Fluid Inclusion Constraints on the Formation Conditions of the Evevpenta Au–Ag Epithermal Deposit, Kamchatka, Russia

Abstract

1. Introduction

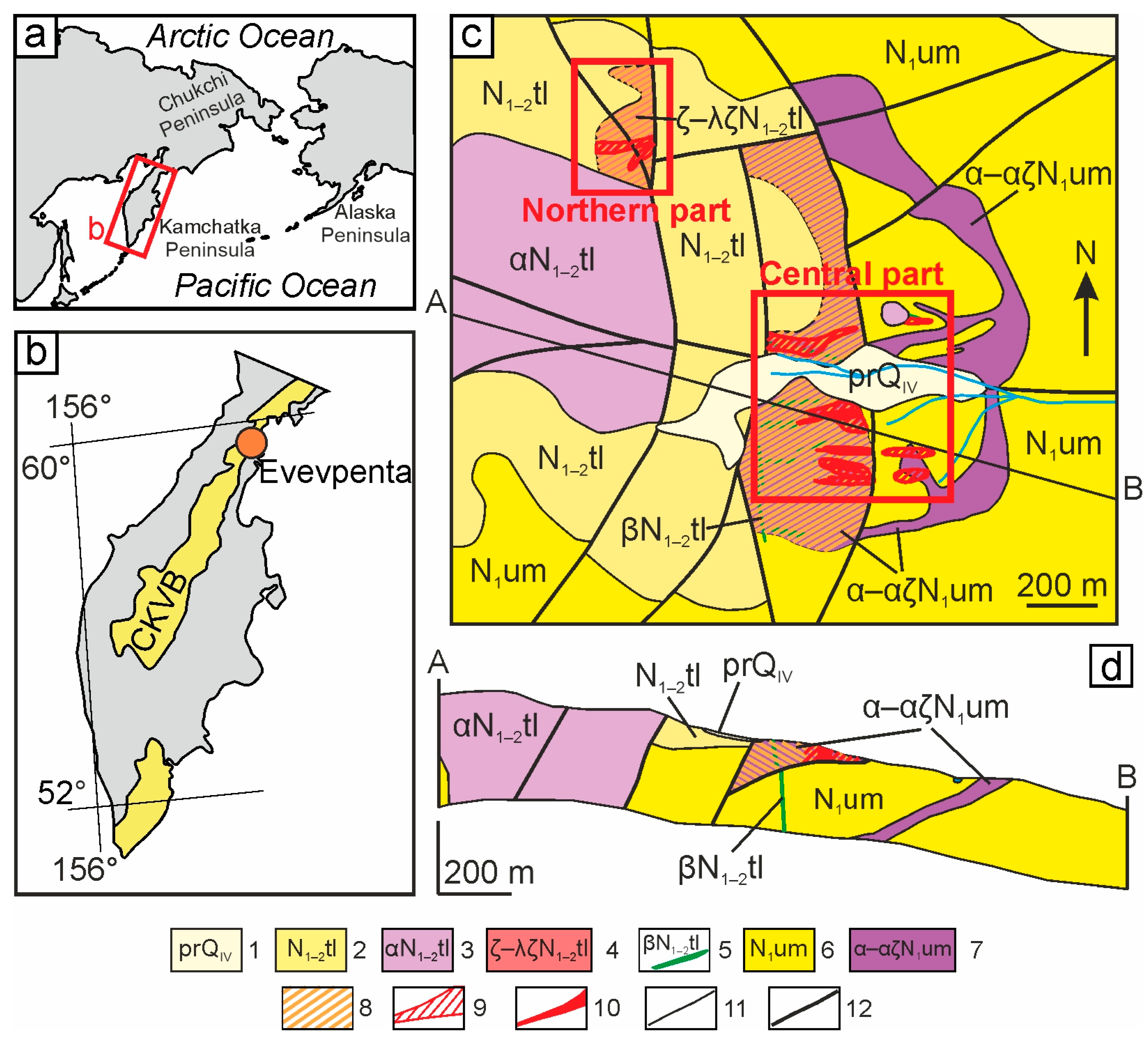

2. Geology and Mineral Associations of the Evevpenta Deposit

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Optical Microscopy

3.2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM–EDS)

3.2.3. Microthermometry

3.2.4. Raman Spectroscopy

4. Results

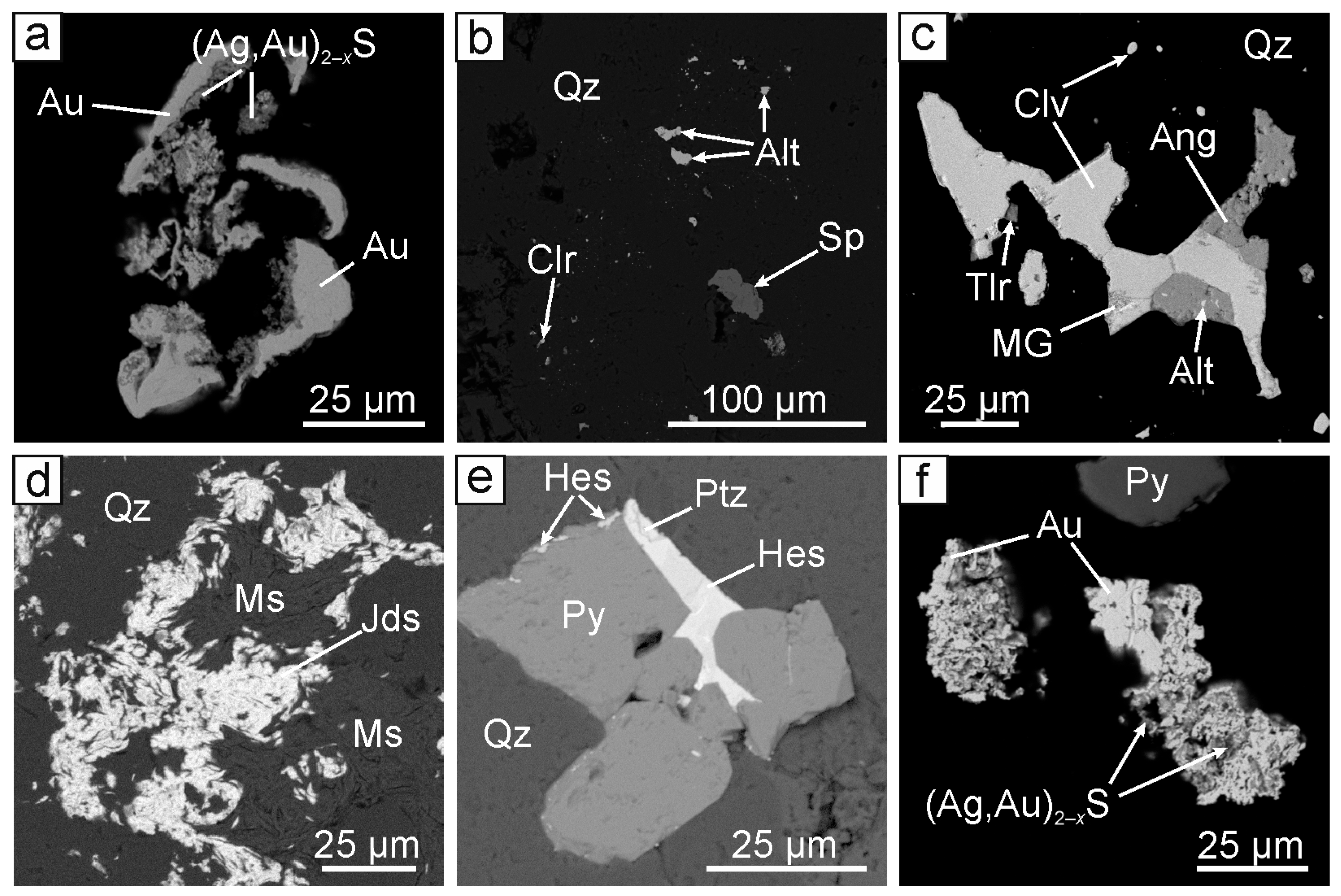

4.1. Mineral Composition of the Evevpenta Deposit Ores

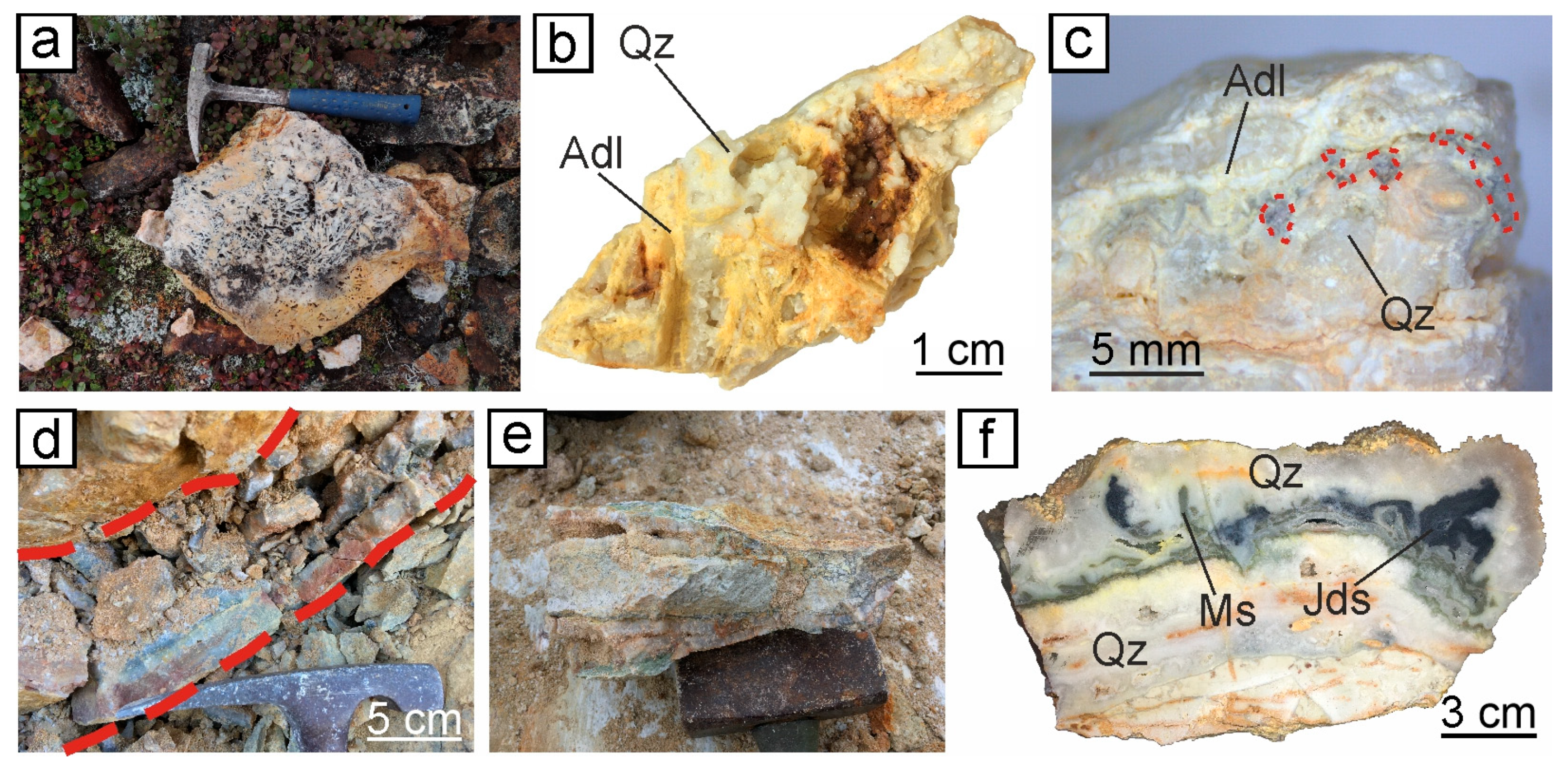

4.1.1. The Central Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

4.1.2. The Northern Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

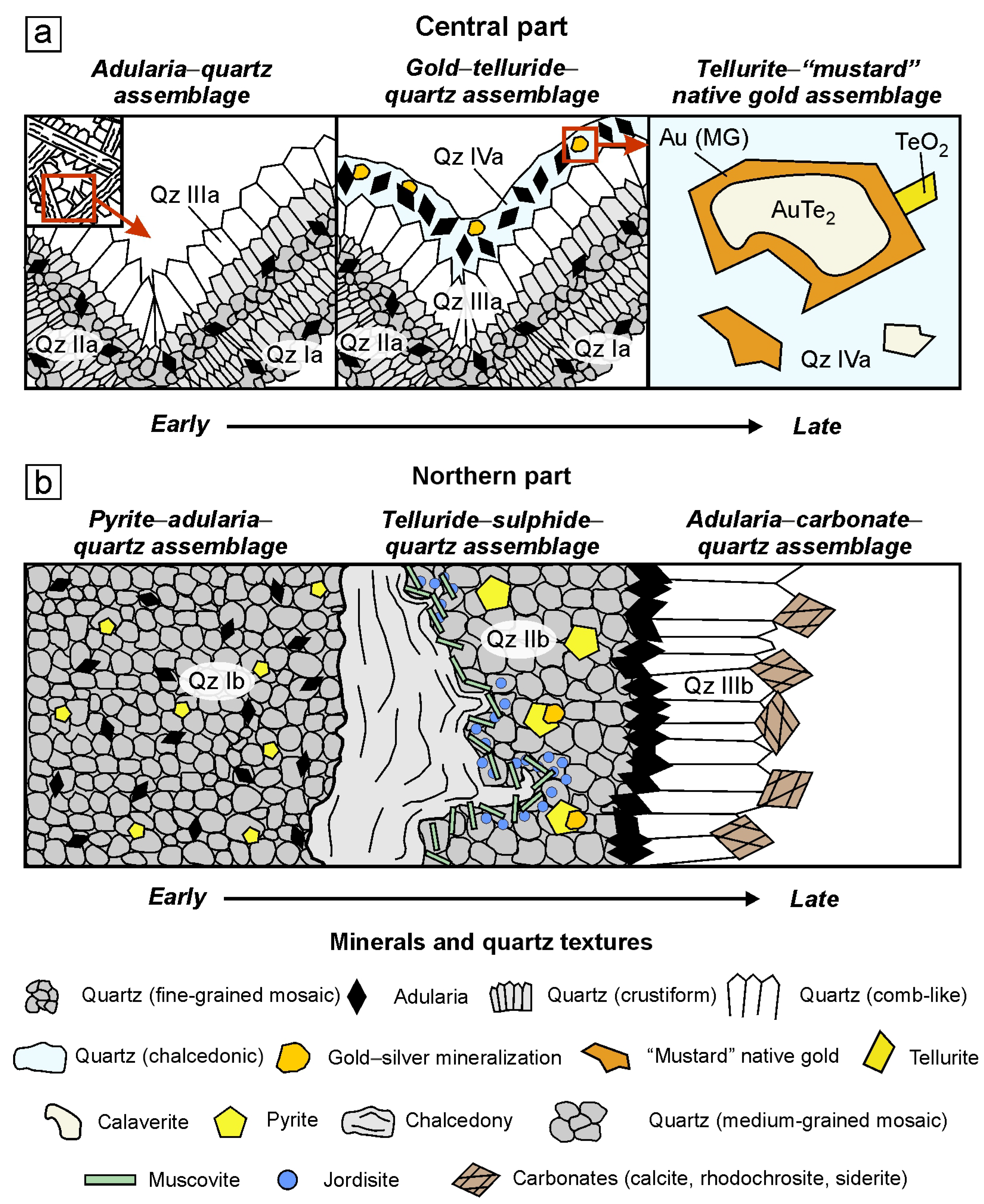

4.2. The Adularia–Quartz Vein Textures and Sequence of Mineral Formation

4.2.1. The Central Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

4.2.2. The Northern Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

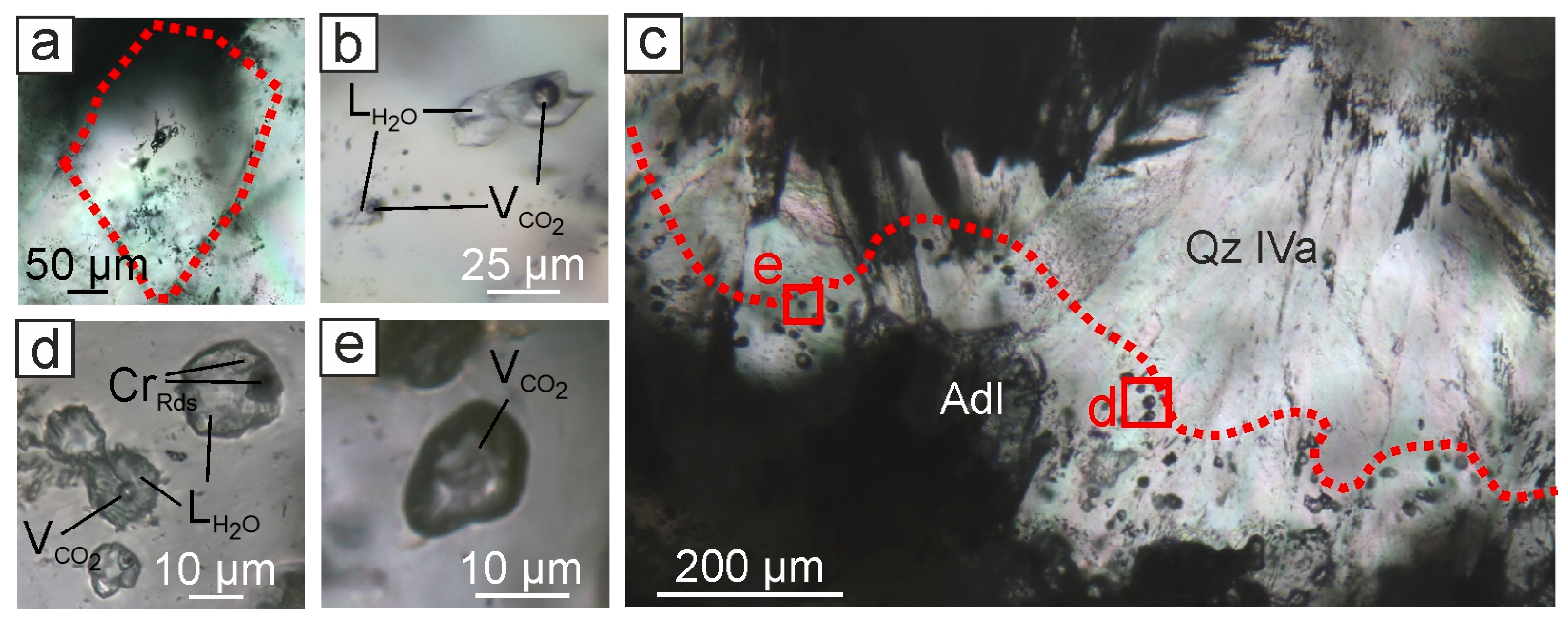

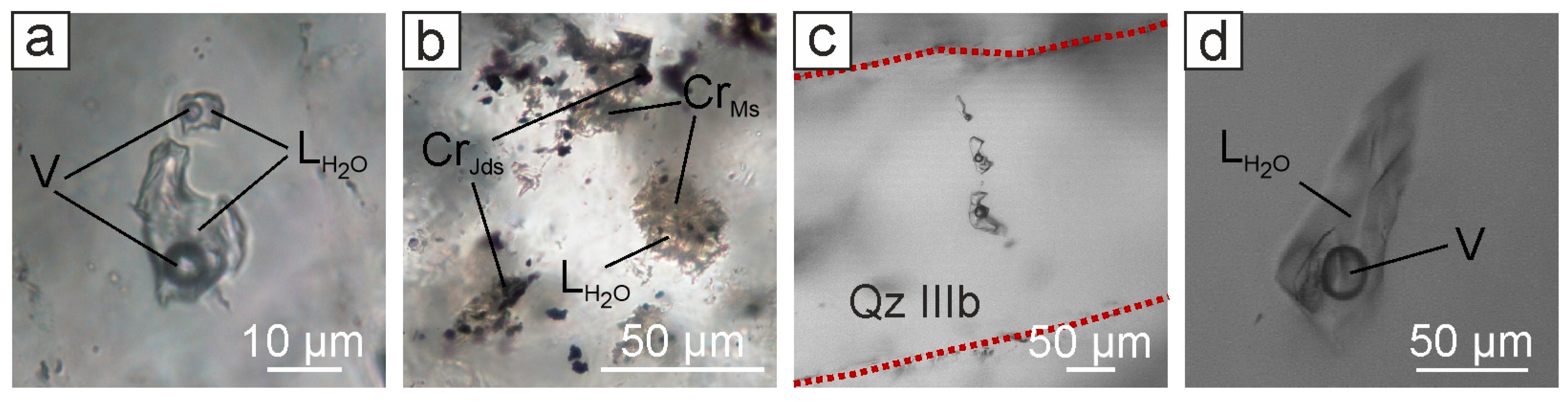

4.3. Fluid Inclusion Types

4.3.1. The Central Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

4.3.2. The Northern Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

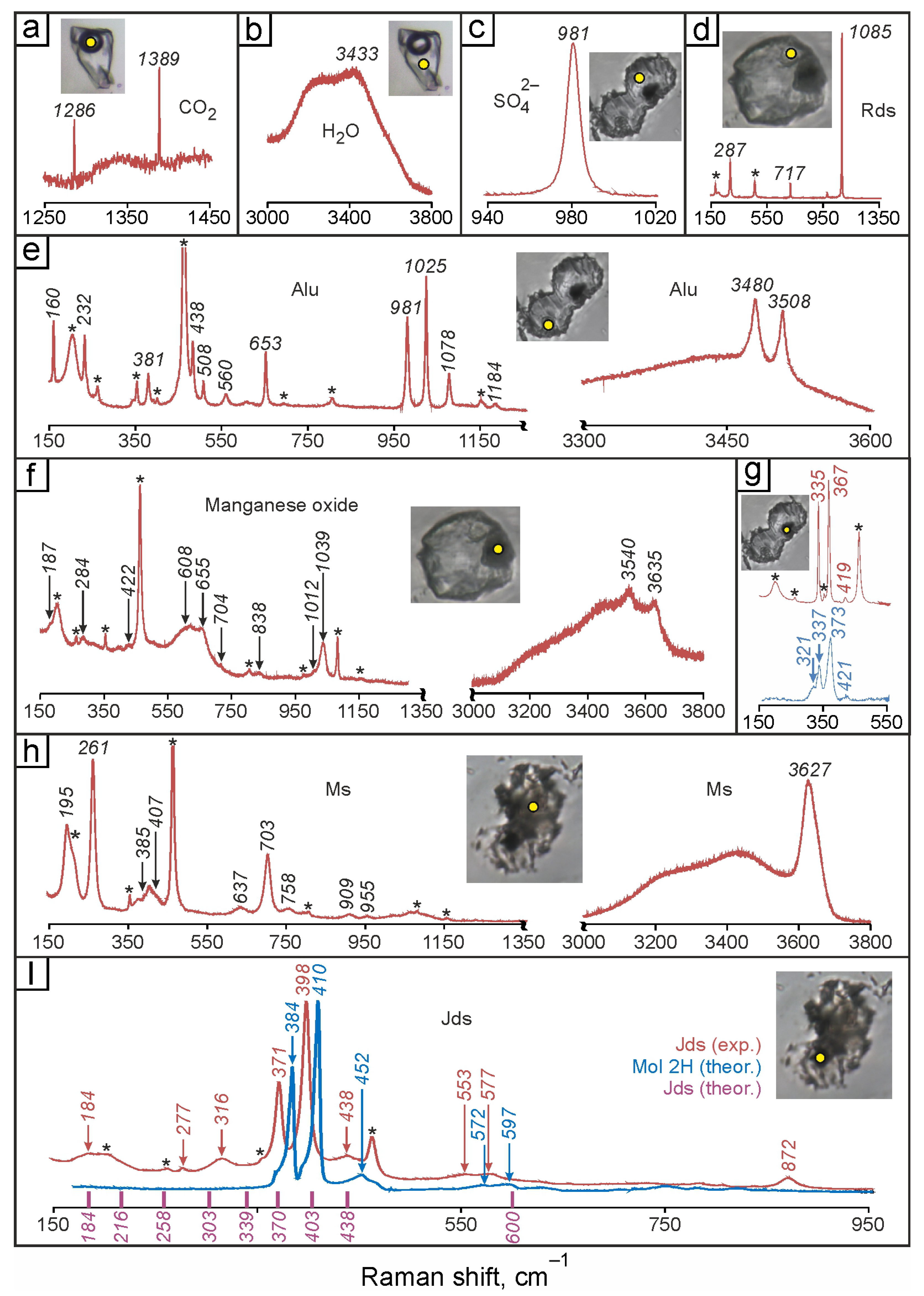

4.4. Raman Spectroscopy of Fluid Inclusions

4.4.1. The Central Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

4.4.2. The Northern Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

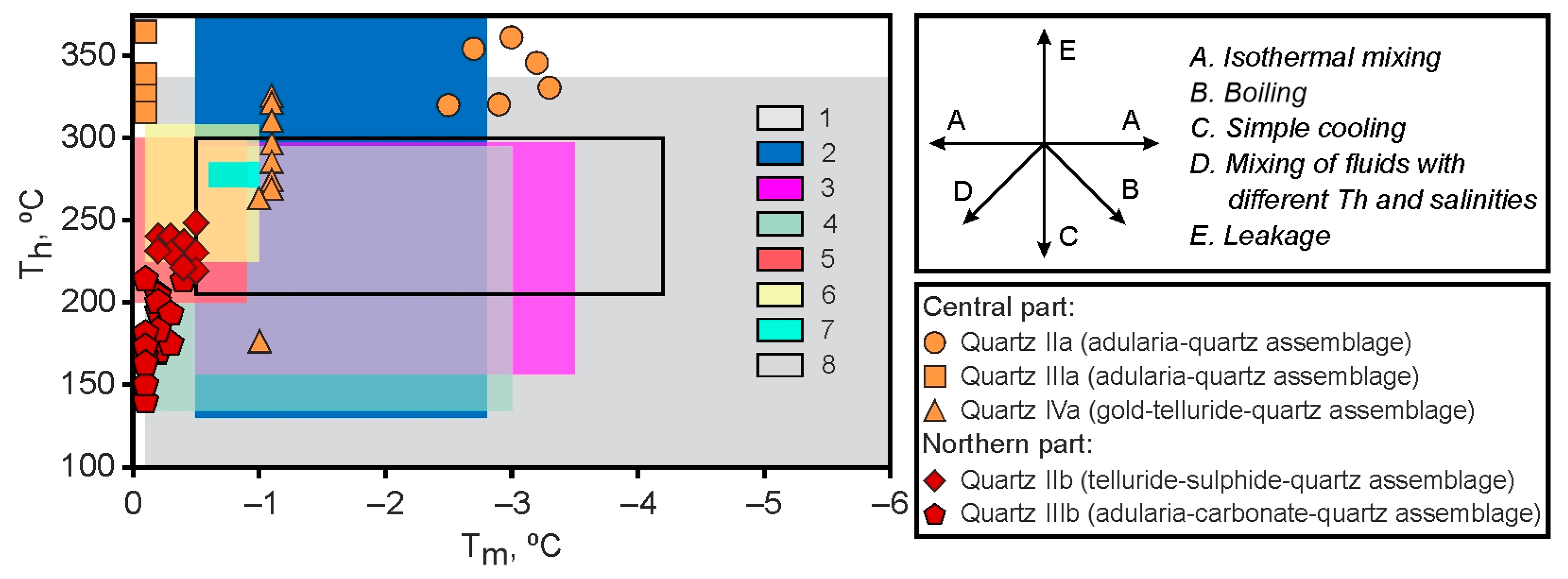

4.5. Microthermometry of Fluid Inclusions

4.5.1. The Central Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

4.5.2. The Northern Part of the Evevpenta Deposit

5. Discussion

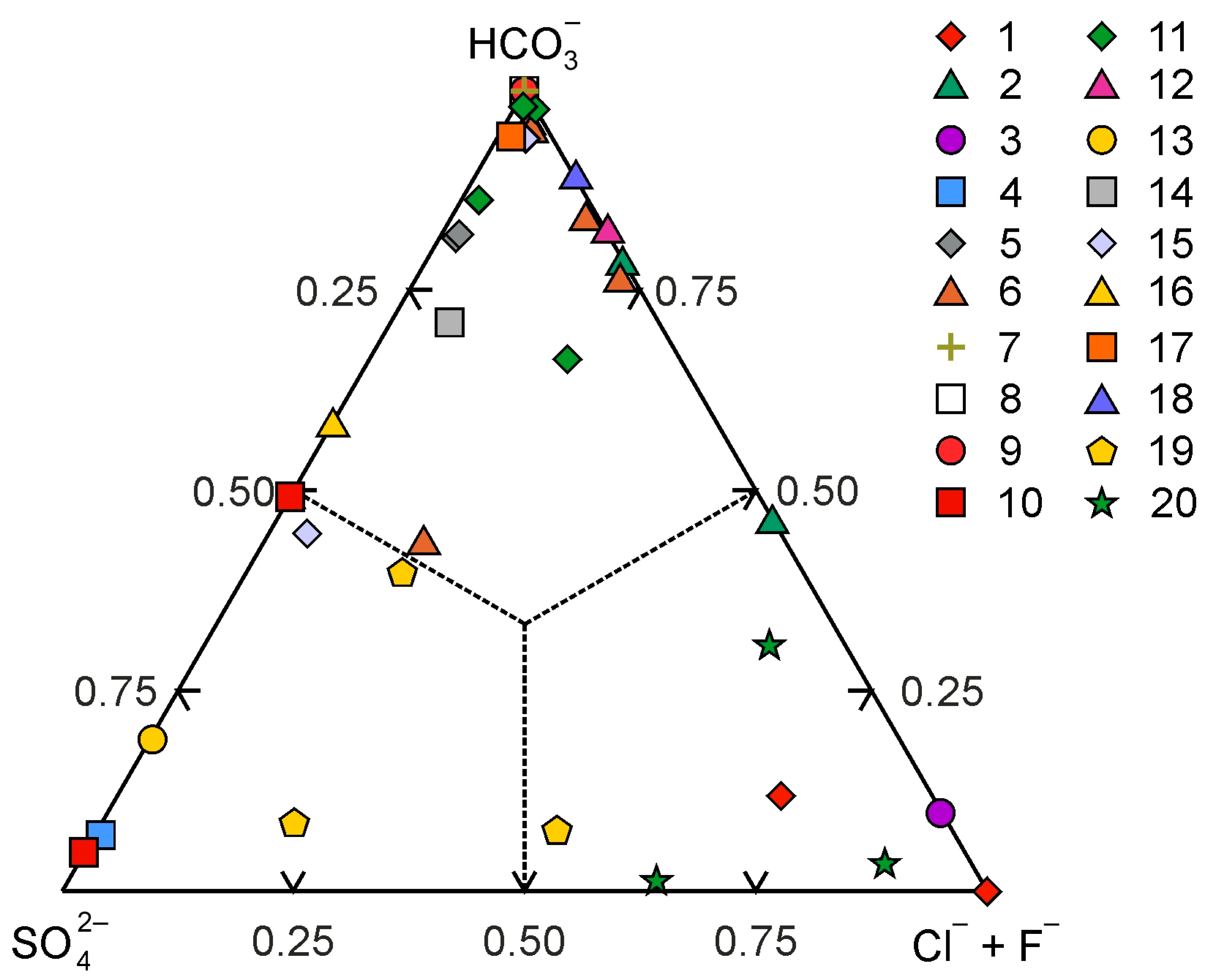

5.1. Composition and P–T Conditions of Ore-Forming Fluids

5.2. Formation Conditions Comparison: The Evevpenta Epithermal Au–Ag Deposit and Reference Epithermal Au–Ag Deposits from the Kamchatka Region and Northeast Russia

| Deposit (Type) | Th, °C | Te, °C | Tm, °C | Salinity, wt.% (NaCl-eq.) | Fluid Chemistry | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evevpenta (adularia–sericite) | 140–364 | −8.5–−5.0 | −3.3–−0.1 | – | Sulfates and bicarbonates of Na, K, Mg | This study |

| Rodnikovoe (adularia–sericite) | 150–260 | – | −2.8–−0.6 | 1.0–3.0 | – | [19] |

| 160–265 | – | −1.5–−0.5 | 0.8–2.5 | – | [16] | |

| Asachinskoe (adularia–sericite) | 95–320 | −56.0–−10.0 | −6.0–−0.1 | 0.2–9.2 | Chlorides of Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe | [22] |

| 157–337 | – | −1.5–−0.6 | 1.0–2.6 | – | [21] | |

| Mutnovskoe (adularia–sericite) | 156–297 | – | −3.5–−0.5 | 0.8–5.7 | – | [20] |

| Baranyevskoe (adularia–sericite) | 226–298 | −49.0–−27.0 | −0.7–−0.2 | 0.4–1.2 | Chlorides of Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe; carbonate of K | [25] |

| 225–305 | −35.0–−24.0 | −0.8–−0.1 | 0.4–1.2 | Chlorides of Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe | [26] | |

| 210–308 | – | −1.0–−0.6 | 0.5–1.7 | – | [17] | |

| Aginskoe (adularia–sericite) | 200–300 | – | −0.9 − 0.0 | 0.4–1.6 | – | [23] |

| Lazurnoe (adularia–sericite) | 270–285 | –22.5–−21.7 | −1.0–−0.6 | 1.0–1.7 | Chlorides of Na | [17] |

| Kumroch (adularia–sericite) | 205–300 | −32.0–−29.5 | −4.2–−0.5 | 0.9–6.8 | Chlorides of Na, K, Fe | [17] |

| Maletoyvayam (acide–sulfate) | 173–290 | – | −3.0–−0.6 | 1.0–5.0 | – | [17] |

| 135–295 | −38.0–−23.0 | −2.5–−0.1 | 0.2–4.3 | Chlorides of Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe; carbonate of K | [24] |

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The adularia–quartz veins formed at temperatures ranging from 140 to 364 °C, consistent with low- to medium-temperature mineralization conditions, from low-salinity fluids (Tm from −0.1 to −3.3 °C). Gold-bearing mineral assemblages crystallized within narrower temperature intervals: gold–telluride–quartz from 325 to 175 °C, and telluride–sulfide–quartz from 219 to 258 °C. A decrease in mineralization temperature was observed from early to late mineral assemblages, as well as within each individual assemblage. The Central part of the deposit is characterized by higher-temperature and relatively concentrated fluids, whereas the Northern part experienced lower-temperature and significantly more diluted fluids.

- (2)

- The primary components of the fluids were H2O and low-density CO2, with the early mineral assemblages being more enriched in CO2. The fluids contained bicarbonates and sulfates of Na, K, and Mg. This fluid inclusion composition is not typical for epithermal deposits in Kamchatka, although the presence of bicarbonates and sulfates is frequently noted in fluid inclusions from quartz in adularia–sericite type Au–Ag deposits of the Northeast Russia. The sulfate signature is likely due to near-surface oxidation of H2S.

- (3)

- The presence in the ores of mineral assemblages of native gold and silver with sulfides and Au–Ag tellurides, and gangue adularia, in combination with the development of propylitic and argillic metasomatic alterations, indicates that mineralization occurred under reduced to neutral conditions at a relatively high fugacity of sulfur and tellurium. The low- to medium-temperature range, low fluid salinity, and the specific ore mineral assemblages confirm that the Evevpenta deposit belongs to the adularia–sericite (or low-sulfidation) type of epithermal systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Results | Theoretical Data [53] | |

|---|---|---|

| Shift, cm−1 | ||

| Jordisite | Jordisite | Molybdenite |

| – | 148 sh | – |

| 184 sh | 184 sh | – |

| – | 216 | – |

| – | 258 sh | – |

| 277 w | – | 285 |

| – | 303 w | – |

| 316 w | – | – |

| – | 339 w | – |

| 371 s | 370 (h-MoS2) | 382 s |

| 398 s | 403 (h-MoS2) | 408 s |

| 438 w | 438 sh | 451 |

| 553 w | – | – |

| 577 w | – | – |

| – | 600 w | – |

| 872 w | – | – |

References

- Singer, D.A. World class base and precious metal deposits: A quantitative analysis. Econ. Geol. 1995, 90, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimmel, H.E. Earth’s continental crustal gold endowment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 267, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.V.; Sidorov, A.A. Economic implications of epithermal gold-silver deposits. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2013, 83, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenquist, J.W.; Lowenstern, J.B. The role of magmas in the formation of hydrothermal ore deposits. Nature 1994, 370, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.C.; Hedenquist, J.W. Epithermal gold deposits: Styles, characteristics and exploration. Publ. SEG Newsl. 1995, 23, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.A.; Vikre, P.G.; du Bray, E.A.; Blakely, R.J.; Fey, D.L.; Rockwell, B.W.; Mauk, J.L.; Anderson, E.D.; Graybeal, F.T. Descriptive Models for Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposits; USGS Scientific Investigation Report 2010-5070-Q; United States Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 247. [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, R.; Hedenquist, J. Linkages between volcanotectonic settings, ore-fluid compositions, and epithermal precious metal deposits. Soc. Econ. Geol. Spec. Publ. 2003, 10, 315–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, S.F.; White, N.C.; John, D.A. Geological characteristics of epithermal precious and base metal deposits. Econ. Geol. 2005, 100, 485–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, P.; Foley, N.K.; Hayba, D.O. Comparative anatomy of volcanic-hosted epithermal deposits; acid-sulfate and adularia-sericite types. Econ. Geol. 1987, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnikov, N.S.; Tolstykh, N.D. Epithermal Deposits of Kamchatka, Russia. Geol. Ore Depos. 2023, 65, 124–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedenquist, J.W.; Arribas, A.; Gonzalez-Urien, E.J. Exploration for epithermal gold deposits. Rev. Econ. Geol. 2000, 13, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J.; Lecumberri-Sanchez, P.; Moncada, D.; Steele-Maclnnes, P. Fluid Inclusions in Hydrothermal Ore Deposits. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. In Treatise on Geochemistry, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bortnikov, N.S.; Volkov, A.V.; Savva, N.E.; Prokofiev, V.Y.; Kolova, E.E.; Dolomanova-Topol’, A.A.; Galyamov, A.L.; Murashov, K.Y. Epithermal Au-Ag-Se-Te deposits of the Chukchi peninsula (Arctic zone of Russia): Metallogeny, mineral assemblages, and fluid regime. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2022, 63, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács, Á.; Molnár, F.; Turi, J.; Mogessie, A.; Menzies, J.C. Ore Mineralogy and Fluid Inclusion Constraints on the Temporal and Spatial Evolution of a High-Sulfidation Epithermal Cu-Au-Ag Deposit in the Recsk Ore Complex, Hungary. Econ. Geol. 2017, 112, 1461–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, D.A.; Bozkaya, G.; Bozkaya, O. Direct observation and measurement of Au and Ag in epithermal mineralizing fluids. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 111, 102955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstykh, N.; Shapovalova, M.; Shaparenko, E.; Bukhanova, D. The Role of Selenium and Hydrocarbons in Au-Ag Ore Formation in the Rodnikovoe Low-Sulfidation (LS) Epithermal Deposit, Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia. Minerals 2022, 12, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalova, M.; Shaparenko, E.; Tolstykh, N. Geochemistry and Fluid Inclusion of Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposits in Kamchatka, Russia. Minerals 2025, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, I.D. Gold-Silver Formation of Kamchatka; VSEGEI: St. Peterburg, Russia, 1999; 112p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, R.; Matsueda, H.; Okrugin, V.M. Hydrothermal gold mineralization at the Rodnikovoe deposit in South Kamchatka, Russia. Resour. Geol. 2002, 52, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Matsueda, H.; Okrugin, V.M.; Ono, S. Polymetallic and Au-Ag Mineralizations at the Mutnovskoe Deposit in South Kamchatka, Russia. Resour. Geol. 2006, 56, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Matsueda, H.; Okrugin, V.M.; Ono, S. Epithermal Gold-Silver Mineralization of the Asachinskoe Deposit in South Kamchatka, Russia. Resour. Geol. 2007, 57, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovikov, A.; Lapukhov, A.; Borisenko, A.; Seryotkin, Y. The Asachinskoe epithermal Au-Ag deposit in Southern Kamchatka: Physicochemical conditions of formation. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2009, 50, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, E.D.; Matsueda, H.; Okrugin, V.M.; Takahashi, R.; Ono, S. Au-Ag-Te Mineralization of the Low-Sulfidation Epithermal Aginskoe Deposit, Central Kamchatka, Russia. Resour. Geol. 2013, 63, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, E.G.; Borovikov, A.A.; Tolstykh, N.D.; Bukhanova, D.S.; Chubarov, V.M. Gold mineralization at the Maletoyvayam Deposit (Koryak Highland, Russia) and Physicochemical Conditions of its Formation. Minerals 2020, 10, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstykh, N.; Bukhanova, D.; Shapovalova, M.; Borovikov, A.; Podlipsky, M. The gold mineralization of the Baranyevskoe Au-Ag epithermal deposit in Central Kamchatka. Minerals 2021, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakich, T.Y.; Nikolaeva, A.N.; Bukhanova, D.S.; Maximov, P.N.; Sinkina, E.A.; Kutyrev, A.V.; Sarsekeeva, E.M.; Zhegunov, P.S.; Levochskaya, D.V.; Rudmin, M.A. Mineral Features of the Copper Association of the Baranevskoe Epithermal Deposit (Central Kamchatka). Bull. Tomsk Polytech. Univ. Geo Assets Eng. 2022, 333, 74–87. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slyadnev, B.I.; Borovtsov, A.K.; Sidorenko, V.I.; Sapozhnikova, L.P. The State Geological Map of the Russian Federation. Scale 1: 1,000,000 (Third Generation); The Koryak-Kuril Series. Sheet O–58–Ust-Kamchatsk. Explanatory Note; VSEGEI Cartographic Factory: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2013; p. 256. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zhegunov, P.S.; Kutyrev, A.V.; Zhitova, E.S.; Moskaleva, S.V.; Schweigert, P.E. First Data on the Mineralology of the Evevpenta Epithermal Silver–Gold Ore Occurrence, Kamchatka, Russia. J. Volcanol. Seismol. 2024, 18, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhegunov, P.S.; Zhitova, E.S.; Kutyrev, A.V.; Schweigert, P.E.; Gribushin, K.A.; Moskaleva, S.V. Mustard Gold of the Evevpenta Epithermal Gold-Silver Occurrence (Kamchatka). Proc. of the Russ. Min. Soc. 2024, 153, 38–54. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryachev, N.A.; Pirajno, F. Gold deposits and gold metallogeny of Far East Russia. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 59, 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeiko, G.P.; Popruzhenko, S.V.; Palueva, A.A. Modern tectonic structure of the Kuril-Kamchatka region and magma formation conditions. In Geodynamics and Volcanism of the Kuril-Kamchatka Island-Arc System; The Institute of Volcanology & Geochemistry (IVGiG) FEB RAS: Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Russia, 2001; pp. 9–34. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Khanchuk, A.I. (Ed.) Geodynamics, Magmatism and Metallogeny of the East of Russia; Dalnauka: Vladivostok, Russia, 2006; Volume 1–2. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, M.S.; Solovyov, A.V. Kinematic model of the formation of the Olyutorsko-Kamchatsky folded region. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2009, 50, 863–880. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokleberg, W.J. (Ed.) Metallogenesis and Tectonics of Northeast Asia; U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1765; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2010; 610p. Available online: https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/pp1765 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Tsukanov, N.V. Tectonic-stratigraphic terranes, Kamchatka active margins: Structure, composition and geodynamics. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference “Volcanism and Related Processes”, IVS FEB RAS, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Russia, 30 March–1 April 2015; pp. 97–103. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Goryachev, N.A.; Volkov, A.V.; Sidorov, A.A.; Gamyanin, G.N.; Savva, N.E.; Okrugin, V.M. Au-Ag mineralization of volcanogenic belts of Northeast Asia. Litosfera 2010, 3, 36–50. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ermakov, N.P. Geochemical Systems of Fluid Inclusions in Minerals; Nedra: Moscow, Russia, 1972; 376p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Roedder, E. Fluid Inclusions in Minerals; Mir: Moscow, Russia, 1987; Volume 1–2. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov, F.P.; Prokofiev, V.Y.; Shatagin, N.N. Thermobarogeochemistry: University Textbook; Akademicheskii Prospekt: Moscow, Russia, 2008; 222p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Borisenko, A.S. A Study of Salt Composition of Solutions Trapped in Vapor-Liquid Inclusions Using Cryometric Method. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 1977, 8, 16–27. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- ArDi (Advanced spectRa Deconvolution Instrument). Available online: https://ardi.fmm.ru/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Shendrik, R.Y.; Plechov, P.Y.; Smirnov, S.Z. ArDI—The system of mineral vibrational spectroscopy data processing and analysis. New Data Miner. 2024, 58, 26–35. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- RRUFF: Database of Raman Spectroscopy, X-Ray Diffraction and Chemistry of Minerals. Available online: https://rruff.info/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Mironov, N.L.; Tobelko, D.P.; Portnyagin, M.V. Estimation of CO2 Content in the Gas Phase of Melt Inclusions Using Raman Spectroscopy: Case Study of Inclusions in Olivine from the Karymsky Volcano (Kamchatka). Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2020, 61, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstykh, N.D.; Palyanova, G.A.; Bobrova, O.V.; Sidorov, E.G. Mustard Gold of the Gaching Ore Deposit (Maletoyvayam Ore Field, Kamchatka, Russia). Minerals 2019, 9, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, L.W. Ilsemannite and jordisite. Am. Min. 1951, 36, 609–614. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhov, F.N. Ore Textures; Izd-vo AN SSSR: Moscow, Russia, 1961; 180p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Dong, G.; Morrison, G.; Jaireth, S. Quartz textures in epithermal veins, Queensland; classification, origin and implication. Econ. Geol. 1995, 90, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etoh, J.; Izawa, E.; Watanabe, K.; Taguchi, S.; Sekine, R. Bladed quartz and its relationship to gold mineralization in the Hishikari low-sulfidation epithermal gold deposit, Japan. Econ. Geol. 2002, 97, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezzotti, M.L.; Tecce, F.; Casagli, A. Raman spectroscopy for fluid inclusion analysis. J. Geochem. Explor. 2012, 112, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, B.F.; Steele-MacInnis, M.; Markl, G. Sulfate brines in fluid inclusions of hydrothermal veins: Compositional determinations in the system H2O–Na–Ca–Cl–SO4. Geoc. Cosm. Acta 2017, 209, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, S.; Bellatreccia, F.; Municchia, A.C. Raman spectra of natural manganese oxides. Jour. of Ram. Spect. 2019, 50, 873–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Vigasina, M.F. Raman spectra of minerals. In Vibrational (Infrared and Raman) Spectra of Minerals and Related Compounds; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 741–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Volkov, A.V.; Sidorov, A.A.; Savva, N.E.; Kolova, E.E.; Uyutnov, K.V.; Byankin, M.A. Geochemical peculiarities of ore-forming fluid of the Kupol Au-Ag epithermal deposit (Northeastern Russia). Dokl. Earth Sci. 2012, 447, 1310–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirgintsev, A.N.; Trushnikova, L.N.; Lavrent’eva, V.G. Solubility of Inorganic Substances in Water: Handbook; Khimiya: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 1972; 248p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Volkov, A.V.; Prokofiev, V.Y.; Sidorov, A.A.; Galyamov, A.L.; Wolfson, A.A.; Sidorova, N.V. Conditions for the Au–Ag Epithermal Mineralization in the Arykevaam Volcanic Field, Central Chukotka. J. Volcanol. Seismol. 2020, 14, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherlock, R.L. Hydrothermal alteration of volcanic rocks at the McLaughlin gold deposit, northern California. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1996, 33, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikre, P.G. Sinter-vein correlations at Buckskin Mountain, National district, Humboldt County, Nevada. Econ. Geol. 2007, 102, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.P.; Mauk, J.L. Hydrothermal alteration and veins at the epithermal Au-Ag deposits and prospects of the Waitekauri area, Hauraki goldfield, New Zealand. Econ. Geol. 2011, 106, 945–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.P.; Palinkas, S.S.; Mauk, J.L.; Bodnar, R.J. Fluid inclusion chemistry of adularia-sericite epithermal Au-Ag deposits of the southern Hauraki Goldfield, New Zealand. Econ. Geol. 2015, 110, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.J. Fluid inclusions in hydrothermal ore deposits. Lithos 2001, 55, 229–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.V.; Sidorov, A.A.; Savva, N.E. Epithermal Mineralization in the Kedon Paleozoic Volcano-Plutonic Belt, Northeast Russia: Geochemical Studies of Au–Ag Mineralization. J. Volcanol. Seismol. 2017, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J.; Reynolds, T.J.; Kuehn, C.A. Fluid inclusion systematics in epithermal systems. In Geology and Geochemistry of Epithermal Systems; Berger, B.R., Bethke, P.M., Eds.; Society of Economic Geologists: Chelsea, UK, 1985; pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolova, E.E.; Savva, N.E.; Zhuravkova, T.V.; Glukhov, A.N.; Palyanova, G.A. Au-Ag-S-Se-Cl-Br Mineralization at the Corrida Deposit (Russia) and Physicochemical Conditions of Ore Formation. Minerals 2021, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, B.; Siani, M.; Goldfarb, R.; Azizi, H.; Ganerod, M.; Marsh, E. Mineral assemblages, fluid evolution, and genesis of polymetallic epithermal veins, Glojeh district, NW Iran. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 78, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, R.H. Supergene oxidation of epithermal gold-silver mineralization in the Deseado massif, Patagonia, Argentina: Response to subduction of the Chile Ridge. Miner. Deposita 2019, 54, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.V.; Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Savva, N.E.; Sidorov, A.A.; Bayankin, M.A.; Uyutnov, K.V.; Kolova, E.E. Ore Formation at the Kupol Epithermal Gold-Silver Deposit in Northeastern Russia Deduced from Fluid Inclusion Study. Geol. Ore Depos. 2012, 54, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, I.K.; Kravtsova, R.G.; Chudnenko, K.V.; Artimenko, M.V. A physicochemical model for the volcanic hydrothermal ore-forming system of epithermal gold-silver deposits, Northeastern Russia. J. Geochem. Explor. 2000, 69–70, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.V.; Prokofiev, V.Y.; Sidorov, A.A.; Vinokurov, S.F.; Elmanov, A.A.; Murashov, K.Y.; Sidorova, N.V. The Conditions of Generation for the Au–Ag Epithermal Mineralization in the Amguema–Kanchalan Volcanic Field, Eastern Chukotka. J. Volcanol. Seismol. 2019, 13, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, N.E.; Pal’yanova, G.A.; Byankin, M.A. The problem of genesis of gold and silver sulfides and selenides in the Kupol deposit (Chukotka Peninsula, Russia). Rus. Geol. Geophys. 2012, 53, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstykh, N.; Vymazalova, A.; Tuhy, M.; Shapovalova, M. Conditions of formation of Au-Se-Te mineralization in the Gaching ore occurrence (Maletoyvayam ore field), Kamchatka, Russia. Miner. Mag. 2018, 82, 649–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharikov, V.A.; Rusinov, V.L. Metasomatism and Metasomatic Rocks; Nauchny Mir: Moscow, Russia, 1998; 492p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Pal’yanova, G.A. Physicochemical modeling of the coupled behavior of gold and silver in hydrothermal processes: Gold fineness, Au/Ag ratios and their possible implications. Chem. Geol. 2008, 255, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravkova, T.V.; Palyanova, G.A.; Kalinin, Y.A.; Goryachev, N.A.; Zinina, V.Y.; Zhitova, L.M. Physicochemical conditions of formation of gold and silver paragenesis at the Valunistoe deposit (Chukchi Peninsula). Rus. Geol. Geophys. 2019, 60, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Volkov, A.V.; Kal’ko, I.A.; Nikolaev, Y.N.; Sidorov, A.A.; Vlasov, E.A.; Wolfson, A.A.; Sidorova, N.V. Conditions of Formation of Ag–Au Epithermal Mineralization in the Ustveem Ore Cluster (Central Chukotka). Bull. North-East. Sci. Cent. Far East. Branch Russ. Acad. Sci. 2019, 3, 19–26. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Ali, A.A.; Volkov, A.V.; Savva, N.E.; Kolova, E.E.; Sidorov, A.A. Geochemical peculiarities of ore forming fluid of the Juliette Au–Ag epithermal deposit (Northeastern Russia). Dokl. Earth Sci. 2015, 460, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolova, E.E.; Volkov, A.V.; Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Savva, N.E.; Ali, A.A.; Sidorov, A.A. Features of the Ore-Forming Fluid at the Tikhoye Au–Ag Epithermal Deposit (Northeast Russia). Dokl. Earth Sci. 2015, 463, 566. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Savva, N.E.; Volkov, A.V.; Sidorov, A.A. Formation Features of Devonian Gold–Silver Epithermal Mineralization in Pipe-Shaped Ore Bodies. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2012, 443, 468–472. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Volkov, A.V.; Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Vinokurov, S.F.; Andreeva, O.V.; Kiseleva, G.D.; Galyamov, A.L.; Murashov, K.Y.; Sidorova, N.V. Valunistoe Epithermal Au–Ag Deposit (East Chukotka, Russia): Geological Structure, Mineralogical–Geochemical Peculiarities and Mineralization Conditions. Geol. Ore Depos. 2020, 62, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.V.; Savva, N.E.; Kolova, E.E.; Prokof’ev, V.Y.; Murashov, K.Y. Dvoinoe Au–Ag epithermal deposit, Chukchi peninsula, Russia. Geol. Ore Depos. 2018, 60, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.V.; Prokof’ev, V.Y. Formation Conditions and Composition of Ore-Forming Fluids in the Promezhutochnoe Gold and Silver Deposit (Central Chukchi Peninsula, Russia). Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2011, 52, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Texture | Number of Samples Studied | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Polished Wafers | Thin Sections | Polished Sections | ||

| Central part | ||||

| 101096 | Lattice bladed, colloform | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 101168 | Lattice bladed | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Northern part | ||||

| 205015 | Colloform-crustiform banded | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 205074/2 | Colloform-crustiform banded | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Main | Minor | Trace | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ore | Pyrite (FeS2) | Calaverite (AuTe2), native gold (Au,Ag), chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), galena (PbS), sphalerite (ZnS), acanthite (Ag2S), altaite (PbTe), hessite (Ag2Te), petzite (Ag3AuTe2), jordisite (MoS2) | Uytenbogaardtite–petrovskaite (Ag,Au)2–xS, native silver (Ag,Au), coloradoite (HgTe), naumannite (Ag2Se), argentopyrite (AgFe2S3) * |

| Supergene (secondary) | Iron oxides | Pyrolusite (MnO2), jarosite [KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6] | Bornite (Cu5FeS4), covellite (CuS), anglesite (PbSO4), chlorargyrite (AgCl), Br-bearing chlorargyrite [Ag(Cl,Br)], wulfenite (PbMoO4), tellurite/paratellurite (TeO2), spionkopite (Cu39S28), minerals of the kaolinite group [Al2(Si2O5)(OH)4], gypsum (CaSO4 · 2H2O) |

| Gangue | Quartz (SiO2) | Adularia (KAlSi3O8), calcite (CaCO3), rhodochrosite (MnCO3), siderite (FeCO3), muscovite [KAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2] | Baryte (BaSO4), celestine (SrSO4), alunite [KAl3(SO4)2(OH)6] * |

| Mineral Assemblage | Quartz Generation | Number of Measurements | FIA Type | Th, °C | Te, °C | Tm, °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central part | ||||||

| Adularia–quartz | Qz IIa | 6 | VL | 320–360 | −8.5–−5.5 | −3.3–−2.5 |

| 338 | ||||||

| Qz IIIa | 7 | VL | 315–364 | −6.0–−5.5 | −0.1 | |

| 331 | ||||||

| Gold–telluride–quartz | Qz IVa | 10 | VL | 175–325 | −8.0–−5.5 | −1.1–−1.0 |

| 280 | ||||||

| Northern part | ||||||

| Telluride–sulfide–quartz | Qz IIb | 9 | VL | 219–248 | −6.0–−5.0 | −0.5–−0.2 |

| 233 | ||||||

| Adularia–carbonate–quartz | Qz IIIb | 20 | VL | 140–214 | −7.0–−5.0 | −0.4–−0.1 |

| 183 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhegunov, P.S.; Smirnov, S.Z.; Shaparenko, E.O.; Ozerov, A.Y.; Scholz, R. Fluid Inclusion Constraints on the Formation Conditions of the Evevpenta Au–Ag Epithermal Deposit, Kamchatka, Russia. Minerals 2025, 15, 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111196

Zhegunov PS, Smirnov SZ, Shaparenko EO, Ozerov AY, Scholz R. Fluid Inclusion Constraints on the Formation Conditions of the Evevpenta Au–Ag Epithermal Deposit, Kamchatka, Russia. Minerals. 2025; 15(11):1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111196

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhegunov, Pavel S., Sergey Z. Smirnov, Elena O. Shaparenko, Alexey Yu. Ozerov, and Ricardo Scholz. 2025. "Fluid Inclusion Constraints on the Formation Conditions of the Evevpenta Au–Ag Epithermal Deposit, Kamchatka, Russia" Minerals 15, no. 11: 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111196

APA StyleZhegunov, P. S., Smirnov, S. Z., Shaparenko, E. O., Ozerov, A. Y., & Scholz, R. (2025). Fluid Inclusion Constraints on the Formation Conditions of the Evevpenta Au–Ag Epithermal Deposit, Kamchatka, Russia. Minerals, 15(11), 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111196