Inertial Algorithm for Best Proximity Point, Split Variational Inclusion and Equilibrium Problems with Application to Image Restorations

Abstract

1. Introduction and Preliminaries

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- ,

- (iii)

- ,

- (iv)

- .

- (i)

- If there exists a constant such that , then the sequence is bounded.

- (ii)

- If and , then as .

- A mapping L is maximal monotone if and only if is a single value.

- if and only if

- The SVIP is equivalent to the following:Find with

| Algorithm 1: AA-iteration |

Initialization: Assume , . Set any ; calculate in the following ways: |

| Algorithm 2: Byrne’s algorithm |

Initialization: Suppose that is a sequence in , and where . For , calculate as follows: |

| Algorithm 3: Wangkeeree’s algorithm |

Initialization: Let , and , where K is as given above. Choose any , find as: |

| Algorithm 4: Suntai’s algorithm |

Initialization: Let with and . Set any , find as follows: |

| Algorithm 5: Husain’s algorithm |

Initialization: Let , . Set any , calculate as follows: |

2. Convergence Analysis

- ,

- ,

- ,

- the function is lower semi-continuous and convex, for all .

- (1)

- is single-valued and firmly nonexpansive.

- (2)

- The fixed point of solve the .

- (3)

- The fixed point set of the mapping is convex and closed.

Proposed Algorithm

| Algorithm 6: Proposed algorithm |

Step 0. Initialize and a non-negative parameter . Set . Step 1. For the th and nth iterates, select satisfying , where Step 2. Calculate Step 3. Compute which satisfies Step 4. Find Step 5. Find Step 6. Find |

- (i)

- with and .

- (ii)

- with .

- (iii)

- is fixed, , and such that

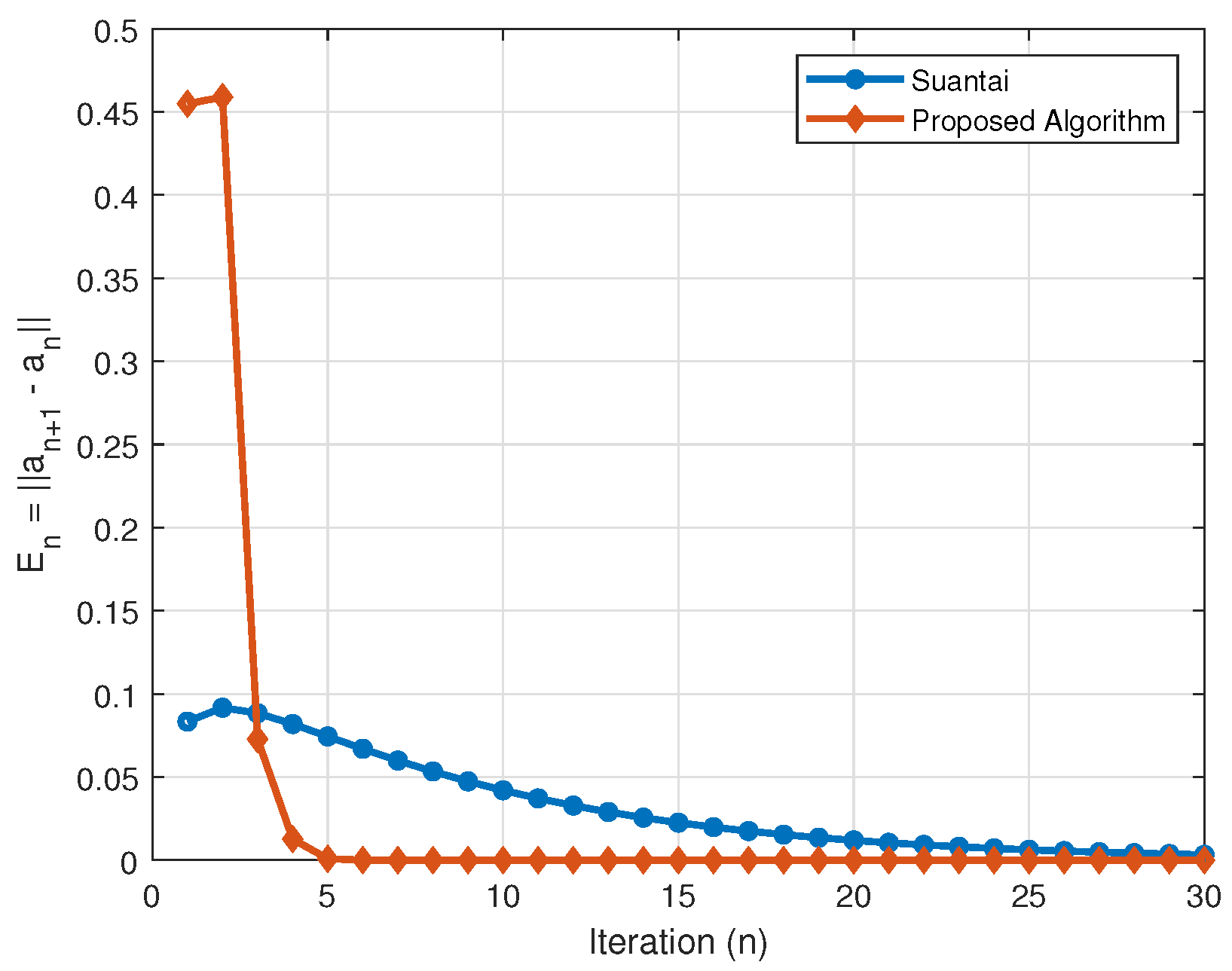

3. Numerical Experiments

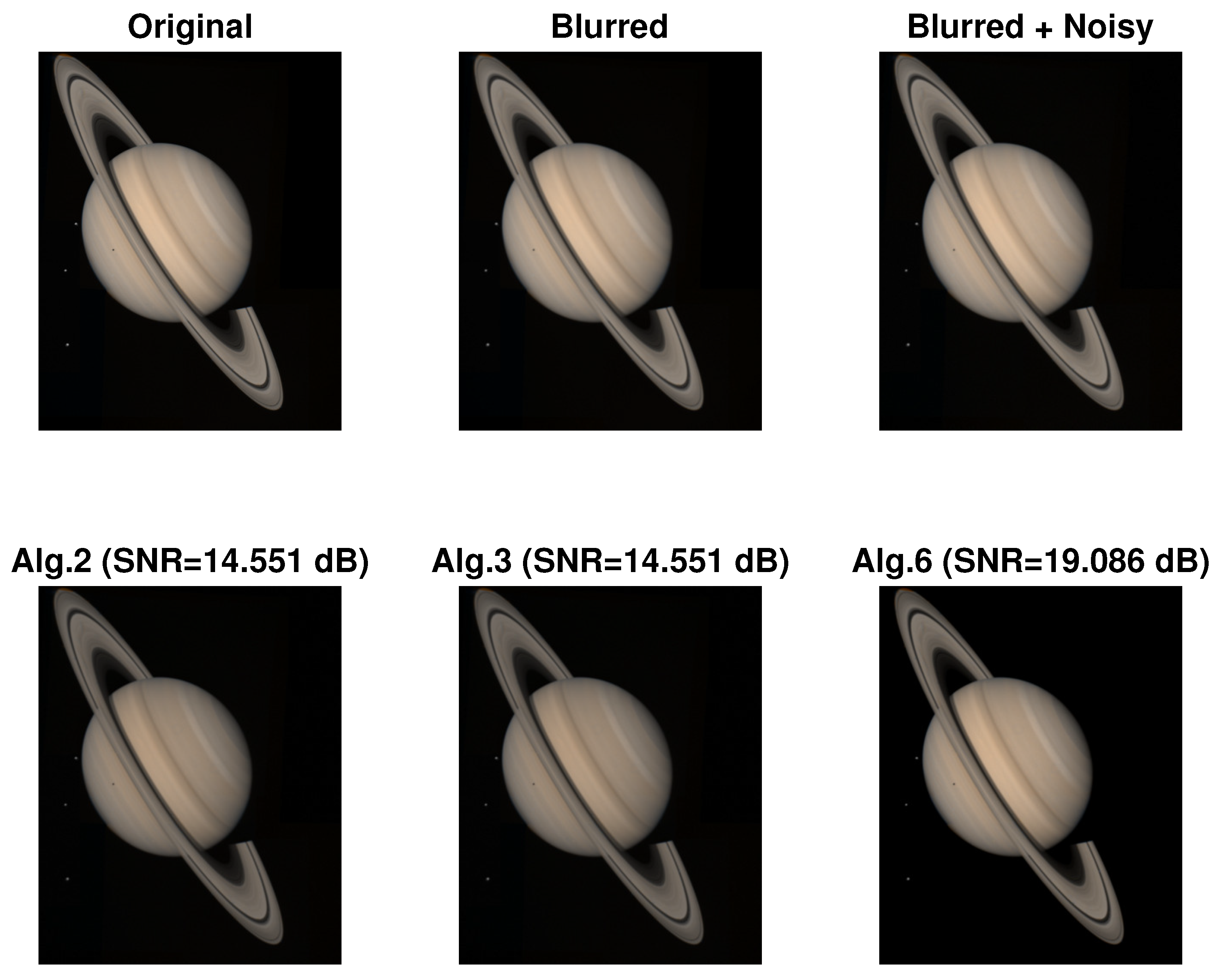

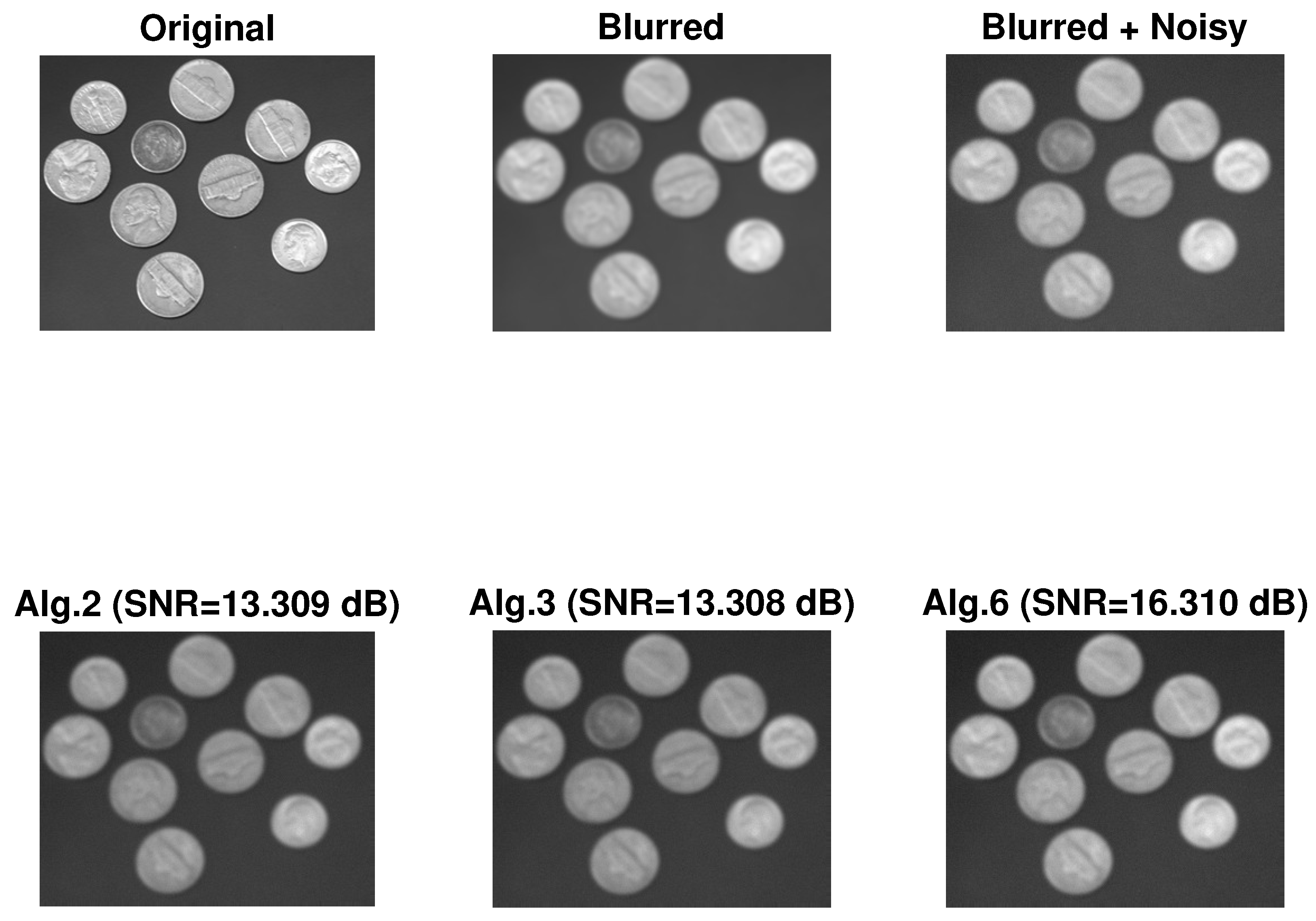

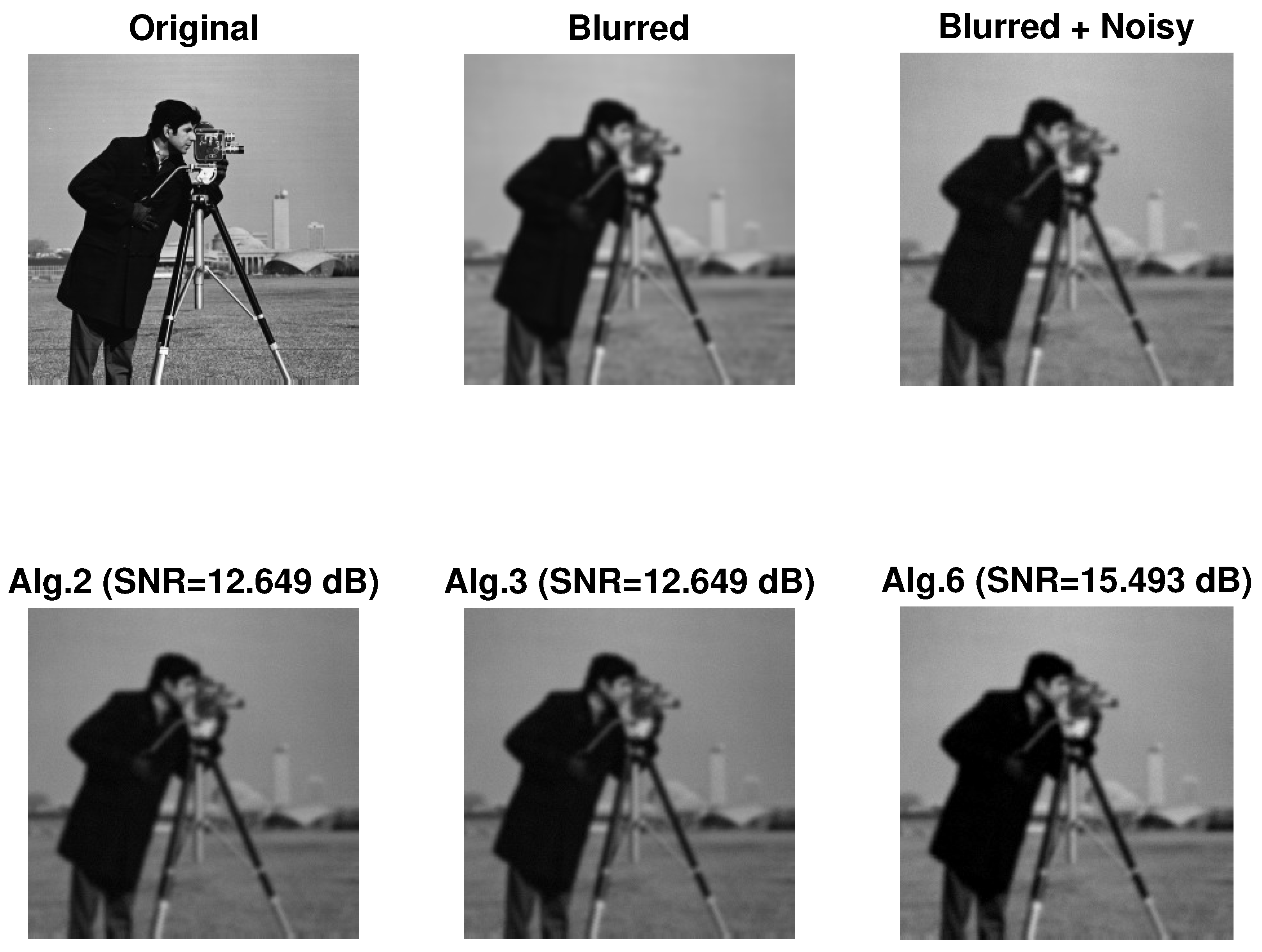

4. Application to Image Restoration

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauschke, H.H.; Borwein, J.M. On projection algorithms for solving convex feasibility problems. SIAM Rev. 1996, 38, 367–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X. A primal–dual fixed point algorithm for convex separable minimization with applications to image restoration. Inverse Probl. 2013, 29, 025011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, K.; Reich, S. Uniform Convexity, Hyperbolic Geometry, and Non-Expansive Mappings; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, F. Best Approximation in Inner Product Spaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cho, Y.J. Split equilibrium, variational inequality and fixed point problems for multi-valued mappings in Hilbert spaces. Appl. Comput. Math 2018, 17, 271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.P.; O’Regan, D.; Sahu, D.R. Fixed Point Theory for Lipschitzian-Type Mappings with Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, C.-S. Strong convergence theorems for the split variational inclusion problem in Hilbert spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2013, 2013, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osilike, M.O.; Igbokwe, D.I. Weak and strong convergence theorems for fixed points of pseudocontractions and solutions of monotone type operator equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 2000, 40, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maing, P.-E. Approximation methods for common fixed points of nonexpansive mappings in Hilbert spaces. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 325, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saejung, S.; Yotkaew, P. Approximation of zeros of inverse strongly monotone operators in Banach spaces. Nonlinear Anal. 2012, 75, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, A. Existence and regularity of solutions to nonlinear degen-erate evolutionary variational inequalities with applications to dynamic network equilibrium problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2009, 208, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dafermos, S.; Nagurney, A. A network formulation of market equilibrium problems and variational inequalities. Oper. Res. Lett. 1984, 3, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R. Coincidence theorem and existence theorems of solutions for a system of Ky Fan type minimax inequalities in FC-spaces. Adv. Fixed Point Theory 2012, 2, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Cho, S.Y.; Kang, S.M. Strong convergence of shrinking projection methods for quasi-ϕ-nonexpansive mappings and equilibrium problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2010, 234, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq Basha, S. Best proximity points: Optimal solutions. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2011, 151, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq Basha, S. Best proximity points: Global optimal approximate solutions. J. Glob. Optim. 2011, 49, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabeleh, M. Best proximity point theorems via proximal non-self mappings. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2015, 164, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparatulatorn, R.; Suantai, S. A new hybrid algorithm for global mini-mization of best proximity points in Hilbert spaces. Carpath. J. Math. 2019, 35, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunlue, N.; Suantai, S. Hybrid algorithm for common best proximity points of some generalized nonself nonexpansive mappings. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2018, 41, 7655–7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaoui, A.; Park, C.; Melliani, S. New best proximity point results via simulation functions in fuzzy metric spaces. Bol. Soc. Paran. Mat. 2025, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, S.; Furkan, M.; Khairoowala, M.U. Strong convergence of inertial shrinking projection method for split best proximity point problem and mixed equilibrium problem. J. Anal. 2025, 33, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. Iterative oblique projection onto convex sets and the split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2002, 18, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combettes, P.L. The convex feasibility problem in image recovery. Adv. Imaging Electron Phys. 1996, 95, 155–270. [Google Scholar]

- Censor, Y.; Gibali, A.; Reich, S. Algorithms for the split variational inequality problem. Numer. Algorithms 2012, 59, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. Convergence analysis of a new iterative algorithm for solving split variational inclusion problems. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2020, 16, 945–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.S. Best proximity point theorems for non-self mappings. Fixed Point Theory 2013, 14, 447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, B. Fixed points of nonexpanding maps. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1976, 73, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iiduka, H. Fixed point optimization algorithm and its application to network bandwidth allocation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2012, 236, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, K.R.; Rizvi, S.H. An iterative method for split variational inclusion problem and fixed point problem for a nonexpansive mapping. Optim. Lett. 2014, 8, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudafi, A. Viscosity approximation methods for fixed-points problems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2000, 241, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.W.; Abbas, M. A self-adaptive viscosity algorithm for split fixed point problems and variational inequality problems in Banach spaces. J. Non. Con. Anal. 2023, 24, 341–361. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, M.; Asghar, M.W.; De la Sen, M. Approximation of the solution of delay fractional differential equation using AA-iterative scheme. Mathematics 2022, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.W.; Abbas, M.; Eyni, D.C.; Omaba, M.E. Iterative approximation of fixed points of generalized αm-nonexpansive mappings in modular spaces. AIMS Math. 2023, 8, 26922–26944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanoom, C.; Gebrie, A.G.; Grace, T. The convergence of AA-iterative algorithm for generalized AK-α-nonexpansive mappings in Banach spaces. Sci. Technol. Asia 2023, 28, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Beg, I.; Abbas, M.; Asghar, M.W. Convergence of AA-iterative algorithm for generalized α-nonexpansive mappings with an application. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Ciobanescu, C.; Asghar, M.W.; Omame, A. Solution approximation of fractional boundary value problems and convergence analysis using AA-iterative scheme. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 13129–13158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.; Censor, Y.; Gibali, A.; Reich, S. The split common null point problem. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2012, 13, 759–775. [Google Scholar]

- Wangkeeree, R.; Rattanaseeha, K.; Wangkeeree, R. The general iterative methods for split variational inclusion problem and fixed point problem in Hilbert spaces. J. Comput. Anal. Appl 2018, 25, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Suantai, S.; Tiammee, J. The shrinking projection method for solving split best proximity point and equilibrium problems. Filomat 2021, 35, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, S.; Khan, F.A.; Furkan, M.; Khairoowala, M.U.; Eljaneid, N.H. Inertial projection algorithm for solving split best proximity point and mixed equilibrium problems in Hilbert spaces. Axioms 2022, 11, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.W.; Abbas, M.; Rouhani, B.D. The AA-Viscosity Algorithm for Fixed-Point, Generalized Equilibrium and Variational Inclusion Problems. Axioms 2024, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chandok, S. Split fixed point problems for quasi-nonexpansive map-pings in Hilbert spaces. Politehn. Univ. Bucharest Sci. Bull. Ser. A Appl. Math. Phys. 2024, 86, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Aubin, J.-P. Optima and Equilibria: An Introduction to Nonlinear Analysis; Springer Science Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 140. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.; Teboulle, M. A fast iterative shrinkage-thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2009, 2, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. Iter | Husain et al. [40] | Proposed Algorithm | Husain et al. [40] | Proposed Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.000000 | 2.000000 | −2.000000 | −2.000000 |

| 2 | 1.500000 | 1.500000 | −1.500000 | −1.500000 |

| 3 | 0.976922 | 0.305917 | −0.976922 | −0.305917 |

| 4 | 0.593834 | 0.054838 | −0.593834 | −0.054838 |

| 5 | 0.349919 | 0.004065 | −0.349919 | −0.004065 |

| 6 | 0.202574 | −0.002829 | −0.202574 | 0.002829 |

| 7 | 0.115941 | −0.001055 | −0.115941 | 0.001055 |

| 8 | 0.065829 | −0.000063 | −0.065829 | 0.000063 |

| 9 | 0.037157 | 0.000066 | −0.037157 | −0.000066 |

| 10 | 0.020878 | 0.000023 | −0.020878 | −0.000023 |

| 11 | 0.011689 | 0.000001 | −0.011689 | −0.000001 |

| 12 | 0.006525 | −0.000002 | −0.006525 | 0.000002 |

| 13 | 0.003634 | −0.000001 | −0.003634 | 0.000001 |

| 14 | 0.002020 | −0.000000 | −0.002020 | 0.000000 |

| 15 | 0.001120 | 0.000000 | −0.001120 | −0.000000 |

| 16 | 0.000621 | 0.000000 | −0.000621 | −0.000000 |

| 17 | 0.000343 | −0.000000 | −0.000343 | 0.000000 |

| 18 | 0.000190 | −0.000000 | −0.000190 | 0.000000 |

| 19 | 0.000105 | −0.000000 | −0.000105 | 0.000000 |

| 20 | 0.000058 | 0.000000 | −0.000058 | −0.000000 |

| 21 | 0.000032 | 0.000000 | −0.000032 | −0.000000 |

| 22 | 0.000018 | 0.000000 | −0.000018 | −0.000000 |

| 23 | 0.000010 | −0.000000 | −0.000010 | 0.000000 |

| 24 | 0.000005 | −0.000000 | −0.000005 | 0.000000 |

| 25 | 0.000003 | −0.000000 | −0.000003 | 0.000000 |

| 26 | 0.000002 | 0.000000 | −0.000002 | −0.000000 |

| 27 | 0.000001 | 0.000000 | −0.000001 | −0.000000 |

| 28 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | −0.000000 | −0.000000 |

| 29 | 0.000000 | −0.000000 | −0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| 30 | 0.000000 | −0.000000 | −0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| No. Iter | Suantai [39] | Proposed Algorithm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | (0, 1.0000) | – | (0, 1.0000) | – |

| 1 | (0, 0.916667) | 0.0833333 | (0, 1) | 0.454861 |

| 2 | (0, 0.825) | 0.0916667 | (0, 0.545139) | 0.458831 |

| 3 | (0, 0.736607) | 0.0883929 | (0, 0.0863084) | 0.072751 |

| 4 | (0, 0.654762) | 0.0818452 | (0, 0.0135574) | 0.0126738 |

| 5 | (0, 0.580357) | 0.0744048 | (0, 0.000883564) | 0.000835067 |

| 6 | (0, 0.513393) | 0.0669643 | (0, 4.84972 × 10−5) | 4.67119 × 10−5 |

| 7 | (0, 0.453497) | 0.0598958 | (0, 1.78533 × 10−6) | 1.72936 × 10−6 |

| 8 | (0, 0.400144) | 0.0533526 | (0, 5.59731 × 10−8) | 5.4418 × 10−8 |

| 9 | (0, 0.352759) | 0.0473855 | (0, 1.55506 × 10−9) | 1.51619 × 10−9 |

| 10 | (0, 0.310764) | 0.0419951 | (0, 3.88768 × 10−11) | 3.79933 × 10−11 |

| 11 | (0, 0.273607) | 0.0371565 | (0, 8.83564 × 10−13) | 8.65157 × 10−13 |

| 12 | (0, 0.240774) | 0.0328329 | (0, 1.84076 × 10−14) | 1.80536 × 10−14 |

| 13 | (0, 0.211792) | 0.0289821 | (0, 3.53992 × 10−16) | 3.47671 × 10−16 |

| 14 | (0, 0.186231) | 0.0255611 | (0, 6.32129 × 10−18) | 6.21593 × 10−18 |

| 15 | (0, 0.163703) | 0.022528 | (0, 1.05355 × 10−19) | 1.03709 × 10−19 |

| 16 | (0, 0.14386) | 0.0198428 | (0, 1.64617 × 10−21) | 1.62196 × 10−21 |

| 17 | (0, 0.126392) | 0.0174688 | (0, 2.42084 × 10−23) | 2.38721 × 10−23 |

| 18 | (0, 0.11102) | 0.015372 | (0, 3.36227 × 10−25) | 3.31803 × 10−25 |

| 19 | (0, 0.097498) | 0.0135216 | (0, 4.42404 × 10−27) | 4.36874 × 10−27 |

| 20 | (0, 0.085608) | 0.01189 | (0, 5.53005 × 10−29) | 5.46422 × 10−29 |

| 21 | (0, 0.0751559) | 0.0104521 | (0, 6.5834 × 10−31) | 6.50859 × 10−31 |

| 22 | (0, 0.0659702) | 0.00918572 | (0, 7.48113 × 10−33) | 7.39982 × 10−33 |

| 23 | (0, 0.0578994) | 0.00807082 | (0, 8.13167 × 10−35) | 8.04696 × 10−35 |

| 24 | (0, 0.0508096) | 0.00708972 | (0, 8.47049 × 10−37) | 8.38578 × 10−37 |

| 25 | (0, 0.044583) | 0.00622667 | (0, 8.47049 × 10−39) | 8.38904 × 10−39 |

| 26 | (0, 0.0391152) | 0.00546772 | (0, 8.1447 × 10−41) | 8.06928 × 10−41 |

| 27 | (0, 0.0343147) | 0.00480051 | (0, 7.54139 × 10−43) | 7.47405 × 10−43 |

| 28 | (0, 0.0301006) | 0.00421409 | (0, 6.73338 × 10−45) | 6.67534 × 10−45 |

| 29 | (0, 0.0264018) | 0.00369881 | (0, 5.80464 × 10−47) | 5.75627 × 10−47 |

| 30 | (0, 0.0231557) | 0.00324613 | (0, 4.8372 × 10−49) | 4.79819 × 10−49 |

| … | … | … | … | … |

| 145 | (0, 5.54148 × 10−9) | 7.88532 × 10−10 | (0, 0) | 0 |

| 146 | (0, 4.85116 × 10−9) | 6.90321 × 10−10 | (0, 0) | 0 |

| 147 | (0, 4.24682 × 10−9) | 6.04339 × 10−10 | (0, 0) | 0 |

| 148 | (0, 3.71775 × 10−9) | 5.29065 × 10−10 | (0, 0) | 0 |

| 149 | (0, 3.25459 × 10−9) | 4.63165 × 10−10 | (0, 0) | 0 |

| 150 | (0, 2.84912 × 10−9) | 4.05472 × 10−10 | (0, 0) | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbas, M.; Asghar, M.W.; Alotaibi, A.H. Inertial Algorithm for Best Proximity Point, Split Variational Inclusion and Equilibrium Problems with Application to Image Restorations. Axioms 2025, 14, 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14120924

Abbas M, Asghar MW, Alotaibi AH. Inertial Algorithm for Best Proximity Point, Split Variational Inclusion and Equilibrium Problems with Application to Image Restorations. Axioms. 2025; 14(12):924. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14120924

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Mujahid, Muhammad Waseem Asghar, and Ahad Hamoud Alotaibi. 2025. "Inertial Algorithm for Best Proximity Point, Split Variational Inclusion and Equilibrium Problems with Application to Image Restorations" Axioms 14, no. 12: 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14120924

APA StyleAbbas, M., Asghar, M. W., & Alotaibi, A. H. (2025). Inertial Algorithm for Best Proximity Point, Split Variational Inclusion and Equilibrium Problems with Application to Image Restorations. Axioms, 14(12), 924. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms14120924