Thermal, Structural, and Phase Evolution of the Y2(SO4)3*8H2O–Eu2(SO4)3*8H2O System via Dehydration and Volatilization to Y2(SO4)3–Eu2(SO4)3 and Y2O2(SO4)–Eu2O2(SO4) and Its Thermal Expansion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Powder X-Ray Diffraction

2.3. High-Temperature Powder X-Ray Diffraction

2.4. Single Crystal X-Ray Diffraction

2.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

2.6. Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Powder X-Ray Diffraction of the (Y1−xEux)2(SO4)3*8H2O Solid Solutions

3.2. Description of the YEu(SO4)3*8H2O and (Y0.83Eu0.17)2(SO4)3*8H2O Crystal Structures

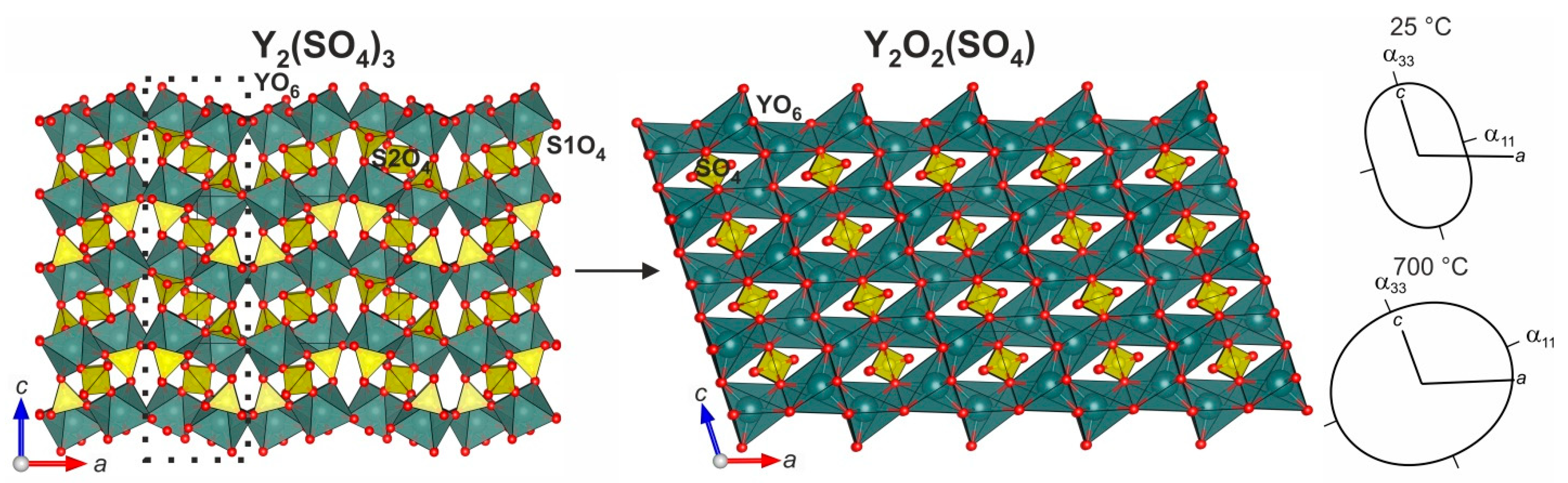

3.3. (Y1−xEux)2(SO4)3*8H2O Thermal Transformations and Thermal Expansion of Products of Its Decomposition

3.4. Crystal Structure Relations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Bernhardt, E.S. Biogeochemistry: An Analysis of Global Change; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Komissarova, L.N.; Pyshkina, G.Y.; Schatskiy, V.M.; Znamenskaya, A.S.; Dolgich, V.A.; Syponitskiy, Y.L.; Schacno, I.V.; Pokrovskiy, A.N.; Chizhov, S.M.; Balki, T.I.; et al. Compounds of Rare Earth Elements; Nauka Press: Moscow, Russia, 1986. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sha, H.; Wang, Z.; He, C.; Su, R.; Yang, X.; Long, X. Nonlinear optical inorganic sulfates: The improvement of the phase matching ability driven by the structural modulation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 494, 215345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, F.C.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Burns, P.C. The crystal chemistry of sulfate minerals. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2000, 40, 1–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siidra, O.I.; Borisov, A.S.; Lukina, E.A.; Depmeier, W.; Platonova, N.V.; Colmont, M.; Nekrasova, D.P. Reversible hydration/dehydration and thermal expansion of euchlorine, ideally KNaCu3O(SO4)3. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2019, 46, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siidra, O.I.; Borisov, A.S.; Charkin, D.O.; Depmeier, W.; Platonova, N.V. Evolution of fumarolic anhydrous copper sulfate minerals during successive hydration/dehydration. Min. Mag. 2021, 85, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podberezskaya, N.V.; Borisov, S.V. Utochnenie kristallicheskoi struktury Sm2(SO4)3(H2O)8. Zhurnal Strukt. Khimii 1976, 17, 186–188. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Hiltunen, L.; Niinisto, L. Ytterbium sulfate octahydrate, Yb2(SO4)3(H2O)8. Cryst. Struct. Comm. 1976, 5, 561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Gebert, S.E. The structure of Pr2(SO4)3(H2O)8 and La2(SO4)3(H2O)9. J. Solid. State Chem. 1976, 19, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bartl, H.; Rodek, E. Untersuchung der Kristallstruktur von Nd2(SO4)3·(H2O)8. Z. Krist. 1983, 162, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Held, P.; Wickleder, M. Yttrium(III) sulfate octahydrate. Acta Cryst. 2003, 59, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickleder, M.S. Inorganic Lanthanide Compounds with Complex Anions. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 2011–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendland, W.W. The thermal decomposition of yttrium and rare earth metal sulfate hydrates. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1958, 7, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, L.A.; Lemenkova, A.F.; Serebrennikov, V.V. On the loss of crystallization water by sulfates of rare earth elements of the cerium group. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 1959, 34, 1382–1385. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Wendland, W.W.; George, T.D. A differential thermal analysis study of the dehydration of the rare-earth(III) sulfate hydrates. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1961, 19, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, L.L.; Ilyashenko, V.S.; Konarev, M.I.; Konovalov, L.N.; Lipis, L.V.; Chebotarev, N.T. Physicochemical properties of crystal hydrates of rare earth elements of the terbium subgroup. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 1965, 10, 1761–1770. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Brittain, H.G. Thermal decomposition of Eu2(SO4)3·8H2O studied by high resolution luminescence spectroscopy. J. Less Common Met. 1983, 93, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisenko, Y.G.; Khritokhin, N.A.; Andreev, O.V.; Basova, S.A.; Sal’nikova, E.I.; Polkovnikov, A.A. Thermal decomposition of europium sulfates Eu2(SO4)3·8H2O and EuSO4. J. Solid. State Chem. 2017, 255, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shizume, K.; Hatada, N.; Uda, T. Experimental study of hydration/dehydration behaviors of metal sulfates M2(SO4)3 (M = Sc, Yb, Y, Dy, Al, Ga, Fe, In) in search of new low-temperature thermochemical heat storage materials. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 13521–13527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisenko, Y.G.; Atuchin, V.V.; Molokeev, M.S.; Sedykh, A.E.; Khritokhin, N.A.; Aleksandrovsky, A.S.; Oreshonkov, A.S.; Shestakov, N.P.; Adichtchev, S.V.; Pugachev, A.M.; et al. Exploration of the crystal structure and thermal and spectroscopic properties of monoclinic praseodymium sulfate Pr2(SO4)3. Molecules 2022, 27, 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plyasova, L.M.; Borisov, S.V.; Belov, N.V. The garnet pattern in the structure of iron molybdate. Sov. Phys. Crystallogr. 1967, 12, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, A.F. Structural Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1984; p. 606. [Google Scholar]

- Piffard, Y.; Verbaere, A.; Kinoshita, M. β-Zr2(PO4)2SO4: A zirconium phosphato-sulfate with a Sc2(WO4)3 structure. A comparison between garnet, nasicon, and Sc2(WO4)3 structure types. J. Solid State Chem. 1987, 71, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamf, A.R. Grandreefite, Pb2F2SO4: Crystal structure and relationship to the lanthanide oxide sulfates, Ln2O2SO4. Am. Min. 1991, 76, 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Krivovichev, S.V.; Filatov, S.K. Crystal Chemistry of Minerals and Inorganic Compounds with Complexes of Anion-Centered Tetrahedra; St. Petersburg University Press: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bubnova, R.S.; Firsova, V.A.; Volkov, S.N.; Filatov, S.K. RietveldToTensor: Program for processing powder X-ray diffraction data under variable conditions. Glass Phys. Chem. 2018, 44, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRYSALISPRO Software System, version 1.171.39.44; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction: Oxford, UK, 2015.

- Petricek, V.; Dusek, M.; Palatinus, L. Crystallographic Computing System JANA2006: General Features. Z. Crystallogr. 2014, 229, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised rffective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. 1976, A32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shablinskii, A.P.; Shorets, O.Y.; Povotskiy, A.V.; Bubnova, R.S.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G.; Janson, S.Y.; Ugolkov, V.L.; Filatov, S.K. Novel Y2(SO4)3:Eu3+ Phosphors with Anti-Thermal Quenching of Luminescence Due to Giant Negative Thermal Expansion. Crystals 2024, 14, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.H.; Kim, M.K.; Jo, V.; Lee, D.W.; Shim, I.W.; Ok, K.M. Hydrothermal syntheses, structures, and characterizations of two lanthanide sulfate hydrates materials, La2(SO4)3·(H2O) and Eu2(SO4)3·4(H2O). Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2010, 31, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, R.M.; Finger, L.W. Comparative Crystal Chemistry: Temperature, Pressure, Composition and the Variation of Crystal Structure; John Wiley: Chichester, UK; Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1982; 231p. [Google Scholar]

- Filatov, S.K. High Temperature Crystal Chemistry; Nedra: Leningrad, Russia, 1990. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.Y.; Zheng, Y.Q. Crystal structure of dieuropium trisulfate octahydrate, Eu2(SO4)3∙8H2O. Z. Krist. 2003, 218, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisenko, Y.G.; Aleksandrovsky, A.S.; Atuchin, V.V.; Krylov, A.S.; Molokeev, M.S.; Oreshonkov, A.S.; Shestakov, N.P.; Andreev, O.V. Exploration of structural, thermal and spectroscopic properties of self-activated sulfate Eu2(SO4)3 with isolated SO4 groups. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 68, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisenko, Y.G.; Azarapin, N.O.; Khritokhin, N.A.; Andreev, O.V.; Volkova, S.S. Europium oxysulfate Eu2O2SO4 crystal structure. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 64, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, I.D. The bond-valence method: An empirical approach to chemical structure and bonding. In Structure and Bonding in Crystals 2; O’Keeffe, M., Navrotsky, A., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne, F.C. The structure hierarchy hypothesis. Min. Mag. 2014, 78, 957–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, O.C.; Hawthorne, C. Comprehensive derivation of bond-valence parameters for ion pairs involving oxygen. Acta Cryst. 2015, B71, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickleder, M.S. Wasserfreie Sulfate der Selten-Erd-Elemente: Synthese und Kristallstruktur von Y2(SO4)3 und Sc2(SO4)3. Z. Für Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2000, 626, 1468–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronkov, A.A.; Ilyukhin, V.V.; Belov, N.V. Crystal chemistry of mixed frameworks. Principles of their formation. Kristallografiya 1975, 20, 556–566. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Oreshonkov, A.S.; Denisenko, Y.G. Structural Features of Y2O2SO4 via DFT Calculations of Electronic and Vibrational Properties. Materials 2021, 14, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.S.O.; Mary, T.A.; Sleight, A.W. Negative thermal expansion in a large molybdate and tungstate family. J. Solid State Chem. 1997, 13, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.O.; Mary, T.A.; Sleight, A.W. Negative thermal expansion in Sc2(WO4)3. J. Solid State Chem. 1998, 137, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatov, S.K.; Andrianova, L.V.; Bubnova, R.S. Regularities of thermal deformations in monoclinic crystals. Cryst. Res. Technol. 1984, 19, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatov, S.K. Negative linear thermal expansion of oblique-angle (monoclinic and triclinic) crystals as a common case. Phys. Status Solidi 2008, 245, 2490–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Formula | Y0.98Eu1.02(SO4)3*8H2O | ||

| Crystal System, Space Group | Monoclinic, C2/c | ||

| Temperature (°C) | −173 | −73 | 77 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 13.4673 (9), 6.7289 (4), 18.2203 (10) | 13.4856 (9), 6.7287 (4), 18.2442 (10) | 13.5343 (9), 6.7250 (4), 18.3136 (10) |

| β (°) | 102.148 (7) | 102.143 (7) | 102.119 (7) |

| V (Å3) | 1614.15 (17) | 1618.45 (17) | 1629.72 (18) |

| Z | 4 | ||

| Radiation type | Mo Kα | ||

| µ (mm−1) | 7.92 | 7.90 | 7.85 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.04 × 0.03 × 0.01 | ||

| Diffractometer | XtaLAB Synergy, Single source at home/near, HyPix | ||

| Absorption correction | CrysAlis PRO1.171.41.104a Empirical absorption correction using spherical harmonics, implemented in SCALE3 ABSPACK scaling algorithm. | ||

| Tmin, Tmax | 0.565, 1 | 0.574, 1 | 0.308, 1 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 3σ(I)] reflections | 13,818, 2839, 2476 | 13,846, 2848, 2432 | 13,747, 2849, 2351 |

| Rint | 0.057 | 0.056 | 0.054 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.779 | 0.777 | 0.777 |

| R(obs), wR(obs), S | 0.026, 0.032, 1.25 | 0.025, 0.031, 1.20 | 0.027, 0.031, 1.13 |

| No. of reflections | 2839 | 2848 | 2849 |

| No. of parameters | 147 | 146 | 146 |

| H-atom treatment | All H-atom parameters refined | ||

| Chemical formula | Y1.89Eu0.11(SO4)3*8H2O | ||

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, C2/c | ||

| Temperature (°C) | −173 | −73 | 77 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 13.4358 (9), 6.6941 (4), 18.183 (1) | 13.4628 (9), 6.6939 (4), 18.1994 (10) | 13.5130 (9), 6.6953 (4), 18.2531 (10) |

| β (°) | 102.030 (7) | 102.023 (7) | 101.999 (7) |

| V (Å3) | 1599.47 (17) | 1604.13 (17) | 1615.34 (17) |

| Z | 4 | ||

| Radiation type | Mo Kα | ||

| µ (mm−1) | 7.75 | 7.72 | 7.67 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.04 × 0.03 × 0.01 | ||

| Diffractometer | XtaLAB Synergy, Single source at home/near, HyPix | ||

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan CrysAlis PRO 1.171.42.102a (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, Abingdon, UK, 2023) Empirical absorption correction using spherical harmonics, implemented in SCALE3 ABSPACK scaling algorithm. | ||

| Tmin, Tmax | 0.758, 1 | 0.771, 1 | 0.805, 1 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 3σ(I)] reflections | 9674, 2695, 2170 | 9750, 2716, 2051 | 9816, 2746, 1998 |

| Rint | 0.038 | 0.046 | 0.044 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.781 | 0.781 | 0.779 |

| R(obs), wR(obs), S | 0.031, 0.042, 1.69 | 0.033, 0.040, 1.41 | 0.035, 0.043, 1.56 |

| No. of reflections | 2695 | 2716 | 2746 |

| No. of parameters | 147 | 146 | 146 |

| H-atom treatment | All H-atom parameters refined | ||

| x | T, °C | α11 | α22 = αb | α33 | αa | αc | αβ | μc^α33 | αV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 30 | 50 (1) | 15 (1) | 14 (1) | 41 (1) | 29 (3) | 19 (1) | 41.4 | 78 (1) |

| 50 | 43 (1) | 9 (2) | 23 (2) | 41 (1) | 9 (3) | 9 (2) | 32.3 | 75 (3) | |

| 70 | 41 (2) | 3 (5) | 28 (3) | 40 (2) | 28 (2) | −1 (2) | 2.4 | 71 (4) | |

| 100 | 52 (3) | −5 (1) | 20 (2) | 40 (1) | 26 (3) | −16 (4) | 26.0 | 66 (2) | |

| 0.17 | 30 | 8 (1) | 9 (1) | 25 (1) | 19 (1) | 18 (3) | 9 (1) | 42.0 | 43 (3) |

| 50 | 26 (1) | 6 (2) | 16 (2) | 24 (1) | 20 (3) | 5 (2) | 40.4 | 48 (3) | |

| 70 | 29 (2) | 2 (5) | 22 (3) | 28 (2) | 22 (2) | 2 (2) | 19.0 | 53 (4) | |

| 100 | 37 (3) | −3 (1) | 26 (2) | 35 (1) | 26 (3) | −4 (4) | 13.9 | 60 (2) | |

| 0.33 | 30 | 19 (1) | 7 (2) | 8 (2) | 17 (1) | 12 (3) | 5 (2) | 35.1 | 34 (3) |

| 50 | 29 (2) | 6 (5) | 21 (3) | 29 (2) | 21 (2) | 1 (2) | 10.6 | 56 (4) | |

| 70 | 43 (1) | 5 (1) | 31 (1) | 41 (1) | 31 (3) | −4 (1) | 12.4 | 78 (3) | |

| 100 | 65 (1) | 4 (2) | 42 (2) | 56 (1) | 46 (3) | −11 (2) | 23.1 | 111 (3) | |

| 0.50 | 30 | 26 (1) | 12 (2) | 18 (2) | 21 (1) | 21 (3) | −4 (2) | 39.9 | 57 (3) |

| 50 | 32 (2) | 6 (5) | 21 (3) | 25 (2) | 25 (2) | −6 (2) | 36.9 | 59 (4) | |

| 70 | 37 (1) | 0 (1) | 23 (1) | 30 (1) | 28 (3) | −7 (1) | 35.3 | 61 (3) | |

| 100 | 45 (1) | −8 (2) | 27 (2) | 36 (1) | 33 (3) | −10 (2) | 33.8 | 64 (3) | |

| 0.83 | 30 | 28 (1) | −12 (1) | 20 (1) | 28 (1) | 22 (3) | 3 (1) | 27.4 | 36 (3) |

| 50 | 31 (1) | −7 (2) | 25 (2) | 31 (1) | 25 (3) | 1 (2) | 14.9 | 50 (3) | |

| 70 | 35 (2) | −1 (5) | 29 (3) | 34 (2) | 29 (2) | −1 (2) | 4.6 | 63 (4) | |

| 100 | 42 (1) | 7 (1) | 33 (1) | 39 (1) | 35 (3) | −4 (1) | 23.8 | 82 (3) | |

| 1 | 30 | 51 (1) | 5 (2) | 31 (2) | 48 (1) | 38 (3) | 9 (2) | 35.1 | 87 (3) |

| 50 | 41 (2) | 4 (5) | 29 (3) | 40 (2) | 31 (2) | 4 (2) | 26.6 | 74 (4) | |

| 70 | 32 (1) | 4 (1) | 24 (1) | 32 (1) | 24 (3) | 0 (1) | 2.9 | 60 (3) | |

| 100 | 26 (1) | 3 (2) | 11 (2) | 20 (1) | 14 (3) | −7 (2) | 27.4 | 40 (3) |

| x | T, °C | a11 | a22 = αb | a33 | αa | αc | αβ | μc3 | αV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y2O2SO4 | 100 | 10.13 (3) | 8.40 (3) | 14.1 (5) | 10.5 (3) | 14.1 (2) | 0.56 (7) | 0.8 | 33 (3) |

| 300 | 12.76 (5) | 8.62 (1) | 14.5 (7) | 11.7 (1) | 14.5 (1) | 0.17 (5) | 3.0 | 36 (3) | |

| 500 | 15.42 (4) | 8.86 (3) | 14.8 (2) | 14.1 (3) | 14.7 (2) | −0.20 (1) | 12.8 | 39 (2) | |

| 700 | 18.00 (1) | 9.09 (2) | 15.2 (4) | 17.6 (4) | 15.2 (1) | −0.59 | 3.5 | 42 (1) | |

| Y2(SO4)3 [30] | 300 | =αa | −11 (1) | =αc | −4 (1) | −8 (3) | - | - | −23 (2) |

| 400 | =αa | −10 (2) | =αc | −2 (3) | −17 (3) | - | - | −29 (2) | |

| 500 | =αa | −8 (3) | =αc | −1 (3) | −25 (1) | - | - | −34 (3) | |

| (Y0.83Eu0.17)2(SO4)3 [30] | 300 | =αa | −11 (2) | =αc | −1 (3) | −10 (2) | - | - | −22 (1) |

| 400 | =αa | −11 (1) | =αc | −2 (1) | −11 (1) | - | - | −23 (1) | |

| 500 | =αa | −12 (2) | =αc | −2 (3) | −11 (2) | - | - | −24 (1) | |

| (Y0.67Eu0.33)2(SO4)3 | 300 | =αa | −10 (4) | =αc | −1 (7) | −10 (5) | - | - | −21 (3) |

| 400 | =αa | −10 (5) | =αc | −2 (4) | −10 (4) | - | - | −22 (5) | |

| 500 | =αa | −10 (5) | =αc | −3 (4) | −10 (4) | - | - | −23 (6) | |

| (Y0.50Eu0.50)2(SO4)3 [30] | 300 | =αa | −14 (3) | =αc | −7 (3) | −13 (2) | - | - | −34 (3) |

| 400 | =αa | −15 (1) | =αc | −7 (1) | −17 (1) | - | - | −39 (3) | |

| 500 | =αa | −15 (3) | =αc | −7 (3) | −22 (2) | - | - | −44 (2) | |

| Eu2(SO4)3 | 300 | 4.22 (8) | 5.6 (1) | 12.8 (2) | 4.4 (1) | 12.8 (2) | −0.07 (6) | 10.1 | 22.6 (4) |

| 400 | 1.82 (6) | 5.7 (2) | 12.7 (4) | 2.1 (2) | 12.7 (4) | −0.14 (9) | 10.4 | 20.2 (7) | |

| 500 | −0.58 (4) | 5.8 (4) | 12.5 (8) | −0.3 (4) | 12.5 (8) | −0.20 (2) | 10.5 | 17 (1) | |

| 600 | −3.0 (3) | 5.9 (6) | 12 (1) | −2.6 (5) | 12 (1) | −0.26 (2) | 10.6 | 15 (2) |

| Compound | Eu2(SO4)3*8H2O | Eu2(SO4)3 | Eu2O2SO4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | C2/c | ||

| a, Å | 13.555 (2) | 21.2787 (8) | 13.6952 (1) |

| b, Å | 6.757 (1) | 6.6322 (3) | 4.1929 (4) |

| c, Å | 18.317 (2) | 6.8334 (3) | 8.1393 (2) |

| β, ° | 102.27 (1) | 108.002 (2) | 107.455 (4) |

| V, Å3 | 1639.4 (1) | 917.16 (6) | 467.38 |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| T, °C | 0 | 25 | –153 |

| References | [34] | [35] | [36] |

| Compound | Y2(SO4)3*8H2O | Y2(SO4)3 | Y2O2SO4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | C2/c | Pbcn | C2/c |

| a, Å | 13.4802 (9) | 12.740 (1) | 13.3076 |

| b, Å | 6.6846 (4) | 9.1676 (9) | 4.1465 |

| c, Å | 18.216 (1) | 9.2608 (7) | 8.0204 |

| β, ° | 101.977 (7) | 90 | 107.64 |

| V, Å3 | 1605.7 (1) | 1081.6 (1) | 467.38 |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| T, °C | 20 | 20 | 0 * |

| References | [11] | [40] | [42] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shablinskii, A.P.; Shorets, O.Y.; Bubnova, R.S.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G.; Avdontceva, M.S.; Filatov, S.K. Thermal, Structural, and Phase Evolution of the Y2(SO4)3*8H2O–Eu2(SO4)3*8H2O System via Dehydration and Volatilization to Y2(SO4)3–Eu2(SO4)3 and Y2O2(SO4)–Eu2O2(SO4) and Its Thermal Expansion. Minerals 2025, 15, 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121304

Shablinskii AP, Shorets OY, Bubnova RS, Krzhizhanovskaya MG, Avdontceva MS, Filatov SK. Thermal, Structural, and Phase Evolution of the Y2(SO4)3*8H2O–Eu2(SO4)3*8H2O System via Dehydration and Volatilization to Y2(SO4)3–Eu2(SO4)3 and Y2O2(SO4)–Eu2O2(SO4) and Its Thermal Expansion. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121304

Chicago/Turabian StyleShablinskii, Andrey P., Olga Y. Shorets, Rimma S. Bubnova, Maria G. Krzhizhanovskaya, Margarita S. Avdontceva, and Stanislav K. Filatov. 2025. "Thermal, Structural, and Phase Evolution of the Y2(SO4)3*8H2O–Eu2(SO4)3*8H2O System via Dehydration and Volatilization to Y2(SO4)3–Eu2(SO4)3 and Y2O2(SO4)–Eu2O2(SO4) and Its Thermal Expansion" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121304

APA StyleShablinskii, A. P., Shorets, O. Y., Bubnova, R. S., Krzhizhanovskaya, M. G., Avdontceva, M. S., & Filatov, S. K. (2025). Thermal, Structural, and Phase Evolution of the Y2(SO4)3*8H2O–Eu2(SO4)3*8H2O System via Dehydration and Volatilization to Y2(SO4)3–Eu2(SO4)3 and Y2O2(SO4)–Eu2O2(SO4) and Its Thermal Expansion. Minerals, 15(12), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121304