1. Introduction

The present paper is devoted to the study of abstract evolution equations in modular function spaces of the type

. Our aim is to extend the theory of strongly continuous semigroups and their infinitesimal generators to the modular framework and, in particular, to establish modular analogues of the fundamental results of semigroup theory developed for Banach spaces by Engel and Nagel [

1] and Pazy [

2].

We consider the autonomous abstract Cauchy problem

where

denotes the (possibly unbounded) infinitesimal generator of a strongly continuous semigroup

acting on

. Equation (

1) is the modular counterpart of the classical linear evolution problem in Banach spaces; however, convergence, continuity, and differentiability are formulated here in the modular sense.

Working in modular spaces broadens the classical semigroup theory to a flexible analytical setting that can accommodate nonstandard growth and heterogeneous structures. The modular approach, developed systematically by Khamsi and Kozłowski [

3], is based on a convex regular modular

and the topology of modular convergence. Within this framework, Bachar [

4] established modular versions of key tools for linear evolution, including the construction of strongly continuous semigroups, the treatment of resolvents via Laplace-type representations, and operator bounds expressed through the growth function associated with

. These developments connect the classical semigroup theory of Engel–Nagel [

1] and Pazy [

2] with the nonlinear modular analysis of Khamsi–Kozłowski [

3].

In this paper, we investigate generation, continuity, and spectral properties of strongly continuous semigroups on . We identify conditions that ensure the existence of generators, derive modular resolvent representations together with explicit bounds, and justify the regularization of semigroup orbits in the modular topology. The results show that many structural features of the classical theory persist in once the norm topology is replaced by modular convergence. Under a standard -type assumption, the modular is equivalent to the associated Luxembourg norm, so the functional analysis result of the classical theory is preserved. Nevertheless, in this work, we formulate our a priori exponential bounds for the semigroup, the Laplace-type resolvent representations, and the generator domain characterizations primarily in modular form rather than in terms of the Luxembourg norm, since is the natural energy functional arising from the evolution problem and yields slightly sharper and more transparent quantitative estimates, which are particularly convenient from the numerical viewpoint. This effect is illustrated in Example 1, where a simple multiplication semigroup is used to demonstrate the potential difficulties that may occur in a purely Luxembourg norm-based numerical analysis. In this setting, the Luxembourg norm requires solving a nontrivial implicit equation, whereas the modular behavior is given explicitly and yields sharper and more transparent estimates.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 recalls the main concepts for

, including convex regular modulars,

-continuity, the

-type condition, and the associated growth function.

Section 3 develops the abstract evolution equation and semigroup framework in

: we formulate the notion of solution in the modular sense, construct strongly continuous semigroups from

-bounded generators via their exponential series, derive modular exponential bounds, and Laplace-type resolvent representations with explicit constants, and establish domain inclusion and generator identities using Steklov regularization.

2. Modular Spaces and Notation

We recall the fundamental notions of modular function spaces that form the analytical foundation of our work. The presentation follows the general framework of [

3], the formulation in [

4]. These concepts provide the functional setting for studying

-continuity, modular convergence, and the generation of semigroups in

.

Let

be a finite interval endowed with the Lebesgue

-algebra

, and denote by

the space of all extended real-valued measurable functions on

. A mapping

, as introduced in Definition 3.1 of [

3], is called a regular convex function pseudomodular if it is nontrivial, even, convex, monotone, orthogonally subadditive, and satisfies both the Fatou property and order continuity on the underlying lattice. If, in addition,

implies that

almost everywhere (

-a.e.), then

is called a regular convex function modular. We denote by

M the set of measurable functions that are finite

-a.e., identifying functions that coincide outside a

-null set.

Definition 1 (Convex regular modular [

3,

4])

. A mapping is called a convex regular modular

if, for all and ,- (i)

if and only if ρ-a.e.;

- (ii)

whenever ;

- (iii)

.

Given a convex regular modular

, the associated modular function space is defined by

The space

is equipped with the Luxembourg norm

and the topology of

-continuity is induced by the modular itself.

Throughout, we assume the

-type condition

which ensures the topological equivalence between

and

. In particular, the convexity estimate

holds. The corresponding growth function is given by

and remains finite for all

under assumption (

3). Moreover, the Fatou property yields the lower semicontinuity

We next recall the notions of -bounded operators and strongly continuous semigroups.

Definition 2 (

-bounded operator [

4])

. A linear operator is called -bounded

if there exists a constant such that The smallest such constant is referred to as the-bound

of B. Definition 3 (Strongly continuous semigroup [

3,

4])

. A family of operators on is called a strongly continuous semigroup

if the following conditions hold:- (i)

;

- (ii)

for all ;

- (iii)

for each , the function is continuous on .

If only conditions (i)–(ii) are satisfied,

is said to possess the algebraic semigroup property. The infinitesimal generator

B of

is defined by

Lemma 1 ([

3,

4])

. If is ρ-bounded with constant , then there exists such that The space , endowed with the topology of -continuity, serves as the functional setting for all subsequent developments. This framework will be used to construct strongly continuous semigroups, to analyze their spectral properties, and to derive resolvent estimates in the modular space .

3. The Abstract Evolution Equation and Semigroup Framework

Let

be a strongly continuous semigroup on

with infinitesimal generator

in the modular sense, as discussed in [

3,

4]. Throughout this section, we study the autonomous abstract Cauchy problem in the sense of

,

-a.e.,

Equation (7) provides the abstract framework for the analysis of linear evolution processes generated by the semigroup

on

. In this setting, the dynamics of the system are governed by the generator

B, and the semigroup

yields the modular representation

whenever

. Our aim is to establish conditions ensuring

-continuity, exponential boundedness, and modular resolvent representations for strongly continuous semigroups acting in the space

. The results presented in Theorems 1 and 2 constitute modular analogues of the classical results of Engel and Nagel [

1].

Definition 4. A ρ-continuous function is called a solution of the abstract evolution Equation (7) with initial value if the following conditions are satisfied:

- (i)

u is right-differentiable at in the modular sense, i.e., there exists such that - (ii)

for every there exists such that and the mapping is ρ-continuous on ;

- (iii)

for all ;

- (iv)

the evolution equation holds in the modular sense,

In order to illustrate the role of

-bounded operators in the theory of semigroups, we next show that such operators naturally give rise to strongly continuous semigroups via their exponential series representation. This construction provides the appropriate analogue of the classical bounded generator theorem from Banach-space semigroup theory as developed in [

1,

2], and it ensures that the essential features of the classical theory, such as strong continuity, the semigroup property, and the existence of an infinitesimal generator, carry over to the modular setting. The modular counterpart of this result was studied in detail in [

4], where it is shown that the boundedness condition on the operator suffices to guarantee the existence of a well-defined strongly continuous semigroup together with the corresponding convergence properties of its exponential series.

Lemma 2. Let ρ be a convex, regular modular satisfying the -type condition, and let be ρ-bounded with constant in the sense of Definition 2. For definewhere the series converges in the modular topology. Then is a strongly continuous semigroup on , , for all , and Proof. The proof follows the modular semigroup construction developed in [

4]. Since

satisfies the

-type condition, the growth function

is finite for all

, increasing, convex, and submultiplicative [

4]. We use the following convexity-scaling inequality: if

and

, then

which follows from convexity of

and the property

.

For

, set

and

. Applying (

9) to

gives

Since

B is

-bounded,

, and hence

The series defining

therefore converges in the modular topology, and inequality (

8) follows.

To verify the semigroup property, define the partial sums

For

, the algebraic Cauchy product gives

For each fixed

k,

as

, and

. Applying (

9) to

and using

gives

By dominated convergence in the modular sense, it follows that

and hence

for all

. Since

, the family

satisfies the algebraic semigroup property.

To show strong continuity at

, define

. From the definition of

,

Applying (

9) and using

yields

Hence

is continuous at

, and by the semigroup property, on all

.

Finally, for

we compute

Using the

-boundedness of

B gives

Thus,

in

for all

, and

B is the infinitesimal generator of the strongly continuous semigroup

. □

We now consider the integral (Laplace) representation of the resolvent under the growth hypothesis of Lemma 2. The corresponding -boundedness estimate for the resolvent depends on the modular growth function and on the -boundedness constant of the generator B. Let denote a threshold to be specified below. The precise bound is stated in the following Theorem; its magnitude is quantified in terms of and , and an explicit estimate is provided in Remark 2.

Theorem 1 (Laplace resolvent)

. Under the hypotheses and notation of Lemma 2, let and setIf , then for every the Laplace integralexists in and defines a linear ρ–bounded operator withwhere Proof. Fix

and

. For

set

where the integral is taken in the Bochner sense [

3]. Let

be a partition of

and define

By the Lebesgue dominated convergence theorem for Bochner integrals, we have

that is,

in the Luxembourg norm

; see [

3] for details. Moreover, since the modular

satisfies the

-type condition, norm convergence implies modular convergence, and hence

Normalize

so that

, and write

Using the growth function estimation

and the convexity of

, we obtain

By Lemma 2,

for all

. Consequently,

Moreover, since

, we have

If

, then

, and by the homogeneity of

we have

. Hence

If

, then

and

. The

-type condition implies that the growth function

is submultiplicative,

and monotone in

t. For

, write

with

and

, where

denotes the floor of

t, i.e., the greatest integer less than or equal to

t. Then

Combining the above inequalities, we obtain

Passing to the limit along the partition and using the Fatou property of

for Bochner integrals under the

-type condition (see [

3]), we obtain

To pass from

T to ∞, observe that for

the same estimate yields

Hence, the sequence

is Cauchy in the modular topology of

. Since

satisfies the

-type condition, it follows that

and thus

is also Cauchy in the Luxembourg norm. Therefore,

that is,

in the Luxembourg norm. By the

-type condition, this implies modular convergence as well, namely

By the lower semicontinuity of

and the preceding bound, we obtain

Consequently,

is

-bounded with bound

. Linearity follows directly from the linearity of the Bochner integral. □

It is often necessary to control the behavior of the resolvent as approaches the origin. In particular, for applications in spectral analysis, it is important to know that the prefactor remains bounded on compact subintervals of . This guarantees that the resolvent family does not lose its -boundedness when passing to small values of , so that only the constants in the estimates are affected, while the essential operator properties such as linearity, existence, and domain inclusion remain unchanged. The following remark makes this uniformity explicit.

Remark 1. Let . For all the constant is uniformly bounded byFor we simply have , so the bound is trivial. Hence the resolvent remains a ρ-bounded linear operator for every , where the threshold is chosen so that . Only the multiplicative constant in the bound depends on the growth function and on the range of λ. To use the resolvent bounds effectively later, it is convenient to give explicit estimates for under the -type condition and to indicate which growth constant yields the sharper bound.

Remark 2. Assume ρ satisfies the -type condition and, in Proposition 2

, take . Then, for , Next, we establish explicit bounds together with the smallest λ factor. Since the -type condition implies the finiteness and submultiplicativity of , see Lemma 3.1 in [3] and also [5,6], for , where stands for the ceiling function, i.e., . Consequently, valid whenever . Since and is submultiplicative, , hence the alternative bound When applying Lemma 1

, the resolvent estimate takes the form and, equivalently, if one prefers .

Which bound is sharper? Since , we have , hence for any fixed λ, Therefore, on the common admissible range , Thus, the bound with is uniformly sharper than the one with .

In particular, one may chooseso that for all . With this choice, the resolvent estimate holds with the sharper bound, namely Before the next result we regularize the semigroup orbit by the short-time Steklov average

This standard regularization places

in the generator’s domain

, legitimizes differentiation with respect to

t in the modular space

, and will be used to justify generator identities in

.

Theorem 2. Under the hypotheses and notation of Lemma 2, let and define by (

10)

for and . Then is ρ-continuous on , and for every , withMoreover, the mapping is ρ-continuous on every bounded interval, andFinally, for each fixed one haswhere Proof. Fix

and

. By the semigroup’s algebraic properties,

where

We first show that the integral in (

12) is well defined in

. For each

,

by Lemma 2, hence

. The growth estimate together with Lemma 1 yields, for

,

Thus, the map

is measurable and bounded on

. Since

satisfies the

-type condition,

is complete with respect to the Luxembourg norm

. Hence

is Bochner integrable in the Banach space

, and the integrals in (

12) and (

10) are well defined.

We show that

and

Using the algebraic properties

(i)–

(ii) of the semigroup given in Definition 3, we have

Hence,

To justify the next step, note that by the substitution

,

Using the identity

we obtain

Reparametrizing both integrals over

by

and

yields

Hence,

where

Since the semigroup

S is strongly continuous on

, we have

By the

-boundedness of the semigroup and Proposition 2, there exists

such that

where

. Hence, using (

4),

Fix

and let

be a partition with mesh

Set the weights

, so that

and

. Define

Since

is convex, we have

Moreover, using the pointwise bound above,

so

is uniformly bounded for refinements of the partition.

Since

is strongly continuous on

, the step functions

converge to

in

as

on

. Hence,

By the Fatou lower semicontinuity (

6),

Since

is continuous and bounded on

, the right-hand side equals

Therefore, we obtain the modular averaging inequality

Finally, since

as

and is bounded on

by

, we conclude that

Therefore

as

, i.e.,

in

; in particular,

pointwise on

. Let

. Using

we obtain

By the growth function bound of the modular,

since

as

. Hence,

This shows that

and that identity (

13) holds. We now prove that

is

-continuous on

. Since

and

is strongly continuous, we have, for any

,

which implies

Thus,

is

-continuous on

. We now verify (

11). From (

10),

For

, we compute

Let

. By the growth estimate for

and inequality (

4),

where

. Thus,

is integrable on every finite interval

.

Fix

and define

. Using (

4), one has

so

. By the scalar Lebesgue differentiation theorem,

Applying the convexity of

, we obtain

Hence, in the modular sense,

that is,

Therefore,

for a.e.

in

.

Finally, using convexity of

and

-continuity of

at

, we obtain

This completes the proof. □

Before stating the corollary, we recall the admissible range for

. Under the

-type condition and with

, Remark 2 shows that

is finite already for

(or, equivalently, for

, using

). Hence, the resolvent estimate from Lemma 1 remains valid on this enlarged half-line, with the small-

prefactor

given in Remark 2. In the proof below, however, we employ the Laplace representation

which requires

. Once the domain inclusion and resolvent identity have been established in this range, the explicit bounds for

allow us to extend the estimates to the full region

, which will be the framework for the subsequent spectral analysis in

.

Corollary 1. Under the hypotheses of Proposition 2, for every , the Laplace resolventis well defined in , belongs to , and satisfieswhereandMoreover, and on . Proof. The existence of

as a Bochner integral in

and the estimate (

14) follow directly from Lemma 1 with the same

and

. The prefactor

coincides with that obtained there and equals 1 for

.

We now derive an integral identity for

that will be useful later. Fix

and recall the Steklov regularization (

10),

By Theorem 2,

for every

,

is

-continuous on

, and

while

On any finite interval

, the mapping

belongs to

(equivalently,

), using the

-type condition on

to compare the modular and the Luxembourg norm and to guarantee Bochner integrability of

in

. Hence, the modular fundamental theorem of calculus (Bochner integration by parts) applies to

on

and yields

Using

a.e., we obtain

Letting

and using the modular dominated convergence theorem (which applies because

is

-bounded and satisfies the growth estimate (

8)), we pass to the limit in each term and obtain

As

, the boundary term at

T satisfies

since

, and the boundary term at 0 equals

. Hence

We now prove that

and that the resolvent identity holds. Set

For

, using the semigroup property and a change in variables, we obtain

Hence

Dividing by

h gives

We show that the right-hand side converges in (in the modular sense) to as .

First, note that

Moreover, by the definition of

u and the growth estimate (

8), the family

converges in

to

u as

, and

-bounded for small

by dominated convergence in the modular sense. Hence

For the second term in (

16), set

In the proof of Theorem 2, we established the modular averaging inequality

Since

as

and

is integrably bounded on

, the same argument with the weights

yields

Thus

Combining these two limits in (

16), we obtain

By the definition of the infinitesimal generator in the modular sense, this shows that

and

Since

, we have proved that

and that

on

, which completes the proof. □

We now illustrate the abstract framework with a simple but very flexible class of examples, namely multiplication semigroups associated with integral modulars. Starting from a general convex modular

of integral type, we obtain a natural

-bounded semigroup

and can then specialize to the Orlicz–Luxembourg setting. This will also allow us to compare, in a concrete situation, the simplicity of modular estimates with the implicit character of the Luxembourg norm. Let

be a

-finite measure space and let

be a convex function modular on

of the form

where for a.e.

the function

is increasing on

. Consider a bounded measurable function

and, for

, define

Then, using only the monotonicity of

and the fact that

, we obtain for each

Hence

is

-bounded with bound 1. If, in addition, the modular

satisfies the

-type condition (

3), then the associated growth function

is finite for all

, the standing assumptions of this paper are fulfilled, and we can regard

as a strongly continuous semigroup in the sense of Definition 3. In this case, all the results developed in this section (exponential bounds, resolvent representation, domain characterization) apply directly to this family. The proof uses only the explicit modular

and no norm structure.

A particularly important example of this abstract construction is provided by the classical Orlicz setting. Let

be convex and increasing, satisfy

, and fulfill a

-type condition, and set

Then

is the corresponding Orlicz space with Luxembourg norm

and modular convergence is equivalent to convergence in

. In particular, the inequality

implies that

is also bounded with respect to the Luxembourg norm, but this information is encoded only indirectly through the implicit infimum in the definition of

. Indeed, if we fix

and

, then

If

, then by definition

Since

and

is increasing, we obtain

Hence, for every

we have

Since

and

is increasing,

so every

is also admissible for

. Therefore

In other words,

This computation shows that, even in this very simple multiplication setting, establishing boundedness in the Luxembourg norm already requires working with the implicit infimum in the norm definition and exploiting the special structure of

, whereas the corresponding modular estimate follows in a single step from the explicit integral form of

together with the monotonicity of

. In the next example, we illustrate this difficulty by a numerical simulation of the Luxembourg norm for a multiplication semigroup, highlighting the role of modular estimates.

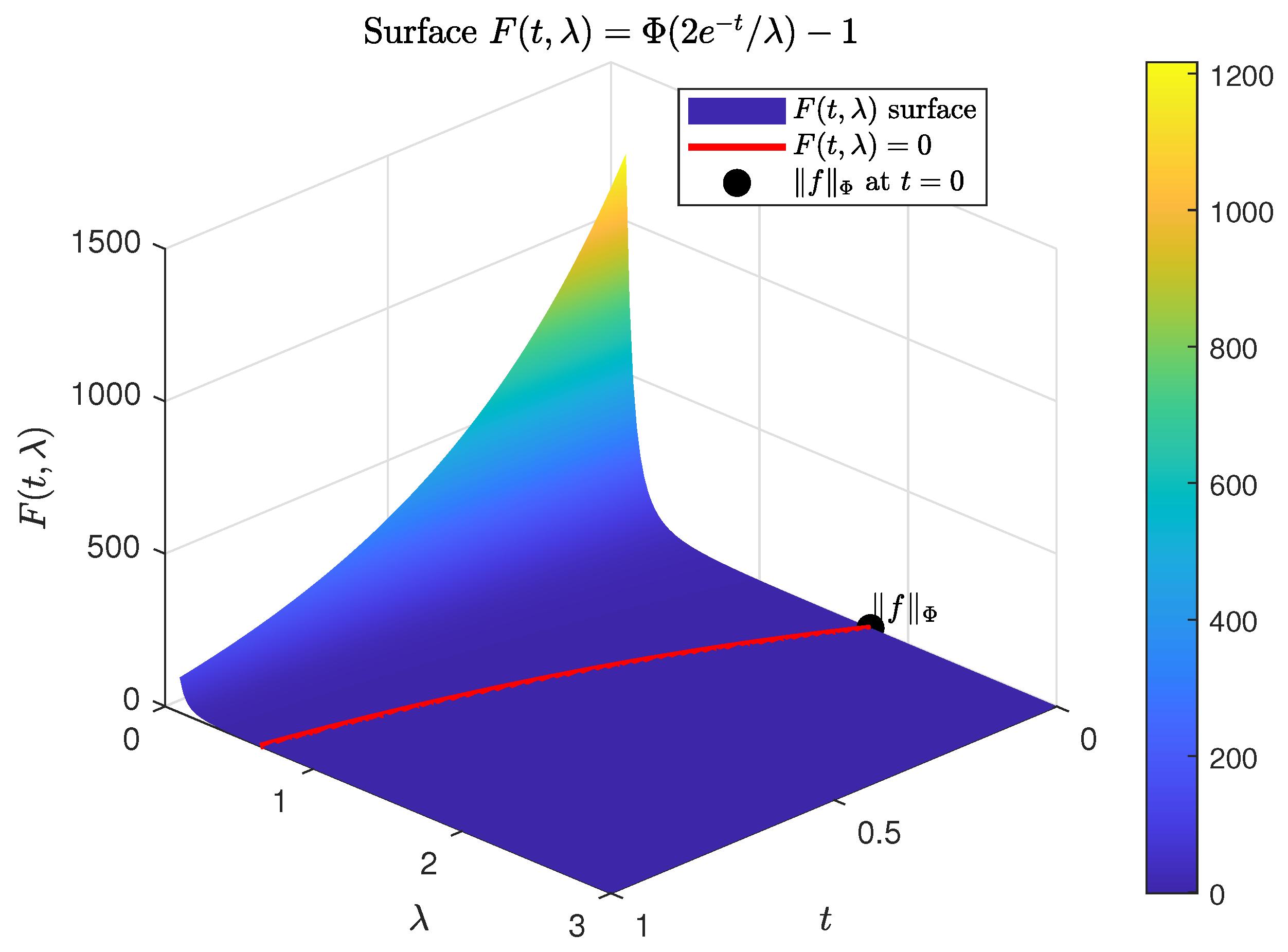

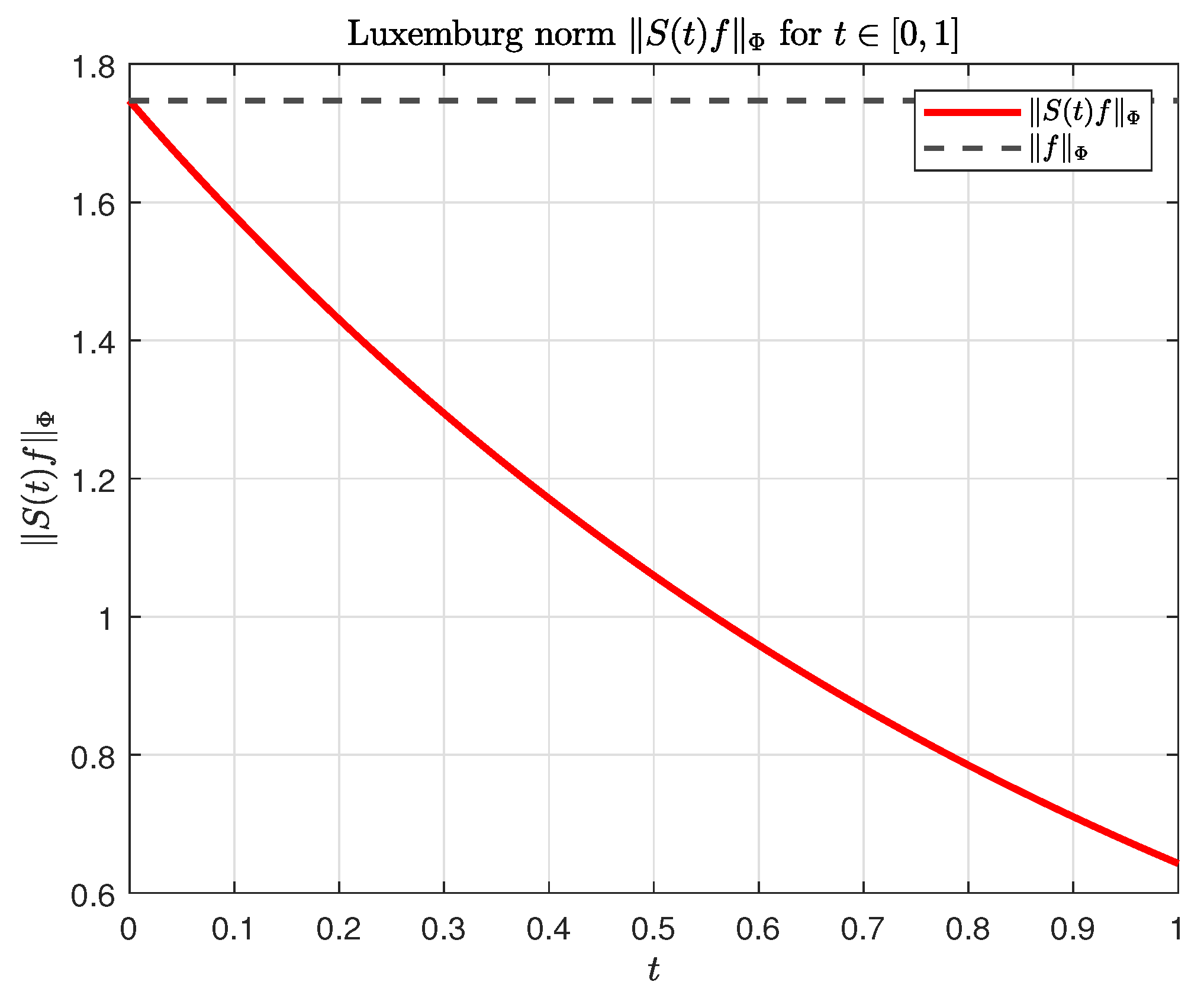

Example 1. To illustrate this difference numerically, let with Lebesgue measure and considerThen , Φ

is increasing and convex on , and one easily checks thatso Φ

satisfies a -type condition. The associated modular isand the Luxembourg norm is Take the constant function on and the multiplication semigroup with , so thatFor this choice,and for every ,Thus, the ρ-boundedness of is obtained immediately from the modular estimate. In contrast, the Luxembourg norm of f is determined by the implicit equationthat is,This nonlinear equation has no closed-form solution and must be solved numerically to obtain . Likewise, for each fixed the norm is given implicitly byThus, even for this very simple constant function and a bounded multiplication semigroup, the Luxembourg norm leads to transcendental equations, whereas the corresponding modular estimates are immediate. This concrete example explains why, in practice, semigroup bounds are more naturally derived at the modular level, even in -type condition settings where the Luxembourg norm is available. To visualize this implicit dependence. Figure 1 shows the surfacetogether with the zero level set corresponding to . Figure 2 displays the graph of on and the horizontal line . Both plots underline that obtaining the Luxembourg norm requires solving a nontrivial implicit equation, while the modular behavior is given explicitly.