Anomalously High Cretaceous Paleobrine Temperatures: Hothouse, Hydrothermal or Solar Heating?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sampling and Methods

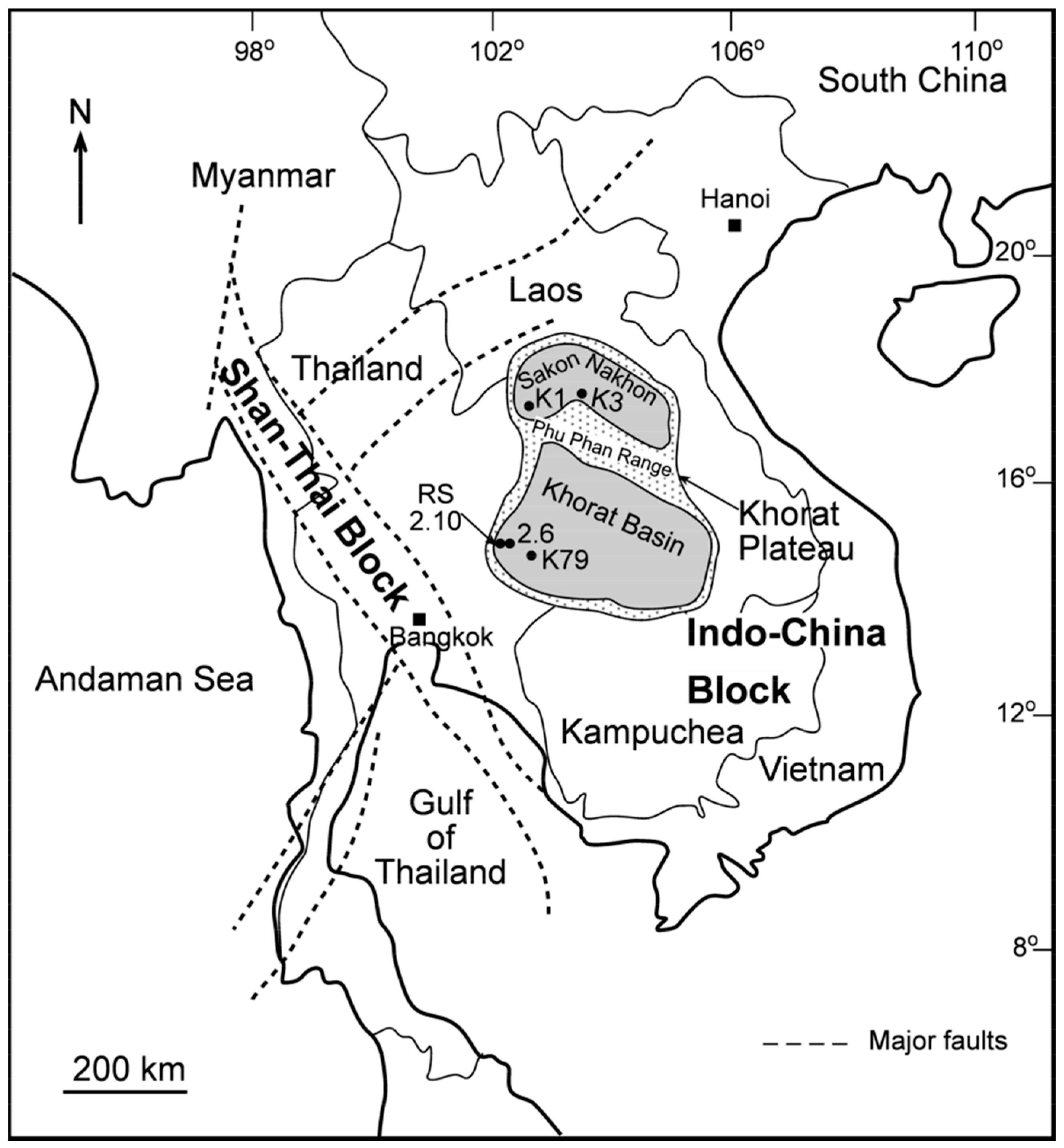

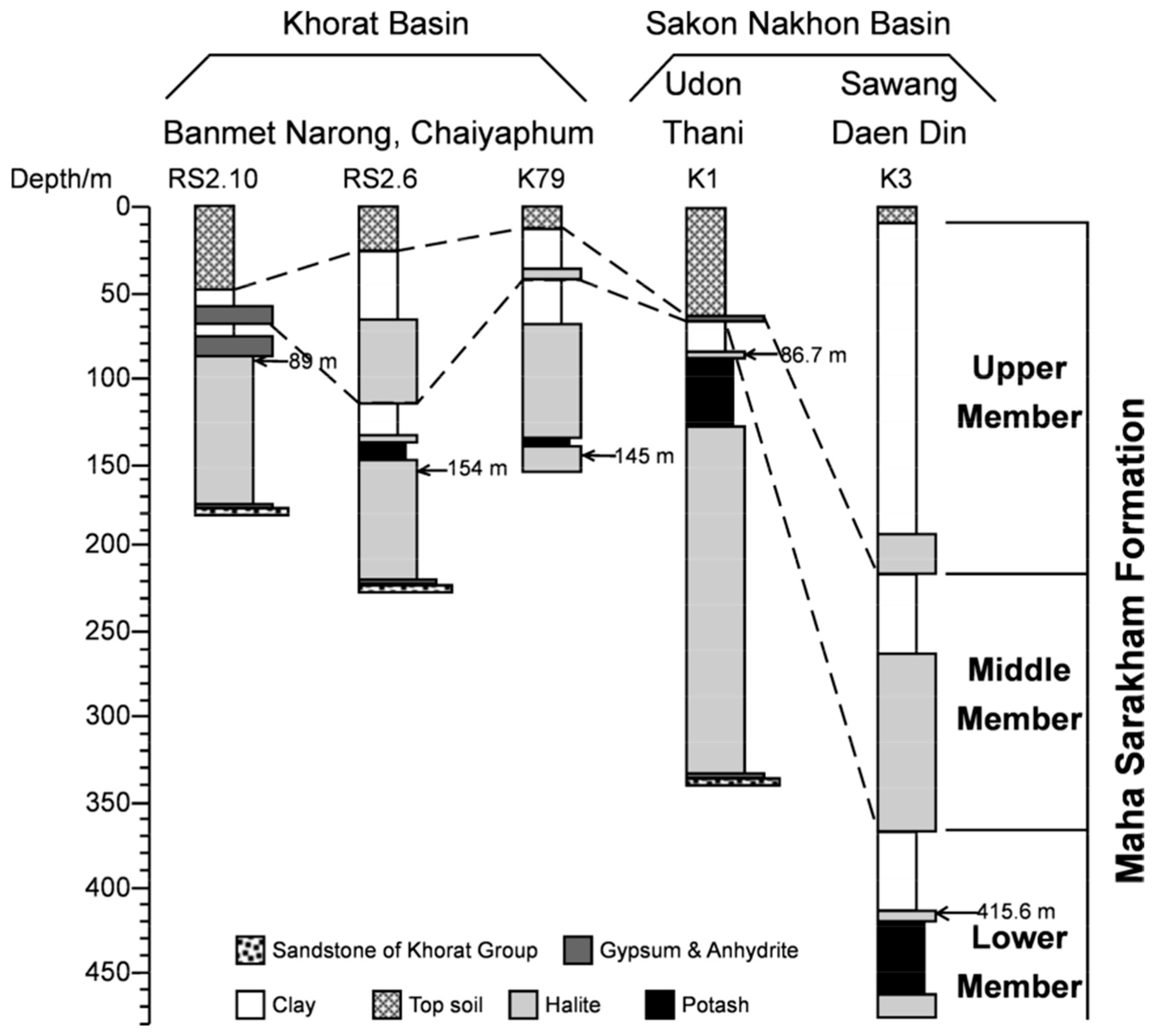

2.1. Khorat Plateau and Sampling

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Microscopy

2.2.2. X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRD)

2.2.3. Microthermometry

3. Results

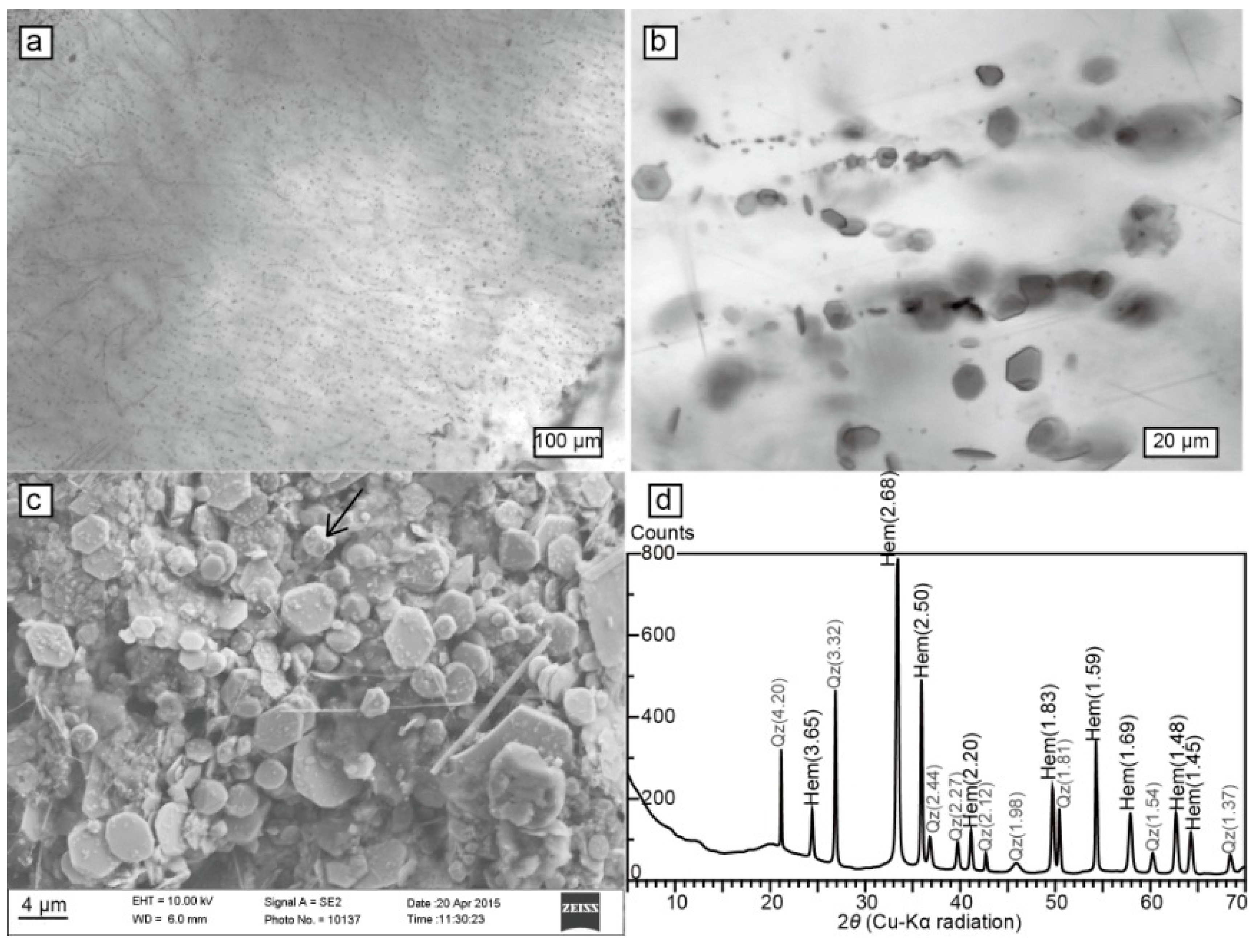

3.1. Microscopy

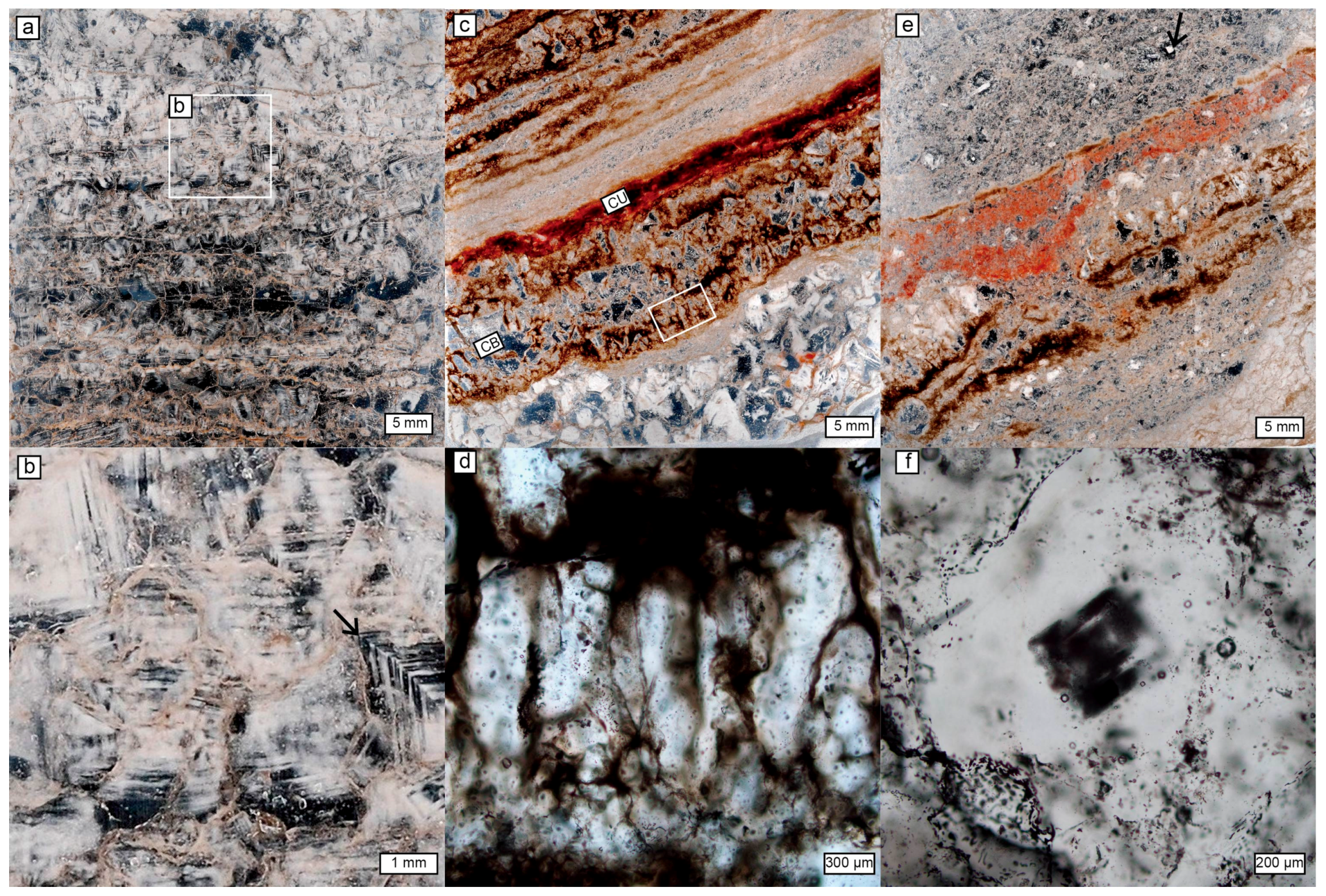

3.1.1. Khorat Halite and Fluid Inclusion Microscopy

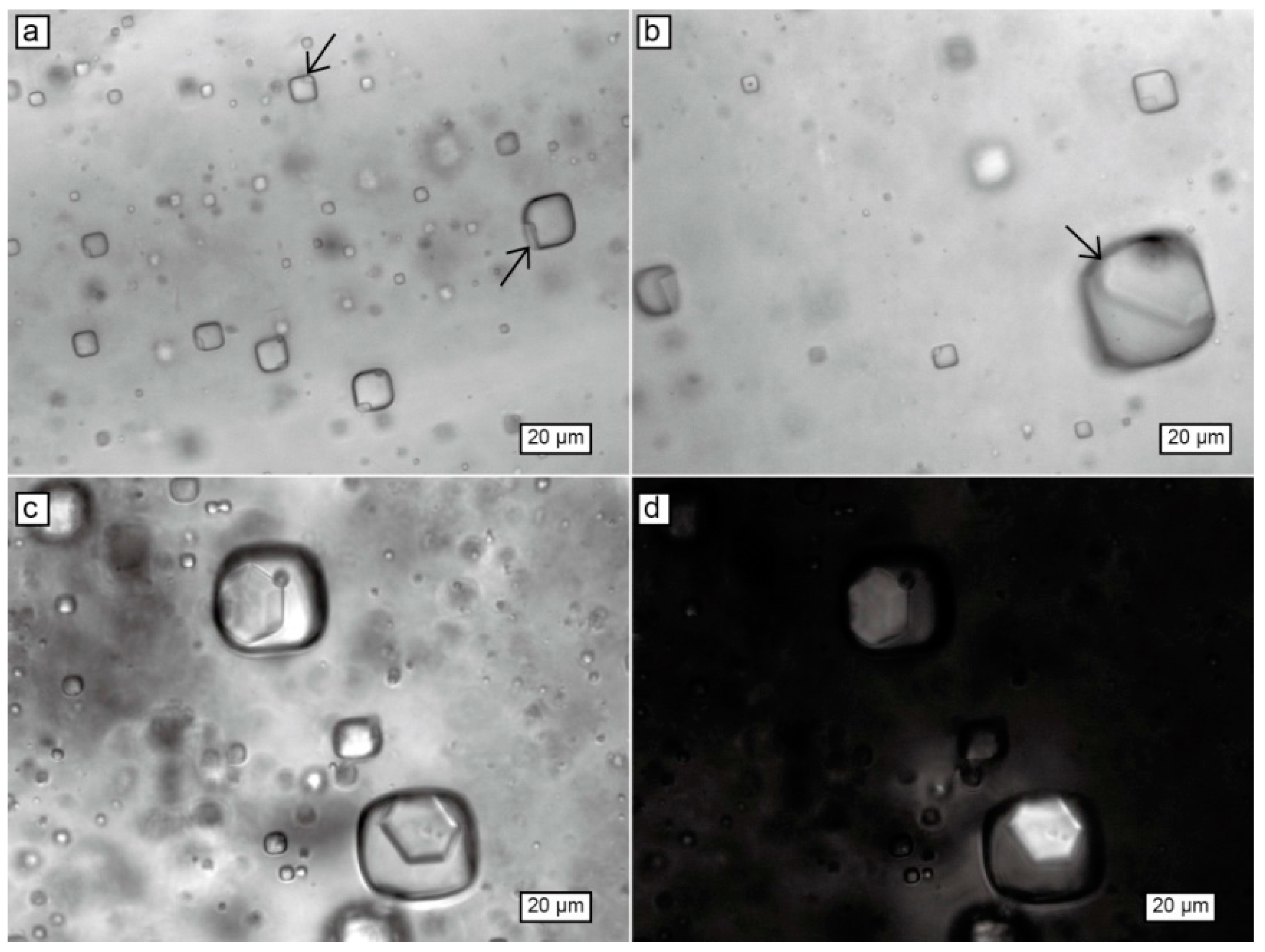

3.1.2. Daughter Crystal Microscopy

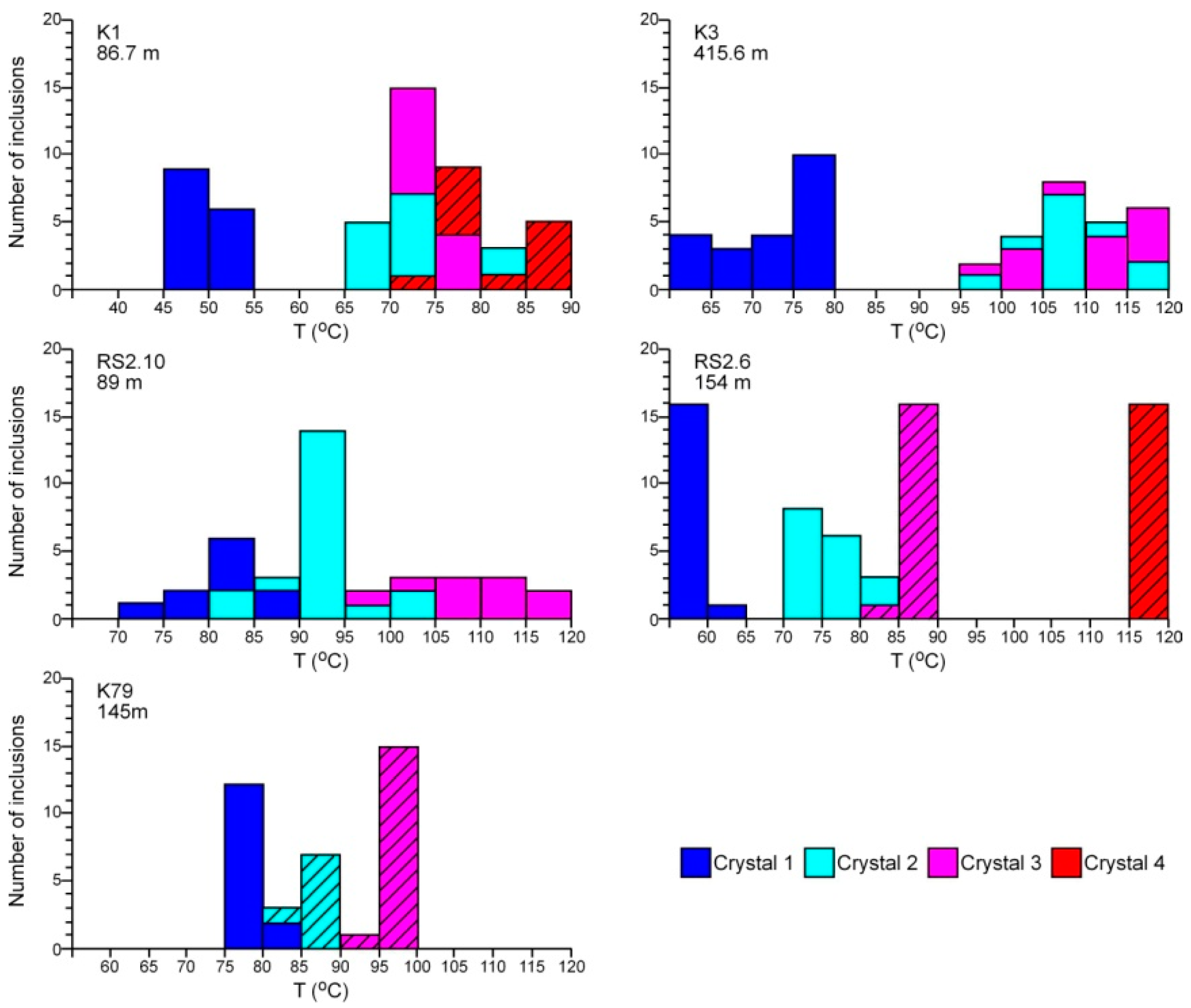

3.2. Dissolution Temperature Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Validity of Fluid-Inclusion Data

4.1.1. Primary versus Recrystallized Halite

4.1.2. Stretching, Necking, or Leakage of Fluid Inclusions

4.2. Supporting Evidence for Extremely High Temperatures: Hematite (Fe2O3)

4.3. Explanation of the High Dissolution Temperatures of Daughter Crystals in Fluid Inclusions

4.3.1. Cretaceous Climate?

4.3.2. Hydrothermal Activity?

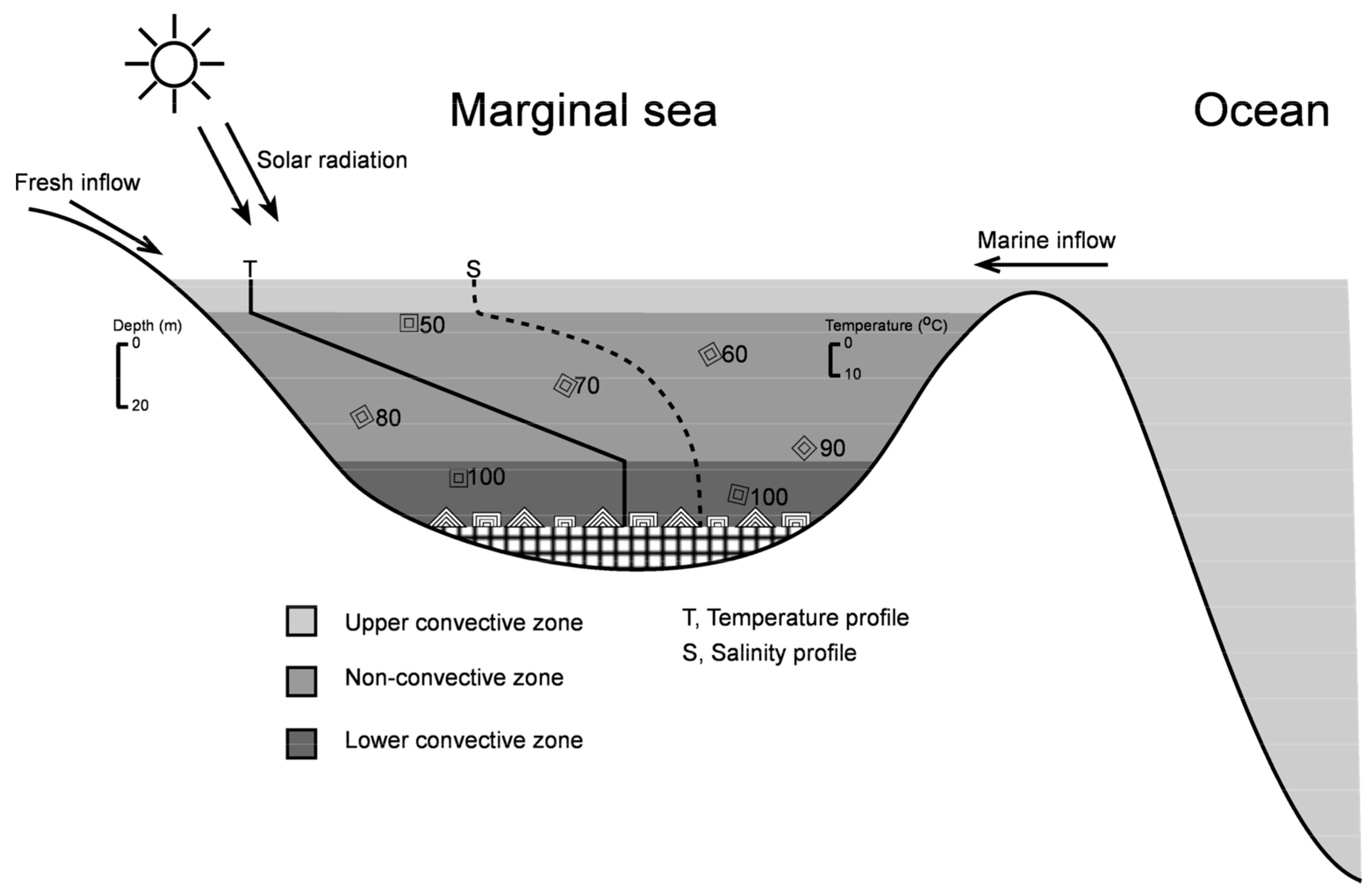

4.3.3. Solar-Heating Hypothesis: Solar Pond Effect?

5. Summary and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goldstein, R.H.; Reynolds, T.J. Systematics of Fluid Inclusions in Diagenetic Minerals SEPM Short Course 31; SEPM: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1994; pp. 1–199. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.M.; Spencer, R.J. Paleotemperatures preserved in fluid inclusions in halite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1995, 59, 3929–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, T.K.; Li, J.; Brown, C.B. Paleotemperatures from fluid inclusions in halite: Method verification and a 100,000 year paleotemperature record, Death Valley, CA. Chem. Geol. 1998, 150, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benison, K.C.; Goldstein, R.H. Permian paleoclimate data from fluid inclusions in halite. Chem. Geol. 1999, 154, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterfield, C.L.; Lowenstein, T.K.; Vreeland, R.H.; Rosenzweig, W.D. Paleobrine temperatures, chemistries, and paleoenvironments of Silurian Salina Formation F-1 Salt, Michigan Basin, USA, from petrography and fluid inclusions in halite. J. Sediment. Res. 2005, 75, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Ni, P.; Schiffbauer, J.D.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Y.; Xia, M. Ediacaran seawater temperature: Evidence from inclusions of Sinian halite. Precambrian Res. 2011, 184, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambito, J.J.; Benison, K.C. Extremely high temperatures and paleoclimate trends recorded in Permian ephemeral lake halite. Geology 2013, 41, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalevich, V.M.; Peryt, T.M.; Petrichenko, O.I. Secular variation in seawater chemistry during the Phanerozoic as indicated by brine inclusions in halite. J. Geol. 1998, 106, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, T.K.; Timofeeff, M.N.; Brennan, S.T.; Hardie, L.A.; Demicco, R.V. Oscillations in Phanerozoic seawater chemistry: Evidence from fluid inclusions. Science 2001, 294, 1086–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horita, J.; Zimmermann, H.; Holland, H.D. Chemical evolution of seawater during the Phanerozoic: Implications from the record of marine evaporites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2002, 66, 3733–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.M.; García-Veigas, J.; Lowenstein, T.K.; Giles, P.S.; Williams-Stroud, S. The major-ion composition of Carboniferous seawater. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 134, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roedder, E.; Bodnar, R. Geologic pressure determinations from fluid inclusion studies. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1980, 8, 263–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, T.K.; Spencer, R.J. Syndepositional origin of potash evaporites: Petrographic and fluid inclusion evidence. Am. J. Sci. 1990, 290, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roedder, E. Fluid inclusion studies on the porphyry-type ore deposits at Bingham, Utah, Butte, Montana, and Climax, Colorado. Econ. Geol. 1971, 66, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, F.; Kelly, W.C. Ore-forming fluids in Archean gold-bearing quartz veins at the Sigma Mine, Abitibi greenstone belt, Quebec, Canada. Econ. Geol. 1987, 82, 1464–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, Y.; Stoller, P.; Rička, J.; Frenz, M. Femtosecond lasers in fluid-inclusion analysis: Overcoming metastable phase states. Eur. J. Mineral. 2007, 19, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roedder, E. Final Report on a Study of Fluid Inclusions in Core from Gibson Dome No. 1 Bore, Paradox Basin, Utah; Open-File Report 84-696; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1984.

- Cendón, D.I.; Ayora, C.; Pueyo, J.-J. The origin of barren bodies in the Subiza potash deposit, Navarra, Spain: Implications for sylvite formation. J. Sediment. Res. 1998, 68, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrychenko, O.; Peryt, T.M.; Roulston, B. Seawater composition during deposition of Viséan evaporites in the Moncton Subbasin of New Brunswick as inferred from the fluid inclusion study of halite. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2002, 39, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrychenko, O.; Peryt, T.M.; Chechel, E.I. Early Cambrian seawater chemistry from fluid inclusions in halite from Siberian evaporites. Chem. Geol. 2005, 219, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalevych, V.M.; Marshall, T.; Peryt, T.M.; Petrychenko, Y.; Zhukova, S.A. Chemical composition of seawater in Neoproterozoic: Results of fluid inclusion study of halite from Salt Range (Pakistan) and Amadeus Basin (Australia). Precambrian Res. 2006, 144, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovnyuk, S.; Czapowski, G. Generation of primary sylvite: The fluid inclusion data from the Upper Permian (Zechstein) evaporites, SW Poland. In Evaporites through Space and Time; Schreiber, B.C., Lugli, S., Bąbel, M., Eds.; Geological Society, Special Publications: London, UK, 2007; Volume 285, pp. 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Hite, R.J.; Japakasetr, T. Potash deposits of the Khorat plateau, Thailand and Laos. Econ. Geol. 1979, 74, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Tabakh, M.; Utha-Aroon, C.; Schreiber, B.C. Sedimentology of the Cretaceous Maha Sarakham evaporites in the Khorat Plateau of northeastern Thailand. Sediment. Geol. 1999, 123, 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, I. Origin and assembly of south-east Asian continental terranes. In Gondwana and Tethys; Audley-Charles, M.G., Hallam, A., Eds.; Geological Society, Special Publications: London, UK, 1988; Volume 37, pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mouret, C. Geological history of northeastern Thailand since the Carboniferous. Relations with Indochina and Carboniferous to Early Cenozoic evolution model. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Stratigraphic Correlation of Southeast Asia, Bangkok, Thailand, 15–20 November 1994; pp. 132–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sattayarak, N.; Polachan, S.; Charusirisawad, R. Cretaceous rock salt in the northeastern part of Thailand (Abstract). In Proceedings of the 7th Regional Conference Geology and Mineral Resources Southeast Asia (GEOSEA VII), Bangkok, Thailand, 5–8 November 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.F.L.; Stokes, R.B.; Bristow, C.; Carter, A. Mid-Cretaceous inversion in the northern Khorat Plateau of Lao PDR and Thailand. In Tectonic Evolution of Southeast Asia; Hall, R., Blundell, D.J., Eds.; Geological Society, Special Publications: London, UK, 1996; Volume 106, pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Utha-Aroon, C. Continental origin of the Maha Sarakham evaporites, northeastern Thailand. J. Southeast Asian Earth Sci. 1993, 8, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Tabakh, M.; Schreiber, B.C.; Utha-Aroon, C.; Coshell, L.; Warren, J.K. Diagenetic origin of basal anhydrite in the Cretaceous Maha Sarakham salt: Khorat Plateau, NE Thailand. Sedimentology 1998, 45, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeff, M.N.; Lowenstein, T.K.; da Silva, M.A.M.; Harris, N.B. Secular variation in the major-ion chemistry of seawater: Evidence from fluid inclusions in Cretaceous halites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2006, 70, 1977–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardlaw, N.; Schwerdtner, W. Halite-anhydrite seasonal layers in the middle Devonian Prairie evaporite formation, Saskatchewan, Canada. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1966, 77, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, T.K.; Hardie, L.A. Criteria for the recognition of salt-pan evaporites. Sedimentology 1985, 32, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.R.; Lowenstein, T.K.; Brown, C.B.; Ku, T.L.; Luo, S. A 100 ka record of water tables and paleoclimates from salt cores, Death Valley, California. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. 1996, 123, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Lowenstein, T.K.; Fang, X.M. Microbial habitability and Pleistocene aridification of the Asian interior. Astrobiology 2016, 16, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirota, I.; Enzel, Y.; Lensky, N.G. Temperature seasonality control on modern halite layers in the Dead Sea: In situ observations. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2017, 129, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roedder, E.; Belkin, H. Application of studies of fluid inclusions in Permian Salado salt, New Mexico, to problems of siting the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant. In Scientific Basis for Nuclear Waste Management; McCarthy, G.J., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume 1, pp. 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar, R.J.; Bethke, P.M. Systematics of stretching of fluid inclusions; I, Fluorite and sphalerite at 1 atmosphere confining pressure. Econ. Geol. 1984, 79, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardlaw, N.C. Carnallite-sylvite relationships in the Middle Devonian Prairie evaporite formation, Saskatchewan. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1968, 79, 1273–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braitsch, O. Salt Deposits: Their Origin and Composition; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1971; pp. 1–297. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, G.; Kyser, T.K.; Enkin, R.; Irving, E. Paleomagnetic and isotopic evidence for the diagenesis and alteration of evaporites in the Paleozoic Elk Point Basin, Saskatchewan, Canada. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1997, 34, 1619–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrizac, J.; Riveros, P. The precipitation of hematite from ferric chloride media at atmospheric pressure. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 1999, 30, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros, P.; Dutrizac, J. The precipitation of hematite from ferric chloride media. Hydrometallurgy 1997, 46, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Zapata, J.; Padilla, R. Effect of variables on the quality of hematite precipitated from sulfate solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2007, 89, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duce, R.A.; Tindale, N.W. Atmospheric transport of iron and its deposition in the ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1991, 36, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarduno, J.; Brinkman, D.; Renne, P.; Cottrell, R.; Scher, H.; Castillo, P. Evidence for extreme climatic warmth from Late Cretaceous Arctic vertebrates. Science 1998, 282, 2241–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkyns, H.C.; Forster, A.; Schouten, S.; Damsté, J.S.S. High temperatures in the late Cretaceous Arctic Ocean. Nature 2004, 432, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steuber, T.; Rauch, M.; Masse, J.-P.; Graaf, J.; Malkoč, M. Low-latitude seasonality of Cretaceous temperatures in warm and cold episodes. Nature 2005, 437, 1341–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardie, L.A. The roles of rifting and hydrothermal CaCl2 brines in the origin of potash evaporites; a hypothesis. Am. J. Sci. 1990, 290, 43–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenstein, T.K.; Risacher, F. Closed basin brine evolution and the influence of Ca-Cl inflow waters: Death Valley and Bristol Dry Lake California, Qaidam Basin, China, and Salar de Atacama, Chile. Aquat. Geochem. 2009, 15, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, J.G.; Hutchinson, R.W. Potash-bearing evaporites in the Danakil area, Ethiopia. Econ. Geol. 1968, 63, 124–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonfiantini, R.; Borsi, S.; Ferrara, G.; Panichi, C. Isotopic composition of waters from the Danakil depression (Ethiopia). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1973, 18, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalecsinsky, A. Ueber die ungarischen warmen und heissen Kochsalzseen als natürliche Wärmeaccumulatoren, sowie über die Herstellung von warmen Salzseen und Wärmeaccumulatoren. Ann. Phys. 1902, 7, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G. Some limnological features of a shallow saline meromictic lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1958, 3, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Wellman, H. Lake Vanda: An Antarctic lake: Lake Vanda as a solar energy trap. Nature 1962, 196, 1171–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Por, F. Solar Lake on the shores of the Red Sea. Nature 1968, 218, 860–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, P.; Sonnenfeld, P. Hot brines on Los Roques, Venezuela. Science 1974, 185, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurtsbaugh, W.A.; Berry, T.S. Cascading effects of decreased salinity on the plankton chemistry, and physics of the Great Salt Lake (Utah). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1990, 47, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angino, E.E.; Armitage, K.B.; Tash, J.C. Physicochemical limnology of Lake Bonney, Antarctica. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1964, 9, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, H. Non-convecting solar ponds. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 1980, 295, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sebaii, A.; Ramadan, M.; Aboul-Enein, S.; Khallaf, A. History of the solar ponds: A review study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3319–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Walton, J.C.; Swift, A.H. Desalination coupled with salinity-gradient solar ponds. Desalination 2001, 136, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubel, K.A.; Lowenstein, T.K. Criteria for the recognition of shallow-perennial-saline-lake halites based on recent sediments from the Qaidam Basin, western China. J. Sediment. Res. 1997, 67, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

| Location | Age | Crystal | T (°C) | Daughter crystal | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhine Graben, France | Oligocene | chevron | 20–83 | sylvite | [13] |

| Subiza mine, Spain | Late Eocene | chevron | 50–110 | sylvite | [18] |

| Khorat Plateau, Thailand | Late Cretaceous | chevron | 45.7–119.5 | Sylvite + carnallite | This study |

| Zechstein Basin, Poland | Late Permian | chevron | 50–62 | sylvite | [22] |

| Carlsbad, New Mexico, USA | Permian | chevron | 28–150 | sylvite | [13] |

| Paradox Basin, USA | Early Pennsylvanian | chevron | 56–57 | carnallite | [17] |

| recrystallized | 98–120 | ||||

| Moncton Subbasin, Canada | Early Carboniferous | chevron | 50–60 | sylvite | [19] |

| Saskatchewan, Canada | Devonian | chevron | 5–80 | Sylvite + carnallite | [13] |

| East Siberian, Russia | Early Cambrian | chevron | 60–86 | Sylvite + carnallite | [20] |

| diagenetic | 70–116 | ||||

| Salt Range, Pakistan | Neoproterozoic | recrystallized | 55–100 | sylvite | [21] |

| Amadeus Basin, Australia | 60–62 |

| Sample | Crystal | T (°C) | Average (°C) | σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 86.7 m | Cumulate | 45.7, 46.4, 46.5, 46.8, 47.3, 47.5, 47.8, 49.2, 49.8, 50.6, 51.5, 51.9, 53.3, 54.1, 54.7 | 49.5 | 3.0 |

| Cumulate | 65.4, 66.5, 66.9, 69.2, 69.5, 70.3, 70.5, 71.8, 72.8, 74.1, 74.8, 81.2, 82.5, 84.3 | 72.8 | 6.0 | |

| Cumulate | 71.4, 71.6, 72.1, 72.2, 72.3, 72.4, 72.7, 73.4, 73.6, 73.8, 73.9, 74.1, 74.4, 74.5, 74.8, 75.3, 76.1, 79.5, 79.8 | 74.1 | 2.3 | |

| Chevron | 74.8(79.4), 76.1(74.8), 76.3(74.1), 76.8(76.2), 77.5 (75.5), 77.9(77.6), 78.2(78.4), 78.6(79.3), 79.1(82.6), 79.3(78.9), 81.2(80.8), 86.7(78.3), 86.8(86.1), 88.2(78), 89.2(82.8), 89.6(84.5) | 81.0 | 5.2 | |

| K3 415.6 m | Cumulate | 62.1, 62.3, 62.5, 63.6, 68.5, 68.5, 68.7,71.2, 72.1, 72.4, 73.4, 75.3, 75.3, 75.4, 76.3, 77.5, 78.4, 78.9, 79.1, 79.4, 79.6 | 72.4 | 6.0 |

| Cumulate | 95.2, 102.1, 103.6, 104.6, 104.6, 105.4, 106.1, 106.6, 106.8, 107.2, 107.9, 108.8, 110.7, 111.1, 111.9, 112.8, 114.2, 116.1, 119.5 | 107.4 | 6.3 | |

| Cumulate | 96.6, 98.8, 103.7, 104.1, 104.3, 105.2, 105.5, 106.2, 106.5, 107, 107.4, 108.5, 109.2, 112.9, 113.8, 115, 115.5, 115.9, 116, 117.2, 118.3, 119.7 | 109.4 | 6.4 | |

| RS2.10 89 m | Cumulate | 74.3, 77.2, 79.8, 80.4, 80.5, 81.3, 81.7, 82.4, 82.8, 85.2, 87.1 | 81.2 | 3.5 |

| Cumulate | 80.7, 84.5, 86.9, 88.4, 88.5, 90.4, 90.5, 90.6, 91.4, 91.5, 91.5, 91.6, 92.3, 92.3, 92.4, 92.6, 92.7, 93.2, 97.1, 101.6, 104.8 | 91.7 | 5 | |

| Cumulate | 98.6, 98.9, 100.5, 102.7, 104.4, 106.5, 107.5, 109.5, 112.6, 113.1, 113.5, 115.1, 115.3 | 107.6 | 6.1 | |

| RS2.6 154 m | Cumulate | 55.5(57.4), 56.4(54.2), 56.5(57.4), 56.7(56.5), 56.8(57.3), 57.3(56.9), 57.4(55.1), 57.5(58.4), 57.6(54.1), 58.3(60.2), 58.3(56.5), 58.3(59.1), 58.4(56.3), 58.7(59.2), 58.7(58.3), 59.4(57.7), 63.2(58.9) | 57.9 | 1.8 |

| Cumulate | 70.1, 70.5, 71.2, 71.3, 73.4, 73.5, 73.6, 74.6, 75.4, 75.8, 75.8, 76.3, 78.4, 79.2, 80.2, 81.1, 81.7 | 75.4 | 3.7 | |

| Chevron | 83.2, 85.3, 85.4, 87.4, 87.6, 87.6, 88.2, 88.3, 88.3, 88.4, 88.5, 88.6, 88.9, 89.3, 89.6, 89.9 | 87.8 | 1.7 | |

| Chevron | 115.2, 115.4, 115.7, 115.8, 116.2, 116.2, 116.4, 116.8, 116.8, 117.6, 118.3, 118.5, 118.6, 118.7, 119.2, 119.2 | 117.2 | 1.4 | |

| K79 145 m | Cumulate | 77.6(78.2), 77.9(76.7), 78.2(78.9), 78.3(77.9), 78.5(78.8), 78.5(78.3), 78.6(79.4), 78.6(79.6), 79.1(78.1), 79.3(79.4), 79.4(76.4), 79.6(79.3), 80.1(79.4), 82.2(82.7) | 80.0 | 1.1 |

| Chevron | 83.8, 84.1, 84.2, 85.2, 85.2, 85.2, 85.7, 85.9, 86.4, 87.1 | 85.4 | 1.0 | |

| Chevron | 94.3, 95.2, 95.3, 95.8, 95.9, 96, 96.1, 96.2, 96.3, 96.5, 96.7, 96.8, 97, 97.1, 97.6, 98 | 96.3 | 1.0 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Lowenstein, T.K. Anomalously High Cretaceous Paleobrine Temperatures: Hothouse, Hydrothermal or Solar Heating? Minerals 2017, 7, 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/min7120245

Wang J, Lowenstein TK. Anomalously High Cretaceous Paleobrine Temperatures: Hothouse, Hydrothermal or Solar Heating? Minerals. 2017; 7(12):245. https://doi.org/10.3390/min7120245

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiuyi, and Tim K. Lowenstein. 2017. "Anomalously High Cretaceous Paleobrine Temperatures: Hothouse, Hydrothermal or Solar Heating?" Minerals 7, no. 12: 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/min7120245

APA StyleWang, J., & Lowenstein, T. K. (2017). Anomalously High Cretaceous Paleobrine Temperatures: Hothouse, Hydrothermal or Solar Heating? Minerals, 7(12), 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/min7120245