Abstract

The hydrogen energy industry is rapidly developing, positioning hydrogen refueling stations (HRSs) as critical infrastructure for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Within these stations, hydrogen compressors serve as the core equipment, whose performance and reliability directly determine the overall system’s economy and safety. This article systematically reviews the working principles, structural features, and application status of mechanical hydrogen compressors with a focus on three prominent types based on reciprocating motion principles: the diaphragm compressor, the hydraulically driven piston compressor, and the ionic liquid compressor. The study provides a detailed analysis of performance bottlenecks, material challenges, thermal management issues, and volumetric efficiency loss mechanisms for each compressor type. Furthermore, it summarizes recent technical optimizations and innovations. Finally, the paper identifies current research gaps, particularly in reliability, hydrogen embrittlement, and intelligent control under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions. It also proposes future technology development pathways and standardization recommendations, aiming to serve as a reference for further R&D and the industrialization of hydrogen compression technology.

1. Introduction

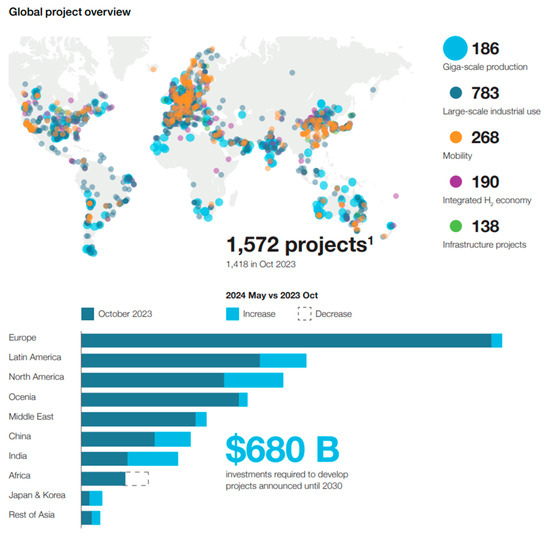

At present, countries around the world are confronted with tremendous environmental pressure and an energy crisis where non-renewable fossil energy is gradually being exhausted [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In 2024, global energy demand is affected by extreme temperatures. The global cooling days (an indicator of cooling demand) in 2024 were 6% higher than those in 2023 and 20% higher than the long-term average from 2000 to 2020 [7]. Regions with high refrigeration demands are particularly affected [8,9], including China, India, and the United States. Extreme hot weather has increased energy demand [10,11,12]. Global energy demand grew by 2.2% in 2024, significantly faster than the average annual growth rate of 1.3% from 2013 to 2023 [7]. The continuous expansion of energy demand forces us to seek a renewable, green, and pollution-free energy sources to replace traditional fossil energy [13,14,15]. Hydrogen energy, as a renewable and high-energy-density clean energy source, is demonstrating its unique advantages—being environmentally friendly and having a high energy conversion efficiency. It is expected to replace traditional fossil energy in the near future [16,17]. In terms of investment scale and the number of projects, the global hydrogen energy industry has announced 1572 hydrogen projects, with an investment of 680 billion US dollars expected by 2030, among which gigabit projects account for more than half, with an investment of over 380 billion US dollars [18]. Figure 1 shows the distribution and investment situation of global hydrogen energy projects.

Figure 1.

Distribution and investment scale of hydrogen energy projects that have been announced globally as of 2024 [18].

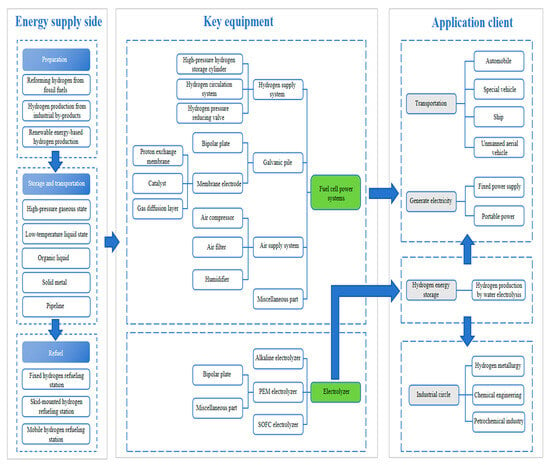

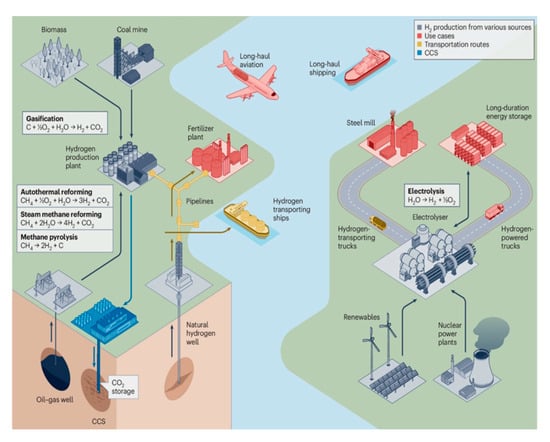

The hydrogen energy sector holds great potential for development, and it is expected that the hydrogen energy industry will become a pillar industry in the future energy system [19,20,21]. The hydrogen energy industry chain is mainly divided into three main parts: the energy end, the key equipment end, and the application end [22,23]. Figure 2 is a schematic diagram of the hydrogen energy industry chain. On the energy end of the hydrogen energy industry chain—hydrogen production, storage, transportation, and refueling—the sources of hydrogen are diverse. They are mainly divided into green hydrogen (produced by electrolyzing water using renewable energy), blue hydrogen (industrial by-products), and gray hydrogen (from fossil fuels) [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Figure 3 shows the global supply and demand relationship of hydrogen energy. The application of hydrogen involves multiple fields. It is used in transportation (such as cars, special vehicles, and ships) [34], power generation and energy storage [35], and industrial fields (such as metallurgy and chemical industry) [36]. Although the transportation field, including fuel cell electric vehicles, is a key area for hydrogen application and an important driving force for demand [37,38], this study is conducted in the context of broader hydrogen production, storage, transportation, and refueling.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the hydrogen energy industry chain, encompassing three main segments: the energy end, key equipment, and the application end.

Figure 3.

A schematic diagram illustrating the dynamic supply and demand of global hydrogen energy. The left side (supply) section classifies the methods of hydrogen production. The demand-side section shows the main consumption areas and their interrelationships [3].

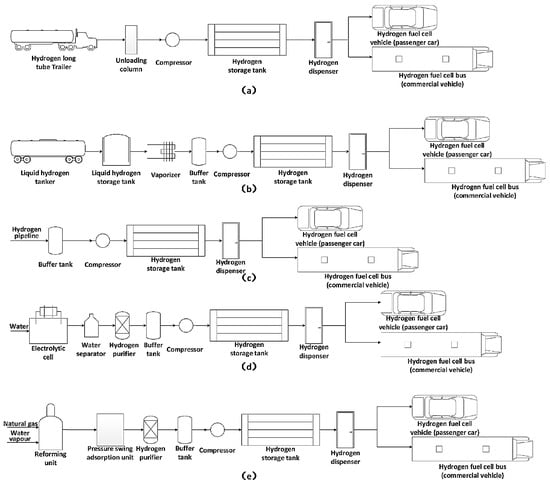

HRSs are one of the most crucial and prominent links in the hydrogen energy application chain, and they are especially crucial for supporting fuel cell vehicles [39,40]. As shown in Figure 4, a typical hydrogen refueling station consists of four main systems: the hydrogen unloading system, pressurization system, hydrogen storage system, and hydrogen refueling system [41,42]. Throughout the entire chain, the hydrogen compressor, as the core equipment of the pressurization system, is responsible for pressurizing hydrogen for storage and refueling. Its performance, reliability, and service life directly determine the operational efficiency, economic feasibility, and safety of the hydrogen refueling station. Therefore, the focus of this review is precisely on this key equipment.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of different hydrogen supply chain paths for fuel cell vehicles, including on-site production and subsequent transportation after off-site production. The core components of HRS are highlighted.(a–c) show routes of the hydrogen supply chain of HRS with external hydrogen supply. (d,e) show routes of the hydrogen supply chain of HRS with internal hydrogen production. [43].

Figure 5a shows the growth in the number of hydrogen refueling stations in various regions from 2022 to 2024. As of June 2024, the number of hydrogen refueling stations in operation worldwide was close to 1200, showing a slight increase. Among them, China topped the list with 400 seats, followed by Europe with 280, South Korea with 180, and Japan with over 170. Figure 5b shows the ratio of fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) to hydrogen refueling stations in various regions from 2020 to 2024. During this period, the ratio of fuel cell vehicles to hydrogen refueling stations in regions such as China, Japan, and Europe remained basically stable. In South Korea, due to the increase in vehicle sales and the construction of approximately 50 new hydrogen refueling stations, the ratio was maintained at around 200 FCEVs per hydrogen refueling station. However, due to the closure of several hydrogen refueling stations in California, USA, local FCEV users are facing difficulties in refueling their vehicles, especially since the ratio of FCEVs to HRS exceeded 300 in 2023.

Figure 5.

(a) The growth trend of the number of operating HRSs in major regions worldwide (China, Europe, South Korea, Japan, and the United States) from 2022 to June 2024. (b) The proportion of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEV) corresponding to each hydrogen fueling station in these regions from 2020 to 2024 [44].

Figure 6 shows the distribution of the number of review articles on hydrogen energy published globally from 2010 to 2023. Hydrogen production and storage are the main research fields, accounting for the majority of the total number of articles, approximately 94.79%, while hydrogen transportation and compression account for a relatively low proportion, especially in the field of hydrogen compression, which only makes up 0.21%. This indicates that there is relatively little research on the field of hydrogen compression at present. Therefore, it is very important to study hydrogen compression, and hydrogen compressors play a crucial role in hydrogen compression.

Due to the physical property of low volume density of hydrogen and the high purity requirements of hydrogen in fuel cell systems [45,46], the structure and working principle of hydrogen compressors play a very crucial role. Hydrogen compressors are broadly categorized into two types: mechanical and non-mechanical. Mechanical hydrogen compressors primarily achieve gas compression through positive displacement or dynamic principles. This review focuses on positive displacement compressors based on reciprocating action, which include the diaphragm compressor, the hydraulically driven piston compressor (a subtype of reciprocating piston compressors), and the ionic liquid compressor. It is noteworthy that while linear compressors are also mechanical, they fall outside the scope of this paper. Table 1 lists some of the more classic review studies on hydrogen compressors and points out their review contents and compressor types. It is not difficult to find that there are relatively abundant review studies on non-mechanical hydrogen compressors. Among them, some scholars take the broad category of non-mechanical hydrogen compressors as the entry point and comprehensively review the technical status of non-mechanical hydrogen compressors (MHHC, ECHC, AHC, and CCH2); an in-depth discussion was conducted on its working principle, key materials, system design, global R&D progress, performance parameters, advantages and disadvantages, and challenges, with particular attention paid to its application potential and economic considerations in hydrogen refueling stations [47]. Some scholars, taking a certain type of non-mechanical hydrogen compressor as the entry point, have elaborated in detail on its working principle, current research and development status, future development, and challenges [48,49,50,51,52]. In conclusion, there is currently a considerable amount of review literature on non-mechanical hydrogen compressors. It includes both systematic discussions on non-mechanical hydrogen compressors and detailed descriptions of a specific type of non-mechanical hydrogen compressor.

The existing articles on mechanical hydrogen compressors rather one-sidedly discuss a specific type of mechanical hydrogen compressor, such as the following: Tahan et al. elaborated in detail on the application of reciprocating and centrifugal hydrogen compressors in the hydrogen industry [53]; Kermani et al. focused on the selection of ionic liquid in ionic liquid compressors [54]; Giuffrida et al. discussed the application and challenges of diaphragm hydrogen compressors [55]; and Otsubo et al. expounded on the application of mechanical compressors such as reciprocating, screw, and turbine compressors in the hydrogen supply chain [56]. However, there are relatively few review studies that systematically discuss mechanical hydrogen compressors, or they have not been published for a long time.

To quantitatively substantiate this research gap, a complementary literature search was conducted on the Web of Science core collection using the same methodology as Parida et al. [47]. The results reveal a striking disparity: while review articles on “metal hydride hydrogen compressor” number over 35, and “electrochemical hydrogen compressor” exceed 20, combined reviews specifically focusing on “mechanical hydrogen compressor”, “diaphragm compressor” AND “hydrogen”, and “piston compressor” AND “hydrogen” amount to fewer than 10. This represents less than 5% of the total review literature on hydrogen compressors when compared to the non-mechanical types quantified in Figure 6, clearly underscoring the scarcity of systematic reviews in this domain. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a review article from the perspective of mechanical hydrogen compressors to systematically expound the structural composition, working principle, research status, development direction, and challenges of various types of mechanical hydrogen compressors.

Figure 6.

Distribution of the number of published review articles on hydrogen energy worldwide from 2010 to 2023 [47] (Data from the Web of Science database maintained by Clarivate Analytics [57]).

Table 1.

Previous reviews of the literature on hydrogen compressors.

Table 1.

Previous reviews of the literature on hydrogen compressors.

| References (Year) | Summary | Overview of Compressor Types | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kermani et al. (2020) [54] | 1. A comprehensive study on the selection of ionic liquids in ionic liquid compressors is reviewed. 2. The specific criteria for selecting ionic liquids were determined, and the roles of anions and cations, as well as the influence of temperature, were widely reviewed. 3. It is believed that trifluoromethanesulfonyl is the best choice for liquid pistons. | Selection of an ionic liquid for ionic liquid compressors |

| 2 | Tahan et al. (2022) [53] | 1. The progress of compression technology in the field of large-scale hydrogen applications is reviewed. 2. The operating conditions of compressors under different working conditions in the hydrogen industry were analyzed in detail. 3. The advantages and disadvantages of reciprocating and centrifugal mechanical compressors in the application of the hydrogen industry were summarized. | The application of reciprocating and centrifugal compressors in the hydrogen industry |

| 3 | Zhang et al. (2025) [58] | 1. Systematically review the application of hydrogen compressor and frequency conversion technology in hydrogen energy transportation. 2. The product demands and industry applications of frequency conversion technology were summarized, with a focus on promoting leading enterprises and their products in the industry. 3. Indicates the development direction of hydrogen compressors and related frequency conversion technologies: smarter, safer, and more efficient. | The application of hydrogen compressors and related frequency conversion technologies in hydrogen energy transportation |

| 4 | Giuffrida et al. (2025) [55] | 1. The hydrogen application and operational challenges of diaphragm compressors are reviewed. 2. Summarized the core issues that engineers face in enhancing the performance of diaphragm compressors. | The Application and Challenges of Diaphragm Hydrogen Compressors |

| 5 | Li et al. (2020) [59] | 1. The development history and application of air compressors in fuel cell systems are reviewed. 2. Analyze the working state and performance upper limit of the compressor through thermodynamics. 3. The improvement of system efficiency by compressor efficiency is summarized. | The development and application of air compressors in fuel cell systems |

| 6. | Wu et al. (2023) [60] | 1. It is believed that centrifugal air compressors will be the mainstream development direction of fuel cell systems. 2. The current development status and problems were systematically reviewed, and the future development direction was proposed. 3. The durability test of centrifugal compressors was discussed, and the conditions for their life test were provided. | The current development status and trends of centrifugal air compressors in fuel cell systems |

| 7 | Parida et al. (2025) [47] | 1. A thorough summary of non-mechanical compressors was made from their working principles and design challenges, to potential solutions. 2. The relevant key experimental findings were summarized to evaluate the performance of non-mechanical compressors in terms of efficiency, compression speed, and economic feasibility. 3. Affirm the advantages of non-mechanical compressors in hydrogen refueling stations and point out the important research gaps and technical bottlenecks. | Metal hydride, electrochemical, adsorption, and cryogenic system compressors, etc |

| 8 | Zhu et al. (2025) [48] | 1. Elaborate on the structure and working principle of the EHC in detail and conduct a comparative analysis with traditional hydrogen compressors. 2. The research progress of core components such as proton exchange membranes, gas diffusion layers, and catalytic layers of EHC was summarized. 3. The moisture management and toxicity inhibition strategies for membrane electrode assemblies were reviewed, and the challenges faced by EHC and its future development directions were summarized. | Low-pressure electrochemical hydrogen compressor |

| 9 | Myekhlai et al. (2024) [49] | 1. This paper reviews the working principle, adsorption process, porous materials, and the latest research and development achievements of physical adsorption compressors. 2. A physical adsorption compressor based on MOF adsorbent is proposed, which can increase the compression pressure of hydrogen refueling stations to 900 bar. 3. Design a fast-charging, safe, and efficient physical adsorption hydrogen compressor. | Physical adsorption hydrogen compressor |

| 10 | Peng et al. (2022) [50] | 1. The working principle of MHHC, the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of hydrogen compression materials are reviewed, and a design scheme of three-stage MHHC is proposed. 2. The research progress of various grades of MHHC materials was discussed, among which lanthanum-nickel penta-based alloys were used for the first stage of compression, and titanium-chromium dia-based alloys were used for the second and third stages of compression. 3. It mainly summarizes the influence of different alloying elements on hydrogen storage performance, as well as related challenges and future directions. | Metal hydride compressor |

| 11 | Durmus et al. (2021) [51] | 1. The advantages and disadvantages of ECHC and mechanical compressors are compared and analyzed, and ECHC is considered to be the solution to replace the mechanical compressor. 2. The recent research achievements on hydrogen purification methods are reviewed. 3. The working principle of ECHC, the progress of material research and development, and the mathematical modeling methods were summarized. | Electrochemical hydrogen compressor |

| 12 | Lototskyy et al. (2014) [52] | 1. A large number of papers and patent documents on MH hydrogen compressors are reviewed. 2. From the application point of view, the material, structure, and phase equilibrium characteristics of the metal-hydrogen system for hydrogen compression are mainly discussed. 3. Starting from applied thermodynamics, this paper reviews the structure, performance, and application scenarios of MHHC. | Metal hydride hydrogen compressor |

| 13 | Otsubo et al. (2025) [56] | 1. It focuses on elaborating the crucial role of compressor technology in the hydrogen supply chain, as well as the technical difficulties and economic challenges. 2. Compare the application scenarios, energy efficiency, and operational characteristics of reciprocating, screw, and turbine compressors to reveal the adaptability of hydrogen treatment at different stages. 3. It is recommended to adopt life cycle assessment (LCA) to evaluate environmental impacts and optimize the overall performance of the compressor system. | Mechanical compressors such as reciprocating, screw, and turbine types |

As the core equipment of hydrogen storage, transportation, and refueling systems, the performance of hydrogen compressors directly affects the efficiency and safety of hydrogen energy systems. This article systematically reviews the research hotspots and difficulties of hydrogen compressors in recent years, conducts an analysis from three dimensions: hydrogen energy demand, national policies, and domestic and international technological research trends, discusses the key technical challenges of hydrogen compressors in terms of performance analysis, volumetric efficiency, and material compatibility, and based on the current technological status of hydrogen compressors, puts forward suggestions for the development of key technologies of hydrogen compressors. With the aim of providing a reference for the autonomy of hydrogen energy equipment.

2. Strategic Policies Related to Hydrogen Energy

Hydrogen energy has great potential for development, and countries around the world are strongly supporting the progress of the hydrogen energy industry and related technologies. Countries around the world are constantly introducing strategies related to hydrogen energy at a strategic level. Figure 7 shows the years when countries around the world first proposed hydrogen energy-related strategies. As of October 2024, in the past full year, 19 new hydrogen energy strategies have been added globally, with a growth rate of 46.34%, covering more than 84% of countries with energy-related carbon emissions worldwide, mostly focusing on hydrogen production and export [44]. The mainstream policy support measures mainly include direct subsidies, competitive bidding, and tax incentives. The first two measures are more commonly seen in developed countries, while tax incentives are more prevalent in EMDEs. Nearly 100 billion US dollars of public funds have been announced, come into effect, and allocated globally to support hydrogen energy projects, of which 95% of the funds come from developed countries, especially in Europe. Nearly two-thirds of the funds are still in the announcement stage and have not yet been implemented. The supply-side funds are approximately 62 billion US dollars, while the demand-side funds are only 40 billion US dollars, with a difference of nearly 22 billion US dollars between the two.

Figure 7.

Shows the years when various countries first announced their hydrogen energy-related strategies (a) and the proportion of public funds related to hydrogen energy in 2023 (b) [44].

However, at present, the shortcomings of demand-side policies are prominent. The existing policies can only meet the total demand for low-emission hydrogen of 6 million tons per year in 2023, which is only 15–20% of the production target and even lower than what is needed in a carbon-neutral scenario. To stimulate hydrogen demand, countries around the world have successively put forward relevant policies. Table 2 shows the policies released after 2023 to promote hydrogen demand. The United States has approved nearly 1.7 billion US dollars worth of six hydrogen-related projects for industrial demonstration programs, aiming to boost hydrogen demand growth [61]; Japan has released more information about the hydrogen and ammonia cluster support plan, supporting the development of infrastructure covering storage and transportation to meet industrial demands [62]; China, in its planning for the oil refining and ammonia industries, emphasizes the use of renewable hydrogen energy to achieve the goal of energy conservation and emission reduction [63]; Germany has announced tender for a 12.5 GW hydrogen power plant in 2024/2025 and requires the plant to switch to low-emission hydrogen in its eighth year of operation [64]; Australia has allocated 490 million Australian dollars to seven hydrogen energy centers to promote the development of hydrogen energy centers in its remote areas [65]; the South Korean government has launched a 15-year power generation contract, with the technical route being all-hydrogen power generation, hydrogen co-combustion in gas-fired power plants, and ammonia co-combustion in coal-fired power plants. The annual power generation capacity of the project can reach 6.5 TWh/yr [66].

Table 2.

Policy measures announced and implemented after September 2023 to promote hydrogen demand [44].

3. Working Principles and Research Trends of Various Mechanical Hydrogen Compressors

3.1. Diaphragm Hydrogen Compressor

3.1.1. Structure and Working Principle of Diaphragm Hydrogen Compressor

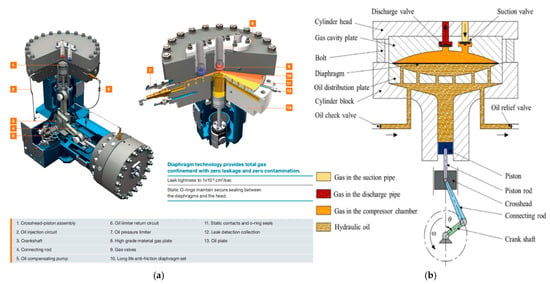

Figure 8 is a structural schematic diagram of an L-shaped diaphragm hydrogen compressor developed by Howden Company. The typical structure of a diaphragm hydrogen compressor is shown in Figure 8b. The main structure is mainly composed of the cylinder block, hydraulic oil distribution plate, diaphragm, gas chamber plate, cylinder head, and related valves. The concave part of the gas chamber plate is inverted in the concave part of the oil distribution plate, separated by a diaphragm in the middle to form the compressed gas chamber and the hydraulic oil chamber. The outermost cylinder head and cylinder block are fixed by bolts. Therefore, the gas cavity plate and the oil distribution plate can be closely attached to prevent gas and oil leakage problems. The working principle of the diaphragm hydrogen compressor is as follows: The crankshaft drive motor drives the crankshaft to rotate. The crankshaft pushes the push rod connected through the crosshead, and the push rod then drives the piston to perform a reciprocating motion. In this way, the hydraulic oil in the hydraulic oil chamber is regularly pressurized and depressurized, causing the diaphragm to reciprocate and bend. Meanwhile, the volume of the compressed gas chamber changes with the movement of the diaphragm, achieving the compression and transportation of hydrogen.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the structural composition of the Howden Diaphragm Hydrogen Compressor. (a) Three-dimensional model diagram. (b) Simple structural diagram [67].

Figure 8 shows the structure diagram of the Howden diaphragm hydrogen compressor, and Figure 9 presents a complete working process of the diaphragm hydrogen compressor. Table 3 lists the types and characteristics of valves used in mechanical hydrogen compressors.

Figure 9.

Shows the working diagram of the diaphragm hydrogen compressor. The oil pressure oil is the orange part, and the compressed gas is the green part. Figures (a) and (f), respectively, show six representative states of the compressor in one working cycle [55].

Table 3.

Types and characteristics of valves used in mechanical hydrogen compressors.

Valve dynamics have a significant impact on the volumetric efficiency and energy consumption of compressors. Delayed valve closure or premature valve opening can lead to backflow, thereby reducing the effective compression effect and increasing power loss. To accurately capture these effects, future simulation models should include a valve sub-model, which needs to consider the following aspects: the spring-mass-damper dynamics of the valve plate, the pressure–force interaction during the opening/closing process, the flow resistance, and leakage in the valve gap. Such a sub-model can be integrated into computational fluid dynamics (CFD) or lumped parameter simulations to predict the real-time valve behavior under different operating conditions.

Figure 9a represents the state at the moment before the compressor’s suction process. At this time, both the intake valve and the exhaust valve of the compressed gas chamber are closed, the metal diaphragm is at the top, dead center, tightly adhering to the top of the compressed gas chamber. Meanwhile, the check valve of the hydraulic oil chamber is closed, and the oil pressure safety valve is open. Due to the imbalance of oil pressure on both sides of the valve body, the hydraulic oil in the oil chamber begins to be discharged. Figure 9b shows the state of the compressor during the suction process. At this time, the intake valve of the compressed gas chamber is open, and the piston starts to move downward, driven by the motor, and the diaphragm also begins to reset. A negative pressure is formed in the compressed gas chamber, and hydrogen is sucked into the chamber. At the same time, the check valve of the hydraulic oil chamber also opens. Due to the expansion of the volume of the hydraulic oil chamber under the influence of the piston movement, it is sucked into the chamber. Figure 9c represents the state when the suction process of the compressor is about to be completed. The piston continues to move downward, causing the diaphragm to bend downward, and, finally, it reaches the bottom, dead center, that is, the position of the bottom attachment of the hydraulic oil chamber. The hydraulic oil through the check valve of the oil chamber mainly fills the expanded oil chamber due to the movement of the piston. Figure 9d shows the state of the compressor during the compression and exhaust process. At this time, both the check valve and the safety valve in the oil chamber are closed, and the piston starts to move upward, increasing the pressure of the hydraulic oil in the oil chamber. The diaphragm begins to return to its original position upward, and the hydrogen is compressed. Meanwhile, the intake valve of the air chamber is closed, and the exhaust valve is open, allowing the hydrogen to be discharged through the exhaust valve. The state of Figure 9f is consistent with that of Figure 9a, except that the state represented by Figure 9a is that of the previous cycle. Due to the existence of Figure 9f, the working cycle process of the compressor can be fully reflected.

3.1.2. Current Development Status and Existing Problems

The Howden Company is the inventor of diaphragm compressor technology. For over a century, it has been dedicated to the research and development of diaphragm compression technology, constantly enhancing the safety and performance of compressors. Among them, the operation of the compressor cannot do without the power transmission and heat dissipation effect of the hydraulic oil. At present, some scholars have studied the influence of hydraulic oil characteristics on the performance of compressors. Long et al. [67] conducted simulations using ANSYS(v2022R1) Fluent and found that increasing the viscosity of hydraulic oil would lead to an extended hydraulic oil discharge time and a shortened exhaust time, thereby reducing volumetric efficiency. They also found that when the hydraulic oil temperature dropped from 50 °C to 10 °C, the flywheel torque increased by 25.84%, the volumetric efficiency dropped to 39.48%, and the radial stress at the diaphragm suction port increased by 43.71 MPa. Ren et al. [68] conducted a systematic study on the influence of hydraulic oil temperature on the performance of a 90 MPa diaphragm compressor. The study found that reducing the oil temperature from 95 °C to 35 °C not only significantly lowered the exhaust temperature by 49 °C but also increased the volumetric efficiency from 36.2% to 43.5%. This phenomenon can be explained from the perspectives of thermodynamics and fluid dynamics: Low-temperature hydraulic oil has a higher density and lower compressibility, reducing the elastic energy loss of the oil during the compression process and thereby enhancing the effective compression stroke. Additionally, the low-temperature oil also helps to reduce the thermal stress on the diaphragm and the wall of the gas chamber, delaying material fatigue. However, excessively low oil temperatures (such as <10 °C) would cause a sudden increase in viscosity and an increase in flow resistance, which might actually reduce the system’s response speed and efficiency [67]. Therefore, in practical applications, the oil temperature control strategy needs to be optimized based on the system pressure and operating frequency. Ren et al. [69] focused on the impact of hydraulic oil compressibility on performance. They found that the compression and expansion of hydraulic oil have a decisive influence on volumetric efficiency. The compressibility of hydraulic oil can lead to a volumetric efficiency loss of approximately 37%, and for every 10 MPa increase in oil spill pressure, the volumetric efficiency decreases by 5%. Zhao et al. [70] found that the suction volume loss caused by hydraulic oil expansion and clearance gas exceeded 40% per volume, reducing the volumetric efficiency by 60%. Secondly, some scholars have carried out structural design and optimization on diaphragm compressors, mainly in three aspects: innovation of cavity profile, design of freely moving pistons, and improvement of the thermal–structural coupling of the cylinder head. Hu et al. [71] proposed a new type of cavity profile busbar based on the compound shape optimization method. Compared with the a-type busbar, the maximum stress and central stress of the diaphragm in the cavity designed by this busbar are reduced by 8.2% and 13.9%, respectively. Jia et al. [72] investigated the influence of a new type of membrane cavity profile generator on the gap volume and flow rate of the compressor cavity. They compared the motion states of three types of membrane cavities defined by busbars and found that the diaphragms of the two new types of membrane cavity profile generators, B and C, would form an additional gap volume of 1.11% and 3.44%, respectively, but the minimum flow rate reduction rate would exceed 4.11%. Li et al. [73] developed a new type of cavity profile busbar. Compared with the traditional cavity, the cavity volume was increased by approximately 10%, the maximum radial force was significantly reduced by 13.8%, and the reduction in the central area of the diaphragm could reach 19.6%. Ren et al. [74] proposed a novel diaphragm compressor design method using a freely moving piston to replace the traditional structure. The highlights of this structural design are as follows: it can achieve the separation of the piston head and the piston rod and form a “zero pressure” state during the suction process. This design method can significantly enhance the volumetric efficiency of the cavity. For a 90 MPa diaphragm compressor, its volumetric efficiency increases from 37% to 66%, while for a 200 Mpa compressor, it rises from 19% to 64%. Wang et al. [75] proposed a thermal–structural coupling method to analyze the deformation and stress distribution of diaphragm compressors, as shown in Figure 10. They evaluated the fatigue life of the cylinder head bolts and, based on this, proposed a structural improvement scheme by increasing the size of the exhaust hole and adding an independent valve seat to reduce the stress of the exhaust hole. Zhao et al. [76] introduced and studied a new type of circumferentially cooled diaphragm hydrogen compressor, as shown in Figure 11. Its structural feature is that the cooling pipe is wound around the exhaust pipe, and part of the pipe is parallel to the suction pipe. They found that the new surround-cooled diaphragm hydrogen compressor had a more significant cooling effect at high pressure than at the conditions, with a maximum temperature reduction of 189.5 ° C.

Figure 10.

Shows the improved structure of the DHC cylinder head (a), the equivalent stress distribution diagram of the exhaust hole (b), and the maximum stress variation curves of the two types of exhaust holes (c) [75].

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of the surrounding cooling channel structure (a), experimental platform (b), and experimental system (c) [76].

The structure of diaphragm hydrogen compressors is complex, and the working conditions are harsh. Even the slightest fluctuation in any parameter can significantly affect the performance, lifespan, and safety of the compressor. Therefore, conducting sensitivity analysis is an indispensable research step. At present, the important research objects of most scholars are factors such as pressure, rotational speed, and pressure ratio. Sun et al. [77] studied the sensitivity analysis based on a two-stage diaphragm compressor. They found that the volume efficiency of the compressor is the most sensitive to the suction temperature, with the sensitivity coefficients of the first and second stages being −2.28 and −1.67, respectively. The shaft power is most sensitive to the rotational speed, with a sensitivity coefficient of 0.976. The isentropic efficiency is most sensitive to the suction temperature of the first stage, with a sensitivity coefficient of −2.059. Zhao et al. [78] conducted sensitivity analyses on suction pressure, overflow pressure, pressure ratio, and rotational speed. They found that isentropic efficiency was mainly affected by factors such as suction pressure, pressure ratio, and rotational speed, while volumetric efficiency was mainly influenced by pressure ratio and rotational speed. Zhao et al. [70] studied the sensitivity analysis of a 90 MPa diaphragm compressor. When = 1.1, the volumetric efficiency and isentropic efficiency of the compressor were the highest. They also found that the volumetric efficiency and isentropic efficiency would significantly decrease as the suction pressure decreased. In addition, Jia et al. [79] conducted a study that was different from the above-mentioned scholars. They mainly investigated the influence mechanism of factors such as the fillet radius of the groove, the groove width, and the diaphragm thickness on the diaphragm diameter stress. The diaphragm radial stress was less affected by the fillet radius, while the diaphragm deflection and radial stress showed a significant downward trend with the increase in diaphragm thickness or the decrease in groove width.

In conclusion, diaphragm compressors have been widely applied in hydrogen refueling stations due to their oil-free and high-purity compression characteristics. At present, research on diaphragm hydrogen compressors mainly focuses on the optimization of hydraulic oil performance, innovative design of cavity profile, free-moving piston structure, thermal–structural coupling analysis, and improvement of cooling systems. However, it still faces some key issues. The high-pressure hydrogen environment is prone to hydrogen embrittlement and material fatigue problems, especially for austenitic stainless steel, whose fatigue limit drops significantly after pre-filling with hydrogen. The excessively high temperature in the exhaust hole area leads to thermal stress concentration, which seriously affects the sealing performance and service life. The volumetric efficiency is also significantly reduced by up to 37% due to the compressibility of the hydraulic oil and the influence of clearance gas [69]. In addition, during the industrialization process, it also faces problems such as high manufacturing costs due to special anti-hydrogen embrittlement materials and high-precision processing, as well as the complexity of operation and maintenance caused by professional maintenance requirements, which restrict its further promotion.

3.2. Liquid-Driven Piston Hydrogen Compressor

3.2.1. The Working Principle of the Hydraulic-Driven Piston-Type Hydrogen Compressor

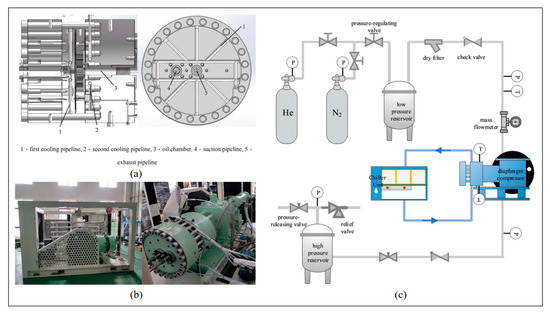

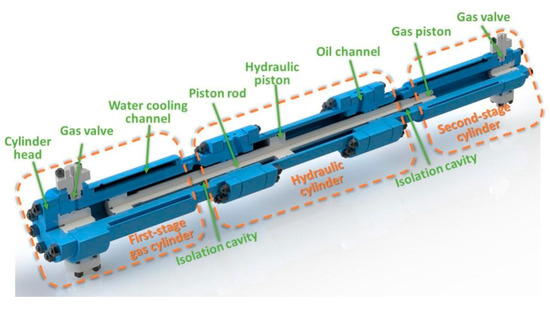

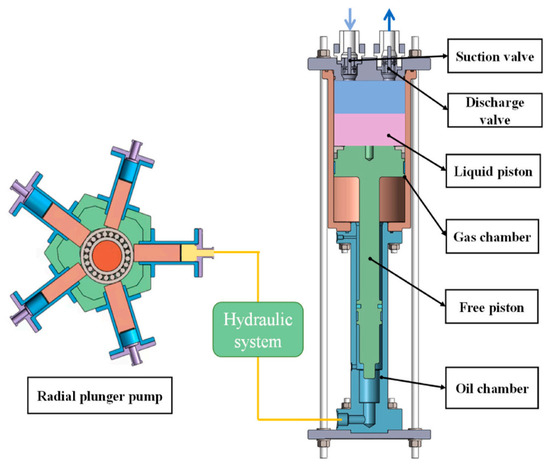

The liquid-driven piston hydrogen compressor is a type of compressor that uses hydraulic oil to drive the piston to reciprocate, thereby pressurizing and transporting hydrogen. It belongs to the category of positive displacement compressors. A typical physical structure of a two-stage liquid-driven piston hydrogen compressor is shown in Figure 12, which is a double-head structure, and it can mainly be divided into three parts. The first part is mainly composed of a first-stage cylinder, a first-stage gas piston, a piston rod, a gas valve, and a water-cooling channel. The second part mainly consists of an isolation chamber, a hydraulic piston, a piston rod, and a hydraulic oil channel. The third part is roughly the same in structure as the first part. Among them, the first-stage gas piston of the first part, the hydraulic piston of the second part, and the second-stage gas piston of the third part are, respectively, fixed on the far left, middle, and far right of the piston rod, and these three move along with the movement of the piston rod.

Figure 12.

Physical structure of two-stage hydraulic-driven piston compressor [80].

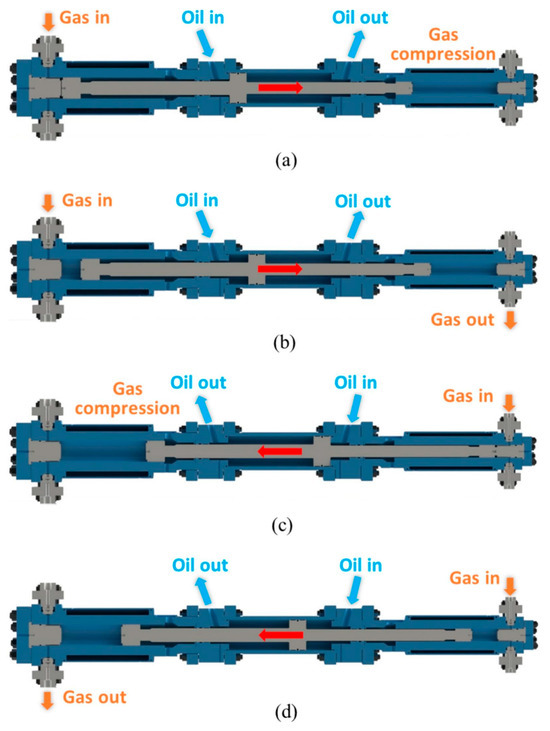

The piston of the two-stage liquid-driven piston hydrogen compressor can achieve two pressurizations of hydrogen in one reciprocating cycle, with high compression efficiency. The working principle is shown in Figure 13, and the working process is as follows. The hydraulic oil booster pressurizes the hydraulic oil and injects it into the isolation chamber through the hydraulic oil channel in the second part, pushing the hydraulic piston to move to the right. At the same time, the first-stage gas piston in the first part is also driven to start moving to the right, and the gas valve used for intake opens, allowing the hydrogen to be compressed and to be sucked into the first-stage cylinder. When the hydraulic piston moves to the right, dead center, the intake valve closes, and the hydraulic piston starts to reverse and move to the left. At this time, both the intake valve and the exhaust valve are in the closed state, and the first-stage cylinder is in a completely sealed state. Hydrogen begins to be compressed by the first-stage gas piston. Then, when the hydrogen in the first-stage cylinder reaches the first-stage compression pressure, the gas valve used for hydrogen exhaust opens, and the hydrogen is transferred from the first-stage cylinder to the second-stage cylinder through the connecting pipeline. At this point, the first-stage compression process of hydrogen is completed, and the second-stage compression process is about to begin. The second-stage compression process is similar to the first-stage compression process. Hydrogen is further pressurized in the second-stage cylinder to the second-stage compression pressure (which is also the final exhaust pressure) and then discharged from the second-stage cylinder. As this compressor is of a double-head structure, when the first-stage cylinder is undergoing expansion and intake processes, the second-stage cylinder is simultaneously performing compression and exhaust processes. Due to the existence of the intermediate isolation chamber and the connecting pipeline air valve, the operation of these two cylinders is independent and does not affect each other.

Figure 13.

Working principle of hydraulic-driven piston compressor: (a) The time when the first-stage piston is at the top dead center; (b) the suction process of the first stage; (c) the time when the second-stage piston is at the top, dead center; and (d) the suction process of the second stage [80].

3.2.2. Research Status and Existing Problems

As the oldest type of compressor, the piston compressor was invented by British engineer George Medhurst in 1799 as a single-stage steam-driven piston air compressor for mine ventilation, which was the first industrial compressor. Today, piston compressors still shine brightly in the industrial field due to their high-pressure capacity, technological maturity, and high adaptability. Among them, the crankshaft drive is the most classic power transmission form for piston compressors. Its main advantages are high mechanical efficiency and relatively low mass production cost. However, its disadvantages are also quite prominent: relatively large vibration and noise, insufficiently sensitive control, and difficulty in achieving pure oil-free compression. For the problems existing in crankshaft-driven piston compressors, using high-pressure liquid instead of crankshaft-driven pistons is a good choice. The feature of the liquid-driven piston compressor is that it can flexibly and precisely control the exhaust pressure and flow of the compressed gas by adjusting the flow and pressure of the hydraulic oil. Because the hydraulic oil chamber is completely isolated from the compression cylinder chamber, it is easier to achieve oil-free compression. Up to now, liquid-driven piston hydrogen compressors have accumulated a great deal of industrial experience, and the related technologies are relatively mature. Research on liquid-driven piston hydrogen compressors mostly focuses on the influence of piston rings and operating conditions on the compressors. Piston rings, as indispensable sealing components of compression cylinders, play a crucial role in sealing the cylinders, ensuring the normal progress of the compression process, and preventing air leakage. Yu et al. [81] established a mathematical model for simulating the unsteady flow within the piston ring clearance. Through this mathematical model. The pressure distribution of the piston rings was obtained, revealing the mechanism of non-uniform wear of the ring components. H.Winkelmann et al. [82] proposed an advanced design concept for the piston rings in the cylinder friction contact of piston compressors based on the hydrogen compression process, that is, to use PI and PPS plastics modified by dry-lubricated polytetrafluoroethylene and reinforced with carbon fibers to meet the requirements of high-stress friction inside the compressor. Constructing a mathematical model to study and predict the changes in hydrogen parameters inside the compressor is also a good choice. Ye et al. [83] developed a transient model using ANSYS Fluent with dynamic mesh technology and the NIST Real Gas Model to accurately simulate hydrogen flow and heat transfer. The model was validated against experimental data with a deviation of less than 6.29 K in exhaust temperature. Moreover, Ye et al. [84] also utilized a real hydrogen model and dynamic grid technology to construct a three-dimensional numerical model based on the reciprocating operation conditions of the compressor to reveal the influence of the opening and closing states of the gas valves used for hydrogen intake and exhaust on the pressure fluctuations and temperature inside the cylinder. Operating conditions are also important factors affecting the performance of compressors. Currently, relevant research focuses on aspects such as the reciprocating frequency of the piston, load conditions, and suction pressure. Zhao et al. [85] developed a novel capacity control system (CCS) for reciprocating compressors, which accurately compressed hydrogen based on actual demand. Carbon emissions and costs were reduced by 41.93% and 36.49%, respectively, significantly lowering the storage and transportation costs of hydrogen. Based on the two-end liquid-driven piston compressor, Qi et al. [86] adjusted the oil supply rate of each hydraulic cylinder to achieve a balanced pressure ratio between the two stages at different suction pressures. As a result, the power difference between the two stages was reduced from 35.8 kw to 11.9 kw, and the temperature deviation was decreased from 200.8 K to 5.6 K. Some scholars have proposed a non-destructive monitoring method for different operating pressure conditions, obtained the p-V curves of two-stage liquid-driven piston compressors, and analyzed the performance of compressors under different pressures [87].

The performance and durability of liquid-driven piston hydrogen compressors are significantly influenced by the materials used for key components, such as the piston, cylinder liner, and piston rings, as well as the thermal conditions during operation. Pistons are typically manufactured from high-strength aluminum alloys or forged steel, chosen for their favorable strength-to-weight ratio and fatigue resistance. Cylinder liners are commonly made from cast iron, ductile iron, or hardened steel, often featuring chrome plating on the inner surface to enhance wear resistance and reduce friction. For piston rings, gray cast iron or advanced polymer composites (e.g., PTFE-modified polyimide (PI) or polyphenylene sulfide (PPS) reinforced with carbon fibers) are widely employed to achieve a balance between sealing performance, low friction, and compatibility with high-pressure hydrogen environments [82].

In a typical compressor piston ring and cylinder liner pairing structure, as shown in Figure 14, the sealing function is accomplished jointly by the rider belt and the piston ring. The rider straps on both sides of the piston are mainly used to support and guide the movement of the piston. They do not play a sealing role because they have pressure relief grooves. Therefore, the piston ring is the core seal. The cutout of the piston ring and the microscopic gap formed during processing can lead to leakage. Its sealing is based on the principle of throttling, so a multi-ring combination is often adopted to ensure the sealing effect [88].

Figure 14.

Schematic of piston ring sealing system (a) and 3d structure of piston ring/rider band (b) [88].

During the operation of the liquid-driven piston compressor, the friction pair formed by the piston ring and the cylinder liner is the core and one of the most vulnerable parts. The frictional properties and material selection of this friction pair directly determine the sealing performance, wear rate, and service life. In a high-pressure hydrogen environment, this challenge is particularly severe.

Firstly, the low viscosity characteristic of hydrogen gas makes it difficult for it to form an effective fluid dynamic pressure lubrication film at the friction interface, causing the piston ring and cylinder liner to often be in boundary lubrication or even dry friction states, which aggravates the wear of the materials. As shown in Figure 14, uneven wear can lead to the failure of the piston ring’s sealing, an increase in hydrogen leakage rate, and a decrease in volumetric efficiency [88].

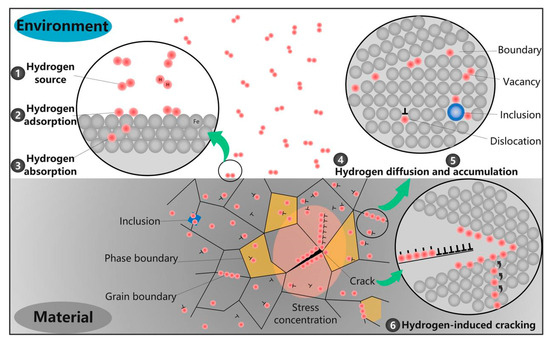

Secondly, hydrogen embrittlement is a common problem faced by compressor materials. For piston rings and cylinder liners, hydrogen atoms will penetrate the metal under high pressure and accumulate at defects such as dislocations and grain boundaries, resulting in decreased material plasticity and a lower threshold for crack initiation. Under the combined action of alternating mechanical stress (from the reciprocating motion of the piston) and thermal stress, it is highly likely to trigger the initiation and expansion of micro-cracks, ultimately leading to brittle fracture of the piston ring or peeling of the inner wall of the cylinder liner [89,90].

Therefore, in terms of the material selection for piston rings, researchers are working on developing high-performance polymer composite materials. For instance, Winkelmann et al. [82] proposed using polyimide (PI) modified by dry lubrication with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and polyphenylene sulfide (PPS) and reinforced with carbon fibers. These materials not only have self-lubricating properties to reduce the friction coefficient but also have non-metallic characteristics that make them insensitive to hydrogen embrittlement, while maintaining good mechanical strength and dimensional stability to adapt to the high-stress friction conditions inside the compressor. For metal components such as cylinder liners, high-nickel content austenitic stainless steel (such as AISI 316L, 304) or special alloys need to be selected. These materials have relatively lower hydrogen embrittlement sensitivity in high-pressure hydrogen environments [91,92].

The cylinders of hydrogen compressors are usually made of iron–carbon alloys such as cast iron, ductile iron, and forged steel. However, iron–carbon alloys will undergo hydrogen corrosion at 200–300 °C, as shown in Figure 15. The metal reacts with hydrogen to form methane. The methane molecules generated exist in the grain boundary gaps, causing cracks and reducing the plasticity of the cylinder, leading to hydrogen corrosion. Therefore, the hydrogen embrittlement phenomenon that occurs in the cylinder during the hydrogen compression process is a common problem in hydrogen compressors, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Schematic diagram of hydrogen permeation and hydrogen embrittlement [89].

Figure 16.

(a) The influence of test temperature on the relative area reduction rate of 316 type and 304 series stainless steel in a 1.1 MPa hydrogen and helium environment (304 (S) and 316 (S) sensitized 304/316 stainless steel) [90]; (b) determined maximum thermal expansion coefficients (theatrical expansion coefficient: THE) of AISI 304, (c) AISI 316, (d) iron-nickel-based superalloys, and (e) ferritic steels; the max value (for relevant material data and test information, please refer to references [92,93]).

In summary, current research on liquid-driven piston hydrogen compressors mainly focuses on the optimization of piston ring materials and structures, flow field and heat transfer simulation based on real hydrogen models and dynamic grids, and the development of capacity control systems, as well as the regulation and balancing strategies under multi-parameter operating conditions. However, it still faces key issues such as wear and leakage of the piston ring sealing assembly, hydrogen embrittlement of the cylinder material, complex vibration and temperature control during operation, and the difficulty in balancing efficiency and stability under high-load conditions. At the same time, the hydraulic and pneumatic systems need to be highly coordinated, and the control complexity is high. During the industrialization process, the energy efficiency of the system decreased significantly under variable working conditions [86], and there was a lack of unified performance testing and evaluation standards, which further restricted the large-scale application and interchangeability of the equipment.

3.3. Ionic Liquid Hydrogen Compressor

3.3.1. The Working Principle of Ionic Liquid Hydrogen Compressor

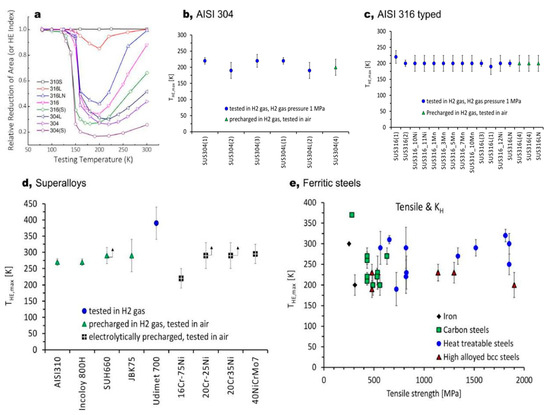

The traditional piston compressor, due to its numerous internal mechanical components, has problems such as high mechanical wear and large heat loss at low power. Ion liquid compressors have solved the problems of sealing and lubrication under high pressure in traditional piston compressors, and they have good adaptability to a wide range of operating conditions and an efficient compression process. It is also suitable for design as a large-displacement model. Its core technical feature lies in the use of an ionic liquid with special physical and chemical properties to be filled into the cylinder, and the gas is compressed under the drive of a hydraulic piston. The ionic liquid is driven into the cylinder by a high-pressure liquid pump and recycled. Ionic liquids are almost incompressible, do not dissolve or contaminate hydrogen, and also have good lubricating and cooling properties, which solves the drawbacks existing in several other types of compressors.

Figure 17 shows the structural schematic diagram of the ionic liquid compressor. Its structure consists of an oil suction valve, an oil discharge valve, a liquid piston, a gas chamber, a free piston, an oil chamber, and a hydraulic system—a radial plunger pump. The main working principle is that the radial plunger pump drives the oil through the hydraulic system, pushing the piston to reciprocate and thereby changing the volume of the gas chamber to increase gas pressure.

Figure 17.

Schematic diagram of the structure of the ionic liquid compressor [93].

3.3.2. Current Development Status and Existing Problems

As a core piece of equipment in the hydrogen energy industry chain, ion liquid compressors have made remarkable progress in recent years, especially in the field of high-pressure and large-displacement hydrogen compression. Represented by the world’s first ion liquid seal compressor of Dongde Industrial, it has achieved a technological leap of over 100 MPa in ultra-high pressure and 50,000 standard cubic meters in large displacement. Moreover, it has achieved zero hydrogen leakage by relying on the circulating ion liquid seal technology. Energy consumption is reduced by 20–30%. Currently, ionic liquid compressors are mainly applied in hydrogen refueling stations, hydrogen production plants, hydrogen storage and transportation, and other scenarios. Due to their zero-leakage feature, they have been extended to special gas treatment fields such as petrochemicals. The future development trend focuses on higher pressure scale, intelligent Internet of Things control, and multi-field applications, but it also faces challenges such as long-term reliability verification, cost optimization, and standard improvement. The current research status of ion compressors is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Research status of ion compressors.

In conclusion, ionic liquid compressors, as an emerging oil-free compression technology, have attracted attention due to their high sealing performance and thermal management advantages. The research focuses on two-phase flow simulation, valve optimization, and system integration. However, during the long-term use of ionic liquids, their corrosive effect on metal structural materials is a challenge that cannot be ignored. The chemical properties of different ionic liquids vary greatly, and their corrosive effects on materials also differ significantly. For instance, it has been shown [102] that ionic liquids containing [NTf2]− anions have a relatively weak corrosive effect on AISI 347 stainless steel, demonstrating good compatibility, while the same ionic liquids may exhibit a stronger corrosive tendency towards nickel-based superalloys such as Hastelloy C-276. This corrosion not only damages the structural integrity of core components such as compressor cylinders and valves, but also the corrosion products may contaminate the ionic liquids and the compressed hydrogen gas, which is fatal for fuel cell applications with extremely high purity requirements. Therefore, developing low-cost structural materials and surface protective coatings with optimal compatibility with specific ionic liquids is a problem that ionic liquid compressors must solve for large-scale industrialization. Moreover, the movement of the piston can cause the liquid surface to break, generating droplets and bubbles, which affects its sealing and heat transfer [97]. There are still design and manufacturing issues. The automatic valves in ionic liquid compressors are highly sensitive to the two-phase gas–liquid flow. Unstable valve movement may cause liquid entrainment or gas backflow, thereby reducing performance. We propose to integrate a valve–piston coupling sub-model within the simulation framework to optimize the following aspects: valve spring characteristics, the number and geometry of the flow channels, and the timing of valve movement relative to piston movement. This approach will help minimize flow losses and improve heat transfer efficiency, thereby achieving nearly isothermal compression. Moreover, there is a lack of standards for the initial liquid-level setting, which relies on design experience [95]. The system integration is difficult. The coupling control between the hydraulic drive and the compression chamber is not yet mature, and the fault diagnosis and maintenance system is not perfect.

4. Challenges and Solutions Faced by Various Mechanical Hydrogen Compressors

4.1. Diaphragm Hydrogen Compressor

In the actual operation of diaphragm hydrogen compressors, multiple technical challenges are faced, which seriously affect their working efficiency and reliability, especially under high-pressure and even ultra-high-pressure conditions (≥90 MPa) where the problems are more prominent. Firstly, the actual suction volume is significantly lower than the theoretical design value, mainly due to the compressibility of the hydraulic oil, the expansion of the residual gas in the clearance, and the incompleteness of the diaphragm deformation process. These factors collectively lead to a significant reduction in volumetric efficiency, especially under ultra-high-pressure conditions above 90 MPa, where volumetric loss is even more severe, greatly restricting the improvement of the overall machine performance. Secondly, during the operation of compressors, the problem of excessively high exhaust temperature is common, often exceeding 200 °C. The continuous high-temperature environment not only causes thermal stress concentration in key components, but also significantly accelerates the fatigue aging of the diaphragm, and even induces hydrogen embrittlement. Hydrogen embrittlement will further reduce the mechanical properties and fracture toughness of materials, seriously threatening the long-term safe operation of equipment. As a core moving component, the short lifespan of the diaphragm is also a key factor restricting the promotion and application of this type of compressor. Due to the fact that the diaphragm needs to undergo repeated flexural movements at high frequencies and constantly come into contact and rub against the compression chamber, microscopic cracks are prone to occur and gradually expand, eventually leading to diaphragm perforation or complete failure. This failure mode not only leads to an increase in the frequency of compressor shutdowns for maintenance, but also significantly raises the maintenance cost throughout its entire life cycle. Finally, the working performance of the hydraulic oil has a significant impact on the overall behavior of the compressor. The temperature, viscosity changes, and compressibility of the oil are all directly related to the energy transfer efficiency and sealing effect. Especially in low-temperature environments, the viscosity of the hydraulic oil rises sharply, resulting in increased flow resistance and a decrease in effective power, which further reduces the overall efficiency and response capability of the compressor. Therefore, the optimization of hydraulic oil characteristics and the adaptation to working conditions have become significant challenges in system design.

To address these issues, there are numerous solutions. Firstly, the structure can be optimized, for instance, by adopting a freely moving oil piston design [74], achieving a “zero-pressure” suction stage and significantly enhancing volumetric efficiency. For example, for the 90 MPa model, it can be increased from 37% to 66%. By adopting a new cavity profile design [71,73], the diaphragm stress concentration is reduced and the maximum radial stress is decreased by 8.2% to 19.6%.Alternatively, a circumferential cooling structure [76] can be adopted to effectively reduce the exhaust temperature, with a maximum cooling of up to 189.5 °C. Secondly, a hydraulic oil temperature control system can be used. By controlling the oil temperature (for example, from 95 °C to 35 °C), the volumetric efficiency can be enhanced [68], and at the same time, the thermal stress can be reduced. Intelligent monitoring and diagnosis can also be used, based on dynamic oil pressure signals [70] or acoustic emission technology [72], to achieve real-time monitoring of diaphragm status and early fault warning.

4.2. Liquid-Driven Piston Hydrogen Compressor

In the actual operation of the liquid-driven piston hydrogen compressor, there are multiple technical challenges. Firstly, the problems of friction, wear, and sealing are the most prominent. Due to the compressor’s long-term operation in a high-pressure hydrogen environment, the non-uniform wear between the piston ring and the cylinder wall occurs due to poor lubrication, which seriously affects the sealing effect and leads to an increasing leakage rate. At the same time, the high-pressure hydrogen environment will induce the hydrogen embrittlement phenomenon of the materials, causing micro-cracks or even fractures in the piston ring under alternating stress, further reducing its service life and sealing reliability. Secondly, there is the issue of excessive vibration and noise. Due to the inherent unbalanced inertial force of the traditional crank connecting rod mechanism, significant vibration can be caused, which not only reduces the smoothness of equipment operation but also affects the structural safety of the compressor unit foundation and connected pipelines. Intense vibration and high-frequency noise also have adverse effects on the internal environment of hydrogen refueling stations and the comfort and safety of equipment maintenance personnel. The last issue is the instability of thermodynamic performance. Due to the fluctuation of suction pressure and the unreasonable distribution of compression ratios between each stage, it is easy to cause an imbalance in the matching between stages and an uneven distribution of exhaust temperature, which in turn affects the power consumption and efficiency stability of the entire machine. Especially under variable working conditions, this problem is more prominent, seriously restricting the working range and adaptability of the compressor.

There are also many solutions. Firstly, the surface materials of the friction pairs can be optimized. For instance, high-performance polymer composite materials [82] can be used to manufacture piston rings, or the surface of the metal cylinder liners can be modified (such as nitriding, chrome plating, or using diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings) to simultaneously enhance their wear resistance, reduce the friction coefficient, and improve their resistance to hydrogen embrittlement. Secondly, the control system was optimized by introducing a variable speed control strategy [86] to adjust the fuel supply rate of each section, achieving a balanced pressure ratio, reducing power deviation by 66.7% and temperature deviation by 97.2%. The capacity control system (CCS) [85] was developed to achieve precise load control from 0% to 100%, reducing unit energy consumption and vibration and shock by 77.6%. Non-destructive monitoring technology is used to assist in detection, such as the dynamic pressure monitoring system based on strain sensors [80], with a deviation of less than 2.01%, achieving non-invasive condition assessment.

4.3. Ionic Liquid Hydrogen Compressor

As an emerging compression technology, ionic liquid hydrogen compressors have shown potential in terms of high efficiency and energy conservation as well as hydrogen purification. However, their further development still faces several key challenges. Firstly, the two-phase flow pattern in the compression chamber is extremely complex. Unstable gas–liquid interfaces, droplet entrainment, and dynamic changes in flow patterns occur frequently, which not only affect the stability of the compression process but also reduce the volumetric efficiency and the final purity of the compressed hydrogen. Secondly, there are significant challenges in the thermal management of the system. The heat transfer efficiency between ionic liquids and hydrogen is relatively low, which causes the compression process to approach an adiabatic state. A large amount of mechanical energy is converted into thermal energy and is difficult to effectively dissipate, resulting in energy loss and possibly causing local overheating. In addition, the dynamic response performance of the self-acting valve in a gas–liquid two-phase environment is poor. There is a lag in the action of the valve plate, which can easily lead to gas backflow or liquid hammer phenomena, seriously affecting the reliability and service life of the compressor. Finally, material compatibility and corrosion protection are also major challenges. Ionic liquids, especially under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions, may cause corrosion to metal structural components. It is necessary to comprehensively consider multiple aspects, such as material selection and surface treatment, to ensure the long-term safety and stability of the system operation. The systematic solution to these problems is the key to promoting the large-scale industrial application of this technology.

Firstly, porous media can be adopted to enhance heat transfer [103], combined with the SOBP-SO algorithm to optimize parameters, achieving energy savings of 26.8%. This time, the number of flow channels of the self-acting valve can be optimized (four or six channels are optimal) to reduce the liquid entraining rate (<9%) and enhance the heat transfer performance [104], or the piston movement trajectory can be controlled (such as the T8 trajectory) to improve the liquid-level stability and exhaust quality [105]. In the F-C operating mode, the piston hardly ever collides or remains at the top or bottom dead center [106].The service life of components can be prolonged by developing corrosion-resistant coatings or composite materials. AISI 316L or 347 stainless steel is selected, which exhibits excellent corrosion resistance in most ionic liquids [102].

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Comprehensive Performance and Discussion of Future Technology Paths

This article systematically reviews the research progress and technical challenges of three types of mechanical hydrogen compressors. From the perspective of performance comparison, diaphragm compressors have significant advantages in purity and sealing, but their volumetric efficiency is greatly affected by the characteristics of hydraulic oil; liquid-driven piston compressors perform exceptionally well in high-pressure adaptability, but they have prominent vibration and wear issues; ionic liquid compressors have great potential in thermal management and energy efficiency, but the control of gas–liquid two-phase flow remains a challenge. In the future, with the deep integration of materials science, intelligent control, and multi-physics field simulation technologies, mechanical hydrogen compressors will develop towards the direction of high efficiency, intelligence, and high reliability. Especially in high pressure (≥90 MPa), high frequency, and variable condition scenarios, interdisciplinary research is urgently needed to achieve the leap from “laboratory performance” to “industrial reliability.

5. Conclusions and Future Solutions

5.1. Conclusions

This paper systematically reviews the key role of mechanical hydrogen compressors in hydrogen refueling stations, with a focus on analyzing the working principles, structural features, performance bottlenecks, and research progress in recent years of diaphragm, liquid-driven piston, and ion liquid compressors. Through the review and summary of a large number of documents, the following main conclusions are drawn:

(1) Diaphragm compressors have become one of the mainstream technologies for compressing high-pressure hydrogen in hydrogen refueling stations due to their leak-free and high-purity output characteristics. Research shows that their performance significantly depends on the characteristics of the hydraulic oil, the design of the cavity structure, and the thermal management strategy. Appropriately lowering the oil temperature can help improve volumetric efficiency and control exhaust temperature, but if the temperature is too low, it will cause the oil to become viscous, which will affect efficiency. By improving the piston design, optimizing the cavity profile, and conducting thermal–structural coupling analysis, the equipment efficiency and diaphragm life can be effectively enhanced. In addition, factors such as suction temperature, pressure ratio, and rotational speed have a significant impact on overall performance, and multi-variable collaborative optimization needs to be carried out.

(2) Liquid-driven piston compressors have the advantages of high-pressure output, flexible control, and high volumetric efficiency, and have broad application prospects. The core issue lies in the sealing performance of the piston rings and the material’s resistance to hydrogen embrittlement. The use of polymer composite materials such as PTFE-modified PI/PPS can effectively reduce the impact of wear and hydrogen embrittlement. The introduction of variable speed control and multi-stage pressure regulation strategies helps to reduce energy consumption and temperature fluctuations and enhance operational stability. Meanwhile, technologies such as strain gauge monitoring and p-V curve analysis provide strong support for real-time status diagnosis and early fault warning.

(3) As an emerging technology, ionic liquid compressors have attracted extensive attention due to their high efficiency, low vibration, and oil-free output characteristics. The gas–liquid two-phase flow behavior, valve control, and the utilization of porous media to enhance heat transfer are crucial for achieving near-isothermal compression. Parameters such as the piston movement law, spring characteristics, and the number of flow channels also significantly affect performance, and multi-objective optimization is required to achieve the best operating conditions. The application of hydraulic–pneumatic coupling simulation and intelligent control algorithms has further enhanced the dynamic response and energy efficiency of the system.

In summary, based on the current technology readiness level (TRL), operational experience, and market penetration, the diaphragm compressor holds the greatest near-term industrial potential for widespread deployment in hydrogen refueling stations. Its oil-free, high-purity output, combined with well-established manufacturing processes and a proven track record in handling high-pressure (e.g., 90 MPa) hydrogen, makes it the most reliable and readily scalable solution for the coming 5–10 years. Meanwhile, the liquid-driven piston compressor remains a strong contender for applications requiring very high flow rates and flexible control, particularly in large-scale hydrogen production and storage hubs, provided that challenges related to piston ring wear and hydrogen embrittlement are further mitigated.

Looking forward, research efforts should focus on a dual track. In the short term, the priority is to enhance the reliability and reduce the lifetime cost of incumbent technologies (diaphragm and liquid-driven piston). This includes developing advanced anti-hydrogen embrittlement materials and coatings, implementing intelligent health monitoring and predictive maintenance systems, and optimizing thermal management for higher energy efficiency. In the mid-to-long term, the research focus should shift towards breakthrough innovations for next-generation compressors, with the ionic liquid compressor being a primary candidate. Key research thrusts here must include mastering the gas–liquid two-phase flow to achieve near-isothermal compression, designing highly responsive and durable self-acting valves, and discovering or synthesizing novel ionic liquids with ideal thermophysical properties and minimal corrosivity. Ultimately, the convergence of digitalization (e.g., digital twins and AI-driven control) and material science will be pivotal in advancing all compressor types towards higher efficiency, greater intelligence, and enhanced sustainability.

5.2. Future Research and Development Directions

Although mechanical hydrogen compressors have made significant progress in technology and application, several challenges still need to be addressed for their wide application in the next generation of hydrogen refueling stations. Future research and development should revolve around the following strategic directions, classified by compressor type:

(1) Diaphragm compressor

Innovate materials and develop new hydrogen embrittlement (HE) resistant materials and advanced coatings (such as ceramic or amorphous metal coatings) for the surfaces of diaphragms and cavities to extend service life under ultra-high-pressure (≥90 megapascals) conditions. Use integrated real-time temperature monitoring and adaptive cooling systems (such as annular cooling channels or microchannel heat exchangers) to reduce thermal stress and improve volumetric efficiency. Digital twin technology is adopted to establish a multi-physics coupling model (fluid–structure–thermal) to simulate diaphragm fatigue, predict faults, and achieve predictive maintenance.

(2) Liquid-driven piston compressor

A multi-stage sealing system is designed with self-lubricating polymer composite materials and surface textures to reduce wear and hydrogen leakage. Systematically study the hydrogen embrittlement mechanism in Fe-C alloys and develop anti-hydrogen embrittlement materials. Or introduce an active vibration-damping system and optimize the kinematics of the piston to enhance operational stability and comfort. Implement artificial intelligence (AI) and digital twin platforms to optimize multi-level pressure ratios, capacity control, and energy efficiency in real-time under variable load conditions.

(3) Ionic liquid compressor

Design new ionic liquids and develop customized ionic liquids with high thermal stability, low corrosiveness, and optimal viscosity to enhance heat transfer and sealing performance. Optimize the piston trajectory and valve design to stabilize the gas–liquid interface and reduce droplet entrainment. Enhance heat transfer by integrating porous media or microstructures in the compression chamber to promote near-isothermal compression and improve energy efficiency. Establish standardized protocols for initial liquid-level setting, valve performance testing, and system reliability assessment to promote large-scale industrial applications.

(4) Suggestions at the cross-domain and system levels:

The industry also needs to jointly promote the standardization and certification system construction of high-pressure hydrogen compressors and facilitate the coupling of hydrogen compressors with renewable energy sources (such as solar and wind energy) and smart grids to achieve green and low-carbon hydrogen compression. Intelligent health management: By leveraging Internet of Things (iot)-based monitoring technology and big data analysis, real-time fault diagnosis, performance prediction, and life cycle management of compressor systems are achieved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-Q.L., J.-T.K. and J.-C.L.; methodology, J.-Q.L., J.-T.K. and J.-C.L.; validation, H.X., Y.F., M.-Y.Z., R.W. and Y.-M.D.; formal analysis, H.X., Y.F., M.-Y.Z., X.W. and Y.-M.D.; investigation, H.X., Y.F., M.-Y.Z. and Y.-M.D.; resources, H.X., Y.F., M.-Y.Z. and Y.-M.D.; data curation, H.X., Y.F., M.-Y.Z., X.W. and Y.-M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.X., Y.F., M.-Y.Z., R.W. and Y.-M.D.; writing—review and editing, J.-Q.L., J.-T.K. and J.-C.L.; visualization, H.X., R.W., X.W. and Y.-M.D.; supervision, H.X., Y.F., M.-Y.Z. and Y.-M.D.; project administration, J.-Q.L., J.-T.K. and J.-C.L.; funding acquisition, J.-Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by Ludong University (20220035).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This research is also the result of receiving the support for the provincial college student’s innovation and entrepreneurship training program project in 2025 (Project: Research on the Creation and Safety Collaborative Optimization of Core Components for Hydrogen Circulation Systems in Fuel Cells), and Ludong University college students innovation and entrepreneurship training program, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zheng, X.; Shao, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Shi, J.; Gu, C. The impacts of the hydrogen economy on climate: Current research and future projections to 2050. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 119, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Oil 2025; Licence: CC BY 4.0; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/oil-2025 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Johnson, N.; Liebreich, M.; Kammen, D.M.; Ekins, P.; McKenna, R.; Staffell, L. Realistic roles for hydrogen in the future energy transition. Nat. Rev. Clean Technol. 2025, 1, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]