1. Introduction

One of the most intelligent models proposed for the propagation of solitons across transcontinental and transoceanic distances is the concatenation model. This happened during 2014 [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Later, this model was extended to accommodate dispersive solitons that came to be known as the dispersive concatenation model. Several features of these two models were sequentially explored and reported. These include the retrieval of the 1–soliton solutions by the method of undetermined coefficients, identifying their conservation laws, and extending these laws with power–law of self-phase modulation. The models were also studied with nonlinear chromatic dispersion for locating the quiescent optical solitons. Later, the models were also addressed in birefringent fibers, which addressed the gap solitons, retrieved the soliton solutions with fractional temporal evolution, and a plethora of similar features [

6,

7,

8]. From a physical perspective, the concatenation model describes the evolution of ultra-short optical pulses in nonlinear media where several higher-order dispersive and nonlinear effects of different origins act simultaneously. It can be interpreted as an averaged equation for propagation through a chain of fiber segments, each governed by a different higher-order NLS-type equation such as the Lakshmanan–Porsezian–Daniel (LPD) and Sasa–Satsuma (SSE) models. This unified description allows one to capture the combined impact of even- and odd-order corrections and has been employed to predict dark solitary pulses, moving fronts, periodic wave trains, multi-soliton bound states, and related nonlinear structures in realistic optical settings. Mathematically, the governing equation is a higher-order member of the nonlinear Schrödinger hierarchy introduced by Ankiewicz, Akhmediev and co-workers, which remains integrable for specific parameter choices and supports rich soliton and rogue-wave dynamics. Later, many such models were similarly addressed, and several of their hidden features were partially recovered [

9,

10,

11].

We start from the dimensional concatenation model for the slowly varying envelope

of the optical field:

where

Z denotes the propagation distance and

T is the retarded time in the co-moving frame. Here

is the group-velocity dispersion coefficient, the constants

and

measure the overall strength of even and odd higher-order corrections, respectively, and the real coefficients

(

) collect contributions from fourth-order dispersion, derivative-type nonlinearities, and effective quintic nonlinear response.

To obtain a dimensionless form we introduce the scalings

with

being a characteristic pulse amplitude,

a temporal width and

a characteristic propagation length. Under this transformation,

Substituting into the dimensional model, dividing by

and collecting terms yields

where the dimensionless parameters are defined by

Renaming the parameter combinations as

a,

,

, and

(

) gives precisely the dimensionless concatenation model written in Equation (

1). This concatenation model, introduced in [

12], unifies three well-known higher-order NLEEs describing soliton propagation: the NLSE, the Lakshmanan–Porsezian–Daniel (LPD) equation [

13] and the Sasa–Satsuma Equation (SSE) [

14]. This approach models propagation through a sequence of fiber segments, each governed by different dispersion and nonlinear characteristics, enabling the description of richer dynamics than any of the individual equations alone. Since its inception, the concatenation model has inspired studies on bifurcation analysis, numerical simulations, Painlevé integrability, conservation laws, quiescent soliton dynamics, and extensions to fibers with power-law nonlinearity. In the absence of self-phase modulation (SPM), its dimensionless form is given by:

where

is the complex-valued envelope of the optical field,

x and

t denote the spatial and temporal coordinates,

a is the chromatic dispersion coefficient,

and

represent the strengths of the higher-order terms,

(

) are real parameters, and ‘

*’ denotes complex conjugation. The first two terms correspond to the NLSE (without SPM) with chromatic dispersion, the terms with

arise from the LPD equation, and the terms with

are from the SSE. This concatenated structure allows the model to capture a richer set of higher-order dispersion and nonlinear effects in optical fibers.

It is useful to emphasize how Equation (

1) recovers several standard models as special cases. If, in addition to the chromatic-dispersion term

, we reintroduce the usual cubic Kerr self-phase modulation term

and set

, the governing equation reduces, after nondimensionalization, to the classical cubic nonlinear Schrödinger Equation (NLSE) used to model pulse propagation in single-mode fibers. Choosing

while retaining the terms proportional to

yields the Lakshmanan–Porsezian–Daniel (LPD) equation, whereas

and

give the Sasa–Satsuma equation with third-order dispersion and derivative nonlinearities. Thus the concatenation model (1) unifies the NLSE, LPD, and SSE within a single framework, and the soliton families constructed below can be specialized by appropriate choices of

and

to provide solutions for these reduced equations.

Over the years, numerous analytical and numerical methods have been developed to solve NLEEs arising in optical fiber models. Analytical techniques include the inverse scattering transform (IST) [

15], Hirota’s bilinear method [

16], Bäcklund and Darboux transformations [

17], Lie symmetry analysis [

18,

19], and Painlevé analysis [

20]. Other effective approaches comprise the tanh–coth method [

21], the sine–cosine method [

22], the

-expansion method [

23], the F-expansion method [

24], and the Jacobi elliptic function expansion method [

25], each providing different classes of closed-form solutions. The Kumar–Malik method [

26] is another powerful tool for generating exact traveling wave solutions to nonlinear evolution equations via auxiliary equation approaches.

Equation (

1) in its concatenated form was first proposed by Triki et al. [

12] as an extended nonlinear Schrödinger equation incorporating both even and odd higher-order dispersive and nonlinear terms. After suitable nondimensionalization, their governing equation coincides with (1) up to a relabeling of parameters and was used to describe dark solitary pulses, optical shock-type fronts, and periodic waves in fibers with a broad spectrum of higher-order effects. Since then, Equation (

1) and closely related concatenation models have been studied by several methods: the trial-equation approach [

27], Laplace–Adomian decomposition [

28], extended tanh and enhanced Kudryashov schemes for power-law nonlinearities [

29], the complete discriminant system method [

30], and bifurcation and phase-portrait analysis [

31]. These studies have mainly focused on particular nonlinearities or on numerical aspects, whereas here we combine Lie symmetry reduction with the Kumar–Malik method to obtain new families of exact soliton solutions for the Kerr concatenation model.

To the best of our knowledge, the optical soliton solutions of the concatenation model (

1) have not been previously obtained using a combination of Lie symmetry analysis and the Kumar–Malik method. This two-stage methodology enables systematic reduction via symmetries followed by the construction of exact soliton solutions, including Jacobi elliptic, trigonometric, and hyperbolic forms. The present work fills this gap by:

(i) Determining the full Lie point symmetry algebra of the concatenation model and deriving a fourth-order scalar similarity ODE that encodes the interplay of even and odd higher-order dispersive and nonlinear terms;

(ii) Solving this reduced ODE via the Kumar–Malik auxiliary-equation approach to obtain seventeen families of exact traveling-wave solutions in Jacobi elliptic, hyperbolic, trigonometric, and exponential form, together with their existence conditions;

(iii) Showing how these solutions specialize, through appropriate choices of the parameters and , to soliton solutions of the Lakshmanan–Porsezian–Daniel (LPD) equation and to other limiting models within the concatenation hierarchy; and

(iv) Illustrating the physical characteristics of representative dark and bright solitons and discussing parameter regimes in which the concatenation model supports localized and periodic nonlinear wave patterns.

Building on these developments,

Section 2 applies Lie symmetry analysis to determine the symmetries admitted by the proposed model. In

Section 3, these symmetries are used to construct the corresponding similarity variables, which in turn reduce the governing NLEEs to ODEs.

Section 4 applies the Kumar–Malik method to the reduced ODEs to obtain exact optical soliton solutions.

Section 5 presents graphical representations of the solutions to the model. Finally, in

Section 6 the conclusions drawn from the study are presented.

2. Lie Symmetry Analysis

The Lie symmetry approach provides a systematic and algebraic framework for reducing nonlinear evolution equations (NLEEs) to ordinary differential equations (ODEs) by exploiting their admitted continuous point symmetries [

18]. Each one-parameter symmetry group generates invariants and similarity variables that lower the effective number of independent variables, thereby transforming the original PDE (or system of PDEs) into a typically more tractable ODE (or system of ODEs). In this section, we apply this methodology to the concatenation model (

1), first by decomposing the complex field into its real and imaginary parts and then by determining the full Lie algebra of point symmetries associated with the resulting real system.

Now, substituting

into Equation (

1) and separating the real and imaginary parts yields the following system of partial differential equations:

System (

2) is a coupled fourth-order dispersive–nonlinear system for the real-valued envelope components

and

. The parameters

a,

,

and

(

) encode, respectively, the chromatic dispersion, higher-order dispersive corrections, and several distinct nonlinear contributions inherited from the NLSE, LPD, and SSE parts of the concatenation model (

1). Our goal is to determine the Lie point symmetries of (

2) and then employ them to construct symmetry reductions leading to ODEs.

The decomposition

is not only natural from a physical viewpoint—

u and

v represent the in-phase and quadrature components of the complex envelope—but it is also convenient mathematically. The standard Lie symmetry machinery is formulated for systems of real differential equations [

32], so rewriting the complex concatenation model as the coupled real system (2) allows us to apply Lie’s algorithm directly in the

variables while automatically preserving the complex conjugation structure

; see also [

33] for a similar treatment of complex NLS-type models.

Consider a one-parameter Lie group of infinitesimal transformations, given by:

where

,

,

and

denote the infinitesimal components of the generator in the

x-,

t-,

u- and

v-directions, respectively, and

is the group parameter. These transformations are required to map any solution of Equation (

1) (equivalently, of system (

2)) into another solution, thereby preserving the invariance of the model under the associated Lie group.

The associated vector field is written as:

To characterize all admissible point symmetries, we impose the standard Lie invariance condition on the solution manifold of (

2). This requires the fourth prolongation of

X to annihilate the system whenever the latter is satisfied, which yields an overdetermined linear system (the determining equations) for the unknown infinitesimals

,

,

, and

. To determine the symmetries of the equation, we apply the invariance condition:

where

denotes the fourth-order prolongation of

X and is given by:

The prolonged coefficients are computed using total derivatives:

where

and

denote total derivative operators with respect to

x and

t, respectively, as defined in [

18].

By applying the invariance criteria (

5) to Equation (

2), we have:

Equating to zero the coefficients of the functionally independent monomials in the derivatives of

u and

v in (

6) results in a linear, overdetermined system of PDEs for the infinitesimals

,

,

and

. This is the standard determining system associated with the Lie point symmetries of the coupled system (

2). Substituting the expressions for

into Equation (

6), we obtain the following determining system:

Thus,

depends only on

v and is linear in that variable, while

and

are constant. Furthermore, the coupling relation

shows that the infinitesimals in the

u- and

v-directions are not independent, but instead generate a rotation in the

-plane. Solving the above NLEE system, we get the following symmetries:

Using the above values of

,

,

, and

yields the following three vector fields, which generate the symmetries of system (

2):

Here

and

represent spatial and temporal translations, respectively, while

generates a phase rotation of the complex field

. Together, these vector fields span a three-dimensional Lie algebra of point symmetries, which will be employed in the next section to construct similarity variables and perform symmetry reductions of the concatenation model.

3. Symmetry Reduction

We now exploit the Lie point symmetries identified in

Section 2 to reduce the governing concatenation model (

1) to an ODE. Since

and

generate translations in

x and

t, and

corresponds to a phase rotation in the

-plane, a natural choice is to consider a generic linear combination of these generators,

where

and

are real constants that will later be related to the soliton velocity and wave number. The invariants of this generator yield the similarity variables and the associated reduction.

The symmetry generators in (

9) mutually commute,

so they span a three-dimensional Abelian Lie algebra. Consequently, any real linear combination of

,

and

of the form chosen above is again an infinitesimal symmetry of the concatenation model. Nontrivial traveling-wave reductions are obtained by taking

and

nonzero, with the stationary/steady and pure phase-rotation cases recovered as limiting choices. The corresponding invariants then lead directly to the similarity variables in (

11) and (

12).

The symmetry reduction of Equation (

1) with respect to the vector field

, where

and

are arbitrary constants, is obtained from Lagrange’s auxiliary equations:

Solving the characteristic system (

10) proceeds by first combining the

x- and

t-equations, which yields a traveling-wave type invariant

so that all field quantities may be expressed as functions of

only. The last two fractions in (

10) describe the orbits in the

-plane generated by

, which correspond to rotations. It is therefore convenient to parameterize

u and

v in polar form, with

the real amplitude and

the phase. Solving Equation (

10) gives the similarity variables

where

The phase

Q is chosen to be linear in

x and

t, with real parameters

(wave number),

(frequency) and an arbitrary constant phase shift

. In terms of the original complex field, the similarity ansatz (11) takes the compact form

Substituting the ansatz (

12) into the concatenation model (

1), and separating the real and imaginary parts, yields the reduced system (

13). Imposing the compatibility conditions (

14) and (

15) eliminates the mixed derivative terms and leads to the single scalar ODE (

16) for the real profile

. Thus every solution

of (

16), together with parameters satisfying (

14) and (

15), generates through (

12) an exact solution of the original concatenation model (

1).

We emphasize that the choice

in (

11) is purely conventional: changing

to

corresponds to reversing the propagation direction of the traveling wave without altering its shape. Hence the negative sign in front of

entails no loss of generality and is adopted only to simplify subsequent formulas.

Substituting Equation (

12) into Equation (

1), and then separating the real and imaginary parts, yields the following reduced ODE system:

System (

13) describes the evolution of the real amplitude

in the traveling frame determined by

. The first equation arises from the imaginary part of the concatenation model, while the second corresponds to the real part. In order to obtain a single scalar ODE for

, we now impose compatibility conditions on the parameters that eliminate the mixed derivative terms. Taking the soliton speed

and wave number

as:

with parametric restriction

system (

13) simplifies to the following equation:

where

Equation (

16) is the fourth-order nonlinear ODE governing the similarity profile

associated with the Lie-symmetric traveling-wave reduction of the concatenation model (

1). The coefficients

in (

17) explicitly encode the contribution of the higher-order dispersion and nonlinear effects through the parameters

a,

,

and

. In the next section, this reduced ODE will be solved by means of the Kumar–Malik method, leading to a rich family of optical soliton solutions in terms of Jacobi elliptic, hyperbolic and trigonometric functions.

4. Soliton Solutions

The construction of optical soliton solutions for the concatenation model requires reducing the governing nonlinear evolution equation into a tractable form that admits closed–form analytical solutions [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Following the symmetry reductions obtained in the preceding sections, the resulting scalar ordinary differential equation captures the essential balance between dispersion and nonlinear effects that govern soliton formation. To systematically extract explicit solution structures, including Jacobi elliptic, hyperbolic, and trigonometric forms, we employ the Kumar–Malik method, an efficient auxiliary-equation-based technique that has proven effective for a wide class of nonlinear wave models. This method enables the derivation of diverse soliton profiles by expanding the reduced solution in terms of an appropriate nonlinear auxiliary function and determining the associated parameter constraints.

The reduced similarity Equation (

16) is a fourth-order ODE involving quintic, cubic and derivative nonlinearities. Conventional analytical tools such as the inverse scattering transform or Hirota’s bilinear method are most effective for completely integrable equations and become difficult to apply to (16) without imposing additional parameter constraints. Likewise, standard expansion schemes such as the tanh-, sine–cosine-,

F-, or

-methods typically lead to large, highly coupled algebraic systems when applied to high-order equations of this type. In contrast, the Kumar–Malik approach [

26] expresses the traveling-wave profile as a low-degree polynomial in an auxiliary function

that satisfies a first-order quartic ODE.

By choosing different parameter regimes for this auxiliary equation, one obtains Jacobi elliptic, hyperbolic, trigonometric, and exponential solutions in a unified way. This strategy has already proved effective for generalized KdV-type equations and other nonlinear evolution equations [

26], and here it allows us to treat Equation (

16) directly, without requiring integrability or additional simplifying assumptions. The seventeen solution families listed in Cases 1–4 below are all generated from the single auxiliary Equation (

21) merely by varying the coefficients

, which illustrates the flexibility and efficiency of the Kumar–Malik method for the concatenation model.

In this section, the solutions of Equation (

1) are obtained by solving Equation (

16) using the Kumar–Malik method as follows.

4.1. Kumar–Malik Method

The Kumar–Malik method offers a systematic procedure for deriving exact traveling-wave solutions of nonlinear ODEs by expressing the solution through an auxiliary function that satisfies a parametrized differential equation. This approach simplifies the reduced equation into an algebraic system, enabling the construction of various soliton profiles for the concatenation model.

The Kumar–Malik approach may be systematically outlined through the following methodological steps [

26]:

where

is the unknown function, and the prime denotes differentiation with respect to

.

where

are constants to be determined, and

satisfies the auxiliary equation

with

being arbitrary parameters.

Step–3: Determine the positive integer

N by applying the homogeneous balance principle to the leading-order terms in Equation (

18).

Step–4: Substitute the ansatz (

19) into Equation (

18), and eliminate higher-order derivatives of

using the auxiliary Equation (

20). This results in a polynomial expression in

. By setting the coefficients of each power of

to zero, a system of algebraic equations is obtained. Solving this system yields the values of the unknown constants

. Substituting these back into Equation (

19) gives the explicit form of the solution

to the original nonlinear ODE (

18).

Soliton Solutions to the Auxiliary Equation (20)

In this subsection, we construct explicit solutions of the auxiliary nonlinear ordinary differential equation

in terms of Jacobi elliptic, hyperbolic, and trigonometric functions. The classification is based on different parameter regimes of

, where

.

Throughout the paper, the values of

and

are taken as follows:

These solutions are bounded periodic wave solutions of cn and dn types.

These solutions are bounded periodic wave solutions of cn and dn types.

These solutions are singular periodic wave solutions of nc and nd types.

These solutions are singular periodic wave solutions of nc and nd types.

These solutions are singular periodic wave solutions of ns type and bounded periodic wave solutions of sn type.

These solutions are hyperbolic soliton solutions of kink type and singular type, respectively.

Case–3: , . Then the auxiliary ODE admits the following hyperbolic and trigonometric function solutions under different conditions:

Sub-case 3.1: ,

This solution is a hyperbolic soliton solution of bright type.

This solution is a hyperbolic soliton solution of singular type.

This solution is a non-periodic exponential-type wave solution.

4.2. Application of the Kumar–Malik Method

In what follows we treat one representative solution from each structural class—bounded and singular Jacobi elliptic waves, kink-type hyperbolic waves, bright and singular hyperbolic solitons, and exponential waves. Other members of these families arise from simple changes of the auxiliary parameters and exhibit the same qualitative behaviour, so we restrict attention to prototypical cases and indicate how the remaining solutions are generated.

Let the solution of Equation (

16) takes the form:

Substituting Equation (

39) with

into Equation (

16), and using procedure mentioned in

Section 4.2, we arrive at a polynomial equation in

.

Let the solution of Equation (

16) take the form

where

satisfies the auxiliary Equation (

21). To determine the positive integer

N, we apply the homogeneous balance principle to the leading–order terms of Equation (

16). The quartic leading term in (21) implies that

Consequently, if

for large

, then

The dominant nonlinear term in Equation (

16) behaves as

while the derivative–nonlinear terms satisfy

Balancing the highest–order contributions by requiring

immediately yields

Therefore, it is sufficient to take a linear polynomial ansatz

Substituting this form into Equation (

16) and using the auxiliary Equation (

21), we obtain a polynomial expression in

. Equating the coefficients of each power of

to zero leads to an algebraic system whose solution provides the constants

and

, together with the associated parametric constraints.

Setting the coefficients of powers of

, combined with the constant terms, to zero yields the system of equations, and solving that system gives the following values:

where

Using the above values in Equation (

12) gives the solution of Equation (

1) as:

where the values of

are discussed in following cases:

Case–1: Suppose and . Then admits the following Jacobi elliptic function solutions under different conditions:

Sub-case 1.1: If and ,

These solutions are bounded periodic wave solutions of the cn type and dn type, respectively.

These solutions represent bounded periodic wave solutions of the cn type and dn type, respectively.

These solutions are singular periodic wave solutions of the nc type and nd type, respectively.

These solutions represent singular periodic wave solutions of the nc type and nd type, respectively.

These solutions represent singular periodic wave solutions of the ns type and bounded periodic wave solutions of the sn type, respectively.

Case–2: , . Then admits the following hyperbolic and trigonometric function solutions under different conditions , :

These solutions are hyperbolic soliton solutions of the kink type and singular type, respectively.

Case–3: , . Then admits the following hyperbolic and trigonometric function solutions under different conditions:

Sub-case 3.1: ,

This solution is a hyperbolic soliton solution of bright type.

This solution is a hyperbolic soliton solution of singular type.

This solution is a non-periodic exponential type wave solution.

Because Equation (

1) contains the NLSE, LPD, and SSE as limiting cases, the solutions obtained above can be specialized accordingly. The derivation of the reduced ODE (16) and of the Kumar–Malik solutions only requires

; therefore all formulas remain valid when

. In this case, Equation (

1) reduces to the LPD equation, so the dark and bright solitons

and

given by Equations (55) and (57) constitute exact LPD soliton solutions as well. On the other hand, setting

suppresses the fourth-order and quintic contributions and leads to a different, lower-order ODE corresponding to the pure SSE or NLSE dynamics.

The explicit soliton solutions derived in this section elucidate several significant physical characteristics. of the concatenation model. The presence of Jacobi elliptic, hyperbolic, and trigonometric profiles demonstrates that the model supports a diverse spectrum of nonlinear wave phenomena, ranging from periodic wave trains to localized bright and dark pulses. The hyperbolic-type solutions correspond to classical solitons that preserve their shape during propagation, reflecting an exact balance between dispersion and nonlinearity. In contrast, the periodic elliptic solutions represent wave patterns that can transition into solitary structures under appropriate parameter limits, thereby illustrating how the system transitions between oscillatory and localized regimes.

The parameter constraints obtained through the Kumar–Malik method also provide insight into the role of higher-order dispersive and nonlinear effects. These constraints determine when the medium exhibits focusing or defocusing behavior, which in turn governs the emergence of bright or dark solitons, respectively. Furthermore, the existence of singular solutions highlights parameter regimes in which nonlinear effects dominate, resulting in wave steepening or possible breakdown of smooth pulse dynamics. In summary, the solution families derived here clarify how the interplay of dispersion, higher-order corrections, and nonlinear response influences the evolution of optical pulses in complex fiber systems.

5. Results and Discussion

Bright solutions describe high-energy or high-amplitude states, commonly used to analyze strong signals or energetic dynamics in various systems. Bright solitons, a key example, are localized wave packets characterized by an increase in intensity or amplitude. In nonlinear optics, they arise in focusing media and retain their form over considerable distances due to a balance between dispersion and nonlinearity, making them crucial for understanding the propagation of intense light pulses. Similarly, in plasma physics, bright solitons help model high-energy particle interactions and wave dynamics, providing insight into phenomena such as shock waves and charged particle behavior.

Dark solutions describe states of low energy or amplitude that emerge due to limited energy availability or specific interaction dynamics within a system. A well-known example is the dark soliton, which exhibits a localized reduction in intensity or amplitude against a steady wave pattern. These solitons are especially significant in nonlinear optics, where they occur in defocusing media and aid in the study of wave propagation and stability. Additionally, they are relevant in Bose–Einstein condensates, where they represent low-energy excitations that provide insights into quantum coherence and superfluidity. Their localized nature makes dark solutions valuable tools for analyzing weak signals and understanding the dynamics of energy in nonlinear systems.

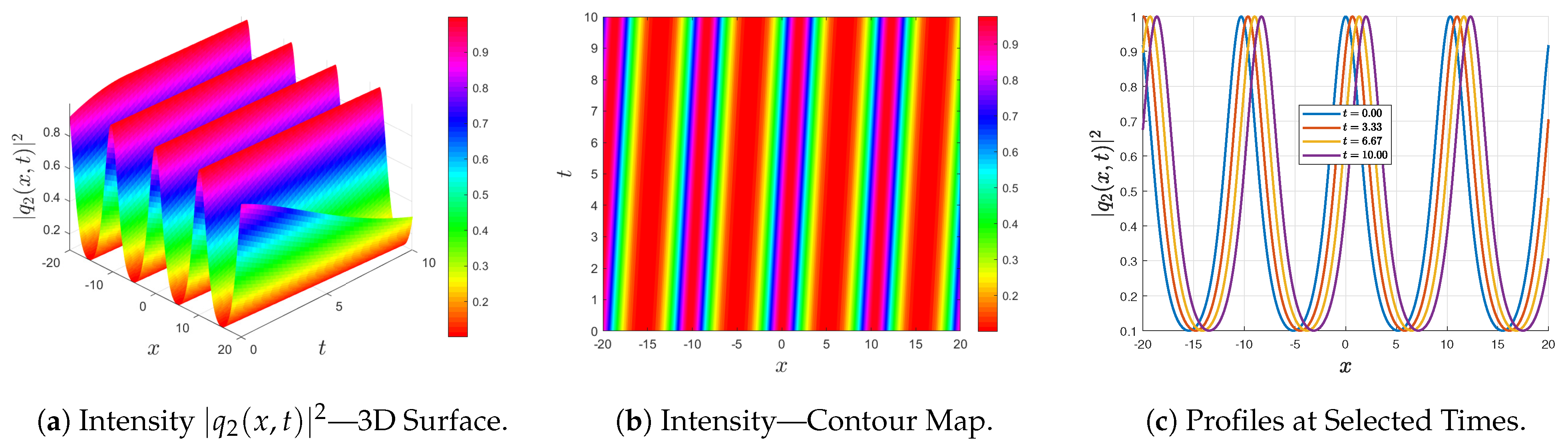

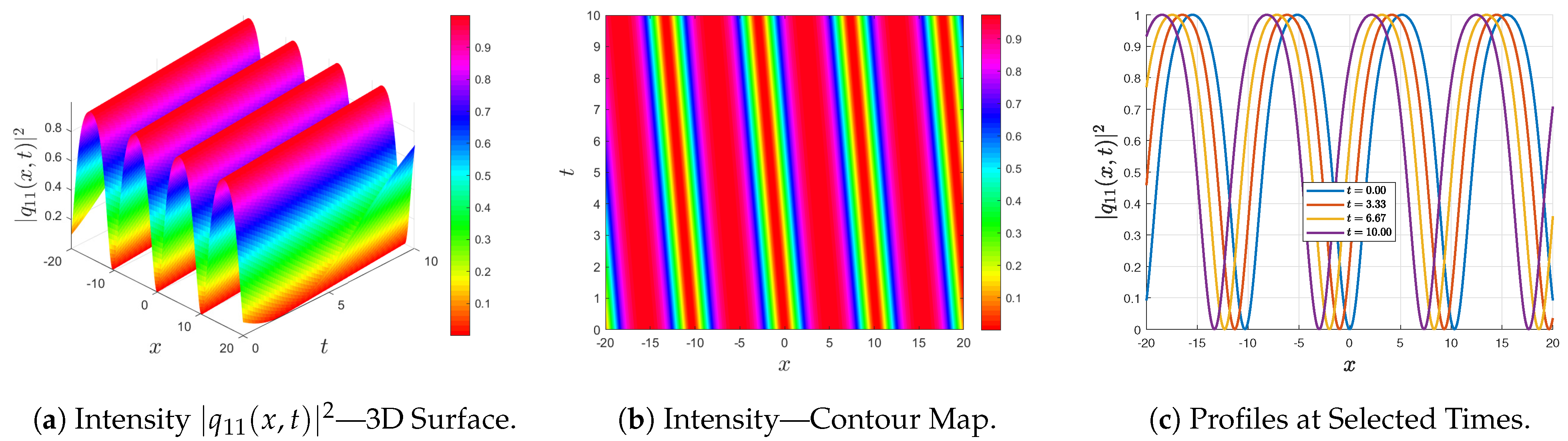

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the spatial–temporal dynamics associated with the bounded Jacobi elliptic cn- and dn-type periodic-wave solutions

and

, together with the numerically propagated profile

. The corresponding three-dimensional intensity surfaces, contour maps, and temporal cross-sections confirm that the periodic-wave trains remain bounded for all

shown and that the numerical evolution faithfully reproduces the analytical profiles, thereby providing a first numerical validation of the Kumar–Malik solutions in the periodic regime.

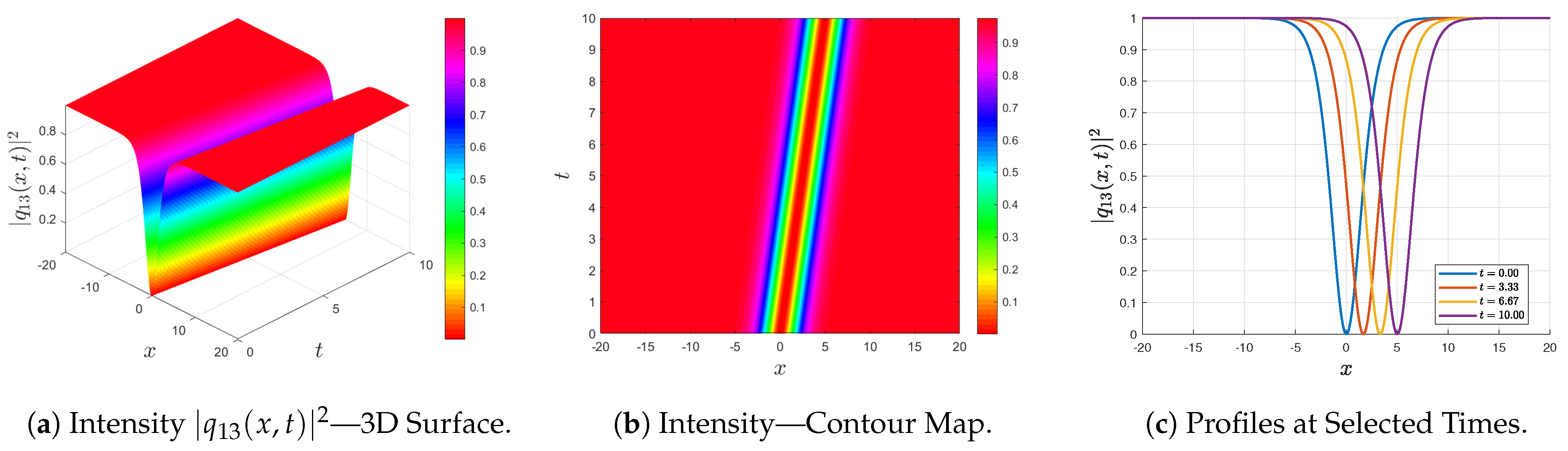

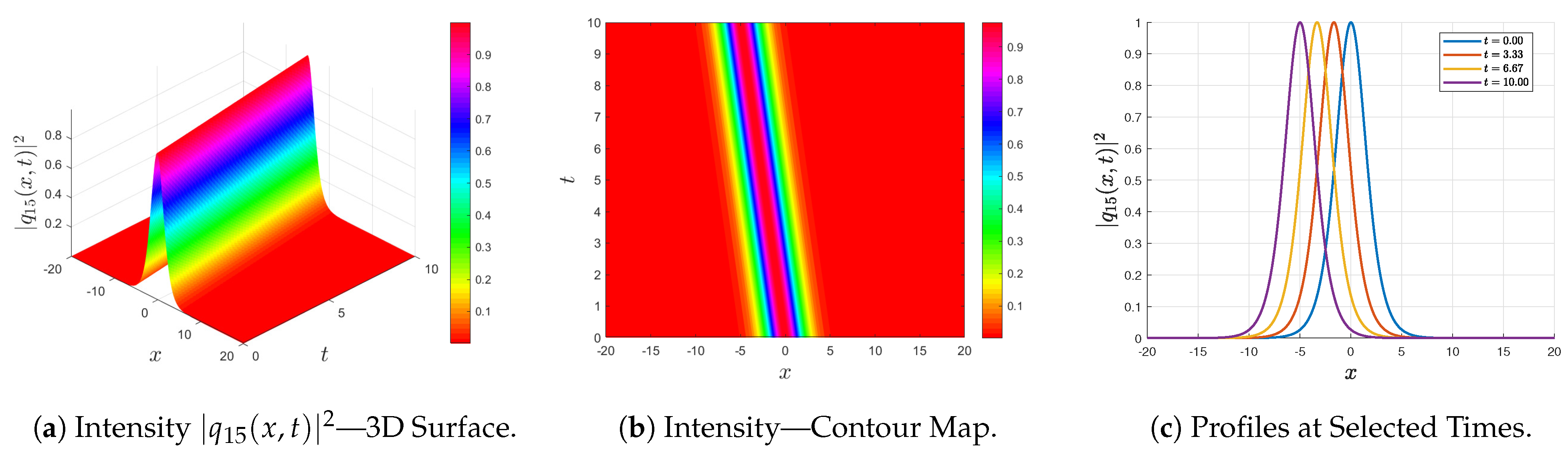

In contrast,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 display the spatial–temporal evolution of the dark- and bright-soliton solutions

and

, respectively, demonstrating how the solitary-wave limits of the analytical families manifest as localized intensity dips and peaks. Taken together, the periodic patterns in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 and the solitary structures in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 highlight the continuous transition from bounded Jacobi elliptic trains to hyperbolic-type solitons as the elliptic modulus approaches its limiting values.

Figure 4 corresponds to the dark-soliton solution

. The 3D surface clearly exhibits a localized dip in intensity embedded within a constant background, a hallmark of dark soliton behavior. The contour map reveals a diagonal propagation trajectory, indicating that the soliton travels with a constant velocity while preserving its shape. The cross-sectional profiles at selected times show that the width and depth of the intensity depression remain nearly invariant, confirming the soliton’s robustness under evolution. Moreover, the shift in the soliton’s position over time visually reflects the underlying balance between dispersion and nonlinear defocusing effects.

Figure 5 presents the bright-soliton solution

. In contrast to the dark soliton, the 3D surface shows a localized peak over a vanishing background, corresponding to a concentrated energy packet traveling in space-time. The contour visualization confirms the soliton’s steady propagation as it maintains constant amplitude and width. The selected-time profiles clearly demonstrate this invariance: although the soliton shifts position, its spatial profile remains unaltered, signifying the expected shape-preserving nature of bright solitons in focusing nonlinear media. These graphical results validate the derived analytical formulas and highlight the inherent stability of the bright soliton solutions obtained.

The graphical results further demonstrate how these solutions transition between different dynamical regimes. Jacobi elliptic-type solutions exhibit periodic wave structures, while their limiting cases (

and

) yield solitary-wave and harmonic solutions, respectively. This continuity underscores the model’s capability to capture a broad spectrum of nonlinear wave behaviors. The bright and dark soliton manifestations observed in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate how dispersion–nonlinearity interplay naturally gives rise to stable localized structures within the concatenation model.

From a physical standpoint, the soliton families obtained here reveal how different parameter regimes of the concatenation model control pulse dynamics. The sign of the effective quintic coefficient

plays a role analogous to the sign of the cubic nonlinearity in the classical NLSE: parameter sets with

support bright solitons on a vanishing background (e.g., solution

), whereas

combined with normal dispersion leads to dark solitons on a finite background (e.g., solution

). The higher-order parameters

,

, and

modify the soliton width and velocity by introducing third-order dispersion and derivative nonlinearities, while the auxiliary parameters

and the discriminants

in Equation (

21) determine whether the resulting wave is a bounded Jacobi elliptic train or a localized hyperbolic pulse. The specific parameter choices used in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 are selected so that the intensity

remains bounded and the solutions display physically realistic profiles in the context of pulse propagation in nonlinear optical fibers.

The conditions on

and the discriminants

in the auxiliary Equation (

23) also have a clear interpretation. For instance,

and

(Sub-case 1.3) yield bounded periodic Jacobi elliptic waves of cn/dn type, while the regime

(Sub-case 3.1) corresponds to localized hyperbolic solitons of bright type (solution

). Singular solutions arise when

or

, indicating parameter domains where the nonlinear terms dominate and wave steepening occurs. For clarity, the specific parameter sets used in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 are chosen within the bounded, physically admissible domains, ensuring that the intensity

remains finite for all

shown.

The present analysis is subject to several limitations. First, we have focused on the SPM-free concatenation model in its deterministic form. Effects such as linear and nonlinear loss, gain, and stochastic perturbations, which are known to play an important role in practical fiber systems, are not included and may modify the long-distance evolution of the soliton structures reported here. Second, although the Lie symmetry reduction leading to Equation (

16) is exact, the subsequent application of the Kumar–Malik method selects particular traveling wave families characterized by the auxiliary Equation (

21); other types of solutions, including non-traveling or multi-component structures, remain to be explored. Third, our numerical study only illustrates robustness against small perturbations and does not constitute a full spectral or nonlinear stability analysis, which would require a separate, more detailed investigation.

Future work will therefore address (i) the influence of loss, gain, and stochastic effects on the concatenation model, (ii) a systematic stability study of the bright, dark, and periodic solutions derived here, and (iii) the extension of the Lie symmetry and Kumar–Malik framework to fractional and higher-dimensional concatenation-type models.

6. Conclusions

In this work, the concatenation model was systematically analyzed using the Lie symmetry method in combination with the Kumar–Malik approach. The admitted Lie point symmetries were obtained, and the corresponding similarity reductions transformed the original nonlinear NLEE into tractable ODEs. Exact analytical solutions were derived in terms of Jacobi elliptic functions, hyperbolic functions, and trigonometric functions. In special cases, these solutions reduce to well-known optical soliton profiles.

The analytical solutions obtained in this study encompass periodic, bright, and dark soliton types, each providing valuable insights into the dynamics of the model. Periodic solutions describe oscillatory behavior occurring at consistent intervals, which is crucial for modeling systems with recurring dynamics, such as wave propagation in hydrodynamics. Bright solitons correspond to high-energy, localized wave packets that maintain their shape over long distances, providing a framework for studying intense light pulses in nonlinear optics and energetic particle dynamics in plasma systems. Dark solitons represent localized reductions in intensity or amplitude, providing a tool for analyzing low-energy excitations, stability, and weak signal dynamics in nonlinear optical media and quantum systems such as Bose–Einstein condensates.

To the best of our knowledge, this work represents the first report of optical solitons for the concatenation model obtained via Lie symmetry analysis combined with the Kumar–Malik method. The results presented here enhance the analytical understanding of the model and offer potential applications in nonlinear wave propagation in optical and related physical systems.

In summary, we have shown that the concatenation model, viewed as a unified framework encompassing the NLSE, LPD, and SSE as limiting cases, admits a rich spectrum of exact traveling-wave solutions when analyzed via Lie symmetry reductions and the Kumar–Malik method. The resulting families include bounded Jacobi elliptic waves, kink-type and bright hyperbolic solitons, and non-periodic exponential profiles, with representative dark and bright solitons illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. The analytical expressions and associated existence conditions clarify how higher-order dispersion and nonlinear effects govern the transition between periodic and localized regimes in nonlinear optical fibers. Together with the discussion of limitations and future work, these results provide a basis for further analytical and numerical investigations of concatenation-type models in more realistic physical settings.