1. Introduction

The growing interest in automated driving necessitates robust and systematic validation methodologies to design, test, and assess Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) [

1,

2].

As human error remains the predominant cause of accidents [

3], safety-oriented technologies have been progressively introduced to mitigate critical situations. Thanks to the increased computational power of current processors, modern safety systems are able to guarantee prompt response in hazardous conditions [

4]. New systems, such as Adaptive Cruise Control [

5,

6], Blind Spot Detection [

7], Automated Lane Change [

8], and Driver Lane Change Intention Prediction [

9], have also been developed, thereby fostering the development of driverless vehicles [

10]. This evolution requires comprehensive testing infrastructures tailored to the specific scenario under investigation [

11,

12]. In the literature, three main testing approaches are reported as follows [

13]: full-scale vehicle on-road/on-track testing [

14], computer simulations [

12,

15], and scaled vehicle experimental testing [

16].

The first scenario involves full-scale on-road testing, which is considered the most effective and precise approach, as it can capture the whole vehicle interactions in real-world conditions [

13]. However, this methodology requires dedicated test facilities, high-performance sensors [

17], and compliance with regulatory and logistical constraints. While it provides high-fidelity data, this approach suffers from limited replicability, since recreating identical scenarios is challenging due to environmental variability. Moreover, on-road tests may expose occupants and pedestrians to potential safety risks [

18].

The second approach, i.e., computer simulations, enables replicability and can be tailored to parametric investigations of road characteristics, e.g., intersection angle, curvature, and lane width [

19]. Nevertheless, this methodology inherently depends on the accuracy level of the employed models, which strongly influences the reliability of the obtained results [

20]. Among the simulation environments, AIMSUN [

21], Vissim [

22], and Silo [

23] are used the most for small and medium-scale traffic flow analysis. The open-source SUMO [

24] is particularly suited for large-scale traffic simulations and for integration with external control and communication frameworks. Gazebo [

25] is effective for sensor and actuator simulation. CARLA [

26,

27] provides realistic 3D environments, dynamic weather conditions, and high-fidelity sensor models. In contrast, CarSim [

28,

29] offers highly accurate vehicle dynamics models and is often used together with MATLAB/Simulink R2024a [

30] for controller development and hardware-in-the-loop testing. Finally, the Cellular Automata approaches [

31] are employed when simplified yet computationally efficient representations of traffic are sufficient.

To mitigate the cost, safety, and model-dependence limitations associated with full-scale and simulation-based testing, scaled vehicles have gained increasing attention in recent years [

32], although their usage dates back to the 1930s for studying trailer sway, turning radius, and automobile accident reconstruction [

33]. These platforms offer a cost-effective alternative to full-scale testing; they are easy to operate without requiring specialized training, involve limited maintenance, and require only small test facilities. Moreover, they are typically characterized by a high modularity level in terms of embedded sensors and components. A comprehensive overview of recent developments, applications, and technological trends in small-scale self-driving vehicles is provided in [

20].

These platforms are generally derived from Radio-Controlled (RC) cars [

18,

32,

34], which undergo hardware modification, and are driven by electric powertrains, allowing smoother and more precise control, since they are less affected by vibration issues [

2] and suitable for indoor testing.

The sensor setup of scaled vehicles generally includes a three-axis Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) providing acceleration signals required by control algorithms. In [

34], these signals are provided as inputs to a particle filter to enhance real-time vehicle localization. Global Positioning Systems (GPS)/Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) are typically adopted for trajectory reconstruction [

35,

36], while LiDAR sensors are adopted for environmental identification and obstacle detection [

37]. Cameras are primarily employed for lane keeping and traffic sign recognition [

38]. Data acquisition, decision-making, and control tasks are handled by embedded computing units such as Raspberry Pi and NVIDIA Jetson.

Despite their compact size, these platforms can achieve speeds and accelerations comparable to full-scale vehicles, making them reliable tools for investigating vehicle dynamics and testing complex control algorithms under challenging conditions, including drifting and rally like maneuvers [

34,

39].

As shown in [

20], the most common scales for these kinds of testbeds, in order of popularity, are

,

, and

. Larger scales, such as

, are particularly suitable for vehicle dynamics studies, as they better reproduce the behavior of full-scale passenger cars and allow the integration of standard-sized sensors. Nevertheless, they require more powerful motors and larger test areas. Conversely, smaller scales such as

or

are cost-effective, since they rely on smaller actuators and require smaller experimental facilities. These smaller platforms are often adopted for platooning studies, whereas larger ones are preferred for more detailed investigations of vehicle dynamics [

40].

Among the most recent developments, an open-source platform for high-speed off-road driving research is presented in [

32]. Built on a similar concept, Baumann et al. [

41] introduce the ForzaETH Race Stack, a

scale platform, based on off-the-shelf components. Finally, other

scale platforms featuring advanced sensor modules for key control signals are proposed in [

18,

37], providing low-cost self-driving vehicle testbeds for indoor experimentation. These platforms differ primarily in their development approach, ranging from fully custom designs, in the former, to adaptations of commercial RC vehicles, in the latter.

From a control perspective, scaled vehicles have proven to be a valuable tool for validating advanced control methodologies, as stated by Ribeiro et al. [

16]. Švec et al. [

42] evaluate Koopman operator-based models on reduced-scale platforms, confirming their potential for capturing nonlinear vehicle dynamics. Cataffo et al. [

43] develop a Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) strategy and deploy it on a

scale platform to minimize lap times in Autonomous Vehicles racing scenarios. Bohn et al. [

44] present a dedicated custom-scale platform, the ZeloS, equipped with advanced perception and communication sensors, specifically designed to support the development and validation of autonomous driving algorithms. Similarly, Natvig et al. [

23] employ scaled vehicles to test machine learning-based approaches, such as reinforcement learning, taking advantage of their ability to perform fast and repeatable experiments with lower costs and risks. In addition, scaled vehicles are also shown to be effective in estimating key vehicle parameters, such as cornering stiffness and yaw moment of inertia, through identification methods based on the vehicle’s lateral dynamic [

16]. Other studies focus on advanced control strategies for drifting; Domberg et al. [

4] employed deep neural network-based controllers, Zhou et al. [

45] develop a model predictive control framework, Park and Kang [

46] propose a two-level controller, combining path-tracking and steady-state drift control. These last three approaches have been successfully validated on

scale RC cars. Additional applications include road profile estimation, as demonstrated by Tudon–Martinez et al. [

47], or the development of LiDAR-equipped platforms for cooperative driving and platooning experiments, as shown by Miller [

48].

Very few studies explore the implementation of the Stanley Controller (SC) and the Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) on scaled vehicles; the existing works typically concentrate either on vehicle-dynamics analysis or on the validation of path-following strategies performed in controlled or semi-controlled environments [

16,

20]. These proving grounds inherently avoid the challenges introduced by realistic outdoor operation, in which terrain irregularities and environmental disturbances significantly affect test execution and repeatability. In addition, GNSS measurements are rarely employed on scaled platforms, as most experimental setups rely on optical tracking systems, which require lane markings or structured reference lines for localization. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior work has experimentally compared multiple trajectory-tracking controllers in uncontrolled outdoor conditions using a modular scaled vehicle platform.

To address this gap, the present study introduces a

scale platform, originally customized and validated in open-loop maneuvers [

2], which is further upgraded with enhanced hardware to support fully autonomous repeatable, infrastructure-free, outdoor operation through a sensor-fusion approach exploiting GNSS-aided state estimation. This configuration enables experimental conditions that are not typically addressed in existing scaled-vehicle studies. The main features of the platform are as follows:

Complete hardware modularity and software reconfigurability;

Realistic double-wishbone suspension;

Electrified powertrain providing smooth torque delivery and precise low-speed control, suitable for both indoor and outdoor experiments;

A dedicated control strategy for trajectory tracking;

Use of low-cost commercial sensors supported by accurate sensor-fusion estimation algorithms.

The enhanced platform includes an IMU with embedded GNSS able to communicate via CAN protocol. Regarding the software, an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) is implemented to enhance position estimation by fusing IMU and GNSS data. Two alternative path-following control strategies, i.e., the SC and the LQR, have been developed and integrated into the real-time architecture, exploiting more accurate estimation provided by the EKF. These improvements collectively enhance closed-loop maneuver testing [

2].

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a detailed overview of the testbed, describing the hardware and its main features;

Section 3 presents the development and the implementation of the path-following control algorithms;

Section 4 illustrates test procedures, detailing maneuvers and facilities;

Section 5 summarizes the main findings of the activity;

Section 6 assesses the overall effectiveness of the proposed research and outlines possible future developments.

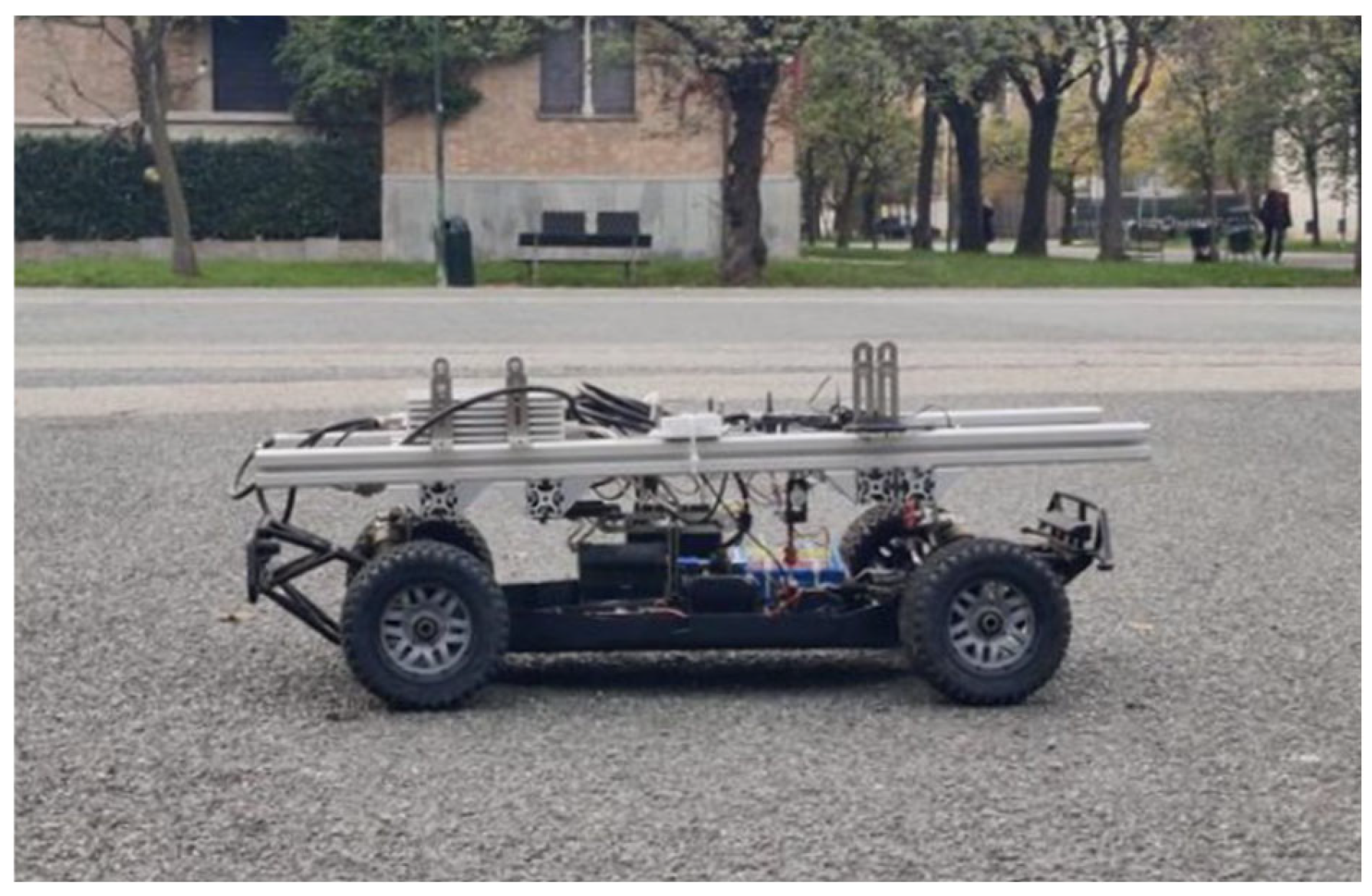

2. Vehicle Overview

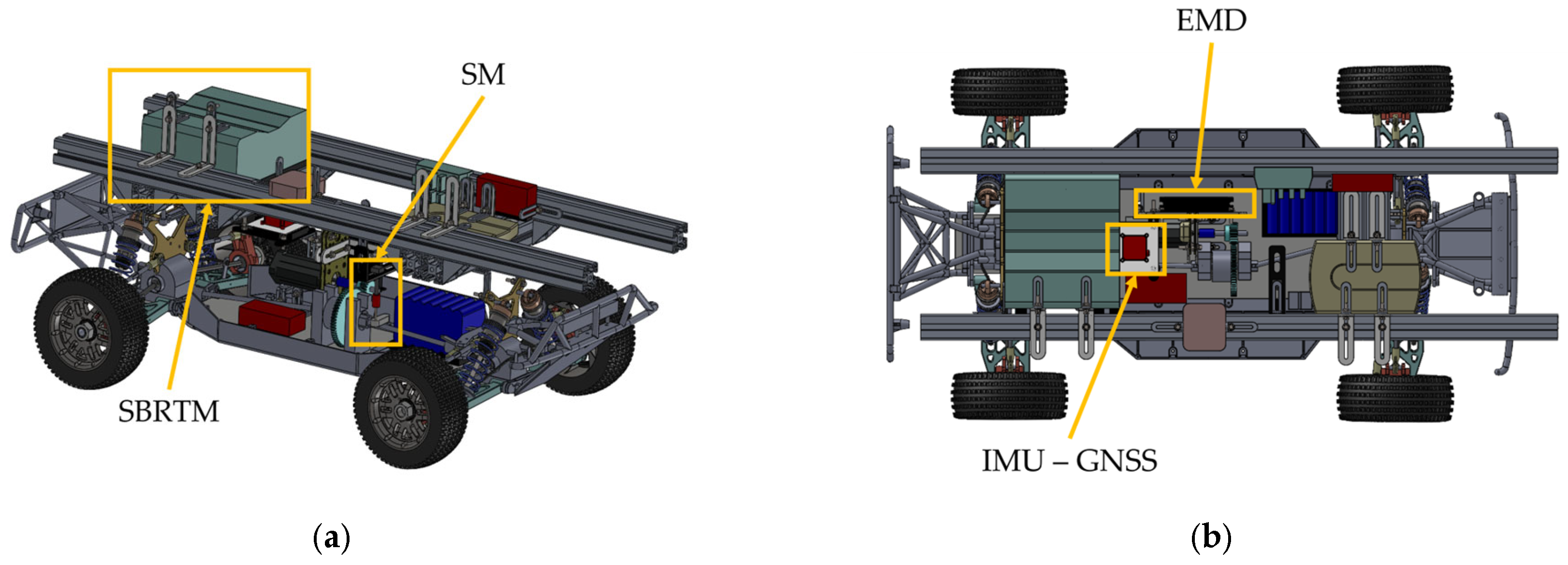

The experimental platform employed in this study, shown in

Figure 1, is a

scale modular testbed, whose preliminary version was presented in [

2] and which has been upgraded to enable path-tracking capabilities. The chassis is based on a commercial radio-controlled vehicle equipped with a

cc two-stroke Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) and a four-wheel-drive fixed-gear transmission, comprising three open differentials: one inter-axle and one inter-wheel differential per axle.

The suspension adopts an independent double-arm geometry at all four corners, each equipped with springs, dampers, and anti-roll bars. Camber and toe angles are adjustable at the front and at the rear within the range . The chassis geometry is characterized by the wheelbase m, track width m, and wheel radius m. The total vehicle mass in this baseline configuration is approximately kg, with a static distribution.

To convert the vehicle into a research-oriented testbed, the original layout has been electrified by replacing the ICE and its dedicated throttle servomotor with a three-phase Brushless DC (BLDC) motor rated at

W peak power and

V nominal voltage, capable of reaching

rpm and delivering a maximum torque of

Nm at

A. The motor features a built-in Hall sensor and is controlled via an advanced ESCON Electric Motor Driver (EMD), which enables closed-loop regulation of speed. In contrast with the first version of the setup [

2], the current driveline does not include the planetary gearbox to increase the top speed of the vehicle.

Real-time control is handled by a Speedgoat Baseline Real-Time Target Machine (SBRTM), a powerful and versatile real-time platform [

49] running MATLAB/Simulink control architectures and supporting a wide range of digital/analog input/output, as well as complex multi-sensor architectures. Wireless communication between the SBRTM and the host machine is established through a dedicated onboard router connected to the SBRTM via Ethernet and capable of creating a local network.

The electrical power is supplied by a V, Ah Li-ion battery pack, whose dimensions and mass are comparable to those of the original fuel tank, thereby avoiding major modifications to the chassis layout. A separate V, mAh Li-Po battery powers the front-wheel steering Servomotor (SM). The SM is actuated through a Hz Pulse Width Modulation signal, transmitted by a standard radio transmitter/receiver unit.

All the modifications produce a mass increase of approximately kg, yielding a final mass of roughly kg. To compensate for this additional weight and preserve dynamic response, the original suspension springs are replaced with stiffer ones on the front; the stiffness has been increased from N/m to N/m, while on the rear, it has been raised from N/m to N/m. A CAD-based estimation is exploited to verify that the vehicle center of mass () remains in the vehicle mid-plane, while its vertical position is increased by approximately mm due to the additional hardware mounted on the chassis.

To enhance measurements and controllability, the vehicle is updated with a CSS Electronics CANmod.gps module (IMU—GNSS), communicating with the SBRTM via the CAN 2.0A/2.0B protocol. The unit integrates a high-performance IMU measuring linear accelerations and angular velocities (sampling frequency of

Hz, the accuracy of the accelerometer of

m/s

2, the accuracy of the gyroscope of

°/s). The GNSS receiver acquires geodetic coordinates (sampling frequency of 1 Hz, accuracy of

m (Circular Error Probable) [

50]). Overall, the IMU signals are more affected by noise than the GNSS measurements.

3. Development of the Path-Following Control Strategies

This section describes the control architecture developed and implemented on the experimental testbed for the path-following experiments. The vehicle reference frame is oriented such that and axis lies in the vehicle midplane, represents the longitudinal axis and points forward, is vertical and directed upwards, while is lateral, forming a right-handed Cartesian coordinate system.

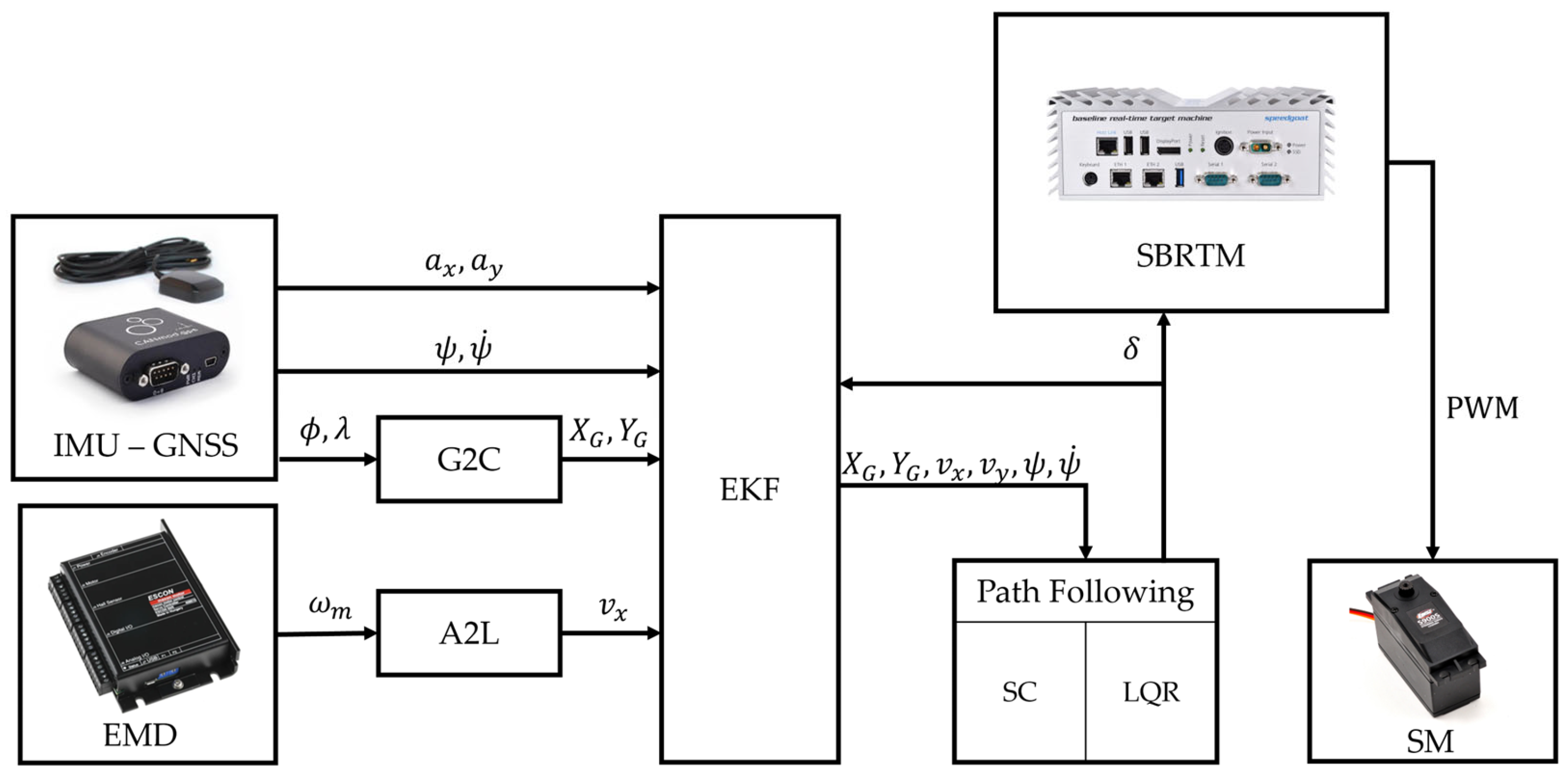

Figure 2 illustrates the overall signal flow, from data acquisition (IMU—GNSS, EMD) to the steering system, actuated by SM. The acquired signals are processed in real time within the estimator (EKF) and control subsystems (SC and LQR), implemented in the SBRTM.

The IMU provides longitudinal and lateral acceleration components in the vehicle reference frame

and

, the orientation around the

axis

, and its rate

. The GNSS module supplies the vehicle position in the geodetic reference frame, defined by the latitude

, longitude

, and altitude

. These quantities are converted into the global Cartesian reference system

through a custom Geodetic-to-Cartesian (G2C) converter, based on a standard ellipsoidal Earth model. The longitudinal velocity

, oriented along the

axis, is obtained from the electric motor speed

, which is regulated by the EMD. The relation, described in Equation (A1) in

Appendix A.1 and implemented through the Angular-to-Longitudinal (A2L) block, defines the conversion from

to

.

To obtain accurate and time-consistent estimates of the vehicle dynamic states, the EKF is designed to unify the information provided by sensors at different sampling rates. By fusing IMU and GNSS data, it provides noise-filtered estimates of position, velocity, and orientation. In addition, it also computes an estimation of the lateral velocity , directed along the axis of the vehicle reference frame, which is not directly measured. These estimated states are then used by the SC and the LQR to generate the steering command required for the trajectory tracking. The covariance matrices of the EKF are identified by an optimization process in simulation, exploiting an equivalent 8-degrees-of-freedom (8-DoF) vehicle model.

3.1. Vehicle State Estimation

The state estimator used to enhance the accuracy of the vehicle measurements is an EKF, i.e., a nonlinear extension of the simple Kalman Filter (KF) capable of handling systems affected by strong nonlinearities [

51,

52]. This algorithm can perform an estimation starting from the combination of a mathematical model, expressed in the state space, Equation (1), with noisy sensor measurements, Equation (2), through two sequential phases, prediction and correction. In the prediction step, the filter propagates the current state estimation according to the process model, while in the correction step, the real measurements are used to refine the estimation

In the prediction step, the system states

at time step

are evaluated as a nonlinear function

of the states

and the inputs

at the previous

step by step, Equation (1),

where

represents the process noises evaluated at the time step

.

The measurements

are expressed as a nonlinear function

of the states

by Equation (2),

where

denotes the measurement noise vector.

3.1.1. EKF Process Model

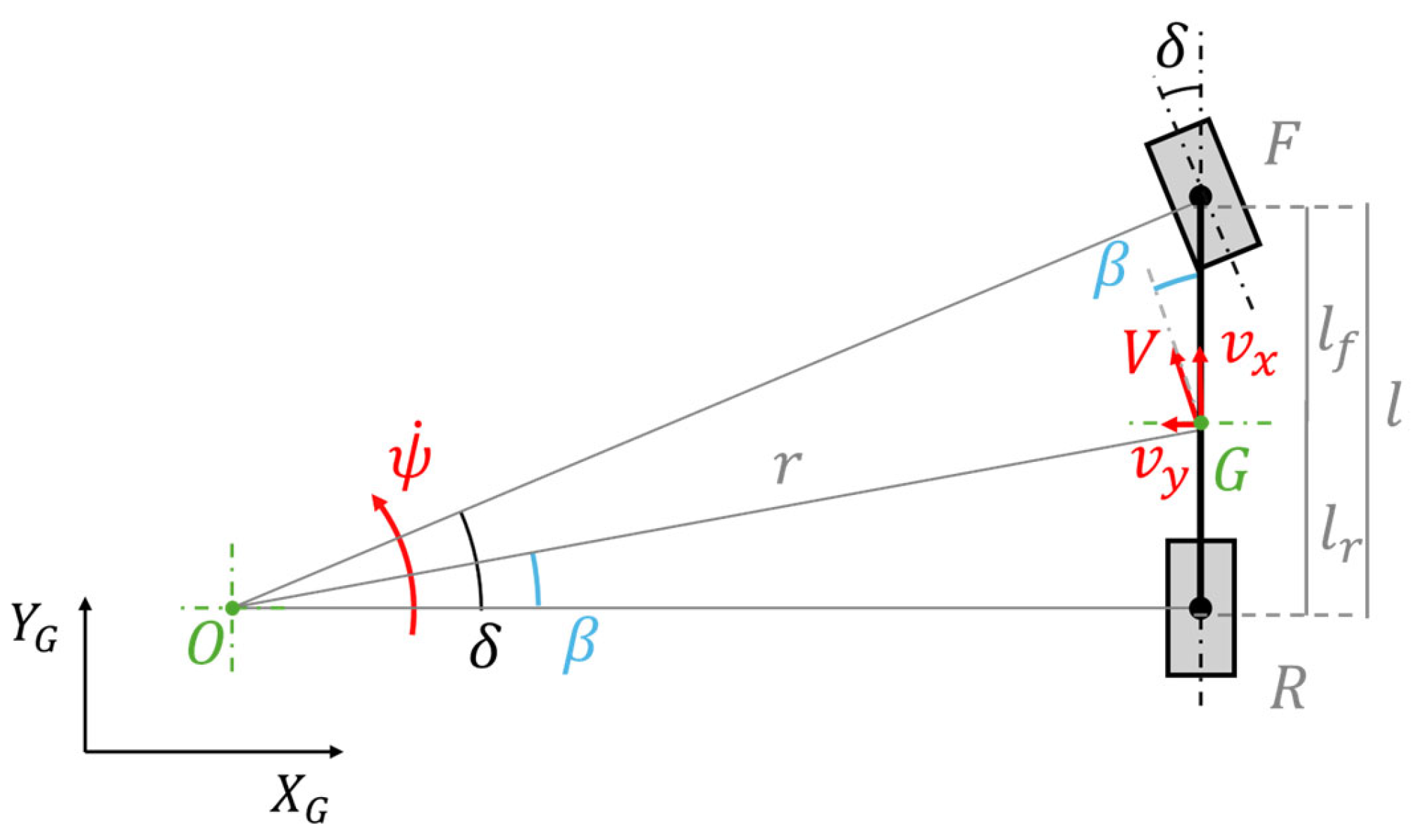

In this estimator, a kinematic bicycle model, illustrated in

Figure 3, is used to represent the vehicle as a single-track system with front-wheel steering [

53,

54]. This simplified vehicle representation provides a good balance between physical accuracy and computational efficiency, which is crucial for real-time applicability on the scaled platform. Moreover, the lack of detailed tire data in the kinematic model prevents the use of a more complex dynamic formulation.

The kinematic bicycle system assumes that the velocity vectors at the front and rear wheels are perfectly aligned with the wheel mid-plane, implying zero longitudinal and lateral tire slip. This approximation can be considered valid at low speeds, where lateral tire forces remain small [

53].

In the kinematic bicycle model:

is the Center of Gravity (CoG);

is the center of curvature;

indicate the front and rear axles;

is the wheelbase;

is the distance between and the front axle ;

is the distance between and the rear axle ;

is the distance between and , namely the radius of the curvature;

is the vehicle speed;

is the sideslip angle, i.e., the angle between and .

In Equation (1), the system state is represented by the vector while the inputs are . It is important to remark that is the only actual control input of the real vehicle, whereas and are measured inputs provided by the IMU. To simplify the EKF formulation, these accelerations are included in the kinematic bicycle process model, Equation (1), as inputs, even though they are not physically commanded. The measurements matrix includes measurements coming from the GNSS, and from the IMU, including the estimated vehicle speed, .

The state equations

are expressed in Equations (3)–(9). In detail, Equations (3) and (4) describe the velocity components in the global reference frame. Equations (5)–(8) provide the vehicle kinematics in the local body-fixed reference frame, while Equation (9) expresses the vehicle speed magnitude from its components.

3.1.2. EKF Covariances Tuning

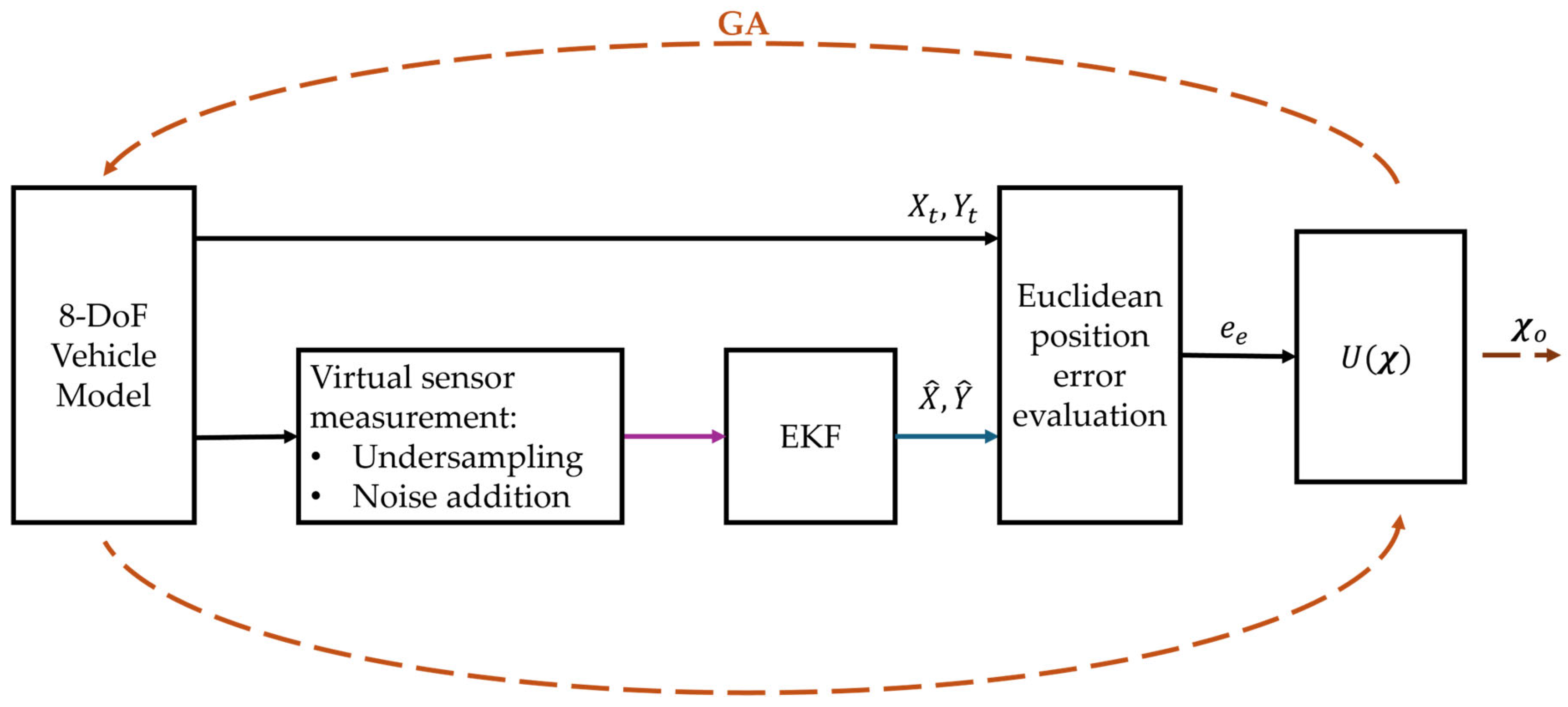

The tuning of the EKF process covariance matrix () is carried out in simulation through an optimization procedure. A Genetic Algorithm (GA) is adopted for this task, since its stochastic nature enables an effective exploration of the parameter space and reduces the risk of converging to local minima. The objective is to minimize the discrepancy between the EKF-estimated states and the ground-truth data generated by an 8-degrees-of-freedom vehicle model. The latter includes longitudinal and lateral translations, roll and yaw rotations, and the rotational dynamics of the four wheels. Its outputs are under sampled and corrupted with white noise to emulate the behavior of the real sensors.

Figure 4 illustrates the schematic workflow of the GA-based optimization procedure adopted for the tuning of the EKF process covariance matrix. The diagram shows the generation of ground-truth data from the 8-DoF vehicle model, the creation of virtual sensor measurements, the EKF estimation, the evaluation of the error, and the cost function creation, used to guide the GA towards the optimal covariance values.

The simulated maneuvers consist of a

ramp steer, followed by a

sweep steer (frequency of

Hz in

s) at

km/h. The measurement-noise covariance matrices adopted for the GNSS and IMU channels are fixed according to the sensor specifications and are reported in

Table A1 of

Appendix A.2.

The multi-variable optimization problem handled by the GA is formulated in Equation (10):

where

represents the set of variables to be tuned,

is the cost function,

is the optimal set of variables. The optimization is constrained by lower and upper bounds, indicated by

and

, which define the admissible range for each parameter.

The cost function combines the maximum and the RMS of the Euclidean position error

, as reported in Equations (11) and (12):

where

are the ground-truth trajectory coordinates,

the EKF estimates, and

is a weighting parameter. The

term is the maximum value of this error over the entire maneuver and

is the root mean square error.

The optimization process starts with a randomly generated initial population and stops after generations.

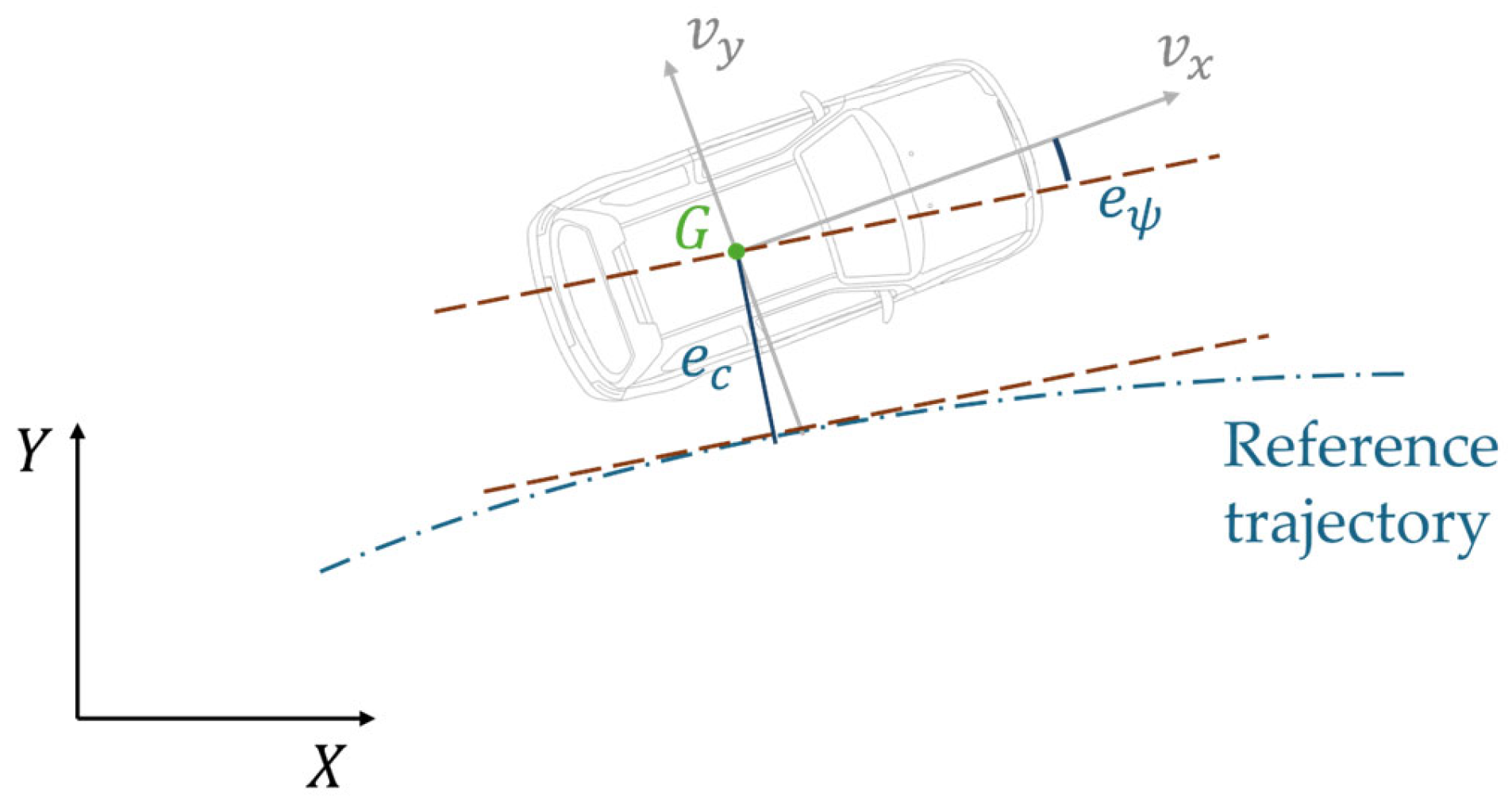

3.2. Stanley Controller

The SC is a geometric path-tracking algorithm commonly employed in autonomous driving applications [

55]. Thanks to its simplicity, robustness, and reduced computational demand, it is particularly suitable for real-time implementation on scaled vehicle platforms. This controller determines the steering angle

based on the cross-track error

, and the heading error

. As shown in

Figure 5,

is defined as the perpendicular distance between the vehicle position and the desired path, while

corresponds to the angular deviation between the vehicle orientation and the tangent to the reference trajectory.

The reference trajectory (

) and orientation (

) are provided as input to the SBRTM and used as a basis for computing

and

from the actual vehicle global position

and yaw angle (

) estimated by the EKF. The analytical expressions of

and

are reported in Equations (A2) and (A3) in

Appendix A.3.

is computed according to Equation (13) as the weighted sum of the heading error and the lateral deviation from the reference trajectory. The selection of the gain

is crucial for ensuring stable tracking performance: excessively low values lead to slow convergence, while overly high values can induce oscillatory behavior; the selected value is reported in

Table A2 within

Appendix A.3.

3.3. LQR Controller

The LQR is a state-feedback control law derived from optimal control theory [

56]. The algorithm determines the optimal control input

by minimizing a quadratic cost function

, reported in

Appendix A.4, Equation (A4). The resulting state-feedback law is expressed in Equation (14).

where

is the feedback gain matrix and

denotes the state vector.

Equation (15) reports the Algebraic Riccati Equation, whose solution is used to compute the feedback gain

.

where

is a scalar weight penalizing the control effort,

is the input matrix of the system and

is the solution of the Algebraic Riccati Equation (ARE). The value of

is reported in

Table A3 in

Appendix A.4.

In this study, the LQR is designed based on the Dynamic Single-Track Error (DSTE) model as expressed in Equation (16). The cost function is formulated with respect to the trajectory-tracking performance, following the approach demonstrated by Bui et al. and Yang [

57,

58]. The state vector

includes the lateral error

, the relative yaw error

, and their time derivatives

and

, whose analytical expressions are reported in

Appendix A.4, Equations (A5) and (A6). The steering angle

represents the control input

(t), while

denotes the reference yaw rate. The matrices

,

, and

define, respectively, the system dynamics, the influence of

, and the contribution of

to the evolution of the error states.

All vehicle parameters used for the controller synthesis are reported in

Table A4 in

Appendix A.4, and a detailed formulation of matrices

,

, and

, is provided in

Appendix A.4, Equations (A7)–(A9), as well.

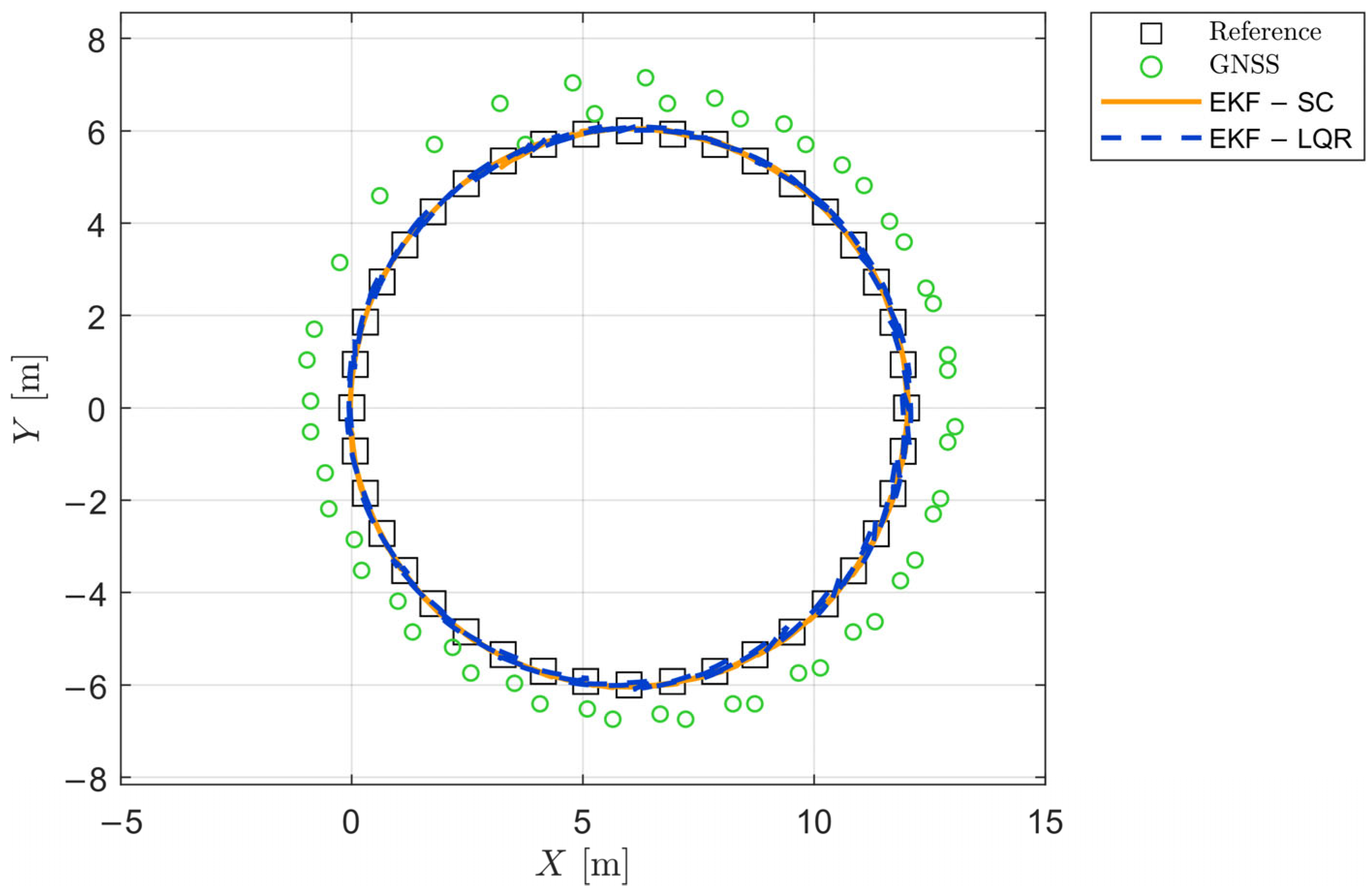

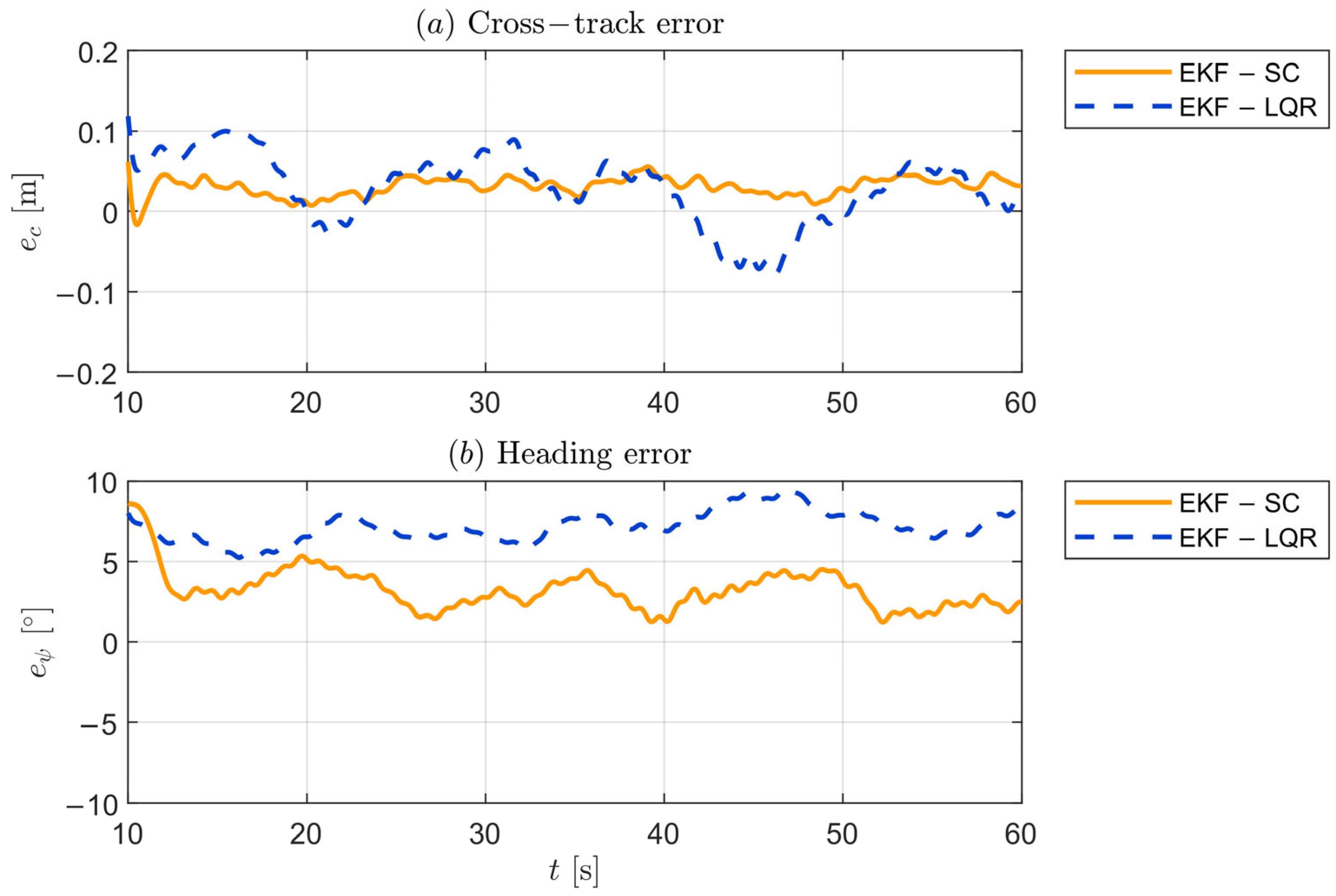

4. Test Procedure and Data Processing

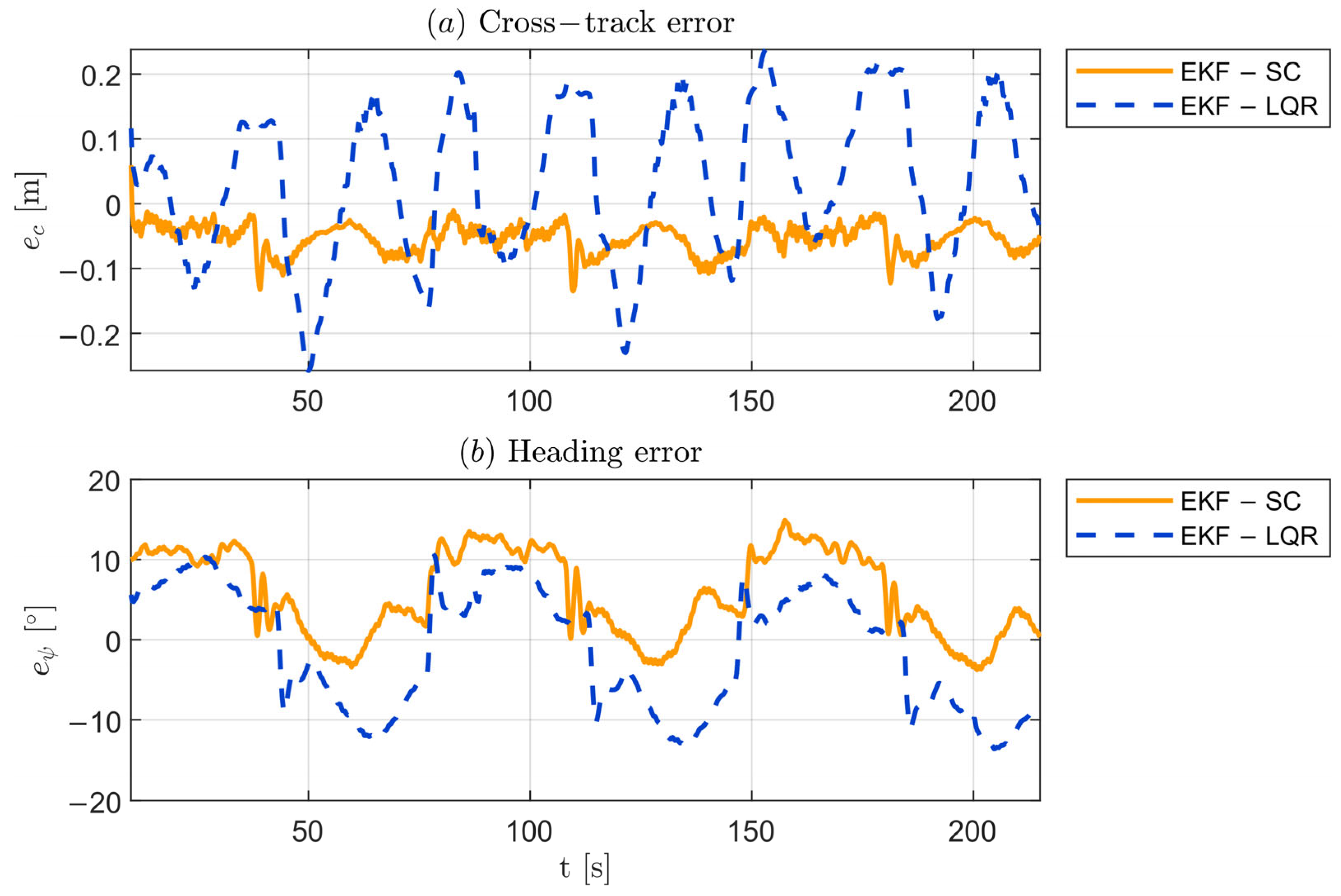

An experimental campaign is conducted to assess the performance of both the state estimator and the path-following controllers.

Figure 6 shows the

scale vehicle ready for the outdoor test campaign.

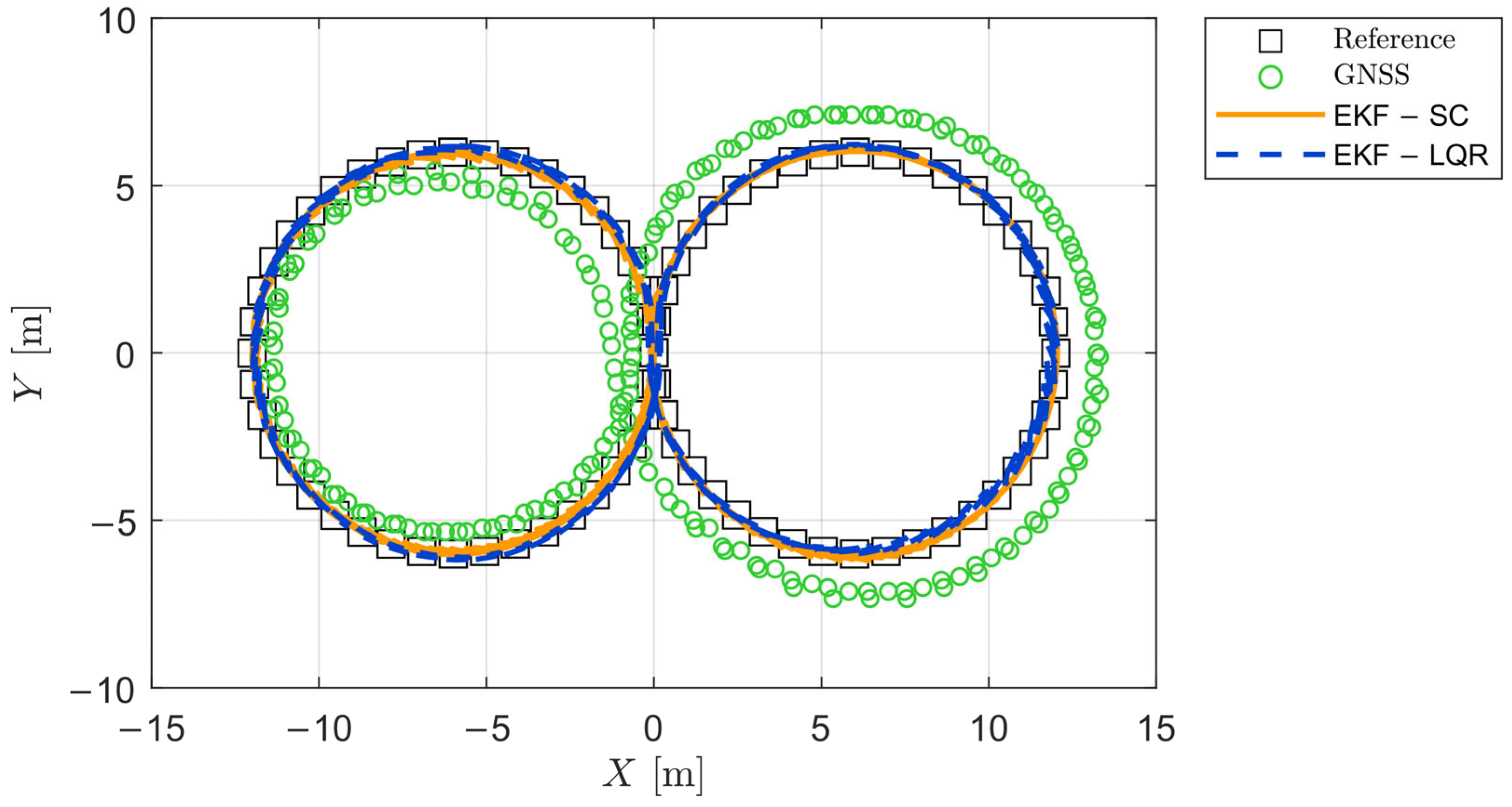

Two reference trajectories are performed at constant speed:

The first maneuver consists of a m-radius circular path, in a counterclockwise direction at km/h;

The second maneuver is a figure-eight path composed of two adjacent m-radius circles, the first counterclockwise and the second clockwise, carried at km/h.

The circular trajectory serves to assess the controllers’ performance under steady-state, constant-curvature conditions, whereas the figure-eight trajectory imposes alternating curvature and short-duration transient dynamics to examine each controller’s capability in managing rapid variations in lateral acceleration and yaw rate. Each test case is repeated three times to check the robustness.

All experimental data are synchronously logged during each run and postprocessed in MATLAB. High-frequency experimental noise components are attenuated using a second-order low-pass Butterworth filter [

59] with a cut-off frequency of

Hz.

For each combination of maneuver and controller, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are evaluated over the entire test duration, excluding short transient phases at the beginning and end of each run. The metrics adopted for the comparison are the maximum (), average (), and Standard Deviation () of both the cross-track and heading errors . Since the LQR does not compute internally, this quantity is obtained during postprocessing. The value represents the peak magnitude of the error, with its original sign.