Abstract

We construct a bound set that does not admit a Riesz spectrum containing a nonempty periodic set for which the period is a rational multiple of a fixed constant. As a consequence, we obtain a bounded set V with an arbitrarily small Lebesgue measure such that for any positive integer N, the set of exponentials with frequencies in any union of cosets of cannot be a frame for the space of square integrable functions over V. These results are based on the proof technique of Olevskii and Ulanovskii from 2008.

MSC:

42C15

1. Introduction and Main Results

One of the fundamental research topics in Fourier analysis is the theory of exponential bases and frames. The elementary fact that forms an orthogonal basis for has far-reaching implications in many areas of mathematics and engineering. For instance, the celebrated Whittaker–Shannon–Kotel’nikov sampling theorem is an important consequence of this fact (see e.g., [1]).

As a natural generalization of the functions in , one considers the set of exponentials :: , where is a discrete set consisting of the pure frequency components of exponentials (thus called the frequency set or spectrum), in the Hilbert space for a finite positive measure set . That is, for each , the map restricted to the set S is considered as a function in . Characterizing the properties of in the space , such as whether forms an orthogonal/Riesz basis or a frame, has been an important problem in nonharmonic Fourier analysis. The problem has a close connection to the theory of entire functions of the exponential type in complex analysis through the celebrated work of Paley and Wiener [2]. For more details on this connection and for some historical background, we refer the reader to the excellent book by Young [3]. Below, we give a short overview of some known results on exponential bases and frames.

1.1. An Overview of Existing Work on Exponential Bases and Frames

Exponential orthogonal bases: For the case of orthogonal bases, Fuglede [4] posed a famous conjecture (also called the spectral set conjecture) that states that if is a finite positive measure set, then there is an exponential orthogonal basis (with ) for if and only if the set S tiles by translations along a discrete set in the sense that

where for and is 0 otherwise. The conjecture turned out to be false for but is still open for . Nevertheless, there are many special cases for which the conjecture is known to be true. For instance, the conjecture is true when is a lattice of —in which case the set can be chosen to be the dual lattice of [4]—and also when is a convex set of finite positive measure for all [5]. In particular, it was shown in [6] that there is no exponential orthogonal basis for when S is the unit ball of for , in contrast to the case , where the unit ball is simply , and is an orthogonal basis for . For more details on Fuglede’s conjecture and its recent progress, we refer the reader to [5] and the references therein.

Exponential Riesz bases: The relaxed case of Riesz bases is yet more challenging. Certainly, relaxing the condition of orthogonal bases to Riesz bases allows for potentially much more feasible sets . However, there are only several classes of sets that are known to admit a Riesz spectrum, meaning that there exists an exponential Riesz basis for . For instance, the class of convex symmetric polygons in [7], the class of sets that are finite unions of intervals in [8,9], and the class of certain symmetric convex polytopes in for all [10]. Moreover, the existence of exponential Riesz bases for disjoint intervals with hierarchical structure was proved in [11], and exponential Riesz bases with restricted supports were treated in [12]. Recently, Kozma, Nitzan, and Olevskii [13] constructed a bounded measurable set such that no set of exponentials can be a Riesz basis for .

In search of an analogue to Fuglede’s conjecture for Riesz bases, Grepstad and Lev [14] considered the sets that satisfy for some discrete set and some

Such a set is called a k-tile with respect to ; in particular, the set S satisfying (1) is a 1-tile with respect to . It was shown in [14] that if is a bounded k-tile set with respect to a lattice and has measure zero boundary, then the set S admits a Riesz spectrum , which is obtained using quasicrystals [15,16]. Later, Kolountzakis [17] removed the measure zero boundary condition of S and showed that can be chosen to be a union of k translations of (referred to as a -structured spectrum), where : is the dual lattice of with . The converse of this statement was proved by Agora et al. [18], thus establishing the equivalence: given a lattice , a bounded set is a k-tile with respect to if and only if it admits a -structured Riesz spectrum. They also showed that the boundedness of S is essential by constructing an unbounded 2-tile set with respect to that does not admit a -structured Riesz spectrum. Nevertheless, for unbounded multi-tiles with respect to a lattice , Cabrelli and Carbajal [19] were able to provide a sufficient condition for S to admit a structured Riesz spectrum. Recently, Cabrelli et al. [20] found a necessary and sufficient condition for a multi-tile of finite positive measure to admit a structured Riesz spectrum, which is given in terms of the Bohr compactification of the tiling lattice .

Exponential frames: Since frames allow for redundancy, it is relatively easier to obtain exponential frames than exponential Riesz bases. For instance, the set of exponentials is an orthonormal basis for and is thus a frame for with frame bounds whenever S is a measurable subset of .

Nitzan et al. [21] proved that if is a finite positive measure set, then there exists an exponential frame (with ) for with frame bounds and , where are absolute constants. The proof is based on a lemma from Marcus et al. [22] that resolved the famous Kadison–Singer problem in the affirmative.

Universality: In [23,24], Olevskii and Ulanovskii considered the interesting question of universality. They discovered some frequency sets that have universal properties: namely, the so-called universal uniqueness/sampling/interpolation sets for Paley–Wiener spaces with all sets in a certain class. In our notation, this corresponds to the set of exponentials being a complete sequence/frame/Riesz sequence in for all sets in a certain class. For the convenience of the readers, we include a short exposition on the relevant notions in Paley–Wiener spaces in Appendix A.

It has been shown that universal complete sets of exponentials exist: for instance, the system with is complete in for every measurable set with . Furthermore, any set with satisfying for all is complete in whenever is a bounded measurable set with .

On the other hand, the existence of universal exponential frames and universal exponential Riesz sequences depends on the topological properties of S. As a positive result, it has been shown that there is a perturbation of such that is a frame for whenever is a compact set with ; a different construction of such a set was given by Matei and Meyer [15,16] based on the theory of quasicrystals. Similarly, there is a perturbation of such that is a Riesz sequence in whenever is an open set with . However, on the negative side, it has been shown that given any and a separated set with , there is a measurable set with such that is not a frame for , indicating that the compactness of S in the aforementioned result cannot be dropped. Similarly, it has been shown that given any and a separated set with , there is a measurable set with such that is not a Riesz sequence in , similarly indicating that the restriction to open sets cannot be dropped.

For more details on the universality results, we refer the reader to Lectures 6 and 7 in the excellent lecture book by Olevskii and Ulanovskii [25].

1.2. Contribution of the Paper

This paper is motivated by the following problem.

Problem 1.

Is there a bounded/unbounded set that does not admit a Riesz spectrum, meaning that for every , the set of exponentials is not a Riesz basis for ?

This problem was recently solved by Kozma, Nitzan, and Olevskii [13]. They constructed a bounded measurable set such that no set of exponentials can be a Riesz basis for .

In this paper, we take a different approach to construct a bounded subset of that does not admit a certain general type of Riesz spectrum. Through this, we offer diverse methods for constructing sets that do not admit Riesz spectra. In particular, our approach enables the design of specific spectra that we aim to exclude. To achieve this, we adapt the proof technique of Olevskii and Ulanovskii [24], which also works in higher dimensions (see Section 1 in [24]); thus, our results also extend to higher dimensions. However, for simplicity of presentation, we will only consider the dimension-one case ().

Before presenting our results, note that for any bounded set , there exist some parameters and such that . It is therefore enough to restrict our attention to sets (see Lemma 1 below). Also, recall that a set is said to admit a Riesz spectrum if the system is a Riesz basis for .

Our first main result is as follows.

Theorem 1.

Let and . There exists a measurable set with satisfying the following property: if contains arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions with a fixed common difference belonging in , then is not a Riesz sequence in . Moreover, such a set can be constructed explicitly as

It should be noted that the set is an open set containing . This set has a small Lebesgue measure due to the exponentially decreasing length of the intervals. It is worth comparing the set V with a fat Cantor set that is a closed, nowhere dense subset of with positive measure (see e.g., [26,27]), where a set is called nowhere dense if its closure has an empty interior. In contrast to the fat Cantor sets, the set V has a nonempty interior and is dense in because it contains .

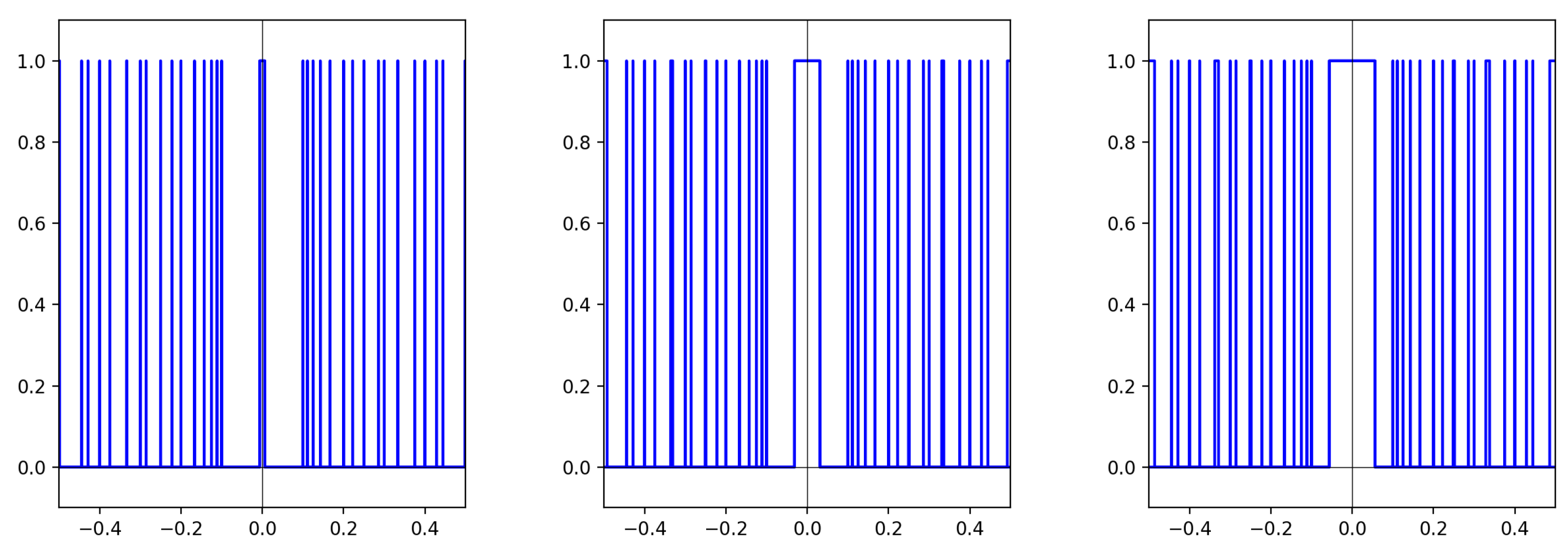

To illustrate the dense set , we truncate the infinite union in its expression to the finite union over . The corresponding sets for and are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The characteristic function of the corresponding truncated set for and (from left to right).

To help the understanding of the readers, we provide two sets : one which meets and the other which does not meet the condition stated in Theorem 1.

Example 1.

- (a)

- Let be an increasing sequence in , and let . Define the sequence by and for . Clearly, we have for all . Consider the setwhere for any set . This set contains arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions with common difference P and has lower and upper Beurling densities given by and , respectively (see Section 2.3 for the definition of the Beurling density).

- (b)

- Let and let be a sequence of distinct irrational numbers between 0 and 1. Consider the setthat has a uniform Beurling density . For each , the set Λ contains exactly one arithmetic progression with a common difference in the positive domain : namely, the arithmetic progression , , of length k. Due to the ± mirror symmetry, the set Λ has another such arithmetic progression in the negative domain . Note that all of these arithmetic progressions have integer-valued common differences and are distanced by some distinct irrational numbers, so none of them can be connected with another to form a longer arithmetic progression. Hence, there is no number for which the set Λ contains arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions with common difference P. Such a set is not covered by the class of frequency sets considered in Theorem 1.

Our second main result is the following.

Theorem 2.

Let , and let be a family of separated sets with for all . One can construct a measurable set with such that is not a Riesz sequence in for all .

Let us present some interesting implications of our main results.

By convention, a discrete set with is called periodic with period (or t-periodic) if there is a number such that for all . Note that if is a nonempty periodic set with period , where are coprime numbers, then it must contain a translated copy of : that is, for some . As a result, we have the following corollary of Theorem 1.

Corollary 1.

For any and , let be the set given by (2). Then for any nonempty periodic set with its period belonging in , the system is not a Riesz sequence in . Consequently, the set S does not admit a Riesz spectrum containing a nonempty periodic set with its period belonging in .

It is worth noting that the class of nonempty periodic sets with a rational period is uncountable because of the flexibility in the placement of elements in each period; hence, Corollary 1 cannot be deduced from Theorem 2.

As mentioned in Section 1.1, Agora et al. [18] constructed an unbounded 2-tile set with respect to that does not admit a Riesz spectrum of the form with . By a dilation, one could easily generalize this example to an unbounded 2-tile set with respect to for any fixed that does not admit a Riesz spectrum of the form with . Note that such a form of Riesz spectrum is -periodic and thus not admitted by our set S given by (2) for any . In fact, our set S has a much stronger property than W: namely, that S does not admit a periodic Riesz spectrum with its period belonging in , and moreover, the set S is bounded.

Since the set S is contained in , it is particularly interesting to consider the frequency sets consisting of integers . Noting that a periodic subset of is necessarily N-periodic for some , we immediately deduce the following result from Corollary 1.

Corollary 2.

Let be the set given by (2) with and any . Then for any nonempty periodic set , the system is not a Riesz sequence in .

Alternatively, one could construct such a set from Theorem 2 by observing that the family of all nonempty periodic integer sets is countable; indeed, the one and only nonempty 1-periodic integer set is , the nonempty 2-periodic integer sets are , , , and so on.

Further, it is easy to deduce the following result from Corollary 2 and Proposition 2 below by setting and .

Corollary 3.

Let be the set given by (2) with and any , and let . Then for any proper periodic subset , the system is not a frame for .

The significance of Corollary 3 is in the fact that for any and any proper subset , the set of exponentials is not a frame for even though the set V has a very small Lebesgue measure . Note that is a frame for with frame bounds since it is an orthonormal basis for .

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Sequences in Separable Hilbert Spaces

Definition 1.

A sequence in a separable Hilbert space is called

- a Bessel sequence in (with a Bessel bound B) if there is a constant such that

- a frame for (with frame bounds A and B) if there are constants such that

- a Riesz sequence in (with Riesz bounds A and B) if there are constants such that

- a Riesz basis for (with Riesz bounds A and B) if it is a complete Riesz sequence in (with Riesz bounds A and B);

- an orthogonal basis for if it is a complete sequence of nonzero elements in such that whenever ;

- an orthonormal basis for if it is complete and whenever .

The associated bounds A and B are said to be optimal if they are the tightest constants satisfying the respective inequality.

In general, an orthonormal basis is a Riesz basis with Riesz bounds , but an orthogonal basis is not necessarily norm-bounded below and thus is generally not a Riesz basis (for instance, consider the sequence , where is an orthonormal basis for ). Nevertheless, exponential functions have a constant norm in for any finite measure set : namely, for all . Thus, an exponential orthogonal basis is simply an exponential orthonormal basis scaled by a constant.

Proposition 1.

Let be a separable Hilbert space.

- (a)

- Corollary 3.7.2 in [28]: Every subfamily of a Riesz basis is a Riesz sequence with the same bounds (the optimal bounds may be tighter).

- (b)

- Corollary 8.24 in [29]: If is a Bessel sequence in with Bessel bound B, then for all . If is a Riesz sequence in with bounds , then for all .

- (c)

- Lemma 3.6.9, Theorems 3.6.6, 5.4.1 and 7.1.1 in [28] (or see Theorems 7.13, 8.27 and 8.32 in [29]): Let be an orthonormal basis for and let . The following are equivalent.

- is a Riesz basis for ;

- is an exact frame (i.e., a frame that ceases to be a frame whenever a single element is removed) for ;

- is an unconditional basis of with ;

- There is a bijective bounded operator such that for all .

Moreover, in this case, the optimal frame bounds coincide with the optimal Riesz bounds.

Proposition 2

(Proposition 5.4 in [30]). Let be an orthonormal basis of a separable Hilbert space , where I is a countable index set. Let be the orthogonal projection from onto a closed subspace . Let and . The following are equivalent.

- is a frame for with lower bound α;

- is a Bessel sequence with bound ;

- is a Riesz sequence with lower bound α.

2.2. Exponential Systems

As already introduced in Section 1, we define the exponential system : for a discrete set (called a frequency set or a spectrum).

Lemma 1.

Assume that is a Riesz basis for with bounds , where is a discrete set and is a measurable set.

- (a)

- For any , the system is a Riesz basis for with bounds A and B.

- (b)

- For any , the system is a Riesz basis for with bounds A and B.

- (c)

- For any , the system is a Riesz basis for with bounds A and B; equivalently, is a Riesz basis for with bounds and .

A proof of Lemma 1 is given in Appendix B.

Remark 1.

Lemma 1 remains valid if the term “Riesz basis” is replaced with one of the following: “Riesz sequence”, “frame”, or “frame sequence” (and also “Bessel sequence”, in which case the lower bound is simply neglected).

Theorem 3

(The Paley–Wiener stability theorem [2]). Let be a bounded set of positive measure and be a sequence of real numbers such that is a Riesz basis for (respectively, a frame for , a Riesz sequence in ). There exists a constant such that whenever satisfies

the set of exponentials is a Riesz basis for (respectively, a frame for , a Riesz sequence in ).

For a proof of Theorem 3, we refer the reader to p. 160 in [3] for the case where V is a single interval and Section 2.3 in [8] for the general case. It is worth noting that the constant depends on the Riesz bounds of the Riesz basis for , which are determined once and V are given. Also, it is pointed out in Section 2.3, Remark 2 in [8] that the theorem also holds for frames and Riesz sequences.

2.3. Density of Frequency Sets

The lower and upper (Beurling) densities of a discrete set are defined respectively by (see e.g., [31])

If , we say that has a uniform (Beurling) density . A discrete set is called separated (or uniformly discrete) if its separation constant is positive. For a separated set , we will always label its elements in increasing order: that is, with for all .

The following proposition is considered folklore. The corresponding statements for Gabor systems of are well-known (see Theorem 1.1 in [32] and also Lemma 2.2 in [33]), and the following proposition can be proved similarly.

Proposition 3.

Let be a discrete set, and let be a finite positive measure set that is not necessarily bounded.

- (i)

- If is a Bessel sequence in , then .

- (ii)

- If is a Riesz sequence in , then Λ is separated, i.e., .

A proof of Proposition 3 is given in Appendix B.

Theorem 4

([34,35]). Let be a discrete set, and let be a finite positive measure set.

- (i)

- If is a frame for , then .

- (ii)

- If is a Riesz sequence in , then Λ is separated and .

Corollary 4.

Let be a discrete set, and let be a finite positive measure set. If is a Riesz basis for , then Λ is separated and has a uniform Beurling density .

3. A Result of Olevskii and Ulanovskii

As our main results (Theorems 1 and 2) hinge on the proof technique of Olevskii and Ulanovskii [24], we will briefly review the relevant result from [24].

Theorem 5

(Theorem 4 in [24]). Let , and let be a separated set with . One can construct a measurable set with such that is not a Riesz sequence in .

The proof of Theorem 5 relies on a technical lemma (Lemma 2 below) that is based on the celebrated Szemerédi’s theorem [36] asserting that any integer set with a positive upper Beurling density contains at least one arithmetic progression of length M for all . Here, an arithmetic progression of length M means a sequence of the form

As a side remark, we mention that the common difference of the arithmetic progression resulting from Szemerédi’s theorem can be restricted to a fairly sparse subset of positive integers . For instance, one can ensure that P is a multiple of any prescribed number by passing to a subset of that is contained in for some and has a positive upper Beurling density. This allows us to take , which clearly satisfies . Further, one can even choose for any , which satisfies

More generally, one may choose for any polynomial p with rational coefficients such that and for (see [37] p. 733). On the other hand, it was shown by (Theorem 7 in [38]) that cannot be a lacunary sequence, i.e., a sequence satisfying (for instance, ). Note that the aforementioned set can be sparse but not lacunary since for any polynomial p. We refer to Section 2 in [39] for a short review of the possible choice of (deterministic) sets and also for the situation for which is chosen randomly.

Lemma 2

(Lemma 5.1 in [24]). Let be a separated set with . For any and , there exist constants , and an increasing sequence in Λ such that

Moreover, the constant can be chosen to be a multiple of any prescribed number .

As Lemma 2 will be used in the proof of Theorem 2, we include a short proof of Lemma 2 in Appendix B for self-contained nature of the paper.

4. Proof of Theorem 1

Before proving Theorem 1, we note that Theorem 2 is an extension of Theorem 5 from a single set to a countable family of sets . We first consider a particular choice of sets , , for any fixed , from which a desired set for Theorem 1 will be acquired.

Proposition 4.

Let and , , ; that is, for . Given any , one can construct a measurable set with such that is not a Riesz sequence in for all .

Proof.

Fix any and choose an integer so that . We claim that for each there exists a set with satisfying the following property: for each , there is a finitely supported sequence satisfying

If this claim is proved, one could take and . Indeed, we have so that . Also, it holds for any that

By fixing any and letting , we conclude that is not a Riesz sequence in .

To prove claim (4), fix any . For each , let be the sequence given by

which is the Fourier coefficient of the 1-periodic function

that is, for almost every . Note that . Choose a number satisfying

so that

Now, the set comes into play. We write with

For , we define

and observe that

Setting for , we obtain

Note from (6) that , which implies . Indeed, the set is of length , and the dilated set restricted to has a Lebesgue measure as well, so the set with has a Lebesgue measure of at most , which is strictly less than . Finally, define , which clearly satisfies . Then for each ,

which establishes claim (4). This completes the proof. □

Remark 2

(The construction of S for , , ). In the proof above, the set S is constructed as follows. Given any , choose an integer so that . The set is then given by with , where

In short,

where the set V satisfies , and thus . Note that the two sets S given in (2) and (11) are identical up to a countable set. Since a measure zero set is negligible in integration, these sets can be used interchangeably.

We are now ready to prove Theorem 1.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Let be a set containing arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions with a fixed common difference for some . To prove that is not a Riesz sequence in , it suffices to show that the set given by (10) for and (with a fixed integer ) satisfies the following property: there is a finitely supported sequence with

Indeed, since (see Remark 2), it then holds for any that

which implies that is not a Riesz sequence in .

To prove claim (12), consider the sequence , the function , and the number taken, respectively, from (5)–(7) with . By the assumption, the set contains an arithmetic progression of length with common difference , which can be expressed as

for some . Similarly to (8) and (9), we define

and observe that

Recalling that (see Remark 2), we have

where the inequality (7) for is used in the last step. Since , we have

which establishes claim (12). □

5. Proof of Theorem 2

We will now prove Theorem 2, which generalizes Proposition 4 from , , to arbitrary separated sets with positive upper Beurling densities. The proof is similar to the proof of Proposition 4, but since an arbitrary separated set is in general non-periodic, we need the additional step of extracting an approximate arithmetic progression from each set with the help of Lemma 2.

Proof of Theorem 2.

Fix any and choose an integer so that . We claim that for each , there exists a set with satisfying the following property: for each , there is a finitely supported sequence with

To prove claim (13), fix any . For each , let be an -sequence with unit -norm such that

Since the sequence is not finitely supported, there is a number with . Note that since for all , we have

so that

We then choose a small parameter satisfying

so that . Note that all the terms up to this point depend only on the parameters and ℓ: in fact, only on the value .

Now, the set comes into play. Applying Lemma 2 to the set with the parameters M and chosen above, we deduce that there exist constants and and an increasing sequence in satisfying

For , we define

and observe that

Setting , we have

Similarly to the proof of Proposition 4, we have , and therefore, the set satisfies . It then holds for each that

which proves claim (13).

Finally, based on the established claim (13), we define and . Clearly, we have so that . Also, it holds for any that

By fixing any and letting , we conclude that is not a Riesz sequence in . □

Remark 3

(The construction of S for arbitrary separated sets ). In the proof above, the set S for arbitrary separated sets is constructed as follows. Given any , choose an integer so that . The set is then given by with , where

Here, is a positive integer that depends on the value and the set . In short,

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we constructed a bounded subset of that does not admit a certain general type of Riesz spectrum. Specifically, we constructed a set that does not admit a Riesz spectrum containing a nonempty periodic set with its period belonging in for any fixed constant , where denotes the set of all positive rational numbers. In particular, this led to a set with an arbitrarily small Lebesgue measure such that for any and any proper subset I of , the set of exponentials with is not a frame for . The obtained results have immediate consequences in sampling theory and frame theory and have potential applicability in practical problems such as OFDM (orthogonal frequency division multiplexing) based communications that involve the design of exponential bases.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00275360).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Related Notions in Paley–Wiener Spaces

The Fourier transform is defined densely on by

This is a nonstandard but equivalent definition of the Fourier transform that has no negative sign in the exponent; this definition is employed only to justify relation (A1). Alternatively, as in [23,24] one could use the standard definition of the Fourier transform, which has negative sign in the exponent, and define the Paley–Wiener space to be the image of under the Fourier transform. It is easily seen that is a unitary operator satisfying , where is the reflection operator defined by , and thus, . The Paley–Wiener space over a measurable set is defined by

equipped with the norm , where is embedded into by the trivial extension. Denoting the Fourier transform of by , we see that for almost all ,

Moreover, if the set has a finite measure, then f is continuous, and thus, (A1) holds for all .

Definition A1.

Let be a measurable set. A discrete set is called

- a uniqueness set (a set of uniqueness) for if the only function satisfying for all is the trivial function ;

- a sampling set (a set of sampling) for if there are constants such that

- an interpolating set (a set of interpolation) for if for each there exists a function satisfying for all .

It follows immediately from (A1) that

- is a uniqueness set for if and only if is complete in ;

- is a sampling set for if and only if is a frame for .

Also, we have the following characterization of interpolation sets for (see p. 129, Theorem 3 in [3]):

- is an interpolating set for if and only if there is a constant such thatmeaning that the lower Riesz inequality of for holds.

Combining with the Bessel inequality (which corresponds to the upper Riesz inequality), we obtain a more convenient statement:

- If is a Bessel sequence in , then is an interpolating set for if and only if is a Riesz sequence in .

In fact, this statement can be proved by elementary functional analytic arguments. Indeed, if is Bessel, i.e., if the synthesis operator defined by is a bounded linear operator (equivalently, the analysis operator defined by is a bounded linear operator), then T is bounded below (that is, the lower Riesz inequality holds) if and only if T is injective and has closed range, if and only if has dense and closed range, i.e., is surjective, which means that is an interpolating set for by (A1).

The statement above is often useful because is necessarily a Bessel sequence in whenever is separated and is bounded (p. 135, Theorem 4 in [3]). Note that is necessarily separated if is a Riesz sequence in (see Proposition 3).

Appendix B. Proof of Some Auxiliary Results

Proof of Lemma 1.

To prove (a), note that for any ,

Since the phase factor for does not affect the Riesz basis property and the Riesz bounds, it follows that is a Riesz basis for with bounds A and B. Consequently, is a Riesz basis for with bounds A and B.

For (b) and (c), note that the modulation is a unitary operator on and that the dilation is also a unitary operator from onto . It is easily seen from Proposition 1(c) that if is a unitary operator between two Hilbert spaces and and if is a Riesz basis for , then is a Riesz basis for . Parts (b) and (c) follow immediately from this statement. □

Proof of Proposition 3.

For simplicity, we will only consider the case .

- (i)

- Assume that . This means that there is a real-valued sequence such thatThen for each , there exists some satisfyingFor each , we partition the interval into k subintervals of equal length : namely, the intervals . Then at least one of the subintervals, which we denote by , must satisfywhere . Letting , we see thatDefine the function by for . Then and . Since , its Fourier transform is continuous on and therefore there exists such that for all . For each , we set so that and thus . It then follows from (A2) thatFor each , we denote the center of the interval by and let be defined by for . Thenwhere we used the fact that for all since is an interval of length . While for all , the right-hand side of (A3) tends to infinity as . Hence, we conclude that is not a Bessel sequence in if .

- (ii)

- Suppose to the contrary that is a Riesz sequence in with Riesz bounds A and B, but the set is not separated. Then there are two sequences and in such that as . Note that is a finite measure set, and for each , we have and as . Thus, we have by the dominated convergence theorem. For , let be the Kronecker delta sequence supported at ; that is, if and is 0 otherwise. Then, since is a Riesz sequence in , we haveyielding a contradiction.

□

Proof of Lemma 2.

Let with for all n, and fix any . Choose a sufficiently large number so that , where is the separation constant of (see Section 2.3). Consider the perturbation of , obtained by rounding each element of to the nearest point in (if is exactly the midpoint of and , then we choose ). Since , all elements in are rounded to distinct points in , i.e., the set has no repeated elements. Clearly, there is a 1:1 correspondence between and , and we have for all .

We claim that for any , there exist constants , and an increasing sequence in satisfying

Once this claim is proved, it follows that the sequence corresponding to , satisfies the condition (3) as desired.

To prove the claim, consider the partition of based on residue modulo N: that is, consider the sets . Since , at least one of these N sets must have a positive upper density, i.e., for some . Then, Szemerédi’s theorem implies that for any , the set contains an arithmetic progression of length : that is, for some and . This means that there is an increasing sequence in satisfying

Since the numbers , are in , it is clear that and . Thus, setting and , we have for , as claimed.

Finally, one can easily force the constant to be a multiple of any prescribed number . This is achieved by considering the partition of based on residue modulo instead of modulo N. □

References

- Higgins, J.R. Sampling Theory in Fourier and Signal Analysis: Foundations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Paley, R.E.A.C.; Wiener, N. Fourier Transforms in the Complex Domain; American Mathematical Society Colloquium Publications; American Mathematical Society: New York, NY, USA, 1934; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.M. An Introduction to Nonharmonic Fourier Series, revised 1st ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fuglede, B. Commuting self-adjoint partial differential operators and a group theoretic problem. J. Func. Anal. 1974, 16, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, N.; Matolcsi, M. The Fuglede conjecture for convex domains is true in all dimensions. Acta Math. 2022, 228, 385–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosevich, A.; Katz, N.; Pedersen, S. Fourier bases and a distance problem of Erdős. Math. Res. Lett. 1999, 6, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubarskii, Y.I.; Rashkovskii, A. Complete interpolation sequences for Fourier transforms supported by convex symmetric polygons. Ark. Mat. 2000, 38, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, G.; Nitzan, S. Combining Riesz bases. Invent. Math. 2015, 199, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kozma, G.; Nitzan, S. Combining Riesz bases in Rd. Rev. Mat. Iberoam. 2016, 32, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debernardi, A.; Lev, N. Riesz bases of exponentials for convex polytopes with symmetric faces. J. Eur. Math. Soc. 2022, 24, 3017–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragea, A.; Lee, D.G. A note on exponential Riesz bases. Sampl. Theory Signal Process. Data Anal. 2022, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.G.; Pfander, G.E.; Walnut, D. Bases of complex exponentials with restricted supports. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2023, 521, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, G.; Nitzan, S.; Olevskii, A. A set with no Riesz basis of exponentials. Rev. Mat. Iberoam. 2023, 39, 2007–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grepstad, S.; Lev, N. Multi-tiling and Riesz bases. Adv. Math. 2014, 252, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, B.; Meyer, Y. Quasicrystals are sets of stable sampling. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris Ser. I 2008, 346, 1235–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, B.; Meyer, Y. Simple quasicrystals are sets of stable sampling. Complex Var. Elliptic Equ. 2010, 55, 947–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolountzakis, M.N. Multiple lattice tiles and Riesz bases of exponentials. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2015, 143, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agora, E.; Antezana, J.; Cabrelli, C. Multi-tiling sets, Riesz bases, and sampling near the critical density in LCA groups. Adv. Math. 2015, 285, 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrelli, C.; Carbajal, D. Riesz bases of exponentials on unbounded multi-tiles. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2018, 146, 1991–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrelli, C.; Hare, K.; Molter, U. Riesz bases of exponentials and the Bohr topology. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2021, 149, 2121–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, S.; Olevskii, A.; Ulanovskii, A. Exponential frames on unbounded sets. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2016, 144, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, A.W.; Spielman, D.A.; Srivastava, N. Interlacing families II: Mixed characteristic polynomials and the Kadison-Singer problem. Ann. Math. 2015, 182, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olevskii, A.; Ulanovskii, A. Universal sampling of band-limited signals. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris Ser. I 2006, 342, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olevskii, A.; Ulanovskii, A. Universal sampling and interpolation of band-limited signals. Geom. Funct. Anal. 2008, 18, 1029–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olevskii, A.; Ulanovskii, A. Functions with Disconnected Spectrum: Sampling, Interpolation, Translates; University Lecture Series; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2016; Volume 65. [Google Scholar]

- Folland, G.B. Real Analysis, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gelbaum, B.R.; Olmsted, J.M.H. Counterexamples in Analysis; Dover Publications Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, O. An Introduction to Frames and Riesz Bases, 2nd ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, C. A Basis Theory Primer, expanded ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bownik, M.; Casazza, P.; Marcus, A.W.; Speegle, D. Improved bounds in Weaver and Feichtinger conjectures. J. Reine Angew. Math. (Crelle) 2019, 749, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, C. History and evolution of the density theorem for Gabor frames. J. Fourier Anal. Appl. 2007, 12, 113–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, O.; Deng, B.; Heil, C. Density of Gabor frames. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 1999, 7, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröchenig, K.; Ortega-Cerdà, J.; Romero, J.L. Deformation of Gabor systems. Adv. Math. 2015, 277, 388–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, H.J. Necessary density conditions for sampling and interpolation of certain entire functions. Acta Math. 1967, 117, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, S.; Olevskii, A. Revisiting Landau’s density theorems for Paley-Wiener spaces. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris Ser. I 2012, 350, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szemerédi, E. On sets of integers containing no k elements in arithmetic progression. Acta Arith. 1975, 27, 199–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergelson, V.; Leibman, A. Polynomial extensions of van der Waerden’s and Szemerédi’s theorems. J. Am. Math. Soc. 1996, 9, 725–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdös, P.; Sárkxoxzy, A. On differences and sums of integers, II. Bull. Soc. Math. Grèce (N.S.) 1977, 18, 204–223. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzikinakis, N.; Lesigne, E.; Wierdl, M. Random differences in Szemerédi’s theorem and related results. J. Anal. Math. 2016, 130, 91–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).