Abstract

Automated valet parking (AVP) is a key component of autonomous driving systems. Its functionality and reliability need to be thoroughly tested before road application. Current testing technologies are limited by insufficient scenario coverage and lack of comprehensive evaluation indices. This study proposes an AVP testing and evaluation framework using OnSite (Open Naturalistic Simulation and Testing Environment) and Unity3D platforms. Through scenario construction based on field-collected data and model reconstruction, a testing scenario library is established, complying with industry standards. A simplified kinematic model, balancing simulation accuracy and operational efficiency, is applied to describe vehicle motion. A multidimensional evaluation system is developed with completion rate as a primary index and operation performance as a secondary index, which considers both parking efficiency and accuracy. Over 500 AVP algorithms are tested on the OnSite platform, and the testing results are evaluated through the Unity3D platform. The performance of the top 10 algorithms is analyzed. The evaluation platform is compared with CARLA simulation platform and field vehicle testing. This study finds that the framework provides an effective tool for AVP testing and evaluation; a variety of high-level AVP algorithms are developed, but their flexibility in complex dynamic scenarios has limitations. Future research should focus on exploring more sophisticated learning-based algorithms to enhance AVP adaptability and performance in complex dynamic environment.

1. Introduction

Autonomous vehicles are currently at a critical stage of transitioning from pilot demonstrations to large-scale commercial deployment. Before commercialization, their safety and reliability need to be comprehensively tested. Current testing methods mainly include simulation, closed-field, and open-road testing. Among them, simulation offers distinct advantages such as high efficiency, safety, replicability, and low cost. It serves over 90% of autonomous vehicle tests [1] and plays a key role in the development and commercialization of autonomous vehicles [2].

There are a variety of autonomous driving simulation platforms with different features worldwide. For example, vehicle dynamics simulation software (such as CarSim 2023.2, CarMaker9.0) is capable of building high-precision vehicle dynamics models but is relatively weak in sensor modeling and scenario editing. Traffic flow simulation software (e.g., VISSIM2022, SUMO1.20.0) excels in simulating urban traffic environments and management strategies but lacks detailed vehicle dynamics and sensor models. Assisted and autonomous driving system platforms (e.g., PanoSimv33, PreScan2307, VTD2022.4, CARLA0.9.13) and other industrial simulation testing software (e.g., 51Sim One3.1.2, Apollo9.0.0, TADSIM 2.0) are characterized by their rich sensor and environmental models and high-degree-of-freedom scenario editors [3]. Testing and evaluation are an important process during the development of autonomous driving systems, serving as the foundation for technical validation to ensure system safety and reliability. For various functional modules in autonomous driving systems, testing protocols and evaluation criteria shall be designed to address their unique operational conditions [4].

Automated valet parking (AVP) is regarded as a Level 4 autonomous driving technology that addresses the challenge of “last-mile freedom” for end users [5]. As a key part of autonomous driving, it holds significant commercial value and has received intensive attention in academia and industry. Currently, AVP remains in demonstration and testing stages. Its functional maturity and commercialization continue to face technical challenges [6]. Within multi-obstacle and unstructured parking environments, path planning is a main function of AVP technology and is also a research focus. For example, a distributed control method is introduced for coordinating multiple vehicles. Via a vehicle-to-infrastructure communication interface, the model predictive control decisions of vehicles and coordinates in the parking area management system are shared [7]. A model predictive control method is proposed, which considers different supply and demand patterns, parking resource utilization rates, and traffic conditions. This method enables the determination of the optimal dispatch rate and the development of a route guidance method for autonomous vehicles [8]. Overall, a variety of AVP algorithms are developed. Their evaluation criteria are relatively simple and lack a multidimensional evaluation method, making it difficult to evaluate the overall performance in real-world scenarios.

Vehicle dynamics simulation can accurately capture vehicle motions and become a major testing tool for AVP [9]. It supports the construction of various scenarios, such as perpendicular, parallel, and angled parking within a multi-obstacle environment, enabling repeated test-and-optimize parking algorithms [10]. CarSim is applied to simulate regular traffic flow and stop-and-go traffic conditions on highways [11]. A vertical parking scenario for a semi-trailer is set up using TruckSim2023.2 software, and its algorithm is verified by randomly generating obstacles [12]. PreScan is employed to simulate driving environments, and a simulator is built to evaluate driving assistance systems focusing on passenger–vehicle–road interactions [13]. However, testing under complex and dynamic conditions remains limited, and the lack of comprehensive evaluation metrics constrains the applicability of these approaches.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a framework of AVP testing and evaluation using OnSite (Open Naturalistic Simulation and Testing Environment) and Unity3D2022.3.53f1c1 platforms. The framework is built upon a scenario library constructed using field-collected data and simulations, enabling the reconstruction of dynamic testing environments. A simplified kinematic model considering both accuracy and operational efficiency, is implemented to describe vehicle motion. A multidimensional evaluation system is introduced considering both parking completion rate and performance. This approach aims to enable an effective and holistic assessment of AVP system performance in real-world scenarios.

2. OnSite Platform

The OnSite platform [14] intends to advance the testing and validation of the state-of-the-art technologies in autonomous driving. It integrates four key testing components: scenario generation, methodologies, evaluation methods, and performance metrics. Based on advanced testing methodologies, controllable evaluation methods are incorporated to achieve closed-loop services from testing to evaluations. Since 2023, yearly autonomous driving algorithm testing has been hosted by the National Natural Science Foundation of China using the OnSite platform to facilitate technical exchanges and promote the development and adoption of new technologies. At present, the construction of the first phase of the OnSite platform has been completed, and significant progress has been made in development of testing and evaluating technologies for autonomous driving. The next phase of development focuses on virtual–real fusion testing technologies and interconnection and interoperability of different platforms.

In addition to platform development and testing, many studies applied OnSite to conduct advanced research on autonomous driving. For example, the OnSite library of system-under-test (SUT) and scenarios serves as a condensed test suite framework. The framework reduces redundant scenarios while preserves test complexity and diagnostic power, accelerating multi-SUT benchmarking and validation [15]. The performance of planning and control methods is tested using OnSite and the results identify limitations of the state-of-the-art methods under highly interactive conditions [16]. New datasets derived from OnSite can fill gaps in vulnerable road user coverage and support trajectory prediction, motion planning, and mixed traffic testing [17,18]. These studies indicate that OnSite serves as not only a standardized testbed for algorithms but also as a rich resource that supports methodological innovation in scenario condensation, interaction-aware benchmarking, and dataset construction.

Using OnSite, this study intends to identify and address the limitations of current AVP algorithms through rigorous benchmarking, diagnostic analysis, and performance-based evaluation. Based on evaluation results, strategies are proposed to enhance algorithm robustness and adaptability. This effort aims to enrich and standardize AVP testing scenarios, unify evaluation criteria, and establish parking protocols.

3. Framework of AVP Testing and Evaluation

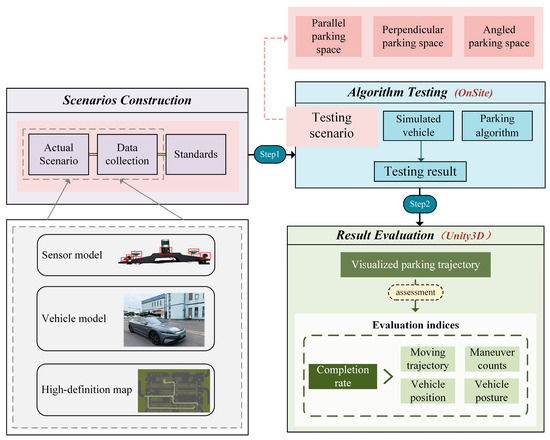

A framework was developed to test and evaluate AVP technologies during the third OnSite autonomous driving algorithm testing in 2025. As shown in Figure 1, the testing and evaluation workflow consists of three modules: scenario construction, algorithm testing and result evaluation. The scenario construction module employs sensors and vehicles to collect data to construct a library of testing scenarios, complying with industry standards. The testing module generates virtual simulation environments that interact with vehicle models and automatic parking algorithms using OnSite platform in a Python 3.8 programming environment. After testing is completed, the evaluation module collects data related to vehicle status and posture and inputs the data into Unity3D platform for visualization and evaluation of the performance of parking algorithms. The performance is evaluated primarily based on completion rate, and secondarily on four key performance indicators, including trajectory, maneuver counts, vehicle position, and vehicle posture.

Figure 1.

Automatic parking testing and evaluation.

3.1. Scenario Construction

The key to simulation testing is to build a virtual scenario that is highly similar to field conditions. Although standard regulations on automatic parking have been issued in many countries, the test scenarios in these regulations are relatively simple and limited, for example, lacking the square column parking spaces commonly found in underground parking spaces. To enrich testing scenarios, this study builds a scenario library through the process of real data collection, modeling, and restoration. As shown in Figure 2, a self-developed data collection platform is developed with vehicle-equipped LiDAR and other sensors to collect high-definition point cloud data in parking spaces. The vehicle is equipped with a LiDAR, six cameras, an image acquisition card, an industrial computer, a drive-by-wire system, a display, and some other in-vehicle devices. Through filtering, denoising, segmentation, and data annotation, key features such as parking space boundaries, parking lines, and columns are extracted. Point cloud registration and geometric reconstruction algorithms are then applied to accurately rebuild the physical environment, achieving a one-to-one simulation restoration of parking scenes.

Figure 2.

Parking space data collection: (a) data collection platform; (b) parking lot point cloud data.

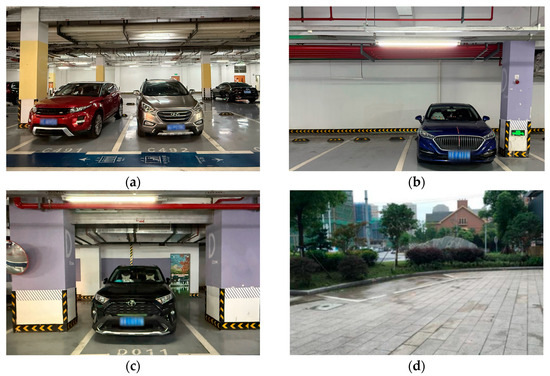

Through reconstruction, four parking scenarios are simulated and added to the existing testing database, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. The four scenarios are vertical parking spaces with a square column on the left side, vertical parking spaces with a square column on the right side, vertical parking spaces with a square column on both sides, and parallel parking spaces along a curved roadway.

Figure 3.

Illustration of four field parking scenarios: (a) vertical parking space with square column on left side; (b) vertical parking space with square column on right side; (c) vertical parking space with square columns on both sides; (d) parallel parking space on curved road.

Figure 4.

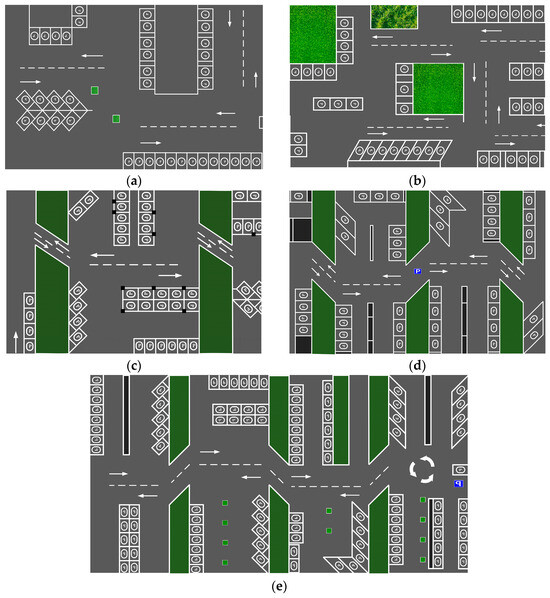

Test scenarios (Sets A, B, C): (a) Set A; (b) Set B (01); (c) Set B (02); (d) Set B (03); (e) Set C.

Table 1 compares our scenario database with those in widely used standards, including: ISO 16787 “Intelligent Transport Systems-Assisted Parking Systems (APS)-Performance Requirements and Test Procedures” [19], GB/T 41630-2022 “Performance Requirements and Test Methods for Intelligent Parking Assistance Systems” [20], and IVISTA-SM-IPI.PA-TP-A0-2023 “Intelligent Parking Index—Parking Assistance System Test Procedure” [21]. The comparison shows that our database includes all the scenarios covered by other standards and provides more scenarios than others.

Table 1.

Comparison of different standard parking test scenarios.

Three test sets, A, B, and C, are designed as shown in Figure 4. Each set generally covers three classes of parking spaces and ten scenarios but has different number of parking spaces and difficulties.

Set A is relatively simple. It consists of 50 parking spaces, mainly simulating daily parking scenarios. There are no moving obstacles in the parking area. It is fully public and used for training by participants. Participants can use parking spaces in Set A to test and improve their algorithms. The performance of algorithms on this test set is not scored.

Set B consists of 3 subsets, B (01) with 53 spaces, (02) with 49 spaces and (03) with 98 spaces, with a total of 200 parking spaces. Static obstacles, moving vehicles and walking pedestrians are designed along certain driving paths to increase parking difficulty. It is fully public. Participants are allowed to submit their algorithm to Set B tests multiple times. During the multiple tries, they can improve their algorithm continuously. The highest score during the multiple tries is chosen as the final score for Set B.

Set C consists of 80 parking spaces. All parking spaces are designed with static obstacles, moving vehicles and walking pedestrians along the driving path, focusing on testing the real-time motion planning and quick response of AVP algorithms. The obstacles are all designated as impassable objects, and if a vehicle hits an obstacle, it is considered a collision accident. Pedestrians and vehicles move along fixed trajectories at a constant speed of 0.8 and 1.5 m/s, respectively. Set C is non-public. Participants test their algorithms on this set of parking spaces, and the performance of the algorithms is scored. The final score of each participating team is calculated as a weighted sum of 70% from Set B and 30% from Set C.

3.2. Vehicle Motion Modeling

To track the path and describe the motion of vehicles during parking process, a simplified vehicle kinematic model is built. The parking process primarily involves low-speed, small-scale vehicle movement. It is assumed that wheels only perform rolling and steering movements, without lateral slip. Figure 5 shows the vehicle model. The vehicle rear axle midpoint (x, y) is chosen as driving trajectory reference point; V is the rear axle midpoint speed; r is the turning radius; θ is the vehicle heading angle; l is the wheelbase; and the corresponding front wheel turning angle is:

Figure 5.

Vehicle kinematic model.

The discretized kinematic model is described as

where t is the sampling time.

The model, although simplified, is able to catch the key motion characteristics of a vehicle during parking. It simplifies the computational process and improves operational efficiency, while ensuring accuracy and facilitating rapid evaluation and optimization of parking algorithms.

3.3. Evaluation Indices

To evaluate the performance of parking algorithms, a holistic evaluation system is developed that integrates real-time monitoring data of vehicle state throughout the parking process. The parking completion rate is chosen as a primary index for evaluation, as it directly reflects the system’s ability to execute the test. The completion rate is calculated as the number of successful completions of parking over the number of total parking spaces in each testing set. A parking process is considered a successful completion if the vehicle is moved into the boundaries of a designated parking space. In addition, four supplementary indices are designed to consider parking efficiency and accuracy. The efficiency is defined by two indices: moving trajectory and maneuver counts, and the accuracy is described by vehicle position and posture after parked.

The performance of each algorithm is first evaluated by the completion rate of each test set, and teams with higher completion rates are ranked higher. In case some teams obtain same completion rates, they are then ranked by a performance score, which is calculated from the average score of all successfully completed tests. Any form of vehicle collision or failure to park in the designated spaces is considered a failure, and the score is not calculated.

The total score of a completed parking, S, consists of two parts: the efficiency score with a maximum of 60 points, and the accuracy score with a maximum of 40 points. S is expressed as

considers the parking path length and maneuver count , both of which are closely related to energy and time consumption during a parking process. is expressed as

is scored based on the ratio of the reference distance, to the actual distance, , and is capped to 30 points. The shorter the actual distance is and the higher the score is.

is scored based on,

where is the maneuver counts with a minimum value of 1. Specifically, one maneuver refers to a single operation that changes the vehicle’s driving state, starting from when the vehicle stops in a parking space to when it restarts. For instance, moving forward counts as one maneuver or shifting gears to reverse counts as one maneuver. The highest 30 points are obtained if a parking process is completed after one maneuver, and 3 points will be deducted for each additional operation until 0.

consists of scores from vehicle position and posture , and is expressed as

is scored based on the offset, , between the vehicle and parking space center, measured in meters (m). A full score of 20 points is assigned to with 0 offset, and 3 points are deducted for every 0.02 m offset until 0. is expressed as

is scored based on the angle deviation, of the head of parked vehicle, measured in degrees (°). It has a full score of 20 points with 0 deviation, and a deduction of 3 points for every 0.5-degree difference until 0. It is expressed as

The detailed scoring system is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Scoring system for completed parking.

3.4. An Application Example

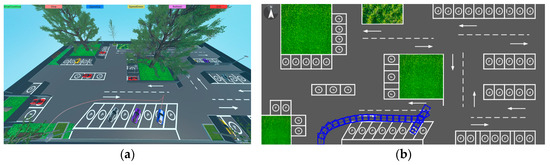

To validate the effectiveness of the evaluation method, the study conducts a hardware-in-the-loop (HiL) simulation experiment using the Hybrid A* algorithm with the Unity3D platform on a parking space in Set B (2). The experimental platform and results are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Experimental platform and results: (a) 3D simulation platform; (b) experimental results.

As shown in Figure 6a, the 3D simulation scenario is produced on Unity3D platform. The platform is used to reconstruct the geometric, kinematic and perceptual characteristics of the physical testbed and to provide a deterministic, real-time environment for HiL validation. The parking geometry, lane markings and surrounding obstacles are modeled to metric scale and mapped to a common Cartesian reference frame. Virtual encoders, inertial measurement unit and range sensors are implemented to reproduce the interfaces and noise characteristics of the physical hardware. The movable camera on the Unity3D platform allows for real-time observation of vehicle operation. Simulation execution (start, pause) and speed scaling are all achieved through graphical user interface buttons.

In Figure 6b, the blue curve represents the vehicle driving trajectory, while the blue rectangles denote the vehicle positions at various time steps during maneuver. The vehicle is modeled with a length of 4.5 m, width of 2 m, and wheelbase of 3.5 m, with a maximum front wheel steering angle of 34°. The parking space is 6.5 m in length and 2.5 m in width. To evaluate the robustness of parking algorithms under varying parking slot dimensions, the slot sizes are defined as a baseline value plus a random variable. Specifically, the parking space width is sampled using this method: .

Vehicle posture is represented in the form (x/m, y/m, θ/rad), where x and y denote the coordinates of the vehicle rear axle center, and θ represents the vehicle heading angle. The initial pose of the vehicle is set to (30, 2, π/2), and the target pose is (74, 5.8, 2π/3). According to the evaluation methodology, the final score achieved by the parking algorithm is 94.2 points. The score details are as follows: the actual path length was 68.43 m, compared to the reference length of 82.8 m, obtaining 24.2 points for the “parking path length” metric; only one forward maneuver was conducted during the entire process, yielding a full score of 30 points for the “maneuver count” metric; as the rear axle center of the vehicle aligned precisely with the center of the parking spot and no heading angle deviation is observed, the “position and posture” metric received a full score of 40 points. These results not only demonstrate the reliability of the Hybrid A* algorithm in handling parking tests but also validate the effectiveness of the scoring system developed in this study.

4. Discussion on Testing Results

Over 40 teams attended this test. They provided about 500 algorithms and tested over 200,000 individual parking spaces. The organizing team provided more than 300 online support sessions and over 1200 instances of remote debugging assistance. Participants continuously improved their algorithms, increasing the average test completion rate from less than 20% at the outset to 87% by the end of the competition. This process significantly saved cost associated with the development of automated parking systems, and, at the same time, enhanced the testing and evaluation capability of the OnSite platform.

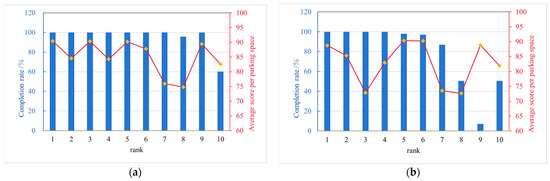

The completion rate and average score of the top 10 teams are presented in Figure 7. The 10 teams are ranked with completion rate as the primary evaluation indicator. In the case of the same completion rate, they are ranked based on the average score. For example, the first four groups all have a completion rate of 100%, so they are ranked according to the average score, 70% for Set B and 30% for Set C.

Figure 7.

Completion rate and average parking space score: (a) Set B; (b) Set C.

Figure 7a,b shows that the completion rate at test Set B is much higher than that of Set C. Among the 10 teams, 8 reached a 100% completion rate at Set B compared with 4 at Set C. This is because Set B tests are fully open and are allowed multiple submissions from participants, while Set C tests are non-public and more difficult. Each team can only have a try for each parking space in Set C. Figure 7a,b also shows that the completion rate and average score for each team are not consistent. Some teams can obtain high completion rate but acquire low score (e.g., team 3 at Set C), while some teams have a high score but low completion rate (e.g., team 9 at Set C). This fact indicates that different algorithms have their own strengths and weaknesses, and the evaluation framework proposed in this study can test different characteristics of algorithms. It is rational to use the completion rate as the primary index to ensure the algorithm can complete the test while using the overall score to capture the effectiveness and accuracy of algorithms.

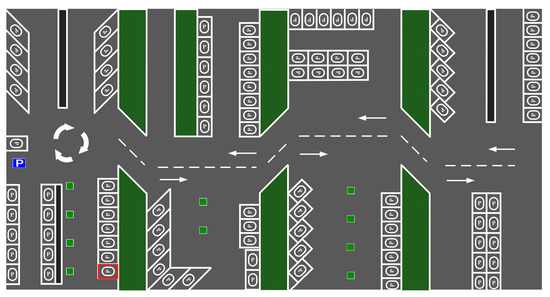

According to analysis, the parking space in the red box in Figure 8 has the lowest completion rate. The unique aspect of this parking space is the obstacles that are situated right in front of it, near the parking spot and the boundary of the parking area. It significantly increases the difficulty for parking algorithms to plan feasible trajectories. The obstacles not only constrain the available drive-in paths but also impose a substantial computational burden during trajectory searching, thereby impacting parking efficiency and success rates. Such scenarios are commonly encountered in real-world, particularly in busy urban streets or crowded parking lots. Under these conditions, AVP algorithm requires precise environmental perception capabilities to accurately identify parking space information and dynamic planning abilities to generate feasible trajectories in real time.

Figure 8.

Parking space with the lowest completion rate in Set C.

The testing and evaluation show that a variety of high-level AVP algorithms are developed, but they are still not very flexible in complex situations. The conventional hybrid A* algorithm is currently the primary AVP technique used by the top four teams. Although it exhibits high stability and dependability, it is unable to meet sophisticated autonomous driving requirements due to its limited performance in handling complex or narrow parking spaces. This limitation is mostly caused by the relatively poor adaptability to dynamic environments of current algorithms. Future research should focus on exploring more sophisticated learning-based algorithms, such as deep reinforcement learning and end-to-end approaches, which can continuously learn and self-optimize to enhance adaptability and control performance in complex dynamic scenarios.

5. Comparison with CARLA Simulation Platform and Field Vehicle Testing

CARLA is an open-source simulation platform developed under the guidance of the Computer Vision Center at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain. It is widely used for the development, training, and validation of autonomous driving systems. Its flexible API allows users to customize scenarios, add sensors and vehicle models, and adjust environmental conditions to meet diverse testing requirements.

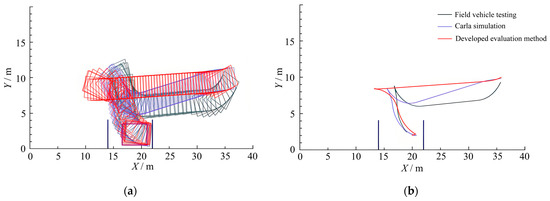

Real-world data of a ground-level parking lot in Suzhou, China, were collected to create a simulation environment and verify algorithm consistency. An X86 system environment and a modified BYD Han DM with LiDAR and camera sensors were used in the real-vehicle test platform. The autonomous driving vehicle and the CARLA simulation platform are displayed in Figure 9. The hybrid A* algorithm was used to control experimental variables on the actual vehicle, the CARLA platform, and the developed evaluation method. The same scenario was used for parking tests, and Figure 10 shows the results.

Figure 9.

CARLA simulation platform and autonomous driving platform vehicle: (a) CARLA simulation platform; (b) field vehicles.

Figure 10.

Comparison of CARLA simulation platform, field vehicle testing and developed evaluation method: (a) vehicle posture comparison; (b) vehicle trajectory comparison.

Figure 10 shows that, in general, the driving path and vehicle trajectory of the three methods are highly similar, except that the trajectory of CARLA and the real vehicle is relatively smoother, while that of the developed evaluation method exhibits a sharper change when switching from forward to backward. The main reason for this discrepancy is that the CARLA simulation platform and field vehicle testing utilize more complex vehicle dynamics models, which can more accurately catch vehicle dynamic response at varying speeds and steering angles, exhibiting a smooth transition during directional changes. The developed evaluation method applies a relatively simple kinematic model, ignoring many key factors in vehicle dynamics, such as the delay of the steering system and the mechanical properties of tires under different road conditions. As a result, the simulation performance of the developed evaluation method in complex scenes is relatively rough, especially with abrupt trajectory changes during rapid changes in direction. This comparison demonstrates the importance of incorporating complex dynamics models to improve simulation accuracy. It will be a future research direction and potential improvement in the development of OnSite platform.

6. Conclusions

Testing and evaluation are important processes during the development of autonomous driving systems, serving as the foundation for technical validation to ensure system safety and reliability. This study develops an AVP testing and evaluation framework using OnSite and Unity3D platforms.

The testing is conducted on the OnSite platform, which features a diverse testing scenario library, built through vehicle-collected data and model reconstruction and complied with industry standards. The performance is evaluated using a multidimensional evaluation system with completion rate as a primary index and operation performance as a secondary index. The evaluation is conducted on the Unity3D platform for visualization. The framework is applied to test and evaluate the performance of over 500 AVP algorithms, demonstrating its effectiveness in testing and evaluating. The evaluation results show that a variety of high-level AVP algorithms are developed, but they are still not very flexible in complex situations. This limitation is mostly caused by the relatively poor adaptability to dynamic environments of current algorithms.

Future research will focus on three key directions: scene interactivity, improving the virtual–real fusion testing system, and expanding parking scenarios. The current scenario library primarily covers typical static and dynamic parking scenarios. In the future, we will add more interactive elements, such as changes in weather conditions, lighting conditions, road conditions, and traffic signals, to enhance scenario diversity. Secondly, we will further construct a closed-loop evaluation system combining simulation, HiL, and real-vehicle testing to improve the reliability and transferability of evaluation results. Finally, we will consider more parking scenarios, such as vehicles queuing for parking, vehicles searching for available parking spaces, and collaborative interactions between vehicles, to further improve the generalization and accuracy of the AVP testing and evaluation framework.

Author Contributions

O.C.: Conceptualization, analysis, and drafting. L.C.: Data curation and analysis. J.Y.: Visualization and validation. H.S.: Visualization and analysis. L.X.: Conceptualization and editing. H.L.: Methodology and investigation. W.L.: Supervision and review. G.H.: Analysis and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant number BK20231197 and BK20220243); Science and Technology Program of Suzhou (grant numbers SYG2024057 and SYC2022078); Hubei Science and Technology Talent Service Enterprise Project (grant numbers 2023DJC084 and 2023DJC195); Hubei Science and Technology Project (grant number 2024BAB087); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62303343). Additionally sponsored by Tsinghua-Toyota Joint Research Institute Interdisciplinary Program.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available in the OnSite platform at https://www.onsite.com.cn/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the fundings supporting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Weike Lu was a part-time researcher at the company (Jiangsu JD-Link International Logistics Co.) and declared no conflict of interest. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVP | Automated Valet Parking |

| OnSite | Open Naturalistic Simulation and Testing Environment |

| HiL | Hardware-in-the-loop |

References

- Liu, G.; Hu, Y.; Xu, C.; Mao, W.; Ge, J.; Huang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xia, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Toward Collaborative Autonomous Driving: Simulation Platform and End-to-End System. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 6566–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Zheng, S. Enhanced Automated Valet Parking System Utilizing High-Definition Mapping and Loop Closure Detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabani, H.; Pujol, R.; Alcon, M.; Moya, J.; Abella, J.; Cazorla, F.J. ADBench: Benchmarking Autonomous Driving Systems. Computing 2022, 104, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lee, M.; Hwang, K.; Ha, Y. End-to-End Deep Learning-Based Autonomous Driving Control for High-Speed Environment. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 1961–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Tang, A.; Hai, J.; Yuan, F. Simulation Model and Performance Evaluation of Automated Valet Parking Technologies in Parking Lots. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2025, 144, 103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, H. A Bi-Level Cooperative Operation Approach for AGV Based Automated Valet Parking. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 128, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneissl, M.; Madhusudhanan, A.K.; Molin, A.; Esen, H.; Hirche, S. A Multi-Vehicle Control Framework With Application to Automated Valet Parking. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 5697–5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liao, F.; Li, X.; Du, Y. Macroscopic Modeling and Dynamic Control of On-Street Cruising-for-Parking of Autonomous Vehicles in a Multi-Region Urban Road Network. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 128, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Sohn, J.H.; Min, H.G.; Kim, Y.J. Identification of Operational Limitations of an Autonomous Vehicle Based on Dynamic Simulation. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 6519–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, B.; Doba, D.; Tettamanti, T. Optimizing Vehicle Dynamics Co-Simulation Performance by Introducing Mesoscopic Traffic Simulation. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2023, 125, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cheng, C.; Hu, J.; Jiang, J.; Chang, T.; Wei, H. Strategy and Evaluation of Vehicle Collision Avoidance Control via Hardware-in-the-Loop Platform. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasagasioglu, S.; Kilicaslan, K.; Atabay, O.; Güney, A. Vehicle Dynamics Analysis of a Heavy-Duty Commercial Vehicle by Using Multibody Simulation Methods. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 60, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Shi, K.; Cai, J.; Chen, L. Trajectory Planning and Optimisation Method for Intelligent Vehicle Lane Changing Emergently. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 12, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ni, Y.; Miao, C.; Sun, J.; Sun, J. A Multiagent Social Interaction Model for Autonomous Vehicle Testing. Commun. Transp. Res. 2025, 5, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Q.; Ni, Y.; Sun, J.; Tian, Y. Condensed Test Scenario Library for Highly Automated Vehicles. Automot. Innov. 2025, 8, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Hang, P.; Xiong, L.; Sun, J. InterHub: A Naturalistic Trajectory Dataset with Dense Interaction for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.18302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, X. Virtual Tools for Testing Autonomous Driving: A Survey and Benchmark of Simulators, Datasets, and Competitions. Electronics 2024, 13, 3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, J.; Hang, P.; Sun, J. OnSiteVRU: A High-Resolution Trajectory Dataset for High-Density Vulnerable Road Users. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.23365. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 16787:2017; Intelligent Transport Systems—Assisted Parking System (APS)—Performance Requirements and Test Procedures. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- GB/T 41630-2022; Intelligent Connected Vehicles—Automated Valet Parking System—Performance Requirements and Test Methods. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- IVISTA-SM-ICI.CA-TP-A0-2023; Cruise Assist System Test Protocol (Version 2023). China Intelligent Vehicle Index: Chongqing, China, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).