Abstract

In this paper, we introduce formulae for the determinants of matrices with certain symmetry. As applications, we will study the Alexander polynomial and the determinant of a periodic link which is presented as the closure of an oriented 4-tangle.

Keywords:

determinant of a matrix; Seifert matrix of a link; periodic links; Alexander polynomial of a link MSC:

15A15; 57M25

1. Introduction

A block matrix is a matrix which is partitioned into submatrices, called blocks, such that the subscripts of the blocks are defined in the same fashion as those for the elements of a matrix [1].

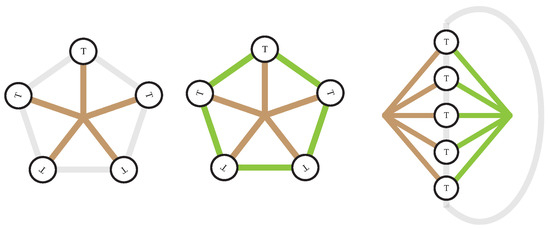

Let us consider periodic subject that consists of finite number of units with the same properties, see Figure 1. There are 5 subjects with the same properties which are arranged periodically. The brown color is used to depict their periodical placement, while the green color in the second and third figure presents an extra relationship which is acting between neighbouring two subjects.

Figure 1.

Type of periodic subject.

The matrix encoding the properties of the whole subject can be presented by block matrices. In the first picture in Figure 1, there are a finite number of units which are placed periodically but there are no interaction between units as seen. The matrix for the periodic subject will be of the form

Indeed, the determinant of the matrix is .

In the second picture in Figure 1, there are a finite number of units which are placed periodically and each unit is affected by neighbouring units as seen. The matrix for such a periodic subject is of the form

In [2], the authors showed that the determinant of such a matrix is given by , where D is an matrix.

On the other hand, in the last picture in Figure 1, there are a finite number of units which are placed periodically and each unit is affected by the periodic structure itself (rather than neighbouring units). The matrix for such a periodic object can be presented by a matrix of the form

or a matrix of the form

The applications in the last section will be helpful to understand the difference between (3) and (4).

In this paper, we will show that the determinant of the matrix (3) is

while the determinant of the matrix (4) is

As an application, we will find the Alexander polynomial and the determinant of a periodic link (Theorems 4–7). Notice that, if a matrix M is singular, then we define .

2. Determinants

Theorem 1.

Let and D be matrices of size and , respectively and O the zero-matrix. Then

where the number of A’s in the diagonal is n and the number of ’s in the diagonal is .

Proof.

The identity can be obtained by elementary determinant calculation. We put the detailed proof at Appendix A for the convenience of readers. ☐

Theorem 2.

Let and E be matrices of size and , respectively and O the zero-matrix. Then

where the number of A’s in the diagonal is n and the number of ’s in the diagonal is .

Proof.

The identity can be obtained by elementary determinant calculation. The identity comes by adding the kth column to the first column and then, adding the (the first row) to the kth row for any , while the identity can be found in Appendix A. ☐

Remark 1.

If A is invertible, then Theorems 1 and 2 can be proved by using the Schur complement. We put those proofs at Appendix B. The Authors appreciate such valuable comments given by our reviewer.

3. Application: Alexander Polynomials and the Determinants of Periodic Links

We start this section by reviewing results of knot theory which are related with the calculation of the Alexander polynomial and the determinant of a link, see [2,3,4] in detail.

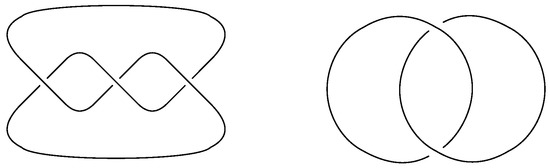

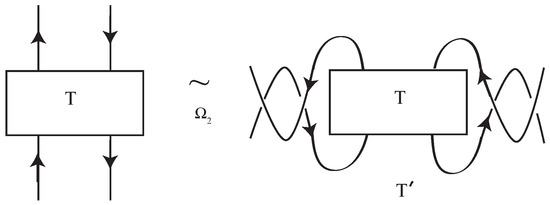

A knot K is an embedding of into the 3-space . A link is a finite disjoint union of knots: . Each knot is called a component of the link L. Two links L and are equivalent (or ambient isotopic) if one can be transformed into the other via a deformation of upon itself. A diagram of a link L is a regular projection image from the link L into such that the over-path and the under-path at each double points of are distinguished. There are examples of a knot and a link in Figure 2. Two link diagrams are equivalent if one can be transformed into another by a finite sequence of Reidemeister moves in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

A trefoil knot diagram and a Hopf link diagram.

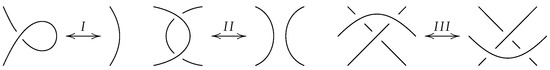

Figure 3.

Reidemeister moves.

A Seifert surface for an oriented link L in is a connected compact oriented surface contained in which has L as its boundary. The following Seifert algorithm is one way to get a Seifert surface from a diagram D of L.

Let D be a diagram of an oriented link L. In a small neighborhood of each crossing, make the following local change to the diagram;

- Delete the crossing and reconnect the loose ends in the only way compatible with the orientation.

When this has been done at every crossing, the diagram becomes a set of disjoint simple loops in the plane. It is a diagram with no crossings. These loops are called Seifert circles. By attaching a disc to each Seifert circle and by connecting a half-twisted band at the place of each crossing of D according to the crossing sign, we get a Seifert surface F for L.

The Seifert graph of F is constructed as follows;

- Associate a vertex with each Seifert circle and connect two vertices with an edge if their Seifert circles are connected by a twisted band.

Note that the Seifert graph is planar, and that if D is connected, so does . Since is a deformation retract of a Seifert surface F, their homology groups are isomorphic: . Let T be a spanning tree for . For each edge , contains the unique simple closed circuit which represents an 1-cycle in . The set of these 1-cycles is a homology basis for F. For such a circuit , let denote the circuit in obtained by lifting slightly along the positive normal direction of F. For , the linking number between and is defined by

A Seifert matrix of L associated to F is the matrix defined by

where . A Seifert matrix of L depends on the Seifert surface F and the choice of generators of .

Let M be any Seifert matrix for an oriented link L. The Alexander polynomial and determinant of L are defined by

For details, see [4,5].

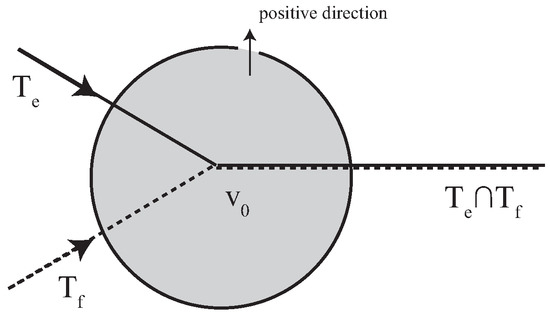

For , is either an empty set, one vertex or a simple path in the spanning tree T. If is a simple path, and are two ends of , we may assume that the neighborhood of looks like Figure 4. In other words, the cyclic order of edges incident to is given by with respect to the positive normal direction of the Seifert surface. Also we may assume that the directions of and are given so that is the starting point of . For, if the direction is reversed, one can change the direction to adapt to our setting so that the resulting linking number changes its sign.

Figure 4.

.

In [6], the authors showed the following proposition which is the key tool to calculate the linking numbers for Seifert matrix of a link.

The Alexander polynomial of a knot or a link is the first polynomial of the knot theory [7]. The polynomial was reformulate and derived in several different ways over the next 50 years. Perhaps the most satisfying of these is from the homology of the branched cyclic covering space of the knot complement. This reveals the underlying geometry and generalizes to higher dimensions and to a multi-variable version for links. See [4]. Many researchers reformulate the Alexander polynomial as a state sum, Kauffman [8] and Conway [9], etc. Recently, many authors interested in the twisted Alexander polynomial and Knot Floer homology, it provides geometric information of a knot or a link, see [10,11,12,13]. The Alexander polynomial is categorified by Knot Floer homology, see [14,15]. Furthermore, since Alexander polynomial is a topological content of quantum invariants, Alexander polynomial is one of the most important invarinat of knot theory, see [16].

Proposition 1

([6]). For , let p and q denote the numbers of edges in corresponding to positive crossings and negative crossings, respectively. Suppose that the local shape of in F looks like Figure 4. Then,

A link L in the 3-sphere is called a periodic link of order n if there is an orientation preserving auto-homeomorphism of which satisfies the following conditions; , , the fixed-point set of , is a 1-sphere disjoint from L and is of period n. The link is called the factor link of the periodic link L. We denote by . One of an important concern of knot theory is to find the relationship between periodic links and their factor links, see [17,18]. In 2011, the authors expressed the Seifert matrix of a periodic link which is presented as the closure of a 4-tangle with some extra restrictions, in terms of the Seifert matrix of quotient link in [2].

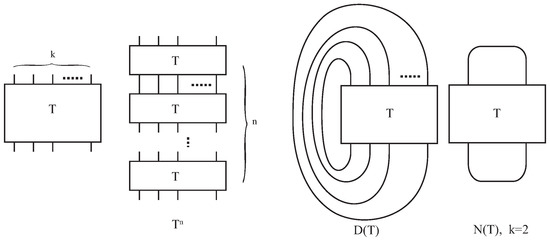

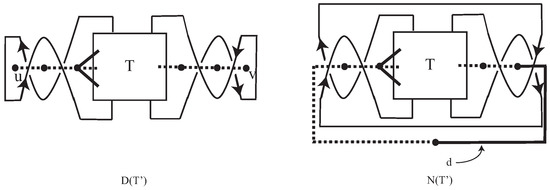

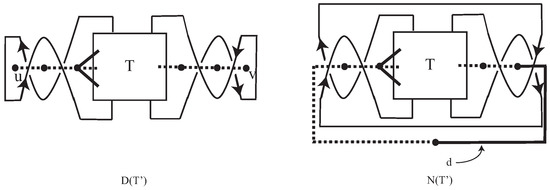

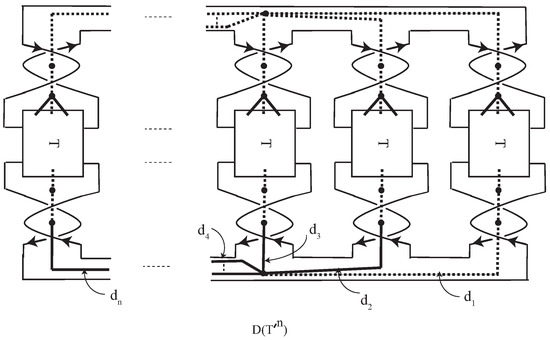

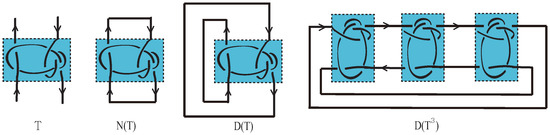

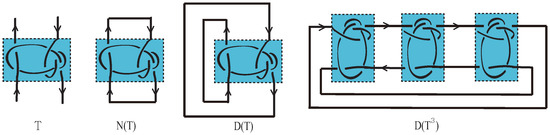

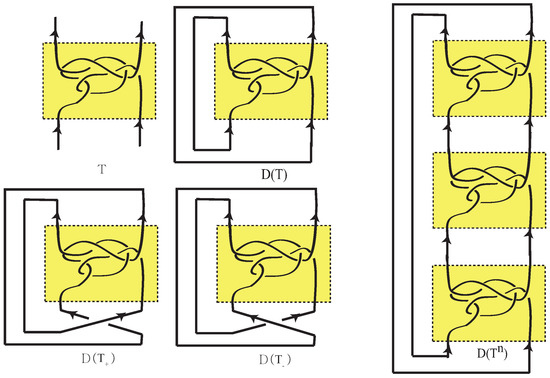

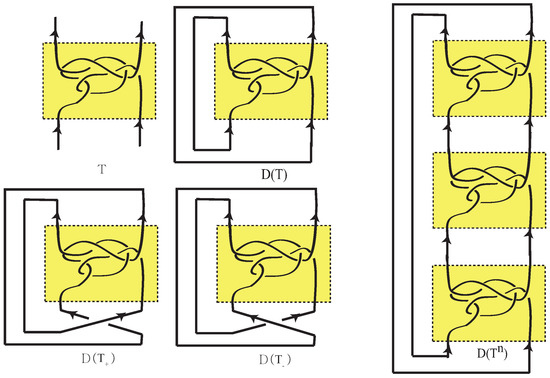

Let I be a closed interval and k a positive integer. Fix k points in the upper plane of the cube and the corresponding k points in the lower plane . A -tangle is obtained by embedding oriented curves and some oriented circles in so that the end points of the curves are the fixed -points. By a -tangle, we mean a -tangle. Let T be a -tangle. For an integer , let denote the -tangle obtained by stacking Tn-times. The denominator of T is defined by connecting the top ends of T to the bottom ends by parallel lines, see Figure 5. In particular, if T is a 4-tangle, then the numerator of T is defined as the last picture in Figure 5. Clearly, is a periodic link of order n whose factor link is . If an orientation is given on , then it induces an orientation of . Notice that every (oriented) periodic link can be constructed in this way.

Figure 5.

-tangle, denominator and numerator.

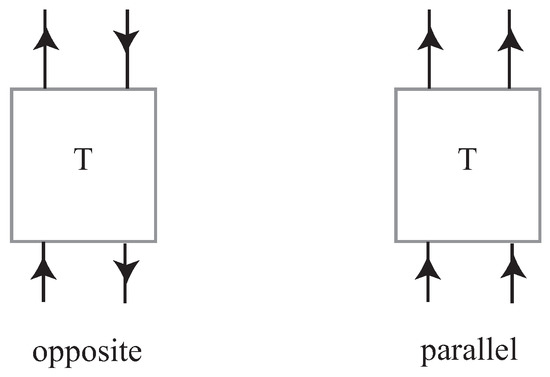

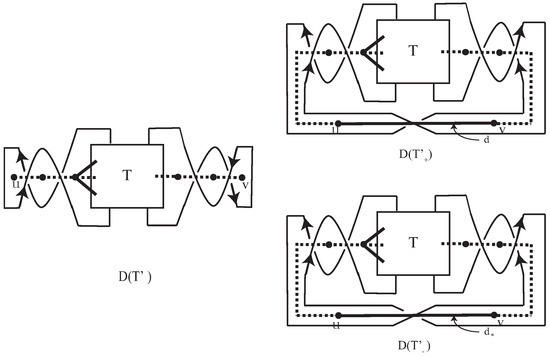

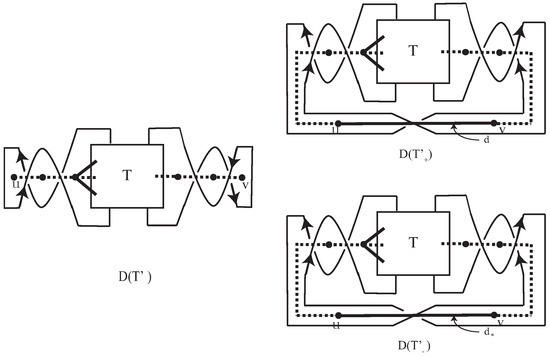

Let T be a 4-tangle and let denote the denominator of T which is obtained by connecting the top ends and the bottom ends of T by parallel curves and . Suppose that is oriented. Note that the induced orientation at and are either opposite or parallel, see Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Orientation of a tangle.

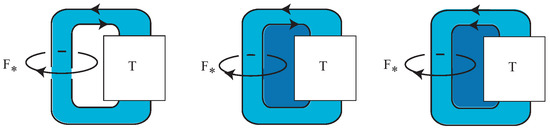

If the induced orientation at and are parallel, then and are contained in different Seifert circles of . Hence we have the following three cases.

- Case I:

- The orientations at the end points of the curves in T are opposite and the two outer arcs and of are contained in the same Seifert circle, see the first picture in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Three types of denominator .

Figure 7. Three types of denominator . - Case II:

- The orientations at the end points of the curves in T are opposite and the two outer arcs of are contained in different Seifert circles, see the second picture in Figure 7.

- Case III:

- The orientations at the end points of the curves in T are parallel, see the last picture in Figure 7.

3.1. Periodic Links with Periodicity in Case I

In Case I and Case II, the numerator of T is well-defined as an oriented link. In particular, in Case I, the linking number between any Seifert circle of and the periodic axis is always 0, which is equivalent to that for any Seifert circle C of . For Case I, the authors gave the following criteria for Alexander polynomial of the periodic link by using those of the denominator and the numerator of a 4-tangle T.

Proposition 2

([2]). Let L be a periodic link of order n with the factor link . Suppose that and for a 4-tangle T. If for any Seifert circle C of , then the Alexander polynomials of L, and are related as follows;

Indeed, to get the result, the authors showed the following proposition and then applied the determinant formula for the matrix (1).

Proposition 3.

If T is a 4-tangle in Case I, then there exist Seifert matrices and of and , respectively, such that

where B is a column vector, C is a row vector, O is the zero-matrix and the number of block is n.

3.2. Periodic Links with Periodicity in Case II

In Case II, there is a Seifert circle C of such that . In fact where and denote Seifert circles in containing and , respectively.

Lemma 1.

If T is a 4-tangle in Case II, then there exist Seifert matrices and of and , respectively, such that

where B is a row vector, C is a column vector, O is the zero-matrix, the number of block is n, and the number of block is .

Proof.

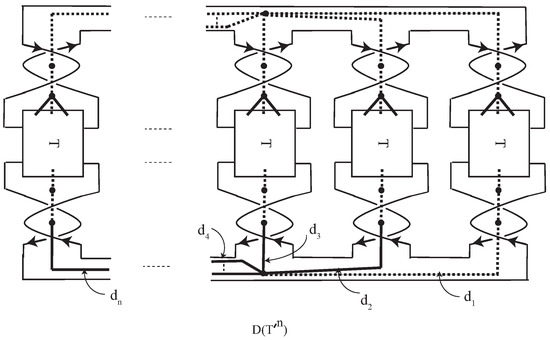

Suppose that the orientations at the end points of the curves in T are opposite and the two outer arcs of are contained in different Seifert circles. Without loss of generality, we may assume that T looks like as seen in Figure 8 that obtained from T by applying the Reidemeister move II between the left two outer curves and the right two outer curves of T, respectively. Note that , and are ambient isotopic to , and , respectively.

Figure 8.

Applying Reidemeister Move II.

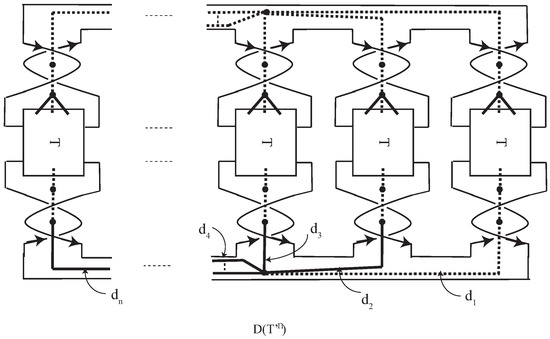

The Seifert graphs and of and are of the form in Figure 9, in which spanning trees and of and are given by dotted edges in Figure 9. Notice that is obtained from by identifying the left vertex u to the right vertex v in as shown in the right picture in Figure 9. If , then where d is the new edge of as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Seifert graphs for and .

The corresponding Seifert matrix of is a matrix, while the Seifert matrix of is a matrix. Furthermore, the linking number between and in is equal to the linking number between and in for all , by Proposition 1. Indeed, for all . Hence the Seifert matrix of is given by

where and

From now on, we will try to find a Seifert matrix of . The Seifert graph of consists of n copies of whose final vertices u and v are used to connect the copies of as shown in Figure 10. Let be the corresponding pth copy of d for all in . By removing -copies of the edge d, e.g., in Figure 10, we get a spanning tree of . Indeed,

where is the corresponding pth copy of .

Figure 10.

Seifert graph for .

Since the linking number between and in is equal to the linking number between and in for all and we have where . If , since and do not intersect, for all by Proposition 1. Hence,

On the other hand, since lies in the 1st copy and pth copy of , we have , , and for all . For and , and since and do not intersect in .

Since T is connected, the generator runs through 2 copies, in each of which the self linking number of is equal to D for all . Furthermore, since the orientations at the end points of the curves in T are opposite, D is even. Hence, for all , by Proposition 1. For all and , Because generators and meet in the just 1st copy. ☐

Hence by using Theorem 1, we get the following result.

Theorem 3.

Let L be a periodic link of order n with the factor link . Suppose that and for a 4-tangle T in Case II. Then the Alexander polynomials of , and are related as follows;

Proof.

By the definition of the Alexander polynomial of a link and by Lemma 1, we have

☐

Since the result in Theorem 3 (Case II) equals that in Proposition 2 (Case I), we can summarize them as

Theorem 4.

Let L be a periodic link of order n with the factor link . Suppose that and for a 4-tangle T whose numerator is defined. Then the Alexander polynomials of L, and are related as follows;

Theorem 5.

Let L be a periodic link of order n with the factor link . Suppose that and for a 4-tangle T whose numerator is defined. Then the determinants of L, and are related as follows;

Proof.

Note that for any oriented link L. By Theorem 4, we have

☐

Example 1.

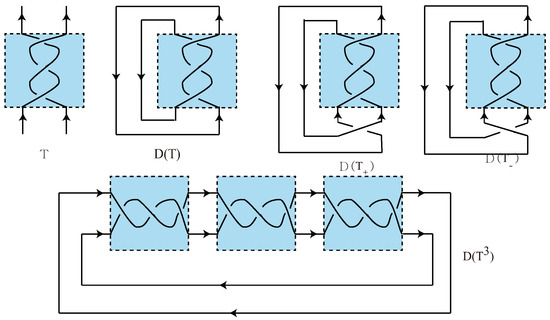

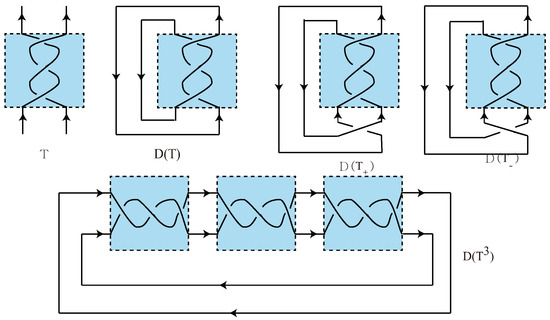

Consider the oriented 4-tangle T in Figure 11, which is a 4-tangle in Case II.

Figure 11.

Example for Case II.

The Seifert matrices of and are given by

while

By the direct calculation, one can see that the Alexander polynomials of and are

By using Theorem 3, we get the Alexander polynomial of ;

Finally, one can get by Theorem 5 because and .

3.3. Periodic Links with Periodicity in Case III

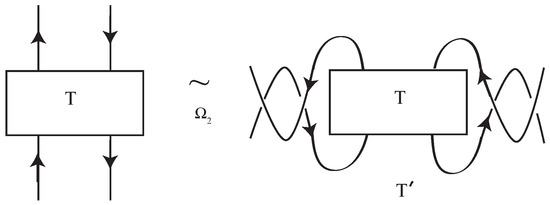

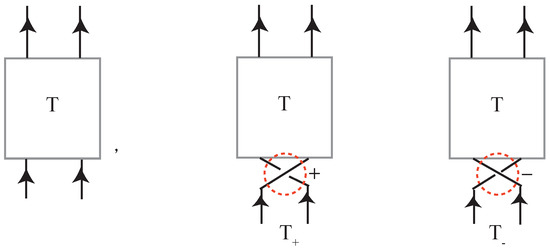

In Case III, recall that the orientation of T is given as the left of Figure 12 so that there exist exactly two Seifert circles and in such that . Note that the orientation of T cannot be extended to an orientation of . Define and by adding a positive crossing and a negative crossing at the bottom of T respectively, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

T+ and T−.

Lemma 2.

If T is a 4-tangle in Case III, then there exist Seifert matrices and of and , respectively, such that

where B is a row vector, C is a column vector, O is the zero-matrix, , the number of block is n and the number of block is .

Proof.

Since the process of the proof is similar to that of Theorem 3, we will give briefly sketch of the proof.

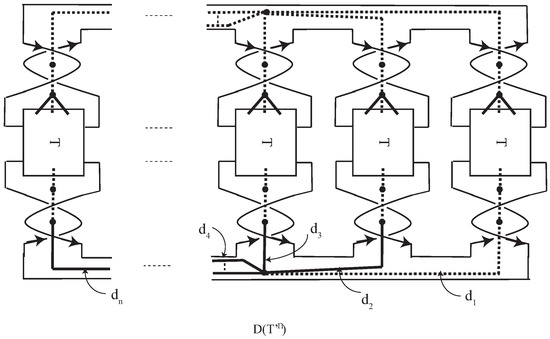

The Seifert graphs , and of , and are of the form in Figure 13, in which spanning trees , and of and are given by dotted edges in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Seifert graphs of , and .

The Seifert graph of consists of n copies of whose the end vertices u and v are used to connect the copies of as shown in Figure 14. Let be the corresponding pth copy of d for all in . Notice that by the construction of , d and correspond to the same edge in , where d and were new edges in Figure 13. By removing -copies of the edge d (or ) in , e.g., in Figure 14, we get a spanning tree of . ☐

Figure 14.

Seifert graph of .

By using the determinant formula in Theorem 2, we get the following theorem.

Theorem 6.

Let L be a periodic link of order n with the factor link . Suppose that and for a 4-tangle T in Case III. Then the Alexander polynomials of L, , and are related as follows;

Proof.

By the definition of the Alexander polynomial of a link and by Lemma 2, we have

☐

In general, the determinant of cannot be calculated by using Theorem 6 because . But we can calculate the determinant of under certain conditions.

Theorem 7.

Let L be a periodic link of order n with the factor link . Suppose that and for a 4-tangle T in Case III. If , then

where m is the size of a Seifert matrix of .

Proof.

Notice that, for a Seifert matrix of a link L.

From the definition of the determinant of a link, Theorem 2 and Lemma 2, if the Seifert matrix of is an matrix and , then the determinant of is

The identity (1) comes by the condition because

☐

Example 2.

Consider the oriented 4-tangle T in Figure 15, which is a 4-tangle in Case III.

Figure 15.

Example for Case III.

The Seifert matrices of , and are given by

while

By direct calculation, one can see that the Alexander polynomials of , and are

By using Theorem 6, we get the Alexander polynomial of ;

Remark 2.

In Theorem 7, the condition is essential. Consider the oriented 4-tangle T in Figure 15, which is a 4-tangle in Case III. By direct calculation, one can see that the determinant of . The result is the same with in Theorem 7. We can easily check this example satisfies the condition. Consider the oriented 4-tangle T in Figure 16, which is a 4-tangle in Case III.

Figure 16.

.

The Seifert matrices of , and are given by

while

By direct calculation, one can see that the Alexander polynomials of , and are

By using Theorem 6, we get the Alexander polynomial of ;

Finally, one can see that by direct calculation. The result is not equal to since and . We can check that this example doesn’t satisfy the condition since .

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2016R1D1A3B01007669).

Author Contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of Theorem 1.

The reasons for the identities (1)–(5) are the following;

- (1)

- Add the kth column to the first column and then, add (the first row) to the kth row for any .

- (2)

- Add the kth column to the last column for any .

- (3)

- B and D are an and an matrices, respectively.

- (4)

- Add (the last column) to the kth column for any .

- (5)

- Add (the kth column) to the last column for any .

It is the end of the proof of Theorem 1. ☐

Proof of Theorem 2.

To prove

where the number of A’s and the number of ’s in the diagonal are , we proceed by the mathematical induction on n, the number of block A. It is clear that

Assume that the formula is true for . It is well-known that the determinant can be obtained by adding the determinants of the following two matrices.

and

By simple calculation, one can calculate their determinants. Indeed, the determinant of the first matrix (I) is

while the determinant of the second matrix (II) is

The reasons for the identities (1)–(4) are the following;

- (1)

- Add {the th row} to the kth row for any , and then, add {the th row} to the kth row for any .

- (2)

- Add the kth column to the th column for any , and then, add {the th column} to the kth column for any .

- (3)

- Apply the following identity repeatedly.

- (4)

- Add {the th column} to the kth column for any .Therefore the determinant of our matrix is given byBy using this result, we can prove Theorem 2. ☐

Appendix B

The following proofs use more sophisticated matrix theory tools and henceforth are more compact. We assume that A is invertible so that the Schur complement can be defined. However this is only a technical assumption: in fact, looking at the final formula in Theorem 1, this depends with continuity with respect to the entries of A (and in particular with respect to ) and therefore if the statement holds for different from zero, then it must be true also when and the reason is that the set of invertible matrices is dense in the set of all matrices (see [19]).

Two preliminary things are needed. The first is the Schur complement (see [20] and references therein) of a block matrix which corresponds at a single block step of the Gaussian Elimination so that the determinant of X is equal to

The second is the tensor product [19] of square matrices so that

where Y is square of size u and Z is square of size v.

Now we are ready to prove Theorem 1. First we observe that so that by (A2) we have . Second we compute the Schur complement S according to (A1) and we find

with vector of all ones of size . Now is the Schur complement of and hence by the first part of (A1) we have . The matrix has rank 1 and hence it has eigenvalues equal to zero and one coinciding with the trace, that is : hence the matrix has eigenvalue 1 with multiplicity and eigenvalue n with multiplicity 1 so that its determinant is n

so that, by putting together the latter relation and , we obtain

and Theorem 1 is proved.

With the very same tools and by following the same steps, Theorem 2 can be proven as well.

References

- Howard, A. Elementary Linear Algebra; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, Y.; Lee, I.S. On Alexander polynomial of periodic links. J. Knot Theory Ramif. 2011, 20, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.E. Homogeneous links, Seifert surfaces, digraphs and the reduced Alexander polynomial. Geom. Dedicata 2013, 166, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, P. Knots and Links; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi, A. A Survey of Knot Theory; Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland; Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, Y.; Lee, I.S. On Seifert matrices of symmetric links. Kyungpook Math. J. 2011, 51, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J. Topological invariants for knots and links. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1928, 30, 275–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, L.H. Formal Knot Theory; Mathematical Notes, 30; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J. An enumeration of knots and links and some of their algebraic properties. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computational Problems in Abstract Algebra, Oxford, UK, 29 August–2 September 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, J.A.; Livingston, C.; Naik, S. Twisted Alexander polynomials of periodic knots. Algebr. Geom. Topol. 2006, 6, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, T. Twisted Alexander polynomials and ideal points giving Seifert surfaces. Acta Math. Vietnam. 2014, 39, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsváth, P.; Szabó, Z. Holomorphic disks and knot invariants. Adv. Math. 2004, 186, 58–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, J.A. Flouer Homology and Knot Complements. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, L.H.; Silvero, M. Alexander-Conway polynomial state model and link homology. J. Knot Theory Ramif. 2015, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsváth, P.; Szabó, Z. An introduction to Heegaard Flouer homology. Available online: http://math.mit.edu/~petero/Introduction.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2017).

- Sartori, A. The Alexander polynomial as quantum invariant of links. Ark. Mat. 2015, 53, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murasugi, K. On periodic knots. Comment. Math. Helv. 1971, 46, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, M.A. On the polynomials of periodic links. Math. Ann. 1981, 257, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R. Matrix Analysis; Springer Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dorostkar, A.; Neytcheva, M.; Serra-Capizzano, S. Spectral analysis of coupled PDEs and of their Schur complements via the notion of Generalized Locally Toeplitz sequences. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2016, 309, 74–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).