Volatile Chalcophile Elements in Native Sulfur from a Submarine Hydrothermal System at Kueishantao, Offshore NE Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Samples and Analytical Methods

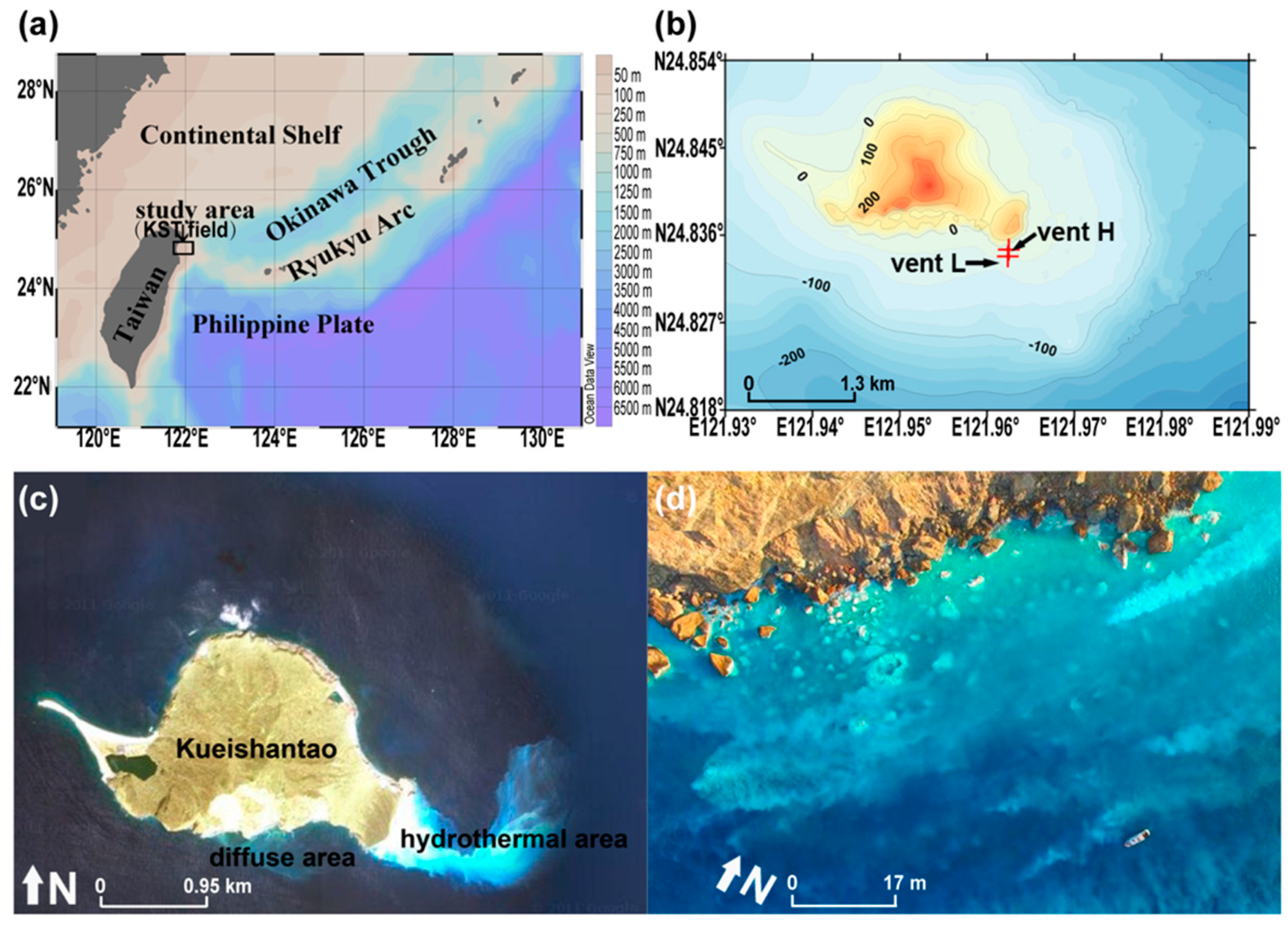

2.1. Geological Setting

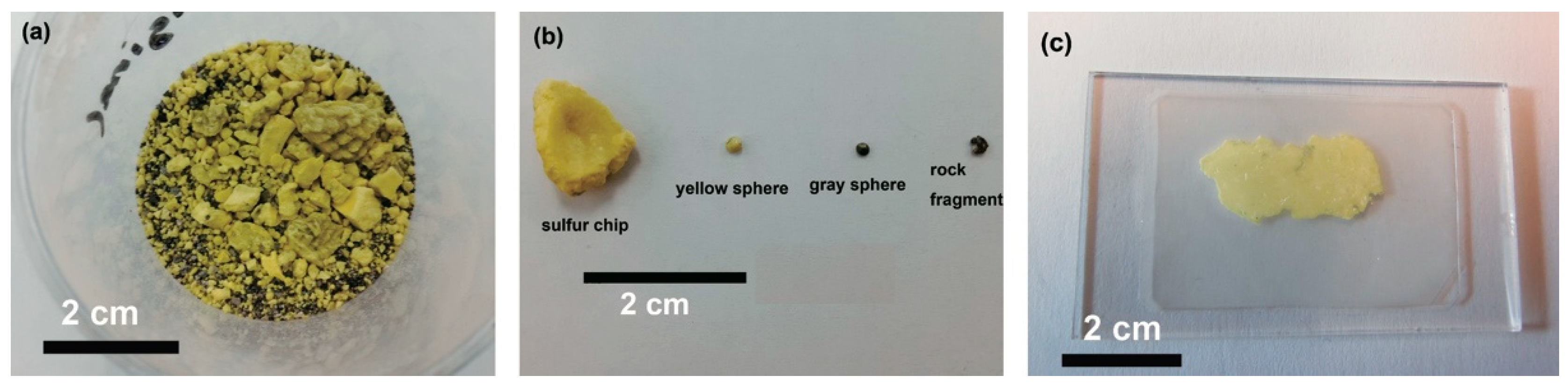

2.2. Sample Collection and Description

2.3. Analytical Methods

- (1)

- The isotope counts-per-second (CPS) abundance of each element was calculated by subtracting the background value from the signal value of the isotope;

- (2)

- Assuming that the isotope abundance of the element in the sample is the same as its natural abundance, the CPS value of the element was calculated by the following formula:where elementCPS is the CPS value of the element in the sample, isotopeCPS is the isotope CPS value of the element in the sample, isotopena is the natural isotope abundance of the element;

- (3)

- Assuming that the fractionation of elements during the tests could be ignored and the relative ablation yield is comparable for all elements, the element concentration in the sample was calculated by the following formula:where Cel is the element concentration in the sample, ∑elementCPS is the total CPS values of all the tested elements in the sample.

3. Results

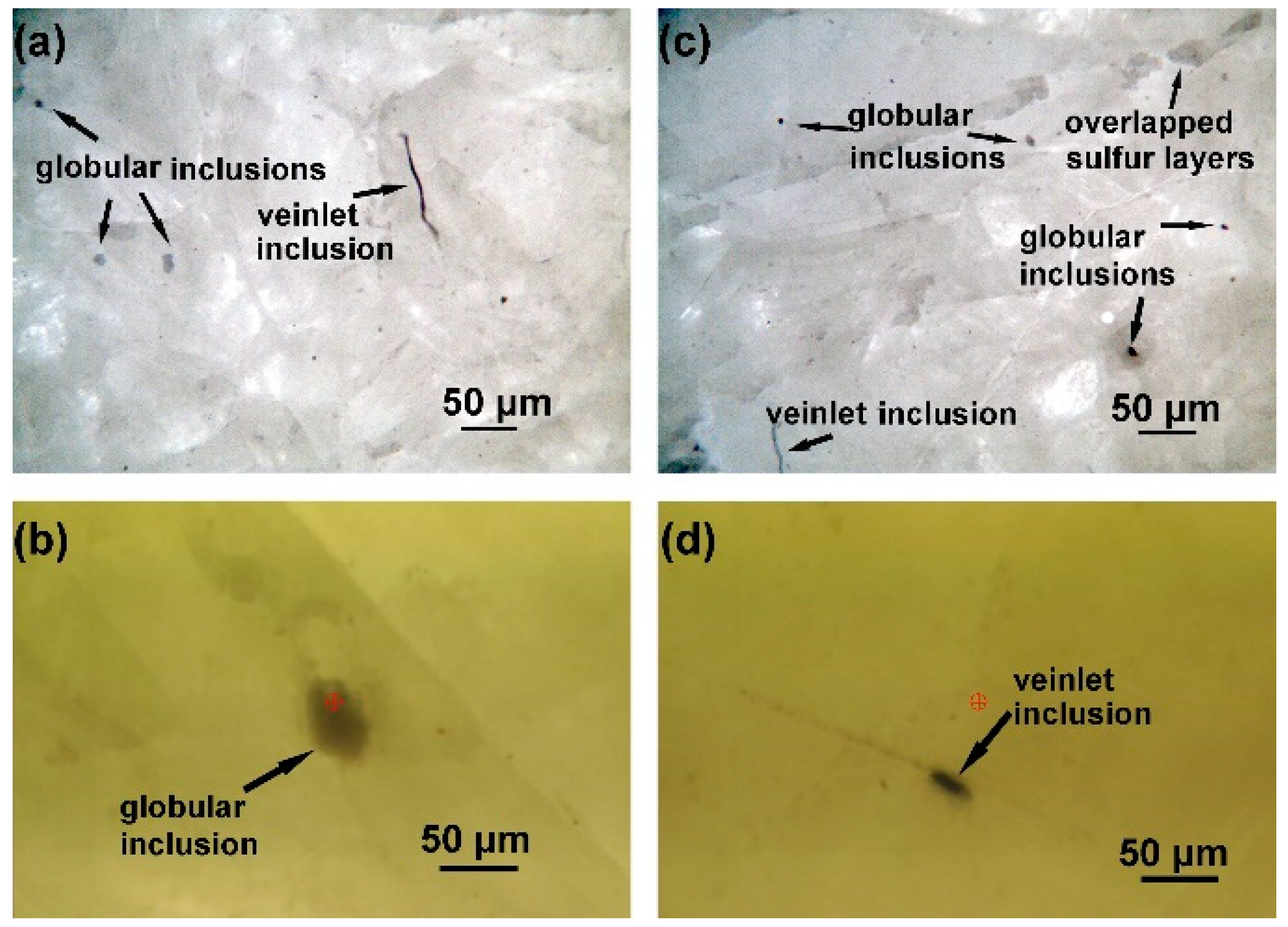

3.1. Optical Microscopy

3.2. LA-ICPMS

3.3. Sulfur Isotopes

4. Discussion

4.1. Fe, Cu, Zn and δ34S

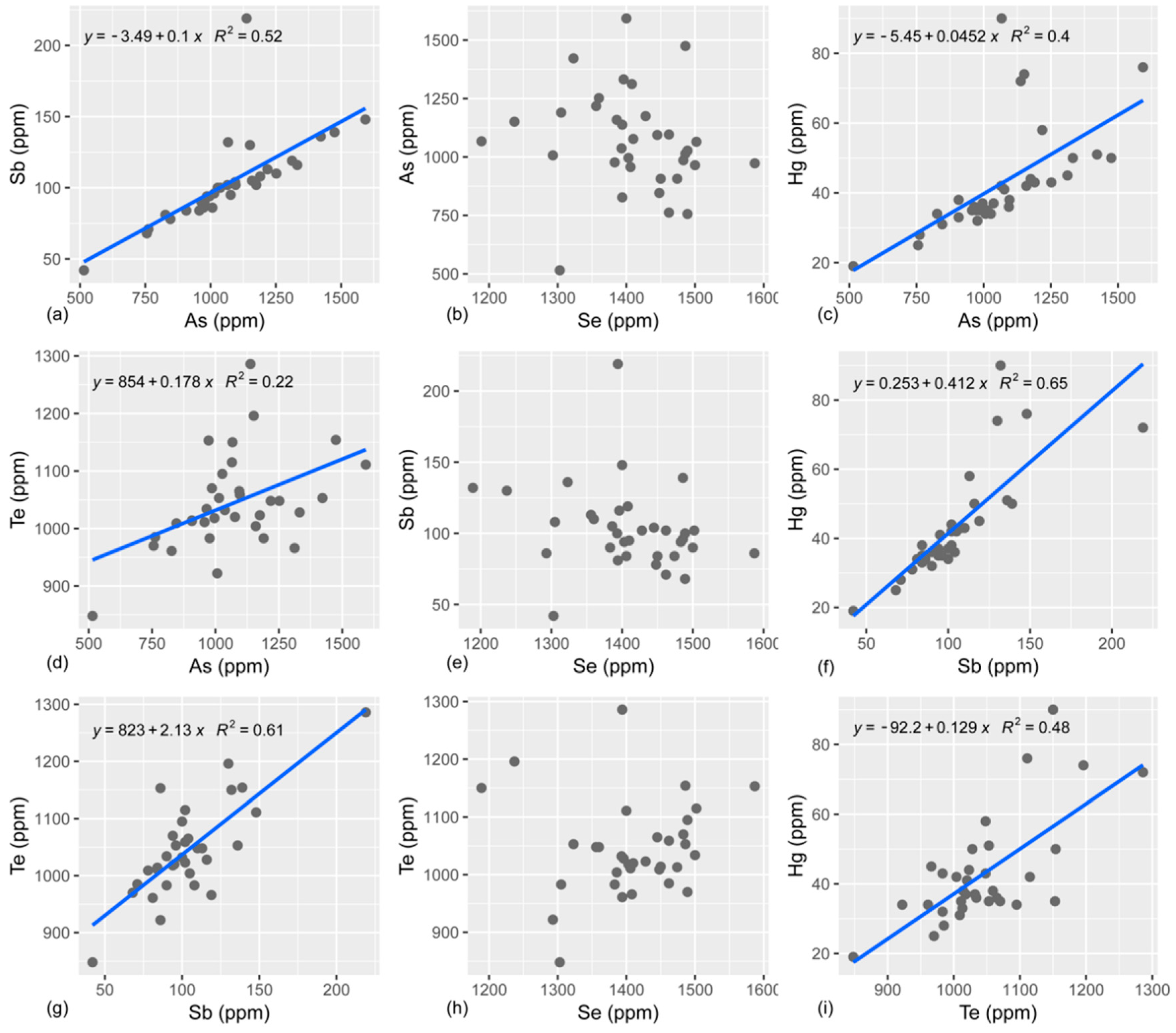

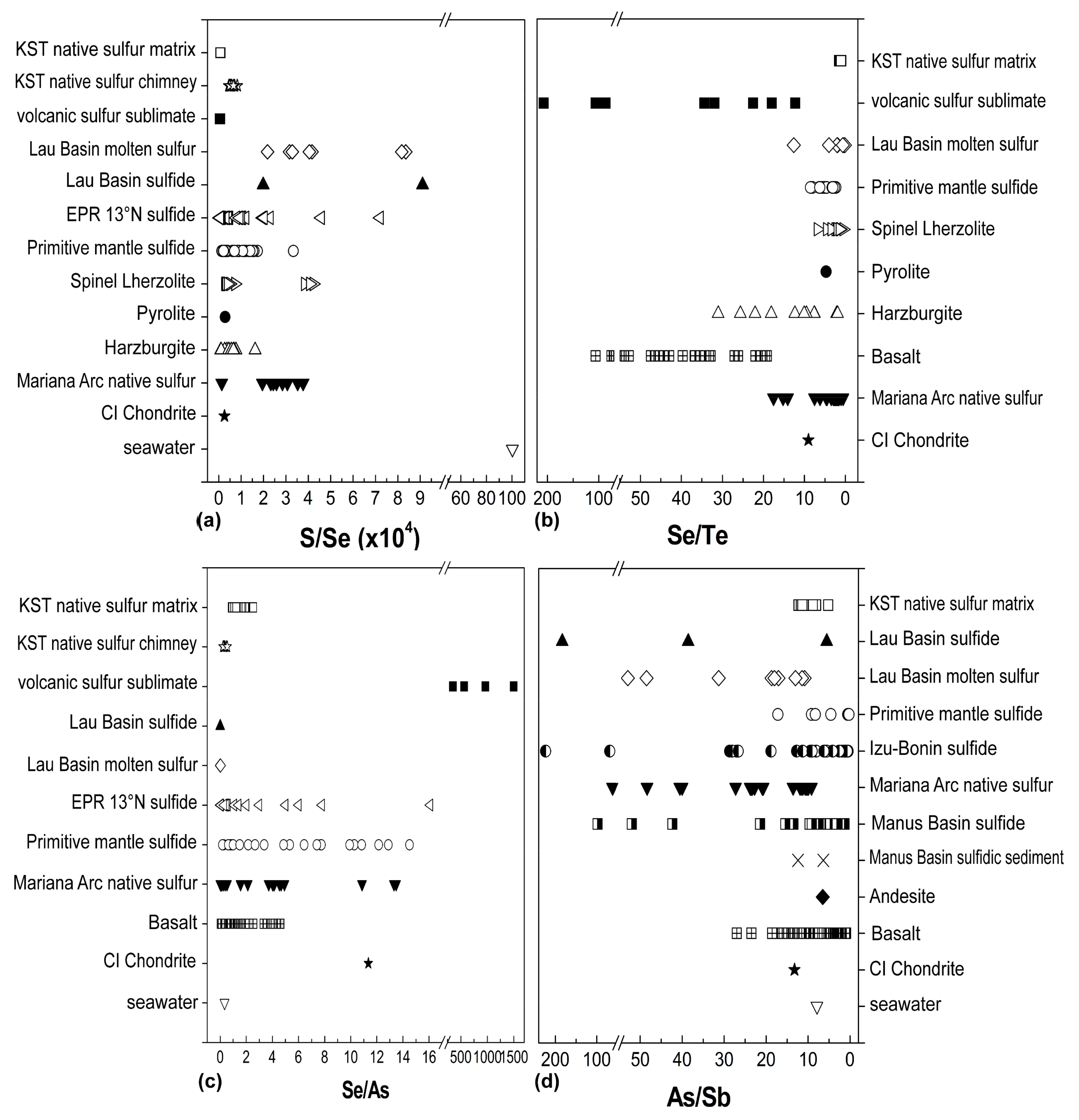

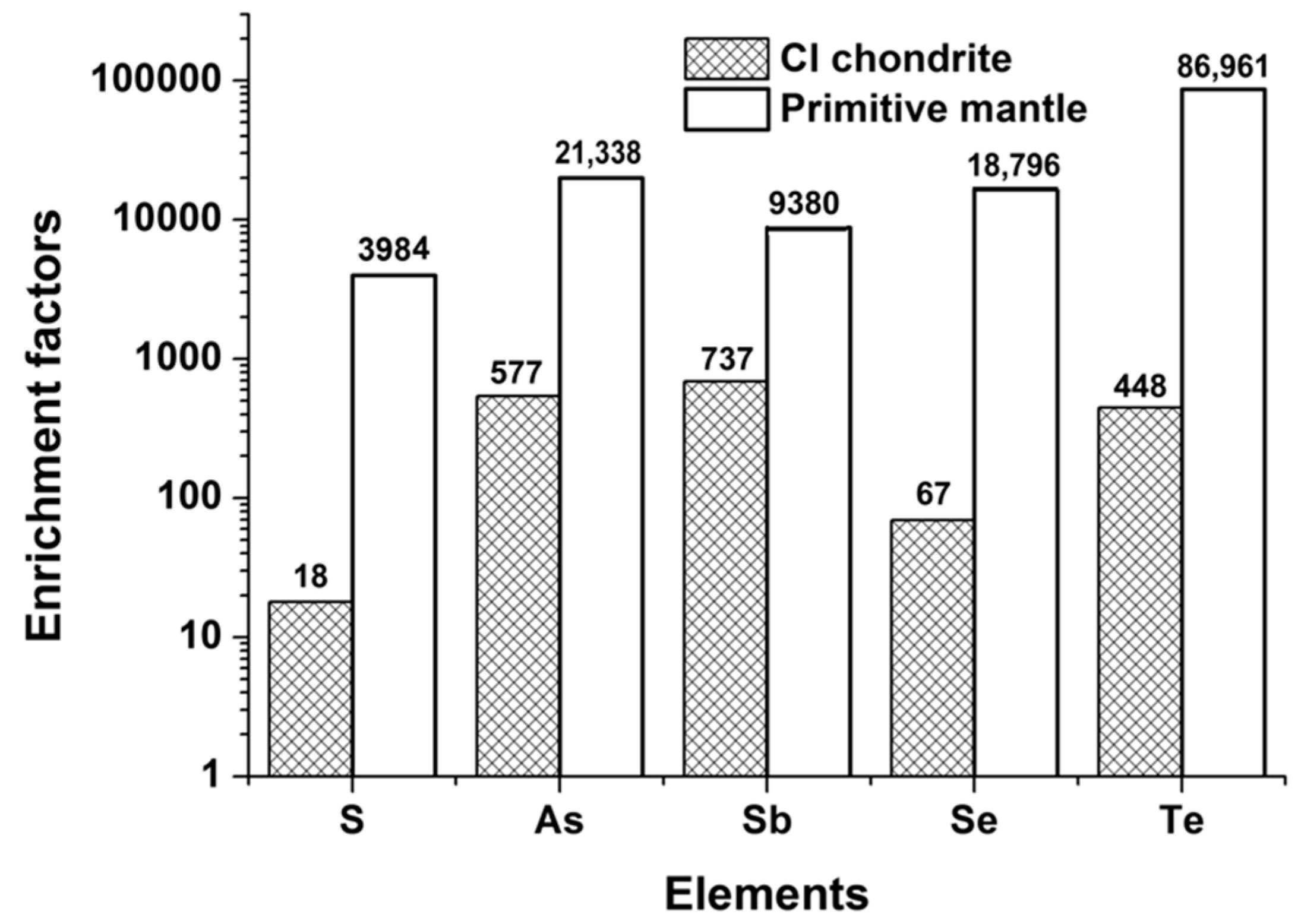

4.2. S, Se, Te, As, and Sb Systematics

4.3. Fractionation Behavior of S, Se, and Te

4.4. Fractionation of As and Sb

4.5. Formation of Native Sulfur

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goldschmidt, V.M. The principles of distribution of chemical elements in minerals and rocks. The seventh Hugo Muller Lecture, delivered before the Chemical Society on March 17th, 1937. J. Chem. Soc. (Resumed) 1937, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, H.M.; Ballhaus, C.; Wohlgemuth-Ueberwasser, C.; Fonseca, R.O.C.; Laurenz, V. Partitioning of Se, As, Sb, Te and Bi between monosulfide solid solution and sulfide melt—Application to magmatic sulfide deposits. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 6174–6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, S.; Luguet, A.; Lorand, J.-P.; Wombacher, F.; Lissner, M. Selenium and tellurium systematics of the Earth’s mantle from high precision analyses of ultra-depleted orogenic peridotites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 86, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.F.; Sun, S.S. The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 1995, 120, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.W. Ultramafic xenoliths: Clues to Earth′s late accretionary history. J. Geophys. Res. 1986, 91, 12375–12387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, F.; Layana, S.; Rodríguez-Díaz, A.; González, C.; Cortés, J.; Inostroza, M. Hydrothermal alteration, fumarolic deposits and fluids from Lastarria Volcanic Complex: A multidisciplinary study. Andean Geol. 2016, 43, 166–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevko, E.P.; Bortnikova, S.B.; Abrosimova, N.A.; Kamenetsky, V.S.; Bortnikova, S.P.; Panin, G.L.; Zelenski, M. Trace Elements and Minerals in Fumarolic Sulfur: The Case of Ebeko Volcano, Kuriles. Geofluids 2018, 2018, 4586363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucker, V.K.; Walker, S.L.; de Ronde, C.E.J.; Tontini, F.C.; Tsuchida, S. Hydrothermal Venting at Hinepuia Submarine Volcano, Kermadec Arc: Understanding Magmatic-Hydrothermal Fluid Chemistry. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 2017, 18, 3646–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekov, V.M.; Petersen, S.; Garbe-Schönberg, D.; Kamenov, G.D.; Perner, M.; Kuzmann, E.; Schmidt, M. Fe–Si-oxyhydroxide deposits at a slow-spreading centre with thickened oceanic crust: The Lilliput hydrothermal field (9°33′S, Mid-Atlantic Ridge). Chem. Geol. 2010, 278, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschinsky, A.; Garbe-Schönberg, C.D.; Sander, S.; Schmidt, K.; Gennerich, H.-H.; Strauss, H. Hydrothermal venting at pressure-temperature conditions above the critical point of seawater, 5°S on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geology 2008, 36, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ronde, C.E.J.; Hannington, M.D.; Stoffers, P.; Wright, I.C.; Ditchburn, R.G.; Reyes, A.G.; Baker, E.T.; Massoth, G.J.; Lupton, J.E.; Walker, S.L.; et al. Evolution of a submarine magmatic- hydrothermal system: Brothers volcano, southern Kermadec arc, New Zealand. Econ. Geol. 2005, 100, 1097–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ronde, C.E.J.; Massoth, G.J.; Butterfield, D.A.; Christenson, B.W.; Ishibashi, J.; Ditchburn, R.G.; Hannington, M.D.; Brathwaite, R.L.; Lupton, J.E.; Kamenetsky, V.S.; et al. Submarine hydrothermal activity and gold-rich mineralization at Brothers volcano, Kermadec arc, New Zealand. Miner. Depos. 2011, 46, 541–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorand, J.-P.; Alard, O. Determination of selenium and tellurium concentrations in Pyrenean peridotites (Ariege, France): New insight into S/Se/Te systematics of the upper in mantle samples. Chem. Geol. 2010, 278, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouxel, O.; Fouquet, Y.; Ludden, J.N. Subsurface processes at the lucky strike hydrothermal field, Mid-Atlantic ridge: Evidence from sulfur, selenium, and iron isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2004, 68, 2295–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkenbosch, H.A.; de Ronde, C.E.J.; Gemmell, J.B.; McNeill, A.W.; Goemann, K. Mineralogy and formation of black smoker chimneys from Brothers submarine volcano, Kermadec arc. Econ. Geol. 2012, 107, 1613–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquet, Y.; Auclair, G.; Cambon, P.; Etoubleau, J. Geological setting and mineralogical and geochemical investigations on sulfide deposits near 13°N on the East Pacific Rise. Mar. Geol. 1988, 84, 145–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquet, Y.; Pelleter, E.; Konn, G.; Chazot, G.; Dupré, S.; Alix, A.S.; Chéron, S.; Donval, J.P.; Guyader, V.; Etoubleau, J.; et al. Volcanic and hydrothermal processes in submarine calderas: The Kulo Lasi T example (SW Pacific). Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 99, 314–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeats, C.J.; Parr, J.M.; Binns, R.A.; Gemmell, J.B.; Scott, S.D. The SuSu Knolls Hydrothermal Field, Eastern Manus Basin, Papua New Guinea: An Active Submarine High-Sulfidation Copper-Gold System. Econ. Geol. 2014, 109, 2207–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, J.H. Metal-bearing molten sulfur collected from a submarine volcano: Implications for vapor transport of metals in seafloor hydrothermal systems. Geology 2011, 39, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ronde, C.E.J.; Chadwick, W.W., Jr.; Ditchburn, R.G.; Embley, R.W.; Tunnicliffe, V.; Baker, E.T.; Wallker, S.L.; Ferrini, V.L.; Merle, S.M. Molten Sulfur Lakes of Intraoceanic Arc Volcanoes. In Volcanic Lakes. Advances in Volcanology; Rouwet, D., Christenson, B., Tassi, F., Vandemeulebrouck, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 261–288. ISBN 978-3-642-36832-5. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland, L.P.; Aruscavage, P. Volcanic Emission of Se, Te, and as from Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1986, 27, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letouzey, J.; Kimura, M. The okinawa trough: Genesis of a back-arc basin developing along a continental margin. Tectonophysics 1986, 125, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Wu, W.S.; Chen, C.H.; Liu, T.K. A date for volcanic eruption inferred from a siltstone xenolith. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2001, 20, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.G.; Lyu, S.S.; Garbe-Schönberg, D.; Lebrato, M.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, P.P.; Chen, C.T.A.; Ye, Y. Heavy metals from Kueishantao shallow-sea hydrothermal vents, offshore northeast Taiwan. J. Mar. Syst. 2018, 180, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T.A.; Wang, B.J.; Huang, J.F.; Lou, J.Y.; Kuo, F.W.; Tu, Y.Y.; Tsai, H.S. Investigation into extremely acidic hydrothermal fluids off Kueishan Tao, Taiwan, China. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2005, 24, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T.A.; Zeng, Z.G.; Kuo, F.W.; Yang, T.Y.F.; Wang, B.J.; Tu, Y.Y. Tide-influenced acidic hydrothermal system offshore NE Taiwan. Chem. Geol. 2005, 224, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Damm, K.L. Seafloor hydrothermal activity—Black smoker chemistry and chimneys. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1990, 18, 173–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Nakamura, K.; Takano, B.; Lilley, M.D.; Lupton, J.E.; Resing, J.A.; Roe, K.K. High SO2 flux, sulfur accumulation, and gas fractionation at an erupting submarine volcano. Geology 2011, 39, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeats, C.J.; Hollis, S.P.; Halfpenny, A.; Corona, J.C.; LaFlamme, C.; Southam, G.; Fiorentini, M.; Herrington, R.J. Actively forming Kuroko-type volcanic-hosted massive sulfide (VHMS) mineralization at Iheya North, Okinawa Trough, Japan. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 84, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.G.; Chen, C.T.A.; Yin, X.B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, G.L.; Wang, X.M.; Chen, D.G. Origin of native sulfur ball from the Kueishantao hydrothermal field offshore northeast Taiwan: Evidence from trace and rare earth element composition. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 40, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B. Solid allotropes of sulfur. Chem. Rev. 1964, 64, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargel, J.S.; Delmelle, P.; Nash, D.B. Volcanogenic sulfur on Earth and Io: Composition and spectroscopy. Icarus 1999, 142, 249–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.L.; Song, S.R.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Chen, C.X. Volcanic characteristics of Kueishantao in northeast Taiwan and their implications. Terr. Atmos. Ocean Sci. 2010, 21, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe-Schönberg, D.; Müller, S. Nano-particulate pressed powder tablets for LA-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2014, 29, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, A.V.; Asafov, E.V.; Gurenko, A.A.; Arndt, N.T.; Batanova, V.G.; Portnyagin, M.V.; Garbe- Schönberg, D.; Krasheninnikov, S.P. Komatiites reveal a hydrous Archaean deep-mantle reservoir. Nature 2016, 531, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbe-Schönberg, C.D. Simultaneous Determination of Thirty-Seven Trace Elements in Twenty-Eight International Rock Standards by ICP-MS. Geostand. Newsl. 1993, 17, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.G.; Qiu, Z.Y.; Duan, W.; Li, X.H.; Ye, Y.; Chen, C.T.A. Elemental Enrichment in the Microscopic Inclusions of the Native Sulfur from Kueishantao Hydrothermal System, Taiwan, China. Earth Sci. 2018, 43, 1549–1561. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.G.; Liu, C.H.; Chen, C.T.A.; Yin, X.B.; Chen, D.G.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, X.M.; Zhang, G.L. Origin of a native sulfur chimney in the Kueishantao hydrothermal field, offshore northeast Taiwan. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2007, 50, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasby, G.P.; Iizasa, K.; Hannington, M.; Kubota, H.; Notsu, K. Mineralogy and composition of Kuroko deposits from northeastern Honshu and their possible modern analogues from the Izu-Ogasawara (Bonin) Arc south of Japan: Implications for mode of formation. Ore Geol. Rev. 2008, 34, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Wang, X.M.; Zeng, Z.G.; Yin, X.B.; Chen, C.T.A.; Zhang, S.W. Origin of the hydrothermal fluid of the shallow sea near Kueishantao Island. Mar. Sci. 2010, 34, 61–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rees, C.E.; Jenkins, W.J.; Monster, J. The sulfur isotopic composition of ocean water sulfate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1978, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Fu, Z.H.; Yin, X.B. The seawater influence on sulfur isotopic evolution within modern seafloor hydrothermal chimneys. Mar. Sci. 2006, 30, 90–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet, Y.; Vonstackelberg, U.; Charlou, J.L.; Donval, J.P.; Erzinger, J.; Herzig, P.; Muhe, R.; Wiedicke, M.; Soakai, S.; Whitechurch, H. Hydrothermal activity in the lau back-arc basin-sulfides and water chemistry. Geology 1991, 19, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulignati, P.; Sbrana, A. Presence of native gold and tellurium in the active high-sulfidation hydrothermal system of the La Fossa volcano (Vulcano, Italy). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1998, 86, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, K.H.; Arai, S.; Clarke, D.B. Selenium, tellurium, arsenic and antimony contents of primary mantle sulfides. Can. Mineral. 2002, 40, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertogen, J.; Janssens, M.J.; Palme, H. Trace elements in ocean ridge basalt glasses: Implications for fractionations during mantle evolution and petrogenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1980, 44, 2125–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H.; Des Marais, D.J.; Ueda, A.; Moore, J.G. Concentrations and isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in ocean-floor basalts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1984, 48, 2433–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, W.C. Stable isotopes in seafloor hydrothermal systems: Vent fluids, hydrothermal deposits, hydrothermal alteration, and microbial processes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2001, 43, 469–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giggenbach, W.F. Redox potential governing the chemistry of fumarolic gas discharges from White Island, New Zealand. Appl. Geochem. 1987, 2, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Yang, T.F.; Chen, C.T.A.; Chen, X.G.; Qin, H.W.; Jin, A.M.; Ding, Q.; Pan, Y.W.; Xia, M.S.; Ye, Y. Gas composition of submarine hydrothermal systems off Guishandao and in coastal hot springs off Lüdao in Taiwan. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2013, 32, 50–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janecky, D.R.; Shanks, W.C. Computational modeling of chemical and sulfur isotopic reaction processes in seafloor hydrothermal systems: Chimneys, massive sulfides, and subjacent alteration zones. Can. Mineral. 1988, 26, 805–825. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, J.L.; Nicewander, W.A. Thirteen Ways to Look at the Correlation Coefficient. Am. Stat. 1988, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.J.; Joseph, E.P. Extreme alteration in an acid-sulphate geothermal field: Sulphur Springs, Saint Lucia. Chem. Geol. 2018, 500, 103–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Weston, L.; Brenan, J.M.; Fei, Y.; Secco, R.A.; Frost, D.J. Effect of pressure, temperature, and oxygen fugacity on the metal-silicate partitioning of Te, Se, and S: Implications for earth differentiation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 4598–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floor, G.H.; Román-Ross, G. Selenium in volcanic environments: A review. Appl. Geochem. 2012, 27, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, M.; Smith, D.J.; Jenkin, G.R.T.; Holwell, D.A.; Dye, M.D. A review of Te and Se systematics in hydrothermal pyrite from precious metal deposits: Insights into ore-forming processes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 96, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornadel, A.P.; Spry, P.G.; Haghnegahdar, M.A.; Schauble, E.A.; Jackson, S.E.; Mills, S.J. Stable Te isotope fractionation in tellurium-bearing minerals from precious metal hydrothermal ore deposits. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 202, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, R.S.J. Dynamics of magma degassing. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2003, 213, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Colling, A. Seawater: Its Composition Properties and Behaviour, 2nd ed.; Bearman, G., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinmann: Oxford, UK, 1989; ISBN 978-1-4832-5707-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lissner, M.; Konig, S.; Luguet, A.; le Roux, P.J.; Schuth, S.; Heuser, A.; le Roex, A.P. Selenium and tellurium systematics in MORBs from the southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge (47–50°S). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 144, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, F.E.; O’Neill, H.S. Analysis of 60 elements in 616 ocean floor basaltic glasses. Geochem. Geophy. Geos. 2012, 13, Q02005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Humayun, M.; Salters, V.J.M. Elemental Systematics in MORB Glasses from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochem. Geophy. Geos. 2018, 19, 4236–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Jones, A.E.; Heinrich, C.A. Vapor transport of metals and the formation of magmatic-hydrothermal ore deposits. Econ. Geol. 2005, 100, 1287–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, C.; Stevenson, D. Liquid sulfur lakes at Poas volcano. Nature 1989, 342, 790–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Strauss, H.; Petersen, S.; Kummer, N.-A.; Thomazo, C. Hydrothermalism in the Tyrrhenian Sea: Inorganic and microbial sulfur cycling as revealed by geochemical and multiple sulfur isotope data. Chem. Geol. 2011, 280, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.W. Preliminary Investigation of the Hydrothermal Activities off Kueishantao Island. Master’s Thesis, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2011. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- McPhail, D.C. Thermodynamic properties of aqueous tellurium species between 25 and 350 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1995, 59, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Guillong, M.; Heinrich, C.A. The role of sulfur in the formation of magmatic–hydrothermal copper–gold deposits. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 282, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Al | S (%) | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | As | Se | Sb | Te | Ba | La | Ce | Hg | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 902 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 986 | 1483 | 94 | 1070 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | n.d. | 35 | b.d.l. |

| 907 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 226 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1027 | 1489 | 100 | 1095 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 34 | b.d.l. |

| 908 | 99 | 99.5 | 6 | 170 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1475 | 1486 | 139 | 1154 | b.d.l. | n.d. | b.d.l. | 50 | b.d.l. |

| 909 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1094 | 1445 | 104 | 1065 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 36 | b.d.l. |

| 910 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1037 | 1393 | 100 | 1032 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 37 | b.d.l. |

| 911 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 996 | 1403 | 94 | 1018 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | n.d. | 37 | b.d.l. |

| 912 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | b.d.l. | 29 | b.d.l. | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 965 | 1500 | 90 | 1034 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 36 | b.d.l. |

| 913 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 907 | 1474 | 84 | 1013 | b.d.l. | n.d. | b.d.l. | 33 | b.d.l. |

| 914 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | b.d.l. | 11 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1096 | 1462 | 102 | 1059 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 38 | b.d.l. |

| 915 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | b.d.l. | 33 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1014 | 1486 | 96 | 1053 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 35 | b.d.l. |

| 916 | b.d.l. | 99.7 | n.d. | b.d.l. | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 756 | 1489 | 68 | 970 | n.d. | n.d. | b.d.l. | 25 | b.d.l. |

| 917 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | b.d.l. | 186 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 762 | 1462 | 71 | 985 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 28 | b.d.l. |

| 918 | b.d.l. | 99.7 | n.d. | 23 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 827 | 1394 | 81 | 961 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | n.d. | 34 | b.d.l. |

| 919 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 11 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 907 | 1450 | 84 | 1014 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 38 | b.d.l. |

| 920 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | b.d.l. | 606 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1065 | 1502 | 102 | 1115 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 42 | b.d.l. |

| 921 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 23 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1218 | 1356 | 113 | 1048 | n.d. | b.d.l. | n.d. | 58 | b.d.l. |

| 922 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 29 | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1593 | 1400 | 148 | 1111 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | n.d. | 76 | n.d. |

| 923 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1077 | 1410 | 95 | 1020 | n.d. | n.d. | b.d.l. | 41 | n.d. |

| 924 | 56 | 99.5 | 8 | 1327 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 846 | 1448 | 78 | 1009 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 31 | b.d.l. |

| 925 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 17 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1190 | 1305 | 108 | 983 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 43 | b.d.l. |

| 926 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 22 | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1159 | 1386 | 105 | 1004 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 42 | b.d.l. |

| 927 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 6 | b.d.l. | 1175 | 1428 | 102 | 1023 | n.d. | n.d. | b.d.l. | 44 | b.d.l. |

| 928 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 23 | n.d. | b.d.l. | 12 | b.d.l. | 957 | 1406 | 84 | 1011 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 35 | b.d.l. |

| 929 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1332 | 1396 | 116 | 1028 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 50 | b.d.l. |

| 930 | 23 | 99.6 | b.d.l. | 126 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1422 | 1323 | 136 | 1053 | b.d.l. | n.d. | b.d.l. | 51 | b.d.l. |

| 931 | b.d.l. | 99.7 | n.d. | n.d. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 515 | 1303 | 42 | 848 | n.d. | n.d. | b.d.l. | 19 | b.d.l. |

| 933 | 55 | 99.5 | b.d.l. | 836 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 973 | 1587 | 86 | 1153 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 35 | b.d.l. |

| 934 | 30 | 99.6 | b.d.l. | 89 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 5 | b.d.l. | 977 | 1383 | 90 | 983 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 32 | b.d.l. |

| 935 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 14 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1312 | 1408 | 119 | 966 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 45 | b.d.l. |

| 936 | b.d.l. | 99.7 | n.d. | 41 | b.d.l. | 6 | 6 | b.d.l. | 1007 | 1293 | 86 | 922 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 34 | b.d.l. |

| 937 | b.d.l. | 99.6 | n.d. | 62 | n.d. | b.d.l. | 8 | b.d.l. | 1252 | 1360 | 110 | 1048 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 43 | b.d.l. |

| 004 | 31 | 99.4 | 9 | 2103 | 5 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1067 | 1189 | 132 | 1150 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 90 | b.d.l. |

| 005 | 12 | 99.6 | b.d.l. | 26 | b.d.l. | 86 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 1151 | 1237 | 130 | 1196 | b.d.l. | n.d. | n.d. | 74 | n.d. |

| 006 | 8 | 99.5 | b.d.l. | n.d. | 7 | b.d.l. | b.d.l. | 9 | 1138 | 1394 | 219 | 1286 | b.d.l. | 5.0 | 50.5 | 72 | b.d.l. |

| Samples | S (%) | As (ppm) | Se (ppm) | Te (ppm) | Sb (ppm) | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| native sulfur matrix from Kueishantao area | 99.54–99.67 (99.63) | 756–1475(995) | 1389–1496(1454) | 961–1155(1041) | 70–143(97) | this study |

| native sulfur chimney from Kueishantao area | 98.63–99.13(98.91) | 360–890(585) | 120–220(183) | b.d.l. | n.d. | [42] |

| Mariana Arc native sulfur | 51.1–99.5(82.6) | <0.5–1520(348) | 22–1140(415) | 1.6–>500(155) | <0.1–128(25) | [20] |

| Lau basin molten sulfur | 13.74–19.93(16.9) | 252–641(421) | 4.4–6.3(5.4) | 0.5–3.3(1.8) | 22.0–34.3(28.2) | [19] |

| Lau basin chimney | 13.34–18.38(16.7) | 160–723(350) | 1.3–4.2(2.3) | 5.3–7.9(6.5) | 3.3–23.1(14.2) | |

| Lau basin sulfide | 18.21–43.64(30.12) | 473–4586(2213) | 0–22(8) | n.d. | 25–86(51) | [43] |

| East Pacific Rise (EPR) 13°N sulfide | 25.5–51.0(35.12) | 0–1253(154) | 0–1095(163) | n.d. | n.d. | [16] |

| Sunrise hydrothermal sulfide | n.d. | 360–8460(3050) | n.d. | 0.2–25(5.9) | 5.3–8020(2037) | [39] |

| Kuroko deposit | n.d. | 70–22,900(4348) | n.d. | b.d.l.–15.0 | 9–16,800(1625) | |

| Suiyo Seamount deposit | n.d. | 16–6920(2122) | n.d. | b.d.l.–4.3 | 2.9–1650(450) | |

| hydrothermally altered rocks at La Fossa volcano | 6.59 | 746 | n.d. | 75 | <5 | [44] |

| spinel lherzolites | 50–210 (98) ppm | n.d. | 1.3–63(26.1) ppb | <2–18(11.6) ppb | n.d. | [5] |

| Harzburgites from Lherz | 0.5–10.0(2.9) | n.d. | 1.76–11.54(5.5) | 0.200–3.2(0.8) | n.d. | [3] |

| primitive mantle sulfides | 36.4 | 0–670(30) | 21–280(109) | b.d.l.–44 | b.d.l.–146 | [45] |

| primitive mantle | 250 ppm | 0.05 | 0.075 | 0.012 | 0.14 | [4] |

| Mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB) from active spreading center | n.d. | n.d. | 103–335(204.8) ppb | 0.97–17.3(6.95) ppb | 2.23–74.2(16.7) ppb | [46] |

| CI Carbonaceous chondrites | 5.40 | 1.85 | 21 | 2.33 | 140 | [4] |

| endmenber fluid: 21° EPR | H2S 224–285 ppm | 2.25–34 ppb | <0.05–5.7 ppb | n.d. | n.d. | [27] |

| endmenber fluid: Guaymas | H2S 129–204 ppm | 20–80 ppb | 3–8 ppb | n.d. | n.d. | |

| volcanic gas from Kilauea volcano | 9.58–12.30 | 1.7–4.5 | 2.5–3.2 | 0.21–0.32 | n.d. | [21] |

| sulfur sublimates from Kilauea volcano | n.d. | <0.5–33.0(6.5) | 1300–2900(1975) | 14–200(60) | n.d. |

| Samples | δ34S (V-CDT‰) | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Kueishantao native sulfur | 0.2–2.4 | this study |

| Kueishantao native sulfur chimney | −0.5–2.0 | [26,38] |

| Kueishantao hydrothermal sulfide | 22.4–31.3 | [40] |

| Kueishantao hydrothermal sulfate | 16.3–19.7 | |

| Mariana Arc native sulfur | −9.0–(−6.2) | [20] |

| Manus Basin native sulfur | −7.4–(−0.3) | [18] |

| Lucky Strike hydrothermal sulfide | −0.5–4.6 | [14] |

| MORB | −0.6–0.9 | [47] |

| seawater | 20.9 | [41] |

| Element | S | As | Sb | Se |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | −0.313 | - | - | - |

| Sb | −0.512 a | 0.718 a | - | - |

| Se | −0.003 | −0.145 | −0.234 | - |

| Te | −0.687 a | 0.466 a | 0.778 a | 0.084 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, M.-Z.; Chen, X.-G.; Garbe-Schönberg, D.; Ye, Y.; Chen, C.-T.A. Volatile Chalcophile Elements in Native Sulfur from a Submarine Hydrothermal System at Kueishantao, Offshore NE Taiwan. Minerals 2019, 9, 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9040245

Yu M-Z, Chen X-G, Garbe-Schönberg D, Ye Y, Chen C-TA. Volatile Chalcophile Elements in Native Sulfur from a Submarine Hydrothermal System at Kueishantao, Offshore NE Taiwan. Minerals. 2019; 9(4):245. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9040245

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Ming-Zhen, Xue-Gang Chen, Dieter Garbe-Schönberg, Ying Ye, and Chen-Tung Arthur Chen. 2019. "Volatile Chalcophile Elements in Native Sulfur from a Submarine Hydrothermal System at Kueishantao, Offshore NE Taiwan" Minerals 9, no. 4: 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9040245

APA StyleYu, M.-Z., Chen, X.-G., Garbe-Schönberg, D., Ye, Y., & Chen, C.-T. A. (2019). Volatile Chalcophile Elements in Native Sulfur from a Submarine Hydrothermal System at Kueishantao, Offshore NE Taiwan. Minerals, 9(4), 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/min9040245