Mineralogy of Dolomite Carbonatites of Sevathur Complex, Tamil Nadu, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Materials and Methods

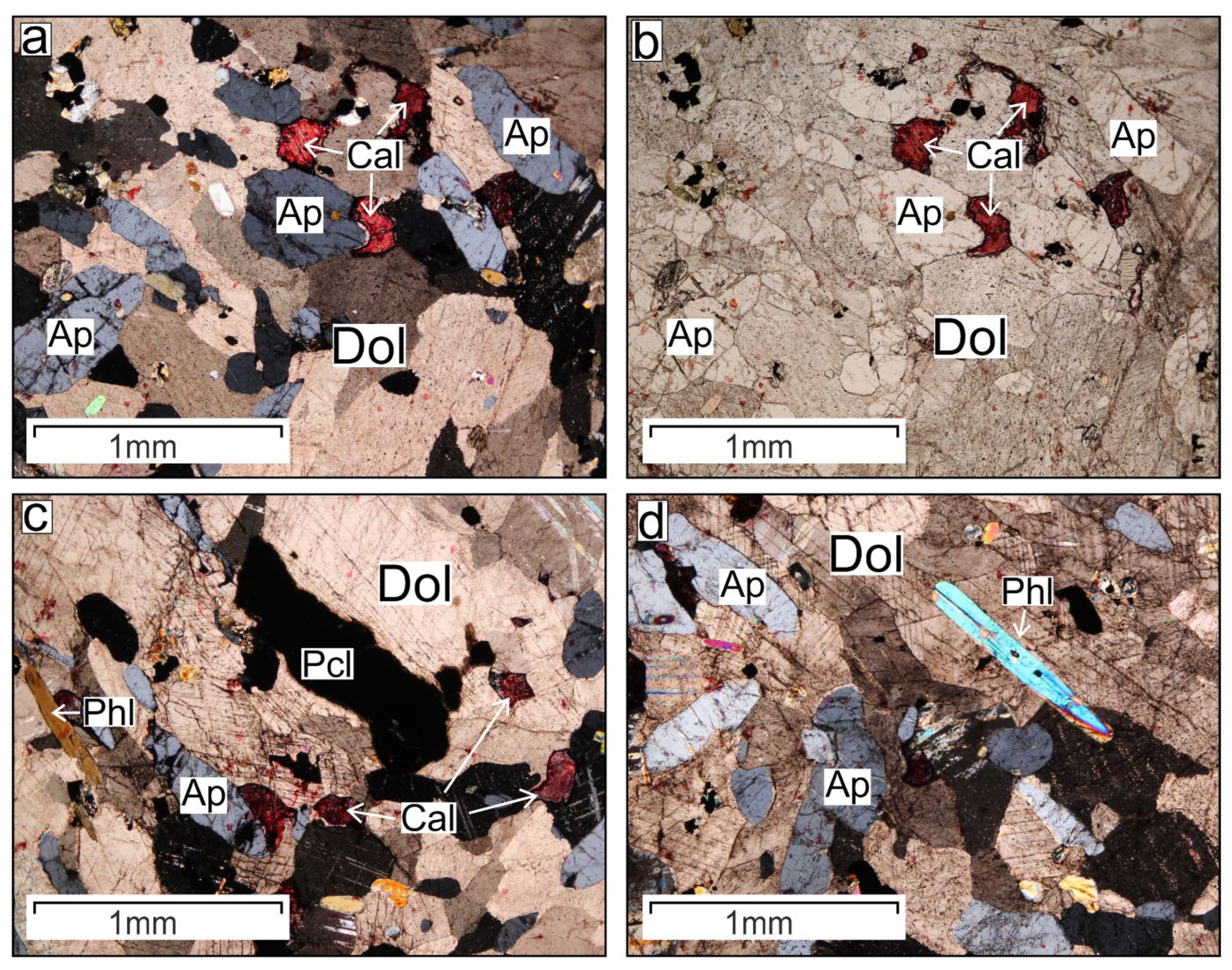

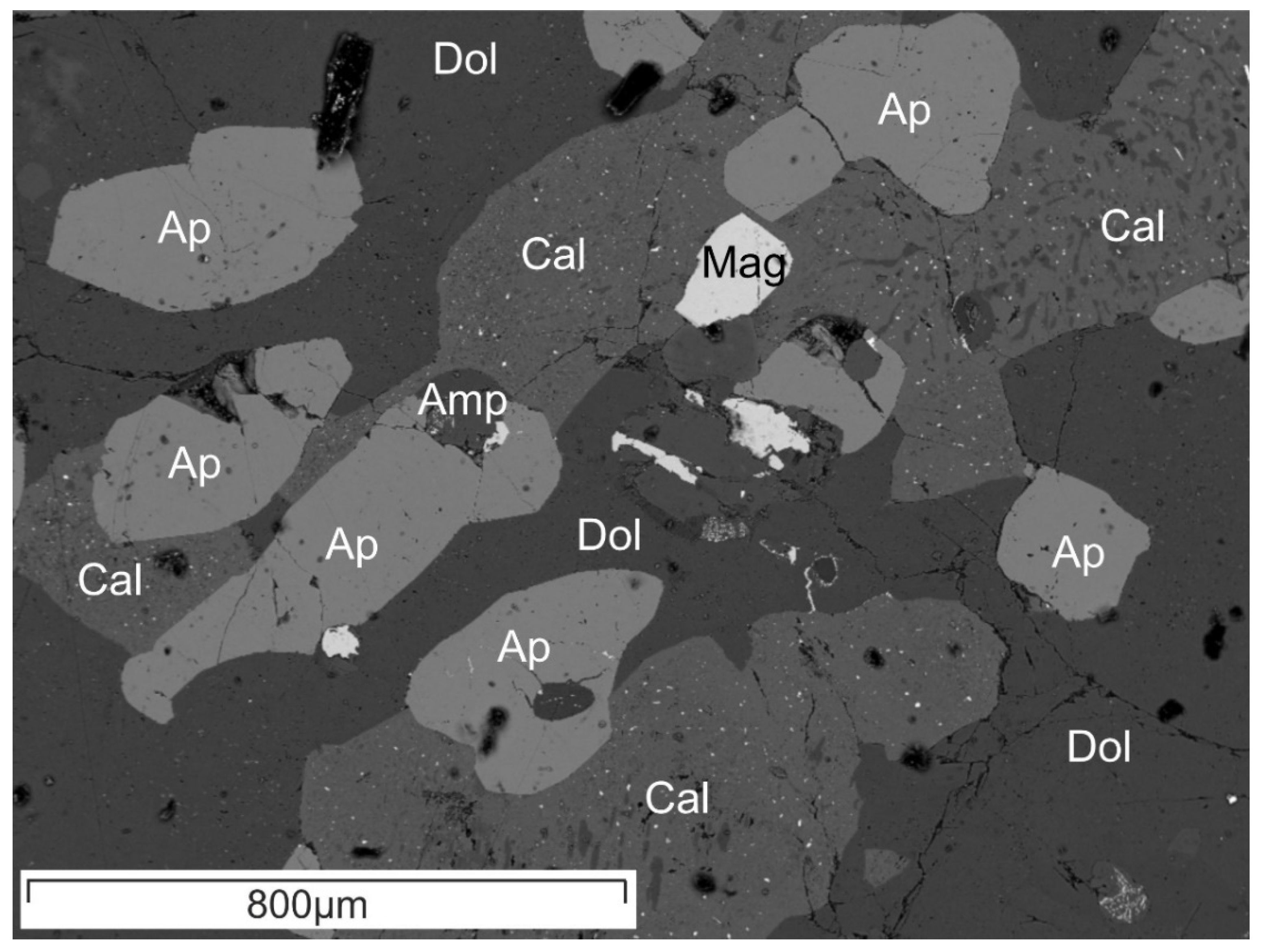

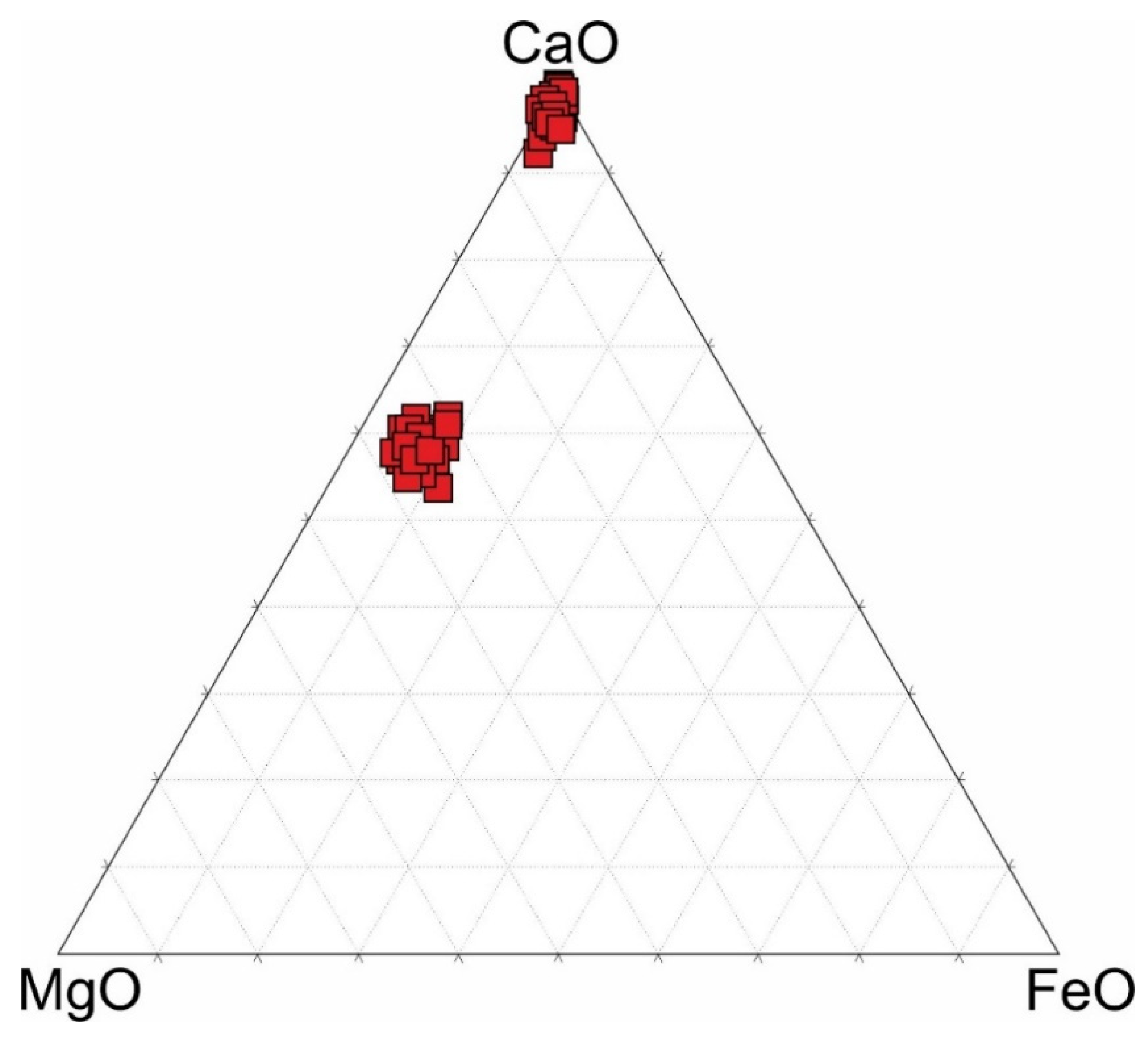

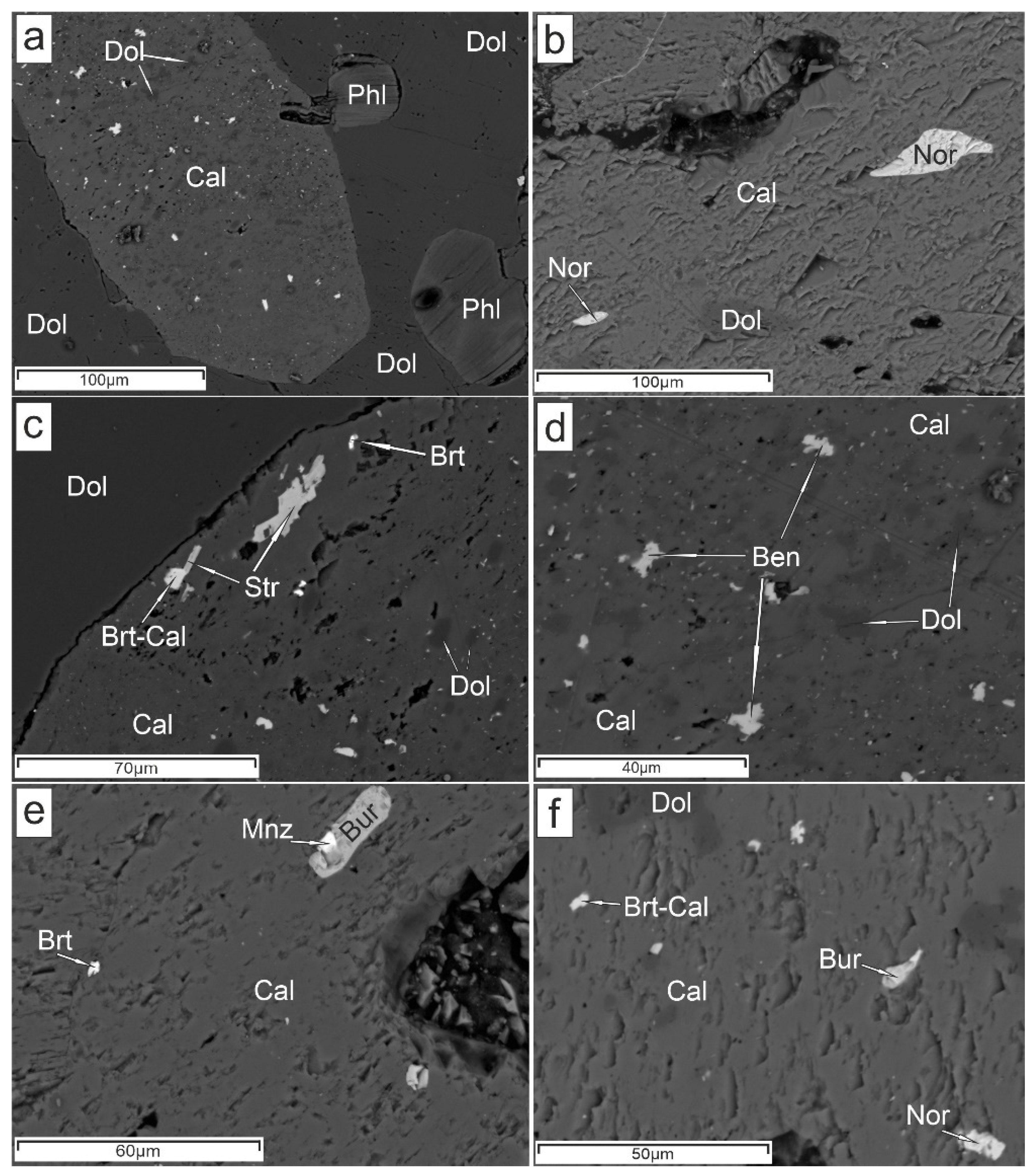

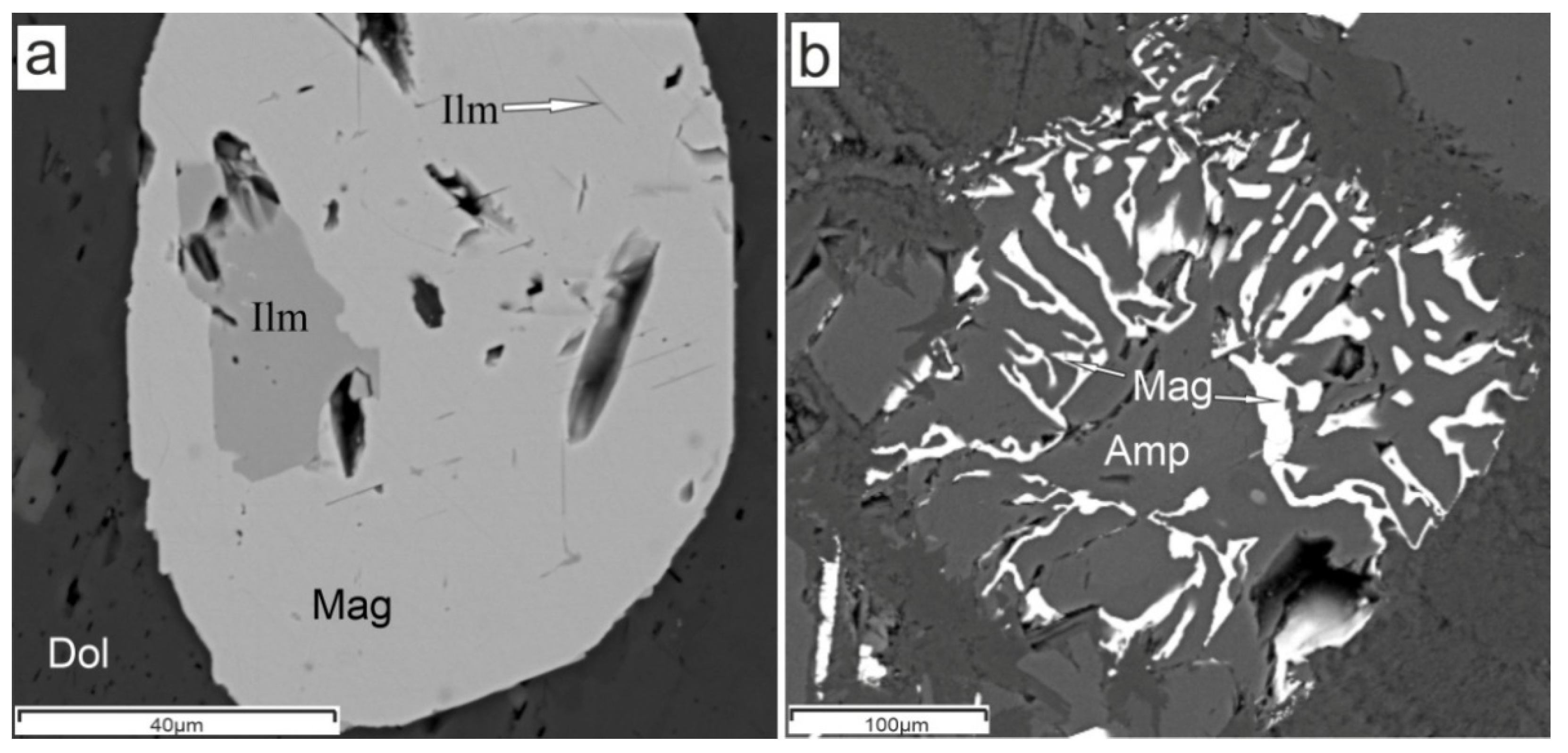

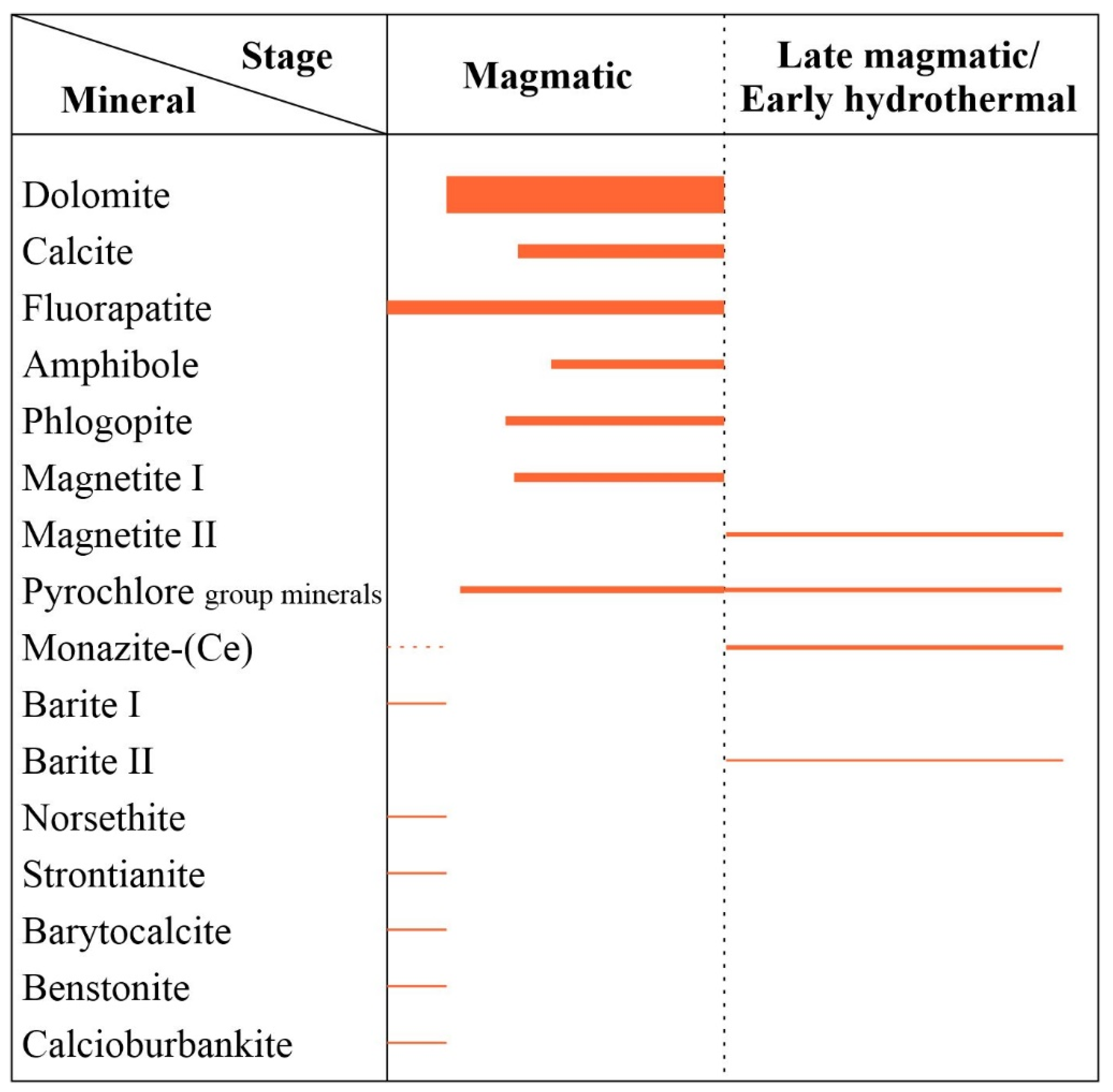

4. Results

5. Discussion

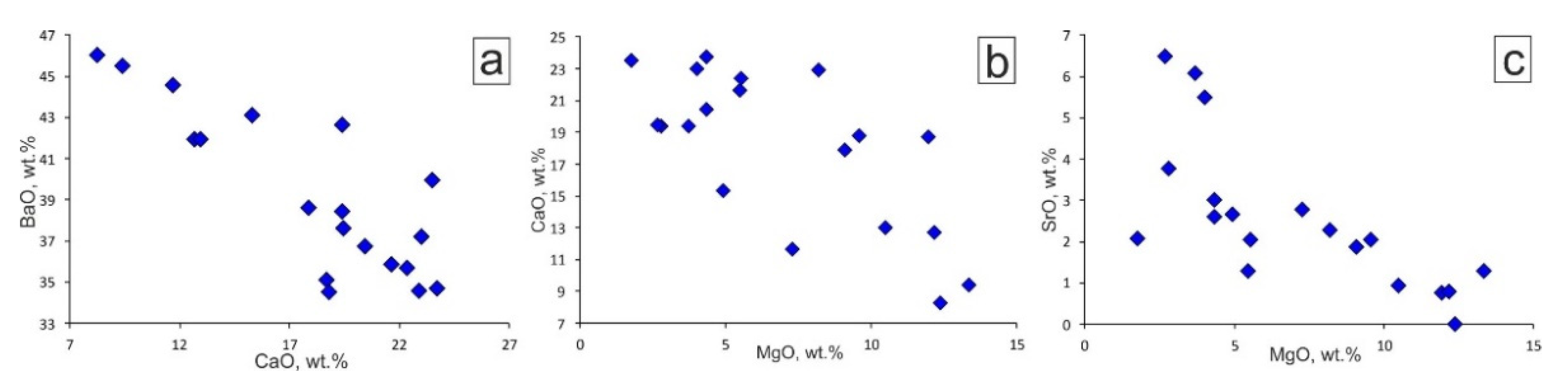

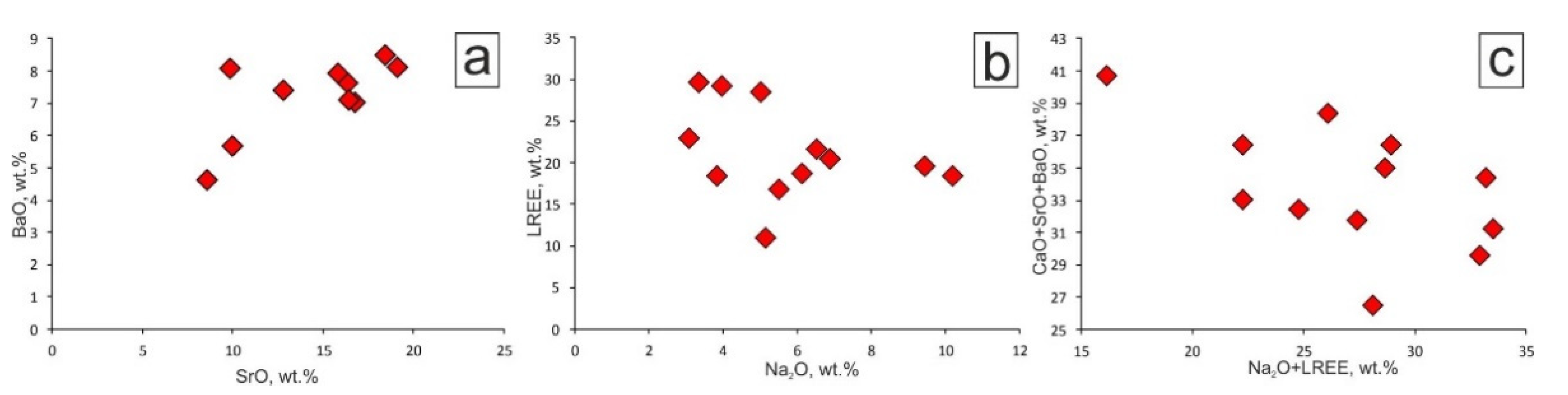

5.1. Genesis of Ba-Mg-Sr-REE-Carbonates

5.2. Hydrothermal Alteration of U-Rich Pyrochlores

5.3. Composition of Hydrothermal Fluids

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Le Maitre, R.W.; Streckeisen, A.; Zanettin, B.; Le Bas, M.J.; Bonin, B.; Bateman, P.; Bellieni, G.; Dudek, A.; Efremova, S.; Keller, J.; et al. Igneous Rocks: A Classification and Glossary of Terms. Recommendations of the International Union of Geological Sciences Subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks, 2nd ed.; Le Maitre, R.W., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 9780521619486. [Google Scholar]

- Borodin, L.S.; Gopal, V.; Moralev, V.M.; Subramanian, V. Precambrian carbonatites of Tamil Nadu, South India. J. Geol. Soc. India 1971, 12, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, J.C. Deep main faults in South India. J. Geol. Soc. India 1971, 12, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Randive, K.; Meshram, T. An Overview of the carbonatites from the Indian subcontinent. Open Geosci. 2020, 12, 85–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, H.; Todt, W.; Viladkar, S.G.; Schmidt, F. Pb/Pb age determinations on Newania and Sevathur carbonatites of India: Evidence for multi-stage histories. Chem. Geol. 1997, 140, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viladkar, S.G.; Subramanian, V. Mineralogy and geochemistry of the carbonatites of the Sevathur and Samalpatti complexes, Tamil Nadu. J. Geol. Soc. India 1995, 45, 505–517. [Google Scholar]

- Viladkar, S.G.; Bismayer, U. U-rich pyrochlore from Sevathur carbonatites, Tamil Nadu. J. Geol. Soc. India 2014, 83, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viladkar, S.G.; Wimmenauer, W. Mineralogy and geochemistry of the Newania carbonatite-fenite complex, Rajasthan, India. N. Jb. Miner. Abh. 1986, 156, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, J.R.; Graf, D.L.; Witters, J.; Northrop, D.A. Studies in the synthetic CaCO3-MgCO3-FeCO3: 1. Phase relations; 2. A method for major-element spectrochemical analysis; 3. Compositions of some ferrian dolomites. J. Geol. 1962, 70, 659–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.H. Kimberlite, Orangeites and Related Rocks; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; 410p. [Google Scholar]

- Kogarko, L.N.; Ryabchikov, I.D.; Kuzmin, D.V. High-Ba mica in olivinites of the Guli massif (Maymecha–Kotuy province, Siberia). Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2012, 53, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshkevich, A.G.; Chebotarev, D.A.; Sharygin, V.V.; Prokopyev, I.R.; Nikolenko, A.M. Petrology of alkaline silicate rocks and carbonatites of the Chuktukon massif, Chadobets upland, Russia: Sources, evolution and relation to the Triassic Siberian LIP. Lithos 2019, 332–333, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, R.J.; Marks, M.A.W.; Gauert, C.D.K.; Markl, G. A model for the formation of carbonatite-phoscorite assemblages based on the compositional variations of mica and apatite from the Palabora Carbonatite Complex, South Africa. Lithos 2019, 324–325, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogarko, L.N.; Kurat, G.; Ntaflos, T. Henrymeyerite in the metasomatized upper mantle of eastern Antarctica. Can. Mineral. 2007, 45, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atencio, D.; Andrade, M.B.; Christy, A.G.; Giere, R.; Kartashov, P.M. The pyrochlore supergroup of minerals: Nomenclature. Can. Mineral. 2010, 48, 673–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrose, M.E.; Chao, E.C.T.; Fahey, J.J.; Milton, C. Norsethite, BaMg(CO3)2, a new mineral from the Green River formation, Wyoming. Am. Mineral. 1961, 46, 420–429. [Google Scholar]

- Sundius, N.; Blix, R. Norsethite from Lengban. Arkiv. Mineral. Geol. 1965, 4, 277–278. [Google Scholar]

- Steyn, J.G.D.; Watson, M.D. Note on a new occurrence of norsethite, BaMg(CO3)2. Amer. Miner. 1967, 52, 1770–1775. [Google Scholar]

- Onac, B.P. Caves formed within Upper Cretaceous skarns at Baita, Bihor County, Romania: Mineral deposition and speleogenesis. Can. Miner. 2002, 40, 1693–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidarov, N.; Petrov, O.; Tarassov, M.; Damyanov, Z.; Tarassova, E.; Petkova, V.; Kalvachev, Y.; Zlatev, Z. Mn-rich norsethite from the Kremikovtsi ore deposit, Bulgaria. N. Jb. Miner. Abh. 2009, 186, 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Kapustin, J.L. Norsethite—The first find in USSR. Doklady Acad. Nauk USSR 1965, 161, 922–924. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, E.; Fomina, E.; Sidorov, M.; Shilovskikh, V.; Bocharov, V.; Chernyavsky, A.; Huber, M. The petyayan-vara carbonatite-hosted rare earth deposit (Vuoriyarvi, NW Russia): Mineralogy and geochemistry. Minerals 2020, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, R.G.; Woolley, A.R. The carbonatites and fenites of Chipman lake, Ontario. Can. Miner. 1990, 28, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Secco, L.; Lavina, L. Crystal chemistry of two natural magmatic norsethites, BaMg(CO3)2, from an Mg-carbonatites of the alkaline carbonatitic complex of Tapira (SE Brazil). N. Jb. Miner. Mh. 1999, 2, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lippman, F. Benstonite, Ca7Ba6(CO3)l3, a new mineral from barite deposits in Hot Spring County, Arkansas. Amer. Miner. 1962, 47, 585–598. [Google Scholar]

- Sundius, N. Benstonite and tephroite from Longban. Ark. Miner. Geol. 1963, 3, 407–411. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.S., Jr.; Jarosewich, E. Second occurrence of benstonite. Miner. Rec. 1970, 1, 140–141. [Google Scholar]

- Finlow-Bates, T. The possible significance of uncommon barium-rich mineral assemlages in sediment-hosted lead-zinc deposits. Geol. Mijnbouw. 1987, 66, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Semenov, E.; Gopal, V.; Subramaian, V. Note on the occurrence of benstonite. Surr. Sci. 1971, 40, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vladykin, N.V.; Viladkar, S.G.; Miyazaki, T.; Mohan, R.V. Geochemistry of benstonite and associated carbonatites of Sevathur, Jogipatti and Samalpatti, Tamil Nadu, South India and Murun massif, Siberia. J. Geol. Soc. India 2008, 72, 312–324. [Google Scholar]

- Ontoyev, D.O.; Dmitrieva, M.T.; Ontoeva, T.D. About strontium variety of benstonite. Zap. Ross. Mineral. O-va 1986, 4, 496–501. [Google Scholar]

- Konev, A.A.; Kartashev, P.M.; Koneva, A.A.; Ushchapovskaya, Z.F.; Nartova, N.V. Mg-deficient strontium benstonite from the ore occurrence Biraya (Siberia). Zap. Ross. Mineral. O-va 2004, 133, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Belovitskaya, Y.V.; Pekov, I.V. Genetic mineralogy of the burbankite group. New Data Miner. 2004, 39, 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Van Velthuizen, J.; Gault, R.; Grice, J.D. Calcioburbankite, Na3(Ca,REE,Sr)3(CO3)5, a new mineral species from Mont Saint Hilaire, Quebec, and its relationship to the burbankite group of minerals. Can. Mineral. 1995, 33, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin, V.V.; Voloshin, A.V.; Pakhomovskii, Y.A.; Bakhchisaraitsev, A.Y. Calcioburbankite and burbankite from Vuoriyarvi carbonatite massif (new data). Zap. Ross. Mineral. O-va 1999, 1, 78–87. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Pozharitskaya, L.K.; Samoilov, V.S. Petrology, Mineralogy and Geochemistry of Carbonatites of East Siberia (Petrologiya, Mineralogiyai Geokhimiya Karbonatitov Vostochnoi Sibiri); Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1972; 268p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Khromova, E.A. Age and Petrogenesis of Rocks of the Alkaline-Ultrabasic Carbonatite Belaya Zima Massif (Eastern Sayan); Candidate of Geology, Geological Institute Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Ulan-Ude, Russia, 2020. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.B.; Wyllie, P.J. High-pressure apatite solubility in carbonate-rich liquids: Implications for mantle metasomatism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1992, 56, 3409–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabchikov, I.D.; Hamilton, D.L. Interaction of carbonate-phosphate melts with mantle peridotites at 20–35 kbar. S. Afr. J. Geol. 1993, 96, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev, A.N.; Chakhmouradian, A.R. Calcite-amphiboleclinopyroxene rock from the Afrikanda complex, Kola Peninsula, Russia: Mineralogy and a possible link to carbonatites. II Oxysalt minerals. Can. Mineral. 2002, 40, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, A.N.; Sitnikova, M.A.; Subbotin, V.V.; Fernández-Suárez, J.; Jeffries, T.E. Sallanlatvi complex—A rare example of magnesite and siderite carbonatites. In Phoscorites and Carbonatites from Mantle to Mine; Wall, F., Zaitsev, A.N., Eds.; Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland: London, UK, 2004; pp. 201–245. [Google Scholar]

- Faiziev, A.R.; Iskandarov, F.S.; Gafurov, F.G. Mineralogical and petrogenetic characteristics of carbonatites of Dunkeldykskii alkali massif (eastern Pamirs). Proc. Russ. Mineral. Soc. 1998, 127, 54–57. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tichomirowa, M.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Gerdes, A.; Götze, J.; Schulz, B.; Belyatsky, B.V. Different zircon recrystallization types in carbonatites caused by magma mixing: Evidence from U–Pb dating, trace element and isotope composition (Hf and O) of zircons from two Precambrian carbonatites from Fennoscandia. Chem. Geol. 2013, 353, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhmouradian, A.R.; Reguir, E.P.; Zaitsev, A.N. Calcite and dolomite in intrusive carbonatites. I. Textural variations. Mineral. Petrol. 2016, 110, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhmouradian, A.R.; Dahlgren, S. Primary inclusions of burbankite in carbonatites from the Fen complex, southern Norway. Miner. Petrol. 2021, 115, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puustinen, K. Dolomite exsolution textures in calcite from the Siilinjärvi carbonatite complex, Finland. Bull. Geol. Soc. Finl. 1974, 46, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, A.N.; Polezhaeva, L. Dolomite-calcite textures in early carbonatites of the Kovdor ore deposit, Kola peninsula, Russia: Their genesis and application for calcite-dolomite geothermometry. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1994, 115, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.B.; Hinton, R.W. Trace-element content and partitioning in calcite, dolomite and apatite in carbonatite, Phalaborwa, South Africa. Min. Mag. 2003, 67, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konev, A.A.; Vorob’ev, E.I.; Lazebnik, K.A. Mineralogy of the Murun Alkaline Massif; Siberian Branch Russian Academy of Sciences: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1996; p. 221. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Yaroshevsky, A.A.; Bagdasarov, Y.A. Geochemical diversity of minerals of the pyrochlore group. Geochem. Int. 2008, 46, 1245–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redkin, A.F.; Borodulin, G.P. Pyrochlores as indicators of the uranium bearing potential of magmatic melts. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2010, 432, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, D.D. Pyrochlore, apatite and amphibole: Distinctive minerals in carbonatite. In Carbonatites: Genesis and Evolution; Bell, K., Ed.; Unwin Hyman: London, UK, 1989; pp. 105–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kjarsgaard, K.J.; Mitchell, R.H. Solubility of Ta in the system CaCO3–Ca(OH)2–NaTaO3– NaNbO3 ± F at 0.1 GPa: Implications for the crystallization of pyrochlore-group minerals in carbonatites. Can. Mineral. 2008, 46, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapin, A.V.; Kulikova, I.M. Alteration processes in pyrochlore and their products in weathering crusts of carbonatites. Zap. Ross. Mineral. O-va 1989, 118, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Entin, A.R.; Yeremenko, G.Y.; Tyan, O.A. Stages of alteration of primary pyrochlores. Trans. (Dokaldy) U.S.S.R. Acad. Sci. Earth Sci. Sect. 1993, 320, 236–239. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, E.; Niggli, E.; Van Der Veen, A.H. A hydrated bariumstrontium pyrochlore in a biotite rock from Panda Hill, Tanganyika. Mineral. Mag. 1959, 32, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wambeke, L. Pandaite, baddeleyite and associated minerals from the Bingo niobium deposit, Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Miner. Depos. 1971, 6, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wambeke, L. Kalipyrochlore, a new mineral of the pyrochlore group. Am. Mineral. 1978, 63, 528–530. [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth, D.D.; Williams, C.T.; Jones, P. Primary zoning in pyrochlore group of minerals from carbonatites. Mineral. Mag. 2000, 64, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, D. The pyrochlore group. Am. Mineral. 1977, 62, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bonazzi, P.; Bindi, L.; Zoppi, M.; Capitani, G.C.; Olmi, F. Single-crystal diffraction and transmission electron microscopy studies of “silicified” pyrochlore from Narssarssuk, Julianehaab district, Greenland. Am. Mineral. 2006, 91, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.T.; Wall, F.; Woolley, A.R.; Phillipo, S. Compositional variation in pyrochlore from the Bingo carbonatite, Zaire. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 1997, 25, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasraoui, M.; Bilal, E. Pyrochlores from the Lueshe carbonatite complex (Democratic Republic of Congo): A geochemical record of deferent alteration stages. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2000, 18, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.R.; Ewing, R.C. Geochemical alteration of pyrochlore group minerals: Pyrochlore subgroup. Am. Mineral. 1995, 80, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotarev, D.A.; Doroshkevich, A.G.; Klemd, R.; Karmanov, N.S. Evolution of Nb-mineralization in the Chuktukon carbonatite massif, Chadobets upland (Krasnoyarsk Territory, Russia). Period. Mineral. 2017, 86, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Burtseva, M.V.; Ripp, G.S.; Doroshkevich, A.G.; Viladkar, S.G.; Rammohan, V. Features of mineral and chemical composition of the Khamambettu carbonatites, Tamil Nadu. J. Geol. Soc. India 2013, 81, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopyev, I.R.; Doroshkevich, A.G.; Ponomarchuk, A.V.; Sergeev, S.A. Mineralogy, age and genesis of apatite-dolomite ores at the Seligdar apatite deposit (Central Aldan, Russia). Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 81, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopyev, I.R.; Doroshkevich, A.G.; Sergeev, S.A.; Ernst, R.E.; Ponomarev, J.D.; Redina, A.A.; Chebotarev, D.A.; Nikolenko, A.M.; Dultsev, V.F.; Moroz, T.N.; et al. Petrography, mineralogy and SIMS U-Pb geochronology of 1.9–1.8 Ga carbonatites and associated alkaline rocks of the Central-Aldan magnesiocarbonatite province (South Yakutia, Russia). Mineral. Petrol. 2019, 113, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolenko, A.M.; Redina, A.A.; Doroshkevich, A.G.; Prokopyev, I.R.; Ragozin, A.L.; Vladykin, N.V. The origin of magnetite-apatite rocks of Mushgai-Khudag Complex, South Mongolia: Mineral chemistry and studies of melt and fluid inclusions. Lithos 2018, 320–321, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlov, D.E.; Förster, H.J.; Nijland, T.G. Fluid induced nucleation of REE-phosphate minerals in apatite: Nature and experiment. Part I. Chlorapatite. Am. Mineral. 2002, 87, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlov, D.E.; Förster, H.-J. Fluid-induced nucleation of (Y+REE)-phosphate minerals within apatite: Nature and experiment. Part II. Fluorapatite. Am. Mineral. 2003, 88, 1209–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlov, D.E.; Wirth, R.; Förster, H.J. An experimental study of dissolution–reprecipitation in fluorapatite: Fluid infiltration and the formation of monazite. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2005, 150, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Jones, A.E.; Migdisov, A.A.; Samson, I.M. Hydrothermal mobilization of the rare earth elements-a tale of “Ceria” and “Yttria”. Elements 2012, 8, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropper, P.; Manning, C.E.; Harlov, D.E. Solubility of CePO4 monazite and YPO4 xenotime in H2O and H2O–NaCl at 800 °C and 1 GPa: Implications for REE and Y transport during high-grade metamorphism. Chem. Geol. 2011, 282, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropper, P.; Manning, C.E.; Harlov, D.E. Experimental determination of CePO4 and YPO4 solubilities in H2O–NaF at 800 °C and 1 GPa: Implications for rare earth element transport in high-grade metamorphic fluids. Geofluids 2013, 13, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom-Fendley, S.; Styles, M.T.; Appleton, J.D.; Gunn, G.; Wall, F. Evidence for dissolution-reprecipitation of apatite and preferential LREE mobility in carbonatite-derived late-stage hydrothermal processes. Am. Mineral. 2016, 101, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Dolomite | Calcite | Strontianite | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeO | 4.48 | 3.95 | 4.40 | 3.94 | 3.87 | 3.33 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.96 | 1.31 | b.d. | 0.41 | 0.42 | 1.18 | b.d. | b.d. |

| MnO | 0.59 | 0.54 | 1.21 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.35 | b.d. | b.d. | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.71 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| MgO | 19.90 | 16.80 | 15.99 | 16.99 | 19.25 | 19.85 | 1.34 | 0.56 | 1.08 | 1.46 | 2.97 | 5.07 | b.d. | b.d. | 0.58 | 2.24 | b.d. | b.d. |

| CaO | 30.03 | 28.93 | 31.34 | 29.04 | 29.45 | 29.87 | 50.12 | 50.44 | 50.06 | 49.21 | 46.10 | 45.01 | 9.67 | 3.39 | 23.28 | 16.17 | 3.43 | 2.06 |

| SrO | b.d. | 1.12 | 1.13 | 1.22 | b.d. | 0.58 | 1.38 | 1.14 | 0.93 | 2.21 | 2.02 | 1.90 | 54.31 | 61.11 | 35.99 | 41.21 | 62.36 | 64.51 |

| Na2O | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| BaO | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | 0.51 | b.d. | 0.67 | 1.21 | 0.47 | 1.47 | 5.28 | 3.41 | 4.91 | 2.77 | 0.9 |

| La2O3 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Ce2O3 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Pr2O3 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Nd2O3 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Total | 55.00 | 51.35 | 54.07 | 51.91 | 53.33 | 54.10 | 53.64 | 53.18 | 53.00 | 54.70 | 53.73 | 54.48 | 65.45 | 70.18 | 63.68 | 65.72 | 68.56 | 67.47 |

| Fe apfu | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | b.d. | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | b.d. | b.d. |

| Mn | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | b.d. | b.d. | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Mg | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.13 | b.d. | b.d. | 0.02 | 0.07 | b.d. | b.d. |

| Ca | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| Sr | b.d. | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | b.d. | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.43 | 0.5 | 0.88 | 0.93 |

| Na | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Ba | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | 0.01 | 0.01 | b.d. | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| La | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Ce | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Pr | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Nd | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Component | Norsethite | Barytocalcite | Benstonite | |||||||||||||||

| FeO | 1.08 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 0.99 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | 0.77 | 0.69 | 1.21 | 1.38 | 0.8 | b.d. |

| MnO | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| MgO | 16.55 | 13.71 | 13.96 | 14.01 | 12.55 | 15.19 | 2.92 | 2.16 | b.d. | b.d. | 0.8 | 2.52 | 10.51 | 12.39 | 9.57 | 13.35 | 2.67 | 1.74 |

| CaO | 1.4 | 1.64 | 4.04 | 1.9 | 2.74 | 6.63 | 20.75 | 19.6 | 24.68 | 16.83 | 20.95 | 21.27 | 12.98 | 8.27 | 18.79 | 9.4 | 19.48 | 23.52 |

| SrO | b.d. | b.d. | 0.91 | 0.6 | 0.66 | 0.88 | 1.54 | 2.81 | 0.78 | 6.75 | 2.24 | 4.06 | 0.93 | b.d. | 2.05 | 1.29 | 6.49 | 2.07 |

| Na2O | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| BaO | 52.15 | 51.14 | 49.12 | 50.9 | 49.72 | 49.22 | 43.7 | 43.22 | 44.65 | 48.7 | 45.76 | 39.48 | 41.96 | 46.02 | 34.53 | 45.49 | 37.59 | 39.98 |

| La2O3 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Ce2O3 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Pr2O3 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Nd2O3 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Total | 71.18 | 67 | 68.61 | 68.67 | 66.76 | 72.9 | 68.91 | 67.79 | 70.11 | 72.29 | 70.09 | 67.33 | 67.16 | 67.37 | 66.15 | 70.91 | 67.03 | 67.54 |

| Fe apfu | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | 0.01 | b.d. | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.19 | b.d. |

| Mn | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Mg | 1.04 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.15 | b.d. | b.d. | 0.06 | 0.17 | 4.45 | 5.28 | 4.0 | 5.36 | 1.16 | 0.75 |

| Ca | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.19 | 0.88 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 3.95 | 2.53 | 5.65 | 2.71 | 6.07 | 7.26 |

| Sr | 0 | b.d. | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.15 | b.d. | 0.33 | 0.20 | 1.09 | 0.35 |

| Na | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Ba | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.9 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.7 | 4.67 | 5.16 | 3.80 | 4.80 | 4.29 | 4.51 |

| La | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Ce | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Pr | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Nd | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Component | Calcioburbankite | |||||||||||||||||

| FeO | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | ||||||||||||

| MnO | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | ||||||||||||

| MgO | b.d. | 1.21 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | ||||||||||||

| CaO | 16.45 | 16.51 | 15.63 | 8.1 | 9.21 | 15.08 | ||||||||||||

| SrO | 8.55 | 9.82 | 9.98 | 18.45 | 19.11 | 19.48 | ||||||||||||

| Na2O | 3.33 | 3.95 | 5.00 | 10.18 | 9.44 | 3.09 | ||||||||||||

| BaO | 4.61 | 8.09 | 5.66 | 8.47 | 8.11 | 3.79 | ||||||||||||

| La2O3 | 11.54 | 10.11 | 10.6 | 6.52 | 5.44 | 6.19 | ||||||||||||

| Ce2O3 | 15.47 | 14.22 | 13.74 | 9.65 | 9.42 | 12.1 | ||||||||||||

| Pr2O3 | b.d. | 1.56 | 1.23 | b.d. | 1.57 | 1.06 | ||||||||||||

| Nd2O3 | 2.58 | 3.38 | 2.95 | 2.29 | 3.09 | 3.64 | ||||||||||||

| Total | 62.54 | 68.85 | 64.79 | 63.66 | 65.38 | 64.43 | ||||||||||||

| Fe apfu | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | ||||||||||||

| Mn | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | ||||||||||||

| Mg | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | ||||||||||||

| Ca | 2.09 | 1.91 | 1.92 | 1.03 | 1.13 | 1.87 | ||||||||||||

| Sr | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 1.26 | 1.27 | 1.31 | ||||||||||||

| Na | 0.76 | 0.83 | 1.11 | 2.33 | 2.10 | 0.69 | ||||||||||||

| Ba | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.17 | ||||||||||||

| La | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.26 | ||||||||||||

| Ce | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.51 | ||||||||||||

| Pr | b.d. | 0.06 | 0.05 | b.d. | 0.07 | 0.04 | ||||||||||||

| Nd | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.15 | ||||||||||||

| Component | 3SE/5-3 | SE6A/9 | 6SE-1/2 | SE6A/4 | 6SE-1/16 | 3SE/7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | 1.56 | b.d. | b.d. | 3.13 | 4.24 | 1.25 |

| BaO | 62.00 | 62.44 | 65.06 | 58.80 | 56.41 | 64.83 |

| SrO | 3.00 | 2.20 | 1.20 | 4.42 | 5.12 | 0.67 |

| SO3 | 33.45 | 35.34 | 33.95 | 34.24 | 34.81 | 33.35 |

| Total | 100.01 | 99.98 | 100.21 | 100.59 | 100.58 | 100.10 |

| Component | Fluorapatite | Monazite-(Ce) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 0.035 | 0.127 | 0.016 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.024 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| FeO | 0.127 | 0.278 | 0.147 | 0.233 | 0.009 | 0.027 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| MnO | 0.078 | 0.038 | 0.053 | 0.067 | 0.029 | 0.056 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| CaO | 53.658 | 53.502 | 53.969 | 53.770 | 53.730 | 53.495 | 1.900 | 2.070 | 0.700 | 1.410 | 0.280 | 0.580 |

| Na2O | 0.254 | 0.280 | 0.243 | 0.192 | 0.217 | 0.224 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| SrO | 1.533 | 1.442 | 1.372 | 1.481 | 1.595 | 1.424 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| MgO | 0.061 | 0.016 | 0.056 | 0.065 | 0.011 | 0.016 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| P2O5 | 40.843 | 40.663 | 40.793 | 40.643 | 40.684 | 40.356 | 29.390 | 30.860 | 30.240 | 30.290 | 29.310 | 30.600 |

| La2O3 | 0.203 | 0.247 | 0.204 | 0.187 | 0.242 | 0.220 | 19.470 | 19.490 | 20.830 | 23.560 | 23.160 | 21.770 |

| Ce2O3 | 0.466 | 0.559 | 0.417 | 0.405 | 0.466 | 0.463 | 35.950 | 35.650 | 35.380 | 35.090 | 36.550 | 34.670 |

| Pr2O3 | 0.004 | 0.048 | 0.083 | 0.056 | 0.046 | 0.050 | 1.760 | 3.350 | 2.150 | 1.950 | 2.320 | 2.430 |

| Nd2O3 | 0.133 | 0.389 | 0.221 | 0.150 | 0.229 | 0.302 | 11.550 | 8.890 | 10.650 | 7.420 | 8.500 | 10.120 |

| UO2 | 0.045 | b.d. | 0.014 | b.d. | b.d. | 0.027 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| ThO2 | 0.019 | 0.001 | b.d. | 0.011 | 0.037 | 0.030 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| SO3 | 0.018 | 0.014 | b.d. | 0.003 | b.d. | 0.036 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Cl | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.002 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| F | 2.307 | 2.377 | 2.314 | 2.377 | 2.704 | 2.347 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d | b.d. | b.d. |

| Total | 99.794 | 99.985 | 99.917 | 99.656 | 100.011 | 99.099 | 100.020 | 100.310 | 99.950 | 99.720 | 100.120 | 100.170 |

| F2 = −O | 0.971 | 1.000 | 0.974 | 1.000 | 1.138 | 0.988 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Si apfu | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.001 | b.d. | 0.001 | 0.001 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Fe | 0.008 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.002 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Mn | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.004 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Ca | 4.315 | 4.307 | 4.338 | 4.337 | 4.335 | 4.341 | 0.080 | 0.080 | 0.030 | 0.060 | 0.010 | 0.020 |

| Na | 0.037 | 0.041 | 0.036 | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.033 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Sr | 0.067 | 0.063 | 0.060 | 0.065 | 0.070 | 0.063 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Mg | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.002 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| P | 2.614 | 2.606 | 2.610 | 2.609 | 2.613 | 2.607 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 1.000 |

| La | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.280 | 0.280 | 0.300 | 0.340 | 0.340 | 0.310 |

| Ce | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.520 | 0.500 | 0.510 | 0.500 | 0.530 | 0.490 |

| Pr | b.d. | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.050 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.030 |

| Nd | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.160 | 0.120 | 0.150 | 0.100 | 0.120 | 0.140 |

| U | 0.001 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | 0.001 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Th | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | 0.001 | 0.001 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| S | 0.001 | 0.001 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | 0.002 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Cl | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| F | 0.525 | 0.541 | 0.526 | 0.542 | 0.612 | 0.539 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Component | SE6A/1 | SE6A/1-7 | SE6A/3-2 | SE6A/2-2 | SE6A/3-8 | 6SE/13-7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 56.01 | 57.19 | 56.69 | 57.16 | 56.74 | 57.51 |

| Al2O3 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 1.13 | 1.23 |

| FeO | 5.8 | 4.85 | 4.84 | 4.98 | 5.38 | 3.99 |

| MnO | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.36 |

| MgO | 23.46 | 23.05 | 23.23 | 22.97 | 22.27 | 23.48 |

| CaO | 6.18 | 6.35 | 6.67 | 6.63 | 6.76 | 9.02 |

| Na2O | 5.88 | 5.73 | 5.65 | 5.16 | 5.14 | 3.64 |

| K2O | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.94 | 0.43 |

| F | 2.93 | 1.98 | 1.59 | 1.73 | 1.64 | 1.04 |

| Total | 101.76 | 101.15 | 100.81 | 100.50 | 100.5 | 100.7 |

| F2 = −O | 1.23 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.44 |

| Si apfu | 7.75 | 7.81 | 7.75 | 7.82 | 7.78 | 7.77 |

| Al | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.151 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| Fe3+ | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.25 |

| Al | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mn | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Fe2+ | 0.67 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.21 |

| Mg | 4.84 | 4.69 | 4.73 | 4.68 | 4.56 | 4.73 |

| Ca | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 1.31 |

| Na | 1.58 | 1.52 | 1.50 | 1.37 | 1.37 | 0.95 |

| K | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.07 |

| OH | 0.72 | 1.15 | 1.31 | 1.25 | 1.29 | 1.56 |

| F | 1.28 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.44 |

| Component | SE6A/1-1 | SE6A/1-4 | 6SE/1-3 | 6SE/4 | 6SE/7 | 6SE/1-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 42.72 | 43.26 | 42.27 | 39.39 | 40.47 | 40.78 |

| Al2O3 | 11.47 | 11.26 | 10.56 | 11.02 | 10.47 | 11.47 |

| FeO | 5.71 | 6.36 | 6.09 | 7.32 | 5.33 | 5.63 |

| MgO | 27.73 | 27.63 | 27.30 | 22.98 | 25.47 | 25.39 |

| Na2O | 0.40 | b.d. | 0.77 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| K2O | 9.46 | 10.37 | 9.75 | 8.93 | 9.32 | 9.37 |

| BaO | 1.40 | b.d. | 0.69 | 4.33 | 3.16 | 3.42 |

| F | b.d. | 2.31 | 2.09 | b.d. | 1.97 | 2.05 |

| Total | 98.89 | 101.19 | 99.52 | 93.97 | 96.19 | 98.11 |

| F2 = −O | b.d. | 0.97 | 0.88 | b.d. | 0.83 | 0.86 |

| Si apfu | 2.96 | 2.98 | 2.93 | 2.97 | 2.99 | 2.96 |

| Al | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.93 |

| Fe | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| Mg | 2.86 | 2.84 | 2.82 | 2.58 | 2.80 | 2.74 |

| Na | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.10 | b.d. | 0.00 | b.d. |

| K | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| Ba | 0.04 | b.d. | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| F | b.d. | 0.50 | 0.47 | b.d. | 0.46 | 0.47 |

| Component | 6SE/12-1 | 6SE/12-2 | 6SE/12-3 | SE6A/3-2 | SE6A/5-1 | SE6A/7-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nb2O5 | 37.68 | 38.62 | 38.55 | 42.99 | 43.02 | 44.22 |

| Ta2O5 | 4.66 | 3.54 | 2.71 | 5.14 | 6.13 | 6.84 |

| SiO2 | 3.04 | 1.45 | 2.31 | b.d. | 1.18 | b.d. |

| TiO2 | 4.47 | 4.52 | 6.54 | 5.00 | 4.19 | 5.77 |

| UO2 | 17.53 | 16.64 | 18.21 | 19.66 | 18.99 | 18.16 |

| Al2O3 | 0.59 | 0.45 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| FeO | 2.62 | 4.08 | 3.04 | 2.48 | 2.73 | 4.66 |

| Ce2O3 | 1.32 | 1.63 | 3.63 | b.d. | 2.01 | 1.91 |

| CaO | 2.04 | 5.58 | 6.74 | 6.49 | 6.28 | 6.34 |

| BaO | 11.53 | 9.09 | b.d. | 8.20 | 5.66 | 7.37 |

| SrO | 1.94 | 3.94 | 2.74 | 2.77 | 2.59 | 4.13 |

| PbO | b.d. | b.d. | 2.38 | 1.82 | 2.48 | 2.08 |

| Na2O | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | 1.62 | 0.75 | b.d. |

| Total | 87.43 | 89.55 | 86.86 | 96.17 | 96.01 | 101.47 |

| Ca apfu | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.44 |

| Ba | 0.32 | 0.25 | b.d. | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| Sr | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.15 |

| Na | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.10 | b.d. |

| Ce | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.09 | b.d. | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| U + Pb | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.30 |

| Total A | 0.85 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 1.44 | 1.24 | 1.12 |

| Nb | 1.2 | 1.24 | 1.2 | 1.41 | 1.36 | 1.28 |

| Ta | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Ti | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.35 |

| Al | 0.05 | 0.04 | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. | b.d. |

| Fe | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.25 |

| Si | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.16 | b.d. | 0.08 | b.d. |

| Total B | 2.00 | 1.99 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rampilova, M.; Doroshkevich, A.; Viladkar, S.; Zubakova, E. Mineralogy of Dolomite Carbonatites of Sevathur Complex, Tamil Nadu, India. Minerals 2021, 11, 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11040355

Rampilova M, Doroshkevich A, Viladkar S, Zubakova E. Mineralogy of Dolomite Carbonatites of Sevathur Complex, Tamil Nadu, India. Minerals. 2021; 11(4):355. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11040355

Chicago/Turabian StyleRampilova, Maria, Anna Doroshkevich, Shrinivas Viladkar, and Elizaveta Zubakova. 2021. "Mineralogy of Dolomite Carbonatites of Sevathur Complex, Tamil Nadu, India" Minerals 11, no. 4: 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11040355

APA StyleRampilova, M., Doroshkevich, A., Viladkar, S., & Zubakova, E. (2021). Mineralogy of Dolomite Carbonatites of Sevathur Complex, Tamil Nadu, India. Minerals, 11(4), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11040355