A Weighted Control Strategy Based on Current Imbalance Degree for Vienna Rectifiers Under Unbalanced Grid

Abstract

1. Introduction

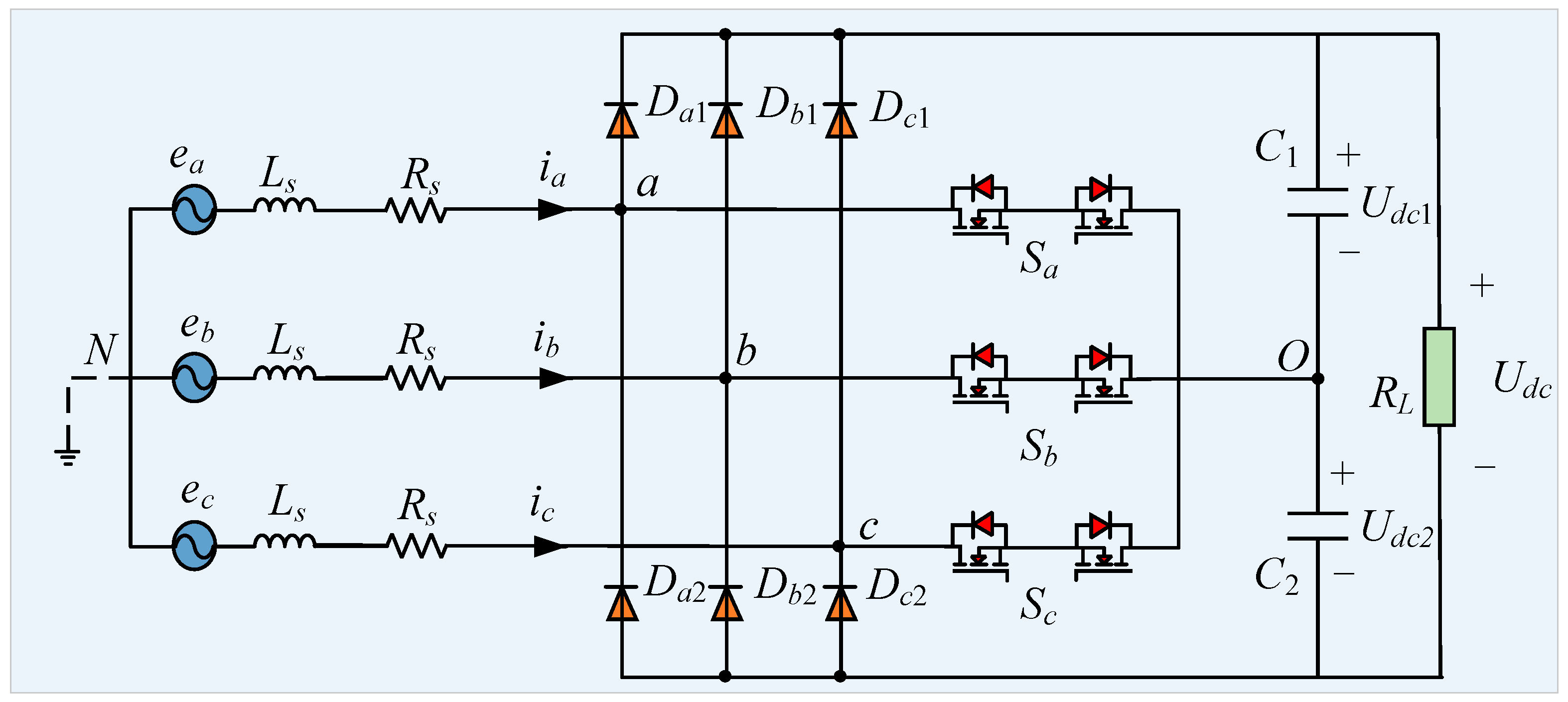

2. Mathematical Modeling of Vienna Rectifier

3. Control Methods Under Unbalanced Grid

3.1. The Symmetrical Control of Input Current

3.2. The Suppression of Voltage Fluctuations in Dc-Link

4. Implementation of the Proposed Method

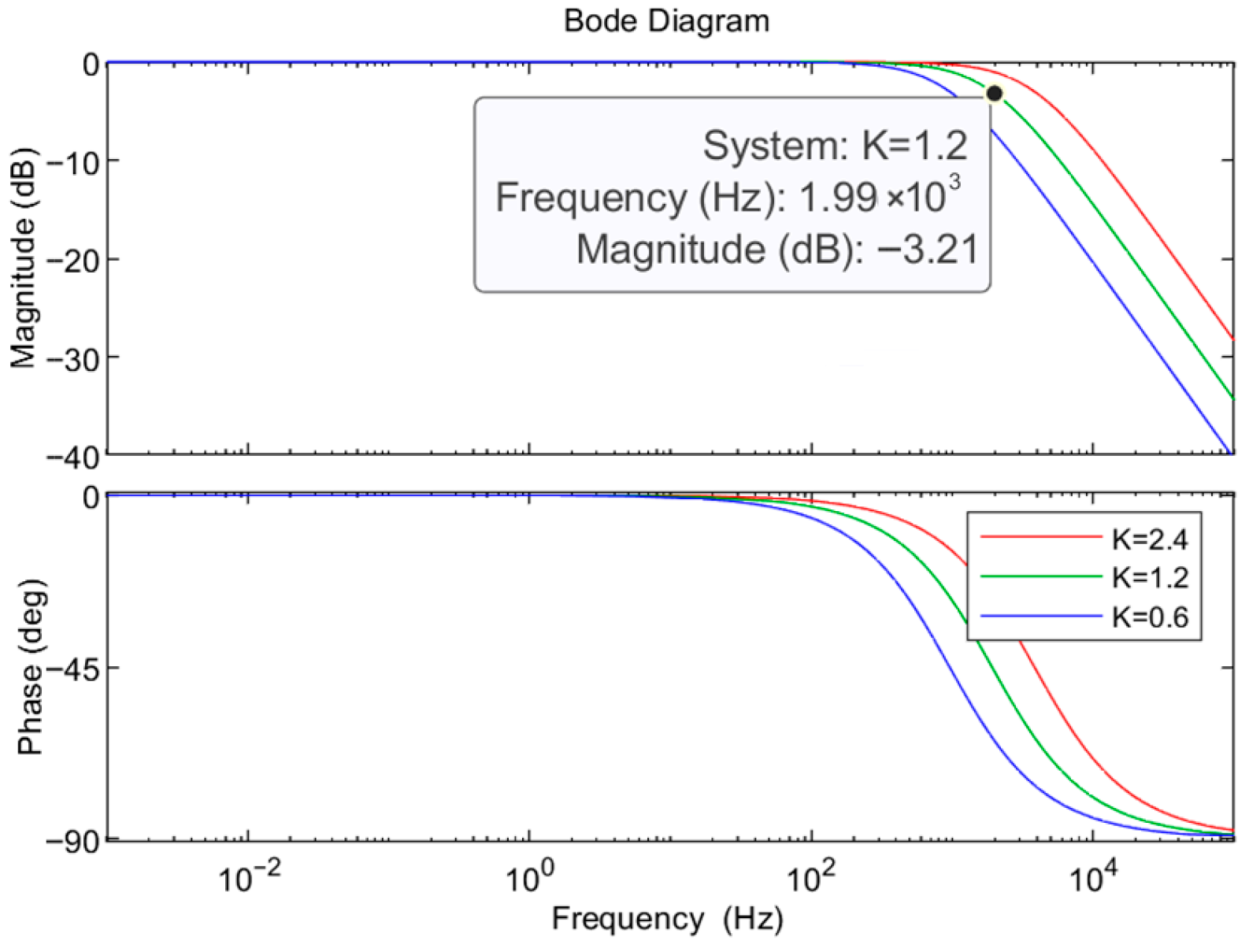

4.1. Current Loop Control

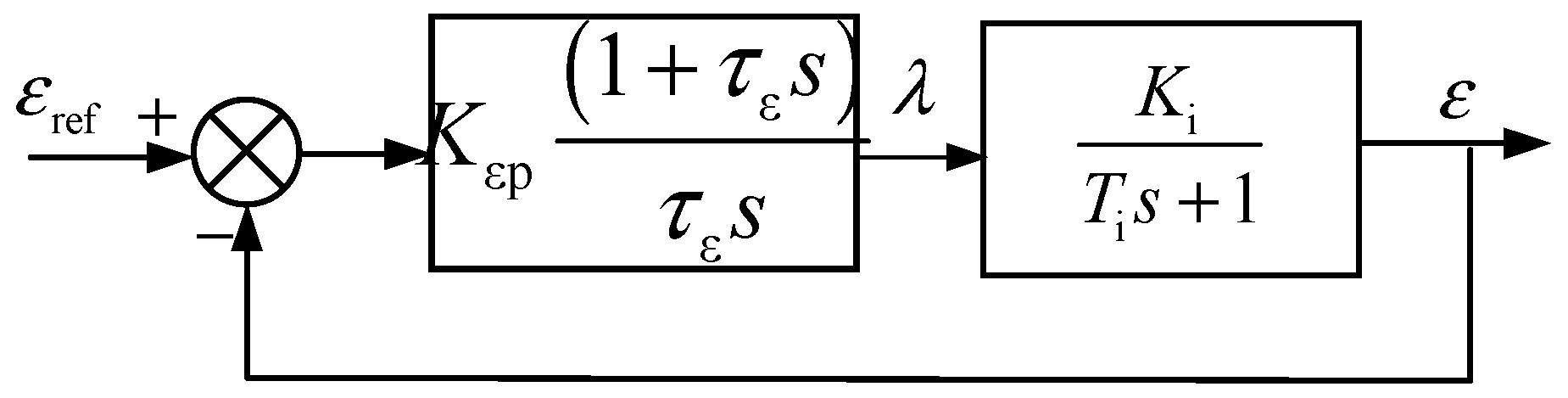

4.2. Voltage Loop Control

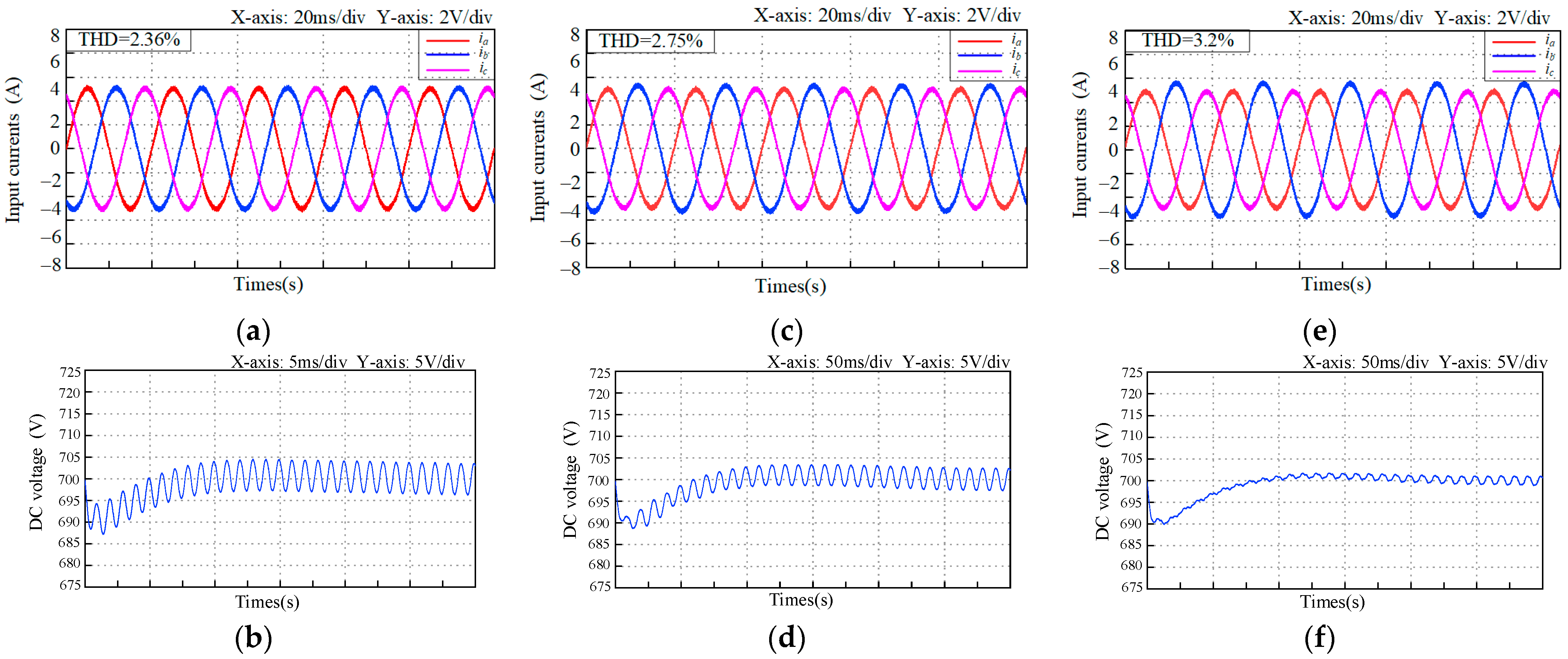

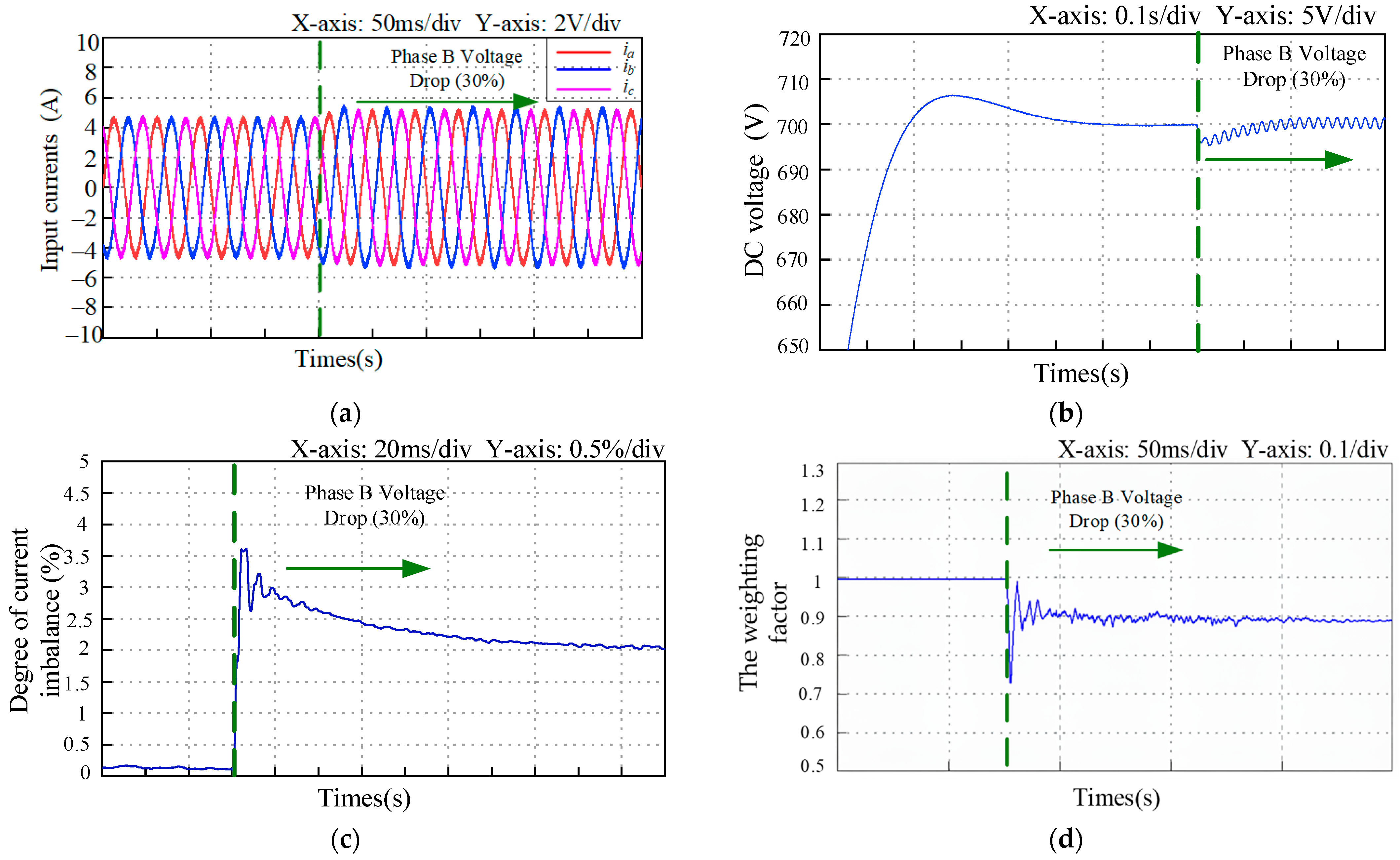

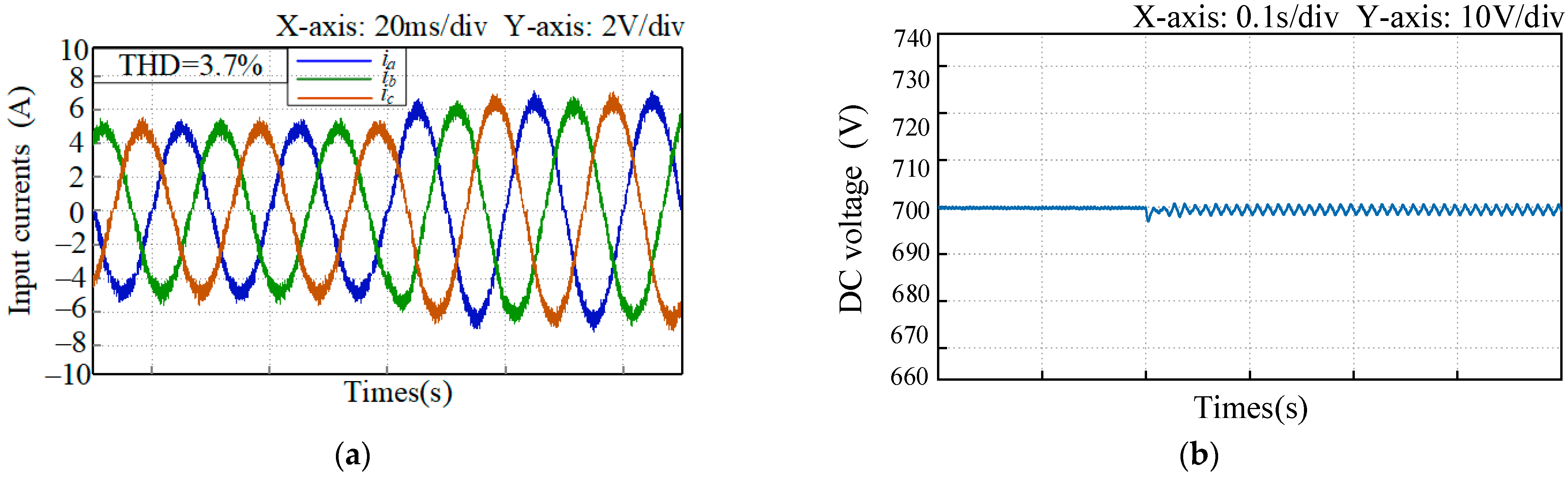

5. Simulation Verification

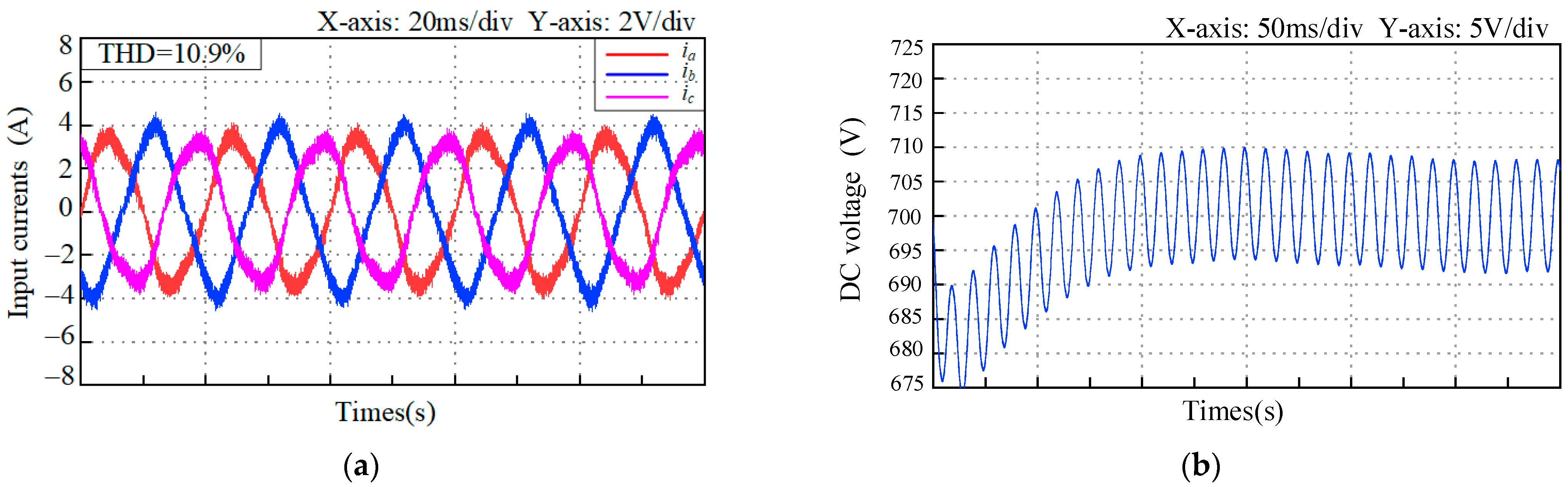

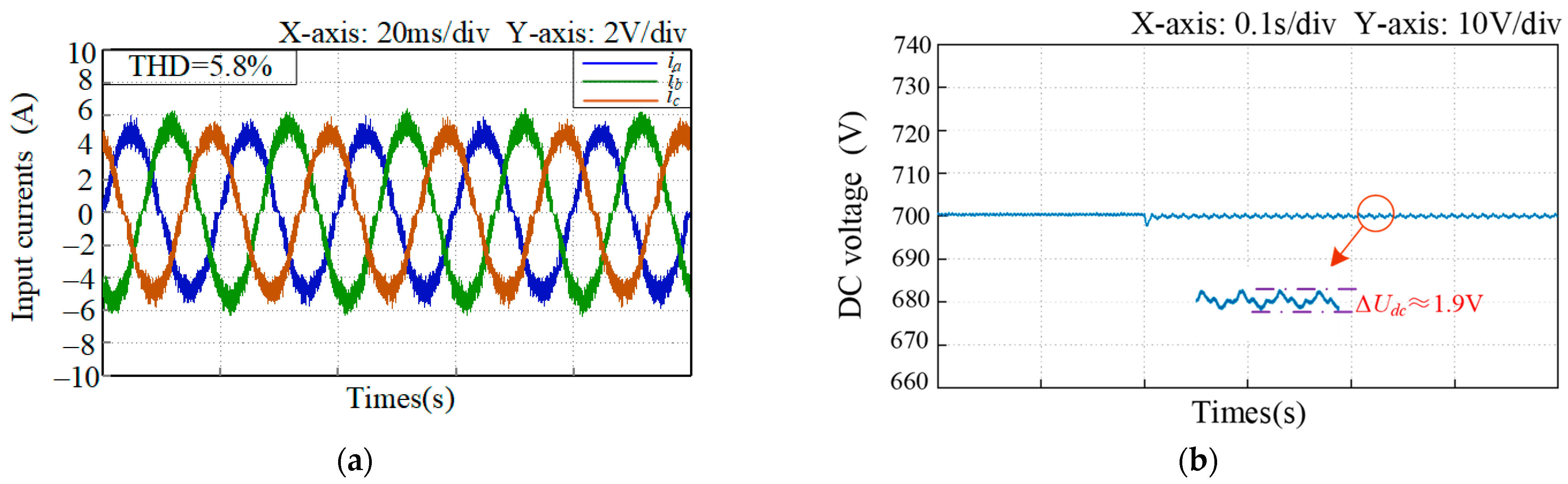

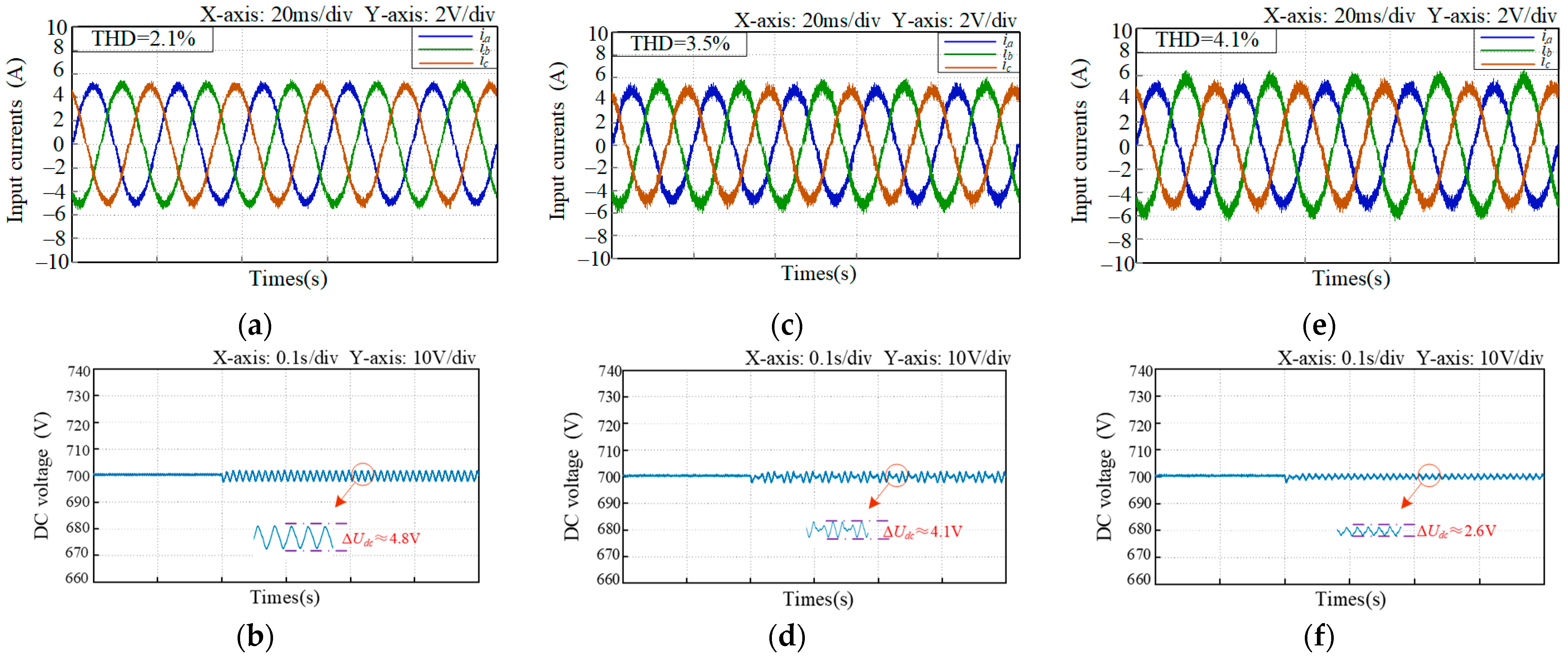

6. Experimental Verification

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FS-MPC | Finite-set model predictive control |

| SMC | Sliding mode control |

| THD | Total harmonic distortion |

| BPSC | Balanced positive-sequence current control |

| IAPC | Instantaneous active power control |

| MPDCC | Model predictive duty-cycle control |

| FCS-MPDPC | Finite-set model predictive direct power control |

| LADRC | Linear active disturbance rejection control |

| SVM | Space-vector modulation |

| CZCD | Current zero-crossing distortion |

References

- Rajaei, A.; Mohamadian, M.; Varjani, A.Y. Vienna-rectifier-based direct torque control of PMSG for wind energy application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 60, 2919–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ren, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Hao, Z. A quadrature signal-based control strategy for Vienna rectifier under unbalanced aircraft grids. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topi. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 5280–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xing, X.; Du, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, C.; Blaabjerg, F. An improved model predictive control method using optimized voltage vectors for Vienna rectifier with fixed switching frequency. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 38, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Cao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, K. An improved modulation strategy without current zero-crossing distortion and control method for Vienna rectifier. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 15199–15213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xing, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, R. A Modulation Method with Current Zero-Crossing Distortion Elimination and Voltage Balance Control for the RSHMC Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 15536–15547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, J.; Sun, Y.; Su, M.; Lin, J.; Xie, S.; Huang, S. A generalized design framework for neutral point voltage balance of three-phase Vienna rectifiers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 10221–10232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbarnejad, A.; Vaez-Zadeh, S.; Khalilzadeh, M. Sensorless virtual flux combined control of grid connected converters with high power quality under unbalanced grid operation. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 12, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Sun, Y.; Lin, J.; Su, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Resistance-emulating control strategy for three-phase voltage source rectifiers under unbalanced grids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z. Impact of unbalance on electrical and torsional resonances in power electronic interfaced wind energy systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 3105–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-P.; Song, S.-G.; Park, S.-J.; Kang, F.-S. Imbalance compensation of the grid current using effective and reactive power for split DC-link capacitor 3-leg inverter. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 81189–81201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enjeti, P.N.; Choudhury, S.A. A new control strategy to improve the performance of a PWM AC to DC converter under unbalanced operating conditions. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1993, 8, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ding, L.; Xu, X.; Wang, K.; Lu, Q.; Li, Y.W. A common-mode voltage elimination scheme by reference voltage decomposition for back-to-back two-level converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 4463–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Huang, H. Maximizing instantaneous active power capability for PWM rectifier under unbalanced grid voltage dips considering the limitation of phase current. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 5998–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Ma, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Gao, Y. Deadbeat control based on current predictive calibration for grid-connected converter under unbalanced grid voltage. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 5479–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.; Yan, Y. A neutral-point voltage controller with hybrid parameters for NPC three-level grid-connected inverters under unbalanced grid conditions. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 4367–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, L. Different control objectives for grid-connected converter under unbalanced grid voltage using forgotten iterative filter as phase lock loop. IET Power Electron. 2015, 8, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Xie, X.; Zhao, C.; Liu, S. A Novel Control Strategy Based on Natural Frame for Vienna-Type Rectifier Under Light Unbalanced-Grid Conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, J.; Prasanna, I.V.; Panda, S.K. Reduction of input current harmonic distortions and balancing of output voltages of the Vienna rectifier under supply voltage disturbances. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 5802–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hang, L.; Yao, W.; Lu, Z.; Tolbert, L.M. A novel strategy for three-phase/switch/level (Vienna) rectifier under severe unbalanced grids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 60, 4243–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Liu, K.; Ran, X.; Huai, Q.; Yang, S. Model predictive duty cycle control for three-phase Vienna rectifiers with reduced neutral-point voltage ripple under unbalanced DC links. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 5578–5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Fang, J.; Cheng, H.; Dong, L. A novel suppression method for input current zero-crossing distortion of the Vienna rectifier based on negative-sequence current regulation under the unbalanced grid. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 12, 3699–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, M.; Shekari, M.; Ghoreishy, H.; Gholamian, S.A. Virtual flux direct power control for Vienna rectifier under unbalanced grid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 8115–8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, L.; Wang, H.; Xie, S.; Lin, J.; Yu, B.; Sun, Y.; Su, M. An Algebraic Modulation and Controlled-Impedance-Source Method for Vienna Rectifier Under Unbalanced Conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Chen, W.; Liserre, M.; Blaabjerg, F. Power controllability of a three-phase converter with an unbalanced AC source. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 30, 1591–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Liu, W.; Hu, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Xu, D. Negative sequence current regulation based power control strategy for Vienna rectifier under unbalanced grid voltage dips. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 71, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Sun, Y.; Cui, X.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y. A compound control strategy of three-phase Vienna rectifier under unbalanced grid voltage. IET Power Electron. 2021, 14, 2574–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, N.; Yang, Y.; Fan, Z. A Novel Strategy for Current Distortion Suppression Based on Space Vector Modulation for Vienna Rectifiers Under the Wide-Range Unbalanced Grids. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2026, 41, 2134–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbat, M.B.; Farag, A.Y.; Mattavelli, P.; Dominguez-García, J.L. Nonlinear Control of the Four-Wire Y-Converter for Grid Integration of 400V DC Microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 7th International Conference on DC Microgrids, Tallinn, Estonia, 4–6 June 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, W.; Li, X.; Li, Y. Sliding mode control of Vienna rectifier under unbalanced weak power grid. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 39095–39109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, A.A.; Gole, A.M. Enhanced instantaneous power theory for control of grid connected voltage sourced converters under unbalanced conditions. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 32, 6652–6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadinia, A.R.; Karshenas, H.R. Current shaping in a hybrid 12-pulse rectifier using a Vienna rectifier. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sign of Current | Sx | SX | Output Voltage uxo of x-Phase | Sign of Current | Sx | SX | Output Voltage uxo of x-Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ix > 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ix < 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | E | 0 | 1 | −E |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Grid-side phase voltage (V) | 220 |

| Grid frequency (Hz) | 50 |

| Inductance LS (mH) | 3 |

| Capacitor C1, C2 (μF) | 3000 |

| DC voltage (V) | 700 |

| Load resistance (Ω) | 150 |

| Switching frequency (Hz) | 10 k |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Tian, M. A Weighted Control Strategy Based on Current Imbalance Degree for Vienna Rectifiers Under Unbalanced Grid. Machines 2025, 13, 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121139

Wang H, Liu Z, Tian M. A Weighted Control Strategy Based on Current Imbalance Degree for Vienna Rectifiers Under Unbalanced Grid. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121139

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Haigang, Zongwei Liu, and Muqin Tian. 2025. "A Weighted Control Strategy Based on Current Imbalance Degree for Vienna Rectifiers Under Unbalanced Grid" Machines 13, no. 12: 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121139

APA StyleWang, H., Liu, Z., & Tian, M. (2025). A Weighted Control Strategy Based on Current Imbalance Degree for Vienna Rectifiers Under Unbalanced Grid. Machines, 13(12), 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121139