4.2. Data Preprocessing

In order to ensure comparability among different datasets and to address differences in magnitude and units, data standardization was performed prior to factor analysis to eliminate discrepancies caused by scale and unit variations. This study uses the Z-score standardization method to process the data of 32 elements and subject them to factor analysis [

60]. The extraction method employed was Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and the rotation method used was the Kaiser normalized varimax rotation. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.872, indicating a strong correlation among variables. Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a significance value (Sig) less than 0.01, confirming the suitability of the selected elements for factor analysis. The detailed results are presented in

Table 1. The variance percentages and cumulative variance of the correlation coefficient matrix were calculated (

Table 2). The “% of variance” marked in the figure is clearly defined as “percentage of variance”, which indicates the explanatory power of each factor to the total variance of variables. A higher value indicates that the factor is more important for data variability. The “%” in “Cumulative %” denotes a unit. The first seven common factors collectively explained 67.167% of the total variance, suggesting that these seven factors represent the majority of the information contained in the original data. Factor loadings greater than 0.4 were selected and listed (

Table 3). Factor F1 includes eight elements—Li, Bi, W, B, Th, As, F, and Pb—which are commonly associated with hydrothermal mineralization processes. Factor F2 comprises seven elements—Ag, Zn, Ni, Cu, U, Mo, and Cd—among which Ag, Zn, and Cd are copper-affinitive elements, while Ni and Mo frequently accompany copper mineralization. Factor F3 consists of Co, Ti, Cr, V, and Mn, which are iron-affinitive elements predominantly found in mafic and ultramafic rocks, representing iron mineralization.

Since factor analysis primarily reflects the statistical characteristics of the data and is insufficient in representing the spatial distribution of the data, it is necessary to perform MIDW interpolation analysis. Using the GeoDAS 4.0 software [

34], MIDW interpolation was applied to the F2 factor scores and the Cu element concentrations (

Figure 2). The resulting interpolation maps show similar high-value areas, mainly distributed across four stratigraphic units: the Cryogenian System (Cri), Cambrian (Є), Silurian(S), and Ordovician(O) strata. Compared to the high anomaly zones in the F2 factor score interpolation map, the high anomaly zones in the Cu element MIDW interpolation map more closely correspond to the Yaolinghe Group of the Cryogenian System. Meanwhile, the F2 factor score interpolation map emphasizes anomalies in the eastern part of the study area.

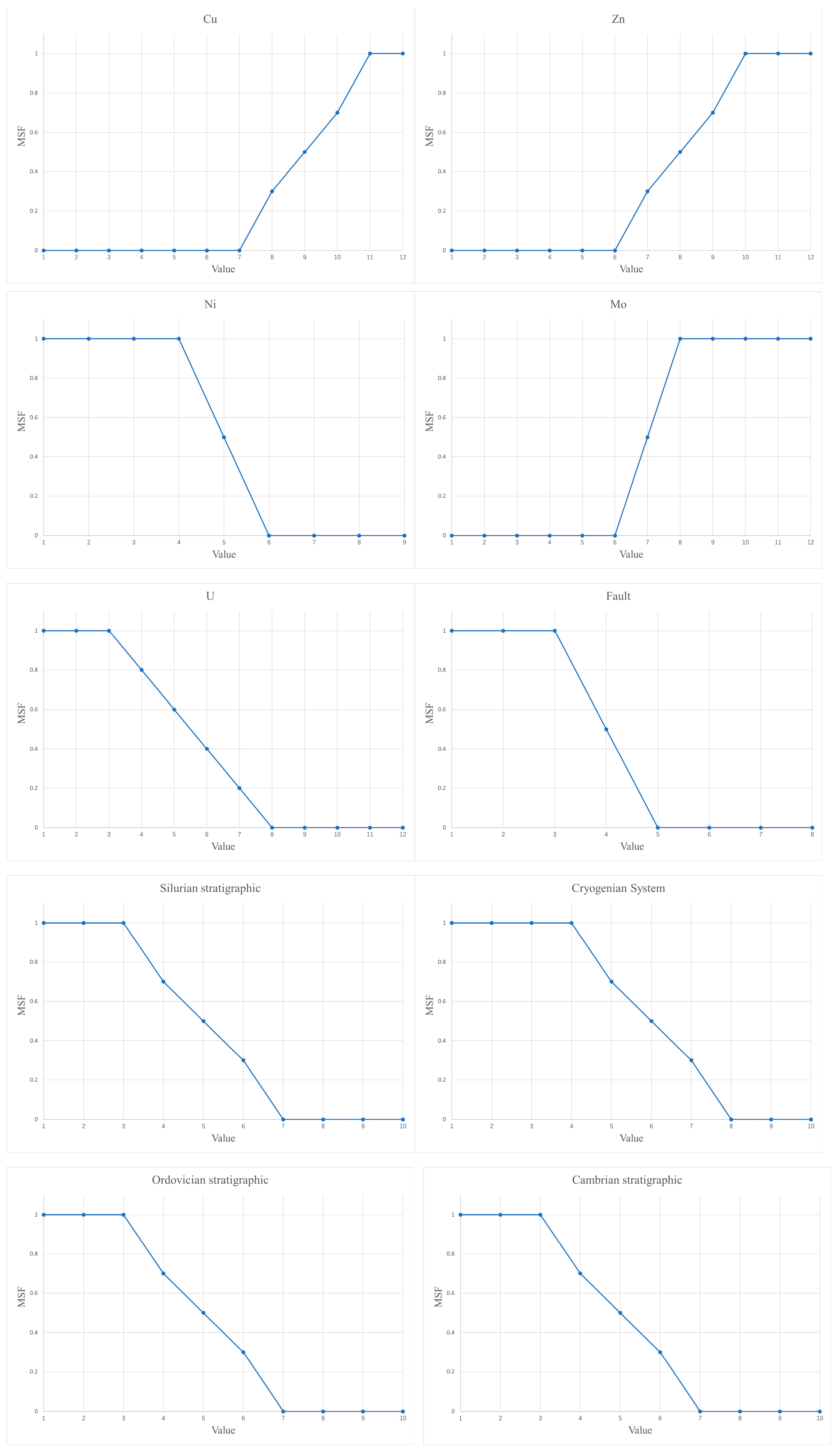

After performing C-A fractal analysis on the IDW interpolation maps of F2 factor scores and Cu element concentrations, the cutoff points were obtained to distinguish between background areas and anomalous areas (

Figure 3). The blue line is a segmented line that divides the data into three parts, and the red line is a linear fitting line for the data of different segments. The blue dots represent logA(

ρ) (logarithm of the area of anomalies with concentration exceeding the threshold

ρ vs. logarithm of

ρ). The anomaly zones were classified into weak, moderate, and strong anomaly regions (

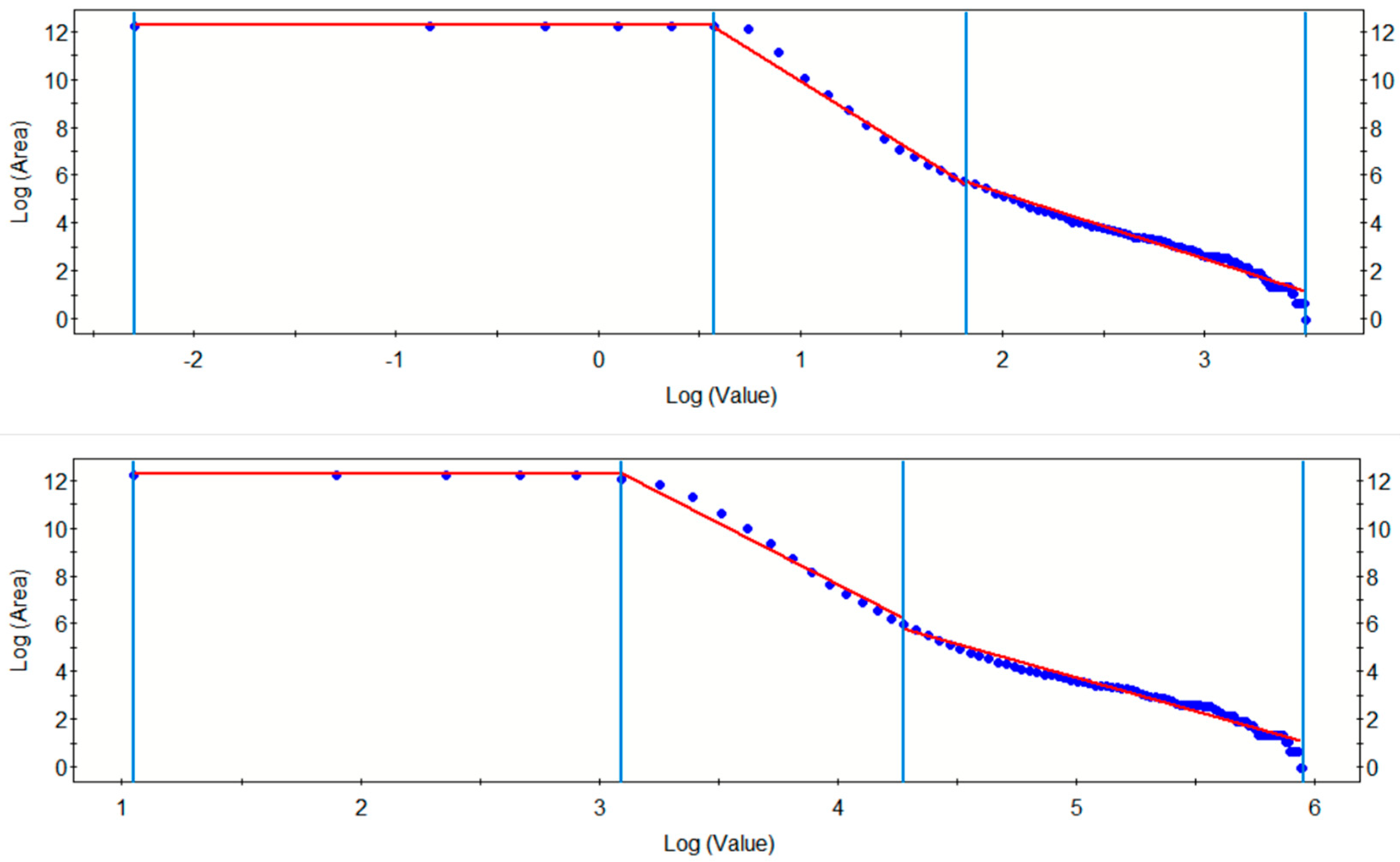

Figure 4). From the figures, it can be observed that the majority of the area in the F2 factor score map corresponds to weak anomalies after C-A analysis, with the moderate and strong anomaly zones being too limited in extent to serve as reliable indicators for mineral exploration. For the Cu element map, there are 21 known mineral deposits located within the moderate anomaly zones; however, the moderate anomaly area is excessively large, making it difficult to pinpoint potential unknown deposits. Therefore, the Cu element data were further processed by filtering out outliers beyond the range of mean ± 3 standard deviations, followed by generating a new IDW interpolation map and subsequent C-A fractal analysis (

Figure 5). Although the anomaly zones became more constrained after this processing, the number of known mineral deposits within the moderate anomaly zone decreased to 14. These results highlight the limitations of raw geochemical data in distinguishing mineralized anomalies from background enrichment. The complex distribution of Cu anomalies suggests that a comprehensive analysis integrating geological settings (e.g., structures, stratigraphy, magmatism) is essential to constrain ore-forming processes and prospecting targets.

In the northwestern region of Hubei Province, the spatial distribution of copper de-posits is closely associated with fault zones, predominantly exhibiting linear belts along northwest- and northeast-trending faults. Studies indicate that the primary ore-bearing stratigraphic units hosting copper mineralization in this area include the Cryogenian, Ordovician, Cambrian, and Silurian systems. Furthermore, factor analysis has revealed a significant correlation between copper mineralization and elements such as Ag, Zn, Ni, Cu, U, Mo, and Cd. Therefore, this paper uses the MIDW method to interpolate these elements, obtaining their raster maps as evidence layers for FWofE (

Figure 6a–g). Based on these characteristics and the spatial relationships among mineral deposits, stratigraphy, and faults, evidence layers can be generated by constructing multi-ring buffer zones around these geological features. Multi-ring buffer zone refers to a series of concentric rings set around key geological features (e.g., faults, ore-bearing strata) to quantify the spatial correlation distance between geological features and mineralization, thereby effectively extracting mineralization-related information. These layers serve as critical inputs for building FWofE models to support mineralization prediction.

Geological features exhibit significant correlations with mineralization processes within certain spatial extents, which holds important guiding significance for exploration and prospecting. Therefore, to effectively extract mineralization-related information, it is necessary to extend geological elements by appropriate distances to construct evidence layers [

61]. Based on this principle, this study designed a multi-ring buffer zone consisting of 10 concentric rings with an interval of 0.5 km each (

Figure 6h–l). Statistical analysis shows that this buffer zone encompasses, on average, 85% of the known mineral deposits, while only a very small number of deposits lie outside the buffer range. Consequently, the selected buffer distance and the number of rings can be considered optimal parameters.

To ensure that the geological evidence layers using distance-based buffers are not overly dependent on subjective parameter choices, a small-range perturbation sensitivity analysis was conducted. Following the buffer-distance framework proposed by Zhang et al. [

14], which closely matches our study area in scale and sampling density, a baseline distance of 5 km was adopted. We then assessed the robustness of this choice by comparing the C and t statistics derived from buffer distances of 4000 m, 5000 m, and 6000 m (

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3,

Table A4 and

Table A5) [

62].

The comparison reveals distinct spatial association patterns that correspond to the geometries observed in the evidence maps. For the regional fault evidence layer (

Figure 6h and

Table A1): As shown in

Figure 6h, the faults form a complex network of structural corridors. Statistically, the contrast values diminish with distance, yet the layer maintains a positive association up to 5000 m (C = 0.05). This 5000 m threshold marks the effective spatial limit of the structural damage zone and fluid migration influence. Beyond this range (at 6000 m), the buffer extends excessively into non-mineralized background areas, causing the correlation to turn negative (C = −0.03), indicating the introduction of regional noise. For the Silurian (

Figure 6i) and Cryogenian (

Figure 6j) stratigraphic layers: These layers represent the primary ore-hosting horizons (

Table A2 and

Table 3). While the 4000 m buffer yields the highest raw contrast values due to its tight fit to the outcrop boundaries, the 5000 m buffer retains significant positive associations (e.g., Cryogenian t = 1.54). Visually,

Figure 6j shows that the Cryogenian strata are spatially extensive but fragmented; the 5000 m buffer helps bridge the gaps between proximal ore-hosting bodies, accounting for subsurface extensions and geological mapping uncertainties without being overly restricted to fragmented outcrop geometries. For the Ordovician (

Figure 6k) and Cambrian (

Figure 6l) stratigraphic layers: These act as inhibitory factors. Notably, the Cambrian stratigraphic evidence layer (

Figure 6l) displays a stronger negative correlation at 5000 m (C = −0.32) compared to 4000 m (C = −0.22) (

Table A5). As seen in

Figure 6l, the Cambrian strata form continuous belts that are spatially distinct from known deposits. The wider 5000 m buffer effectively delineates a broader “unfavorable domain,” enhancing the model’s ability to identify unfavorable areas.

Overall, while the 4000 m buffer yields higher contrast values for favorable factors, it risks underestimating the broader spatial influence of negative controls (e.g., Cambrian) and may create fragmented potential zones. The 6000 m buffer clearly introduces considerable regional noise, evidenced by the reversed correlation in faults. Consequently, the 5000 m buffer was selected as the optimal parameter. It provides a robust compromise that captures the maximum effective range of positive structural controls (Faults) while maximizing the identification of unfavorable lithological zones (Cambrian), offering a geologically meaningful representation of the regional metallogenic framework.

Dependence diagnostics for the evidential layers were evaluated using the pairwise Pearson correlation matrix (

Table 4). The results show that most correlations fall within the range of −0.30 to 0.35, indicating weak to moderate linear dependence among lithological, structural, and geochemical variables. A few stronger correlations appear among the interpolated geochemical layers (e.g., Cd–Mo, Cd–Cu, and Cu–Ni, with coefficients between 0.60 and 0.79), which is expected because these elements share similar geochemical behavior and partly overlapping mineralization processes. Such moderate correlations are commonly considered acceptable within the framework of the FWofE model, since the method requires conditional independence rather than absolute independence of evidential layers. Therefore, the dependence structure observed in our dataset does not materially violate the conditional-independence assumption of the FWofE model, and the chosen evidential layers can be integrated into the model without producing substantial bias in posterior favourability estimates.

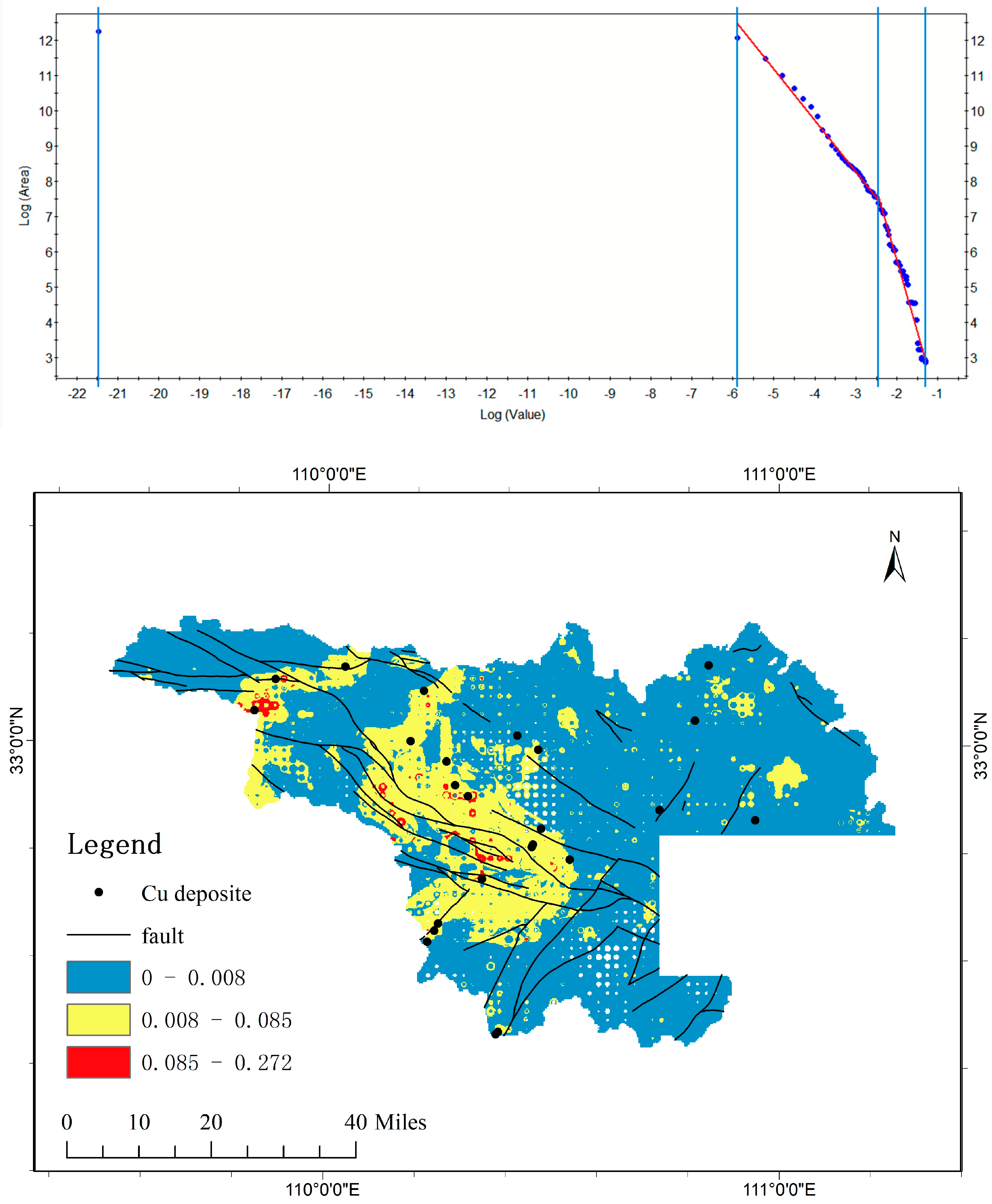

After processing through the above steps, a total of twelve evidence layers were generated (

Figure 6), and the MSF values and parameters for each evidence layer are presented in

Figure A1 and

Table A6. All of them were used to construct the FWofE model.

4.3. Fuzzy Weights-of-Evidence Model

The most critical aspect in constructing a FWofE model is the selection of appropriate evidence layers, which must be closely related to the physicochemical conditions of mineralization. Considering the geological background of northwestern Hubei, the primary ore-hosting stratigraphic units for copper mineralization and regional fault structures were selected as key evidence layers. These geological features exhibit strong spatial associations with the distribution and metallogenic potential of copper deposits, thereby enhancing the model’s capacity to accurately assess the distribution and prospectivity of mineral resources. In addition, geochemical anomalies derived from fluvial sediment data were analyzed to identify elemental patterns associated with copper mineralization. Such geochemical anomalies often serve as indicators of potential mineralized zones. Therefore, incorporating these anomalies as geochemical evidence layers further improves the precision and reliability of the mineral potential assessment [

63].

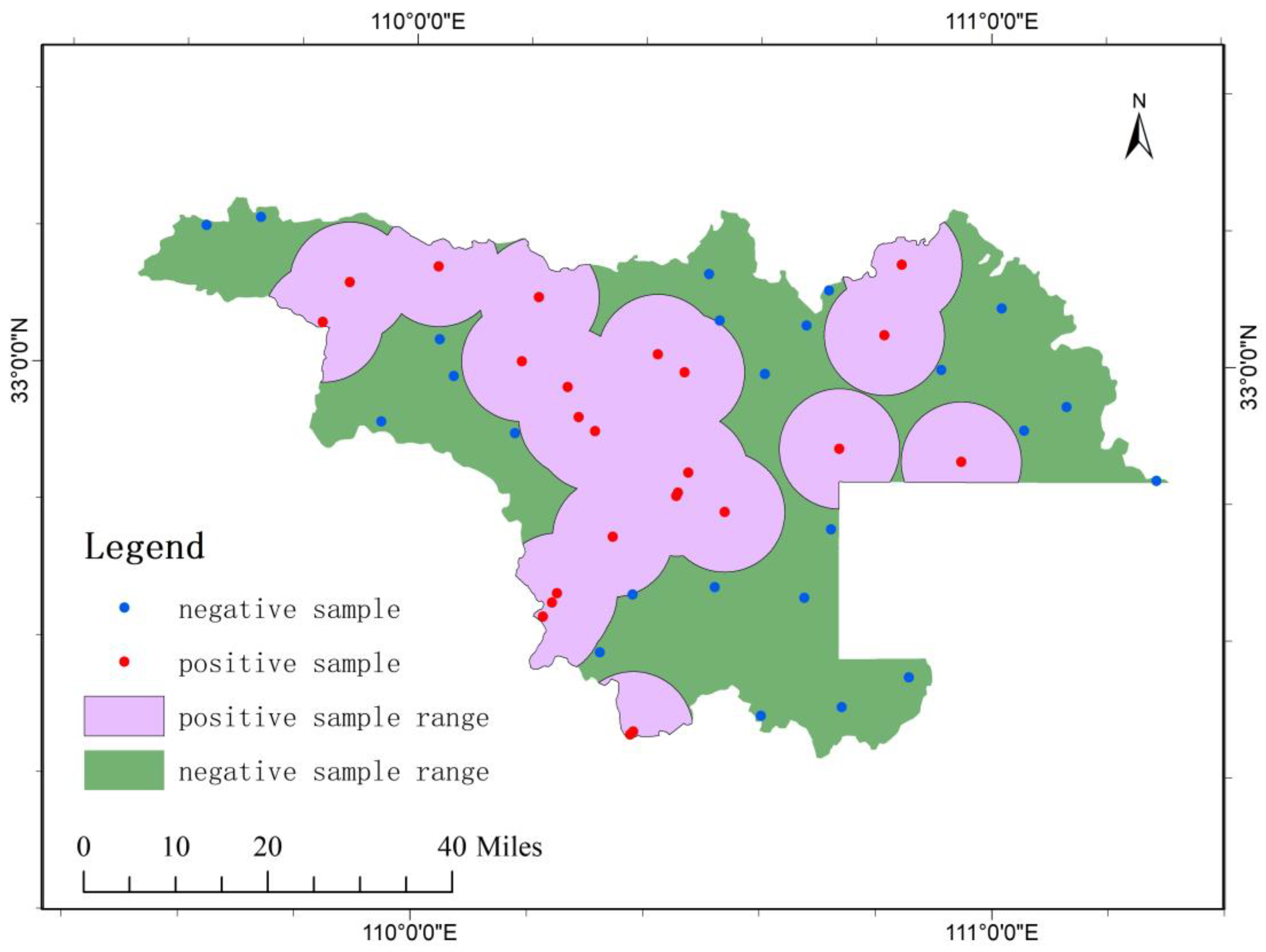

Before constructing the model, it is necessary to define the training and prediction areas in the GeoDAS4.0 software. In most cases, the training area is set to be the same as the prediction area. When delineating the training area, it is important to ensure that the number of grid cells is roughly equivalent to the number of known mineral occurrences. In this study, the spatial unit size of the study area was set to 1,000,000 map units. A total of 24 known copper deposits were selected as the training point layer, and the corresponding number of spatial units was 23.1. This yields a prior probability of 2.91% for the training dataset.

After setting the training parameters, the FWofE for each of the aforementioned evidence layers were calculated. The conventional WofE method determines a binary threshold for each evidence layer based on the maximum value of the ratio t = C/S(C), where C is the contrast (i.e., the difference between positive and negative weights), and S(C) is the standard deviation of the contrast. Areas favorable for mineralization are assigned a value of 1, while unfavorable areas are assigned 0 [

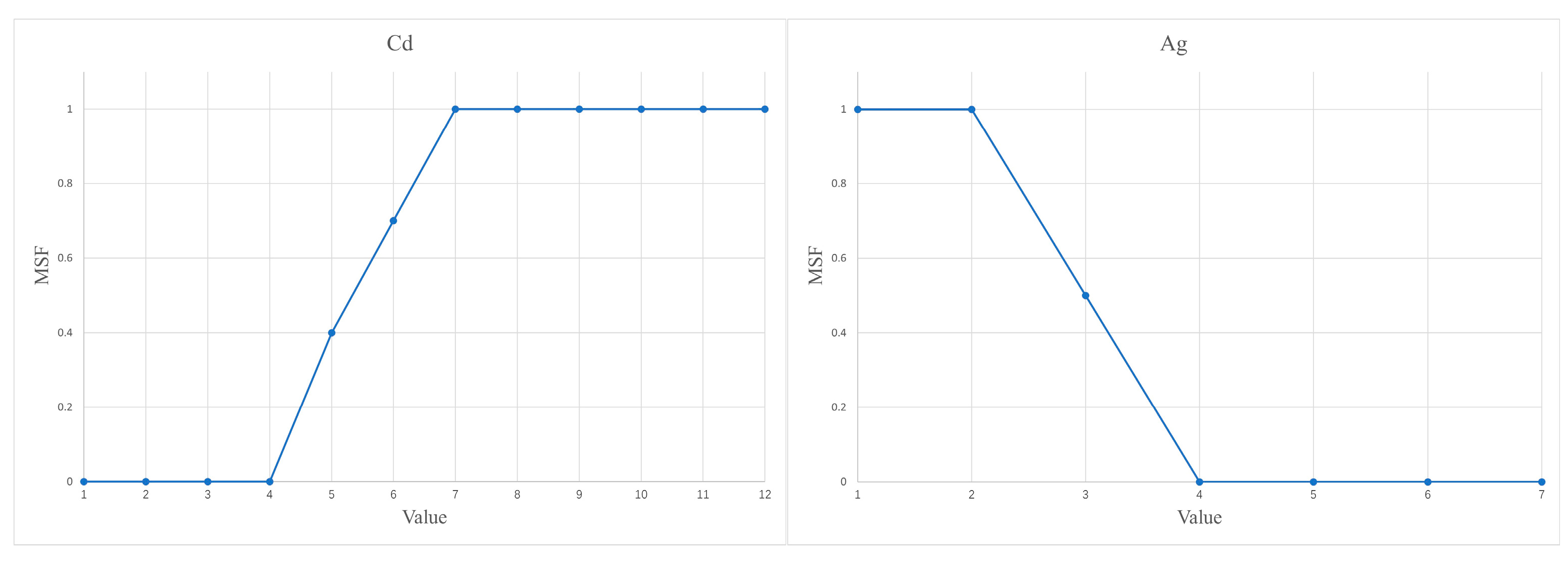

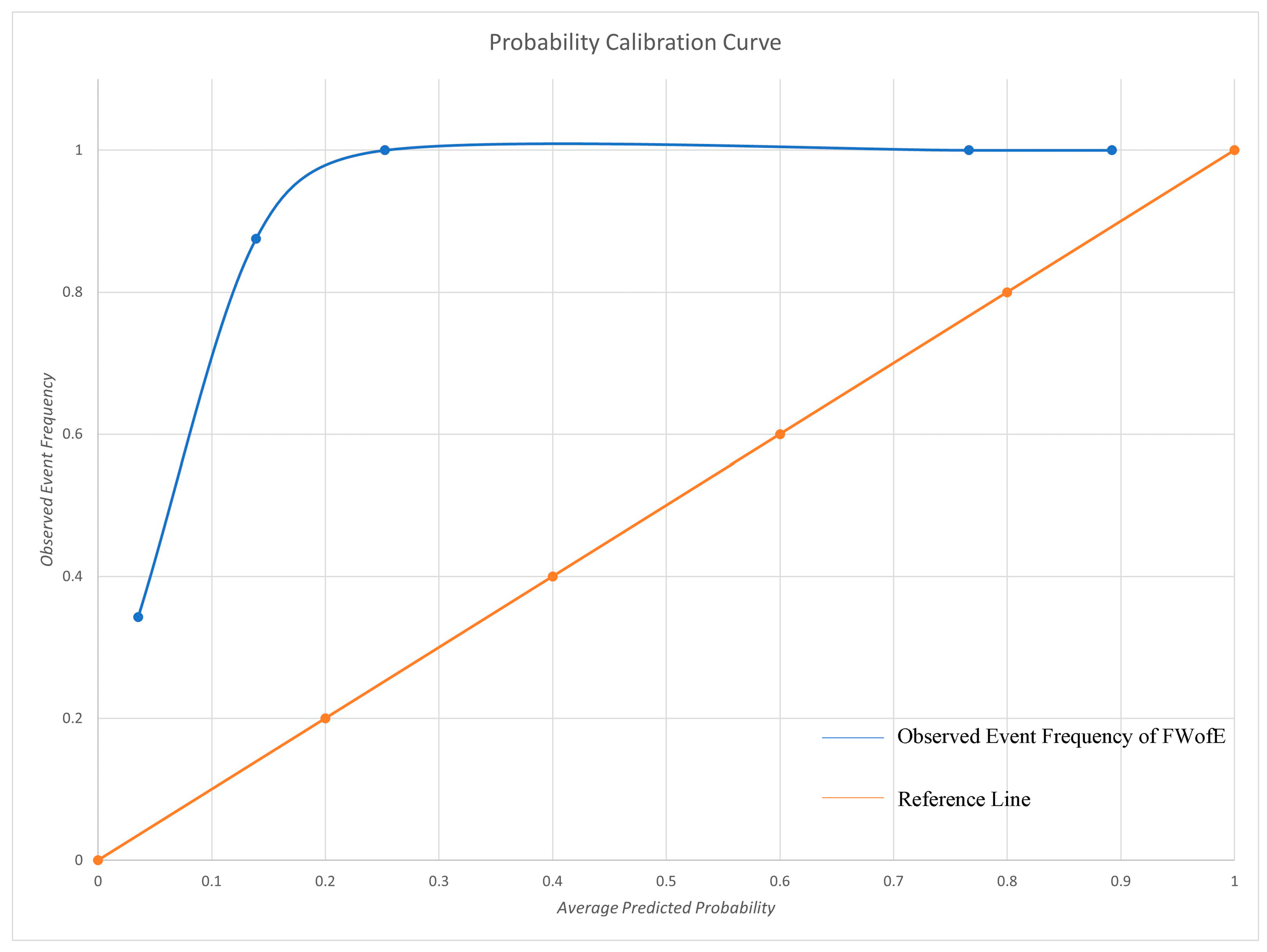

64]. In contrast, the FWofE model applies a Membership Standardization Function (MSF) to reclassify the evidence layers. The MSF assigns continuous values within the range [0, 1], reflecting the degree of favorability for mineralization based on the corresponding t-values (

Figure 7) [

53]. This fuzzy approach allows for a more nuanced representation of mineral potential by incorporating gradational rather than binary classification.

When calculating FWofE using the GeoDAS4.0 software, the data must be arranged in either cumulative (ascending) or cumulative (descending) order. When cumulative (ascending) order is selected, the first local maximum point from left to right and all points to its left are assigned a value of 1 (

Figure 7, U, red), representing an increasing likelihood of mineralization. The relatively high-value points to the right of this maximum are set as fuzzy points and assigned values within the range (0, 1) in sequence (

Figure 7, U, yellow), while the remaining points are assigned a value of 0 (

Figure 7, U, blue). When cumulative (descending) order is selected, the data are viewed from right to left. The first local maximum point and all points to its right are assigned a value of 1 (

Figure 7, Cu, red), the relatively high-value points to the left of this maximum are set as fuzzy points and given values within the range (0, 1) in sequence (

Figure 7, Cu, yellow), and all other points are assigned a value of 0 (

Figure 7, Cu, blue).