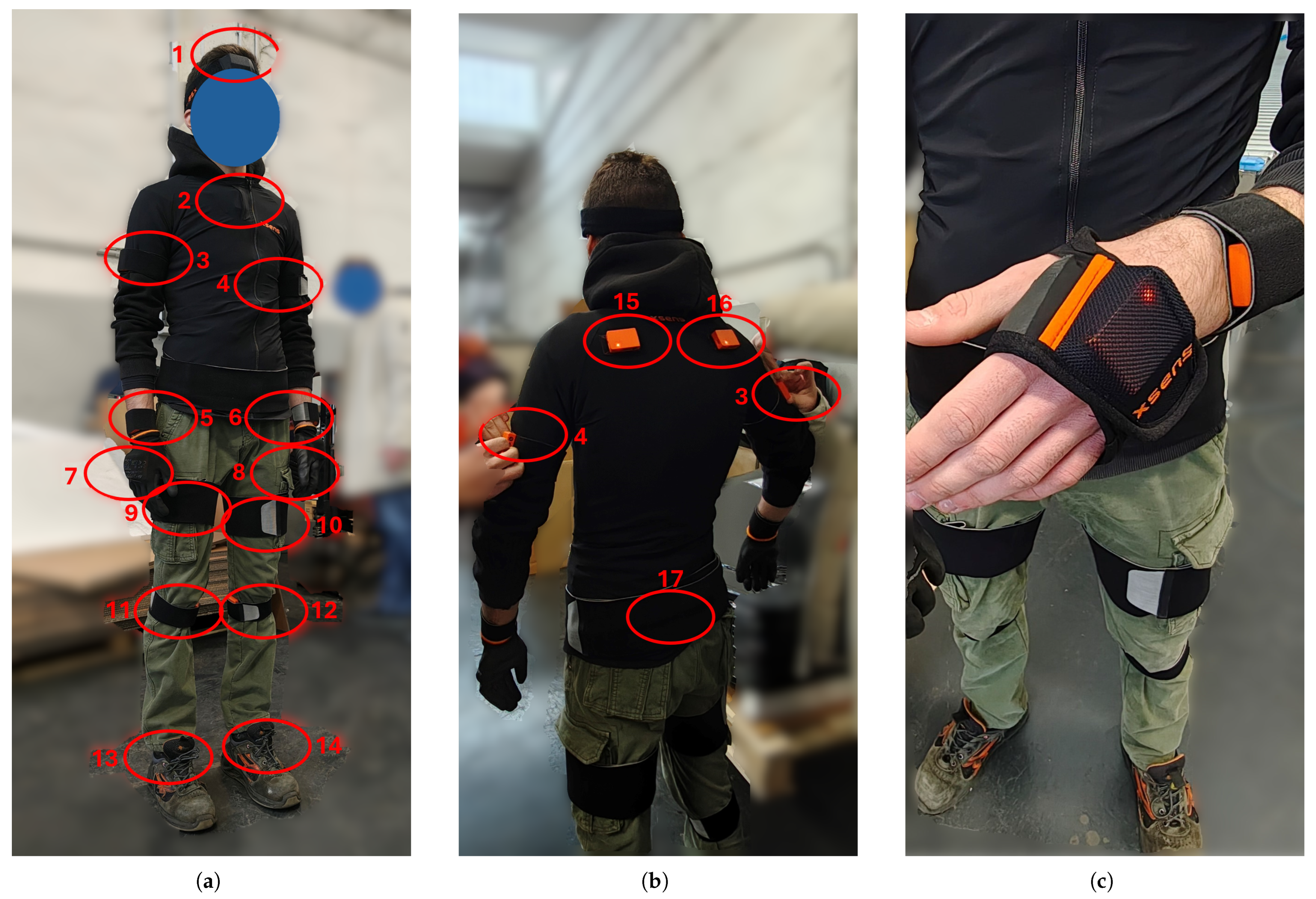

5.2. Workstation Motion Capturing Acquisition

Motion capture using the Xsens system is carried out at the CHIMAR facility for the selected workstations. Xsens is composed of 17 sensors that the operator wears. In Figure 5, it is possible to see the operator wearing the Xsens sensors. The Xsens sensors are located on the operator in precise positions.

Figure 5.

Operator wearing 17 Xsens sensors. (a) Front of the operator with the visible 14 Xsens sensors. (b) Back of the operator with the visible 5 Xsens sensors. (c) Detail on operator’s hand wearing Xsens sensor.

For each sensor labeled in Figure 5, its position is reported here:

- Sensor 1: head (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 2: neck (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 3: upper right arm (Figure 5a,b).

- Sensor 4: upper left arm (Figure 5a,b).

- Sensor 5: lower right arm (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 6: lower left arm (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 7: right hand (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 8: left hand (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 9: upper right leg (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 10: upper left leg (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 11: lower right leg (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 12: lower left leg (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 13: right foot (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 14: left foot (Figure 5a).

- Sensor 15: left shoulder (Figure 5b).

- Sensor 16: right shoulder (Figure 5b).

- Sensor 17: lower back (Figure 5b).

To wear sensor 1 on the head, the operator wears an elastic band that has an area where the sensor can be attached. An elastic band is also used for sensor 17 worn on the lower back. In Figure 5c, a detail is reported on the operator’s hand and elbow while wearing the sensors (elbows: sensors 5 and 6; hands: sensors 7 and 8); to not interfere with the operator’s mobility, a glove with a specific pocket for the sensor in the back of the hand is used, and the elbow’s sensor is fixed with a specific elastic band. A specific jacket is used for the sensors, to which sensors 3, 4, 15, and 16 can be attached, and it has a pocket specifically designed for sensor 2. Sensors 9, 10, 11, and 12 are applied using special elastic bands. Sensors 13 and 14 are secured in the shoes.

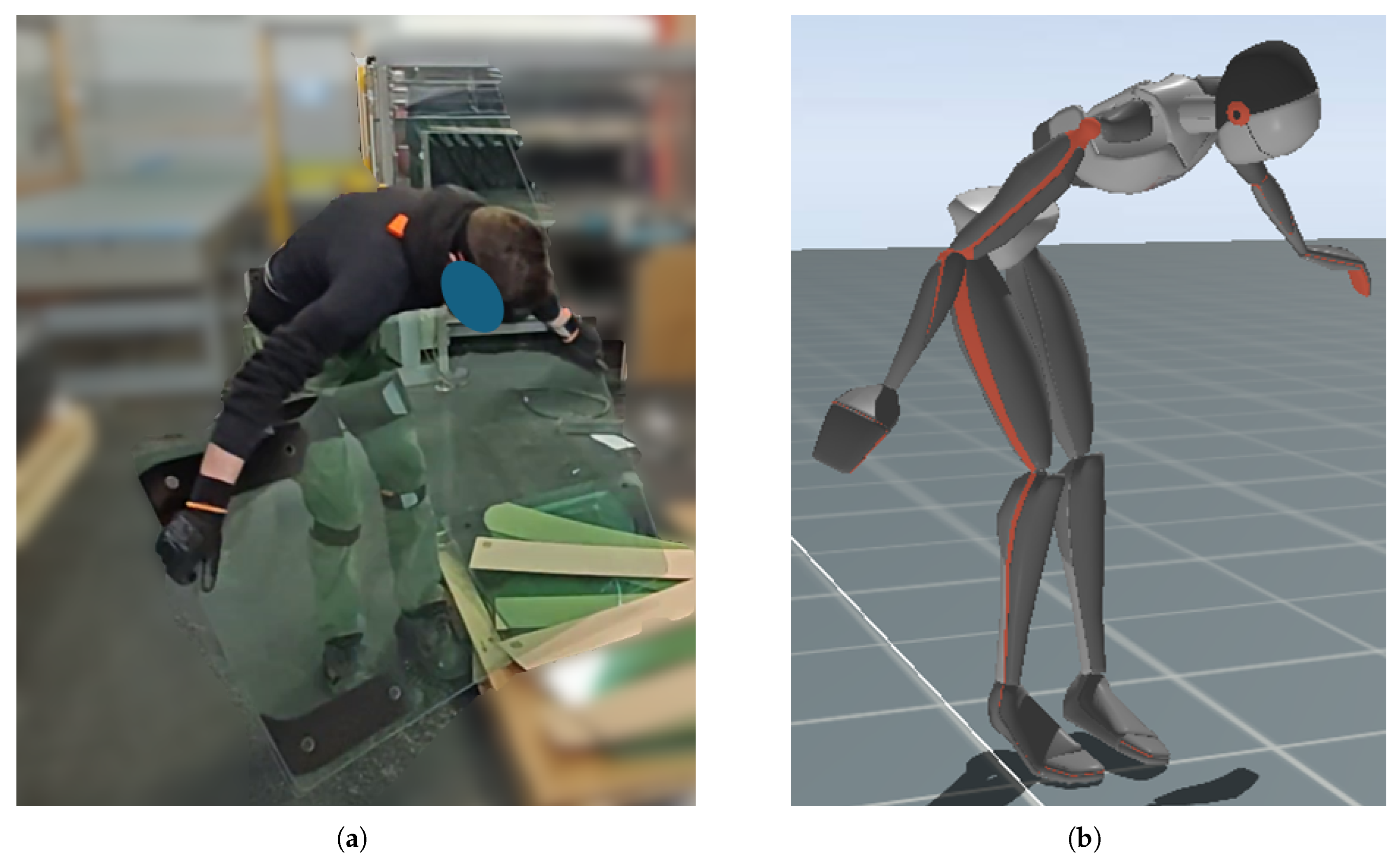

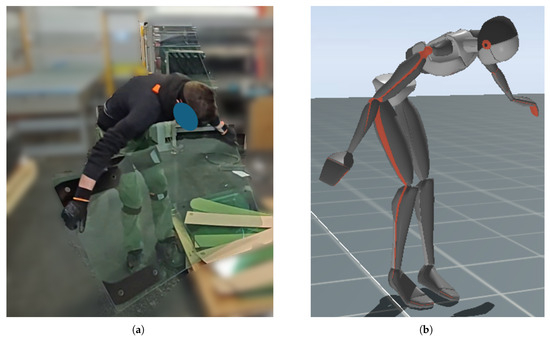

One worker is fitted with sensors and asked to perform his tasks as usual. As is visible in Figure 6, the Xsens does not majorly interfere with the operator’s mobility, and this is important because the collected data will be used to create a digital twin, allowing for an evaluation of the current conditions and the analysis of potential optimization scenarios. In Figure 6a, there is an image on the real operator while he is picking up the windshield, and in Figure 6b, there is the simulation of the same posture obtained with the Xsens sensors in the MVN software, version 2024.2.0.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the real operator and the simulated operator in the Xsens MVN software, version 2024.2.0. (a) Operator’s movement in the physical workstation activity. (b) MoCap’s movement on Xsens MVN software.

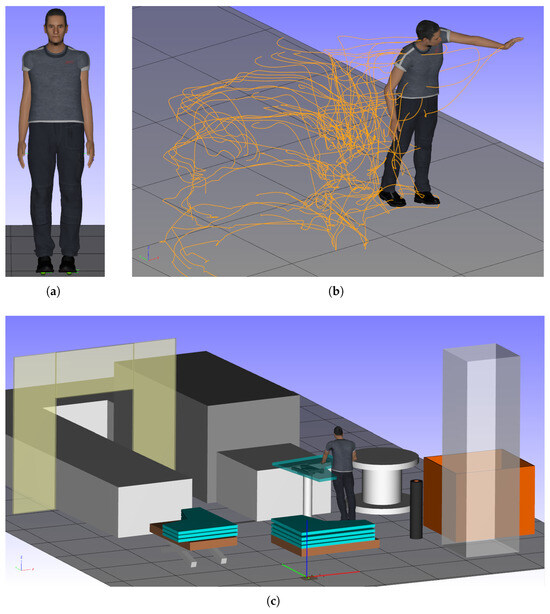

5.3. Workstation Digital Human Simulation (Digital Twin)

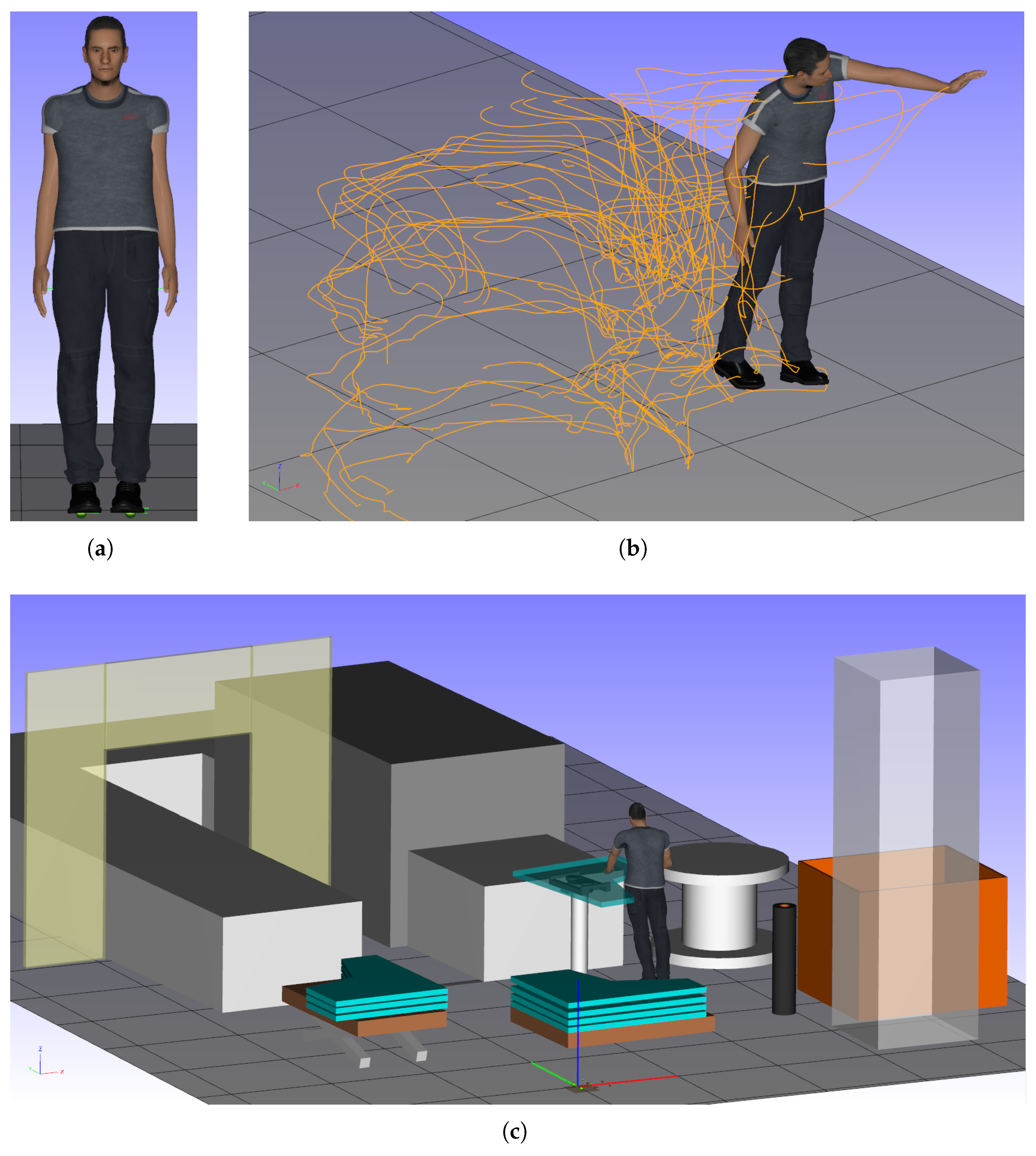

Once the MoCap data are obtained using the Xsense system, the IPS IMMA software is used to create the HDT of the As-Is scenario. As a first step, the workstation layout is created to have a virtual representation of the real workstation (Figure 7c). Since IPS IMMA is fully compatible with the Xsens system, the recorded motion is imported into the IPS IMMA scene containing the workstation layout. Consequently, the simulation of the real activity is created to understand the current situation of the workstation under study.

Figure 7.

Digital human simulation on IPS IMMA for the As-Is scenario. (a) Worker manikin. (b) Worker position trace in IPS IMMA. (c) As-Is scenario using the MoCap acquisition.

The manikin representing the worker is created using the information from Xsens to represent the real worker with its anthropometric dimensions reported in Figure 7a. The operator’s movements performed during the task and acquired thanks to the sensor are imported in the Xsens MVN software, with the aim to replicate the real movement in the DT for the As-Is scenario; some of the movements are visible in Figure 7b.

5.4. Workstation Ergonomic Evaluation

As mentioned above, improving worker well-being is one of the main goals of this study. That said, understanding the ergonomic risk of the As-Is scenario is important to determine the optimized solution. The ergonomic tool used to understand the workstation risk is the EAWS Whole-Body assessment that is already implemented in IPS IMMA. The EAWS assessment is performed using IPS IMMA on the digital human simulation already built with the MoCap data. To verify the correctness of the results, the ergonomic evaluation is also performed manually by a certified evaluator of the EAWS methodology. Thanks to the data collected with the MoCap application, the certified evaluator of the EAWS methodology is able to analyze the operator’s posture and the duration for which the operator maintains the same posture while moving the windshield.

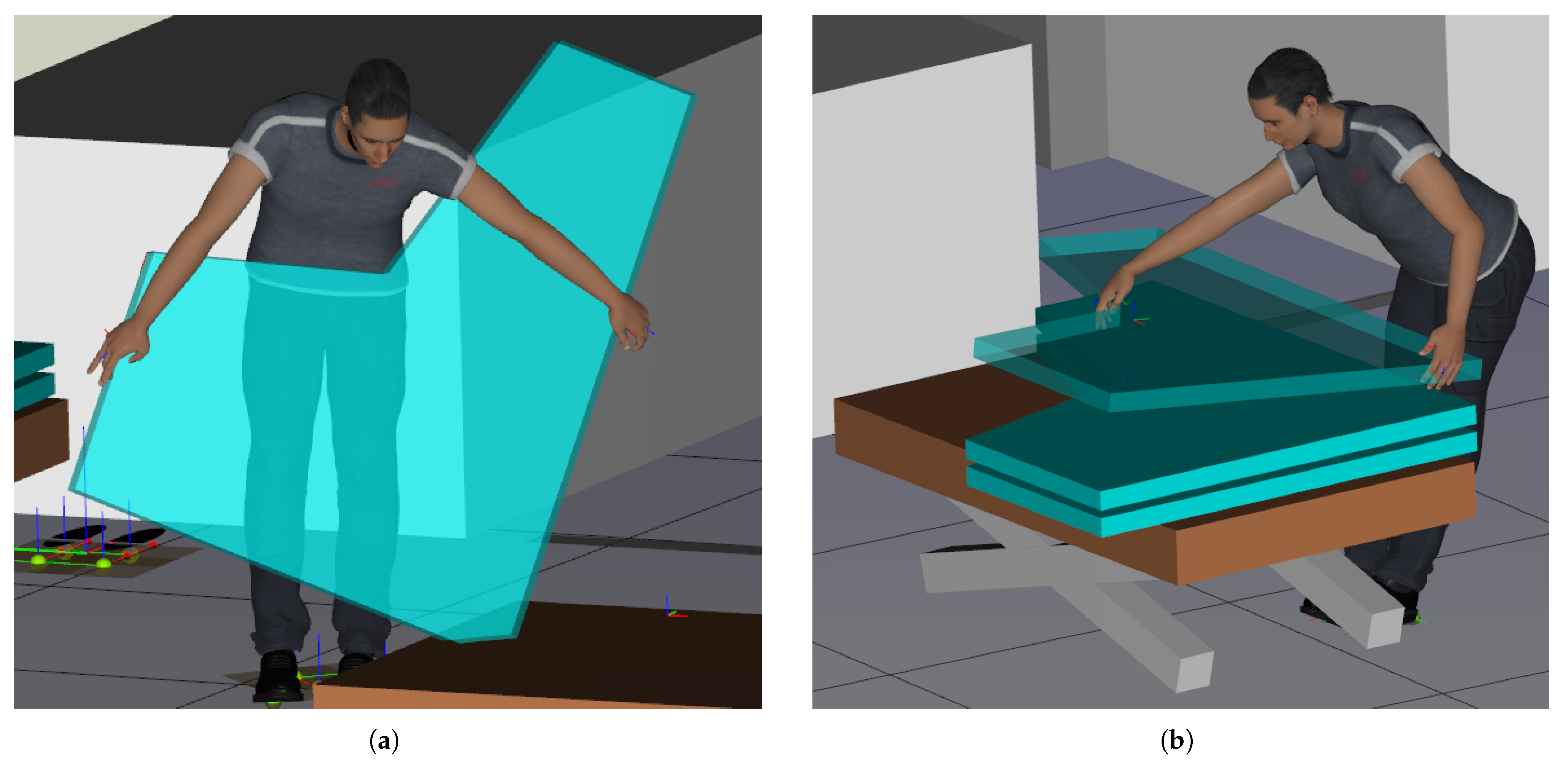

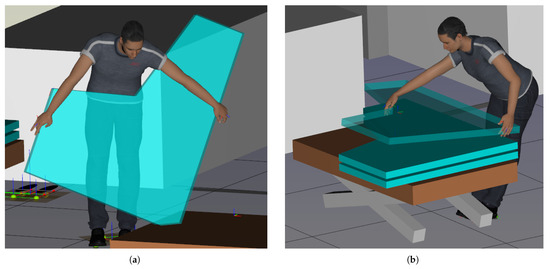

All activities performed by the operator during windshield packaging are carefully analyzed, with particular attention given to tasks involving static postures in awkward positions and heavy lifting, as these pose a risk of developing musculoskeletal disorders. The activity under study is composed of two types of activities, which are evaluated using the posture and manual material handling sections (windshield repositioning). The overall EAWS score shows that the activity has a medium-high risk level, which comes mainly from the windshield repositioning. The rest of the performed tasks do not represent a risk for the operator since there is no presence of static postures. The two worst activities from the ergonomic point of view are here reported: Figure 8a shows the picking posture when the worker picks the windshield from the raw material pallet, while Figure 8b represents the placement posture of the already processed windshield. The ergonomic analysis helps identify tasks that pose the highest risk to workers, allowing those tasks to be assigned to robots and reducing the risk of develop musculoskeletal disorders for workers.

Figure 8.

Manual material handling activity. (a) Windshield picking from raw material pallet. (b) Windshield placement on the pallet for dispatch.

5.5. Collaborative Robot Application in the Workstation

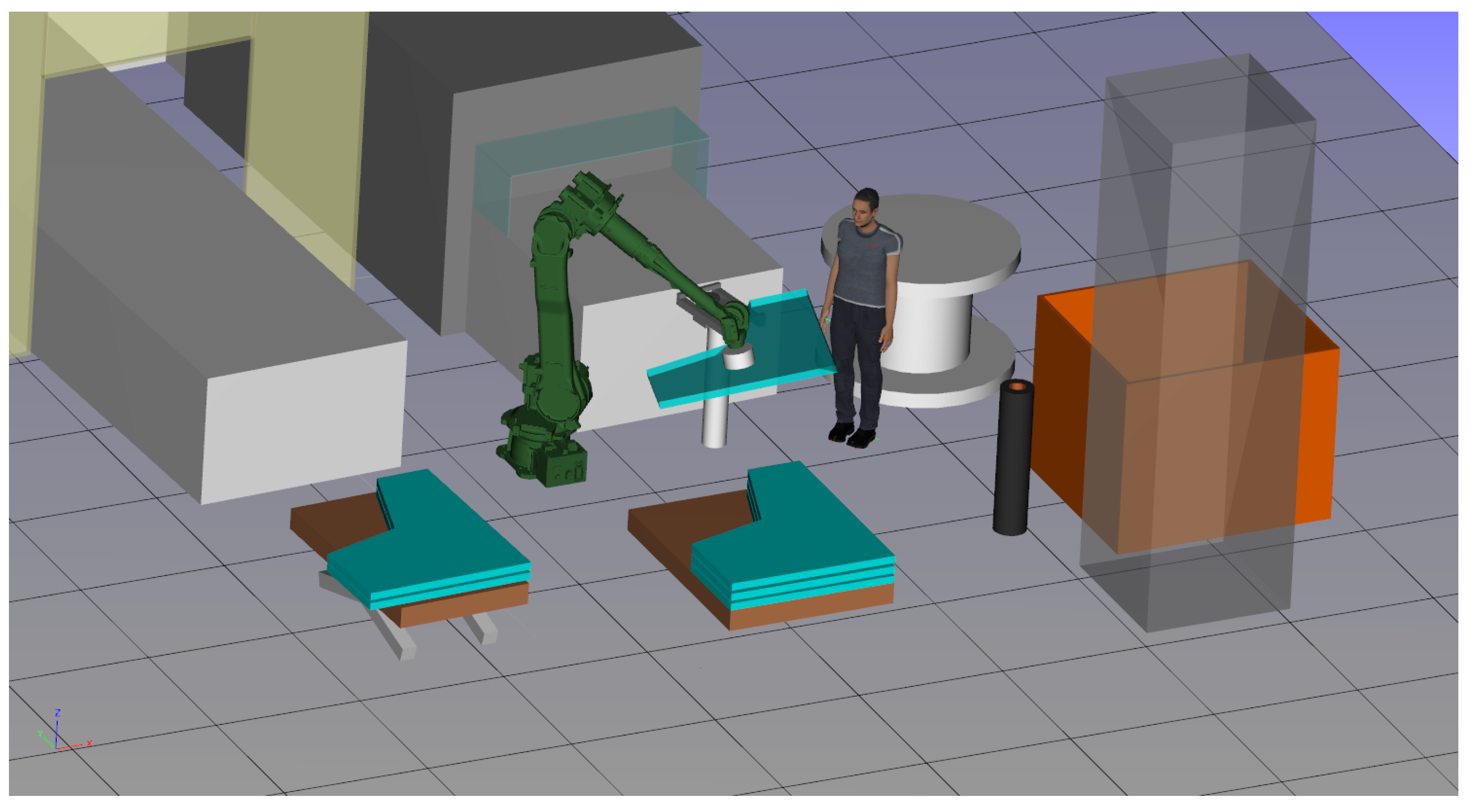

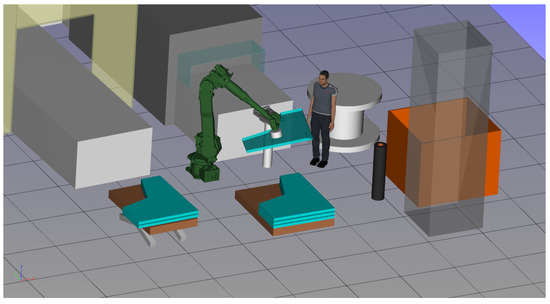

Since the primary risk stems from the two manual material handling activities involved in the task, the optimization solution introduces a collaborative robot (Figure 9). This approach will both reduce the ergonomic load on the human operator and increase the productivity (reduction in the cycle time).

Figure 9.

Optimized solution, human–robot collaboration.

The cobot is equipped with a suction-cup gripping device that can handle cardboard packages weighing up to 25 kg, provided that they have a flat area on which the suction cup can grip. To optimize cycle time and reduce ergonomic risk, a detailed analysis of task distribution between the worker and the robot is conducted.

To ensure proper functioning in the workplace, we determine that a robot with a reach of at least 2500 mm and a payload capacity exceeding 35 kg is required. Therefore, we select a robot with these characteristics and conduct all experiments to assess its suitability for the task. Our findings demonstrate that a collaborative robot with similar capabilities would be well suited for this application.

It is positioned in the workspace so that it can reach all critical points required for each task without interfering with the operator. This setup can be classified under Speed and Separation Monitoring (SSM) since the operator does not come into direct contact with the active robot but works near it.

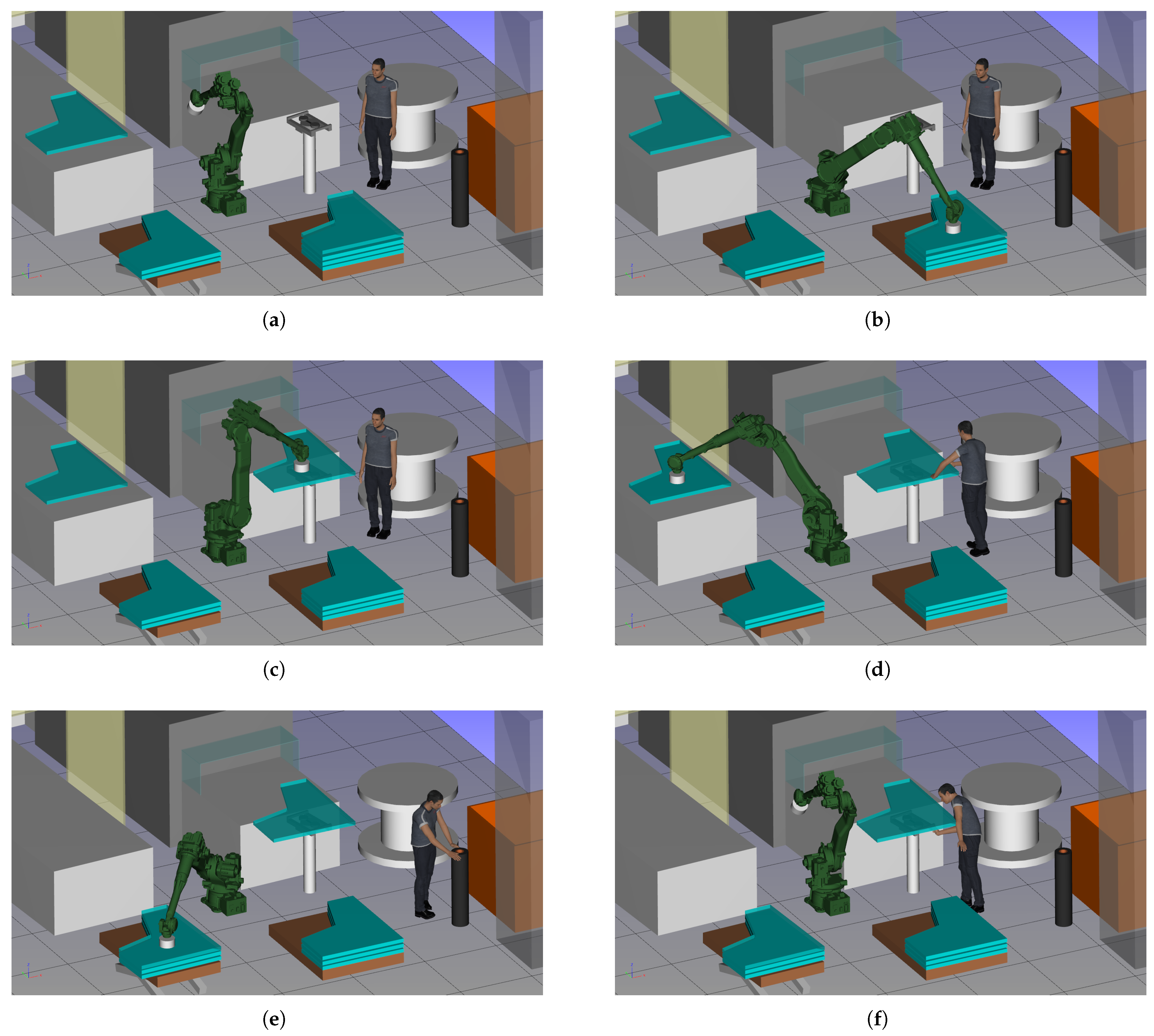

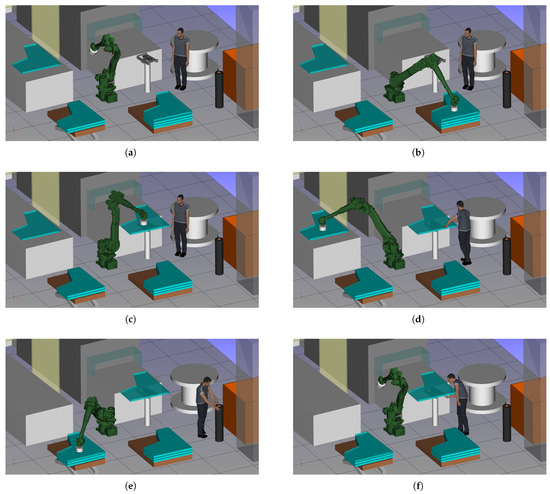

A simple approach is chosen to control the robot’s speed: whenever the robot operates near the human (the “yellow zone” in Figure 1), its speed is reduced by 50%. This reduction is based on SSM norms, which define three operational zones (in Figure 1): green (operator at a safe distance), yellow (operator nearby but not in immediate proximity), and red (operator very close). Accordingly, the robot adjusts its speed from 100% (green) to 50% (yellow) and finally to 0% (red). Rather than being determined by a fixed distance, these zones are defined based on the robot’s current task location. For instance, when the robot picks up the windshield from the raw material pallet (Figure 10b) and places it onto the suction-cup structure (Figure 10c), it operates in the presence of the operator, requiring a speed reduction to 50% (yellow zone). Once the worker begins applying the foam and manually wrapping the plastic (Figure 10d), the robot simultaneously picks up the previously finished windshield and places it on the pallet for dispatch (Figure 10e). As this occurs away from the operator, it is classified as a green zone, allowing the robot to operate at full speed. After completing the manual work, the operator pushes the windshield onto the conveyor (Figure 10f), allowing the robot to retrieve the next windshield for processing.

Figure 10.

Task allocation between worker and robot (cobot simulation). (a) Initial state. (b) Windshield picking from the raw material pallet by the robot. (c) Windshield placement on the suction-cup structure by the robot. (d) Previously finished windshield picking by the robot and manual work by the worker. (e) Previously finished windshield placement by the robot and manual work by the worker. (f) Completion of manual work by the worker and robot in home position waiting for the next windshield picking.

The speed reduction does not impact the overall process efficiency, as the robot operates predominately within the masked time—meaning that increasing its speed would not shorten the cycle time, given that the operator is already working at full capacity. Future improvements could consider deploying a mobile robot capable of serving multiple workstations simultaneously; however, this is currently infeasible due to layout constraints.

The robot implemented is not in substitution of the operator because the implementation wants to obtain a system where humans and robots collaborate, where the robot performs high-load activities. In particular, this work considers the ergonomic risk as the principal factor in the system evaluation. The tasks reported in Table 1 are divided between the operator and the robot. In the simulated scenario, the robot’s tasks are as follows:

The operator’s tasks are as follows:

To optimize the system, the robot picks up the packed windshield while the operator applies the foam or wraps the windshield with plastic. The analyzed windshield is the worst model in terms of dimensions and weight; for this reason, other windshields can be used and considered in the same scenario.

6. Results

To analyze effectively how the new system works, some Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are defined. The KPIs measure how effectively human–robot teams perform tasks and contribute to overall productivity. The assessment is evaluated in terms of the following:

- Cycle time reduction.

- Ergonomic evaluation reduction.

- Robot simulation.

6.1. Cycle Time

The optimization solution shows a reduction in the cycle time. Allowing the robot to perform the activities that represent a high load for the worker results in a 24% reduction of the cycle time, passing from 448 s to 341 s. This reduction is also reflected in the number of windshields that the worker can process during the working shift, passing from 121 units to 158. This shows an increment of 31% in productivity.

6.2. Ergonomic Evaluation

As mentioned above, the ergonomic risk primarily arises from the repositioning of the windshield, which occurs twice during the cycle time. To enhance worker well-being, the optimization aims to assign these repositioning tasks to the robot, allowing the worker to focus on low-load activities.

The simulation of the optimized solution demonstrates a significant reduction in ergonomic risk, lowering it from a medium-high risk level to a low risk level. By delegating high-load tasks to the robot, workers experience reduced fatigue, which can also lead to increased productivity. However, this productivity boost cannot be precisely quantified until the optimization is implemented, as it depends largely on worker performance. Additionally, as previously mentioned, high-risk activities increase the likelihood of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and related absenteeism. The optimized scenario is expected to reduce both the probability of MSDs and the number of absence days, as it involves low-risk tasks for workers. Finally, since the manual tasks remaining in this workstation involve a lower physical load, the environment becomes more inclusive. This allows a wider range of workers, including women and older employees, to perform the task effectively.

6.3. Robot Simulation

The simulation performed with IPS Robotics determines the optimal position for the robot to meet cobot constraints while ensuring reachability to the windshield’s pick-and-place locations. The SSM setup is also verified, confirming that the manikin is positioned near the robot when placing the windshield onto the suction-cup structure without any direct interference. Additionally, the robot’s maximum joint velocity remains below 50% throughout the entire activity, ensuring worker safety and minimizing wear, which reduces maintenance costs. The packing machine’s velocity is adjusted based on worker performance, as 85% of the cycle time involves manual work. Consequently, the processed windshield will be ready for the robot to pick up once the next unprocessed windshield has been placed in the suction-cup structure.

7. Conclusions

This paper presents a methodology for improving an existing workstation using a human-centered design approach in the industrial logistics sector. The implementation incorporates various technologies, such as DHM software IPS IMMA and a MoCap system, to create a digital twin of the current scenario. Additionally, an optimization solution is proposed by introducing a cobot to handle high-load tasks.

The methodology presented is validated with the defined KPIs, which allows determining the benefits and improvements of the optimization solution in terms of productivity and ergonomics of the workplace. This solution shows a significant reduction in cycle time, increasing the productivity of the system. Regarding ergonomic risk, a significant decrease is observed, going from a medium-high risk level to a low risk level, improving the operator’s well-being.

For future developments, a physical validation of the optimized solution should be performed to verify the results obtained from the virtual simulation. The virtual simulation has the goal of validating the procedure and identifying a possible solution, but only with a physical application can it be possible to evaluate the real new cycle time obtained and to evaluate how to optimize the workstation. This validation should assess not only productivity but also the worker’s perspective, as they will be collaborating with a robot. Additionally, further optimizations can be explored using additional KPIs related to cobot interactions, such as task completion time and utilization rate. In addition, the impact of these changes on corporate costs, long-term operational benefits, and other critical aspects should be considered after the physical application in the workstation and its optimization.

In the future, it could be interesting to evaluate a system where different categories of objects can be picked up, such as heavy cardboard boxes, and not only windshields. For this possible solution, it should be considered whether the suction cup is the suitable solution, or if a different tool should be used.

Furthermore, it would be interesting to evaluate this procedure in a different workstation with different constraints in order to validate the procedure and address any potential weakness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and M.V.; methodology, A.B.; software, M.V., L.R., P.P. and M.N.; validation, A.B., M.V., L.R. and P.P.; formal analysis, A.B., M.V., L.R. and P.P.; investigation, V.C., L.B., A.N. and C.F.; resources, A.N. and L.B.; data curation, A.B., M.V. and L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., M.V. and M.N.; supervision, V.C., L.B. and C.F.; project administration, V.C.; funding acquisition, V.C., L.B. and C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MICS (Made in Italy—Circular and Sustainable) Extended Partnership and received funding from Next-Generation EU (Italian PNRR—M4 C2, Invest 1.3, PE00000004) CUP MICS D43C22003120001, project title “SOSTELOGICA—Ambienti di Lavoro SOSTEnibili ed Inclusivi per la LOGIstiCa del Settore dell’Abbigliamento e dell’Oggettistica”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this article, the authors used ChatGPT/GPT-4 and Grammarly for the purposes of text editing to improve the English (e.g., grammar, structure, spelling, punctuation, and formatting). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Valerio Cibrario, Manuela Vargas, Paolo Perona, Ludovico Rossi were employed by the company (Flexstructures Italia srl), and Laura Benedetti, Alberto Nicolinti were employed by the company (Chimar spa). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Golovianko, M.; Terziyan, V.; Branytskyi, V.; Malyk, D. Industry 4.0 vs. Industry 5.0: Co-existence, transition, or a hybrid. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A. Future of industry 5.0 in society: Human-centric solutions, challenges and prospective research areas. J. Cloud Comput. 2022, 11, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Ziatdinov, R.; Atteraya, M.S.; Nabiyev, R. The Fifth Industrial Revolution as a transformative step towards society 5.0. Societies 2024, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Sha, W.; Wang, B.; Zheng, P.; Zhuang, C.; Liu, Q.; Wuest, T.; Mourtzis, D.; Wang, L. Industry 5.0: Prospect and retrospect. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 65, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar]

- Raja Santhi, A.; Muthuswamy, P. Industry 5.0 or industry 4.0 S? Introduction to industry 4.0 and a peek into the prospective industry 5.0 technologies. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 17, 947–979. [Google Scholar]

- Rybnikár, F.; Kačerová, I.; Hořejší, P.; Šimon, M. Ergonomics evaluation using motion capture technology—Literature review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loske, D.; Klumpp, M.; Keil, M.; Neukirchen, T. Logistics Work, ergonomics and social sustainability: Empirical musculoskeletal system strain assessment in retail intralogistics. Logistics 2021, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trstenjak, M.; Đukić, G.; Opetuk, T. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Logistics Activities by Principles of Industry 5.0. In Proceedings of the 1st Jordanian Conference on Logistics in the Mashreq Region (JCLM1), Amman, Jordan, 12–14 November 2023; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Cristaldi, L.; Esmaili, P.; Gruosso, G.; La Bella, A.; Mecella, M.; Scattolini, R.; Arman, A.; Susto, G.A.; Tanca, L. The MICS Project: A Data Science Pipeline for Industry 4.0 Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), Milan, Italy, 25–27 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, N.; Arman, A.; Esmaili, P.; Zeynivand, M.; Battini, D.; Bianchini, D.; Cristaldi, L.; De Giuli, L.B.; Galeazzo, A.; Gruosso, G.; et al. Sustainability and Resilience in the MICS SPOKE8 project: The role of the Digital Twin. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for eXtended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), Naples, Italy, 29–31 October 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 669–673. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar, V.; Sgarbossa, F.; Neumann, W.P.; Sobhani, A. Framework for incorporating human factors into production and logistics systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluchak, T.J. Ergonomics: Origins, focus, and implementation considerations. AAOHN J. 1992, 40, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimie, S.I.; Irimie, S. Ergonomy and the ergonomist. historical and current references. Acta Tech. Napoc. Ser. Appl. Math. Mech. Eng. 2021, 64, 1232. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini, M.; Botti, L.; Galizia, F.G.; Mora, C. Ergonomic Design of an Adaptive Automation Assembly System. Machines 2023, 11, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, S.; Vyavahare, R. An ergonomic evaluation of an industrial workstation: A review. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 2015, 5, 1820–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Zen, Z.H.; Widia, M.; Sukadarin, E.H. Ergonomics Risk Assessment Tools: A Systematic Review. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2024, 20, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berguer, R. The application of ergonomics in the work environment of general surgeons. Rev. Environ. Health 1997, 12, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, I.; do Carmo Fernandes, M.; Cepeda, C.; Quaresma, C.; Gamboa, H.; Nunes, I.L.; Gabriel, A.T. Application of wearable technology for the ergonomic risk assessment of healthcare professionals: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2024, 100, 103570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeini, H.S.; Karuppiah, K.; Tamrin, S.B.; Dalal, K. Ergonomics in agriculture: An approach in prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs). J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2014, 3, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Loos, M.J.; Merino, E.; Rodriguez, C.M.T. Mapping the state of the art of ergonomics within logistics. Scientometrics 2016, 109, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanain, B. The Role of Ergonomic and Human Factors in Sustainable Manufacturing: A Review. Machines 2024, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgarbossa, F.; Grosse, E.H.; Neumann, W.P.; Battini, D.; Glock, C.H. Human factors in production and logistics systems of the future. Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 49, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zülch, M.; Zülch, G. Production logistics and ergonomic evaluation of U-shaped assembly systems. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 190, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mocan, A.; Draghici, A. Reducing ergonomic strain in warehouse logistics operations by using wearable computers. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2018, 238, 1822–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajewski, D.; Górski, F.; Zawadzki, P.; Hamrol, A. Application of virtual reality techniques in design of ergonomic manufacturing workplaces. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 25, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battini, D.; Berti, N.; Finco, S.; Guidolin, M.; Reggiani, M.; Tagliapietra, L. WEM-Platform: A real-time platform for full-body ergonomic assessment and feedback in manufacturing and logistics systems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 164, 107881. [Google Scholar]

- Brosche, J.; Wackerle, H.; Augat, P.; Lödding, H. Individualized workplace ergonomics using motion capture. Appl. Ergon. 2024, 114, 104140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, R.; Jesus, C.; Lopes, S.I. Implementations of Digital Transformation and Digital Twins: Exploring the Factory of the Future. Processes 2024, 12, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trstenjak, M.; Benešova, A.; Opetuk, T.; Cajner, H. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Industry 5.0—A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Peng, T.; Zhang, X.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tang, R. From digital human modeling to human digital twin: Framework and perspectives in human factors. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujica-Herzog, N.; Buchmeister, B.; Breznik, M. Ergonomics, digital twins and time measurements for optimal workplace design. Hum. Factors Simul. 2022, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baratta, A.; Cimino, A.; Longo, F.; Nicoletti, L. Digital twin for human-robot collaboration enhancement in manufacturing systems: Literature review and direction for future developments. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 187, 109764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakis, N.; Siaterlis, G.; Bampoula, X.; Papadopoulos, I.; Tsoukaladelis, T.; Alexopoulos, K. A digital twin-enabled cyber-physical system approach for mixed packaging. In SPS2022; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Ramasubramanian, A.K.; Mathew, R.; Kelly, M.; Hargaden, V.; Papakostas, N. Digital twin for human–robot collaboration in manufacturing: Review and outlook. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilberg, A.; Malik, A.A. Digital twin driven human–robot collaborative assembly. Cirp Ann. 2019, 68, 499–502. [Google Scholar]

- Menolotto, M.; Komaris, D.S.; Tedesco, S.; O’Flynn, B.; Walsh, M. Motion capture technology in industrial applications: A systematic review. Sensors 2020, 20, 5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, S.; Ruhaiyem, N.I.R.; Eisa, T.A.E.; Nasser, M.; Saeed, F.; Younis, H.A. Motion Capture Technologies for Ergonomics: A Systematic Literature Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosyan, T.; Dunoyan, A.; Mkrtchyan, H. Application of motion capture systems in ergonomic analysis. Armen. J. Spec. Educ. 2020, 4, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Xiao, B.; Qi, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ji, P. Digital twin modeling. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 372–389. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, J.B.; Zafarzadeh, M.; Jeong, Y.; Li, Y.; Khilji, W.A.; Wiktorsson, M. Employing digital twins within production logistics. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Cardiff, UK, 15–17 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, N.; Finco, S. Digital twin and human factors in manufacturing and logistics systems: State of the art and future research directions. IFAC PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, L.; Ali, A.; Nugent, C.; Cleland, I.; Li, R.; Ding, J.; Ning, H. Human digital twin: A survey. J. Cloud Comput. 2024, 13, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Yang, G.; Zheng, P.; Song, C.; Yuan, Y.; Wuest, T.; Yang, H.; Wang, L. Human Digital Twin in the context of Industry 5.0. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 85, 102626. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, F.; Greco, A.; Fera, M.; Macchiaroli, R. Digital twins to enhance the integration of ergonomics in the workplace design. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2019, 71, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama, T.; Ueshiba, T.; Tada, M.; Toda, H.; Endo, Y.; Domae, Y.; Nakabo, Y.; Mori, T.; Suita, K. Digital twin-driven human robot collaboration using a digital human. Sensors 2021, 21, 8266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibrario, V.; Vargas, M.; Fantuzzi, C.; Cavatorta, M.P.; Bagalà, A.N.; Bosani, E.; Dengel, D.; Schaub, M.; Delfs, N.; Fagerlind, E.; et al. Assessing ergonomics on cobot for an optimized integrated solution in early phase of product and process design. In Digital Human Modeling and Applied Optimization; AHFE Open Access: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 76, pp. 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brolin, E.; Högberg, D.; Hanson, L. Design of a Digital Human Modelling Module for Consideration of Anthropometric Diversity; AHFE Open Access: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tee, K.S.; Low, E.; Saim, H.; Zakaria, W.N.W.; Khialdin, S.B.M.; Isa, H.; Awad, M.; Soon, C.F. A study on the ergonomic assessment in the workplace. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical and Electronic Engineering 2017 (IC3E 2017), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 9–11 August 2017; AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub, K.G.; Mühlstedt, J.; Illmann, B.; Bauer, S.; Fritzsche, L.; Wagner, T.; Bullinger-Hoffmann, A.C.; Bruder, R. Ergonomic assessment of automotive assembly tasks with digital human modelling and the ‘ergonomics assessment worksheet’ (EAWS). Int. J. Hum. Factors Model. Simul. 2012, 3, 398–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zaatari, S.; Marei, M.; Li, W.; Usman, Z. Cobot programming for collaborative industrial tasks: An overview. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 116, 162–180. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, A.; Colim, A.; Bicho, E.; Braga, A.C.; Menozzi, M.; Arezes, P. Ergonomics and human factors as a requirement to implement safer collaborative robotic workstations: A literature review. Safety 2021, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taesi, C.; Aggogeri, F.; Pellegrini, N. COBOT applications—Recent advances and challenges. Robotics 2023, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10218-1:2011(E); Robots and Robotic Devices—Safety Requirements for Industrial Robots—Part 1: Robots. ISO Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ISO 10218-2:2011(E); Robots and Robotic Devices–Safety Requirements for Industrial Robots—Part 2: Robot Systems and Integration. ISO Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Wannasuphoprasit, W.; Gillespie, R.B.; Colgate, J.E.; Peshkin, M.A. Cobot control. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 20–25 April 1997; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 4, pp. 3571–3576. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzini, M.; Lagomarsino, M.; Fortini, L.; Gholami, S.; Ajoudani, A. Ergonomic human-robot collaboration in industry: A review. Front. Robot. AI 2023, 9, 813907. [Google Scholar]

- Keshvarparast, A.; Berti, N.; Chand, S.; Guidolin, M.; Lu, Y.; Battaia, O.; Xu, X.; Battini, D. Ergonomic design of Human-Robot collaborative workstation in the Era of Industry 5.0. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 198, 110729. [Google Scholar]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Karimi Ghaleh Jough, F. Intelligent Robotic Systems in Industry 4.0, A Review. J. Adv. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 2024007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).