Bifurcation Analysis of a Semilinear Generalized Friction System with Time-Delayed Feedback Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Establishment of the Model

- (H1)

- ,

- (H2)

- ,

- (H3)

- ,

- (H4)

- .

- (1) If is satisfied, then the system has a unique trivial equilibrium ;

- (2) If is satisfied, then the system has a semi-trivial equilibrium .

3. Stability Analysis of the Semilinear Parabolic Friction System

- (1) If is satisfied, and , then , and all the roots of Equation (7) have negative real parts;

- (2) If is satisfied, or , then , and Equation (7) has at least one root with positive real part.

- (1) If is satisfied, and , then system (6) is locally asymptotically stable at

- (2) If is satisfied, or , then system (6) is unstable at

4. Hopf Bifurcation Analysis of the Friction System with Time-Delayed Feedback Control

4.1. Existence of Hopf Bifurcation

- (A1)

- ;

- (A2)

- ;

- (A3)

- ;

- (A4)

- ;

- (A5)

- .

- (1)When , all the characteristic roots of Equation (10) have negative real parts, and system (5) is locally asymptotically stable at ;

- (2) is not the root of Equation (10).

- (1) If , and hold, then Equation (10) has two pairs of pure imaginary roots at for , and Equation (10) has no pure imaginary root for ;

- (2) If , and hold, then Equation (10) has no pure imaginary root for ;

- (3) If , and hold, then Equation (10) has a pair of pure imaginary roots at for , and Equation (10) has two pairs of pure imaginary roots at for ;

- (4) If , and hold, then for , Equation (10) has a pair of pure imaginary roots at ; for , Equation (10) has no pure imaginary root;

- (5) If , and hold, then when , Equation (10) has a pair of pure imaginary roots at ; when , Equation (10) has two pairs of pure imaginary roots at ;

- (6) If , and hold, then for , Equation (10) has a pair of pure imaginary roots at ; for , Equation (10) has no pure imaginary root;

- (7) If , and hold, then when , Equation (10) has a pair of pure imaginary roots at ; when or , Equation (10) has two pairs of pure imaginary roots at ;

- (8) If , and hold, then for , Equation (10) has a pair of pure imaginary roots at ; for or , Equation (10) has no pure imaginary root,

- (1) If , then the system is locally asymptotically stable for , and unstable for . A family of nonhomogeneous bifurcating periodic solutions occur nearby, for ;

- (2) If , then there exists a positive integer k, such that the system undergoes k times stability transitions (stable → unstable → stable → unstable) as the time delay parameter varies, i.e., whenthe system is locally asymptotically stable, and whenthe system is unstable;

- (3) When , Hopf bifurcation occurs at , and the bifurcating periodic solutions are nonhomogeneous.

4.2. Stability and Direction of Hopf Bifurcation

- (1) If , then the Hopf bifurcation is forward (backward), i.e.,the bifurcation periodic solutions exist in the right (left) neighborhood of ;

- (2) If , the bifurcating periodic solutions are asymptotically stable (unstable) on the central manifold;

- (3) If , the period of the periodic solutions increases (decreases).

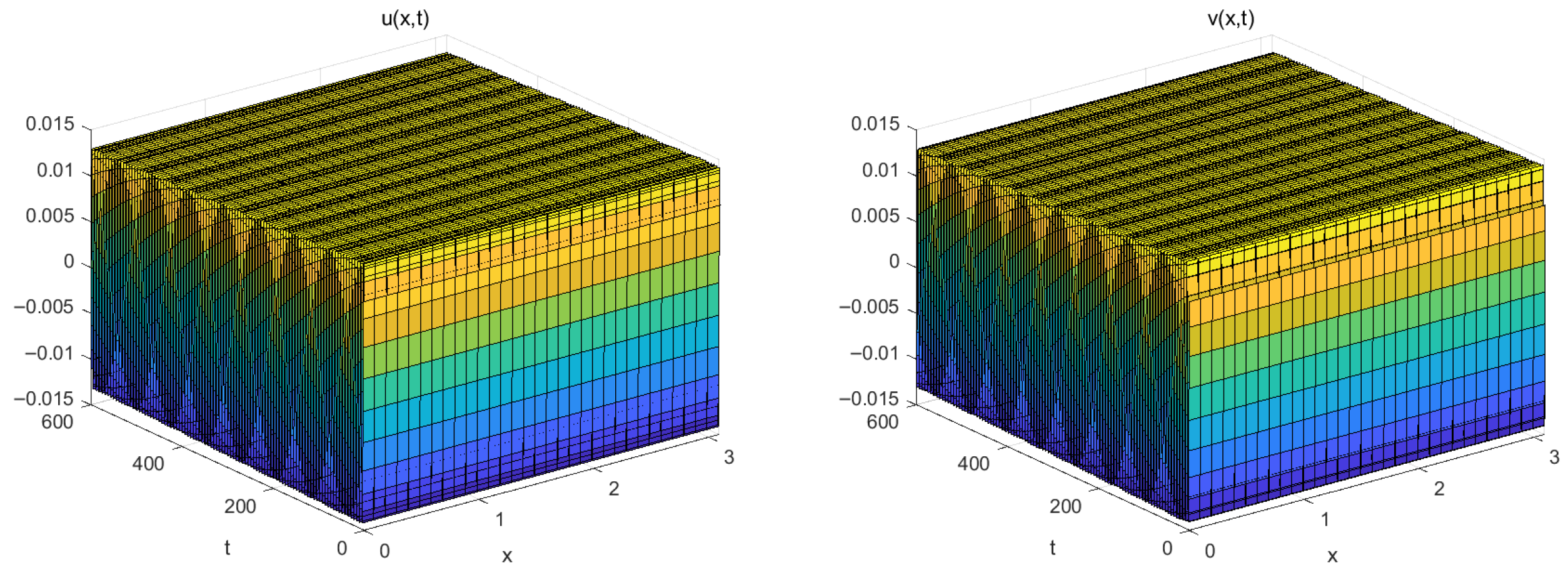

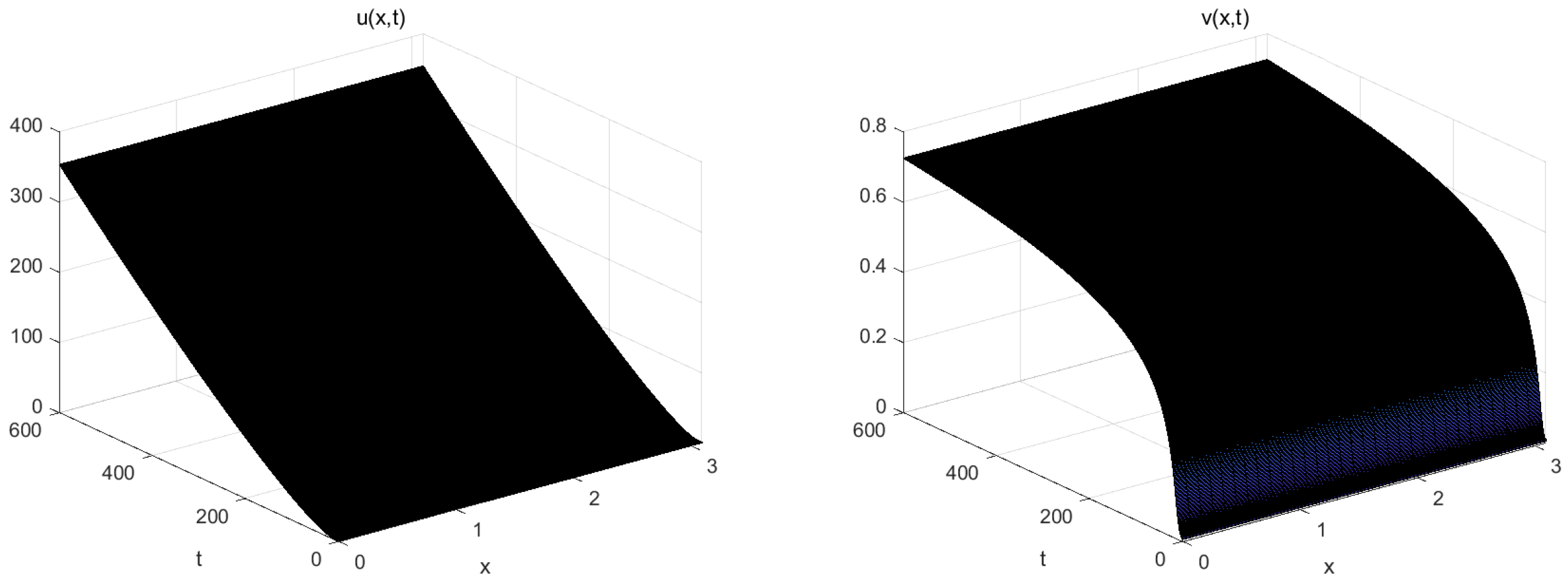

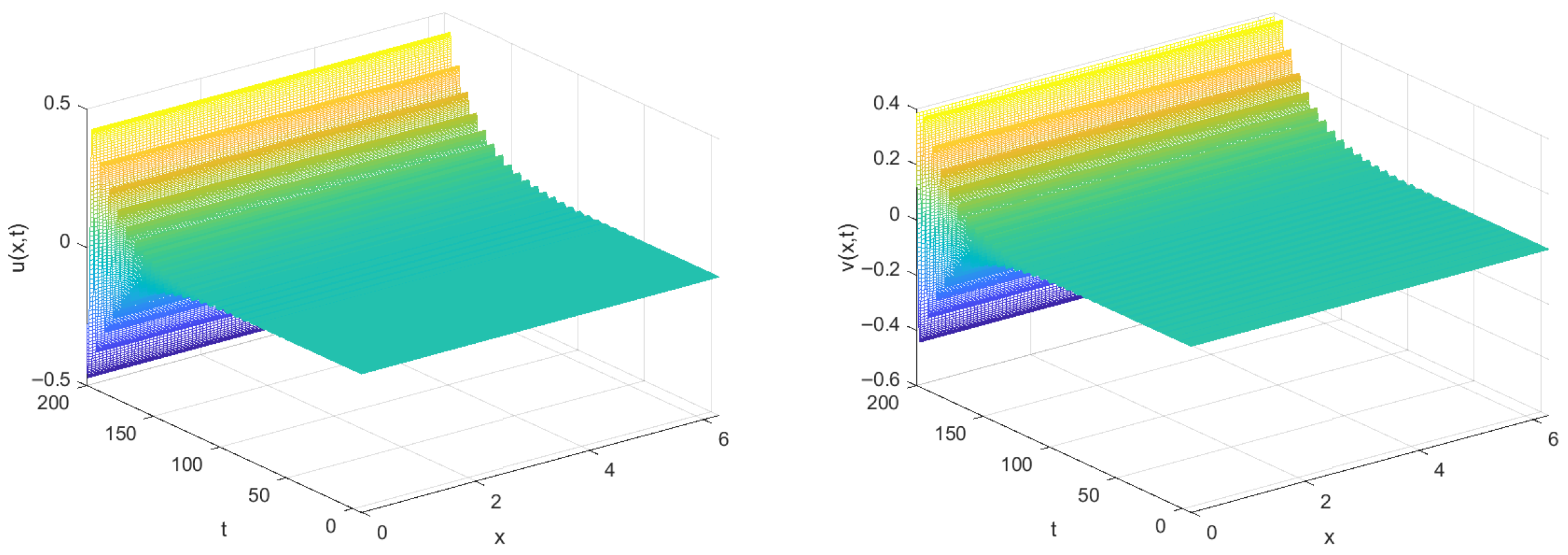

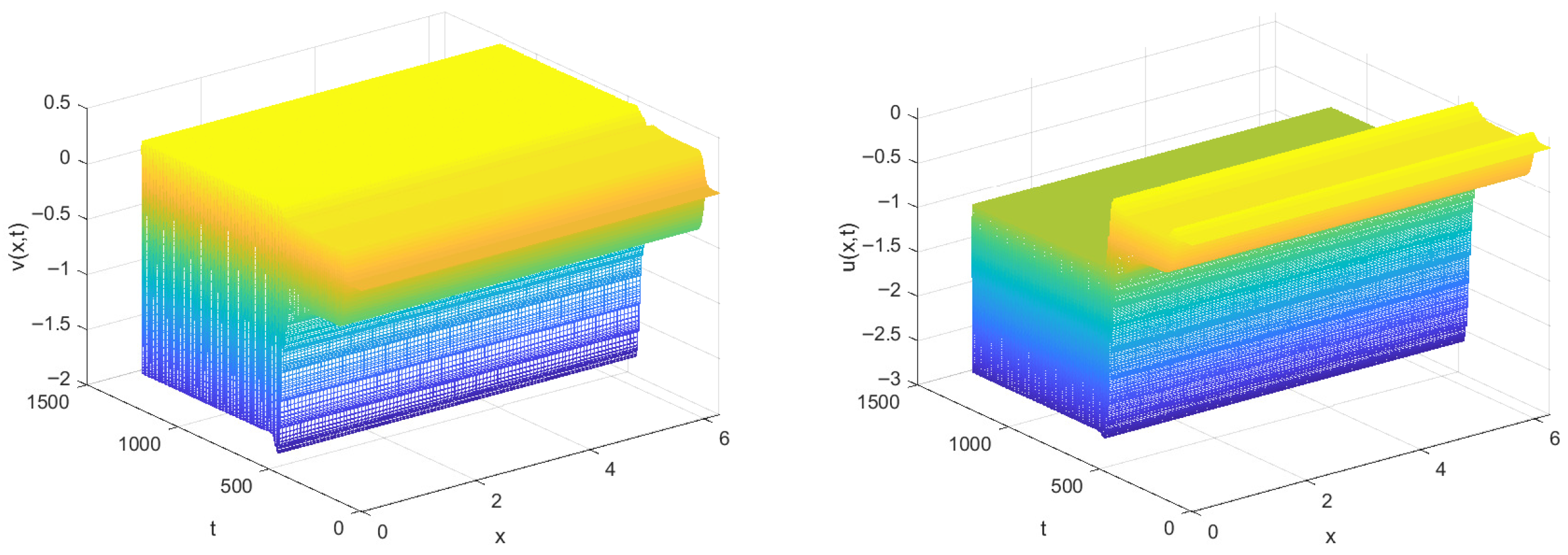

5. Numerical Simulations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canudas, d.W.C.; Olsson, H.; Astrom, K.J. A new model for control of systems with friction. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1995, 40, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, P.; Hayward, V.; Armstrong, B. Single state elastoplastic friction models. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2002, 47, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, N.; Oestreich, M.; Popp, K. On the Modeling of Friction Oscillators. J. Sound Vib. 1998, 216, 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampaert, V.; Swevers, J.; Al-Bender, F. Modification of the Leuven integrated friction model structure. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2002, 47, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampaert, V.; Al-Bender, F.; Swevers, J. A generalized Maxwell-slip friction model appropriate for control purposes. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE International Workshop on Workload Characterization (IEEE Cat. No. 03EX775), St. Petersburg, Russia, 20–22 August 2003; Volume 4, pp. 1170–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Mcmillan, A.J. A Non-Linear Friction Model For Self-Excited Vibrations. J. Sound Vib. 1997, 205, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panovko, Y.G.; Gubanova, I.I. Stability and Oscillations of Elastic Systems, Paradoxes. In Fallacies and New Concepts; Consultants Bureau: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ruina, A. Slip Instability and State Variable Friction Laws. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1983, 881, 10359–10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swevers, J.; Al-Bender, F. An integrated friction model structure with improved presliding behavior for accurate friction compensation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2000, 45, m675–m686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, J.J. Using Fast Vibrations to Quench Frictioninduced Oscillations. J. Sound Vib. 1999, 228, 1079–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.K. Theory of Functional Differential Equations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Maccari, A. Vibration control for the primary resonance of a cantilever beam by a time delay state feedback. J. Sound Vib. 2003, 259, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccari, A. Vibration control for parametrically excited Linard systems. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2006, 41, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ji, J.C.; Hansen, C.H. The response of a Duffing-van der Pol oscillator under delayed feedback control. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 291, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Wei, J.; Shi, J. Bifurcation and spatiotemporal patterns in a homogeneous diffusive predator-prey system. J. Differ. Equ. 2009, 246, 1944–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyragas, K. Control of Chaos by Self-Controlling Feedback. Phys. Lett. A 1992, 170, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wei, J. Bifurcation analysis for Chen’s system with delayed feedback and its application to control of chaos. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2004, 22, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J. Stability and bifurcation analysis in a magnetic bearing system with time delays. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2005, 26, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Jiang, W. Stability and bifurcation analysis in Van der Pol’s oscillator with delayed feedback. J. Sound Vib. 2005, 283, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, T. Stability and Bifurcation for a Delayed Predator-Prey Model and the Effect of Diffusion. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2001, 254, 433–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.T.; Yan, X.P.; Zhang, C.H. Stability and Hopf bifurcation for a delayed cooperation diffusion system with Dirichlet boundary conditions. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2008, 38, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Li, W.T. Bifurcation and global periodic solutions in a delayed facultative mutualism system. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2007, 227, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Bhattacharya, B.; Wahi, P. A comparative study on the control of friction-driven oscillations by time-delayed feedback. Nonlinear Dyn. 2010, 60, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassard, B.D.; Kazarino, N.D.; Wan, Y.H. Theory and Applications of Hopf Bifurcation; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. Theory and Applications of Partial Functional Differential Equations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, T. Normal Forms and Hopf Bifurcation for Partial Differential Equations with Delays. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2000, 352, 2217–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, X. Bifurcation Analysis of a Semilinear Generalized Friction System with Time-Delayed Feedback Control. Axioms 2026, 15, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms15010025

Liu H, Li Y, Liu X. Bifurcation Analysis of a Semilinear Generalized Friction System with Time-Delayed Feedback Control. Axioms. 2026; 15(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms15010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Haicheng, Yanfeng Li, and Xuejiao Liu. 2026. "Bifurcation Analysis of a Semilinear Generalized Friction System with Time-Delayed Feedback Control" Axioms 15, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms15010025

APA StyleLiu, H., Li, Y., & Liu, X. (2026). Bifurcation Analysis of a Semilinear Generalized Friction System with Time-Delayed Feedback Control. Axioms, 15(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms15010025