White Marble Sourcing and Regional Workshop Dynamics in Roman Thrace: An Archaeometric Study of Votive Reliefs

Abstract

1. Introduction

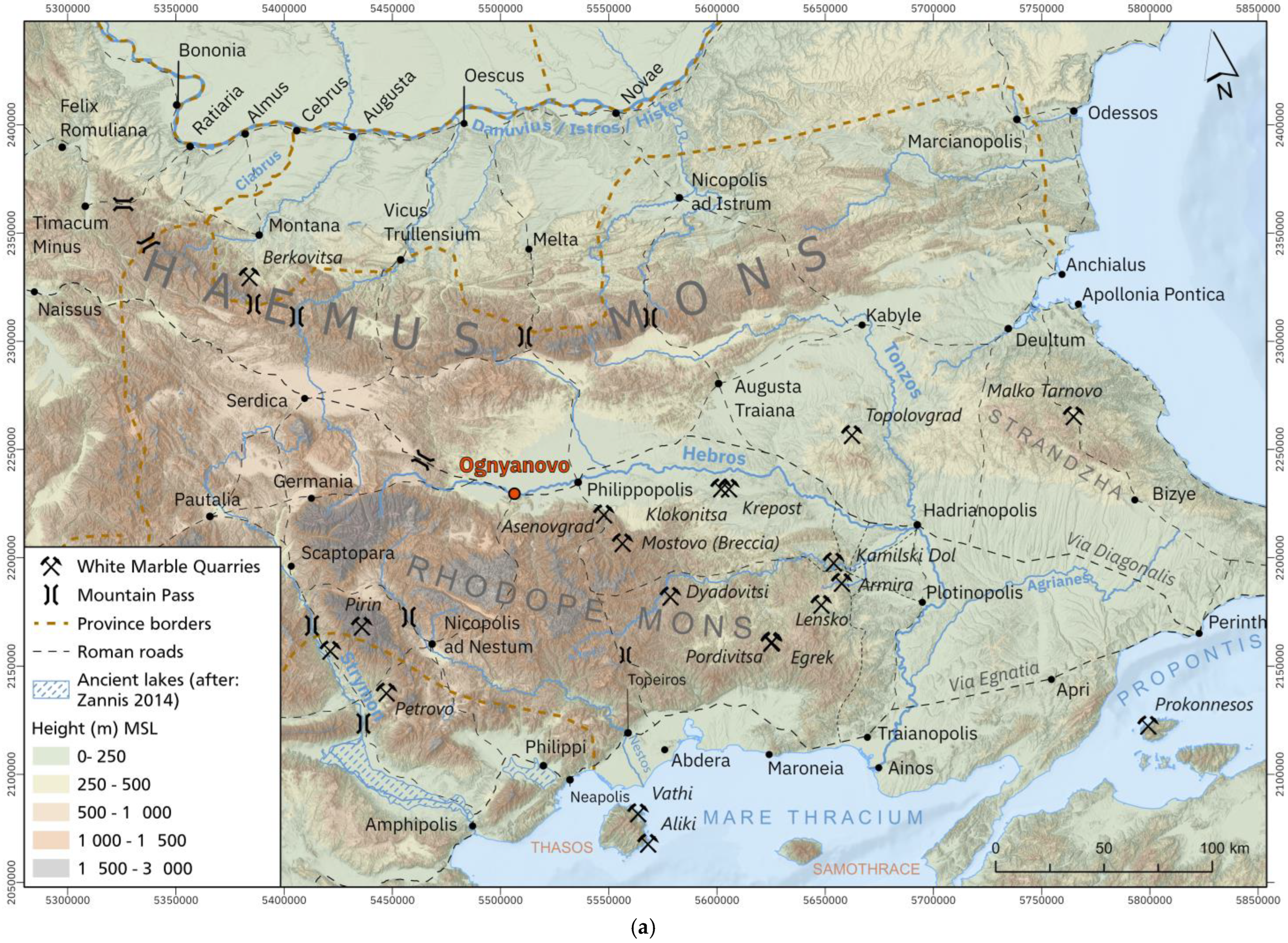

1.1. Geological Setting

- The lower level contains grey-to-grey-white-banded medium-grained marbles interbedded with gneisses and schists.

- The middle level comprises white-to-grey fine-to-medium-grained massive marbles containing graphite, mica, and quartz inclusions.

- The upper level consists of dolomitic marbles that gradually transition into purer calcitic marbles. The formation as a whole reaches thicknesses of up to 1600 m [13].

1.2. Remarks on the Sanctuaries

2. The Case Studies and the Sampled Artefacts

| Project Nr | Lab Nr | M. Nr * | Object | Material | Stone Description | Dating | Location | Find Spot | Details on Finding-Spot | Provenance Results | Photo | Bibliography |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWM0047 | 9243 | 1537 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; ultrafine-grained. | 2nd century AD | NAIM Museum | Philippopolis | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | IGBulg III,1 965 |

| Description: Relief image of Zeus and a Greek inscription. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0049 | 9244 | 1643 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; coarse-grained. | 2nd–3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Asenovgrad region | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [23] (Figure 444, p. LXXV) |

| Description: Relief image of the Thracian Horseman. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0102 | 9267 | 2906 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals. | 2nd–3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Panagyurishte Philippopolis | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | IGBulg III,1 1055 |

| Description: Relief images of Dionysos and Heracles in a chariot. Greek inscription engraved on the frame. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0104 | 9268 | 5993 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals; heteroblastic; zero translucency. | 2nd–3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Philippopolis, Philippopolis region | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [24] |

| Description: Relief images of Athena and Hermes. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0105 | 9269 | 3337 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; coarse-grained. | First half of the 3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Tatarevo, Philippopolis region | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | IGBulg II 768 |

| Description: Relief image of Zeus holding a horn of plenty and a patera over an altar. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0108 | 9264 | 3310 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-to-coarse-grained. | 2nd–3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Philippopolis, Philippopolis region | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | Note: Under the current investigation with the project FWF P 33.042 |

| Description: Representing a scene of a sacrifice. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0112 | 9265 | 1531 | Votive plate | Marble | White to beige colour; coarse-grained. | 2nd–3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Philippopolis, Philippopolis region | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [25] |

| Description: Relief images of Dionysus and Heracles on a chariot. Scene of wine production in the lower register. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0041 | 9241 | 1642 | Relief of Hercules | Marble | White-to-greyish colour; medium-to-coarse-grained. | 2nd–3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Asenovgrad region | n/a | SE Rhodope | n/a | n/a |

| Description: A votive plate decorated with a relief representing a scene of sacrifice. Heracles (on the left) and another male figure (on the right, smaller in size) are shown standing at the sides of an altar, making a libation upon it. A tree is visible in the background. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0460 | 9815 | 2102 | Votive plate of Mithras | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | 2nd century AD | RAMP ** | Kurtovo Konare | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [26] |

| Description: The relief contains a complex iconography of divine figures and symbols. The background in the centrepiece is cut, i.e., an ajour style is used. Traces of red paint are preserved on the surface of the relief. The central image represents Mithras killing a sacred bull, an act called the tauroctony. Mithras, wearing a Phrygian cap, is kneeling on the exhausted bull, holding it by the nostrils with his left hand and stabbing it with his right. A dog and a snake reach up towards the blood. At the top left is Sol, and at the top right is Luna. The central tauroctony is framed by a series of subsidiary scenes illustrating events in the Mithras narrative. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0461 | 9816 | II-730 | Votive plate of the Thracian horseman | Marble | White/greyish colour; medium-to-coarse-grained | 3rd century AD | RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [26] |

| Description: The plate has a trapezoidal shape, rounded at the top. A frame is formed at the bottom. Traces of red paint are preserved on the surface of the relief. The rider is turned to the right, and a chlamys flutters behind him. A hunting scene occurs under the images of the horse and the horseman. The Three Nymphs and a temple facade are depicted in the upper right corner of the plaque. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0462 | 9817 | 2103 | Votive plate | Marble | White/greyish colour; medium-grained. | 2nd–3rd century AD | RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Unknown *** |  | IGBulg III,1 959 |

| Description: Depicts a three-headed Thracian horseman. The plate has a trapezoidal shape, rounded at the top. The plaque is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. An inscription is incised in the broader part of the frame, and a small round hole is drilled through it. The three-headed rider is turned to the right, and a chlamys flutters behind him. He holds a double axe in his right hand. A hunting scene occurs under the images of the horse and the horseman. At the right end of the relief, a pedestal and two standing figures above it are depicted. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0472 | 9827 | II-1026 | Fragment of a votive relief | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad | n/a | n/a |

| Description: The centrepiece is set between two columns, and the shafts are broken off. Two Corinthianising capitals support the entablature. Herakles, on the right, is represented frontally, with his head turned to the right towards the Amazon. The skin of the Nemean lion is slung over his right arm. The Amazon is represented with her head tilted back. Her chiton is unfastened at one shoulder. Her left arm is folded up, holding a round object. There are traces of paint. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0474 | 9829 | 2219 | Fragment of a votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |   | [27] (p. 46, Figure 36) |

| Description: An inscription is incised on the frame at the lower end of the plaque. A very small part of the relief is preserved, including a foot. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0476 | 9831 | 3952 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; ultra-fine-grained. | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [28] |

| Description: Depicts a Thracian horseman. The plaque is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. An inscription is incised on the wider part of the frame. The upper part of the plate, together with most of the rider and the horse’s head, is broken off. The rider is turned to the right. The horse’s front left leg is folded and lifted into the air. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0478 | 9833 | 4040 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | End of the 2nd–3rd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | IGBulg III,1 1460 |

| Description: Depicts a Thracian horseman. The plate has a trapezoidal shape, probably rounded at the top, where it is largely broken off. The plaque is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. An inscription is incised on the wider part of the frame. The rider is turned to the right, and a chlamys flutters behind him. He holds a spear in his right hand. The horse’s front legs are raised in the air. Below them, there is a shallow image of a dog. A pedestal or an altar is partially depicted in the lower right corner of the relief. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0482 | 9837 | II-1579 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; ultra-fine-grained. | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [29] (p. 134) |

| Description: Depicts Asclepius, Hygieia, and Telesphorus. The plate has a trapezoidal shape, rounded at the top. It is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. On the right is Asclepius with a serpent, on the left is Hygia, and in the space above and between them is Telesphorus. The relief of the images is low; the figures are schematic, and no details are presented. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0483 | 9838 | II-1545 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; ultra-fine-grained. | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [29] (p. 133) |

| Description: With two divine figures. The plate has a trapezoidal shape, rounded at the top. The plaque is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. On the right is a goddess (Hera/Tyche) depicted with a high cylindrical crown (kalathos?) and cornucopia on the left hand and steering oar in the right, and on the left is a god (Hermes) depicted with a purse in his right hand and a stylised caduceus (?) in his left hand. The relief of the images is shallow, and no details are presented. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0484 | 9839 | II-1546 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-to-medium-grained. | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [29] (p. 133) |

| Description: Depicts Hermes and Hera. The plate has a trapezoidal shape, rounded at the top. The plaque is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. On the right is Hermes, depicted with a purse in his right hand, and on the left is Hera, depicted holding a patera in her right hand and a sceptre in her left hand. The two figures are presented frontally. The relief of the images is low; the figures are schematic, and no details are presented. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0485 | 9840 | II-275 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals. | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [29] (p. 135) |

| Description: Depicts Hera. The plate has a trapezoidal shape, rounded at the top. The plaque is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. An inscription is incised on the wider part of the frame. The relief depicts Hera holding a patera in her right hand and a sceptre in her left hand. The figure is presented frontally. Beneath the patera, in the lower left corner of the relief, there is an altar. The relief of the image is low; the figure is schematic, and no details are presented. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0486 | 9841 | II-36 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; coarse-grained | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [29] (p. 135) |

| Description: Depicts Hekate. The plate has a trapezoidal shape, rounded at the top. The plaque is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0487 | 9842 | II-1758 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained. | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [29] (p. 135) |

| Description: Depicts Hera and is split into two. The plate has a trapezoidal shape, rounded at the top. The plaque is surrounded by a frame that is wider at the lower part. The relief depicts Hera holding a patera in her right hand and a sceptre in her left hand. The figure is presented frontally. Beneath the patera, in the lower left corner of the relief, there is an altar. The relief of the image is low; the figure is schematic, and no details are presented. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0504 | 9859 | n/a | Fragment of relief | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | 2nd–3rd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad | n/a | n/a |

| Description: Only the right leg of a man is preserved. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0505 | 9860 | n/a | Votive relief | Marble | White colour; fine-grained. | 2nd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Asenovgrad | n/a | n/a |

| Description: Possibly a small statue of Cybele. The sculpture depicts the seated goddess, Cybele, the Mother Goddess (Magna Mater), with two flanking lions. Cybele’s head and part of her arms are broken off. The lower part of her left arm is placed on an armrest. The goddess is wrapped in heavy drapery. Each lion sits by her side. The head of the left one is broken off. The goddess is presented on a much larger scale than the wild animals. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0477 | 9832 | 2241 | Votive relief | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | 2nd–3rd century AD | Depot of the RAMP | Plovdiv | n/a | Prokonnesos |  | IGBulg III,1 1133 |

| Description: Depicts Asclepius and Telesphorus. The small-sized sculpture represents the figures of Asclepius in the middle, Telesphorus on the right, and the entwined snake on a baton on the left. The head, torso and arms of Asclepius, as well as the head of Telesphorus and the upper part of the serpent, are broken off. The two gods are depicted with bare feet. The figures are placed on a plain rectangular base on which an inscription is incised. | ||||||||||||

3. Methodology

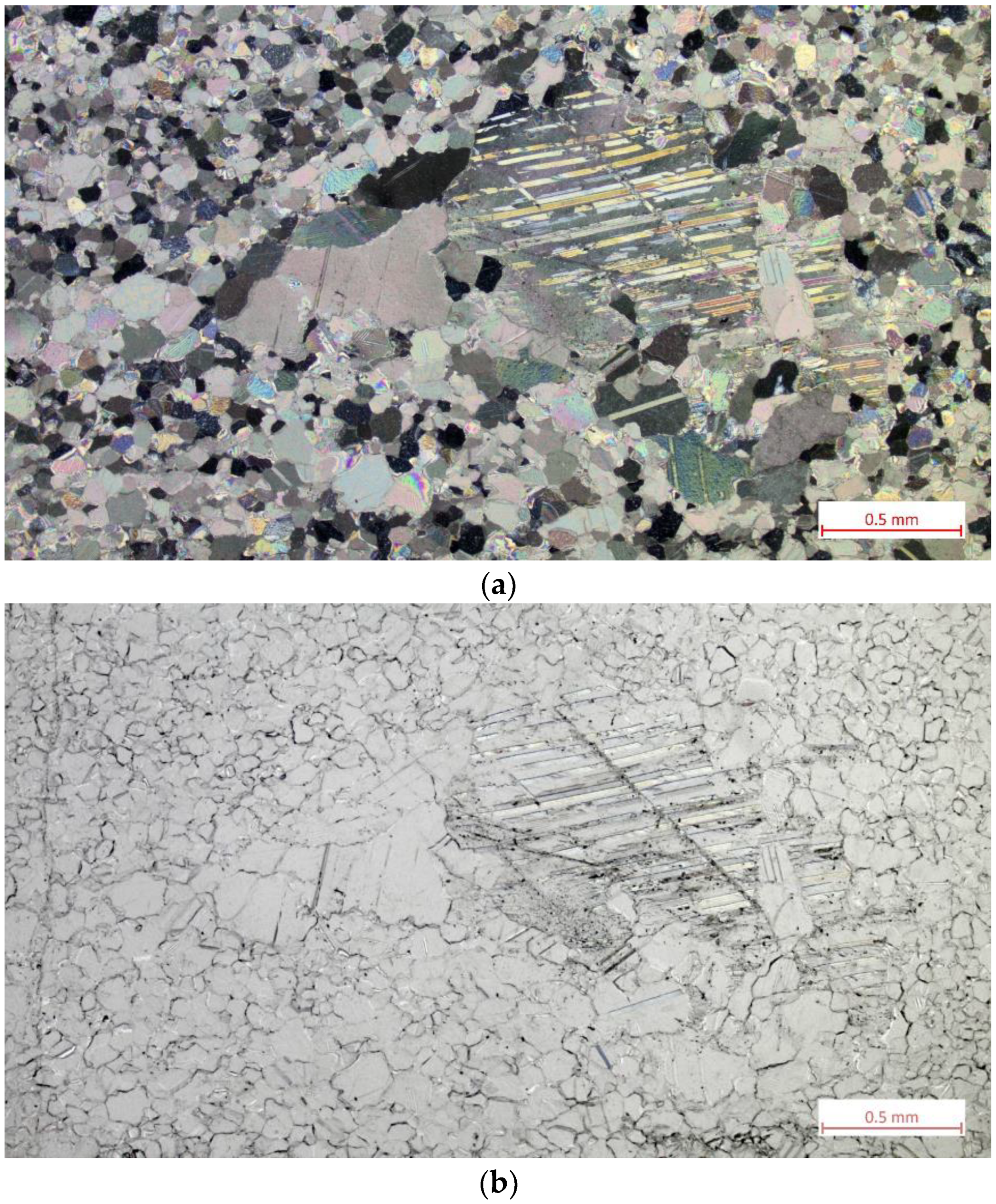

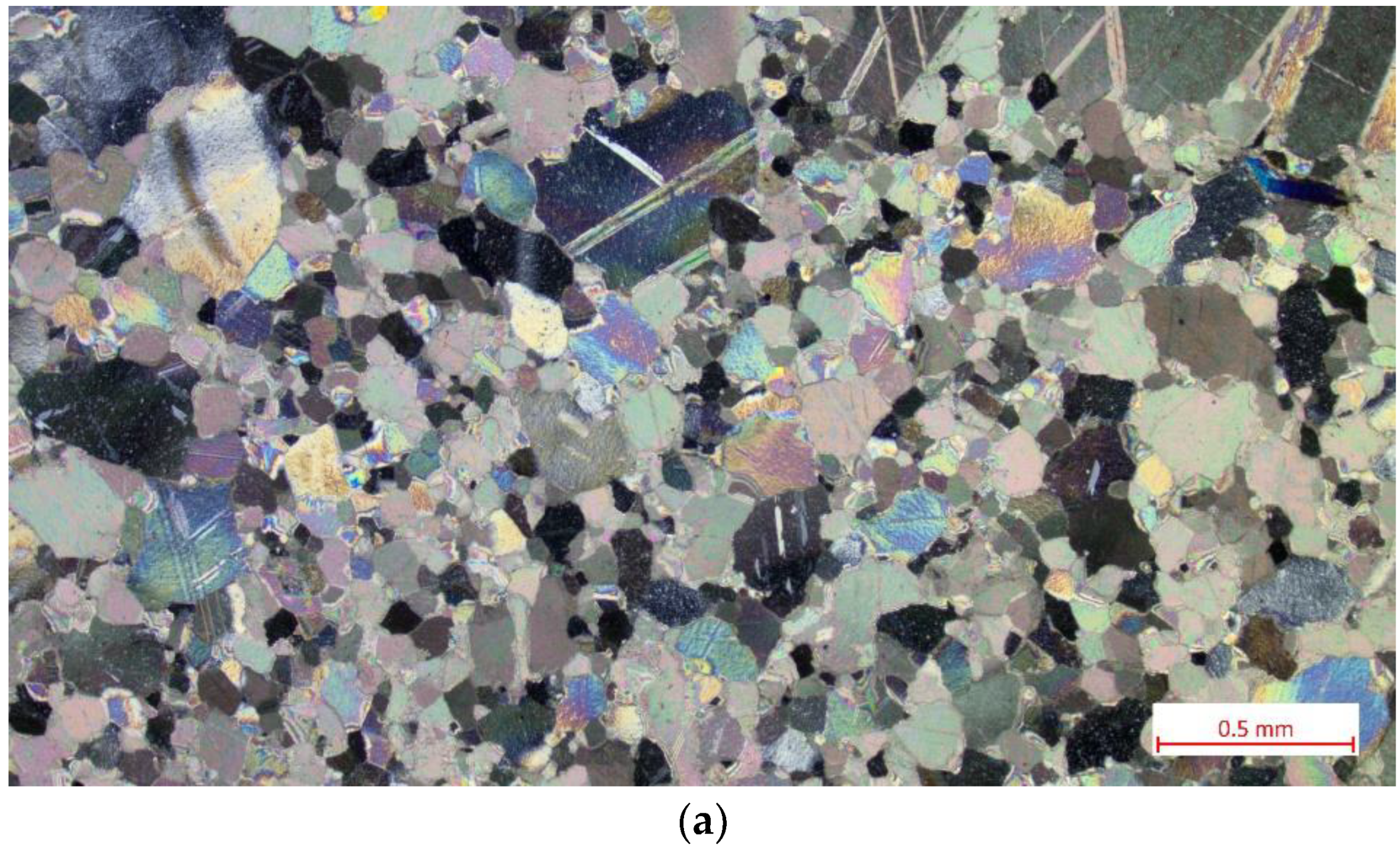

3.1. Microscopy

3.2. Isotope Analysis

3.3. Trace Element Analysis

4. Provenance Results

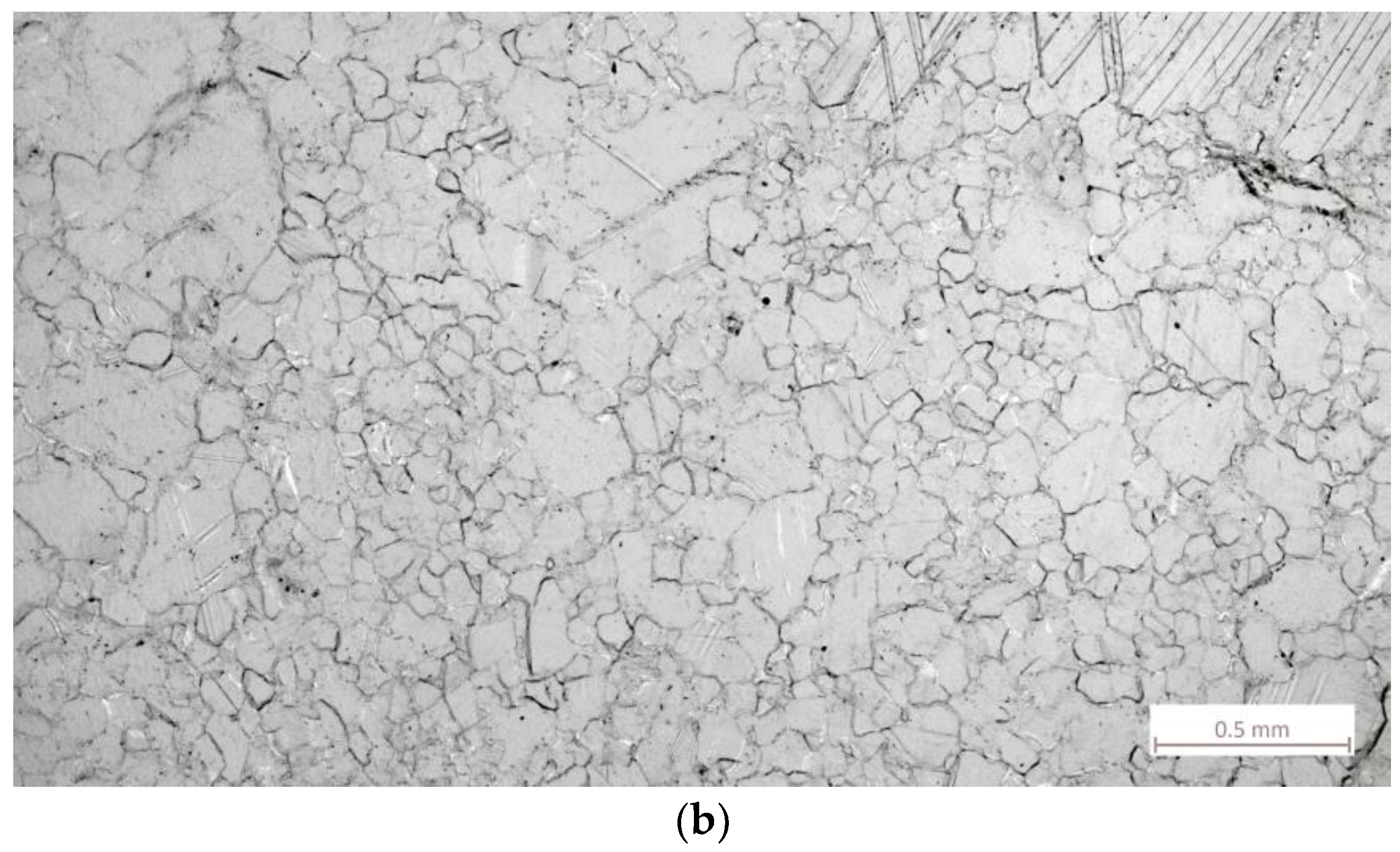

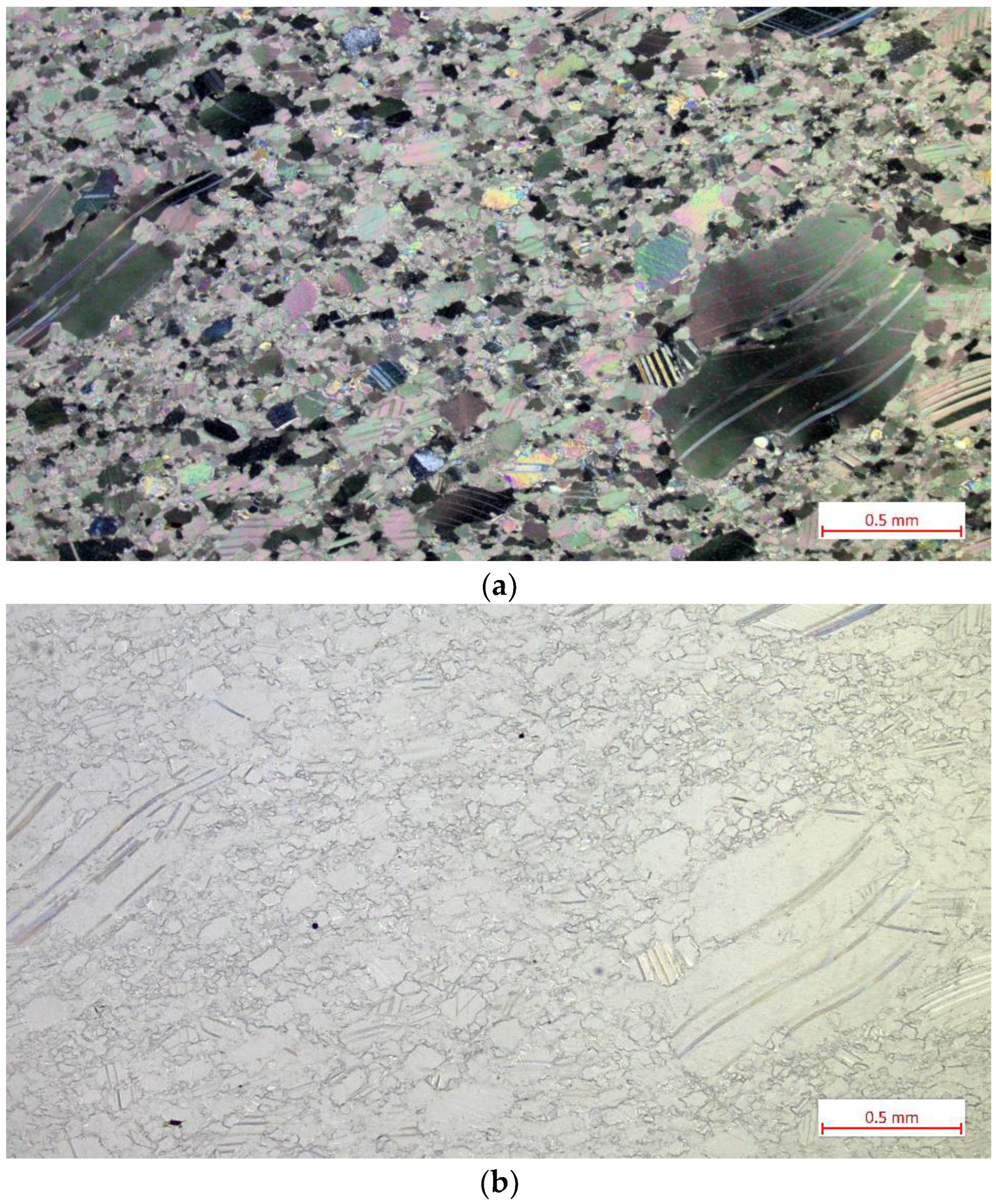

4.1. Petrographic Data

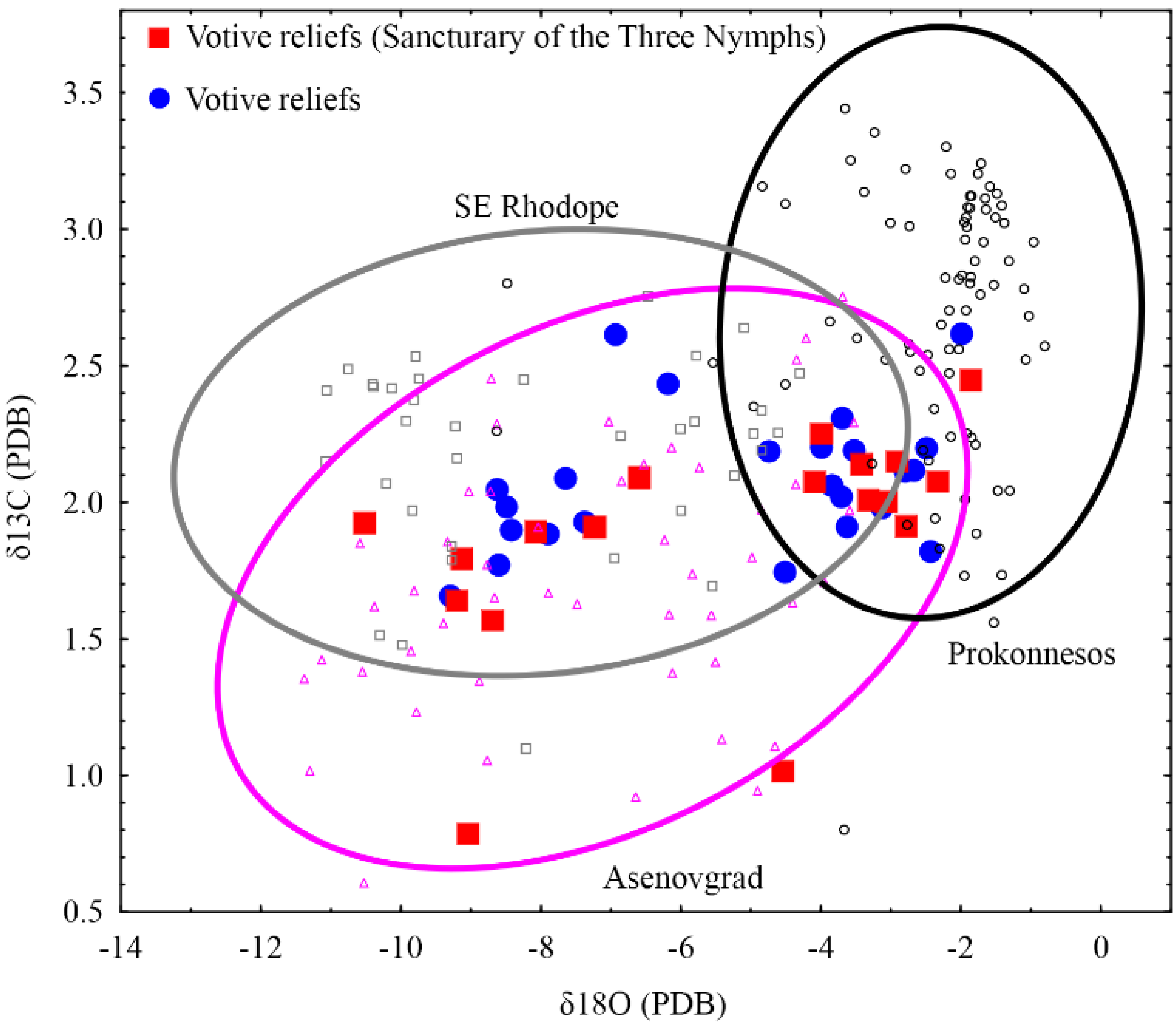

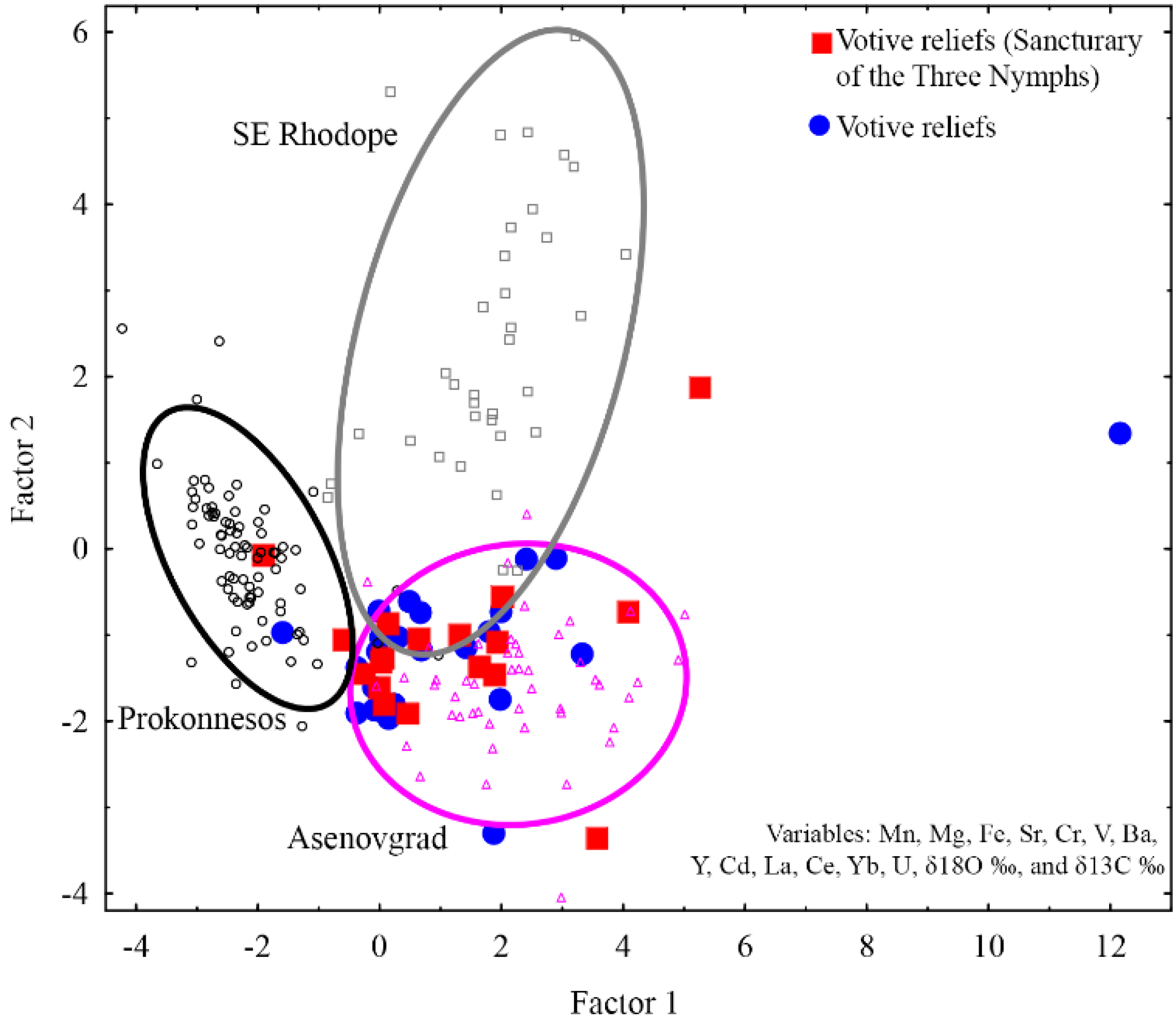

4.2. Geochemical Data

- Distance: Distance of the sample under consideration from the centre of the ellipse. This centre is the average value of the quarry probability field.

- Relative (posterior) probability: This probability is the degree of likelihood of a sample belonging to a given group (within the selected number of groups). Results below 60% indicate that the sample probably cannot be assigned with certainty and that a second choice has to be considered.

- Absolute (typical) probability: This is the measure of the probability that a sample belongs to a given population. Samples in the centre of the probability ellipse have a high absolute probability. The threshold is 10%, corresponding to samples on the edge of the 90% probability ellipse. Low values indicate anomalous samples (outliers) or samples possibly not belonging to any group in the selection.

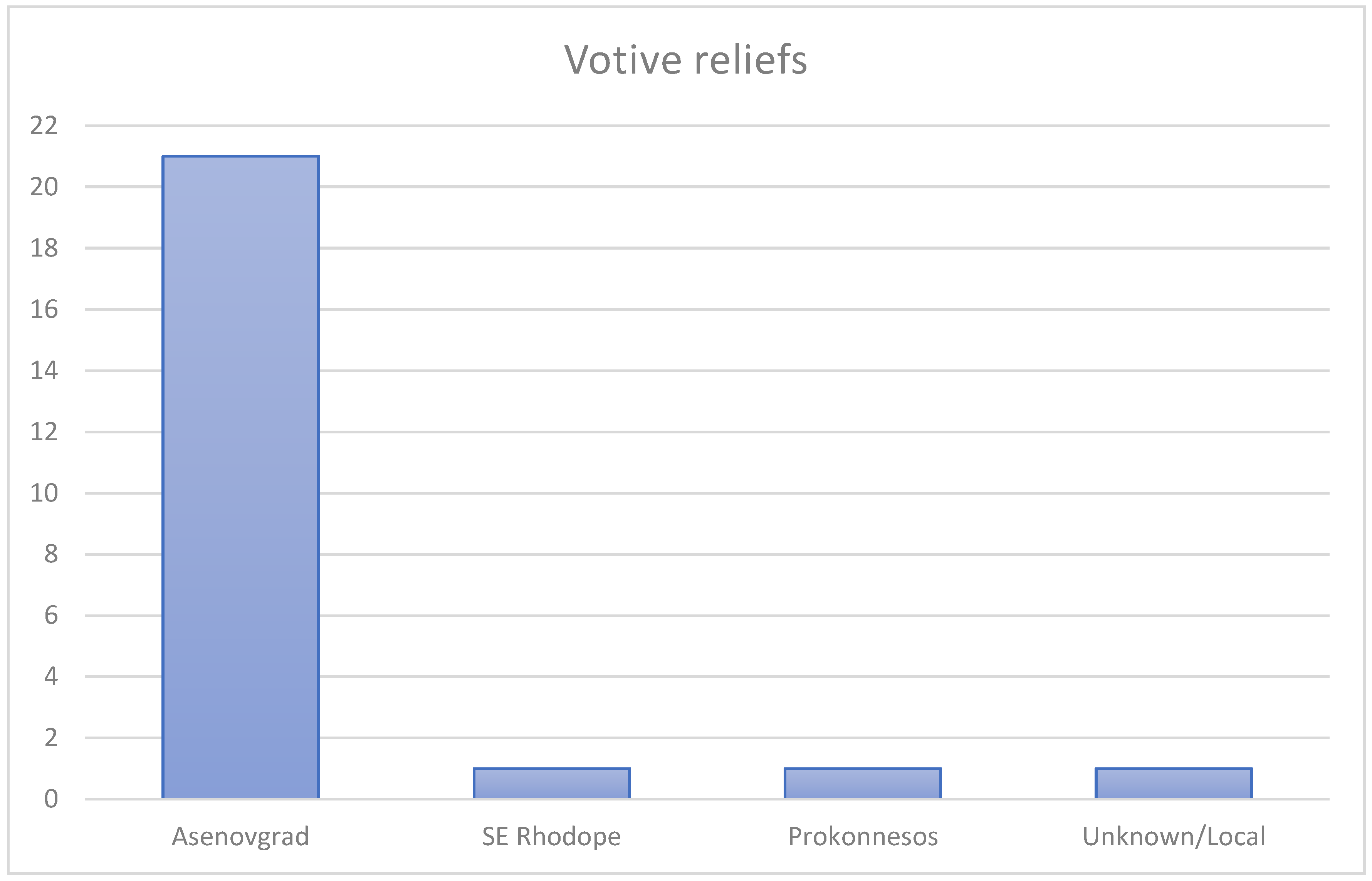

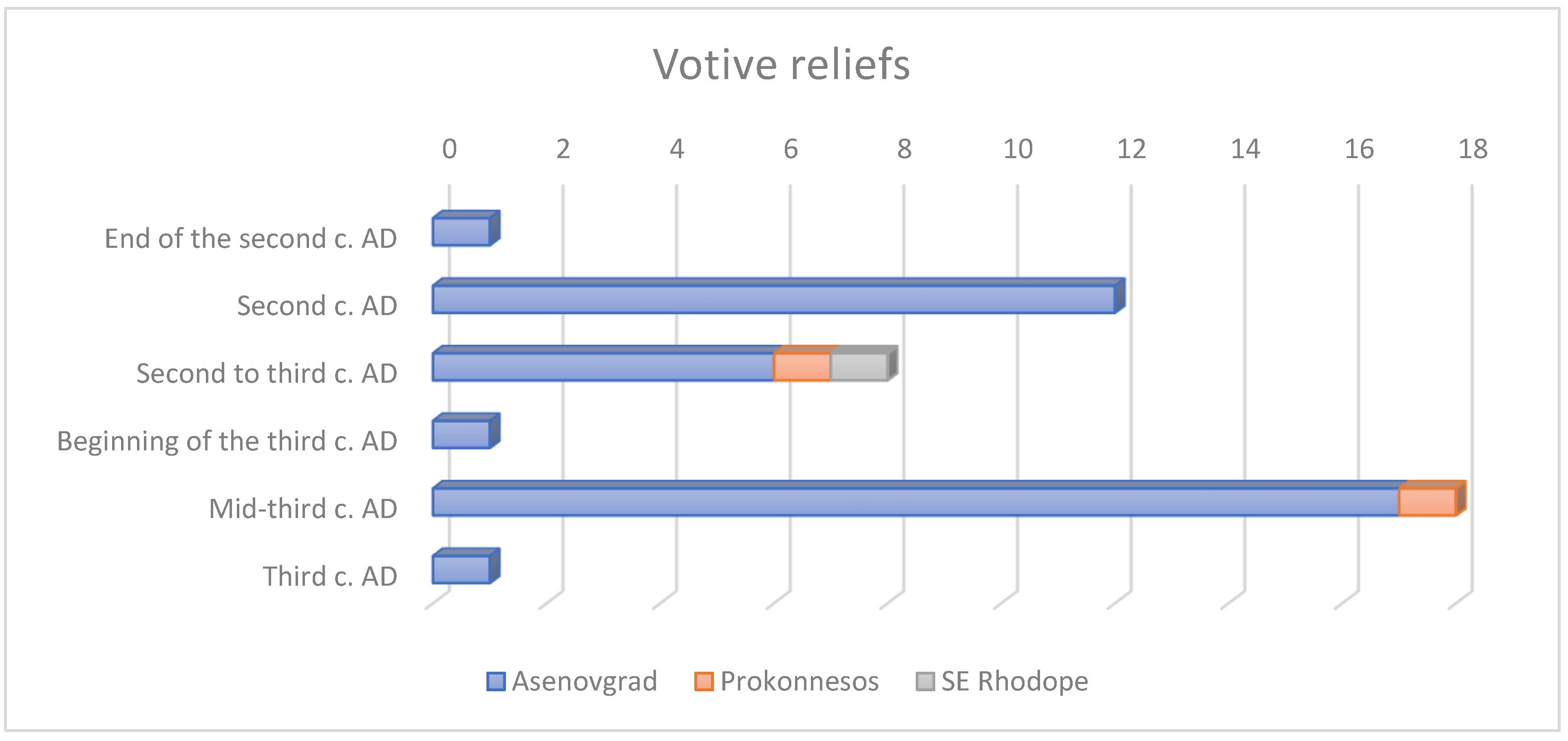

5. Discussion

5.1. Materials

5.2. The Chronological Distribution

5.3. The Use of Asenovgrad Marble in Other Cultic Contexts and Workshops

5.4. Marble Transport and Regional Connectivity

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pedley, J. Sanctuaries and the Sacred in the Ancient Greek World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M. Space and Society in the Greek and Roman Worlds; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dobruski, V. Materiali po arheologijata na Bulgarija. SbNUNK 1896, 13, 398–442. [Google Scholar]

- Gocheva, Z. Trakijsko svetilishhe na Nimfite pri s. Ognjanovo. In Studia Archaeologica. Suppl. II. Sbornik Izsledvanija v Chest na Prof. Atanas Milchev; UI “Sv. Kliment Ohridski”: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2002; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Karadimitrova, K. Pametnici na kulta na trite Nimfi ot NAM. GNAM 1992, 8, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, P.; Anevlavi, V.; Frerix, B.; Cenati, C.; Prochaska, W.; Ladstätter, S.; Karadimitrova, K. A contribution to the urbanization and marble supply of Roman Thrace: An interdisciplinary study. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2024, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anevlavi, V.; Prochaska, W.; Cenati, C.; Ivanov, I.; Ladstätter, S.; Popov, H.; Georgiev, P.; Kabakchieva, G. Geochemical and petrographic investigation of the provenance of white marble decorative elements from the Roman Villa Armira in south-eastern Bulgaria. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2022, 14, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anevlavi, V.; Prochaska, W.; Andreeva, P.; Ladstätter, S. New Evidence of the Supra-regional Marble Trade Network in Thrace, through the Archaeometric Study of Sculptures in Roman Philippopolis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2025, 174, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, W. The challenge of a successful discrimination of ancient marbles (part II): A databank for the Alpine marbles. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 38, 102958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, W.; Attanasio, D. The challenge of a successful discrimination of ancient marbles (part I): A databank for the marbles from Paros, Prokonnesos, Heraklea/Miletos and Thasos. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 35, 102676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, W.; Attanasio, D. The challenge of a successful discrimination of ancient marbles (part III): A databank for Aphrodisias, Carrara, Dokimeion, Göktepe, Hymettos, Parian Lychnites, and Pentelikon. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2022, 45, 103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, W.; Ladstätter, S.; Anevlavi, V. The challenge of a successful discrimination of ancient marbles (part IV): A databank for the white marbles from the region of Ephesos. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2024, 53, 104336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovachev, V. (Ed.) Gold, Copper Mining and Geoarchaeology in Central Bulgaria. ACTA Mineralogica-Petrographica, Field Guide Series; Department of Mineralogy, Geochemistry and Petrology, University of Szeged: Szeged, Hungary, 2010; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zagorchev, I. Introduction to the Geology of SW Bulgaria. Geol. Balc. 2001, 31, 3–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valchev, I. Izvangradskite Svetilishta V Rimskata Provintsiya Trakiya (I–IV Vek); Universitetsko Izdatelstvo “Sv. Kliment Ohridski”: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koleva, M. Rimska Idealna Skulptura ot Balgariya; Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimov, T. Beležzki vărhu Pitiĭskite, Aleksandriĭskite i Kendri-zĭskite igri vaskite igri va\u030vr Filipopolis. In V Izsledvaniya v chest na akad Dimitŭr Dechev; Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1958; pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Sharankov, N. The Thracian κοινόν: New Epigraphic Evidence. In Thrace in the Graeco-Roman World. In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Thracology, Komotini and Alexandroupolis, Greece, 18–23 October 2005; Iakovidou, A., Ed.; National Hellenic Research Foundation: Athens, Greece, 2007; pp. 518–538. [Google Scholar]

- Boteva, D. Further considerations on the votive reliefs of the Thracian Horseman. In Moesica et Christiana. Studies in Honour of Professor Alexandru Barnea; Panaite, A., Cârjan, R., Căpiţă, C., Eds.; Muzeul Brăilei “Carol I”: Brăila, Romania, 2016; pp. 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Boteva, D. Monuments and nature of the so-called Thracian Horseman again and not for the last time. In Συμπόσιον: Studies in Memory of Prof. Dimitar Popov; Delev, P., Ed.; St. Kliment Ohridski University Press: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, R. (Ed.) Tabula Imperii Romani. K35/2, Philippopolis; Tendril Publishing House: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tacheva-Hitova, M. Istorija na Iztochnite Kultove v Dolna Mizija i Trakija (VI v. pr. n. e.—IV v. ot. n. e.); Nauka i Izkustvo: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Katsarov, G.I. Die Denkmäler des Thrakischen Reitergottes in Bulgarien; Karl W. Hiersemann: Leipzig, Germany, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Velkov, I. Antični Pametnici iz Bǎlgarija. Godiš. Narodn. Muz. 1922, 1921, 198–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rabadjiev, K. The Triumph of Dionysos (and Herakles?). In Studia in Honorem Christo Danov, Thracia 12; Serdicae: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1998; pp. 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, P. Deo Soli Invicto Mithrae—Mithra’s Invincible Sun God; Sema RSH: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2021; ISBN 978-954-9670-52-3. [Google Scholar]

- Topalilov, I. Philippopolis. The city from the 1st to the beginning of the 7th century. In Roman Cities in Bulgaria; Ivanov, R., Ed.; National Archaeological Institute with Museum: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 363–437. [Google Scholar]

- Mihailov, G. (Ed.) Inscriptiones Graecae in Bulgaria Repertae, Vol. III,1. Inscriptiones inter Haemum et Rhodopem Repertae. In Fasciculus Prior: Territorium Philippopolis; (IGBulg III,1); RIVA: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Cherneva, S. Unfinished Marble Monuments from Philippopolis: An evidence of local production. Annu. Reg. Archaeol. Mus. 2009, 11, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaria, S.; Bonetto, J.; Germinario, L.; Previato, C.; Girotto, C.; Mazzoli, C. The stone artifacts of the National Archaeological Museum of Adria (Rovigo, Italy): A noteworthy example of heterogeneity. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2024, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffendale, D.P.; Marra, F.; Gaeta, M.; Terrenato, N. Combining geochemistry and petrography to provenance Lionato and Lapis Albanus tuffs used in Roman temples at Sant’Omobono, Rome, Italy. Geoarchaeology 2019, 34, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluhak, T.M.; Hofmeister, W. Geochemical provenance analyses of Roman lava millstones north of the Alps: A study of their distribution and implications for the beginning of Roman lava quarrying in the Eifel region (Germany). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 1603–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilaria, S.; Ricci, G.; Secco, M.; Beltrame, C.; Costa, E.; Giovanardi, T.; Bonetto, J.; Artioli, G. Vitruvian binders in Venice: First evidence of Phlegraean pozzolans in an underwater Roman construction in the Venice Lagoon. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, L.; Sottili, G.; Marra, F.; Ventura, G. Provenancing of lightweight volcanic stones used in ancient Roman concrete vaulting: Evidence from Rome. Archaeometry 2011, 53, 707–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poretti, G.; Brilli, M.; De Vito, C.; Conte, A.M.; Borghi, A.; Günther, D.; Zanetti, A. New considerations on trace elements for quarry provenance investigation of ancient white marbles. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 28, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, M.S. Ancient stone quarries on the Iberian peninsula: Updated research and methodological approaches—AG Gutiérrez Garcia-Moreno, and P. Rouillard, eds. 2018. Lapidum natura restat: Canteras antiguas de la península ibérica en su contexto (cronología, técnicas y organización de la explotación); Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica and Casa de Velázquez: Tarragona and Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 197. J. Rom. Archaeol. 2021, 34, 499–505. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppiene, V.; Schüssler, U.; Unterwurzacher, M. Auerbach Marble Quarries in the Odenwald near Hochstädten. Min. Cult. Landsc. IES Yearb. 2013, 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Garcia-M, A.; Royo Plumed, H.; González Soutelo, S.; Savin, M.C.; Lapuente, P.; Chapoulie, R. The marble of O Incio (Galicia, Spain): Quarries and first archaeometric characterisation of a material used since Roman times. Archéosciences Rev. Archéom. 2016, 40, 103–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Lazzarini, L. An updated petrographic and isotopic reference database for white marbles used in antiquity. Rend. Lincei Sci. Fis. Nat. 2015, 26, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Elçi, H.; Yavuz, A.B.; Attanasio, D. Unknown ancient marble quarries of Western Asia Minor. In ASMOSIA IX. Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone. In Proceedings of the IX ASMOSIA Conference, Tarragona, Spain, 8–13 June 2009; Gutiérrez Garcia-M, A., Lapuente, P., Rodà, I., Eds.; Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica: Tarragona, Spain, 2012; pp. 562–572. [Google Scholar]

- Wielgosz-Rondolino, D.; Antonelli, F.; Bojanowski, M.J.; Gładki, M.; Göncüoğlu, M.C.; Lazzarini, L. Improved methodology for identification of Göktepe white marble and the understanding of its use: A comparison with Carrara marble. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2020, 113, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgosz-Rondolino, D.; Antonelli, F.; Bojanowski, M.J.; Degryse, P.; Gładki, M.; Göncüoğlu, M.C.; Lazzarini, L.; Long, L.; Mandera, S. Ancient white and grey marbles from Aphrodisias: Multi-method characterization. Archaeometry 2024, 66, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anevlavi, V.; Prochaska, W.; Dimitrov, Z.; Ladstätter, S. Provenance Matters. A Multi-Proxy Approach for the Determination of White Marbles from Villa Armira, Bulgaria. In Proceedings of the ASMOSIA XII—Association for the Study of Marble & Other Stones in Antiquity XII, Izmir, Turkey, 8–14 October 2018; International Conference Proceedings. Yavuz, A.B., Yolaçan, B., Bruno, M., Eds.; Publisher: Dokuz Eylül University Publications: Izmir, Turkey, 2023; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, W.H.; Dennen, W.H. Principles of Mineralogy; Wm. C. Brown Publishers: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lepsius, G.R. Griechische Marmorstudien; Verlag der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Berlin, Germany, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Moltesen, M. The Lepsius Marble Samples; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, H.; Craig, V. Greek marbles: Determination of provenance by isotopic analysis. Science 1972, 176, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, R. Isotopes in the Earth Sciences; Elsevier Applied Science: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio, D.; Brilli, M.; Ogle, N. The Isotopic Signature of Classical Marbles; L’Erma di Bretschneider: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, M.; Walker, S. Stable isotope identification of Greek and Turkish marbles. Archaeometry 1979, 21, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polikreti, K. Detection of ancient marble forgery: Techniques and limitations. Archaeometry 2007, 49, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poretti, G. In Situ Analysis of White Marble from the Mediterranean Basin by LA-ICP-MS: Inferences on Provenance Based on Trace-Element Profiles. Ph.D. Thesis, Sapienza—University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 24 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anevlavi, V.; Andreeva, P.; Prochaska, W.; Karadimitrova, K. Cults and Materials: Provenance Investigations of the White Marble Votive Plaques from the Sanctuary of Apollo Γεικεσηνος in Roman Thrace. In Proceedings of the Workshop: “Danubian Riders”—Deconstruction of a Religious Assemblage; Kremer, Ed.; Vienna, forthcoming.

- Koleva, M. The Visual Language of Roman Art and Roman Thrace. In Izkustvovedski Cheteniya 2016; Tekstove, nadpisi, obrazi; Moutafov, E., Erdeljan, J., Eds.; Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2017; pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, W.; Anevlavi, V.; Chakarov, K.; Andreeva, P.; Sutev, I. Archaeometric Investigations on the Significance of Limestones in the Roman Provinces of the Southern Lower Danube. Minerals 2025, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, P.; Anevlavi, V.; Prochaska, W.; Ladstätter, S. Statuary in the marble trade networks of Roman Thrace: A case study of unfinished and replicated products. In Proceedings of the ASMOSIA XIII Conference, Vienna, Austria, 19–23 September 2022; Ladstätter, S., Prochaska, W., Anevlavi, V., Eds.; Sonderschriften des Österreichischen Archäologischen Instituts: Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 331–349. [Google Scholar]

- Zuglev, K. Antichni Arheologicheski Nahodki ot Asenovgradsko. Archaeologia 1965, 4, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Madzharov, M. Rimski patishta v Balgariya. Prinos v razvitieto na rimskata patna sistema v provintsiite Miziya i Trakiya. Roman Roads in Bulgaria: Contribution to the Development of Roman Road System in the Provinces of Moesia and Thrace; Faber: Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, A. Transport in Thracia. In Proceedings of the First International Roman and Late Antique Thrace Conference: Cities, Territories and Identities, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 3–7 October 2016; Vagalinski, L., Raycheva, M., Boteva, D., Sharankov, N., Eds.; Izvestiya na Natsionalniya arheologicheski institut 44; Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2018; pp. 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Sayar, M.H. Perinthos-Herakleia (Marmara Ereğlisi) und Umgebung. Geschichte, Testimonien, griechische und lateinische Inschriften; Denkschriften der philosophisch-historischen Klasse 269; Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Wien, Austria, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Raepsaet, G. Land Transport, Part 2: Riding, Harnesses, and Vehicles. In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World; Oleson, J.P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 580–605. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, S.G. The Transport of Heavy Loads in Antiquity: Lifting, Moving, and Building in Ancient Rome. In Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 1. Spoliierung und Transposition; Altekamp, S., Marcks-Jacobs, C., Seiler, P., Eds.; Topoi 15; Edition Topoi: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Riemer, H.; Förster, F. Donkeys, Camels, and the Logistics of Ancient Caravan Transport. In Caravans in Socio-Cultural Perspective. Past and Present; Clarkson, P.B., Santoro, C.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 145–173. [Google Scholar]

| Project Nr | Lab Nr | M. Nr * | Object | Material | Stone Description | Dating | Location | Find Spot | Details on Finding-Spot | Provenance Results | Photo | Bibliography |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWM0062 | 9249 | 1288 | Votive relief | Marble | White colour; coarse-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Philippopolis; Region | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: The three nymphs are holding hands under an arcade. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0099 | 9281 | 962 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. Parts of the lower frame are missing. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0100 | 9282 | n/a | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained with larger crystals. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Museum | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs and Apollo holding a patera over an altar. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0150 | 9283 | n/a | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals. | 2nd–3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | IGBulg III,1 1357 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. Greek inscription engraved on the frame. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0164 | 9284 | 1076 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | IGBulg III,1 1357 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. Greek inscription engraved on the frame. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0165 | 9285 | 2745 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs holding hands. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0166 | 9286 | 969 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-to-coarse-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three dancing nymphs. Greek inscription engraved on the frame. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0167 | 9287 | 965 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-to-coarse-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. Greek inscription engraved on the lower frame. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0168 | 9288 | 994 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-to-coarse-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs holding hands. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0169 | 9289 | 964 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; very fine-grained; ultra mylonite. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0170 | 9290 | 974 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; very fine-grained; brown spots; fine mylonite. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. Greek inscription engraved on the frame. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0347 | 9707 | 1014 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs holding hands. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0348 | 9708 | 1008 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Prokonnesos |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs holding hands; only a fragment showing the body of the rightmost nymph is preserved. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0349 | 9709 | 1010 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0350 | 9710 | 1009 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; fine-grained with larger crystals. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs holding hands. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0351 | 9711 | 1001 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0352 | 9712 | 1006 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs. | ||||||||||||

| FWM0353 | 9713 | 1007 | Votive plate | Marble | White colour; medium-grained. | Mid-3rd century AD | NAIM Depot | Ognyanovo Sanctuary of the three Nymphs | n/a | Asenovgrad |  | [5], pp. 189–195 |

| Description: Relief images of three nymphs holding hands. | ||||||||||||

| Sample | Distance | Abs. Prob. | Rel. Prob. | Provenance | Rel. Prob. | Provenance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. choice | 2. choice | ||||||

| Sanctuary of the Nymphs | |||||||

| 9249 | FWM0062 | 4.4 | 10.8 | 99.2 | Asenovgrad | 0.8 | Prokonnesos |

| 9281 | FWM0099 | 1.1 | 57.4 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9282 | FWM0100 | 3.0 | 21.4 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9283 | FWM0150 | 1.8 | 39.2 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9284 | FWM0164 | 0.1 | 94.2 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9285 | FWM0165 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9286 | FWM0166 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9287 | FWM0167 | 0.1 | 94.6 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9288 | FWM0168 | 6.1 | 4.6 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9289 | FWM0169 | 0.6 | 72.8 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9290 | FWM0170 | 3.8 | 14.9 | 99.9 | Asenovgrad | 0.1 | Prokonnesos |

| 9707 | FWM0347 | 1.8 | 39.3 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9708 | FWM0348 | 1.3 | 51.1 | 100.0 | Prokonnesos | 0.0 | Asenovgrad |

| 9709 | FWM0349 | 1.3 | 50.3 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9710 | FWM0350 | 2.9 | 22.4 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9711 | FWM0351 | 0.8 | 66.9 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9712 | FWM0352 | 4.9 | 8.4 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9713 | FWM0353 | 4.5 | 10.2 | 99.9 | Asenovgrad | 0.1 | Prokonnesos |

| Miscellaneous Votive Reliefs | |||||||

| 9243 | FWM0047 | 3.3 | 18.9 | 99.8 | Asenovgrad | 0.2 | Prokonnesos |

| 9244 | FWM0049 | 3.7 | 15.1 | 99.9 | Asenovgrad | 0.1 | Prokonnesos |

| 9264 | FWM0108 | 9.0 | 1.1 | 84.8 | Asenovgrad | 10.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9265 | FWM0112 | 1.2 | 53.1 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9267 | FWM0102 | 1.9 | 36.8 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9268 | FWM0104 | 4.9 | 8.3 | 99.1 | Asenovgrad | 0.9 | Prokonnesos |

| 9269 | FWM0105 | 1.0 | 60.4 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9815 | FWM0460 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 97.2 | Asenovgrad | 2.8 | Prokonnesos |

| 9816 | FWM0461 | 7.4 | 2.4 | 99.9 | Asenovgrad | 0.1 | Prokonnesos |

| 9817 | FWM0462 | 76.6 | 0.0 | 100.0 | Unknown Asenovgrad * | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9827 | FWM0472 | 3.0 | 21.4 | 99.9 | Asenovgrad | 0.1 | Prokonnesos |

| 9829 | FWM0474 | 1.0 | 59.1 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9831 | FWM0476 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9837 | FWM0482 | 2.7 | 25.6 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9838 | FWM0483 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 92.8 | Asenovgrad | 7.2 | Prokonnesos |

| 9839 | FWM0484 | 0.9 | 62.6 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9840 | FWM0485 | 5.2 | 7.4 | 99.6 | Asenovgrad | 0.4 | Prokonnesos |

| 9841 | FWM0486 | 1.0 | 59.0 | 100.0 | Asenovgrad | 0.0 | Prokonnesos |

| 9842 | FWM0487 | 3.9 | 13.7 | 99.6 | Asenovgrad | 0.4 | Prokonnesos |

| 9833 | FWM0478 | 1.2 | 97.2 | 99.3 | Asenovgrad | 0.7 | SE Rhodope |

| 9241 | FWM0041 | 1.1 | 95.2 | 96.0 | SE Rhodope | 2.9 | Asenovgrad |

| 9832 | FWM0477 | 2.0 | 84.6 | 99.2 | Prokonnesos | 0.7 | Dokimeion |

| 9859 | FWM0504 | 0.1 | 99.9 | 97.9 | Asenovgrad | 2.0 | SE Rhodope |

| 9860 | FWM0505 | 6.0 | 29.9 | 77.2 | Asenovgrad | 15.9 | Dokimeion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anevlavi, V.; Prochaska, W.; Andreeva, P.; Petkova, K.; Frerix, B. White Marble Sourcing and Regional Workshop Dynamics in Roman Thrace: An Archaeometric Study of Votive Reliefs. Minerals 2025, 15, 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15070670

Anevlavi V, Prochaska W, Andreeva P, Petkova K, Frerix B. White Marble Sourcing and Regional Workshop Dynamics in Roman Thrace: An Archaeometric Study of Votive Reliefs. Minerals. 2025; 15(7):670. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15070670

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnevlavi, Vasiliki, Walter Prochaska, Petya Andreeva, Kalina Petkova, and Benjamin Frerix. 2025. "White Marble Sourcing and Regional Workshop Dynamics in Roman Thrace: An Archaeometric Study of Votive Reliefs" Minerals 15, no. 7: 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15070670

APA StyleAnevlavi, V., Prochaska, W., Andreeva, P., Petkova, K., & Frerix, B. (2025). White Marble Sourcing and Regional Workshop Dynamics in Roman Thrace: An Archaeometric Study of Votive Reliefs. Minerals, 15(7), 670. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15070670