1. Introduction

The extensive use of induction motors (IMs) in the industrial environment due to their robustness, flexibility of application for a vast number of tasks and mechanisms makes them a priority for maintenance and condition monitoring, as the presence of faults could lead to performance reduction, increments in production costs, and catastrophic failure of the machines in the worst-case scenario [

1,

2]. Condition monitoring and fault detection are important tasks in the industry due to their connection to predictive maintenance, minimizing production downtime, improving maintenance and production efficiency, protecting the equipment and increasing safety in the workplace. For many years, these areas have been of great interest for researchers and industry, developing a plethora of techniques and methodologies to detect and identify the apparition of irregularities in the physical magnitudes available for the monitoring of the IMs (e.g., stator current, vibration signals, temperature, acoustic emissions, voltages, electrical power and, in more recent times, magnetic flux) and relate these variations to the emergence of mechanical or electrical faults by means of temporal, spectral or statistical analysis, as well as automated processing techniques like Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), one of the most popular DL tools, allow for the automatic extraction of features from the 1-D or 2-D inputs and achieve great classification results without the need for expert knowledge, and when paired with Time–Frequency Distribution (TFD) images, have become a growing trend for fault diagnosis.

One of the components of an IM that attracts more attention is the bearings, as they represent up to 40% of the reported faults [

1], with vibration signals as the preferred source of information for diagnosis. Many approaches have been presented, like the one in [

6], where the authors analyzed the HUST dataset applying Multitask Learning (MTL) to diagnose six faulty conditions with only one severity on different types of bearings, using the Continuous Wavelet Coefficient Maps (CWCMs) as inputs to a Long Short-Time Memory (LSTM) + CNN model. In [

7], a comparison between different TFDs on the Case Reserve Western University (CRWU) bearing dataset and experimental results showed that the use of the Fourier Synchrosqueezed Transform (FSST) on vibration signals achieved great performance when feeding 3-channel images of 28 × 28 pixels to a CNN, outperforming other popular TFDs, such as the Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) or the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). However, in [

8], a similar approach is presented for bearing fault diagnosis, using Transfer Learning (TL) and RGB images of 224 × 224 pixels, with the authors concluding that the CWT and FSST performed better than other TFDs. The superiority of the FSST for bearing diagnosis is confirmed in [

9], where the authors compared its performance against the Wavelet Synchrosqueezed Transform (WSST) on the CRWU dataset, and in [

10], where current signals went through the FSST and Hilbert Envelope Spectrum for diagnosing an outer race (OR) defect on bearings, identifying the related frequency component with ease. With a different approach, the authors of [

11] rearranged 1-D signals from different sensors and different natures to 2-D matrices, then assembled them to generate 120 × 120 inputs for a CNN model, obtaining good classification results for five faulty bearing conditions, highlighting that the reduction in the model parameters leads to a reduction in classification accuracy. In a similar manner, the work reported in [

12] presents a comparison of sound and vibration signals from the CWRU and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) datasets, analyzed by the Wavelet Scattering Transform (WST) and the Adaptive Superlet Transform (ASLT) to generate RGB and grayscale images of five sizes ranging from 16 × 16 to 224 × 224 pixels and classified by a hybrid CNN–Support Vector Machine (SVM) model, achieving better performance with the biggest images in grayscale for the diagnosis of three bearing conditions. The authors of [

13] developed a system based on the Internet of Things (IoT) technology for bearing fault detection using the STFT to process vibration signals, diagnosing the conditions by means of a CNN model with three convolutional and pooling layers with different kernel sizes, achieving a methodology that could be implemented online and offline. In [

14], the authors created a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to tackle bearing fault detection and Remaining Useful Life (RUL) estimation using vibration signals from a motor under different operating conditions, obtaining good results in both tasks with a novel DL method. A different approach is found in [

15], where the authors filtered the fundamental component from current signals to identify the harmonics related to different bearing conditions using both the CWT and STFT and compared the diagnostic performance of five CNN models extensively used in the literature, finding an improvement over non-filtered signals.

Other conditions studied with this kind of approach include broken rotor bars (BRBs), as reported in [

16], where the authors analyzed current signals using the STFT on the transient state, achieving good results for the diagnosis of four conditions with 25 × 25 grayscale images and a compact CNN model. Similarly, the author of [

17] developed a method to diagnose five BRB conditions from STFT images from vibration signals, using TL with four well-known CNN models and showing an improvement in detection accuracy over a CNN model that was not previously trained. Faults related to the kinematic chain connected to the IM have also been diagnosed, as reported by the authors of [

18], where gearbox wear was identified by the analysis of stray flux signals using a variant of the Multiple Signal Classification (MUSIC) algorithm, the Short-Time MUSIC (ST-MUSIC). Also, other investigated faults, such as eccentricities and misalignment, were studied by the authors of [

19] using the Persistence Spectrum to stray flux signals, generating 224 × 224 RGB images that fed a CNN model, allowing the detection of 5 different conditions related to these faults.

Similarly, TFDs and CNNs have been used to identify faults of different origins in IMs. One example of this is the research presented in [

20], where the authors applied the CWT on vibration and current signals to diagnose six different conditions in an IM: healthy, shorted turns, unbalanced, bearing’s inner race (IR), BRB and bent rotor; the results suggested that the use of 128 × 128 grayscale images, the fusion of the signals and features improved the diagnosis. The authors of [

21] presented a comparison of four TFDs for the diagnosis of a BRB, imbalance, and bearing defects using vibration signals, offering an analysis of the way these TFDs display the information and concluding that the ST-MUSIC gives more detailed information about the components related to the faults under study. In [

22], the authors used current signals from multiple sensors to diagnose BRB and bearing faults in a motor, transforming the 1-D signals to 224 × 224 RGB images fed to a TL-deep CNN (dCNN) model, obtaining a good performance using a larger CNN model when compared to other popular tools.

It has been seen that the use of TFD as inputs for CNN has become a trend for fault diagnosis; however, most of the time, the images are used directly as obtained, in RGB or grayscale, without a processing step that could improve the identification of the conditions under study, as in other fields. One technique that has shown improvements in the medical diagnosis area is the use of the 2-D Discrete Orthonormal Stockwell Transform (2D-DOST); this transform provides local spatial frequency information from images that can be used to characterize the horizontal and vertical frequency patterns and obtain sets of texture features [

23]. This technique has been used to diagnose multiple medical conditions, as in [

24], where the authors applied it to Magnetic Resonance Images (MRIs) to diagnose eight conditions using CNNs, outperforming other established methodologies in the area. The authors of [

25] used the DOST to analyze multiple sclerosis MRIs and compare the results to the Polar Stockwell Transform (PST), finding a slight advantage when using the PST; on the other hand, in [

26], the authors proposed a fusion methodology considering the 2D-DOST, the Orthogonal Ripplet II Transform (ORTII) and the original MRIs for the classification of Alzheimer’s disease using a CNN model, concluding the improvement of the results with the fusion of the extracted features. The 2D-DOST has been used in cancer prognosis [

27], glioblastoma prediction [

28], and seizure identification from MRIs during pregnancy [

29].

Considering the aforementioned, it is evident that the use of CNNs and TFDs for the diagnosis of a variety of fault conditions in IMs is a growing trend; however, most works focus on a particular component or type of faults, relying primarily on well-known databases with no empirical experimentation, employing vibration and current signals, whose sensors can be invasive, as preferred information sources; and using TFD images of considerable size with no extra processing and large CNN models for classification. In a recent work [

30], the authors explored the use of the 2D-DOST on STFT and CWT images from stray flux signals for the diagnosis of bearing faults in an IM with a lightweight CNN model, identifying an improvement in accuracy when applying the 2D-DOST to the grayscale CWT images, while the opposite was observed on the STFT dataset. In this paper, a continuation of the previous work is carried out, proposing a methodology where stray flux signals are analyzed using the STFT, CWT, FSST and ST-MUSIC to generate TFDs, which are then saved in RGB, grayscale and a third set processed with the 2D-DOST for the diagnosis of one healthy and eleven faulty conditions including bearing faults, various severities of BRBs, unbalances, misalignments and a loosened bolt. The results compare the performance on several configurations of TFDs and image types, including training times, accuracy, and the effect of processing tools on the inputs of a lightweight CNN model. With these results, the proposed method presents an alternative to improve the classification accuracy of a small CNN model for multiple fault diagnosis considering the use of various TFDs by employing a texture analysis tool as a preprocessing step in the analysis of stray flux signals using non-invasive sensors.

4. Discussion

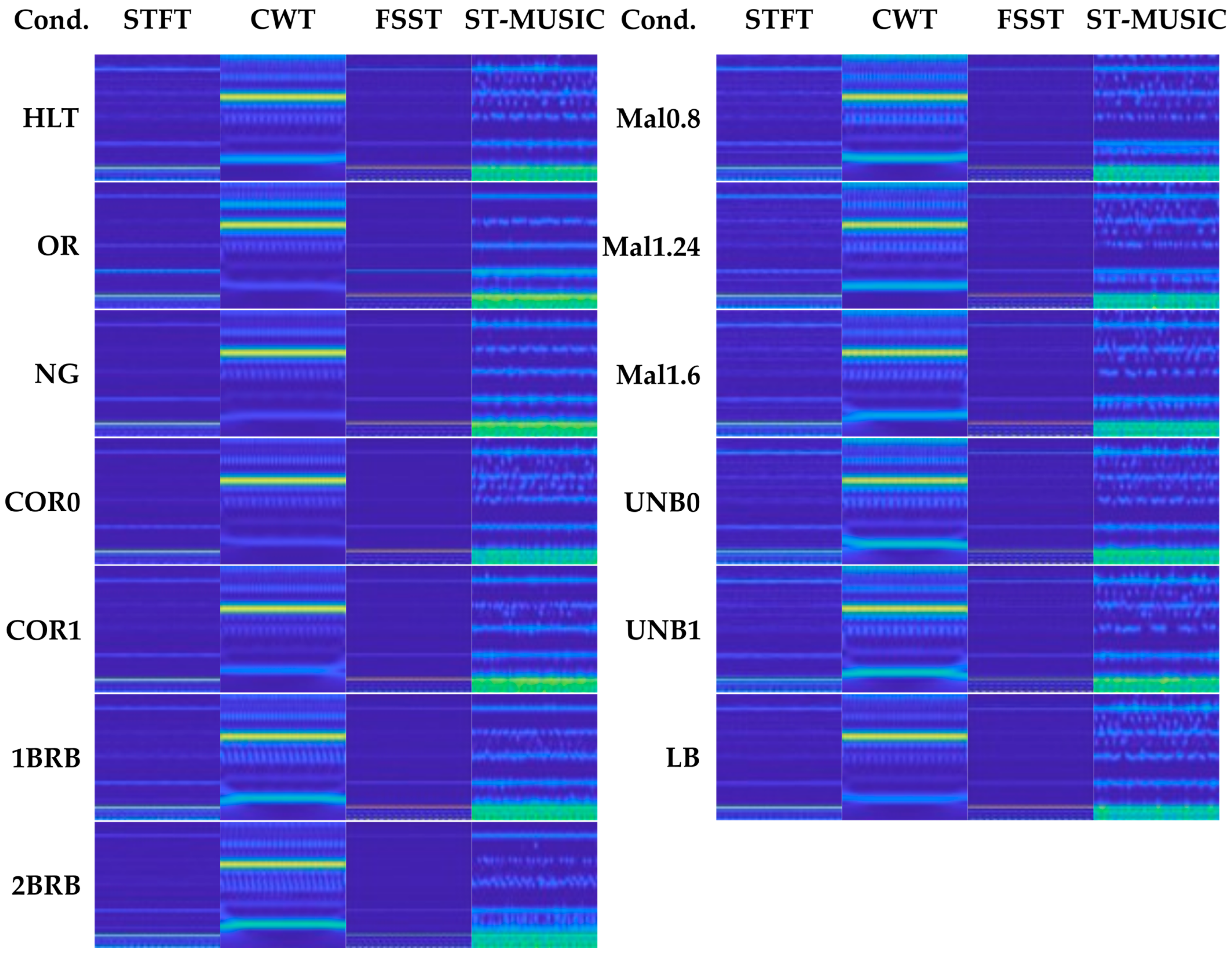

The graphs displayed in

Figure 3 illustrate the differences between the TFDs chosen for this paper, as the content in each one represents the same information in a different way, like having a logarithmic distribution in the case of the CWT, more definition in the frequency components with the FSST in comparison to the STFT, or a richer distribution in the ST-MUSIC. The comparison in

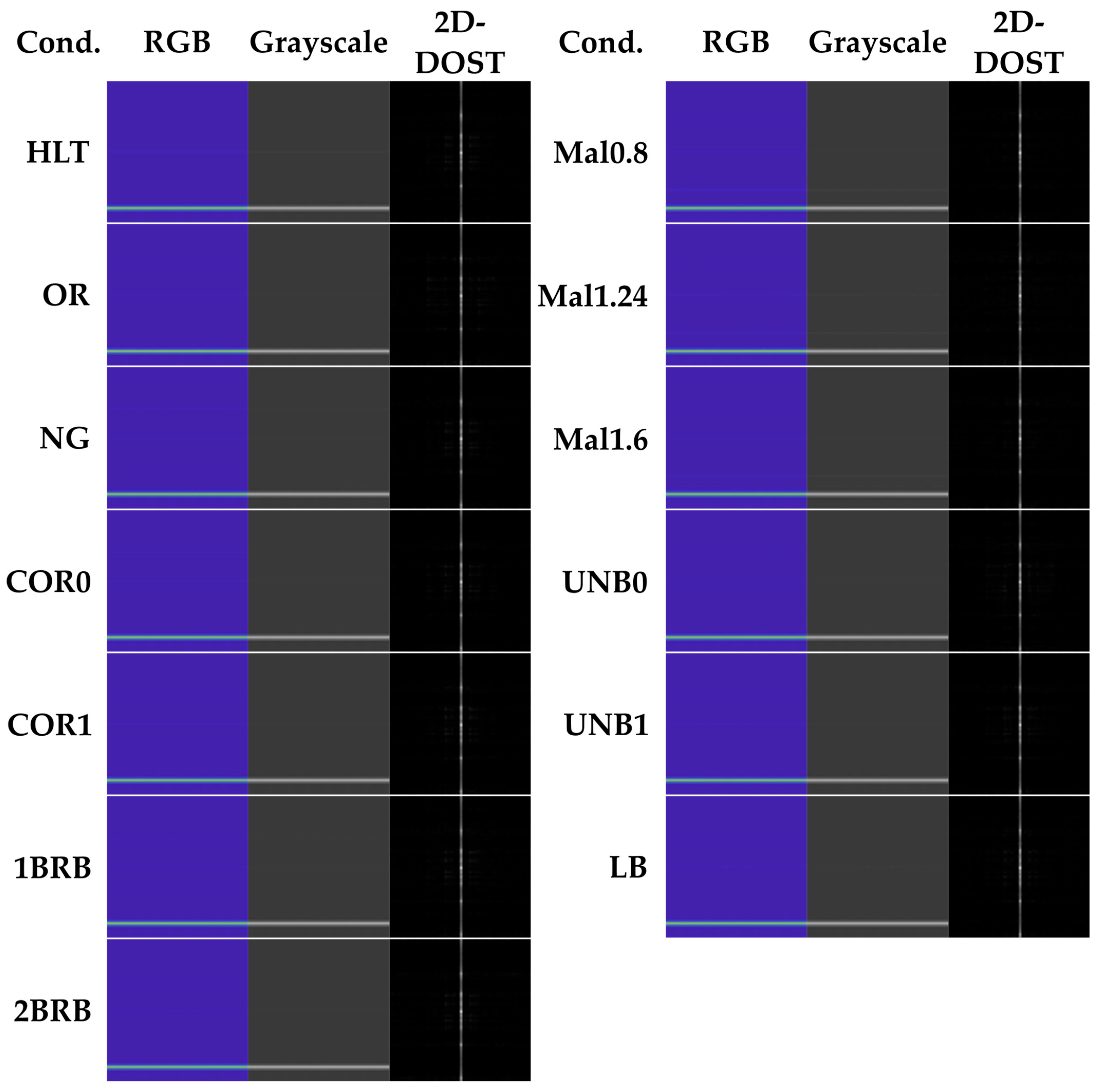

Figure 4 showed that the faults presented not enough information in the spectrograms to distinguish all conditions easily from one another in each dataset; the same could be said about the grayscale images in

Figure 5, which presented less detail due to the color palette, making it more difficult to discriminate the conditions by eye. Similarly, the comparison in

Figure 6 presented the same tendency, as most conditions share similar patterns with variations that are hard to identify.

The automatic feature extraction performed by the CNN was able to tackle this problem, achieving good results in most cases. As seen in

Table 3,

Table 5,

Table 7 and

Table 9, RGB images reached high results in condition classification in most cases while the use of grayscale pictures represented a reduction in the performance of the model, possibly related to the lower detailed and information, as those images have information of the three color layers (RGB) condensed in one; contrarily, the results when using the 2D-DOST processed datasets showed an improvement over the RGB sets, this could be caused by the distribution of the information performed by the DOST, which could facilitate the extraction of features performed by the CNN model.

Regarding the TFDs used, STFT, CWT and FSST have been used to detect faults in IMs, mostly in bearings, and have proved to be effective when discriminating against a couple of conditions affecting different components of the motor. On the other hand, the MUSIC algorithm is considered more resource-consuming, and the short-time variation is less common for fault detection; however, it showed a better performance on average and a similar average training time reduction as the other TFDs. All transforms showed adequate results for identifying the twelve conditions and presented similar difficulties when diagnosing the severities of misalignment and unbalance, as the literature says that both conditions present similar frequency components. The implementation of the 2D-DOST over the TFDs helped the classification task with minimal computational load; this could be of great benefit when the use of more established methods, like the ones compared in this work, do not reach optimal accuracy levels, improving the fault diagnosis, even when other techniques struggle to identify as many and diverse conditions as reported in this research.

The comparison to the current signal analysis employing the proposed methodology shows that the proposal is suitable for application on different signals as the performance achieved when using current signals with STFT images is similar to that of the stray flux and different TFDs, even with reduced data. The CNN model, significantly smaller than most of the extensively reported models in the literature, performed adequately in all cases, allowing for a good performance during the tests. The information displayed in

Table 13 shows that the results obtained fall within the range presented in the literature, taking into account the amount of conditions under detection and the difference in size and parameters for all CNN models, as well as the validity of the approach, as a way to improve the classification performance by using a tool that facilitates the automatic feature extraction performed by a CNN model considerably smaller than some of the preferred nets, as mentioned in Section Experimental Setup.

5. Conclusions

This work focused on analyzing the effect of the 2D-DOST, an image processing tool used in the medical field as a texture analysis technique capable of improving condition diagnosis, on the fault detection in IMs. To contrast the influence of this technique, RGB and grayscale TFDs of the STFT, CWT, FSST, and ST-MUSIC were used as baselines, and their classification performance was compared to that of the TFDs after a 2D-DOST treatment. The results showed using RGB images achieved good accuracy, while grayscale pictures reduced the performance of the CNN model; in contrast, the results from the 2D-DOST batch improved the RGB results with minimal changes in computational load. The use of image processing tools on the inputs to CNN models could greatly benefit the condition monitoring and fault detection area, as they could facilitate the extraction of features, improving the overall accuracy and reducing the need for larger models that require more resources. This methodology showed good performance for identifying eleven faulty conditions of five different natures and various severities, proving that it could be applied to different scenarios. Additionally, the application of the method to TFDs of current signals generated using STFT showed similar results to the stray flux analysis, demonstrating the applicability of the proposal to other signals, even with a reduced number of samples.

Further research is necessary to understand the mechanisms that influence the performance of the TFDs when the 2D-DOST is used, as well as to compare whether the results extend to other transforms or 2D representations, or if similar image processing tools have similar effects. Prospective work includes the automation of the process to generate an online system that could identify the presence of faults on working machines to allow for early detection and corrective maintenance measures, reducing the impact of the faults, as well as expanding the results to consider early fault detection and progressive severity increments.