Garnet Geochemistry of the Tietangdong Breccia Pipe, Yixingzhai Gold Deposit, North China Craton: Constraints on Hydrothermal Fluid Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Regional Geology

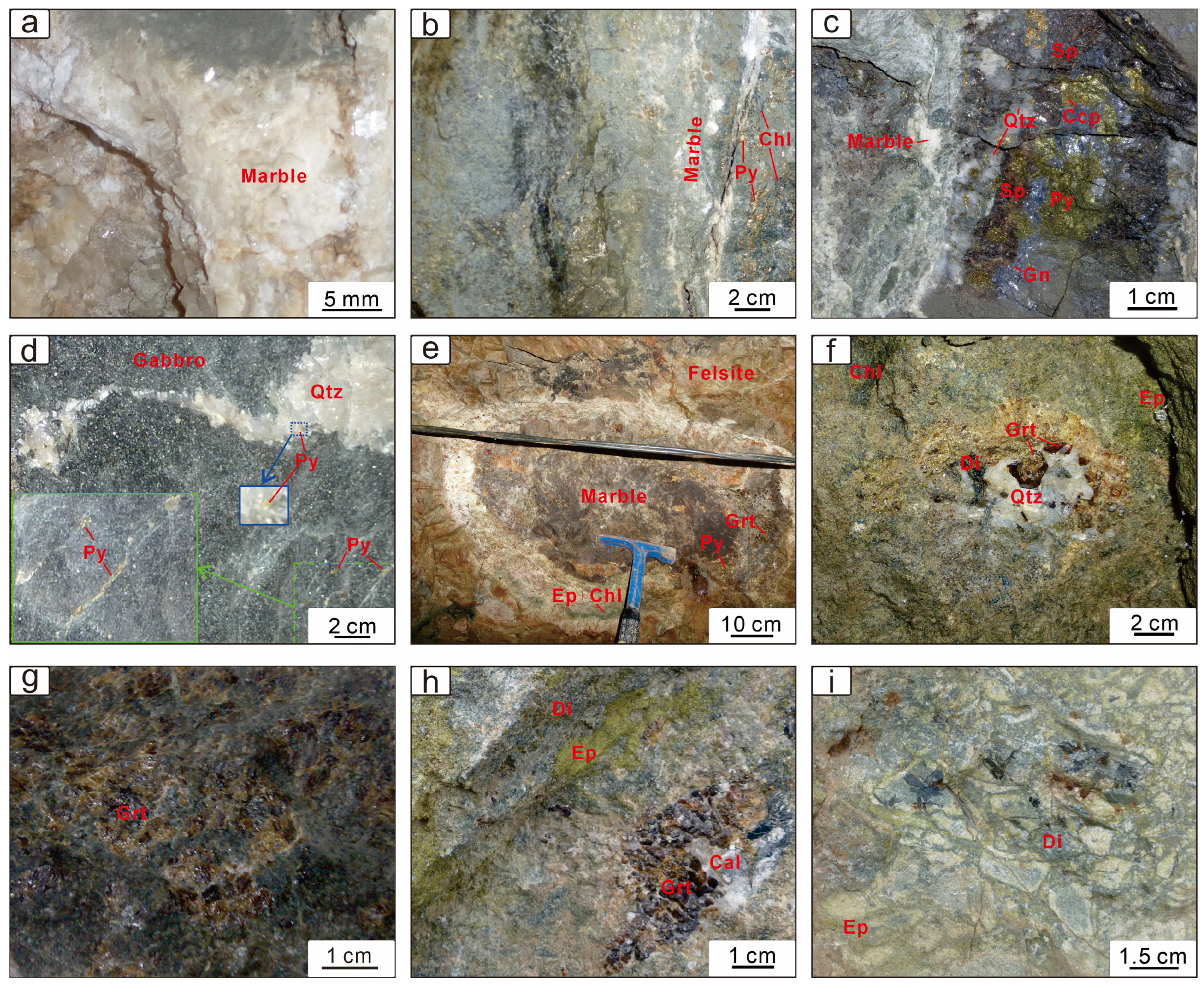

3. Deposit Geology

4. Tietangdong Cryptoexplosive Breccia Pipe

5. Samples and Analytical Methods

6. Results

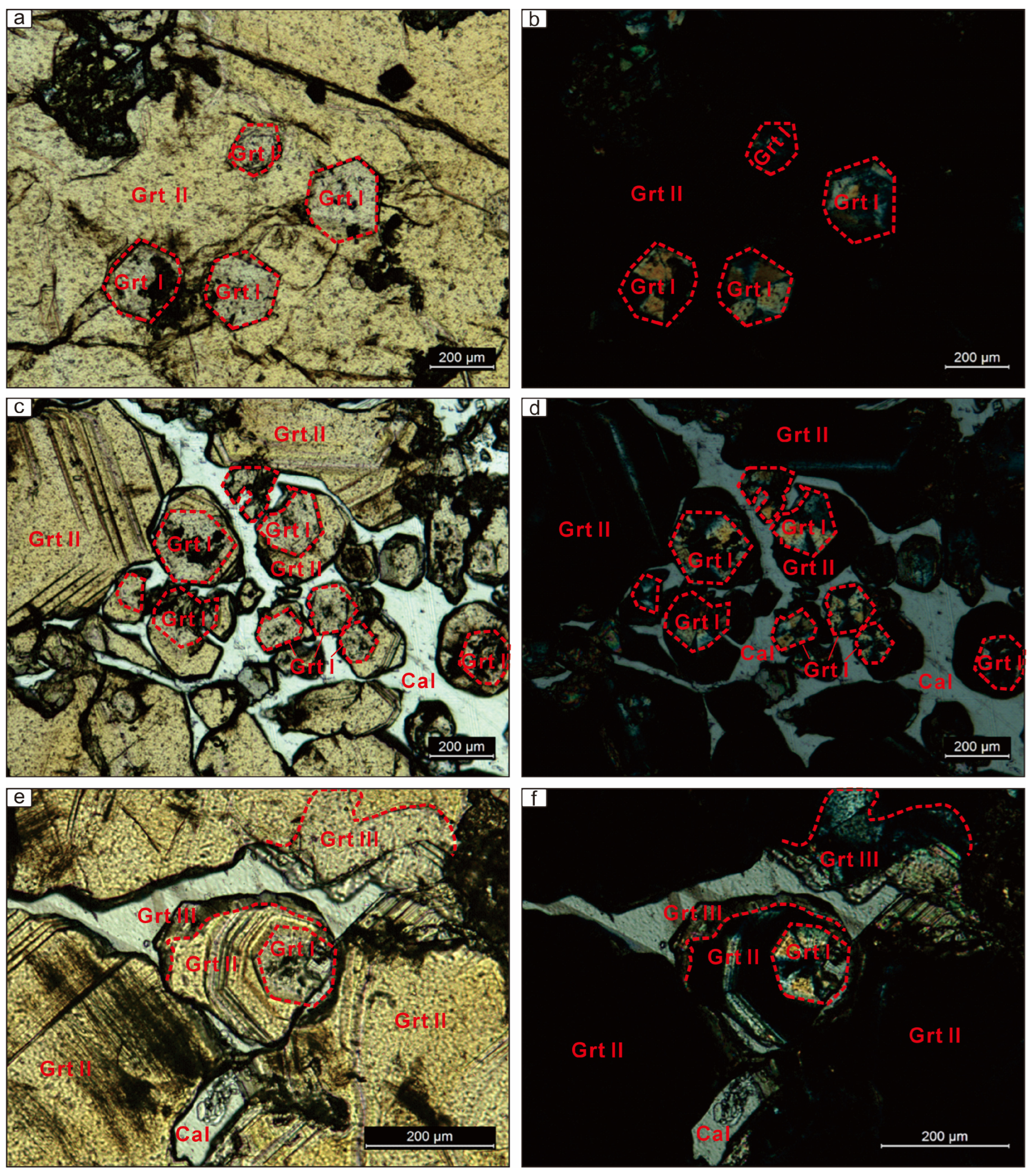

6.1. Garnet Petrography

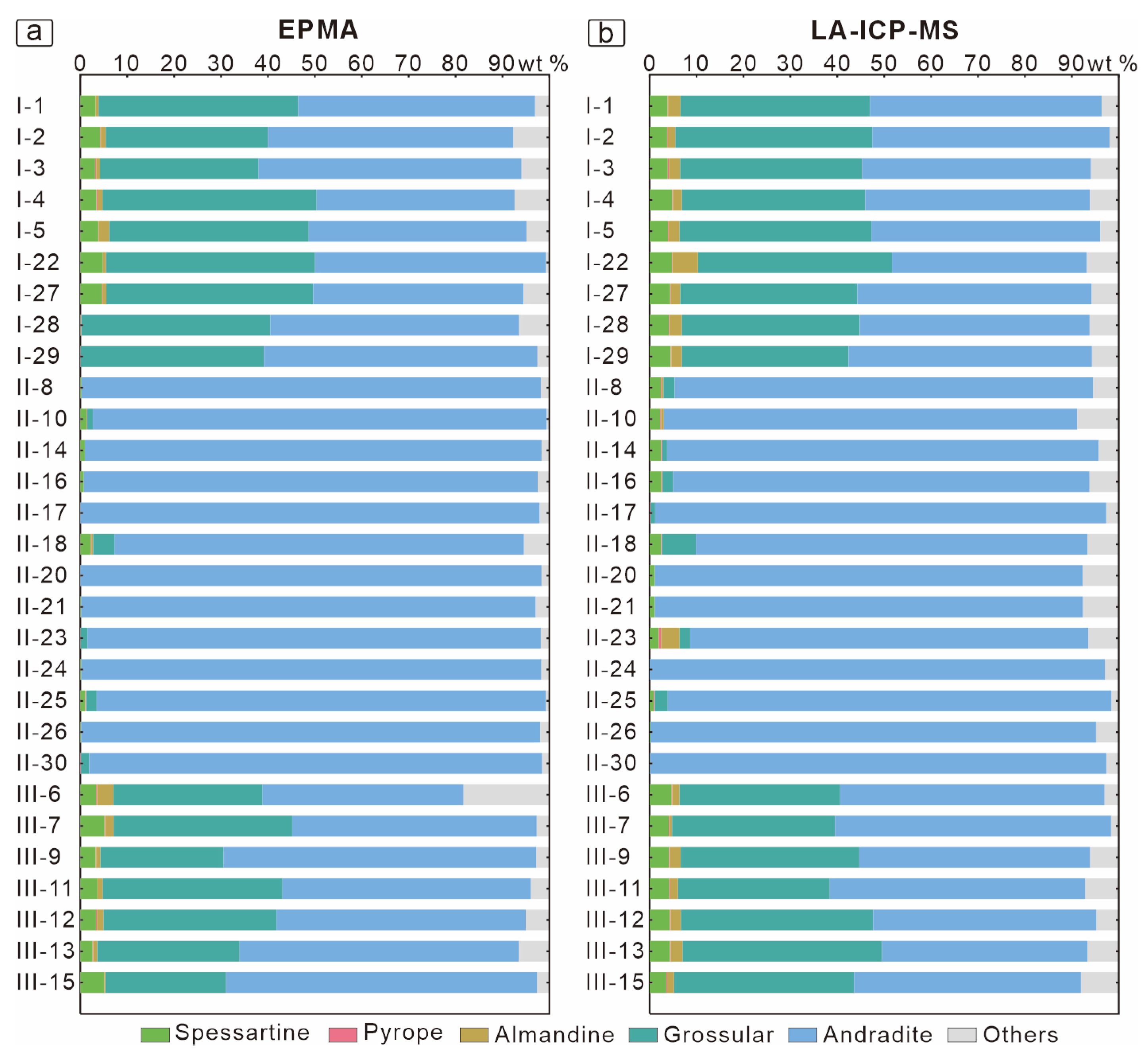

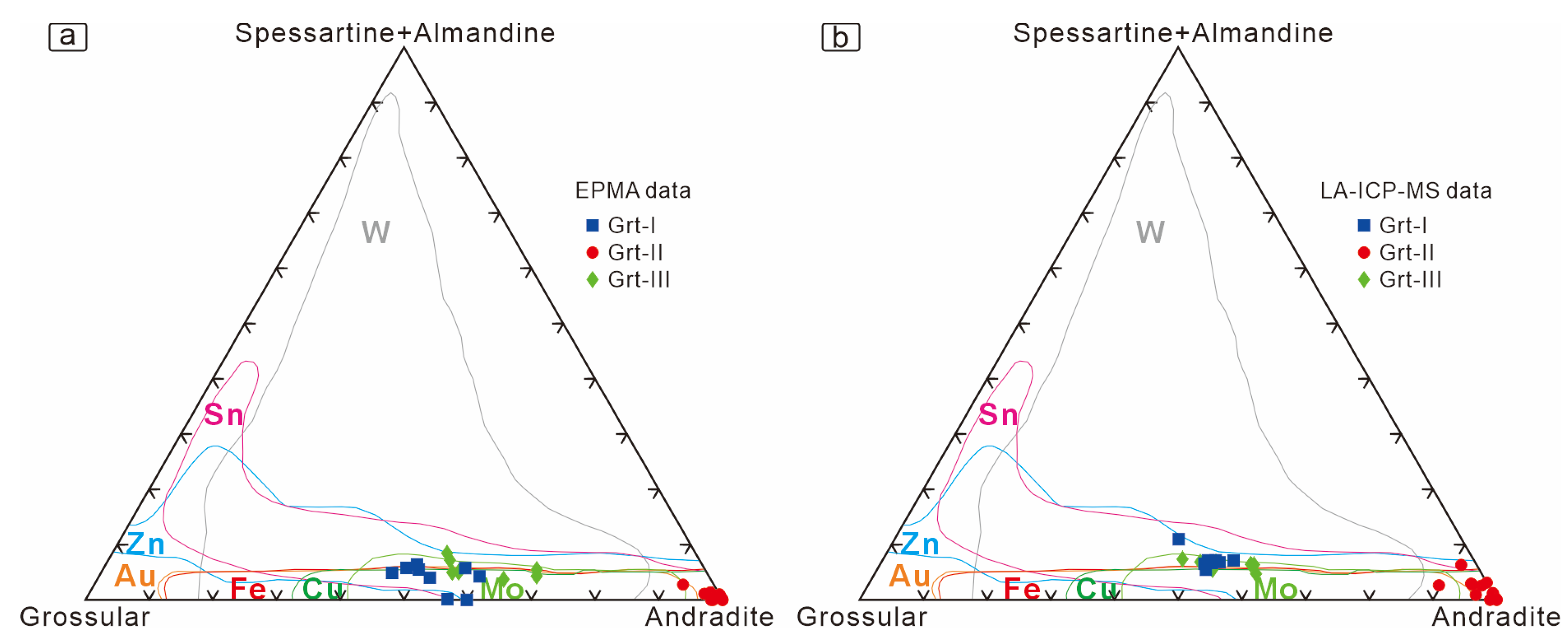

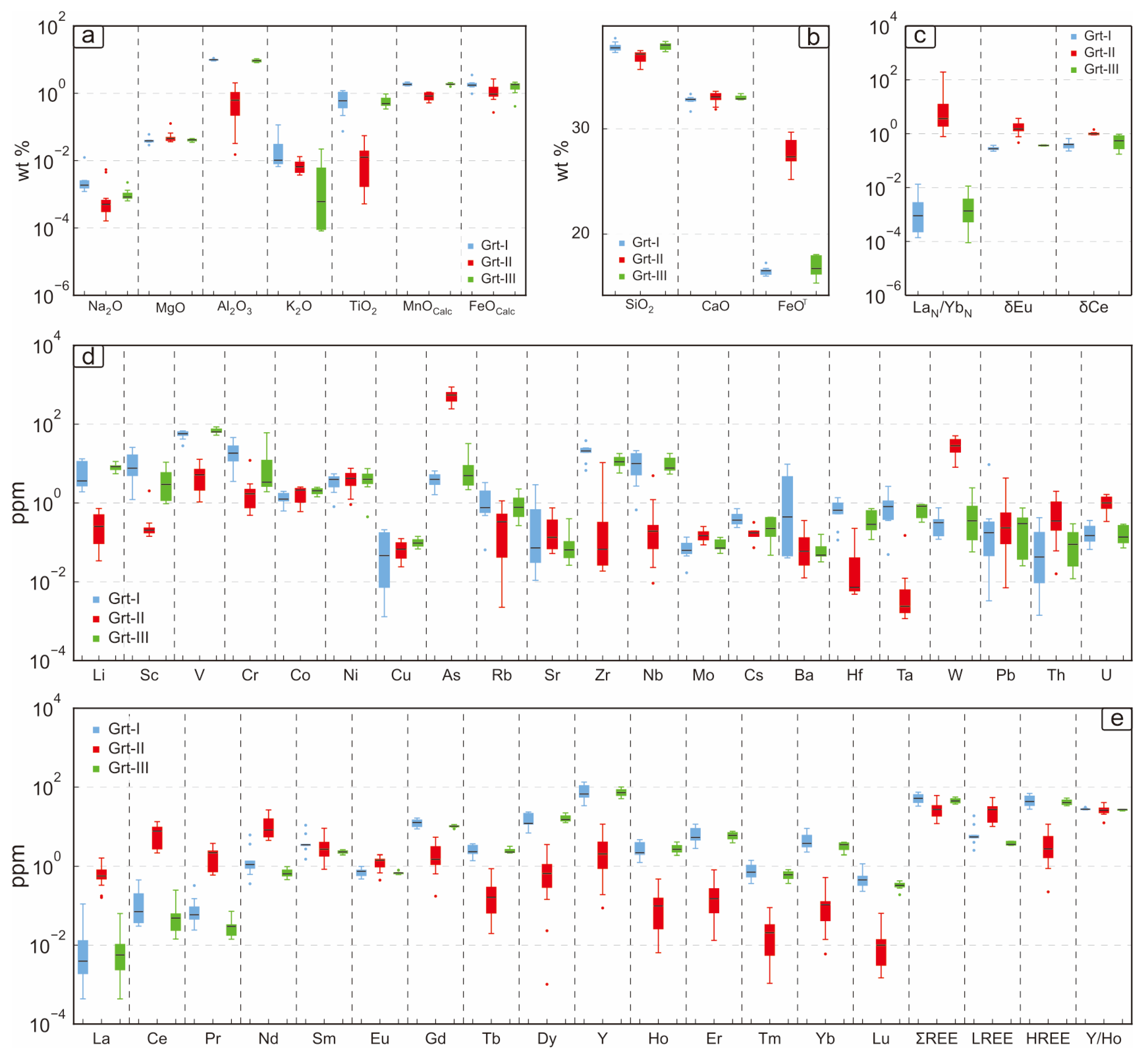

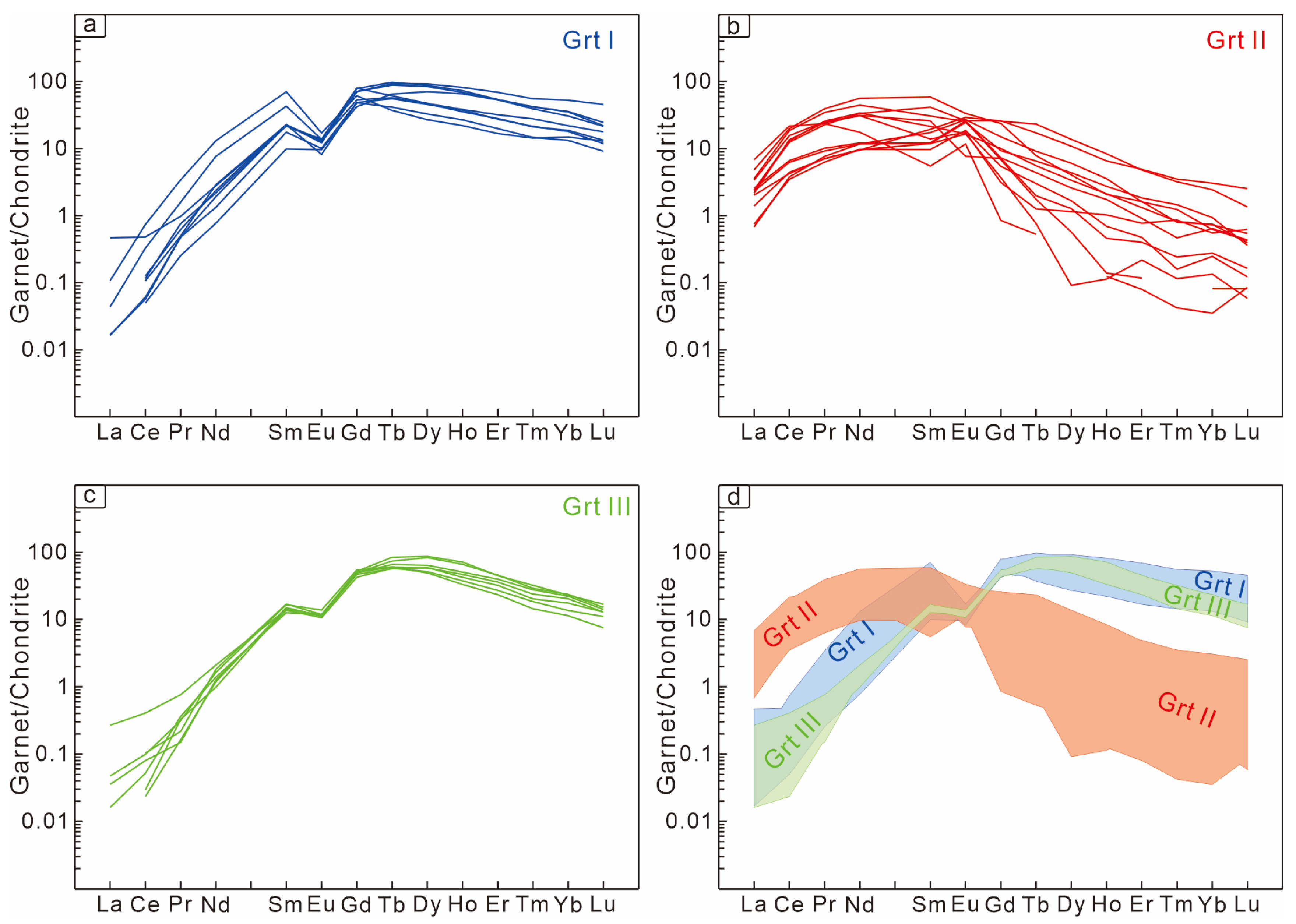

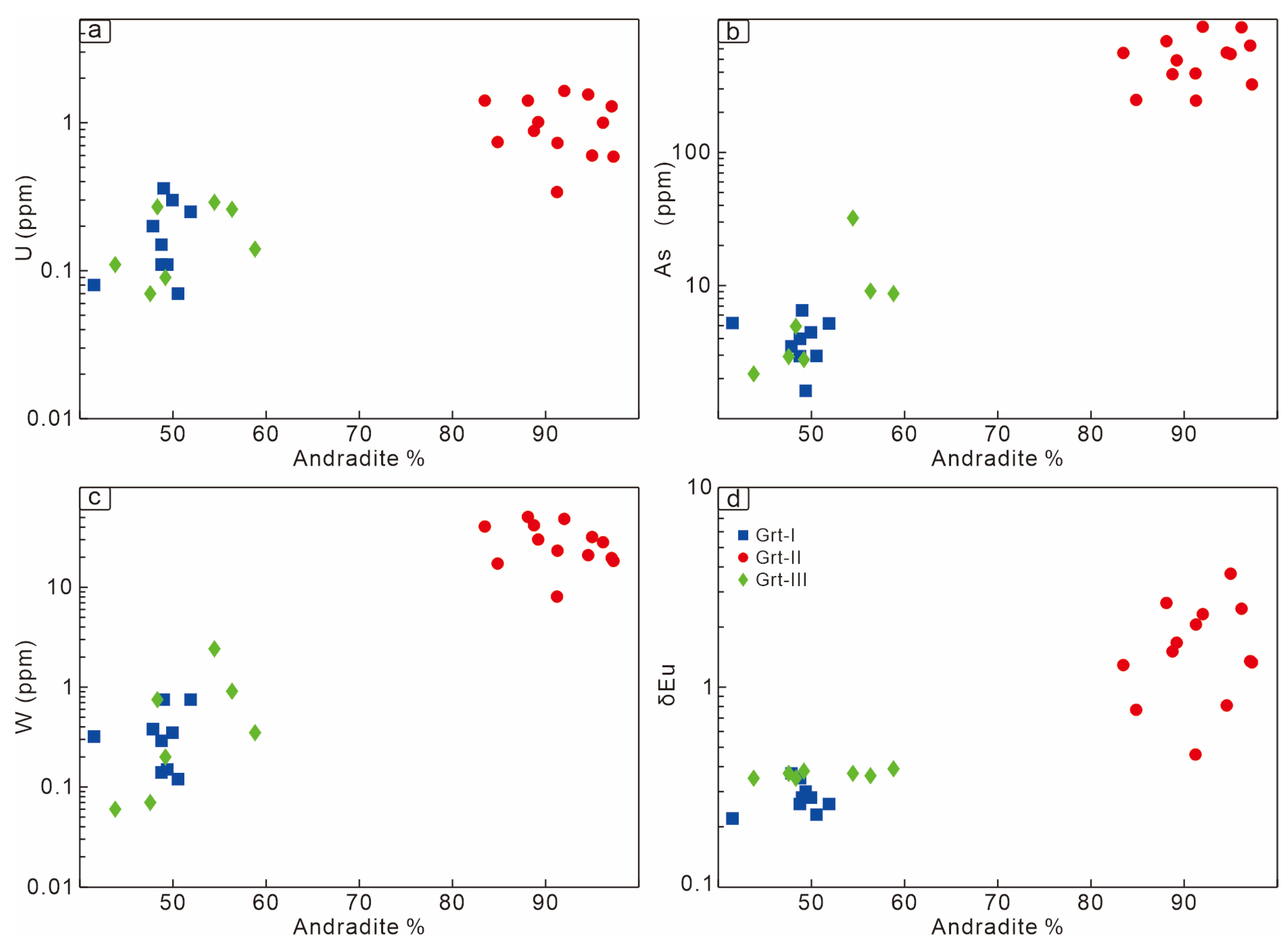

6.2. Garnet Chemistry

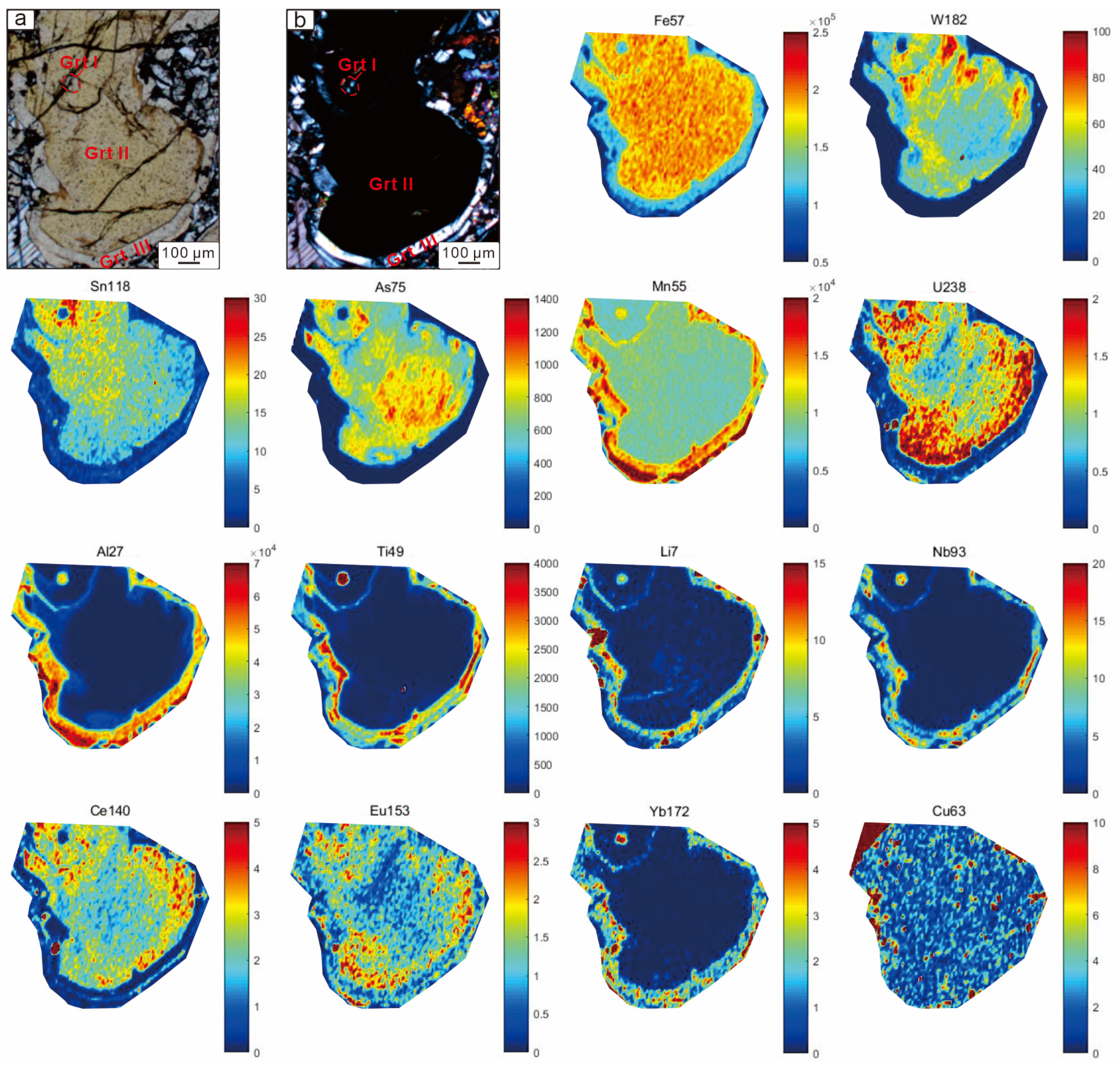

6.3. Garnet Element Mapping

7. Discussions

7.1. Garnet Optical Anomaly

7.2. Formation Conditions of Multi-Stage Garnets

7.2.1. Temperature

7.2.2. Oxygen Fugacity

7.2.3. pH

7.2.4. Water–Rock Interaction

7.2.5. Fluid Composition

7.3. Evolution of the Hydrothermal Fluid

7.4. Implications for Mineralization

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bi, R.; Wang, F.; Zhang, W. Whole Rock, Mineral Chemistry during Skarn Mineralization-Case Study from Tongshan Cu-Mo Skarn Profile. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Qiu, J.; Hofstra, A.H.; Harlov, D.E.; Ren, Z.; Li, J. Revealing the role of crystal chemistry in REE fractionation in skarn garnets: Insights from lattice-strain theory. Contrib. Miner. Pet. 2024, 179, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Li, S.R.; Santosh, M.; Luo, J.Y.; Li, C.L.; Song, J.Y.; Lu, J.; Liang, X. The genesis and gold mineralization of the crypto-explosive breccia pipe in the Yixingzhai gold region, central North China Craton. Geol. J. 2020, 55, 5664–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Choi, S.; Seo, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Cho, S.; Lee, G.; Lee, Y.J. A genetic model of the giant Sangdong W–Mo skarn deposit in the Taebaeksan Basin, South Korea. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 150, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Song, Y.; Kang, I.; Shim, J.; Chung, D.; Park, C. Metasomatic changes during periodic fluid flux recorded in grandite garnet from the Weondong W-skarn deposit, South Korea. Chem. Geol. 2017, 451, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarin, K.A. Garnet composition as an indicator of Cu mineralization: Evidence from skarn deposits of NW Iran. J. Geochem. Explor. 2004, 81, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liang, T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B. Skarn Formation and Zn–Cu Mineralization in the Dachang Sn Polymetallic Ore Field, Guangxi: Insights from Skarn Rock Assemblage and Geochemistry. Minerals 2024, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, A.D.; Konakci, N.; Sasmaz, A. Garnet Geochemistry of Pertek Skarns (Tunceli, Turkey) and U-Pb Age Findings. Minerals 2024, 14, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Santosh, M. Factors controlling the crystal morphology and chemistry of garnet in skarn deposits: A case study from the Cuihongshan polymetallic deposit, Lesser Xing’an Range, NE China. Am. Miner. 2019, 104, 1455–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtukenberg, A.G.; Popov, D.Y.; Punin, Y.O. Growth ordering and anomalous birefringence in ugrandite garnets. Miner. Mag. 2005, 69, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtukenberg, A.G.; Punin, Y.O.; Frank-Kamenetskaya, O.V.; Kovalev, O.G.; Sokolov, P.B. On the origin of anomalous birefringence in grandite garnets. Miner. Mag. 2001, 65, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizuki, M. Origin of optical variations in grossular-andradite garnet. Am. Miner. 1984, 69, 328–338. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, D.T.; Hatch, D.M.; Phillips, W.R.; Kulaksiz, S. Crystal chemistry and symmetry of a birefringent tetragonal pyralspite75-grandite25garnet. Am. Miner. 1992, 77, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Lessing, P.; Standish, R.P. Zoned Garnet from Crested Butte, Colorado. Am. Miner. 1973, 58, 840–842. [Google Scholar]

- McAloon, B.P.; Hofmeister, A.M. Single-crystal IR spectroscopy of grossular-andradite garnets. Am. Miner. 1995, 80, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, G.R.; Aines, R.D. Spectroscopy of a birefringent grossular from Asbestos, Quebec, Canada. Am. Miner. 1986, 71, 779–780. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Y.; Ge, C.; Ning, S.Y.; Nie, L.Q.; Zhong, G.X.; White, N.C. A new approach to LA-ICP-MS mapping and application in geology. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 3422–3436, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, G.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, X. Big data mining on trace element geochemistry of sphalerite. J. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 252, 107254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Niu, S.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X. Controlling factors for Co enrichment in mineral deposits: Insights from magnetite trace element big data. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 183, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, L.; Santosh, M.; Yan, G.; Shen, J.; Yuan, M.; Alam, M.; Wang, Z.; Li, S. Spatial distribution and chemical characteristics of bastnäsite and monazite provide insights into the Bayan Obo deposit, the world’s largest rare earth element mineralization. Lithos 2025, 514–515, 108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Wang, Y.W.; Sun, R.L.; Yang, W.L.; Chen, Y. Characteristics of porphyry metallogenic system and orebody localization regularities of Yixingzhai gold deposit. Miner. Depos. 2025, 44, 299–316, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.G. Metallogenic characteristics and genesis analysis of Yixingzhai gold deposit in the Fanshi County of Shanxi, China. Miner. Resour. Geol. 2022, 36, 299–309, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.M. Geological characteristics, geochronology, and prospecting direction of the Tietangdong cryptoexplosive breccia pipe in the Yixingzhai Gold Deposit, Shanxi Province. Gold 2022, 43, 9–18, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, W.; Deng, X. Geology and Geochronology of Magmatic–Hydrothermal Breccia Pipes in the Yixingzhai Gold Deposit: Implications for Ore Genesis and Regional Exploration. Minerals 2024, 14, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Santosh, M.; Niu, S.; Li, Q.; Lu, J. The magmatic–hydrothermal mineralization systems of the Yixingzhai and Xinzhuang gold deposits in the central North China Craton. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 88, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Santosh, M.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Song, J.; Zhang, X. Metallogeny in response to lithospheric thinning and craton destruction: Geochemistry and U–Pb zircon chronology of the Yixingzhai gold deposit, central North China Craton. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 56, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z. Formation mechanism of breccia pipe type in Yixingzhai gold deposit. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2008, 15, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Santosh, M.; Shen, J.; Zhang, H. Indicators of decratonic gold mineralization in the North China Craton. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 228, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Santosh, M. Metallogeny and craton destruction: Records from the North China Craton. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 56, 376–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Santosh, M.; Li, Q.; Niu, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, L. Timing and origin of Mesozoic magmatism and metallogeny in the Wutai-Hengshan region: Implications for destruction of the North China Craton. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 113, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, S.; Santosh, M.; Zhu, J.; Suo, X. Early Jurassic decratonic gold metallogenesis in the eastern North China Craton: Constraints from S-Pb-C-D-O isotopic systematics and pyrite Rb-Sr geochronology of the Guilaizhuang Te-Au deposit. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 92, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Meng, F.; Kong, F.; Niu, C. Microfossils from the Paleoproterozoic Hutuo Group, Shanxi, North China: Early evidence for eukaryotic metabolism. Precambrian Res. 2020, 342, 105650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, Q.; Santosh, M.; Li, J. Discovery of the Huronian Glaciation Event in China: Evidence from glacigenic diamictites in the Hutuo Group in Wutai Shan. Precambrian Res. 2019, 320, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Z. The typomorphic characteristic of pyrite from the Kanggultage gold deposit and the significance to Au ore prospecting. Geol. Prospect. 1999, 35, 6–8+23, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Deng, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Luo, T.; Li, J. Halogen fractionation during vapor-brine phase separation revealed by in situ Cl, Br, and I analysis of scapolite from the Yixingzhai gold deposit, North China Craton. Am. Miner. 2024, 109, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Hu, H.; Jin, X.; Deng, X.; Robinson, P.T.; Gao, W.; Zhang, L. Chemical and boron isotopic composition of tourmaline from the Yixingzhai gold deposit, North China Craton: Proxies for ore fluids evolution and mineral exploration. Am. Miner. 2024, 109, 1443–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, G.P.; Deng, X.D.; Li, J.W. Garnet U-Pb dating constraints on the timing of breccia pipes formation and genesis of gold mineralization in Yixingzhai gold deposit, Shanxi province. Earth Sci. 2020, 45, 108–117, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.Z. Element geochemistry and age of the altered-porphyry gold mineralization in Yixingzhai gold deposit, Fanshi city, Shanxi Province. Geol. Miner. Resour. South China 2018, 34, 134–141, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jurek, K.; Hul Nsk, V. The use and accuracy of the ZAF correction procedure for the microanalysis of glasses. Mikrochim. Acta 1980, 73, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locock, A.J. An Excel spreadsheet to recast analyses of garnet into end-member components, and a synopsis of the crystal chemistry of natural silicate garnets. Comput. Geosci. 2008, 34, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Fan, Y.; Ba, T.; Meng, X. CorelKit: An extensible CorelDraw VBA program for geoscience drawing. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 34, 735–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinert, L.D.; Dipple, G.M.; Nicolescu, S. World skarn deposits. In One Hundredth Anniversary Volume; Hedenquist, J.W., Thompson, J.F.H., Goldfarb, R.J., Richards, J.P., Eds.; Society of Economic Geologists, Inc.: Littleton, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McAloon, B.P.; Hofmeister, A.M. Single-crystal absorption and reflection infrared spectroscopy of birefringent grossular-andradite garnets. Am. Miner. 1993, 78, 957–967. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, D.; Tversky, A. The Weighing of Evidence and the Determinants of Confidence. Cogn. Psychol. 1992, 24, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.; Knaack, C.; Meinert, L.D.; Moretti, R. REE in skarn systems: A LA-ICP-MS study of garnets from the Crown Jewel gold deposit. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa Ballaran, T.; Carpenter, M.A.; Geiger, C.A.; Koziol, A.M. Local structural heterogeneity in garnet solid solutions. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1999, 26, 554–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.E.; Bird, D.K. Fluorian garnets from the host rocks of the Skaergaard Intrusion; implications for metamorphic fluid composition. Am. Miner. 1990, 75, 859–873. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeister, A.M.; Schaal, R.B.; Campbell, K.R.; Berry, S.L.; Fagan, T.J. Prevalence and origin of birefringence in 48 garnets from the pyrope-almandine -grossularite-spessartine quaternary. Am. Mineral. 1998, 83, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Cao, Z.M. An Investigation of Birefringence of Garnets from a Skarn Deposit. Geol. Sci. 1988, 3, 229–238+304, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Takéuchi, Y.; Haga, N.; Umizu, S.; Sato, G. The derivative structure of silicate garnets in grandite. Z. Fur Krist. Mater. 1982, 158, 53–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gali, S. Grandite garnet structures in connection with the growth mechanism. Z. Für Krist.-Cryst. Mater. 1983, 163, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, U.; Pollok, K. Molecular simulations of interfacial and thermodynamic mixing properties of grossular-andradite garnets. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2002, 29, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, M.F.; Liu, K.; Guo, X.N. The current status and prospects of the study of garnet in skarn for hydrothermal fluid evolution tracing and mineralization zoning. Acta Petrol. et Mineral. 2016, 35, 147–161, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jamtveit, B.; Wogelius, R.A.; Fraser, D.G. Zonation patterns of skarn garnets: Records of hydrothermal system evolution. Geology 1993, 21, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinert, L.D. Application of skarn deposit zonation models to mineral exploration. Explor. Min. Geol. 1997, 6, 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.J. Characteristics and metasomatism mechanism of garnet of grossularite-andradite series. Acta Petrol. et Mineral. 1994, 13, 342–352, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, B.E.; Liou, J.G. The low-temperature stability of andradite in C-O-H fluids. Am. Miner. 1978, 63, 378–393. [Google Scholar]

- Gutzmer, J.; Pack, A.; Lüders, V.; Wilkinson, J.; Beukes, N.; Niekerk, H. Formation of jasper and andradite during low-temperature hydrothermal seafloor metamorphism, Ongeluk Formation, South Africa. Contrib. Miner. Pet. 2001, 142, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić, B.; Srećković-Batoćanin, D.; Filipov, P.; Tančić, P.; Sokol, K. Anisotropic grossular–andradite garnets: Evidence of two stage skarn evolution from Rudnik, Central Serbia. Geol. Carpathica 2021, 72, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Y. Age determination of gem-quality green vanadium grossular (Var. Tsavorite) from the Neoproterozoic metamorphic mozambique belt, Kenya and Tanzania. Crystals 2025, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amthauer, G.; Rossman, G.R. The hydrous component in andradite garnet. Am. Mineral. 1998, 83, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Decoding the oxygen fugacity of ore-forming fluids from garnet chemistry, the Longgen skarn Pb-Zn deposit, Tibet. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 126, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.P.; Henderson, P.; Jeffries, T.E.R.; Long, J.; Williams, C.T. The Rare Earth Elements and Uranium in Garnets from the Beinn an Dubhaich Aureole, Skye, Scotland, UK: Constraints on Processes in a Dynamic Hydrothermal System. J. Petrol. 2004, 45, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnock, J.M.; Polya, D.A.; Gault, A.G.; Wogelius, R.A. Direct EXAFS evidence for incorporation of As5+ in the tetrahedral site of natural andraditic garnet. Am. Miner. 2007, 92, 1856–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Halls, C.; Stanley, C.J. Tin-bearing skarns of South China: Geological setting and mineralogy. Ore Geol. Rev. 1992, 7, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrasov, I.Y. Features of tin mineralization in carbonate deposits, as in Eastern Siberia. Int. Geol. Rev. 1971, 13, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIver, J.R.; Mihalik, P. Stannian andradite from “Davib Ost”, South West Africa. Can. Mineral. 1975, 13, 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Ciobanu, C.L.; Cook, N.J.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, X.; Wade, B.P. Skarn formation and trace elements in garnet and associated minerals from Zhibula copper deposit, Gangdese Belt, southern Tibet. Lithos 2016, 262, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhivya, L.; Janani, N.; Palanivel, B.; Murugan, R. Li+ transport properties of W substituted Li7La3Zr2O12 cubic lithium garnets. AIP Adv. 2013, 3, 082115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, M. Rare-earth element mobility during hydrothermal and metamorphic fluid-rock interaction and the significance of the oxidation state of europium. Chem. Geol. 1991, 93, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H.; Gamo, T.; Kim, E.S.; Shitashima, K.; Yanagisawa, F.; Tsutsumi, M.; Ishibashi, J.; Sano, Y.; Wakita, H.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Unique chemistry of the hydrothermal solution in the mid-Okinawa Trough Backarc Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1990, 17, 2133–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, P.R.L. Hydrothermal alteration in active geothermal fields. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1978, 6, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamtveit, B.; Hervig, R.L. Constraints on Transport and Kinetics in Hydrothermal Systems from Zoned Garnet Crystals. Science 1994, 263, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.B. Surface enrichment and trace-element uptake during crystal growth. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 5013–5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. 1976, A32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, E. Pre-biotic organic matter from comets and asteroids. Nature 1989, 342, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, M.; Dulski, P. Distribution of yttrium and rare-earth elements in the Penge and Kuruman iron-formations, Transvaal Supergroup, South Africa. Precambrian Res. 1996, 79, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Seltmann, R.; Zhu, J.; McClenaghan, S. Editorial: Accessory mineral geochemistry and its application in mineral exploration. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1230816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, T.; Fan, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J. Separation of iron and copper in skarn deposits from the Yueshan ore field, eastern China: The control of magma physicochemical conditions. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 174, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, H.; Kuang, H.; Li, R.; Xiao, B.; Wu, C.; Zheng, H.; Feng, R.; Shakouri, M.; Pan, Y. Enrichment mechanism of heavy rare earth elements in magmatic-hydrothermal titanite: Insights from SXAS/XPS experiments and first-principles calculations and implications for regolith-hosted HREE deposits. Am. Miner. 2025, 110, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, T.; Fan, Y.; Guo, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J. Fe-Cu separation in skarn deposits: Insights from magmatic and hydrothermal titanite. Lithos 2025, 514–515, 108218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, B.; Ghasemi Siani, M.; Zhang, R.; Neubauer, F.; Lentz, D.R.; Fazel, E.T.; Karimi Shahraki, B. Mineralogy, petrochronology, geochemistry, and fluid inclusion characteristics of the Dardvay skarn iron deposit, Sangan mining district, NE Iran. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 134, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, D. REE Distribution Character in Skarn Garnet and Its Geological Implication. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2021, 57, 446–458, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Tao, R.; Hong, Z.; Xingchun, Z.; Weiguang, Z. REE geochemistry of garnets from the Langdu skarn copper deposit. Earth Sci. Front. 2010, 17, 348–358, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmit, V.M. Geochemistry; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1954; 730p. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, W.D. Rates and mechanism of Y, REE, and Cr diffusion in garnet. Am. Miner. 2012, 97, 1598–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverjensky, D.A. Europium redox equilibria in aqueous solution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1984, 67, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.E.; Seyfried, W.E. REE controls in ultramafic hosted MOR hydrothermal systems: An experimental study at elevated temperature and pressure. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.L.; Yuan, S.D.; Yuan, Y.B. Geochemical characteristics of garnet in the Huangshaping polymetallic deposit, southern Hunan: Implications for the genesis of Cu and W-Sn mineralization. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2018, 34, 2581–2597, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jing, S.H. On the minerogenetic conditions and ore resource of the Yixingzhai gold ore deposit in Fanshi County, Shanxi Province. Bull. Shenyang Inst. Geol. Miner. Resour. Chin. Acad. Geol. Sci. 1986, 13, 126–134, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Mungall, J.E.; Brenan, J.M. Partitioning of platinum-group elements and Au between sulfide liquid and basalt and the origins of mantle-crust fractionation of the chalcophile elements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 125, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovski, G.S.; Akinfiev, N.N.; Borisova, A.Y.; Zotov, A.V.; Kouzmanov, K. Gold speciation and transport in geological fluids: Insights from experiments and physical-chemical modelling. In Gold-Transporting Hydrothermal Fluids in the Earth’s Crust; Garofalo, P.S., Ridley, J.R., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah Jane, B. Chalcophile Elements. In Encyclopedia of Geochemistry; White, W.M., Ed.; Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Xu, Z. Metasomatized lithospherie mantle and gold mineralization. Earth Sci. 2021, 46, 4197–4229, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Jones, A.E.; Bowell, R.J.; Migdisov, A.A. Gold in Solution. Elements 2009, 5, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, J.; Lu, J.J.; Zhang, R.Q.; Zhao, L.H. Composition, Trace Element and Infrared Spectrum of Garnet from Three Types of W-Sn Bearing Skarns in the South of China. Acta Mieralogica Sin. 2013, 33, 315–328, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Stefánsson, A.; Seward, T.M. Stability of chloridogold(I) complexes in aqueous solutions from 300 to 600 °C and from 500 to 1800 bar. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 4559–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhen, S.M.; Bai, H.J.; Cha, Z.J. Restrictions on gold mineraization by zircon oxygen fugacitfrom the Paleozoic-Mesozoic magmatic rocks in the Zhangiiakou district, northern margin of the North China Craton. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2024, 40, 2519–2537, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Tagirov, B.R.; Trigub, A.L.; Filimonova, O.N.; Kvashnina, K.O.; Nickolsky, M.S.; Lafuerza, S.; Chareev, D.A. Gold Transport in Hydrothermal Chloride-Bearing Fluids: Insights from in Situ X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy and ab Initio Molecular Dynamics. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2019, 3, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Audétat, A.; Dolejš, D. Solubility of gold in oxidized, sulfur-bearing fluids at 500–850 °C and 200–230 MPa: A synthetic fluid inclusion study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2018, 222, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Garnet Generation | End-Member | Temperature | Oxygen Fugacity | pH | Water–Rock Reaction | Fluid Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grt I | And42–52Gro36–42Alm2–5Spe4–5 | Higher | Medium | Neutral | Weak | Low Cl |

| Grt II | And83–97Gro0–7Alm0–4Spe0–3 | Lower | High | Weakly acidic | Strong | High Cl; Increase in Co, Ni, and Cu Contents |

| Grt III | And44–59Gro32–43Alm1–3Spe4–5 | Higher | Medium | Neutral | Weak | Low Cl |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Liang, X. Garnet Geochemistry of the Tietangdong Breccia Pipe, Yixingzhai Gold Deposit, North China Craton: Constraints on Hydrothermal Fluid Evolution. Minerals 2025, 15, 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121290

Zhang J, Lu J, Zhang J, Wang F, Liang X. Garnet Geochemistry of the Tietangdong Breccia Pipe, Yixingzhai Gold Deposit, North China Craton: Constraints on Hydrothermal Fluid Evolution. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121290

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Junwu, Jing Lu, Juquan Zhang, Fangyue Wang, and Xian Liang. 2025. "Garnet Geochemistry of the Tietangdong Breccia Pipe, Yixingzhai Gold Deposit, North China Craton: Constraints on Hydrothermal Fluid Evolution" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121290

APA StyleZhang, J., Lu, J., Zhang, J., Wang, F., & Liang, X. (2025). Garnet Geochemistry of the Tietangdong Breccia Pipe, Yixingzhai Gold Deposit, North China Craton: Constraints on Hydrothermal Fluid Evolution. Minerals, 15(12), 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121290