1. Introduction

There is growing interest in considering the IP effects in airborne electromagnetic (AEM) data. Until recently, this has been done using only the 1D approach, in which the earth model is horizontally layered at each transmitter–receiver location [

1,

2,

3]. The inverse geoelectrical model under the entire survey line is produced by stitching together and interpolating these 1D sections. This approach has the same limitations as the conventional 1D conductivity-only inversion, which can yield spurious results and misplace three-dimensional (3D) targets.

To address these challenges, Cox et al. [

4,

5,

6] have developed a computationally efficient and physically rigorous 3D inversion methodology for AEM data that explicitly accounts for both electromagnetic induction and IP effects, thereby incorporating the full physics of the problem. This framework enables the simultaneous recovery of 3D electrical conductivity and chargeability distributions from AEM observations, which is essential for the reliable use of airborne survey results in mineral exploration.

Similarly, advanced magnetic inversion methods capable of resolving both induced and remanent magnetization are crucial in geologically complex terrains where remanence contributes significantly to the magnetic anomaly. The effect of remanence on magnetic data inversion has been studied in several publications [

7,

8,

9]. Zhdanov and Jorgensen [

10,

11] introduced a robust inversion strategy that jointly estimates the induced and remanent components of magnetization within a constrained inversion workflow. The method employs a vector magnetization model that determines the full magnetization direction in each cell, partitioned into an induced component aligned with the present-day geomagnetic field and a remanent component associated with paleomagnetic processes. Regularization constraints are incorporated to promote spatial continuity and geological realism, enabling the recovery of physically meaningful magnetization models even under strong remanent conditions.

We have applied these novel methods to analyze the AEM and TMI data collected within the Asankrangwa Gold Belt in central Ghana. This belt is widely recognized as one of the world’s premier gold provinces, comparable in scale and significance to the Abitibi Belt of Canada and the Yilgarn Craton of Western Australia. It forms part of the West African Craton, a stable Archean—Proterozoic crustal nucleus that has hosted multiple episodes of orogenic gold mineralization. Gold extraction in the region dates back to pre-colonial times, with systematic modern exploration beginning in the late nineteenth century.

The Mpatasie concession is situated within the central portion of the Asankrangwa Belt, along a regionally extensive shear zone known to localize significant gold mineralization. This same structural corridor hosts several major deposits, including Obuasi, Konongo, and Edikan. The concession therefore benefits from both a favorable geological setting and a proven mineralizing system, underscoring its high exploration potential.

Commercial mining in the area was previously conducted by Resolute Amansie Limited between the late 1990s and 2002. Operations involved multiple open-pit mines and yielded more than one million ounces of gold. Mining activities ceased due to unfavorable gold prices rather than resource depletion, indicating that substantial mineral potential remains untested. Recent exploration campaigns have revisited the Mpatasie concession employing advanced geophysical and geochemical techniques, including high-resolution airborne surveys and state-of-the-art inversion methodologies. The present study integrates these datasets into a coherent geological and geophysical interpretation that provides the foundation for renewed exploration targeting.

Figure 1 shows the location of the study area positioned between the Ashanti and Sefwi gold belts.

In this work, we focus on the analysis of airborne electromagnetic (AEM) and total magnetic intensity (TMI) datasets acquired over the concession. Until recently, these data had not been examined using contemporary 3D inversion techniques. We apply a rigorous full-3D inversion of the AEM data to recover both electrical conductivity and induced polarization parameters (primarily chargeability). In addition, the TMI data are interpreted using recently developed advanced 3D magnetic inversion methods that allow for the reconstruction of both induced and remanent magnetization. The latter is particularly important, as remanent magnetization preserves the paleomagnetic signature acquired during rock formation, thereby providing critical insights into the region’s tectonic and structural evolution.

The following sections present the theoretical foundations of these inversion methodologies and demonstrate their effectiveness in delineating prospective mineralized zones within the Mpatasie concession.

2. Induced Polarization Effect in the Airborne EM Data

Interest in incorporating induced polarization (IP) effects into airborne electromagnetic (AEM) data interpretation has been steadily increasing. Traditionally, this has been approached using a 1D model, where the subsurface is assumed to consist of horizontal layers at each transmitter–receiver location. The full survey line is then constructed by piecing together and interpolating these individual 1D models. However, this method shares the same drawbacks as conventional 1D conductivity inversion, namely, it can produce misleading results and misrepresent the actual location of 3D targets. Furthermore, the inline field component, which has been shown to significantly reduce ambiguity and enhance resolution, cannot be used effectively within the 1D framework.

To address these limitations, Cox et al. [

4,

5,

6] have developed a fast and robust 3D inversion technique for airborne EM data that accounts for both electromagnetic induction and IP effects–capturing the full physical behavior of EM responses. IP parameters are estimated using the Generalized Effective Medium Theory of IP (GEMTIP). This modeling and inversion framework employs a hybrid approach combining finite-difference (FD) and integral-equation (IE) methods. The FD technique is used to compute the anomalous electric field in the subsurface using the PARDISO direct solver. This solver enables decomposition of the left-hand side of the electric field equation, independent of the source, enabling the efficient computation of multiple right-hand sides. This approach is especially beneficial given the large number of transmitters and receivers in airborne surveys. After computing the anomalous field, the IE method is applied to determine the field values at the receiver locations.

We applied the developed methodology to the inversion of airborne EM data collected for mineral exploration at the Mpatasie Gold Project in Ghana’s Asankragwa Belt. We first conducted a separate inversion of EM data into a 3D electrical conductivity model. This model served as the starting point for the simultaneous inversion of AEM data into conductivity and chargeability models. We have demonstrated that a full 3D inversion of airborne EM data, accounting for both EM induction and IP effects, enhances the effectiveness of airborne geophysical methods in mineral exploration by providing additional information (chargeability) and improving the accuracy of recovered conductivity.

3. Simultaneous Inversion of the TMI Data into the Induced and Remanent Magnetizations

Zhdanov et al. [

10] and Jorgensen and Zhdanov [

11] introduced a novel methodology to invert magnetic field data for both induced and remanent magnetization models. Traditional magnetic inversion methods often assume that all magnetization is induced and aligned with the Earth’s present magnetic field. However, this assumption fails in many geological contexts, such as those with significant thermoremanent or chemical remanent magnetization. To address this, our approach simultaneously inverts for induced and remanent magnetization, allowing for a more accurate subsurface interpretation.

The total magnetization vector

M is expressed as follows:

where χ is the magnetic susceptibility,

H0 is the Earth’s inducing magnetic field vector,

R is the remanent magnetization vector.

The observed magnetic data,

d, are modeled using the forward operator

A as follows:

where

A is the magnetic forward modelling operator.

The inversion aims to recover both χ and

R by minimizing the following parametric functional:

where

α is a regularization parameter,

m is the 4

length vector formed by the magnetic susceptibility and three scalar components of remanent magnetization, (χ,

Rx,

Ry,

Rz), defined within

discretization cells of the inversion domain;

Rβ is the

length vector of the vector of the

β =

x,

y,

z.

The minimum support stabilizer,

(

m), ensures the production of a focused image of the inverse model. The misfit functional,

ϕ(

m), is specified by the least-squares norm of the difference between the weighted predicted and observed data,

is the data weighting matrix. We can also apply the model parameter weights to improve the depth resolution of the inversion, as discussed in [

12,

13].

The Gramian stabilizer,

is introduced as follows:

where (*,*) denotes the

inner product operation, and

is the magnitude of the remanent magnetization vector,

R:

Coefficients and determine the relative contributions of focusing and Gramian stabilizers in the parametric functional. The code automatically selects them to balance the contribution versus the misfit functional

This parametric functional is minimized iteratively using the re-weighted regularized conjugate gradient (RRCG) method [

13]. This algorithm is similar to the conventional regularized conjugate gradient (RCG) algorithm. However, the inversion is conducted in the space of the weighted model parameters. We refer interested readers to the book on inversion theory by Zhdanov [

13] for an in-depth explanation of the RRCG technique, which is now widely used in various geophysical applications. Constraints can include smoothness (Tikhonov regularization) or focusing depending on geological expectations.

This method is especially valuable in mineral exploration where remanent magnetization is strong, such as in altered mafic to ultramafic rocks. In gold exploration, magnetic lows coinciding with high chargeability often indicate zones of hydrothermal alteration and sulphide mineralization. This inverse relationship between magnetic susceptibility and gold grades was attributed to hydrothermal alteration processes, such as carbonatization, sericitization, silicification, chloritization, and sulphidation, which reduce the magnetic properties of the host rocks while enhancing their chargeability due to the introduction of sulphide minerals [

14]. By capturing both induced and remanent contributions, this method helps delineate such alteration halos and associated mineralized zones, providing better targeting capability for drill testing.

4. Three-Dimensional Inversion of AEM and TMI Data in the Mpatasie Area, Ghana

4.1. Geological and Geophysical Background

The Mpatasie Property is located within the Kumasi basin, a 70–100 km wide belt of folded metasedimentary rocks. This basin is fault-bounded to the southeast and northwest against volcanic rocks of the Ashanti and Sefwi belts, respectively. Sedimentary rocks of the Kumasi Basin consist mostly of weakly to moderately metamorphosed shale, siltstone, sandstone, and wacke. These turbiditic sediments comprise a thick, monotonous sequence of folded, thinly to thickly interlayered shale and siltstone with local sections of volcaniclastic sediment.

Gold mineralization in the Mpatasie area mirrors that elsewhere in the Ashanti Belt. Mineralization is hosted by quartz—carbonate vein systems within shear zones and is closely associated with disseminated and vein-controlled sulfides. Pyrite and arsenopyrite are the dominant sulfides, with lesser pyrrhotite and chalcopyrite.

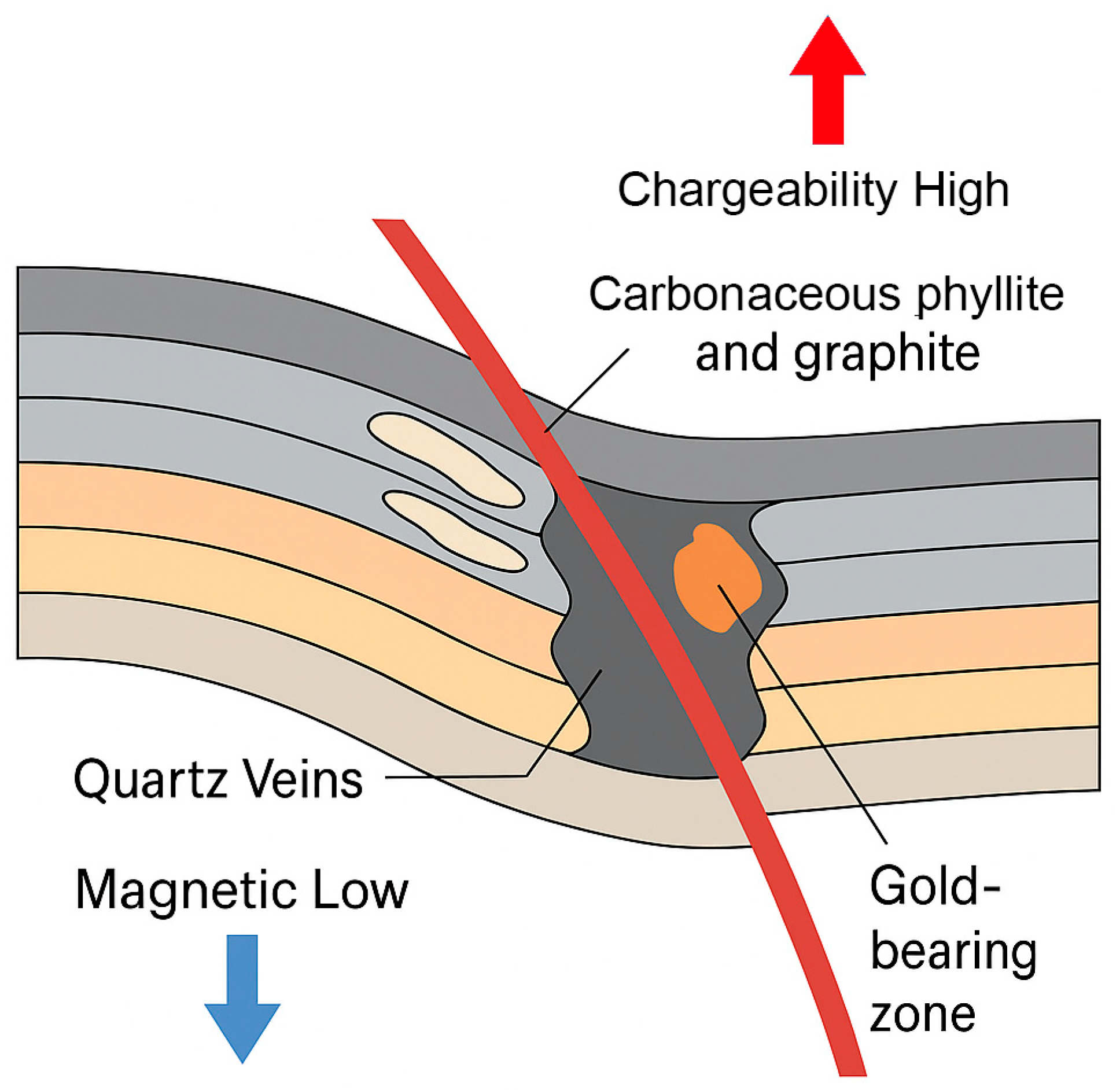

Alteration assemblages include sericite, carbonate, silica, and sulfides, with local chloritization. A key diagnostic feature is the destruction of primary magnetite within altered zones, leading to magnetic lows in geophysical surveys. The presence of carbonaceous phyllite and graphitic shears enhances chargeability responses, providing complementary geophysical indicators.

Figure 2 shows a conceptual model of shear-zone hosted gold mineralization, showing the prominent geophysical responses: magnetic lows and chargeability highs.

The gold-bearing quartz vein systems associated with Belt-margin structures and shear zones exhibit several common characteristics. These characteristics are also typical of the structurally hosted vein systems of the Asankrangwa Belt. Among the properties which may be visible by geophysics include:

Disseminated sulfides in the wall rocks (IP);

Gold mineralization is associated with carbonaceous phyllite and secondary graphite (elevated conductivity);

Accessory sulphide minerals include pyrite, chalcopyrite and sphalerite (elevated conductivity and IP);

Silicification may be strong locally (enhanced resistivity).

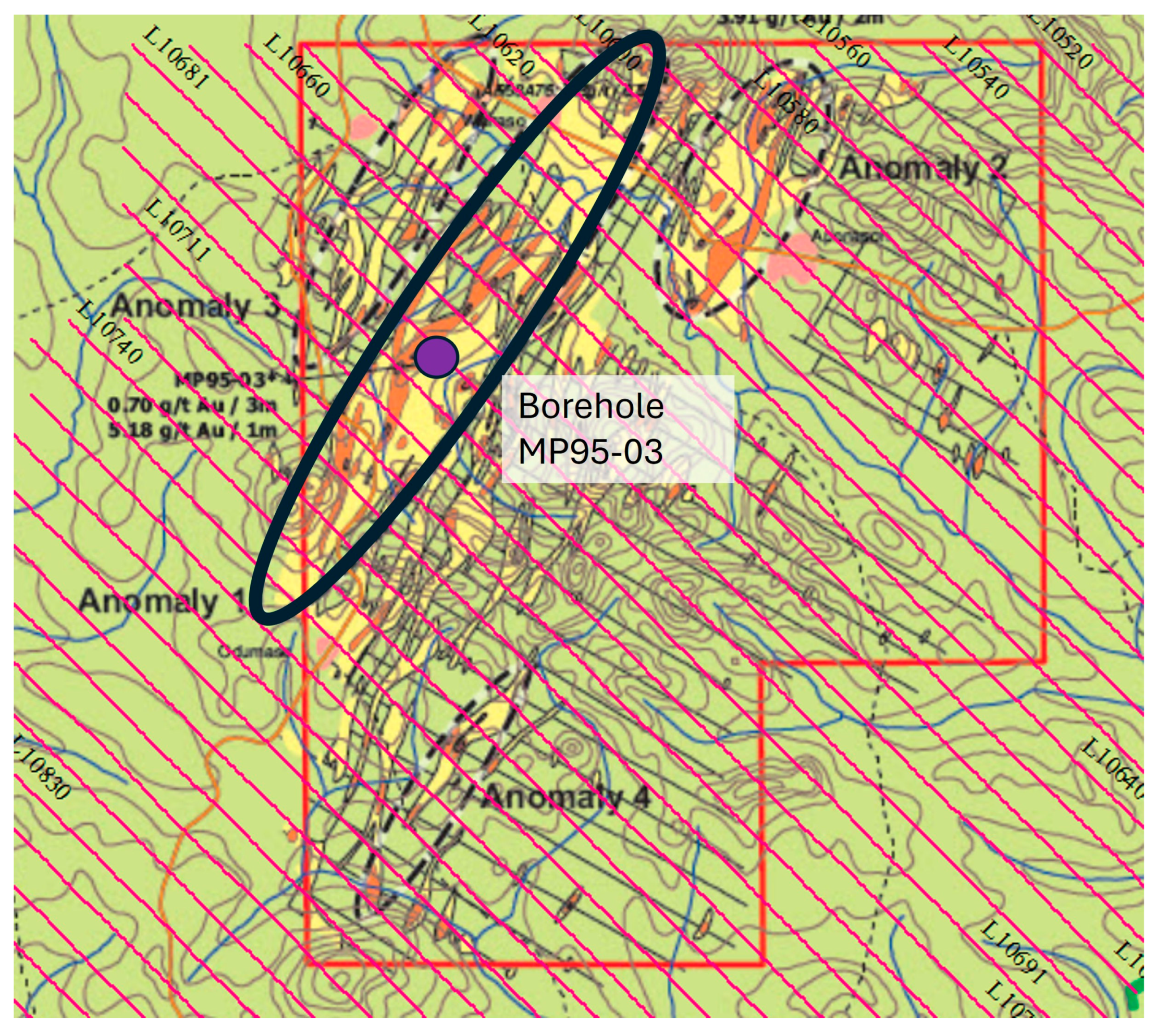

A trenching program has been completed to test the surface expression of gold mineralization identified in the historic soil survey. Five samples at the Mpatasie project returned values above 1 ppm. Drillhole MP95-03 collared there returned 1 m @ 5.18 g/t Au and 4 m of elevated gold, confirming the trench result at depth. Geochemical data were also collected in this area.

Figure 3 shows the location of borehole MP95-03, and geochemical data. The main anomaly of interest from geochemistry is shown in the heavy black outline. The borehole is closest to L10681.

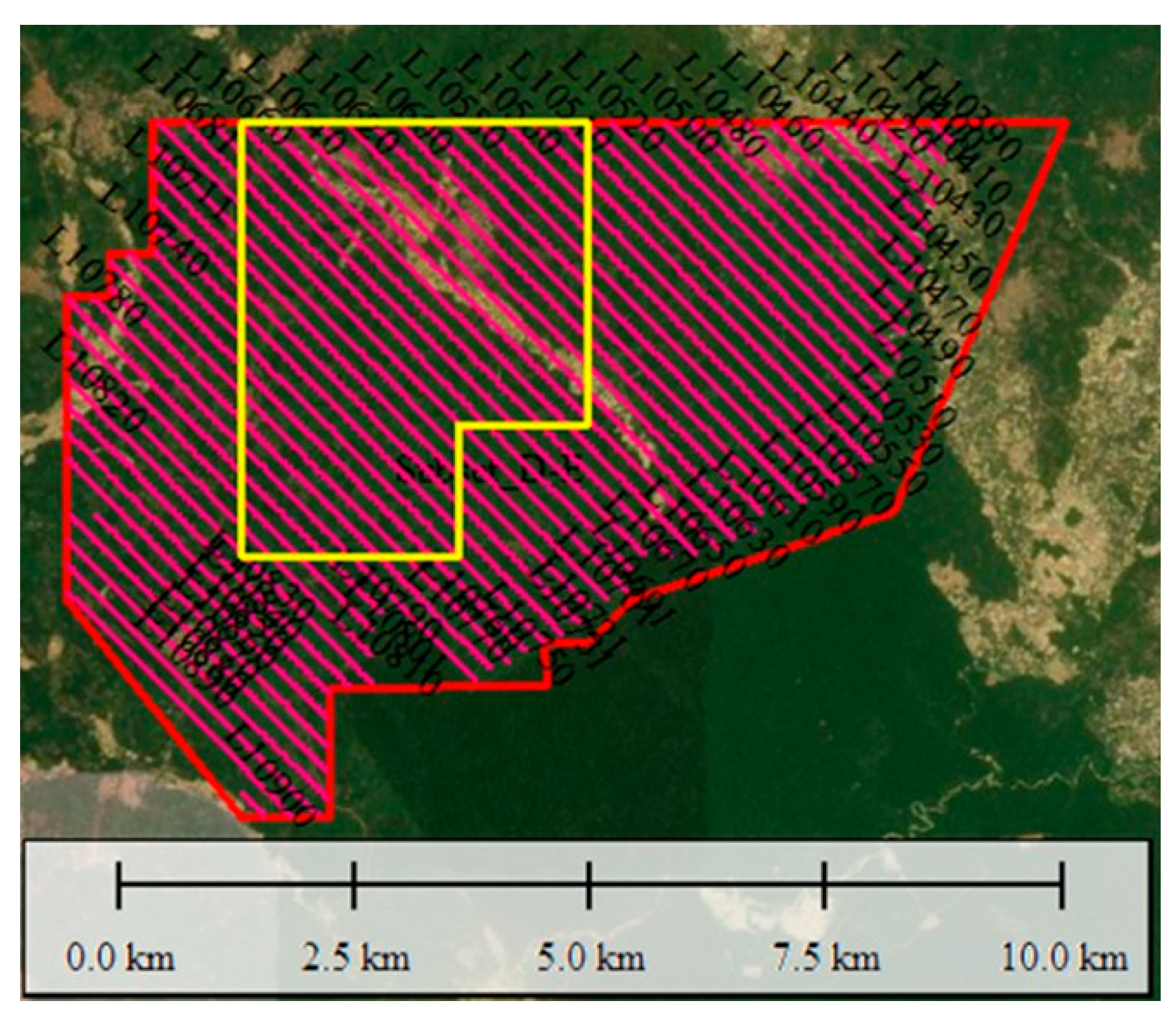

High-resolution airborne geophysical surveys were flown across the Mpatasie concession by Geotech, providing Total Magnetic Intensity (TMI) and airborne EM datasets. Survey parameters included a nominal line spacing of 200 m, tie lines at 2 km, and a mean terrain clearance of 80 m. The flight lines and primary area of interest are shown in

Figure 4. The transmitter was 425,000 NIA, and both inline and vertical dB/dt components were measured. The nominal terrain clearance was 41 m. The vertical component was processed to 27 channels from 80 µs to 8.5 ms. The inline component started at 213 µs and extended to 8.5 ms.

The AEM and TMI data have been analyzed and inverted in 3D to provide the subsurface images of conductivity, chargeability and magnetization of the rock formations.

4.2. AEM Inversion Results

The inversion was performed on a grid of 50 m × 50 m horizontally. The vertical direction was discretized in 16 cells, logarithmically spaced from 5 m at the surface to 90 m thickness at depth. The minimum norm stabilizer plus a second derivative stabilizer in the crossline direction was used. The starting and reference models were 1D inversion results. The time constant and relaxation parameter were left fixed from the 1D inversion, and just the chargeability and conductivity were allowed to vary in the 3D inversion.

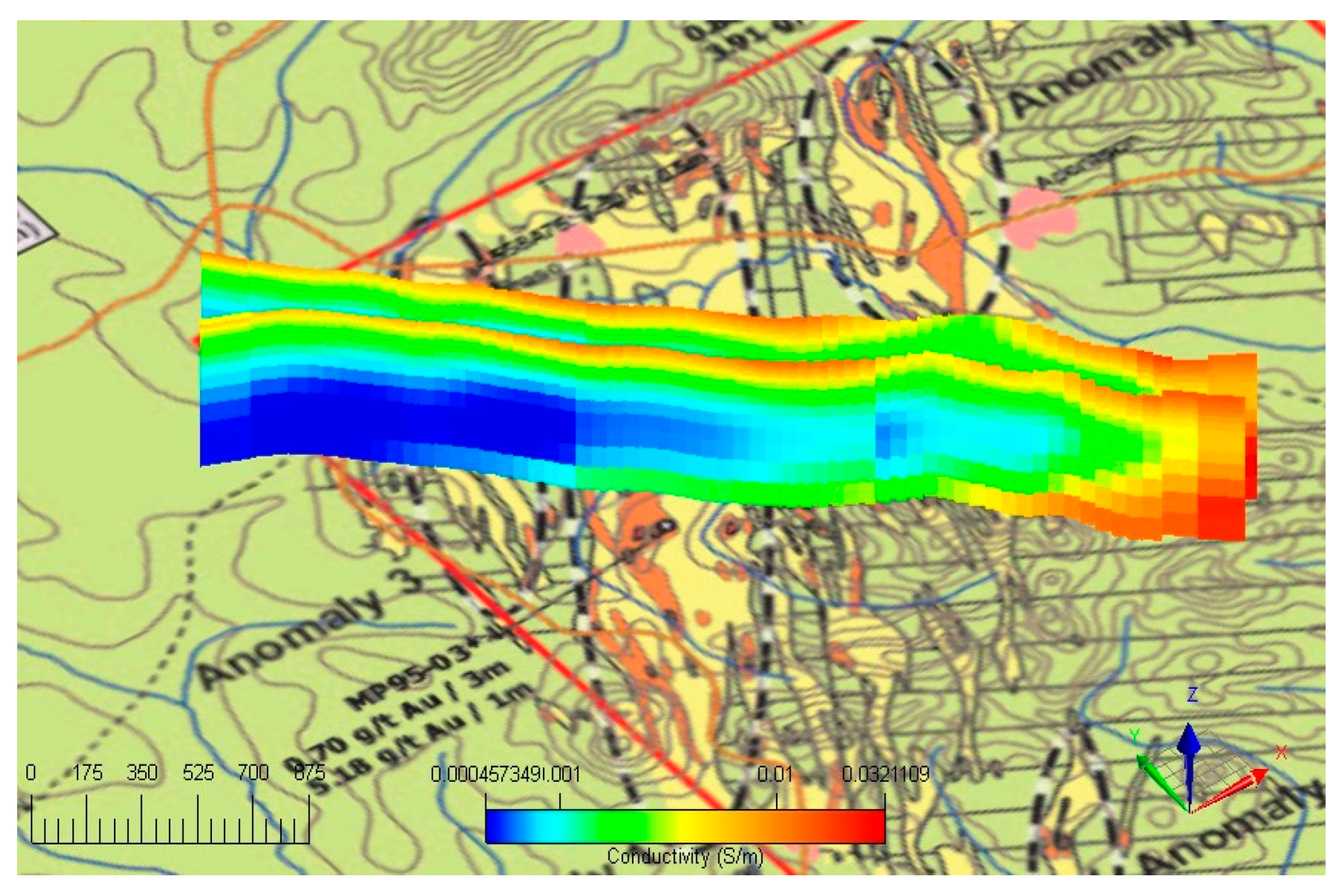

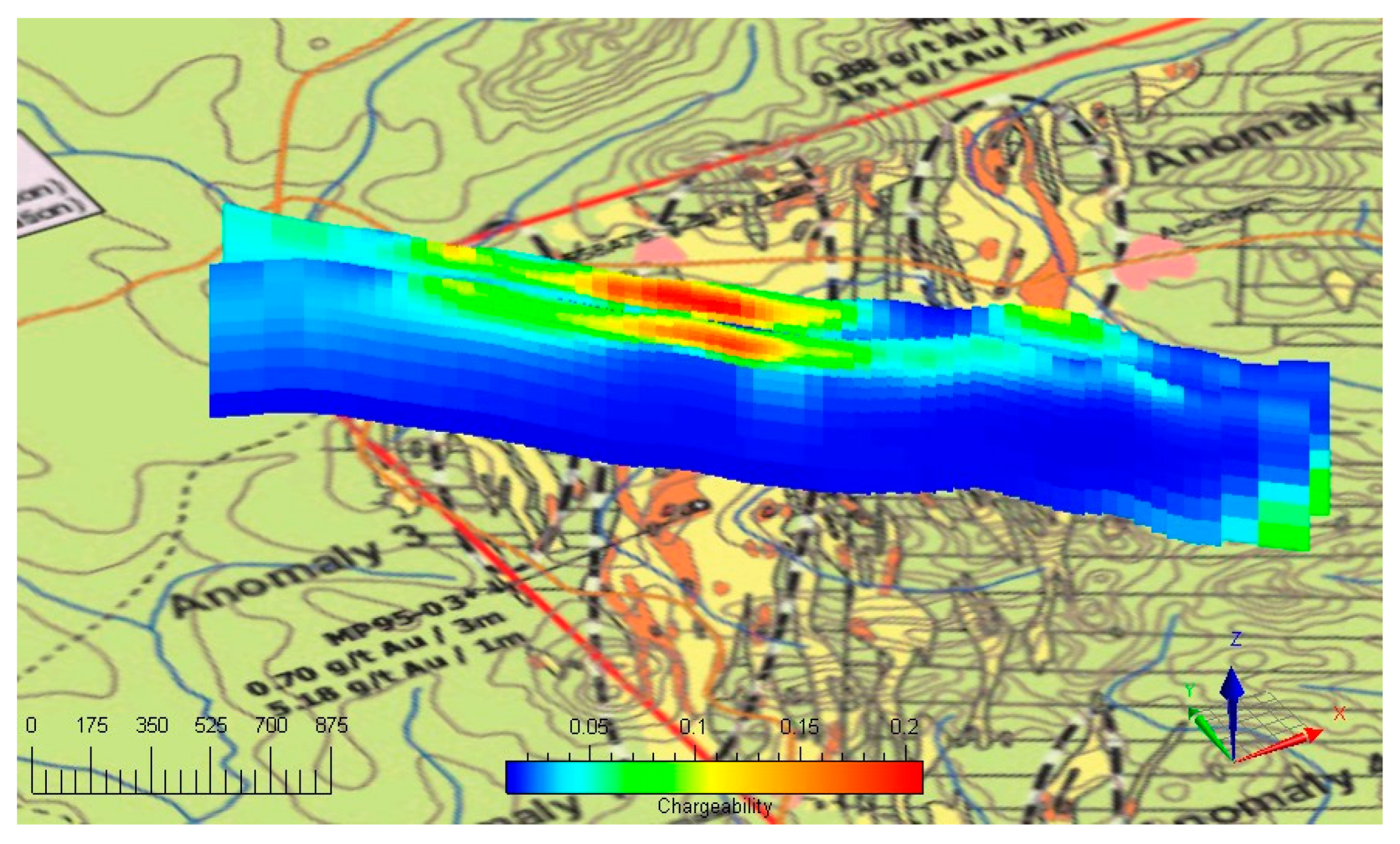

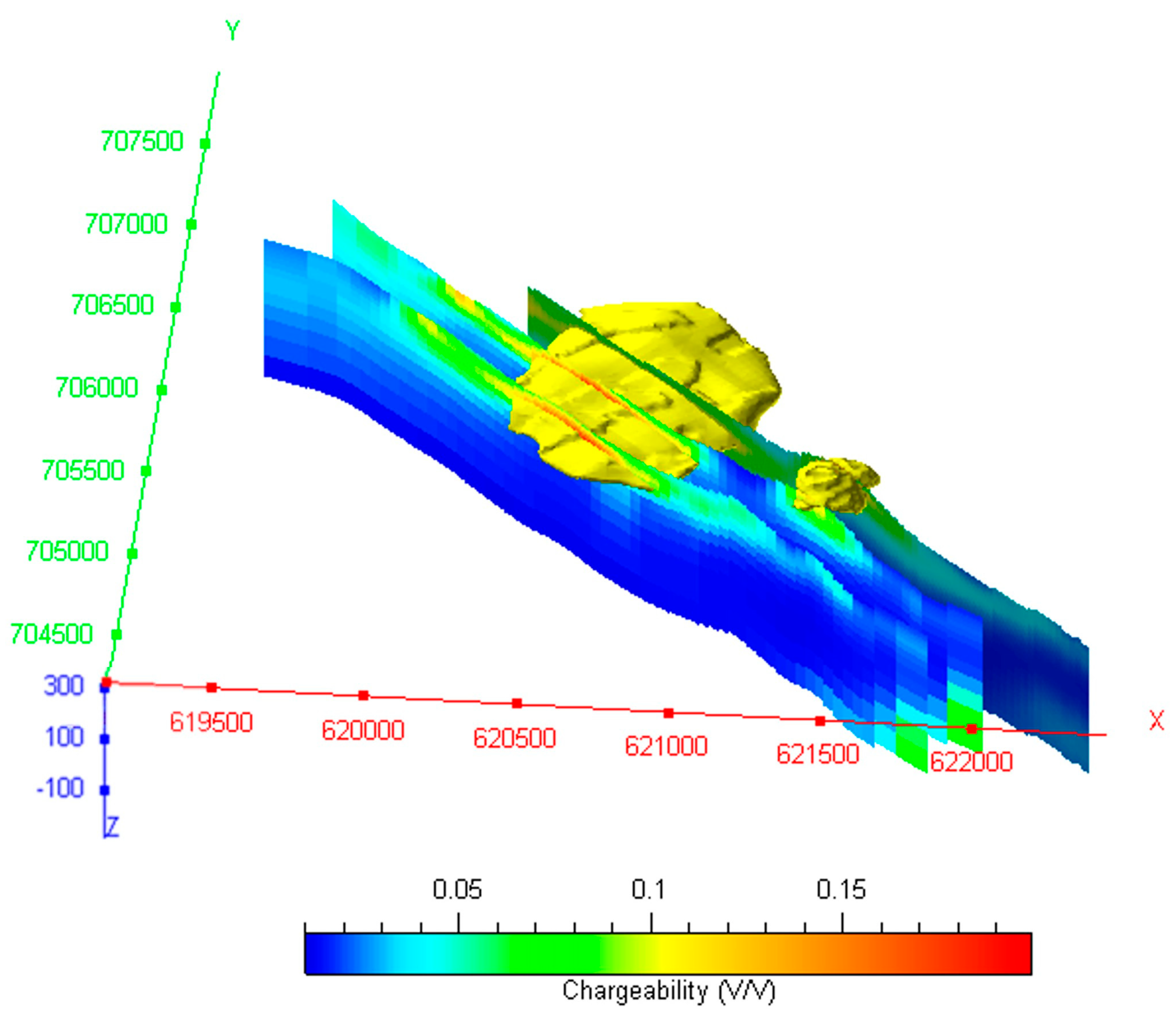

A perspective view of conductivity is shown in

Figure 5. The conductivity image is relatively uniform laterally, with conductive overburden imaged throughout, and an increase in conductivity is shown at the right side of the figure due to a graphitic horizon. The chargeability (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) shows a much different picture, with elevated chargeability along the strike and corresponding to the geochemical gold anomaly.

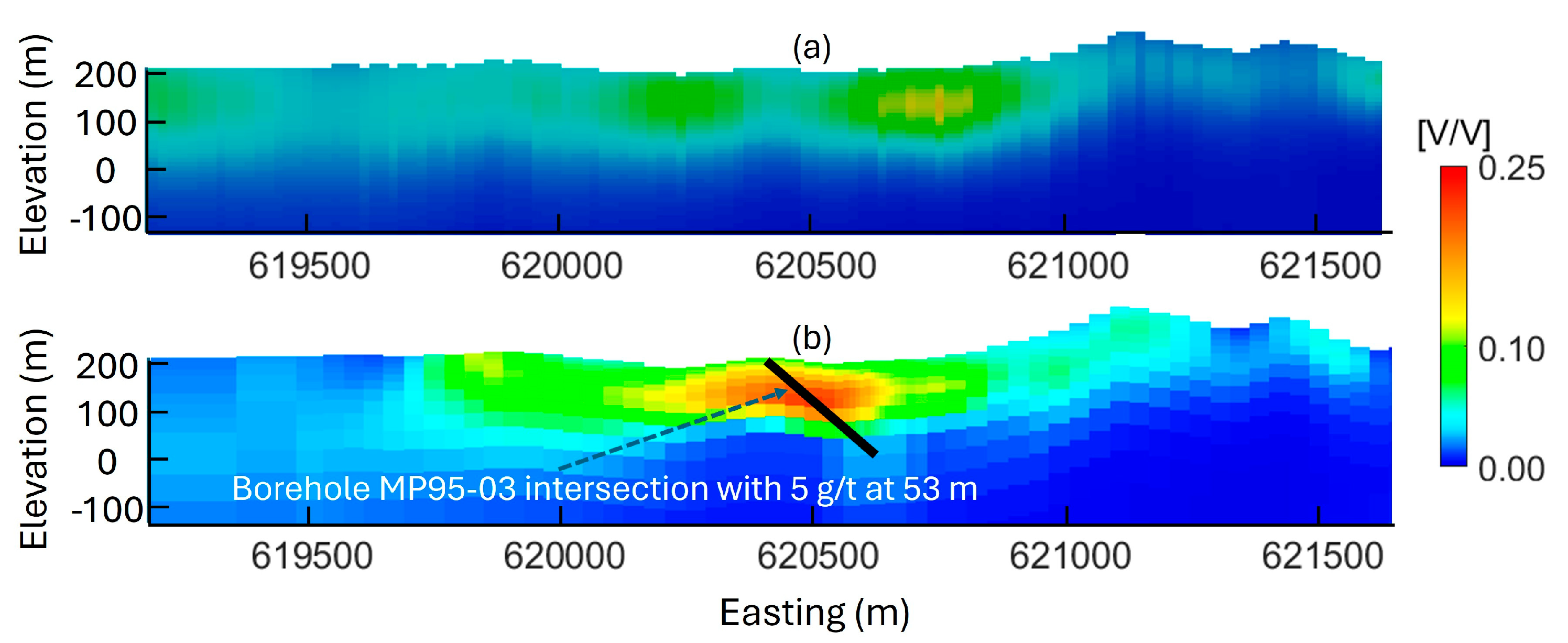

Figure 8 shows a profile of 1D inversion results in the top panel and 3D inversion results in the bottom panel. The red line in the 3D inversion image indicates the approximate location of borehole MP95-03, and the arrow points to the intersection of the borehole with 1 m of 5.3 g/t gold. The elevated induced polarization corresponds well with the borehole and geochemical data, and it extends along strike for several lines. Note that the result of 1D inversion completely missed this chargeability anomaly associated with the gold mineralization.

4.3. TMI Inversion Results

Magnetic data underwent standard preprocessing: diurnal correction, removal of the International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF), and micro-leveling. The gridded TMI dataset provided the basis for further filtering and inversion.

A bandpass filter was applied using a two-dimensional Fourier transform. Wavelengths corresponding to depths greater than ~2 km were attenuated. This enhanced the shallow features of exploration significance while suppressing the regional background and deep sources. The original TMI data are shown in

Figure 9. The residual anomalous magnetic intensity (AMI) data we inverted are shown in

Figure 10.

The filtered magnetic dataset was inverted using the inversion algorithm discussed above. The model discretization was 20 m inline, 80 m crossline, and 18 vertical layers ranging from 10 m to 400 m thickness. A homogeneous half-space was employed as the starting model. Adaptive focusing regularization [

13] was used. Once the data misfit reached 20% of the estimated noise, the inversion applied a focusing term to sharpen anomaly boundaries and emphasize compact structures. Final misfit achieved was ~7%.

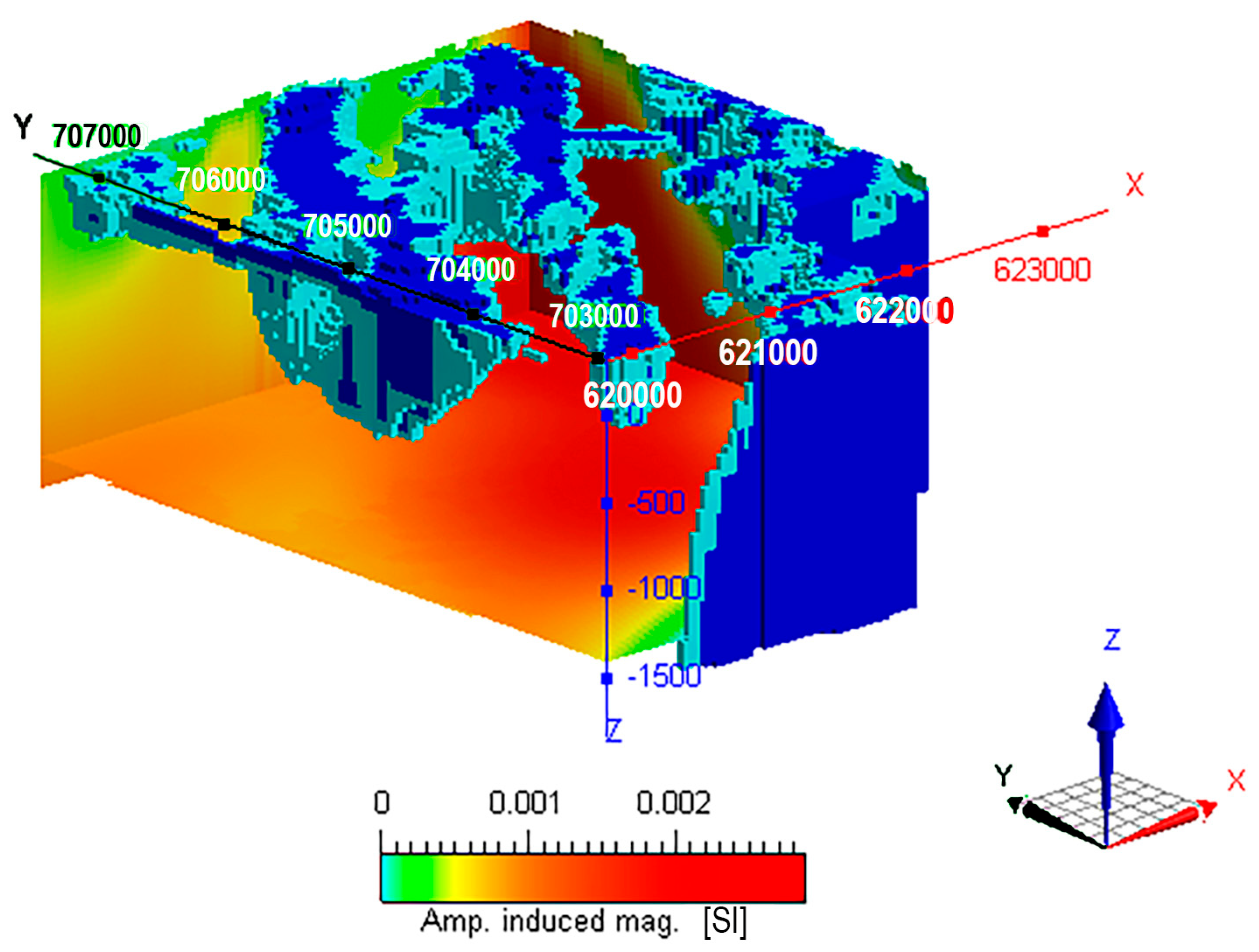

The inversion revealed a pronounced induced magnetization low coincident with mapped shear structures in the concession. This anomaly is interpreted as an alteration zone where hydrothermal fluids destroy magnetite, and it spatially correlates with known gold mineralization.

Figure 11 displays cross sections of the recovered induced magnetization, with cooler colors representing zones of very low induced magnetization. Notably, the inversion recovers a pronounced low in this region despite a coincident high observed in the original Total Magnetic Intensity (TMI) data.

This discrepancy highlights the value of our approach, which can resolve true magnetization directions and magnitudes even when the TMI response may be dominated by remanent effects or complex overlapping sources.

Figure 12 shows isobodies of low induced magnetization below 0.00001 A/m.

4.4. Comparison of Inverse Chargeability and Magnetization Models

Comparison of the results of both AEM and TMI data inversion demonstrates that inverse chargeability models display chargeability highs coincident with magnetization lows during inversion.

Drillhole MP95-03 tested one such anomaly and intersected 1 m @ 5.3 g/t Au, confirming the geophysical interpretation. The chargeability anomalies are shallower and thinner than their magnetic counterparts, consistent with the limited penetration of airborne EM.

Figure 13 presents the inverted chargeability model from the same section, superimposed over the induced magnetization cross sections from

Figure 12. A distinct chargeability high is observed within the red-circled region, directly coinciding with the magnetization low. This spatial correlation is interpreted as a potential gold-bearing zone within the Mpatasie concession, where mineralization is often associated with sulphide-rich, chargeable alteration halos that produce low magnetic responses due to magnetite destruction. Drillhole MP95-03 confirmed 1 m of 5.3 g/t gold in the chargeable anomaly [

6]. It is also evident that the depth extent of the magnetic low surpasses that of the chargeable anomaly. This difference in vertical extent is a combination of the limited penetration depth of the airborne electromagnetic (AEM) method used for chargeability inversion, which is typically sensitive only to the upper few hundred meters, and the poor depth resolution of potential field methods.

4.5. Remanent Magnetization and Basement Structure

One of the critical challenges in interpreting the magnetic data at Mpatasie is the influence of remanent magnetization. Rocks within the basement granitoid and volcaniclastic units often retain a strong natural remanent magnetization (NRM), acquired during cooling or alteration events. This remanence can produce magnetic anomalies that are discordant with the present-day inducing field, leading to apparent highs where the true susceptibility is low, or vice versa.

To evaluate remanent effects, the developed technique of inversion into induced and remanent magnetizations was applied. Unlike scalar susceptibility inversions, which assume magnetization parallel to the Earth’s field, the novel inversion method solves for both the magnitude and direction of remanent magnetization. Results revealed significant remanence within basement units underlying the turbiditic sequence.

The recovered remanent magnetization directions differ by up to 60° from the present inducing field. Importantly, this explains why some anomalies in the raw TMI data appeared as highs yet inverted to lows when remanence was accounted for.

Basement structures were clearly imaged: north-northeast-trending granitoid plutons and volcaniclastic dike swarms were resolved at depths >1.5 km. These basement features exert strong control over the localization of shear zones in the overlying sediments and, by extension, indirectly over mineralization.

The ability to distinguish remanent anomalies from induced responses was critical in isolating genuine alteration-related lows from basement-related artifacts. This step greatly improved confidence in exploration targeting.

Figure 14 presents a 3D view of remanent magnetization. It shows the likely basement structure of the Mpatasie concession in warm colors. The green area with the blue peak shows an alteration-related low at a depth of over 1 km. If a deep penetrating ground IP survey is carried out and it defines an associated chargeability high, this would be a prime target for drilling.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

We have developed and implemented a comprehensive methodology for the three-dimensional inversion of large-scale airborne electromagnetic (AEM) survey data that simultaneously recovers both electrical conductivity and chargeability. This workflow offers distinct advantages over conventional one-dimensional (1D) layered-earth inversion approaches. Whereas 1D inversion assumes laterally homogeneous, horizontally stratified geology, the 3D inversion rigorously incorporates the full geometric complexity of the subsurface and inherently accounts for three-dimensional variations in structure. As a result, 3D inversion can accurately represent dipping strata, intrusive bodies, faults, and other heterogeneities that cannot be resolved under the assumptions of the layered-earth model. Additionally, the 3D implementation makes full use of all available airborne EM field components, including horizontal components that are commonly excluded in 1D inversion when transmitter–receiver offsets are small.

A key element of the presented methodology is the explicit treatment of induced polarization (IP) effects in airborne EM data. Neglecting IP responses can lead to significant misinterpretation of conductive bodies, particularly in mineralized systems where disseminated sulfides contribute strongly to chargeability. By employing the generalized effective-medium theory (GEMTIP), the inversion simultaneously recovers 3D conductivity and chargeability distributions that are physically interpretable and geologically meaningful. The use of a moving sensitivity domain further enables the inversion of large AEM datasets without loss of spatial resolution or the need for artificial survey partitioning.

In parallel, the newly developed vector magnetic inversion recovers both induced and remanent magnetization. This approach successfully resolves a pronounced low in the induced magnetization component in an area where traditional susceptibility inversion would have erroneously suggested a high response. This result demonstrates the limitations of scalar susceptibility inversion in terrains affected by strong remanence and highlights the necessity of vector magnetization imaging to achieve accurate geological interpretations.

Application of the integrated 3D AEM and vector magnetic inversion workflow to the Mpatasie area in central Ghana yielded results that show strong spatial correlation with known gold occurrences, geochemical anomalies, and mapped geological structures. The combined interpretation supports the following exploration model for the region:

Regional shear zones provide first-order structural controls on gold mineralization;

Magnetization lows delineate zones of hydrothermal alteration;

Elevated chargeability values identify sulfide-rich halos associated with mineralization;

Simultaneous inversion of the TMI data into the induced and remanent magnetization models reveals remanence effects and defines basement structural controls;

Drillhole data confirm that coincident magnetization lows and chargeability highs correspond to gold-bearing sulfide zones.

These findings collectively support continued exploration and follow-up drilling, particularly along strike extensions where structural conduits intersect coincident magnetic and chargeability anomalies. More broadly, the study underscores the importance of conducting 3D inversion of AEM data to recover both conductivity and chargeability, as well as accounting for remanent magnetization in the TMI data acquired in geologically complex terranes. The integrated approach provides a robust, scalable framework for mineral exploration in structurally heterogeneous, magnetically complex environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.Z.; Methodology, M.S.Z., L.H.C. and M.J.; Software, L.H.C. and M.J.; Validation, D.H.P.; Investigation, M.S.Z., L.H.C. and M.J.; Resources, D.H.P.; Data curation, D.H.P.; Writing—original draft, M.S.Z.; Writing—review and editing, M.S.Z.; Visualization, L.H.C. and M.J.; Supervision, M.S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

These data are proprietary and commercially held, hence they are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Consortium for Electromagnetic Modeling and Inversion (CEMI) at the University of Utah and TechnoImaging for their support of this research project. We thank Emmanuel Ababio, the Chairman & CEO of GoldLine Mining Ghana Limited, who was very instrumental in making the results publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

Leif H. Cox was employed by TechnoImaging, and Douglas H. Pitcher was employed by GoldLine Mining Ghana Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Viezzoli, A.; Kaminski, V. Airborne IP: Examples from the Mount Milligan Deposit, Canada, and the Amakinskaya Kimberlite Pipe, Russia. Explor. Geophys. 2016, 47, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto Junior, M.A.; Fiandaca, G.; Maurya, P.K.; Christiansen, A.V.; Porsani, J.L.; Auken, E. AEMIP robust inversion using maximum phase angle Cole–Cole model re-parameterisation applied for HTEM survey over Lamego gold mine, Quadrilátero Ferrífero, MG, Brazil. Explor. Geophys. 2020, 51, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnae, J.; Hine, K. Comparing induced polarization responses from airborne inductive and galvanic ground systems: Tasmania. Geophysics 2016, 81, E471–E479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.H.; Zhdanov, M.S.; Pitcher, D.H.; Niemi, J. Three-dimensional inversion of induced polarization effects in airborne time domain electromagnetic data using the GEMTIP model. Minerals 2023, 13, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.H.; Zhdanov, M.S.; Prikhodko, A. Inversion for 2D Conductivity and Chargeability Models Using EM Data Acquired by the New Airborne TargetEM System in Ontario, Canada. Minerals 2024, 14, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.H.; Zhdanov, M.S.; Pitcher, D.H. Three-Dimensional Inversion of AEM Data for Conductivity and Chargeability in the Mpatasie Area, Ghana. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Geophysics for Mineral Exploration and Mining, Naples, Italy, 7–11 September 2025; Volume 2025, pp. 1–5. Available online: https://www.earthdoc.org/content/papers/10.3997/2214-4609.202520065 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Lelièvre, P.G.; Oldenburg, D.W. A 3D total magnetization inversion applicable when significant, complicated remanence is present. Geophysics 2009, 74, L21–L30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shearer, S.E.; Haney, M.M.; Dannemiller, N. Comprehensive approaches to 3D inversion of magnetic data affected by remanent magnetization. Geophysics 2010, 75, L1–L11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hu, X.; Fedi, M.; Ou, Y.; Baniamerian, J.; Zuo, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, R. Three-dimensional inversion of magnetic data in the simultaneous presence of significant remanent magnetization and self-demagnetization: Example from Daye iron-ore deposit, Hubei province, China. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 215, 614–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov, M.S.; Jorgensen, M.; Keating, J.J. Revealing the Hidden Paleomagnetic Information from the Airborne Total Magnetic Intensity (TMI) data. First Break 2024, 42, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, M.; Zhdanov, M.S. Simultaneous inversion of magnetic data into induced and remanent magnetizations. In Proceedings of the 85th EAGE Annual Conference & Exhibition, Oslo, Norway, 10–13 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov, M.S. Geophysical Inverse Theory and Regularization Problems; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhdanov, M.S. Inverse Theory and Application in Geophysics; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Takyi-Kyeremeh, K.; Wemegah, D.D.; Preko, K.; Menyeh, A. Integrated geophysical study of the Subika Gold Deposit in the Sefwi Belt, Ghana. Cogent Geosci. 2019, 5, 1585406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Regional geologic map showing the location of the study area in red, situated between the Sefwi gold belt to the west and the Ashanti gold belt to the east.

Figure 1.

Regional geologic map showing the location of the study area in red, situated between the Sefwi gold belt to the west and the Ashanti gold belt to the east.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of shear-zone hosted mineralization, showing geophysical responses (mag lows, chargeability highs).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of shear-zone hosted mineralization, showing geophysical responses (mag lows, chargeability highs).

Figure 3.

The schematic geochemistry map. VTEM flight lines are shown in magenta. Bold purple dot indicates the location of borehole MP95-03; a red box outlines the main Mpatasie area. The geochemistry shows gold values of 51–200 ppb in orange and 10–50 ppb in yellow.

Figure 3.

The schematic geochemistry map. VTEM flight lines are shown in magenta. Bold purple dot indicates the location of borehole MP95-03; a red box outlines the main Mpatasie area. The geochemistry shows gold values of 51–200 ppb in orange and 10–50 ppb in yellow.

Figure 4.

VTEM flight lines for the study area and the Mpatasie area of interest. The flight lines shown here total 237 line-km.

Figure 4.

VTEM flight lines for the study area and the Mpatasie area of interest. The flight lines shown here total 237 line-km.

Figure 5.

Fence diagram of conductivity along lines 10,681 and 10,670. The map shows the geochemical anomalies. The color scale varies logarithmically from 0.0004 S/m (blue) to 0.03 S/m (red).

Figure 5.

Fence diagram of conductivity along lines 10,681 and 10,670. The map shows the geochemical anomalies. The color scale varies logarithmically from 0.0004 S/m (blue) to 0.03 S/m (red).

Figure 6.

Fence diagram of chargeability along lines 10,681 and 10,670. The map shows the geochemical anomalies. The color scale varies logarithmically from 0.01 V/V (blue) to 0.2 V/V (red).

Figure 6.

Fence diagram of chargeability along lines 10,681 and 10,670. The map shows the geochemical anomalies. The color scale varies logarithmically from 0.01 V/V (blue) to 0.2 V/V (red).

Figure 7.

Fence diagram of chargeability along lines 10,681 and 10,670. The yellow isosurface is shown at 0.1 V/V.

Figure 7.

Fence diagram of chargeability along lines 10,681 and 10,670. The yellow isosurface is shown at 0.1 V/V.

Figure 8.

Cross sections of chargeability extracted from the inversion results. The top panel (a) shows 1D inversion results, and the bottom panel (b) presents 3D inversion results. The bold black line shows the approximate location of borehole MP95-03. The 1D inversion (top panel) fails to capture the chargeability anomaly associated with the gold mineralization.

Figure 8.

Cross sections of chargeability extracted from the inversion results. The top panel (a) shows 1D inversion results, and the bottom panel (b) presents 3D inversion results. The bold black line shows the approximate location of borehole MP95-03. The 1D inversion (top panel) fails to capture the chargeability anomaly associated with the gold mineralization.

Figure 9.

Total magnetic intensity (TMI) data over the Mpatasie concession before filtering. The Mpatasie concession is shown by the red box.

Figure 9.

Total magnetic intensity (TMI) data over the Mpatasie concession before filtering. The Mpatasie concession is shown by the red box.

Figure 10.

Residual anomalous magnetic intensity (AMI) data over the Mpatasie concession. These data were used in the inversion. The Mpatasie concession is shown by the red box.

Figure 10.

Residual anomalous magnetic intensity (AMI) data over the Mpatasie concession. These data were used in the inversion. The Mpatasie concession is shown by the red box.

Figure 11.

3D view of the amplitude of the induced magnetization normalized by the amplitude of the inducing Earth’s magnetic field. Dark blue colors show extremely low induced magnetization, which is indicative of gold mineralization in the Mpatasie concession. The red circle indicates the area of interest.

Figure 11.

3D view of the amplitude of the induced magnetization normalized by the amplitude of the inducing Earth’s magnetic field. Dark blue colors show extremely low induced magnetization, which is indicative of gold mineralization in the Mpatasie concession. The red circle indicates the area of interest.

Figure 12.

3D isobodies of low induced magnetization indicated by dark blue color corresponding to potential magnetite destruction zones.

Figure 12.

3D isobodies of low induced magnetization indicated by dark blue color corresponding to potential magnetite destruction zones.

Figure 13.

A vertical section of the 3D chargeability model is shown superimposed over the same induced magnetization cross section as in

Figure 11. Warm colors in the vertical section show high chargeability, which is indicative of gold mineralization in the Mpatasie concession. The red circle indicates the area of interest. The short black line in the chargeability vertical section shows drillhole MP95-03.

Figure 13.

A vertical section of the 3D chargeability model is shown superimposed over the same induced magnetization cross section as in

Figure 11. Warm colors in the vertical section show high chargeability, which is indicative of gold mineralization in the Mpatasie concession. The red circle indicates the area of interest. The short black line in the chargeability vertical section shows drillhole MP95-03.

Figure 14.

3D view of the amplitude of the remanent magnetization normalized by the amplitude of the inducing Earth’s magnetic field. The warm colors represent unaltered basement rocks.

Figure 14.

3D view of the amplitude of the remanent magnetization normalized by the amplitude of the inducing Earth’s magnetic field. The warm colors represent unaltered basement rocks.

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).