Intelligent Recognition of Weld Seams on Heat Exchanger Plates and Generation of Welding Trajectories

Abstract

1. Introduction

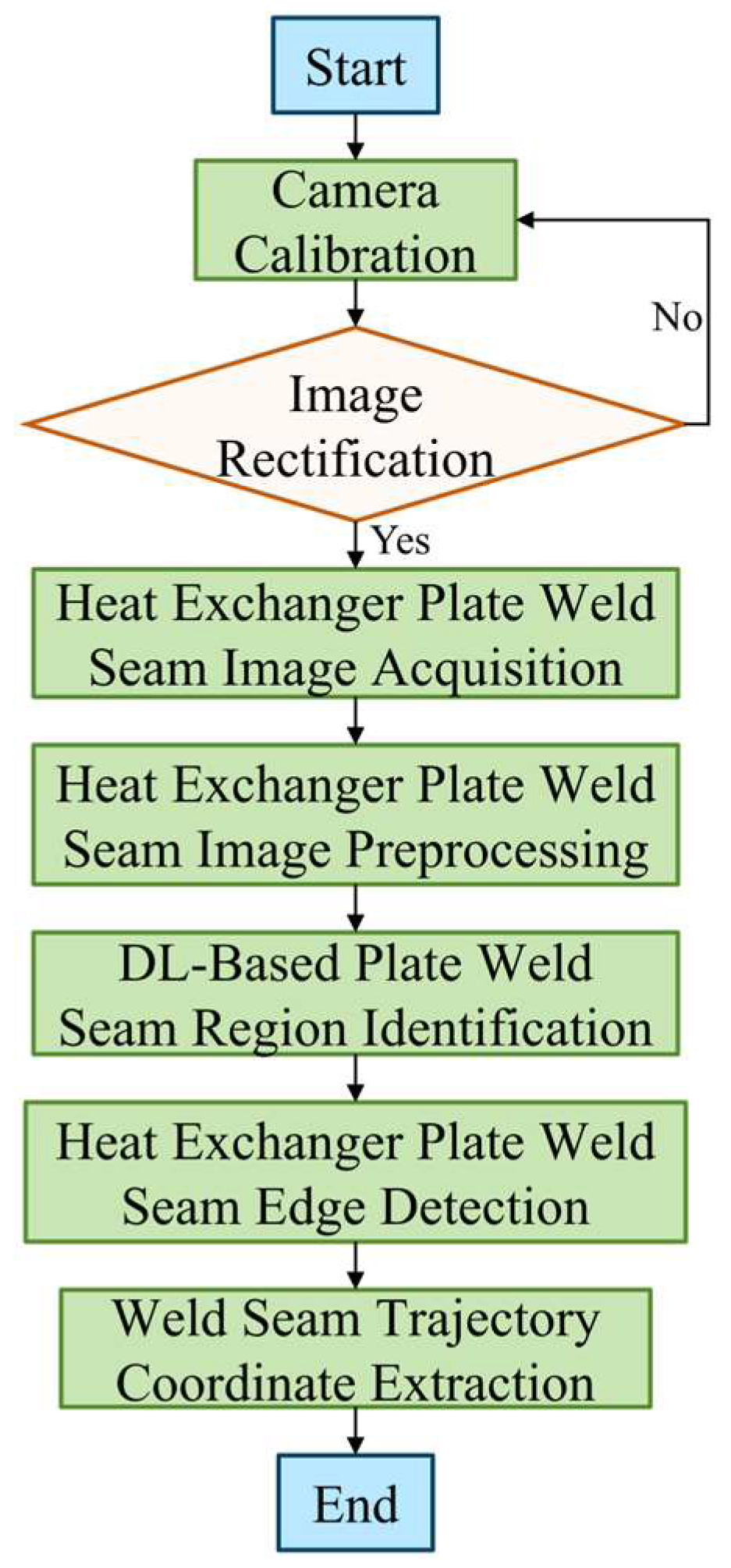

- (1)

- A camera calibration model based on coordinate transformation was constructed, enabling camera calibration and image correction, thereby providing data support for establishing positional transformations for welding robots.

- (2)

- An intelligent edge recognition method for weld seam images integrating deep learning and optimized operators was proposed, significantly reducing computational load and improving processing efficiency. This method achieves accurate identification of heat exchanger plate welds with minimal error, meeting welding precision requirements.

- (3)

- A weld trajectory coordinate detection and generation program based on the Hough transform algorithm was developed, addressing issues such as low efficiency in robot teach-based welding and information silos between recognition and welding systems. This enables high-real-time, high-quality automated weld identification for large-format, long-distance heat exchanger plates.

2. Presentation of the Method for Intelligent Identification of Plate Welds and Generation of Welding Trajectories

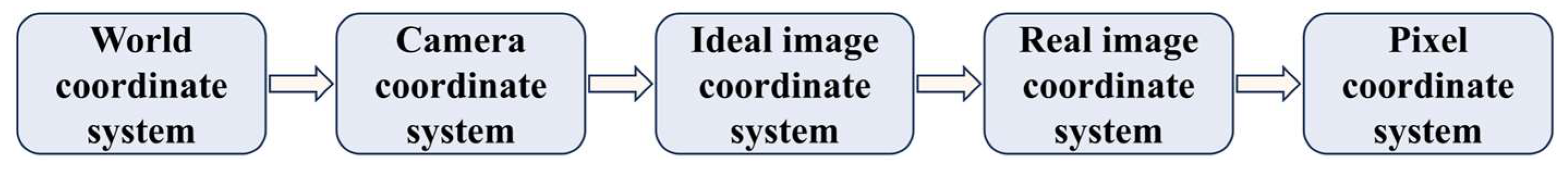

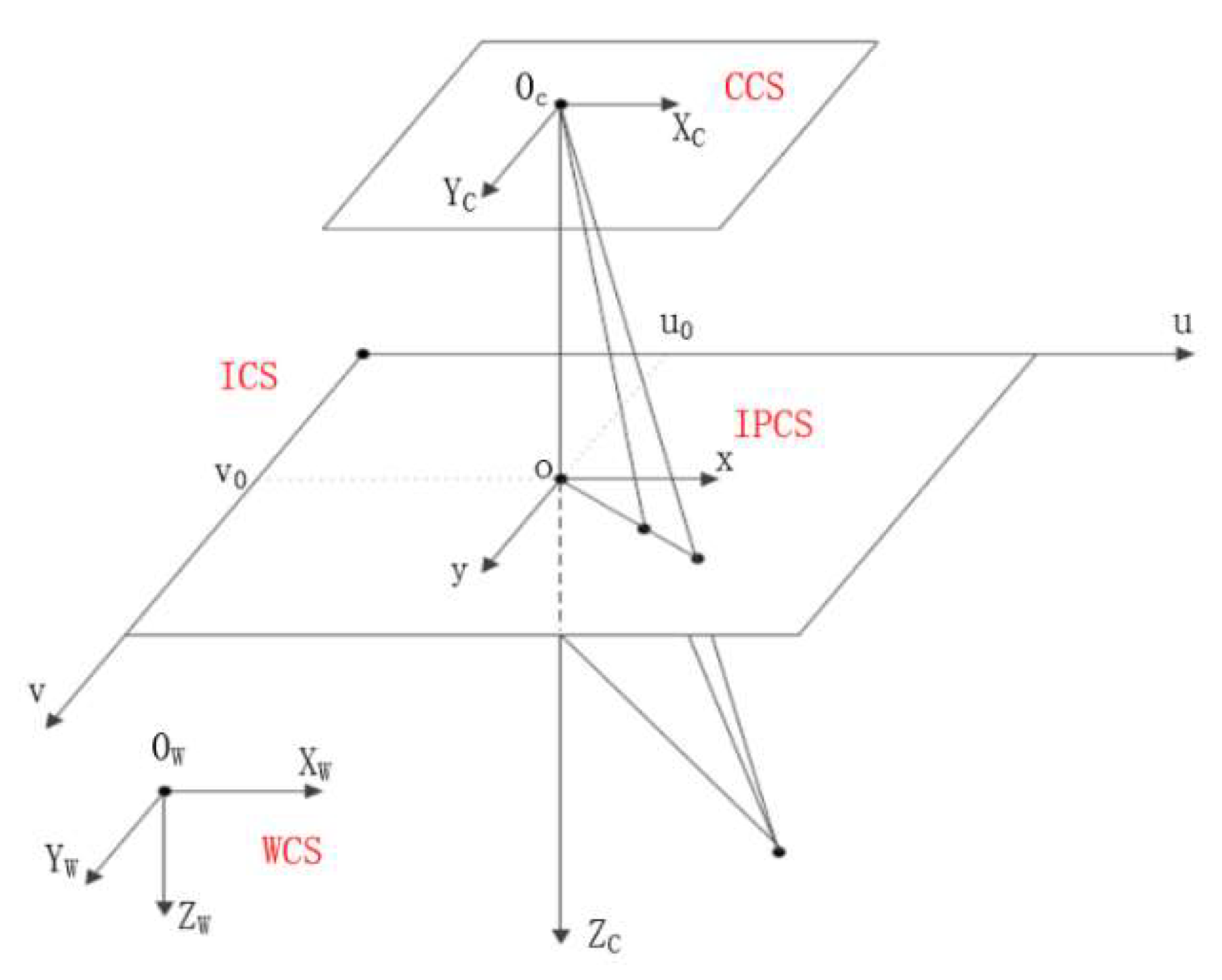

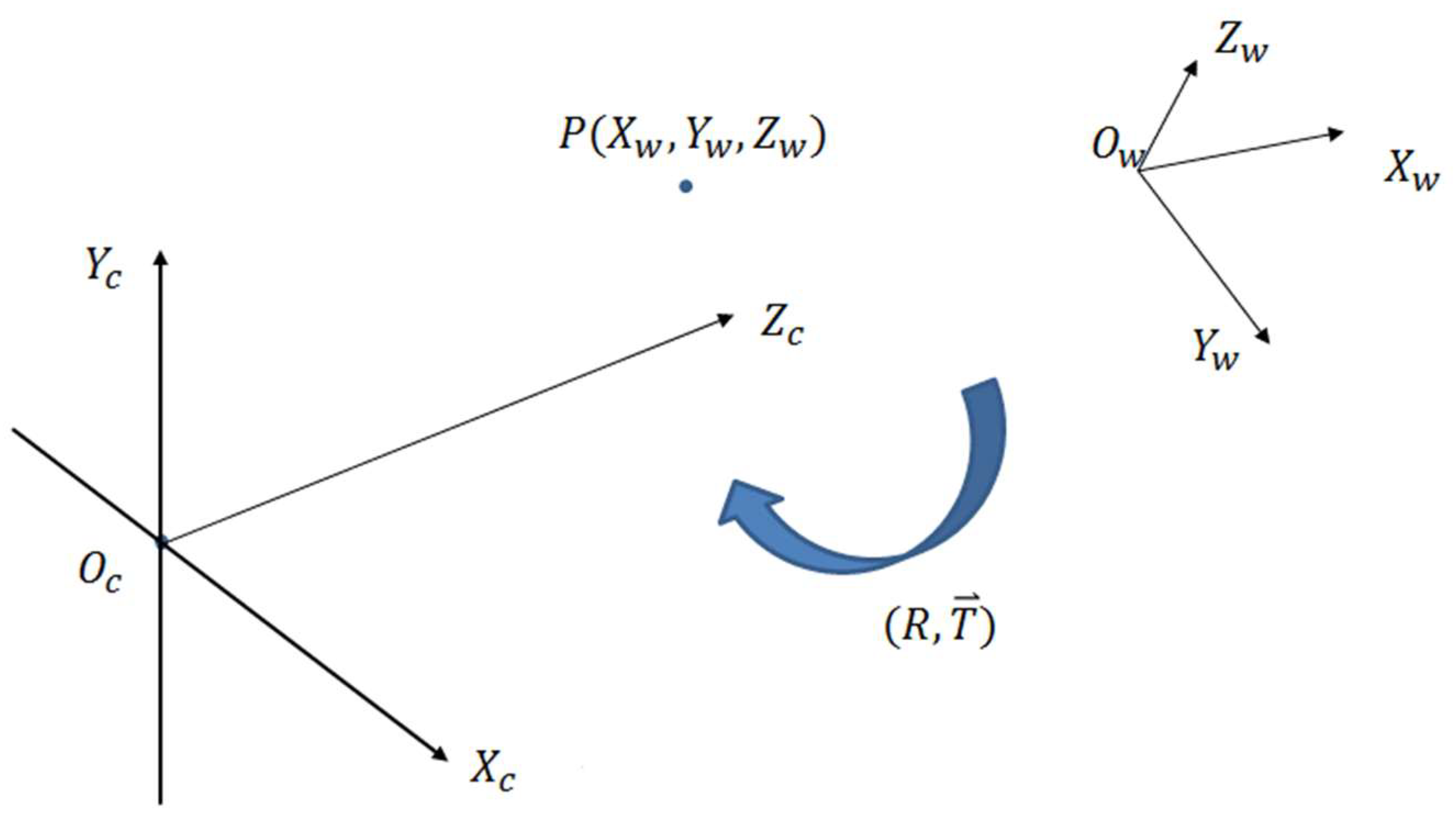

3. Analysis of Camera Calibration Methods

- (1)

- The conversion of the camera coordinate system to the world coordinate system

- (2)

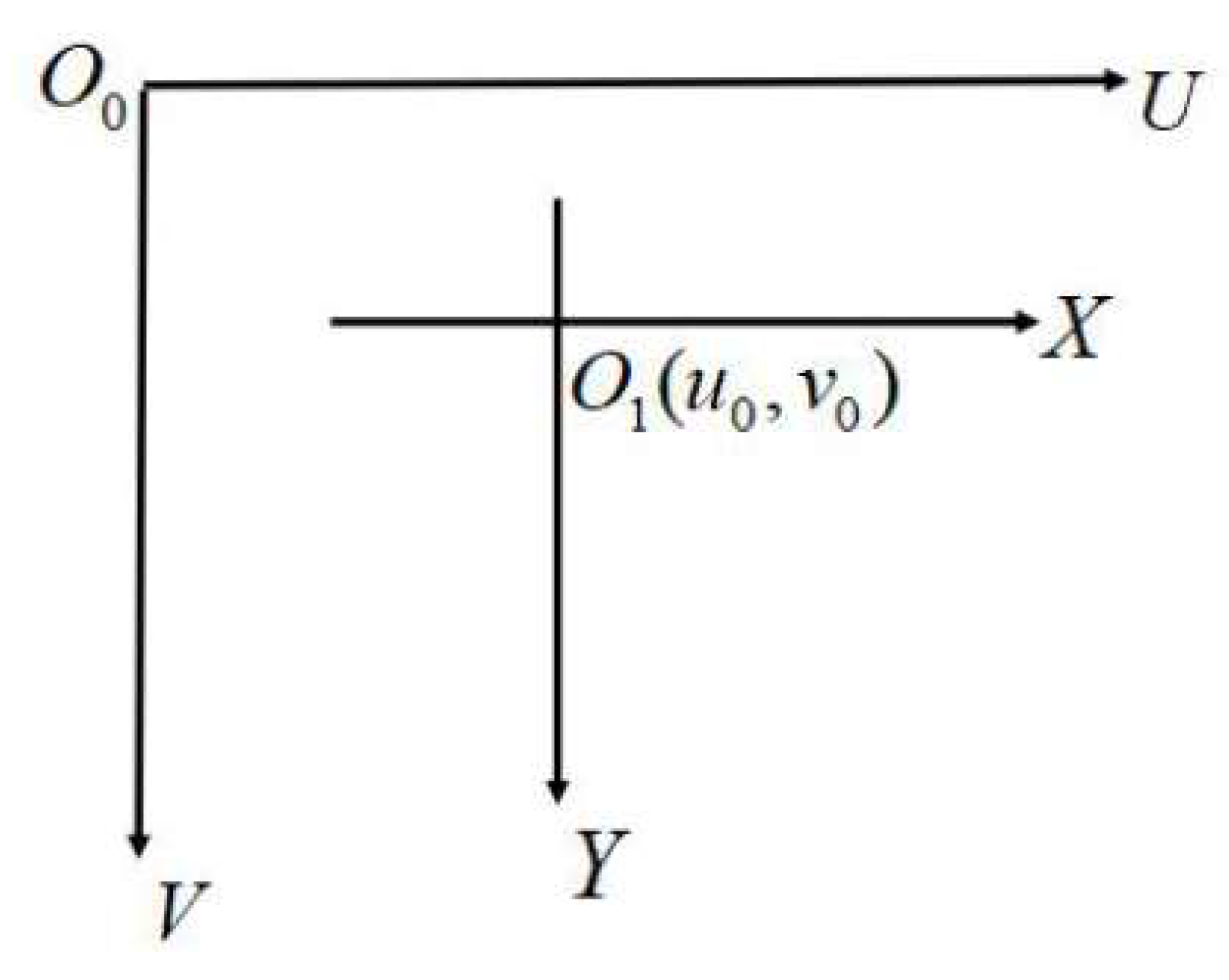

- Conversion of the camera coordinate system to the image coordinate system

- (3)

- Conversion of the image coordinate system to pixel coordinates

- (4)

- Camera calibration results

4. Research on Plate Weld Recognition Based on Deep Learning

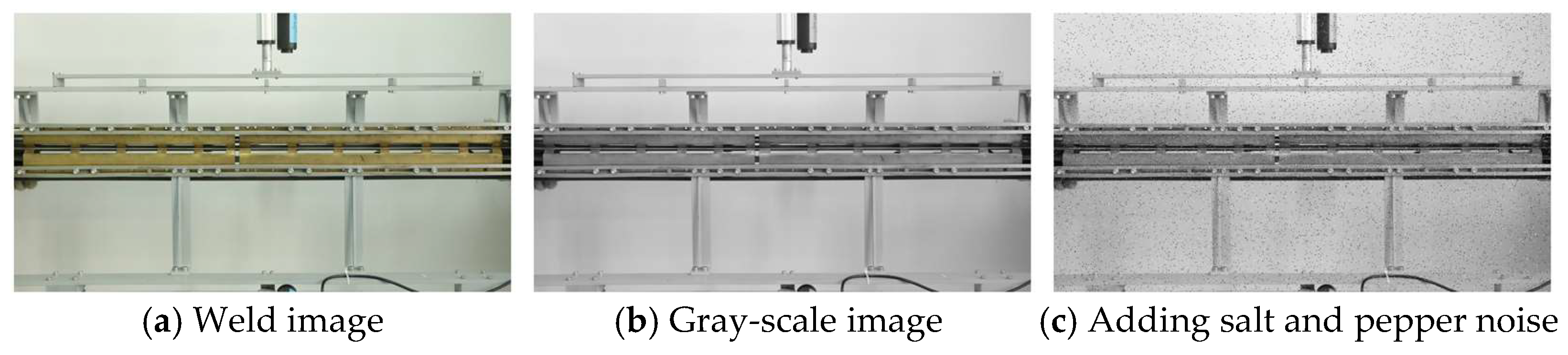

4.1. Preprocessing of Plate Weld Images

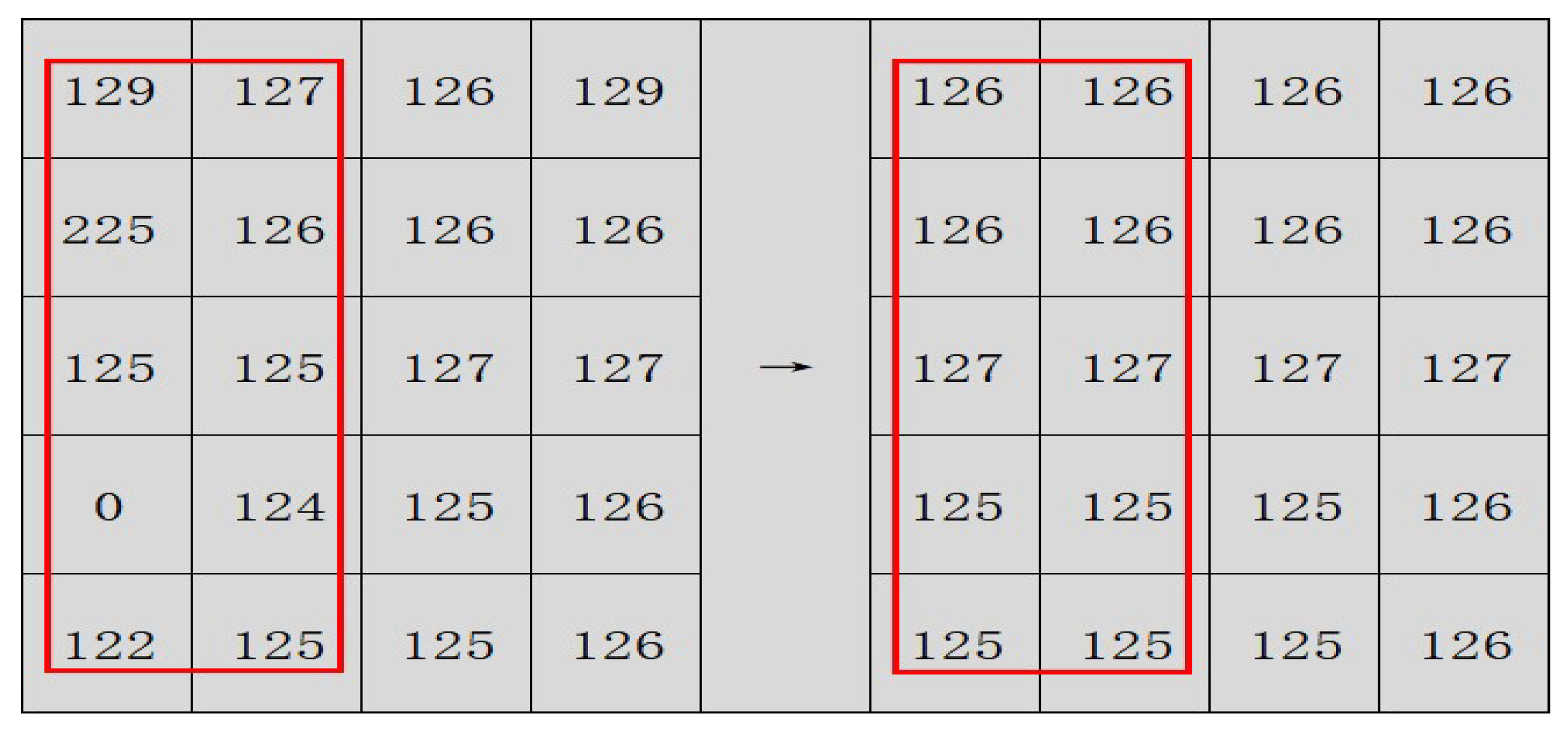

4.2. Plate Weld Seam Image Denoising Processing

4.3. Plate Weld Recognition Based on Deep Learning

4.3.1. Weld Region Localization Based on Deep Learning

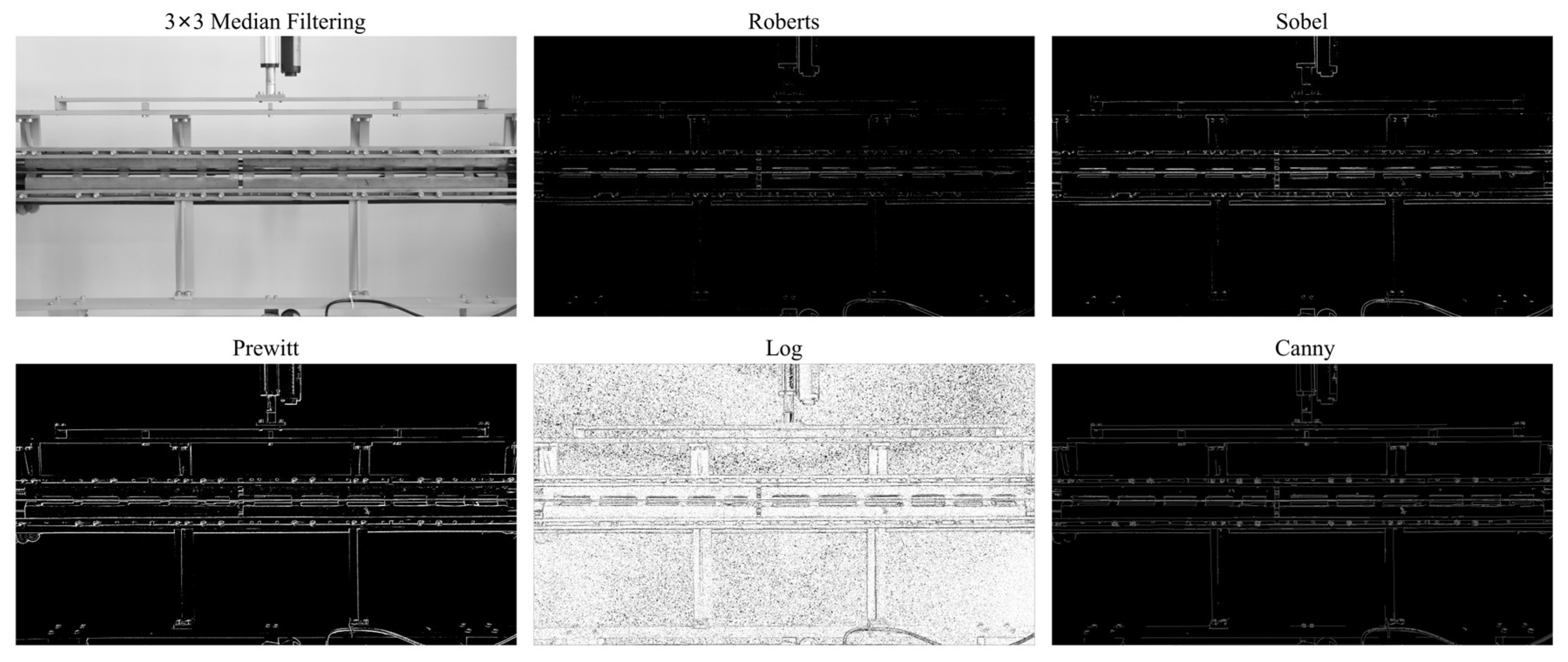

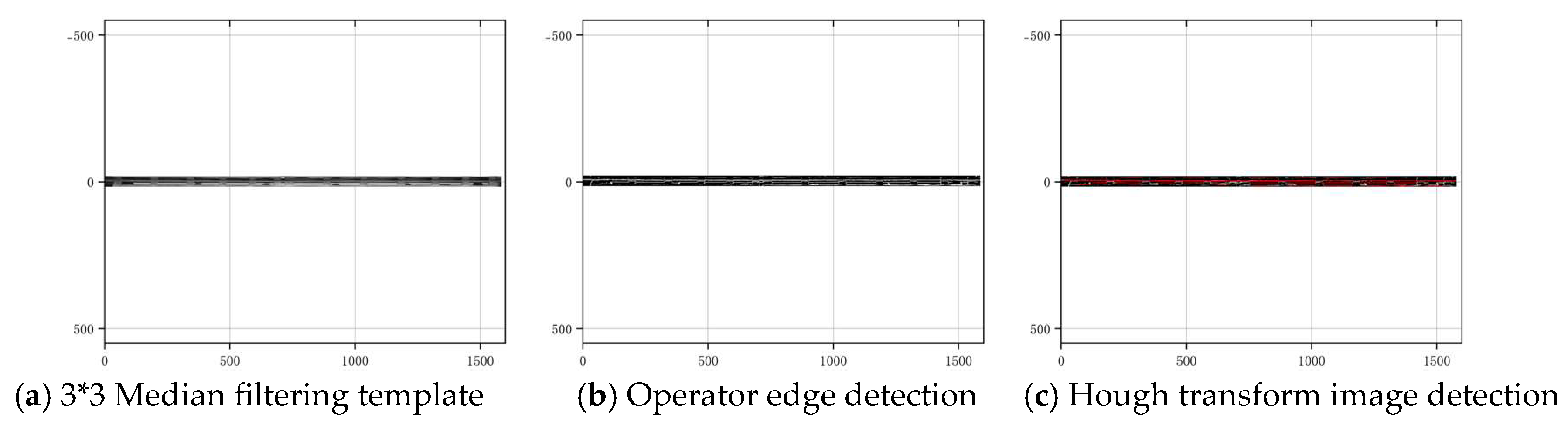

4.3.2. Precise Extraction of Weld Edges Within ROI Regions Based on Optimization Operators

5. The Weld Coordinates of the Plate Are Automatically Generated

5.1. Weld Trajectory Coordinate Generation Process

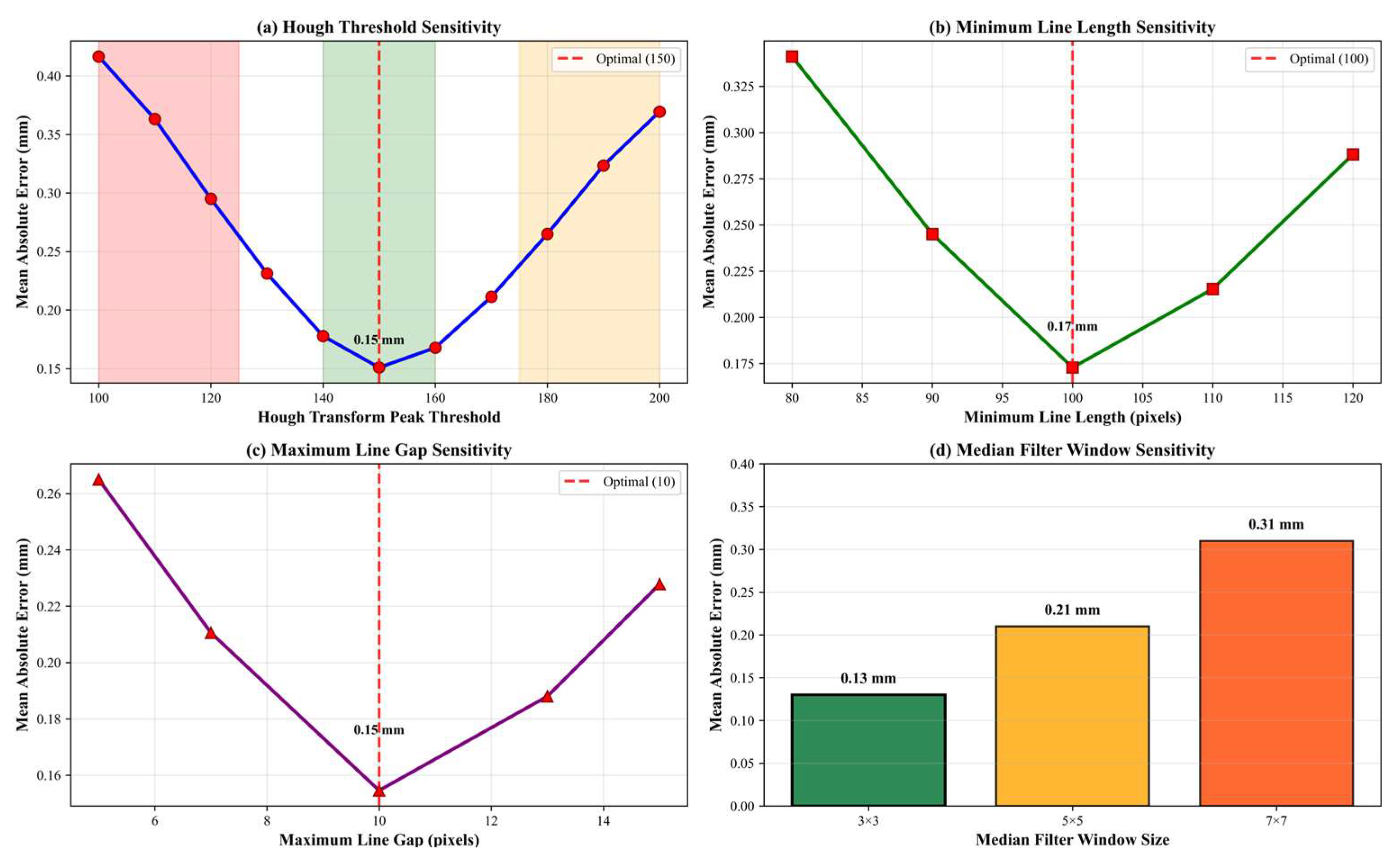

5.2. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

6. Experiments and Results Analysis

6.1. Dataset

6.2. Training Configuration and Parameters

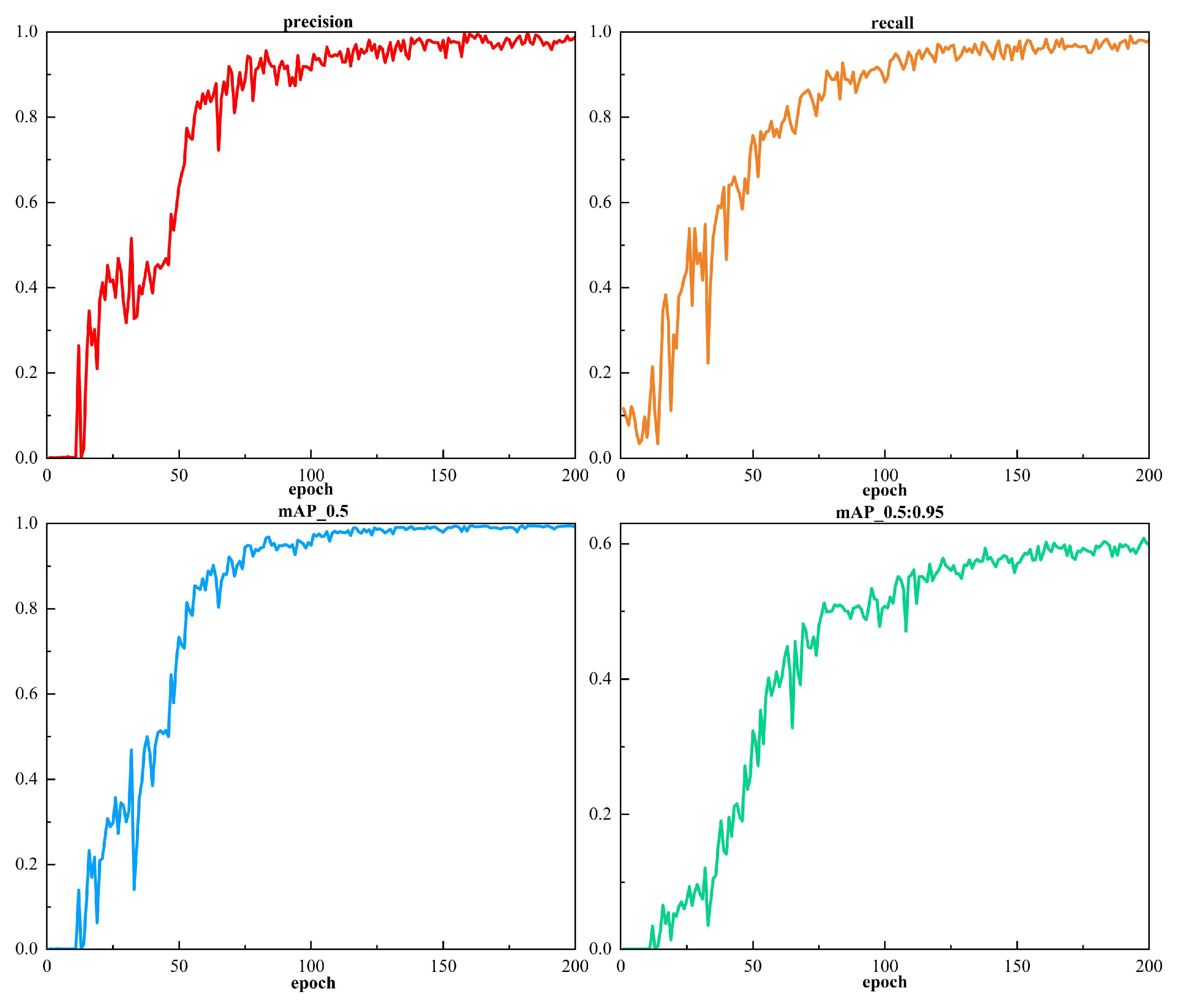

6.3. Training Results

6.4. Weld Area Edge Detection Experiment

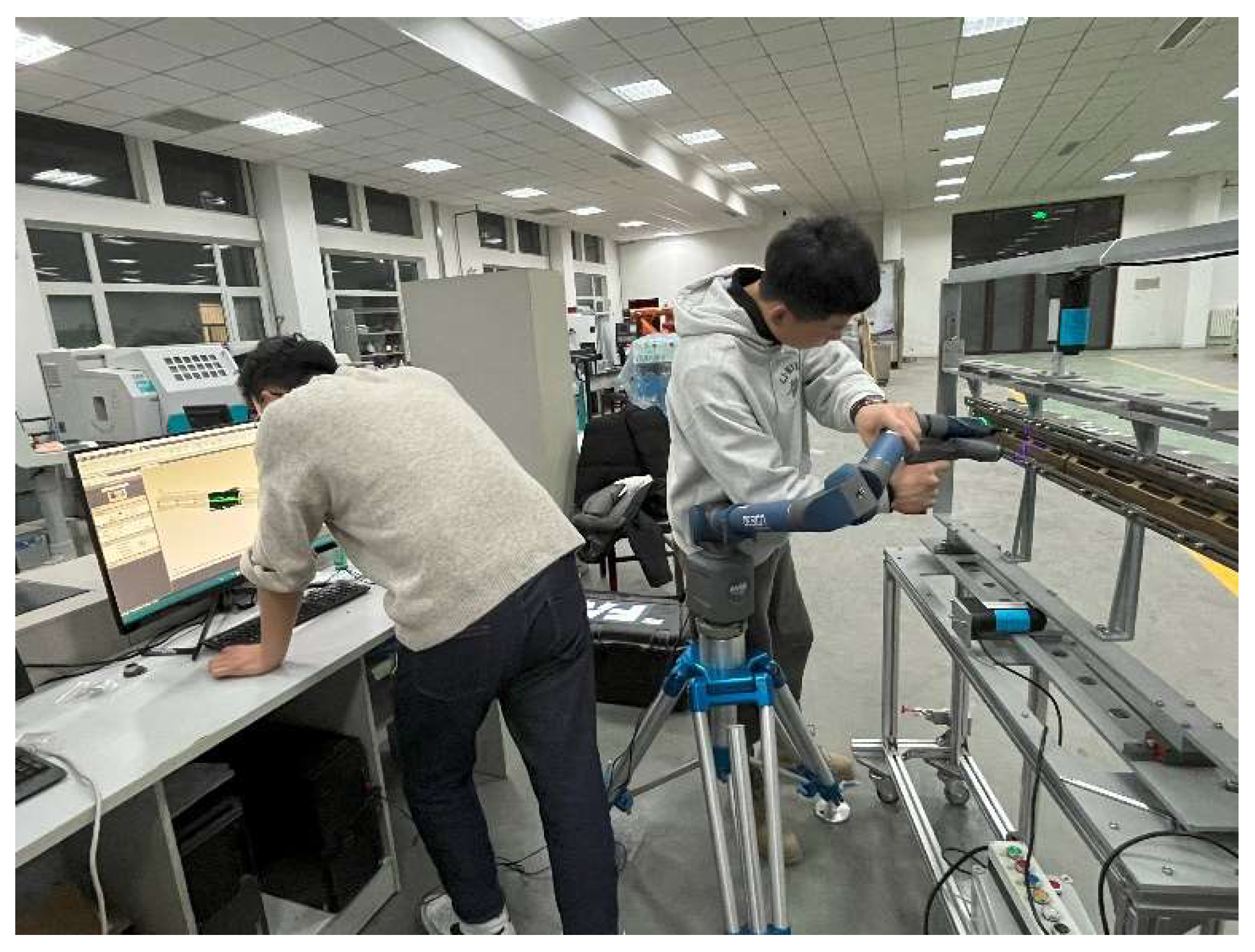

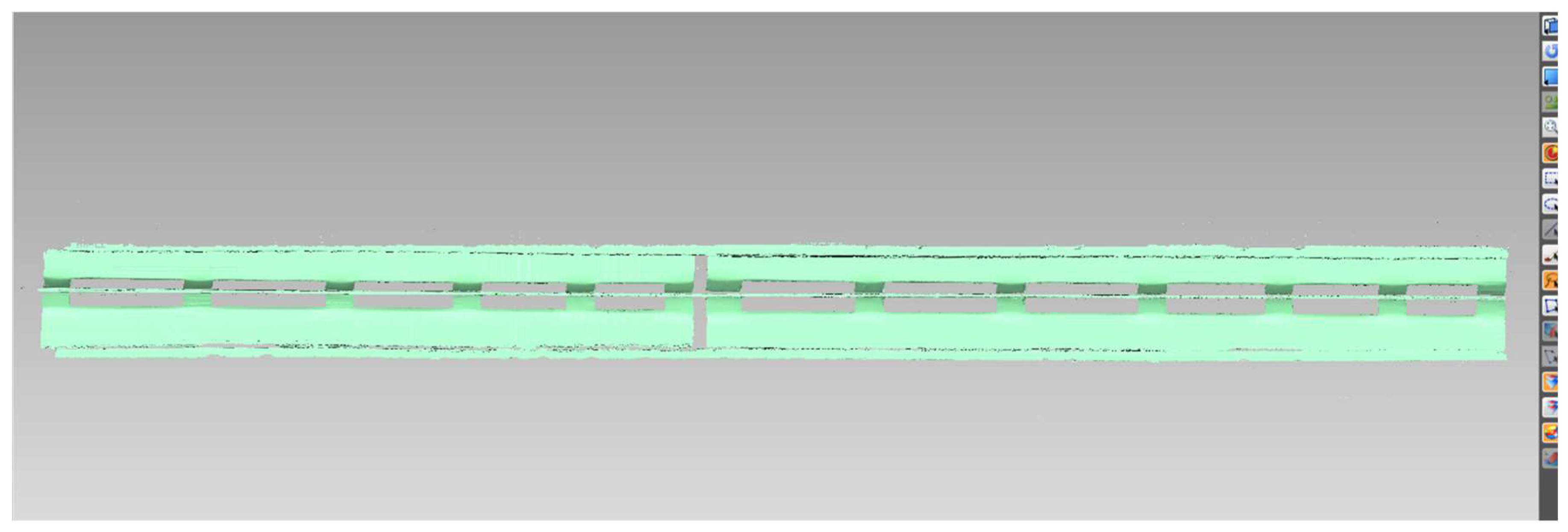

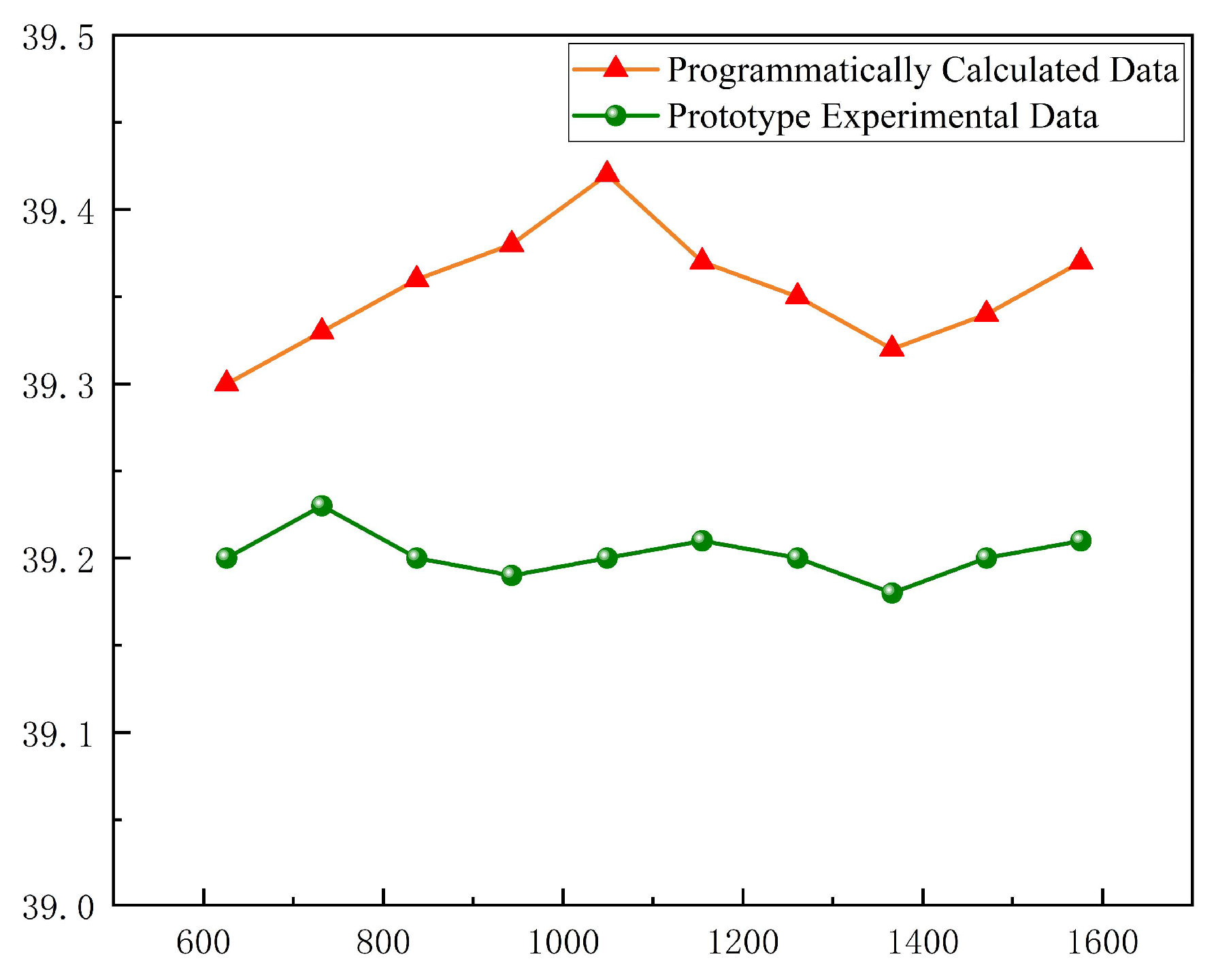

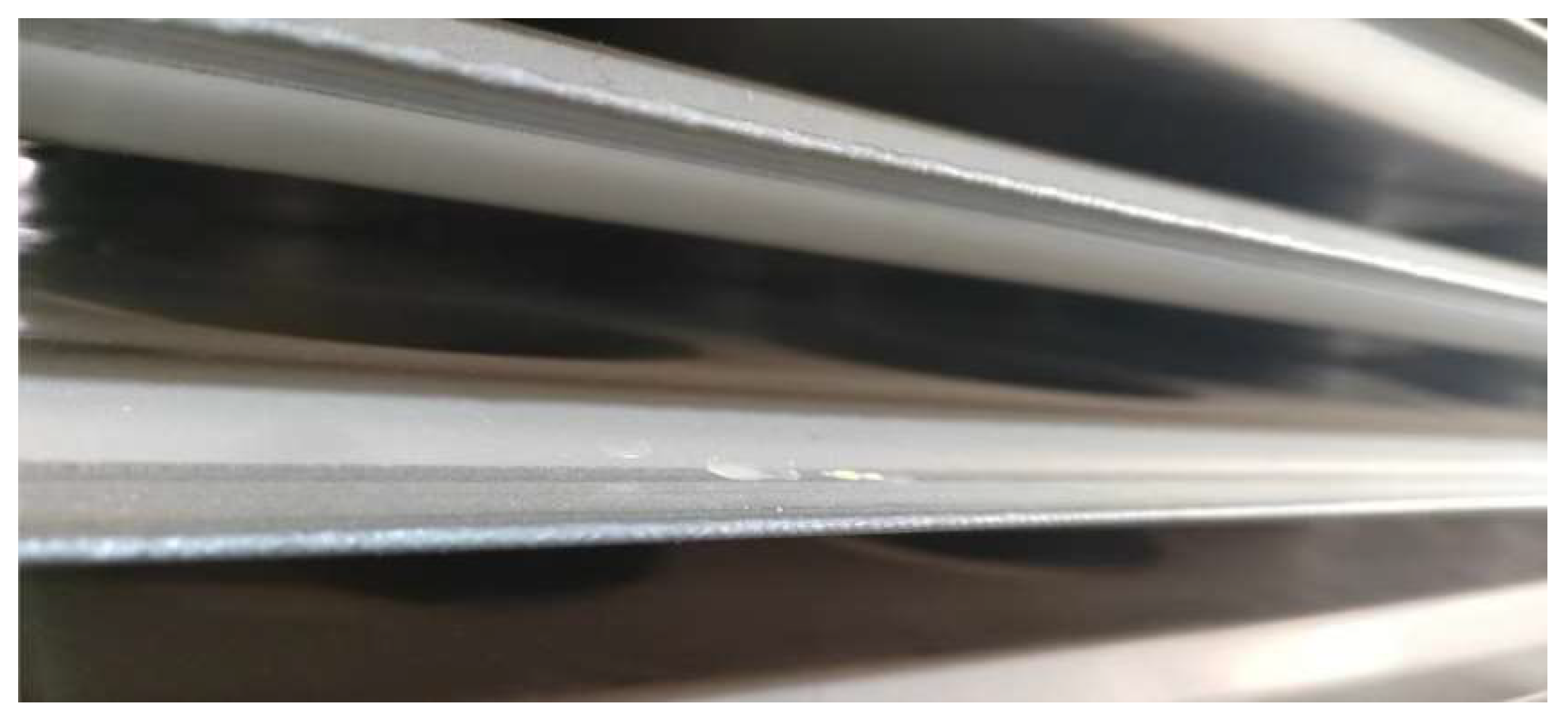

6.5. Experimental Study on Plate Weld Measurement

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- A camera calibration model based on coordinate transformation was constructed, achieving precise camera calibration and image correction, thereby providing data support for establishing the positional transformation of the welding robot. The calibration result showed an average reprojection error of only 0.14 pixels, laying a solid foundation for subsequent high-precision recognition.

- (2)

- A two-stage fusion strategy of “deep learning coarse localization + optimized operator fine detection” was proposed for the intelligent recognition of weld seam image edges. This method uses the lightweight Shuffle-YOLOv8 model to quickly and robustly locate the approximate area of the weld seam, and then applies an optimized Prewitt operator within this ROI for high-precision, high-efficiency pixel-level edge extraction. This strategy significantly reduces the computational load and improves processing efficiency. Experiments demonstrate that the extracted weld trajectory between heat exchanger plates is accurate, with an average error of only 0.33%, meeting the precision requirements for welding.

- (3)

- A weld trajectory coordinate detection and generation program based on the Hough transform algorithm was developed. This solves problems such as the low efficiency of robot teach-based welding and information silos between the recognition and welding systems. It enables high-real-time, high-quality automated weld seam identification and detection for large-format, long-distance heat exchanger plates, ultimately more than doubling the overall welding efficiency.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, N.; Han, C.; Wang, J. Research Review and Application of Printed Circuit Heat Exchanger. Liaoning Chem. Ind. 2023, 52, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Research on Vision Guidance System of Plate Heat Exchanger Feeding Robot Based on 3D Images. Master’s Thesis, China Jiliang University, Hangzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P. Research on Plate Depth Detection System of Plate Heat Exchanger. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang University of Technology, Shenyang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. A Review of the Current Status and Future Trends of Heat Exchangers. China Equip. Eng. 2022, 21, 261–263. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Qin, K.; Wu, H.; Smith, R. A New Computer-Aided Optimization-Based Method for the Design of Single Multi-Pass Plate Heat Exchangers. Processes 2022, 10, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahes, A.L.M.; Bagajewicz, M.J.; Costa, A.L.H. Simulation of Gasketed-Plate Heat Exchangers Using a Generalized Model with Variable Physical Properties. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 217, 119197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Welding Manual: Welding Methods and Equipment; China Machine Press Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Acherjee, B. Laser Transmission Welding of Polymers—A Review on Process Fundamentals, Material Attributes, Weldability, and Welding Techniques. J. Manuf. Process 2020, 60, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Analysis of the Application of Automatic Welding Technology in Mechanical Processing. South. Agric. Mach. 2020, 23, 114–116. [Google Scholar]

- Orłowska, M.; Pixner, F.; Majchrowicz, K.; Enzinger, N.; Olejnik, L.; Lewandowska, M. Application of Electron Beam Welding Technique for Joining Ultrafine-Grained Aluminum Plates. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2022, 53, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yang, L.; Xue, D. Design and Experimental Study of Welding Clamping Device Forheat Exchanger Plates. Res. Mod. Manuf. Eng. 2023, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, Y. The Development of Welding of Dissimilar Material—Aluminum and Steel. J. Chang. Univ. 2011, 2, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Analysis of Impact of Mechanical Design and Manufacturing and Automation Industry under the Background of German Industry 4.0. Times Agric. Mach. 2016, 12, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H. Research on the Transformation Strategies of China’s Manufacturing Industry under the Wave of Industry 4.0. Sci. Technol. Innov. Her. 2017, 16, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Anwer, N.; Liu, A.; Wang, L.; Nee, A.Y.C.; Li, L.; Zhang, M. Digital Twin towards Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J. Research on 3D Profile Detection Methods and Key Technologies for High-End Hydraulic Components Based on Machine Vision; Anhui Jianzhu University: Hefei, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H. Application of Machine Vision Technology in Industrial Inspection. Digit. Commun. World 2020, 12, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Research on Machine Vision Calibration and Object Detection Tracking Methods & Application. Ph.D. Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Zhu, J. Application Status of Visual Imaging Technology for Intelligent Manufacturing Equipment. Mod. Comput. 2021, 27, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Li, Y.; Xia, Q.; Cheng, X.; Chen, W. Research on the On-Line Dimensional Accuracy Measurement Method of Conical Spun Workpieces Based on Machine Vision Technology. Measurement 2019, 148, 106881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Karkhi, N.K.; Abbood, W.T.; Khalid, E.A.; Jameel Al-Tamimi, A.N.; Kudhair, A.A.; Abdullah, O.I. Intelligent Robotic Welding Based on a Computer Vision Technology Approach. Computers 2022, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z. Research on Intelligent Manufacturing Technology of Robot Welding Based on Image Processing. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, W.; Zheng, M.; Yan, J. Industrial Robot Tracking Complex Seam by Vision. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2000, 30, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Li, G.; Ma, P. Seam Image Recognition Preprocessing Based on Machine Vision. J. Guangxi Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 42, 1693–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, T.; Cui, M. Study of Robot Trajectory Based on Quintic Polynomial Transition. Coal Mine Mach. 2011, 32, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Zhang, M.; Hou, J. Research on Trajectory Planning Algorithms for Industrial Assembly Robots. Mod. Electron. Tech. 2019, 42, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y. Research on Welding Technology Based on Vision Guidance of Line Laser Camera. Master’s Thesis, Soochow University, Suzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, M.; Fang, G. Detection of Fillet Weld Joints Using an Adaptive Line Growing Algorithm for Robotic Arc Welding. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2014, 30, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciszak, O.; Juszkiewicz, J.; Suszyński, M. Programming of Industrial Robots Using the Recognition of Geometric Signs in Flexible Welding Process. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimpour, R.; Fesharakifard, R.; Rezaei, S.M. An Adaptive Approach to Compensate Seam Tracking Error in Robotic Welding Process by a Moving Fixture. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banafian, N.; Fesharakifard, R.; Menhaj, M.B. Precise Seam Tracking in Robotic Welding by an Improved Image Processing Approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 114, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampos Loukas, N.; Warner, V.; Jones, R.; MacLeod, C.N.; Vasilev, M.; Mohseni, E.; Dobie, G.; Sibson, J.; Pierce, S.G.; Gachagan, A. A Sensor Enabled Robotic Strategy for Automated Defect-Free Multi-Pass High-Integrity Welding. Mater. Des. 2022, 224, 111424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, M.; Sikström, F. Integrated Vision-Based Seam Tracking System for Robotic Laser Welding of Curved Closed Square Butt Joints. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 3387–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Tang, X.; Li, L. A Visual Sensing Robotic Seam Tracking System. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2008, 42, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Yao, X.; Li, K. Calibration of Binocular Stereo-Vision System. Mech. Des. Manuf. 2010, 6, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wu, F. A Review on Some Active Vision Based Camera Calibration Techniques. Chin. J. Comput. 2002, 25, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; He, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, F. Camera Calibration Approach Using Polarized Light Based on High-Frequency Component Variance Weighted Entropy for Pose Measurement. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 115015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhei, C.; Bogdan, V.; Bonchis, C.; Vasiu, R. Dilated Filters for Edge-Detection Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 12993–13000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Ren, D.; Liu, W.; Ye, R.; Hu, Q.; Zuo, W. Enhancing Geometric Factors in Model Learning and Inference for Object Detection and Instance Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 8574–8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Cheng, F.; Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Mao, T. Detection of Farmland Obstacles Based on an Improved YOLOv5s Algorithm by Using CIoU and Anchor Box Scale Clustering. Sensors 2022, 22, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Calibration Values (pixel) | |

|---|---|---|

| Focal length | 757.6382 | 760.3847 |

| Main point position (u0, v0) | 263.7319 | 270.5986 |

| Pixel coordinate axis Angle | 0 | |

| Distortion coefficient | 0.1802 | −0.2232 |

| Average reprojection error | 0.14 | |

| Name | CPU | GPU | CUDA | Pytorch | PyCharm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model/Version | Intel i5-14600kf | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060ti | 12.4 | 2.4.1 | 2024.1.2 |

| Parameter Names | Training Rounds | Batch Size | Image Size | Initial Learning Rate | Momentum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter value | 200 | 8 | 640 | 0.0006 | 0.9 |

| Point | Horizontal Coordinate/mm | Vertical Coordinate/mm | Average Value of the Vertical Coordinate/mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 625.85 | 39.20 | 39.22 |

| 2 | 731.61 | 39.23 | |

| 3 | 837.43 | 39.20 | |

| 4 | 943.03 | 39.19 | |

| 5 | 1049.07 | 39.20 | |

| 6 | 1154.76 | 39.21 | |

| 7 | 1260.96 | 39.20 | |

| 8 | 1366.04 | 39.18 | |

| 9 | 1471.07 | 39.20 | |

| 10 | 1576.11 | 39.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, F.; Huang, M.; Wang, N.; Li, L.; Yang, X. Intelligent Recognition of Weld Seams on Heat Exchanger Plates and Generation of Welding Trajectories. Machines 2025, 13, 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13110992

Xie F, Huang M, Wang N, Li L, Yang X. Intelligent Recognition of Weld Seams on Heat Exchanger Plates and Generation of Welding Trajectories. Machines. 2025; 13(11):992. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13110992

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Fuyao, Mingda Huang, Neng Wang, Linyuxuan Li, and Xianhai Yang. 2025. "Intelligent Recognition of Weld Seams on Heat Exchanger Plates and Generation of Welding Trajectories" Machines 13, no. 11: 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13110992

APA StyleXie, F., Huang, M., Wang, N., Li, L., & Yang, X. (2025). Intelligent Recognition of Weld Seams on Heat Exchanger Plates and Generation of Welding Trajectories. Machines, 13(11), 992. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13110992