Neodymium-Rich Monazite of the Lemhi Pass District, Idaho and Montana: Chemistry and Geochronology †

Abstract

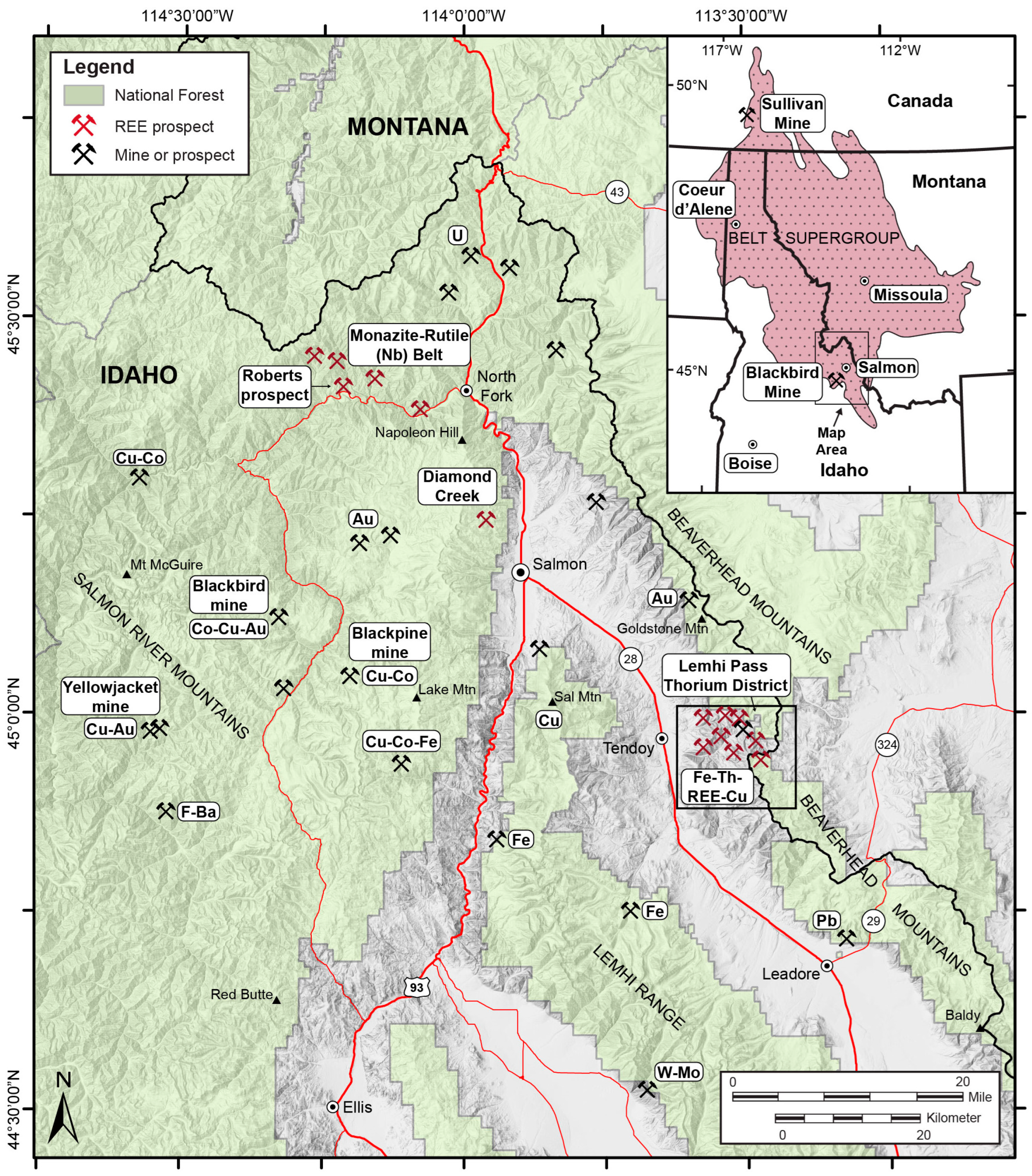

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fieldwork and Chemistry

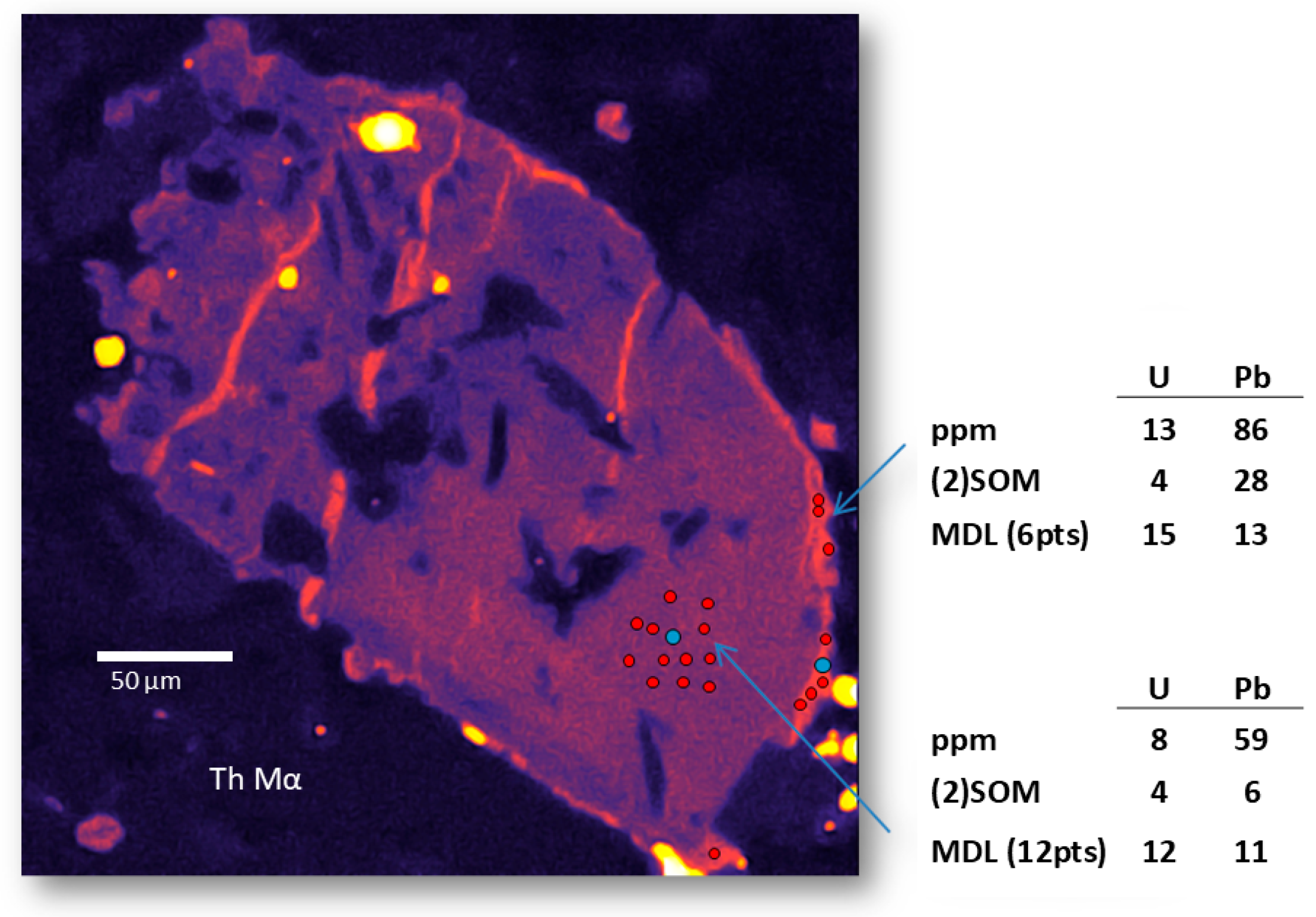

2.2. U-Th-Total Pb Electron Microprobe Geochronology on Monazite

2.2.1. General Summary

2.2.2. Analytical Procedure for EPMA Geochronology

3. Descriptions, Compositions, and Age of the REE-Th Deposits

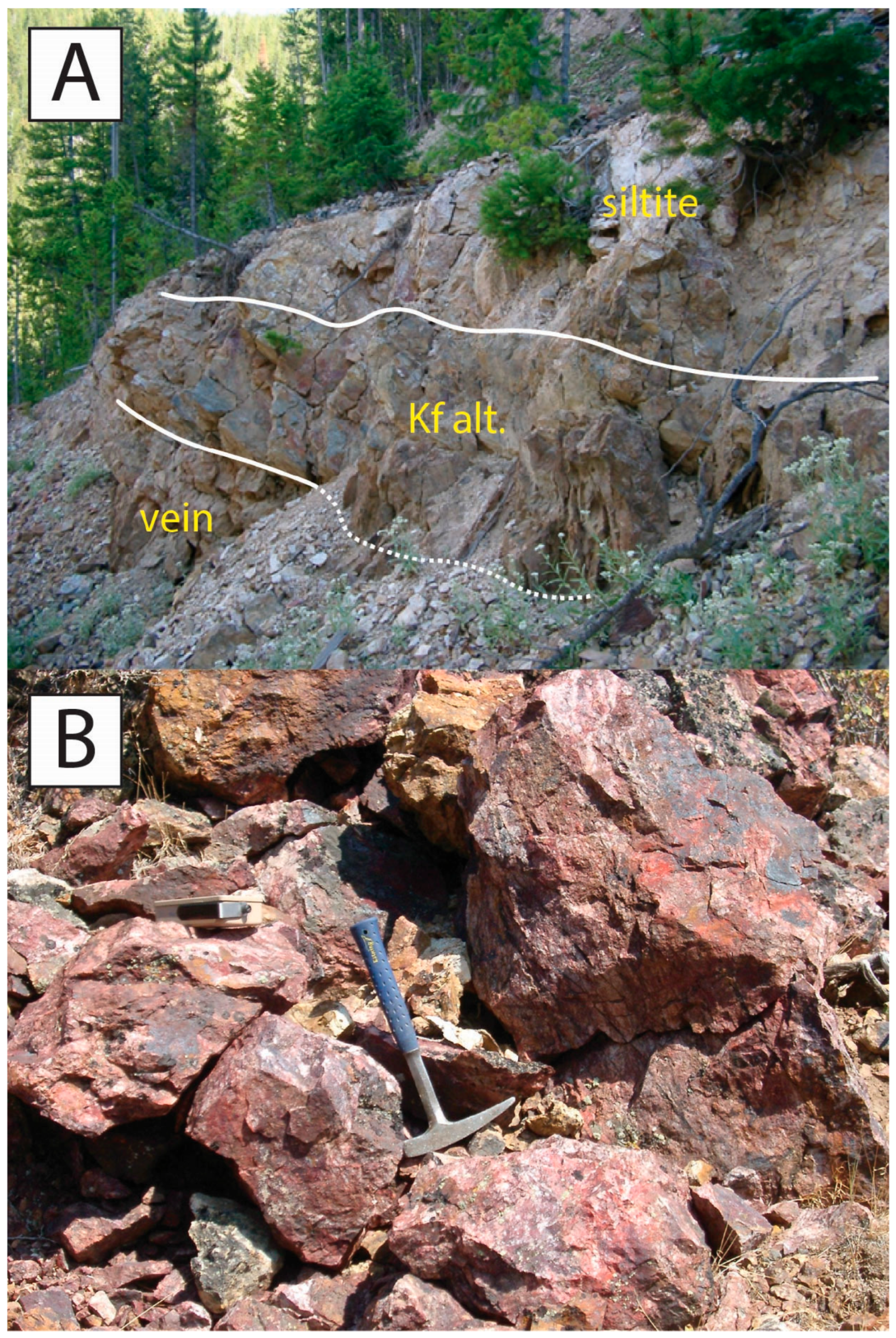

3.1. Field Exposures of the Monazite-Bearing Deposits

3.1.1. Quartz Vein Deposits at the Last Chance and Cago Prospects

3.1.2. Lucky Horseshoe Shear Zone Deposit

3.1.3. Field and Argon Geochronology Constraints on Timing of REE Mineralization

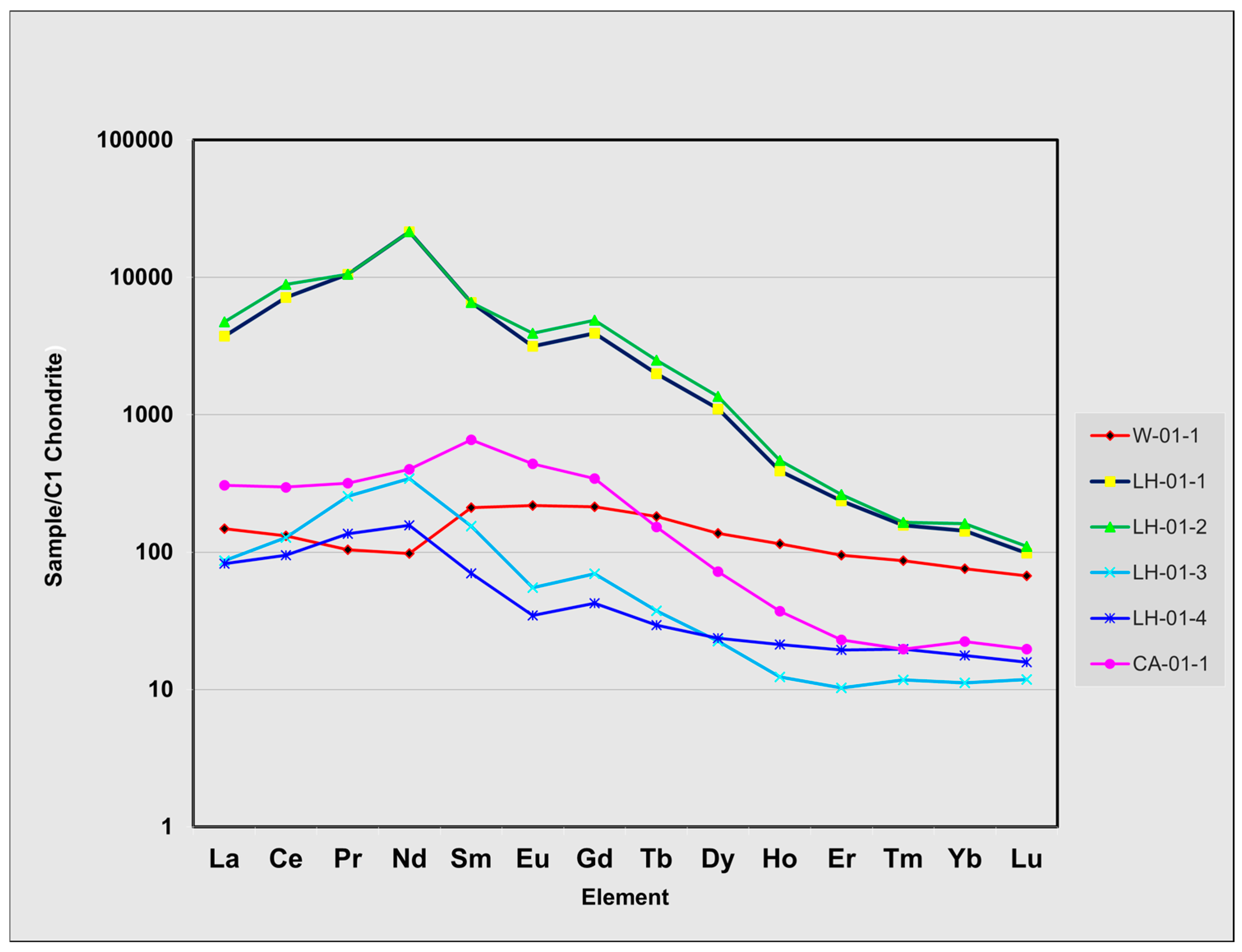

3.2. Lemhi Pass Rock Geochemistry

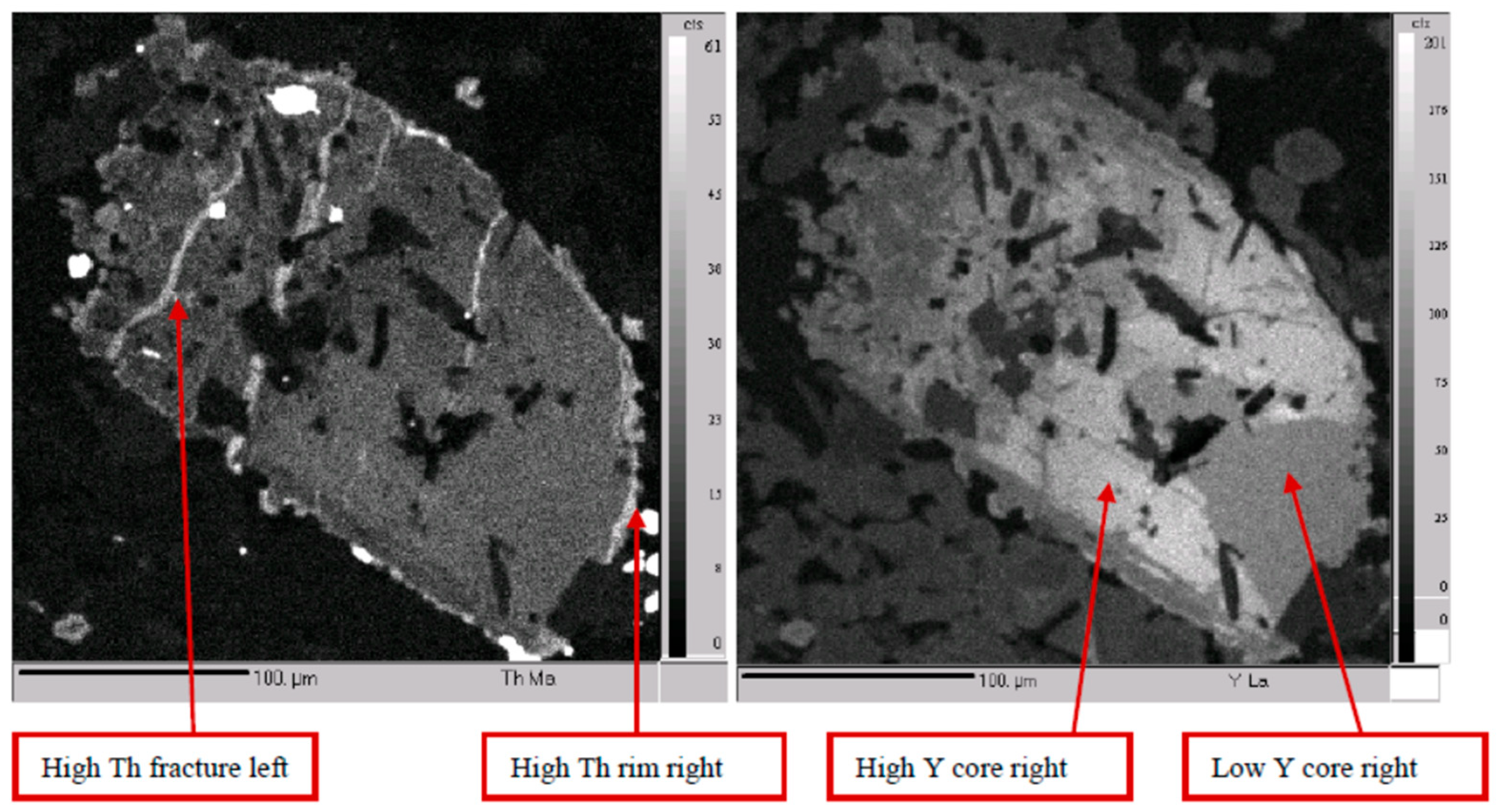

3.3. Monazite Chemistry

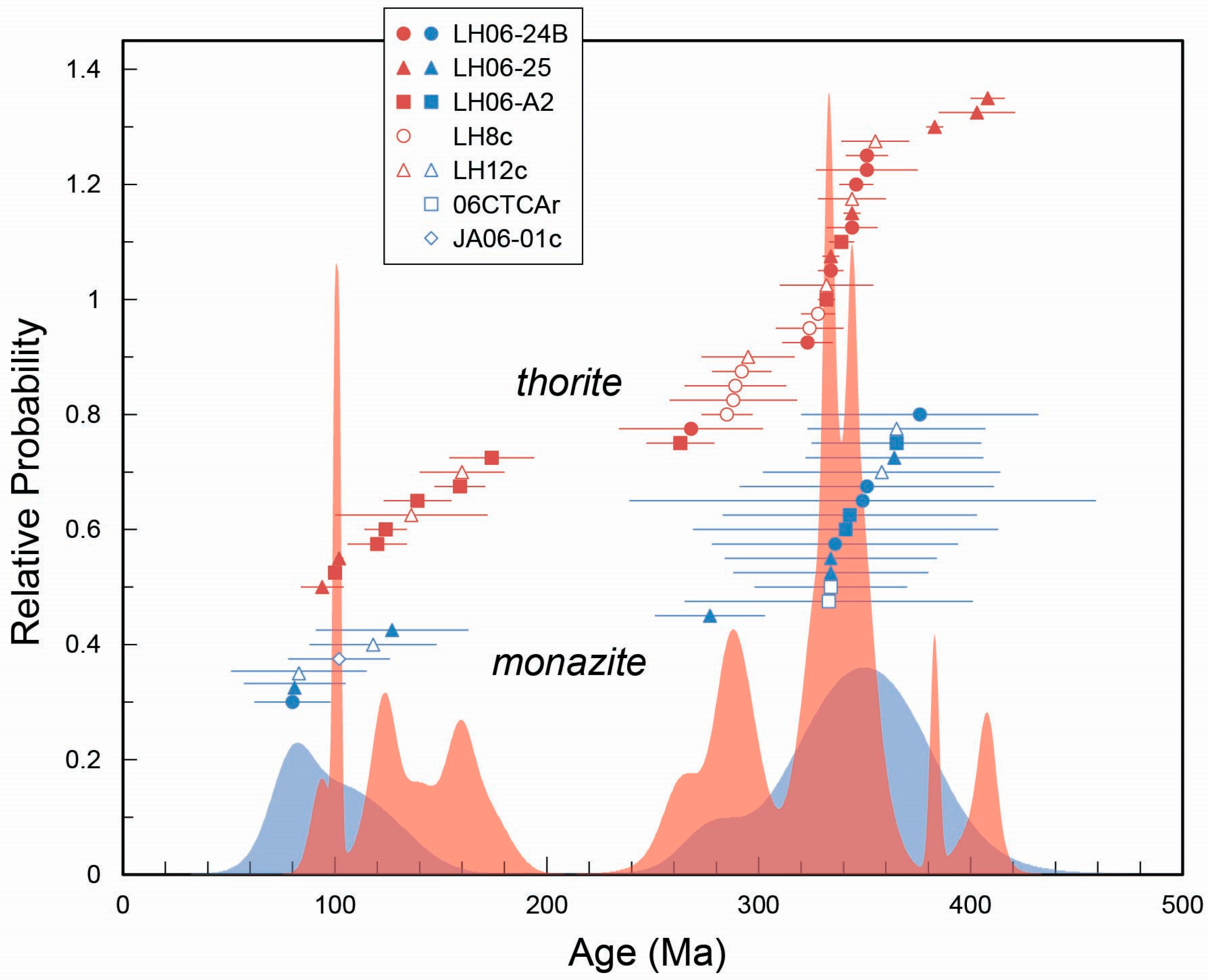

3.4. Monazite and Thorite Geochronology

3.5. Isotopic and Chemical Evidence

3.6. Temperature Estimates and Fluid Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparisons to Other Monazites

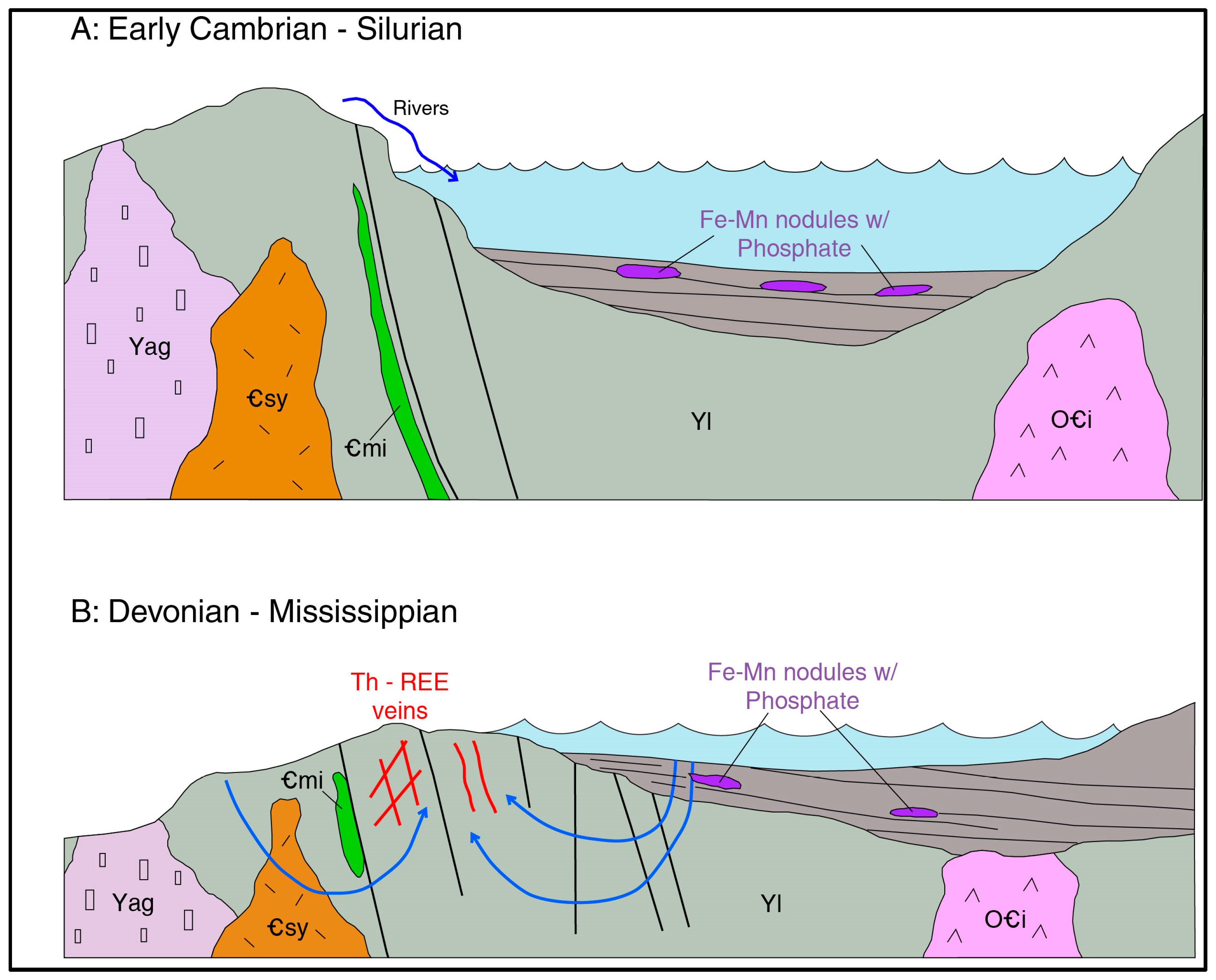

4.2. Genesis of Lemhi Pass Nd-Monazite: Observations and Hypotheses

- Does REE and Th mineralization in this northerly trending belt reflect a zone of metasomatized or enriched mantle and if so, how do later magmatic or hydrothermal events access this zone?

- What is the distribution of rare earth elements in the architecture of the Mesoproterozoic rocks of the region? Only a few multi-element analyses characterize the diverse lithologies of the Lemhi sub-basin metasedimentary units or the regional suite of 1370 Ma megacrystic granites (augen gneiss) and mafic intrusive complex. Likewise, there are few analyses of the Paleozoic magmatic rocks in Lemhi County. If any of these units were indeed sources of rare earths then how much, if any, of the unusual REE fractionation could have been inherited?

- Related to 2 above, what physiochemical processes can account for the unusual fractionation of Nd (enriched), La and Ce (depleted) relative to more typical igneous or metamorphic monazite? Has supergene (or hypogene) oxidation (common at Lemhi Pass) affected the REE distributions? Some of the most relevant variables, such as oxygen fugacity, salinity, iron content, and relatively high temperature, can be deduced from the geologic characteristics of the district, though additional alteration mapping, isotopic, geochemical, mineralogic, and fluid inclusion work is needed, as well as experimental laboratory work.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, A.L. Thorium Mineralization in the Lemhi Pass Area, Lemhi County, Idaho. Econ. Geol. 1961, 56, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staatz, M.H.; Shaw, V.E.; Wahlberg, J.S. Occurrence and Distribution of Rare Earths in the Lemhi Pass Thorium Veins, Idaho and Montana. Econ. Geol. 1972, 67, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staatz, M.H. Geology and Mineral Resources of the Lemhi Pass Thorium District, Idaho and Montana. In U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1049-A; Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1979; p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Zi, J.-W.; Muhling, J.R.; Rasmussen, B. Geochemistry of Low-Temperature (<350 °C) Metamorphic and Hydrothermal Monazite. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 249, 104668. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A.L. Uranium, Thorium, Columbium, and Rare Earth Deposits in the Salmon Region, Lemhi County, Idaho. Ida. Bur. Mines Geol. Pam. 1958, 115, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, W.N.; Cavender, W.S. Geology and Thorium-Bearing Deposits of the Lemhi Pass Area, Lemhi County, Idaho, and Beaverhead County, Montana. In U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1962; Volume 1126, p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gosen, B.S.; Gillerman, V.S.; Armbrustmacher, T.J. Thorium Deposits of the United States—Energy Resources for the Future? U.S. Geological Survey Circular: Reston, VA, USA, 2009; Volume 1336, p. 22.

- Gillerman, V.S. Rare Earth Elements and Other Critical Metals in Idaho. Ida. Geol. Surv. GeoNote 2011, 44, 4. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries; U.S. Geological Survey Circular: Reston, VA, USA, 2025; p. 212.

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1252 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 April 2024, Secure and Sustainable Supply of Critical Raw Materials. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1252/oj (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Reich, M.; Simon, A.C. Critical Minerals. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2025, 53, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanck, P.; Mariano, A.N.; Mariano, A., Jr. Rare Earth Element Ore Geology of Carbonatites. In Rare Earth and Critical Elements in Ore Deposits; Reviews in Economic Geology 18; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, CO, USA, 2016; Volume 18, pp. 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, C.N. Economic Geology of Central Idaho Blacksand Placers. Ida. Bur. Mines Geol. Bull. 1961, 17, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Gillerman, V.S. Geochronology of Iron Oxide-Copper-Thorium-REE Mineralization in Proterozoic Rocks at Lemhi Pass, Idaho, and a Comparison to Copper-Cobalt Ores, Blackbird Mining District, Idaho. In U.S. Geological Survey MRERP Report 06HQGR0170; U.S. Geological Survey Circular: Reston, VA, USA, 2008; p. 148. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/media/files/mrerp-report-06hqgr0170 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Gillerman, V.S.; Schmitz, M.D.; Jercinovic, M.J.; Reed, R. Cambrian and Mississippian Magmatism Associated with Neodymium-Enriched Rare Earth and Thorium Mineralization, Lemhi Pass District, Idaho. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Programs 2010, 42, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Burmester, R.F.; Othberg, K.L.; Stanford, L.R.; Lewis, R.S.; Lonn, J.D. Geologic Map of the Agency Creek Quadrangle, Lemhi County, Idaho. In Idaho Geological Survey DWM-182; Idaho Geological Survey, University of Idaho: Moscow, ID, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Burmester, R.F.; Mosolf, J.; Stanford, L.R.; Lewis, R.S.; Othberg, K.L.; Lonn, J.D. Geologic Map of the Lemhi Pass Quadrangle, Lemhi County, Idaho, and Beaverhead County, Montana. In Idaho Geological Survey DWM-183; Idaho Geological Survey, University of Idaho: Moscow, ID, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gillerman, V.S.; Otto, B.R.; Griggs, F.S. Site Inspection Report for the Abandoned and Inactive Mines in Idaho on U.S. Bureau of Land Management Property in the Lemhi Pass Area, Lemhi County, Idaho. In Idaho Geological Survey Staff Report S-06-04; University of Idaho: Moscow, ID, USA, 2006; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Be Mezeme, E.; Cocherie, A.; Faure, M.; Legendre, O.; Rossi, P. Electron Microprobe Monazite Geochronology of Magmatic Events: Examples from Variscan Migmatites and Granitoids, Massif Central, France. Lithos 2006, 87, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, B.; Fletcher, I.R.; Muhling, J.R. In Situ U-Pb Dating and Element Mapping of Three Generations of Monazite: Unravelling Cryptic Tectonothermal Events in Low-Grade Terranes. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 2007, 71, 670–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Jercinovic, M.J.; Hetherington, C.J. Microprobe Monazite Geochronology: Understanding Geologic Processes through Integration of Composition and Chronology. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2007, 37, 137–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Jercinovic, M.J.; Mahan, K.H.; Dumond, G. Electron Microprobe Petrochronology. Mineral. Soc. Am. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2017, 83, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jercinovic, M.J.; Williams, M.L.; Lane, E.D. In-Situ Trace Element Analysis of Monazite and Other Fine-Grained Accessory Minerals by EPMA. Chem. Geol. 2008, 254, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottle, J.M. In Situ U-Th/Pb Geochronology of (Urano)Thorite. Am. Mineral. 2014, 99, 1985–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jercinovic, M.J.; Williams, M.L. Analytical Perils (and Progress) in Electron Microprobe Trace Element Analysis Applied to Geochronology: Background Acquisition, Interferences, and Beam Irradiation Effects. Am. Mineral. 2005, 90, 526–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.R.; Chakoumakos, B.C. Chemistry and Radiation Effects of Thorite-Group Minerals from the Harding Pegmatite, Taos County, New Mexico. Am. Mineral. 1988, 73, 1405–1419. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.L.; Jercinovic, M.J.; Goncalves, P.; Mahan, K. Format and Philosophy for Collecting, Compiling, and Reporting Microprobe Monazite Ages. Chem. Geol. 2006, 225, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancey, M.; Bastenaire, F.; Tixier, R. Applications of Statistical Methods in Microanalysis. In Microanalysis and Scanning Electron Microscopy; Les Editions de Physique: Paris, France, 1978; pp. 319–343. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, P.E. Origin of the Lemhi Pass REE-Th Deposits, Idaho/Montana: Petrology, Mineralogy, Paragenesis, Whole Rock Chemistry and Isotope Evidence. Master’s Thesis, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA, 1998; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, W.B. The Tendoy Copper Queen Mine. Master’s Thesis, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Long, K.R.; Van Gosen, B.S.; Foley, N.K.; Cordier, D. The Principal Rare Earth Elements Deposits of the United States—A Summary of Domestic Deposits and a Global Perspective. In U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010-5220; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, P.; Wood, S.A. Geochemistry and Mineralogy of the Lemhi Pass Th-REE Deposits. In Mineral Deposits: Research and Exploration; Fourth Biennial SGA Meeting; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 945–948. [Google Scholar]

- Idaho Strategic Resources Idaho Strategic’s Lemhi Trenching Returns up to 5% Total Rare Earths—Including Magnet REE Concentrations in Excess of 70%. Available online: https://idahostrategic.com/idaho-strategics-lemhi-trenching-returns-up-to-5-total-rare-earths-including-magnet-ree-concentrations-in-excess-of-70/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Murchland, M.; Williams, T.J.; Lewis, R.S.; Gillerman, V.S.; Steven, C. Investigating Carbonatites and Rare Earth Mineralization in Lemhi County, Idaho. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Programs 2023, 55, 393780. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The Continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution; Blackwell Scientific: Oxford, UK, 1985; p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, K.V.; Green, G.N. Geologic Map of the Salmon National Forest and Vicinity, East-Central Idaho. In U.S. Geological Survey Map I-2765; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gillerman, V.S.; Schmitz, M.D.; Jercinovic, M.J. REE-Th Deposits of the Lemhi Pass Region, Northern Rocky Mountains—Paleozoic Magmas and Hydrothermal Activity along a Continental Margin. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Programs 2013, 45, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Gillerman, V.S.; Schmitz, M.D.; Jercinovic, M.J. Copper and REE-Th Metallogeny in Lemhi County, Idaho: Magmatism and Repeated Hydrothermal Activity along a Paleozoic Continental Margin. In Proceedings of the Society of Economic Geologists 2013 Conference Abstracts and e-Posters; Society of Economic Geologists: Whistler, BC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, C.D.; Winston, D. Nd Isotope Systematics of Coarse- and Fine-Grained Sediments: Examples from the Middle Proterozoic Belt-Purcell Supergroup. J. Geol. 1987, 95, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaschnig, R.M.; Vervoort, J.D.; Lewis, R.S.; Tikoff, B. Isotopic Evolution of the Idaho Batholith and Challis Intrusive Province, Northern US Cordillera. J. Petrol. 2011, 52, 2397–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, G.K. Fluid Inclusion Evidence for the Temperature and Composition of Ore Fluids in the Lemhi Pass and Diamond Creek REE-Th Districts, Idaho-Montana. Master’s Thesis, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO, USA, 2019; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- May, R.A. Geochemical Evidence for the Origin of Th-REE Mineralization in the Lemhi Pass District, Idaho/Montana. Master’s Thesis, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO, USA, 2024; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, E.K.; Watts, K.E. Apatite and Monazite Geochemistry Record Magmatic and Metasomatic Processes in Rare Earth Element Mineralization at Mountain Pass, California. Econ. Geol. 2024, 119, 1611–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeser, S.; Schwander, H. Gasparite-(Ce) and Monazite-(Nd): Two New Minerals to the Monazite Group from the Alps. Schweiz. Mineral. Petrogr. Mitteilungen 1987, 67, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Laval, M. Properties and Geology of Grey Monazite: A Possible New Resource of REE. In Special Volume 50; Canadian Institute of Mining: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1998; Volume 50, pp. 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Schandl, E.S.; Gorton, M.P. A Textural and Geochemical Guide to the Identification of Hydrothermal Monazite: Criteria for Selection of Samples for Dating Epigenetic Hydrothermal Ore Deposits. Econ. Geol. 2004, 99, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardak, D.; Pieczka, A.; Kotowski, J.; Nejbert, K. Mineral Chemistry and Genesis of Monazite-(Sm) and Monazite-(Nd) from the Blue Beryl Dyke of the Julianna Pegmatite System at Pilawa Gorna, Lower Silesia, Poland. Mineral. Mag. 2023, 87, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janots, E.; Berger, A.; Gnos, E.; Whitehouse, M.; Lewin, E.; Pettke, T. Constraints on Fluid Evolution during Metamorphism from U-Th-Pb Systematics in Alpine Hydrothermal Monazite. Chem. Geol. 2012, 326, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusiak, M.A.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, I. Nd-Monazite Occurrence in North America: Mesoproterozoic Siliciclastic Rocks of the Belt-Purcell Supergroup. Proc. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 2006, 70, A338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Alvarez, I.; Kusiak, M.A.; Kerrich, R. A Trace Element and Chemical Th-U Total Pb Dating Study in the Lower Belt-Purcell Supergroup, Western North America: Provenance and Diagenetic Implications. Chem. Geol. 2006, 230, 140–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, G.P.; Hofstra, A.H. Ore Genesis Constraints on the Idaho Cobalt Belt from Fluid Inclusion Gas, Noble Gas Isotope, and Ion Ratio Analyses. Econ. Geol. 2012, 107, 1189–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillerman, V.S.; Schmitz, M.D.; Jercinovic, M.J. Nd-Enriched Lemhi Pass REE-Th District, Idaho-Montana: A Link between Crustal Hydrothermal Circulation and Devonian-Carboniferous Marine Environments? Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Programs 2021, 53, 365142. [Google Scholar]

- Emsbo, E.; McLaughlin, P.I.; du Bray, E.A.; Anderson, E.; Vandenbrouchke, T.; Zielinski, R.A. Rare Earth Elements in Sedimentary Phosphorite Deposits: A Global Assessment. In Rare Earth and Critical Elements in Ore Deposits; Reviews in Economic Geology 18; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, CO, USA, 2016; Volume 18, pp. 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Emsbo, P.; McLaughlin, P.I.; Breit, G.N.; du Bray, E.A.; Koenig, A.E. Rare Earth Elements in Sedimentary Phosphate Deposits: Solution to the Global REE Crisis? Gondwana Res. 2015, 27, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, K.; Aleinikoff, J.N.; Evans, K.V.; Dubray, E.A.; Dewitt, E.H.; Unruh, D.M. SHRIMP U-Pb Dating of Recurrent Cryogenian and Late Cambrian–Early Ordovician Alkalic Magmatism in Central Idaho: Implications for Rodinian Rift Tectonics. GSA Bull. 2010, 122, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.D.; Pearson, D.M. Field Guide to Carbonate Mylonites and Reactivated Basement Faults of the Leadore Area. Northwest Geol. 2023, 52, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dostal, J. Rare Metal Deposits Associated with Alkaline/Peralkaline Igneous Rocks. In Rare Earth and Critical Elements in Ore Deposits; Reviews in Economic Geology 18; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, CO, USA, 2016; Volume 18, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chakhmouradian, A.R.; Zaitsev, A.N. Rare Earth Mineralization in Igneous Rocks: Sources and Processes. Elements 2012, 8, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, A.N.; Mariano, A., Jr. Rare Earth Mining and Exploration in North America. Elements 2012, 8, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, O.; Stevenson, R.; Jébrak, M. Evolution of Montviel Alkaline–Carbonatite Complex by Coupled Fractional Crystallization, Fluid Mixing and Metasomatism—Part I: Petrography and Geochemistry of Metasomatic Aegirine–Augite and Biotite: Implications for REE–Nb Mineralization. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 72, 1143–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, P.H.; Sturmer, D.M. The Antler Orogeny Reconsidered and Implications for Late Paleozoic Tectonics of Western Laurentia. Geology 2023, 51, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trexler, J.H., Jr.; Cashman, P.H.; Cole, J.C.; Snyder, W.S.; Tosdal, R.M.; Davydov, V.I. Widespread Effects of Middle Mississippian Deformation in the Great Basin of Western North America. GSA Bull. 2003, 115, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trexler, J.H., Jr.; Cashman, P.H.; Snyder, W.S.; Davydov, V.I. Late Paleozoic Tectonism in Nevada: Timing, Kinematics, and Tectonic Significance. GSA Bull. 2004, 116, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Jones, A.E.; Migdisov, A.A.; Samson, I.M. Hydrothermal Mobilisation of the Rare Earth Elements—A Tale of “Ceria” and “Yttria”. Elements 2012, 8, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, K. Geometry of the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic Rift Margin of Western Laurentia: Implications for Mineral Deposit Settings. Geosphere 2008, 4, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Th | U | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monazite | 58 | 30 | 25 |

| Thorite | 755 | 91 | 116 |

| Element | Lucky Horseshoe, Lemhi Pass (LH06-24B) | Roberts Carbonatite, Mineral Hill (07WP127B) | Syenite, Lemhi Pass (JA06-01) |

|---|---|---|---|

| La | 658 | 87,500 | 180 |

| Ce | 4920 | 113,000 | 325 |

| Pr | 1430 | 9950 | 39 |

| Nd | 8350 | 23,300 | 119 |

| Sm | 1220 | 1300 | 20 |

| Eu | 165 | 210 | 3 |

| Gd | 448 | 208 | 16 |

| Tb | 24 | 16 | 3 |

| Dy | 60 | 66 | 14 |

| Ho | 9 | 11 | 3 |

| Er | 29 | 34 | 9 |

| Tm | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Yb | 7 | 14 | 9 |

| Lu | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Th | 2510 | 2810 | 33 |

| U | 18 | 11 | 7 |

| TREE | 17,320 | 235,614 | 741 |

| Ce/Nd | 0.59 | 4.85 | 2.73 |

| Monazite Sample (Wt. %) | LH12c2 | LH06-24A | LH-8a | LH-12 | LH12c M2 Low Th | LH12cM2 High Th | LH06-25 M3 High Y Core | LH06-25 M3 High Th Fracture | Sunshine Lode | Roberts S (07WP127B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y2O3 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 1.38 | 0.61 | 1.09 | 0.03 |

| La2O3 | 3.40 | 2.77 | 3.44 | 3.63 | 3.68 | 3.49 | 2.42 | 2.95 | 13.89 | 25.18 |

| Ce2O3 | 16.19 | 15.16 | 16.25 | 16.67 | 16.87 | 16.42 | 14.28 | 15.77 | 31.39 | 32.87 |

| Pr2O3 | 5.44 | 5.50 | 5.50 | 5.58 | 5.03 | 5.02 | 4.94 | 5.13 | 4.23 | 4.10 |

| Nd2O3 | 34.94 | 36.59 | 36.38 | 35.17 | 34.77 | 35.10 | 35.78 | 35.46 | 12.86 | 6.71 |

| Sm2O3 | 5.01 | 5.08 | 4.77 | 4.89 | 2.94 | 2.93 | 4.24 | 3.76 | 2.40 | 0.30 |

| Eu2O3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.21 | 1.18 | 1.47 | 1.34 | NA | NA |

| Gd2O3 | 1.43 | 1.32 | 1.40 | 1.52 | 1.56 | 1.61 | 2.08 | 1.84 | 2.14 | 0.58 |

| ThO2 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 1.84 | 0.50 | 1.81 | 0.26 | 0.65 |

| UO2 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

| PbO | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.09 |

| CaO | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| SiO2 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.00 |

| Al2O3 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.24 | 0.00 |

| P2O5 | 29.29 | 29.13 | 29.49 | 29.49 | 28.87 | 28.96 | 29.60 | 29.83 | 29.87 | 30.49 |

| Oxide Totals | 98.05 | 97.57 | 98.94 | 98.90 | 97.98 | 98.81 | 98.08 | 99.87 | 99.19 | 101.17 |

| TREO (La-Gd) | 66.40 | 66.41 | 67.73 | 67.48 | 66.07 | 65.74 | 65.20 | 66.26 | 66.91 | 69.73 |

| t | [Sm] | [Nd] | 147Sm | 143Nd | ƒ | Epsilon | Epsilon | tDM (Ga) | tDM (Ga) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | (Ga) | ppm | ppm | 144Nd | 144Nd | ±2 s [abs] | Sm/Nd | Nd (0) | Nd (t) | 1-Stage | 2-Stage |

| Monazite | |||||||||||

| M15 | 0.355 | 42,484 | 293,198 | 0.0876 | 0.512312 | 0.000005 | −0.5547 | −6.36 | −1.90 | 1.01 | 1.35 |

| MB2 | 0.355 | 44,610 | 306,083 | 0.0881 | 0.512318 | 0.000007 | −0.5521 | −6.24 | −1.81 | 1.01 | 1.34 |

| MA3 | 0.355 | 57,837 | 420,601 | 0.0831 | 0.512288 | 0.000015 | −0.5774 | −6.83 | −2.19 | 1.01 | 1.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gillerman, V.S.; Jercinovic, M.J.; Schmitz, M.D. Neodymium-Rich Monazite of the Lemhi Pass District, Idaho and Montana: Chemistry and Geochronology. Minerals 2025, 15, 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111156

Gillerman VS, Jercinovic MJ, Schmitz MD. Neodymium-Rich Monazite of the Lemhi Pass District, Idaho and Montana: Chemistry and Geochronology. Minerals. 2025; 15(11):1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111156

Chicago/Turabian StyleGillerman, Virginia S., Michael J. Jercinovic, and Mark D. Schmitz. 2025. "Neodymium-Rich Monazite of the Lemhi Pass District, Idaho and Montana: Chemistry and Geochronology" Minerals 15, no. 11: 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111156

APA StyleGillerman, V. S., Jercinovic, M. J., & Schmitz, M. D. (2025). Neodymium-Rich Monazite of the Lemhi Pass District, Idaho and Montana: Chemistry and Geochronology. Minerals, 15(11), 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111156