1. Introduction

This article focuses exclusively on finite, undirected simple graphs. Let G denote a graph containing n vertices; its adjacency matrix is defined as , where if vertices i and j are adjacent, and in all other cases. It is obvious that constitutes a real symmetric matrix with entries being either 0 or 1, and every one of its eigenvalues belongs to the set of real numbers. Such eigenvalues of are termed the eigenvalues of graph G, and the set of G’s n eigenvalues is designated as its spectrum. The count of non-zero eigenvalues in the spectrum is called the rank of G (denoted ), whereas the count of zero eigenvalues is referred to as the nullity (denoted ), and it satisfies

In the field of chemistry, conjugated hydrocarbon molecules can be represented by graphs referred to as molecular graphs. The nullity (and its complementary rank) of these molecular graphs possesses substantial practical value for chemical applications [

1]. For instance, a graph with nullity 0 constitutes a necessary prerequisite for the molecule to display stable chemical characteristics [

2]. As early as 1957, Collatz and Sinogowitz [

3] put forward the idea of characterizing graphs via nullity exceeding 0. It is a widely recognized truth that a graph is singular if 0 is among its eigenvalues, namely,

. Therefore, the problem raised by Collatz and Sinogowitz is equivalent to describing all singular graphs, which remains an extremely demanding undertaking. The authors of [

4,

5,

6,

7] have respectively determined the nullity sets of trees, unicyclic graphs, bicyclic graphs, and tricyclic graphs. To address this problem, a great number of researchers have investigated the relationship between a graph’s nullity and its structure, utilizing the structural characteristics of singular graphs. The graphs with

n vertices and nullity

or

have been characterized in [

8,

9]. Additionally, Ref. [

10] proved that the nullity of a tree’s line graph is at most 1. More research works have explored the bounds (upper and lower) for nullity (rank) of graphs. The authors of [

11] derived the upper and lower bounds of nullity using the matching number and cyclomatic number. The authors of [

12] reformulated the upper and lower bounds of nullity

by leveraging the

-invariant (omega invariant) and inherent vertex degrees of graph

G. The authors of [

13] provided bounds for the rank of a graph based on its matching number, number of even cycles, and maximum number of disjoint odd cycles. The authors of [

14] extended the framework of [

13] to mixed graphs and partially characterized the corresponding extremal graphs. The authors of [

15] established an upper bound for nullity based on the elementary cyclic number and number of leaves of a graph. The authors of [

16,

17] characterized the extremal graphs that attain the upper bound of nullity proposed in [

15]. The authors of [

18] presented an upper bound for nullity using the number of vertices and the girth of the graph, and characterized the extremal graphs achieving this bound. The authors of [

19] characterized the minimal graphs with nullity equal to

, where

n and

d denote the number of vertices and diameter of the graph, respectively. The authors of [

20] characterized the minimal graphs with nullity equal to

.

Singular graphs admit multiple equivalent definitions. For instance, a graph

G is singular if and only if the kernel space of

is non-trivial, or equivalently, if the homogeneous linear system

(where

serves as the coefficient matrix) admits a non-trivial solution. From this perspective, Ref. [

21] established necessary and sufficient conditions for a graph to be singular, with the characterization rooted in the notion of admissible induced subgraphs. Specifically, a graph is singular if and only if there exists a non-trivial vector

such that when weights are assigned to the vertices of

G via

X, every vertex

satisfies the following condition:

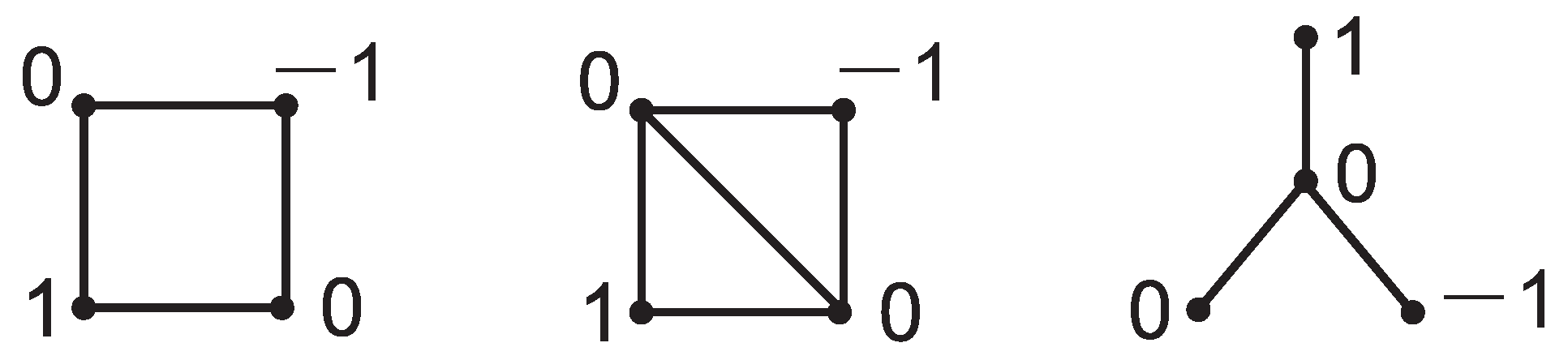

Figure 1 shows the vertex weight assignments that satisfy Equation (

1) for the 4-vertex graphs

,

, and

; this implies that these three graphs are singular.

Meanwhile, the authors of [

22] proved that coprime graphs are singular and derived a lower bound for their nullity. The authors of [

23] investigated the singularity of graphs where each block is a clique. The authors of [

24] studied the nullity and singularity of cycle-spliced graphs. [

21] offered methods to construct singular graphs from smaller ones and presented some sufficient conditions for singularity. Characterization of singular line graphs associated with trees was presented in [

25], whereas the exploration of singular graphs within fullerenes was conducted in [

26]. Researchers in [

27] delineated the properties of singular Cayley graphs over cyclic groups and established that vertex-transitive graphs of prime order exhibit non-singular characteristics. An alternative definition posits that a graph

G is singular provided that its adjacency matrix

is singular—i.e., the determinant of

is zero. From this standpoint, necessary and sufficient conditions governing the singularity of multiple families of tricyclic graphs were deduced in [

28,

29,

30,

31], together with the likelihood of singular graphs occurring in these families. Contemporary studies have additionally uncovered connections between singular graphs and other branches of mathematics, such as the representation theory of finite groups, combinatorial mathematics, and algebraic geometry (for relevant references, see [

27,

32,

33,

34,

35]).

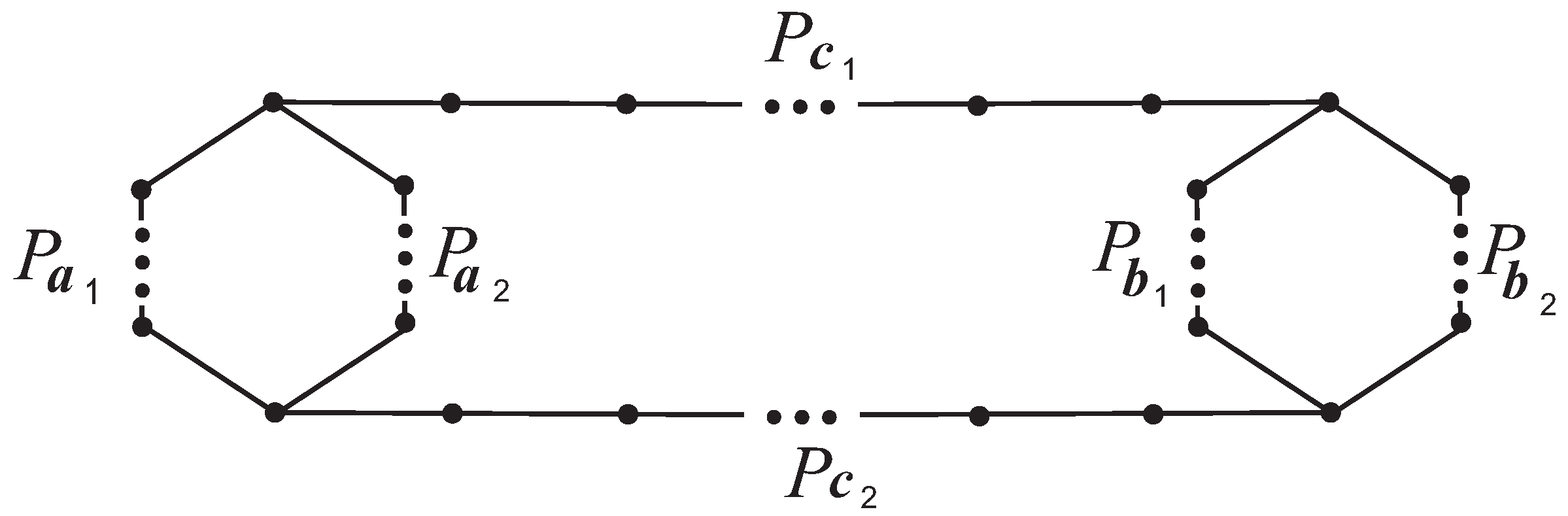

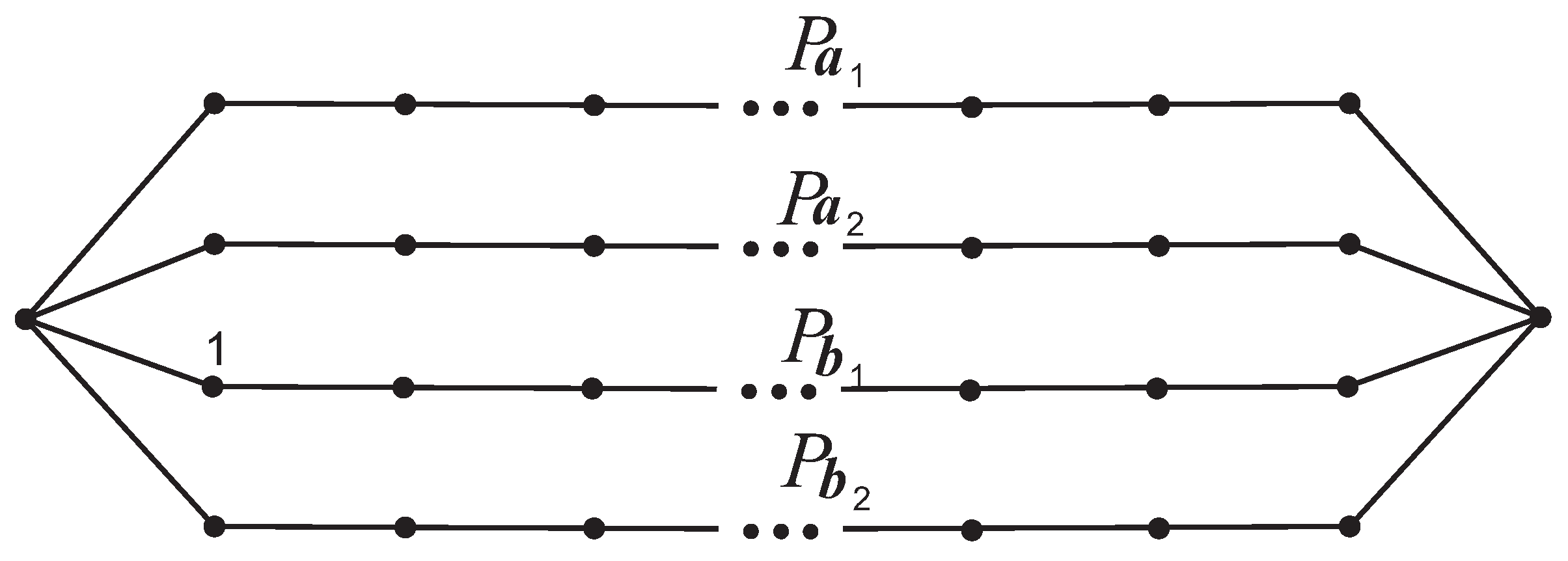

Let

,

, and

stand for the complete graph, the path, and the cycle that contain

n vertices, respectively. The graph formed by the following operations is denoted as

(see

Figure 2), abbreviated as the

-graph: Identify the start vertex of path

and the start vertices of paths

and

simultaneously; identify the end vertex of path

and the start vertices of paths

and

simultaneously; identify the start vertex of path

and the end vertices of paths

and

simultaneously; identify the end vertex of path

and the end vertices of paths

and

simultaneously.

For the sake of convenience, a path comprising an even number of vertices is termed an even path, while one with an odd number of vertices is designated an odd path. Paths labeled

are referred to as vertical paths, while paths labeled

are called horizontal paths. A cycle formed by two vertical paths is named the 2-cycle; there are two the 2-cycles in

Figure 2. A cycle bounded by two vertical paths and two horizontal paths is termed a quadrilateral; there are four quadrilaterals in

Figure 2. Let

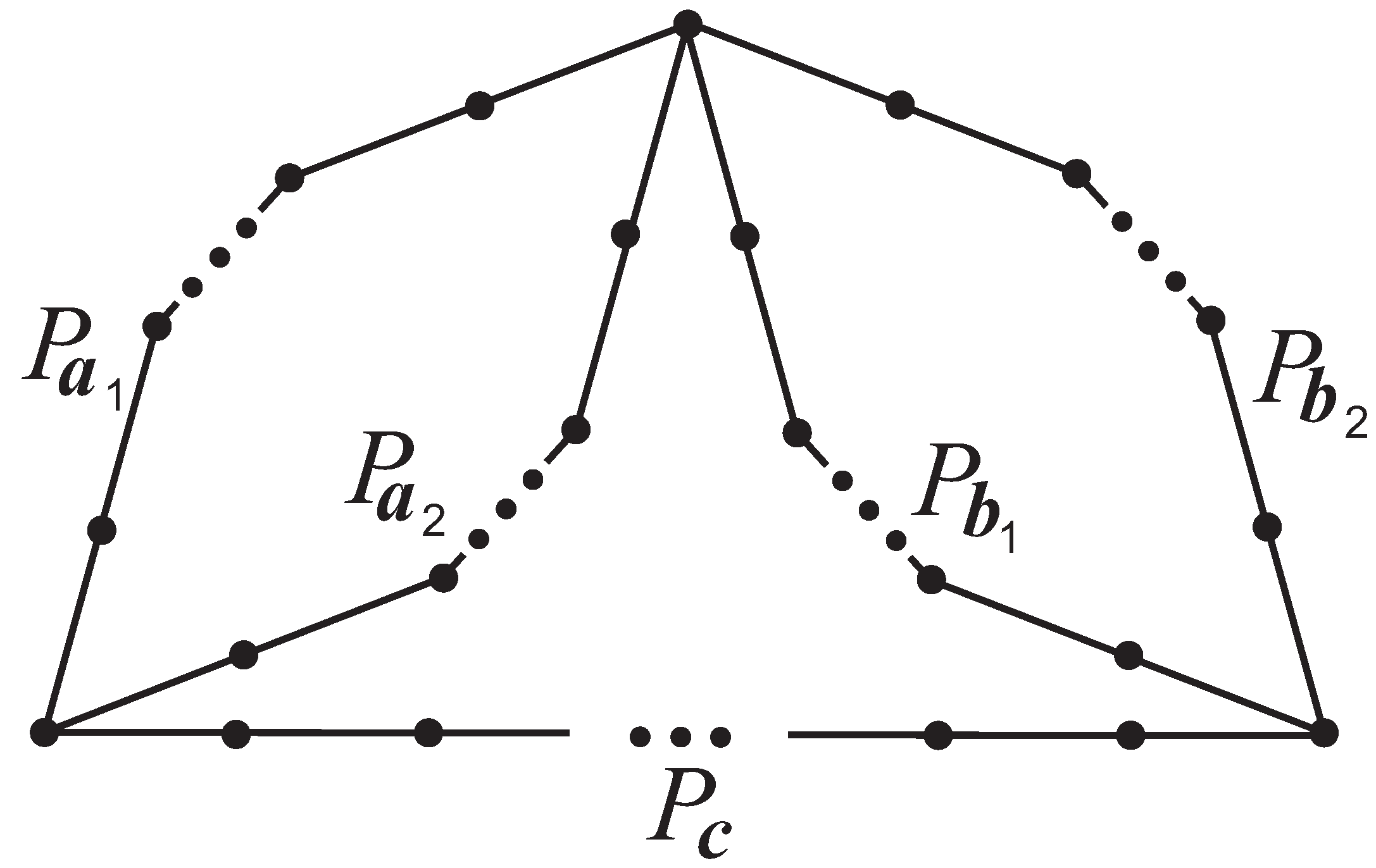

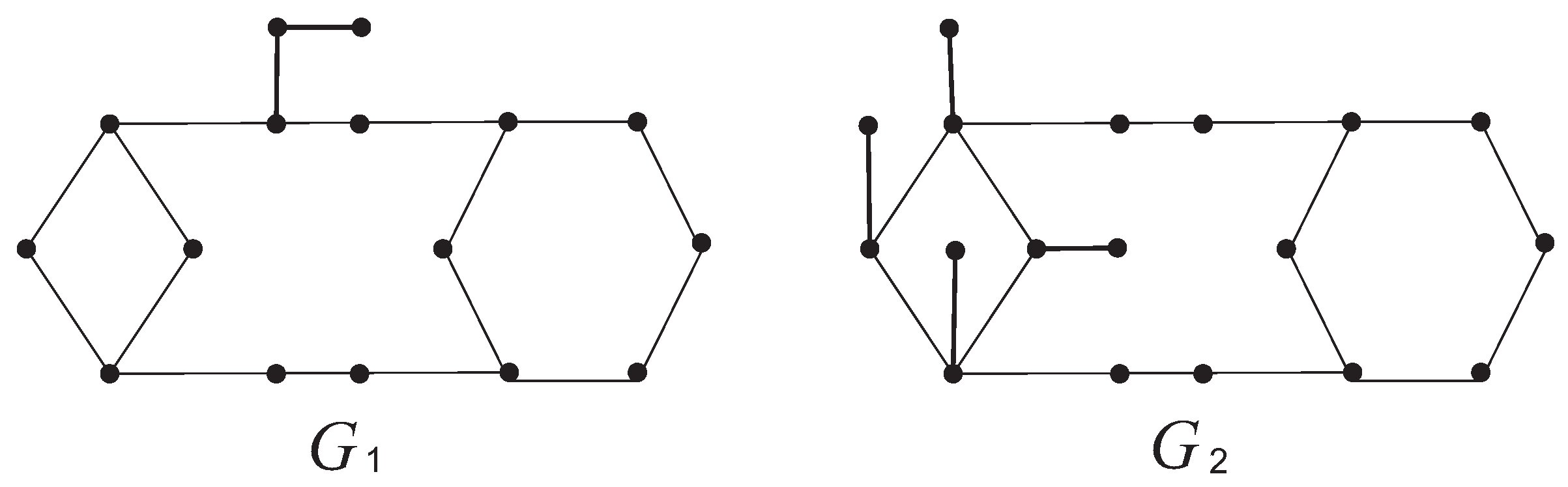

(see

Figure 3), abbreviated as the

-graph. In the graph

, the cycle formed by three paths is called a triangle; there are 4 triangles in

Figure 3. Let

(see

Figure 4), abbreviated as the

-graph. In this paper, the necessary and sufficient conditions for the singularity of the

graph,

graph and

graph are presented. It is also proved that the probabilities of a randomly selected graph from the above three types being a singular graph are

, and

respectively.

Let

represent the disjoint union of two graphs

G and

H. A vertex with a degree of 1 is termed a pendant vertex, and the vertex adjacent to a pendant vertex is designated a quasi-pendant vertex. Any unexplained notations and terminology in the text can be found in [

1].

This article is structured as follows:

Section 1 introduces basic concepts, basic graph classes, the paper’s research problems, its application background, and its research significance.

Section 2 presents several basic lemmas required for proving the main results.

Section 3 derives the necessary and sufficient conditions for the graphs to be singular.

Section 4 gives the probability that these graphs are singular.

2. Lemmas

In this section, we state several lemmas for proving the main conclusions. Additionally, we give an example to demonstrate the basic concepts and the application of the lemmas.

Lemma 1 ([

1])

. Let , here is the connected component of graph G, then . Equivalently, G is not singular if and only if each is not singular. Lemma 2 ([

1])

. Let G be a graph with a pendant vertex, and let H stand for the vertex-induced subgraph of G derived by removing the pendant vertex along with its adjacent vertex. Then . Equivalently, graph G is singular precisely when graph H is singular. A subgraph of G whose components are either (paths of length 1) or cycles is referred to as an elementary subgraph of G. An elementary subgraph of G that encompasses all vertices of G is termed an elementary spanning subgraph, alternatively known as a Sachs subgraph of G. A Sachs subgraph of G composed solely of isolated edges is designated as a perfect matching of G. Naturally, the number of vertices in a graph possessing a perfect matching must be even. A Sachs subgraph is a spanning subgraph of G; that is, it includes all vertices of G, with each connected component being either an isolated edge or a cycle. Some graphs have Sachs subgraphs, while others do not (e.g., a path graph with an odd number of vertices has no Sachs subgraph). The Sachs subgraph is a core concept of this paper. As shown in Lemma 3 below, the determinant of the adjacency matrix of a graph can be calculated using the Sachs subgraphs of the graph.

Lemma 3 ([

1])

. Let G be a graph of order n, with its adjacency matrix denoted as , then the determinant of satisfies the following equation:where denotes the collection of all Sachs subgraphs associated with graph G, signifies the count of connected components in graph H, and denotes the number of cycles contained within graph H. We present the following example to illustrate the structure of Sachs subgraphs in a graph and demonstrate how to apply Lemma 3 to determine the singularity of a given graph.

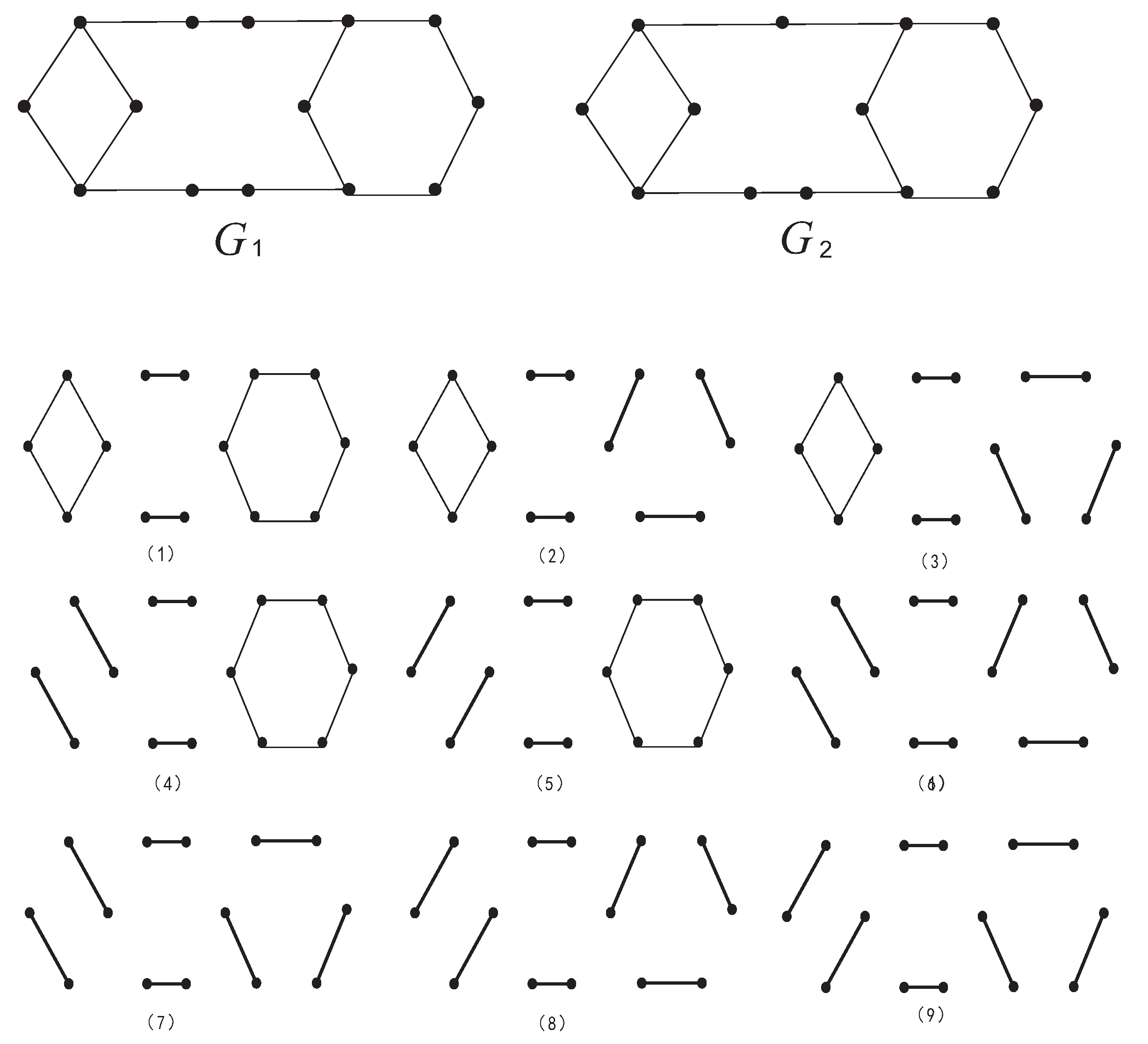

Example 1. As depicted in Figure 5, a single Sachs subgraph with two cycles exists in graph , specifically (see Figure 5(1)); two Sachs subgraphs of containing the cycle exist, namely (see Figure 5(2,3)); similarly, two Sachs subgraphs of incorporating the cycle exist, namely (see Figure 5(4,5)); additionally, has four perfect matchings (see Figure 5(6–9)). By Lemma 3,

Thus,

is a singular graph.

Graph has no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles (e.g., ). It also has no Sachs subgraphs with a single cycle (either or ): when (or ) is removed from , the number of remaining vertices is odd, and a perfect matching cannot be formed with an odd number of vertices. Additionally, has no acyclic Sachs subgraphs (i.e., perfect matchings), as itself has an odd number of vertices. Therefore, is also a singular graph.

Figure 5.

The structure of the Sachs subgraphs of graphs , (1) is a Sachs subgraph of graph containing two cycles; (2–5) are Sachs subgraphs of with one cycle; (6–9) are perfect matchings of .

Figure 5.

The structure of the Sachs subgraphs of graphs , (1) is a Sachs subgraph of graph containing two cycles; (2–5) are Sachs subgraphs of with one cycle; (6–9) are perfect matchings of .

3. Singularity

In the present section, we shall investigate the necessary and sufficient conditions for

graphs,

graphs and

graphs to be singular graphs. To present the main theorem, we first give the following lemmas. Let

and

;

and

denote the subsets of all odd numbers in

X and

Y respectively. When

, the set

contains exactly two odd numbers and two even numbers, if the two odd numbers exactly form a 2-cycle (see

Figure 2), we say there exists an odd 2-cycle; otherwise, we say there is no odd 2-cycle.

Lemma 4. Under the following conditions, the graph (see Figure 1) is non-singular. (1) (2) (3) and there is no odd 2-cycle, Proof. - (1)

In this case, there is 1 Sachs subgraph of G that contains two cycles: ; There are 8 Sachs subgraphs of G that contain one cycle (two), (two), (one), (one), (one),

(one); There are 5 Sachs subgraphs of

G that do not contain cycles (i.e., perfect matchings). By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

this cannot hold; otherwise, 4 would divide 5, which is a contradiction. Thus, graph

G is non-singular.

- (2)

We may assume without loss of generality that are all even numbers, while is an odd number.

- (i)

Without loss of generality, we can assume that

is an even number and

is an odd number. In this case, there are no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles in graph

G; There are 3 Sachs subgraphs of

G that contain one cycle

(one),

(one),

(one); There are 3 perfect matchings. By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

this cannot hold; otherwise, 2 would divide 3, which is a contradiction. Thus, graph

G is non-singular.

- (ii)

In this case, there are no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles in graph

G; There are 3 Sachs subgraphs of

G that contain one cycle

(one),

(one),

(one); There is no perfect matching in graph

G. By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

since three 2-unit weights are placed on both sides of the balance, the two sides will always be unbalanced; thus, the above equation does not hold. Therefore,

G is non-singular.

- (3)

We may assume without loss of generality that

are all even numbers, while

are all odd numbers. In this case, there are no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles in graph

G; There are 3 Sachs subgraphs of

G that contain one cycle

(one),

(one),

(one); There is no perfect matching in graph

G. By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

Similarly, this is impossible, so graph

G is non-singular.

□

Lemma 5. Under the following conditions, the graph (see Figure 1) is singular. (1) (2) (3) and there exists an odd 2-cycle, Proof. It can be readily confirmed that no Sachs subgraphs exist in graph G under such circumstances, and as deduced from Lemma 3, G is singular. □

Lemma 6. If then graph is singular precisely when the lengths of the two 2-cycles are both multiples of 4, or the lengths of the four quadrilaterals are all multiples of 4.

Proof. In this case, there are no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles in graph

G; There are 6 Sachs subgraphs of

G that contain one cycle:

(one),

(one),

(one),

(one),

(one),

(one); There are 4 perfect matchings. By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

when and only when

There are only the following four cases for the relationships among : (mod 4), (mod 4); (mod 4), (mod 4); (mod 4), (mod 4); (mod 4), (mod 4).

If

(mod 4) and

(mod 4)—i.e.,

and

, it can be readily verified that Equation (

2) holds under such circumstances.

If

(mod 4) and

(mod 4), or

(mod 4) and

(mod 4), it can be readily verified that Equation (

2) does not hold under such circumstances.

If

(mod 4),

(mod 4), it can be further divided into the following two subcases: (

iii(1))

(mod 4). Then Equation (

2) becomes:

Equation (

3) holds precisely when

(mod 4). So, Equation (

2) holds precisely when

(mod 4),

(

iii(2))

(mod 4). Then Equation (

2) becomes:

Equation (

4) holds precisely when

(mod 4). So, Equation (

2) holds precisely when

(mod 4),

, and this is equivalent to the lengths of the four quadrilaterals being all multiples of 4.

From (i)–(iii), Equation (

2) holds if and only if the lengths of the two 2-cycles are all multiples of 4 or the lengths of the four quadrilaterals are all multiples of 4. □

Remark 1. When , Equation (2) holds precisely when (mod 4), (mod 4) or (mod 4), precisely when the integers congruent to 0 modulo 4 and those congruent to 2 modulo 4 each account for half of the set . Lemma 7. If and there exists an odd 2-cycle, then graph is singular precisely when the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4.

Proof. Without loss of generality, we can assume that

and

are both even integers, whereas

, and

are all odd integers. In this case, there are no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles in graph

G; There is 1 Sachs subgraph of

G that contain one cycle

; There are 2 perfect matchings. By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

precisely when

. □

Lemma 8. If and there is no odd 2-cycle, then graph is singular precisely when the length of the quadrilateral formed by the four even paths is a multiple of 4, and the lengths of the two 2-cycles are congruent modulo 4.

Proof. Without loss of generality, we can assume that are all even numbers, while are all odd numbers. In this case, there is 1 Sachs subgraph containing two cycles in graph G: ; There is 1 Sachs subgraph of G that contain one cycle ; There are 2 perfect matchings.

By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

Multiply each side of the equation by

, when and only when

when and only when

(mod 4) and

(mod 4), it is noted that both

and

are odd; therefore, the above equation holds when and only when

(mod 4) and

(mod 4). □

Lemma 9. If and there is no odd 2-cycle, then graph is singular precisely when the length of the quadrilateral formed by the four odd paths is a multiple of 4.

Proof. Without loss of generality, we can assume that are all even numbers, while are all odd numbers. In this case, there are no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles in graph G; There is 1 Sachs subgraph of G that contain one cycle: ; There are 2 perfect matchings.

By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

when and only when

□

Lemma 10. Except for the cases of Lemmas 4–9, graph is singular precisely when the length of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4.

Proof. . Based on the parity of

and the symmetry exhibited by the graph

, 18 cases are identified, all of which are presented in

Table 1 below. In

Table 1,

e stands for an even corresponding parameter,

o for an odd one, and ∗ for a case already resolved in prior lemmas.

Cases (1), (5), (6) and (11) in

Table 1 have been addressed in Lemma 4; Cases (8), (15), (17) and (18) have been addressed in Lemma 5; Case (3) has been addressed in Lemma 6; Case (9) has been addressed in Lemma 7; Case (10) has been addressed in Lemma 8; Case (12) has been addressed in Lemma 9. The unaddressed cases will be verified below in the order of the table.

Case (2) In this case, there are no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles in graph G; There are 4 Sachs subgraphs of G that contain one cycle: (one), (one), (one), (one); There is no perfect matching in graph G.

By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

if and only if

if and only if

when and only when

or

.

Case (4) In this case, there is 1 Sachs subgraph containing two cycles in graph G: ; There are 4 Sachs subgraphs of G that contain one cycle: (two), (one), (one); There is no perfect matching in graph G.

By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

if and only if

when and only when

.

Case (7) In this case, there is 1 Sachs subgraph containing two cycles in graph G: ; There are 4 Sachs subgraphs of G that contain one cycle: (two), (two); There are 4 perfect matchings in graph G.

By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

Multiply each side of the equation by

, if and only if

if and only if

if and only if

or

.

Case (13) In this case, there is 1 Sachs subgraph containing two cycles in graph G: ; There are 2 Sachs subgraphs of G that contain one cycle: ; There is no perfect matching in graph G.

By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

if and only if

.

Case (14) In this case, there are no Sachs subgraphs containing two cycles in graph G; There is 1 Sachs subgraph of G that contain one cycle: ; There are 2 perfect matchings in graph G.

By Lemma 3, The graph

G is singular precisely when

if and only if

.

Case (16) In this case, there is 1 Sachs subgraph containing two cycles in graph G: ; There are 4 Sachs subgraphs of G that contain one cycle: (two), (two); There are 4 perfect matchings in graph G.

Similar to Case (7), G is singular when and only when or . □

Remark 2. Lemma7 cannot be merged into Lemma 10. This is because, under the conditions of Lemma 7, the length of the 2-cycle formed by two even paths may also be a multiple of 4, but it has no connection with the singularity of this graph.

By summarizing Lemmas 4–10, we obtain the following theorem.

Theorem 1. Let set and set ; and denote the subsets of all odd numbers in X and Y, respectively. Then the graph is singular precisely when one of the following conditions is satisfied.

- (a)

and one of the following subconditions must hold: (i) and the length of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4; (ii) and either the lengths of the two 2-cycles are both multiples of 4, or the lengths of the four quadrilaterals are all multiples of 4.

- (b)

and the length of the even 2-cycle is a multiple of 4.

- (c)

and one of the following two categories of subconditions must hold: (i) There exists an odd 2-cycle in graph G, and one of the following subconditions must hold: (1) and the length of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4; (2) (3) and the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4. (ii) There is no odd 2-cycle in graph G, and one of the following subconditions must hold: (1) the length of the quadrilateral formed by the four even paths is a multiple of 4, and the lengths of the two 2-cycles are congruent modulo 4; (2) and the length of the quadrilateral formed by the four odd paths is a multiple of 4.

- (d)

and one of the following subconditions must hold: (i) and the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4; (ii)

- (e)

and one of the following subconditions must hold: (i) and the length of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4; (ii)

Since

(see

Figure 3), we can easily derive the following corollary from Theorem 1.

Corollary 1. Let set ; denote the subsets of all odd numbers in X. Then the graph is singular precisely when one of the following conditions is satisfied.

- (a)

and one of the following subconditions must hold: (i) c is an even number, and the length of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4; (ii) c is an odd number, and either the lengths of the two 2-cycles are both multiples of 4, or the lengths of the four triangles are all multiples of 4.

- (b)

and one of the following two categories of subconditions must hold: (i) There exists an odd 2-cycle in graph G, and one of the following subconditions must hold: (1) c is an even number; (2) c is an odd number and the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4. (ii) There is no odd 2-cycle in graph G, c is an odd number and the length of the triangle formed by the three odd paths is a multiple of 4.

- (c)

and one of the following subconditions must hold: (i) c is an even number and the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4; (ii) c is an odd number.

- (d)

Since

(see

Figure 4), we can easily derive the following corollary from Corollary 1 and Remark 1.

Corollary 2. Let set ; denote the subsets of all odd numbers in X. Then the graph is singular precisely when one of the following conditions is satisfied.

- (a)

and the integers congruent to 0 modulo 4 and those congruent to 2 modulo 4 each account for half of the set .

- (b)

and the length of the 2-cycle formed by the two odd paths is a multiple of 4.

- (c)

4. Probability

In this section, we will study the probability of singular graphs occurring among graphs, graphs and graphs. In the sample space consisting of all graphs ( or ), since the parameters have infinitely many possible values, is an infinite sample space. Within this sample space, the determinant of the adjacency matrix of each graph is a random variable defined on . Our primary focus is on the probability that this random variable equals 0, i.e., the probability of singular graphs occurring among all graphs ( or ). Let A and B be two random events. Let stand for the probability of event A taking place, and for the conditional probability of A occurring on the condition that B has already occurred, respectively. To prove the main conclusion, we first present two lemmas.

Lemma 11. Let be all even numbers, be all odd numbers(see Figure 2). Then the probability that either the lengths of the two 2-cycles are all multiples of 4 or the side lengths of the four quadrilaterals are all multiples of 4 is . Proof. By Lemma 6, that the lengths of the two 2-cycles are all multiples of 4 or the side lengths of the four quadrilaterals are all multiples of 4 is equivalent to one of the following conditions (1), (2), or (3) holds: (mod 4), (mod 4); (mod 4), (mod 4); (mod 4), (mod 4). Since (1), (2), and (3) are mutually exclusive, and their respective probabilities of holding are , and , the probability that (1), (2), or (3) holds is thus (since ). □

Lemma 12. When randomly partitioning a 4-tuple consisting of two even numbers and two odd numbers into two pairs, the probability that each pair has identical parity is .

Proof. Without loss of generality, let the 4-tuple be . Consider the pairs formed by combining 1 with another element: there are exactly three cases, namely , and . Among these three cases, only the pair has the same parity. □

Theorem 2. The probabilities that the random are singular graphs are equal to and respectively.

Proof. For convenience, we use , , and to denote the events that -graphs, -graphs and -graphs are singular graphs, respectively.

Case 1. For .

By the formula of total probability

As is well known,

follows a binomial distribution

, where the parameters are

and

. So

By Theorem 1,

Subcase (a).

(i) The probability that

is

, and the probability that the length of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is

(ii) The probability that

is

, and the probability that either the lengths of the two 2-cycles are all multiples of 4 or the side lengths of the four quadrilaterals are all multiples of 4 is

(by Lemma 11). So,

Subcase (b).

The probability that

is

, and the probability that the length of the even 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is

So,

Subcase (c). (i) The probability that there exists an odd 2-cycle in graph G is (by Lemma 12). (1) The probability that is , and the probability that the length of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is (2) The probability that is (3) The probability that is , and the probability that the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is

(ii) The probability that there is no odd 2-cycle in graph

G is

(by Lemma 12). (1) The probability that

is

, the probability that the length of the quadrilateral formed by the four even paths is a multiple of 4 is

, and the probability that the lengths of the two 2-cycles are congruent modulo 4 is

. (2) The probability that

is

, and the probability that the length of the quadrilateral formed by the four odd paths is a multiple of 4 is

. So,

Subcase (d).

(i) The probability that

is

, and the probability that the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is

. (ii) The probability that

is

. So,

Subcase (e).

(i) The probability that

is

, and the probability that the lengths of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is

. (ii) The probability that

is

. So,

Case 2. For

(See

Figure 2). By Corollary 1,

Subcase (a).

(i) The probability that

c is an even number is

, and the probability that the length of at least one 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is

(ii) The probability that

c is an odd number is

, and the probability that either the lengths of the two 2-cycles are all multiples of 4 or the side lengths of the four triangles are all multiples of 4 is

. So,

Subcase (b). (i) The probability that there exists an odd 2-cycle in graph G is (1) The probability that c is an even number is (2) The probability that c is an odd number is , and the probability that the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is

(ii) The probability that there is no odd 2-cycle in graph

G is

the probability that

c is an odd number is

, and the probability that the length of the triangle formed by the three odd paths is a multiple of 4 is

. So,

Subcase (c).

(i) The probability that

c is an even number is

, and the probability that the length of the odd 2-cycle is a multiple of 4 is

. (ii) The probability that

c is an odd number is

. So,

Case 3. For

(see

Figure 3). By Corollary 2,

Subcase (a). In the set consisting of four even numbers, the probability that half of the integers are congruent to 0 modulo 4 and the other half are congruent to 2 modulo 4 is .

Subcase (b). the probability that the length of the 2-cycle formed by the two odd paths is a multiple of 4 is

Then, by the formula of total probability,

□