Using TESPT to Improve the Performance of Kaolin in NR Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

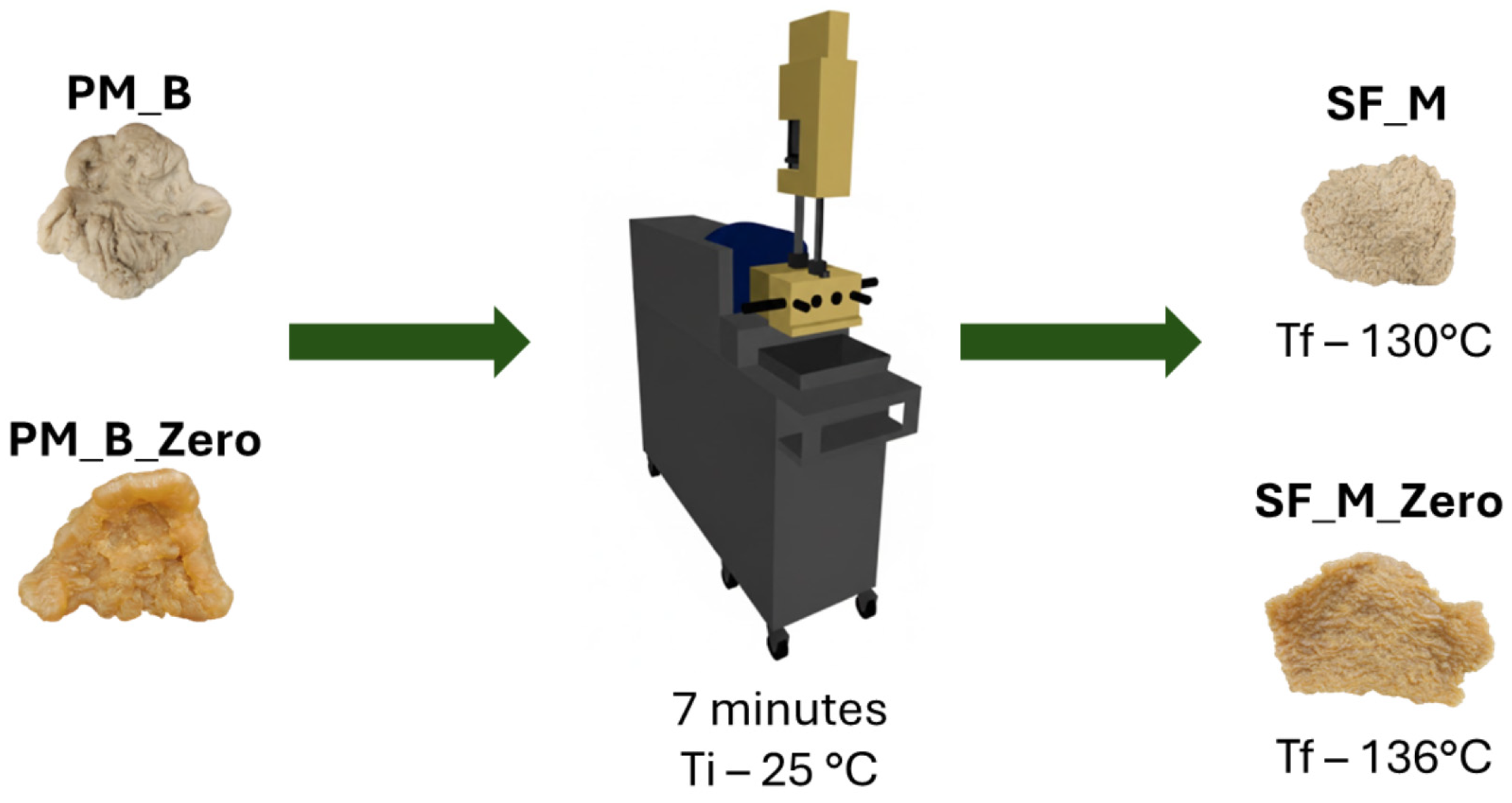

2.2.1. Part 1—Evaluation of Kaolin/Natural Rubber Mixtures

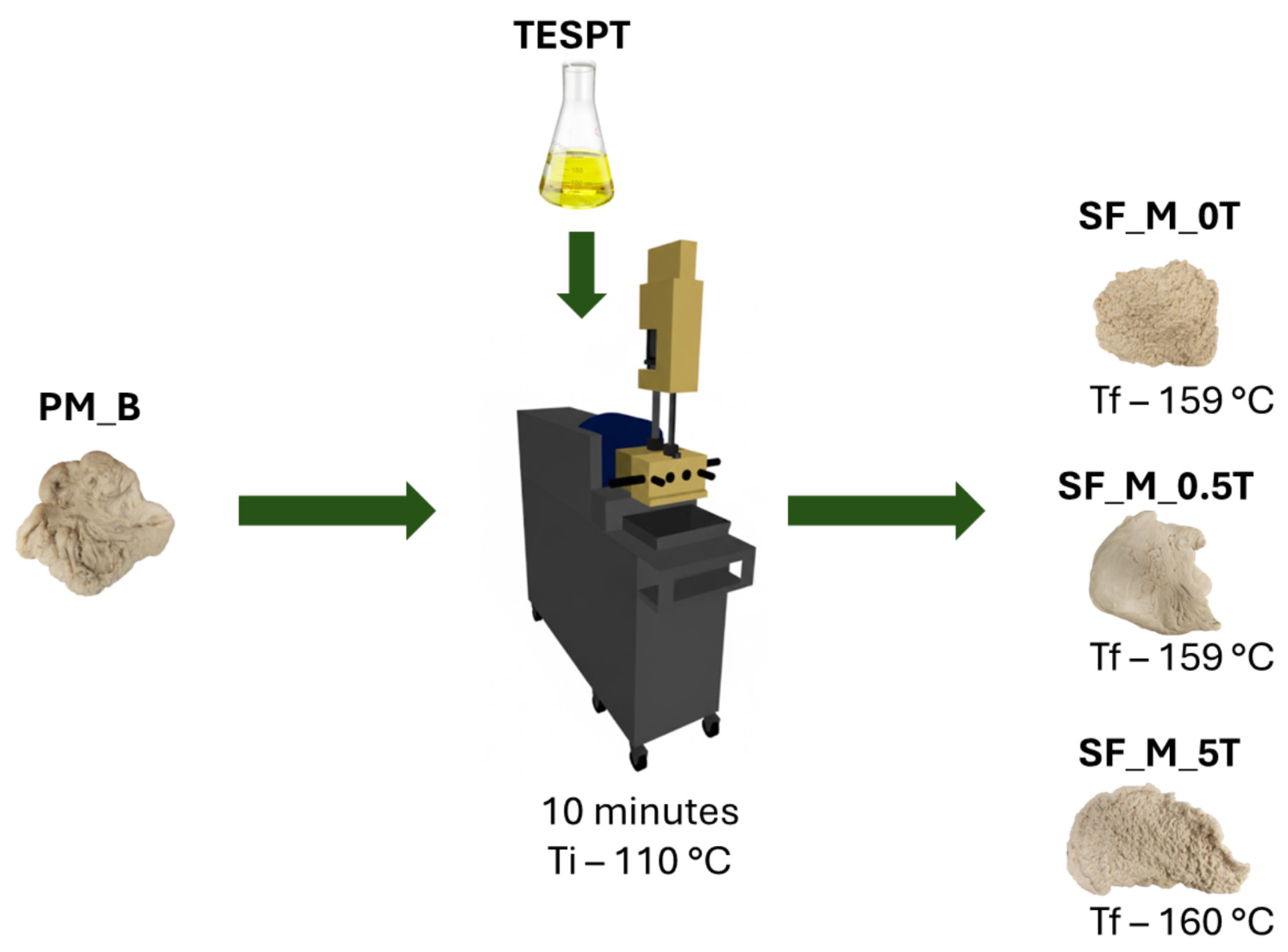

2.2.2. Part 2—Addition of TESPT to Kaolin/NR Mixtures

2.2.3. Preparation of Kaolin/NR Compounds

2.2.4. Characterization of the Physical Properties of the Kaolin

2.2.5. Rheological, Morphological, and Vulcanization Characterization

2.2.6. Mechanical Properties

3. Results

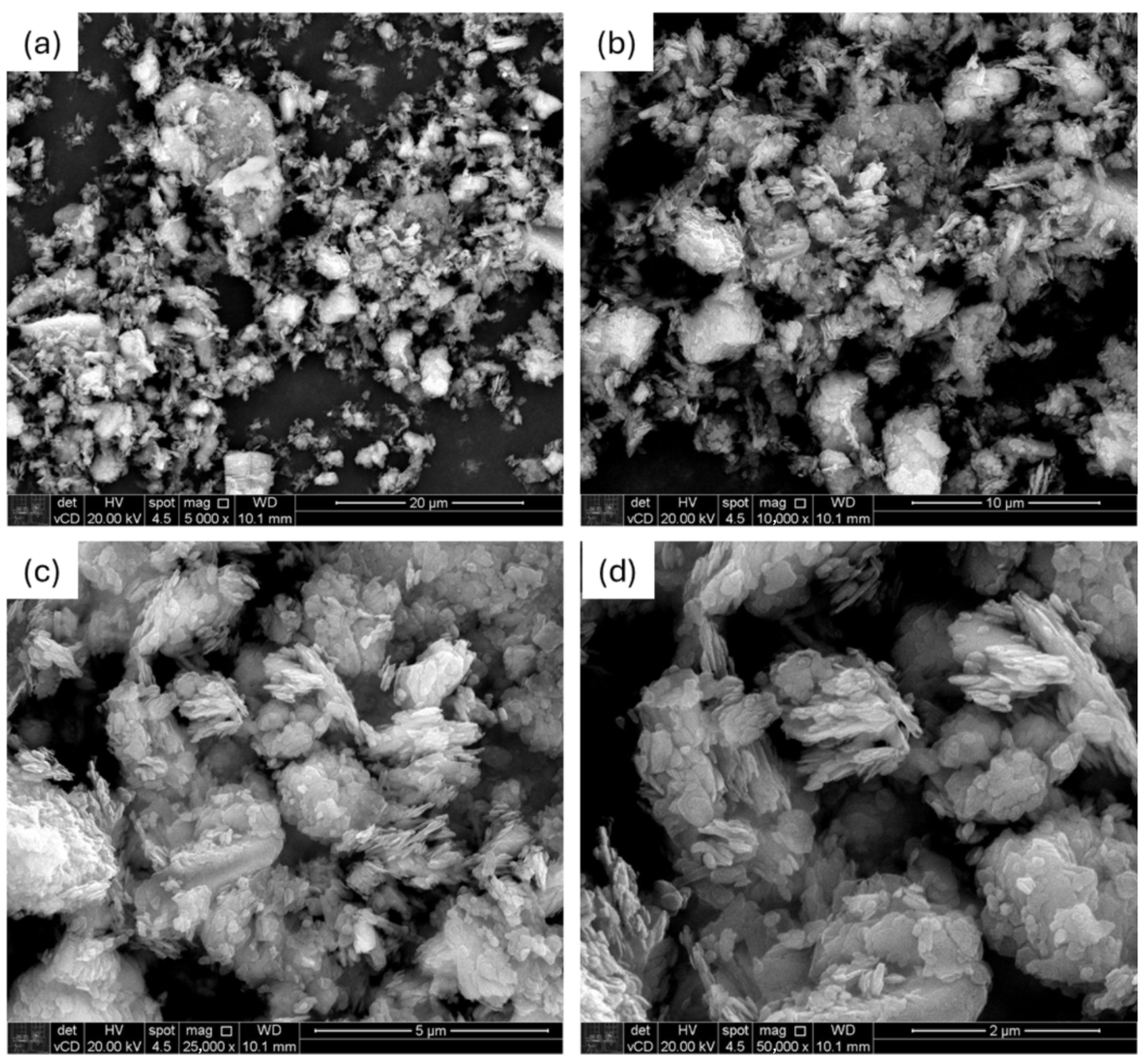

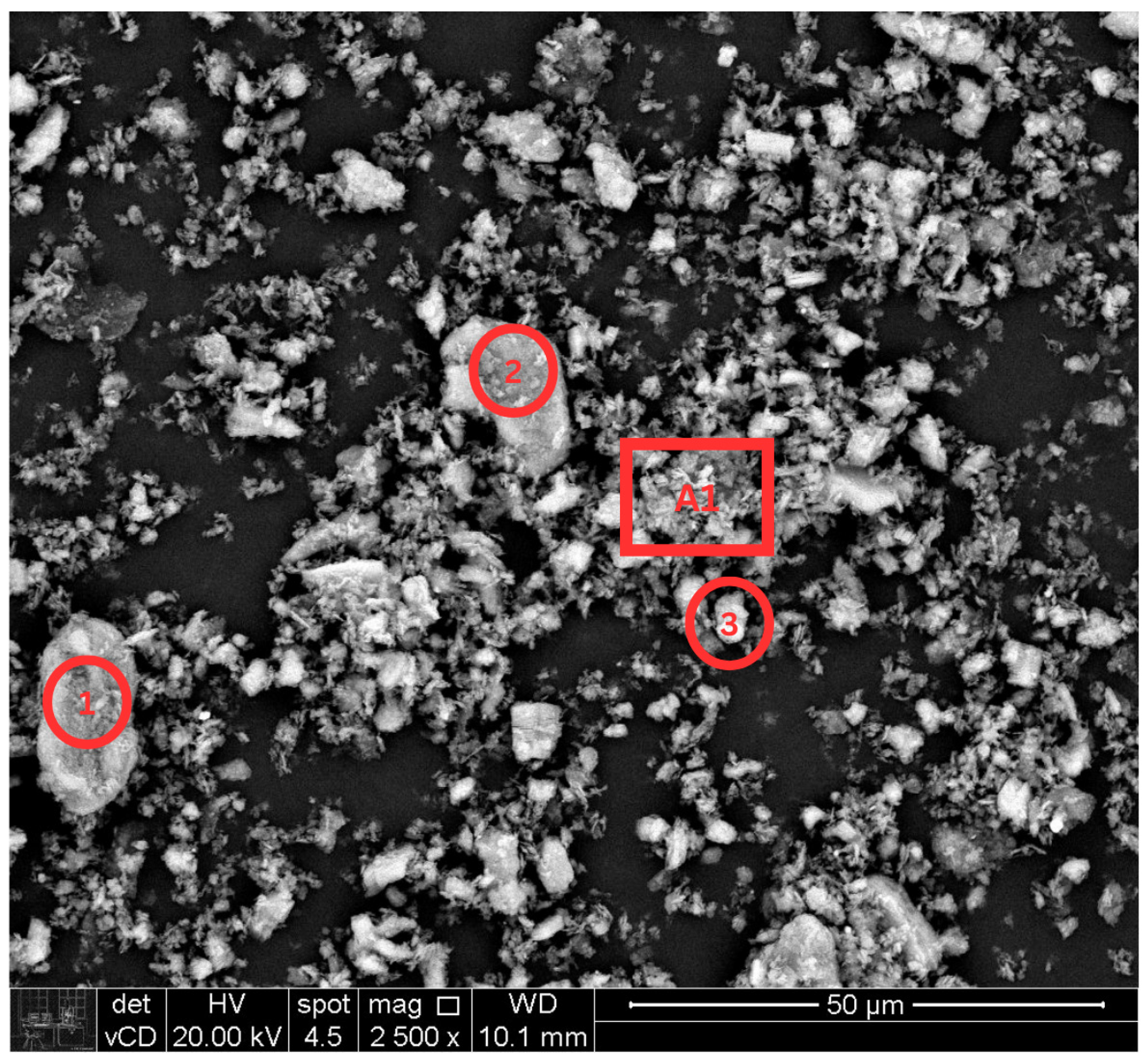

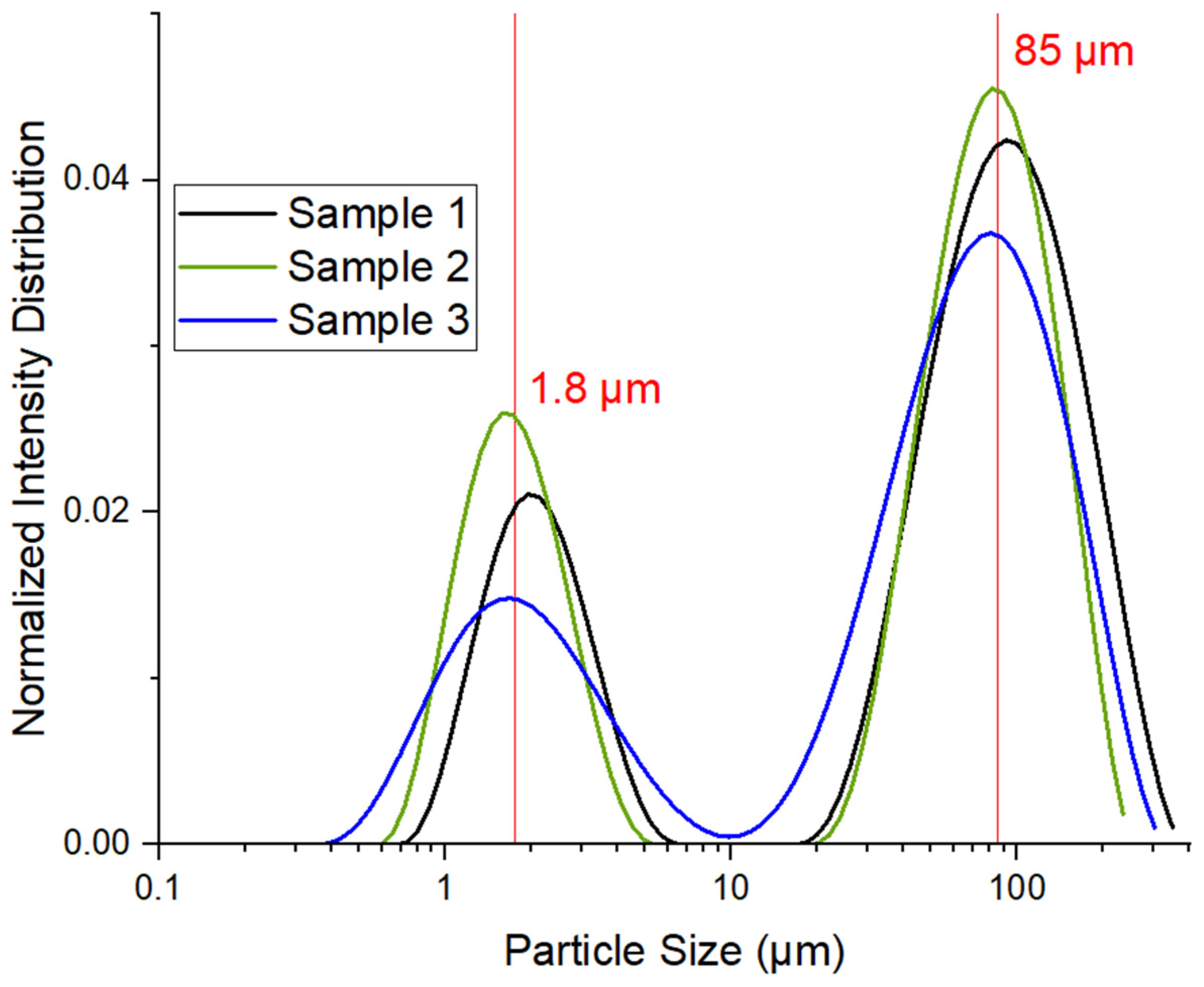

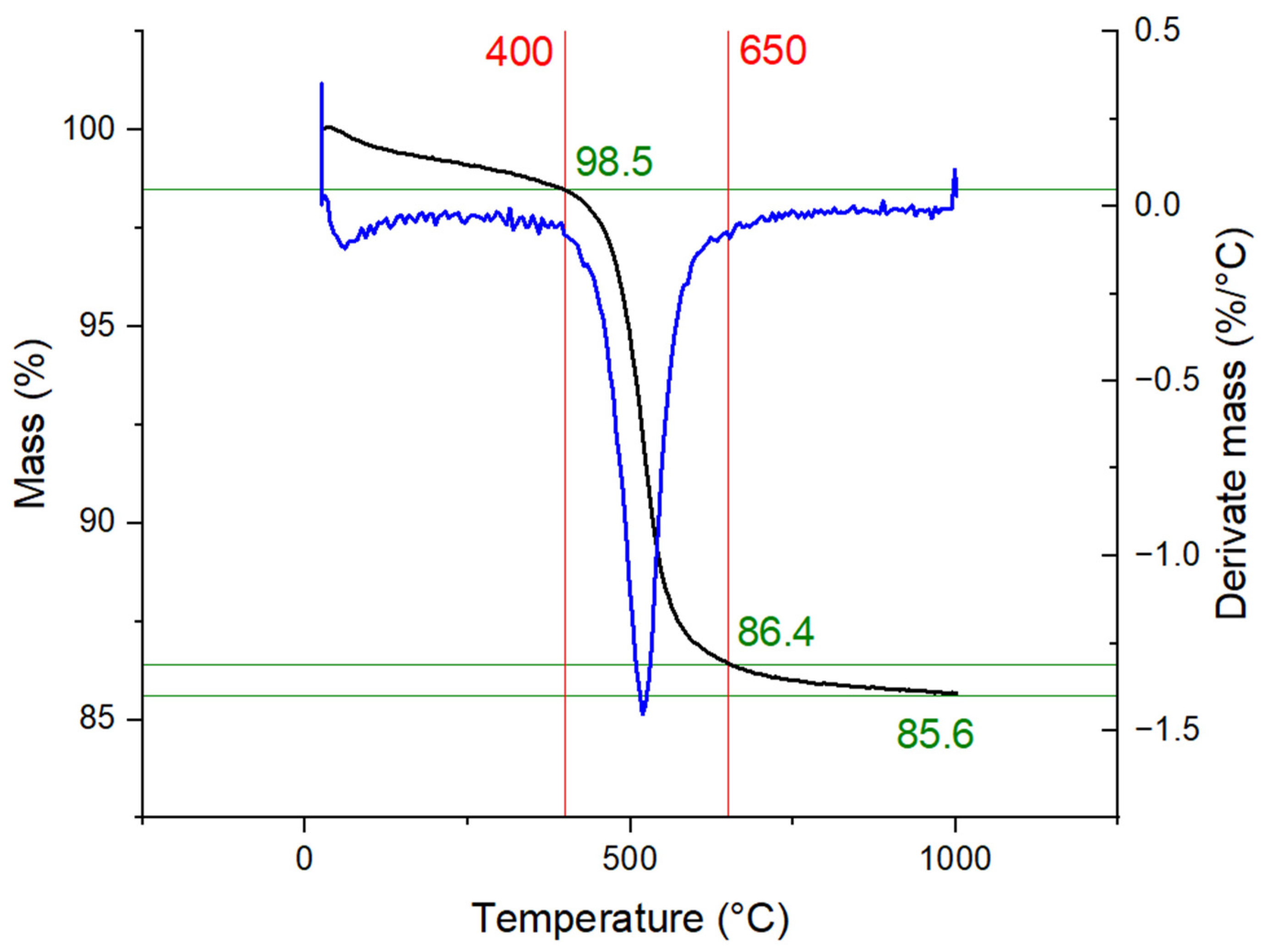

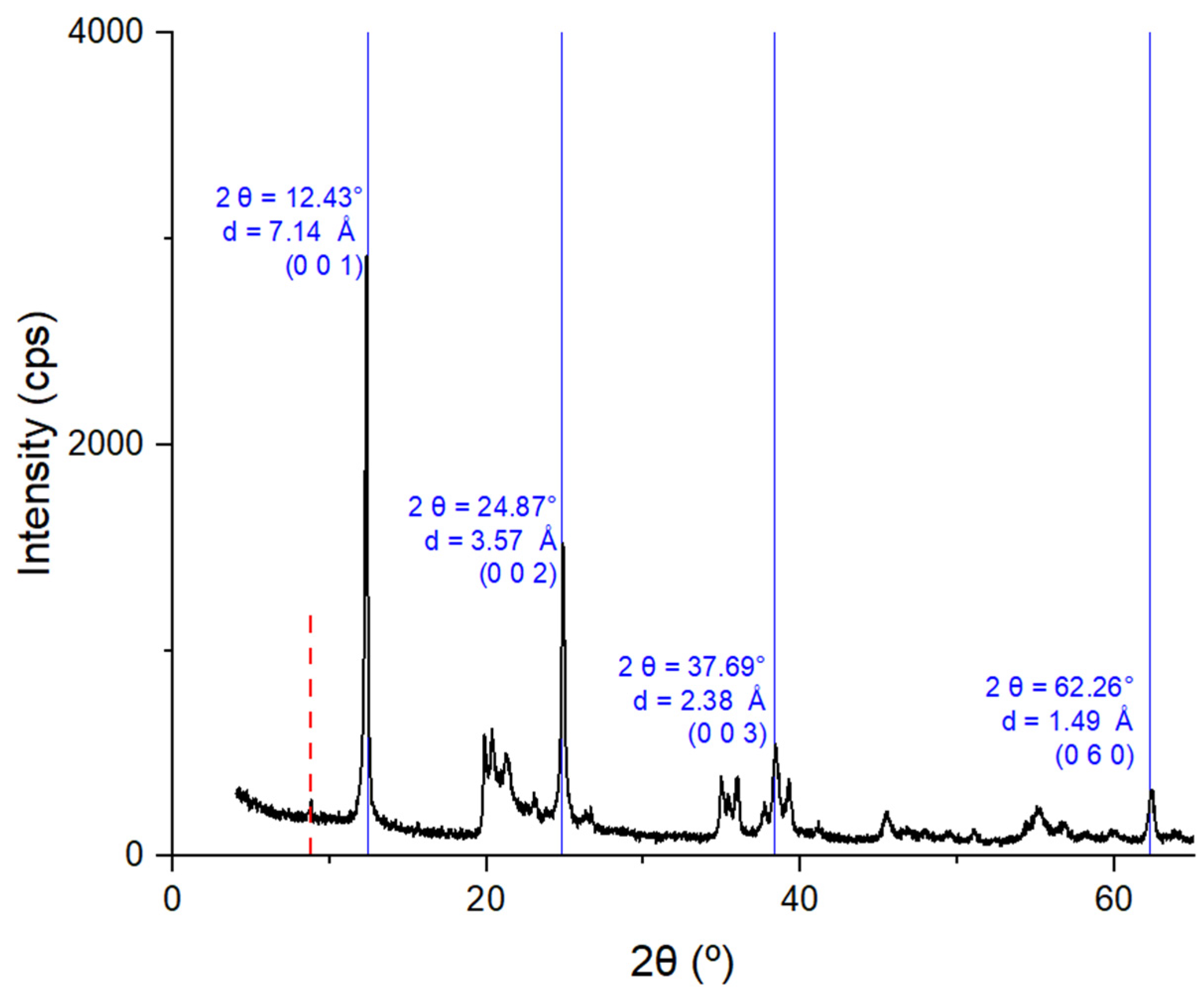

3.1. Characterization of Kaolin

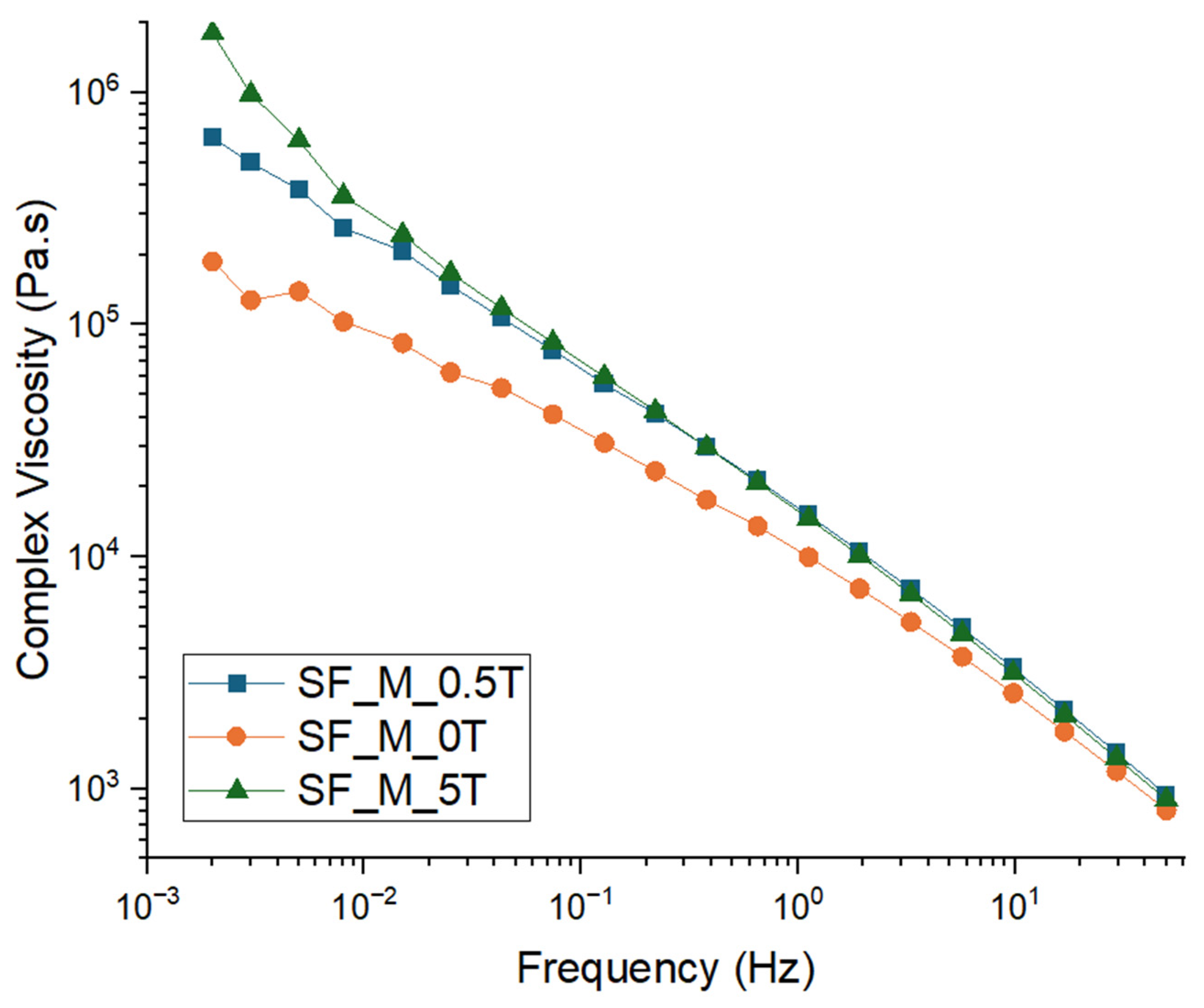

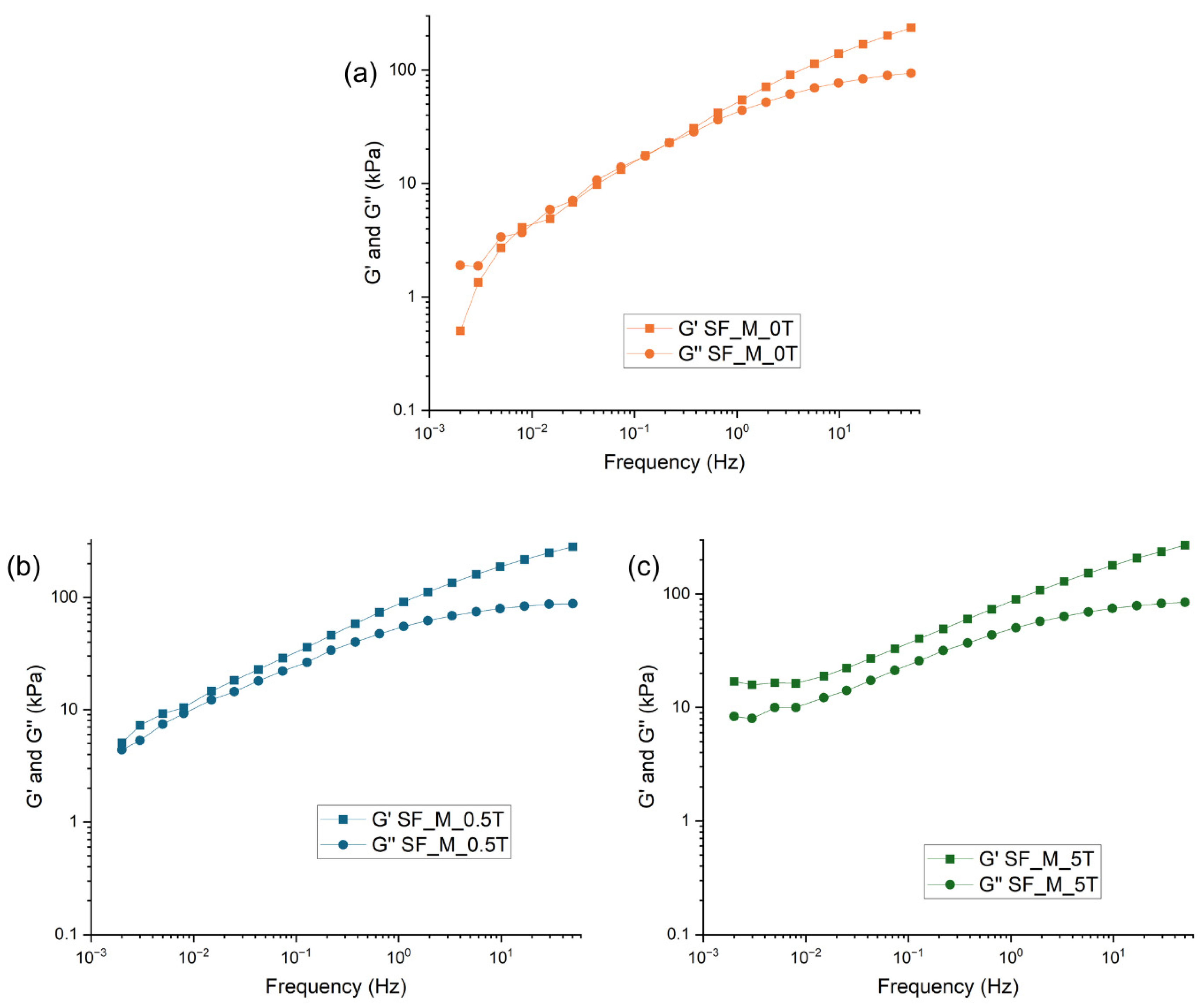

3.2. Characterization of Kaolin/NR Semifinished Mixtures

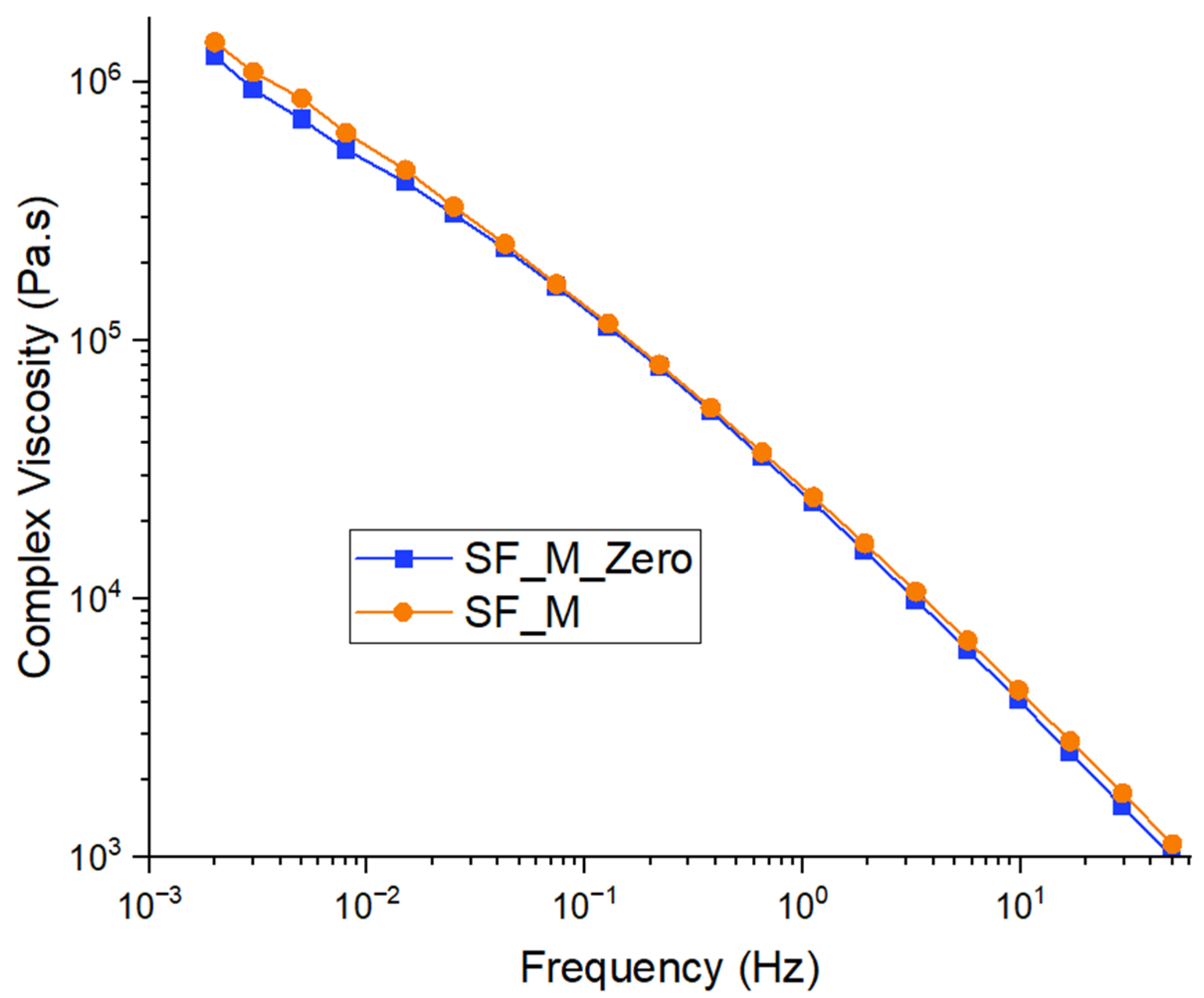

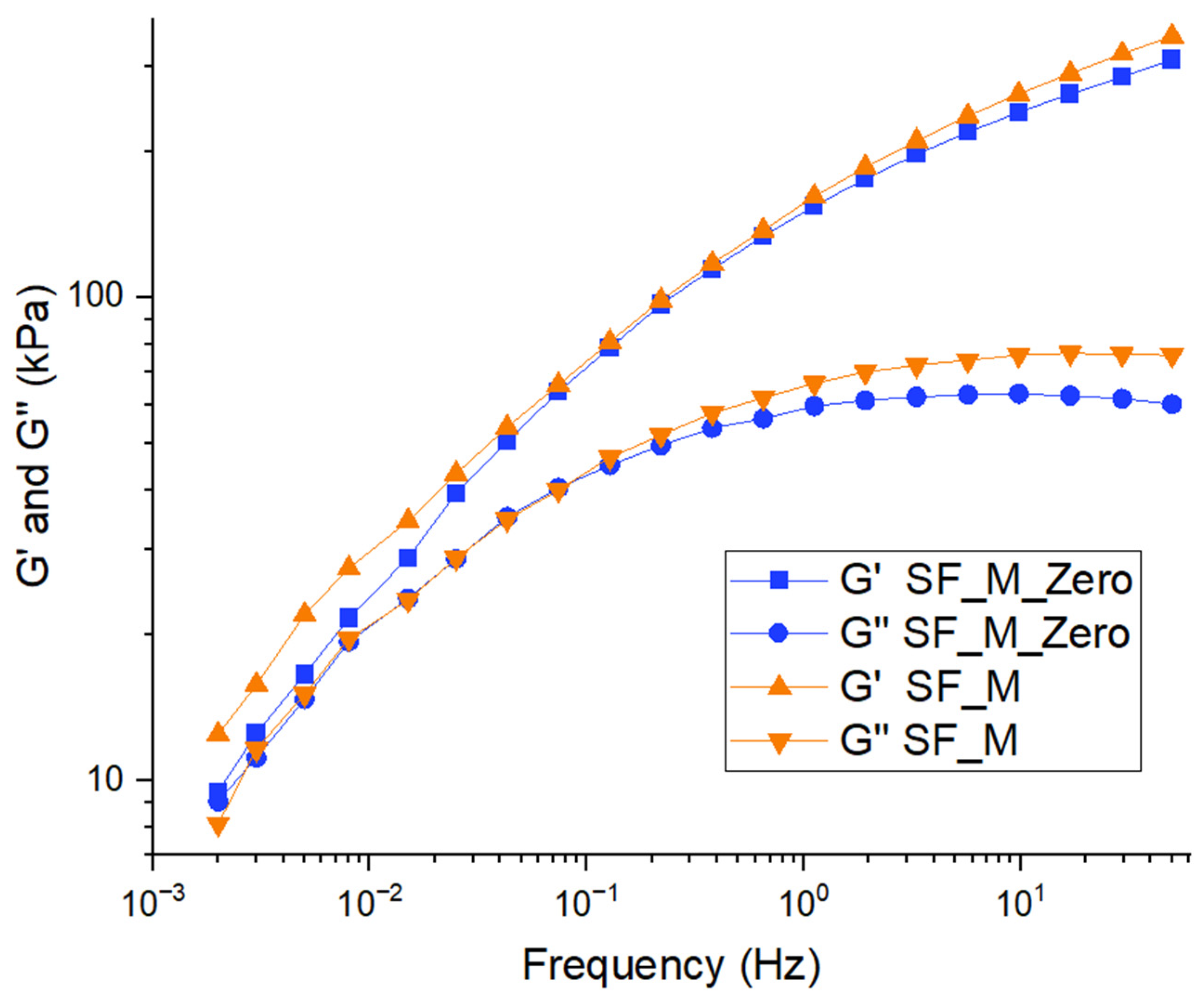

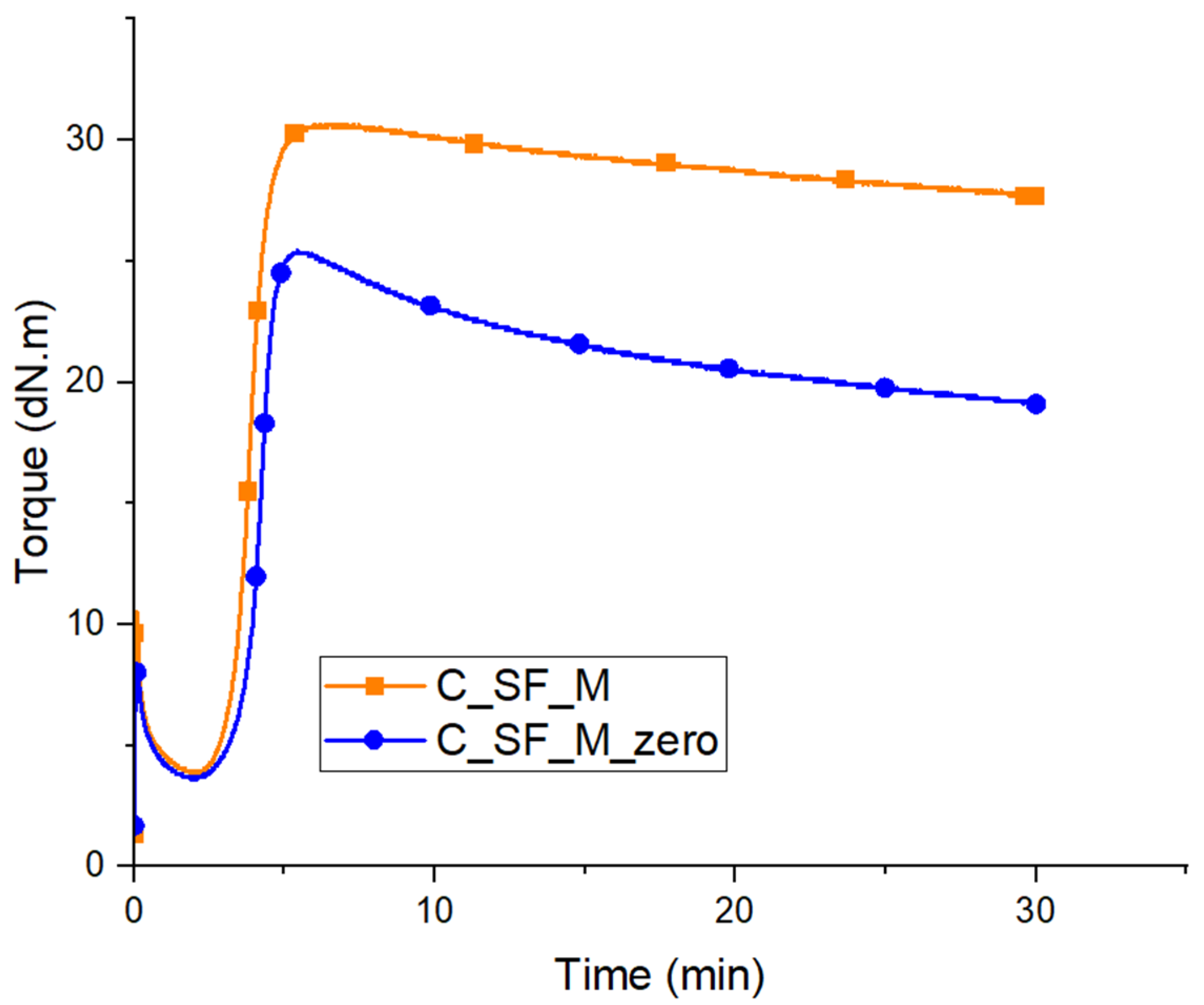

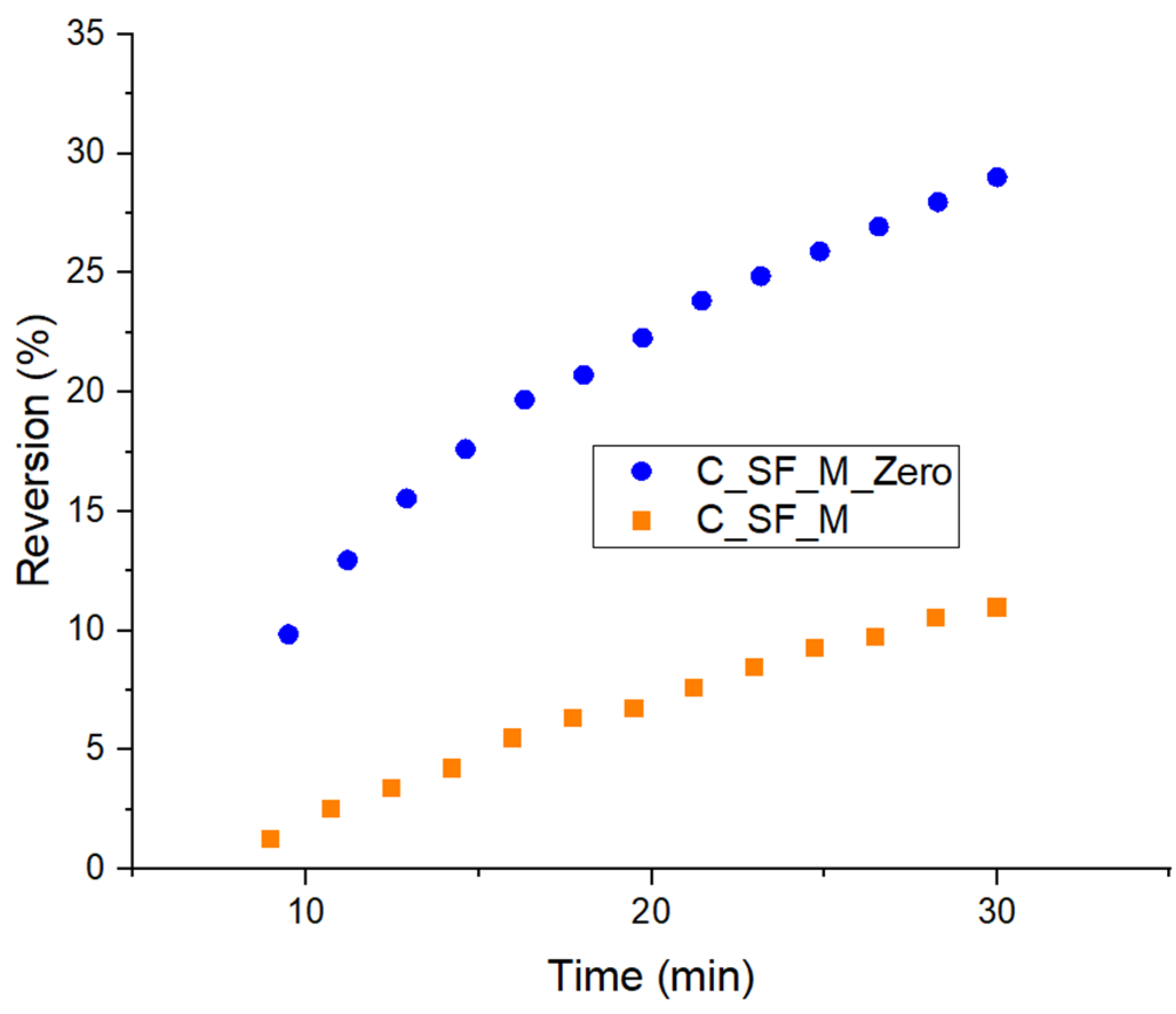

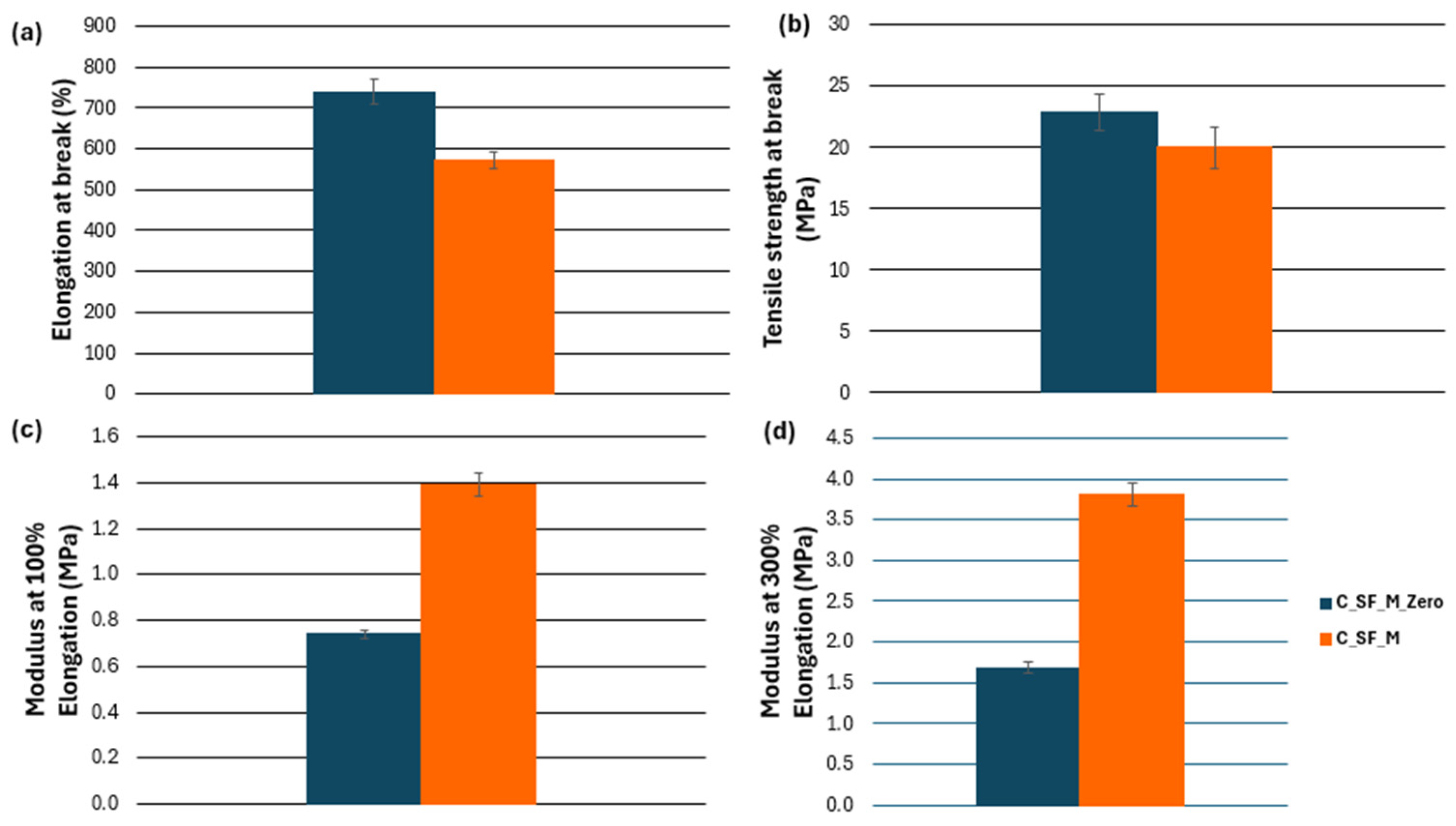

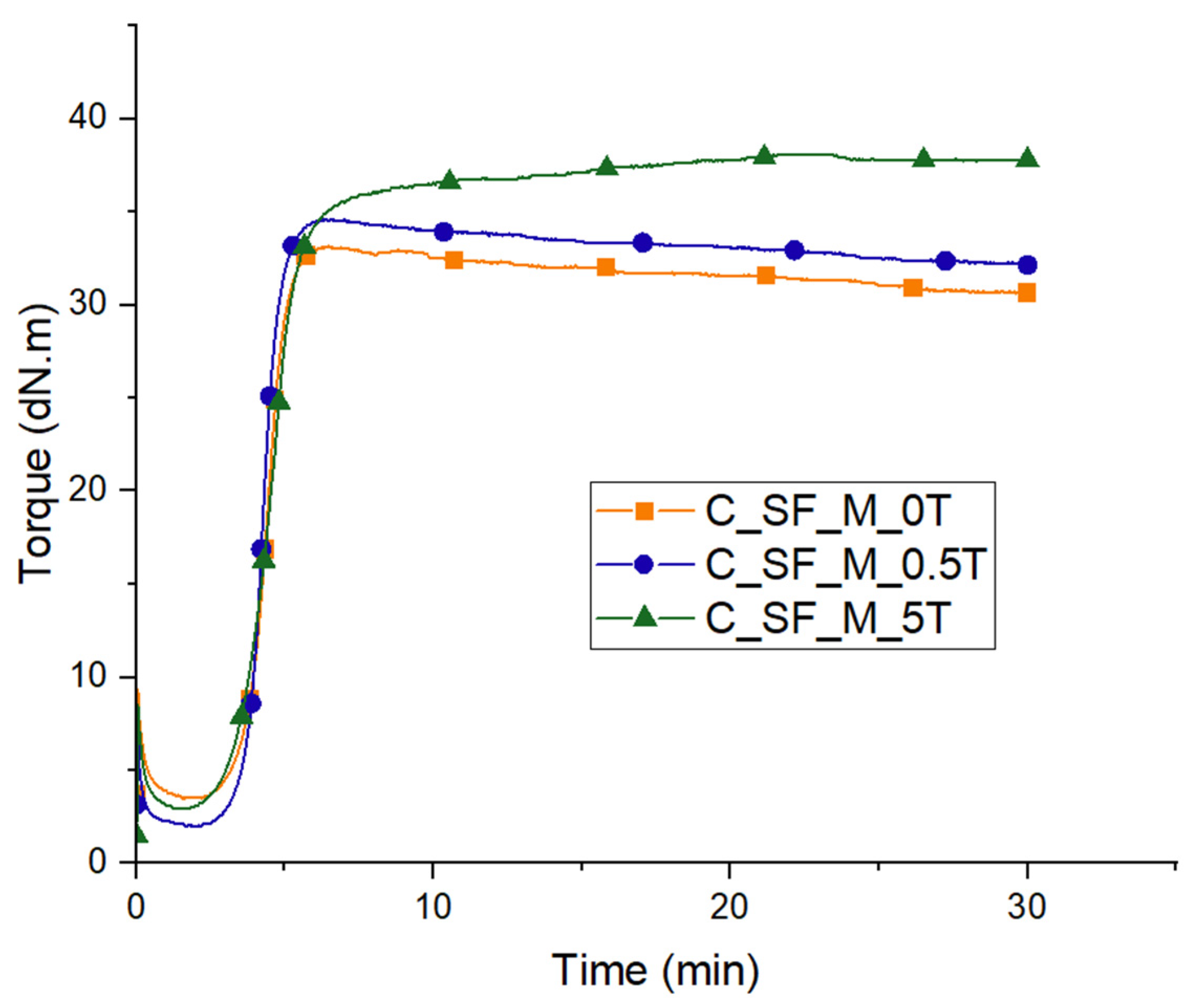

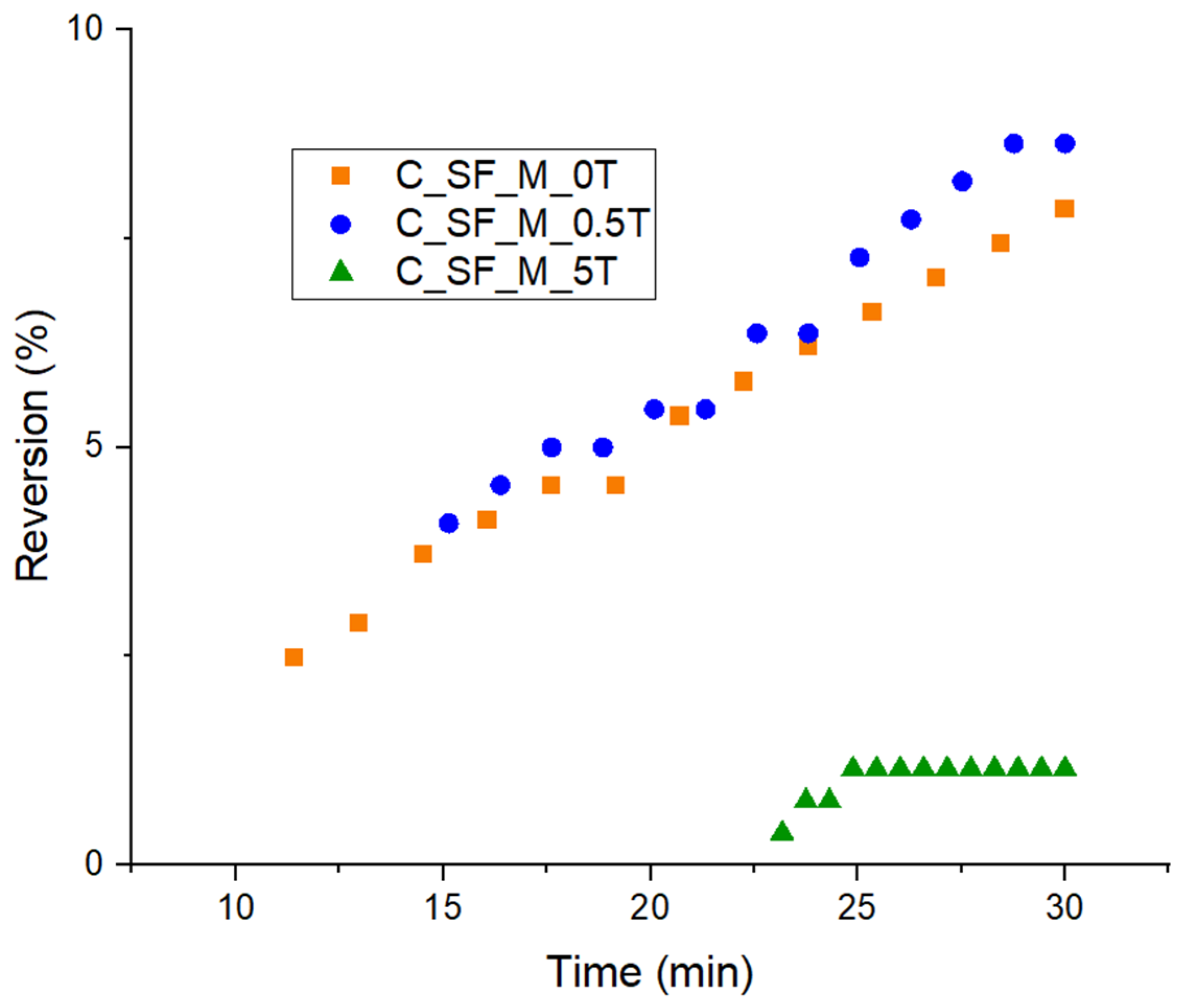

3.3. Characterization of Kaolin/NR Semifinished Mixtures with and Without TESPT

4. Discussion

4.1. Kaolin Characterization

4.2. Discussion Part 1: Kaolin/NR Semifinished Mixtures

4.3. Discussion Part 2: Kaolin/NR Semifinished Mixtures with and Without TESPT

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BET | Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller |

| CRI | Cure Rate Index |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DTA | Differential Thermal Analysis |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy |

| FEG-SEM | Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope |

| JCPDS | Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards |

| DSST | Dynamic Strain Sweep Test |

| DTST | Dynamic Time Sweep Test |

| LVER | Linear Viscoelastic Regime |

| MBTS | Dibenzothiazolyl Disulfide |

| NR | Natural Rubber |

| ODR | Oscillating Disk Rheometer |

| Phr | Per Hundred Rubber |

| SAOS | Small Amplitude Oscillatory Shear |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TBzTD | Tetrabenzylthiuram Disulfide |

| TESPT | Bis[3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl] Tetrasulfide |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| ZnO | Zinc Oxide |

References

- Funt, J.F. Mixing of Rubber; Smithers Rapra Technology Limited: Shawbury, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84735-151-7. [Google Scholar]

- García-Tárrago, M.J.; Calaf-Chica, J.; Gómez-Gil, F.J. High-frequency mechanical impedance of rubber mounts: Experimental characterization and resonance mechanisms. Eur. J. Mech. A/Solids 2025, 113, 105677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F.M.; Silva, A.L.E.; May, J.; da Silva Szarblewski, M.; Flemming, L.; Assmann, E.E.; Moraes, J.A.R.; Machado, Ê.L. Environmental impacts associated with the life cycle of natural rubbers: A review and scientometric analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 224, 120350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, X.; Pan, M.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L. Reduced rolling resistance in green tires with optimized grafted-modifier natural rubber. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 205, 109319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whba, R.; Su’ait, M.S.; Whba, F.; Sahinbay, S.; Altin, S.; Ahmad, A. Intrinsic challenges and strategic approaches for enhancing the potential of natural rubber and its derivatives: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, D.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.; Yang, Y.; Liao, Y. Enhancing weatherability and mechanical properties of tung oil wood finishes through natural rubber modification via the Diels–Alder reaction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Senoo, K.; Toki, S.; Kohjiya, S. Structural development of natural rubber during uniaxial stretching by in situ wide-angle X-ray diffraction using synchrotron radiation. Polymer 2002, 43, 2117–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, F.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Yuan, Z.; Liao, S. Fluorinated natural rubber with enhanced strength and excellent resistance to ozone, organic solvent, and acid and alkali via in situ reactive melt extrusion. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 228, 110916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chailad, W.; Tongsom, K.; Chaochanchaikul, K.; Sakulkhaemaruethai, C. Enhancing air retention in natural rubber: A path to improved performance. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 3841–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahruddin; Wiranata, A.; Helwani, Z.; Jahrizal; Firzal, Y. Characteristics of exterior emulsion paint using natural rubber latex binder. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 52, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.D. Natural Rubber Science and Technology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, E.H. Reinforcement of rubber by fillers. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1963, 36, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H. Properties of vulcanized rubber nanocomposites filled with nanokaolin and precipitated silica. Appl. Clay Sci. 2008, 42, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Stephen, R. Rubber Nanocomposites: Preparation, Properties and Applications; Wiley: Singapore, 2010; ISBN 978-3131450715. [Google Scholar]

- Labruyère, C.; Gorrasi, G.; Monteverde, F.; Alexandre, M.; Dubois, P. Transport properties of organic vapours in silicone/clay nanocomposites. Polymer 2009, 50, 3626–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.R.; Robeson, L.M. Polymer nanotechnology: Nanocomposites. Polymer 2008, 49, 3187–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.C.; Huang, J.T. Surface modification of clays and clay–rubber composite. Appl. Clay Sci. 1999, 15, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, R.; Agusnar, H.; Alfian, Z.; Tamrin. Characterization of technical kaolin using XRF, SEM, XRD, FTIR and its potentials as industrial raw materials. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1116, 042010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konta, J. Clay and man: Clay raw materials in the service of man. Appl. Clay Sci. 1995, 10, 275–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, Y.; Gong, Z.; Diao, P.; Wang, C.; Bian, H. High-value application of kaolin by wet mixing method in low heat generation and high wear-resistant natural rubber composites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 261, 107574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Wang, D.; Stöckelhuber, K.W.; Jurk, R.; Fritzsche, J.; Klüppel, M.; Heinrich, G. Rubber–clay nanocomposites: Some recent results. In Rubber Nanocomposites; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 85–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rattanasom, N.; Saowapark, T.; Deeprasertkul, C. Reinforcement of natural rubber with silica/carbon black hybrid filler. Polym. Test. 2007, 26, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.S. Efeito da incorporação de sílica tratada com aminosilano nos nanocompósitos PMMA/SAN/sílica. In Coletânea de Atividades em Pesquisa Científica e Inovação Tecnológica; Atena Editora: Ponta Grossa, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sattayanurak, S.; Noordermeer, J.W.M.; Sahakaro, K.; Kaewsakul, W.; Dierkes, W.K.; Blume, A. Silica-reinforced natural rubber: Synergistic effects by addition of small amounts of secondary fillers to silica-reinforced natural rubber tire tread compounds. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5891051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.; Jin, S. Preparation of hydrophobic modified silica with Si69 and its reinforcing mechanical properties in natural rubber. Materials 2024, 17, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantachum, P.; Khumpaitool, B.; Utara, S. Effect of silane coupling agent and cellulose nanocrystals loading on the properties of acrylonitrile butadiene rubber/natural rubber nanocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 195, 116407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaptong, P.; Sae-Oui, P.; Sirisinha, C. Effects of silanization temperature and silica type on properties of silica-filled solution styrene butadiene rubber (SSBR) for passenger car tire tread compounds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 43342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansarifar, A. Mineral kaolin—A highly versatile filler for rubber. J. Miner. Mater. Sci. 2022, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimmaiah, S.R.; Siddaramaiah. Investigation of carbon black and metakaolin cofiller content on mechanical and thermal behaviors of natural rubber compounds. J. Elastomers Plast. 2013, 45, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Kumar, V.; Debnath, S.C.; Jeong, T.; Park, S.S. Naturally abundant silica–kaolinite mixed minerals as an outstanding reinforcing filler for the advancement of natural rubber composites. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Zhou, D.; Chen, Q.; Xin, Z. Effect of different silane coupling agents in situ modified sepiolite on the structure and properties of natural rubber composites prepared by latex compounding method. Polymers 2023, 15, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Sun, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effect of nitrile rubber on properties of silica-filled natural rubber compounds. Polym. Test. 2005, 24, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntako, R. The rubber damper reinforced by modified silica fume (mSF) as an alternative reinforcing filler in rubber industry. J. Polym. Res. 2017, 24, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierkes, W.K. Economic Mixing of Silica–Rubber Compounds: Interaction Between the Chemistry of the Silica–Silane Reaction and the Physics of Mixing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D4820-99; Standard Test Methods for Carbon Black—Surface Area by Multipoint B.E.T. Nitrogen Adsorption. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1999.

- ASTM D2084-19; Standard Test Method for Rubber Property—Vulcanization Using Oscillating Disk Cure Meter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Boonkerd, K.; Deeprasertkul, C.; Boonsomwong, K. Effect of Sulfur to Accelerator Ratio on Crosslink Structure, Reversion, and Strength in Natural Rubber. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2016, 89, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D412-16; Standard Test Methods for Vulcanized Rubber and Thermoplastic Elastomers—Tension. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Yang, Y.; Jaber, M.; Michot, L.J.; Rigaud, B.; Walter, P.; Laporte, L.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Q. Analysis of the Microstructure and Morphology of Disordered Kaolinite Based on the Particle Size Distribution. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 232, 106801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Li, Q.; Fang, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Modified Kaolin by a Mechanochemical Method. Materials 2023, 16, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergaya, F.; Theng, B.K.G.; Lagaly, G. (Eds.) Handbook of Clay Science, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 978-0080457635. [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte, I.A.P.; Mocciaro, A.; Rendtorff, N.M.; Richard, D. Dehydroxylation of kaolinite: Evaluation of activation energy by thermogravimetric analysis and density functional theory insights. Minerals 2025, 15, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgabi, D.P.; Ambushe, A.A. Characterization of South African bentonite and kaolin clays. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konan, K.L.; Peyratout, C.; Smith, A.; Bonnet, J.P.; Rossignol, S.; Oyetola, S. Comparison of surface properties between kaolin and metakaolin in concentrated lime solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 339, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Tantawy, M.A. Characterization and application of kaolinite clay as solid-phase extractor for removal of copper ions from environmental water samples. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rouabhia, F.; Nemamcha, A.; Moumeni, H. Elaboration and characterization of mullite–anorthite–albite porous ceramics prepared from Algerian kaolin. Cerâmica 2018, 64, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.L.; Nascimento, R.M.; Martinelli, A.E.; Hotza, D.; Melo, D.M.A.; Melo, M.A.F. Optimization of a methodology for rational mineralogical analysis of clay minerals. Cerâmica 2005, 51, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanasom, N.; Suchiva, K. Rheological and processing properties of purified natural rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 98, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.A. Effect of Raw, Bleached, and Nanocellulose Jute Fiber on the Rheological, Mechanical, and Vulcanization Properties of Natural Rubber. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, P.H.; Joseph, R. Nanokaolin clay as reinforcing filler in nitrile rubber. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2012, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, H.H. Applied Clay Mineralogy: Occurrences, Processing and Application of Kaolins, Bentonite, Palygorskite–Sepiolite, and Common Clays; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, R.F.; Althoff, A.C. Surface acidity in kaolinites. Clays Clay Miner. 1967, 15, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coran, A.Y. Vulcanization. Part VII. Kinetics of sulfur vulcanization of natural rubber in the presence of delayed-action accelerators. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1965, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.; Salmiah, I. Palm oil fatty acid as an activator in carbon black-filled natural rubber compounds: Effect of epoxidation. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 1999, 43, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, L.E.; Adebowale, K.O.; Menon, A.R.R. Mechanical properties of organomodified kaolin natural rubber vulcanizates. Appl. Clay Sci. 2009, 46, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbebor, O.J.; Okieimen, F.E.; Ogbeifun, D.E.; Okwu, U.N. Organomodified kaolin as filler for natural rubber. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2015, 21, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, P. Characterization of kaolinite/styrene–butadiene rubber composites: Mechanical properties and thermal stability. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 124–125, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Mechanical and thermal properties of kaolin/natural rubber nanocomposites prepared by the conventional two-roll mill method. In Proceedings of the Applied Mechanics and Materials; Trans Tech Publications: Zurich, Switzerland, 2012; Volume 164, pp. 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xiang, J.; Frost, R.L. Influence of kaolinite particle size on cross-link density, microstructure, and mechanical properties of latex-blended styrene–butadiene rubber composites. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2015, 57, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansarifar, A.; Sheikh, S.H. Reinforcement with kaolin. In Mineral Fillers in Polymer Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 13, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carreau, P.J.; Vergnes, B. Rheological characterization of fiber suspensions and nanocomposites. In Rheology of Non-Spherical Particle Suspensions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 19–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J.; Wang, X. Rheological responses of particle-filled polymer solutions: The transition to linear–nonlinear dichotomy. J. Rheol. 2021, 65, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippone, G.; de Luna, M.S. A unifying approach for the linear viscoelasticity of polymer nanocomposites. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 8853–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.S.; Kim, I.S.; Woo, C.S. Influence of TESPT content on crosslink types and rheological behaviors of natural rubber compounds reinforced with silica. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 106, 2753–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.C.; Datta, R.N.; Noordermeer, J.W.M. Understanding the chemistry of the rubber/silane reaction for silica reinforcement using model olefins. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2003, 76, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakun, A.; Kemppainen, N.; Sarlin, E. Secondary network formation in epoxidized natural rubber with alternative curatives. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 36326–36340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhawan, R. Effects of Bis(3-triethoxysilylpropyl) Tetrasulfane (TESPT) on Properties of Silica-Filled Natural Rubber Compounds. Ph.D. Thesis, Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brinke, J.W.T.; Van Swaaij, P.J.; Reuvekamp, L.A.E.M.; Noordermeer, J.W.M. The influence of silane sulphur rank on processing of a silica-reinforced tyre tread compound. Kautsch. Gummi Kunstst. 2002, 55, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-J.; VanderKooi, J. Rheological effect of zinc surfactant on the TESPT–silica mixture in NR and S-SBR compounds. Int. Polym. Process. 2002, 17, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañosa, J.; Alvarez-Coscojuela, A.; Maldonado-Alameda, A.; Chimenos, J.M. A lab-scale evaluation of parameters influencing the mechanical activation of kaolin using the design of experiments. Materials 2024, 17, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkawi, S.S.; Dierkes, W.K.; Noordermeer, J.W.M. Morphology of silica-reinforced natural rubber: The effect of silane coupling agent. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2015, 88, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohi, H.; Horiuchi, S. Locating a silane coupling agent in silica-filled rubber composites by EFTEM. Langmuir 2007, 23, 12344–12349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Quantity (phr) |

|---|---|

| Semifinished mixture | 100 (NR) and 20 (Kaolin) |

| ZnO | 5 |

| Stearic acid | 2 |

| MBTS | 1 |

| TBzTD | 0.5 |

| Sulfur | 2 |

| Spot | Element | Composition (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Al2O3 | 44.6 |

| SiO2 | 55.4 | |

| 1 | Al2O3 | 47.6 |

| SiO2 | 52.4 | |

| 2 | Al2O3 | 46.8 |

| SiO2 | 53.2 | |

| 3 | Al2O3 | 45.3 |

| SiO2 | 54.7 | |

| Average | Al2O3 | 46.1 |

| SiO2 | 53.9 |

| C_SF_M | C_SF_M_Zero | |

|---|---|---|

| MH (dN.m) | 30.6 | 25.4 |

| ML (dN.m) | 3.8 | 3.6 |

| t90 (min) | 4.5 | 4.7 |

| ts1 (min) | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| ΔM | 26.8 | 21.8 |

| CRI | 58.8 | 58.8 |

| Mean (C_SF_M_Zero) | Mean (SF_M) | F-Value | F-Critical | Significance (p < 0.05) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elongation at break (%) | 739.1 | 573.9 | 209.3 | 4.4 | Significant |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 22.8 | 20.0 | 15.5 | 4.4 | Significant |

| Modulus at 100% (MPa) | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1169.7 | 4.4 | Significant |

| Modulus at 300% (MPa) | 1.7 | 3.8 | 1757.1 | 4.4 | Significant |

| C_SF_M_0T | C_SF_M_0.5T | C_SF_M_5T | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MH (dN.m) | 34.7 | 33.2 | 38.2 |

| ML (dN.m) | 2.0 | 3.5 | 3.0 |

| t90 (min) | 5.0 | 5.1 | 6.2 |

| ts1 (min) | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

| ΔM | 32.7 | 29.7 | 35.2 |

| CRI | 52.6 | 47.6 | 28.6 |

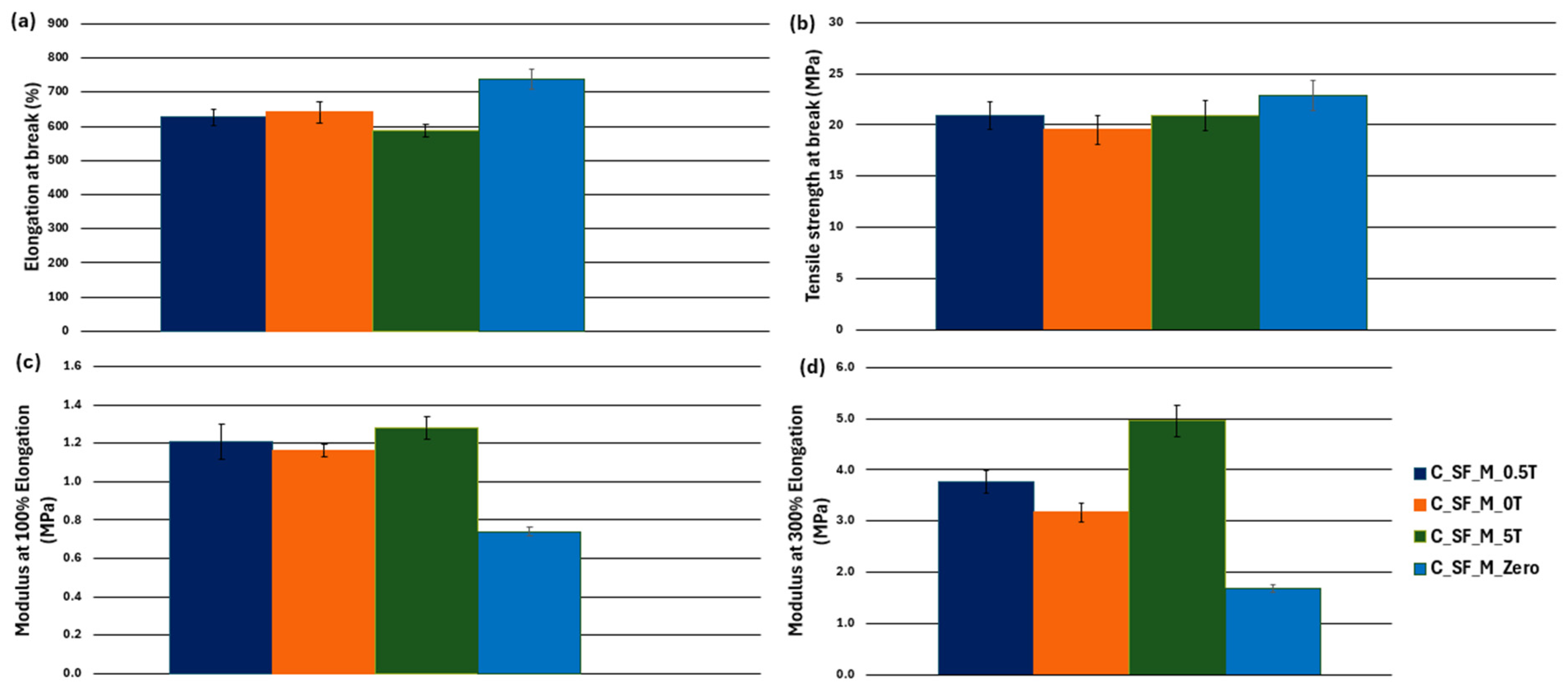

| Property | Mean (C_SF_M_0T) | Mean (C_SF_M_0.5T) | Mean (C_SF_M_5T) | F-Value | F-Critical | Significance (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 19.5 | 20.9 | 20.9 | 3.2 | 3.3 | Not significant |

| Elongation at break (%) | 640.7 | 626.1 | 588.2 | 11.7 | 3.3 | Significant |

| Modulus at 100% (MPa) | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 8.2 | 3.3 | Significant |

| Modulus at 300% (MPa) | 3.2 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 139.9 | 3.3 | Significant |

| Properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Comparison | Elongation (%) | Modulus at 100% (MPa) | Modulus at 300% (MPa) | ||

| C_SF__M_0T | vs. | C_SF_M_0.5T | Not significant | Not significant | Significant difference |

| C_SF_M_0T | vs. | C_SF_M_5T | Significant difference | Significant difference | Significant difference |

| C_SF_M_0.5T | vs. | C_SF_M_5T | Significant difference | Significant difference | Significant difference |

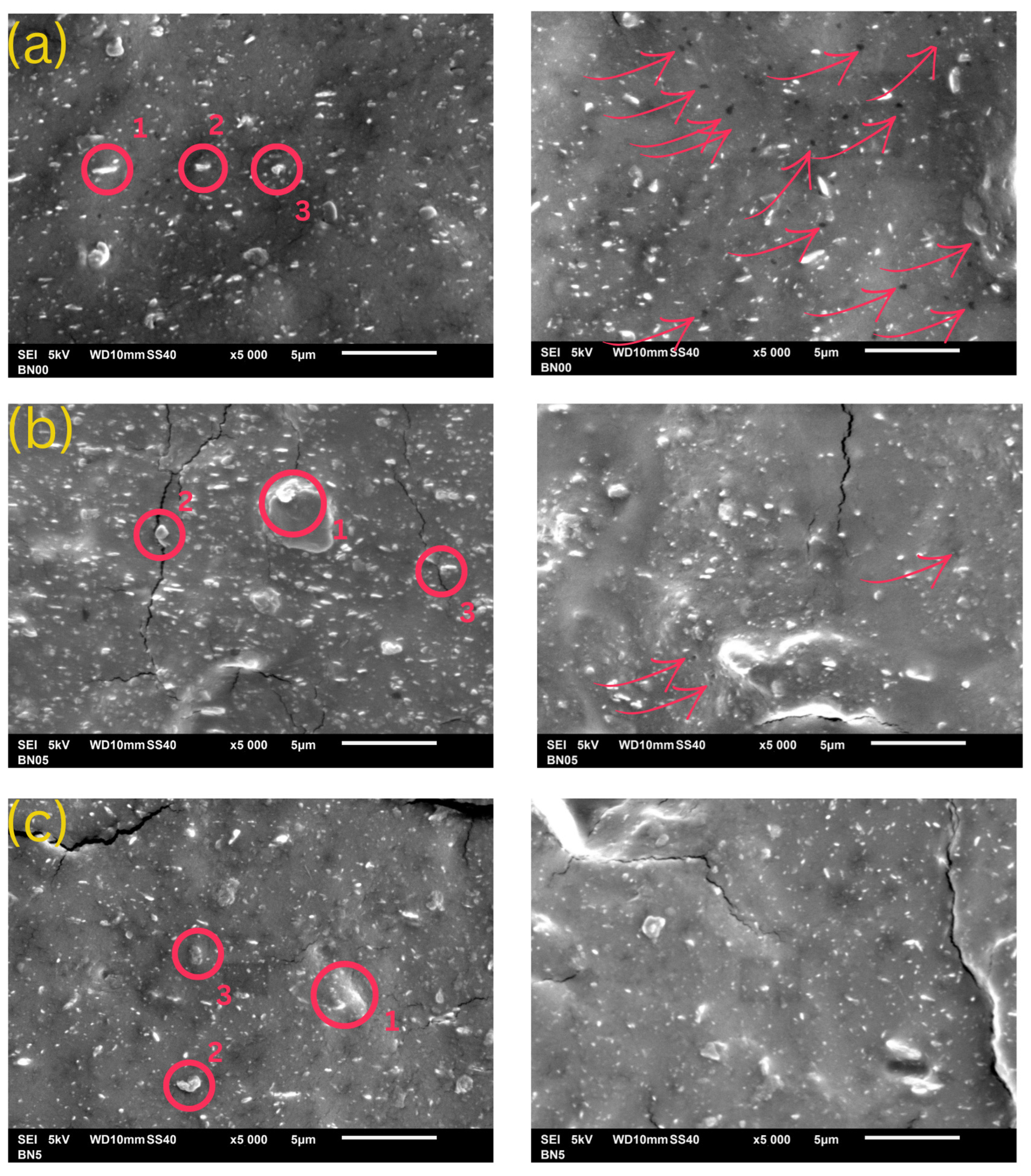

| Composition of Sample (a) | Composition of Sample (b) | Composition of Sample (c) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spot 2 | Spot 3 | Spot 4 | Spot 1 | Spot 2 | Spot 3 | Spot 1 | Spot 2 | Spot 3 | |

| Element | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) |

| C | 58.4 | 59.6 | 67.6 | 26.5 | 62.9 | 59.3 | 54.9 | 58.4 | 58.5 |

| Al2O3 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 8.5 | 29.7 | 21.4 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 10.5 | 12.3 |

| SiO2 | 19.3 | 19.1 | 11.4 | 42.7 | 8.0 | 20.1 | 21.9 | 15.8 | 18.1 |

| SO3 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 7.3 | - | 4.0 | 2.8 | 6.0 | 9.8 | 7.4 |

| ZnO | 4.0 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 3.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Camargo, M.C.; Gonzaga Neto, A.C.; Toffoli, S.M.; Valera, T.S. Using TESPT to Improve the Performance of Kaolin in NR Compounds. Minerals 2026, 16, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16020149

Camargo MC, Gonzaga Neto AC, Toffoli SM, Valera TS. Using TESPT to Improve the Performance of Kaolin in NR Compounds. Minerals. 2026; 16(2):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16020149

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamargo, Michael Cezar, Abel Cardoso Gonzaga Neto, Samuel Marcio Toffoli, and Ticiane Sanches Valera. 2026. "Using TESPT to Improve the Performance of Kaolin in NR Compounds" Minerals 16, no. 2: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16020149

APA StyleCamargo, M. C., Gonzaga Neto, A. C., Toffoli, S. M., & Valera, T. S. (2026). Using TESPT to Improve the Performance of Kaolin in NR Compounds. Minerals, 16(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16020149