Pore Structure and the Multifractal Characteristics of Shale Before and After Extraction: A Case Study of the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Background

3. Experimental Methods

3.1. Shales and Experiments

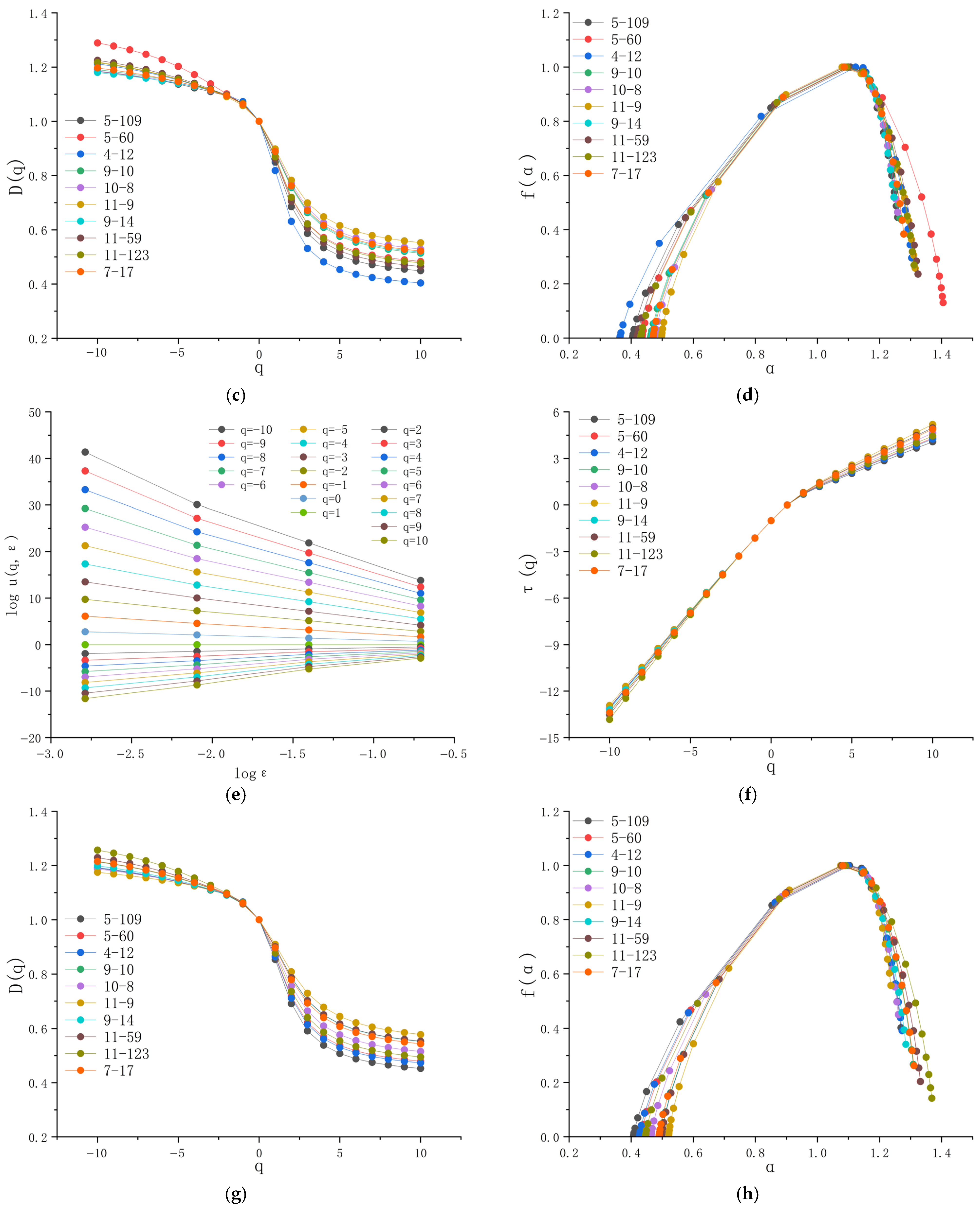

3.2. Multifractal Model

4. Results and Analysis

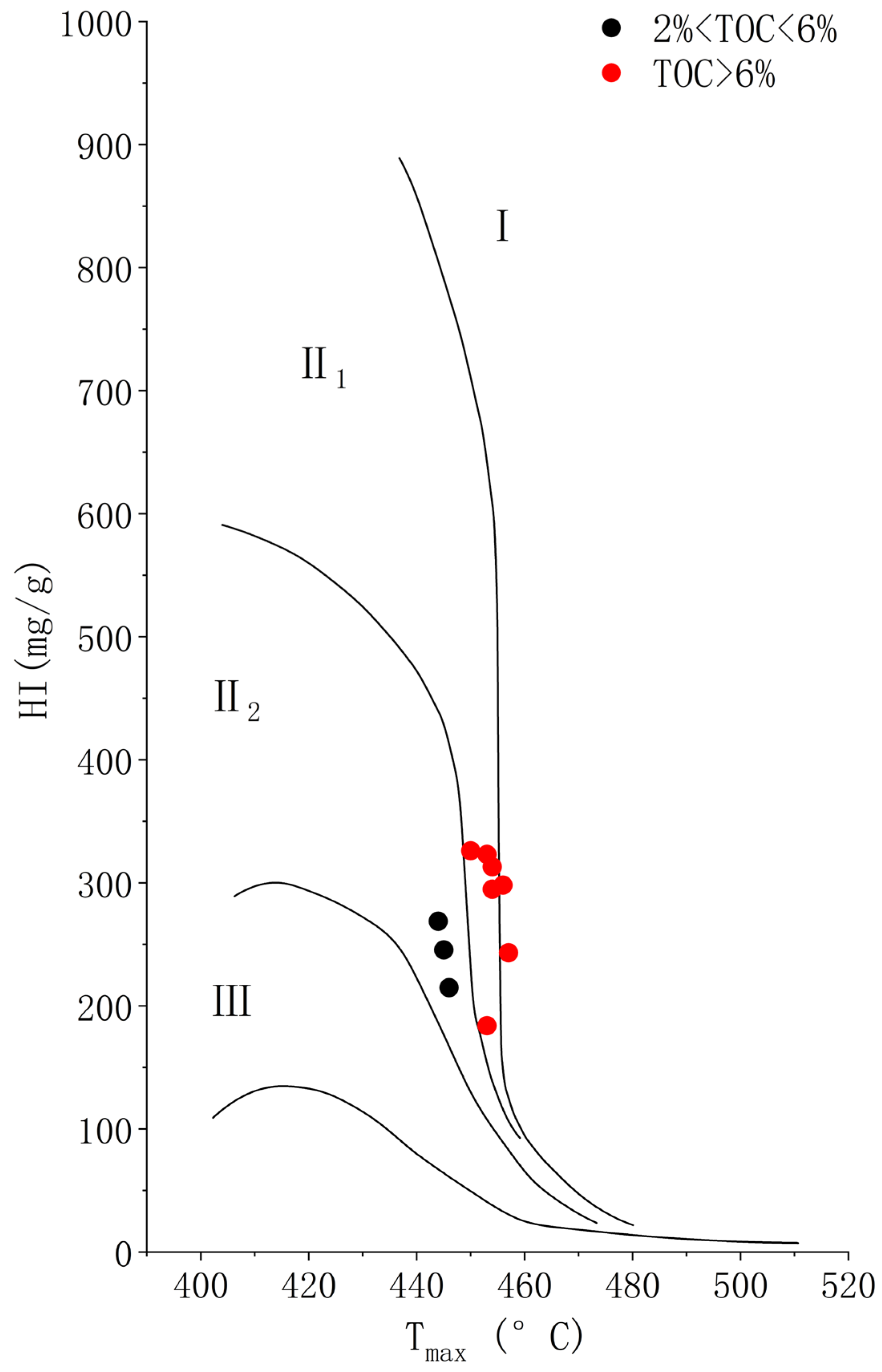

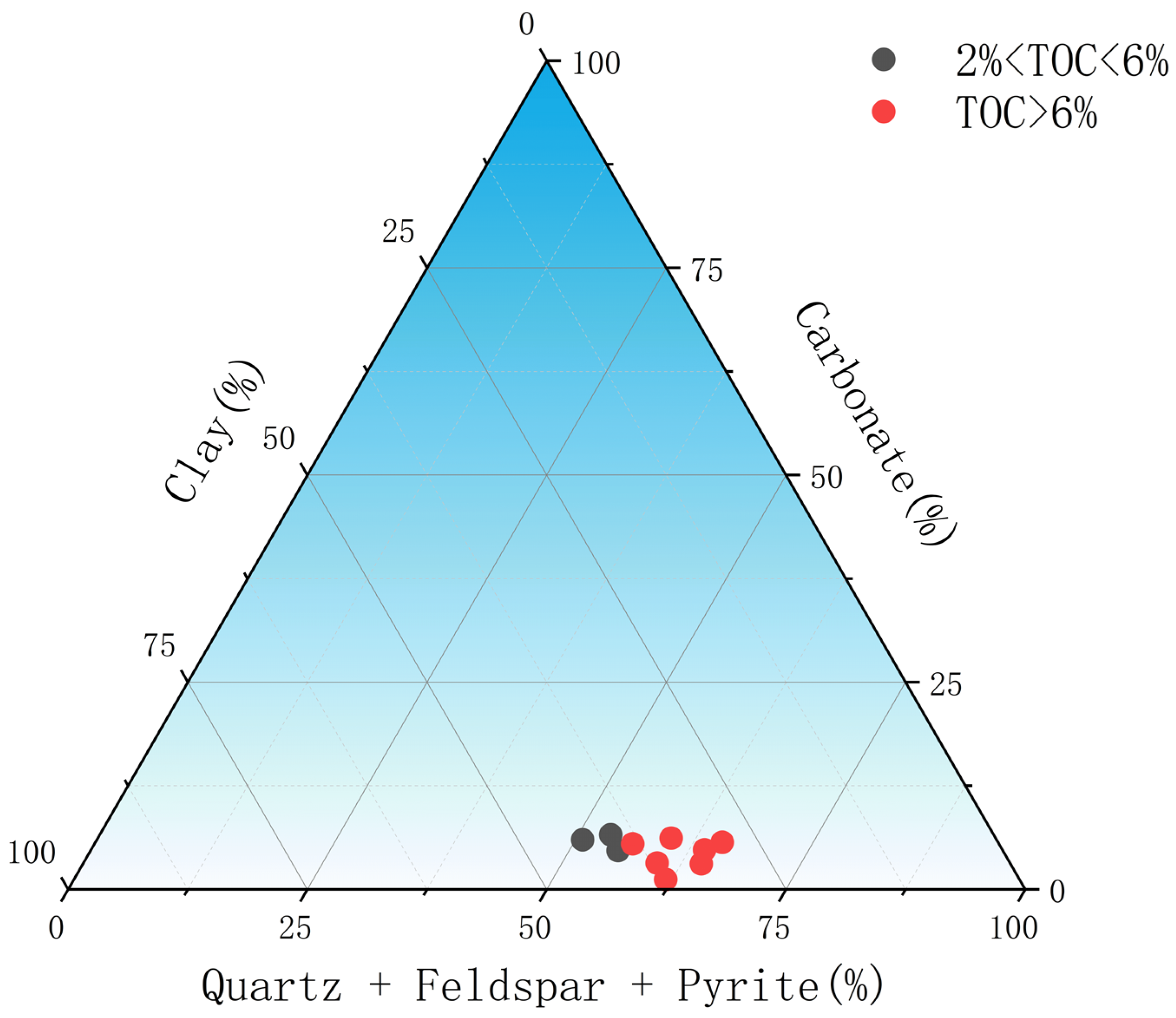

4.1. Organic Geochemical Characteristics and Mineral Composition

4.2. Reservoir Microscopic Pore Structure

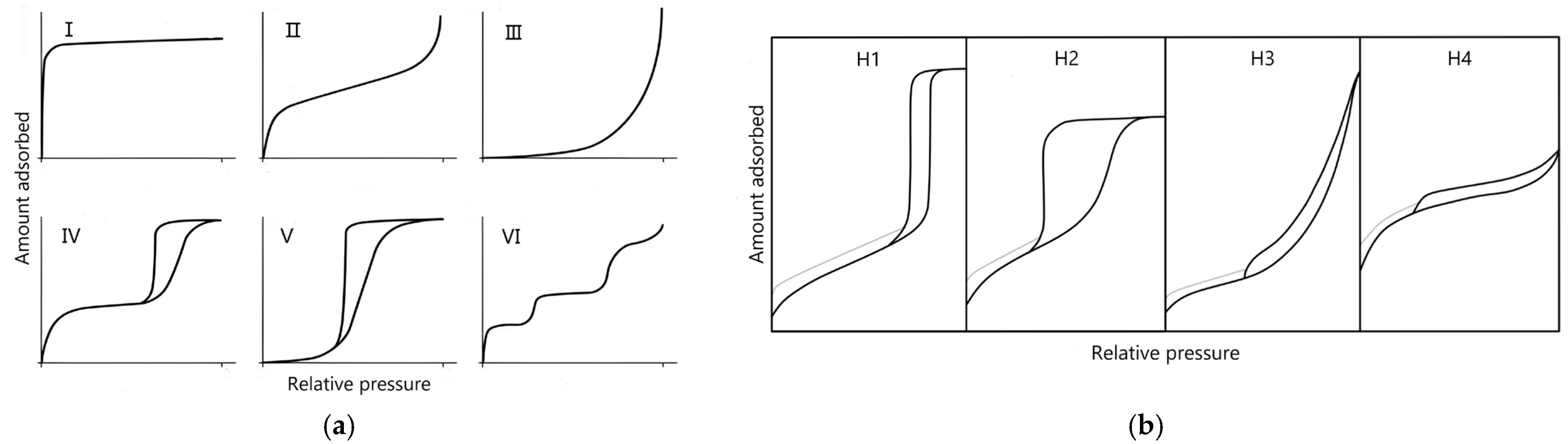

4.2.1. Nitrogen Adsorption Isotherm Characteristics

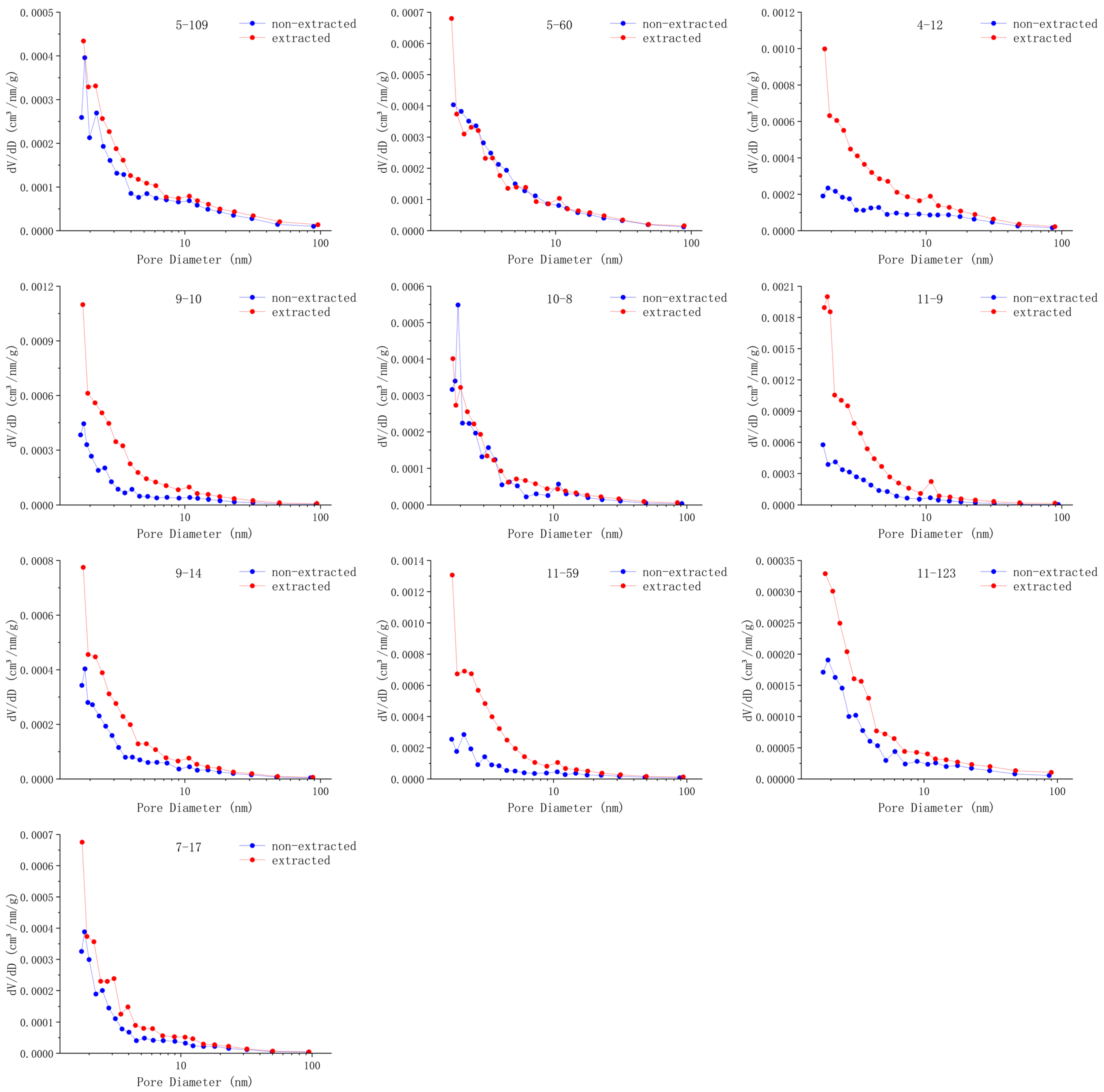

4.2.2. Nitrogen Adsorption Pore Size Distribution Characteristics

4.2.3. Characterization of Pore Structure Parameters

5. Discussion

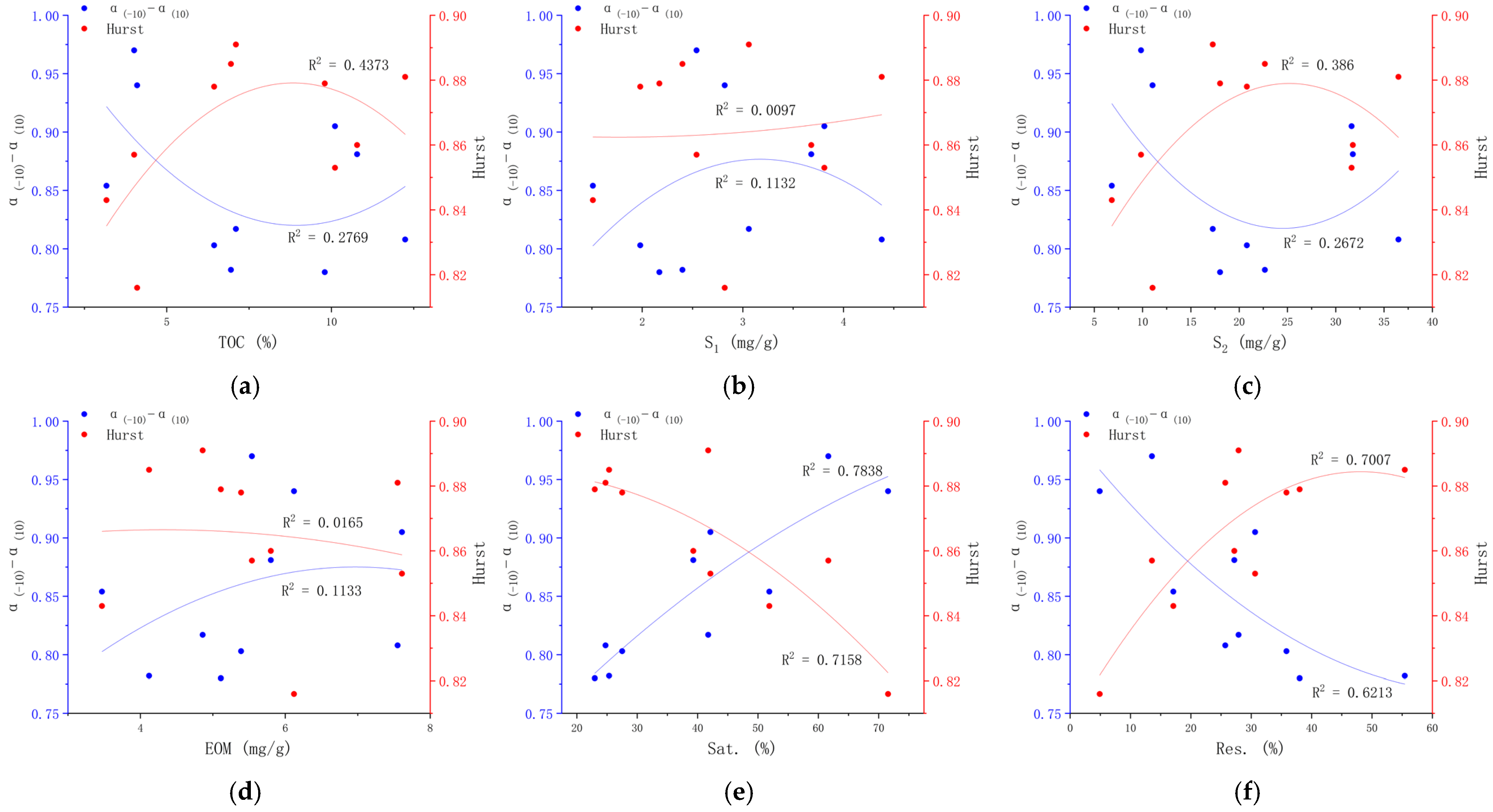

5.1. Relationship Between Fractal Dimensions and Pore Structure Parameters

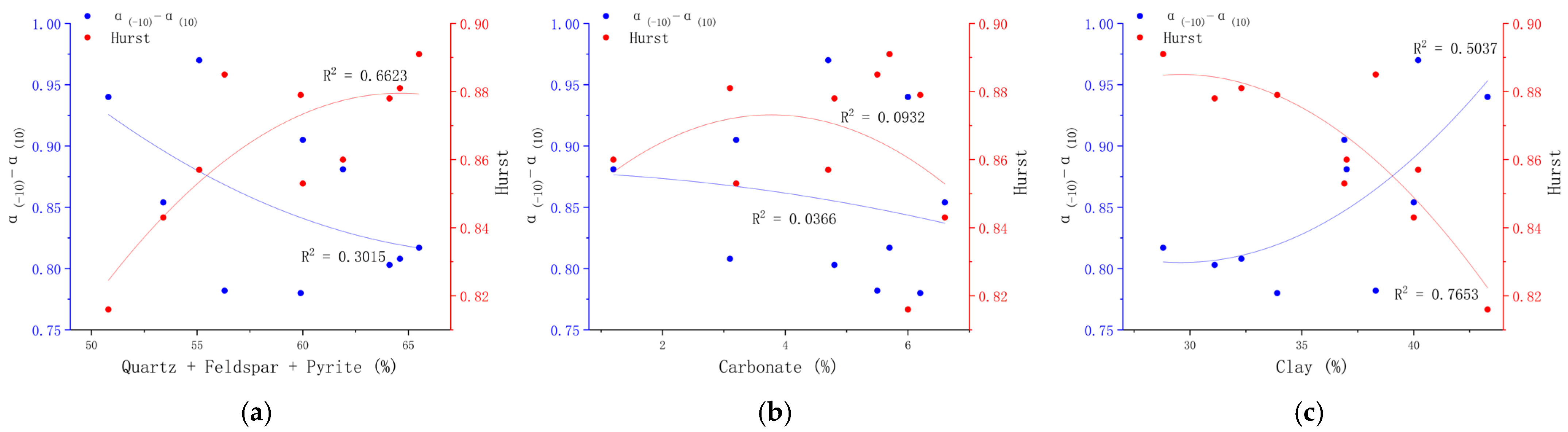

5.2. Influencing Factors of Pore Development

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- After extraction, the specific surface area (SSA) and total pore volume (TPV) of shale samples in the study area are both higher than those before extraction, while the average pore diameter (APD) exhibits inconsistent changes. Additionally, the pore size distribution becomes more concentrated, with improved pore homogeneity and connectivity. Compared to shale with medium organic matter abundance, shale with high organic matter abundance shows a more concentrated pore size distribution, as well as better pore connectivity and homogeneity.

- (2)

- Before extraction, the pore connectivity of shale in the study area is positively correlated with APD and TPV, whereas the opposite is true for pore heterogeneity. Furthermore, there is no correlation between pore connectivity/heterogeneity and SSA. After extraction, pore connectivity displays a strong positive correlation with APD and a weak positive correlation with SSA, with the inverse trend observed for pore heterogeneity. Moreover, pore connectivity and heterogeneity no longer show a correlation with TPV.

- (3)

- The pore connectivity of shale in the study area first increases and then decreases with the increase in total organic carbon (TOC) content and pyrolysis parameter S2 content. The better the pore connectivity of shale, the lower the content of light-component saturated hydrocarbons and the relatively higher the content of heavy-component resins in extractable organic matter (EOM). Brittle minerals can provide a rigid framework to inhibit compaction and are prone to forming natural microfractures under tectonic stress, thereby enhancing pore connectivity. In contrast, clay minerals, due to their plasticity, tend to deform and fill pore throats during compaction, thus reducing pore connectivity.

- (4)

- By establishing a multifractal analysis method and obtaining key parameters, this study systematically investigates the evolutionary patterns and controlling factors of shale pore structure before and after extraction. This work deepens the understanding of the complexity of storage spaces in continental shale oil reservoirs and provides new perspectives and a basis for evaluating reservoir quality in the Ordos Basin and other similar lacustrine shale formations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, R.; Liu, W.; Bai, B.; Wu, S.; Bian, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Lu, M.; et al. Progress in exploration theory and technology of continental shale oil in China. Pet. Sci. Bull. 2023, 8, 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, W. Research progress and scientific & technological issues in shale oil exploration and development in China. World Pet. Ind. 2024, 31, 1–11+13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Xing, H.; Xiong, T.; Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Hou, M.; Zhang, Y. Progress in exploration and development of medium-high maturity shale oil in CNPC. China Pet. Explor. 2023, 28, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Tao, S.; Hou, L.; Zhu, R.; Yuan, X.; Ran, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, Z. Concepts, characteristics, potential and technology of unconventional oil and gas: Discussion on the geology of unconventional oil and gas. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2013, 40, 385–399+454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yang, Z.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Wei, W.; Yang, F.; Cai, J. Fractal analysis of pore structure differences between shale and sandstone based on the nitrogen adsorption method. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 1759–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Jiang, Q.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Ma, Y.; Cao, T. Quantitative characterization of soluble organic matter in different occurrence states in lacustrine shale. Pet. Geol. Exp 2017, 39, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, J.; Wu, N.; Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Fu, Q. Evaluation of microscopic pore structure of tight sandstone in Chang 7 member of Yanchang Formation in Zhijing-Ansai area, Ordos Basin. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2024, 54, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ge, Y.; He, Y.; Pu, R.; Liu, L.; Duan, L.; Du, K. Quantitative characterization and dynamic evolution of pore structure in shale reservoirs of Chang 7 oil layer group in Yanchang area, Ordos Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2023, 44, 292–307. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Bao, Y.; Zhu, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D. Progress in occurrence characteristics, mobility experimental technology and research methods of shale oil. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2024, 31, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, M.; Qian, M.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Y. Quantitative characterization technology and application of shale oil in different occurrence states. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2016, 38, 842–849. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, C.; Liu, B.; Liu, G.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Chen, W.; Ning, C.; Wang, Z. Effect of pore structure on shale oil accumulation in the lower third member of the Shahejie formation, Zhanhua Sag, eastern China: Evidence from gas adsorption and nuclear magnetic resonance. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 88, 932–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Wheeler, J.A. The fractal geometry of nature. Am. J. Phys. 1983, 51, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.L.; Wang, J.S.Y. Fractal surfaces: Measurement and applications in the earth sciences. Fractals 1993, 1, 87–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guan, P.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X.; Ding, X.; You, Y. Research progress on characterizing pore structure features of unconventional oil and gas reservoirs using fractal theory. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2023, 59, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Hu, W.; Zhao, S.; Dong, S. Comparative analysis of pore structure and fractal characteristics of mud shale section in Xujiahe Formation of Well Ledi 1, Sichuan Basin. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2018, 45, 709–721. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhu, T.; Luo, F.; Liu, K. Using Fractal Theory to Study the Influence of Movable Oil on the Pore Structure of Different Types of Shale: A Case Study of the Fengcheng Formation Shale in Well X of Mahu Sag, Junggar Basin, China. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ostadhassan, M.; Zou, J.; Gentzis, T.; Rezaee, R.; Bubach, B.; Carvajal-Ortiz, H. Multifractal analysis of gas adsorption isotherms for pore structure characterization of the Bakken Shale. Fuel 2018, 219, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, H.; Karperien, A.; Corforth, D. Micro-mod: An L-systems approach to neural modelling. In Proceedings of the Sixth Australia-Japan Joint Workshop on Intelligent and Evolutionary Systems, Canberra, Australia, 30 November–1 December 2002; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, H.; Song, X. Multifractal analysis of Hg pore size distributions of tectonically deformed coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2015, 144–145, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jiang, Z.; Ji, W.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, L.; Yin, L. Heterogeneity of intergranular, intraparticle and organic pores in Longmaxi shale in Sichuan Basin, South China: Evidence from SEM digital images and fractal and multifractal geometries. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 72, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, H.; Wang, T.; Tang, T.; Li, W.; Zhu, G.; Chen, X. Difference between of coal and shale pore structural characters based on gas adsorption experiment and multifractal analysis. Fuel 2024, 371, 132044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Tuo, J.; Zhang, M.; Wu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y. Formation and development of the pore structure in Chang 7 member oil-shale from Ordos Basin during organic matter evolution induced by hydrous pyrolysis. Fuel 2015, 158, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; An, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, G.; Guo, R.; Hao, Z.; Liu, P.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, B. Pore structure heterogeneity of Chang 7 shale in the Ordos Basin: Insights from NMR and multifractal theory. Pet. Geosci. 2025, 31, petgeo2024-050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, R.; Lu, J.; Feng, D.; Liu, Y.; Shen, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, G.; He, J. Comparison of reservoir characteristics and differential evolution patterns between continental shale and its interbeds. Oil Gas Geol. 2023, 44, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Li, F.; Yang, D.; Wu, J.; Duan, Y.; Yang, T. Characteristics and controlling factors of reservoir space in laminated shale oil of Chang 7 member, Yan’an area, Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2025, 36, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; You, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, H.; Wu, S.; Yue, D.; Zhang, H. Pore Structure and Factors Controlling Shale Reservoir Quality: A Case Study of Chang 7 Formation in the Southern Ordos Basin, China. Energies 2024, 17, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Jia, C.; Pang, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, C.; Ma, X.; Qi, Z.; Chen, J.; Pang, H.; Hu, T.; et al. Accumulation characteristics and geological model for natural gas enrichment in Upper Paleozoic total petroleum system, Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bai, Y.; Sun, K. Characteristics of nitrogen compounds and petroleum charging in crude oil of Zhidan Oilfield, Ordos Basin. Mar. Geol. Front. 2020, 36, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xiong, C. Diagenesis and reservoir quality of deep-lacustrine sandy-debris-flow tight sandstones in Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, China: Implications for reservoir heterogeneity and hydrocarbon accumulation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 202, 108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Feng, C.; Li, Y. Characteristics and Paleoenvironment of High-Quality Shale in the Triassic Yanchang Formation, Southern Margin of the Ordos Basin. Minerals 2023, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Cao, S.; Dong, S.; Lyu, W.; Zeng, L. Control of lamination on bedding-parallel fractures in tight sandstone reservoirs: The seventh member of the upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1428316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T. Main Controlling Factors and Distribution Patterns of Jurassic Reservoirs in Longdong Area, Ordos Basin. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an Shiyou University, Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Tan, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J. Different influence of diagenesis on micro pore-throat characteristics of tight sandstone reservoirs: Case study of the Triassic Chang 7 member in Jiyuan and Zhenbei areas, Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2021, 32, 826–835. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzyna, J.A.; Krakowska-Madejska, P.I.; Puskarczyk, E.; Wawrzyniak-Guz, K. Petrophysical characteristics of Silurian and Ordovician shale gas formations in the Baltic Basin (Northern Poland). Baltica 2022, 35, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniego, F.J.; Martín, M.A.; José, F.S. Singularity features of pore-size soil distribution: Singularity strength analysis and entropy spectrum. Fractals 2001, 9, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, T.C.; Jensen, M.H.; Kadanoff, L.P.; Procaccia, I.; Shraiman, B.I. Fractal measures and their singularities: The characterization of strange sets. Phys. Rev. A 1986, 33, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Bo, J.; Pei, S.; Wang, J. Matrix compression and multifractal characterization for tectonically deformed coals by Hg porosimetry. Fuel 2018, 211, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, A.; Jensen, R.V. Direct determination of the f(α) singularity spectrum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989, 62, 1327–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, M.; Liu, X.; Jin, Z.; Lai, J. The heterogeneity of pore structure in lacustrine shales: Insights from multifractal analysis using N2 adsorption and mercury intrusion. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 114, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Jiao, K.; Deng, B.; Hao, W.; Liu, S. Pore characteristics and preservation mechanism of over-6000-m ultra-deep shale reservoir in the Sichuan Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1059869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedi, R.H.; Crouse, M.S.; Ribeiro, V.J.; Baraniuk, R. A Multifractal Wavelet Model With Application to Network Traffic. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1999, 45, 992–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Jose Martinez, F.; Martin, M.A.; Caniego, F.J.; Tuller, M.; Guber, A.; Pachepsky, Y.; García-Gutiérrez, C. Multifractal analysis of discretized X-ray CT images for the characterization of soil macropore structures. Geoderma 2010, 156, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. Petroleum Geochemistry; Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Dong, D.; Li, X.; Guan, Q.Z. Evaluation of the Wufeng-Longmaxi shale brittleness and prediction of “sweet spot layers” in the Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2016, 36, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Jiang, F.; Hu, T.; Awan, R.S.; Chen, Z.; Lv, J.; Zhang, C.; Hu, M.; Huang, R.; et al. Occurrence Space and State of Petroleum in Lacustrine Shale: Insights from Two-Step Pyrolysis and the N2 Adsorption Experiment. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 10920–10933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Hou, H.; Zhao, M.; Yang, W. Characteristics of diagenetic facies in mixed sedimentary shale oil reservoirs and their significance for reservoir formation: A case study of Lucaogou Formation in Jimsar Sag. China Pet. Explor. 2024, 29, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, J. Dynamic Variation of Full-Scale Pore Compressibility and Heterogeneity in Deep Shale Gas Reservoirs: Implications for Pore System Preservation. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 3880–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Ma, R.; Duan, H. Diagenesis of shale and its control on pore structure, a case study from typical marine, transitional and continental shales. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 15, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, G.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y. Matrix Compression and Pore Heterogeneity in the Coal-Measure Shale Reservoirs of the Qinshui Basin: A Multifractal Analysis. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organic Matter Type | Sample | ω(TOC)/% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium Organic-Rich | 5–109 | 3.17 | 446 | 1.51 | 6.82 | 214.93 |

| 5–60 | 4.01 | 445 | 2.54 | 9.84 | 245.50 | |

| 4–12 | 4.10 | 444 | 2.82 | 11.03 | 268.84 | |

| Highly Organic-Rich | 9–10 | 6.44 | 453 | 1.98 | 20.80 | 323.21 |

| 10–8 | 6.95 | 450 | 2.40 | 22.66 | 326.22 | |

| 11–9 | 7.10 | 457 | 3.06 | 17.27 | 243.27 | |

| 9–14 | 9.80 | 453 | 2.17 | 18.02 | 183.97 | |

| 11–59 | 10.11 | 454 | 3.81 | 31.64 | 313.09 | |

| 11–123 | 10.78 | 454 | 3.68 | 31.77 | 294.84 | |

| 7–17 | 12.24 | 456 | 4.38 | 36.49 | 298.13 |

| Organic Matter Type | Sample | Sat./% | Aro./% | Res./% | Asp./% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium Organic-Rich | 5–109 | 3.47 | 51.89 | 18.19 | 17.10 | 12.82 |

| 5–60 | 5.54 | 61.66 | 16.48 | 13.55 | 8.31 | |

| 4–12 | 6.12 | 71.55 | 17.51 | 4.90 | 6.04 | |

| Highly Organic-Rich | 9–10 | 5.39 | 27.51 | 19.38 | 35.84 | 17.27 |

| 10–8 | 4.12 | 25.34 | 1.21 | 55.44 | 18.01 | |

| 11–9 | 4.86 | 41.76 | 19.98 | 27.90 | 10.35 | |

| 9–14 | 5.11 | 22.97 | 17.93 | 38.02 | 21.09 | |

| 11–59 | 7.61 | 42.13 | 20.17 | 30.63 | 7.07 | |

| 11–123 | 5.80 | 39.30 | 22.75 | 27.20 | 10.75 | |

| 7–17 | 7.55 | 24.76 | 22.73 | 25.70 | 26.81 |

| Organic Matter Type | Sample | Quartz | K-Feldspar | Plagioclase | Calcite | Ankerite | Siderite | Pyrite | Clay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium Organic-Rich | 5–109 | 35.4 | 2.8 | 10.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 40 |

| 5–60 | 37.9 | 2.3 | 9.9 | 0 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 5 | 40.2 | |

| 4–12 | 33.9 | 2.1 | 10 | 1.4 | 1 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 43.3 | |

| Highly Organic-Rich | 9–10 | 33.3 | 10.3 | 7 | 2.8 | 2 | 0 | 13.5 | 31.1 |

| 10–8 | 37 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 11.3 | 38.3 | |

| 11–9 | 52.6 | 1 | 5.4 | 0 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 6.5 | 28.8 | |

| 9–14 | 34.8 | 0 | 13.7 | 0 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 11.4 | 33.9 | |

| 11–59 | 38.2 | 2.9 | 10.8 | 0 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 8.1 | 36.9 | |

| 11–123 | 33.5 | 3.1 | 12 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 13.3 | 37 | |

| 7–17 | 26.5 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 25.6 | 32.3 |

| Organic Matter Type | Sample | Non-Extracted | Extracted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /g | /g | APD nm | /g | /g | APD nm | ||

| Medium Organic-Rich | 5–109 | 1.25 | 0.0035 | 10.94 | 1.94 | 0.0061 | 13.32 |

| 5–60 | 1.94 | 0.0048 | 9.55 | 2.26 | 0.0054 | 10.82 | |

| 4–12 | 1.47 | 0.0052 | 13.94 | 3.81 | 0.0091 | 10.74 | |

| Highly Organic-Rich | 9–10 | 1.13 | 0.0018 | 7.17 | 3.09 | 0.0042 | 6.79 |

| 10–8 | 1.11 | 0.0018 | 6.96 | 1.35 | 0.0023 | 7.99 | |

| 11–9 | 1.94 | 0.0029 | 6.81 | 5.57 | 0.0075 | 6.26 | |

| 9–14 | 1.24 | 0.0020 | 7.30 | 2.44 | 0.0032 | 6.88 | |

| 11–59 | 1.06 | 0.0027 | 11.40 | 3.83 | 0.0053 | 6.90 | |

| 11–123 | 0.83 | 0.0019 | 10.53 | 1.54 | 0.0035 | 11.40 | |

| 7–17 | 1.09 | 0.0017 | 7.21 | 1.84 | 0.0025 | 7.18 |

| Organic Matter Type | Sample | Hurst | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium Organic-Rich | 5–109 | 1.000 | 0.850 | 0.150 | 0.685 | 1.184 | 0.449 | 0.843 | 1.106 | 1.258 | 0.404 | 0.854 | 0.550 |

| 5–60 | 1.000 | 0.863 | 0.137 | 0.714 | 1.289 | 0.483 | 0.857 | 1.097 | 1.405 | 0.435 | 0.970 | 0.354 | |

| 4–12 | 1.000 | 0.818 | 0.182 | 0.631 | 1.212 | 0.404 | 0.816 | 1.123 | 1.304 | 0.364 | 0.940 | 0.579 | |

| Highly Organic-Rich | 9–10 | 1.000 | 0.886 | 0.114 | 0.756 | 1.191 | 0.514 | 0.878 | 1.089 | 1.266 | 0.463 | 0.803 | 0.450 |

| 10–8 | 1.000 | 0.892 | 0.108 | 0.770 | 1.186 | 0.529 | 0.885 | 1.084 | 1.258 | 0.476 | 0.782 | 0.434 | |

| 11–9 | 1.000 | 0.898 | 0.102 | 0.783 | 1.219 | 0.552 | 0.891 | 1.079 | 1.315 | 0.498 | 0.817 | 0.346 | |

| 9–14 | 1.000 | 0.887 | 0.113 | 0.759 | 1.180 | 0.518 | 0.879 | 1.088 | 1.246 | 0.466 | 0.780 | 0.463 | |

| 11–59 | 1.000 | 0.862 | 0.138 | 0.705 | 1.225 | 0.465 | 0.853 | 1.099 | 1.324 | 0.418 | 0.905 | 0.456 | |

| 11–123 | 1.000 | 0.869 | 0.131 | 0.720 | 1.216 | 0.478 | 0.860 | 1.095 | 1.311 | 0.430 | 0.881 | 0.449 | |

| 7–17 | 1.000 | 0.889 | 0.111 | 0.762 | 1.197 | 0.522 | 0.881 | 1.086 | 1.278 | 0.470 | 0.808 | 0.424 |

| Organic Matter Type | Sample | Hurst | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium Organic-Rich | 5–109 | 1.000 | 0.853 | 0.147 | 0.690 | 1.190 | 0.452 | 0.845 | 1.103 | 1.269 | 0.407 | 0.862 | 0.531 |

| 5–60 | 1.000 | 0.866 | 0.134 | 0.717 | 1.229 | 0.480 | 0.859 | 1.097 | 1.332 | 0.432 | 0.900 | 0.431 | |

| 4–12 | 1.000 | 0.863 | 0.137 | 0.711 | 1.192 | 0.473 | 0.856 | 1.099 | 1.272 | 0.426 | 0.846 | 0.500 | |

| Highly Organic-Rich | 9–10 | 1.000 | 0.899 | 0.101 | 0.785 | 1.214 | 0.552 | 0.893 | 1.080 | 1.309 | 0.497 | 0.811 | 0.353 |

| 10–8 | 1.000 | 0.885 | 0.115 | 0.755 | 1.187 | 0.515 | 0.878 | 1.088 | 1.261 | 0.464 | 0.797 | 0.451 | |

| 11–9 | 1.000 | 0.909 | 0.091 | 0.808 | 1.175 | 0.578 | 0.904 | 1.075 | 1.237 | 0.521 | 0.716 | 0.392 | |

| 9–14 | 1.000 | 0.899 | 0.101 | 0.785 | 1.199 | 0.552 | 0.893 | 1.079 | 1.285 | 0.497 | 0.787 | 0.376 | |

| 11–59 | 1.000 | 0.901 | 0.099 | 0.787 | 1.229 | 0.553 | 0.893 | 1.078 | 1.332 | 0.498 | 0.834 | 0.327 | |

| 11–123 | 1.000 | 0.877 | 0.123 | 0.736 | 1.257 | 0.495 | 0.868 | 1.091 | 1.368 | 0.446 | 0.923 | 0.368 | |

| 7–17 | 1.000 | 0.896 | 0.104 | 0.779 | 1.215 | 0.544 | 0.889 | 1.082 | 1.311 | 0.490 | 0.821 | 0.363 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Z.; Xin, H.; Wang, Z.; Feng, S.; Ma, W.; Zhu, L.; Tao, H.; Hao, L.; Ma, X. Pore Structure and the Multifractal Characteristics of Shale Before and After Extraction: A Case Study of the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121324

Xu Z, Xin H, Wang Z, Feng S, Ma W, Zhu L, Tao H, Hao L, Ma X. Pore Structure and the Multifractal Characteristics of Shale Before and After Extraction: A Case Study of the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121324

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Zhengwei, Honggang Xin, Zhitao Wang, Shengbin Feng, Wenzhong Ma, Liwen Zhu, Huifei Tao, Lewei Hao, and Xiaofeng Ma. 2025. "Pore Structure and the Multifractal Characteristics of Shale Before and After Extraction: A Case Study of the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121324

APA StyleXu, Z., Xin, H., Wang, Z., Feng, S., Ma, W., Zhu, L., Tao, H., Hao, L., & Ma, X. (2025). Pore Structure and the Multifractal Characteristics of Shale Before and After Extraction: A Case Study of the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin. Minerals, 15(12), 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121324