1. Introduction

Feldspars are highly important in various industrial applications, such as in the production of glass and ceramics as flux agents because of their suitable alkali and alumina contents [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Technological developments necessitate the production of better-quality feldspar concentrates that industry desires. The quality of ore deposits diminishes rapidly with the increased production demands of the raw materials industry. Maintaining the quality in the production of feldspar concentrates and at the same time producing better quality product from these diminished grade deposits is a big challenge at the present time. Thus, new alternative methods need to be investigated for the production of high quality feldspar raw materials that industry requires [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

7]. The most important factors affecting marketability of the feldpar concentrates are their alkali (Na

2O and K

2O), iron (Fe

2O

3), titanium (TiO

2) and mica contents. Ceramic and glass industries require feldpars with very low contents of iron, titanium and micaceous impurities which directly affect the whiteness of fired feldspar products and thus the final quality. Therefore, removal processes for impurities and production of good quality feldpar concentrates are necessary for those industries [

6,

8,

9].

Multi-stage flotation processes are currently the most established method for the seperation of feldspar from associated minerals. Various papers have been published on the application of different reagents, for the flotation of feldspars. However, the separation schemes currently being used industrially are largely the same as those first proposed 60 years ago because the processes used are very efficient. The general circuit for commercial separation of feldspar consists of three sequential stages of flotation [

5,

7,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. To remove the micaceous minerals by flotation, long chain aliphatic amines are usually used at pH of 2.5 to 5.0. With amine type collectors, the use of fuel oil increases the selectivity of flotation. To remove the iron bearing heavy minerals, fatty acids or sulfonates are used in acidic conditions. Non-polar oils like fuel oil can be used as an auxiliary collector to enhance the removal of iron bearing minerals. The rutile, containing the main titanium mineral can be floated with the use of fatty acids at pH 4.0–6.0, petroleum sulfonates at pH 3.0–3.5 or fatty primary amine acetate at pH 2.5. Furthermore, titanium minerals can be floated with hydroxamates at pH 6.5, oleoyl sarcosine at pH 7.7 and potassium oleate at pH 7.7. In the flotation of titanium minerals containing sphene, oleic acid or its soaps or various vegetable oil soaps are successfully used. The use of alkyl succinamate together with petroleum sulfonate increases the success of flotation in the removal of heavy minerals [

5,

7,

10,

14,

15,

16,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In the third stage, feldspar is activated with fluoride ions and floated with an amine. The residual product is usually high-grade quartz.

Generally, the first processing stage of feldspar ore is to get rid of slimes which is large quantities of fine gangue minerals are generated due to either the fine-grained or the clayey nature of the ore. Some of the difficulties in fine particle flotation were identified as slime coatings, which inhibit bubble particle attachement and high reagent consumption due to an increased solid liquid interfaceial area, resulting in a low flotation recovery. Slime coatings on both valuables and air bubbles have been proposed to explain the observed reduction in flotation recovery [

23,

24,

25].

The negative effects of slimes during froth flotation for feldspar ores were also revealed by many researchers [

4,

15,

26,

27,

28]. It was stated that fine particle minerals not only effect as slime coating but also affect pulp rheology and the subsequent mineral flotation. High pulp viscosity can also change the hydrodynamics within the flotation cell, which can negatively affect the various sub-processes necessary for efficient flotation, such as gas dispersion, particle suspension, bubble–particle collision, attachment and detachment [

29].

Although particle size reduction processes depending on mineralogical structures of feldpar ores are the main cause for very finely sized particles, there are also 10–20% micaceous, ferrous and titanium silicate and oxide contents by weight affecting slime production. The fine-grained dimensions of the impurities (muscovite, iron oxides, titanium) of the feldspar’s mineralogical and petrographic structure are important for the success of the flotation process in the mica flotation cycle and the heavy mineral circuit [

19].

In feldspar flotation, the minerals causing slime formation have similar mineralogical properties to other minerals trying to be floated during the mica and and heavy mineral removal flotation stage. This causes unsuccesful selective separation and also excessive reagent consumption [

19,

27,

30,

31,

32]. For these reasons, removal of slimes for feldspar ore flotation is a necessity prior to mica and heavy mineral separation [

10,

13,

16,

19,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

Various methods have been used in an attempt to remove iron oxide slime coatings from the surfaces of both valuable and gangue mineral particles. The methods used for slime particle removal include pH control, high shear mixing, sonication or ultrasound and additions of chemical reagents, and combinations of these. The use of ultrasonic methods in mineral processing and enrichment processes has been investigated by many researchers in recent years. Especially in the presence of finely sized slimes, some application results yielded very effective results. Most of these studies were carried out on the effect of ultrasonic waves in the flotation process and revealed the effect of ultrasonic waves on the physical and physicochemical changes of the environment at different stages. In the literature, there are some studies showings that ultrasonic pretreatment can be used prior to the enrichment of ores with very finely sized slimes such as clays. This pretreatment provides significant contribution to the success of the applied mineral processing method [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48].

The introduction of ultrasonic energy into a flotation system could produce changes in the qualitative relationships in the system and cause a severe change in flotation rates. Some studies indicate that sound irradiation may change the pH values, surface tensions and oxidation-reduction potentials of flotation pulps with a certain increase in local temperature and pressure. In addition, the effects of ultrasonic waves on flotation of fine particles were investigated in some studies. In a previous study [

49], the effects of ultrasonic pre-treatment prior to colemanite flotation in order to prevent slime coatings were investigated in detail and it was determined that high concentrate grade and recovery values could be obtained after ultrasonic treatment for effective removal of clay particles. Celik et al. [

50] also investigated the effects of ultrasound on colemanite flotation for effective slime removal affecting selectivity and reagent consumption. Ozer et al. [

51] used ultrasound for clay sedimentation for achieving solid ratios during dewatering. Onal et al. [

52] also studied clay dewatering with help of ultrasound and reported that sedimentation process was positively affected, and the duration was shortened.

Some researchers also suggested that ultrasonic pre-treatment can help improve the flotation performance [

53,

54,

55]. Ultrasonic waves in water or in a pulp can initiate or significantly intensify different physicochemical phenomena, such as reduction and oxidation, activation, and surface cleaning, or even disintegrate the minerals [

56]. The use of ultrasonic treatment to enhance the beneficiation of different minerals has been extensively studied [

47,

57,

58].

Previous researchers [

40,

59,

60] indicated that modifying solid surfaces, especially physical surface cleaning by help of cavitation created by ultrasound at certain frequency and time intervals before and during flotation might cause significant changes in the adsorption of collectors on mineral surfaces. Previous studies investigated that the separate phases of the flotation process might be positively influenced by mechanical vibrations due to acoustic wave process or by the joint action of these two physical phenomena [

61]. Various studies [

62,

63] revealed that intensive ultrasonic vibrations might effectively alter the state of a material in an acoustic field, causing dispersion, coagulation and emulsification, changing the rate of dissolution and crystallisation, bringing about chemical conversions and accelerating multi-phase processes. The flotation process is mainly dependent upon the state of the mineral’s surface, thus factors which affect the state of the interface cause changes during the flotation [

64].

2. Material and Method

The representative ore samples contained albite as main constituent and coded as U1 containing low Na

2O % with high amount of impurities and U2 containing high Na

2O % and low amount of impurities. The chemical properties of the samples are given in

Table 1.

First, the samples were separately crushed, ground and classified in order to obtain feed particle size of minus 315 µm with similar operating parameters for the both conventional and ultrasonic flotation experiments. Particle size distribution of the flotation feed material is shown in

Table 2.

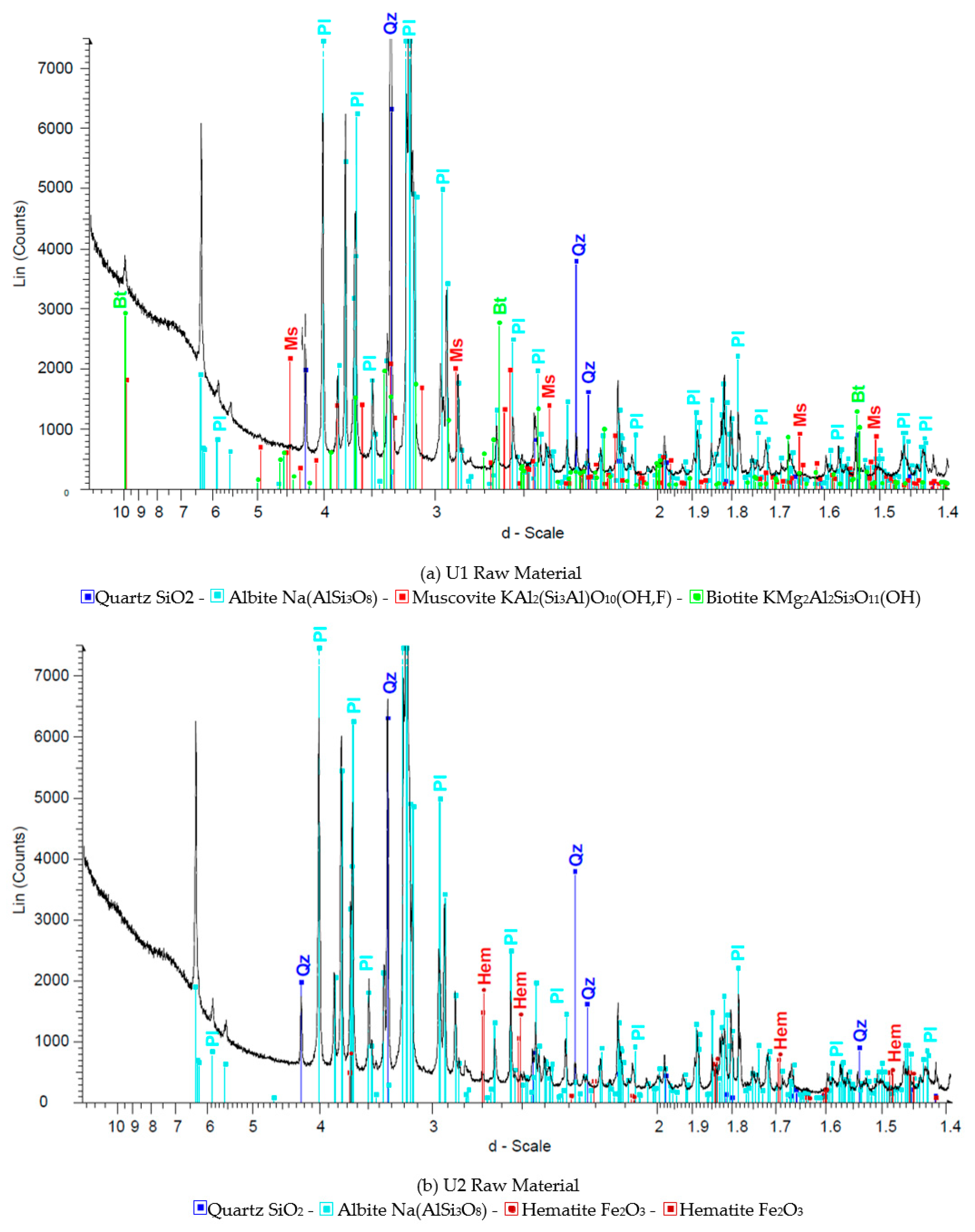

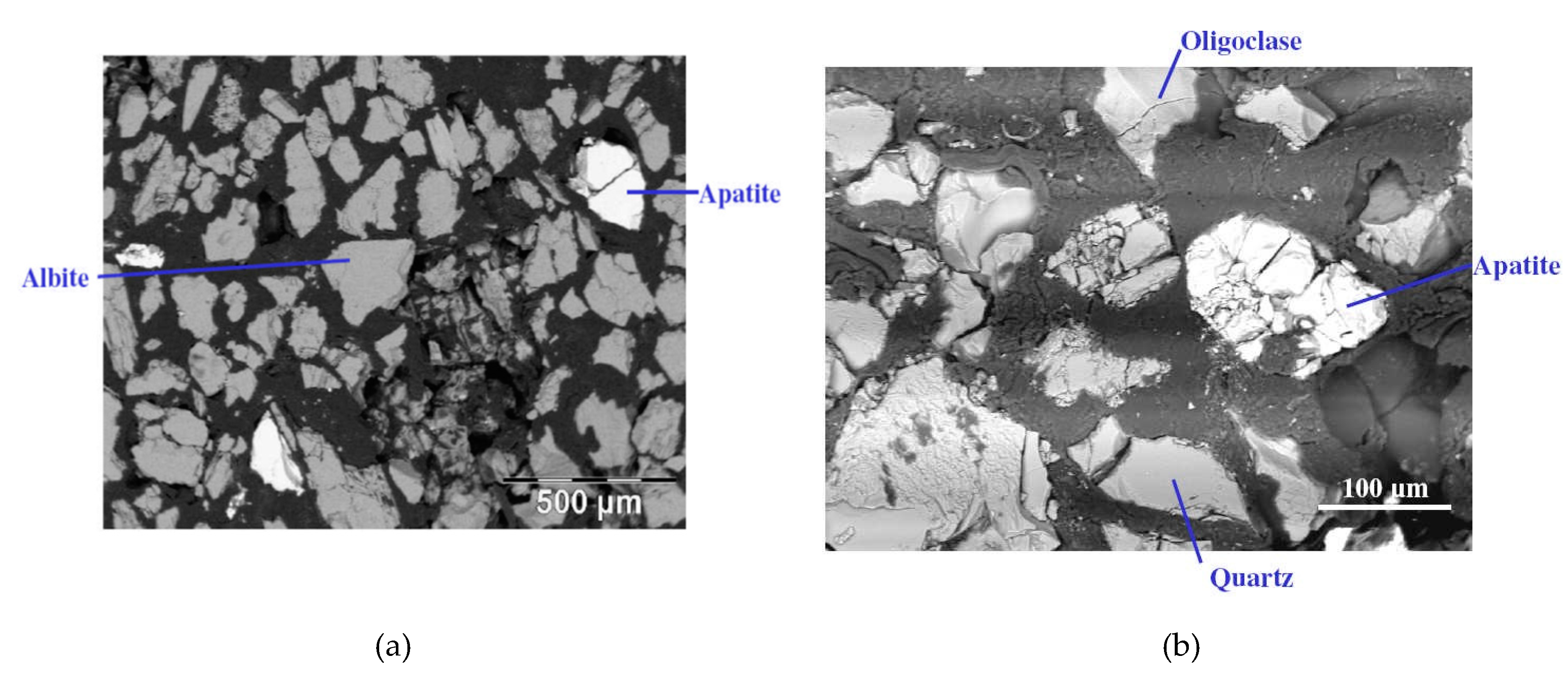

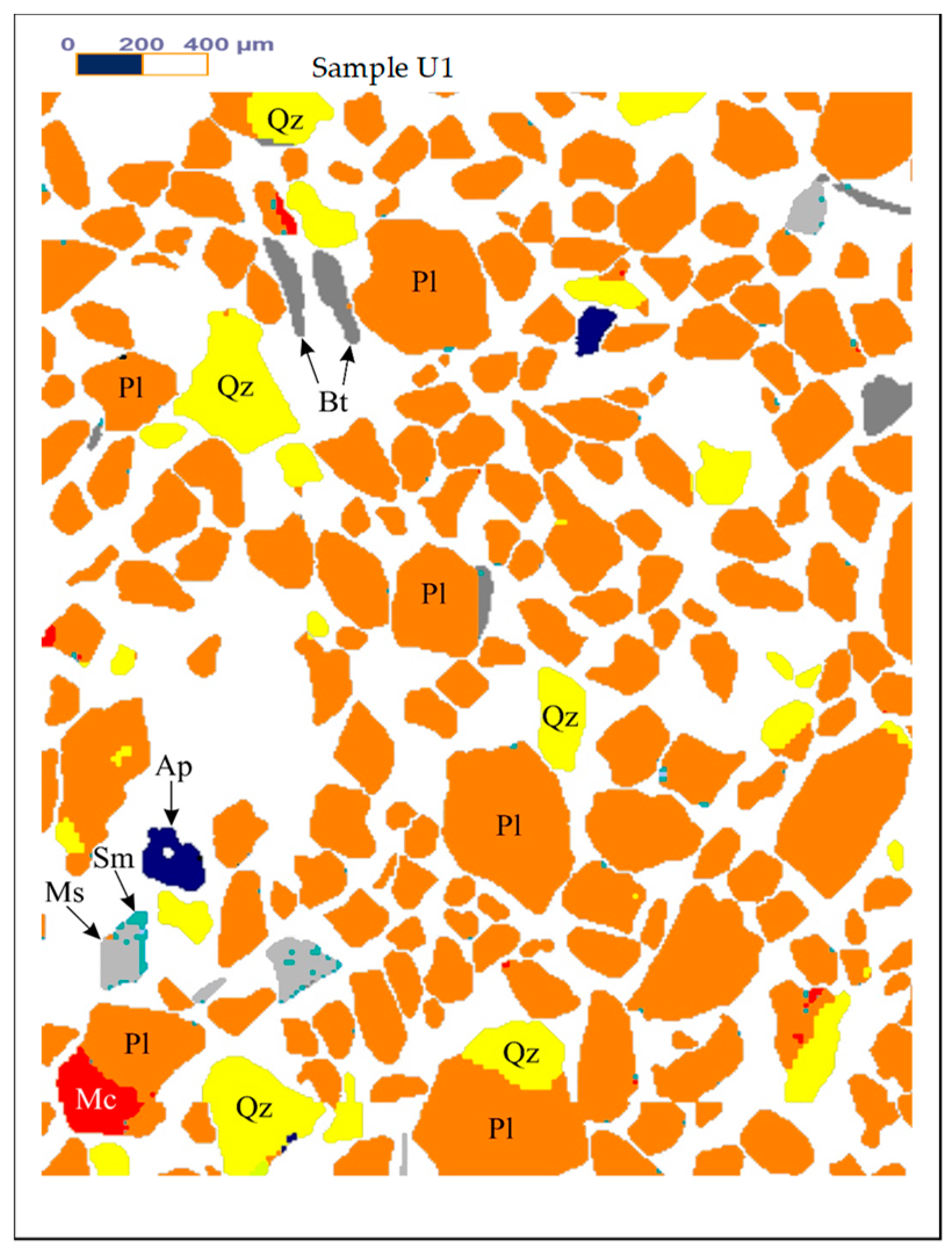

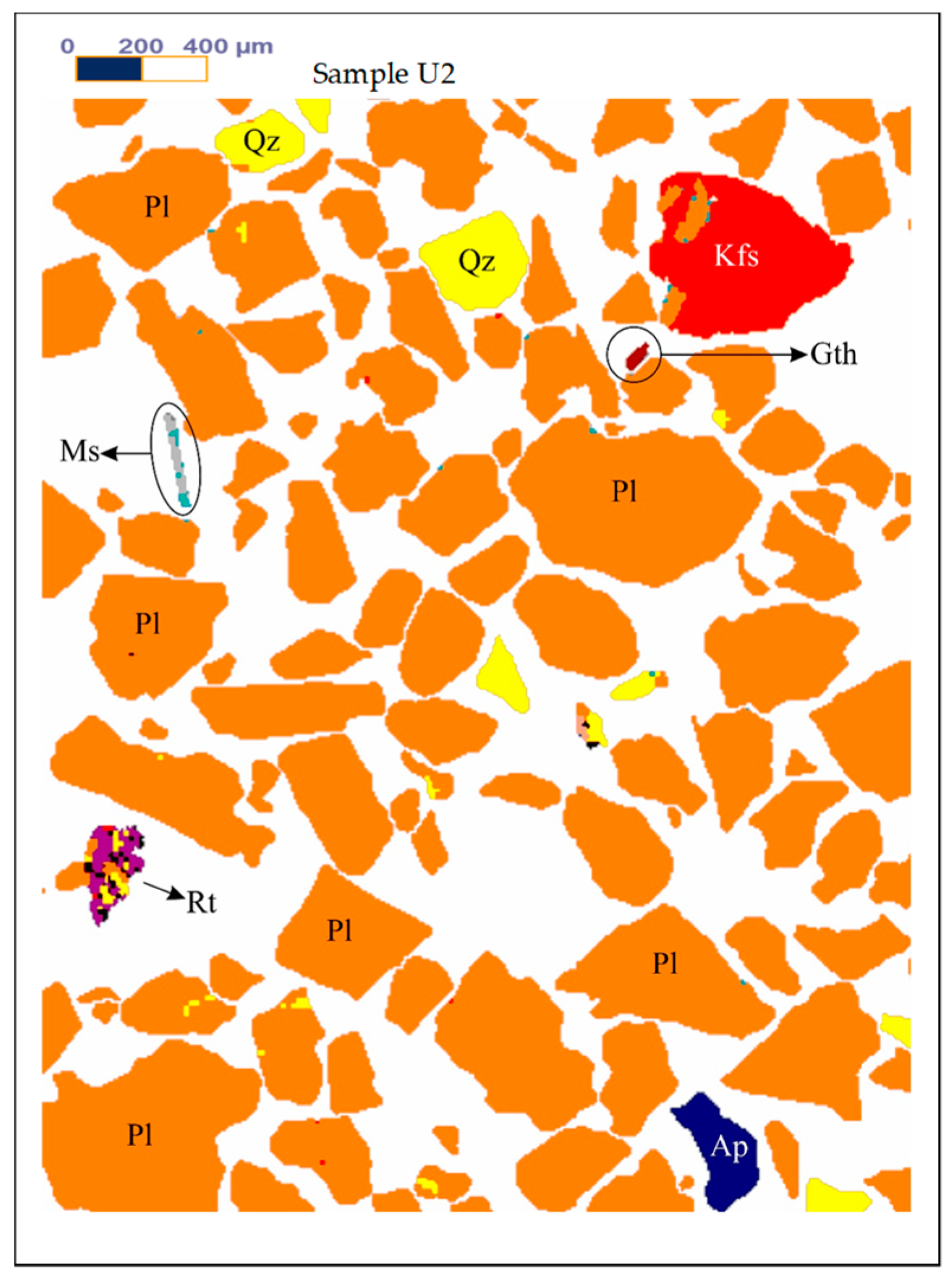

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the results of X-ray diffraction (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan), SEM photo (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) and MLA (Mineral Liberation Anlayses) (JKTech, Brisbane, Australia) mapping analysis of the both samples for mineralogical characterization and comparison. For the related SME and MLA measurements, the commercial MLA’s DataView software version 3.1.3. (JKTech, Brisbane, Australia) was used.

The amount of slimes is dependent upon mineralogical charateristics of the ore and also upon very fine particles after grinding.

Table 3 shows the particle size distribution of the flotation feed and the slime fraction together with the chemical analyses of the two particle size fractions for both samples.

When mineralogical content of the slimes was investigated, it was determined that the amount of the impurities was too high for both of the samples. It was also found that the mica and other oxide minerals forming the impurity in the ore fed into the flotation showed a fine size distribution. At this fine size fraction, it was observed that the slimes mainly contain micaceous particles as well as iron oxide and titanium minerals cover surfaces of feldspar and quartz minerals. It was consequently thought that ultrasound may positively affect the feldspar flotation mechanism at all stages while helping effective removal of initial slimes.

Table 4 shows the MLA mineral content of the samples U1.

Figure 4 shows the MLA mapping results of the samples U2.

Table 5 shows the MLA mineral content of the samples U2.

3. Experimental Results

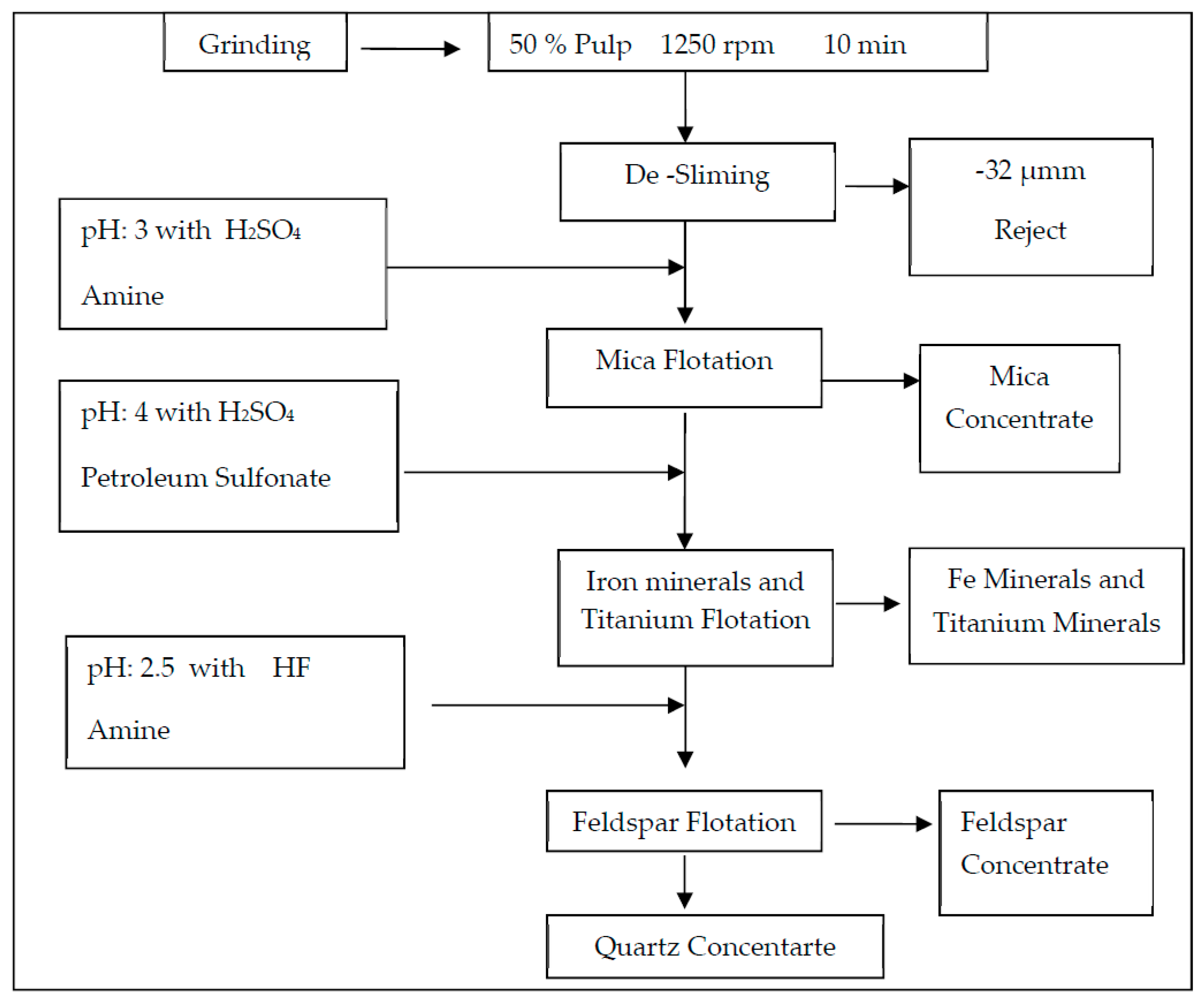

In this study, the effect of ultrasound on multi-stage feldspar flotation was investigated for two representative ore samples of different quality from Milas-Mugla region in Turkey by especially comparing desliming efficiencies with conventional methods. The flotation experiments with and without ultrasonic desliming on the samples comprising different structural and mineralogical properties were carried out with similar operating parameters. In four-stage flotation tests, an amine collector was used to float micaceous minerals in acidic medium while a sulphonate collector was preferred for floating heavy mineral contents in acidic medium. In the final stage, feldpar-quartz separation was performed with HF acid use and the results for feldpar concentrate were compared by using Na2O, Fe2O3 and TiO2 grades also considering desliming stage. While a conventional flotation test was performed by using Denver type flotation machine, ultrasonically assisted experiments were done with a Wemco type flotation machine equipped with special cells connected with ultrasound transducers with various frequecy and power capacities.

Two different test setups were used for multi-stage feldspar flotation with and without ultasonic waves. While the first test group was done by using ultrasonically assisted flotation cells at three-stage flotation together with desliming, the second group was performed by using the conventional flotation cells under the same variables. All the tests were carried out with using 1-L cell, 1200-rpm impeller speed, 20% pulp ratio, 10 min conditioning time and natural pH value. Feldspar flotation was continued after desliming of the minus 32-µm size material by using decantation method. Slime size material was analyzed by weight and impurities content in order to reveal the success of the slime removal ratio.

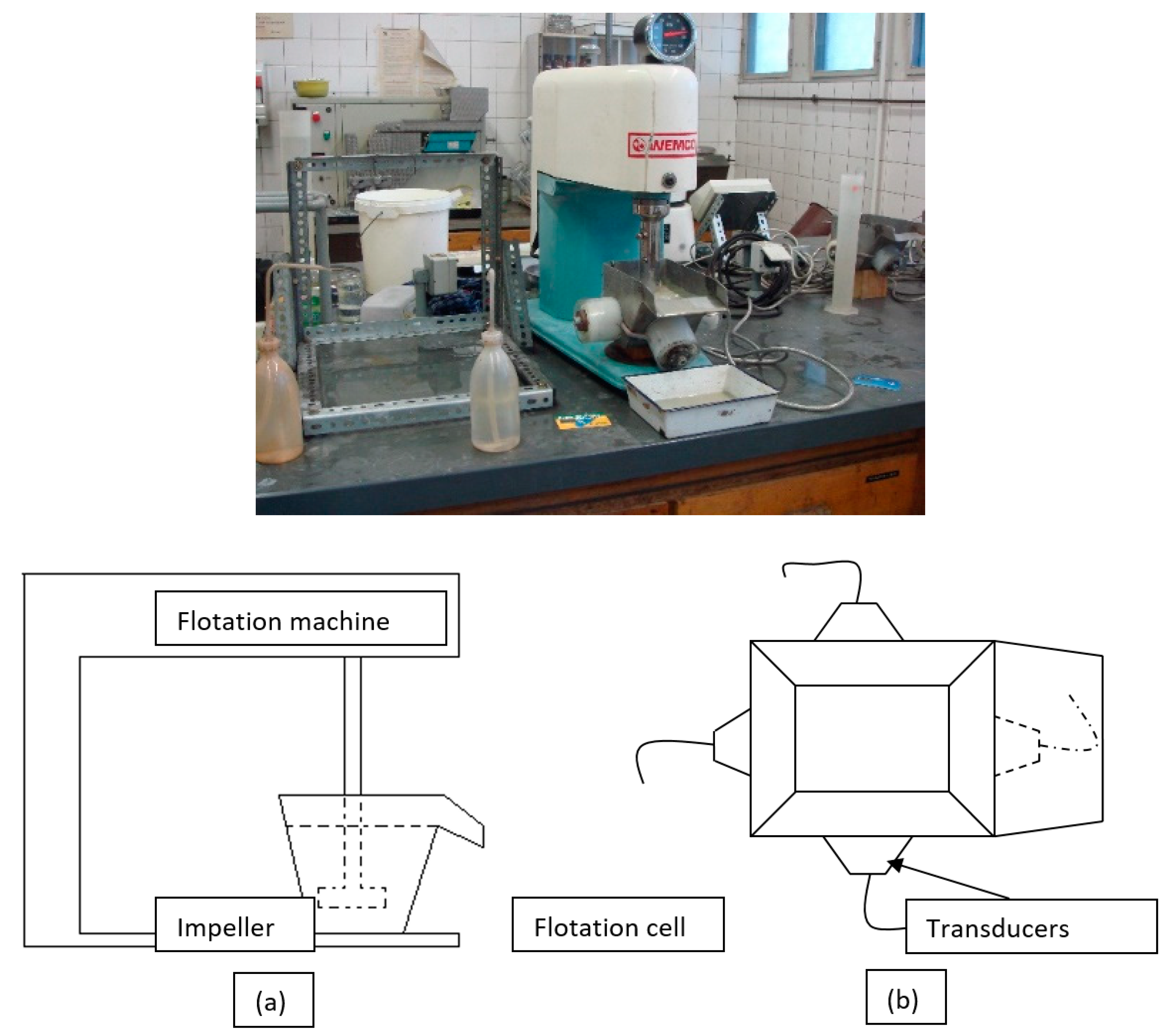

Figure 5 shows the photo of the flotation experimental setup, schematic view of the flotation machine and upper view of newly developed flotation cell with ultrasonic transducers.

The first group of experiments were performed under ultrasound with using newly designed stainless-steel flotation cells at 1-L capacity and connected with the transducers at variable ultrasonic frequecy and power levels. The ultrasonic power generator, converters and other related equipment were supplied by the Bandelin Electronic Company in Berlin. Frequency levels for the flotation cells were arranged at 25, 40 and 25–40 kHz with 50 W stable power capacities for each transducer with different physical dimensions. During the experiments, ultrasonic power generator with a 600 W nominal capacity was run at its half capacity and consumed about 160 W power for four different transducers connected to each flotation cell by electrical losses taken into account.

In the experiments, conditioning was carried out for 10 min. After the conditioning process, the desliming was performed by the decantation method. The analysis of the slime size material for the both groups was undertaken and the results were given in

Table 6 and

Table 7 for comparison. The experimental process flowsheet is given in

Figure 6.

In

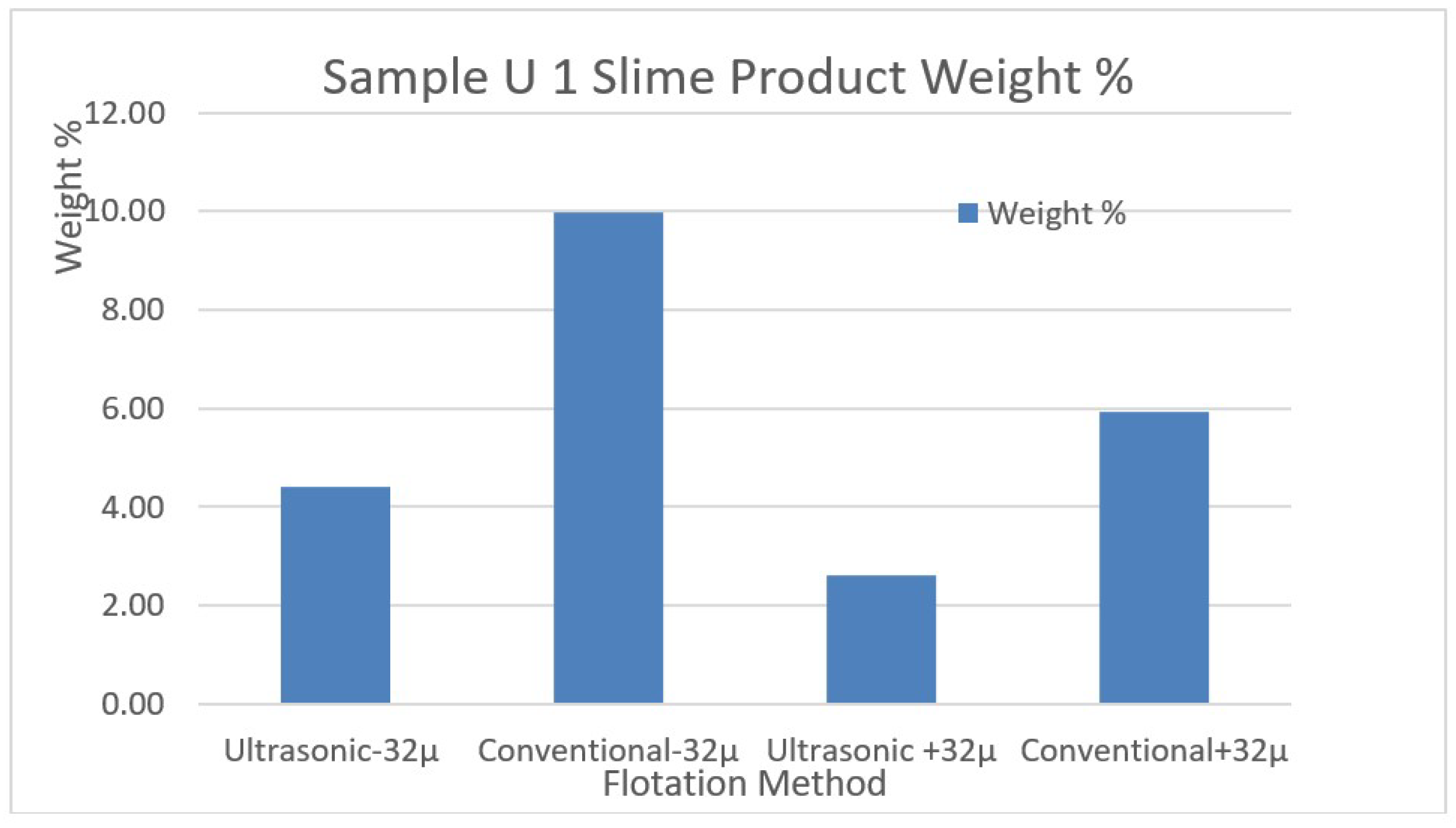

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the comparison of weight changes of the removed slimes by conventional and ultrasonic methods is shown as separate graphs for the samples U1 and U2, respectively.

The quantitative and qualitative flotation test results of deslimed feed samples by conventinal and ultrasonic methods for the sample U1 and U2 are also given in

Table 8 and

Table 9, respectively.

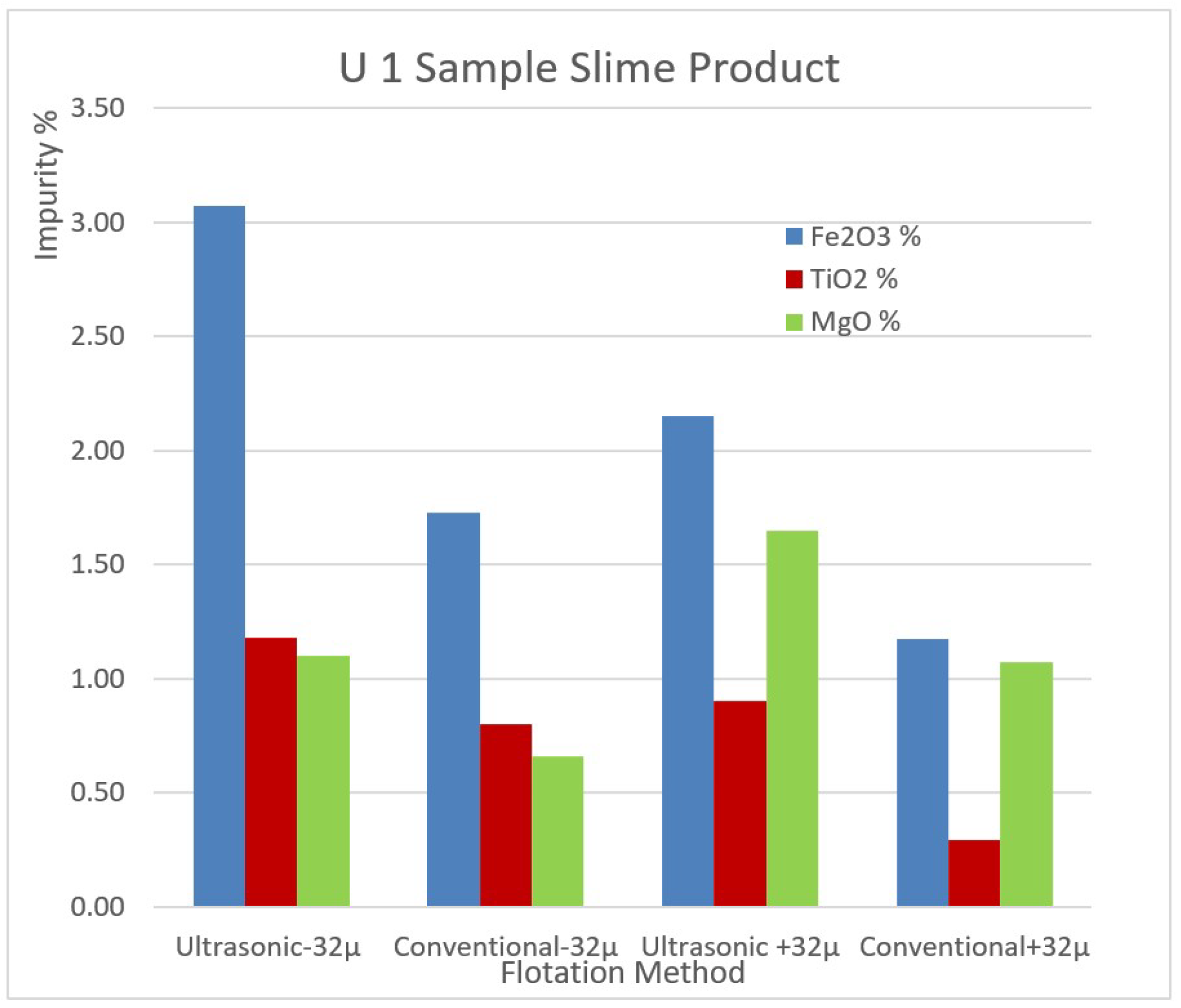

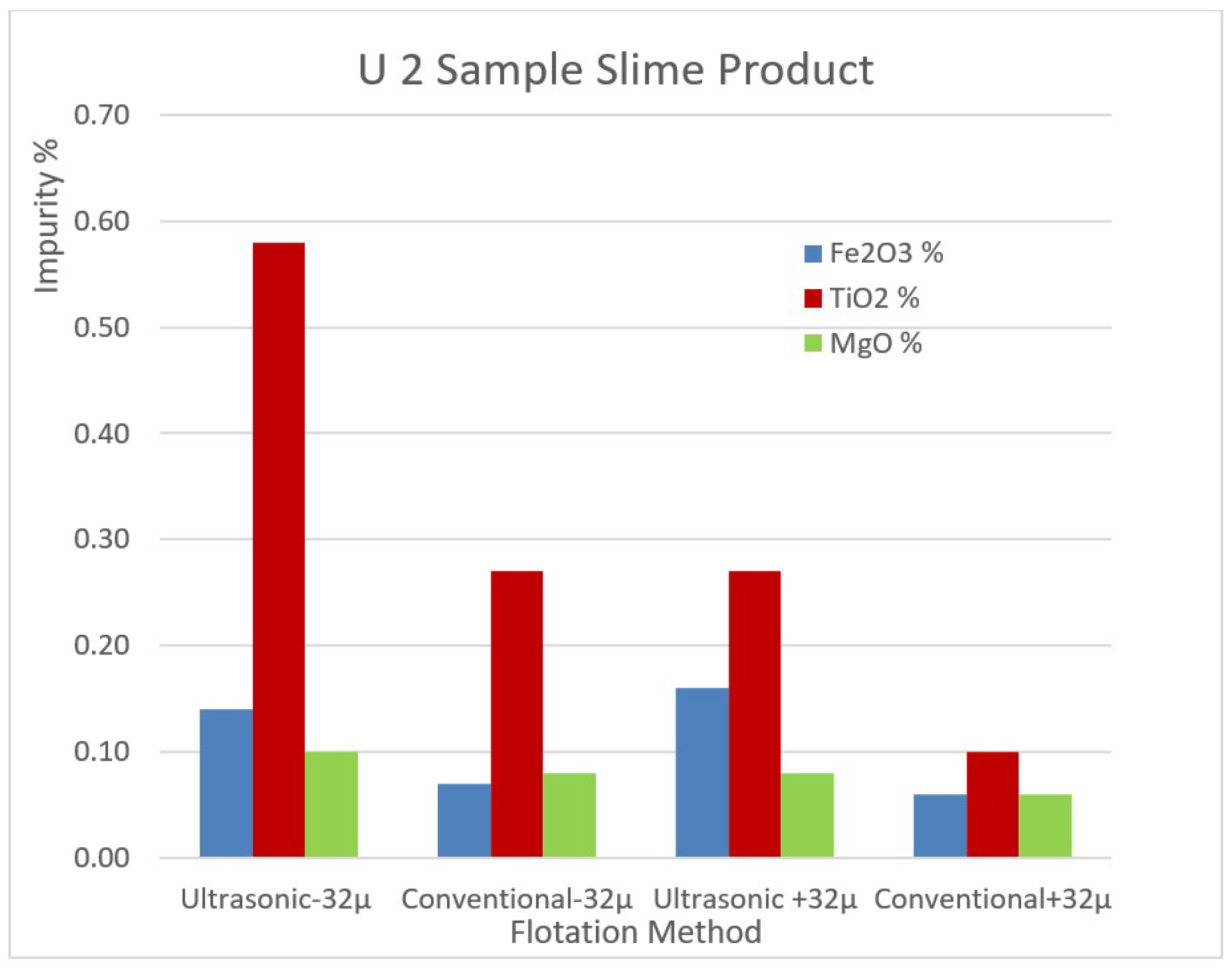

The impurity contents of the removed slimes of the samples U1 and U2 by ultrasonic and conventional methods are shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 for comparison.

Table 10 shows flotation test results with ultrasonic desliming and ultrasonic test conditions of the sample U2.

Table 11 shows flotation test results with conventional desliming and conventional test conditions of the sample U2.

When the flotation products after ultrasonic pre-treatment were investigated, it was seen that the feldspar concentrate from the sample U1 contained 9.01% Na2O, 0.19% Fe2O3, 0.15% TiO2 and 0.47% MgO while the concentrate by conventional flotation yielded 8.40% Na2O, 0.23% Fe2O3, 0.18% TiO2 and 0.36% MgO. These data showed that the feldspar concentrate was quite clean with the help of ultrasonic pre-treatment. Furthermore, it was concluded that ultrasound helped effective impurity removal, and hence resulted in cleaner feldspar concentrates. The mechanism produced more fines and prevented slime coverings on feldspar surfaces. For the sample U2, similar clean feldspar concentrates were also produced after ultrasonic pre-treatment and desliming.

4. Discussions and Conclusions

In this study, the effect of ultrasonic waves during the desliming stage and on the flotation process in later stages were examined in order to reveal the success in removing impurities from feldspar and quartz concentrates. All experimental results were evaluated in the light of the first stage of feldspar flotation, the results of the success of the slime removal process and the further stages of the overall process.

The negative effects of the presence of slimes in the flotation medium in the process are important not only in terms of concentrate grade but also in terms of reactive consumption and selectivity. Slime content of feldspar ore originating from ore formation is a major cause of impurities due to its mica and heavy mineral content. Therefore, slime removal or desliming in feldspar flotation is a necessary process step. In many researches and plant applications, in order to improve concentrated product quality in feldspar flotation, the necessity of sliming has been also proved.

Considering the fact that ore losses in feldspar ore content are removed at a significant amount, the optimization of these negative conditions caused by desliming in feldspar flotation should be evaluated in terms of both particle removal by impurity content and prevention of ore loss and providing positive gains in terms of process economy.

In the flotation experiments carried out with the help of ultrasound for the U1 ore desliming process at minus 32-µm particle, 4.42% slime removal by weight was achieved. However, conventional desliming for the same sample caused 9.99% slime removal by weight. These data showed that ore loses could be prevented with the help of ultrasound. Similar successful results were also achieved for the sample U2 which has different ore structure. In U2 ore desliming process at minus 32-µm particle, 8.59% slime removal by weight was achieved, while conventional desliming for the same sample caused 9.44% slime removal by weight.

The results show that formation of slimes is reduced in the ultrasonic environment. The slime particles in the medium are agglomerated under the influence of ultrasonic forces and act as coarse grains in flotation to eliminate the negativities of slimes. This not only eliminates the effects of slimes but also has a positive effect on the overall yield and grade of flotation.

When the alkali and quartz content of slime and the mica and heavy mineral contents that constitute the impurity are examined, the numerical proof of slime removal in the ultrasonic environment defines the selectivity as the success of the process. In particular, the impurity of the concentrate obtained in the ultrasonic environment is an important indicator.

It is also seen that the microcavitation characterized by ultrasonic treatment changes the distribution principles and mechanisms of fine particles in the pulp by subjecting the particle - particle bonds to degradation. Thus, the distribution of slime size particles in the ultrasonic environment is reduced, as is suggested by previous researchers [

65,

66,

67,

68].

Furthermore, the agglomerates in the pulp provide more homogeneous solution formation under the ultrasonic wave effect. Thus, coarse grains and fine grains are more easily separated, especially by decantation. The decrease in weight loss in mass of slime can be explained by these mechanisms of this ultrasound.

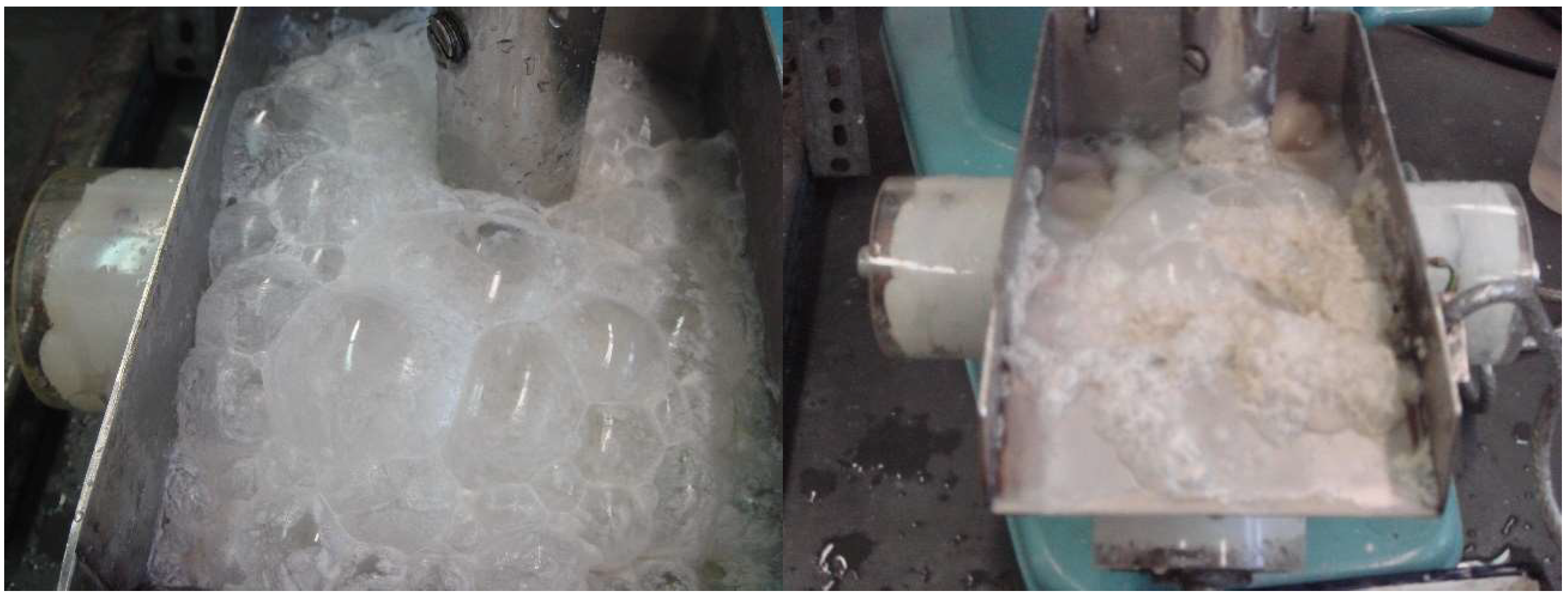

Figure 11 shows the photos of the froth structures with and without ultrasound during feldspar flotation.

Due to the impacts caused by ultrasound waves on the particle surfaces, the fine material adhered to the particle surfaces can be dispersed and removed so that feldspar flotation increases the concentration grade obtained in other stages. At the end of the experiment performed in the ultrasonic environment, the particle size analysis of the slimes and the dispersions of the minerals support the discarded finely sized material properties in this direction. Furthermore, when the mineralogical structure of slime is examined, it can be observed that the presence of mica is removed more effectively in this method. This shows that ultrasonic forces play an important role in the behaviour of layered minerals such as fine mica in the pulp.

In the other steps of feldspar flotation, when the comparison of ultrasonic and conventional flotation is carried out, it can be said that the ultrasonic pre-treatment has a significant effect on the quality of the flotation products and overall recovery. A significant grade and yield advantage over conventional flotation was found to be a measure of success in removing slimes from the environment.

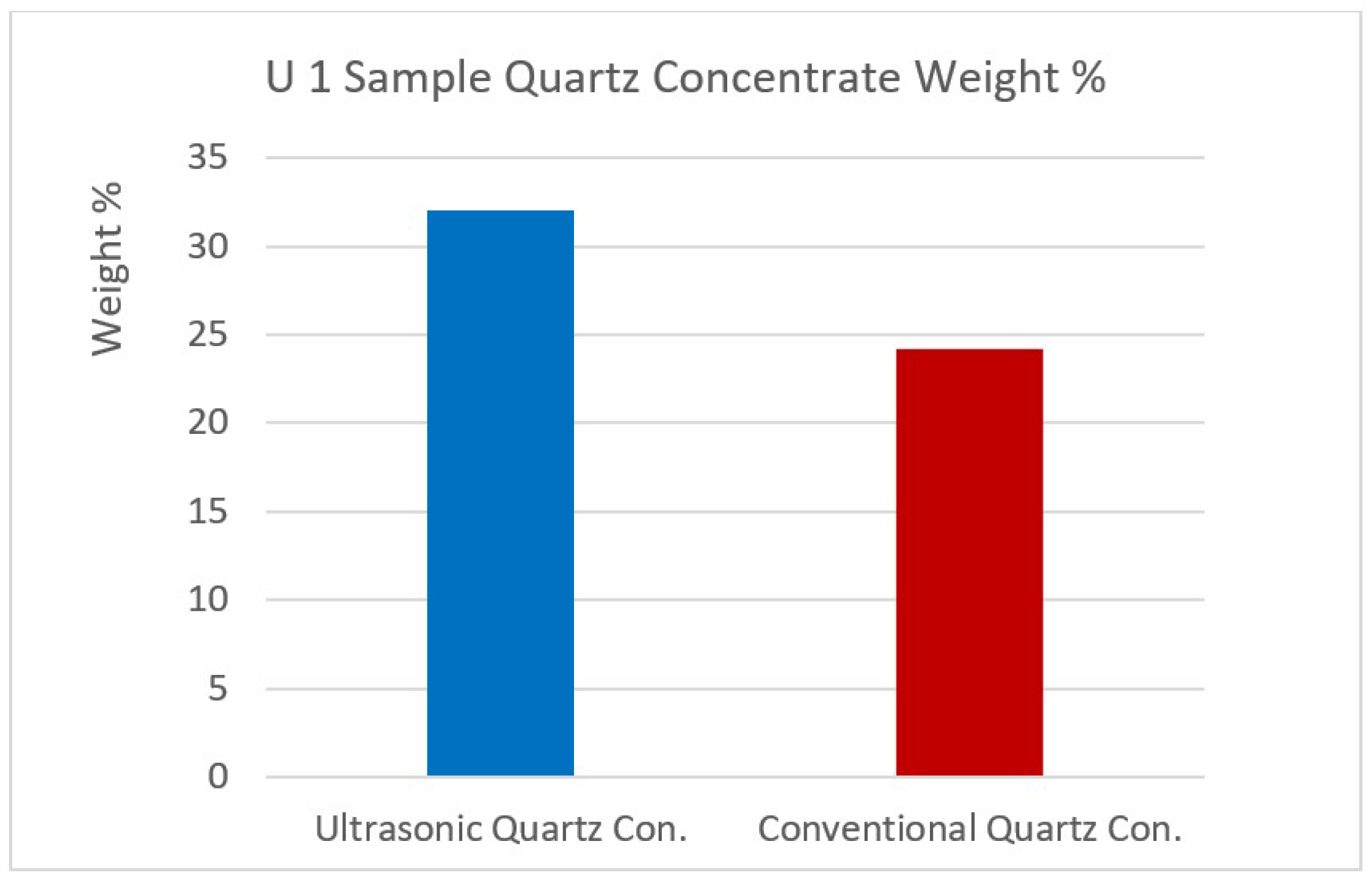

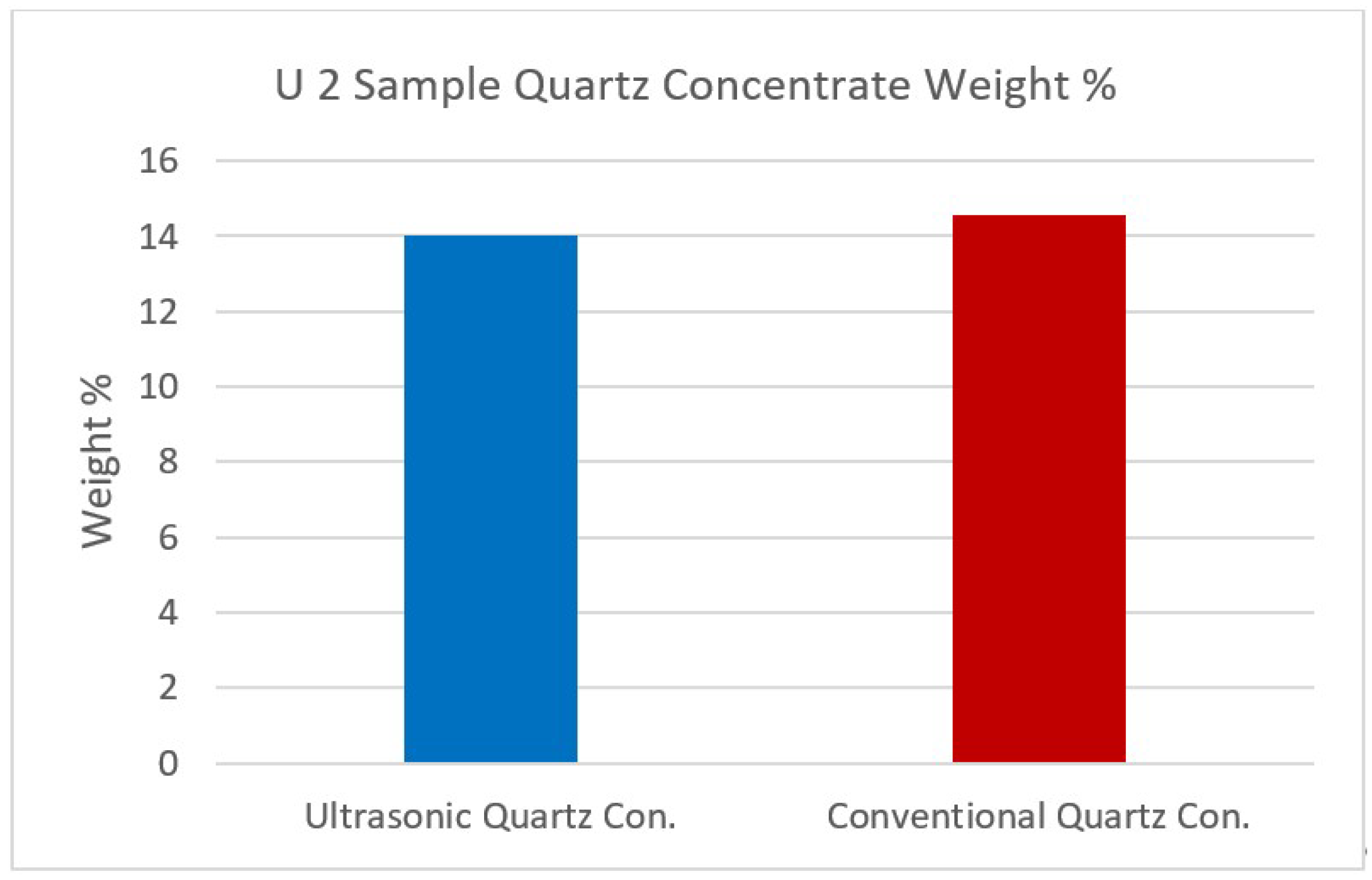

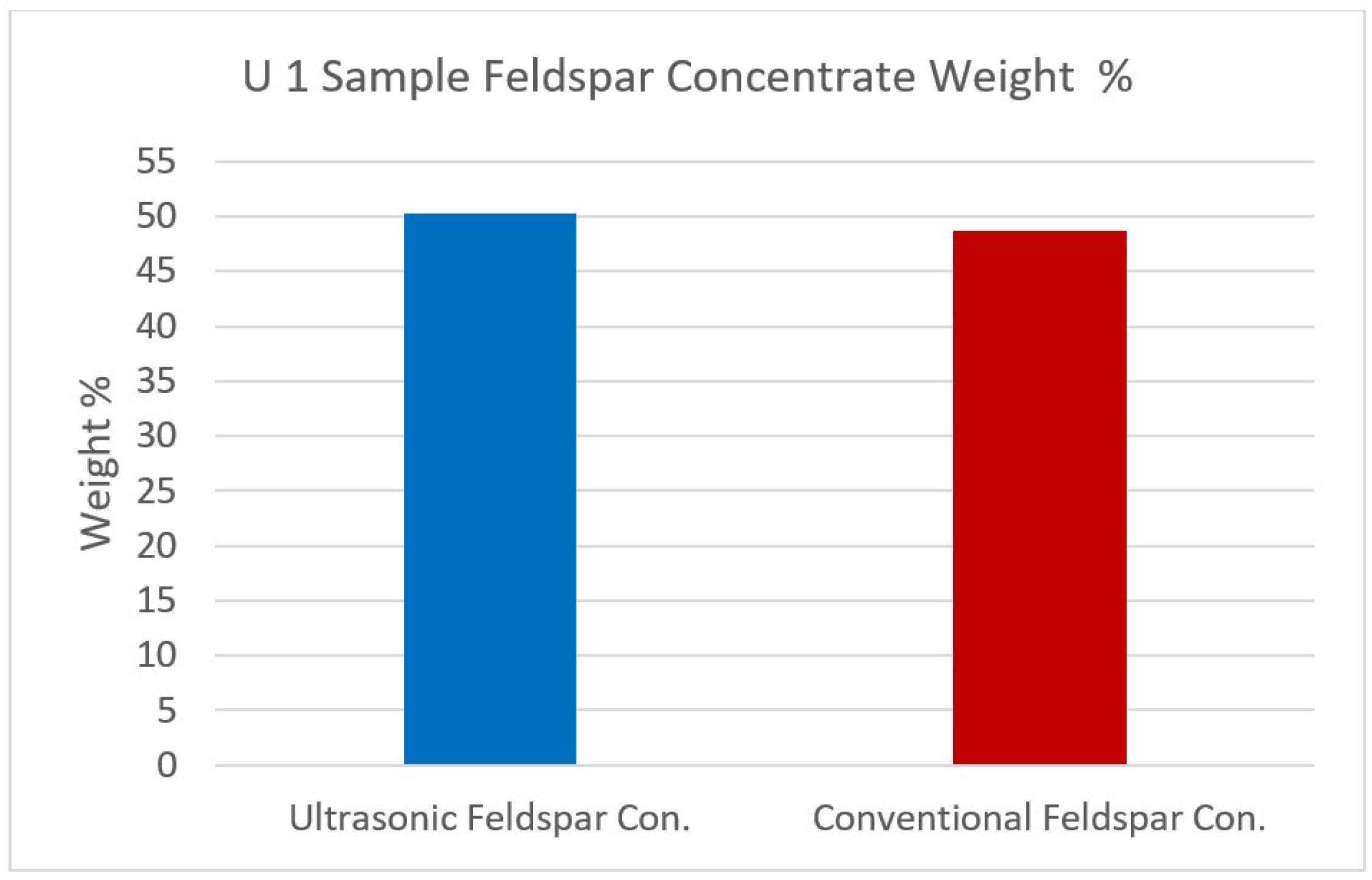

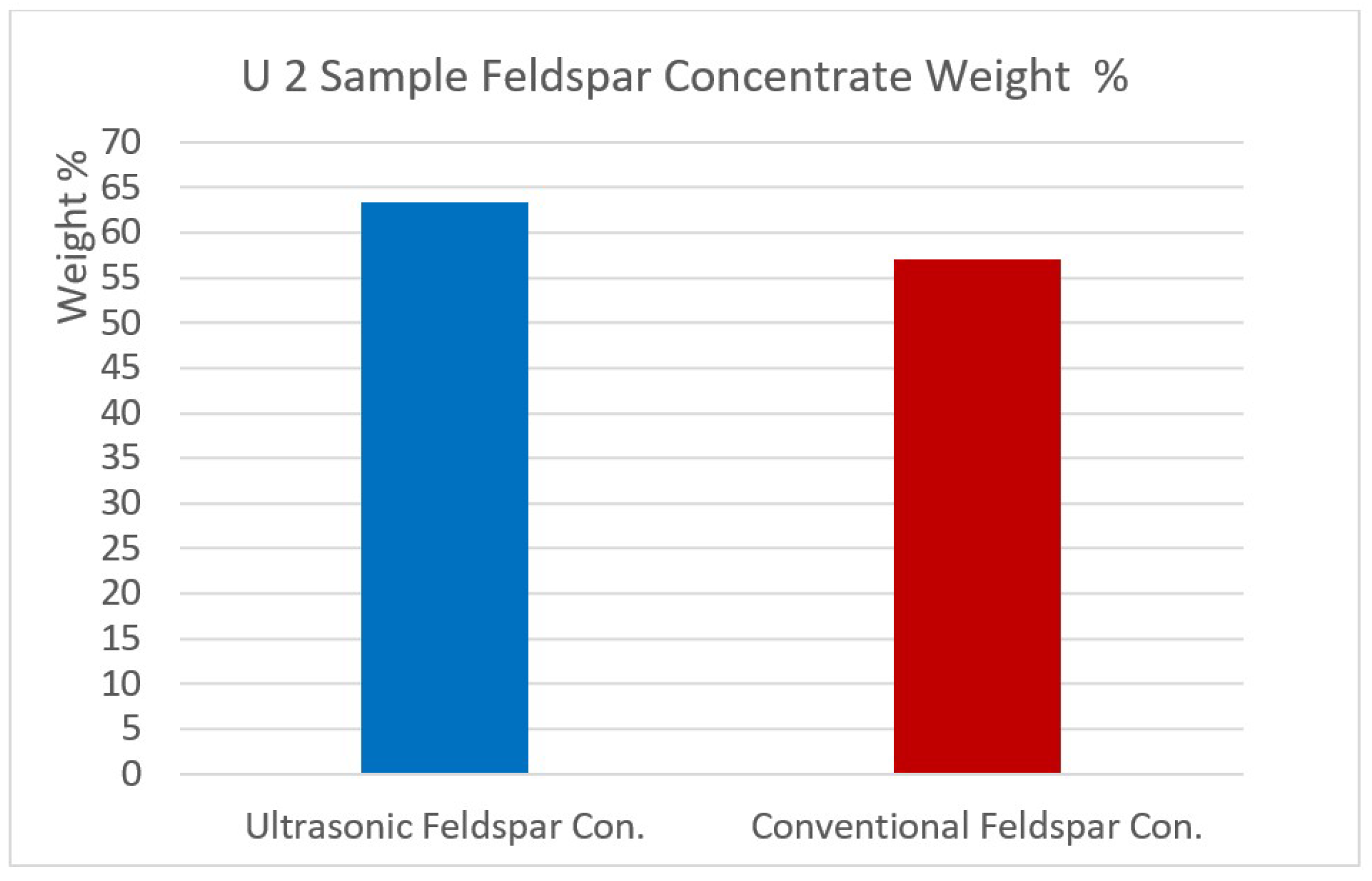

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 show the comparison of the % weights of feldspar and quartz on initial samples (U1 and U2) after conventional and ultrasonic assisted flotation.

As a result of the experiments, a significant success with ultrasound use was obtained in terms of the amount of removed slimes containing impurities when compared with the conventional method. The use of ultrasound increased the quality of feldspar concentrates due to the removal of a high amount of slimes from the pulp containing various impurities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.O.; methodology, S.G.O.; software, U.M.; validation, U.M.; formal analysis, U.M.; investigation, U.M.; resources, U.M.; data curation, U.M.; writing—original draft preparation, U.M.; writing—review and editing, S.G.O.; visualization, S.G.O.; supervision, S.G.O.; project administration, S.G.O.; funding acquisition, U.M.

Funding

This research was funded by Bilimsel Araştirma Projeleri Birimi, Istanbul Üniversitesi, grant number FBA-2017-25533; BEK-2017-24474; BEK-2016-21347.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung and Berlin Technical University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Sun, N.; Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Sun, W. Systematic review of feldspar beneficiation and its comprehensive application. Miner. Eng. 2018, 128, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaied, M.E.; Gallala, W. Beneficiation of feldspar ore for application in the ceramic industry: Influence of composition on the physical characteristics. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 8, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlunenko, L.E. Feldspar materials in Ukraine. Glass Ceram. 2010, 67, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonthornwiphat, N.; Saisinchai, S.; Parinayok, P. Recovery slime waste from feldspar flotation plant at attanee international Co. Ltd. Tak Province. Thail. Eng. J. Thail. 2016, 20, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyes, G.W.; Allan, G.C.; Bruckard, W.J.; Sparrow, G.J. Review of flotation of feldspar. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. C 2012, 121, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaguzel, C. Selective separation of fine albite from feldspatic slime containing colored minerals (Fe-Min) by batch scale dissolved air flotation (DAF). Miner. Eng. 2010, 23, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, I.; Ersayın, S.; Gulsoy, O.Y. Magnetic separation and flotation of albite ore. In Proceedings of the 7th International Mineral Processing Symposium, İstanbul, Turkey, 15–17 September 1998; Atak, S., Onal, G., Celik, M.S., Eds.; A.A. Balkema Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hacifazlioglu, H.; Kursun, I.; Terzi, M. Beneficiation of low-grade feldspar ore using cyclojet flotation cell, conventıonal cell and magnetıc separator. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2012, 48, 381–392. [Google Scholar]

- Amarante, M.A.; Sousa, A.B.; Leite, M.M. Beneficiation of a feldspar ore for application in the ceramic industry. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 1997, 97, 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Akar, A. Evaluation of Gordes–Koprubasi district feldspar industrial raw materials deposits. In Proceedings of the 5th International Mineral Processing Symposium, Cappadocia, Turkey, 6–8 September 1994; Demirel, H., Ersayın, S., Eds.; A.A. Balkema Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Saisinchai, S.; Boonpramote, T.; Meechumna, P. Upgrading feldspar by WHIMS and flotation techniques. Eng. J. Thail. 2015, 19, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Ibrahim, G.A.; Rizk, A.M.E.; Mahmoud, N.A. Reduce the Iron Content in Egyptian Feldspar Ore of Wadi Zirib for Industrial Applications. Int. J. Min. Eng. Miner. Process. 2016, 5, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, O.; Arslan, V.; Cebeci, Y. Combined application of different collectors in the flotation concentration of Turkish Feldspars. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, M.S.; Pehlivanoglu, B.; Aslanbas, A.; Asmatulu, R. Flotation of colored impurities from feldspar ores. Miner. Metall. Process. 2001, 18, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, E.C.; Bayraktar, I. Amine–oleate interactions in feldspar flotation. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsoy, O.Y.; Can, N.M.; Bayraktar, I.; Ersayın, S.; Hızal, M.; Sahin, A.I. Two stage flotation of sodium feldspar—From laboratory to industrial application. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. C 2004, 113, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyadhar, A.; Rao Hanumantha, K. Adsorption mechanism of mixed cationic/anionic collectors in feldspar-quartz flotation system. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 306, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Salmavy, M.S.; Nakahiro, Y.; Wakamatsu, T. New Reagent Systems in Flotation Separation of Quartz from Feldspar. In Proceedings of the XIX International Mineral Processing Congress, San Francisco; Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration: Littleton, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 285–289. [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktar, I.; Ersayın, S.; Gulsoy, O.Y. Upgrading titanium bearing Na-feldspar by flotation using sulphonates, succinamates and soaps of vegetable oils. Miner. Eng. 1997, 1, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, M.S.; Can, I.; Eren, R.H. Removal of titanium impurities from feldspar ores by new flotation collectors. Miner. Eng. 1998, 11, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Malayoglu, U.; Aksay, K.E.; Kurcan, I. Noval approach for the removal of impurities from feldspar ores. Asian J. Chem. 2012, 24, 5283–5285. [Google Scholar]

- Vidyadhar, A.; Rao, K.H.; Forssberg, K.S.E. Adsorption of n-tallow 1,3-propanediamine-dioleate collector on albite and quartz minerals and selective flotation of albite from Greek Stefania Ore. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 248, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ma, L.; Cao, M.; Liu, Q. Slime coatings in froth flotation: A review. Miner. Eng. 2017, 114, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulgonul, I.; Karaguzel, C.; Celik, M.S. Surface vs. Bulk analyses of various feldspars and their significance to flotation. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2008, 86, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, J.; Choung, J.W.; Zhou, Z. Electrokinetic study of clay interactions with coal in flotation. Int. J. Min. Process. 2003, 68, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peng, Y. Managing clay minerals in froth flotation—A critical review. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2018, 39, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaguzel, C.; Cobanoglu, G. Stage-wise flotation for the removal of colored minerals from feldspatic slimes using laboratory scale Jameson cell. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 74, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, A.E.C.; Vieira, A.M. The effect of amine type, pH, and size range in the flotation of quartz. Miner. Eng. 2007, 20, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, N.; Peng, Y. Rheology measurements for flotation slurries with high clay contents—A critical review. Miner. Eng. 2016, 98, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burat, F.; Kokkilic, O.; Kangal, O.; Gurkan, V.; Celik, M.S. Quartz-feldspar separation for the glass and ceramics industries. Miner. Metall. Proc. 2007, 24, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangal, O.; Guney, A. Beneficiation of low-grade feldspars using free jet flotation. Min. Proc. Ext. Met. Rev. 2002, 23, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, P.; Prestidge, C.A.; Ralston, J. Colloidal Iron Oxide Slime Coatings and Galena Particle Flotation. Miner. Eng. 2001, 14, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, V.; Ucbas, Y.; Koca, S.; Ipek, H. Recovery of feldspar from trachyte by flotation. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 1216–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, C. Selective separation of Na-and K-feldspar from weathered granites by flotation in HF medium. Ceram Silik. 2010, 54, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, C.; Bentil, I.; Gulgonul, I.; Celik, M.S. Effects of bivalent salts on the flotation separation of Na-feldspar from K-feldspar. Miner. Eng. 2003, 16, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, C.; Gulgonul, I.; Bentli, I.; Celik, M.S. Differential separation of albite from microcline by monovalent salts in HF medium. Miner. Metall. Proc. 2003, 20, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, C.; Abromov, A.A.; Celik, M.S. Flotation separationof Na-feldspar from K-feldspar by monovalent salts. Miner. Eng. 2001, 14, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsoy, O.Y.; Can, N.M.; Bayraktar, I. Production of potassium feldspar concentrate from a low-grade pegmatitic ore in Turkey. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. 2005, 114, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksay, E.K. Multi-stage flotation of colored impurities from albite ore in the presence of some cationic and anionic collectors. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2016, 54, 220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, S.G. Further investigations on simultaneous ultrasonic coal flotation. Minerals 2017, 7, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.G. Beneficiation of magnesite slimes with ultrasonic treatment. Miner. Eng. 2002, 15, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.G. Effects of simultaneous ultrasonic treatment on flotation of hard coal slimes. Fuel 2012, 93, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Aldrich, C. Effect of Ultrasonication on the Flotation of Talc. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 4422–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, C.; Feng, D. Effect of ultrasonic preconditioning of pulp on the flotation of sulphide ores. Miner. Eng. 1999, 12, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilek, E.C.; Ozgen, S. Effect of ultrasound on separation selectivity and efficiency of flotation. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilek, E.C.; Ozgen, S. Improvement of the flotation selectivity in a mechanical flotation cell by ultrasound. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurpinar, G.; Sonmez, E.; Bozkurt, V. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on flotation of calcite, barite and quartz. Miner. Process. Extract. Metall. 2013, 113, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktepe, F.; Ipek, H.; Gokepe, M. Beneficiation of quartz waste by flotation and by ultrasonic treatment. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2011, 47, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, S.G.; Veasey, T.J. Effect of Simultaneous Ultrasonic Treatment on Colemanite Flotation. In Proceedings of the 6 th Mineral Processing Symposium, Kusadasi, Turkey, 24–26 September 1996; pp. 277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, M.S.; Elma, I.; Hancer, M.; Mıller, J.D. Effect of in-situ ultrasonics on the floatability of slime coated colemanite. In Proceedings of the 7th International Mineral Processing Symposium, İstanbul, Turkey, 15–17 September 1998; Atak, S., Onal, G., Celik, M.S., Eds.; A.A. Balkema Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer, M.; Kangal, M.O.; Benkli, Y.E.; Arslan, F.; Onal, G. Effect of Ultrasonic treatment on the sedimentation of clays. In Proceedings of the 9th Balkan Mineral Processing Symposium, Istanbul, Turkiye, 11–13 September 2001; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Onal, G.; Ozer, M.; Arslan, F. Sedimentation of clay in ultrasonic medium. Miner. Eng. 2003, 16, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.G.; Kuyumcu, H.Z. Zum einfluss von ultraschall auf die steinkohleflotation (The influence of ultrasonics on coal flotation). Aufbereit. Tech. 2006, 47, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, S.G.; Kuyumcu, H.Z. Investigation of mechanism of ultrasound on coal flotation. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2006, 81, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.G.; Kuyumcu, H.Z. Design of a flotation cell equipped with ultrasound transducers to enhance coal flotation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007, 14, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didenko, P.I.; Efremov, A.A. SIMS study of self-consisted fractionation of iron and titanium isotopes in ilmenites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 231, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, A.D.; Collings, A.F.; Jameson, G.J. Effect of ultrasound on surface cleaning of silica particles. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 60, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerkovic, C.; Menacho, J.; Gaete, L. Exploring the ultrasonic comminution of copper ores. Miner. Eng. 1993, 6, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, N.E.; Hwang, J.Y.; Hicyilmaz, C. Enhancement of flotation performance of oil shale cleaning by ultrasonic treatment. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2009, 91, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambedkar, B.; Nagarajan, R.; Jayanti, S. Investigation of high frequency, high intensity ultrasonics for size reduction and washing of coal in aqueous medium. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 13210–13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoev, S.M.; Martin, P.D. The Application of Vibration and Sound in Minerals and Metals Industries; A Technical Review, MIRO Series No: 8; Bonney, C.F., Ed.; MIRO: Lichfield, UK, 1992; p. 658. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, M.S. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the floatability of coal and galena. Sep. Sci. Technol. 1989, 24, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djendova, S.; Mehandjski, V. Study of the effects of acoustic vibration conditioning of collector and frother on flotation of sulphide ores. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1992, 34, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaczka, A. Effect of an ultrasonic field on the flotation selectivity of barite from a barite-fluorite-quartz ore. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1987, 20, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungoren, C.; Ozdemir, O.; Ozkan, S.G. Effects of temperature during ultrasonic conditioning in quartz-amine flotation. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2017, 53, 687–698. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, S.G.; Gungoren, C. Enhancement of colemanite flotation by ultrasonic pre-treatment. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2012, 48, 455–462. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, S.G. A review of simultaneous ultrasound-assisted coal flotation. J. Min. Environ. 2018, 9, 679–689. [Google Scholar]

- Gungoren, C.; Ozdemir, O.; Wang, X.; Ozkan, S.G.; Miller, J.D. Effect of ultrasound on bubble-particle interaction in quartz-amine flotation system. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 52, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The XRD analysis results of the samples U1 (a) and U2 (b).

Figure 1.

The XRD analysis results of the samples U1 (a) and U2 (b).

Figure 2.

The SEM photos of the samples (a) Sample U1 and (b) Sample U2.

Figure 2.

The SEM photos of the samples (a) Sample U1 and (b) Sample U2.

Figure 3.

The Mineral Liberation Anlayses (MLA) mapping results of the samples U1. Abbreviations: Ap-Apatite, Bt-Biotite, Gth-Goethite, Kfs-K feldspar, Mc-Microcline, Ms-Muscovite, Pl-Albite-Oligoclase, Qz-Quartz, Rt-Rutile, Sm-Smectite.

Figure 3.

The Mineral Liberation Anlayses (MLA) mapping results of the samples U1. Abbreviations: Ap-Apatite, Bt-Biotite, Gth-Goethite, Kfs-K feldspar, Mc-Microcline, Ms-Muscovite, Pl-Albite-Oligoclase, Qz-Quartz, Rt-Rutile, Sm-Smectite.

Figure 4.

The MLA mapping results of the samples U2. Abbreviations: Ap-Apatite, Bt-Biotite, Gth-Goethite, Kfs-K feldspar, Mc-Microcline, Ms-Muscovite, Pl-Albite-Oligoclase, Qz-Quartz, Rt-Rutile, Sm-Smectite.

Figure 4.

The MLA mapping results of the samples U2. Abbreviations: Ap-Apatite, Bt-Biotite, Gth-Goethite, Kfs-K feldspar, Mc-Microcline, Ms-Muscovite, Pl-Albite-Oligoclase, Qz-Quartz, Rt-Rutile, Sm-Smectite.

Figure 5.

The photo of the flotation experimental setup, (a) schematic, (b) upper view of ultrasonic cell.

Figure 5.

The photo of the flotation experimental setup, (a) schematic, (b) upper view of ultrasonic cell.

Figure 6.

Experimental process flow sheet.

Figure 6.

Experimental process flow sheet.

Figure 7.

The comparison of weight changes of the removed slimes by conventional and ultrasonic methods for the sample U1.

Figure 7.

The comparison of weight changes of the removed slimes by conventional and ultrasonic methods for the sample U1.

Figure 8.

The comparison of weight changes of the removed slimes by conventional and ultrasonic methods for the sample U2.

Figure 8.

The comparison of weight changes of the removed slimes by conventional and ultrasonic methods for the sample U2.

Figure 9.

The impurity contents of the removed slimes of the sample U1 by ultrasonic and conventional method.

Figure 9.

The impurity contents of the removed slimes of the sample U1 by ultrasonic and conventional method.

Figure 10.

The impurity contents of the removed slimes of the sample U2 by ultrasonic and conventional method.

Figure 10.

The impurity contents of the removed slimes of the sample U2 by ultrasonic and conventional method.

Figure 11.

Photos of the flotation froths (left: conventional, right: ultrasonic).

Figure 11.

Photos of the flotation froths (left: conventional, right: ultrasonic).

Figure 12.

U1 sample quartz concentrate weight %.

Figure 12.

U1 sample quartz concentrate weight %.

Figure 13.

U2 sample quartz concentrate weight %.

Figure 13.

U2 sample quartz concentrate weight %.

Figure 14.

U1 sample Feldspar concentrate weight %.

Figure 14.

U1 sample Feldspar concentrate weight %.

Figure 15.

U2 sample Feldspar concentrate weight %.

Figure 15.

U2 sample Feldspar concentrate weight %.

Table 1.

Chemical analysis results of representative feldspar ore samples.

Table 1.

Chemical analysis results of representative feldspar ore samples.

| Sample | U1 | U2 |

|---|

| component | % | % |

| SiO2 | 74.35 | 71.90 |

| Al2O3 | 15.52 | 17.20 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.54 | 0.08 |

| TiO2 | 0.30 | 0.22 |

| CaO | 0.88 | 0.66 |

| MgO | 0.44 | 0.17 |

| Na2O | 6.44 | 9.43 |

| K2O | 1.23 | 0.15 |

| P2O5 | 0.29 | 0.18 |

Table 2.

Original particle size distribution of the flotation feed material.

Table 2.

Original particle size distribution of the flotation feed material.

| Particle Size (µm) | Sample U1 | Sample U2 |

|---|

| Weight, % | Σ Under Size % | Weight, % | Σ Under Size % |

|---|

| 315–250 | 3.69 | 100.00 | 27.87 | 100.00 |

| 250–125 | 35.88 | 96.31 | 33.11 | 72.13 |

| 125–63 | 40.90 | 60.42 | 19.34 | 39.02 |

| 63–32 | 12.14 | 19.53 | 7.54 | 19.67 |

| <32 | 7.39 | 7.39 | 12.13 | 12.13 |

Table 3.

Chemical analysis at two-size fractions the flotation feed and slime fractions.

Table 3.

Chemical analysis at two-size fractions the flotation feed and slime fractions.

| Particle Size (µm) | Weight % | U1 Sample Assay (%) |

| SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

| +32 | 12.14 | 68.45 | 19.,52 | 0.24 | 0.70 | 1.10 | 0.34 | 8.89 | 0.65 | 0.44 |

| −32 | 7.39 | 67.20 | 20.27 | 1.83 | 1.00 | 1.52 | 0.70 | 5.91 | 0.91 | 0.67 |

| Particle Size (µm) | Weight % | U2 Sample Assay (%) |

| SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

| +32 | 7.54 | 71.30 | 17.71 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.55 | 0.05 | 9.97 | 0.17 | 0.06 |

| −32 | 12.13 | 70.29 | 18.70 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 9.72 | 0.16 | 0.08 |

Table 4.

The MLA mineral content of the sample U1.

Table 4.

The MLA mineral content of the sample U1.

| Mineral | wt.% in 0–315 μm Fraction | Binary Particle (%) | Ternary + Particle (%) |

|---|

| Albite-Oligoclase | 83.78 | 5 | 0 |

| Quartz | 11.84 | 24 | 1 |

| Biotite | 1.82 | 28 | 7 |

| Apatite | 0.31 | 8 | 6 |

| Muscovite | 1.34 | 82 | 15 |

| Smectite | 0.15 | 77 | 22 |

| Microcline | 0.34 | 54 | 16 |

| Titanite | 0.22 | 68 | 14 |

| Chlorite | 0.7 | 59 | 41 |

| Kaolinite | 0.3 | 29 | 71 |

| Rutile | 0.01 | 41 | 59 |

| Process Metal | 0.03 | 93 | 7 |

| Magnetite | 0.1 | 54 | 46 |

| Zircon | 0.01 | 25 | 20 |

| Unclassified | 0.05 | 66 | 34 |

Table 5.

The MLA mineral content of the samples U2.

Table 5.

The MLA mineral content of the samples U2.

| Mineral | wt.% in 0–315 μm Fraction | Binary Particle (%) | Ternary + Particle (%) |

|---|

| Albite-Oligoclase | 90.566 | 2.48 | 0.25 |

| Quartz | 6.744 | 19.29 | 1.80 |

| Biotite | 0.008 | 50.55 | 34.34 |

| Apatite | 1.503 | 17.13 | 0.17 |

| Muscovite | 0.204 | 66.00 | 34.00 |

| Smectite | 0.062 | 73.39 | 26.59 |

| K-feldspar | 0.360 | 58.48 | 9.03 |

| Titanite | 0.009 | 75 | 25 |

| Kaolinite | 0.003 | 59.95 | 40.05 |

| Rutile | 0.330 | 38.43 | 57.73 |

| Geothite | 0.097 | 18.74 | 80.69 |

| Magnetite | 0.007 | 15.38 | 84.62 |

| Zircon | 0.019 | 80.86 | 19.14 |

| Unclassified | 0.089 | 42.91 | 13.00 |

Table 6.

The properties of the slimes in ultrasonic environment.

Table 6.

The properties of the slimes in ultrasonic environment.

| Particle Size (µm) | Weight % | Sample U1 Slime Product |

| SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

| +32 | 2.63 | 68.15 | 19.18 | 2.15 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.65 | 4.64 | 1.93 | 0.50 |

| −32 | 4.42 | 66.60 | 19.97 | 3.07 | 1.18 | 1.39 | 1.10 | 4.95 | 1.01 | 0.73 |

| Particle Size (µm) | Weight % | Sample U2 Slime Product |

| SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

| +32 | 3.32 | 69.99 | 19.11 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.51 | 0.08 | 9.58 | 0.18 | 0.12 |

| −32 | 8.59 | 69.22 | 19.31 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.10 | 9.62 | 0.16 | 0.14 |

Table 7.

The properties of the slimes in the conventional conditions.

Table 7.

The properties of the slimes in the conventional conditions.

| Particle Size (µm) | Weight % | Sample U1 Slime Product |

| SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

| +32 | 5.94 | 70.69 | 19.07 | 1.17 | 0.29 | 0.78 | 1.07 | 4.92 | 1.88 | 0.12 |

| −32 | 9.99 | 69.36 | 19.19 | 1.73 | 0.80 | 1.23 | 0.66 | 5.38 | 1.10 | 0.55 |

| Particle Size (µm) | Weight % | Sample U2 Slime Product |

| SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

| +32 | 3.65 | 69.86 | 19.16 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 9.92 | 0.13 | 0.11 |

| −32 | 9.44 | 68.87 | 19.77 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 9.97 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

Table 8.

Flotation test results with ultrasonic desliming and ultrasonic test conditions of the sample U1.

Table 8.

Flotation test results with ultrasonic desliming and ultrasonic test conditions of the sample U1.

| Product | Weight % | SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

|---|

| Slime −32 μm | 4.42 | 66.60 | 19.97 | 3.07 | 1.18 | 1.39 | 1.10 | 4.95 | 1.01 | 0.73 |

| Slime +32 μm | 2.63 | 68.15 | 19.18 | 2.15 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.65 | 4.64 | 1.93 | 0.50 |

| Mica Concentrate | 1.53 | 68.47 | 17.48 | 3.22 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 1.51 | 4.87 | 1.66 | 0.90 |

| Metal Oxide Mineral Concentrate | 9.04 | 69.53 | 17.50 | 2.01 | 1.05 | 1.65 | 0.58 | 5.32 | 1.21 | 1.15 |

| Feldspar Concentrate | 50.32 | 67.66 | 20.09 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.81 | 0.47 | 9.01 | 1.48 | 0.14 |

| Quartz Concentrate | 32.07 | 88.05 | 6.77 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.69 | 0.14 | 3.14 | 0.80 | 0.22 |

Table 9.

Flotation test results with conventional desliming and conventional test conditions of the sample U1.

Table 9.

Flotation test results with conventional desliming and conventional test conditions of the sample U1.

| Product | Weight % | SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

|---|

| Slime −32 μm | 9.99 | 69.36 | 19.19 | 1.73 | 0.80 | 1.23 | 0.66 | 5.38 | 1.10 | 0.55 |

| Slime +32 μm | 5.94 | 70.69 | 19.07 | 1.17 | 0.29 | 0.78 | 1.07 | 4.92 | 1.88 | 0.12 |

| Mica Concentrate | 5.75 | 68.50 | 19.82 | 1.71 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 1.07 | 4.82 | 1.95 | 0.65 |

| Metal Oxide Mineral Concentrate | 5.46 | 70.12 | 19.05 | 1.09 | 0.75 | 1.99 | 0.47 | 4.54 | 0.89 | 1.10 |

| Feldspar Concentrate | 48.68 | 70.68 | 17.89 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 8.40 | 1.40 | 0.15 |

| Quartz Concentrate | 24.19 | 87.02 | 6.59 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.88 | 0.20 | 4.11 | 0.67 | 0.23 |

Table 10.

Flotation test results with ultrasonic desliming and ultrasonic test conditions of the sample U2.

Table 10.

Flotation test results with ultrasonic desliming and ultrasonic test conditions of the sample U2.

| Product | Weight % | SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

|---|

| Slime −32 μm | 8.59 | 69.22 | 19.31 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.10 | 9.62 | 0.16 | 0.14 |

| Slime +32 μm | 3.32 | 69.99 | 19.11 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.51 | 0.08 | 9.58 | 0.18 | 0.12 |

| Mica Concentrate | 7.92 | 67.48 | 18.78 | 0.09 | 0.84 | 1.07 | 0.87 | 9.25 | 0.19 | 1.43 |

| Metal Oxide Mineral Concentrate | 2.83 | 67.10 | 19.76 | 0.87 | 1.35 | 0.60 | 0.17 | 9.14 | 0.17 | 0.84 |

| Feldspar Concentrate | 63.30 | 67.36 | 20.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.68 | 0.12 | 11.46 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| Quartz Concentrate | 14.04 | 98.03 | 1.14 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

Table 11.

Flotation test results with conventional desliming and conventional test conditions of the sample U2.

Table 11.

Flotation test results with conventional desliming and conventional test conditions of the sample U2.

| Product | Weight % | SiO2 % | Al2O3 % | Fe2O3 % | TiO2 % | CaO % | MgO % | Na2O % | K2O % | P2O5 % |

|---|

| Slime −32 μm | 9.44 | 68.87 | 19.77 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 9.97 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Slime +32 μm | 3.65 | 69.86 | 19.11 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 9.97 | 0.13 | 0.11 |

| Mica Concentrate | 4.59 | 65.79 | 19.14 | 0.10 | 0.73 | 1.50 | 0.70 | 10.05 | 0.40 | 1.59 |

| Metal Oxide Mineral Concentrate | 10.67 | 67.12 | 19.01 | 0.35 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.13 | 11.01 | 0.26 | 0.78 |

| Feldspar Concentrate | 57.09 | 67.74 | 19.97 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.69 | 0.19 | 11.10 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| Quartz Concentrate | 14.56 | 96.09 | 2.16 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 1.04 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).