Abstract

Cyclooctatetraene (COT), the first 4nπ-electron system to be studied, adopts an inherently nonplanar tub-shaped geometry of D2d symmetry with alternating single and double bonds, and hence behaves as a nonaromatic polyene rather than an antiaromatic compound. Recently, however, considerable 8π-antiaromatic paratropicity has been shown to be generated in planar COT rings even with the bond alternated D4h structure. In this review, we highlight recent theoretical and experimental studies on the antiaromaticity of hypothetical and actual planar COT. In addition, theoretically predicted triplet aromaticity and stacked aromaticity of planar COT are also briefly described.

1. Introduction

Cyclooctatetraene (COT) was first prepared by Willstätter in 1911 [1,2]. At that time, the special stability of benzene was elusive and it was of interest to learn the reactivity of COT as the next higher vinylogue of benzene. However, unlike benzene, COT was found to be highly reactive to electrophiles just like other alkenes. This is because the ground state structure of COT is nonplanar tub-shaped geometry of D2d symmetry with alternating single and double bonds [3,4,5]. The dihedral angle between vicinal double bonds is 56° in the crystal structure [6] so that the π bonds cannot conjugate well with each other due to the absence of proper overlap between the neighboring p orbitals.

After two decades of the historical synthesis of COT, Hückel applied molecular orbital (MO) theory to monocyclic conjugated system using the π-electron approximation, and explained why cyclic delocalization of (4n+2) π-electron systems causes unusual stability [7], which is now recognized as aromaticity. The theory also predicted that the highest occupied MO of cyclic π-conjugated systems with 4nπ-electrons should consist of a pair of half-filled and degenerate nonbonding orbitals. Accordingly, cyclic conjugation of 4nπ-electrons is considered to be energetically unfavorable. In fact, some 4nπ-electron systems such as cyclobutadiene [8,9] and cyclopropenyl anion [10,11] led to strong destabilization of the compound in contrast to the stabilization characteristic of aromatic compounds. Breslow proposed the term of antiaromaticity to describe such systems [12,13].

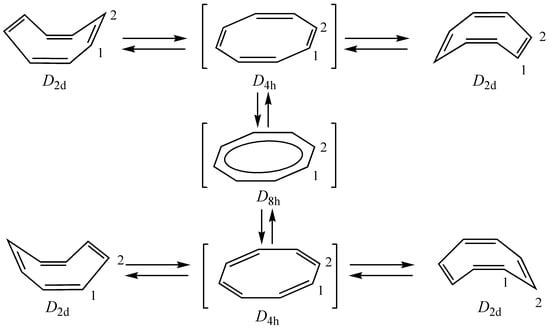

Based on Hückel MO theory, 8π-electron system of COT with a planar and delocalized D8h structure is predicted to have a triplet ground state. However, ab initio complete-active-space self-consistent-field (CASSCF) calculations showed that open-shell singlet state of COT with a D8h structure is more stable than the triplet state [14]. The violation of Hund’s rule was explained by the “disjoint diradicals” [15,16]. On the other hand, a planar and bond alternated D4h structure should have a closed-shell singlet state where the degeneracy of the frontier orbitals for the D8h structure is removed by a Jahn-Teller distortion. These singlet D8h and D4h structures are the presumable transition states of double bond shift and ring inversion of COT (Figure 1), although nonplanar crown- [17] and saddle-like conformations [18,19,20,21] were discussed as alternative transition state for the double bond shift. Accordingly, the barriers for both double bond shift and ring inversion should be related to the energetic aspect of antiaromaticity of COT. The inversion barrier have been measured via various methods and was found to be 10-13 kcal mol-1 [22,23,24,25], while the barrier to bond shift was shown to be 2-4 kcal mol-1 higher than the inversion barrier [22,23,26], even though steric effects in substituted COTs tend to increase the barrier for both bond shift and ring inversion [27,28] and steric effects also reduce the difference between the two barriers in multiply substituted COTs [27]. Since the inner angle of the planar COT (135°) is larger than the ideal bond angle for sp2 hybridized carbon (120°), there are some strains in the planar D8h and D4h transition states, and hence the antiaromatic destabilizations in both D8h and D4h structures are at most several kcal mol-1. In accord with this explanation, the hydrogen transfer energy for the planar D4h COT going to cyclooctatriene was reported to be –8 kcal mol-1 (B3LYP/6-311+G*) and –9 kcal mol-1 (MP2/6-311+G*) [9], whereas isodesmic (27.8 kcal mol-1 MP2/6-31G*//HF/3-21G [29]; 28.4 kcal mol-1 MP4SDTQ/6-31G**//MP2/6-31G**+ZPE(HF/6-31G*) [30]) and homodesmic (–28.4 kcal mol-1 [30]) stabilization energies gave rather different results.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawings of ring inversion and double bond shift of D2d COT via D4h and D8h transition states, respectively.

The other important criteria for the study of aromaticity and antiaromaticity are related to the magnetic properties of compounds. Aromatic compounds sustain diatropic ring currents with bond length equalization, while antiaromatic compounds sustain paratropic ring currents in spite of localized structures [31,32,33,34]. As a result, diatropic ring currents cause exaltations of diamagnetic susceptibility from the sum of that of acyclic reference compounds [35,36]. Also in NMR chemical shifts, shielding and deshielding effects are observed inside and outside aromatic rings, respectively, while antiaromatic paratropicity results in the opposite effects [32,34]. These phenomena can be detected experimentally. However, the comparable quantification may be difficult because the diamagnetic susceptibility exaltations depend on the references selected and because many environmental factors affect NMR chemical shifts. On the other hand, there have been several approaches to estimate the ring current intensities using theoretical calculations. Among them, nucleus independent chemical shift (NICS) developed by Schleyer et al. [37,38] is one of the most used index because of the simplicity and efficiency of the methods. The methods for the visualization of ring currents such as CTOCD-DZ (continuous transformation of origin of current density - diamagnetic zero) [39,40] have also been developed recently. By using these methods, studies on the antiaromatic paratropicity of planar COTs have progressed. In this review, we highlight recent theoretical and experimental studies on the antiaromaticity based on the magnetic properties of hypothetical planar COT and related planarized COT annelated with ring units [41]. In addition, theoretically predicted triplet aromaticity and stacked aromaticity of planar COT are also briefly described.

2. Unsubstituted COT

Since planar conformations of unsubstituted COT are considered to be the transition states of ring inversion and bond shift, it is difficult to experimentally investigate the planar COT [25] and most studies have been performed with quantum chemical calculations. In this section, computational studies of the aromaticity and antiaromaticity of planar COT based on NICS and CTOCD-DZ are summarized.

2.1. Computational Studies Based on NICS

The degrees of aromaticity of tub-shaped D2d (singlet (S0)) and planar D4h (S0) and D8h (open-shell S0 and triplet (T1) states) COT that have been assessed using NICS criteria are summarized in Table 1, together with the bond lengths of each optimized geometries [38,42,43]. The NICS(0) value of tub-shaped D2d COT is +3.0 at the GIAO/HF/6-31+G* level using the B3LYP/6-311+G** optimized geometry [42]. The small value is in line with the expected nonaromatic character due to the bent structure. On the other hand, effect of bending of the C=C–H angle directed toward the double bond in D2d COT was investigated [44]. The bending of the C=C–H angle causes increase of NICS value with increasing planarity of the COT ring and decreasing HOMO–LUMO gap.

Table 1.

C–C Bond lengths and NICS(0) values for the S0 and T1 states of COT.

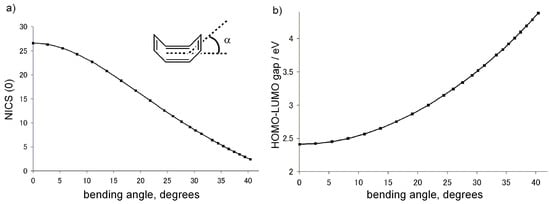

In addition, to investigate the relationships among the strength of paratropicity, the HOMO–LUMO gap, and the bent angle α of the COT ring, the NICS values and the HOMO–LUMO gaps of COT with various bent angles were calculated at the GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G** level [45] and the results are plotted in Figure 2. As the bent angle decreases, the NICS value of the COT ring increases (Figure 2a), with considerable narrowing of the HOMO–LUMO gap (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Correlations between a) NICS(0) (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**) and bent angle α and b) HOMO–LUMO gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) and bent angle α of cyclooctatetraene.

The NICS(0) value of planar COT with bond alternated D4h symmetry was reported in the first paper of NICS [38]. The value is +30.1 at the GIAO/HF/6-31+G* level using the B3LYP/6-31G* optimized geometry, suggesting that the considerable antiaromatic paratropicity is generated in the planar COT ring even with the bond alternated structure. Similar result (+29.3) was obtained for D4h COT at the GIAO/HF/6-311+G*//HF/6-31G** level [43]. However, the NICS(0) value was shown to be considerably reduced when the CASSCF-GIAO method was used. The value (+16.1) of D4h COT at the CASSCF-GIAO level is almost half of that of HF-GIAO method. It is also much smaller than that (+40.7) of D8h COT at open-shell S0 state by factor of 2.3 [43]. For the estimation of NICS value of D8h COT at S0 state, the use of CASSCF-GIAO is essential, and hence such a large discrepancy is only observed in the method. In any case, the NICS-based studies showed that the antiaromatic paratropicity of planar COT is highest for the D8h structure at open-shell S0 state and considerable antiaromaticity is retained for D4h structure despite of the small barriers for ring inversion and bond shift of COT ring.

As concerns the lowest T1 state of D8h COT, not antiaromaticity but rather aromaticity is expected. The idea that triplet 4nπ-electron annulene is regarded as being aromatic was originally suggested in 1972 [46] using its Dewar resonance energy. Other studies supported the aromaticity of 4nπ-electron annulene [47,48]. The NICS calculations also supported the aromaticity of D8h COT at T1 state. The NICS(0) value is –12.4 at the GIAO/HF/6-31+G*//B3LYP/6-311+G** [42], which is, however, more negative than that (–8.9) of CASSCF-GIAO method [43]. Another study based on scanning NICS over a distance and separating them into in-plane and out-of plane contributions also confirmed the aromaticity of D8h COT at T1 state [49]. It is to be noted that the C–C bond lengths of D8h COT at both S0 and T1 states are almost identical irrespective of the antiaromatic and aromatic characters, respectively [43].

2.2. Computational Studies Based on CTOCD-DZ

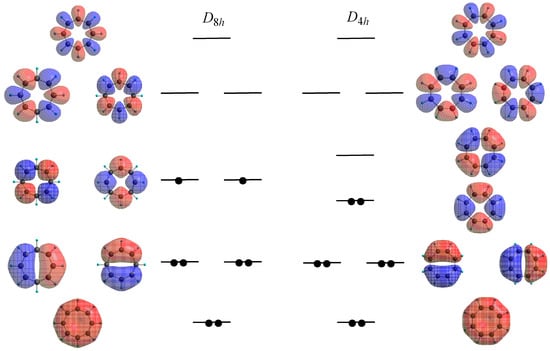

In CTOCD-DZ, a point, at which the induced current density is calculated, is taken as the origin of vector potential and the accumulated vectors yield three-dimensional induced molecular current distributions. In addition, the current maps can be expressed as sums of the possible orbital contributions. By taking advantage of the latter feature, orbital contribution in the paratropic ring current of D4h COT was investigated [50,51]. As mentioned above, D8h COT has a pair of half-filled and degenerate nonbonding orbitals, while the degeneracy is removed by a Jahn-Teller distortion in D4h COT (Figure 3). As a result, the HOMO–LUMO pair split into two non-degenerate components with a narrow HOMO–LUMO gap. This causes a rotational transition with a small energy and thereby produces a strong paramagnetic ring current. CTOCD-DZ clearly demonstrated that the paratropic ring current in D4h COT is dominated by the HOMO–LUMO transition [50,51], meaning the paratropicity corresponds to circulation of only two-electrons in the frontier orbitals.

Figure 3.

π-Molecular orbitals and their orbital energy schemes for D8h and D4h COT.

Furthermore, the paratropic ring currents in tub-shaped D2d COT were also investigated by means of CTOCD-DZ [52]. In the study, d (Å) value is defined as the distance between the planes of the upper and bottom four carbons of tub-shaped COT ring. The paratropic ring current was shown to survive even in a tub-shaped COT ring when d is below 0.62 Å. Since d of the equilibrium structure of tub-shaped COT is 0.76 Å, the paratropic current survive until 80% of the geometric change.

3. COTs Planarized by Annelation

3.1. Attempted syntheses

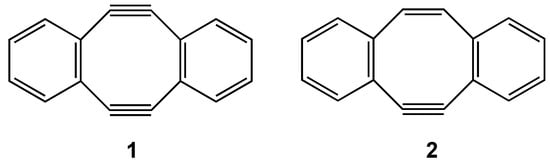

In the initial synthetic study to realize planar [8]annulene, triple bonds were introduced and dibenzocyclooctadiene-3,7-diyne (1) and dibenzocyclooctatriene-7-yne (2) (Figure 4) were prepared [53, 54,55]. X-ray studies of diyne 1 demonstrated that the [8]annulene core has a planar structure [56]. However, the antiaromatic paratropicity of 1 as well as 2 is considerably attenuated judging from the NICS(0) value of 1 (+4.04 at the GIAO/B3LYP/6-31G* level) [57].

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of dibenzocyclooctadiene-3,7-diyne (1) and dibenzocyclooctatriene-7-yne (2).

For the other methods without using triple bond, there are two strategies to constrain the inherently non-planar COT ring to adopt a planarized conformation. They are the annelation of either small membered rings or rigid planar π-systems to the COT skeleton. In the former structural modification, the annelated small ring causes widening of the exocyclic bond angle which corresponds to the inner angle of the COT ring. Since the average inner angle of octagon (135°) is larger than the ideal bond angle for sp2 hybridized carbon (120°), the widening of the inner angle of COT ring brings about some planarization. By the use of this method, COTs 3-5 annelated with one three- or four-membered ring (Figure 5) have been prepared.

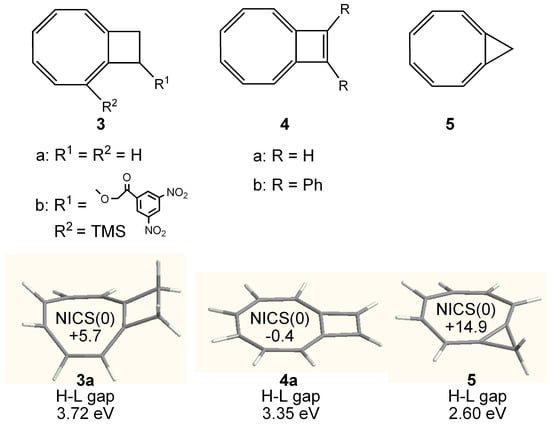

Figure 5.

Chemical structure of cyclobuteno-COT 3, bicyclo[6.2.0]decapentaene 4 and cycloprop[8]annulene 5. Calculated geometry, NICS(0) (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**) and HOMO–LUMO (H-L) gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) of 3a, 4a, and 5 are also shown.

Among them, the parent 3a readily polymerizes when concentrated [58,59] and substituted derivative 3b is the first example that the X-ray structure of cyclobuteno-COT has been determined [60]. However, the effect of planarization by the annelation of cyclobutene ring is quite small as predicted by the molecular mechanics calculations [61]. One additional double bond to 3 was shown to be quite effective for planarization of the eight-membered ring and bicyclo[6.2.0]decapentaene 4a [62] and its diphenyl derivative 4b [63] were shown to have a nearly planar conformation. However, the X-ray structural analysis [63] suggested that 4 is not 8π-antiaromatic COT but rather a 10π-aromatic system like azulene. CTOCD-DZ calculations supported the conclusion [64]. Cycloprop[8]annulene 5 has a planarized tub-conformation, and some paratropic ring current was found to be induced as 1H NMR chemical shifts of the protons in the eight-membered ring appears at δ 3.6-3.7 ppm which is ca. 2 ppm upfield shifted from that of parent COT (δ 5.68) [65]. CTOCD-DZ calculations supported the presence of a paratropic ring current in 5 [52]. Here, we also calculated NICS(0) value (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**) and HOMO–LUMO gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) of 3a, 4a, and 5 (Figure 5), and only 5 showed a relatively large positive NICS value in accord with the observed large upfield shift of the ring protons.

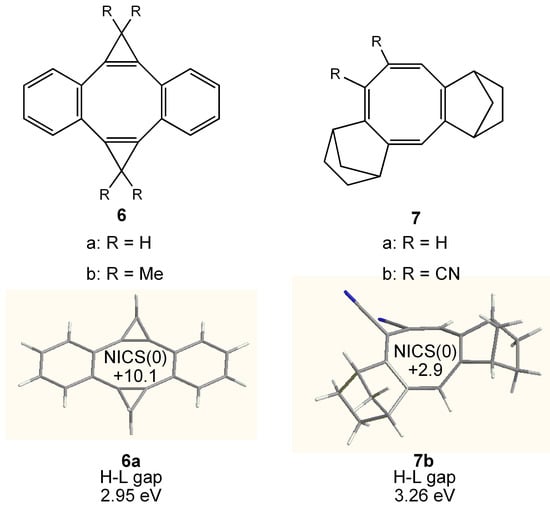

COTs 6 and 7 annelated with two cyclopropene ring or norbornene units (Figure 6) have also been prepared. Concerning about 6, a planar [8]annulene core was demonstrated in 6b [66], but the NICS(0) value of 6a (+10.1) is considerably reduced due to the deformed eight-membered ring and/or the annelation of benzene rings. As for 7a, the author predicted that the COT ring could be planarized by the annelation with the rigid small rings at C1, C2 and C4, C5 position [67]. However, the X-ray structure of 7b revealed that the COT ring is not planar [68] and NICS(0) value of 7b (+2.9) is as small as that of D2d COT at the ground state.

Figure 6.

Chemical structure of bis-cyclopropeno-COT 6 and bis-norborneno-COT 7. Calculated geometry, NICS (0) (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**) and HOMO–LUMO (H-L) gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) of 6a and 7b are also shown.

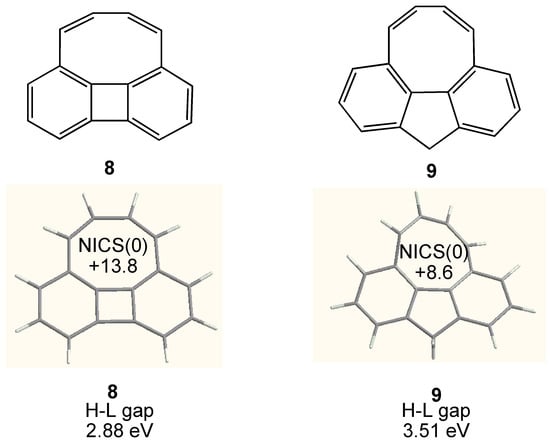

As the second strategy for the planarization of COT ring, the annelation of rigid planar π-systems to COT ring has also been investigated. The first example is COT annelated with biphenylene 8 [69,70]. As shown in Figure 7, the COT ring is almost planar but considerably deformed. Thus, although some upfield shift in 1H NMR of the olefinic protons (δ 4.62) was observed in comparison with those of nonplanar biphenyl analogue (δ 6.82, 6.32) [71], the antiaromatic paratropicity is not so large judging from the NICS(0) value. The reduced antiaromaticity may be caused by the deformed eight-membered ring and/or the annelation of aromatic two benzene units. Similarly, COT annelated with fluorene 9 [71] was prepared and some upfield shift in 1H NMR of the olefinic protons (δ 5.90, 5.68) was also observed. However, the antiaromatic paratropicity is small due to the non planar COT ring.

Figure 7.

Chemical structure of cycloocta[def]biphenylene 8 and cycloocta[def]fluorene 9. Calculated geometry, NICS(0) (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**) and HOMO–LUMO (H-L) gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) of 8 and 9 are also shown.

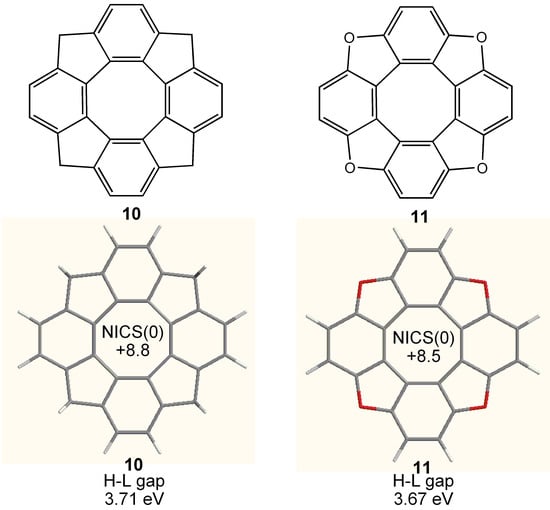

On the other hand, the tetraphenylene completely planarized by four methylene and oxygen bridges 10 [72] and 11 [73] (Figure 8) have a higher D4h symmetry. However, both NICS(0) values exhibit smaller antiaromatic character in the central eight-membered ring than that of 8, suggesting that the paratropicity of the COT ring is weakened by the annelation of aromatic benzene rings [45].

Figure 8.

Chemical structure of bridged tetraphenylenes 10 and 11. Calculated geometry, NICS(0) (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**) and HOMO–LUMO (H-L) gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) of 10 and 11 are also shown.

Thus, the design of complete planarization of the COT ring with substantial paratropicity has been rather difficult and only several types of derivatives have so far been known as summarized below.

3.2. Planar COT Annelated with Four Cyclobutene Rings

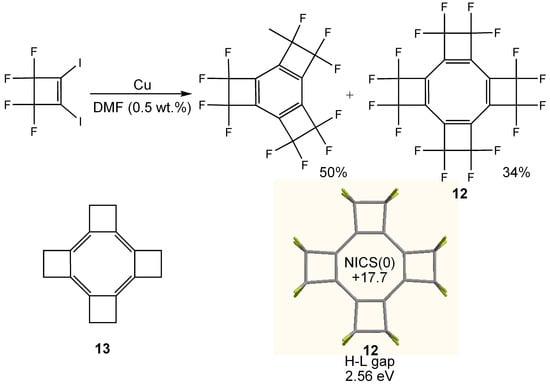

Planar COT 12 tetra-annelated with tetrafluorocyclobutene units has been synthesized by copper-mediated coupling reaction of 3,3,4,4-tetrafluoro-1,2-diiodo-1-cyclobutene in the presence of 0.5 wt.% of DMF (Figure 9) [74]. X-ray crystallography of 12 demonstrated the planar and bond-alternated COT structure with the shorter bonds endocyclic to the cyclobutene rings [75] and the structural features were reproduced by theoretical calculations [76,77]. The position of the double bonds in 12 is in contrast to the structure of hypothetical hydrocarbon analogue 13 in which the shorter bonds are theoretically predicted to be exocyclic to the cyclobutane rings [76].

Figure 9.

Synthetic scheme for 12 and chemical structure of 13. Calculated geometry, NICS(0) (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**) and HOMO–LUMO (H-L) gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) of 12 are also shown.

The color of 12 is deep red, suggesting that 12 has a relatively narrow HOMO–LUMO gap and hence a strong paratropic ring current. In fact, CTOCD-DZ calculations predicted that 12 as well as 13 have a strong paratropic ring current [78]. We also calculated the HOMO–LUMO gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) and NICS(0) value (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**) and the results were 2.56 eV and +17.7 ppm. These values are narrower and larger than those of 3-11. It is interesting to note that 12 has an extraordinarily low reduction potential ( +0.79 V vs SCE; +0.33 V vs Fc/Fc+) owing to lowering of the LUMO level by planarization of COT ring and the accumulated electron-withdrawing effects of sixteen fluorine atoms [79].

3.3. Planar COT Annelated with Plural Bicyclo[2.1.1]hexene Rings

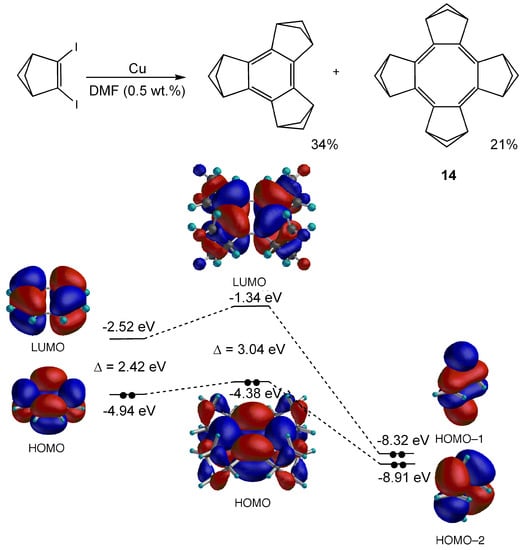

Planar COT 14 tetra-annelated with bicyclo[2.1.1]hexene units has been synthesized by copper-mediated coupling reaction of 1,2-diiodobicyclo[2.1.1]hex-2-ene (Figure 10) [80]. X-ray crystallography of 14 demonstrated the planar and bond-alternated COT structure with the shorter bonds exocyclic to the cyclobutene rings as predicted by the theoretical calculations [76]. The bond-alternation in 14 (ΔRobs = Rendo – Rexo = 1.500(1) – 1.331(1) = 0.169 Å) is much larger than that of 12 (obs: Rendo = 1.353(10), Rexo = 1.425(14) [75]; ΔRcalc = Rexo – Rendo = 1.454 – 1.359 = 0.095 Å (B3LYP/6-31G**)), which would be caused by the annelation with highly strained bicyclo[2.1.1]hexene units. The color of 14 is red with weak absorption band at 459 nm (log ε = 2.11), indicating a relatively narrow HOMO–LUMO gap for an 8π-electron system. However, the NICS value of 14 (+10.6) at the GIAO/HF/6-31+G**//B3LYP/6-31G* level [80] is considerably reduced in comparison with that of D4h COT (+27.2) at the same level, although CTOCD-DZ calculations support that 14 sustains a weak paratropic ring current [78]. The large bond alternation in 14 is not the main reason for the considerable decrease in antiaromatic paratropicity, since a much larger NICS value (+22.1) was calculated for a hypothetical planar COT having exactly the same bond lengths as those in 14 [81]. As described in section 2.2, the HOMO–LUMO transition dominates the total π ring current in planar COT and determines its paratropic nature [50]. Thus, the relatively larger HOMO–LUMO gap (3.04 eV at the B3LYP/6-31G* level) for a planar COT, in which the LUMO level is raised by the orbital interaction with the annelated bicyclic ring (Figure 10), is considered to be the main reason for the reduced antiaromaticity in 14.

Figure 10.

Synthetic scheme for 14 and the HOMO and LUMO calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level for 14 and for D4h COT together with orbital interaction diagrams between the COT and puckered cyclobutane rings of bicyclo[2.1.1]hexene units.

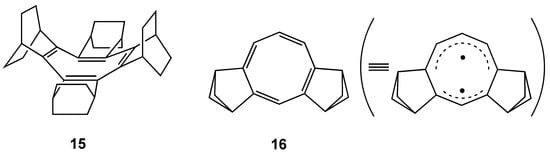

Planar COT 14 has an unusually low oxidation potential (+0.07 V vs Fc/Fc+) and gives a fairly stable radical-cation salt [82]. This is ascribed to the raised HOMO level due to the σ–π conjugative effects of bicyclic frameworks in addition to a narrowed HOMO–LUMO gap by the planarization of COT ring as shown in Figure 10. Interestingly, the longest wavelength absorption (630 nm) of radical cation of planar 14 is blue-shifted from that (745nm) of radical cation of tub-shaped COT fully annelated with bicyclo[2.2.2]octene units 15 (Figure 11) [83], indicating the planarization causes hypsochromic shift contrary to the common sense for effective π-conjugations. This is due to the widening of the HOMO–SOMO gap caused by the raised SOMO (HOMO in neutral COT) and lowered HOMO (HOMO–1 in neutral COT) accompanying the flattening of the COT ring. The lower HOMO–1 level of planar neutral COT may be the principal contributor to the small antiaromatic destabilization for COT ring (See Introduction).

Figure 11.

Chemical structure of COTs fully annelated with bicyclo[2.2.2]octene units 15 and annelated with two bicyclo[2.1.1]hexene units 16.

Another COT annelated with two bicyclo[2.1.1]hexene units 16 (Figure 11) has also been theoretically predicted to have a planar structure [76]. In this compound, singlet diradicaloid state is the minimum energy form just like open-shell singlet state of COT with a D8h structure [14].

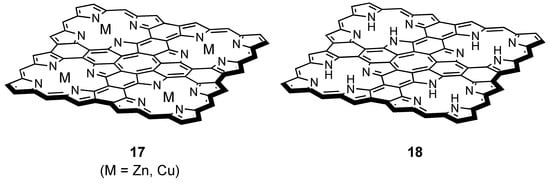

3.4. Planar COT Annelated with Porphyrin Rings

Directly fused tetrameric porphyrin sheets 17 and their free base analogue 18 (Figure 12), which are also calculated to have a planar COT core, have been synthesized [84,85]. The directly meso-meso linked cyclic porphyrin tetramer which is the precursor for 17(Zn), was synthesized through a stepwise coupling reaction sequence. Then the precursor was treated with 30 equiv of DDQ and Sc(OTf)3 to give 17(Zn) as black solid. Free base sheet 18 was obtained by demetallation of 17 [85]. As for the paratropicity of the central COT ring, NICS calculations were performed at the GIAO/B3LYP/6-31G*//B3LYP/6-31G* level (LANL2DZ for zinc atom) and the values were +61.7 for 17(Zn) and +21.7 for 18 (29.2 for D4h COT at the same level) [84]. The distance-dependent NICS at the center of the COT core for 17(Zn) was also performed [86], which was shown to decrease monotonously with increasing distance as shown in the case of cyclobutadiene [87]. Furthermore, the complex of 17(Zn) with 1,4-bis(1-methylimidazol-2-ylethynyl)benzene or 5,15-bis(1-methylimidazol-2-yl)-10,20-dihexylporphyrin experimentally proved the paratropic ring current of the central COT core [84]. However, in spite of the large difference between the NICS values of 17(Zn) and 18, the absorption spectra of 17 and 18 is quite similar [85], suggesting that the HOMO–LUMO gaps of 17 and 18 are almost identical.

Figure 12.

Chemical structure of directly fused tetrameric porphyrin sheets 17 and its free base analogue 18.

3.5. Planar COT Annelated with Thiophene Rings.

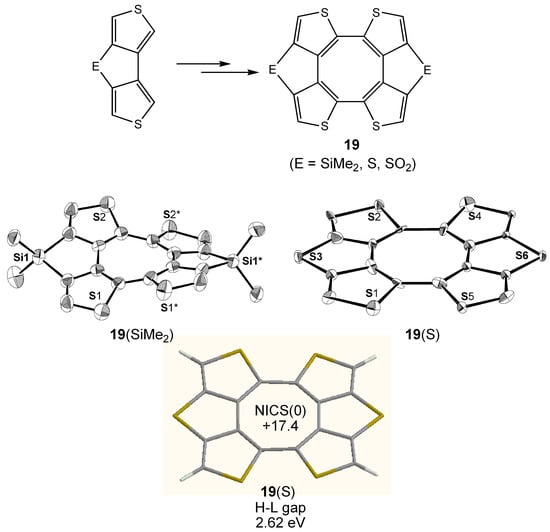

Cyclic tetrathiophenes 19 planarized by dimethylsilyl, sulfur, and sulfone bridges bearing a planarized COT core (Figure 13) have been synthesized by homocoupling of the bridged bithiophene precursors [45]. The bent angle of the central COT rings of 19 can be finely adjusted by using the small differences in the bond lengths between the bridging units and thiophene rings and the planarity is enhanced in the order of 19(S) > 19(SO2) > 19(SiMe2) (See X-ray structures of 19(S) and 19(SiMe2) in Figure 13). From the comparisons of NICS values (19(S): +17.4; 19(SO2): +15.4; 19(SiMe2): +12.7 (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**)) and calculated HOMO–LUMO gaps (19(S): 2.62 eV; 19(SO2): 2.72 eV; 19(SiMe2): 2.87 eV ) of the optimized structures of 19, similar enhancement of the paratropicity and narrowing of the HOMO–LUMO gap with decreasing bent angle of the COT rings as shown in Figure 2 were also demonstrated for 19. It is interesting to note that the NICS value of 19(S) with highest planarity among 19 is larger than those of 3-11 and almost identical to that of 12.

Figure 13.

Synthetic scheme for 19 and X-ray structures of 19(S) and 19(SiMe2). Calculated geometry, NICS(0) (GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G**) and HOMO–LUMO (H-L) gap (B3LYP/6-31G**) of 19(S) are also shown.

The theoretically predicted relationships among the paratropicity, HOMO–LUMO gap, and planarity of the COT ring shown in Figure 2 were also qualitatively proved by means of 1H NMR and UV-vis measurements of 19. In comparison of the 1H NMR chemical shifts of 19 with those of the corresponding precursors, upfield shifts due to a paratropic ring current in the COT ring were observed and the degree of shift increased with increasing planarity of the COT ring. Furthermore the absorption maxima of 19 showed bathochromic shifts with increasing planarity of the COT ring.

4. Stacking of Planar COT Rings

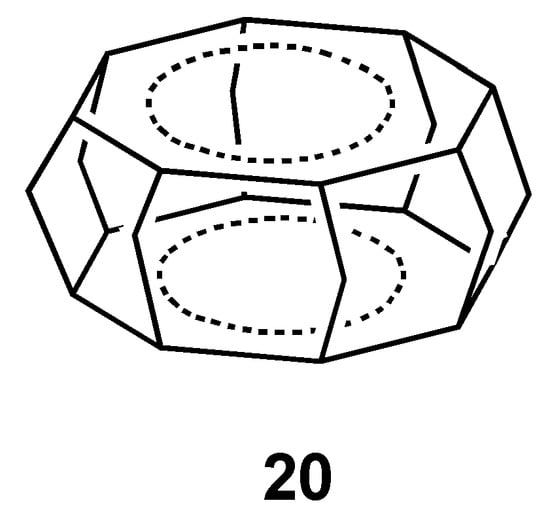

Recently, it has been shown using NICS calculations that stacking of antiaromatic annulene rings into superphane structure can reverse antiaromaticity and result in through-space three-dimensional aromatic character [88]. As for the COT ring system 20 (Figure 14), D8h structure is minimum, indicating that the stacked ring aromaticity causes the bond length equalization. The NICS(0) values of the COT ring (–22.0 at the PW91/IGLOIII//B3LYP/6-311+G**) and superphane center of symmetry (–35.5) predicts the strong diatropicity of the system. From these results as well as the results for other ring size, the authors concluded that “stacking, along with triplet [42] and Möbius strategies [89,90], is the third way to render 4nπ electron system aromatic.” CTOCD-DZ calculations [91] supported the conclusion, whereas an analysis based on energetic criteria using graph theory concluded that the stacking of antiaromatic ring does not bring about aromatic stabilization energy even though the original antiaromaticity is reduced [92].

Figure 14.

Chemical structure of COT superphane 20.

5. Conclusions

Recent studies on aromaticity and antiaromaticity of planar unsubstituted COT based on NICS and CTOCD-DZ calculations have been summarized in section 2. These studies have revealed the paratropicity of D4h and open-shell singlet D8h COTs and diatropicity of triplet D8h COT. Among these types of COTs, synthetically accessible derivatives have so far been limited to bond-alternated D4h type structure, and the antiaromaticity of COTs planarized by annelation with various rigid rings has been assessed by NICS values. For the most classical planarized COTs, however, complete planarization of the ring with substantial paratropicity was not attained, and only a few compounds showed that the NICS(0) value is comparable to or exceeds two-third (+17.7 at the GIAO/HF/6-311+G**//B3LYP/6-31G** level) of that of D4h COT (+26.6). Among them, we have attained a planar COT structure in 19(S) without bulky substituents unlike the other planar COTs, and X-ray crystallography showed a stacking structure [45]. Thus, the structure of 19(S) may be utilized for study on an intermolecular antiaromatic-antiaromatic interaction [88] by controlling the stacking manner with additional substituents at the side positions. Such experiments may also lead to these compounds becoming unique candidates for efficient organic electronic devices, in which the use of antiaromatic ring has not been tested.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (No. 20036042, Synergy of Elements) and on Innovative Areas (No. 21108519, “π-Space”) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

References

- Willstätter, R.; Waser, E. Über Cyclo-octatetraen. Chem. Ber. 1911, 44, 3423–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willstätter, R.; Heidelberger, M. Zur Kenntnis des Cyclo-octatetraens. Chem Ber. 1913, 46, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karle, I.L. An Electron Diffraction Investigation of Cyclooctatetraene and Benzene. J. Chem. Phys. 1952, 20, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiansen, O.; Hedberg, L.; Hedberg, K. Reinvestigation of the Molecular Structure of 1,3,5,7- Cyclooctatetraene by Electron Diffraction. J. Chem. Phys. 1957, 27, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traetteberg, M. The Molecular Structure of 1,3,5,7-Cyclo-octatetraene. Acta Chem. Scand. 1966, 20, 1724–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordner, J.; Parker, R.G.; Stanford, R.H. The Crystal Structure of Octamethylcycloocta-tetraene. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1972, 28, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hückel, E. Quantentheoretische Beiträge zum Benzolproblem. Z. Phys. 1931, 70, 204–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bally, T. Cyclobutadiene: The Antiaromatic Paradigm? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6616–6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, K.B. Antiaromaticity in Monocyclic Conjugated Carbon Rings. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.D.; Tidwell, T.T. Antiaromaticity in Open-Shell Cyclopropenyl to Cycloheptatrienyl Cations, Anions, Free Radicals, and Radical Ions. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1333–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, R.; Brown, J.; Gajewski, J.J. Antiaromaticity of Cyclopropenyl Anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 4383–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, R. Antiaromaticity. Acc. Chem. Res. 1973, 6, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, R. Small Antiaromatic Rings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1968, 7, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrovat, D.A.; Borden, W.T. CASSCF Calculations Find that a D8h Geometry is the Transition State for Double Bond Shifting in Cyclooctatetraene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 5879–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, W.T.; Davidson, E.R. Effects of electron repulsion in conjugated hydrocarbon diradicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 4587–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, W.T.; Iwamura, H.; Berson, J.A. Violations of Hund’s Rule in Non-Kekule Hydrocarbons: Theoretical Prediction and Experimental Verification. Acc. Chem. Res. 1994, 27, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M.J.S.; Harget, A.J.; Haselbach, E. Cyclooctatetraene and Ions Derived from It. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 7521–7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermer, O.; Klärner, F.-G.; Wette, M. Planarization of Unsaturated Rings. Cycloheptatriene with a Planar Seven-Membered Ring. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 4908–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, L. A.; Trova, M. P.; Luo, J.; Clough, A. E.; Anderson, L. B. Synthesis and Dynamic Behavior of (1,5)Cyclooctatetraenophanes. Effect of Distal Atom Bridging on Racemization Rates and Electrochemical Reducibility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, L.A.; Wang, T.-Z.; Luo, J.; Cottrell, C.E.; Clough, A.E.; Anderson, L.B. Is Pseudorotation the Operational Pathway for Bond Shifting within [8]Annulenes? Probe of Planarization Requirements by 1,3-Annulation of the Cyclooctatetraene Ring. Kinetic Analysis of Racemization and 2-D NMR Quantitation of π-Bond Alternation and Ring Inversion as a Function of Polymethylene Chain Length. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette, L.A. The Current View of Dynamic Change within Cyclooctatetraenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993, 26, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anet, F.A.L.; Bourn, A.J.R.; Lin, Y.S. Ring Inversion and Bond Shift in Cyclooctatetraene Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3576–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oth, J.F.M. Conformational Mobility and Fast Bond Shift in the Annulenes. Pure Appl. Chem. 1971, 25, 573–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Lee, H.S.; Gareyev, R.; Wenthold, P.G.; Lineberger, W.C.; DePuy, C.H.; Bierbaum, V.M. Experimental and Computational Studies of the Structures and Energetics of Cyclooctatetraene and Its Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 7863–7864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenthold, P.G.; Hrovat, D.A.; Borden, W.T.; Lineberger, W.C. Transition-State Spectroscopy of Cyclooctatetraene. Science 1996, 272, 1456–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anet, F.A.L. The Rate of Bond Change in Cycloöctatetraene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 671–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, L.A. Ring Inversion and Bond Shifting Energetics in Substituted Chiral Cyclooctatetraenes. Pure Appl. Chem. 1982, 54, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, K.; Nishinaga, T.; Aonuma, S.; Hirosawa, C.; Takeuchi, K.; Lindner, H.J.; Richter, J. Synthesis, Structure, and Reduction of the Cyclooctatetraene Tetra-annelated with Bicyclo[2.2.2]-octene Frameworks. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 6767–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Seminario, J.M. Antiaromaticity in Relation to 1,3,5,7-Cyclooctatetraene Structures. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1994, 50, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glukhovtsev, M.N.; Bach, R.D.; Laiter, S. Isodesmic and homodesmotic stabilization energies of [n]annulenes and their relevance to aromaticity and antiaromaticity: is absolute antiaromaticity possible? J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 1997, 417, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuenich, D.; Hess, K.; Köhler, F.; Herges, R. Anisotropy of the Induced Current Density (ACID), a General Method To Quantify and Visualize Electronic Delocalization. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3758–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heine, T.; Corminboeuf, C.; Seifert, G. The Magnetic Shielding Function of Molecules and Pi-Electron Delocalization. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3889–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poater, J.; Duran, M.; Solà, M.; Silvi, B. Theoretical Evaluation of Electron Delocalization in Aromatic Molecules by Means of Atoms in Molecules (AIM) and Electron Localization Function (ELF) Topological Approaches. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3911–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, J.A.N.F.; Mallion, R.B. Aromaticity and Ring Currents. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1349–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauben, H.J., Jr.; Wilson, J.D.; Laity, J.L. Diamagnetic Susceptibility Eexaltation as a Criterion of Aromaticity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauben, H.J., Jr.; Wilson, J.D.; Laity, J.L. Diamagnetic Susceptibility Exaltation in Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wannere, C.S.; Corminboeuf, C.; Puchta, R.; Schleyer, P.v.R. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts (NICS) as an Aromaticity Criterion. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleyer, P.v.R.; Maerker, C.; Dransfeld, A.; Jiao, H.; Hommes, N.J.R.v.E. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts: A Simple and Efficient Aromaticity Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 6317–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.A.; Bader, R.F.W. Calculation of Magnetic Response Properties using a Continuous Set of Gauge Transformations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993, 210, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coriani, S.; Lazzeretti, P.; Malagoli, M.; Zanasi, R. On CHF Calculations of Second-Order Magnetic Properties using the Method of Continuous Ttransformation of Origin of the Current Density. Theor. Chim. Acta 1994, 89, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A related review was reported in 2001. Klärner, F.-G. About the Antiaromaticity of Planar Cyclooctatetraene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3977–3981. [Google Scholar]; for reviews on the chemistry of cyclooctatetraene, see: Schröder, G. Cyclooctatetraen; Verlag Chemie: Weinheim, Germany, 1965. [Google Scholar]; Weinheim Fray, G.I.; Saxton, R.G. The Chemistry of Cyclooctatetraene and Its Derivatives; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]; Nishinaga, T. Cyclooctatetraenes. Sci. Synth. 2009, 45a, 383–406. [Google Scholar]

- Gogonea, V.; Schleyer, P.v.R.; Schreiner, P.R. Consequences of Triplet Aromaticity in 4nπ-Electron Annulenes: Calculation of Magnetic Shieldings for Open-Shell Species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1945–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadakov, P.B. Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity in the Low-Lying Electronic States of Cyclooctatetraene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 12707–12713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krygowski, T.M.; Pindelska, E.; Cyrański, M.K.; Häfelinger, G. Planarization of 1,3,5,7-Cyclooctatetraene as a Result of a Partial Rehybridization at Carbon Atoms: an MP2/6-31G* and B3LYP/6-311G** Study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 359, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmae, T.; Nishinaga, T.; Wu, M.; Iyoda, M. Cyclic Tetrathiophenes Planarized by Silicon and Sulfur Bridges Bearing Antiaromatic Cyclooctatetraene Core: Syntheses, Structures, and Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, N.C. Quantum Organic Photochemistry. II. Resonance and Aromaticity in the Lowest 3ππ* State of Cyclic Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 4941–4948. [Google Scholar]

- Aihara, J. Aromaticity-Based Theory of Pericyclic Reactions. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1978, 51, 1788–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jug, K.; Malar, E.J.P. Geometry of Triplets and Dianions of Aromatic and Antiaromatic Systems. J. Mol. Struct. (THEOCHEM) 1987, 153, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanger, A. Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shifts (NICS): Distance Dependence and Revised Criteria for Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, E.; Fowler, P.W. Four- and Two-Electron Rules for Diatropic and Paratropic Ring Currents in Monocyclic π-Systems. Chem. Commun. 2001, 2220–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, E.; Soncini, A.; Fowler, P.W. Full Spectral Decomposition of Ring Currents. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 12882–12886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havenith, R.A.; Fowler, P.W.; Jenneskens, L.W. Persistence of Paratropic Ring Currents in Nonplanar, Tub-Shaped Geometries of 1,3,5,7-Cyclooctatetraene. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 1255–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.N.C.; Garratt, P.J.; Sondheimer, F. Unsaturated Eight-Membered Ring Compounds. XI. Synthesis of sym-Dibenzo-1,5-cyclooctadiene-3,7-diyne and sym-Dibenzo-1,3,5- cyclooctatrien-7-yne, Presumably Planar Conjugated Eight-Membered Ring Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 5604–5605. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, H.N.C.; Sondheimer, F. Synthesis and Reactions of 5,6,11,12-Tetradehydrodibenzo[a,e]cyclooctene and 5,6-Didehydrodibenzo[a,e]cyclooctene. Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.Z.; Sondheimer, F. The Planar Dehydro[8]annulenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 1982, 15, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destro, R.; Pilati, T.; Simonetta, M. Crystal structure of 5,6,11,12-tetradehydrodibenzo[a,e]cyclooctene (sym-dibenzo-1,5-cyclooctadiene-3,7-diyne). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzger, A.J.; Vollhardt, K.P.C. Benzocyclynes Adhere to Hückel’s Rule by the Ring Current Criterion in Experiment (1H NMR) and Theory (NICS). Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 6791–6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elix, J.A.; Sargent, M.V.; Sondheimer, F. Bicyclo[6.2.0]deca-1,3,5,7-tetraene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Elix, J.A.; Sargent, M.V.; Sondheimer, F. Unsaturated 8-Membered Ring Compounds. VIII. Photochemistry of 7,8-Dimethylene-1,3,5-cyclooctatrienes. Synthesis of Bicyclo[6.2.0]deca- 1,3,5,7-tetraene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 969–973. [Google Scholar]

- Pirrung, M.C.; Krishnamurthy, N.; Nunn, D. S.; McPhail, A. T. Synthesis, Structure, and Properties of a 2-(Trimethylsilyl)cyclobutenocyclooctatetraene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 4910–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, L.A.; Wang, T.Z.; Cottrell, C.E. Flattening of the Cyclooctatetraene Ring by Annulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 3730–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, M.; Oikawa, H. The Synthesis of Bicyclo[6.2.0]decapentaene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuto, C.; Oda, M. Crystal and Molecular Structure of 9,10-Diphenylbicyclo[6.2.0]decapentaene a 10 π Aromatic Compound. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havenith, R.W.A.; Lugli, F.; Fowler, P.W.; Steiner, E. Ring Current Patterns in Annelated Bicyclic Polyenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 5703–5708. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesewetter, M.K.; Reiter, R.C.; Stevenson, C.D. The Second Cyclopropannulene: Cycloprop-[8]annulene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1118–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dürr, H.; Klauck, G.; Peters, K.; von Schnering, H.G. A Novel Planar Antiaromatic Dibenzo[8]annulene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1983, 22, 332–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermer, O.; Klärner, F.-G.; Wette, M. Planarization of Unsaturated Rings. Cycloheptatriene with a Planar Seven-Membered Ring. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 4908–4911. [Google Scholar]

- Klärner, F.-G.; Ehrhardt, R.; Bandmann, H.; Boese, R.; Bläser, D.; Houk, K.N.; Beno, B.R. Pressure-Induced Cycloadditions of Dicyanoacetylene to Strained Arenes: The Formation of Cyclooctatetraene, 9,10-Dihydronaphthalene, and Azulene Derivatives; A Degenerate [1,5] Sigmatropic Shift - Comparison between Theory and Experiment. Chem. Eur. J. 1999, 5, 2119–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, C.F., Jr.; Uetrecht, J.P.; Grohman, K.K. Preparation of Cycloocta[def]biphenylene, a Novel Benzenoid Antiaromatic Hydrocarbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 2532–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, C.F., Jr.; Uetrecht, J.P.; Grantham, G.D.; Grohmann, K.G. Synthesis and Properties of Cycloocta[def]biphenylene, a Stable Benzenoid Paratropic Hydrocarbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 1914–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, I.; Rabinovitz, M. Cycloocta[def]fluorene: a Planar Cyclooctatetraene Derivative. Paratropicity of Hydrocarbon and Anion. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 1628–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwinkel, D.; Reiff, G. Cyclooctatetraene Systems Flattened by Steric Constraints. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1970, 9, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, R.; Abdelwahed, S.H. Soluble Cycloannulated Tetroxa[8]circulane Derivatives: Synthesis, Optical and Electrochemical Properties, and Generation of Their Robust Cation-Radical Salts. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 5267–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulen, R.L.; Choi, S.K.; Park, J.D. Copper Coupling of 1-Chloro-2-iodo- and 1,2-Diiodo-perfluorocycloalkenes. J. Fluorine Chem. 1973/74, 3, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, F.W.B.; Willis, A.C.; Cullen, W.R.; Soulen, R.L. Perfluorotetracyclobutacyclo-octatetraene; a Planar Eight-Memberedring System; X-ray Crystal Structure. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1981, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldridge, K.K.; Siegel, J.S. Quantum Mechanical Designs toward Planar Delocalized Cyclooctatetraene: A New Target for Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 1755–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, G.R.; Hrovat, D.A.; Wei, H.; Borden, W.T. Why Does Perfluorination Render Bicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene Stable toward Dimerization? Calculations Provide the Answers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 12020–12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W.; Havenith, R.W.A.; Jenneskens, L.W.; Soncini, A.; Steiner, E. Paratropic Delocalized Ring Currents in Flattened Cyclooctatetraene Systems with Bond Alternation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1558–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, W.E.; Ferraris, J.P.; Soulen, R.L. Electrochemistry of Perfluorotetracyclobuta-1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene, a Powerful Neutral Organic Oxidant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 5322–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, A.; Komatsu, K. Efficient Synthesis of Benzene and Planar Cyclooctatetraene Fully Annelated with Bicyclo[2.1.1]hex-2-ene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 1768–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishinaga, T.; Uto, T.; Inoue, R.; Matsuura, A.; Treitel, N.; Rabinoviz, M.; Komatsu, K. Antiaromaticity and Reactivity of a Planar Cyclooctatetraene Fully Annelated with Bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane Units. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 2067–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishinaga, T.; Uto, T.; Komatsu, K. Novel Cyclooctatetraene Radical Cation Planarized by Full Annelation with Bicyclo[2.1.1]hexene Units. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4611–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishinaga, T.; Komatsu, K.; Sugita, N.; Lindner, H.J.; Richter, J. First X-ray Structure of a Cyclooctatetraene Cation Radical: the Hexachloroantimonate of the Tetrakis(bicyclo[2.2.2]octeno)cyclooctatetraene Cation Radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 11642–11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Aratani, N.; Shinokubo, H.; Takagi, A.; Kawai, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Yoon, Z.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Ahn, T.K.; Kim, D.; Muranaka, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Osuka, A. A Directly Fused Tetrameric Porphyrin Sheet and Its Anomalous Electronic Properties That Arise from the Planar Cyclooctatetraene Core. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 4119–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Aratani, N.; Furukawa, K.; Osuka, A. Synthesis and Characterizations of Free Base and Cu(II) Complex of a Porphyrin Sheet. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 11433–11439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Aratani, N.; Osuka, A. Experimental and Theoretical Investigations into the Paratropic Ring Current of a Porphyrin Sheet. Chem. Asian. J. 2007, 2, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleyer, P. v. R.; Manoharan, M.; Wang, Z.-X.; Kiran, B.; Jiao, H.; Puchta, R.; van Eikema Hommes, N. J. R. Dissected Nucleus-Independent Chemical Shift Analysis of π-Aromaticityand Antiaromaticity. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 2465–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corminboeuf, C.; Schleyer, P.v.R.; Warner, P. Are Antiaromatic Rings Stacked Face-to-Face Aromatic? Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3263–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepa, H.S. Möbius Aromaticity and Delocalization. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3697–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Z.S.; Osuka, A.; Kim, D. Möbius Aromaticity and Antiaromaticity in Expanded Porphyrins. Nature Chem. 2009, 1, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, D.E.; Fowler, P. W. Stacked-Ring Aromaticity: An Orbital Model. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5573–5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aihara, J.-i. Origin of Stacked-Ring Aromaticity. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 7945–7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).