1. Introduction

Petrophysical logging is a process that collects high spatial resolution data that could be integrated with the drilling process. New drilling and sensing technologies, which aim to increase efficiency and reduce the cost of exploration drilling, are being developed and commercialized by the Deep Exploration Technologies Cooperative Research Centre (DET CRC). Besides a coiled tubing rig, adapted from the oil and gas sector for mineral exploration, new measuring and sensing technologies include autonomous downhole logging-while-drilling tools (AutoSonde

TM and AutoShuttle) and top-of-hole analytical instruments (Lab-at-Rig

®) [

1]. Logging-while-drilling and top-of-hole sensing technologies provide a wide range of near real-time data, whose timely analysis and interpretation is critical for real-time decision-making.

Although petrophysical measurements do not directly map lithology in many geological environments, the measured physical properties may be related to different rock-mass features of interest such as alteration or mineralization style, texture, rock quality/strength or may indicate the presence or absence of certain minerals and metals within the rock mass. Geophysical logging has proved to be useful in several applications throughout the minerals industry, such as hole-to-hole correlation, ore body delineation, grade estimation or geotechnical characterization. For example, natural gamma logging is used for stratigraphic correlation of iron ore deposits hosted in banded iron formations (BIF). Other methods may be equally useful in correlating lithology and rock mass characteristics in other stratiform mineral deposits. Wanstedt [

2] used density, magnetic susceptibility and natural gamma logs to delineate ore from waste at a sulfide-hosted base-metal deposit in Sweden and King et al. [

3] used conductivity logging at a mine in the Sudbury complex to discriminate ore from waste in blast holes. Later, McDowell et al. [

4] used conductivity logging in conjunction with magnetic susceptibility for nickel grade estimation in the Sudbury base metal deposits. The relationship of petrophysical measurements to grade is well established for natural gamma logging and uranium grade [

5], as well as for magnetic susceptibility and iron grade in magnetite ore bodies [

6]. Predicting rock mechanical and geotechnical properties from wireline logs was demonstrated by McNally [

7] and Elkington et al. [

8].

Many studies use a range of multivariate statistical methods to automatically determine rock properties from a combination of different measurements. Pechnig et al. [

9] used linear and multi-linear regression and factor analysis on wireline log data from the German Continental Deep Drilling Program to determine lithology, porosity and fracture intensity. Maiti et al. [

10] applied neural network modelling to the same data set for lithofacies classification. Lithofacies interpretation using principal components analysis and multi-level hierarchical clustering of wireline log data was demonstrated by Ma et al. [

11], while Urbancic and Bailey [

12] applied factor analysis to geophysical well logs to delineate favorable zones for gold mineralization. The authors also showed how geophysical log signatures relate to specific halos resulting from sericitization and pyritization and thus demonstrated how these measurements might help to vector towards a deposit. Fullagar et al. [

13] have developed their own algorithm for automated rock-mass classification from geophysical borehole logs. Their algorithm uses centroids and distance measures to automatically group data, a process used in other conventional clustering algorithms. Templ et al. [

14] tested different cluster methods on regional geochemical data and offers a comprehensive discussion about the problems and possibilities of multivariate data analysis. The application of fuzzy c-means clustering to well-log data from the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) to classify the rocks with respect to their magnetic properties was demonstrated by Dekkers et al. [

15]. Imamura [

16] also used fuzzy

c-means clustering to determine engineering properties from borehole data. Thus, the fuzzy cluster approach has a track record of being successful in classifying lithologies and forms the basis of our approach.

Classifying iron ore at the resource drilling stage is an area where automated lithology classification could offer significant benefits in the efficiency of mine planning and geo-metallurgical studies. Presently, iron ore lithology and grade are classified manually from elemental assay data, usually collected in 1–3 m intervals. Turn-around times for chemical assay analysis are in the order of weeks and real-time decision making and interpretation is not possible with this workflow. The real-time method currently used for iron ore classification is manual inspection of drill chips and core on-site by a trained geologist. This method however is highly subjective and grade estimation is only about 35% correct (pers. communication and pers. experience within the iron ore industry).

Currently, the focus of the application of measurement-while-drilling (MWD, or LWD) in iron ore mining is at the drill and blast stage of mining because of the urgent need for timely data in drill-hole planning. We contend that MWD/LWD at the resource definition stage is equally important because it immediately assists decisions on what further geotechnical and geo-metallurgical studies might be needed. There is a natural tendency to follow previous practice in the absence of timely information with mine planning and work-flow decisions; thus, the reluctance to change well developed plans can outweigh the use of information that would allow early decisions to be made about de-risking the resource model and guiding the mining methods and later blending. Finding out that the resource model isn’t quite correct or as detailed as required at the drill and blast stage is too late to make efficiencies.

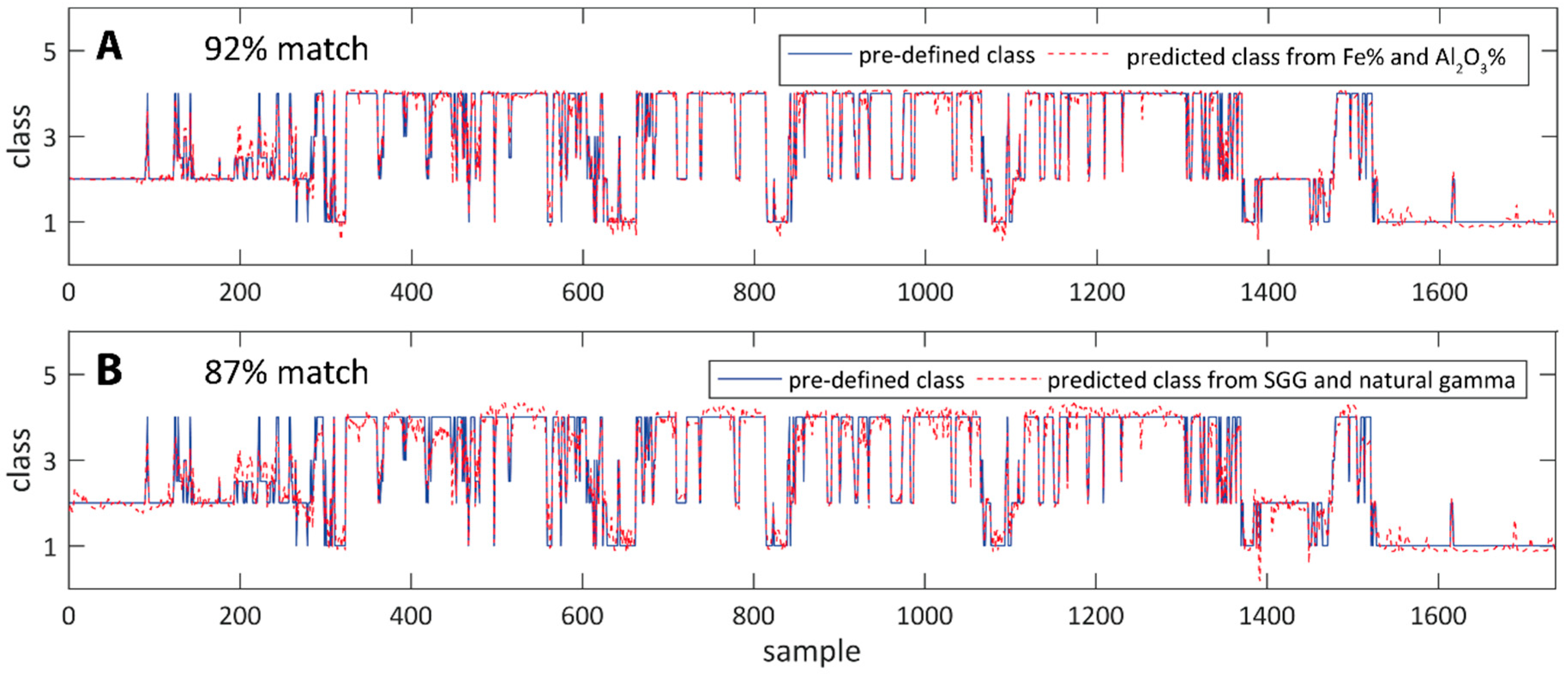

This study presents a near real-time method to predict iron ore lithology and grade with over 85% accuracy by using a neuro-adaptive learning algorithm and petrophysical downhole logs. The necessary data from natural gamma and gamma-gamma logging is of considerably higher resolution than assay data (typically one sample every 10–25 cm as opposed to 1–3 m for assay data) and can be collected in a single logging run at no extra time, and no extra cost if stacked probes are used, because the natural gamma log is currently collected by a trained logging contractor from every iron ore drill hole anyway. We use this data to generate and train fuzzy inference systems for lithology and grade prediction.

2. Materials and Methods

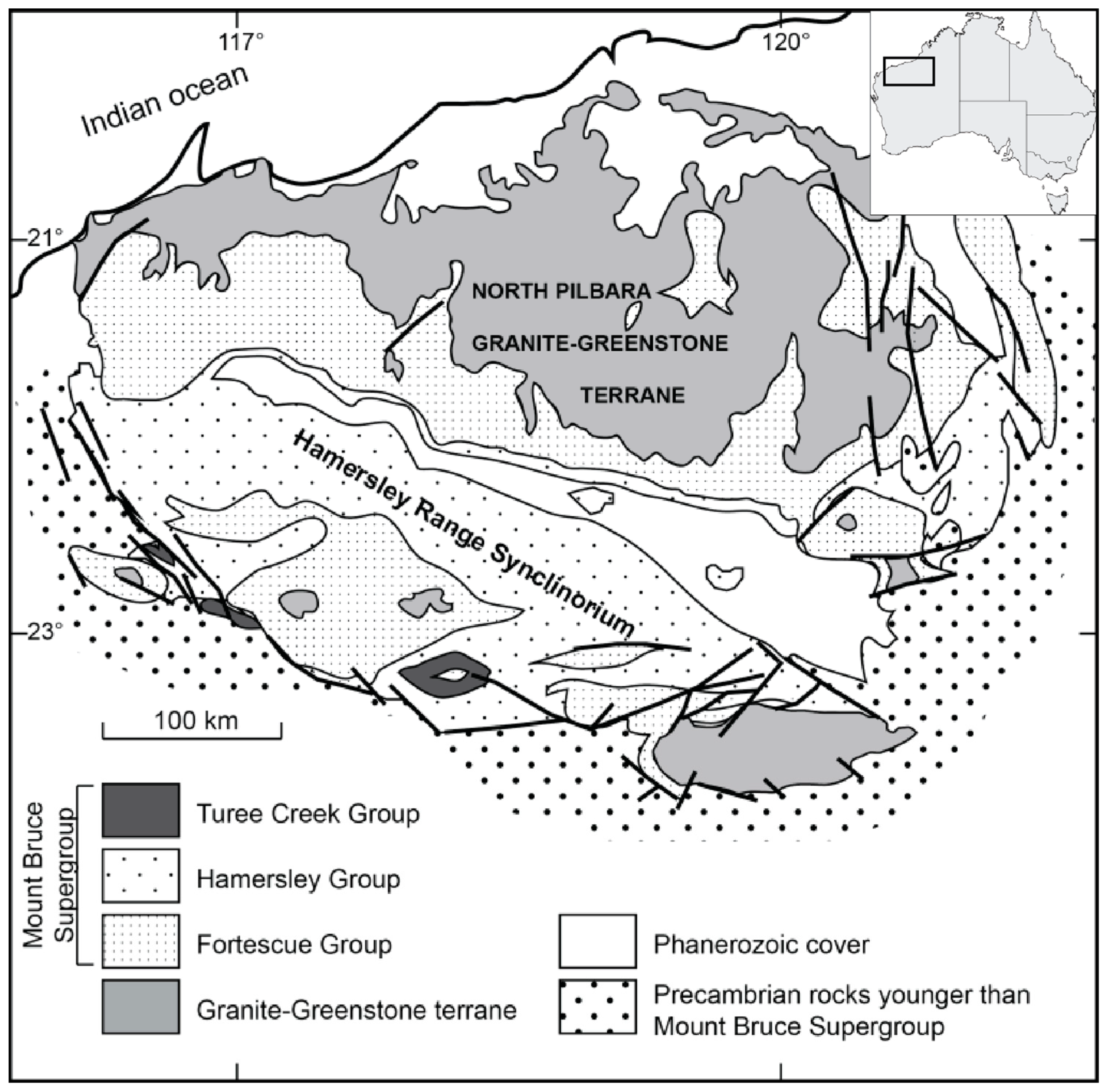

The data used in this study comes from various iron ore deposits of the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Most economically valuable iron ore deposits in this area are hosted by the Pre-Cambrian Hamersley Group that, together with the underlying Fortescue Group and overlying Wyloo Group forms the Mount Bruce Supergroup (

Figure 1). The Fortescue Group, with a maximum thickness of ~4 km, consists of mainly basic lava, pyroclastic rocks, shale and sandstone whereas the Wyloo Group can reach double the thickness and is comprised mainly of mixed clastic sediments with locally thick dolomites and basalts [

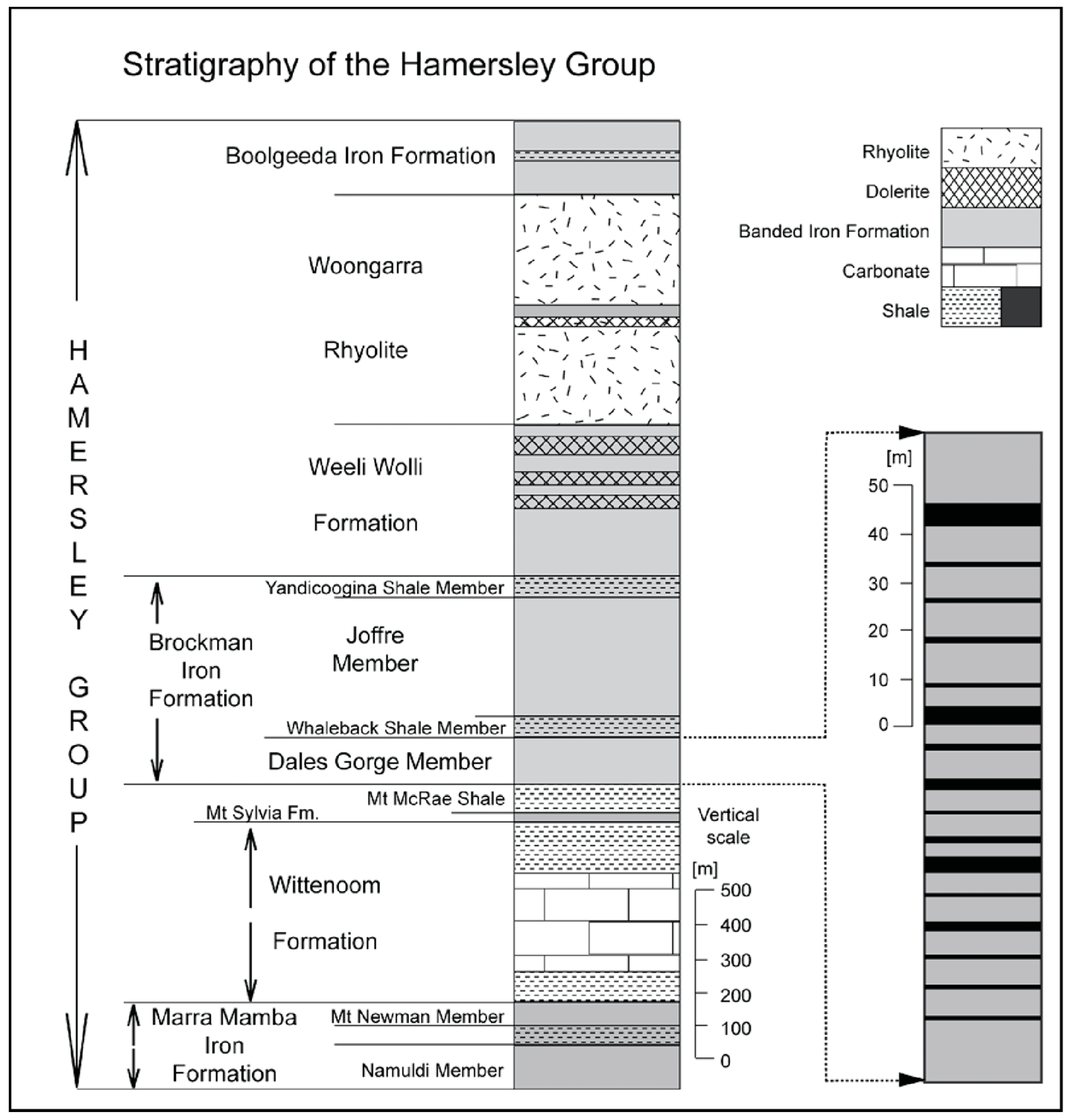

16]. The stratigraphy of the Hamersley group, shown in

Figure 2, is comprised of banded iron formations separated by major shale, carbonate or volcanic units cut by locally abundant dolerite dykes. The iron formations from oldest to youngest are: The Marra Mamba formation, the Brockman formation (with the important Dales Gorge and Joffre members) and the Boolgeeda formation. The iron formations exhibit internal macrobanding characterized by alternating BIF and shale units and are used for stratigraphic correlation due to their remarkable lateral continuity. The Dales Gorge member is comprised of 17 BIF macrobands separated by 16 shale bands that are numbered 1–16 from oldest to youngest [

17].

The data classification procedures presented in this study aims to identify and separate these different units according to their economic value. The banded iron formations, in their primary sedimentary (and metamorphosed) state, consist of chert-magnetite mesobands representing an uneconomic waste unit due to their high silica content. The economic iron ore unit consist of hematite-rich concentrations where most silica has been leached from the rock mass. Analyzing data variables that reflect these differences can successfully classify and predict of iron ore lithology and grade.

Here, we classify two iron ore data sets from some of the different iron formations present in the Pilbara region. The first comprises major element chemical assay data as well as natural gamma and density downhole logs data in 3 m intervals (863 samples in total) from one distinct iron ore prospect. The second data set comprises major element assay data in 25 cm intervals (1737 samples in total) and natural gamma, as well as spectral gamma-gamma data from four different prospects.

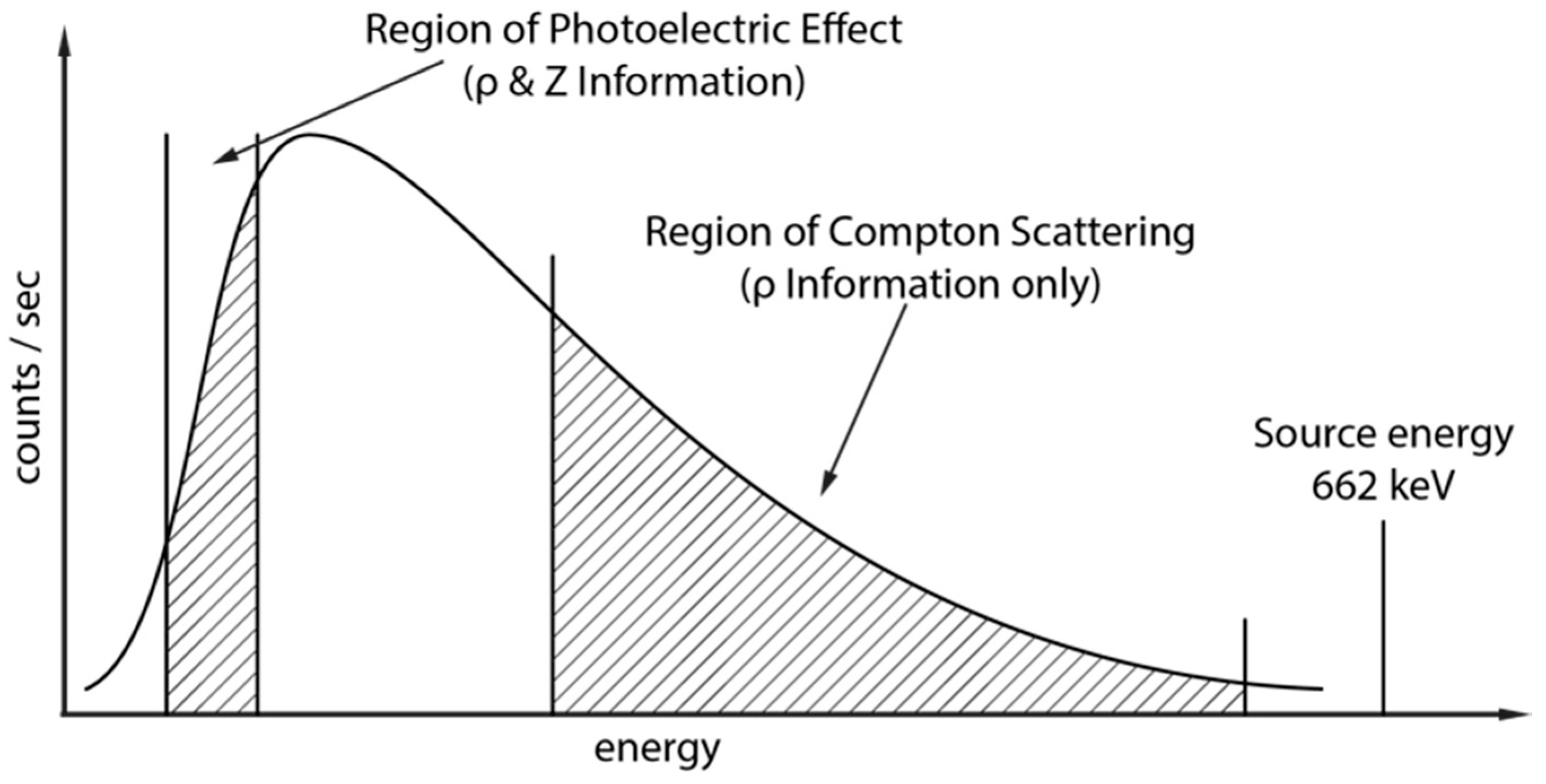

A gamma-gamma spectrum is recorded by means of the lithodensity tool which comprises a radioactive source, usually

137Cs (Caesium) with an energy of 662 keV, a long- and short-spaced detector which are shielded from the source so that they will only detect gamma rays scattered from interactions with the formation. The depth of investigation and vertical resolution depends on the detector spacing and is usually in the range of 50–60 cm. Different energy regions of the spectrum give different information about the surrounding rock mass (

Figure 3). The gamma counts in the high energy region are indicative of Compton scattering and are used to calculate formation density (bulk density), the gamma ray counts in the low energy region (below ~100 keV) are influenced by photoelectric absorption interactions and give information about density as well as the formations average (or effective) atomic number Z, which can be used as a lithology indicator. By taking the ratio of high energy to low energy counts, the density information is eliminated and the resulting number, the spectral gamma-gamma ratio (SGG ratio, [

18,

19]), should only give information about the formations average atomic number:

Due to this relationship, the SGG ratio may be used as a proxy for iron concentration in iron ore formations.

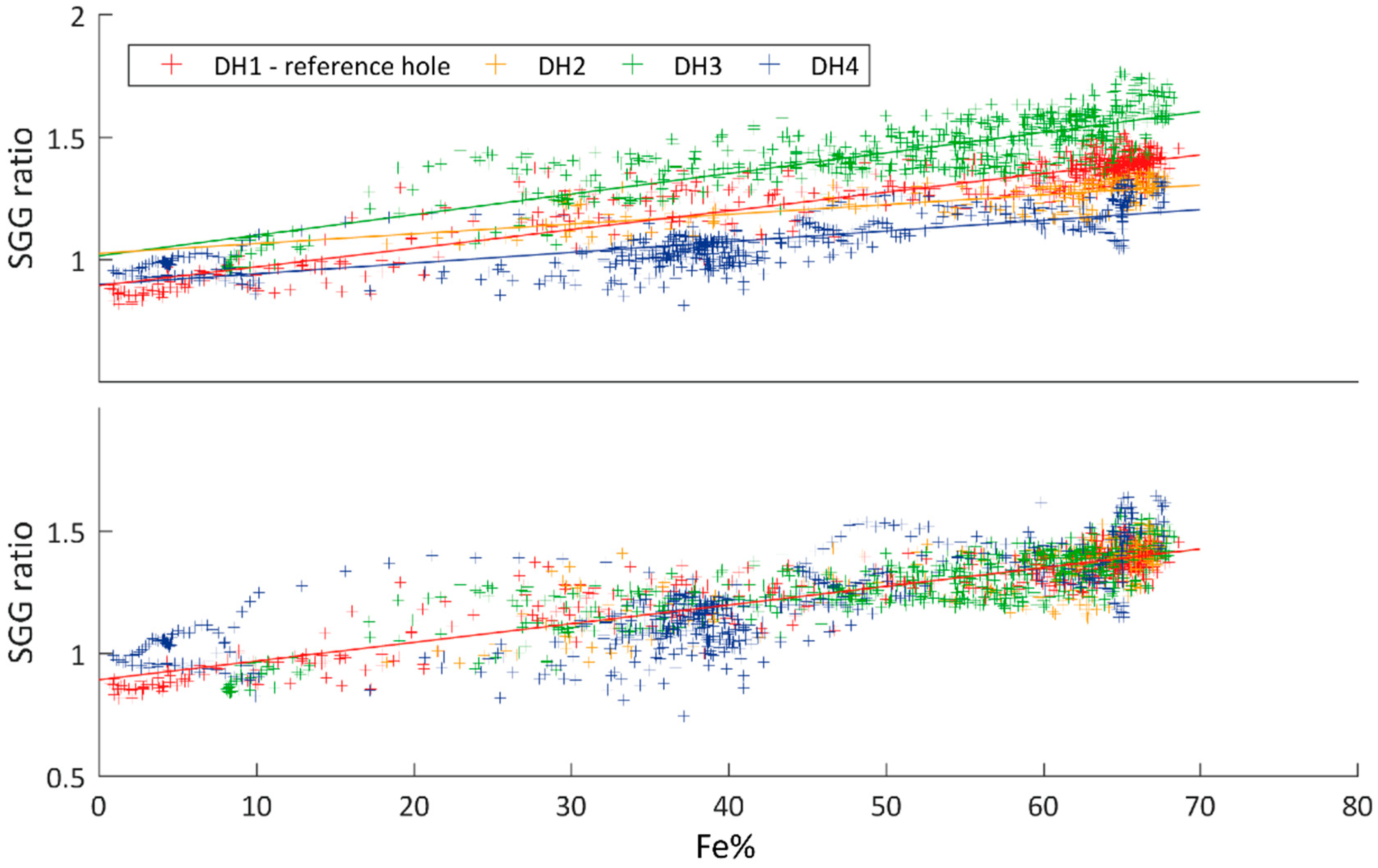

The spectral gamma-gamma logs of the second data set were recorded with an experimental Lithodensity tool (logged and made available by BHP) in four diamond drillholes from various Pilbara iron ore deposits. The logging environment and parameters differ between these holes. Two drillholes intersected the Dales Gorge member (

Figure 2), were logged through PVC casing and a Limestone matrix was applied for calibration. The third drillhole intersected the Mount Newman member overlain by the West Angela shale member and detrital cover, was logged through PVC casing and calibrated against a Limestone matrix. The remaining drillhole intersected the Joffre member, was logged through steel casing and a Sandstone matrix was applied for calibration. The calculated SGG ratio from these measurements are therefore slightly different and needed to be shifted and transformed prior to fuzzy inference modelling so that they could be evaluated together. Since the vertical resolution of the spectral log is also much higher than that of the assay data, a 200-sample moving average filter is applied to the SGG ratio and the resulting log resampled to 25 cm intervals to match the assay data. Scatter plots of SGG ratio versus iron assay are used to compare the individual trends for the four drillholes and extract the equations to adjust the trends to match (

Figure 4). The total number of samples, combined from the four drillholes (1737 samples) are then used for lithology and grade prediction through fuzzy inference modelling.

Fuzzy inference systems are based on the concepts of fuzzy set theory and fuzzy logic introduced by Zadeh [

20,

21] and their application to lithology prediction has been demonstrated in several studies [

22,

23,

24]. A fuzzy set allows for partial membership of its elements to different groups or clusters to a degree defined by the membership value [0 1]; analogous to fuzzy

c-means clustering. The fuzzy

c-means clustering algorithm groups the data into clusters based on the distances of the samples to the centroids by minimizing the following least squares objective function:

subject to

where

is the total number of sample points

z = {

z1,

z2,

…,

zn},

is the number of clusters,

is the weighting exponent (

≥ 1), and

V = {

v1,

v2,

…,

vC} are the center values.

U = {

ujk ∈ [0, 1]} is the membership matrix whose elements

ujk represent the membership degree of the

jth data point to the

kth cluster.

is the Euclidian norm. The number of clusters

c and the weighting exponent

m need to be defined prior to clustering and fuzzy inference modelling.

The fuzzy inference process maps a given set of input variables to an output by defining membership functions through the initial fuzzy c-means clustering step. The number of defined clusters dictates the number of membership functions per variable and the weighting exponent m defines the hardness (or fuzziness) of the cluster boundaries. The transformation of the crisp input values (% of element, gamma intensity etc.) into degrees of membership, represents the fuzzification process. The number of rules are also based on the number of clusters and are evaluated by means of a fuzzy operation using a logical operator (AND, OR) and operation method (MIN, MAX, probabilistic OR). The subsequent implication process truncates the rule-evaluating functions and combines them into a fuzzy set, one per rule, then these output sets are aggregated into a single fuzzy set, which is finally defuzzified to yield a single, crisp output value (class value).

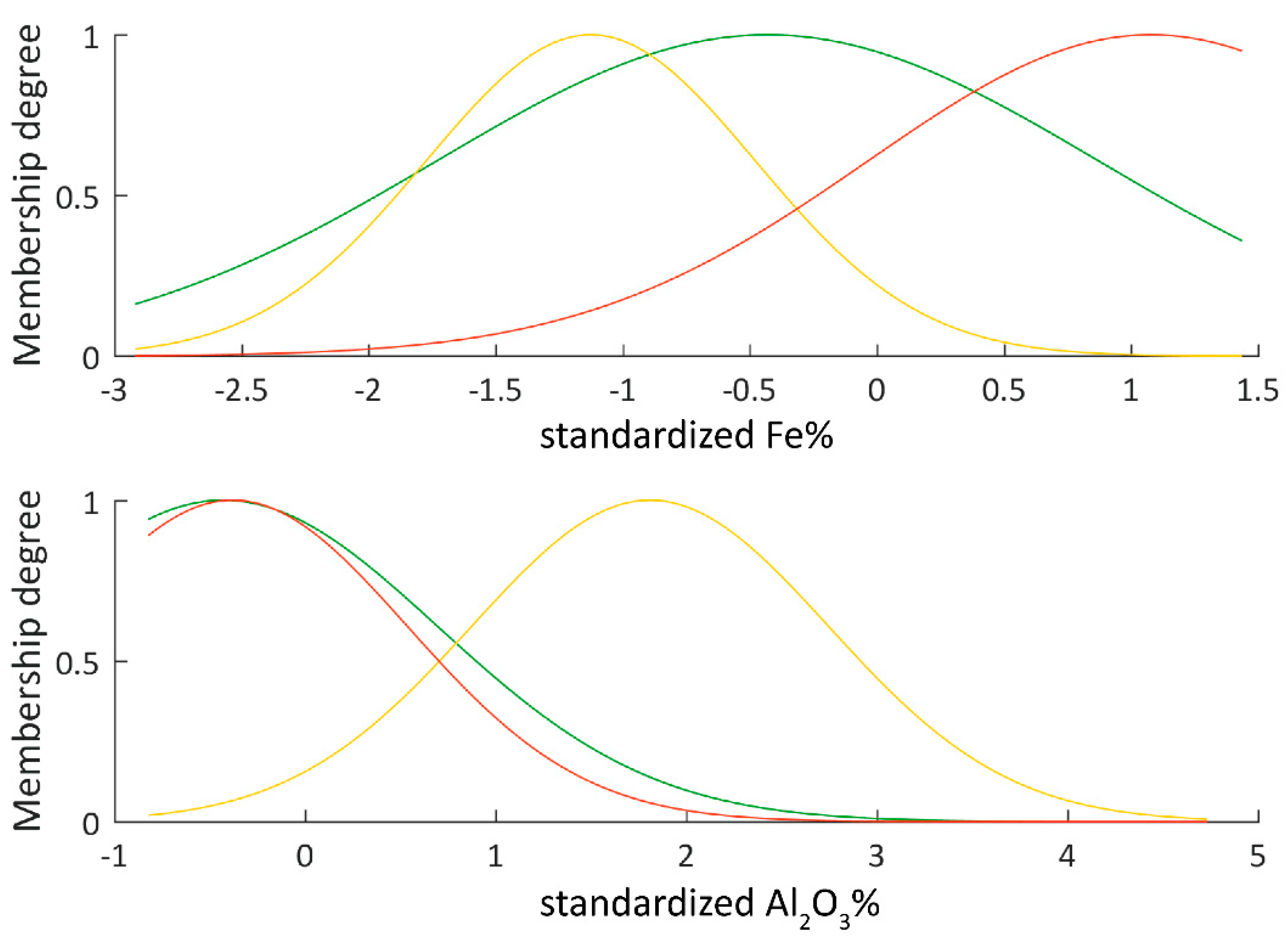

The general fuzzy inference process outlined above is illustrated on iron ore assay data from the first of the two data sets used in this study. The inference process is implemented in MATLAB using build-in functions from the statistics and machine learning toolbox, summarized in

Appendix A. The fuzzy inference system in the following example has two input variables, Fe% and Al

2O

3%, three rules and one output variable, which is the desired class value. Three membership functions (

Figure 5) per variable are defined from the initial fuzzy

c-means clustering step of these two variables into three clusters

c = 3, applying a weighting exponent of

m = 1.6. The output functions are built based on predefined output classes, which represent the typical cut-off grades used by the iron ore industry:

Class 1—waste BIF—Fe% < 50%, Al2O3% < 3%;

Class 2—waste shale—Fe% < 55%, Al2O3% > 3%;

Class 2.5—shaley ore—Fe% > 55%, Al2O3% > 3%;

Class 3—low-grade ore—Fe% > 50% and < 58%, Al2O3% < 3%;

Class 4—high-grade ore—Fe% > 58%, Al2O3% < 3%

The three rules defined for this inference system are connected by a logical ‘AND’ operator and ‘PRODUCT’ method. Written out they are:

if input 1 is in cluster 1 and input 2 is in cluster 1 then output is class 1;

if input 1 is in cluster 2 and input 2 is in cluster 2 the output is class 2;

if input 1 is in cluster 3 and input 2 is in cluster 3 then output is class 3.

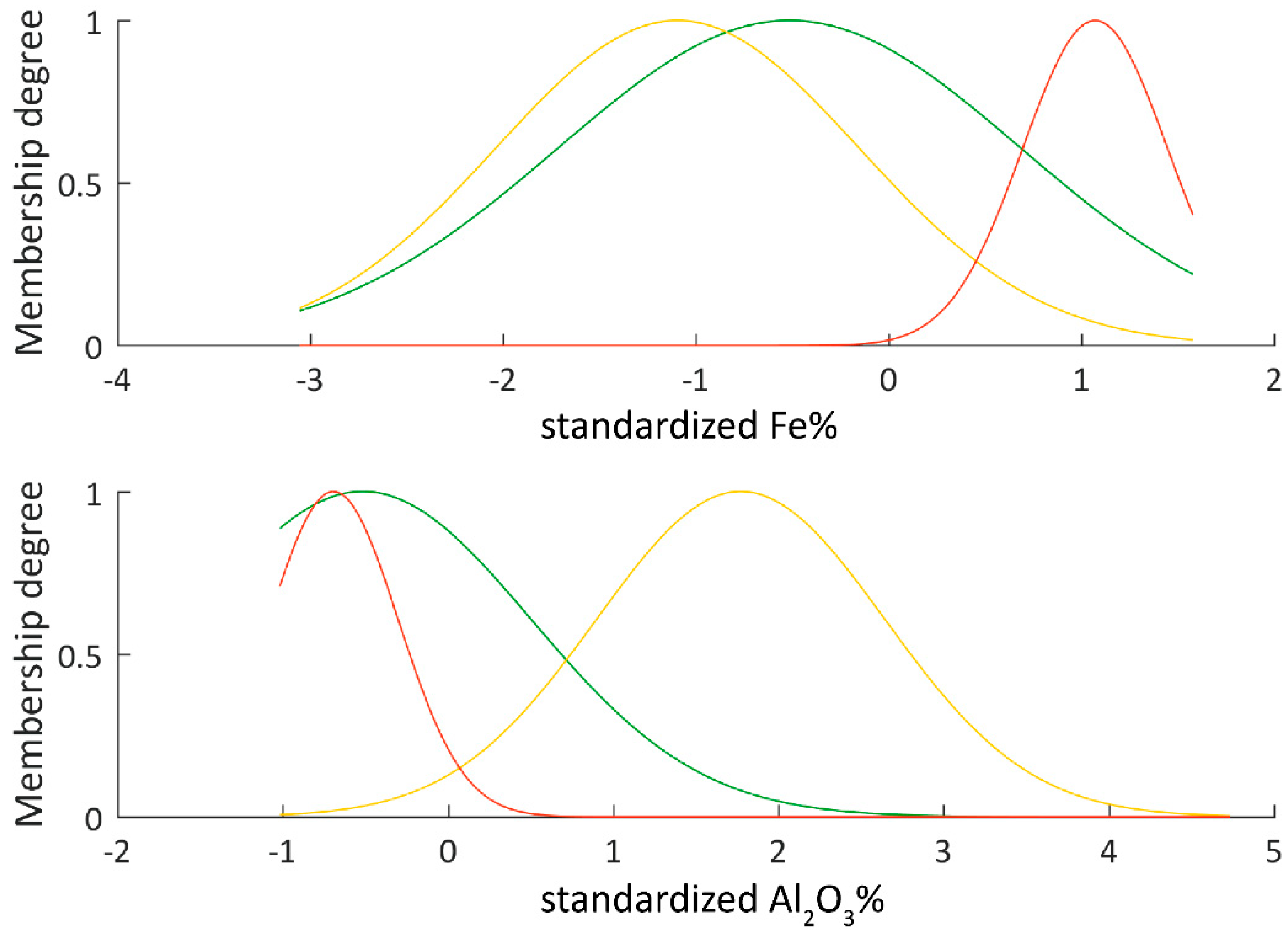

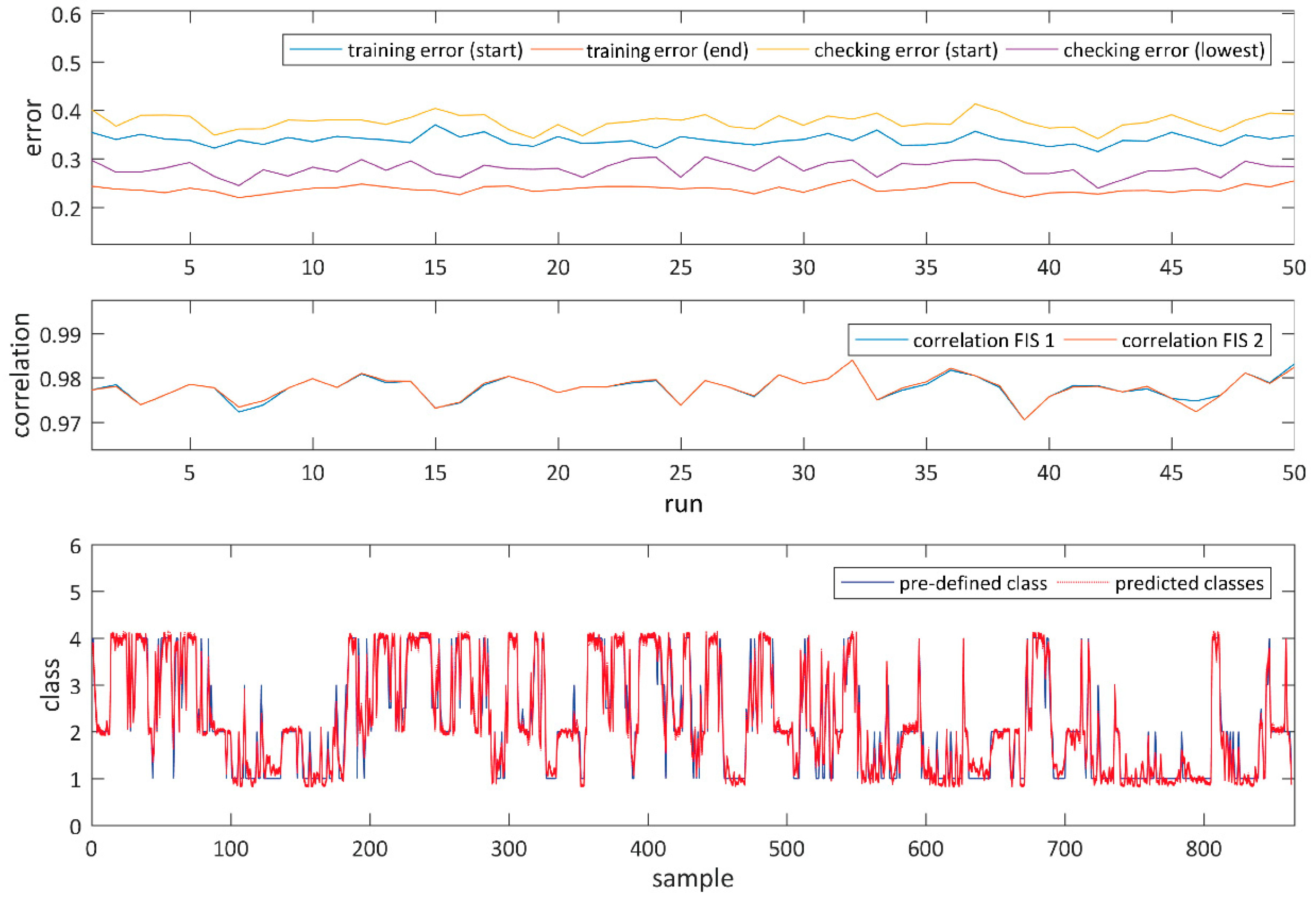

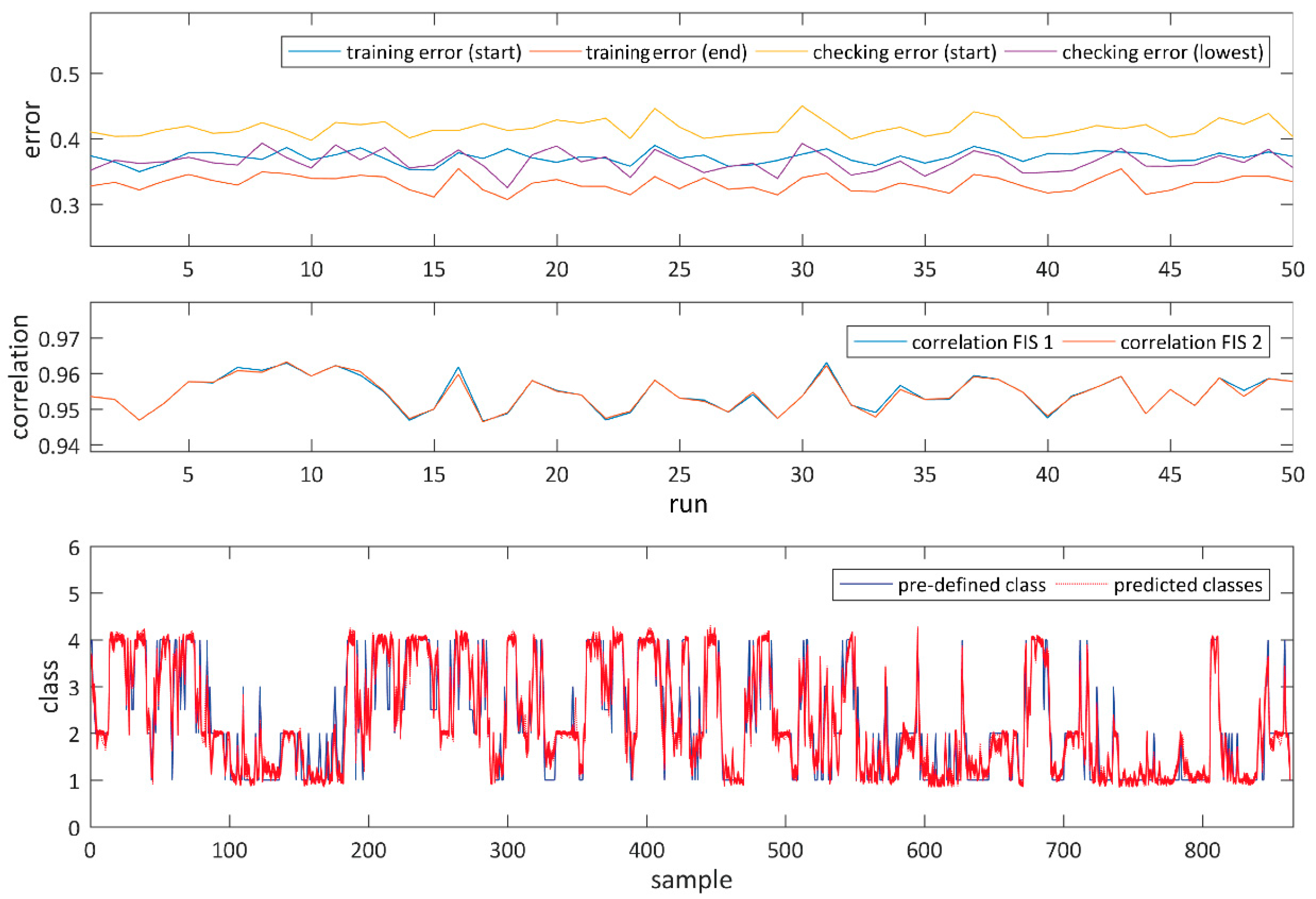

The results of the rule evaluation, implication, aggregation and defuzzification are then mapped to the output variable to yield answers in the desired range of classes from 1 to 4 as opposed to clusters 1 to 3 from the input and rule evaluation. After the initial inference system is designed, it is trained via a neuro-adaptive learning process that adjusts the parameters of the membership functions to better track the output data. A hybrid training method that uses both least squares and back propagation algorithms is run for 100 epochs to train the system. A checking data set, modified by small amounts of random noise, is evaluated in conjunction to training and the best-suited trained fuzzy inference system is chosen based on the lowest training and checking error. The adjusted membership functions plotted in

Figure 6 are considerably narrower when compared to the initial functions (

Figure 5), especially the functions defining the cluster containing iron ore samples. It should be noted that all data was standardized prior to analysis, which is why the absolute values in most plots are different from the numbers used to define the desired classes. The standard score (or z-score) is calculated according to:

where

is the new sample point,

is the original sample,

is the mean and

σ is the standard deviation.

The fuzzy inference process, regarding the evaluation of rules and generating an output value, for the initial and the trained systems is illustrated in

Figure 7. In addition to the parameters described above, the ‘minimum’ is used as the implication method to truncate the function from rule evaluation and the aggregated results are defuzzified using the weighted average method. The top plot in

Figure 7 shows the process and the resulting class before training for an input of Fe% = 1 and Al

2O

3% = 0 (standardized values). The untrained system yields a class value of 4.08, which represents high-grade ore, but the high value for aluminum suggests a high shale content and the sample should be classified as class 2 or 2.5. The value of 2.17 for the trained system represents a value in the correct range.