1. Introduction

Consider a convex compact set C with a nonempty interior in Euclidean space , . Let be a point on its boundary, and let be a plane of support to C at . Consider the part of the boundary containing and bounded by a plane parallel with . We are interested in studying the limiting properties of this part of the boundary when the bounding plane approaches

In what follows, a convex compact set with a nonempty interior will be called a convex body.

The point is called regular if the plane of support at this point is unique and singular otherwise. It is well known that regular points form a full-measure set in .

Let e denote the outward unit normal vector to . Take , and let be the plane parallel with at the distance t from it, on the side opposite to the normal vector. Thus, the plane is given by the equation and by the equation . The body C is contained in the closed half-space . Here and in what follows, means the scalar product.

Consider the convex body:

In other words,

is the part of

C cut off by the plane

. The boundary of

is the union of the convex set of codimension 1:

and the convex surface:

thus,

.

In what follows, we will denote as the m-dimensional Hausdorff measure of the Borel set . By default, means .

Let

denote the outward unit normal to

C at a regular point

, and let

S be a Borel subset of

.

The surface area measure induced by S is the Borel measure

defined in

satisfying

for any Borel subset

. In the case when

S coincides with

, we obtain the well-known measure

called the

surface area measure of the convex body C. For this measure, the following well-known relation takes place:

Denote by

the normalized measure induced by the surface

; more precisely,

That is, for any Borel set

, it holds

The surface area measure of

equals

; hence,

Here and in what follows,

means the unit atom supported at

e. Applying Formula (

3) to

, one obtains

We say that

weakly converges to

as

and denote

, if for any continuous function

f on

, it holds

Similarly, we say that

is a

weak partial limit of the measure

, if there exists a sequence of positive numbers

converging to 0 such that, for any continuous function

f on

, it holds

In this article, we are going to study the limiting properties of the measure as .

One such property is derived immediately. Let

be a weak limit or a weak partial limit of

. Passing to the limit

or to the limit

in Formula (

4), one obtains

The

tangent cone to

C at

is the closure of the union of all rays with vertex at

that intersect

. Equivalently, the tangent cone at

is the smallest closed cone with the vertex at

that contains

C; see

Figure 1.

If the tangent cone at is a half-space, then the point is regular, and vice versa.

The normal cone to C at is the union of all rays with vertex at whose director vector is the outward normal to a plane of support at . It is denoted as . An equivalent definition is the following: the normal cone at is the set of points r that satisfy for all . The normal cone to a convex body does not contain straight lines. Both tangent and normal cones are, of course, convex sets.

If the dimension of

equals

d (equivalently, if the tangent cone does not contain straight lines), then

is called a

conical point of

C. If the dimension of

equals 1, then

is regular, and vice versa. In the intermediate case, that is if the dimension of

is greater than 1, but smaller than

d,

is called a

ridge point. This notation goes back to Pogorelov [

1].

The motivation for this study comes, to a great extent, from extremal problems in classes of convex bodies and, in particular, from Newton’s problem of least resistance for convex bodies [

2]. It is natural to try to develop a geometric method of the small variation of convex bodies for such problems, and perhaps, the simplest way would be cutting a small part of the body by a plane. This method proved itself to be effective in the case of Newton’s problem. Let us describe this problem in some detail.

The problem in a class of radially symmetric bodies was first stated and solved by Newton himself in 1687 in [

3]. The more general version of the problem was posed by Buttazzo and Kawohl in 1993 in [

2]. This general problem can be formulated in the functional form as follows:

Find the smallest value of the functional

in the class of convex functions

satisfying

, where

is a planar convex body and

.

The physical meaning of this problem is as follows: find the optimal streamlined shape of a convex body moving downwards through an extremely rarefied medium, provided that the body–particle collisions are perfectly elastic.

Problem (

6) (along with its further generalizations) has been studied in various papers including [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], but has not been solved completely until now.

It was conjectured in 1995 in [

6] that the slope of the graph of an optimal function near the zero level set

equals 1. This conjecture was numerically disproven by Wachsmuth (personal communication) in the case when

has an empty interior and, therefore, is a line segment. Moreover, numerical simulation shows that the infimum of

in the complement of

is strictly greater than 1.

On the other hand, this conjecture was proven by the author in [

14] in the case when

has a nonempty interior. More precisely, it was proven that if

u minimizes functional (

6), then for almost all

, it holds

The proof is based on the results concerning local properties of convex surfaces near ridge points in the case

. These results were formulated, with the proofs being briefly outlined, in [

14].

Remark 1. The limiting behavior ofin the caseis quite simple. In this case, the tangent cone is an angle, which degenerates to a half-plane if the point is regular. We will call it the tangent angle. Let the tangent angle toatbe given byand e be given by Thus,andare the outward unit normals to the sides of the angle, and e is the outward unit normal to a line of support at. Then, the limiting measure is the sum of two atoms: The proof of this relation is simple and is left to the reader.

Note that if the pointis regular, then. It may also happen that the point is singular, that is, and e coincides with one of the vectorsand. In both cases, the limiting measure is an atom: The limiting behavior of is different for different kinds of points:

(a) If the point is regular, then the limiting measure is an atom.

(b) If r is a conical point, then the limiting measure coincides with the measure induced by the part of the boundary of the tangent cone cut off by a plane , (note that all the induced measures with are proportional).

(c) The case of ridge points is the most interesting. In this case, the limiting measure may not exist, and the characterization of all possible partial limits is a difficult task.

Still, the study is nontrivial also in Cases (a) and (b). In this paper, we restrict ourselves to these cases, while Case (c) is postponed to the future. The main results of the paper are contained in the following Theorems 1 and 2.

Theorem 1. Ifis a regular point of, then Let

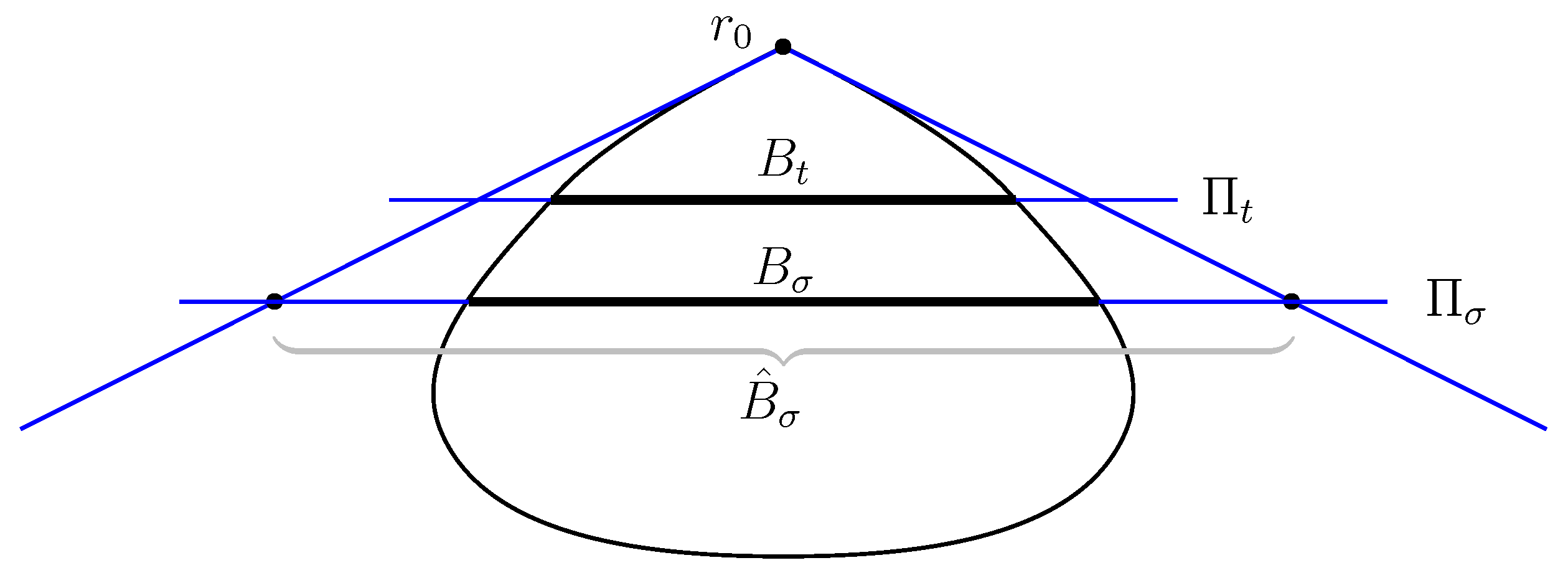

be a conical point,

K be the tangent cone at

,

be the part of

containing

cut off by the plane

, and

be the intersection of the cone with the cutting plane

,

, that is

Let be the part of the cone cut off by the plane ; its boundary is .

All measures induced by

are proportional, that is the measure:

does not depend on

t.

Theorem 2. Ifis a conical point of, then 2. Proof of Theorem 1

The proof is based on several propositions.

Consider a convex set , and let be its -dimensional volume and be the -dimensional volume of its boundary.

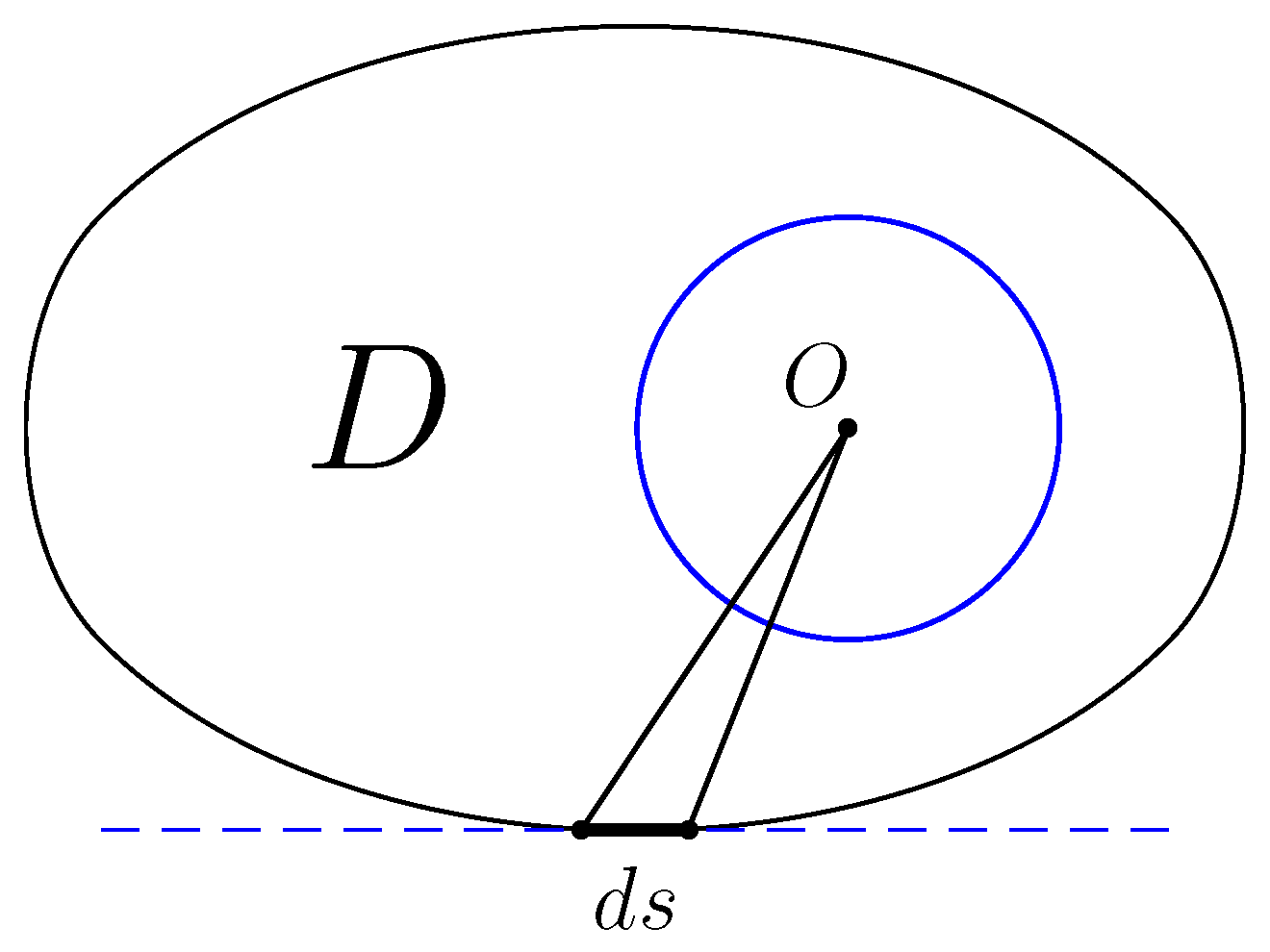

Proposition 1. If D contains a circle of radius a, then Proof. Let

be an infinitesimal element of the boundary of

D and denote by

its

-dimensional volume. Consider the pyramid with the vertex at the center

O of the circle and with the base

, that is the union of line segments joining

O with the points of

. Let

be the element of the

-dimensional volume of this pyramid; see

Figure 2. Then, we have

and therefore,

From here follows Inequality (

9). □

Figure 2.

The convex set D containing a circle of radius a.

Figure 2.

The convex set D containing a circle of radius a.

Consider Euclidean space with the coordinates , , and fix and .

Proposition 2. Let a convex bodybe contained between the planesand,. Let D be the image of C under the natural projection ofon the x-plane,, and letbe the-dimensional volume of. Let a domainbe such that the outward normalat each regular pointsatisfies. (In other words, the angles betweenforand the vectorsare.) Then, Proof. The body

C is bounded below by the graph of a convex function, say

, and above by the graph of a concave function, say

; see

Figure 3. Both functions are defined on

D. That is, we have

Let denote the intersection of with the graph of . Clearly, if a point is regular and belongs to , then .

For

, denote by

the

-dimensional volume of the set:

One clearly has

. Let

s be the

-dimensional parameter in

, and let

be the element of the

-dimensional volume in

. Denote by

the point in

corresponding to the parameter

s. Then, the

-dimensional volume of

equals

The same argument holds for . It follows that . □

Proposition 3. If a convex set incontainsmutually orthogonal line segments of length 1, then it also contains a ball of radius.

Proof. Denote the convex set by D and the segments by , . Since all points lie in D, each convex combination of the form , where J denotes a map , also lies in D. The convex combination of the set of points is a hypercube with the size of length and contains the ball of radius with the center at the hypercube’s center. □

Proposition 4. containsmutually orthogonal line segments of length, whereas.

Proof. Take a unit vector orthogonal to e, and consider the 2-dimensional plane through parallel with e and . The intersection is a 2-dimensional convex body, and is a regular point on its boundary; the intersection is a line orthogonal to e at the distance t from ; the intersection is a line segment (maybe degenerating to a point or the empty set). Equivalently, this segment is the intersection of the body with the line . Since the point is regular, we conclude that the length of this segment satisfies as .

Now, choose unit vectors in such a way that the set of vectors forms an orthonormal system in . For each , draw the 2-dimensional plane through parallel with e and . The intersections are line segments parallel with , and therefore, they are mutually orthogonal. The lengths of these segments satisfy as . Taking , one comes to the statement of the proposition. □

Recall that is the intersection of with the half-space and is the plane of the equation . For , denote by the part of containing the regular points r satisfying . In other words, is the set of regular points r in such that the angle between e and is greater than or equal to .

Proof. Consider a coordinate system , such that the x-plane coincides with and the z-axis is directed toward the vector e. For sufficiently small, the intersection of and the interior of C is nonempty for all . The angle between and the outward normal at each regular point of , is greater than a positive value . That is, for any regular point , it holds . Without loss of generality, one can take , and then, for all regular points , it holds .

In the chosen coordinate system, is contained between the planes and . Denote by the image of under the natural projection . The domain contains and is contained in the -neighborhood of ; hence, its -dimensional volume does not exceed , where means the area of the -dimensional unit sphere.

Applying Proposition 2 to the body

and the domain

, one obtains

By Propositions 3 and 4,

contains a ball of radius

, and therefore, by Proposition 1,

and additionally,

, where

means the volume of the unit ball in

. Hence,

□

Let us now finish the proof of Theorem 1.

Recall that

is the surface area measure induced by

S. For all

, one has

Proposition 5 implies that the measure

converges to 0 as

. Indeed, for any continuous function

f on

,

On the other hand, the measure

is supported in the set in

containing all points whose radius vector forms the angle

with

e. It follows that each partial limit of

and, therefore, each partial limit of

are supported in this set. Since

can be made arbitrary small, one concludes that each partial limit of

is proportional to

. Finally, utilizing Equality (

5) true for each partial limit

, one concludes that the limit of

exists and is equal to

.

3. Proof of Theorem 2

In the proof, we will use the well-known fact that the surface area measure is continuous with respect to the Hausdorff topology in the space of convex bodies.

More precisely, we say that a family of convex bodies , in converges to a convex body as in the sense of Hausdorff and write , if for any , there exists such that for all , is contained in the -neighborhood of C and C is contained in the -neighborhood of .

It is well known that if , then as .

Choose

so

, and therefore,

Let the origin coincide with the point

, that is

; then, the homothety of a set

with the center at

and ratio

k is

. See

Figure 4.

Proposition 6. .

Proof. Note that for all positive

and

,

Additionally, since the tangent cone

K contains

C, then

contains

, and so,

Let now

. Since

and

belong to

C, so does their linear combination,

On the other hand,

. It follows that

. We conclude that

that is

form a nested family of sets contained in

.

Suppose that

does not converge to

. This implies that the closure of the union

is contained in, but does not coincide with,

.

The union:

is a cone with the vertex at

; it is contained in the tangent cone

K, but does not coincide with it. On the other hand,

that is

C is contained in the cone

, which is smaller than the tangent cone

K. This contradiction proves our proposition. □

From Proposition 6, it follows, in particular, that

and therefore,

Since the convex body contains both and , we have

Recall that

is the part of the tangent cone cut off by the plane

. We have

. Since by Proposition 6,

, we conclude that

, that is

Using this relation and the double inclusion:

one concludes that

converges to

in the sense of Hausdorff, and therefore,

Using that

and

and using (

12), one obtains

and taking account of (

11), one obtains

Theorem 2 is proven.