Competitive Adsorption of Thickeners and Superplasticizers in Cemented Paste Backfill and Synergistic Regulation of Rheology and Strength

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Tailings

2.1.2. Cement

2.1.3. Admixture and Water

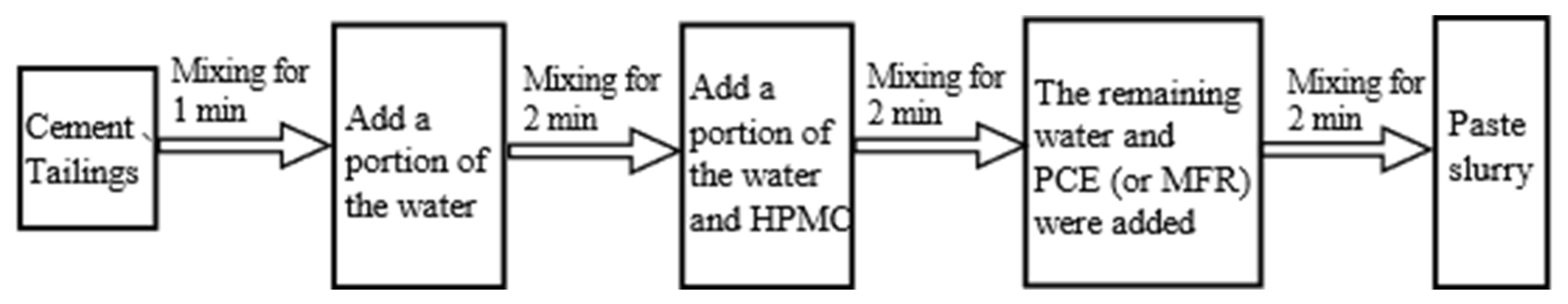

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Flowability Test

2.2.2. Rheological Test

2.2.3. Mechanical Testing

2.2.4. Microstructure

2.3. Experimental Program

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Combined Superplasticizers on Flowability

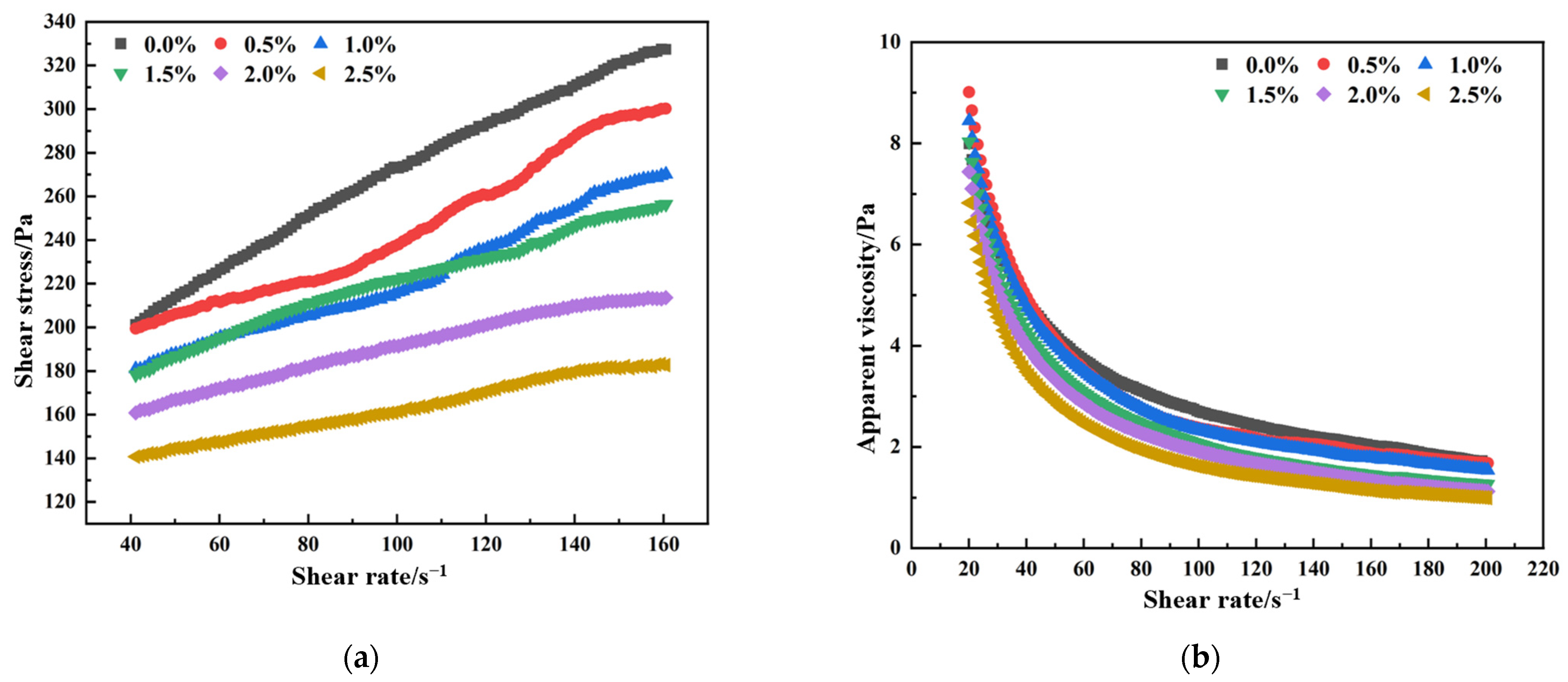

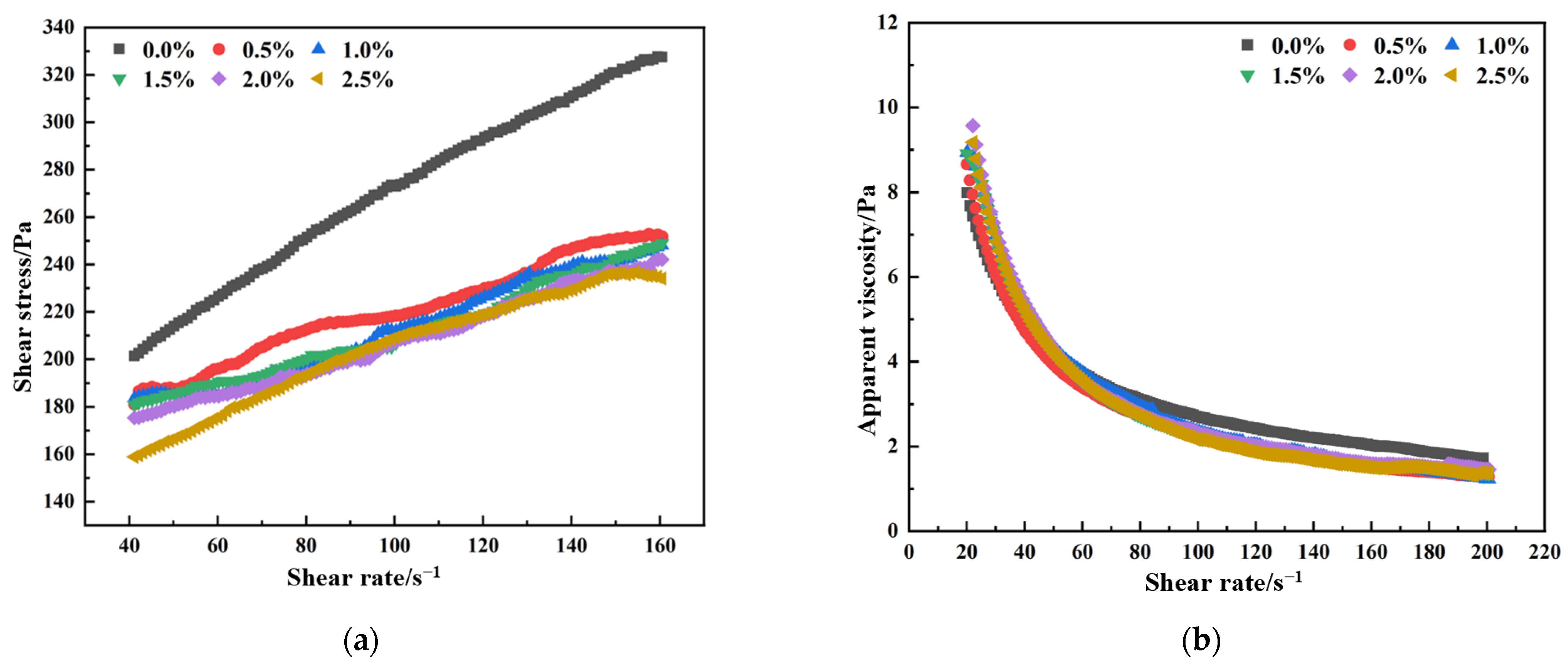

3.2. Effect of Combined Superplasticizers on Rheological Properties

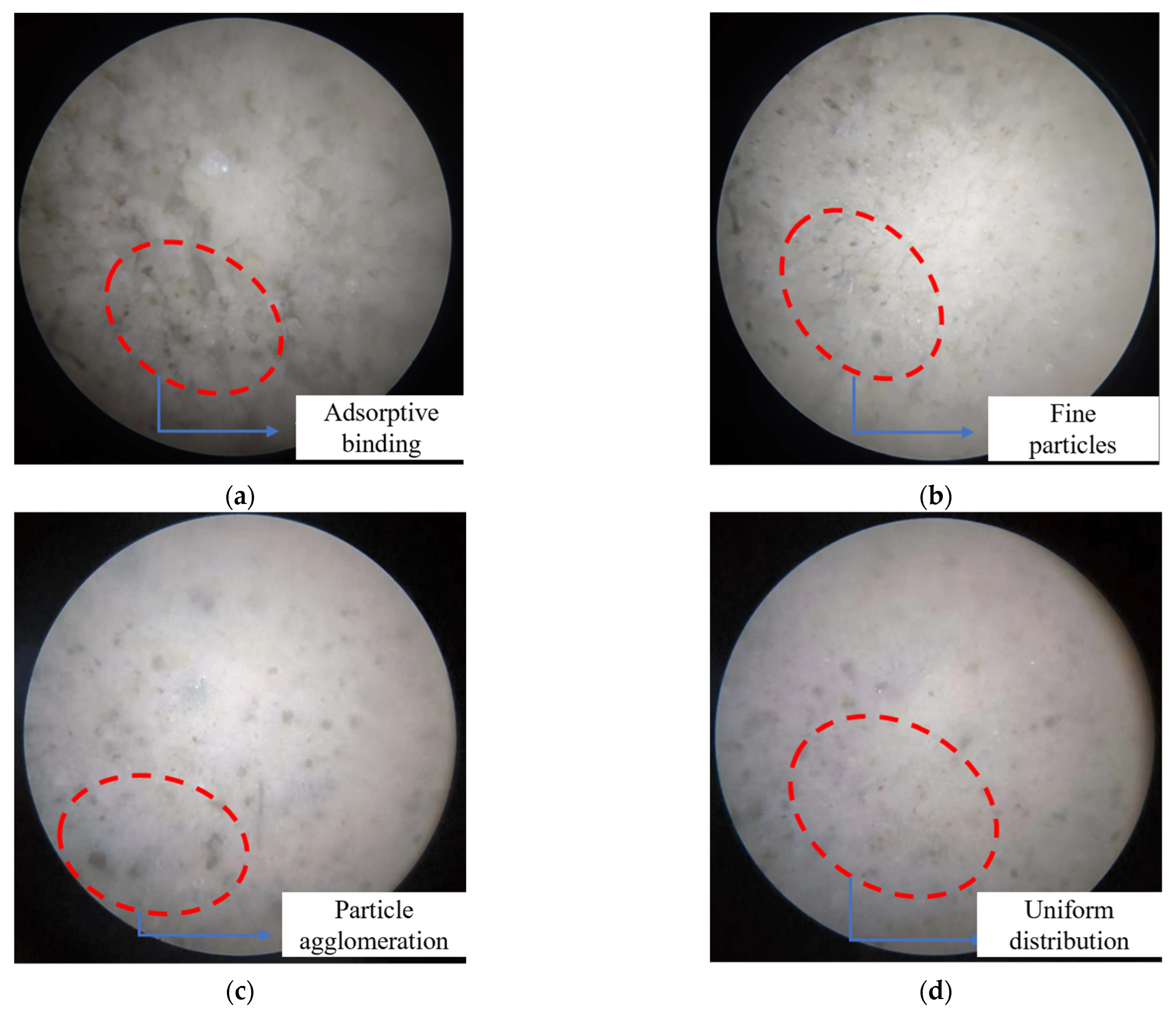

3.3. Mesostructural Analysis

3.4. Effect on Compressive Strength

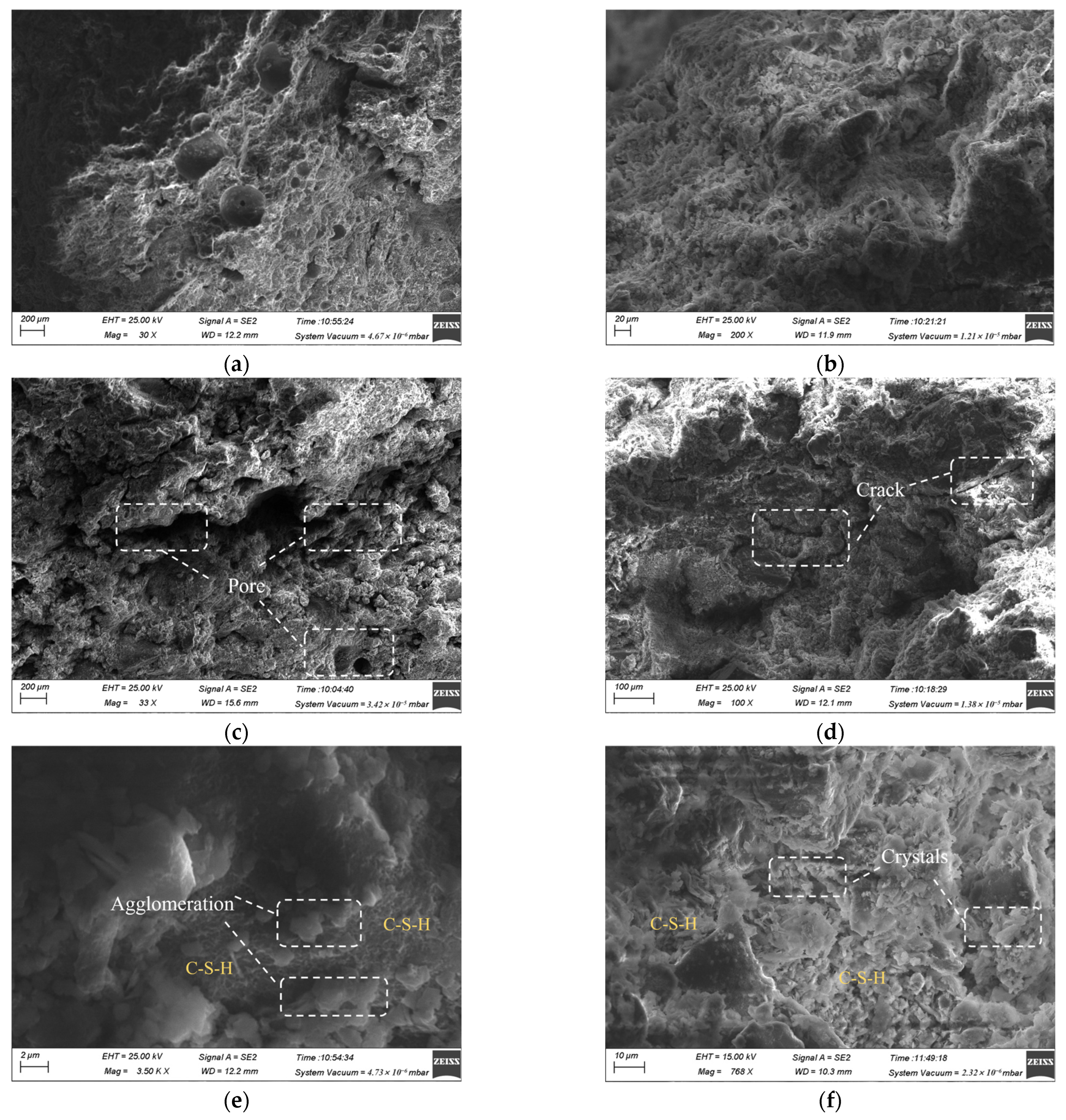

3.5. SEM Microstructural Analysis

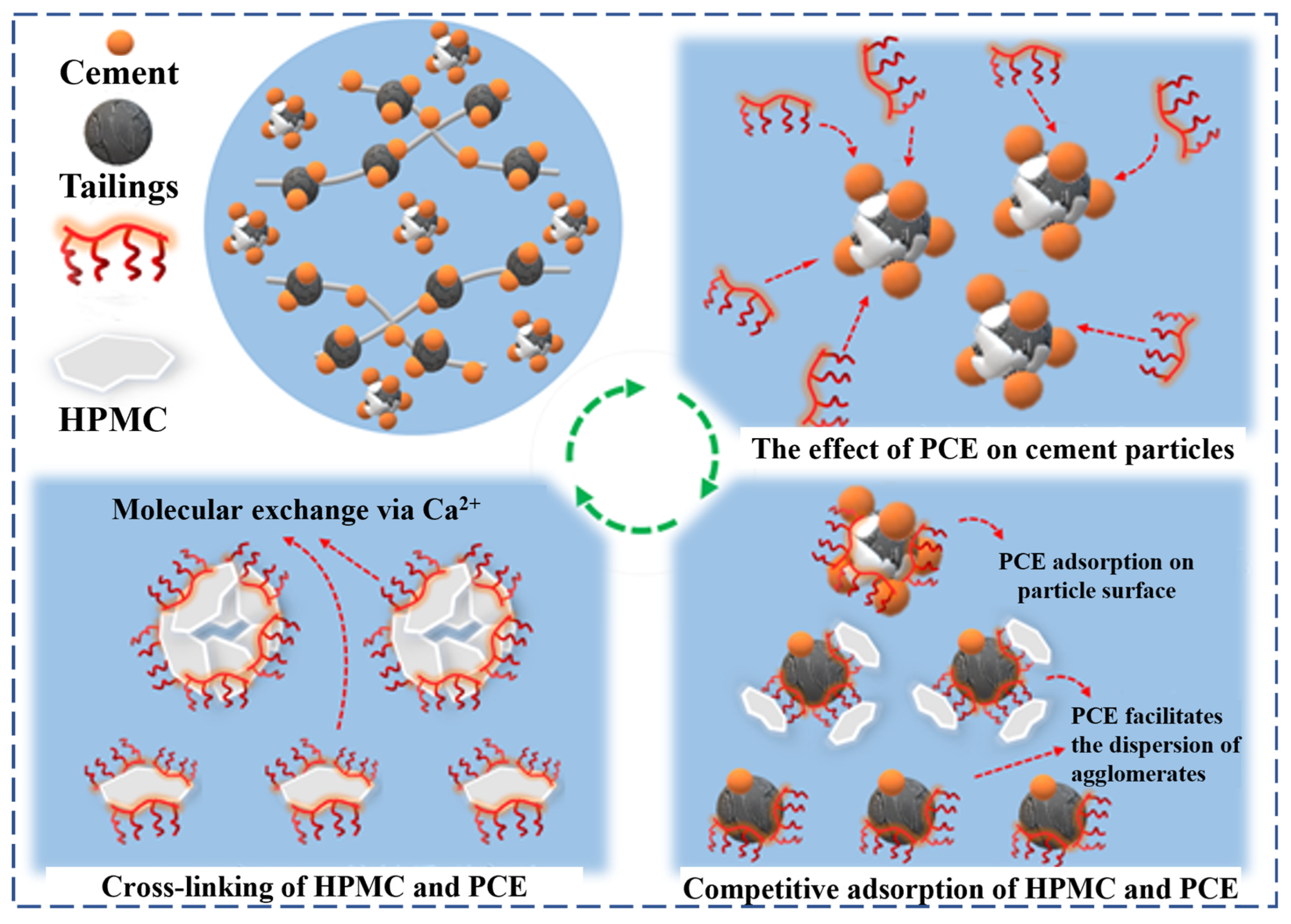

4. Analysis of the Synergistic Mechanism

5. Conclusions

- PCE exhibits markedly better rheological regulation compared to MFR. In full-tailings paste modified with 0.1% HPMC, PCE significantly outperforms MFR in enhancing fluidity and deformability. At a dosage of 2.5%, PCE reduces yield stress by 22.1% and plastic viscosity by 64.3%, whereas MFR shows a saturation effect beyond 2.0% with minimal gain. Through strong steric hindrance, PCE effectively mitigates the flocculation induced by HPMC.

- In full-tailings paste modified with 0.1% HPMC, a PCE dosage range of 1.5%–2.0% is recommended for this full-tailings CPB system. This range effectively balances the reduction in pumping pressure with the maintenance of sufficient viscosity to prevent segregation during deep-shaft transport, while simultaneously securing robust mechanical support in the CPB.

- Incorporation of PCE promotes microstructural homogenization and reduces macropore defects, leading to consistent compressive strength gains at 3, 7, and 28 days with increasing dosage. This HPMC–PCE binary system not only fulfills the transportability requirements for deep-shaft backfilling but also ensures the necessary mechanical support of the backfill structure.

- Flocculation induced by HPMC—arising from intermolecular and intramolecular complexation with Ca2+—is effectively counteracted by PCE. PCE competes for adsorption sites and deposits onto HPMC chains, weakening their cohesive forces. This interaction selectively deagglomerates large-particle flocs while retaining essential viscosity, establishing a synergistic balance. The result is an optimized microstructural framework suitable for long-distance transport in deep mining operations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPB | Cemented Paste Backfill |

| HPMC | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose |

| PCE | Polycarboxylate Superplasticizer |

| MFR | Melamine-Formaldehyde Resin |

| VMA | Viscosity Modifying Agent |

| UCS | Uniaxial Compressive Strength |

References

- Cai, M.; Li, P.; Tan, W.; Ren, F. Key Engineering Technologies to Achieve Green, Intelligent, and Sustainable Development of Deep Metal Mines in China. Engineering 2021, 7, 1513–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. 60 years development and prospect of mining systems engineering. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 261–279. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Jiao, H.; Yin, S.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y. Systematic review of mixing technology for recycling waste tailings as cemented paste backfill in mines of China. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2023, 30, 1430–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, S. Study on rheological properties of large particle gangue slurry and its drag reduction effect caused by wall slippage in pipeline transportation. Powder Technol. 2025, 452, 120573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.Y.; Wu, A.X.; Wu, S.C.; Zhu, J.Q.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Niu, Y.H. Research status and development trend of solid waste backfill in metal mines. Chin. J. Eng. 2022, 44, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yi, S. Research status and prospects of efficient green mining technology and intelligent equipment for ultra large deep iron mines. Chin. J. Eng. 2024, 46, 2147–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Sada, H.; Mamadou, F. Reactivity of cemented paste backfill containing polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer. Miner. Eng. 2022, 188, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikonda, R.K.; Mbonimpa, M.; Belem, T. Specific mixing energy of cemented paste backfill, Part I: Laboratory determination and influence on the consistency. Minerals 2021, 11, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Fu, B.; Fu, S.; Li, Z.; Gong, J. Bleeding characteristics and water migration mechanism of backfill slurry. J. Henan Polytech. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2025, 44, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Li, J.; Yin, S.; Jiao, H.; Chen, X.; Kou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, H. Mechanism of bubble action in backfill slurry and the evolution of its rheological properties. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 1894−1905. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, A.; Jiang, H.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, X. Evaluation of time-dependent rheological properties of cemented paste backfill incorporating superplasticizer with special focus on thixotropy and static yield stress. J. Cent. South Univ. 2022, 29, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Jiang, H.; Ren, L.; Yilmaz, E.; Li, Y. Rheological properties of cemented paste backfill with alkali-activated slag. Minerals 2020, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Li, H.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Ruan, Z. Status and prospects of researches on rheology of paste backfill using unclassified ailings (Part 1): Concepts, characteristics and models. Chin. J. Eng. 2020, 42, 803–813. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, X.; Zhang, C.; Chang, Y. Coupled Effects of Time and Temperature on the Rheological and Pipe Flow Properties of Cemented Paste Backfill. Minerals 2024, 14, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Hao, S.; Zhang, H.; Hu, C.; Cao, D. Modeling the resistance of unclassified waste rock paste slurries mixed with water-reducing agents. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2022, 43, 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Fu, X.; Liu, D.; Li, Y. Competitive adsorption of polycarboxylate superplasticizer by gangue powder and cement in backfilling engineering. Chin. J. Eng. 2025, 47, 2388–2396. [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, A.; Lecompte, T.; Khelifi, H.; Brumaud, C.; Hot, J.; Roussel, N. Yield stress and bleeding of fresh cement pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yilmaz, E.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H. Effect of superplasticizer type and dosage on fluidity and strength behavior of cemented tailings backfill with different solid contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhou, M. Properties comparison of mortars with welan gum or cellulose ether. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 102, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Shao, Y.; Wu, A.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. A systematic review of paste technology in metal mines for cleaner production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Yang, B.; Yang, F.; Ren, Q.; e Silva, M.C. Fluidity and rheological properties with time-dependence of cemented fine-grained coal gangue backfill containing HPMC using response surface method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 451, 138691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Zhang, M.; Li, G. Preparation and characterization of collagen/hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) blend film. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 119, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Bai, Y.; Tang, J.; Su, H.; Zhang, F.; Ma, H.; Ge, L.; Cai, Y. Effects of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose on anti-dispersion and rheology of alkali-activated materials in underwater engineering. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 132135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulichen, D.; Kainz, J.; Plank, J. Working mechanism of methyl hydroxyethyl cellulose (MHEC) as water retention agent. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chen, N.; Wang, R. Study on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose modified Portland cement-sulphoaluminate cement composites: Rheology, setting time, mechanical strength, resistance to chloride ingress, early reaction kinetics and microstructure. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Jin, X.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, F. Study on Stability and Fluidity of HPMC-Modified Gangue Slurry with Industrial Validation. Materials 2025, 18, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, X. Effect of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose on rheological properties of cement-limestone paste. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2023, 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Irawan, S.; Memon, K.R.; Kumar, S.; Elrayah, A.A. Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose as a Primary Viscosifying Agent in Cement Slurry at High Temperature. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2013, 8, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, M.; Flatt, R.J.; Puertas, F.; Sánchez-Herencia, A. Compatibility Between Polycarboxylate and Viscosity-Modifying Admixtures in Cement Pastes; ACI Special Publication: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2012; pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Deng, H.; Taheri, A.; Deng, J.; Ke, B. Effects of superplasticizer on the hydration, consistency, and strength development of cemented paste backfill. Minerals 2018, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessaies-Bey, H.; Khayat, K.H.; Palacios, M.; Schmidt, W. Viscosity modifying agents: Key components of advanced cement-based materials with adapted rheology. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 152, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 2419-2005; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China. Test Method for Fluidity of Cement Mortar. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2005.

- JGJ/T 70-2009; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for Test Method of Basic Properties of Construction Mortar. China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Yang, L.; Jia, H.; Jiao, H.; Dong, M.; Yang, T. The Mechanism of Viscosity-Enhancing Admixture in Backfill Slurry and the Evolution of Its Rheological Properties. Minerals 2023, 13, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Shao, Y.; Xiao, G.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Effect of polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer on performances of super fine tailings paste backfill. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2016, 26, 2647–2655. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Fall, M.; Cai, S.J. Coupling temperature, cement hydration and rheological behaviour of fresh cemented paste backfill. Miner. Eng. 2013, 42, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Peng, Y.; Tan, H.; Jian, S.; Zhi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Qi, H.; Zhang, Z.; He, X. Effect of hydroxypropyl-methyl cellulose ether on rheology of cement paste plasticized by polycarboxylate superplasticizer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 160, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, P.; Li, Z.; Jiao, H.; Li, P.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, Y. The stabilizing effect and mechanism of nano-silica on bubbles in cemented paste backfill. Powder Technol. 2025, 470, 122005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judžentienė, A.; Zdaniauskienė, A.; Ignatjev, I.; Druteikienė, R. Evaluation of Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Cement Superplasticizer Based on Polymelamine Sulphonate. Materials 2024, 17, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekin, I.; Pekgöz, M.; Saleh, N.K.; Kiamahalleh, M.V.; Gholampour, A.; Gencel, O.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Compatibility of melamine formaldehyde-and polycarboxylate-based superplasticizers on slag/sintering ash-based geopolymer paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Na2O | Fe2O3 | SO3 | MgO | K2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| content (%) | 42.45 | 22.35 | 14.05 | 5.22 | 4.36 | 4.3 | 3.22 | 4.05 |

| Composition | MgO | SiO2 | Na2O | K2O | Al2O3 | SO3 | Fe2O3 | CaO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| content (%) | 1.40 | 20.70 | 0.18 | 0.48 | 4.50 | 2.60 | 3.30 | 65.10 |

| Group | Admixture Dosage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickener | Dosage | Superplasticizer | Dosage | |

| N | HPMC | 0.1% | 0% | 0% |

| P-1 | PCE | 0.5% | ||

| P-2 | 1.0% | |||

| P-3 | 1.5% | |||

| P-4 | 2.0% | |||

| P-5 | 2.5% | |||

| M-1 | MFR | 0.5% | ||

| M-2 | 1.0% | |||

| M-3 | 1.5% | |||

| M-4 | 2.0% | |||

| M-5 | 2.5% | |||

| Group | d0 (mm) | D (mm) | Γ |

|---|---|---|---|

| H-1 | 100 | 156 | 1.43 |

| P-1 | 100 | 189 | 2.57 |

| P-2 | 100 | 196 | 2.84 |

| P-3 | 100 | 217 | 3.71 |

| P-4 | 100 | 230 | 4.29 |

| P-5 | 100 | 256 | 5.55 |

| M-1 | 100 | 166 | 1.76 |

| M-2 | 100 | 171 | 1.92 |

| M-3 | 100 | 178 | 2.17 |

| M-4 | 100 | 185 | 2.42 |

| M-5 | 100 | 185 | 2.42 |

| Group | Shear Stress/Pa | Apparent Viscosity/Pa·s | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| H-1 | 160.064 | 1.063 | 0.996 |

| P-1 | 153.198 | 0.914 | 0.971 |

| P-2 | 145.22 | 0.772 | 0.994 |

| P-3 | 137.64 | 0.628 | 0.968 |

| P-4 | 134.576 | 0.461 | 0.966 |

| P-5 | 124.685 | 0.380 | 0.964 |

| M-1 | 156.337 | 0.947 | 0.991 |

| M-2 | 151.613 | 0.894 | 0.993 |

| M-3 | 147.822 | 0.883 | 0.998 |

| M-4 | 144.523 | 0.846 | 0.996 |

| M-5 | 142.328 | 0.827 | 0.983 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Kou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, T.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S. Competitive Adsorption of Thickeners and Superplasticizers in Cemented Paste Backfill and Synergistic Regulation of Rheology and Strength. Minerals 2026, 16, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010043

Yang L, Wang Y, Kou Y, Wang Z, Li T, Li Q, Zhang H, Chen S. Competitive Adsorption of Thickeners and Superplasticizers in Cemented Paste Backfill and Synergistic Regulation of Rheology and Strength. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Liuhua, Yongbin Wang, Yunpeng Kou, Zengjia Wang, Teng Li, Quanming Li, Hong Zhang, and Shuisheng Chen. 2026. "Competitive Adsorption of Thickeners and Superplasticizers in Cemented Paste Backfill and Synergistic Regulation of Rheology and Strength" Minerals 16, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010043

APA StyleYang, L., Wang, Y., Kou, Y., Wang, Z., Li, T., Li, Q., Zhang, H., & Chen, S. (2026). Competitive Adsorption of Thickeners and Superplasticizers in Cemented Paste Backfill and Synergistic Regulation of Rheology and Strength. Minerals, 16(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010043