3.1. s-m-Hypersystems and s-Prime Hyperideals

In this section, we will investigate the correspondence of s-m-systems in a hyperring and provide examples.

Definition 4.

Let R be a Krasner hyperring and S a subset of R. For every , if there exists a multiplicatively closed subset of S such that , then the set S is called an s-m-hypersystem. Here, the set is called the kernel set of S.

Example 6.

Let be a ring, with the multiplicative group, and let 3

and 4

be orthogonal idempotent elements. Define . Then the set R, equipped with the operations “⊕”

and “·”

whose operation tables are given below, forms a Krasner hyperring.| ⊕ | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | · | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

For the given R Krasner hyperring, let be multiplicatively closed subset of .

For , and

For , and Therefore, S is an s-m-hypersystem.

Example 7.

Consider the hyperring given in Example 2 and . Let be a multiplicatively closed subset of S. For , and and for all , and , hence S is an s-m-hypersystem and the set is the core of S.

Example 8.

Consider the hyperring as defined in Example 6, let us take the subset of R. The multiplicatively closed subsets of the set S are: , , , and .

For , then , and .

For , then and . Thus, since there is no multiplicatively closed subset such that for every , S is not an s-m-hypersystem.

Definition 5.

Let R be a Krasner hyperring and P be a hyperideal of R. If the set is an s-m-hypersystem, then P is called an s-prime hyperideal.

Example 9.

Take the Krasner hyperring in Example 6 and hyperideal of R, we have . Let be a multiplicatively closed subset of . For , , then and for , and . thus is an s-m-hypersystem. By definition, is an s-prime hyperideal of R.

Example 10.

Let us consider the Krasner hyperring constructed with the set , as in Example 6. For the ideal , we have The multiplicatively closed subsets of can be as follows Now consider the following:

For , thus and

For and . Therefore, is not an -hypersystem. Since is not an -hypersystem, it follows that I is not an s-prime hyperideal.

Definition 6.

Let R be a Krasner hyperring, and let be a multiplicatively closed subset. Suppose that P is a hyperideal of R such that . If for all , the condition implies that there exists an element such that either or , then P is called an S-prime hyperideal.

Example 11.

In the Krasner hyperring given in Example 2, let be a hyperideal of R. Consider the subset , which is multiplicatively closed. We observe that . For all , if , then it must be that . If either or , then for every , we have or . In all other cases, according to the multiplication table, holds only when either or . In such cases, since , we have either or . Therefore, P is an S-prime hyperideal.

Remark 1.

When we take the hyperideal of the Krasner hyperring given in Example 11, but and . Therefore, P is not a prime hyperideal. This provides an example of an S-prime hyperideal which is not a prime hyperideal.

Example 12.

In the Krasner hyperring given in Example 3, let be a hyperideal of R. Consider the subset , which is multiplicatively closed. For , we have . However, the following hold Therefore, P is not an S-prime hyperideal.

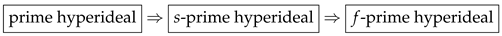

3.2. f-hypersystems and f-prime Hyperideals of Krasner Hyperrings

In this section, we present the generalization of the definitions of

f-systems and

f-prime ideals introduced to the setting of Krasner hyperrings by Murata et al. [

22]. Throughout this section, let

R be a commutative and unital Krasner hyperring. For an arbitrary element

, the hyperideal determined singly by

a and satisfying the following conditions will be denoted by

.

- (i)

.

- (ii)

For any hyperideal K, if , then .

Let us provide examples of the ideal

satisfying the above conditions. Let

R be a Krasner hyperring and

. For an arbitrary element

, the hyperideal

is an example of such a hyperideal because

- (1)

it follows that since .

- (2)

Given any

and since

then there exist

and

such that

. Therefore,

Consequently, the hyperideal defined by satisfies conditions (i) and (ii). Furthermore, it is clear that the conditions are satisfied when .

Definition 7.

Let R be a Krasner hyperring and let . If there exists a multiplicatively closed subset such that for every , then S is called an f-hypersystem.

Example 13.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed with the set as in Example 2. Let be a subset of R. Consider the multiplicatively closed subset , and define for every the hyperideal . Then we have:

If , then .

If , then .

Hence, since for every , , the set S is an f-hypersystem.

From the definition of the f-hypersystem, if , then every s-m-hypersystem becomes an f-hypersystem, i.e., under this assumption, coincides with the smallest hypersystem generated by s and therefore all closure and structural conditions required in the definition of an s-m-hypersystem naturally satisfy the conditions prescribed for an f-hypersystem. However, not every f-hypersystem is necessarily an s-m-hypersystem. The following Example 14 illustrates this.

Example 14.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed with the set as in Example 5. Let be a subset of and the multiplicatively closed subset . We have and . Therefore, S is not an s-m-hypersystem. However, if then for all , hence , thus S is an f-hypersystem.

Example 15.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed with the set as in Example 6. Let be a subset. Assume and consider the multiplicatively closed subset .

For , we have , so .

For , we have , so .

For , we have , so

Therefore, S is an f-hypersystem.

Example 16.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed with the set as in Example 5. Let be a subset of . Assume and consider the multiplicatively closed subset . For , we have and . Therefore, S is not an f-hypersystem.

Definition 8.

Let P be a hyperideal in the hyperring R. If is an f-hypersystem, then P is called an f-prime hyperideal.

Example 17.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed with the set as in Example 6. Let be a prime hyperideal. Then, . Consider the multiplicatively closed subset and for each define .

Then for all :

For , we have , andthus . For , we have , andthus . For , we have , andthus .

Therefore, is an f-hypersystem, and consequently, P is an f-prime hyperideal.

Example 18.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed with the set as in Example 3. Let be a prime hyperideal. Then, . Consider the multiplicatively closed subset , and for each define Then:

If , then . Hence, If , then . Therefore,Consequently, for every , there exists a multiplicatively closed subset such that . Thus, is an f-hypersystem, and hence P is an f-prime hyperideal. Example 19.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed from the set as in Example 5. Let be a hyperideal of . Then, Define for each , and consider the multiplicatively closed subsets Then: For , we have

Therefore is not an f-hypersystem then it is not an f-prime hyperideal.

Remark 2.

If on a Krasner hyperring R, for every , we define , then prime hyperideals are also f-prime hyperideals. However, when , f-prime hyperideals are not necessarily prime hyperideals.

Example 20.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed from the set as in Example 5. Take the hyperideal . Then, . For and the multiplicatively closed subset , we have:

For , and .

For , and .

For , and .

For , and .

Therefore, is an f-hypersystem and consequently I is an f-prime hyperideal. However, since but and , the hyperideal I is not a prime hyperideal. This is an example showing that f-prime hyperideals are not necessarily prime hyperideals.

Lemma 1.

Let be an f-hypersystem in R, and let K be a hyperideal of R that does not intersect S. Then there exists a maximal hyperideal J containing K among all hyperideals that are disjoint from S. Moreover, this hyperideal J is necessarily an f-prime hyperideal.

Proof. If , the proof is immediate. Hence, we may assume that . The existence of J follows from Zorn’s lemma. We now show that forms an f-hypersystem with core .

For any , the maximality of J implies that contains an element of S. Therefore, we can choose such that . Let and ; since , it follows that . Consequently, , which completes the proof. □

Theorem 3.

Let K be a hyperideal of R. Then K is contained in every maximal f-prime hyperideal belonging to it.

Proof. Let

J be a maximal

f-prime hyperideal belonging to

K. It suffices to show that

is

f-hyperrelated. We define the set

as:

Since

for every

and

, we obtain the set inclusion

. Consequently, for every

, there exist

and

such that

. Since

, and

K is assumed to be a hyperideal, we have

. As shown,

. Thus, we obtain the containment:

Therefore, for any

and

, we have

. This confirms that

satisfies the condition for being

f-hyperrelated. The proof is completed. □

Definition 9.

In a Krasner hyperring, the f-hyperradical of a hyperideal A of R is defined as the set of all elements such that every S, an f-hypersystem containing a, intersects A. In other words, Example 21.

Consider the Krasner hyperring constructed from the set as in Example 3. Let be a hyperideal and define . We aim to find the f-hyperradical of A.

For , take the multiplicatively closed subset . Then and since , S is an f-hypersystem. Because , for every f-hypersystem containing S and , we have , thus .

Also, and since , S is an f-hypersystem. Since , all f-hypersystems containing S and satisfy , so .

Consider with multiplicatively closed subset . For , and , and for , satisfies , hence S is an f-hypersystem. Since , we have .

Theorem 4.

The f-hyperradical of a hyperideal A is the intersection of all f-prime hyperideals containing A. Proof. If P is an f-prime hyperideal containing A, then we show that A is contained in P. Suppose that A is not contained in P. Then there exists an element such that . Since P is an f-hypersystem, it follows that . However, this contradicts the fact that A is contained in P. Therefore, lies in the intersection of all f-prime hyperideals containing A.

Conversely, suppose that a is an element of R but . Then there exists an f-hypersystem containing a and disjoint from A. By Lemma 1, there exists an f-prime hyperideal P containing A but disjoint from S. Hence, P does not contain a and so a is not in the intersection of all f-prime hyperideals containing A. □

Example 22.

For the f-hyperradical in Example 21, the only f-prime hyperideal containing the hyperideal A is A itself. Thus, is an f-prime hyperideal.

Theorem 5.

The f-hyperradical of a hyperideal is also a hyperideal.

Proof. Let be an f-hypersystem in R and let A be an ideal disjoint from S. By Zorn’s Lemma, there exists a maximal f-hypersystem containing and disjoint from A.

Consider the set Then, is an f-hypersystem with core and is disjoint from A. By Lemma 1, there exists an f-prime hyperideal P containing A and disjoint from . The set is an f-hypersystem with core , and the maximality of implies Therefore, by definition, we have □

Theorem 6.

Let R be a Krasner hyperring and let A and B be two distinct f-hyperideals of R. Then the following propositions hold.

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

Proof. - (i)

If

then there exists an

S such that

and

.

Assume that

and

. Then

. Since

S is an

f-hypersystem and

, it follows that

is impossible. Hence

.

Therefore .

- (ii)

Let . By definition, there exists an f-hypersystem S such that . Hence implies that for some and we have . Define . By our assumption is also an f-hypersystem. Moreover, so . Since we have and because it follows that . Similarly, by considering one obtains . Therefore with and , so . Thus, for every we have ; hence

- (iii)

Let . By definition, . Since and , and . It can be demonstrated that, in view of the definition of as and , it can be deduced that x is an element of . Hence .

- (iv)

Since , and , thus and By definition of ,

□

A notable point to emphasize in the forthcoming example is that, in Theorem 6, it cannot be guaranteed that the converses of conditions (ii), (iii), and (iv) are necessarily true.

Example 23.

Consider hypering R in Example 3 and . Let and hyperideals of R. Then .

Clearly, then .

Since then

If then

3.3. Left f-related Elements with a Hyperideal

In this section, the definition of f-hyperrelated elements, which establishes the relationship between an element of the hyperring and a hyperideal using f-hypersystems, will be given, and examples will be provided.

Definition 10.

Let R be a Krasner hyperring, A a hyperideal of R, and for each , let be a hyperideal in R. If for every there exists such that (respectively, ), then a is called a left (right) f-hyperrelated element to A.

Example 24.

For the Krasner hyperring constructed from the set as in Example 2, consider the prime hyperideal and thus . We define For , . Since for , and , it follows that is left f-hyperrelated to P.

For , . Since for , and , it follows that is left f-hyperrelated to P.

Example 25.

For the Krasner hyperring constructed from the set as in Example 3, consider the prime hyperideal . Then, . Define If and , then ; if or , then . Now, let us find the elements that are not left f-hyperrelated to the hyperideal P:

For : . Since , and or , but and , is not left f-hyperrelated to P.

For : . Since , and or , but and , is not left f-hyperrelated to P.

For : . Since , and or , but and , is not left f-hyperrelated to P.

For : . Since , and or , but and , is not left f-hyperrelated to P.

For : . Since , and or , but and , is not left f-hyperrelated to P.

Therefore, the elements , and are not left f-hyperrelated to the hyperideal P.

Definition 11.

Let A and B be hyperideals of R. If for every , b is left f-hyperrelated to A, then B is called a left f-hyperrelated hyperideal to A.

Example 26.

In Example 3, consider the Krasner hyperring constructed from the set . Let be a prime hyperideal. Then . Define If and , then .

If or , then .

When is defined as above, let us find the left f-hyperrelated and non-left f-hyperrelated hyperideals of R with respect to P:

For the hyperideal and , since , and and , and , it follows that I is left f-hyperrelated to P.

For the hyperideal , similarly, are left f-hyperrelated to P since and for , and . Thus, every is left f-hyperrelated to P, and therefore P is left f-hyperrelated hyperideal to itself.

For the hyperideal and , . For , or , but and , so is not left f-hyperrelated to P. Hence, is a hyperideal not left f-hyperrelated to P.

For the whole hyperring R and , . For , or , but again and , so is not left f-hyperrelated to P. Therefore, R is a hyperideal not left f-hyperrelated to P.

Proposition 1.

Let R be a commutative Krasner hyperring. Then the following conditions are equivalent.

- (i)

Every hyperideal K is f-hyperrelated to itself.

- (ii)

The zero hyperideal is f-hyperrelated to every hyperideal of R

Proof. Assume that 0 is f-hyperrelated to hyperideal K of R. Since , it follows that . For any , we may write with and . Because 0 is f-hyperrelated to K, we have , and hence . Thus, . For an arbitrary , we have , which implies that K is f-hyperrelated to itself.

Conversely, every hyperideal K is f-hyperrelated to itself. Since K is a hyperideal, . As K is f-hyperrelated to itself, it follows by definition that 0 is f-hyperrelated to K. □

Definition 12.

A maximal hyperideal in a class of hyperideals is said to be a maximal f-prime hyperideal if it is associated with a hyperideal J that is f-hyperrelated to it.

Proposition 2.

Let K be a hyperideal of R. Then the set S of all elements of R that are not f-hyperrelated to K forms an f-hypersystem.

Proof. For each , consider . For any , let . The set consisting of all such is closed under multiplication. Therefore, S together with its kernel constitutes an f-hypersystem. □

Theorem 7.

Let K be a hyperideal of R. Then every f-hyperrelated element to K and every f-hyperrelated hyperideal to K are contained in a maximal f-prime hyperideal belonging to K.

Proof. Clearly, an element k is f-hyperrelated to K if and only if is f-hyperrelated to K. Therefore, it suffices to prove the statement for an f-hyperrelated hyperideal.

Let L be f-hyperrelated hyperideal to K, and let S be the f-hypersystem consisting of all elements of R that are not f-hyperrelated to K. Then . Thus, by Lemma 1, L is contained in a maximal f-prime hyperideal belonging to K. □

Proposition 3.

Let K be a hyperideal of R. Then the f-hyperradical of K is f-hyperrelated to K.

Proof. Let S denote the set of all elements that are not f-hyperrelated to K. If contains an element that is not f-hyperrelated to K, then by the definition of the f-hyperradical, we must have . Hence, for any hyperideal K of R, the f-hyperradical is f-hyperrelated to K. □