1. Introduction

The increasing demand for energy resources is driving oil and gas exploration into more challenging geological settings, including deepwater offshore fields and formations drilled with high-salinity brines. In such environments, the performance of conventional water-based drilling fluids, which typically rely on bentonite clay as a primary viscosifier, is severely compromised [

1,

2]. Maintaining wellbore stability and operational efficiency in these complex lithologies is a significant challenge for drilling fluid design [

3]. In these brines, where total dissolved solids can easily exceed 50,000 ppm and may approach saturation, high electrolyte concentrations can cause bentonite suspensions to flocculate, leading to a critical loss of rheological control and operational inefficiency. This creates a pressing need for alternative, salt-tolerant viscosifiers that can ensure drilling fluid stability in these demanding conditions. Palygorskite, a naturally occurring fibrous clay, has emerged as a promising candidate to address this technological gap [

4,

5].

Palygorskite is widely known in industrial applications as attapulgite, which is a hydrous magnesium phyllosilicate mineral whose unique crystal structure makes it a material of significant technological importance in high-performance drilling fluids [

6]. First characterized by [

7], its 2:1 structure consists of elongated, prismatic crystals that form a framework of internal channels, imparting a distinctive fibrous morphology, high specific surface area, and significant porosity. This microstructure is the source of its most critical property for industrial fluids which is the ability to form a stable, thixotropic gel through primarily physical particle interactions [

8]. Critically and in sharp contrast to conventional bentonite clays, this rheological behavior is maintained even in extreme chemical environments, such as in high-salinity brine [

9,

10]. While bentonite flocculates and loses its viscosity in the presence of electrolytes, palygorskite’s performance remains robust [

1].

This critical performance difference is rooted in their fundamentally distinct viscosity-building mechanisms. Bentonite, composed of flat platelets, relies on electrostatic repulsion between its negatively charged surfaces to create a stable gel in fresh water. The introduction of salt cations neutralizes these charges, causing the structure to collapse and flocculate [

2]. In stark contrast, palygorskite’s needle-like crystals build viscosity through physical and mechanical entanglement, forming a robust ‘brush-heap’ lattice [

8,

11]. This mechanism is independent of surface chemistry and is therefore immune to the destabilizing effects of electrolytes, making it uniquely suited for high-salinity applications. Due to this salt tolerance, palygorskite is an essential viscosifier for challenging drilling operations, including offshore and deep-well applications [

6]. Its effectiveness ensures the efficient suspension and transport of drill cuttings, while its minimal swellability mitigates operational risks like formation blockage and system overpressure [

12]. Beyond this primary application, it is also a consistent behavior across a wide range of temperatures and electrolytic conditions establishing attapulgite as an exceptionally reliable additive for drilling in demanding geochemical environments [

13]. Beyond these technical merits, the utilization of palygorskite offers compelling local and environmental advantages. As a mineral that occurs naturally in regions like the Mediterranean, including parts of Greece, its local extraction promotes sustainable resource management by reducing the environmental footprint associated with transporting imported raw materials [

14,

15]. This practice can stimulate regional economies through job creation and local value addition, especially when coupled with low-impact processing methods. Furthermore, attapulgite is a natural, non-toxic, and chemically stable material. Its inherent adsorptive properties give it secondary utility in environmental remediation technologies, reinforcing its profile as a responsible industrial mineral with the potential for recycling or reuse in certain applications.

The enhancement of palygorskite’s rheological properties through mechanical and chemical treatments has been a central theme in the literature. Early works established that mechanical processing, such as extrusion, improves the viscosity of attapulgite slurries though this effect is less pronounced in saline water [

6]. It was also found that attapulgite’s inherent viscosity is generally stable in electrolytic environments and can be significantly enhanced by small quantities of inorganic additives, particularly magnesium oxide MgO or magnesium hydroxide Mg(OH)

2, which can increase viscosity up to fivefold [

16]. The role of MgO as a performance enhancer is a recurring topic. In that work [

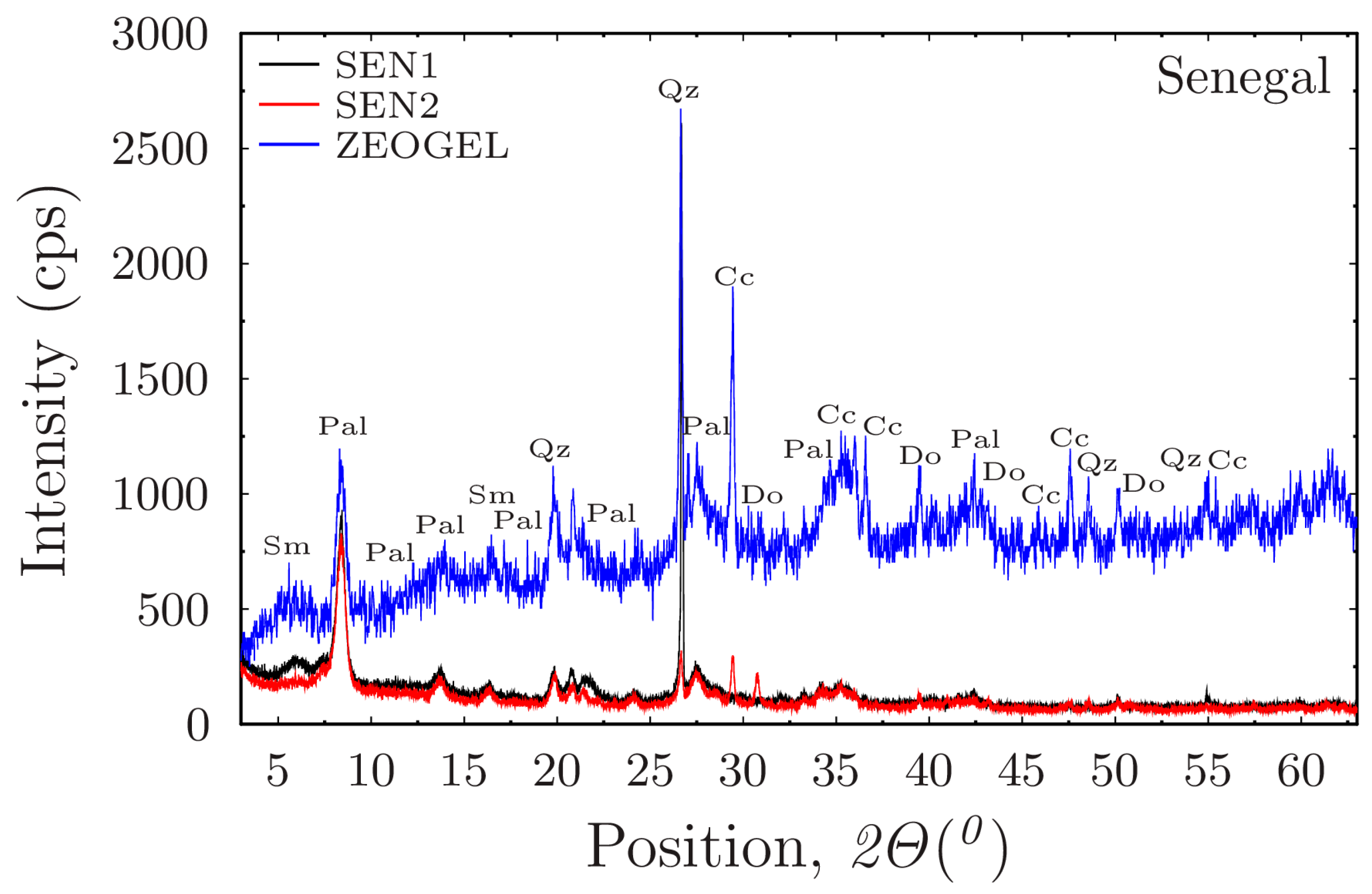

13], its effectiveness in high-salinity fluids was noted, and studies on Senegalese palygorskite confirmed that an optimal MgO concentration (e.g., 2% by weight) maximizes viscosity [

17]. The mechanism is attributed to electrostatic attraction between positively charged MgO particles and the negative surfaces of the clay fibers, which improves the gel structure and yield point of the [

18,

19].

As stated earlier, a key advantage of palygorskite over bentonite (smectite) is its stability in high-salinity environments. Studies on Greek palygorskite-smectite clays in the work of [

9] showed that while electrolytes degrade the rheological properties of smectite-bearing clays, palygorskite-rich clays remain stable, making them highly suitable for saltwater-based drilling fluids. This was further confirmed in a study simulating Persian Gulf seawater, where bentonite suspensions failed but palygorskite maintained acceptable rheology and fluid loss control [

1]. The fundamental pseudoplastic behavior of palygorskite in electrolytic solutions has been linked to the aspect ratio (length-to-width) of its crystals. It was shown that a higher aspect ratio of length the width generally leads to better rheological performance [

8]. Research has also validated that palygorskite from various global sources (e.g., Spain, Mexico, Brazil) can meet American Petroleum Institute (API) specifications for drilling fluids, although performance varies depending on the deposit’s specific mineralogy [

4,

12,

15].

More recent research has focused on advanced processing to unlock palygorskite’s full potential. A significant body of work presented in [

20,

21] demonstrated that high-pressure homogenization, sometimes combined with extrusion or freeze–thaw cycles [

22], is highly effective at deagglomerating palygorskite bundles into individual nanofibers. This process dramatically increases the specific surface area and can boost the apparent viscosity of suspensions by an order of magnitude. This research also explored the influence of different solvents and electrolytes, finding that dispersion in solvents like DMSO improved de-bundling, while specific salts, such as zinc sulfate ZnSO

4 and potassium sulfate K

2SO

4, could optimize surface charge and further enhance suspension stability [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In practical applications, increasing palygorskite concentration reduces filtration loss, a key performance metric for drilling fluids [

27]. The importance of pH control has also been highlighted, with additives like sodium hydroxide NaOH or sodium carbonate Na

2CO

3 being used to improve clay dispersion and rheological stability, particularly for raw palygorskite from sources in Iraq [

5,

28,

29].

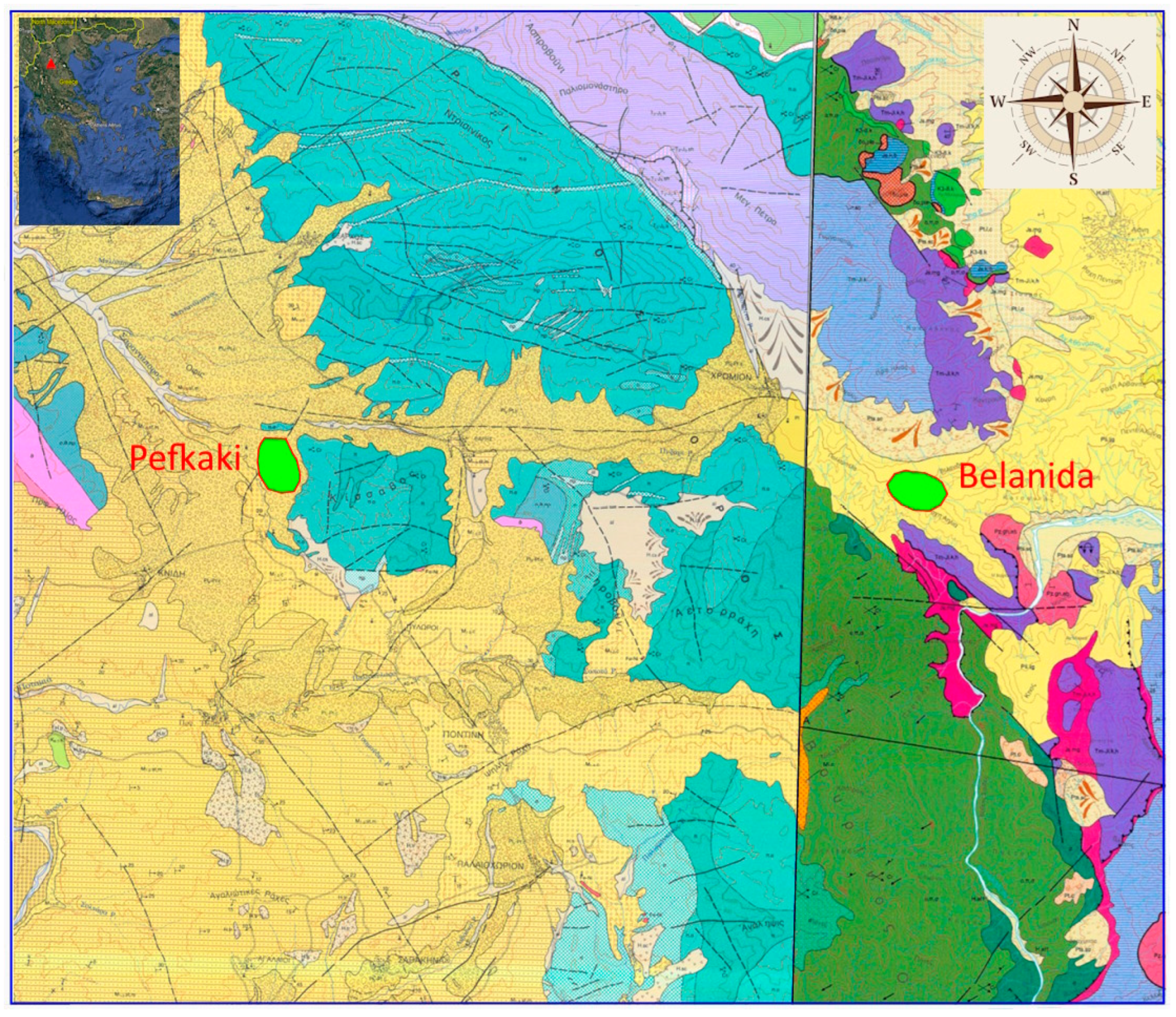

Despite this extensive body of research on palygorskite from various global sources, a comprehensive investigation of the material from the Ventzia basin in Greece is notably absent. While the presence of palygorskite in this region has been documented [

8], its potential for use in drilling fluids following targeted mechanical and chemical activation remains unexplored. Furthermore, few studies have systematically compared the performance of a newly characterized palygorskite source against commercial products under a range of realistic high-hardness saline conditions [

30,

31].

Aligning with the sustainable use of alkali-activated natural resources, this study investigates the use of magnesium oxide (MgO) as an alkaline component to activate a local Greek palygorskite clay. The objective is to formulate a high-performance material for subsurface geotechnical construction, representing a resource-efficient alternative to imported industrial minerals. This drilling fluid functions as a dynamic reinforcement that improves the geomechanical stability of the borehole, thereby fitting the broader theme of using alkali activation to enhance clay-rich materials for engineering applications. The novelty and primary contributions of this work are fourfold. First, it characterizes and validates a technologically unexplored Greek mineral resource, offering a potential sustainable and local alternative to imported materials. Second, it systematically benchmarks the performance of the Greek palygorskite against established commercial products, providing a clear context for its technical viability. Third, the investigation moves beyond standard salinity tests by evaluating the material in a high-hardness brine, assessing its resilience to the destabilizing effects of divalent cations which is a critical but less-studied aspect. Finally, this work provides key insights into the performance trade-offs of natural palygorskite-smectite clays, demonstrating how fluid chemistry can be leveraged to optimize filtration control even when rheological properties are suppressed. These findings offer practical guidance for formulating resilient drilling fluids for challenging geological environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized to present the research in logical progression.

Section 2 outlines the geological context of the raw material.

Section 3 is dedicated to the experimental program, detailing both the characterization of the palygorskite samples and the methods employed for preparing and testing the drilling fluids. In

Section 4, the results are presented and analyzed in detail. Finally,

Section 5 provides a summary of the key findings and the conclusions drawn from this investigation.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

This section presents the analysis of the experimental results, beginning with the fundamental rheological behavior of the fluid suspensions. The experimental flow curve data (shear stress vs. shear rate) for all suspensions were fitted to the three-parameter Herschel–Bulkley (H-B) constitutive model. This model was chosen because it accurately describes the behavior of yield-pseudoplastic fluids, which is characteristic of most drilling muds. Furthermore, the H-B model is a more comprehensive representation than simpler two-parameter models like the Bingham Plastic or Power Law, as it accounts for both the initial yield stress (τ

0) required to initiate flow and the non-linear, shear-thinning behavior of the fluid. The mathematical form of the Herschel–Bulkley model is [

2]:

where τ is the shear stress, τ

0 is the yield stress, K is the consistency index,

is the shear rate, and n is the flow behavior index. The model provided an excellent fit to our experimental data across all tested fluids, with coefficients of determination (R

2) consistently exceeding 0.99, confirming its suitability for this analysis. More details on the curve fitting method we have used can be found in [

50].

Following this, a detailed analysis of the key API rheological parameters is provided, including plastic viscosity, yield point, and the 10 s and 10 min gel strengths, which are critical for assessing the fluid’s carrying capacity and thixotropic properties. The influence of the clays on the fluid’s pH is also presented. Finally, the crucial performance metric of filtration control is evaluated through an analysis of API fluid loss and filter cake thickness. Throughout this section, the performance of the Ventzia basin samples is systematically compared against the commercial ZEOGEL and the Senegal benchmarks across the three different aqueous environments (DW, SW, and HH).

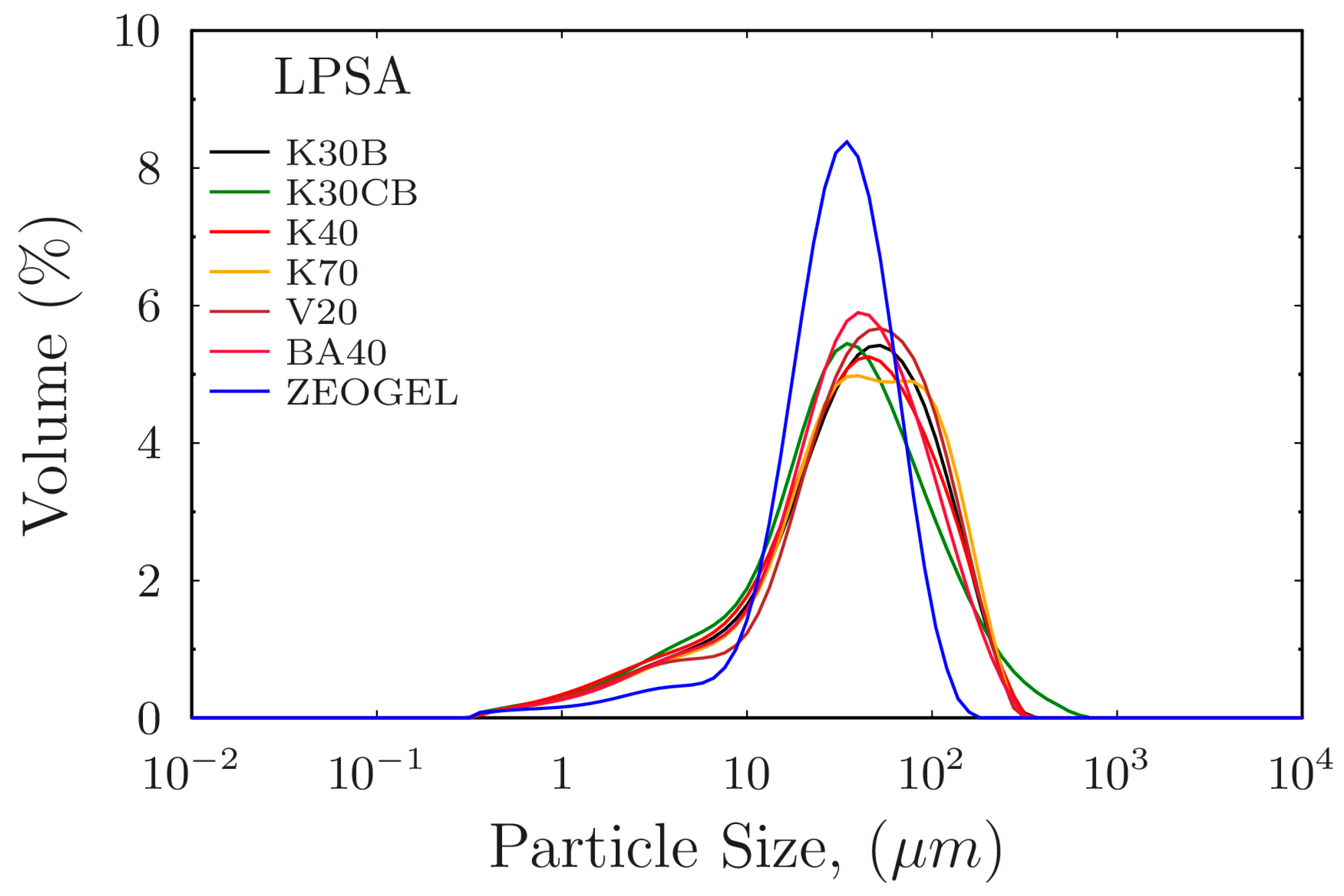

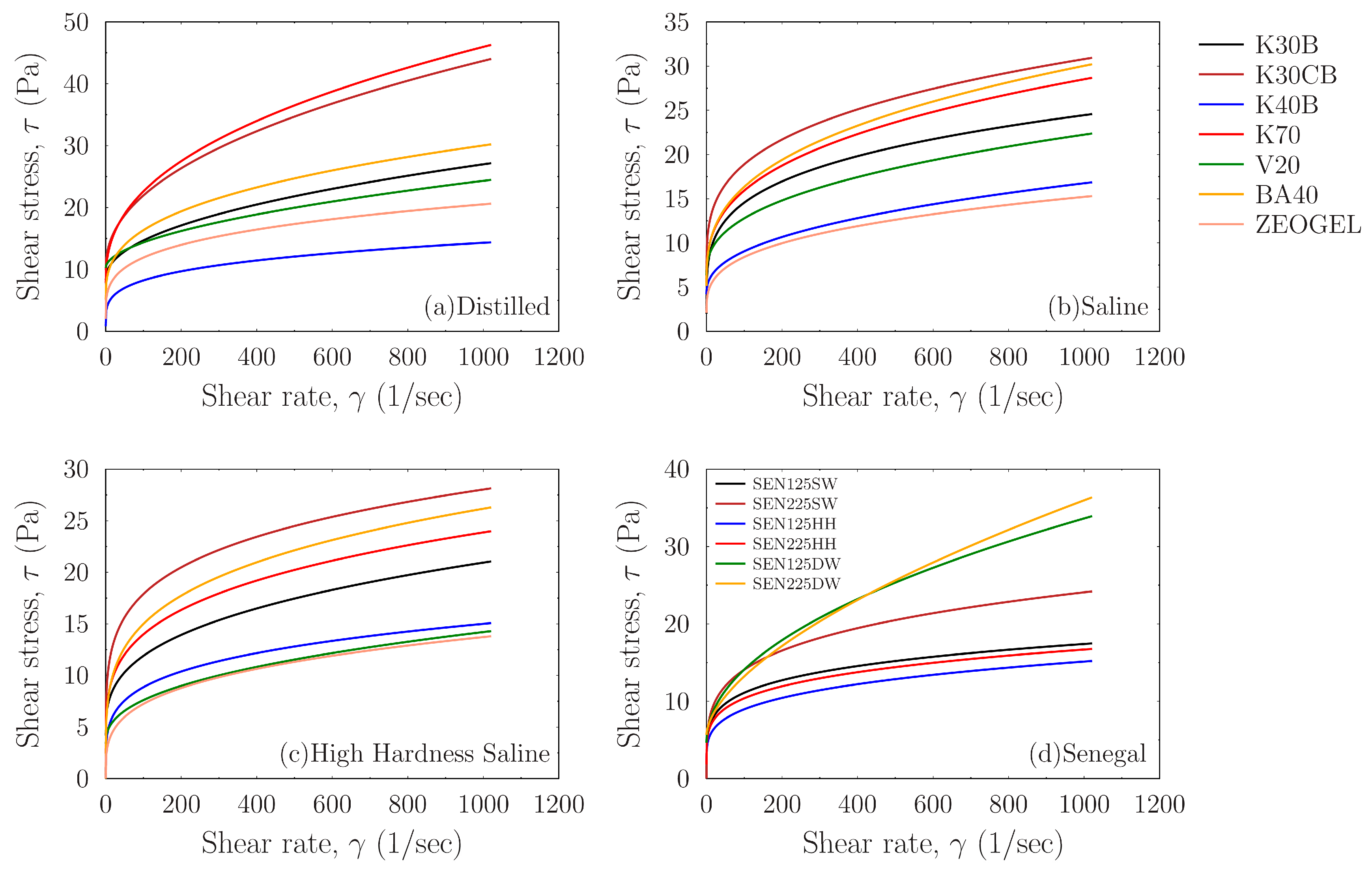

The fundamental rheological behavior of the prepared drilling fluids is presented in

Figure 7, which shows the flow curves (shear stress, τ, versus shear rate, γ) for all palygorskite suspensions examined. These curves provide a comprehensive fingerprint of each drilling fluid’s performance across the different aqueous environments. All suspensions exhibit non-Newtonian, pseudoplastic behavior, characterized by a non-linear relationship where viscosity decreases as shear rate increases. Furthermore, the positive intercepts on the shear stress axis indicate that all fluids possess a yield stress that is critical for suspending drill cuttings under static conditions.

Figure 7a illustrates the performance of the six activated Greek palygorskite drilling fluid suspensions and the commercial ZEOGEL in deionized water. There is a distinct hierarchy of performance among the samples. The suspensions prepared with samples K70 and K30CB exhibit the highest shear stresses across the entire range of shear rates, indicating they have higher thixotropy. Several other Greek samples, including BA40 and K30B, also show robust performance. Notably, these top-tier Greek samples compare quite well with the commercial ZEOGEL, which ranks low in the group. The sample K40B consistently shows the lowest rheological profile. The performance of samples K70 and K30CB in an environment like deionized water suggests they possess a combination of favorable intrinsic properties. As established in the literature [

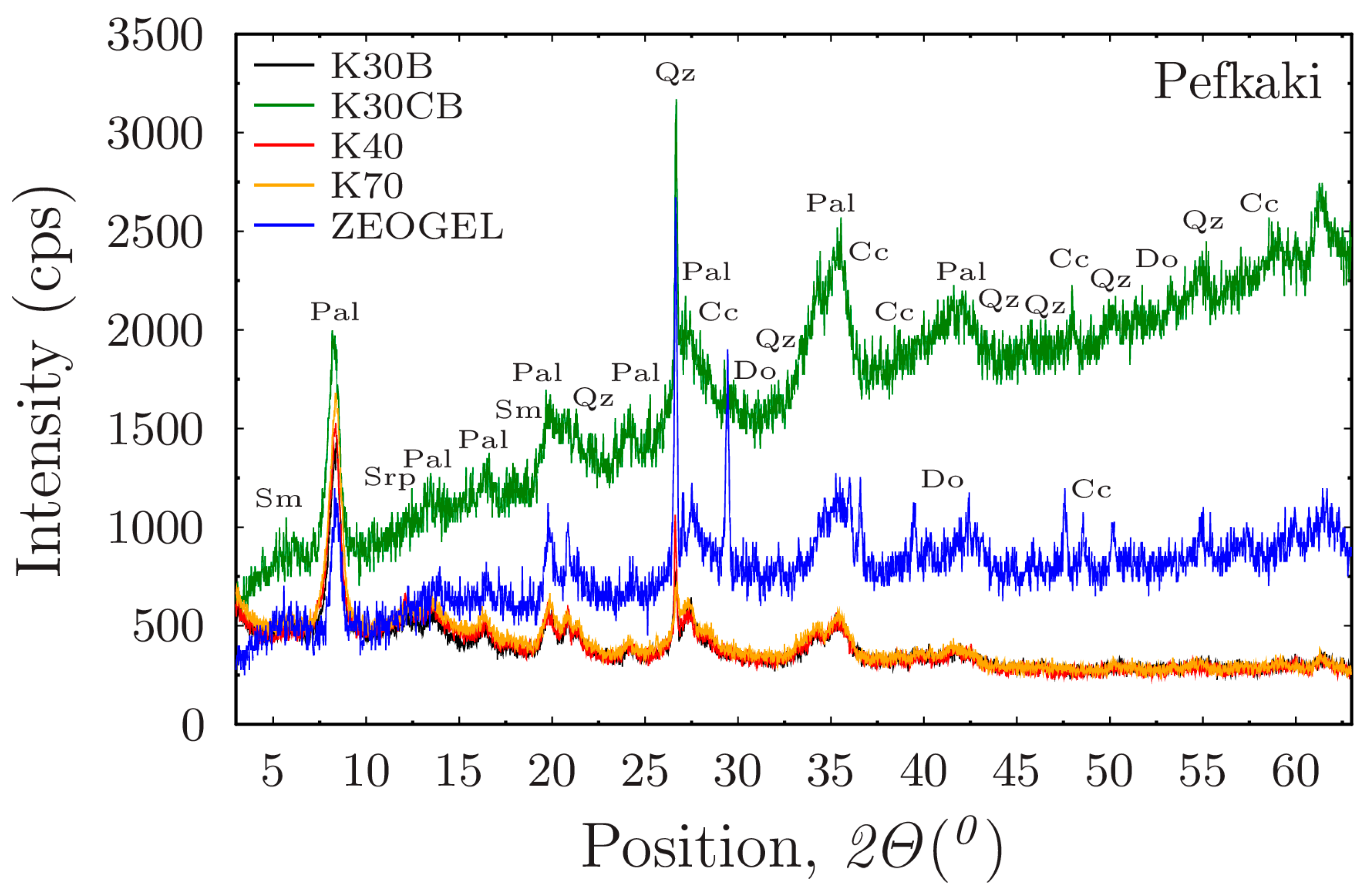

8], a higher aspect ratio (length-to-width) of palygorskite’s needle-like fibers leads to more efficient mechanical entanglement and the formation of a more robust ‘brush-heap’ structure. Therefore, the exceptionally high shear stresses generated by K70 and K30CB are indicative of a palygorskite component with these favorable morphological characteristics, combined with a high degree of purity and dispersion. This creates greater resistance to flow. The comparatively moderate performance of ZEOGEL can be linked to its mineralogical composition. The XRD analysis confirmed the presence of carbonate impurities (dolomite and calcite). These non-clay minerals act as inert solids with little contribution to the viscosity and effectively diluting the concentration of the active palygorskite, thus diminishing its overall viscosifying efficiency.

Figure 7b shows the flow curves for the same set of samples prepared in API-standard salt water (45 g/L NaCl). A general suppression of rheological performance is observed for most samples when compared to their behavior in deionized water, as evidenced by the overall lower shear stress values. However, the performance ranking remains largely consistent. Samples K70 and K30CB continue to be the top performers, maintaining a significant thixotropy advantage. The gap between the best-performing Greek clays and the commercial ZEOGEL appears to widen in this saline environment. The reduction in viscosity is primarily due to the presence of co-existing smectite in the raw clay samples. In a high-electrolyte environment, the sodium cations (Na+) from the salt compresses the electrical double layer (EDL) surrounding the smectite platelets. This neutralizes the electrostatic repulsive forces that cause smectite to swell and build viscosity in fresh water, leading to flocculation and a collapse of its contribution to the fluid’s structure. The sustained high performance of K70 and K30CB powerfully demonstrates the salt tolerance of palygorskite. Since palygorskite builds viscosity mainly through mechanical fiber entanglement, a mechanism independent of surface charge, it remains effective in this aqueous environment. These samples behave better because their rheology is dominated by their high-quality palygorskite component, which is resilient to the destabilizing effects of salinity.

Figure 7c presents the flow curves for the suspensions in the high-hardness saline environment, which contains divalent cations (Ca

2+ and Mg

2+) in addition to NaCl. The rheological suppression is even more pronounced in the high-hardness water. All samples exhibit lower shear stresses than in the standard salt water. The performance hierarchy is maintained, but the differentiation becomes starker. The K70 and K30CB samples retain a clear lead, while the lower-performing samples are clustered together at the bottom with very similar, diminished profiles. The severe degradation in performance is caused by the divalent cations (Ca

2+, Mg

2+). These ions are far more effective at compressing the EDL of smectite than monovalent Na+, leading to an almost complete neutralization of the smectite’s viscosifying contribution. In this harsh chemical environment, the measured rheology is almost exclusively a function of the palygorskite’s structural network and the MgO activation. The exceptional performance of K70 and K30CB under these challenging conditions underscores the high quality of their palygorskite fraction, confirming their suitability for applications in hard brines where conventional bentonite-based systems would fail entirely.

Figure 7d illustrates the rheological behavior of the commercial Senegal samples, activated with 2.25% MgO, across the three different aqueous environments. The results demonstrate that the performance of the activated clay is highly dependent on the make-up water. A notable trend is observed in the deionized water suspension (SEN225DW), which exhibits a unique profile: it shows high shear stress at low shear rates but is surpassed by the saltwater equivalent (SEN225SW) at higher shear rates. The crossover behavior suggests a complex interaction between the MgO activation and fluid chemistry. In deionized water, the highly activated clay may form initial aggregates that provide high initial viscosity but are susceptible to breaking down under increasing shear. In contrast, the electrolytes in the saline water may help stabilize the particle network, leading to a more durable structure at higher shear rates. This highlights that the effectiveness of the MgO activation is strongly influenced by the ionic environment of the drilling fluid. Positively charged MgO particles are believed to interact with the negatively charged surfaces of the clay fibers, strengthening the particle network and enhancing the gel structure, as suggested by [

18]. This leads to a more robust fluid and a higher yield point. The crossover behavior observed in

Figure 7d suggests a complex interaction between activation and fluid chemistry. In deionized water, the highly activated clay may form initial aggregates that break down under shear, while in saline water, the presence of electrolytes may help stabilize the MgO-clay interactions, leading to a more durable structure at higher shear rates.

When comparing the rheological profiles across the different sources, the top-performing Greek clays from the Pefkaki site (K70 and K30CB) consistently demonstrated a superior intrinsic quality. Even when compared to the highly activated Senegal benchmark (SEN225), these specific Ventzia samples generated higher shear stress, particularly in the challenging saline and high-hardness environments. The samples from the Belanida site also proved to be competitive, delivering a rheological performance that was often comparable to the main commercial drilling fluid ZEOGEL. The Senegal samples, in turn, serve as an excellent benchmark for the activation process itself because they show a strong and positive response to the 2.25% MgO treatment, achieving a high level of performance. However, results from the best Pefkaki samples suggest that their raw mineralogical characteristics, such as palygorskite purity and fiber aspect ratio, provide a higher performance ceiling that is less dependent on chemical enhancement alone.

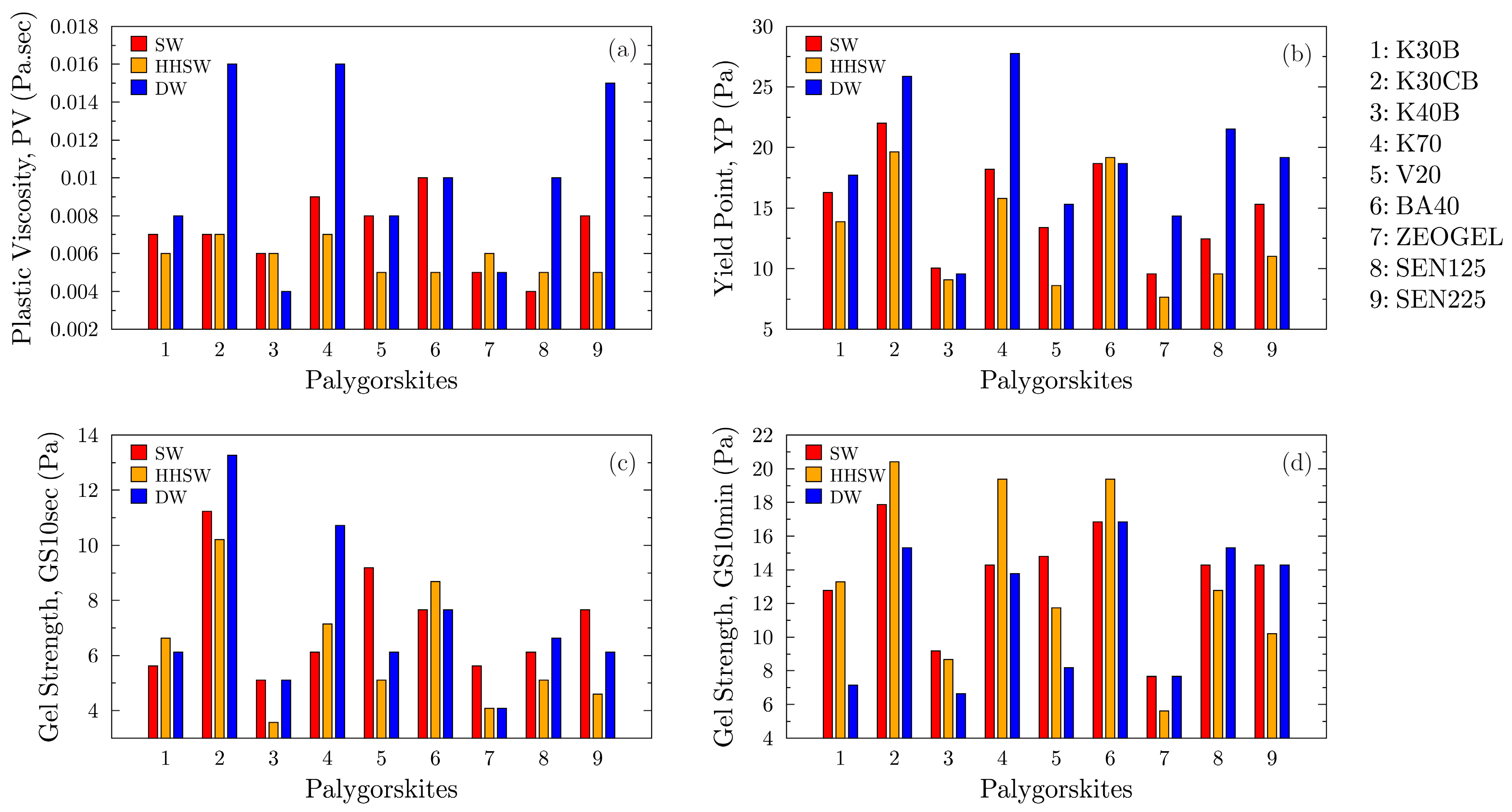

To quantify the performance differences observed in the flow curves, the data were used to calculate the standard American Petroleum Institute (API) rheological parameters.

Figure 8 presents a comparative analysis of the Plastic Viscosity (PV), Yield Point (YP), and the 10 s and 10 min Gel Strengths (GS) for all samples across the three aqueous environments. These parameters provide critical insights into the fluid’s mechanical friction, carrying capacity, and thixotropic properties.

Figure 8a shows the Plastic Viscosity, which represents the mechanical friction within the drilling fluid caused by the size, shape, and concentration of the suspended solids. In deionized water, samples K30CB and K70 exhibit the highest PV values, consistent with their superior performance in the flow curves. As the fluid environment becomes more saline, the PV of most Greek samples tends to decrease. In contrast, the commercial ZEOGEL and the Senegal benchmark samples show a more stable or slightly decreasing PV across the different water types. The high PV of K30CB and K70 in deionized water reflects a high concentration of well-dispersed, high-aspect-ratio fibers, which increases the potential for mechanical interference and friction under shear. The general decrease in PV for the Greek samples in saline and hard water is primarily a consequence of the flocculation of the co-existing smectite phase. As the smectite platelets aggregate due to charge neutralization, their contribution to the overall mechanical friction diminishes, resulting in a lower PV.

The relative stability of the commercial samples’ PV suggests they may contain less smectite or a less reactive form of it, making their mechanical friction properties less sensitive to changes in water chemistry.

The Yield Point, presented in

Figure 8b, is a measure of the electrochemical or attractive forces within the fluid under flow conditions. It is a critical indicator of a drilling fluid’s ability to lift and carry drill cuttings to the surface. The YP data strongly correlates with the overall performance trends. Samples K30CB and K70 demonstrate exceptionally high YP values in deionized water, far surpassing all other samples, including the highly activated Senegal clay SEN225. A dramatic reduction in YP is observed for all Greek samples upon introduction of salt (SW) and is further suppressed in the presence of divalent cations (HH). Despite this reduction, K30CB and K70 maintain the highest YP values among the Greek clays in these challenging environments. Notably, the highly activated Senegal sample (SEN225) shows robust YP performance in saline water, rivaling that of the top Greek samples. The outstanding YP of K30CB and K70 in deionized water is the result of a synergistic effect between the mechanical entanglement of the palygorskite fibers and the electrostatic repulsion of the well-dispersed smectite platelets. This creates a very strong and resilient fluid structure. The sharp drop in YP in saline environments is a clear indicator of the collapse of the smectite’s contribution due to flocculation. In SW and HH water, the measured YP is almost entirely dependent on the quality of the palygorskite’s “brush-heap” network and the effect of the MgO activation. The fact that K30CB and K70 still lead the Greek samples under these conditions confirms the high quality of their palygorskite component. The strong performance of SEN225 highlights the significant benefit of a higher MgO activation level in enhancing the particle-particle attractive forces that govern the YP.

The excellent performance of samples K30CB and K70, particularly their high yield point and viscosity, can be directly attributed to the morphological characteristics of their palygorskite fibers. As established in the literature, a high aspect ratio (length-to-width) of the individual fibers is the critical factor governing the performance of palygorskite in fluid suspensions. Studies by [

8] demonstrated a direct correlation, showing that samples with longer and thinner fibers exhibit significantly higher viscosity and yield values. This is because a higher aspect ratio promotes more efficient mechanical entanglement, leading to the formation of a more robust ‘brush-heap’ structure [

4]. Furthermore, the quality and crystallinity of the palygorskite, which is reflected in longer fiber lengths (10–50 μm), is known to be controlled by the magnesium content of the parent material [

51]. Therefore, while direct SEM imaging was not conducted as part of this study, the exceptional rheological data and parameters for K30CB and K70 serve as strong indirect evidence that these specific samples from the Ventzia basin possess a palygorskite component with these favorable, high-aspect-ratio morphological characteristics. The comparatively moderate performance of ZEOGEL, in contrast, can be linked to its mineralogical composition, as the presence of non-viscosifying carbonate impurities acts to dilute the concentration of the active palygorskite.

Figure 8c,d illustrate the 10 s and 10 min gel strengths, respectively. These parameters quantify the thixotropic nature of the fluid, which is its ability to form a gel structure under static conditions to suspend solids and then thin again upon agitation. The gel strength trends closely mirror those of the Yield Point. Samples K30CB and K70 consistently generate the most robust gel structures, especially in the 10 min measurement (

Figure 8d). The performance of K30CB is particularly remarkable in the high-hardness water (HH), where its 10 min gel strength is the highest of all samples, indicating exceptional stability. Conversely, the commercial ZEOGEL exhibits consistently low gel strengths across all environments, suggesting low suspension capacity during static periods. The strong gel development in samples K30CB and K70 is a direct result of their high-quality palygorskite network, which rapidly re-establishes its structure after shearing stops. The exceptional 10 min gel strength of K30CB in the high-hardness brine is a key finding. It demonstrates that this specific material can form a highly effective and cation-resistant thixotropic gel, making it ideal for challenging drilling applications were preventing the settling of cuttings is critical. The low gel strength performance of ZEOGEL appears as a deficiency. While it can provide viscosity under flow (as seen in its YP values), its weakness to form a strong static gel would make it unreliable for suspending weighting agents and cuttings when circulation is stopped.

It is also important to note the standout performance of sample BA40 in the 10 min gel strength measurement, particularly in the high-hardness brine (

Figure 8d). While its Yield Point is lower than that of the top-performing samples (K30CB & K70), its 10 min gel strength is exceptionally high. This behavior is likely attributed to a synergistic interaction between its palygorskite and smectite components. In the cation-rich HH environment, the aggressive flocculation of the smectite platelets creates aggregates that may not significantly contribute to the fluid’s dynamic strength. However, over a 10 min static period, these flocculated smectite structures can effectively reinforce the primary palygorskite fiber network, leading to the formation of an exceptionally robust static gel. This interpretation is consistent with BA40’s excellent filtration control performance in the same brine as it will be shown in Figure 10.

The pH of a drilling fluid is a master variable that influences clay hydration, additive performance, and overall system stability. It is important to note that the pH values reported in this study were not adjusted to a specific setpoint. Instead, they represent the final, un-buffered equilibrium pH that naturally resulted from the chemical interactions between each clay sample, the MgO activator, and the specific aqueous environment.

Figure 9 presents the final pH values measured for all palygorskite suspensions, providing insight into the chemical interactions between the clays and the three distinct aqueous environments. The results reveal a clear and systematic relationship between the fluid’s ionic composition and its final pH. A consistent trend is observed across all tested samples. Suspensions prepared in deionized water (DW) uniformly exhibit a strongly alkaline character, with pH values typically ranging from 9.5 to nearly 10.0. When the same clays are prepared in API-standard salt water (SW), the pH is consistently lowered into a mildly alkaline range, generally between 8.0 and 8.7. This effect is even more pronounced in the high-hardness salt water (HH), which drives the pH of all suspensions down to a near-neutral range of approximately 7.0 to 7.5.

The explanation for these systematic shifts lies in the governing chemical equilibria. The high alkalinity observed in deionized water is primarily driven by the hydrolysis of MgO, which was added as an activator. MgO reacts with water to form magnesium hydroxide, a base that releases hydroxide ions (OH−) and raises the pH. In the saline water, the high ionic strength of the NaCl solution creates a buffering effect that suppresses the dissolution of alkaline components, resulting in a lower final pH. The most significant chemical interaction occurs in the high-hardness brine. The high concentration of divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) readily reacts with the available hydroxide ions to precipitate as low-solubility hydroxides, primarily Mg(OH)2. This precipitation reaction effectively consumes the OH− ions from the fluid, preventing the pH from rising and stabilizing it near neutrality. This demonstrates the powerful buffering capacity of hard brines, an important consideration for drilling fluid formulation where pH control is critical.

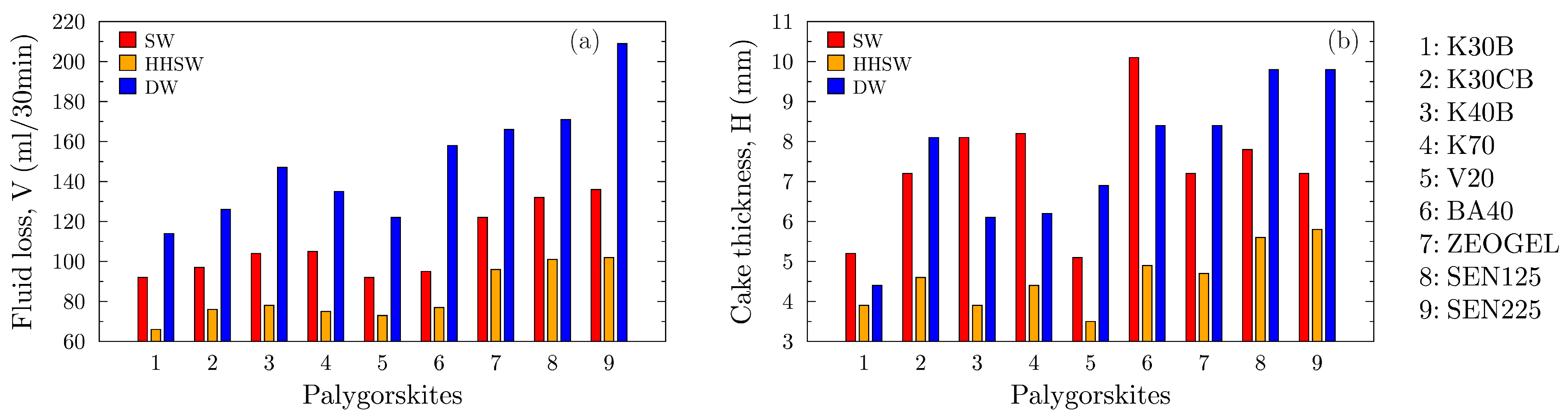

An essential function of a drilling fluid is to form a thin, low-permeability filter cake on the wellbore wall to minimize fluid invasion into the formation and ensure wellbore stability.

Figure 10 presents the results of the static LPLT filtration tests, showing the API fluid loss volume (a) and the corresponding filter cake thickness (b) for all suspensions. The results reveal a consistent and somewhat counterintuitive trend across all palygorskite samples. The highest fluid loss, indicating the poorest filtration control, is consistently observed in the deionized water (DW) suspensions. The introduction of salinity significantly improves performance, with the API salt water (SW) fluids showing substantially lower fluid loss. The best performance, characterized by the lowest fluid loss volumes, is uniformly achieved in the high-hardness salt water (HH) environment. This demonstrates that the same chemical conditions that suppress the fluid’s rheology enhance its sealing capabilities. Samples from the Ventzia basin, particularly K30B, V20, and BA40, exhibit excellent filtration control in the HH brine, with fluid loss values that are competitive with or superior to the commercial benchmarks.

The possible reason for this behavior is directly linked to the flocculation of the smectite component present in the clays. In deionized water, the smectite platelets are well-dispersed, and the palygorskite fibers form a network. This combination creates a relatively disordered and highly permeable filter cake, allowing a large volume of filtrate to pass through. In saline environments (SW and HH), cations neutralize the surface charges on the smectite, causing the platelets to flocculate into aggregates. These aggregates are far more effective at plugging the pores in the filter medium, creating a much less permeable seal and drastically reducing fluid loss. The divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) in the HH brine are particularly effective flocculants, which explains why the best filtration control is observed in this fluid.

The filter cake thickness data that is shown in

Figure 10b provides further insight into the cake’s structure. While high fluid loss in DW corresponds to a thick inefficient filter cake, the cakes formed in the saline fluids present a more complex picture. The flocculated aggregates in the SW environment often form a thick but low-permeability cake, as seen with sample BA40, which has the thickest cake in SW but maintains good fluid loss control. In the HH brine, the intense flocculation leads to the formation of a much thinner, denser, and more competent filter cake. This is the ideal scenario for a drilling fluid, minimal fluid loss combined with a thin, non-invasive filter cake. The ability of the Greek palygorskites to produce these high-quality filter cakes in hard brines underscores their potential for future use in drilling fluids.

A noteworthy observation in

Figure 10b is the behavior of sample BA40 in the API Salt Water (SW). While it provides effective filtrate loss control, it forms a comparatively thick filter cake that seems counterintuitive. This phenomenon can be explained by the microstructure of the cake formed by flocculated smectite in a monovalent saline environment. The sodium cations in the SW brine induce a voluminous ‘house-of-cards’ flocculation of the smectite platelets. This structure is inherently thick because it does not pack efficiently and traps a significant amount of fluid within its matrix. However, the flow paths through this network are highly tortuous, which does not allow easy transmissibility for filtrate loss resulting in effective fluid loss control. This contrasts with the behavior in the high-hardness brine, where divalent cations promote more compact aggregation, leading to the formation of a much thinner and denser filter cake, as observed for most samples in the HH environment.

Figure 11 presents a direct comparison of the rheological performance of selected activated Greek palygorskite samples (K30CB, BA40, K70), commercial benchmarks (ZEOGEL), and activated Senegal clays (SEN125, SEN225). The flow curves are plotted for (a) API Salt Water (SW) and (b) High-Hardness Salt Water (HH). In

Figure 11a,b, the curves demonstrate non-Newtonian, pseudoplastic behavior with a distinct yield stress, which is characteristic of effective drilling fluid viscosifiers.

The presented comparison of

Figure 11 provides visual evidence for the high performance of the activated Greek palygorskite. The materials sourced from the Ventzia basin, particularly samples K30CB, BA40 and 70, show comparable behavior to established commercial and international benchmarks in demanding saline and high-hardness conditions. The ability of the Greek clays to maintain a significant rheological advantage in the presence of high concentrations of monovalent and divalent cations shows their robustness and high intrinsic quality. This confirms their strong potential as a high-performance, locally sourced alternative for formulating resilient water-based drilling fluids for challenging environments.